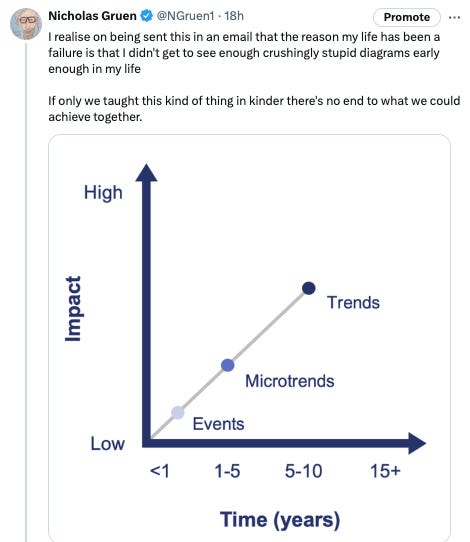

What comes after flipping the switch to crazy?

And other things I found on the net this week

Sunday mornings!

Welcome to my newsletter, one day late and on time. It’s one day late because I’ve had a heavy workload full week. And it led me to realise that a better time for sending out this newsletter is Sunday morning, because it will give me more time to get it ready on Saturday which I take more easily from the perspective of earning my living! If you’re a regular reader I hope Sunday morning at 10.15 am is as good a day to check out the newsletter as Saturday 10.15 am.

If it is a worse day for you, please email our complaints division (and best of luck finding the email address). And just remember that it’s entirely possible that the world is beginning to fall apart, so, for the duration, the new delivery time will be a fairly minor sacrifice.

Tim Walz!

I wrote what’s below early in the week before Tim Walz had been picked, but I was hoping he would be.

The origin of the current craze for the term ‘weird’ seems to be from Tim Walz’s appearance on Morning Joe — at least that’s Ezra Klein’s view. Now, Tim Walz is a smart guy, so I guess he’s thought about the word, but the thing about Walz is that he’s much less into robotic sound bites than most professional politicians. He’s less optimised, more vernacular than most politicians. In this, he reminds me of politicians of three decades ago whose rhetoric was, of course, NOT naïvely unconsidered, but it also strove not to be too rhetorical — to visibly come from the lifeworld, rather than the autocue.

So for me anyway, the word is an eruption from the life-world into the system world. And that brings on a shock of recognition. Walz’s comment about trying to imagine Donald Trump getting home from work and playing frisbee in the park and giving his dog a rub is the same kind of thing. Most politicians at least play a character who would do that. But not Donald. And Walz’s comment about Donald never laughing except at someone else — also cuts through.

They all cut through because Donald Trump is a psychopath and the cues for this are subtle but kind of obvious once one gloms onto them. Here’s an article where the magician Penn (from Penn and Teller) says similar things. He’s just talking about Trump, not beating up what he’s saying into a political message (though it’s obvious that there’s a political message in there.) And he reports that though he got on well with Trump and quite enjoyed his time doing so, Trump was the only person he’d ever met with no sense of shame.

These things are subtle, and, if they’re right provide profound insights into his nature — and his weirdness. The transcript of Klein’s interview with Walz is here.

In response to Donald’s comments on Kamala turning black

What comes after flipping the switch to crazy?

I enjoyed reading this FT essay “The reset: how Britain can restore its global reputation”. But I have two quibbles or points to make. The most substantial one is this. Meeting one’s international obligations (for instance on climate change) is not a one way street. One meets them partly to have a place to stand in demanding others do the same. The way we litigate political issues each side of the ideological aisle plays its symmetrical role in the culture war. So the right howl about how other countries aren’t meeting their obligations — usually irrespective of whether they are or not. The left is then the good cop saying that we have to meet our international obligations — otherwise why should others?

This often comes with the imputation that low income countries are really the good guys. Well no they’re not — they’re just like us and we have to do stuff together with everyone going on the front foot against free riders. But doesn’t that just boil down to no-one doing anything? Not if countries commit to ‘conditional generosity’. Anything more reductive than that is a step away from the narrow path to success. That thought falls out of the picture too often — as here.

Second — well I’ll leave that to when we get to the point in the article.

After a decade of prime ministers railing against international rules and judges, it seems that Britain now wishes to re-engage. But what will this mean in practice? A change of tone is the easy part, and some actions — rejoining international bodies or modifying aspects of treaties with the European Union — are straightforward. Yet what is needed is something much more fundamental. …

In my own world of international law, there was growing incredulity at the weak or marginal arguments put to judges in various cases at the ICJ. Don’t give an opinion on Israel’s occupation of Palestine, Britain told the judges earlier this year. Don’t say anything about the responsibility for historic emissions of greenhouse gases, it argued in a case on climate change. Don’t say there is a right to strike under international law, it submitted in a third case, on the work of the International Labour Organization.

