Why Labor won

After we solve that puzzle we work out how to escape oligarchy

Me, Alex Kaschuta and whether embracing the alt-right was such a good idea

I enjoyed this conversation with Alex Kaschuta who, like Richard Hanania and others has recoiled from her embrace of the right on encountering where it has led. The conversation begins with my own embrace of some of the diagnoses of the alt-right while all along regarding their solutions as risibly threadbare.

Or if you prefer to listen via your podcasting app, here is the file on my Spotify channel.

Inside the instant explaneterium

I had extracted a bunch of instant analyses of the election, all of which read profound things into the result. I think what Annabel Crabb says below is broadly true. The Liberals continued to perpetrate acts of self-harm not just in ignoring women, but in pissing them off. Their representation in the cities has shrunk to near zero.

But the narrative fallacy has been out and about in full force. For instance:

Cassandra Kelly wrote:

Phew. Wow. Sheesh.

Go Aussie go.

I can’t quite find all the words, but I’ll try.

This wasn’t just an election result.

It was a mirror.

And what it reflected made me proud.

Australians have quietly but powerfully chosen values over noise.

I’m still processing all that it means, but this much is clear:

❌ They said no to division and authoritarian undercurrents.

✅ They said yes to diversity, truth, and fairness.

I can see why she feels that way. It’s certainly a nice thing to think. But all I could think about after the election was something someone said to me at lunch the day before. He’s an Australian data scientist who started at the Treasury but who’s been plying his trade helping left of centre parties around the world campaign against the authoritarian right. And he was just finishing up having helped out Labor (and I think some community independents) in Australia.

He wasn’t that confident of a Labor victory before the event, but did tell me that something unexpected would have to happen for them to lose. His big stat was that when the campaign started the campaign had asked voters who they felt would help most with the cost of living. 48% said Dutton and 46% said Albo. By the end of the campaign there’d been a 20 percent point swing to Albo. So that’s my go-to explanation. That well known Australian political trend-setter — the hip pocket nerve.

That and Donald Trump. I’m not sure why James Patterson’s not featuring in the Liberal leadership battle. He seems a cut above the leadership frontrunners. Perhaps the Libs should have a conclave.

The liberal moderates were also out in force as well they might have been. Like Simon Birmingham on LinkedIn:

I have deliberately remained silent about domestic politics since leaving the parliament in January, both out of respect for my former colleagues still engaged in the political contest and because my life now entails different professional responsibilities. Just because the campaign is now over, I don't intend to become a political commentator.

However, I have given most of my adult life to working for the Liberal Party and it has provided me with the opportunities of my lifetime. I cannot just stop caring and the weight of the outcome from this election does prompt me to offer a few thoughts.

Lessons from previous failures, especially the federal failure of three years ago but also many at state levels, have not been learned and acted upon. Having sat at the party's federal leadership table for much of the last decade, I must accept my share of responsibility for that.

Having allowed a bad problem to worsen so dramatically, the response must now be even more dramatic and touch upon all aspects of the party. Nothing can be sacrosanct if the party is to find a pathway to relevance with new generations of voters.

It must start with the raison d'être. Why do we have a Liberal Party and how is it relevant in 2025 and beyond?

The broad church model of a party that successfully melds liberal and conservative thinking is clearly broken. The Liberal Party is not seen as remotely liberal and the brand of conservatism projected is clearly perceived as too harsh and out of touch.

"Our base is too narrow and so, occasionally, are our sympathies. You know what some people call us: the nasty party."

So said Theresa May to the UK's Conservative Party back in 2002. The parallel is beyond striking...

Australians still seek all of the freedoms that liberalism stands for. Freedoms of belief, worship, family, enterprise and ownership. Indeed, they embrace more freedoms than ever in a society where people enjoy more rights to equality of opportunity and exercise those rights through a wide diversity of social, family and business constructs.

Yet in 2025 the Liberal Party is seen as grudging if not intolerant of the way some exercise those freedoms. It must be a party that respects all individual choices, actions and opinions, in the way John Stuart Mill articulated 200 years ago, limited only when they would cause harm to others.

Respect, inclusion and freedom can stand together, with support for all families and enterprises. But not alongside judgemental attitudes that exclude or isolate some.

Beyond the presentation of ideology, there must be a reshaping of the party to connect it with the modern Australian community. Based on who's not voting Liberal, it must start with women. Based on where they're not voting Liberal, it must focus on metropolitan Australia.

Concepts like quotas for women in parliament may be somewhat illiberal. But I struggle to think of any alternatives if there's to be a new direction that truly demonstrates change and truly guarantees that the party will better reflect the composition of modern society. Further, with parliamentary representation now at an all time low, such quotas could and should be hard, fast and ambitious.

Standing in the way of such changes are an increasingly narrow membership base, both in numbers and outlook. Overcoming this is an enormous challenge, for which I don't pretend to have all of the answers...

Regular people choose to associate with campaigns or movements nowadays, not join organisations. They follow ideas or causes online, but would never think to pay a membership fee, let alone attend branch meetings in dilapidated church halls.

Yet there must be a place in a liberal democracy and market economy like Australia for a political party not owned by unions or any one controlling entity but one that upholds values that support enterprise, innovation, freedom and mutual respect for one another.

Cry the beloved country

Ezra Klein’s book before last, Why we’re polarised documented the way in which political scientists argued that American political parties were anomalously broad churches - with the Republican Party being the party of Presidents Lincoln and (Teddy) Roosevelt and the Democrats being the party of unions and Southern racists. Their advice was that these parties needed to become more ideologically polarised to give the public true choice. How’s that going then?

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the Anglosphere we did things more obviously along ideological lines. So I didn’t read much into Klein’s arguments for Australia. But I was wrong. Yes, our parties are more coherently oriented around the left/right dichotomy, but they were relatively broad churches (with the left having a longer (fatter!) tail towards the far left than existed in the US.

Then the right went kind of crazy. All in on the free market paradigm (but still somewhat reluctantly a broadish church with a non-negligible moderate ‘wet’ faction to use Margaret Thatcher’s terminology). Now the right are heading towards something that has yet to stabilise, but looks pretty nihilistic. Meanwhile on the left it’s mostly careerism, though there’s a fair bit of basic sanity and (in comparison to the other side) competence in Cabinet and even coming up through the ranks.

Annabel Crabb on improving your work-life balance

By ignoring women

In an election that turned out to be a cracker-box of explosive developments, one of the most ironic — surely — is the degree of work-life balance suddenly opening up to a large number of middle-aged Liberal men.

From Liberal leader Peter Dutton to shadow ministers like Michael Sukkar and David Coleman, through backbench stalwarts like Ross Vasta and Bert van Manen, an entire cohort of busy parliamentarians woke this morning to the immensely flexible prospect of not having to go to work anymore, at all.

The ranks of Liberal MPs collecting pink slips from their electorates skewed heavily male last night. That's not an expression of voter misandry. It's mainly because there are — or were — just so many more Liberal men than women in the people's chamber; before yesterday's rout, just one in every five Liberal MPs in the House of Representatives was female.

That proportion should now improve, though for the grimmest of reasons...

The 2022 post-election review conducted by frontbencher Jane Hume and former federal director Brian Loughnane — currently returning a 404 search fail on the Liberal Party website — found that the party had failed to appeal to female voters and should work to preselect women in 50 per cent of seats, noting that the 2022 "teal wave" in its heartland had been driven significantly by the annoyance of professional women.

This analysis could not have been clearer, or more comprehensible.

What is less comprehensible is the party's decision to initiate a policy reform in the 2025 campaign that could not — even with a lab full of high-grade behavioural economists — have been better designed to infuriate women further...

Oddly enough, the policy of ending work from home for federal public servants was announced by Hume, the author of the 2022 review.

