OK, now we’ve got that out of the way, on with the show.

I recently published the audio of a discussion between me and Rory Sutherland with me hoping into all that malarkey about looking at things through a ‘systems’ or ‘complexity’ lens. In the words of Lord Wellington, if you believe that, you’ll believe anything. Anyway, a lot of people do. Anyway, the thing is that for reasons that have only ever been explained by looking through a self-organising system lens, (or could it be a ‘nuance’ lens?) videos of discussions often get watched a lot more than audios get listened to. Yes, I know it seems improbable, but not if you look at it through an improbability lens. In any event, here’s the video of the said conversation. And it was a lot of fun

Seeing through a ‘complexity lens’ and other nonsense

Saul Eslake on inequality

A good article on inequality - particularly rising intergenerational and wealth inequality - by Saul Eslake calls for estate taxes on large estates. Certainly one of the fairest taxes around if you believe in equality of opportunity. But less so if you’re only pretending to believe in equality of opportunity.

Mainstream Australian economists — including me — haven't thought, spoken or written as much about the causes and consequences of increasing inequality as perhaps we should have done.

International institutions including the IMF and the OECD have come to recognise that increasing inequality has adverse economic and political consequences...

Australia has done a reasonably good job of preventing the distribution of income from becoming more unequal. The share of total household income accruing to the top 1 per cent, or even the top 10 per cent, of households has actually declined over the past fifteen or so years...

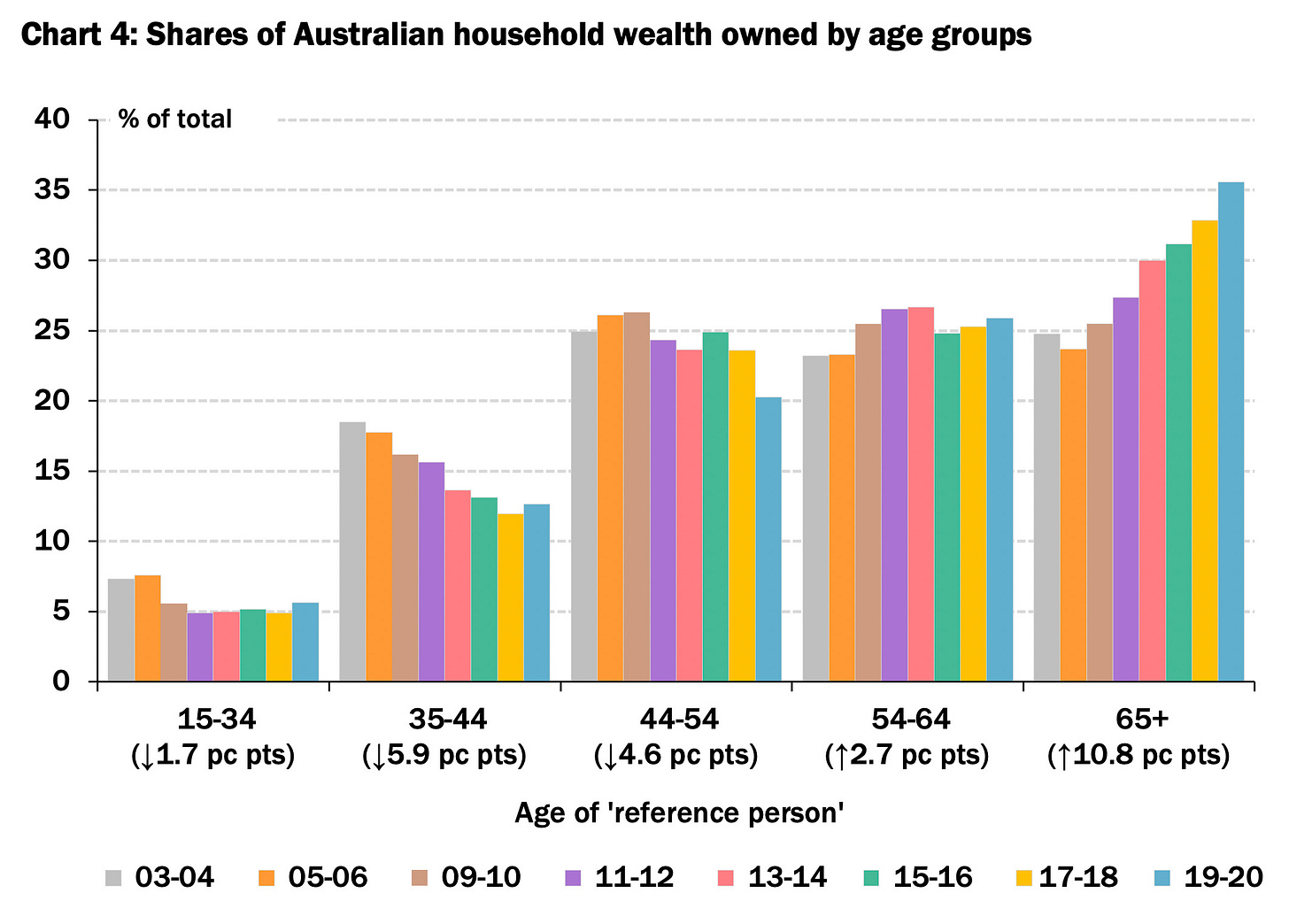

to forty-four and forty-five to fifty-four fell by 1.7, 5.9 and 4.6 percentage points respectively between 2003–04 and 2019–20.

It is to be expected, of course, that older households will be richer than younger ones on average, since they have had longer to accumulate income and generate wealth... But the ageing of Australia's population doesn't go anywhere near fully accounting for the extraordinary increase in the share of household wealth owned by older households over the past two decades...

A particularly important contributor to increasing wealth inequality across age groups has been the decline in home ownership rates among younger households... [T]he home ownership rate among people aged between twenty-five and thirty-four fell from a peak of 61 per cent at the 1981 census to 43 per cent in 2021... [A] far more important factor has been the decline in housing affordability... it now takes someone on the median household income almost eleven years to accumulate a 20 per cent deposit on a median-priced dwelling, almost three times as long as in 1984.

Another important factor has been the series of conscious decisions by successive Australian governments to allow older people to pay less tax than younger people... Thus, in 2019–20, households where the reference person was sixty-five or older made up 25.5 per cent of the number of households, earned 16.7 per cent of total household income and owned 43.4 per cent of total household wealth — but paid just 7.4 per cent of total personal income tax...