Such arguments are not the stuff of front-page news — but they send signals picked up by other countries, reinforcing the sense that Britain has become semi-detached from the rules-based system it helped to create. A country that condemns Russia for targeting energy infrastructure in Ukraine but passes in silence when Israel does the same in Gaza is unlikely to win many hearts and minds internationally.

Over two decades, as I have travelled the world, the regret, surprise and anger has been palpable. On its international engagements, Britain is often seen as hubristic, navel-gazing and unreliable, a country stuck in the past that is unable to confront new realities, prone to a double standard that treats international rules as being for others, not itself. “What’s happening to Britain?” is a question I am often asked. …

I’d like to see Britain double down on its commitment to human rights and humanitarian law, holding its own allies to account where they fall short. A reset means speaking up for the global rules and condemning violations, wherever they occur, and taking the lead in supporting new initiatives, such as the proposed convention on crimes against humanity.

I’d like Britain to resume real leadership on climate change, of the kind initiated by Margaret Thatcher’s speech at the Second World Climate Conference, in November 1990, which paved the way for the global conventions. That means meeting our treaty obligations, reckoning with our past emissions, and revoking the North Sea oil and gas licences authorised by Rishi Sunak’s government. It means taking the lead on filling the gaps where the rules are inadequate, in terms of targets and timetables and domestic actions. It means supporting new ideas, including a new crime of ecocide. [I find it amazing that fighting backsliding by other countries doesn’t figure in this list. NG]

I’d like to see Britain make good on its commitment to the rules prohibiting military force except by way of self-defence or where genuinely authorised by the UN Security Council. That means holding others to account for the crime of aggression, by supporting the creation of a special tribunal for the crime of aggression in Ukraine, as is being negotiated under the auspices of the Council of Europe, that allows Putin to be held to account. …

[L]ast week, sweeping aside Britain’s lonely objections to its exercise of jurisdiction, in a case in which I acted for Palestine, the ICJ declared that the Palestinian people have a “right to an independent and sovereign state”, that “Israel’s continued presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory is unlawful” and must be ended “as rapidly as possible”, and that all countries, including Britain, are under an obligation “not to render aid or assistance in maintaining” the unlawful situation that persists.

The implications for Starmer’s government are clear: cease any military or other support that contributes to the illegal occupation, and recognise the State of Palestine, as Ireland and Spain recently have. Wobble on such matters and you forgo your ability to proclaim your re-engagement with international law.

Finally, I’d like to see the Labour manifesto commitment on soft power be followed through. Language, culture and arts — like respect for the rule of law and judges — are a central element of Britain’s reputation abroad. This means more funds for the BBC World Service — which is second to none in reporting on international cases — and the British Council, along with rules to allow our musicians, actors and writers to tour Europe and beyond.

If I were trying to promote Britain’s soft power, the first thing I’d do is to fund its ad revenue from podcasts. It can’t be much and it’s hard to believe that it’s not good soft-power value for money. But then, being a podcasting tragic, as Mandy Rice Davies once said in a different context “He would say that, wouldn’t he.”

PS: This newsletter being grimly evidence based, I checked out my claim above that podcast advertising doesn’t earn much. I regret to say that it kind of does. It yields £76 million per annum which is a lot higher than I thought it would be. That’s out of a total turnover of £5.7 billion — about ten times Australia’s ABC. I expect it’s still worth it for Britain’s soft power, but since podcast advertising is built around geocoded internet addresses, my next idea would be for governments to fund their share of the load. Our government could buy free rights to BBC podcasts and sell them the same access to ours — with the balance favouring them presumably.

My cattle farming mum, a cousin of Banjo Patterson would have loved these pictures (and these cows)

Jonathan Rauch on liberalism

If you don’t think liberalism propounds life-enhancing, freedom-giving, justice-advancing values, ask a homosexual who was born at a time when homosexuality was a crime, a sin, and a mental disease. Ask an atheist who was born at a time when atheists faced widespread discrimination and were unelectable to high public office. Ask a Jew who was born at all because his Polish grandparents found welcome in our liberal republic. And don’t try to tell that person—me, as it happens—that liberalism is hollow, value-free, or without courage, meaning, and hope.

Liberalism is not sufficient to make you happy or fulfilled. But it is necessary. It gives you much, much more to work with than any of its presumptive competitors. We liberals have a great story to tell. We need to work harder to evangelize others—and to renew our faith in ourselves.

And they filled her with joy

A lovely story about a lovely story:

Early in the pandemic, Loren Long and his wife, Tracy, rescued Charlie, a tricolor hound with baleful eyes and a foghorn howl. He had energy to burn, so Long started running with him on a stretch of the Little Miami Scenic Trail, which meanders nearly 78 miles from Springfield, Ohio, to Cincinnati.

