There's a theory of everything for that …

And lots of other things I've found for you this week

Eric Weinstein’s got a theory of everything for that

We have no shortage of men who have strong opinions about things they know very little about, but it’s not like this is news.

An overly timid engagement with the debates of our time will rob one of the ferocity of feeling that is necessary to move the world. 'If you do not feel it, you will not get it by hunting for it,' Goethe reminds us in Faust, 'You will never touch the hearts of others, if it does not emerge from your own' … The future belongs to those who, rather than hide behind an often hollow claim of accommodating all views, fight for something singular and new.

(Techbros) Alexander C. Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska, The Technological Republic.

Eric Weinstein so oozes self-regard that he's hard to listen to — for me anyway. Still, he has a highly fertile and penetrating mind. So he’s often worth listening to. Well before Trump he drew attention to the parallels between party political debate and kayfabe. If you don’t know what kayfabe is, look it up. It's kind of scandalous that most political scientists have no idea what it is.

Donald Trump was the Anglosphere’s first political leader to fully understand kayfabe, though I suspect Mussolini and Hitler and various African dictators like Idi Amin were no slouches.

But Weinstein’s fertile mind is also a febrile one. Before the recent election Eric was put out that the Trumpistas weren’t ringing him and other ‘dissidents’ who knew where the bodies were buried. After all, they were ringing ‘Bobby’.

Weinstein was half warning, half excited at the prospect that, while a Trump presidency might lead to ruin, he might just usher in a new golden age. He simply couldn’t vote for Kamala. His premise: Things are so bad that we kind of have to try something even if, maybe things will just burn to the ground.

This is a techbro meme. I recall listening to Marc Andreessen arguing that one can’t reform the education system, one has to start again. He may well be right. But in education where you can build your new system alongside the old one — at least if if you’ve got a spare billion lying around. But if you want to do it with a whole society — ask the folks Spain, Italy, Germany and Russia how that was turning out in 1939.

I reckon Eric and the techbros need to have a word with my mate Adam Smith who was wary of revolutionary talk warning “there’s a lot of ruination in a nation”. Eric was being overly dramatic. Self-absorbed. Self-aggrandising.

Despite describing himself as a liberal, in the video below, you’ll see he's an apocalyptic one, embracing one of Silicon Valley's favorite narratives — that of masculinity picking itself off the mat, dusting itself off, and embracing its world-expanding destiny. And with this masculine renaissance comes an acceptance of violence as simply the way things are. There's something to the basic idea that gender has played and will continue to play its role in things, but count me out of this hubris-laced techbro version.

It turns out that Weinstein’s ideas about kayfabe are part of a kind of theory of everything — a theory of what’s been going wrong since the early 1970s. Reality and life became unmoored and we’re all drawn into one cell in the quadrant illustrated above as we wait for the cataclysm — which, it seems, is now upon us.

Weinstein holds a Harvard PhD in mathematical physics and has already come up with his own theory of everything — Geometric Unity — which he sketched in 2013 and revisited in 2021. The academy was unimpressed, but then I agree with Weinstein, the academy is in a very bad way. YouTuber and physicist Sabine Hossenfelder thinks Weinstein’s theory of everything shares too much with string theory (which they both hate) to give her much interest in it, but wishes him well, along with other theorists of everything. (It’s a fairly crowded field.)

As you’ll see in the video, Weinstein's latest surrender to grandiosity involves transcending the speed of light (Srsly!). Then, all that masculine energy will be free to frolic among the galaxies while the earthlings blow themselves to bits. Boy will they have the jump on those techbros hunkering down in New Zealand for the duration.

See what you think.

Eric Weinstein jumps the quark

Incremental change that’s transformative

When it introduces new DNA into the system

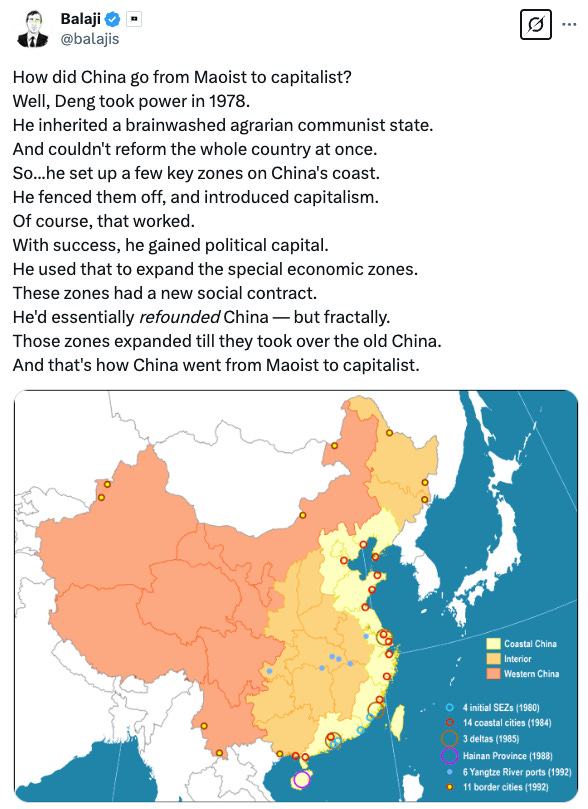

This tweet helps make a point I made a few weeks ago about acting with ‘imaginative vigour’. That is, one can act on a small scale, but not apologetically, not temporarily while one looks over one’s shoulder for social proof. The tweet below says that’s how China got rich. The initiatives Deng set off were often small scale. But they weren’t temporary, or built to be crowded out by the dominant system. They established within one system, pockets that operated according to a new logic — the one that was doing quite well elsewhere — market incentives.

That’s what we need in our democracy. Not market incentives — that’s a kind of category error we’ve made for too long (Governments generate shared, public goods, whereas markets create appropriable private goods.) We need to introduce ‘the other way to represent the people’. With our existing political monoculture built around representation by election (which has its place) we need to do what we did in the judicial branch in 1215 in Magna Carta. We need to introduce representation by sampling — as in random selection in juries.

All we need is the imaginative vigour to actually do it. Not to do it, kind of, do it temporarily on an advisory basis and then look around the room and see if the people with power like it and want more of it (hint: they won’t). We need to let new DNA loose in our system — the logic of representation by sampling via some ongoing institution like a standing citizen assembly or the Michigan Independent Citizens' Redistricting Commission. Because it’s a radical new idea, it can be introduced incrementally and if it’s any good, so long as we keep it alive and feed it, there’s a good chance it can grow into the existing system.

The alternative: using the system that brought you the oligarchs to fight off the oligarchs.

Don’t get me wrong. You have to start from somewhere and, within the existing system, this is pretty much the right place to start I guess.

Andrew Sullivan contra Anthony Fauci

It was a lab leak

Andrew Sullivan is one of the many conservative egg-heads coming into their own as putting their principles — not to mention basic commonsense ahead of tribal affiliations. As Danny Kaye said on TV in the 1960s to my parents’ hilarity “Egg-heads of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your yolks!” I didn’t get the joke.

In any event, when the lab-leak thing was going on, I deliberately didn’t have a position on it. Because it was arranging itself as a culture-war and you’d need lots of hard earned knowledge to have your own view, and because it made little difference to the question of what we should do right now, I ignored it, and assumed I’d find out in the fullness of time. As indeed I have. The insistence that COVID came from the Wuhan wet-markets was an establishment conspiracy to defer to Chinese sensitivities.

I was never a Covid nutter, on either side. I had my paranoid moments early on, but I never expected the government to get everything right. Anyone passingly aware of the history of plagues knows that failure is just par for the course. Misinformation? Always and everywhere, the record shows. But I did have faith in cutting-edge modern science and the expertise at the NIH. I knew NIAID's Tony Fauci from the AIDS days and remembered him very fondly. I trusted him.