What could be done to reverse this trend?

Given the role home ownership traditionally played in allowing a broad spectrum of the population to accumulate wealth and, in particular, secure some degree of security in retirement, the most important thing would be to reverse the slide in home ownership among younger age groups.

In recent years governments of both major political persuasions have adopted the view that the best way of reversing the deterioration in housing affordability is by boosting the supply of housing. Yet both major parties have been extraordinarily reluctant to back away from policies that inflate the demand for housing...

To curb increasing wealth inequality across age groups, governments should also reduce the concessional tax treatment of the types of income that disproportionately accrue to older and wealthier taxpayers — particularly the treatment of capital gains, dividends and superannuation earnings and payments.

Finally, governments could consider reintroducing some form of taxation of inheritances or bequests — especially given the scale of wealth likely to be bequeathed to their children by Baby Boomers, which some estimates put at almost $5.5 trillion.

Although such a tax would inevitably be depicted as "socialism" (or worse) by politicians and commentators across the spectrum, Australia is actually something of an outlier among OECD countries in not having any form of inheritance taxation... Given that some 64 per cent of inheritances in Australia go to people aged fifty-five or over, most of whom are already in the upper half of the wealth distribution, a tax on inheritances of more than (say) $3 million — with an exemption for surviving spouses or partners, and perhaps with some incentives for bequests to registered charities — would likely make a useful contribution to curbing the seemingly inexorable upward trend in the concentration of wealth in older and wealthier hands.

Increasing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth has adverse economic and political consequences. Economists should be doing more to bring those to the attention of the Australian public, and to propose politically workable solutions.

Henry Ergas on defence procurement

This is a good, informative column by Henry Ergas, but I can’t help thinking that in such a complex situation, actually producing a program that makes simple sense - in which high level strategy actually guides lower level decisions - is now well nigh impossible. Governments react to stakeholders and try to keep them happy. That’s pretty much the only hard constraint on anyone in government at the political or bureaucratic level.

Doing it coherently? Well that’s extra, and who’s making you do that? Better just to keep making the same mistakes forever. After all, as Henry points out, reviews are rarely followed up. This mirrors my own experience in quite different areas. We announce our decision to ‘close the gap’ or whatever. But rather than start from where we last promised to do that and figure out how we’re going to do better than last time, we just do it all again.

As Henry puts it “we don't have 50 years' experience of modern defence procurement; we have one year, 50 times over.” Ditto pretty much everywhere else. As I tried to indicate in my own lament on over a decade of effort in seeking to improve programs to address social disadvantage with so little to show for it, we need first to build a system that tells itself the truth. And that’s a tall order when the only real imperatives are to keep up appearances.

Some years ago, Mark Thomson, the then senior economist at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and I systematically examined the reviews that had been carried out of the efficiency with which the Australian Defence Force's major weapons systems are acquired and maintained. Now, as pressures mount for what would be a near doubling in defence expenditure, the lessons that emerged seem timelier than ever.

There was no shortage of documentation: in 2011-12 alone there were 22 defence-related reviews (though that was admittedly a year when the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd government was doing its thing). While their quality varied greatly, those dealing with the selection, acquisition and sustainment of materiel were typically careful and comprehensive.

Virtually every review pointed to deficiencies in the Defence Department's management systems. There were countless plans, but no plan; myriad accountabilities, but no accountability.

The result was a structure in which decisions were poorly integrated. Individuals knew what they were intended to do but were not fully responsible for its being done. Meanwhile, Defence's tracking systems generated torrents of information, but its sheer scale, and the lack of tight connection between decisions on the one hand and what was measured on the other, drastically undermined that information's usefulness.

For example, the Coles review of the sustainment program for the Collins-class submarines noted an instance in which "a junior officer (was) required to render a very detailed progress report every day, which was sent to over 100 recipients". Few presumably reading it, and even fewer would have felt any sense of responsibility for the progress it supposedly tracked...

The defence estimates would no longer be "an adding machine for aggregating the intentions of the army, navy and air forces, with limited knowledge of the purposes that expenditure is serving". They would reflect a rational assessment of costs and benefits, based on trade-offs that were systematically evaluated and frequently updated. That scrutiny would extend to the defence industrial base, more carefully targeting support to critical requirements.

But despite an imposing machinery designed to undertake those assessments, there was little evidence in the reviews of that kind of careful consideration. Rather, the "lessons learned" study that a team from the RAND Corporation carried out of the Collins project would lead one to think that Mr Murphy, of the eponymous law, was an incorrigible optimist, at least as far as major defence ventures were concerned...

Additionally, problems were frequently ignored, making them harder to fix. To take but one example, the review undertaken by Paul Rizzo of naval sustainment pointed to "poor whole-of-life asset management, blurred accountabilities, inadequate risk management, poor compliance and assurance, and a culture that places the short-term operational mission above the need for technical integrity".

As if that was not bad enough, the review noted that all the failures were "longstanding, well known to Defence, and the subject of many prior reports". Nor is that unusual: the reviews almost invariably found that the issues had persisted for years.

There have, for sure, been many remedial efforts in response to those reviews and others. While the changes usually seem sensible, it is difficult, if not impossible, to know whether or not they worked, individually and collectively. In effect, reviews were rarely followed up, in the sense of retrospective assessments ("post-mortems") that rigorously examined the effectiveness of the changes they had introduced...

There has been nothing in Australia that even vaguely compares to [the US comprehensive] appraisal. To make things worse, there has been no attempt, along the lines of the US Defence Department's magnificent, recently concluded, five-volume history of defence acquisition, to comprehensively survey the evolution of defence budgeting, acquisition decision-making and implementation.

That would not only be an invaluable resource for those trying to navigate the system; it would make the successes and failures clearer. Without that institutionalised memory and reflection, we don't have 50 years' experience of modern defence procurement; we have one year, 50 times over.

It would be useful too if there were regular comparisons between our approaches and those of best-practice performers, such as Israel, whose capacity to develop and adapt new weapons systems remains extraordinary. As Bismarck observed long ago, "Fools learn from experience; wise men learn from the experience of others"...

