What could possibly go wrong?

… from global finance to imaginary submarines … and other things that turned up this week

Amen

Martin Wolf on global finance

Martin Wolf was a major contributor to thinking about the GFC - and not just in hindsight. And here he is wondering how easily we could become unstuck again, particularly with a psycho in charge of the US (my word, not his).

The risks of funding states via casinos

Invest long, borrow short and leverage up as much as possible. That is the way to make money in finance. It is how banks have always made their living. But we also know very well that this story can end in panic-stricken runs for the exit and financial crises. That is what happened in the great financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-09. Since then, as the Bank for International Settlements explains in its latest Annual Economic Report, the financial system has changed a great deal. But this central characteristic has not.

Moreover, notes Hyun Song Shin, economic adviser to the BIS, "despite the fragmentation of the real economy, the monetary and financial system is now more tightly connected than ever". If this sounds like an accident waiting to happen, you are quite right. Central banks must be prepared to ride to the rescue.

The story the BIS tells is an intriguing one. Thus, the aftermath of the GFC did not make the system fundamentally different. It just changed who was involved. In the run-up to the crisis, the dominant form of lending was to the private sector, particularly in the form of mortgages. Afterwards, lending to the private sector levelled off, while credit to governments exploded. The pandemic accelerated that tendency...

That was not surprising: if people want to save and lend, someone else has to borrow and spend. That is macroeconomics 101. In addition to the change in direction came a change in intermediaries: in place of the big banks have come global portfolio managers.

As a result, cross-border bond holdings have increased enormously. What matters here are changes in gross, not net, holdings. The latter are relevant to long-term sustainability of macroeconomic patterns of saving and spending. The former are more relevant to financial stability, because they drive (and are driven by) changes in financial leverage, notably cross-border leverage. Moreover, notes Shin, "the largest increases in portfolio holdings have been between advanced economies, especially between the US and Europe". The emerging economies are relatively less involved in this lending.

How then does this new cross-border financial system work? It has two fundamental characteristics: the leading roles of foreign currency swaps and non-bank financial intermediaries.

The biggest part of this cross-border lending consists of the purchase of dollar bonds, particularly US Treasuries. The foreign institutions buying these bonds, such as pension funds, insurance companies and hedge funds, end up with a dollar asset and a domestic currency liability. Currency hedging is essential. The banking sector plays a key role, by enabling the market for foreign exchange swaps, which provide these hedges. Moreover, a forex swap is a "collateralised borrowing operation". Yet these do not appear on balance sheets.

According to the BIS, outstanding forex swaps (including forwards and currency swaps) reached $111tn at the end of 2024, with forex swaps and forwards accounting for some two-thirds of that amount. This is vastly more than cross-border bank claims ($40tn) and international bonds ($29tn)...

As the BIS notes, this highly non-transparent set of cross-border funding arrangements also affects the transmission of monetary policy. One of the propositions it makes is that the greater role of non-bank financial intermediaries, notably hedge funds "may have contributed to more correlated financial conditions across countries". Some of this is quite subtle. Given the large-scale foreign ownership of US bonds, for example, conditions in the owners' home markets can be transmitted to the US...

What are the risks in this new system of finance? As has been noted, banks are active in the market for forex swaps. They also provide much of the repo financing for hedge funds speculating actively in the bond market. Moreover, according to the BIS, over 70 per cent of the bilateral repo financing from banks is at zero haircut. As a result, lenders have very little control over the leverage of the hedge funds active in these markets...

What does all this imply? Well, we now have tightly integrated financial systems, especially among high-income countries, even as the countries are moving apart, politically and in terms of their trade relations. Moreover, much of the funding is in dollars on relatively short maturities. It is easy to imagine conditions in which funding dries up, perhaps in response to large movements in bond yields or some other shock. As happened in the GFC and the pandemic, the Federal Reserve would have to step in as lender of last resort, both directly and via swap lines to other central banks, notably those in Europe. We assume that the Fed would indeed come to the rescue. But can that be taken for granted, especially after Jay Powell is replaced next year?

The system the BIS elucidates has much of the fragility of traditional banking, but even less transparency. We have a vast number of unregulated businesses taking highly leveraged positions, funded on a short-term basis, to invest in long-term assets whose market values may vary substantially even if their capital values are ultimately safe. This system demands an active lender of last resort and a willingness to sustain deep international co-operation in a crisis. It should work. But will it?

Playing to our worst instincts

Alan Elrod in Liberal Currents.

Am I a citizen? Right now, the answer is pretty simple: yes. I am adopted, though I was born in North Carolina. I assume both of my birth parents were citizens, and know that my adoptive parents are citizens. But my adoption was closed, which means I have severely limited means of accessing information about my biological family or details about my birth. With the Supreme Court ruling against universal injunctions and the Trump administration's signal that they see it as a green light to pursue their agenda, including further attacks on citizenship rights, the answer to my question now seems somewhat less clear.

Domestic and international adoptees face different considerations, but both have reason to be concerned. For international adoptees, the law now provides for automatic citizenship. But that's only been the case since 2000, before which time adoptive parents were expected to complete the naturalization process. Unfortunately, many went unnaturalized. Some estimates place the number of adoptees without citizenship as high as 75,000.

For domestic adoptees, a key problem is the prevalence of closed adoption. Many closed adoptions entail a total forfeiture of parental rights by the biological parents as well as significant legal barriers to future contact and reunification. This includes sealing the adoptee's original birth certificate and issuing an amended birth certificate bearing the names of the adoptive parents. Today, adoptees in only fifteen states have an unconditional right of access to their original birth certificates...

Before now, birthright citizenship precluded the need for citizenship questions about domestic adoptees. If this fundamental constitutional principle is threatened, what happens to domestic adoptees who can neither provide definitive proof they were born to American citizens nor easily gain access to the people and documentation that could provide certainty?

What we ought to remember is that, under a regime where being able to provide irrefutable proof of legal status on demand is the basis for one's security, anyone can find themselves at the mercy of immigration enforcement. How many people can provide, right this second, all of the necessary paperwork to assert their citizenship with total ease and confidence?

The truth is daunting. As Jack Herrera recently wrote for New York Magazine:

If Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrests you for an immigration-related offense, and you tell the agency you are a citizen, it might not release you. Citizenship isn't something that you wear on your body. Maybe you pull an ID, a passport, or even a birth certificate, but agents frequently assume these are fake. In that case, you will be taken to a detention center run by a private prison company.

Now consider all of this with the added complication of not having access to your original birth records...

Blood, soil, and belonging

Belonging, what it means, who gets to belong, and how are questions at the heart of the concept of citizenship. These ideas are also inextricable from the practice of adoption...

Exclusion, along ideological and identitarian lines, is the MAGA ethos. It's evident in the attacks on LGBTQ people. It's clear in the way MAGA politicians regard the parental rights of liberal Americans as subordinate to those of the loudest and angriest right-wingers...

Contingency and the individual

The small-l liberal heart of liberal democracy is the freedom and dignity of the individual. Liberalism holds that our lives, our choices are our own, though modern liberalism also makes accommodations for the social forces that can buffet any person.

Adoptees and the children of undocumented immigrants highlight the deeply contingent nature of human life. They open a window into the chaos that will be unleashed if the Trump administration successfully continues its attempt to rollback citizenship rights...

What this administration is threatening to do, and what the Supreme Court has made a little more possible for them to do, is strip the soul out of the things that bind us together not only as Americans but as people in an uncertain world.

The one laptop per child scam

Billionaire jumps shark

This is an interesting Ross Douthat interview with Peter Thiel, who, I agree with Douthat, is the most consequential right-wing intellectual entrepreneur of his time. I listened to the first two thirds in one sitting and found it compelling, even if I didn’t agree with it all. The next day I came back to the last third and found it unhinged.