I don't anymore. Over the last five years, we have slowly found out that, on Covid-19, we were all misled and misdirected a lot. And nowhere is this more evident than in the debate over where the virus came from. ...

The question had been famously answered by a scientific paper on the "Proximal Origin" of Covid published in March 2020 in Nature Medicine. It told us that the virus almost certainly came from nature: "we do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible." Anything else was dismissed as a meritless conspiracy story. When Trump started calling Covid-19 the "China virus," it just seemed to confirm the media's view that the lab leak was not just rightist bonkers, but racist.

But Trump wasn't wrong, and we know now that the "Proximal Origin" paper was an act of conscious scientific deception. ...

How do we know this? Five years later, all the major intelligence services in the West believe that a lab leak is indeed the likeliest reason for an epidemic that killed seven million people. The US Energy Department and FBI came to that conclusion in 2023, with the CIA finally agreeing this January. More striking is the news from Germany, where newspapers just reported that the German spy agency had believed Covid was a lab leak as far back as March 2020 — with 80-95 percent likelihood. ...

When American scientists took a first look at Covid-19, it immediately appeared man-made to them. As early as January 31, 2020, Kristian Andersen — one of the "Proximal Origin" authors — emailed Fauci that "some of the features [of Covid-19] (potentially) look engineered" and that the genome was "inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory." ...

Andersen's emails at the time are revealing. On February 2: "The main issue is that accidental escape is in fact highly likely ... the furin cleavage site is very hard to explain [without it]." Two days later: "The lab escape version of this is so friggin' likely to have happened because they were already doing this type of work."

Nonetheless, the paper Andersen produced focused "on trying to disprove any type of lab theory." And so it did: "Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus." ...

Were the scientists fearful of being deemed racist for believing in a lab leak? This was 2020, after all. The New York Times' Covid reporter summed up the elite view: "Someday we will stop talking about the lab leak theory and maybe even admit its racist roots." ...

A few weeks ago, we had a podcast on Spinoza, a pioneering scientist in a tribal religious age. His record shows that it is always possible for science to spurn political contamination — if scientists have integrity.

And without that integrity, science will lose public trust and simply become politics — which is why it now finds itself in such a crisis. When scientists refuse to release publicly-funded studies because they don't like the results, and when virologists consciously obscure the truth to protect their own asses and play global politics, we are right not to trust them.

But I want to trust them again. Science matters. We are in an epistemological crisis right now, where left and right have launched a postmodern assault on the search for objective truth. We need scientists right now more than ever to rescue liberal democracy from its decadent collapse. We need clear, reasoned, rigorous, replicated, open, and transparent science. We need reason, not politics.

When we needed that in a plague, it just wasn't there. People remember. And scientists have to grasp how hard it will be for some of us to forget.

The well known liberal bias of reality

Good post

That the left half of the American political spectrum has higher “human capital”—smarter, more educated, more competent personnel—than the right half has been a structural fact of American politics for my entire lifetime, if not for most of the twentieth century. That is not to say that there aren’t smart conservatives or brilliant intellectuals with right-wing politics, but that the American conservative moment has been defined by a long history of constructing an “alternative” ecosystem where ideological purity and partisan loyalty trumped evidence and expertise.

I used to try to explain this to conservative family members back home as I was explaining it to myself in my early 20s, when I moved abruptly from one of the bastions of far-right evangelical movement conservatism into working in the mainstream media in DC and New York. As a still barely ex-conservative, it was obvious that all of my media colleagues had liberal politics, and that in some cases those amounted to partisanship for the Democratic Party. It was also obvious that they were first of all committed to journalism and truth, including when it was awkward for Democrats or complicated their own worldview. They thought it was interesting when the facts didn’t line up with what they thought, or an issue didn’t break down neatly along partisan lines.

I tried to articulate it many times before I got it right: the conservative critique of the liberal media, so central to the political worldview I grew up with and partly responsible for my interest in media in the first place, was right about the basic fact that most of the media was liberal-leaning, even “biased” in some sense. But that right-wing obsession missed the forest for the trees. I would say things like, “Of course the media is liberal, but liberal things are not ideological in the same way conservative things are. Ideology is in the background of liberal institutions, but it is the only thing in conservative institutions.” In the era of 2000s neoliberalism, liberal spaces were much more heterodox and open to dialogue with conservative arguments than the right-wing world I was familiar with, which for all its intellectual trappings still primarily groomed one to recite dogmatic mantras, misdirect, own and discredit. I saw it firsthand in the way very young conservatives were whisked into prominent positions in right-wing media and politics simply because they had the right beliefs; conservative institutions had to take anyone who hadn’t defected from the project by age 22. When people accused me of abandoning my beliefs, I would say, “It’s not even about the beliefs! It’s about the style.” In the broadest sense, it seemed clear that one side in the political discourse cared about learning, accurate information, and rational debate—all of the things my conservative education had ostensibly trained me for—and one side didn’t.

I agree with all this, and yet would add that the alt-right have had more interesting and provocative things to say about the state we’re in — something I tried to suggest in this post.

The Professional-Managerial Class Has No Future

A strange article which makes an important point — the costliness of the managerial class replicating itself. Having made its point quite well, it turns out all it offers is advice to somehow monetise your skills in a way that builds appropriable capital. A focus on how build a better system for us all would have been of more interest to me.

In 2019, the Varsity Blues scandal erupted, revealing a web of petty corruption that was both darkly ironic and, for all its isolated nature, revealing of American parenthood. Wealthy parents, including celebrities and business leaders, had bribed college officials and falsified athletic credentials to get children into their colleges of choice. This scandal had multiple layers of absurdity. ...

The professional-managerial class (PMC) comprises highly educated professionals who work in fields like law, medicine, finance, and corporate management. Unlike traditional elites who can pass down family businesses, land, or powerful social networks, the PMC's only transferable asset is often their earning potential–which must be painstakingly re-earned by their children through similarly grueling educational and professional hurdles. ...

Like giant pandas, the PMC cannot reproduce without assistance. They cannot transfer assets, knowledge, and networks to their children; their path to reproducing their class status is mediated through an increasingly expensive and competitive educational gauntlet. ...

There is an absurdity to the results – parents queueing up for private kindergartens so their children may fingerpaint in prestigious company, high school kids earnestly talking up the fashionable nonprofit they founded with parental funding, eight year olds diligently practicing dressage so that they may study at the best institutions. But zoom out and the picture is a grim one. The professional-managerial class has no reliable means of reproducing itself without being taxed by these institutions, and however high the toll, they must pay.

One might argue that this system is a positive development – that wealth should not buy privilege and that a meritocracy ensures the most capable rise to the top. But the current arrangement does not reflect a functional meritocracy. A true meritocracy, like a wartime military or a rapidly expanding industry, seeks to identify and deploy talent quickly and efficiently. Our current system does the opposite – it draws out the process, layering on more obstacles and costs, not to identify talent but to extract wealth while certifying it. The gatekeeping institutions have no incentive to streamline the path to success; their interest lies in extending it, ensuring that both parents and children continue to pay into the system for as long as possible. Rather than elevate talented but less privileged students, it subjects them to the same protracted, expensive climb.

From another time

Paul Keating — at his best … and worst. I’m not a big fan of Keating, but wow is this a long time ago. On first viewing it, I sent it to a friend who’s a much bigger Keating fan than me, telling him we’d both agree how good he was here. But on second thoughts, I disagree with myself (as it were).

This performance falls foul of Gruen’s maxim for life.

If you want to fail, go into religion, not politics.

Political communication is not about being just, telling people what someone should be telling them. A priest maybe should do that. A friend should do that. If you’re a politician, perhaps if someone is dreadful enough you should choose the just response ahead of expediency. But ultimately while the guy Keating is speaking to is a pain, he doesn’t think he’s a racist, and indeed in important respects he may not be.