It was nonetheless clear from the reviews that we could do better – much better. Judging by the information publicly available, that largely remains the case. The risk the current focus on the ratio of defence spending to GDP creates is that instead of tackling the root causes of the shortcomings we will, as in education, simply throw money at the symptoms.

That would be about as sensible as turning up the volume on a faulty amplifier. Yes, there are, as ASPI has compellingly argued, dangerous weaknesses in our defence capabilities. But it will take far more than a flood of taxpayer dollars to set them right.

Defending Australia

I’d be happy to spend more than Sam Roggeveen wants to. But I’d start as he would. Save on big expensive targets. The subs won’t be targets at all, but that’s because we won’t get any. Makes not paying for them look like the best deal we can get - which should save some money at least. I’d say that an increasingly unstable, multi-polar world would be enough to tip the scales toward more expenditure, but in addition, the reliability of our major ally has just collapsed.

There is near universal agreement that Australia should spend more money on defence. The big political parties want to spend more. The defence commentariat overwhelmingly agrees. And earlier this week, the United States made its views plain, with Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth curtly telling Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles that "Australia should increase its defence spending to 3.5 per cent of its GDP as soon as possible."

Don't get too hung up on the figures – measuring defence spending as a percentage of GDP is a ropey business. But for the record, the government has pledged to raise defence spending to 2.4 per cent, and at the last election, the Liberal Party said it would go to 3 per cent within a decade. Given that current spending is just over 2 per cent of GDP, moving up to 3.5 per cent is a major lift that would require the government to either borrow more, cut spending, increase taxation, or all three. Neither side of politics has the political will for that...

It is argued that Australia needs to spend more to keep the United States happy - Shadow Defence Minister Angus Taylor, for instance, says Australia needs to "carry our weight". The US is constantly poking and prodding its allies to take on more of the burden, and although Australia has historically been exempted from such harangues, the prickly tenor of Hegseth's remarks suggests those days are over.

But don't forget, that's Hegseth talking, not his boss. The Defence Secretary clearly belongs in the "prioritiser" school of Trump advisers, those who want to reduce the US military footprint in Europe and the Middle East to focus on China. But Trump shows no evidence of wanting to confront China militarily. As Hugh White says in his new Quarterly Essay, "Republican China hawks imagine that Trump has deserted Ukraine, abandoned Europe and courted Putin so that he can focus on defeating China to defend US regional and global leadership. But Trump has never believed that any of that really matters for America."

Trump has a much narrower conception of America's defence interests. Sure, he wants the US to be globally feared, but he has a hemispheric focus: Canada, Greenland, Panama, Mexico and the continental United States with the "Golden Dome" missile defence system are his pre-occupations. To paraphrase Trump, Australia isn't terribly relevant because it is separated from the United States by a big, beautiful ocean. The only way Australia can help America is if you assume that the US has vital security interests in Asia. But since Trump does not believe this, why should Australia?...

Finally, we should talk about a surprisingly neglected topic: the threat. The only real reason to raise defence spending is if you think the danger of military attack has gone up. Has it?

Governments led by both major parties have produced policy papers which go some way to describing an increased threat from China. But governments tend to be coy about details, since there would be diplomatic repercussions if Australia was too explicit about its fears.

Defence commentators don't have that excuse, yet to my knowledge, no major piece of research has been produced which details the military threat China poses to Australia. In late 2023, I published a book which devotes a chapter to examining the specifics of how China could attack Australia. I'm involved in a project which updates those findings, to be published later this year. I'm not aware of anyone else doing similar work. Given the clamour for higher defence spending, this is a strange state of affairs.

China's military is formidable, but that's no reason to abandon judgments about Australia's defence that have stood the test of time. Defence planners have long recognised that the only way to project serious amounts of military force against Australia is to cross the vast sea-air gap to the north. Australia's mission should be to defend that sea-air gap by maintaining forces which can shoot down planes and missiles, and sink ships and submarines, that encroach upon it.

That's a difficult but achievable task for Australia. We don't need to spend more to do it, but we do need to spend our defence dollars differently.

It ain’t what you know: How elites trump experts

Rob Henderson wrote recently about the differing roles of elites and experts, a distinction I associate with Robin Hanson. Henderson does acknowledge Hanson, but I didn’t see anything much new that Henderson added. Anyway, if you don’t know the distinction you should. (You’re welcome!)

Thinking about the content here, you might almost say that the neoliberalisation of higher education and research has placed experts ever more meekly at the disposal of elites, and erected a few more institutional barriers to the speaking of truth to power. Perhaps those political philosophers of the ancient world knew a thing or two by suggesting that flattery of the powerful is a core political problem. As the slave was wont to say during the triumph, memento mori.

When elites don’t care about a topic, experts are in charge. They set the norms, make the decisions, and everyone defers to their judgment. But the moment elites start paying attention—once they form a consensus—they take over.

You saw this during the Covid pandemic. Early on, many physicians and health experts were skeptical about lockdowns, travel bans, and masks. Then global elites started talking—governments, media, institutional heads—and settled on a different line. Almost overnight, the official expert view flipped to match the elite view. The messaging changed, and everyone followed.

Pandemic experts had access to decades, even centuries, of historical precedent and protocol. But as soon as elites aligned on what they wanted, the experts fell in line. It was instant. The kind of abrupt reversal that feels like something out of 1984. One day it’s “We never said that.” The next, it’s “We’ve always said that.”

When elites change their minds, the institutions and the experts within them usually follow.

I remember listening to a podcast in 2020 where two physicians discussed how strange it was to isolate healthy people during a pandemic, whereas in every other pandemic in history only the sick were quarantined. Elites called the shots and most experts went along with it.

You can see the elite/expert split in other arenas. Criminologists who track victimization surveys and randomized patrol experiments have long found that visible, data-driven policing deters violent crime. Yet elite commentators often champion “defund” slogans or broad-brush bans on proactive policing because those positions resonate with their social peers and align with their political commitments. The pattern is consistent: experts uncover important details, while elites curate narratives that feel morally and socially acceptable—often steering policy away from what the evidence actually supports.

We like to pretend that anyone can speak up, offer ideas, or take action. But in practice, we tend to accept important moves only when they come from elites. And even then, only when they’re delivered in the “correct” elite style.

Upgrading unideological thinking

I’ve previously talked about the way I prick up my ears if someone’s arguing against their ideological priors. That’s usually high signal - low noise. Brian Caplan makes a similar point here about mood.