The categories it takes as the premise for the discussion - the antichrist and the apocalypse - are unpromising ways to think about our contemporary discontents it seems to me. Belonging to a very specific religious tradition isn’t a good start. But the thing is that Douthat is actually happy to discuss them in their own terms. Douthat is incredulous at Thiel’s idea that the antichrist is Greta Thunberg (or modern environmentalist activism). So am I.

Anyway, it turns out Thiel actually has nothing to say for himself when asked to elaborate or when he’s challenged on his apocalyptic ideas. They’re a kind of flourish, like Curtis Yarvin’s ‘Monarchy is the solution: What was the problem again?’ Like Elon’s brief adventure into politics (or was it administration?) by gesture. Like Eric Weinstein’s plans to travel faster than the speed of light.

Pondering all this, it seems a little like the cultural atmosphere that helped produce and then revelled in the ignition of World War One. After generations of peace (at home at least) some people got into high, apocalyptic dudgeon at how bloodless and decadent things had become. In the early 20th century the idea that we needed a good war became widespread. In the early(ish) 21st some powerful people decided that western civilisation was doomed if we didn’t make some wild gesture in the direction of change. And here we are with the Congress having authorised the expenditure of another $45 billion on masked agents dragging people off to torture camps.

Burke’s Conservatism: a road barely travelled

By Jeffery Tyler Syck in The American Conservative.

Peter Viereck valued rootedness and traditional institutions over the market, standing athwart fusionism, yelling stop.

It now seems hard to believe, but there was a time when Americans did not often use the term "conservative." The great Harvard political theorist Louis Hartz even went so far as to argue that in America there are no conservatives. All of this began to change in 1940 when the Atlantic Monthly asked Harvard student and future Pulitzer Prize winning poet Peter Viereck to write an article for them defending liberalism. Instead, he sent them a piece entitled: "But—I'm A Conservative!"

In the article, Viereck called for a humanistic conservatism in the tradition of Edmund Burke and John Adams. His defense of conservative philosophy proved a tremendous success and led to a renaissance of conservative scholarship in the United States. However, Viereck soon found himself at odds with the burgeoning conservative political movement. He did his best to stand against what he saw as fusionism's doctrinaire capitalism and nationalist saber rattling...

In his Atlantic essay, as well as a series of books on the history of conservative thought, Viereck argued that properly understood conservatism is not a firm list of political principles, but an attitude grounded in an appreciation of humanity's fallen nature. As he often liked to say, conservatism is the concept of original sin brought forward into our daily lives. If humans are fallible, it naturally follows that we are not to be fully trusted to answer any pressing philosophic questions...

As a product of this, conservatives should detest all ideologies—all visions that profess to a total explanation of how the world works and what the future of civilization should be. As Viereck once expressed it: "It is misleading that 'conservatism' contains the suffix 'ism.' It is not an ism; Adams, Burke, and Tocqueville detested all systems, all ideologies. It [conservatism] is a way of living, of balancing and harmonizing—not science but art."

First and foremost is a preference for what Vireck called "rootedness." By this, he meant those intermediary institutions—family, church, trade union, and so on—that tie us to a place and restrain our selfish passions. These institutions temper our individualistic inclinations, provide a firm restraint on the power of the state, and, perhaps most importantly, give people the space they need to truly flourish...

Second, Vireck's rooted skepticism demands pluralism. If we have no guaranteed access to the truth of things, it naturally follows that it would be terribly cruel to try and foist one vision of the world upon everyone else...

Though Viereck certainly thought such reminders must exist in the political world, he believed conservatives's true home to be in the humanities: art, history, literature, and the like. For it is in culture that conservatism can best chastise a civilization for its hubris...

As time passed, the renaissance of conservatism sparked by Vireck began to move in a new direction. In 1955, William F. Buckley founded National Review and started to cobble together a collection of anti-communist hawks, traditionalists, and free market libertarians to try and form a cohesive political movement. The result of Buckley's efforts culminated in fusionism—a political ideology that sought to use free market economics to sustain the American tradition...

Viereck thought this turn of events to be a tragic betrayal of conservatism's deepest insights. He argued that Buckley was taking a cultural attitude and wrongly transforming it into a half-populist political movement...

However, Viereck's biggest problem with fusionism was not its political methods or its nationalist overtones—it was National Review's unqualified commitment to free market economics. Viereck was no socialist, but he argued that Buckley and his acolytes went far beyond opposing socialism. Instead, they transformed capitalism into a political dogma, and forcefully opposed any measure that deviated even slightly from their ardent bourgeois economic values.

In clinging to a capitalist dogma, Viereck thought that the fusionists fundamentally misunderstood the nature of the free market. Buckley argued that support for a free market would encourage the survival of free social institutions such as the family and church. In short, capitalism would be a force for freedom and social cohesion. Viereck disagreed, instead pointing to countless historical examples that displayed the inevitable homogenizing forces of unrestrained free market capitalism. Far from enabling the rooted institution's conservatism so cherishes, capitalism when left to its own devices destroys each and every one...

Viereck argued that capitalism's opposition to rootedness was inherent to its ideological commitments. Capitalism preaches one simple truth: a society built around accumulation will prosper. To aim continuously for increased material prosperity leads to a focus on efficiency, on carefully removing all objects that slow commerce and human interaction. Rooted institutions that form the heart of a conservative society are simply not built for such utilitarian purposes—their greatness lay in their inefficiency...

Though a generally quarrelsome fellow, Viereck did not ceaselessly berate fusionists without offering an alternative. He argued on behalf of what he called a humanistic conservatism, one that emphasized infusing the literary world with a conservative disposition and building a strong mixed economy...

More paintings by Australia’s early(ish) 20th century female artists

Multiculturalism in leadership

Something Australia seems particularly bad at and which both the US and UK seem way ahead of us on. In the UK this is most conspicuous on the right! I used to think that this was because of the role of the Eton/Harrow - Oxford/Cambridge conveyor belt but Kemi Badenoch is a counterexample, though she had middle class professionals as parents.