A really good politician — a Bob Hawke, a Tony Blair, a Bill Clinton — would speak to this person in a way that he might feel he was being sympathised with, even if the politician would explain that he didn’t agree with him. He might start with something like “I can see why you think that Bill, but I’ll tell you why we did what we did. I may not convince you, but I hope you end up thinking I’m doing the best I can.” etc.

What’s happening in the conversation is very much a class thing. The person on the phone is poorly educated — I’m thinking — and he’s got an opinion and ultimately Keating demands that he be better informed. (Keating himself left school early but was an effective autodidact.)

If we were in 19th century England that might be reasonable — he should know his place and defer to his betters. But (fortunately) we’re not in that world. We’re in a democratic world in which people who don’t have much knowledge about the world have strong opinions about what should be going down. Our politico-entertainment system more or less demands it. Oh and people who don’t know much includes people like you and me.

Jeff Sachs brings out his inner Fidel Castro

Last Tuesday night I went to bed with this playing and thought it would be over after an hour or so. It seems it runs for over 9 hours. That’s a lot of Jeff Sachs. This truly is the age of demagoguery. Still, it was pretty compelling stuff. I could tell you things I objected to about it. My position on the Ukraine war has, I think been fairly consistent since I started learning about it, namely that Sachs might be right that the Americans provoked Russia’s attack, but that still didn’t lead me to think we should not try to actively fight against the first invasion of a European country since WWII. In any event, I found it all pretty riveting.

I’ve cued the video to start where Sachs mentions how Americans always think they understand their adversary and always get it wrong. There are many and varied reasons for that, but one he suggests is game theory. I’ve often had a similar thought. Neoclassical economics makes all kinds of assumptions about people — assuming they’re purely, pristinely self-interested.

But it does so not because it’s true — it isn’t. As I explained here people invented the pronoun ‘we’. Looking at the way we deploy our money we spend around 60 percent of it on ourselves and our intimates, 40 percent of it on collective projects — through taxation and government expenditure and 1 percent on altruistic projects (which just goes to show we’re putting in 101 percent effort. Neoclassical economics presumes pure, pristine self-interested motives to get the maths to work out. And that’s how game theory models international negotiation. And why, in ignoring the need to talk and work out compromises, it could help us blow ourselves up.

I listened to about an hour and a half of it. But it lasts longer than a standard audio book! Anyway, for all I know the video just repeats 90 minutes a few times. What I can say is that it all has a certain fractal quality. You can dip in pretty much anywhere and off he goes …

Helen Lewis looks back in anger

I went back recently and read the 2017 Times piece that really got me put on to the shit list over gender. It is the mildest thing you'll ever read. The first paragraph is all about the genuine discrimination that transgender people face. Didn't help!

This is what I wish all the people complaining about the cruelty of the Republican agenda now could acknowledge: moderate compromise was on offer a decade ago and the left didn't want it. Instead they wanted to drum women like me out of public life.

That said, the backlash to this particular piece did teach me one thing: the people attacking it often *hated* the parallel with citizenship. They were also open borders people. That should have been a signal to the rest of the broader left that the pure self-ID ideology was a fringe position, no matter how loud its advocates were.

You can read the original article should you wish here:

John Ruskin: the painter

Bullshit busting: Yascha Mounk debunks the World Happiness Report

Yes a lot of stuff on wellbeing and happiness is bullshit. Particularly much of the policy adjacent stuff as I documented here.

Today is World Happiness Day. So, like every year on March 20th, you are likely to see a lot of headlines reporting on the publication of the annual World Happiness Report. "Finland is again ranked the happiest country in the world [while] the US falls to its lowest-ever position," a headline in the Associated Press ran this morning. Forbes even got philosophical, promising "5 Life Lessons From Finland, Once Again the World's Happiest Country." ...

Published by the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network and the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford University, the basic message of the report has remained the same since its launch in 2012. The happiest countries in the world are in Scandinavia. ...

I have to admit that I have been skeptical about this ranking ever since I first came across it. Because I have family in both Sweden and Denmark, I have spent a good amount of time in Scandinavia. And while Scandinavian countries have a lot of great things going for them, they never struck me as pictures of joy. ...

So, to honor World Happiness Day, I finally decided to follow my hunch, and look into the research on this topic more deeply. What I found was worse than I'd imagined. To put it politely, the World Happiness Report is beset with methodological problems. To put it bluntly, it is a sham.

News reports about the World Happiness Report usually give the impression that it is based on a major research effort. Noting that the report is "compiled annually by a consortium of groups including the United Nations and Gallup," for example, an article about last year's iteration in <a href="https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/20/us/world-happiness-report-finland-us.html">the New York Times</a> warned darkly that "the United States fell out of the Top 20" without a hint of skepticism about the reliability of such a finding. ...

In light of such confident pronouncements, you might be forgiven for thinking that the report carefully assesses how happy each country in the world is according to a sophisticated methodology. But upon closer examination, it turns out that the World Happiness Report is not based on any major research effort; it simply compiles answers to a single question asked to comparatively small samples of people in each country:

"Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to ten at the top. Suppose we say that the top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. If the top step is 10 and the bottom step is 0, on which step of the ladder do you feel you personally stand at the present time?"

The obvious problem with this question, commonly known as the Cantril Ladder, is that it doesn't really ask about happiness at all. ...

But perhaps the biggest problem with the World Happiness Report is that metrics of self-reported life satisfaction don't seem to correlate well with other kinds of things we clearly care about when we talk about happiness. ...

Two distinguished economists, Danny Blanchflower and Alex Bryson, set out in a recent paper to discover what would happen to the world happiness rankings if they looked at a broader range of indicators—and what they found is a totally different picture. ...

What Blanchflower and Bryson found is striking. Responses to the Cantril Ladder barely seem to correlate with expressions of either positive or negative affect. Denmark, for example, came top of their ranking on the Cantril Ladder. But Denmark did much worse on metrics of positive affect such as smiling or laughing (111th out of 164 countries). ...

As a result, the overall ranking constructed by Blanchflower and Bryson looks totally different to the more famous version published by the UN. Finland, for example, falls to 51st place. ...

Another surprise suggests that the story about happiness in the United States is not nearly as bleak as is usually suggested. For it turns out that happiness varies widely across America—and some parts of the country are seemingly the happiest in the world. ...

Over the last years, media outlets like the New York Times, universities like Oxford, and international institutions like the UN have devoted themselves to the fight against so-called "misinformation." But any institution which wishes to address that problem must start by looking into the mirror—and cease spreading "elite misinformation" like the World Happiness Report.

Bullshit all the way down

Book review by Dorothy Bishop, Emeritus Professor of Developmental Neuropsychology at Oxford. Quick let’s ignore the travesty it discloses. Let’s hold lots of meetings, but not actually do anything. Let’s all behave as if we have no will at all. It’s worked so far …

This is a rollicking good read... which works as a scholarly and accessible account of the so-called reproducibility crisis in biomedical research. As he explains in the Afterword, there is a personal backstory:

The journey of a starry-eyed young scientist entering the field of science, and continuing with the scientist working hard and hopefully contributing to the field over thirty years, but during all this time gradually realizing that the entire system suffers from major problems. And now that same scientist—not so young anymore, unfortunately—has written a book concluding that about 30 percent of the papers that come out every year are fake garbage and that 70 to 90 percent of the published scientific literature is not reproducible.

That is a startling statement, but Szabo speaks with authority... It is clear that he does not want to attack science: as he points out, it is the only game in town... But he is dismayed at how the scientific method has been degraded, and he is concerned that nobody in power is taking responsibility for cleaning it up.

What makes the book unlike any other on this topic is the detailed account of how we got into the current state, and what are the barriers to remedying the situation.

Szabo spends some time explaining how hypercompetition for research grants drives the behaviour of researchers... Szabo argues that the real crunch point for a biomedical scientist is success in obtaining external grants.