It was backed in by Dutton, whose primary target was the Canberra-based public service.

But the Liberal leader's freelance observations about affected women being welcome to "job-share" opened up — among the frazzled domestic multitasking demographic — what the WWE superstar "Stone Cold" Steve Austin used to term "a can of Whup-Ass"...

In a scan of ABS data on areas where people were most likely to work from home during COVID, my colleague Tom Crowley identified 25 seats with above-average numbers of flexible workers.

Seven of them were Liberal seats. Seven of them were "teal" seats. And all 25 of them were lost by the Coalition last night, including Dutton's own seat of Dickson, where — according to the ABS — 51 per cent of people worked from home to some extent during the pandemic...

Flexible work has always been — and continues to be — a work-life balance technique employed more by women than men.

Dutton's language around the policy — equating working from home with "refusing to go to work" — conveyed a set of values that was clearly heard by Australian women.

The blowback was violent and immediate...

The research company RedBridge compiled six survey waves of voters in 20 key marginal seats over the course of this year.

The first wave — conducted in February — found that Peter Dutton had a net approval rating of minus 11 among women.

By last week, the sixth and final survey identified a slump of 17 points in that approval rating; Dutton was down to minus 28.

His approval rating among men decreased too — from minus 13 to minus 18. But there is no mistaking the "ick" factor among female voters here.

Once again — as it did in 2022 — the Y chromosome wafted pungently through the campaign imagery planned out by the Dutton campaign. Plenty of hi-vis and factories, and not so many visits to aged care, child care or the other workplaces where women are over-represented...

Women were also more sceptical than men about nuclear energy, the core policy differentiation between the two major parties at this election...

The party's earnest ambition to preselect women in 50 per cent of seats fizzled this year, as it has every election year. Only 34 per cent of Liberal candidates were female...

It's been 30 years now since the Labor Party put itself through the process — painful at the time — of opening its representative ranks to women, when it installed quotas.

In the last parliament, 47 per cent of Labor House of Representatives seats were held by women, nearly two and a half times the proportion clocked up by the Liberals.

And now, as the Liberal survivors of Election 2025 straggle out into the daylight, dust themselves off and wonder tiredly who among their depleted ranks will take up the leadership baton, the real question is a deeper one.

Does this party — formed in 1944 partially through the efforts of highly organised and powerful women's groups, and directed by its birth father Robert Menzies to reserve specific executive leadership roles for women — care enough about women to do the hard work of including them?

Some interesting election numbers and graphs from Julian Fell at the ABC here.

Sky after dark clarifies a few things

If you’re ever confused, particularly about current affairs. Do what I (and Richard Yabsley) do. Watch Sky after dark.

Greens should celebrate (despite losing seats)

Philosophy Bear (and fellow traveller in proposing sortition based tribunate sets us straight on the election.

I was at the ACT Greens' election party last night, and it is fair to say the mood was subdued as their lower house seat count may well fall. It needn't have been, last night was a victory in a string of triumphs.

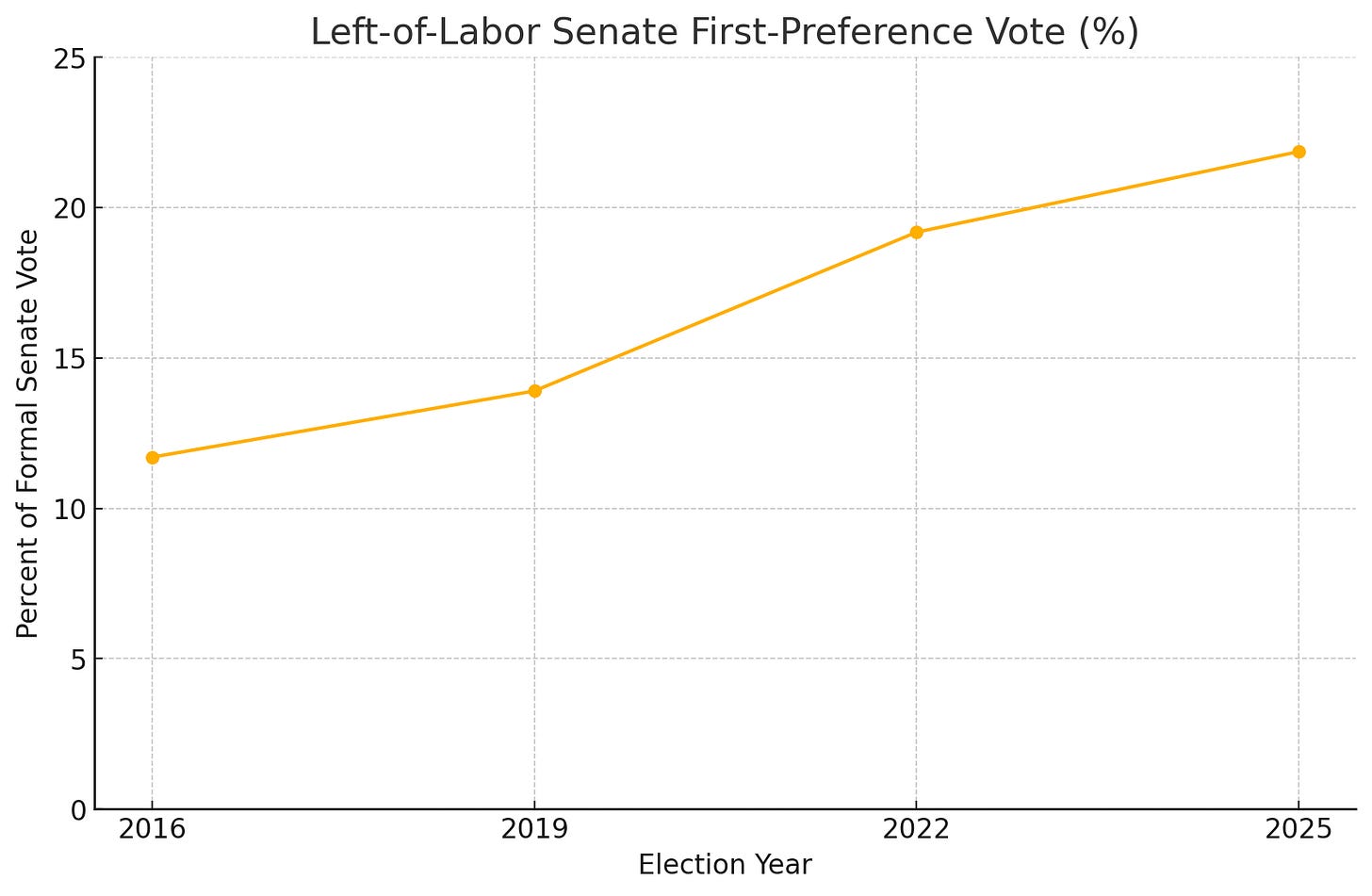

For many, the story of last night's Australian election will be Albanese's near two-party-preferred margin of victory, not seen in 50 years. Certainly, that's likely to have the greatest short-term impact, there's a larger story, though, that has been neglected because it's happened more consistently than quickly: the rise of electoral forces Left-of-Labor. In less than ten years, this bloc has increased in size from a bit more than a third to a bit less than two-thirds the size of Labor.

The inexorable rise of the Left-of-Labor vote has, through 2016, 2019, 2022, and 2025, taken the Left-of-Labor vote from 11.7% to 21.9% in the Senate. The Senate is our best guide here because: 1. Various small parties can be inconsistent in running in particular electorates, and 2. misunderstandings of how our voting system works sometimes prevent people from voting for their favourite in the lower house out of a misplaced fear of "wasting" their vote.