Last month, I argued that people's moods provide information about their reliability:

Yes, the desire to feel any specific mood can lead people into error. At the same time, however, some moods are symptoms of error, and others are symptoms of accuracy.

When someone expresses his views with a calm mood, you consider him more reliable than when he expresses his views with an hysterical mood... As far as I can tell, this is justified.

In sum:

You can learn a lot by comparing the mood reasonable proponents would hold to the mood actual proponents do hold.

How important is this insight in the real world? Very. For many popular positions, the reasonable mood is virtually invisible. For your consideration…

1. The hawk

Modern warfare almost always leads to killing lots of innocents; if governments were held to the same standards as individuals, these killings would be manslaughter, if not murder. This doesn't mean that war is never justified. But the reasonable hawkish mood is sorrow – and constant yearning for a peaceful path...

I have never personally known a hawk who expresses such moods, and know of none in the public eye. Instead, the standard hawk moods are anger and machismo. Ted Cruz's recent quip, "I don't know if sand can glow in the dark, but we're going to find out" is typical... As a result, I put little weight on what hawks say. This doesn't mean their view is false, but it is a strong reason to think it's false.

2. The immigration restrictionist

Immigration from the Third World to the First World is almost a fool-proof way to work your way out of poverty. The mechanism: Labor is more productive in the First World than the Third, so migrants generally create the extra riches they consume. This doesn't mean that immigration restrictions are never justified. But the reasonable restrictionist mood is anguish that a tremendous opportunity to enrich mankind and end poverty must go to waste – and pity for the billions punished for the "crime" of choosing the wrong parents...

I have met a couple of restrictionists who privately express this mood, and read a few who hold it publicly. But in percentage terms, they're almost invisible. Instead, the standard restrictionist moods are anger and xenophobia.

3. The proponent of labor market regulation

Labor regulation obviously isn't the main reason why workers receive decent treatment from employers; after all, most workers receive notably better conditions than the law requires. And labor regulation has a clear downside: Forcing employers to treat their employees better reduces the incentive to employ them. This doesn't mean that labor market regulation is never justified, but the reasonable pro-regulation mood is humility about the size of the gains plus wonder that even modest gains are on the table...

This mood is essentially non-existent among non-economists, and rare among pro-regulation economists. The latter, to their credit, take the downsides seriously enough to try to measure them.* But their mood does not inspire trust... This doesn't prove they're wrong, but even the intellectually strongest proponents of labor market regulation are hard to take at face value.

As you can tell, I'm not a hawk, an immigration restrictionist, or supporter of labor market regulation. Are there any "missing moods" that put my views in a negative light? Absolutely. While I'm a pacifist, I'm sad to say that many avowed pacifists actively sympathize with evil regimes they don't want to fight. Similarly, while I think libertarian policies are great for the truly poor, I've often heard libertarians privately sneer at the poor... The prevalence of these moods doesn't prove pacifism and libertarianism false, but both are bona fide reasons for people to distrust pacifists and libertarians. So what? Again: If you have good reason to distrust the messenger, you have good reason to doubt the message.

When you think you lie

Leni Riefenstahl comeback tour

HT: Cousin Ren.

ChatGPT bullshits its way through another day

Speaking of ChatGPT BS

Last week I posted an extract from a post from “Stay Slick”. I got back this diagnosis from reader Reuben Finighan

One of the ways of identifying ChatGPT-written text is the overuse of "it's not X, it's Y", which ChatGPT seems to think is the apex of persuasive communication.

- Archeofuturism wasn't just a worldview. It was an insurgent logic of elite rule

- Guillaume Faye may have dreamed of Europa. But the implementation is happening in America

- Not just a platform—a weapon of cultural soft power

- They didn't just influence power. They bought it.

- This isn't policy reform. It's parallel civilization

- a new sovereign class that doesn't need the nation—just the myth.

- But it wasn't just the ideas that spread; it was the method.

- Faye didn't just theorize power, he weaponized transgression.

- taboo-breaking wasn't provocation—it was initiation.

- It wasn't just speech. It was mythic theatre.

- What was once shocking is now a test.

- it reveals not just belief, but allegiance.

- Not just what you're willing to say, but what you're willing to become.

- Faye believed collapse would filter the weak. But it was transgression that revealed who was willing to rule

- enacted not by nobles in helmets, but by billionaires in hoodies...

- Archeofuturism isn't coming. It's here.

Nearly the whole damn article. Exhausting.

I went back to the site and asked “How much of this was ChatGPT-generated?” the ‘author’ replied “All of it! Just type 'Write me an article about the intellectual scaffolding of the American New Right', copy-paste, and hit Publish... /s.”

Reuben also notes this on another story I extracted.

Also, this major MIT paper investigates the curious increase in the costs of nuclear power in the US and finds that safety is only a minority contributor.

Meanwhile in Tasmania

Bernard Keane sets the scene for the dramas unfolding in Tasmania.

Tasmanian government hopes indebted voters will just watch the footy… at their $945 million stadium

The Tasmanian government's profligacy is on full display in its latest budget, as it commits hundreds of millions to a new stadium while the state is mired in deficit.

In case anyone was thinking fiscal profligacy was purely a Labor disease — or that Crikey was unfair in constantly pointing out how bad the fiscal positions of Victoria and the Commonwealth are — behold last week's budget from the Tasmanian government of Jeremy Rockliff and his Treasurer Guy Barnett.

Not merely is the Rockliff government promising deficits out to 2028-29, the budget represent a marked deterioration since last year's budget — despite increased revenue.

The deficit for the year about to be completed, 2024-25, has blown out by $500 million to nearly $1.3 billion. And the coming financial year's deficit, which last year was forecast as less than $400 million, is now expected to be over $1 billion. And that's despite a $400 million increase in revenue.

It's the same problem as in Canberra, and in Victoria: governments keep increasing spending, without matching it with tax revenue, pushing up debt and building up interest payments into a major budget item...

Instead it's "general government services" that sees a big expansion — with a very long list of relatively small election-style commitments across a variety of portfolios that total up to $350 million of new spending.

That includes $13.2 million to fund the operations of the "Macquarie Point Development Corporation", the spivvy government body charged with developing the prize example of the Tasmanian government's inability to control spending: the new stadium being forced on Tasmania by the Australian Football League. The government willingness to entirely abandon good process around this benighted project was necessitated by the fact that any rigorous assessment of the new stadium reveals how the government has relied on garbage modelling to justify the spending.