In the USA, this usually means NIH funding in the form of a R01 grant... The success rate is around 20%, and researchers typically need to submit numerous proposals in order to survive... So getting grants is extremely high-stakes.

It gets even more interesting when Szabo documents his experiences as a grant reviewer for NIH study sections... Such is the pressure for novelty and impact, that anyone who proposed to replicate a prior finding would be quickly triaged out of the competition...

Thus, the message researchers get from institutions is, if you want to keep your job, get a grant, and the message they get from funders is, if you want to get a grant, concentrate on making the research look exciting.

Szabo next moves on to discuss the way science is done in the lab. There are numerous factors that conspire to make findings irreproducible... When it comes to analysing the results, there is huge scope for adopting methods such as post-hoc outlier exclusion, p-hacking, and HARKing. All of these can be used to squeeze positive findings out of an unpromising dataset.

The next chapter takes a darker turn, moving to intentional fraud...

Szabo writes:

In my view, even this analogy is severely misleading. If we want to stay with nature analogies, my feeling is that we are dealing with a big scientific swamp, with various swamp creatures of different sizes and shapes living in it... The people who are supposed to manage the swamp, or perhaps drain it, are nowhere to be found.

One group of people who might be expected to manage the swamp are those who publish research papers, but Szabo does not find them equal to the task, instead talking of "a broken scientific publishing system"... Academic publishers are making efforts to screen new submissions for plagiarism and image manipulation, but there seems little appetite for cleaning up the existing body of scientific literature.

Szabo is impressed by the efforts of "data sleuths," who perform post-publication peer review and report problems on the PubPeer website, but he regards this as unsustainable... Organisations with some responsibility include universities, research institutes, publishers, editors and funders. Szabo's recommendations for change focus on funders, who have the power to deny funding to those who fail to take steps to ensure that their results are reliable.

This is a particularly difficult time to be conveying such a message. The only people who might be overjoyed to hear that a high proportion of published research is unreliable are politicians who are antagonistic to science and would like an excuse to defund it...

We urgently need therefore to look seriously at recommendations for changing how the system works at all levels - laboratory practice, funding, institutional integrity investigations, publishing, incentive structures - so that we can not only have confidence in scientific findings, but also defend science against attacks.

One point where I have a different approach concerns the emphasis on replications... The Registered Reports approach, where a study is evaluated by reviewers and accepted or rejected by a journal on the basis of introduction, methods and analysis plan, before any data are gathered, gets rid of the biases due to p-hacking, HARKing and publication bias, making it possible to interpret statistics sensibly.

Ezra has a new beard. And a new book

Review of Abundance: proposing supply-side liberalism

Noah Smith reviews Ezra and Derek’s new book on an important idea whose time came some time ago.

"It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice." — Deng Xiaoping

I've been waiting a long time for this book. Late in 2021, Ezra Klein wrote a New York Times op-ed titled "The Economic Mistake the Left Is Finally Confronting", in which he called for a new "supply-side progressivism". Four months later, Derek Thompson wrote an article in The Atlantic titled "A Simple Plan to Solve All of America's Problems", in which he called for an "abundance agenda". Many people quickly recognized that these were essentially the same idea. Klein and Thompson recognized it too, and teamed up to co-author a book... Three years later, Abundance has hit the stores. It's a good book, and you should read it.

The basic thesis of this book is that liberalism — or progressivism, or the left, etc. — has forgotten how to build the things that people want. Every progressive talks about "affordable housing", and yet blue cities and blue states build so little housing that it becomes unaffordable. Every progressive talks about the need to fight climate change, and yet environmental regulations have made it incredibly difficult to replace fossil fuels with green energy...

Why have people been zeroing in on the idea of abundance right now, when these problems were already getting severe two or three decades ago? I think there are four basic motivating forces that have all come together at the same time.

First, there's the housing shortage, and the YIMBY movement that has arisen to fight it... Second, there was the experience of Covid... Third, there's the challenge of climate change... And finally, there's the challenge of China...

Why does America not have enough housing, green energy, transportation, technological innovation, or health care? The typical progressive explanation is to blame lack of funding and the obstructionism of small-government conservatives. But... they marshal powerful evidence that an even bigger obstacle is progressives getting in their own way.

Even when the checks do get written, the things progressives want tend not to get built... California's high-speed rail, hyped so much over decades and given billions of dollars in funding, still doesn't exist. "Affordable" (i.e. subsidized) housing often costs half again as much to build as privately built housing...

Meanwhile, Texas, a red state known for its fiscal conservatism and its libertarian attitudes toward private business, has blown past blue states like California in terms of both green energy and affordable housing — a galling result for any progressive who can bear to look at the data.

Klein and Thompson identify three big categories of progressive policy — all of which were enacted in the early 1970s — that stymie progressive goals.

The first is procedural environmental laws... The second progressive own goal is contracting requirements for government projects... The third thing progressives get wrong is outsourcing...

Notice how all three of these progressive policies end up hobbling government more than they hobble the private sector... American progressivism has the reputation of supporting big government, but in practice it often just tries to use government as a pass-through entity to write checks to various "stakeholders", while preventing it from actually being able to do anything other than write checks.

Basically, Klein and Thompson call for a return to the older tradition of a progressive state that gets things done instead of just paying people out — more FDR and less Ralph Nader. But in doing so, they also articulate an alternative vision of political economy — a fundamentally different way of thinking about policy debates in America.

Currently, most American policy debates are framed in terms of ideology — small government versus big government. Instead, Klein and Thompson, like the YIMBY movement that inspired them, want to reframe debates in terms of results. Who cares if new housing is social housing or market-rate housing, as long as people have affordable places to live?...

This confusion [from critics] vividly reveals how accustomed [they are] to thinking of policy debates in terms of ideological procedure — big versus small government, industrial policy vs. deregulation, Chicago School versus antitrust, etc. She's sitting there puzzling over the color of Deng Xiaoping's cat.

Klein and Thompson's answer to [this] question is that it's the wrong question. If deregulation produces more housing, then deregulate. If building more social housing produces more housing, then build more social housing. Why not both? The point is not what legal philosophy you embrace in order to get more housing. The point is that you get the housing.

Progressivism should not be a ritual to be followed; it should be a tool to getting real stuff that makes life better for the middle class and the working class of America. That is the big insight at the core of Abundance, and of the movement behind it.

Abundance liberalism just doesn't care about [class status struggles]; zero-sum status struggles like that are simply not a goal. What matters to the abundance agenda is that regular people — the middle class, the working class, and the poor — have a less onerous life. If that means rich people have to give up some of their wealth, then fine, but if it means that rich people get richer, that's also fine.

Oh, and I enjoyed this footnote on this silly and poisonous (and ideological) review:

This article, by the way, is incredibly bad. It makes a blizzard of bad arguments — repeating the discredited Left-NIMBY claim that market-rate housing doesn’t reduce rents, blaming corporate developers for high rents, blaming private utilities for the lack of new electrical transmission, and so on. Glastris and Weisberg also willfully ignore most of what Klein and Thompson actually write — they offer state capacity as an alternative to the abundance agenda even though Klein and Thompson spend much of their book talking about the need for higher state capacity. Many of their arguments recapitulate Klein and Thompson’s arguments, but then somehow paint this as a criticism of Klein and Thompson.

The Academic Consequences of Affirmative Action Bans Combined with Diversity Targets

This paper examines the problem of a college affected by both a legal ban on affirmative action in admissions and pressure to raise enrollment of underrepresented minorities (URMs), as exemplified by UCLA, which adopted a holistic admissions process in 2006 in response to protests over low URM enrollment. The new process increased the URM share of admitted students by about 3 percentage points, but the primary effects of the changes were on admissions decisions within racial/ethnic groups. Within all groups, admission rates for applicants with high SAT scores and low income and parental education declined. Measured relative to UCLA’s pre-2006 revealed preferences, achieving the increase in URM admissions via holistic admissions was roughly 4-5 times as costly as doing so via a simple reallocation of slots between groups. Had UCLA complied with a stricter interpretation of the affirmative action ban, it would have been significantly more costly.