We are, of course, relying on preliminary votes for our 2025 results, but if anything, it is likely that later counted votes will favour the Left-of-Labor bloc a little more.

Counting as left of labor: The Australian Greens; Legalise Cannabis Australia ...; the Animal Justice Party; FUSION ...; Victorian Socialists; Socialist Alliance; the Indigenous/Aboriginal Party of Australia; Australian Progressives; ... and Senator David Pocock (counted from 2022 onward). ...

To sum up, the Left-of-Labor vote has grown by over 1% per year over the last four cycles. If this trend continues, ... it will be 25-30% within two cycles and the Left-of-Labor will regularly win 2 out of 6 senate seats per state- the red chamber indeed. ...

You might think that this is just a trend toward minor parties which has favoured the right as much as the left, but that is not so- between 2016 and 2025, the Right-of-Coalition vote has only gone from 13.6 to 14.8 ...

So there has been no rise of 'extremism' or 'populism' 'on both sides' in Australia, despite what David Speers' adjacent commentariat of Australia might have you believe.

The rise of the Left-of-Labor bloc has been ignored for three reasons: 1. Because, as mentioned above, it has (wrongly) been amalgamated into a story about minor parties outside the Overton Window "on both sides" which the data doesn't support. 2. Because it has happened consistently over a long period of time at a moderate pace. 3. Because of a focus on the number of seats won, which in a non-proportional system is a terrible guide. However, the non-representativeness of a system of single-member seats also means that things can change quickly. If this trend continues - if the Left-of-Labor bloc hits 25-30%-, "all of a sudden" we will see seats flip to Greens and leftwing independents in the dozens, and then this trend will be impossible to ignore.

The old mole burrows.

Are generalists strangling expertise?

Marcus Wigan and Pia Andrews have written about a great bugbear of government. The domination of generalists. They’re right of course, but I’m not sure their critique is critical enough. They see the drive for efficiency as producing this result. I think that’s a small part of it. Hierarchica bureaucracies are run for the convenience of the higher-ups. And it’s much more convenient for them to value generalism.

After all, a hierarchy needs ‘safe pairs of hands’. Given that it’s more convenient if you can move them anywhere, and that’s how you make your way up the Velcro pole.1 Generalist Peter Shergold made a similar point as he rose through the ranks of the public service. As he put it in 2005:

If there were a single cultural predilection in the Australian Public Service that I could change, it would be the unspoken belief of many that contributing to the development of government policy is a higher-order function — more prestigious, more influential, more exciting — than delivering results. Perhaps it is because I have spent so much of my career in line agencies, learning to deliver Indigenous, employment, small business, and education programs that I react so strongly against this tendency.

Eight years later he confessed that little more progress had been made:

Too much innovation remains at the margin of public administration. Opportunities are only half‐seized; new modes of service delivery begin and end their working lives as “demonstration projects” or “pilots,” and creative solutions become progressively undermined by risk aversion and a plethora of bureaucratic guidelines.

And here we are. One further point is that talking about ‘what works’ is the way you’d expect generalist to frame policy problems. Why? It conveys the idea that certain discrete things work and all we need is some generalist senior bureaucrats and perhaps some ‘freakonomists’ to suck up the knowledge that’s already out there in the land of practice and then we ‘roll it out’ and ‘scale’ it.

But if you asked “what works” in the design and building of bridges, or the flying of planes or performing knee arthroscopies, you’d also want to know who made it work. And if you were governing any of those domains, you’d want those people who can actually do difficult things to have a pretty important seat at the table as we spoke about spreading their knowledge.

Anyway, on with Marcus and Pia’s piece:

With the establishment of a perpetual efficiency agenda, public service leaders were expected to maintain and even redouble efforts towards business outcomes over public outcomes.

This eventually created a public sector environment where people who could find savings for savings' sake were more valued than those who knew how to deliver on the purpose or mandate of a public institution...

"Generalist management" created an executive culture more focused on mechanisms of management than delivering public policy or value to the community. Expertise became the pesky, inconvenient truth that gets in the way of executive careers, and "generalism" became a legitimate and highly rewarded career pathway...

There is certainly a strong argument for valuing leadership skills in senior executives, but generalist management training doesn't produce leadership behaviours. It has produced several generations of micro-managers who don't fundamentally understand or are motivated by purpose, policy or public outcomes...

The false presumption that a person can only be either an expert or a manager created an unintended friction for how the public sector values expertise. The more senior a person, the more generalist they are expected to behave, creating an unfortunate air gap between decision-making and the expertise needed to inform it...

This trend has been well documented by academics and think tanks and is captured well by Althaus and Wanna (2008), who identified this shift as, "the preferential elevation of the 'generic' mobile executive suggests an emphasis on administrative competence ('neutral competence') rather than policy or technical expertise"...

Senior leaders are now primarily valued for the time they've already had in an identical role, rather than for their relevant expertise or delivery record, creating a perverse incentive to keep hiring more of the same, even when the current approach is demonstrably failing...

With the increasing speed of technological, global and societal change, compounded by an increasing rate of emergencies, it begs the question: How will we create more adaptive, resilient and responsive public institutions if we just keep doing more of the same?...

When specialists, expertise and outcomes-based performance of senior managers are seen once again to be critical elements of the public service mix, this will change the modes of operation and place pressure on those who have grown up in this system to adapt. It all starts with the systemic revaluing of expertise at all levels.

Samo Burja on bureaucracy as oligarchy

The discussion on bureaucracy as oligarchy gets going at around 11 minutes in. I’m not that crazy about his propertarian solutions to the problem, (and I have my own ideas, but they’re pretty speculative), but it’s a hard, hard problem. And I think Samo’s hunch that, over time hierarchical bureaucracy can become quite remarkably self-serving and inefficient is pretty on the money.

Measuring what makes us flourish

Yes, it’s a bit silly but there you go. I broadly agreed with its conclusions.

Meanwhile on a planet far far away

It’s not what you know

But who you know, and whose genes and upbringing you got

A really good romp through what we know about the perseverance of inequalities through time. The bad news is that they’re much greater than you might think. In a way I think of this as analogous to what I suggested above - namely that focusing on ‘what works’ leaves out the serious part - which is working out and empowering those who made it work. There’s a whole stack of tacit capabilities that are usually crucial. But it’s much easier not to worry about them (if you’re focusing on appearances rather than getting good results).

Introduction

When it comes to the topic of immigration, it is widely believed that assimilation is both important (normatively) and rapid and widespread (descriptively). Rapid assimilation is often simply taken for granted. For example, in economic analyses of the impact of immigration, it is not uncommon to see it assumed that second-generation immigrants have similar economic behavior as natives.

But nowhere is the story of assimilation more important than in America, the so-called "Melting Pot." In this piece, I will argue that the notion of widespread and rapid assimilation in America is largely a fiction. In reality, assimilation in America has been slow and incomplete...

Persistence is the norm

It's worth first addressing more generally why rapid and widespread assimilation shouldn't be expected. Outside the context of immigration, the reality of widespread long-run persistence has already been well-documented. Two growing scientific literatures are of particular note here.

The first of these literatures is the deep roots branch of economics... One illustrative example is that a country's level of technological adoption in 1500 AD is strongly associated with modern national economic prosperity (Comin et al., 2010). Importantly, the migration-adjusted association is much stronger than the non-adjusted association. In simple terms, this means that development follows people, not places.

The second is the literature on the long-run multi-generational social persistence (or mobility)... As one illustrative example, in a study using rare surnames, it was shown that people overrepresented in the Oxbridge universities had descendants that were still still overrepresented many centuries later (Clark & Cummins, 2014).

An important discovery is that naïve measures of social mobility have overestimated how mobile societies truly are. Using multi-generational data, the degree of persistence is significantly stronger than you'd predict based on simple parent-offspring correlations...