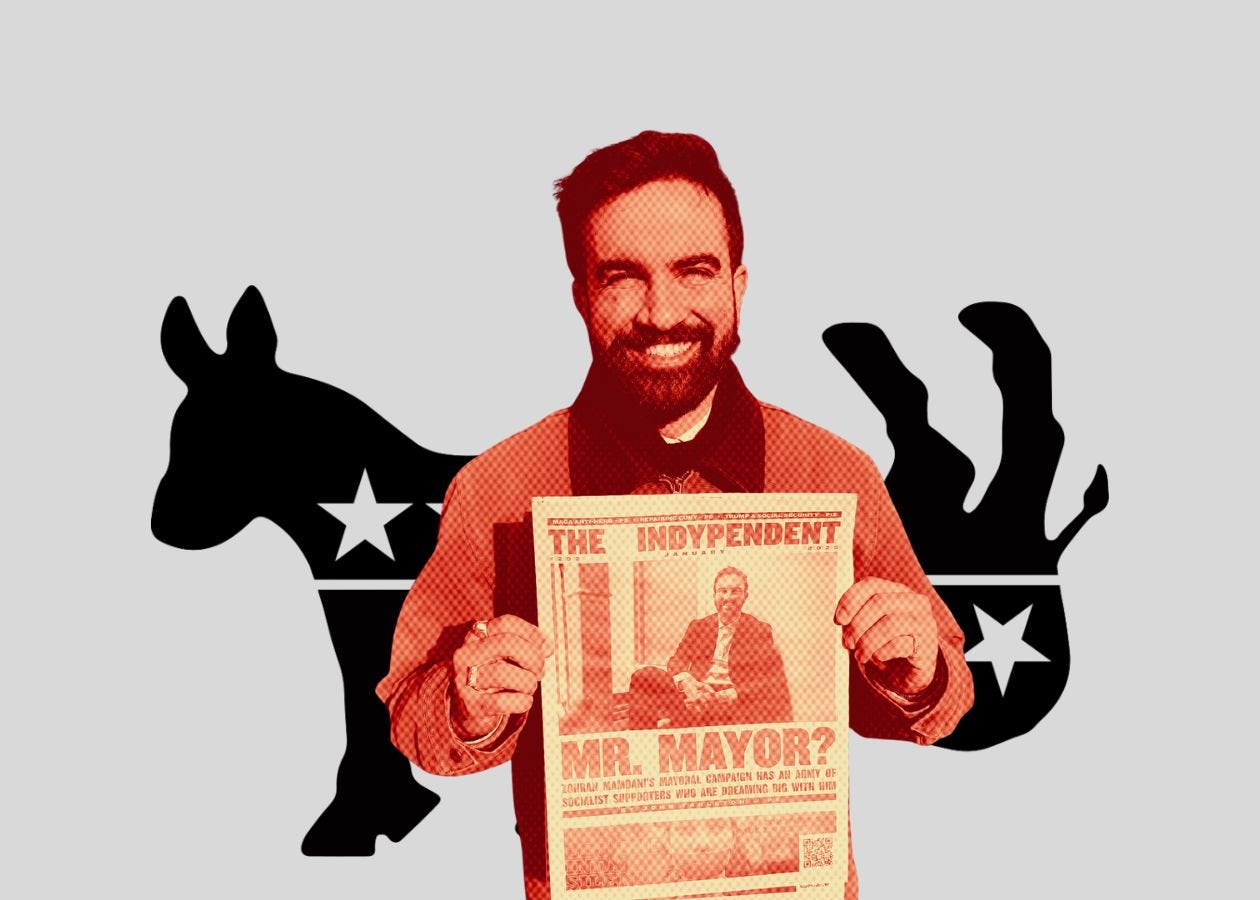

Gary Kasparov on Zohran Mamdani

When the normalcy candidate isn’t normal

A scandal-ridden alleged sex pest or socialism with Queens County characteristics: These were the inspiring choices New York City Democrats faced in today's primary. In a pick your poison race, it appears voters opted for the socialist. The Democratic establishment has only itself to blame. And if the party doesn't heed the lesson out of New York, this local contest could presage a disastrous 2028 presidential primary.

I won't waste much time on the winner, Zohran Mamdani. Suffice it to say, I'm not a fan of what he stands for. Not a fan of his freebie policy proposals, which smack of a grade school student council president promising ice cream and video games in the classroom. Not a fan of his radical left, anti-Zionist worldview, with which I'm well acquainted from my Soviet childhood...

Given all of that, how did someone like Mamdani win? If you step outside of Manhattan and the East River shoreline, you'll find that New York City is more purple than deep blue progressive. Many New York Democrats hew more moderate than their counterparts in other big cities. In a typical primary, a more sensible candidate would win.

Andrew Cuomo positioned himself as just that person—the normalcy candidate. The problem is that the disgraced former governor wasn't. Normalcy is not having over a dozen sexual harassment allegations to your name. It isn't massaging coronavirus death counts to burnish your reputation (although the architects of the Chernobyl coverup might be proud). Suddenly returning to politics less than half a decade after ignominiously resigning isn't normal. A do-nothing, ChatGPT-written campaign from someone who only moved to the city full-time last year reeks of entitlement. We should not be surprised that these things turn voters off.

An extremist victory is what happens when the normalcy candidate isn't actually normal.

There's precedent for my conclusion. Look no further than the 2024 presidential race. Joe Biden desperately wanted to be the normalcy candidate. Yet being the president while you have significant age-related impairments isn't normal. Kamala Harris, for all intents and purposes, became a stand-in for this abnormality. And voters chose Donald Trump.

Democrats had the experience of 2024 going into Tuesday's election and still did nothing. As with last year's presidential election, there was no coordination. No concerted effort by any power brokers to get on the phone with Cuomo and say "You can run—it's a free country—but we're not supporting you." The party somehow failed to find an alternative in the largest city in the country, which, as my friend Bill Kristol pointed out, is home to both House and Senate Democratic leaders. (Technically, the field was wider than Cuomo and Mamdani, but the other candidates were non-entities)...

It's easy to see a similar scenario playing out in three years as the Democrats gear up for another presidential campaign. The establishment will coalesce around a candidate with real baggage—perhaps someone too intimately involved with the coverup around Biden's health or Kamala Harris's failed run. Skeptical voters will then opt for a radical leftist...

Yet in choosing someone from the far-left fringe who's unpalatable to many in the broader electorate, Democratic primary voters will risk handing the Oval Office to JD Vance or some other unscrupulous Trump disciple. Similarly, Republican mayoral hopeful Curtis Sliwa—New York's resident Batman in a red beret, more costumed character than proper candidate—or Turkey-bribed Trump hostage Mayor Eric Adams could have at least a fighting chance against the radical socialist.

Never say never. Mamdani himself started at the bottom of the polls only to leapfrog a former governor in a matter of months while the Democratic establishment watched on. A political party that's as passive as this is just one sleepwalk away from never waking up again.

Don Moynihan on Zohran Mamdani

The suburb in which West Side Story was set

An abundance of hype

John Edwards has a fine review of the one book policy craze that is Abundance. Though you might think I’m dismissive - I’m not. I’m a big fan of Ezra Klein too. But, having suspected it all along, Edwards’s suggestion that it’s got about one chapter’s real policy content in it, I’ll probably skip reading the book.

The idea - that regulation and bureaucracy are slowly strangling some activities seems obviously true, even though, as Edwards stresses, we need to understand that regulation isn’t there for fun. It’s there to protect us from the harm markets do. We just have to make it work relatively efficiently. We’re a long way from doing so - and a long way from real bona fides on the subject. If you doubt that, have a look at the utterly bizarre way we regulate self-managed super funds. It’s easily fixed and would save SMSF retirees billions.

In their bestselling book Abundance American journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson argue that rich countries can be much richer. Their citizens can be healthier, their environment more salubrious, their working hours shorter, their homes cheaper. Their fruit and vegetables could be grown in vertical skyscraper farms, their protein manufactured in factories, their energy supplied cheaply from vast fields of wind turbines and solar arrays...

All this is attainable with contemporary technology, say Klein and Thompson — but only if we remove the barriers we have placed in our way.

Championed in recent speeches by treasurer Jim Chalmers and assistant treasurer Andrew Leigh, cited favourably by several Australian Financial Review columnists, Abundance is being presented as a manual for increased prosperity not only in America but in Australia as well. Its central message is that left-leaning legislators have created a framework of rules and regulations that impede the very programs they supported, notably environment protection, affordable housing and public infrastructure.

The "fascinating thing I found about Abundance," Chalmers told Sydney Morning Herald economics writer Shane Wright last week, "was basically, even if you have quite a progressive outlook, we've got to stop getting in our own way."

In the American case, those rules are mostly land-use restrictions. According to Klein and Thompson they impede more housing for the poor, the building of wind farms and solar panel arrays to replace fossil fuels, high-speed trains and other transport investments, and public infrastructure of all types...

Beyond the argument about the impact of land-use restrictions, however, Abundance begins to meander. The authors claim "a new theory of supply is emerging," but it is not at all clear what it might be...

While nodding to Abundance, Chalmers finds surer ground in instancing liberal economist Janet Yellen, the former Federal Reserve chair, and her view that "our side of politics needs to own supply-side economics." This is, after all, what Bob Hawke and Paul Keating were about in office, many decades ago.

Beyond the land-use story, one topic in Abundance elides into another... The genius of Klein and Thompson is that they have produced a very readable 272 pages in elaborating a thesis lesser writers might struggle to extend beyond a chapter.