Richard Hanania hates liars more than criminals.

Some more from the roll of honour — those of right wing sensibilities with a sense of real fear for where the (American) right are taking us.

I once believed that the rise of the Tech Right was going to make conservatism smarter, orienting the Right toward a future of innovation and free-market dynamism. The movement wields great influence on the second Trump administration, most notably in the form of Elon Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency. The policy implications have been a mixed bag. But one thing we can say for certain is that having some of the most accomplished people in business come into the tent has somehow made the Right much dumber.

No one embodies this paradox better than the world’s richest man.

He who controls Twitter, now X, exercises a vast power over the culture, and the website is now the personal playground of Musk. As a prolific tweeter with some 219 million followers, Musk would have a powerful voice if he were just a regular user who could amplify certain accounts. As it is, he has also changed the tone and ideological tilt of the public square toward his preferred direction through measures like revenue sharing and the algorithmic derogation of links (meaning, if you share a link in an X post, far fewer people are likely to see it).

To say Musk is biased in his posts or that he shows a disregard for the truth doesn’t come close to capturing the constant stream of nonsense he blasts out to the world. This isn’t a matter of being biased or getting things wrong like CNN occasionally does. His feed is more in the neighbourhood of InfoWars, where Alex Jones will typically point to a document that actually exists to make wild extrapolations about what Democrats or “globalists” are up to. Musk is somehow more reckless: the things he regularly promotes lack even that kind of nexus to something based in reality.

He approvingly retweeted a tweet about a story pertaining to hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants being on the voter rolls in California, yet the link in the original post he himself shared was to a Snopes article debunking the claim. Musk has also falsely asserted that federal disaster-relief funds meant to help Americans were redirected towards housing illegal immigrants, even though the two are completely different programmes. When a pro-Russian account claimed that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky had a 4% approval rating in Ukraine — in contradiction to all reputable polling — he was fact-checked via a community note, which caused Musk to flip out and charge that the system was being gamed. These aren’t isolated instances. Things like this happen all the time.

It might be reasonable to suspect that someone as successful as he is must just be playing dumb online, while displaying a hidden command when it comes to policy. Yet even if you are sympathetic to his goal of reducing the size and scope of government — as I am — focusing on firing federal employees is just about the worst possible way to achieve that end. Fewer people working at the Food and Drug Administration, for example, doesn’t mean regulators getting off the backs of pharmaceutical companies trying to bring drugs to market. Instead, it makes drug-approval processes longer and more arduous. Or consider: Republicans have tended to oppose student-loan forgiveness, but now cuts at the Department of Education may lead to there not being enough workers to collect debt. Put another way: Muskian methods may be enacting a de facto version of former President Joe Biden’s policies.

Federal employees are a small part of the budget, and Musk’s assertions that huge savings might come from uncovering waste, fraud, and abuse is not taken seriously by anyone who has looked into the issue. He has spread false claims about dead people collecting Social Security that were based on a misunderstanding of a government database. All of this is even before getting to the question of how much of what he has been doing will hold up in court, with many of his moves already facing legal setbacks.

Musk is not alone. Other members of the tech oligarchy close to the administration have regularly spread false or misleading information, albeit on a much smaller scale. The venture capitalist Marc Andreessen went on the Joe Rogan podcast a few months ago and made claims that were somewhere between vastly exaggerated and completely false about the Biden administration “debanking” its enemies. During election season, a prominent VC investor asserted that there was massive voter fraud going on in California based solely on a text message someone sent him.

Great British humour

A wonderful study in the text and the sub-text.

Sieyes: why don’t we get taught more of this?

I knew bugger all about Sieyès, so found this podcast fascinating. I was particularly interested in the further fleshing out of Rousseau’s idea of collective will, which I’ve always been hostile to — via Schumpeter’s critique.

The argument that says the collective will is a fiction is all very well — and very powerful. It was after all a Frenchman — Condorcet — who got the ball rolling by proving that there is no mechanism for making collective decisions that has all the qualities we’d like of it. But I was intrigued by the idea that the people’s political representatives should not think of themselves as representing the particular sectoral interest of the district that voted for them, but should rather think of the public good or public interest. Not that I think it is necessarily better, but it’s different to the way we’ve built our democracies and it’s hard not to notice that they’re not doing very well, partly for reasons that are tangled up with these questions.

PwC spin-offs feast on taxpayer consultant addiction

PwC rises from the dead.

If the consultant class is meant to be in the dog house in Canberra, all we can say is it’s a profitable kennel.

Scyne Advisory, the private equity-backed consulting firm that was spun off from PwC at the height of the big four firms’ tax scandal woes in late 2023, has already clocked a tidy $12.1 million in new government work. This year.

Not a bad return for its new owner Allegro, and an outfit staffed by 1100-plus escapees from a firm that is banned from government work.

It’s especially impressive considering Scyne got its ethics and accountability sign-off from the Department of Finance only this week, after 15 months of essentially working under supervision as it had to prove its internal processes were sufficiently tough given its origin story.

The astonishing cruelty of Henry Higgins

One way to interpret the story of Pygmalion, it seems to me, is to see it as a tale in which the monster wins—because Henry Higgins is, quite obviously, a monster. The darkness of the story can be felt more strongly in the 1938 film version than in the play, largely (though not wholly) because of the magnificent performance of Wendy Hiller, in her first film role, as Eliza.

The story is, I guess, still widely known. When Henry Higgins, the great scientist of phonetics, meets a poor flower-seller named Eliza Doolittle in Covent Garden, he bets his new friend Colonel Pickering that in just a few months he can transform her speech so completely that even the snobbiest of snobs won’t be able to tell that she’s not one of them. Thanks to Eliza’s smarts and skills, Higgins wins that bet…

Back to the Monster: Henry Higgins’s behavior…is so bad that you find yourself casting around for a character to notice it. For much of the story the only plausible candidate for Conscience here is Henry Higgins’s mother. Colonel Pickering is certainly kinder to Eliza than Higgins…In the first scene, when an accusing crowd gathers around Eliza, he defends her, and when Higgins is trampling her he asks Higgins to consider the possibility that the girl has feelings. (Higgins considers it and decides that she doesn’t.) But after Eliza triumphs at an elegant ball…Pickering ignores Eliza about as completely as Higgins does. It is only Higgins’s mother who suggests…that they might have thanked Eliza for all the work she did to win Higgins’s bet for him. But Higgins does not thank her…There’s only one moment when he acknowledges her quickness and resourcefulness, and he does so out of her hearing…Pickering is perhaps a little too afraid of him to do so. But any criticism he receives is mild in comparison to what he deserves—at least until the final minutes.

Now, about Eliza herself. Wendy Hiller got an Oscar nomination for her performance…It’s difficult to overstress how great she is here, in an exceptionally challenging role. At the outset she’s doing broad comedy and doing it fabulously, but then she has to go through several stages of development.

First…she’s a poor lass who talks pure Cockney…But then, as Eliza undergoes her training, Hiller has to overlay a labored R.P. on Cockney vocabulary and diction—which, by the way, leads to the funniest moment in the whole movie, when…Freddy…asks her if she’s walking across the park: she replies with her newly-acquired cut-glass diction, “Walk? Not bloody likely! I’m going in a taxi.” Watch the whole scene and…you’ll be ready to give Wendy Hiller every Oscar statuette ever made.

Eventually Eliza matches her grammar to her new accent; and finally…in a moment of great emotional distress she loses her grip on her training and partly regresses to her native speech…Higgins loves to hear this, because he treats it as proof that her changes are superficial and that she will always remain the “guttersnipe” he likes to say she is…He wants at one and the same time to celebrate his great achievement and to dismiss it as little more than putting lipstick on a pig.