Along their daily route, the pair passed an abandoned, rusted-out school bus moldering at the far end of a field. The faded yellow blended into a dense camouflage of trunks and leaves, but something about the bus caught Long’s eye. …

“I’m running along, and I’m like, Somehow that bus seems happy,” Long said. “I thought, How is she happy? She’s not supposed to be abandoned in a paddock, sinking into mud, with rust all over her and goats climbing in and out.” …

Eventually, Long grabbed a battered Moleskine and started writing. The words flowed; the voice came easily. In his telling, the bus goes through five incarnations. First it delivers children to school. Then it transports the elderly to the library. Later, parked in a quiet corner of a city, the bus becomes a shelter for people with nowhere else to go. Eventually the bus gets towed to a field near a river and the goats move in.

The ending is a surprise. No matter who or what comes into contact with the bus, her response is the same: “And they filled her with joy.” This refrain repeats five times.

It’s a simple story — the biography of a familiar part of ordinary life. But its creation became an all-consuming process unlike any he’s written or illustrated over the past two decades. …

In August 2022, Roaring Brook acquired “The Yellow Bus” based on the story and one painting. Then Long had to tackle the rest of the pictures. …

To ease this process — and to help himself visualize the bus’s world — Long decided to build a three-dimensional model of the valley where the book takes place. He thought this would take a week, maybe 10 days. It took two months. He thought the project would fit on a card table. Instead it sprawled to 10 feet, displacing a couch and claiming half of Long’s studio.

When his sons visited, they took in the rangy landscape dotted with miniature houses, handmade hay bales and toy vehicles leftover from their childhood. Their verdict was swift: “Dad, you’re crazy.” …

The model appears, stretching the length of the room — a colorful diorama dotted with houses, cows, fences, a river, a graveyard and even the wood frame of a building under construction. …

Long went through rolls of masking tape and Scotch tape. He painted the whole expanse white. Then he repainted it in color.

“This is the entire setting of the book. Nothing is in the book that isn’t here ….”

As he labored over his miniature universe in 10-hour stretches, Long had some doubts: “Am I just spinning my wheels? Am I wasting my time?” …

The all-consuming enterprise turned out to be, as Long put it, “the most fun I’ve had practically since junior high school.” It gave him something to focus on, and helped him envision the bus’s route through a valley that changes with time, technology and weather.

It was also a family affair: Tracy Long located the toy vehicles, the model railroad supplies and a few additional school buses. If she was baffled by her husband’s efforts, she didn’t let on.

“She could probably sense that I was excited I was doing something different,” Long said. (He dedicated “The Yellow Bus” to her.) …

The only color comes from the bus and its riders or visitors. If a person is in contact with the bus, that person appears in color.

Clark said, “We kept going back to that line, ‘They filled her with joy.’ Everything inside the bus or touching the bus would feel her service and her warmth.”

That warmth appears in the full spectrum of the rainbow. …

“It’s about purpose in life, the passage of time and the simple human feeling we get from doing something for others,” Long said. “That resonated with me.” …

After reading “The Yellow Bus” to a school group last spring, Long asked students why the bus was happy, even as her life changed for the worse. Hands shot up. Answers varied: She had friends. She was yellow. Finally, one girl said, “She likes to be used.”

Long understood what she meant. He said, “The bus likes to be useful.”

Who doesn’t?

Cromwell the killer

The second installment of an interesting new biography of Oliver Cromwell.

Already in the first volume, published in 2019 and taking Cromwell from his birth in 1599 to 1646, Hutton adopted a far more sceptical attitude towards Cromwellian holy writ, accepting Cromwell’s own account of events only where this could be independently verified. Hutton was fully alive to his extraordinary qualities – to the persuasive if rough-hewn parliamentary orator, the self-taught but brilliant master of military strategy, the born-again Puritan with an intensely personal relationship with an all-guiding God. But careful testing of Cromwell’s own version of events also revealed him as an ambitious self-promoter who lied shamelessly to blacken his rivals and get them out of the way, and as a man who was ruthless in killing ‘God’s enemies’ but seemed to enjoy it a little too much.

This new volume covers a much shorter period than the first – the seven years from 1647 to 1653 – but it is perhaps the most crisis-filled and controversial in British history, an era that witnessed the rise of the Parliamentarian army as an independent player in British politics, the trial and execution of the king, England’s transformation from a monarchy into a republic, and a succession of bloody wars that imposed the new government’s rule throughout the British Isles.

Those years also saw the most vertiginous rise to power witnessed in Europe before Napoleon’s. At their outset, Cromwell was just one of a number of prominent army officer MPs; by 1653 he was the conqueror of all four Stuart nations and on the verge of becoming their quasi-king. In almost every important event of the intervening years, Cromwell was there.