Assistant treasurer Andrew Leigh seized on Abundance for a typically thoughtful and well-researched speech in early June. Citing the book as the inspiration for his talk, Leigh called for reform of Australian land-zoning restrictions to reduce housing costs and facilitate alternative energy supplies, policies to create new products from Australian inventions, and — close to his heart — better administration of universities.

Worthy as they are, these proposals don't reflect the central idea of Abundance that left-wing legislation now threatens left-wing objectives. Zoning restrictions in Australian cities may be cumbersome but they are not left-wing...

While evidently admiring the book, Leigh acknowledges that what is relevant to the US may not be relevant to Australia. It's true we share with California high home prices, falling house construction productivity and many zoning restrictions, but it has long been the case that state governments can override municipal restrictions, and often do...

I am convinced by Klein and Thompson that land-use restrictions in the United States do indeed make it harder to supply housing where people want to live, that wind farms and solar arrays are harder to build when landowners and local authorities object, and that California's failure to construct a useful bullet train after decades of trying is at least partly because state and federal laws empower objectors over proponents...

But I am also convinced — as Klein and Thompson are — that many of those same progressive laws and rulings achieved useful purposes. Legislation on car safety and lead-petrol pollution inspired by Ralph Nader, for example, or legislation to improve air and water quality or better protect forests and parklands...

All have since been turned to additional and unintended purposes. The political and policy problem is surely how to retain the good outcomes while minimising the bad outcomes. Klein and Thompson's solution is not a policy proposal but a set of questions... "It is a lens not a list," say Klein and Thompson, I think evasively.

Nice Brett Whiteley: but a bit steep!

What’s happened to Ukraine’s refugees?

Sarah O’Connor takes up the story for the FT. Fascinating bunch of factoids.

Wars are unpredictable. But one predictable consequence is that people run for their lives. As conflict flared again in the Middle East, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees warned last week that "once people are forced to flee, there's no quick way back".

Of course, you don't need to tell Ukrainians that. Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022 caused Europe's biggest displacement crisis in decades as millions fled, most of them women and children. Three years later, there are still more than 5mn Ukrainians living abroad. How are they doing? Did they find jobs? And will they ever go back?

The good news is that they have found jobs at much higher rates than is typical for refugees. Jean-Christophe Dumont, head of the international migration division at the OECD, told me that in many countries, their employment rate was "already maybe twice what you observe for other refugees"...

Overall, their incomes are rising after a tough few years. According to regular surveys commissioned by the Centre for Economic Strategy, a Ukrainian think-tank, the proportion of refugees who said they had to save or borrow to afford clothing rose from 7 per cent before the war to 28 per cent by November 2022. But by December 2024, that share had decreased back to 7 per cent.

Why have they done better in the jobs market than other refugees? For a start, the macroeconomic environment helped. Their displacement coincided with a time of unusually tight labour markets, especially in nearby countries like Poland and Czech Republic...

Most countries also allowed people fleeing Ukraine to apply for jobs straight away. The EU extended "temporary protection" status which meant Ukrainians didn't have to apply for individual asylum and could instantly access jobs, housing, schooling and social welfare.

In contrast, many countries ban individual asylum seekers from working while their applications are processed. The UK, for example, does not allow asylum seekers to work while their claims are considered (unless the process takes longer than 12 months) and gives them just £49.18 per week to live on. This sets people up to fail...

A survey across EU countries suggests that roughly two-thirds of Ukrainian refugees have tertiary education; more than 40 per cent of respondents had a master's degree or higher. Not only are they more educated than most other refugee groups, they are more educated than many host country populations too.

That said, many have had to take jobs for which they are overqualified. Whether due to language barriers or the inability to convert credentials, OECD data suggests that displaced Ukrainians in Europe are concentrated in accommodation, food service, administration and manufacturing roles.

Do they plan to return if the war ends? Ukraine must hope so. The permanent loss of so many highly-educated women would not be good news for the war-battered economy, while the loss of children would worsen its already poor demographic outlook.

But the relatively successful integration of Ukrainian refugees abroad could become a double-edged sword for Ukraine. The more people settle in, the less they say they want to go back. According to CES surveys, the share of refugees who say they definitely plan to return has dropped from 50 per cent in November 2022 to 20 per cent in December last year...

But it is a reminder that once war begins and people scatter, it is very hard to put all the pieces back together.

Heaviosity half-hour

Hugh White’s latest

The free Kindle sample from HARD NEW WORLD: Our Post-American Future by Hugh White. I recommend the whole thing. And I’m sure if we ask nicely enough those subs will turn up in a couple of decades.

A quarter of a century ago, the world was a pretty comfortable place for Australia. Our prosperity seemed assured by the apparently irresistible and irreversible forces of globalisation, driven by free trade and the free movement of investment, technology, ideas and people. That in turn was turbo-charging our Asian neighbours, especially China, offering us economic opportunities that were the envy of the world. Our security seemed assured by the apparently unchallengeable power of the United States, its manifest determination to uphold a global order in which aggression would be swiftly and surely punished, and its deep commitment to close allies, of which we like to think define us – our commitment to electoral democracy, the rule of law, freedom of speech, respect for human rights, tolerance of diversity – were now, we thought, becoming truly universal, as the tide of our victory bent towards freedom and justice. All this – what our political leaders have in mind when they talk about the "rules-based order" – was thanks to America. Australia was flourishing in a world made safe and easy for us by American power, influence and ideas.

Since then, a lot has gone wrong: 9/11 and the War on Terror, the global financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and the fractious struggle against global warming, to name just the most obvious. And now we seem to face something even more fundamental: a shift from a world which worked well for us to one that looks a lot harder to navigate. The basis of our prosperity is imperilled by the collapse of globalisation and the prospect that rival trade blocs will be built on its ruins. The foundation of our security is undermined by the eclipse of the US-led rules-based order. And the power of our values is undermined by the persistence of strong authoritarian governments in many powerful states, and the rise of populism and the erosion of democratic norms in places where these once seemed strongest, especially the United States. America made our world, it is passing away. Its place is being taken by a new and harder post-American world, and we are at a loss to know what to make of it and how to make our way in it. Our leaders are still in denial about all this. They still hope that the old rules-based order will somehow revive and survive so that things go back to the way they were in John Howard's day.

They grew complacent when the shock of Trump's first term gave way to the misleading normality of the Biden presidency, which somewhat restored confidence in democratic values and institutions. They were reassured too by Washington's robust response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine at the start of 2022, while its commitment to resisting China and upholding our nation's security seemed to be reaffirmed by AUKUS.

But now Trump is back, worse than ever. His first months back in office have been an astonishing spectacle. His absurdly inappropriate appointments to key jobs. His grotesque ideas on Gaza. His open contempt for US allies. His threats to Canada, Panama and Greenland. His assault on Ukraine. His frontal assault on the global trading system. The wrecking ball he has swung at the machinery of US government. His contempt for democracy and the rule of law. We must now recognise that Trump and the movement he inspires constitute a decisive shift in the way America works and in how this shapes the world. We must now see just how much we have already lost of the old world order, and how much more we are in danger of losing.

But the can't-look-away spectacle of Trump's second presidency should not mislead us. Everything that is happening is not just because of Trump. Deeper forces are also at work, and we must understand them if we are to understand this hard new world and how to make our way in it. That is what this essay is about. It focuses especially on the strategic elements of the current crisis. Ever since Imperial Japan destroyed Britain's position in Asia almost eighty-four years ago, our strategic and our place in the international system has been built upon our dependence on America, formalised seventy-four years ago in the ANZUS Treaty. Now that long era is ending, and we come face to face with our post-American future.

We are not alone. US allies in Europe and Asia have also relied on America, but they are now thinking seriously about their post-American futures. We have not even started. In February, as the full extent of Trump's abandonment of Europe over Ukraine was becoming clear, Anthony Albanese blithely confirmed that he believed our alliance with the United States was "rock solid." Peter Dutton was equally confident. Our alliance, we are told, stands above the ebb and flow of politics and policies in either country. Presidents may come and go, but nothing can shake the sure foundations of this great partnership.