She has seen a world of elegance, beauty, and plenty, and…should she achieve her former ambition of working as a clerk in a flower shop, she won’t be able to forget everything she now knows…Near the end, Higgins’s casual demand that she fetch his slippers and become a kind of servant to him infuriates her, and Freddy’s obsessive puppy-like love for her brings no comfort…

After their big blow-up, in the final scene…she returns to his flat. But why? She doesn’t say. And with his back to the camera, Higgins once more…tells her to fetch his slippers. The End.

So does the monster win? Will Eliza fetch Henry’s slippers? Or will she walk out on him again as a hopeless case? Does he mean it jokingly, or…as a final refusal either to apologize or to treat her with courtesy?…It’s hard for me to see this as anything but Henry’s reassertion of his contempt for Eliza…

In any case, the filmmakers are leaving room for us to think that Henry is making light of his earlier fight with Eliza in order to create room for reconciliation. This is more than Shaw had done in the 1913 play, which ends with Eliza refusing to be his servant and stomping out of his house and maybe his life, after which Higgins dismissively insists that eventually she’ll do as she’s told. Curtain.

But even that was not sufficient to dissuade audiences who wanted to believe that Higgins and Eliza would eventually marry…Shippers gonna ship…

Shaw actually wrote the outline of a second play…in which Freddy and Eliza marry and start a flower shop…Colonel Pickering “has to ask her from time to time to be kinder to Higgins.” And you know what’s great? She doesn’t do it…

Heaviosity half hour

Machiavelli’s virtù revisited: Edward Skidelsky

I thought this was a very good essay. The author probably makes it a bit too easy for himself assuming that all modern discourse on virtue is ultimately instrumentalist, but then again, I’m not sure he’s far from the truth. We are in a world in which some of the brightest young idealists are trying to make the world a little safer for prawns. Maybe we should. But I’ll stubbornly interest myself in things that are closer to home for us humangoes.

Introduction

It is notorious that Machiavelli did not mean by virtù what we standardly mean by "virtue". But what did he mean by it? According to one influential interpretation, Machiavelli's virtù is simply the virtus of pagan antiquity, now openly distinguished from its Christian counterpart. "He is indeed rejecting Christian ethics", writes Isaiah Berlin (1997, p. 299), "but in favour of another system, another moral universe – the world of Pericles or of Scipio, or even of the Duke of Valentino." In a similar vein, J. G. A. Pocock (1975, p. 316) describes the outlook of Machiavelli and his circle as "a basically Aristotelian republicanism from which Machiavelli did not seem to his friends … to have greatly departed."

This view of Machiavelli – and it is still widespread – overlooks what is deepest and most troubling in his thought. Machiavelli's virtù is not the virtus of Cicero and Sallust, though it shares some of its surface features. Its essential attribute is not beauty or nobility but utility for the advancement and maintenance of state power. This was something new and seminal. Machiavelli himself did not grasp its full implications. It fell to later thinkers, including preeminently Hobbes, to spell them out systematically. Machiavelli's friends were very much mistaken if they saw him as a run-of-the-mill Aristotelian republican. His enemies had a better measure of the man.

Recent years have seen many attempts to reintroduce the concepts of virtue and character into public conversation. I am sceptical of such endeavours. Whatever its intentions, a "politics of virtue" must end up promoting the same kind of instrumentalism discernible in discernible in Machiavelli, for the modern state's interest is not and cannot be in virtue itself, but only its consequences. There is no point trying to breathe warmth into that "coldest of all cold monsters", as Nietzsche (1961, p. 75) called the state. Rather, we should seek out and create forms of community within which the life of virtue might still be led despite the politic organisation of our age.

Virtus in the republican tradition

To appreciate the originality of Machiavelli's conception of virtù, we must look very briefly at the prior history of term.

The Latin word virtus derives from vir, meaning "man" or "politically active man". Originally, it meant little more than "manliness", or "courage in war", war being the chief testing-ground of manliness in the Roman republic. Caesar, for instance, recounts how he put off punishing two Gallic commanders convicted of embezzlement in consideration of their outstanding virtus. Clearly for him the word was not a moral accolade (McDonnell, 2006, pp. 7–8). However, from the second century BC, by the process known to linguists as "semantic calque", virtus acquired many of the connotations of the Greek word arete, or "excellence in general" (McDonnell, 2006, pp. 72–141). This new usage was popularised above all by Cicero in his philosophical works. Elsewhere, however, virtus continued to be used in a narrowly martial sense, or in the somewhat wider but still not entirely general sense of political courage or "public spirit".

Christianity put a freeze on this semantic fluidity. For Jerome, Augustine and their medieval successors, virtus was simply the genus of which justice, prudence, courage and temperance were the four main species; its original civic meaning all but disappeared from view.¹ It was only in the fifteenth century, in the hands of humanists such as Bruni and Alberti, that virtus again became what it was in the age of Cicero: the specific virtue of strenuous devotion to the public weal, with overtones of manly energy and strength. "I am the great Aristotle", runs a not untypical inscription on the wall of the Palazzo Pubblico, Sienna, composed in 1414, "and I tell you in hexameters about the men whose virtus made Rome so great that her power reached to the sky" (Rubenstein, 1958, p. 193). Virtus in this humanist tradition was the quality by means of which rulers and citizens might, with fortune's favour, augment the power and honour of their native land. With it, great things were possible. Without it, all was lost.

This very brief history of the term virtus bears out a point well made by philosopher Sophie-Grace Chappell (2013, p. 182): thin concepts "are like the higher-numbered elements in the periodic table, artefacts of theory which do not occur naturally and which, even once isolated, are unstable under normal conditions". Philosophers tend to forget that their uniquely thin conception of "virtue" is a theoretical abstraction from that term's original "thick" meaning, which even now is liable to surface in non-philosophical contexts. Here, for instance, is Lionel Trilling (2008, pp. 161–162) on the aptness of referring to George Orwell as a "virtuous man":

There are few men who, in addition to being good, have the simplicity and sturdiness and activity which allow us to say of them that they are virtuous men, for somehow to say that a man "is good," or even to speak of a man who "is virtuous," is not the same thing as saying, "He is a virtuous man." By some quirk of the spirit of the language, the form of that sentence brings out the primitive meaning of the word "virtuous," which is not merely moral goodness, but also fortitude and strength in goodness.

One could put this observation to the test by commenting, in the course of casual conversation with non-philosophers, on the "virtue" of such-or-such a man or woman. I wager that the word will be taken to signify something more concrete than Aquinas' virtus or Aristotle's arete – if indeed it is taken as a straightforward approbative at all.

Machiavelli's innovation

All writers in the civic republican tradition could agree that virtus was a quality supremely useful to the civic body. "With this virtus your ancestors conquered all of Italy first, then razed Carthage, overthrew Numantia, brought the most powerful kings and the most warlike people under the sway of this empire", declared Cicero in his fourth Philippic (McDonnell, 2006, p. 3). "Virtus is the quality by means of which it is possible to maintain a stable and lasting political society" wrote the Renaissance humanist Patrizi (as cited in Skinner, 1998, p. 175). But virtus was not just useful. It had an intrinsic lustre or beauty, signified by the terms kalon in Greek and honestas in Latin. Cicero (On Duties III.11) was at pains to demonstrate that nothing is truly useful which is not also honourable, or at least not dishonourable. Properly understood, the utilis can never conflict with the honestus. His Renaissance followers tirelessly repeated the point, insisting again and again that no good can come to a prince who kills the innocent, breaks his faith, and so forth.