That, however, is where the historical consensus ends. How much Cromwell was involved; how far he was responsible for outcomes; the motives and purposes of his actions: all these remain hotly disputed. Hutton’s narrative is therefore a miracle of concision. In just under four hundred fast-paced pages, he tracks Cromwell’s involvement in an astonishingly complex and historically contested series of events, confounding any number of hoary orthodoxies along the way.

Hutton is less interested in penetrating the inner recesses of Cromwell’s soul than in gauging his impact on the world around him. In his retelling, Cromwell’s actions lose nothing of their boldness and grandeur, but his account often reveals a deep hypocrisy and consequences that were profoundly malign. Nowhere were these more evident, Hutton contends, than in Cromwell’s actions in obstructing a viable political settlement with the king after the First Civil War’s end in 1646. In the spring of 1647, the English Parliament was on the verge of reaching a settlement with Charles I that would have reinstated the monarch with limited powers and established a new centralised national church, whose expected first task was the suppression of the multitude of religious sects that had proliferated amid the disorders of civil war.

Cromwell, who counted himself one of these sectaries, viewed things very differently. These were ‘God’s people’, the religious radicals whom he had actively favoured as officers, first within his own regiment and then in the ‘new-modelled’ Parliamentarian army. His dependence on their allegiance, Hutton suggests, locked Cromwell into a Faustian pact: he could not abandon his fellow sectaries to future persecution, but that in turn committed him to rejecting any postwar settlement that the majority in Parliament was likely to produce.

Protecting those ‘brethren’ became the lodestar that guided his actions for most of his political career. Apart from an abortive foray into negotiations with the king in the late summer of 1647, Cromwell was consistently at the forefront of the army’s efforts to avert a settlement, from the spring of 1647 through to the army’s full-scale coup d’état over the winter of 1648–9. In the revolution that followed – which saw the trial and execution of the king and the creation of a new English republic – Cromwell sought to create a world that would at last be safe for himself and his fellow Puritan ‘saints’. …

Hutton’s life of Cromwell is still a work in progress. But with two volumes now in print, it is already a monumental achievement – the first in the great battalion of Cromwellian biographies to escape the long shadow cast by the Carlylean figure standing outside Westminster Hall.

Magnificent Bridges

I’m not sure how magnificent this one is, but it’s certainly spectacular.

Some more bad news from RCTs

Give people money — they don’t seem to use it particularly well. Who knew?

John Quiggin on how the view from the Chairman’s Lounge doomed REX

And my comment:

Great piece John. My own thoughts on this went in a slightly different direction. Numerous practices in government favour large incumbents. As someone who's consulted, you're probably aware of the 'panel' system according to which governments purchase professional services. To maximise competition (or the appearance thereof) they hold tenders to get on panels and once on such a panel anyone in the relevant agency can purchase services on pre-agreed terms from any firm that managed to get on the panel.

Problem is, this means that they typically want large firms with comprehensive offerings on the panel so they can always get what they want. As we pointed out in a report to the AG's Department years ago, this removes the incentive to develop collaborative and cost effective relationships with smaller firms.

Similarly I think it's true that the incumbents enjoy huge advantages in selling to government. It's remarkable how shy Rex was of pricing its flights in the main trunk routes on the eastern seaboard at anything like those being asked by Qantas and Virgin. I assume because they couldn't get politicians and bureaucrats on board. I suspect that Chairman's Lounge membership was just a small part of this.

Do you know?

Panhandling in the USA

David Bentley Hart is, as his Wikipedia profile says, a “writer, fiction author, philosopher, religious studies scholar, critic, and theologian.” He has been astonishingly prolific, having produced “over one thousand essays, reviews, and papers as well as twenty-four books (including translations)”.

Oh, and the other thing he is is “an American”. So, facing a serious health issue, his insurer is quibbling over the fine print. So he’s passing round the hat.

Go nuke or stop poking the bear: Percy Allan

Making our own military part of America’s capability against China is the worst of all worlds according to Percy.

Australia is fusing its navy, air force and army with America’s military forces. It’s called shifting from “interoperability” to “interchangeability”. … In essence under “interoperability” there are two separate national chains of command working jointly, whereas under “interchangeability” there is single chain of command. Under the latter it is doubtful the junior partner could break the chain of command and insist it call its own shots if the senior partner got into a skirmish not of Australia’s doing.

Without nuclear arms Australia should not be a party to confronting China

As such the Australian mainland could be the first casualty in an American war with China because we would be the weak link in America’s war machine without our own nuclear weapons.

Australian owned Virginia Class and AUKUS submarines carrying cruise missiles with conventional war heads would not provide a meaningful MAD deterrence.

And we have no guarantee from America that if a foreign power nuked Australia, America would nuke it in turn since that could cause a nuclear attack on America itself.