America has strategic alliances with a lot of countries – over fifty, by one count. But the custodians of Australia's alliance with America – political leaders, officials, commentators and assorted schmooozers – believe that ours is something very special. They are convinced that between Australia and America there is a unique intimacy and mutual commitment that lifts our alliance under the ANZUS Treaty to a different level, above the cool and sometimes cynical calculus of national interests where ordinary alliances operate. Faced with the prospect of a second Trump presidency, Penny Wong said last year that the US–Australia relationship "is bigger than the events of the day" and is "shaped by enduring friendship and timeless values."

The claim that we are more than allies, we are "mates." Tony Abbott once went so far as to tell an audience in Washington that Australians did not really regard America as a foreign country. "We are more than allies, we're family," he said. Thus the proud boast that Australia has fought alongside America in every war it has fought since 1900. How else to explain America's generosity in letting us share its most prized military assets under AUKUS?

This is an illusion, and like many illusions it springs from anxiety. We are eager to claim that the alliance is built on foundations firmer than the shifting sands of national policies and interests precisely because we are unsure that policy and interests alone are enough to keep it alive. For all the sentimental talk of imprishable bonds, Australians have always been the most anxious of allies, and for good reason. No country in history has depended so much, and for so long, on an ally so far away from its and so driven to matters of such vital interest to the defence of their most vital interests.

That is why for 150 years, since the splendour of Pax Britannica first began to fray, "we have learned to depend on our allies?" has always been one of our central questions of our national life. And what we have learnt, again and again, is that all alliances, without exception, are transactional. That is what we discovered when Singapore fell in 1942, when the vaunted imperial ties of history, language, values and kinship were outweighed by the demands of Britain's own vital interests.

It was a lesson imprinted indelibly on the minds of the wartime and postwar generations, for whom the Fall of Singapore was a touchstone, reinforced by Britain's final withdrawal east of Suez after 1968 and America's uncertain support in regional crises of the early 1960s. But the lesson needs relearning today, as we emerge from the era we still call the "post–Cold War," when American power and resolve appeared to be limitless and unchallenged – rather like Britain's seemed at the height of its nineteenth-century imperial power. In a world with only one global power, an alliance with that power seemed to offer all we needed to make our way in the world. That era has now passed.

Recognising this and adapting to it is especially hard because the flipside of our deep comfort with the world America has made for us has always been a certain ambivalence about Australia's embrace of an alternative, Asian destiny. That has offered opportunities for politicians to exploit if they dare. John Howard was one who did. His mantra was that Australia does not have to choose between its history and its geography, by which he meant that we can bow to the logic of geography and comparative advantage by building our economy on Asian markets, but still look to America and Europe for our identity and our security. Australians would feel, he used to say, more "relaxed and comfortable" that way.

It seemed to work in the 1990s, when America's power seemed unchallengeable, and it was possible to think that Asia need be no more to us than a market for our exports. It made less sense by the time Howard left office in 2007, as I think he may have understood, because by then Asia was already more than just a market for us. But it didn't work for Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton in 2020 and 2021. They tried to make political hay by talking up Australians' growing anxiety about China's power and ambition by talking up the China threat and accusing their opponents of being agents of Beijing. Their David and Goliath act played well for a time, but not so much in the 2022 election, when Chinese Australian voters deserted the Coalition in numbers sufficient to cost them a couple of seats. For an electorally significant number of Australians today, Asia is not just a market: it is where they come from, and it means a lot to them. A lot more of us may be starting to understand, with or without Trump's help, the truth of Paul Keating's mantra that Australia must look for its security in Asia, not from Asia.

AMERICAN REVOLUTION

It is hard to forget what we saw unfold in the Oval Office on 28 February 2025, when Donald Trump and his vice president, J.D. Vance, confronted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in front of the TV cameras. It was certainly one of the most remarkable and disturbing diplomatic encounters ever filmed. Trump, back in the presidency for a second time, was someone both more in control and more out of control than ever.

There was something disconcertingly raw about that encounter, in the way Trump revealed himself with such relish. Narcissistic, cruel and avaricious. Irrepressible, unfettered and unlettered. Compulsively transgressive and heretical. Almost hormonally drawn to strength and arrogance in others, while being repelled by anything suggesting modesty, weakness or vulnerability. Of course, we have been seeing all this for nearly a decade, ever since Trump began his assault on the US political system in 2016. But the scene in the Oval Office that day struck deeply. Trump and his sidekick, two powerful men in very comfortable positions, facing no very tough decisions, took pleasure together in bullying and humiliating a third man, who, cornered like his country and in peril, faced one of the toughest decisions any person could face.

History will judge how far President Zelensky deserves his reputation as a hero and an inspiration, and its verdict will be complex. But there is no doubt that he, and through him his country, faced deep and grave desperation. As he confronted his tormentors that day, he carried a terrible burden. He had to find a way to end a war he could not win against an enemy he cannot escape. For three years he had shown courage and skill in leading his country to fight. Now he had to show even greater courage and skill in leading them to understand that there would be no victory, and to accept instead a perilous and probably temporary peace.

This is the personal drama of America's leaders, Trump and Vance – because, yes, there are two of them now – goaded, hectored and humiliated in the Oval Office that day. They did it for no better reason than to show how tough they think they are. And for them it was just a show. "This is going to be great television," was Trump's breathtakingly flippant, cruel and revealing remark at the end. To carry on like that in the presence of a man bearing Ukraine's burdens showed a lack of common humanity that is, in truth, sociopathic: "a mental health condition in which a person consistently shows no regard for right and wrong and ignores the rights and feelings of others."

Over time, with endless repetition, Trump's transgressions become familiar and cease to shock. But it is important if we are to understand the world we live in not to lose our sense of bewilderment and dismay that this person leads, inspires and controls – indeed, constitutes – a political movement which has seized the key instruments of national power in America and to which the US political system has, it seems, no effective response. He defies all that we thought we knew about that system, and indeed about the whole electoral democracies work around the world. Is there any precedent at any time for a person like Trump being elected and re-elected anywhere in any functioning democracy? Perhaps the closest precedent is Italy's Silvio Berlusconi, but he pales beside Trump. Berlusconi proved to be little more than an aspiring party animal.

Donald Trump is leading a revolution.

Trump defies so completely our ideas of what political leaders are and how they behave that even now it can be hard to judge his significance. It is a cliché that Trump's opponents made the mistake of taking him literally but not seriously, whereas the right way to take him was seriously but not literally. Now that advice seems out of date. We need to take him literally and seriously.

Taking Trump literally means recognising that what he offers Americans is nothing less than a revolution in the way the United States governs itself and the way it relates to the rest of the world. Taking him seriously means recognising that he seems to be in a position to achieve that revolution. Above all, he has a mandate from the US electorate. Last year Americans right across the country – people who knew what he'd done in his first term, knew how he'd acted when he lost in 2020 and knew what he said during the 2024 campaign about what he would do if he won again – voted for him in unprecedented numbers. It seems the more Americans know about Trump, the more they vote for him.

Apparently, it does not matter that the revolution he offers has no coherent objective and that it is conjured entirely from myths and prejudices, with its own personality cult only credo. That seems to be the revolution that most Americans want, or think they want, which tells us how deeply they reject the old American political order. That can only mean that deep forces are at work, economic and social trends which over decades have undermined so many Americans' confidence in and commitment to the old vision of America that for so long underpinned the policies of both parties and the constitutional order within which they are enacted.

And it is not just the voters. In 2025 other centres of power and influence have lined up with Trump in his second term in a way that was unthinkable in his first. By providing into his inauguration, the tech titans – men who stand at the apex of America's economy, and hence of its society – provided an endorsement of his revolutionary mandate almost as potent as the election result itself.