And, inevitably, that spending has blown out. Once mooted as costing only $775 million, the stadium will now, the government admits, cost at least $945 million.

The blowout vindicates independent economist Nicholas Gruen, who ripped apart the dodgy modelling behind the original estimate and warned the stadium was more likely to cost just over $1 billion. For that, Gruen was smeared by Hobart journalists and attacked as a partisan aligned with stadium opponents — without anyone managing to find a problem with his sums.

The stadium is a perfect example not merely of the profligacy of a desperate government but of the link between fiscal indiscipline and the abandonment of good policy process. And Tasmanians will continue to pay for it via surging interest payments for many years to come.

Nice digs, nice gear

A fun tour through Michelangelo’s Last Judgement.

Trolling and trawling

Interesting guy: Interesting life

Heaviosity Half hour

Hannah Arendt’s ‘We refugees’

There is something powerfully raw and vivid about Hannah Arendt’s essay that came out in the midst of Europe’s darkness in the Second World War, before the worst horrors inflicted upon the Jews were fully unveiled. Originally published in January 1943 as “We Refugees” in a small Jewish journal called Menorah (shut down in 1961), the piece captures what it really means to be a refugee – the endless anxiety, ravaging despair, deluded optimism, jolting absurdity and even the humour of the “refugee.” What it is to be a wandering individual in search for dignity within a larger collective that “fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies.” Arendt’s larger lesson is poignant: “The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.” A message that projects a long arm into the present and can be read in the current global context that sees indifference and outright hostility to refugees, a political and social attitude that can only come at the price of exacerbating tensions and rupturing the moral fabric of the perpetrators of such indifference and hostility.

“We Refugees”

In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” We ourselves call each other “newcomers” or “immigrants.” Our newspapers are papers for “Americans of German language”; and, as far as I know, there is not and never was any club founded by Hitler-persecuted people whose name indicated that its members were refugees.

A refugee used to be a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some political opinion held. Well, it is true we have had to seek refuge; but we committed no acts and most of us never dreamt of having any radical opinion. With us the meaning of the term “refugee” has changed. Now “refugees” are those of us who have been so unfortunate as to arrive in a new country without means and have to be helped by Refugee Committees.

Before this war broke out we were even more sensitive about being called refugees. We did our best to prove to other people that we were just ordinary immigrants. We declared that we had departed of our own free will to countries of our choice, and we denied that our situation had anything to do with “so-called Jewish problems.” Yes, we were “immigrants” or “newcomers” who had left our country because, one fine day, it no longer suited us to stay, or for purely economic reasons. We wanted to rebuild our lives, that was all. In order to rebuild one’s life one has to be strong and an optimist. So we are very optimistic.

Our optimism, indeed, is admirable, even if we say so ourselves. The story of our struggle has finally become known. We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives in the Polish ghettos and our best friends have been killed in concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives.

Nevertheless, as soon as we were saved—and most of us had to be saved several times—we started our new lives and tried to follow as closely as possible all the good advice our saviors passed on to us. We were told to forget; and we forgot quicker than anybody ever could imagine. In a friendly way we were reminded that the new country would become a new home; and after four weeks in France or six weeks in America, we pretended to be Frenchmen or Americans. The most optimistic among us would even add that their whole former life had been passed in a kind of unconscious exile and only their new country now taught them what a home really looks like. It is true we sometimes raise objections when we are told to forget about our former work; and our former ideals are usually hard to throw over if our social standard is at stake. With the language, however, we find no difficulties: after a single year optimists are convinced they speak English as well as their mother tongue; and after two years they swear solemnly that they speak English better than any other language—their German is a language they hardly remember.

In order to forget more efficiently we rather avoid any allusion to concentration or internment camps we experienced in nearly all European countries—it might be interpreted as pessimism or lack of confidence in the new homeland. Besides, how often have we been told that nobody likes to listen to all that; hell is no longer a religious belief or a fantasy, but something as real as houses and stones and trees. Apparently nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings—the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends.

Even among ourselves we don’t speak about this past. Instead, we have found our own way of mastering an uncertain future. Since everybody plans and wishes and hopes, so do we. Apart from the general human attitudes, however, we try to clear up the future more scientifically. After so much bad luck we want a course as sure as a gun. Therefore, we leave the earth with all its uncertainties behind and we cast our eyes up to the sky. The stars tell us—rather than the newspapers—when Hitler will be defeated and when we shall become American citizens. We think the stars more reliable advisers than all our friends; we learn from the stars when we should have lunch with our benefactors and on what day we have the best chances of filling out one of these countless questionnaires which accompany our present lives. Sometimes we don’t rely even on the stars but rather on the lines of our hand or the signs of our handwriting. Thus we learn less about political events but more about our own dear selves, even though somehow psychoanalysis has gone out of fashion. Those happier times are past when bored ladies and gentlemen of high society conversed about the genial misdemeanors of their early childhood. They don’t want ghost-stories any more; it is real experiences that make their flesh creep. There is no longer any need of bewitching the past; it is spellbound enough in reality. Thus, in spite of our outspoken optimism, we use all sorts of magical tricks to conjure up the spirits of the future.

I don’t know which memories and which thoughts nightly dwell in our dreams. I dare not ask for information, since I, too, had rather be an optimist. But sometimes I imagine that at least nightly we think of our dead or we remember the poems we once loved. I could even understand how our friends of the West coast, during the curfew, should have had such curious notions as to believe that we are not only “prospective citizens” but present “enemy aliens.” In daylight, of course, we become only “technically” enemy aliens—all refugees know this. But when technical reasons prevented you from leaving your home during the dark house, it certainly was not easy to avoid some dark speculations about the relation between technicality and reality.

No, there is something wrong with our optimism. There are those odd optimists among us who, having made a lot of optimistic speeches, go home and turn on the gas or make use of a skyscraper in quite an unexpected way. They seem to prove that our proclaimed cheerfulness is based on a dangerous readiness for death. Brought up in the conviction that life is the highest good and death the greatest dismay, we became witnesses and victims of worse terrors than death—without having been able to discover a higher ideal than life. Thus, although death lost its horror for us, we became neither willing nor capable to risk our lives for a cause. Instead of fighting—or thinking about how to become able to fight back—refugees have got used to wishing death to friends or relatives; if somebody dies, we cheerfully imagine all the trouble he has been saved. Finally many of us end by wishing that we, too, could be saved some trouble, and act accordingly.