Worse still, unlike America we do not have an air defence system to intercept missile and drone attacks on our capital cities nor will we have such a protective shield in the foreseeable future.

Australia’s choice – get nuclear armed or stay conventionally armed?

Did tweaking accounting standards crash growth?

A fascinating question asked by my favourite civil servant in all the world — until he stopped being one — Andy Haldane.

Accounting rules rarely arouse excitement — even among accountants. This neglect is mis- placed. Accounting is the DNA of capitalism. And accounting rules have been pivotal in shaping the fortunes of companies and economies over many centuries, for good and ill.

Historically, accounting systems have been used to explain the rise and fall of nations ever since their emergence in ancient Mesopotamia. Goethe called double-entry bookkeeping one of the finest inventions of the human mind. Political philosophers such as Adam Smith and Max Weber assigned accounting systems a central role in explaining the flour- ishing of modern corporations and economies.

That is not to say these rules have been uncontroversial. A particular bone of contention has been the accounting valuation of assets, whether at market prices (“fair value”) or his- toric cost.

The US, for example, shifted towards fair values in the early years of the 20th century. But in 1938, in the teeth of the Depression, President Roosevelt moved back to historic cost accounting due to concerns that fair values were causing fire sales of assets and aggravat- ing economic distress. Similar pivots away from fair value occurred in the 1990s and in the wake of the global financial crisis.

At the start of the 21st century, countries in the EU changed accounting rules for listed companies to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These had a much stronger basis in fair value. The 2005 reforms had the same aims as those in the US a cen- tury earlier — improved corporate transparency, a lower cost of capital and higher levels of business investment.

Taken at face value, however, results have not been consistent with these objectives. Busi- ness investment by EU companies, relative to sales, has halved since 2005. For some countries, including the UK, business investment has been materially lower, relative to GDP, than in the US where Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) maintained a historic cost focus.

The public policy question to ask is whether these patterns are causal. There are good the- oretical grounds for thinking they might be if fair value accounting rules encourage managers to take short-term decisions. In particular, they may cause companies to prioritise shareholder payouts, inflated by asset price inflation, over reinvesting. If so, this account- ing-induced short-termism could harm business investment and economic growth over the medium term. A recent econometric analysis of more than 5,000 listed EU companies over the past 30 years by Vera Palea, Alessandro Migliavacca and myself supports this. After controlling for other factors, the switch to IFRS accounting rules is found to have damped business investment by between a third and a quarter, given available opportunit- ies. This has affected every sector.

The primary driver of this investment drag has been the rise in payouts (dividends and buybacks) to shareholders. Since 2005, payouts have doubled as a ratio of sales among lis- ted EU companies. Prior to the introduction of IFSR, fewer than 10 per cent of EU-listed companies paid out more to shareholders each year than they invested. By 2019, that had risen to around a third.

While the study focuses on non-financial companies, there are good grounds for believing similar effects operate among financial firms such as pension funds. Accounting and regu- latory rules (Solvency II) led to pension funds’ liabilities being, in effect, marked-to-mar- ket. This contributed to their sharp fall in willingness to invest in companies for the long term. During this century, UK pension fund investment in UK-listed companies has fallen from over 50 per cent to around 4 per cent of their assets.

The costs are not only in lower investment and growth. In follow-up analysis, Palea and co-authors estimate that IFRS rules have added to EU carbon emissions by around 15-30 per cent per year, relative to a GAAP benchmark, given their adverse impact on investment in green technologies. Accounting-induced short-termism has been a headwind to green growth.

With growth subdued and progress towards net zero slow, it is an ideal time for Europe to reconsider whether accounting standards support green growth objectives. In the UK, unencumbered by EU Directives but with a larger growth and investment deficit, a new government offers the perfect opportunity for a rethink and overhaul. Today, as in Depression-era America, IFRS may not be among the finest inventions of the human mind.

George Martin and I agree on the least good Beatles songs

Being silly: Micallef masterclass

The Minefield is a great experiment in radio — and as an experiment it doesn’t always come off, but good on them for trying it. I usually find it is a bit too discursive so it doesn’t always hold my interest. I’d like to see it edited back somehow — but that is mostly impossible with live discussion. Having listened to the opening five minutes or so I skipped to the middle. I found the focus on a single word “silly” as opposed to other words like “absurd”, “farce”, “satire” somehow a little to constraining, or perhaps too ‘academic’ for my liking. But I listened to where Shaun Micallef was brought in (at 24.20) and loved listening from there on. Micallef wasn’t trying to be funny, but rather to contribute to the discussion. And his knowledge and intelligence shone through.

How Do You Find a Good Manager?

Ben Weidmann, Joseph Vecci, Farah Said, David J. Deming & Sonia R. Bhalotra, Paper here.