It seems still seems incredible that the foundational principles of American government, enshrined in a constitution which, we thought, is revered by Americans to a degree incomprehensible to citizens of other constitutional democracies, should prove so vulnerable to Trump's assault. Plainly, it shows that Trump has some extraordinary talents. But equally it shows the weakness of the political system and institutions that he has subjugated, starting with America's two great political parties.

What does it tell us about the Republican Party that a man like Trump, with no political experience, no political base, no political program and what seemed like insurmountable political liabilities could defy the party's leadership to seize its presidential nomination in 2016? What does it tell us that today, after he has lost, the party is even more abjectly subordinated to Trump's will and whims? Trump may be formidable, but the Republican Party didn't put up much of a fight. That may be in part because the pattern the Republican politics that created Trump has deep roots in the GOP, back to Barry Goldwater in the early 1960s, Nixon's Southern Strategy in the late '60s and early '70s, the rise of Reagan in the '70s and '80s, Rush Limbaugh and the rise of Newt Gingrich in the '90s, and the Tea Party movement that formed under and against Obama.

Trump's rise raises big questions about the Democrats too. How could the party of FDR, JFK and, yes, Bill Clinton have so little to offer America's voters that so many of them have turned in preference to Donald Trump and so many more could not be bothered to turn out to vote to defeat him? How to explain or excuse the debacle of the 2024 Democratic presidential campaign, when the party hierarchy inexplicably acquiesced in Biden's unconscionable bid for a second term? And where is the evidence now that the Democrats have any coherent ideas to offer US voters as an alternative to Trump's revolution, any plan to defend the vital pillars of the US constitutional order from him, or anyone who looks like they can win back the White House in 2028?

We do not know how resilient and robust the other institutions of American government will prove to be in resisting and containing Trump's revolution. But we can say that ever since the Trump era began in 2016, most of us have consistently overestimated the capacity of those institutions to contain him. The Congress, the courts, the bureaucracy, the states and the media have all been unable to stop his assault on the American state and its constitution. We can see where this could lead by looking ahead to the 2028 presidential election. Even if Trump does not defy the constitution to seek a third term, his movement will surely try to overturn the result unless his anointed successor is elected. They were prepared to do that in 2020 and 2024. How much better prepared and more determined will they be in 2028? What are the chances, then, that Trump's mysterious and momentous conquest of the American political system will be defeated at the ballot box? It is an extraordinary fate to befall what was one of the world's most robust and successful political systems the world has ever seen.

What does that mean for US foreign policy? Despite Trump's radically disruptive instincts, the key elements of US foreign and defence policy emerged from his first term largely unscathed. Credit for that belongs partly to Congressional Republicans, steeped in the bipartisan orthodoxies of US global leadership, who then still had the resolve to block many of his more radical proposals. Even more credit may belong to Trump's own officials, including many of his most senior subordinates. Steeped in the same orthodoxies, they circumvented or simply ignored presidential whims they disagreed with. That is why Joe Biden took over he found it easy to assume US business as usual. "America is back." It helped that this was what those allies desperately wanted to hear.

But this time is different. Back in 2016, Trump and his supporters hardly expected to win. They had no idea how to build an administration and only the vaguest idea of what they wanted it to do. Lacking a cadre of Trump true believers, they had little alternative but to fill key positions with traditional Republicans who had no real commitment to Trump and whose more orthodox views on foreign and defence policy were very different from his. This time the Trump team did expect to win, and they were fully prepared. They seem to have recruited a host of people who are dedicated to Donald Trump and his vision of America's place in the world.

This is most strikingly true of his most senior officials. We have seen a remarkable cavalcade of deplorably unsuitable people appointed and confirmed to important positions, including Pete Hegseth as secretary of defence, Tulsi Gabbard as intelligence chief, and Robert Kennedy as secretary of health. But consider also the more substantial members of the new Trump administration. Compare Trump's first vice president, Mike Pence, with J.D. Vance, or Marco Rubio with Trump's previous secretary of state, Mike Pompeo. Pence and Pompeo were traditional Republicans with an unquestioned commitment to the bipartisan orthodoxies of US global leadership.

Pence would never have spoken of Europe to the Europeans in the way Vance did at the Munich Security Conference in February this year, nor would never have ganged up with Trump to bully Zelensky. Pompeo would never have spoken of America as one great power among others in a multipolar global order in the way Rubio did at Davos (we will come back to this below). This time Trump is surrounded by people dedicated to his worldview and committed to reshaping America, and America's place in the world, to accord with it. It seems only prudent for other countries, including Australia, to expect that this will succeed, and start planning accordingly.

That scene in the Oval Office with Zelensky perfectly exemplified Trump's vision of America in the world. He rejects the whole idea of America as the global leader, upholding and enforcing international order and promoting American values for the good of the world as a whole. To Trump, America's sole purpose in the world is to protect America's direct interests in its own security and prosperity. And it is clear to him what that does and does not require. America's security does not require it to defend other countries far from America, because it is protected by two "big, beautiful oceans" that surround the Western Hemisphere, and what happens on the other side of those oceans does not really matter much to America's security. Thanks to those big, beautiful oceans, he said, the war in Ukraine is "far more important to Europe than it is to us." What really matters for American security is what happens on America's side of those oceans – in the Western Hemisphere. There America must be in complete control – hence Trump's extraordinary obsessions with Greenland, Panama and Canada.

Nor does he think that America's prosperity requires deep engagement with or commitment to other countries. He believes that the multilateral global trading system, designed and maintained by Washington since 1945 to promote free trade, is bad for America. He seems to see international trade as a source of weakness, not strength, so he wants America to be as self-sufficient as possible. And he thinks that when America does trade, it should do so through bilateral deals in which he can drive hard bargains to disproportionately benefit America at others' expense – or so he imagines.

This is a revolutionary vision. It directly repudiates the conception of America's place in the world that has been debated, refined and celebrated by generations of American politicians, officials, scholars and journalists, supported by generations of US voters, and sustained with huge commitments of treasure and blood. No wonder so many people in America and beyond – including in Canberra – find it so hard to accept that Trump really means to abandon the old vision, or that the American political system and the American people will let him abandon it.

Might they be right? It is perhaps too early to say how far Trump's revolution will go in transforming America's place in the global trading system. His "Liberation Day" tariff shock certainly suggested the scale of his ambitions. What he announced that day was the most radical attack on free trade since the early 1930s. But it also revealed the forces arrayed against him. They include internal contradictions within the policy itself, driven by conflicting ideas of what it is supposed to achieve. Some of Trump's most senior economic officials, including Stephen Mnuchin, chair of Trump's Council of Economic Advisers, and Scott Bessent, secretary to the Treasury, have spoken of using the tariff shock to compel countries, especially US allies, to join a Washington-led trade bloc to exclude and disadvantage China and accept new trade and monetary arrangements favourable to America. Those who do not comply will not just suffer high tariffs but lose American strategic protection as well. Others seem to hope that the threat of such a bloc, and the sky-high tariffs already imposed on China, will force Beijing to negotiate a comprehensive new trade deal favourable to America, and once that's done things will go back to something like normal. A third view is that the tariffs are simply intended to shield America's economy from imports, from China or anywhere else, and raise revenue: in which case there will be no tariff-cutting deals with China or anyone else. No one knows which of these outcomes Trump himself wants: he probably likes the idea that all three options appealing in different ways, but obviously they are mutually incompatible. That is a big problem.