In short, long-term persistence is the norm, and is surprisingly resistant to external shocks. The obvious question is: why should immigration be any different? As I'll argue—it's not.

The Not-so Melting Pot

Immigration and assimilation are intimately connected to the American history and identity. It is a "nation of immigrants" and part of the "American dream" was the freedom and opportunities that America could provide over other countries.

Most importantly, America is also the "The melting pot." This metaphor speaks directly to the American assimilation story — disparate ethnic groups coming together, melting together into a singular homogeneous American culture... But how much truth is there to this story? Is the American story really one of widespread and rapid assimilation? The evidence suggests no.

European immigrants

When it comes to the Age of Mass Migration (1850 to 1920s), it is often ignored that large shares of European immigrants did not "assimilate"—they returned home because they couldn't assimilate. At least 25-40% of European immigrants returned to their home... What at the surface appears to be widespread successful integration is thus to some extent a manifestation of survivorship bias.

Contrary to common belief, economic disparities were also not quick to disappear. Using an impressive three-generation dataset linking immigrant grandfathers in 1880 to grandsons in 1940, Ward (2020) shows that European ethnic disparities in occupational income were strongly persistent...

Mexican immigrants

... The prediction that Mexican immigrants will rapidly assimilate to their non-Hispanic white peers is also unlikely to come to fruition. The analogy between Mexican immigrants and former European immigrants is flawed for two reasons. First, it exaggerates how different European ethnic groups were in the past. In reality, their differences were comparatively modest. Second, it exaggerates how quickly European immigrant groups assimilated...

The findings of a unique and impressive study are particularly illuminating regarding historical Hispanic assimilation. In their 2008 book, Telles & Ortiz were able to follow Mexican immigrants and their actual descendants across several generations. Contrary to the authors' expectations, there was little support for the assimilation narrative: "the educational progress of Mexican Americans does not improve over the generations […] our data show no improvement in education over the generation-since-immigration and in some cases even suggest a decline."

The elephant in the room

Setting aside European, Asian and Hispanic immigrants, there is a much more glaring problem with the American assimilation narrative—the persistent American underclasses, black Americans and Native Americans.

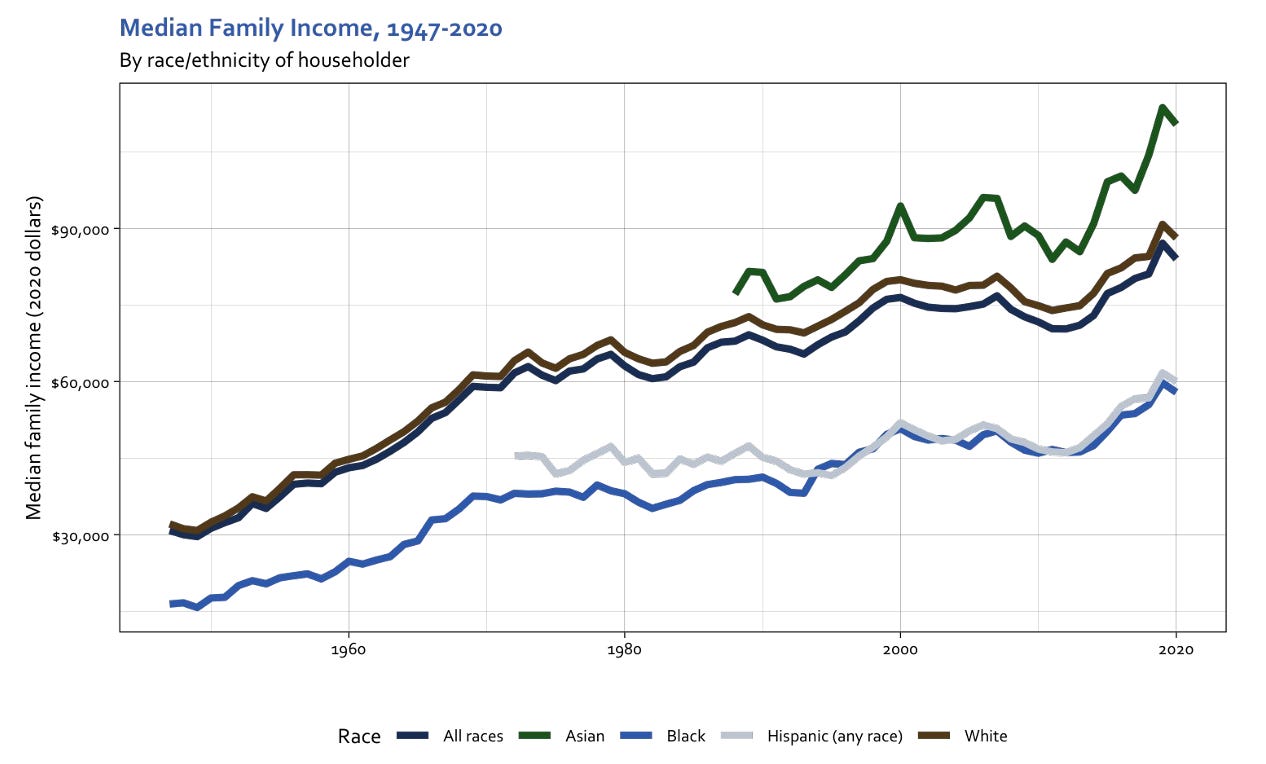

It is well known that large black-white disparities exist in important domains such as economics, education and crime. And... there has been little convergence with respect to some important measures for over 70 years...

Conclusion

Evidence shows that social status persists strongly across multiple generations. Much the same applies in the context of immigration assimilation: multi-generational persistence is the norm, with only very gradual convergence that can easily take well over 100 years... While the melting pot metaphor sounds appealing, it is largely a fiction. America is not a place where widespread and rapid assimilation occurs.

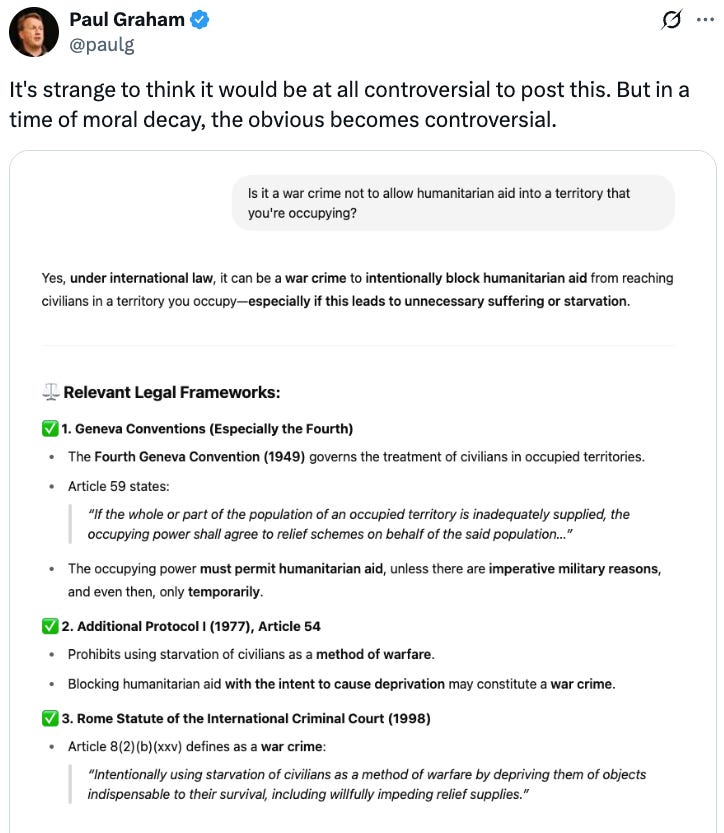

Paul Graham staying where he’s always been. He’s a low taxing silicon valley billionaire liberal. But he’s remained untempted by the hubristic right.