Machiavelli followed humanist convention in identifying virtù as that which promotes the power and glory of the state. He added, however, that virtù so understood has no necessary connection with honestas, for what is useful in matters of state may patently also be dishonest, cruel, miserly etc. In The Prince (2011, pp. 77–8), for instance, he praises the virtù of Roman emperor Septimius Severus in maintaining internal peace and order over his eighteen-year reign while freely acknowledging his cruelty and trickery. In the Discourses on Livy, his focus is on the character of the citizen body, not the ruler, yet his analysis follows the same general lines: virtù in citizens is whatever promotes civic greatness, whether or not it is intrinsically valuable. It can be instilled, for example (2003, pp. 50–61), by the calculating use of religious rituals – oaths, auspices and the like – though behaviour procured in this way is clearly not virtue in Aristotle's sense, which proceeds from a firm and unchanging love of "the fine".

Machiavelli is often praised for what is seen as his tough-minded jettisoning of ancestral pieties – a view encouraged by his own statement that it is "appropriate to go to the real truth of the matter, not to repeat other people's fantasies" (2011, p. 60). But mere tough-mindedness is hardly adequate to explain such a revolution in values. Are we really to suppose that men like Aristotle and Cicero were just too woolly-headed or soft-hearted to see that lies and crimes sometimes pay? No – the real explanation of Machiavelli's new morality lies in the emergence of a novel form of political organisation, the state, which he was one of the first to identify and analyse. Let me explain.

The polis, in Aristotle's classic account, is an association of friends, dedicated like all such associations to the achievement of a common good. The difference between the polis and other associations – dining or boating clubs, say – is simply one of scope; these latter aim at some specific, partial good, whereas the polis "takes regard to the whole of life" (Aristotle, 2002, p. 218). Political morality is an extension of personal morality, differing from it only in generality, not in kind. All this is a way of saying that the polis, for Aristotle, is not a thing distinct from the political activity of the citizen body, any more than friendship is a thing distinct from the mutual activity of friends. Conversely, political activity does not aim at the production of some entity external to itself. It belongs, in Aristotle's terminology, to the sphere of praxis, doing, not poesis, production. As Aquinas (always an astute interpreter of Aristotle's meaning, as well as an influential thinker in his own right) puts it in his commentary on the Politics (2007, p. 2):

Reason does some things by making them, by action that extends to external matter, and this belongs strictly to skills called mechanical (e.g., those of craftsmen, shipbuilders and the like). And reason does other things by action that remains in the one acting (e.g., deliberating, choosing, willing, and the like), and such things belong to moral science. There, it is evident that political science, which considers the direction of human beings, is included in the sciences about human action (i.e., moral sciences) and not in the sciences about making things (i.e., mechanical skills).

There can be, on this view of politics, no distinctly political morality, no raison d'état. Bad actions cannot in principle benefit the political association, since, as Aristotle puts it (1995, p. 106) "it is for the sake of actions valuable in themselves [kalos]… that political associations must be considered to exist". Private friendship provides an exact analogy. It would make no sense for a man to deceive his friend "for the sake of the friendship", though people do sometimes rationalise their conduct in this odd way. "Friendship" is nothing distinct from friendly action, so cannot be preserved by means of unfriendly action. Similarly, the polis is nothing distinct from the cooperative activity of its citizens, so cannot be preserved by deeds that undermine such activity.

This interpretation of ancient political life may seem wildly idealistic. The Athens of the thirty tyrants and the Rome of Pompey and Caesar were not exactly "associations of friends". Nonetheless, the ideal was close enough to reality to appear a plausible guide and aspiration. Greece in the classical period was divided into some 1500 city-states, most of them home to fewer than a thousand citizens. Athens, the largest by far, had between thirty and forty thousand citizens. It had "virtually no permanent officialdom whatever, administrative positions being distributed by sortation among councillors, while the diminutive police force was composed of Scythian slaves" (Anderson, 2013, p. 39). There were no palaces, no administrative headquarters, no garrisons – nothing that could be pointed to as a physical embodiment of state power. Societies of this type might be prey to all kinds of factionalism and corruption, but not that specific form of immorality which has as its goal the health of "the state", for there was no such entity. "Machiavellianism" could find no foothold here.

The modern conception of "the state" as an abstract entity distinct from any individual or group of individuals emerged only much later. When exactly is a matter of dispute. Some have traced it to medieval monarchy, with its symbolism of the king's second spiritual body, or "body politic" (Kantorowicz, 2016). Others have seen the first glimmerings of it among the professional diplomatists of Renaissance Italy, anxious to bind their often erratic political masters to courses of action advantageous to the interests of il stato. Machiavelli (himself of course a Florentine diplomat) frequently used the word stato in something close to its modern sense, thereby helping to establish it as the standard term for that form of political organisation.

Corresponding to this new conception of the state as something abstract and thing-like we find a new conception of statecraft as a productive activity, akin to sculpture or architecture. Again, Machiavelli sounds the characteristic note:

Without doubt, anyone wishing to establish a republic at present would find it much easier among mountain people, where there is no civil society, than among men who are used to living in cities, where civil society is corrupt; a sculptor will more easily extract a beautiful statue from a rough piece of marble than he can from one badly blocked out by others. (2003, p. 52)

Analysing their [Moses, Cyrus, Romulus and the like] lives and achievements, we notice that the only part luck played was in giving them an initial opportunity: they were granted the raw material and had the chance to mould it into whatever shape they wanted. (2011, p. 22)

As we said earlier on, if you haven't laid the foundations before becoming king, it takes very special qualities to do it afterwards, and even then it will be tough for the architect and risky for the building. (2011, p. 26)

This image of the statesman as a great artist, carving his state out of the unformed matter of humanity, has become such a cliché that we overlook its radical novelty. What it signifies, in effect, is that henceforth politics is to be regarded as a form of poesis, not praxis (see Singleton, 1953). Machiavelli's immoralism is a straightforward consequence of this shift of perspective, for to regard an activity as poesis is to refer it to standards which are not moral, which may conflict with and even displace moral standards. St. Petersburg is no less beautiful for having been built using conscripted serfs, nor is a glorious state any less glorious for having been brought into being using the methods of Cesare Borgia. Both may be deplored for other reasons, of course, but that doesn't take away from the specific excellence that is theirs. If politics is poesis, a potential gulf opens up between the politically useful and the honourable – a gulf that cannot arise so long as the polity is seen in Aristotelian terms, as an association of friends. Machiavellianism was not a product of unique tough-mindedness or unique wickedness. It was a logical implication of the new state system, and as such would have come into existence sooner or later even without Machiavelli.

Continuing the article:

Virtù domesticated

Machiavelli was not a consistent Machiavellian. Apart from his original and idiosyncratic use of virtù, his ethical vocabulary remained conventional. Thus he frequently extols as virtuoso conduct that is, by his own admission, cruel, avaricious, impious, dishonest and even wicked. It is hard to gage the tone of such remarks. Is this the anguish of a man forced to choose between the greatness of his native city and the salvation of his soul? Or the flippant irony of someone deploying – in inverted commas, as it were – a vocabulary that has become alien and empty to him? The debate continues to this day.