But economic and commercial realities pose an even bigger problem for the trade policy side of Trump's revolution. The bond market soon made clear just how much of what he announced on Liberation Day. The dire consequences for key US industries and consumers forced further concessions, and may well force more. Trump's negotiators will find that their bargaining position with other countries is much weaker than they imagined, especially with US allies and with China, because America is simply not that important to most of them as a trade partner. It will become clear that making iPhones in America defies economic logic and common sense. It may well be that Trump will eventually abandon most of what he announced on Liberation Day, while no doubt claiming a brilliant success. The reality is that Trump's trade policies run directly counter to America's economic interests, and not even Trump can swim against that tide. Trump's trade policies will have lasting consequences and do a lot of damage, but the global trading order will not be permanently transformed by his revolution.

But the strategic dimension of Trump's revolution is different. His vision of America's place in the global strategic order swims with the tide of history, not against it, and it fits America's circumstances today better than the old orthodoxies of US global leadership. That is because the world has changed a lot since the 1990s, and especially since the end of the Cold War.

Donald Trump's critics often say that he is taking America back to the isolationism of the nineteenth century, which they assume is a bad thing. But something like the old isolationism makes sense for America today, and to see why, it helps to look at it in made sense for over a century from George Washington's day until the twentieth century. It dominated American foreign policy for so long because it worked in the light of America's enduring geography and the strategic circumstances of the times. America's geography, surrounded by those "big, beautiful oceans," makes it inherently very secure. It could only be threatened by a country strong enough to project major forces across the Atlantic or the Pacific.

In the nineteenth century only the great powers of Europe had even the remotest chance of acquiring such strength. To do that they would first have to dominate all the other European great powers, neutralising them so as to avoid being held back by European conflicts. But that couldn't happen as long as the European states preserved the balance of power between them. This they were all determined to do, because they all wanted to avoid being dominated. As long as the European balance of power was preserved without American intervention, no country would be strong enough to threaten America behind its ocean bastions.

That meant America had no need to shoulder the immense burdens and risks of intervening strategically in the world beyond its hemisphere. And that worked because, remarkably, the European balance of power did hold from the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815 to the catastrophe of 1914.

Of course America's wide oceans offered no protection from threats within the Western Hemisphere, so in 1823 America declared under the Monroe Doctrine that it would oppose any attempt by an outside power to build up a position in the Americas from which it could threaten the United States. The Monroe Doctrine and isolationism thus worked together to keep America secure at very little cost over the century during which it grew from a small colonial upstart to become the strongest country in the world.

So why did America abandon it? Isolationism stopped working for America because Europe's balance of power collapsed in the twentieth century, when rising powers upset the old strategic equilibrium. There followed a series of bitter contests – World War I, World War II and the Cold War – in which the strongest of these powers, first Germany and then the Soviet Union, seemed intent on dominating all of Europe, and all of Asia – the entire Eurasian supercontinent. For America, this posed a new and potent danger. As one of America's most influential strategists, Zbigniew Brzezinski, wrote, "A power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world's three most advanced and economically productive regions." Such a power would be strong enough to directly threaten America itself. Therefore, he wrote, "How America 'manages' Eurasia is critical." This new danger was what drove America in the twentieth century to abandon isolationism in favour of global strategic engagement. It was to stop any single power or coalition growing strong enough to threaten America itself by dominating Eurasia. It intervened in World War I, where Russia's collapse gave Germany a real chance of a victory that would have made it master not just of Europe but of Eurasia. It intervened again in late 1941, when the Axis powers seemed poised to dominate Asia, and Europe and everything between.

And it remained engaged after 1945, when the Soviet Union seemed poised to dominate Eurasia. This is what the Cold War was all about. The costs and risks were enormous, but the imperatives were clear because America's very survival seemed to be at stake. That is why it made sense for America to maintain massive military commitments around Eurasia. Isolationism was dead, and the world itself became unipolar. No one wanted to be called an isolationist.

And then the Soviet Union collapsed, and the threat that it might pose to America disappeared. At first, as in 1919, something of the old isolationism returned. It made a kind of sense to think that with the adversary gone and no new ones in sight, America could revert to old ways and once again withdraw to its own hemisphere. But that reflex did not prevail. Instead, Americans turned to a vision first articulated by Henry Luce in 1941 of a world in harmony and at peace under US leadership. He called it "the American Century." It was, and remains, a very appealing, almost utopian idea – at least when compared with the alternatives. And in the 1990s it seemed within reach.

What a decade that was. With the Soviet Union gone, America suddenly found itself in an unprecedented position of unchallengeable global pre-eminence in every dimension of national power – economic, technological, military, diplomatic and cultural. With communism defeated and, so it seemed, utterly discredited, American ideas and ideals had emerged victorious from the twentieth century's fierce ideological contests. Liberal democracy and market economics now appeared to be the only credible political ideology. A wave of democratisation and market-based economic reform transformed countries around the world. From Washington it looked as if the whole world was being remade in America's image under American leadership.

Not surprisingly, Americans of many stripes eagerly embraced the extraordinary global role that had so suddenly and unexpectedly fallen into their lap. To the idealists it fulfilled an abiding belief, dating back to the Mayflower, in America's destiny as a beacon and inspiration to the world. To hard-headed realists it offered a world in which America's security and prosperity were assured. For almost a century US policymakers had wrestled with the problem of preventing a rival power from dominating Eurasia and the world. Now they could dismiss that problem by dominating Eurasia and the world themselves. And of course it looked like a lot of fun. Policymakers in Washington were understandably intoxicated by the thought that they would, almost literally, rule the world, and seemed to everyone the ultimate vindication of American exceptionalism.

And best of all, it seemed that global leadership was going to be cheap and easy, because America's position would be essentially uncontested. The only countries that resisted the new unipolar order were relatively weak rogue states like Iraq, Iran and North Korea, and it seemed that they could be easily dealt with. The first Bush administration demonstrated in 1991, when Iraq's invasion of Kuwait was effortlessly crushed by America at the head of a vast and diverse global coalition.

Most importantly, it seemed that America would face no great-power rivals. All the world's more powerful states – the Europeans, Russia, China and Japan especially – seemed content to live in a US-led world. With the old ideological contests now resolved and golden economic opportunities open to all in a globalising world, there seemed no danger that America would ever face a major-power rival again. And there seemed no doubt that any rival that did emerge would be swiftly and easily deterred by America's overwhelming military superiority.

This meant that America could lead the post–Cold War world without carrying the exceptional burdens of the previous fifty years. Since 1941 it had made immense sacrifices to prevent the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon. Since the early 1950s that included the extraordinary and quite unprecedented risk of a nuclear war, which could devastate the homeland. Now it could harvest a peace dividend, bring its soldiers home, cease living with the threat of nuclear catastrophe and still lead the world. No wonder they embraced it all so eagerly.

Today, thirty-five years after the end of the Cold War, this utopian vision of the world and America's place in it still dominates the thinking of Washington's old – pre-Trumpian – foreign policy establishment. That includes Joe Biden and his team. None of them wants to be called an isolationist.

But the world has changed. It is no longer the world into which America stepped to prevent a rival power dominating the globe, as it did in World War II and in the Cold War. Nor is it the world in which, after the Cold War, America became the world's dominant power. Two big things have turned out differently from the way they seemed in the 1990s. First, America's global leadership faces much bigger challenges than Washington expected in the 1990s, when it seemed the US-led order would be essentially uncontested by any major power. That means America faces much higher costs and risks to maintain leadership. Second, the imperative for America to maintain that leadership is not as strong as it was in the twentieth century. The old fear that Eurasia could fall under the control of a single power is now much more remote, because something like the old balance of power has returned.

As a result of these two big changes, the foundational cost–benefit calculus that underpins America's broad strategic posture has switched. A version of isolationism now makes much more sense than the post–Cold War vision of US global primacy. That makes it virtually inevitable that the US-led global order will pass. It has nothing really to do with Donald Trump. It is because the world as it is, the costs of sustaining global leadership outweigh the benefits, and America no longer imperative to do so. As a policy it no longer adds up.