Another day in Anarcho-Plutocristan

Another great interview

Varoufakis on techno-feudalism

This is all a bit pat for me. Too neat for a map of the future. But worth pondering nevertheless.

Trump is a godsend for Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, and the other technofeudal lords. Any short-run loss from his tariff delusions is a small price to pay for an agenda that would deregulate their AI-driven services, bolster crypto, and exempting their cloud rents from taxation.

Neoliberalism was neither new nor particularly liberal when it prevailed 50 years ago. Its great advantage was its sharp deviation from classical liberalism. Even though it paid tribute to liberal thinkers, neoliberalism shared neither their method nor their concept of the market. Today, we are on the cusp of another, equally profound, ideological innovation.

Unlike Adam Smith or John Stuart Mill, neoliberals felt no responsibility to demonstrate, theoretically or empirically, under what circumstances the unfettered market could be relied upon to transmute private profit-seeking into collective prosperity. The invisible hand was divine, infallible. Even when the market failed, they claimed, any attempt to correct it through some collective agency was doomed to fail more horribly. It was an attitude that suited Wall Street to a tee. The 1970s craved such doctrinal indifference to actual evidence about the consequences of fully deregulating financial markets. Once America had become a deficit country and President Richard Nixon delivered his shock by decoupling the dollar from gold in 1971, successive administrations chose to enhance US global hegemony by boosting – not curtailing – the country's fiscal and trade deficits...

Today, the ascendancy of a new form of capital – cloud capital, or networked algorithmic machines that furnish its owners' remarkable powers to modify our behavior – needs its own ideology to be fully liberated. I have called this new system technofeudalism – a mode of production and distribution which, powered by cloud capital, is replacing markets with cloud fiefs (like Amazon) and capitalist profits with cloud rents.

To realize the full power of cloud capital, its owners (people like Jeff Bezos, Peter Thiel, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk) require a new ideology. Just as Wall Street financiers needed neoliberalism after the Nixon shock, this new ideology must support cloud capital's expanding domain in three ways.

First, it must legitimize the colonization of human endeavor. Beginning with the relaxation of rules governing, say, self-driving vehicles and AI-driven medical and legal services, the ideology must justify the limitless replacement of fallible, recalcitrant humans by cloud capital-driven machines in every realm...

Second, the new ideology must legitimize the colonization of state institutions, especially the privatization of public data through its transfer to Big Tech's cloud capital. It must, for example, justify Musk's use of his Department of Government Efficiency to hook his cloud-capital systems into various federal agencies...

Third, it must legitimize the colonization of Wall Street. Zuckerberg was the first technofeudalist to try to create his own digital currency, Libra. Wall Street foiled him. But then Musk's purchase of Twitter, now X, evolved into a bolder attempt to create an "Everything App" that challenges Wall Street's payments monopoly...

This new ideology is already here. I call it techlordism, a mutation of transhumanism – a creed that advocates blurring the lines between organic and synthetic until augmented humans achieve genuine freedom, or even immortality. Just as neoliberalism borrowed from classical liberalism but usurped it by adding a divinity (the infallible market), techlordism makes itself useful to cloud capital's three-pronged colonization drive by replacing the neoliberal Homo Economicus with an amorphous "HumAIn" (a human-AI continuum). Techlordism also replaces neoliberalism's divine being. The new divinity is the algorithm that renders the signaling functions of the decentralized market mechanism obsolete, yielding (in the image of amazon.com) a totally centralized mechanism for matching buyers and sellers.

The repercussions of the societal transformation accelerated by techlordism are breathtaking. They include unprecedented macroeconomic instability (as cloud rents decimate aggregate demand), the demise of democracy, even as an ideal (a position advocated by Thiel, an early prophet of techlordism), and the end of universities (replaced by personalized AI-driven augmentations).

In this light, Trump is a godsend to the technofeudalists. His agenda – fully deregulating their AI-driven services, bolstering crypto, and exempting their cloud rents from taxation – is supercharging cloud capital's power to extract rents. For the new ruling class, whatever money they lose in the short run from Trump's tariff delusions must seem like a magnificent long-term investment.

The AI arms race in hiring

The very terrific Sarah O’Connor from the FT. Thanks to a reader for pointing me to the column.

You can almost hear the howls of frustration from HR departments. Jobseekers have discovered artificial intelligence and they're not afraid to use it. Employers have become snowed under by people using the new tools to churn out imper- sonal applications. Some applicants are using AI to bluff their way through online assessments, too. The FT has reported that many large employers have a "zero- tolerance attitude towards the use of AI".

I'm sure that would be news to applicants, who have had to put up with the use of AI by large employers for years. Indeed, jobseekers would be well within their rights to say: but you started it.

Like many cautionary tales, this one begins with good intentions. In the 2010s, employers implemented new automated recruitment tools to whittle down can- didates before the interviews because they wanted to make the process more effi- cient and more fair, with less risk of human bias...

"Asynchronous video interviews", for example, involve job applicants answering questions alone in front of their webcams with no human on the other side. Often, an AI system assesses their responses. But I have never met a jobseeker who liked them.

In 2021, I wrote about research which warned that young people felt confused, dehumanised and exhausted by the new tools. I was flooded with responses. "I did one of these and it was the hardest and most humiliating experience I've ever encountered," one older man wrote. "An interview itself is hard enough for someone who is in the job market for the first time in years, but then you throw this at them. I don't mind saying I was traveling and did one from a hotel (not an ideal set up with my iPad balancing on a suitcase) for a company that I had dreamed about for 30 years. The pressure was so intense, I messed it up." After- wards, he said, he sat in his hotel room and cried...

So it should be no surprise that jobseekers have turned to new generative AI tools such as ChatGPT to speed up or "game" a process that already felt dehumanised. Videos have even appeared on TikTok in which people demonstrate how to use ChatGPT to provide answers to questions in asynchronous video interviews, which the applicant then simply reads out.

That said, the ensuing AI arms race is clearly not going well for anyone. It was supposed to improve efficiency and fairness. It has become a threat to both.

On the efficiency side, employers complain they are overwhelmed by applica- tions, which only fuels more rejections. "I hesitate to say it breaks the system, because it's not broken, but it does mean you're getting ever more applications coming," Stephen Isherwood, joint chief executive at the Institute of Student Employers, told me...

Uneven access to the paid-for AI models that perform best on hiring assessments might be fuelling a new type of unfairness, too. Jamie Betts, founder of assess- ment company Neurosight, told me their survey of 1,500 jobseekers last year found that 31 per cent of men were using a paid-for AI tool, compared with 18 per cent of women...

What are the solutions? Some online assessments are, for now, less vulnerable to AI use, such as those that involve playing short games. But I wouldn't be sur- prised to see the return of mass inperson test centres for technical skills assess- ments. Isherwood and Betts both said employers were thinking about reintrodu- cing the human touch earlier in the process, too.

Even HireVue, a big vendor of asynchronous video interviews, wrote in a paper last year: "One of the best ways to reduce cheating behavior of all types is to util- ize a multi-stage workflow in which a candidate's knowledge, skills, and abilities are validated by an interviewer in a live interview setting."

Would there be a trade-off with bias and consistency? Perhaps. But if there is a lesson from this cautionary tale, it is that technology can't just magic trade-offs away. Seemingly simple solutions to hard problems don't usually stay solved for long.