This paper develops a novel method to identify the causal contribution of managers to team performance. The method requires repeated random assignment of managers to multiple teams and controls for individuals’ skills. A good manager is someone who consistently causes their team to produce more than the sum of their parts. Good managers have roughly twice the impact on team performance as good workers. People who nominate themselves to be in charge perform worse than managers appointed by lottery, in part because self-promoted managers are overconfident, especially about their social skills. Managerial performance is positively predicted by economic decision-making skill and fluid intelligence – but not gender, age, or ethnicity. Selecting managers on skills rather than demographics or preferences for leadership could substantially increase organizational productivity.

Heaviosity half-hour

Christopher Lasch: The revolt of the elites

I’ve never read much Lasch. I love the titles of some of his books, particularly The culture of narcissism. I’m good with the analysis, but it’s a bit preachy and long winded. His books are better as articles and I don’t necessarily want to read the whole things. On reflection, I think this problem of mine is a problem with single themed non-fiction books about contemporary events and/or culture. Lasch’s were some of the best. But even with the best, many could do with a good paring down.

In any event his last, posthumously published book The revolt of the elites and the betrayal of democracy is a bit like this, but there’s some great stuff in it. I thought this treatment of Horace Mann (whom I’d never heard of) was particularly good, and published nearly 30 years ago prophetic of trends that have just continued to our own times.

The Common Schools

Horace Mann and the Assault on Imagination

If we cast a cold eye over the wreckage of the school system in America, we may find it hard to avoid the impression that something went radically wrong at some point, and it is not surprising, therefore, that so many critics of the system have turned to the past in the hope of explaining just when things went wrong and how they might be set to rights.* The critics of the fifties traced the trouble to progressive ideologies, which allegedly made things too easy for the child and drained the curriculum of its intellectual rigor. In the sixties a wave of revisionist historians insisted that the school system had come to serve as a “sorting machine,” in Joel Spring’s phrase, a device for allocating social privileges that reinforced class divisions while ostensibly promoting equality. Some of these revisionists went so far as to argue that the common school system was distorted from the outset by the requirements of the emerging industrial order, which made it almost inevitable that the schools would be used not to train an alert, politically active body of citizens but to inculcate habits of punctuality and obedience.

There is a good deal to be learned from the debates that took place in the formative period of the school system, the 1830s and 1840s, but an analysis of those debates will not support any such one-dimensional interpretation of the school’s function as an agency of “social control.” I do not see how anyone who reads the writings of Horace Mann, which did so much to justify a system of common schools and to persuade Americans to pay for it, can miss the moral fervor and democratic idealism that informed Mann’s program. It is true that Mann resorted to a variety of arguments in favor of common schools, including the argument that they would teach steady habits of work. But he insisted that steady habits would benefit workers as well as employers, citing in favor of this contention the higher wages earned by those who enjoyed the advantages of a good education. He was careful to point out, moreover, that a positive assessment of the effects of schooling on men’s “worldly fortunes or estates” was far from the “highest” argument in favor of education. Indeed, it might “justly be regarded as the lowest” (V:81). More important arguments for education, in Mann’s view, were the “diffusion of useful knowledge,” the promotion of tolerance, the equalization of opportunity, the “augmentation of national resources,” the eradication of poverty, the overcoming of “mental imbecility and torpor,” the encouragement of light and learning in place of “superstition and ignorance,” and the substitution of peaceful methods of governance for coercion and warfare (IV:10; V:68, 81, 101, 109; VII:187). If Mann pretty clearly preferred the high ground of moral principle to the lower ground of industrial expediency, he could still appeal to prudential motives with a good conscience, since he did not perceive a contradiction between them. Comforts and conveniences were good things in themselves, even if there were loftier goods to aim at. His vision of “improvement” was broad enough to embrace material as well as moral progress; it was precisely their compatibility, indeed their inseparability, that distinguished Mann’s version of the idea of progress from those that merely celebrated the wonders of modern science and technology.

As a child of the Enlightenment, Mann yielded to no one in his admiration for science and technology, but he was also a product of New England Puritanism, even though he came to reject Puritan theology. He was too keenly aware of the moral burden Americans inherited from their seventeenth-century ancestors to see a higher standard of living as an end in itself or to join those who equated the promise of American life with the opportunity to get rich quick. He did not look kindly on the project of getting enormously rich even in the long run. He deplored extremes of wealth and poverty—the “European theory” of social organization, as he called it—and upheld the “Massachusetts theory,” which stressed “equality of condition” and “human welfare” (XII:55). It was to escape “extremes of high and low,” Mann believed, that Americans had “fled” Europe in the first place, and the reemergence of those extremes, in nineteenth-century New England, should have been a source of deepest shame to his countrymen (VII: 188, 191). When Mann dwelled on the accomplishments of his ancestors, it was with the intention of holding Americans to a higher standard of civic obligation than the standard prevailing in other countries. His frequent appeals to the “heroic period of our country’s history” did not issue from a “boastful or vain-glorious spirit,” he said. An appreciation of America’s mission brought “more humiliation than pride” (VII: 195). America should have “stood as a shining mark and exemplar before the world,” instead of which it was lapsing into materialism and moral indifference (VII: 196).