One thing is clear: Machiavelli's ambivalence was intolerable to his successors. Most responded with a vehement reassertion of classical and Christian morality, condemning Machiavelli as a satanic innovator. But the most forward-looking and influential of his successors sought harmony in the opposite direction, by bringing morality as a whole into line with civic imperatives. Hobbes, for instance, defined virtue as any habit of mind and action conducive to civil peace and defence:

By a precept of reason, peace is recognised to be good, from which it follows by the same reason that all the courses of action necessary for the preservation of peace must be good. So modesty, equity, trust, humanity and mercy, which we have demonstrated to be necessary for peace, must at the same time be good practices or habits of mind, that is to say, they must be virtues. (Quoted in Skinner, 1996, p. 322)

This looks on the surface like a vindication of traditional morality against Machiavellian cynicism. In truth, of course, Hobbes has avoided the appearance of cynicism only by being more consistently Machiavellian than Machiavelli himself. All the virtues, and not just virtù in Machiavelli's special sense, are now defined in terms of political utility; thus modesty, equity, humanity etc. regain their categorical force only by being emptied of their traditional content. To be sure, Hobbes had very different political ideals to Machiavelli, from which he derived a correspondingly different set of virtues (he did not think highly of physical courage, for instance). But the structure of argument is the same in both cases: first a state of affairs is identified as good; then those traits necessary for its production are defined as virtues. Here is the root of a position – "virtue consequentialism", we can call it – which remains powerful to this day, even among philosophers who might consider themselves free of such influences.²

The modern Machiavellians

Recent years have seen a number of attempts to put virtue on the political agenda, including the UK government's Character Innovation Fund and the Templeton Foundation's Character Development project. These initiatives have gained support from across the political spectrum; concern with character is no longer a preserve of conservatives. But common to all such projects, right- and left-wing, is a characteristically Machiavellian emphasis on the effects of virtuous action, as distinct from its intrinsic quality. Virtue is commended as a means to economic growth, social justice, class mobility, etc. The Aristotelian thought that it is only for the sake of actions fine and beautiful in themselves that political society exists at all has been entirely forgotten.

The new politics of virtue, unlike its ancient predecessor, is proudly "evidence-based". It draws support from a number of psychological studies claiming to show that success in later life is best predicted not by IQ but by a range of non-intellectual qualities, including optimism, self-control, and "grit". In 1940, 130 Harvard sophomores were asked to run for five minutes on a steeply slopping treadmill; success in this endurance test turned out to be "a surprisingly reliable predictor of psychological adjustment throughout adulthood" (Duckworth, 2016, pp. 46–7). In another famous study, four-year-olds who proved able to wait fifteen minutes for an extra marshmallow, rather than scoffing the one in front of them straight away, went on to achieve better test results throughout their school career (Tough, 2012, pp. 62–3). Experiments such as these have put the study of the virtues on a sound empirical footing, claim psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman. They have made possible "a science of human strengths that goes beyond armchair philosophy and political rhetoric" (2004, p. 1).

The work of Seligman and his colleagues is interesting enough in its own right, but it is emphatically not just a scientifically updated version of whatever Plato and Aristotle were up to. The so-called "virtues" of modern character psychology are simply dispositions to engage in certain measurable behaviours (staying on the treadmill, not scoffing the marshmallow). They lack the dimension of judgement, feeling and vision integral to the classical and Christian idea of virtue. Moreover, such virtues are strictly end-indifferent; they can just as properly be displayed in the pursuit of evil as in the pursuit of good. Hitler and Stalin were both paragons of grit, as Angela Duckworth (2016, p. 148) ruefully acknowledges. Finally, and most relevantly to my purposes, virtue as conceived by Seligman et al has only an external, causal relation to success in life, which is measured using the conventional indices of health, earnings and the like. What is lost is the thought that virtuous activity just is eudaimonia, or at any rate a central element in eudaimonia.³

To point this out is not, as I said, to denigrate modern character psychology, but simply to indicate its inconsistency with the tradition of the virtues as this has always been understood. Psychologists are not able, given the constraints of their method, to conceptualise virtue after the fashion of Plato and Augustine, as a deep-seated desire for the good. They are professionally bound to deal in value-free measurables. But we must not allow ourselves to forget that what the "marshmallow test" etc. test is not virtue in the classical sense but a scientifically curtailed surrogate for virtue. Peterson and Seligman (2004, pp. 9–10) are being disingenuous when they claim that their project "is grounded in a long philosophical tradition concerned with morality in terms of the virtues". They have fundamentally changed the subject.

Interestingly, it is precisely the self-proclaimed objectivity and value-neutrality of Seligman's approach that recommends it to many on the political left, who would otherwise be wary of the moralistic overtones of terms such as "virtue" and "character". If character is just a set of demonstrably useful life-skills, then to promote it universally is not hateful "paternalism" but an imperative of egalitarian politics. This is the burden of Richard Reeves' "A Question of Character" (Prospect, 2008). Reeves starts by defining "character" in a narrowly technical sense, as "a sense of personal agency or self-direction; an acceptance of personal responsibility; and effective regulation of one's own emotions, in particular the ability to resist temptation or at least defer gratification". Understood in this way, character is both an effect and a cause of economic position; low-income homes are more likely to turn out children with "bad characters", who in turn are more likely to end up in low-income jobs. Inequality of character perpetuates inequality of income. If we wish to reduce this latter, we must first tackle the former, if necessary by "compelling failing mothers and fathers to attend parenting classes".

Reeves' concern with character is clearly instrumental through and through. Economic equality is what ultimately matters to him; character education is a means to this end. A string of crassly mechanical metaphors serves to hammer home the point. "The 'stock of equipment' which makes up character is of vital importance in the construction of a successful life." "The family is the main 'character factory'." "Consistent parental love and discipline is the motor of the character production line." Machiavelli drew his metaphors from the atelier. Reeves draws his from the factory floor. The imagery has changed, but its implication is the same: virtue is nothing but a tool for the production of politically desirable states of affairs.

Of course, Reeves is just one writer among many. However, consideration of Machiavelli, Hobbes and others too numerous to mention suggests that we are dealing here not just with one person's opinion but with a tendency of thought endemic to modernity. The modern state's impulse is always to make use of the personal qualities of citizens for its own end, be this one of military aggrandizement, social justice, or whatever. Its gaze is steadfastly on the product, the "output". "Thus it buys for itself the lustre of your virtues and the glance of your proud eyes", wrote Nietzsche (1961, p. 76). Those of us who hold with Nietzsche that virtuous action is intrinsically valuable, perhaps supremely so, must be cautious of accepting the support of those whose use for it is purely instrumental, for in doing so we risk corrupting the very thing we most hope to preserve.

Notes

¹ Virtus was very occasionally used in its original meaning of manliness in secular medieval literature. See Huntington (2013).

² When Peter Geach, for instance, writes that "men need virtues as bees need stings" he reveals himself to be more a disciple of Machiavelli and Hobbes than of Aristotle and Aquinas. See Geach (1977), p. 17.

³ To be fair to them, Peterson and Seligman (2004, p. 18) acknowledge that "well-being is not a consequence of virtuous action but rather an inherent aspect of such action", but they immediately go on to misconstrue this thought in a psychologistic manner: "For example, when you do a favor for someone, your act does not cause you to be satisfied with yourself at some later point in time; being satisfied is an inherent aspect of being helpful."

Bibliography

Anderson, P. (2013). Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. London: Verso.

Aquinas, T. (2007). Commentary on Aristotle's Politics. (R. J. Regan, Trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Aristotle (1995). Politics. (E. Barker, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle (2002). Nicomachean Ethics. (S. Broadie & C. Rowe, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berlin, I. (1997). The Originality of Machiavelli. In I. Berlin (Ed.), The Proper Study of Mankind (pp. 269–325). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Chappell, T. (2013). There Are No Thin Concepts. In S. Kirchin (Ed.), Thick Concepts (pp. 182–196). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. London: Vermilion.

Geach, P. (1977). The Virtues. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huntington, J. (2013). The Quality of his Virtus Proved him a Perfect Man: Hereward 'The Wake' and the Representation of Lay Masculinity. In P. H. Cullum and K. J. Lewis (Eds.), Religious Men and Masculine Identity in the Middle Ages (pp. 77–93). Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press.

Kantorowicz, E. H. (2016). The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Machiavelli, N. (2003). Discourses on Livy. (J. C. Bondanella & P. Bondanella, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Machiavelli, N. (2011). The Prince. (Tim Park, Trans.). London: Penguin.

McDonnell, M. (2006). Roman Manliness: Virtus and the Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1961). Thus Spake Zarathustra. (R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). London: Penguin.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pocock, J. G. A. (1975). The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.