From Oxford’s Ashmolean

Is Ozempic weight loss the wrong kind of weight loss

Hint: no

Running into a long substack on it, I wanted to know the answers the article gave without wading through it all. So I asked Claude to give me the bottom lines:

The author begins by noting that some critics dislike these drugs for making weight loss "too easy" and have invented various concerns that haven't been supported by evidence. The article then examines three specific claims:

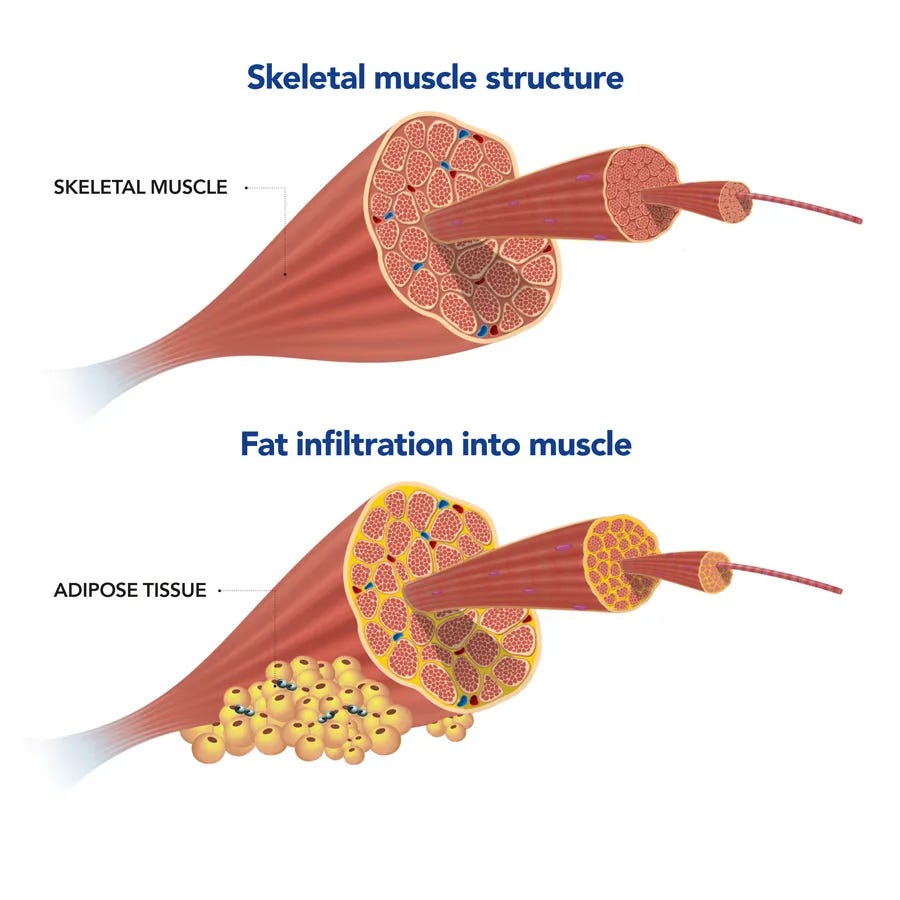

Claim 1: People lose more muscle than fat on GLP-1RAs This claim is contradicted by clinical trial data. In major trials of Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, and Retatrutide, participants consistently lost more fat than muscle, improving their body composition. For example, in a Tirzepatide trial, participants lost 33.9% of fat mass but only 10.9% of lean mass, resulting in improved body composition ratios.

Claim 2: Muscle loss ratio is unusually high compared to non-drug methods Research comparing lean mass loss across different weight-loss interventions (diet, GLP-1RAs, bariatric surgery) shows statistically indistinguishable reductions at similar levels of weight loss. A recent study using MRI measurements found no significant difference in muscle volume loss between Tirzepatide users and those losing weight through lifestyle changes.

Claim 3: GLP-1RAs produce muscular dysfunction Evidence shows that fat infiltration in muscles (myosteatosis) decreases with GLP-1RA-induced weight loss, similar to non-pharmacological weight loss. This reduction in fat infiltration is associated with improved muscular function and physical performance. Trial participants report fewer physical limitations and improved functioning, supported by reductions in cardiovascular risk factors and improved lung function.

The article concludes that GLP-1RA-induced weight loss should be regarded as health-promoting to the same degree as weight loss achieved through other methods. The author suggests that criticisms about muscle loss and other alleged side effects lack scientific support and biological plausibility.

Heaviosity half hour

Fintan O’Toole on Shakespeare

I’ve really been enjoying this short book by Fintan O’Toole and occasional Kilkenomics attendant. Its argument is a bit fast and loose in places but there you go it’s not an academic book. When I was studying history I learned to be suspicious of explanations for social phenomena relying on capitalism and the ‘rising middle class’ well before the industrial revolution. Still, I think O’Toole’s basic instincts are right — that Shakespeare’s monumental achievement is built on a profound faultline between the medieval world and the onrush of something profoundly alient to it. We see that thing as ‘modernity’ as we experience it. That’s a mistake we can’t help making, but there you go. I kept thinking of Alasdair MacIntyre’s idea that modernity has shattered the morality of the west (that of medieval Christianity) and ushered in what he calls ‘emotivism’ - the idea that moral judgments cannot be grounded in anything deeper than preference and feeling and that, accordingly moral discourse ultimately gets down to manipulation rather than rational argument.

I’m still finding the book a really good provocation, though be warned - my knowledge of Shakespeare comes from high school, and the odd bit of reading and going to his plays. This is his introductory chapter with the first two sections heavily edited back, the last two much less so.

1. Muesli, Morals and a Bright Backside

The plays of William Shakespeare were written on the playing fields of Eton. Or, at least, the plays of Shakespeare as they have been taught in school, were. In the form in which most people first encounter them, Hamlet or Macbeth, King Lear or Othello are made to seem as if they have very little to do with the theatre...with a man trying to create new rituals for a world that was changing at a frightening pace, and everything to do with building character...They are an ordeal after which you're supposed to feel better, a kind of mental muesli that cleans out the system and purges the soul...

The plays that Shakespeare actually wrote, on the other hand, are full of great stories, extraordinary people, wonderfully rich language and a skill with drama that has seldom been matched...Shakespeare is hard, but so is life, and so long as you can see that there's a lot of life in Shakespeare, then the effort begins to make sense.

What doesn't make any sense is the idea that Shakespeare is trying to demonstrate moral ideas to us...If you look at him this way, then he's not just boring and banal, he's also pretty stupid...The message of Macbeth is that it's a bad idea to kill kings. The message of Hamlet is that Hamlet should have killed the King sooner. Othello is doomed because he is too jealous of what he has. Lear is doomed because he is not jealous enough and wants to give away what he has...Either there is something else entirely going on in his plays, or we should all go back to watching soap operas where at least the moral messages are fairly consistent.

2. Heroes, Greeks, Tragic Flaws and True Confessions

Before we can begin to understand, and therefore enjoy, Shakespeare's tragedies, there is a thick undergrowth to be cleared away: all that stuff about Tragic Heroes, Tragic Flaws, Fear and Pity, Character, and so on...Shakespeare himself may or may not have been aware of Aristotle's book, The Poetics...But even if he was familiar with the so-called Aristotelian rules, he felt free to ignore them...The only evidence of Shakespeare's attitude to Aristotle that we have from his plays is that he didn't know very much about him...

The habit of seeing Shakespeare through Aristotle in fact has almost nothing at all to do with Shakespeare and is the invention of Victorian England...The Victorians, however, were at the centre of a great world Empire and liked to think of themselves as the essence of modern civilization. Since they thought of ancient Greece as the essence of classical civilization, they naturally wanted to identify themselves with it as much as possible...

There are three basic ideas which we have taken from the Victorians via Aristotle and which combine to make the study of Shakespeare so tedious:

The idea of the Tragic Flaw...The problem with this notion...is that Shakespeare's plays make no consistent sense when seen in this way...The tragedies are littered with innocent corpses, people who have done nothing to bring death on themselves but who nevertheless meet it...If jealousy is Othello's flaw, what is Desdemona's? If ambition is Macbeth's flaw, what is Cordelia's?...