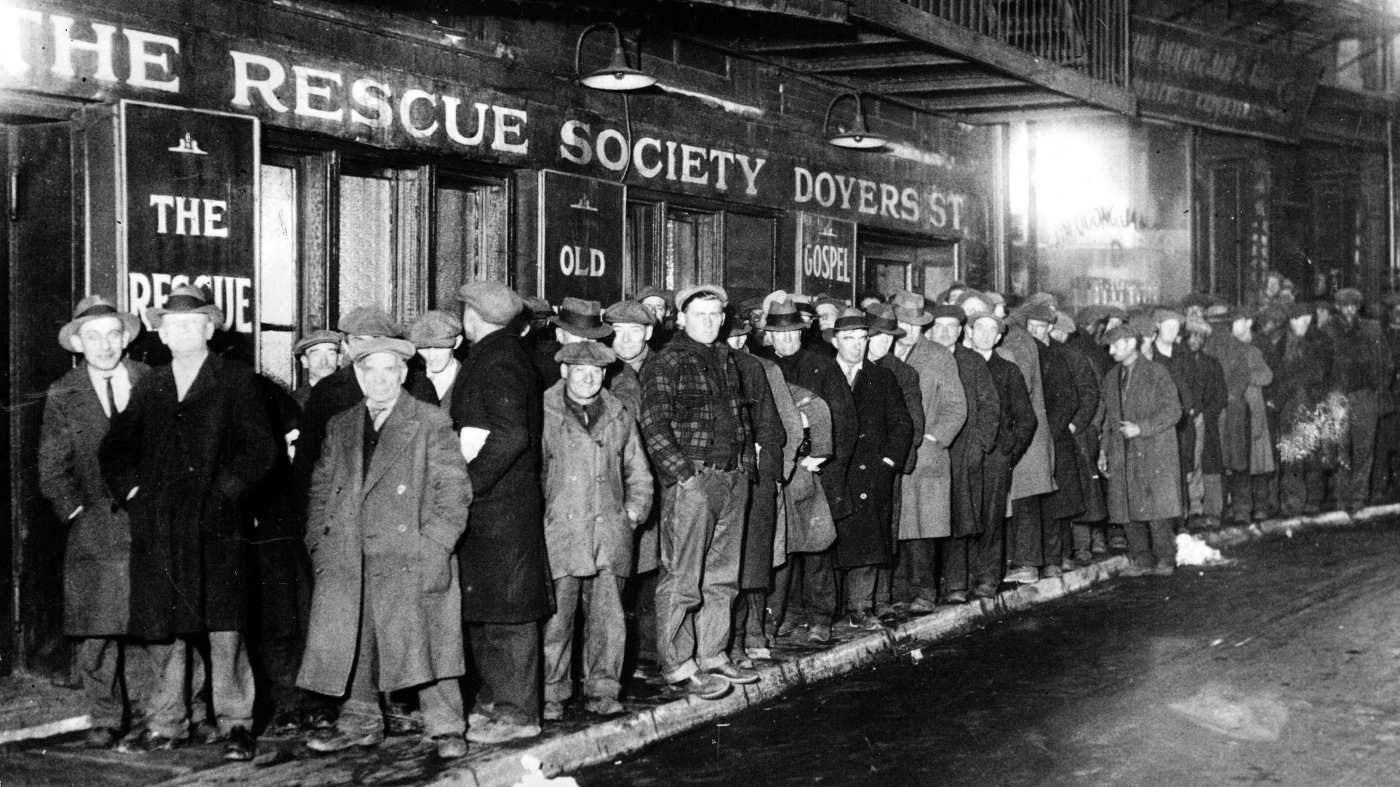

It is quite pointless to ask whether reformers like Horace Mann were more interested in humanitarianism than in work discipline and “social control.” A good deal of fruitless debate among historians has been devoted to this question. Mann was not a radical, and he was undeniably interested in social order, but that does not make him any less a humanitarian. He was genuinely moved by the spectacle of poverty and suffering, though he also feared that poverty and suffering would breed “agrarianism,” as he and his contemporaries called it—the “revenge of poverty against wealth” (XII:60). When he preached the duty to “bring forward those unfortunate classes of the people, who, in the march of civilization, have been left in the rear,” there is no reason to think that he was concerned only with the danger of social revolution (XII: 135). He defended property rights, to be sure, but he denied that property rights were “absolute and unqualified” (X:115). The earth was given to mankind “for the subsistence and benefit of the whole race,” and the “rights of successive owners” were “limited by the rights of those who are entitled to the subsequent possession and use” (X:114–15). Every generation had an obligation to improve its inheritance and to pass it on to the next. “The successive generations of men, taken collectively, constitute one great commonwealth” (X:127). The doctrine of absolute property rights, which denied the solidarity of mankind, was a morality for “hermits” (X:120). In Mann’s view, the “successive holders” of property were “trustees, bound to the faithful execution of their trust, by the most sacred obligations” (X:127). If they defaulted on those obligations, they could expect “terrible retributions” in the form of “poverty and destitution,” “violence and misrule,” “licentiousness and debauchery,” “political profligacy and legalized perfidy” (X:126). Here Mann was truly prophetic, in the strict sense of the term. He called his people to account, pointing out that they had inherited a demanding set of obligations to live up to and foretelling the “certain vengeance of Heaven” if they failed (X:126). He was a prophet in the vulgar sense as well: His predictions have come true—his predictions, that is, of the specific evils that would follow from a failure to provide a system of education assuring “knowledge and virtue,” the necessary foundations of a republican form of government (XII: 142). Who can look at America today without recognizing the accuracy of Mann’s cautionary rhetoric, right down to the “legalized perfidy” of our political leaders? The only thing Mann failed to foresee was the drug epidemic, though that could be included, I suppose, under the heading of “licentiousness and debauchery.”

Yet Mann’s efforts on behalf of the common schools bore spectacular success, if we consider the long-term goals (and even the immediate goals) he was attempting to promote. His countrymen heeded his exhortations after all. They built a system of common schools attended by all classes of society. They rejected the European model, which provided a liberal education for the children of privilege and vocational training for the masses. They abolished child labor and made school attendance compulsory, as Mann had urged. They enforced a strict separation between church and state, protecting the schools from sectarian influences. They recognized the need for professional training of teachers, and they set up a system of normal schools