The primary driver of these changes is the truly fundamental shift in the global distribution of wealth and power over the past four decades, and especially since the turn of the century. This is embodied above all in the economic rise of the two most populous states, China and India. In the 1990s, America had by far the world's biggest economy, the deepest technology sector and an overwhelming preponderance of military power, and it was almost universally believed that this would remain true for decades to come – if not forever. Now China has overtaken America to become the biggest economy in the world on the measure that really matters strategically – purchasing power parity (PPP). The speed of the shift is remarkable. On International Monetary Fund estimates, in 2000 China's economy was one-third the size of America's in PPP terms, and India's was one-fifth. Today China's economy is 30 per cent bigger than America's, and India's is half the size of America's. China has at the same time become a world leader in many key technologies, and has built military forces, especially air and naval forces, that rival America's. India is moving more slowly and taking a different path to wealth and power than China, but it too will probably overtake America's GDP before long.

China's rise feels like an old and familiar story, but we in the West still do not understand its full significance. It decisively marks the end of the long era that began 250 years ago, when the Industrial Revolution completely transformed the global distribution of wealth, concentrating it in the economies of northern Europe and North America. Today, for the first time since around 1800, the biggest economy in the world is neither Britain's nor America's, but China's. That change is everything, because wealth is the deepest foundation of national power, and national power is the primary driver of international relations.

In the 1990s, US global leadership looked easy because America seemed so much more powerful than any potential rival. Now in East Asia it confronts a rival that is as strong or stronger than America on many dimensions of national power. This means that confronting and containing China to preserve US global leadership will cost a lot more than Washington mistook imagined in the 1990s, or have been willing to acknowledge since.

And at the same time as the costs of global leadership are going up, the imperatives to defend it are weakening, because today's world America need no longer fear the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon. That danger loomed in the twentieth century because the distribution of wealth and power made it possible that Germany or the Soviet Union could dominate the strongest continent.

That was especially true at the end of World War II and in the early decades of the Cold War, when American fears of a Eurasian hegemon were greatest. The Soviet Union then was by a huge margin the strongest country in Eurasia. Without America's active intervention it could easily have dominated Western Europe and Japan, both still devastated after the war. China after 1949 was a subordinate communist ally, while Southeast Asia and India were vulnerable as well.

That is why America shouldered the immense burden of containing the Soviet Union. But today the distribution of power across Eurasia is very different, thanks especially to the rise of China and India, and also to Europe's clear potential to coalesce as a fourth Eurasian great power. This new distribution of power means that no country, not even China, has the potential to dominate that Moscow once had. The other Eurasian great powers have the weight to balance China and frustrate a Chinese bid to dominate Eurasia.

Some people fear that the new Eurasian balance is threatened by the "no limits" partnership between China and Russia. It is argued that together these two powers could dominate Eurasia, threaten America and replace the US-led liberal-democratic global order with a new authoritarian hegemony that would threaten democracies everywhere. These fears are unfounded. They underestimate what drives Russia. It is determined to assert its own place as a great power, subordinate to no one – including China. That aligns it with China in wanting to replace US global primacy with a multipolar world order, but it will resist Chinese hegemony with all its power. And in doing that it can expect a lot of support – from Europe, India, perhaps also Japan.

The big point here is that in the twenty-first century, thanks to the extraordinary growth of emerging economies, wealth and power is already, and will increasingly be, distributed much more evenly between a number of great powers than it was in the twentieth century. That means America today is relatively weaker than it was, which makes it much harder to preserve the 1990s vision of US global dominance. But it also means America has much less reason than it once did to fear that any other country will achieve that kind of dominance, and hence be able to threaten the United States directly. In this crucial sense the twenty-first century is more like the nineteenth century, when the global balance of power worked to prevent global hegemony without active US intervention, than it is like the twentieth century, when America had to intervene in Eurasia against the most powerful states to maintain the balance of power and avoid hegemony. So what has changed is not just that the costs of US global leadership are higher than expected. The imperatives that drove it in the twentieth century are far weaker today.

This is the tide that, with or without Trump, is sweeping America away from the old vision of US leadership and back towards some version of isolationism. Indeed, as we will see, this tide drove much of what the Biden administration did, even as they swam against it. But Trump's swimming with this tide, which means his radical transformation of America's role is going to stick.

But that is not all. There is a second big factor overturning the cost–benefit calculus of global leadership for America. It is the return of nuclear weapons to centre stage in great-power politics. After the end of the Cold War, nuclear weapons suddenly seemed much less important than they had been in the decades of US–Soviet rivalry. Then the delicate balance of nuclear terror was the primary factor in global strategic affairs and the risk of nuclear war permeated every aspect of great-power politics. But with the demise of the Soviet Union, it appeared that nuclear war was no longer a serious possibility, and that nuclear weapons would play a much less significant part in world affairs. No one seriously feared that America might ever have to fight a nuclear war to defend its post–Cold War global position.

That is not how things have turned out. As America's rivalries with China and Russia have steadily escalated over the past ten or fifteen years, it has become increasingly clear that those rivalries could lead to nuclear war. We will explore later how this works and what it means in both Europe and Asia. The key point is that, as the Ukraine crisis has made abundantly clear, the costs to America of sustaining global leadership against the challenges of Russia and China include the real risk of nuclear attack on the United States. And that makes it even more certain that for America the costs of maintaining that leadership far outweigh the imperative to do so. That, too, explains why we have to take America's abandonment of global leadership so seriously.

What happens when America steps back from the role which has defined the global order for over three decades? What new order emerges when US leadership is withdrawn, and what role does America play in it? These are critical questions for everyone, including for Australia. It is no use asking Donald Trump, of course. But the answer is clear nonetheless. Instead of a unipolar order dominated by one overwhelmingly powerful leading country, we will see a global multipolar order in which a number of "great powers" play more or less equal roles in shaping world affairs through a complex combination of competition, accommodation and cooperation.

How will America under Trump see this kind of order? Interestingly, Trump's secretary of state, Marco Rubio, who seems by far the most thoughtful of the new administration's senior figures, has spoken about this quite explicitly. In his opening statement to his Senate confirmation hearings, Rubio brusquely dismissed the vision of a US-led liberal world order:

Out of the triumphalism of the end of long Cold War emerged a bipartisan consensus that we had reached "the end of history." That all the nations of Earth would become members of the democratic international community. That a foreign policy that served the national interest could now be replaced by one that served the "liberal world order." And that all mankind would become "one human family" and "citizens of the world." This wasn't just a fantasy; it was a dangerous delusion.

A few weeks later he explained that a multipolar order was taking its place.

It's not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power. That was not – that was an anomaly. It was a product of the end of the Cold War, but eventually you were going to reach back to a point where you had a multipolar world, with China and to some extent Russia ...

Of course Trump, not being an ideas person, has never spoken in these terms. Indeed, it may appear unlikely that a man so obsessed with American greatness would agree with Rubio that America should step back from global leadership to take its place as an equal partner with other great powers in a multipolar global order. But in fact this vision meshes perfectly with Trump's traditional instincts and prejudices, and with his own distinctive way of defining America's greatness. It fits with his respect for other strong countries and their leaders, including Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. It fits with his acceptance that they just want to exert influence over their neighbours just as he asserts America's sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere. It fits, too, with his lifelong rejection of America's alliances in Europe and Asia, which are a foundation of US global leadership. And it suits Trump's taste for ruthless dealing. For generations American leaders have tried to avoid the morally ambiguous compromises and accommodations of multipolar great-power politics, which they have seen as incompatible with the moral clarity of American exceptionalism. In different ways isolationism and unipolar leadership both offered refuge from such distasteful necessities. Trump has no such qualms. He likes the idea of cutting deals with powerful rivals in the ceaseless pursuit of advantage, and doesn't mind that smaller, weaker players get done over in the process. That is his idea of fun.