The idea of the tragic hero, which cuts the central character off from the play and then goes on to examine in isolation the characters of all of the other people who affect what happens to him...If you isolate the individuals in a play and then try to analyse their characters in a static way, they are not only tedious but impossible to understand...

The whole idea of the soliloquy, the notion that Shakespeare's heroes spend a great deal of time talking to themselves and, in a kind of spiritual striptease, revealing their true selves to us...The problem with all of this is that it has almost nothing to do with the kind of theatre that Shakespeare created...In Shakespeare's theatre there is no convention which says that an actor cannot notice and address the audience. On the contrary, the audience is noticed, winked at, teased and made aware of itself.

3. So What is Tragedy?

Shakespeare, as we have seen, chose to ignore the Aristotelian rules for tragedy, and it is therefore absurd to analyse Shakespeare's tragedies as if they were versions of the Greek model. It's not that Shakespeare didn't know the rules. He positively decided that a different kind of theatre was needed if he was to successfully dramatize his own society. The most famous work of literary criticism of Elizabethan England was Sir Philip Sidney's Defence of Poesie. In it Sidney laid down the Aristotelian rules: 'The stage should always represent but one place, and the uttermost time presupposed in it should be, both by Aristotle's precept and common reason, but one day. Moreover tragedy and comedy must be kept severely apart and the playwright should not thrust in the clown by head and shoulders to play a part in majestical matters.' Shakespeare, of course, broke all of these rules and knew he was breaking them. He presents a kaleidoscope of places and a broad sweep of time. His clowns are always thrusting their way into majestical matters. He didn't break the rules, though, because he wasn't up to writing classical plays on the Greek and Roman lines. He could do it if he wanted to: The Comedy of Errors uses a single place and a single day. Julius Caesar is a perfect classical tragedy. He broke them because they were not good enough to deal with the complexities of the world he was living in. Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear and Othello are tragedies but tragedies of a kind which cannot be analysed in terms of tragic flaws and tragic heroes. To understand what kind of tragedies they are, we have to understand what kind of world they were intended to reflect.

Successful tragedy is not particularly common in the long history of the theatre. It gets written only at certain times, times when there is an overwhelming tension between two sets of values, two world views, two ways of thinking about how individuals relate to their societies. The tragic figures are those who get caught in the middle between these two world views, and who therefore literally can do nothing right. They can do nothing right because what is right in one world is not right in another. They act according to one set of values in a world that is still dominated by a different set of values. Clear distinctions, the borders between things that are supposed to be opposite, are breaking down. The interesting and dramatic thing about people in a tragedy is that they are caught on those borders.

What was England like in Shakespeare's time? For one thing it was highly stratified and the division between rich and poor was overwhelmingly obvious...The social elite of Shakespeare's time was highly educated...But at the same time between half and two thirds of the adult population was unable to read. There was no simple, unified, primitive world, therefore, but a highly divided and diverse society, where social and intellectual change had long been at work, moving in many different directions. It was a world of religious, geographical and economic novelties, where, at the same time, the pull of the old order was still powerful. This sense of large, incompatible forces rubbing up against each other has been captured by the great Shakespeare director Grigori Kozintsev: 'Everything was shuffled – the groan of death with the cry of birth. The lash whistled in medieval torture chambers, but the click of abacus balls was heard all the louder. Feudal outlaws discussed the price of wool, and rumours about the success of Flemish textiles were intermingled with authentic details of the witches' Sabbath.'

So what should be the most obvious thing about Shakespeare's time is that it is a period of rapid change, of the transition between one world view and another...It was certainly obvious to Shakespeare's contemporaries that they were living through a period of crisis. Five years before Shakespeare's death, the poet John Donne wrote that:

'Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone; All just supply and all relation: Prince, subject, father, son, are things forgot...

Looking at his and Shakespeare's England, Donne saw a world in which all order and coherence had fallen apart, in which the hierarchy of relations both within the state and within the family was breaking down...His poem could also have been an exact description of Shakespeare's tragedies, of the interrelated breakdown of family and state in each of them, of the phoenix-like Lear and Hamlet and Macbeth and Othello, each believing that he is a self-made man, that he owes his individuality not to his status but to his free will. Their tragedy is that their world is not yet quite like that, that the pull of order and hierarchy is still very strong, not least within their own minds. The tragedies are about the conflict between status on the one hand and individual power on the other, and what dooms Othello, Lear, Macbeth and Hamlet is that for none of them do status and power go together at the same time.

Shakespeare's age is one in which a whole new class, the capitalist and professional middle class, comes to substantial power and prominence in England...These people in turn brought the new humanist Renaissance ideas into vogue in England. Both economically and intellectually, therefore, the fixed hierarchy of the old feudal order was being challenged as never before. There are two value systems, two world views in competition, and this is the essential context in which to understand Shakespeare's tragedies.

The extent of the changes which were underway in Shakespeare's times cannot be overstated. James I, who was on the throne when all of the major tragedies except Hamlet were written, preached that kings ruled by Divine Right and many political writers argued that the property of every subject should be completely at the disposal of the king. Within thirty-five years of Shakespeare's death, the English had executed their king and politics was being conducted as a rational inquiry...In Shakespeare's time, the earth was the centre of a universe in which God and the Devil continuously intervened. In the second half of the century in which the tragedies were written, Newton would show the universe to be a self-moving machine. A world in which everything, both natural and supernatural, had its proper place and category, was giving way to one in which both society and the universe seemed to be made up of competing atoms. Shakespeare's tragedies were written at a time when nothing less than a fundamental reordering of our understanding of the world, the categories by which we make sense of our experience, was in progress. The plays contain and dramatize that reordering and to fail to understand this is to fail to understand the plays.

Shakespeare can properly be described as part of the English Renaissance but only if the Renaissance is understood in certain ways...The repossession of Greek and Roman antiquity is not so much a statement of continuity, of the continuance of classical into modern Europe. It is the opposite, for to repossess something implies a recognition of precisely how different it is from your own culture...Shakespeare is a Renaissance writer only in the sense that he is aware of the extent to which nothing is absolute. In the tragedies there is an overwhelming feeling that all of the most basic values of society have become relative.

This raises another of the hoary clichés about Shakespeare that most of us acquire in our schooldays. It is an article of faith, again taken from Aristotle, that in Shakespearian tragedy the downfall of the hero must seem inevitable...But this is almost completely untrue of Shakespeare. In Shakespeare there is no cold logic and indeed no logic at all. It is not inevitable that Othello should kill Desdemona, indeed it is amazing that he should do so. It is not inevitable that Cordelia should be hanged, indeed the whole point is that it is utterly gratuitous...Shakespeare on the other hand gives us a relative world, a world in which causes don't have their effects, in which almost nothing is predictable, never mind inevitable.

In all four of the major tragedies, the central figure is someone who loses a sense of himself, whose grip on his own identity becomes weaker and weaker...This reflects the fact that in Shakespeare's time there is a transition in the whole way in which one's identity is defined. In feudal, medieval society, your identity is your role, and your role is determined by your birth and position...In the kind of commercial, capitalist world which is emerging in Shakespeare's time, you are your power. Your identity is the sum of your achievements. It is something you make for yourself. You are what you do. The tragedy of Lear and Macbeth, of Hamlet and Othello, is that they think they operate according to both of these principles, that they can base themselves both on a world of status and a world of power, even though these two worlds are contradictory and in active conflict.