Since 1938—since Hitler’s invasion of Austria—we have seen how quickly eloquent optimism could change to speechless pessimism. As time went on, we got worse—even more optimistic and even more inclined to suicide. Austrian Jews under Schuschnigg were such a cheerful people—all impartial observers admired them. It was quite wonderful how deeply convinced they were that nothing could happen to them. But when German troops invaded the country and Gentile neighbours started riots at Jewish homes, Austrian Jews began to commit suicide.

Unlike other suicides, our friends leave no explanation of their deed, no indictment, no charge against a world that had forced a desperate man to talk and to behave cheerfully to his very last day. Letters left by them are conventional, meaningless documents. Thus, funeral orations we make at their open graves are brief, embarrassed and very hopeful. Nobody cares about motives, they seem to be clear to all of us.

I speak of unpopular facts; and it makes things worse that in order to prove my point I do not even dispose of the sole arguments which impress modern people—figures. Even those Jews who furiously deny the existence of the Jewish people give us a fair chance of survival as far as figures are concerned—how else could they prove that only a few Jews are criminals and that many Jews are being killed as good patriots in wartime? Through their effort to save the statistical life of the Jewish people we know that Jews had the lowest suicide rate among all civilized nations. I am quite sure those figures are no longer correct, but I cannot prove it with new figures, though I can certainly with new experiences. This might be sufficient for those skeptical souls who never were quite convinced that the measure of one’s skull gives the exact idea of its content, or that statistics of crime show the exact level of national ethics. Anyhow, wherever European Jews are living today, they no longer behave according to statistical laws. Suicides occur not only among the panic-stricken people in Berlin and Vienna, in Bucharest or Paris, but in New York and Los Angeles, in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

On the other hand, there has been little reported about suicides in the ghettoes and concentration camps themselves. True, we had very few reports at all from Poland, but we have been fairly well informed about German and French concentration camps.

At the camp of Gurs, for instance, where I had the opportunity of spending some time, I heard only once about suicide, and that was the suggestion of a collective action, apparently a kind of protest in order to vex the French. When some of us remarked that we had been shipped there “pour crever” in any case, the general mood turned suddenly into a violent courage of life. The general opinion held that one had to be abnormally asocial and unconcerned about general events if one was still able to interpret the whole accident as personal and individual bad luck and, accordingly, ended one’s life personally and individually. But the same people, as soon as they returned to their own individual lives, being faced with seemingly individual problems, changed once more to this insane optimism which is next door to despair.

We are the first non-religious Jews persecuted—and we are the first ones who, not only in extremis, answer with suicide. Perhaps the philosophers are right who teach that suicide is the last and supreme guarantee of human freedom; not being free to create our lives or the world in which we live, we nevertheless are free to throw life away and to leave the world. Pious Jews, certainly, cannot realize this negative liberty: they perceive murder in suicide, that is, destruction of what man never is able to make, interference with the rights of the Creator. Adonai nathan veadonai lakach (“The Lord hath given and the Lord hath taken away”); and they would add: baruch shem adonai (“blessed be the name of the Lord”). For them suicide, like murder, means a blasphemous attack on creation as a whole. The man who kills himself asserts that life is not worth living and the world not worth sheltering him.

Yet our suicides are no mad rebels who hurl defiance at life and the world, who try to kill in themselves the whole universe. Theirs is a quiet and modest way of vanishing; they seem to apologize for the violent solution they have found for their personal problems. In their opinion, generally, political events had nothing to do with their individual fate; in good or bad times they would believe solely in their personality. Now they find some mysterious shortcomings in themselves which prevent them from getting along. Having felt entitled from their earliest childhood to a certain social standard, they are failures in their own eyes if this standard cannot be kept any longer. Their optimism is the vain attempt to keep head above water. Behind this front of cheerfulness, they constantly struggle with despair of themselves. Finally, they die of a kind of selfishness.

If we are saved we feel humiliated, and if we are helped we feel degraded. We fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies, since we are afraid of becoming part of that miserable lot of schnorrers whom we, many of us former philanthropists, remember only too well. Just as once we failed to understand that the so-called schnorrer was a symbol of Jewish destiny and not a shlemihl, so today we don’t feel entitled to Jewish solidarity; we cannot realize that we by ourselves are not so much concerned as the whole Jewish people. Sometimes this lack of comprehension has been strongly supported by our protectors. Thus, I remember a director of a great charity concern in Paris who, whenever he received the card of a German-Jewish intellectual with the inevitable “Dr.” on it, used to exclaim at the top of his voice, “Herr Doktor, Herr Doktor, Herr Schnorrer, Herr Schnorrer!”

The conclusion we drew from such unpleasant experiences was simple enough. To be a doctor of philosophy no longer satisfied us; and we learnt that in order to build a new life, one has first to improve on the old one. A nice little fairy-tale has been invented to describe our behaviour; a forlorn émigré dachshund, in his grief, begins to speak: “Once, when I was a St. Bernard …”

Our new friends, rather overwhelmed by so many stars and famous men, hardly understand that at the basis of all our descriptions of past splendors lies one human truth: once we were somebodies about whom people cared, we were loved by friends, and even known by landlords as paying our rent regularly. Once we could buy our food and ride in the subway without being told we were undesirable. We have become a little hysterical since newspapermen started detecting us and telling us publicly to stop being disagreeable when shopping for milk and bread. We wonder how it can be done; we already are so damnably careful in every moment of our daily lives to avoid anybody guessing who we are, what kind of passport we have, where our birth certificates were filled out—and that Hitler didn’t like us. We try the best we can to fit into a world where you have to be sort of politically minded when you buy your food.

Under such circumstances, St. Bernard grows bigger and bigger. I never can forget that young man who, when expected to accept a certain kind of work, sighed out, “You don’t know to whom you speak; I was Section-manager in Karstadt’s [A great department store in Berlin].” But there is also the deep despair of that middle-aged man who, going through countless shifts of different committees in order to be saved, finally exclaimed, “And nobody here knows who I am!” Since nobody would treat him as a dignified human being, he began sending cables to great personalities and his big relations. He learnt quickly that in this mad world it is much easier to be accepted as a “great man” than as a human being.