It is the fate of these four men to enjoy either status or power, but never both together. Hamlet, as a royal prince who has been denied succession to the throne, has status but not power. Othello, as a mercenary general admired for his skill but disdained for his colour, has power but no status. Lear, keeping the title of king but not the reality of the office, has status but no power. Macbeth, killing Duncan, gains power but not status...

Shakespeare, of course, doesn't present us with abstractions called 'power' and 'status' in his plays; he gives us people trying to live their lives. And the way this conflict is played out is in the relationship between men and women...With the women representing one set of values and the men another, it is hardly surprising that men and women cannot function together in any kind of wholeness in these plays, that the sexual order as well as the social and political order, breaks down.

This is why images of childlessness, of sterility, of the lack of continuity between the generations, are such powerful images in these tragedies. If men and women cannot fit together in harmony, then sterility looms...When Macbeth himself wants to express the ultimate horror he can imagine, it is the killing of the seeds of future generations: 'though the treasure of all nature's germens tumble together / Even till destruction sicken.' And the very same image appears at the climax of King Lear. 'Crack nature's molds, all germens spill at once.' In Shakespeare's tragedies, things are changing so fast that the whole idea of human continuity seems to be threatened. There is even, in King Lear, a powerful sense that the end of the world may be at hand.

It is not, though, just the content and the imagery of Shakespeare's tragedies that is shaped by the extremely fluid nature of the world he lives in, it is also the kind of poetry he writes...The whole nature of the poetry embodies the contradictions that Shakespeare is dramatizing: the opposition between order on the one hand and individuality on the other, between feudalism and capitalism. And it is precisely the containing power of this poetry, its extraordinary inclusiveness, that gives the tragedies their formal rigour, the feeling that in spite of the fierce tensions they contain, they are still finished, ordered works of art. The plays invoke chaos without themselves being chaotic.

4. Toads, Toenails and Puritans

The momentous social changes that were taking place in Shakespeare's time help us to understand the kind of conflicts that are going on in his plays. But they don't really tell us all that much about the way the plays work, about how they affect us, about what it is that we feel in watching the plays and why. To understand that we have to ask how the conflicts of Shakespeare's time could be expressed in ways that would seem to have a powerful gut effect on us. And to do that we have to understand something about the nature of tragedy as a social ritual.

All societies, whether they are what we would regard as primitive, tribal societies, or as modern sophisticated ones, have their rituals, and in general these rituals have similar functions. The main function of public rituals is to help us to put an order on our experience, to give us categories through which we can make sense of the multiplicity of the world in which we live. Rituals are basically systems of classification, the simplest ones being organized around the most basic oppositions: left and right, Black and white, male and female. They classify things as either one thing or the other, making us comfortable with our experience. And in all societies which have rituals, therefore, things that defy categorization, that slip between opposites, that refuse to be one thing or the other, are dangerous and powerful. Shakespeare's tragic protagonists are just such things, and his tragedies are rituals in which those dangerous and powerful things are contained.

Shakespeare's tragedies come from a culture in which the whole idea of ritual is very much a public question. He writes at the time of the Protestant Reformation, a reformation which presents itself as a deliberate attempt to take the ritual out of religion, to destroy the idea that public religious ceremonies have any ritual or magical function. Significantly, the most radical of the Protestants, the Puritans, saw theatre in the same category as superstitions and rituals, wanting to take the theatricality out of religion and then, after Shakespeare's death, to ban theatre altogether, a step that was absolutely in line with their attitude to religious ceremony.

It's important to realize that for the people of Shakespeare's time and before, religion was not so much a set of beliefs as a set of rituals, and that therefore the loss of those rituals with the rise of Protestantism left a large gap to be filled. As the historian Keith Thomas has put it 'The church was important… not because of its formalised code of belief but because its rites were an essential accompaniment to the important events in… life – birth, marriage, death… Religion was a ritual method of living, not a set of dogmas.' With the changeover to Protestantism, the religious rituals were abandoned or reduced, but the anxieties which created the need for them had not disappeared: 'the fluctuations of nature, the hazards of fire, the threat of plague and disease, the fear of evil spirits, and all the uncertainties of daily life'. And indeed to all of these uncertainties was added the uncertainty of unprecedented economic, political and cultural change. There were needs and no rituals to fill them. The theatre, and in particular Shakespeare, was one way of providing for that need.

In creating his tragedies as secular rituals, Shakespeare shows all categories, all basic opposites, breaking down. In the tragedies, the basic opposites by which we are able to make sense of things – life and death, Black and white, man and woman – melt into each other. Shakespeare is dealing with a world that is reordering its knowledge, with the rise of a class whose first triumphant assault on power 150 years later will be, not the storming of the Bastille, but the writing, by Diderot and D'Alembert, of an Encyclopaedia, a new classification of everything that is known. But in Shakespeare's time, that new classification has not yet emerged. The Summa Theologica of Saint Thomas Aquinas, which classified all knowledge for the medieval world, is no longer good enough, and the Encyclopaedia of Diderot and D'Alembert has not yet been written. Since there is no satisfactory way of categorizing experience, things refuse to hold their identity and begin to slip into each other, becoming both powerful and dangerous. It is just such things that rituals are there to deal with and it is just such things that make up Shakespeare's tragedies. Things and people which refuse to stay within their proper boundaries both fascinate and horrify us...In-between animals, those that are neither fish nor flesh, take on special meaning and ritual value. Similarly, toenails or hair, those things which are on the border between ourselves and the material world outside us, go into magic potions. The animals in the witches' brew in Macbeth – toads, cats, hedge pigs, snakes, newts, frogs, bats, lizards – are all ambiguous as either reptiles or half-domestic, half-wild. It is not for nothing that the witches chant 'Double, double': all of these things have double meanings and are therefore dangerous. Throughout the tragedies, as we shall see in looking at the individual plays, the imagery is of snakes, monsters, humans turning into animals and animals turning into humans, creatures that exist on the dangerous borders between categories. The plays themselves are a kind of witches' brew, where dangerous visions are conjured up in a powerful ritual.

For what is true of animals is even more true of people. Rituals everywhere are very concerned with people who go beyond the normal boundaries, who escape from their proper categories...Most obviously, this is what happens to King Lear, but in all of the tragedies (though in Othello less than the others, for reasons which will be discussed in the chapter on that play) there are marginal figures, people who are neither one thing nor the other – ghosts, witches, Banquo's unborn heirs, the dead Yorick in Hamlet who is momentarily brought back to life, Poor Tom in the heath scene in King Lear.

The protagonists of Shakespeare's tragedies themselves conform to what the anthropologist Mary Douglas has to say about figures who take on ritual significance in tribal societies, who are both dangerous and fascinating: 'Danger lies in transitional states, simply because transition is neither one state nor the next, it is indefinable.' Living in a time of transition, Shakespeare gives us tragic protagonists who are dangerous and powerful, who slip between all the categories of our experience, and who therefore draw us into the fundamental power of ritual. It is not because we can define their characters that Shakespeare's people are interesting to us, but because they are literally indefinable, eluding and denying definition in a deliberate and systematic way. It is not because they teach us lessons that we care about them, but because they enact something that is dangerous, powerful and disturbing.

I was going to write ‘greasy’ pole, but that’s politics and that is greasy. Just ask Peter Dutton or even someone who has done their job well - like Zoe Daniel. By contrast in the bureaucracy, as you rise, if you don’t do anything too egregious, you maintain your rank as if it were a non-transferable property right no matter how useless or venal you are.

Please read David Nirenberg's analysis of "The Merchant of Venice" in "Anti-Judaism" which is written by someone whose specialty is medieval Jewish history specifically in Spain. In Shakespeare's time it does not make sense to talk about capitalism as such but it makes sense to talk about economic institutions being born that capitalism and capitalistic government structures will make use of later. For instance the very notion of "population" that government is responsible for is a ~17th-century invention.