The less we are free to decide who we are or to live as we like, the more we try to put up a front, to hide the facts, and to play roles. We were expelled from Germany because we were Jews. But having hardly crossed the French borderline, we were changed into “boches.” We were even told that we had to accept this designation if we really were against Hitler’s racial theories. During seven years we played the ridiculous role of trying to be Frenchmen—at least, prospective citizens; but at the beginning of the war we were interned as “boches” all the same. In the meantime, however, most of us had indeed become such loyal Frenchmen that we could not even criticise a French governmental order; thus we declared it as all right to be interned. We were the first “prisonniers volontaires” history has ever seen. After the Germans invaded the country, the French Government had only to change the name of the firm; having been jailed because we were Germans, we were not freed because we were Jews.

It is the same story all over the world, repeated again and again. In Europe the Nazis confiscated our property; but in Brazil we have to pay 30% of our wealth, like the most loyal member of the Bund der Auslandsdeutschen. In Paris we could not leave our homes after eight o’clock because we were Jews; but in Los Angeles we are restricted because we are “enemy aliens.” Our identity is changed so frequently that nobody can find out who we actually are.

Unfortunately, things don’t look any better when we meet with Jews. French Jewry was absolutely convinced that all Jews coming from beyond the Rhine were what they called Polaks—what German Jewry called Ostjuden. But those Jews who really came from eastern Europe could not agree with their French brethren and called us Jaeckes. The sons of these Jaecke-haters—the second generation born in France and already duly assimilated—shared the opinion of the French Jewish upper class. Thus, in the very same family, you could be called a Jaecke by the father and a Polak by the son.

Since the outbreak of the war and the catastrophe that has befallen European Jewry, the mere fact of being a refugee has prevented our mingling with native Jewish society, some exceptions only proving the rule. These unwritten social laws, though never publicly admitted, have the great force of public opinion. And such a silent opinion and practice is more important for our daily lives than all official proclamations of hospitality and good will.

Man is a social animal and life is not easy for him when social ties are cut off. Moral standards are much easier kept in the texture of a society. Very few individuals have the strength to conserve their own integrity if their social, political and legal status is completely confused. Lacking the courage to fight for a change of our social and legal status, we have decided instead, so many of us, to try a change of identity. And this curious behavior makes matters much worse. The confusion in which we live is partly our own work.

Some day somebody will write the true story of this Jewish emigration from Germany; and he will have to start with a description of that Mr. Cohn from Berlin who had always been a 150% German, a German super-patriot. In 1933 that Mr. Cohn found refuge in Prague and very quickly became a convinced Czech patriot—as true and loyal a Czech patriot as he had been a German one. Time went on and about 1937 the Czech Government, already under some Nazi pressure, began to expel its Jewish refugees, disregarding the fact that they felt so strongly as prospective Czech citizens. Our Mr. Cohn then went to Vienna; to adjust oneself there a definite Austrian patriotism was required. The German invasion forced Mr. Cohn out of that country. He arrived in Paris at a bad moment and he never did receive a regular residence-permit. Having already acquired a great skill in wishful thinking, he refused to take mere administrative measures seriously, convinced that he would spend his future life in France. Therefore, he prepared his adjustment to the French nation by identifying himself with “our” ancestor Vercingetorix. I think I had better not dilate on the further adventures of Mr. Cohn. As long as Mr. Cohn can’t make up his mind to be what he actually is, a Jew, nobody can foretell all the mad changes he will have to go through.

A man who wants to lose his self discovers, indeed, the possibilities of human existence, which are infinite, as infinite as is creation. But the recovering of a new personality is as difficult—and as hopeless—as a new creation fo the world. Whatever we do, whatever we pretend to be, we reveal nothing but our insane desire to be changed, not to be Jews. All our activities are directed to attain this aim: we don’t want to be refugees, since we don’t want to be Jews; we pretend to be English-speaking people, since German-speaking immigrants of recent years are marked as Jews; we don’t call ourselves stateless, since the majority of stateless people in the world are Jews; we are willing to become loyal Hottentots, only to hide the fact that we are Jews. We don’t succeed and we can’t succeed; under the cover of our “optimism” you can easily detect the hopeless sadness of assimilationists.

With us from Germany the word assimilation received a “deep” philosophical meaning. You can hardly realize how serious we were about it. Assimilation did not mean the necessary adjustment to the country where we happened to be born and to the people whose language we happened to speak. We adjust in principle to everything and everybody. This attitude became quite clear to me once by the words of one of my compatriots who, apparently, knew how to express his feelings. Having just arrived in France, he founded one of these societies of adjustment in which German Jews asserted to each other that they were already Frenchmen. In his first speech he said: “We have been good Germans in Germany and therefore we shall be good Frenchmen in France.” The public applauded enthusiastically and nobody laughed; we were happy to have learnt how to prove our loyalty.

If patriotism were a matter of routine or practice, we should be the most patriotic people in the world. Let us go back to our Mr. Cohn; he certainly has beaten all records. He is that ideal immigrant who always, and in every country into which a terrible fate has driven him, promptly sees and loves the native mountains. But since patriotism is not yet believed to be a matter of practice, it is hard to convince people of the sincerity of our repeated transformations. This struggle makes our own society so intolerant; we demand full affirmation without our own group because we are not in the position to obtain it from the natives. The natives, confronted with such strange beings as we are, become suspicious; from their point of view, as a rule, only a loyalty to our old countries is understandable. That makes life very bitter for us. We might overcome this suspicion if we could explain that, being Jews, our patriotism in our original countries had rather a peculiar aspect. Though it was indeed sincere and deep-rooted. We wrote big volumes to prove it; paid an entire bureaucracy to explore its antiquity and to explain it statistically. We had scholars write philosophical dissertations on the predestined harmony between Jews and Frenchmen, Jews and Germans, Jews and Hungarians, Jews and … Our so frequently suspected loyalty of today has a long history. It is the history of a hundred and fifty years of assimilated Jewry who performed an unprecedented feat: though proving all the time their non-Jewishness, they succeeded in remaining Jews all the same.

The desperate confusion of these Ulysses-wanderers who, unlike their great prototype, don’t know who they are is easily explained by their perfect mania for refusing to keep their identity. This mania is much older than the last ten years which revealed the profound absurdity of our existence. We are like people with a fixed idea who can’t help trying continually to disguise an imaginary stigma. Thus we are enthusiastically fond of every new possibility which, being new, seems able to work miracles. We are fascinated by every new nationality in the same way as a woman of tidy size is delighted with every new dress which promises to give her the desired waistline. But she likes the new dress only as long as she believes in its miraculous qualities, and she discovers that it does not change her stature—or, for that matter, her status.

One may be surprised that the apparent uselessness of all our odd disguises has not yet been able to discourage us. If it is true that men seldom learn from history, it is also true that they may learn from personal experiences which, as in our case, are repeated time and again. But before you cast the first stone at us, remember that being a Jew does not give any legal status in the world. If we should start telling the truth that we are nothing but Jews, it would mean that we expose ourselves to the fate of human beings who, unprotected by any specific law or political convention, are nothing but human beings. I can hardly imagine an attitude more dangerous, since we actually live in a world in which human beings as such have ceased to exist for quite a while, since society has discovered discrimination as the great social weapon by which one may kill men without any bloodshed; since passports or birth certificates, and sometimes even income tax receipts, are no longer formal papers but matters of social distinction. It is true that most of us depend entirely upon social standards, we lose confidence in ourselves if society does not approve us; we are—and always were—ready to pay any price in order to be accepted by society. But it is equally true that the very few among us who have tried to get along without all these tricks and jokes of adjustment and assimilation have paid a much higher price than they could afford: they jeopardized the few chances even our laws are given in a topsy-turvy world.

The attitude of these few whom, following Bernard Lazare, one may call “conscious pariahs,” can as little be explained by recent events alone as the attitude of our Mr. Cohn who tried by every means to become an upstart. Both are sons of the nineteenth century which, not knowing legal or political outlaws, knew only too well social pariahs and their counterpart, social parvenus. Modern Jewish history, having started with court Jews and continuing with Jewish millionaires and philanthropists, is apt to forget about this other trend of Jewish tradition—the tradition of Heine, Rahel Varnhagen, Sholom Aleichemn, of Bernard Lazare, Franz Kafka or even Charlie Chaplin. It is the tradition of a minority of Jews who have not wanted to become upstarts, who preferred the status of “conscious paria.” All vaunted Jewish qualities—the “Jewish heart,” humanity, humor, disinterested intelligence—are pariah qualities. All Jewish shortcomings—tactlessness, political stupidity, inferiority complexes and money-grubbing—are characteristic of upstarts. There have always been Jews who did not think it worth while to change their humane attitude and their natural insight into reality for the narrowness of castle spirit or the essential unreality of financial transactions.

History has forced the status of outlaws upon both, upon pariahs and parvenus alike. The latter have not yet accepted the great wisdom of Balzac’s “On ne parvient pas deux fois”; thus they don’t understand the wild dreams of the former and feel humiliated in sharing their fate. Those few refugees who insist upon telling the truth, even to the point of “indecency,” get in exchange for their unpopularity one priceless advantage: history is no longer a closed book to them and politics is no longer the privilege of Gentiles. They know that the outlawing of the Jewish people in Europe has been followed closely by the outlawing of most European nations. Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples—if they keep their identity. For the first time Jewish history is not separate but tied up with that of all other nations. The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.

Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees,” Menorah Journal 31, no. 1 (January 1943): pp 69-77.

Trying to read this Nic, but gosh... I asked Perplexity to summarise for me...

Do you think it missed any key points?

## Summary of "What really happened between Donald and Elon" by Nicholas Gruen

Nicholas Gruen’s article, "What really happened between Donald and Elon," explores the high-profile public fallout between former U.S. President Donald Trump and billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, analyzing both the immediate drama and its broader implications[1].

**Key Points:**

- **The Trump-Musk Breakup:** Gruen recounts the recent, highly publicized feud between Trump and Musk, which erupted after Musk criticized the Trump administration’s signature legislation, the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," for its projected impact on the U.S. national debt. Musk’s call to "kill the bill" prompted a sharp response from Trump, who expressed disappointment and suggested their relationship was over[1][2][3].

- **Escalating Insults and Financial Fallout:** The spat quickly devolved into mutual insults on social media. Musk claimed credit for Trump's 2024 election victory and accused Trump of ingratitude, while Trump implied Musk’s opposition was self-serving, tied to the loss of electric vehicle tax incentives for Tesla. The public feud triggered significant financial consequences: Tesla’s market value dropped by $152 billion, and Trump’s cryptocurrency, TrumpCoin, lost over $100 million[3].

- **Policy and Power Struggles:** Gruen situates the Trump-Musk conflict within a broader context of elite influence over policy. He notes that Musk, as both a major political donor and a White House advisor, wielded unprecedented influence, but the partnership soured over legislative priorities—particularly those affecting Musk’s business interests and the national deficit[1][2][3].

- **Broader Implications:** The article reflects on the volatility of alliances between powerful business figures and political leaders. Gruen uses the episode to illustrate how elite interests can quickly shift, destabilizing markets and public policy. He also touches on the dangers of governance driven by elite consensus rather than expert advice, and the risks when major decisions are shaped by personal feuds rather than public interest[1].

- **Meta-Commentary:** Gruen’s writing style is characteristically wry and self-aware. He frames the Trump-Musk saga as an example of how complex systems—political, economic, and social—can be disrupted by the unpredictable dynamics of personality and power. He also critiques the "systems" or "complexity" lens often used to explain such events, suggesting that sometimes chaos is just chaos[1].

**Conclusion:**

Gruen’s article is not just a blow-by-blow account of the Trump-Musk breakup, but a meditation on the fragility of elite alliances and the unpredictable consequences of their collapse. He warns that when elites fall out, the ripple effects can be swift and severe, affecting everything from financial markets to the machinery of government[1][2][3].

[1] https://nicholasgruen.substack.com/p/what-really-happened-between-donald

[2] https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2025-06-05/trumps-breakup-with-musk-devolves-into-a-war-of-insults

[3] https://www.wired.com/story/musk-trump-breakup-tesla-stock-price/

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/02/us/politics/doge-wilson-center.html

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=myFFDZwfGFM

It's JORDAN Carroll, my apologies