to bring about this result. They followed Mann’s advice to provide instruction not only in academic subjects but in the “laws of health,” vocal music, and other character-forming disciplines (VI:61, 66). They even followed his advice to staff the schools largely with women, sharing his belief that women were more likely than men to govern their pupils by the gentle art of persuasion. They honored Mann himself, even during his lifetime, as the founding father of their schools. If Mann was a prophet in some respects, he was hardly a prophet without honor in his own country. He succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of most reformers, yet the result was the same as if he had failed.

Here is our puzzle, then: Why did the success of Mann’s program leave us with the social and political disasters he predicted, with uncanny accuracy, in the event of his failure? To put the question this way suggests that there was something inherently deficient in Mann’s educational vision, that his program contained some fatal flaw in its very conception. The flaw did not lie in Mann’s enthusiasm for “social control” or his halfhearted humanitarianism. The history of reform—with its high sense of mission, its devotion to progress and improvement, its enthusiasm for economic growth and equal opportunity, its humanitarianism, its love of peace and its hatred of war, its confidence in the welfare state, and, above all, its zeal for education—is the history of liberalism, not conservatism, and if the reform movement gave us a society that bears little resemblance to what was promised, we have to ask not whether the reform movement was insufficiently liberal and humanitarian but whether liberal humanitarianism provides the best recipe for a democratic society.

We get a little insight into Mann’s limitations by considering his powerful aversion to war—superficially one of the more attractive elements of his outlook. Deeply committed to the proposition that a renunciation of war and warlike habits provided an infallible index of social progress, of the victory of civilization over barbarism, Mann complained that school and town libraries were full of history books glorifying war.

How little do these books contain, which is suitable for children! … Descriptions of battles, sackings of cities, and the captivity of nations, follow each other with the quickest movement, and in an endless succession. Almost the only glimpses, which we catch of the education of youth, present them, as engaged in martial sports, and the mimic feats of arms, preparatory to the grand tragedies of battle;—exercises and exhibitions, which, both in the performer and the spectator, cultivate all the dissocial emotions, and turn the whole current of the mental forces into the channel of destructiveness [III:58].

Mann called himself a republican (in order to signify his opposition to monarchy), but he had no appreciation of the connection between martial virtue and citizenship, which had received so much attention in the republican tradition. Even Adam Smith, whose liberal economics dealt that tradition a crippling blow, regretted the loss of armed civic virtue. “A man, incapable either of defending or of revenging himself, evidently wants one of the most essential parts of the character of a man.” It was a matter for regret, in Smith’s view, that the “general security and happiness which prevail in ages of civility and politeness” gave so “little exercise to the contempt of danger, to patience in enduring labor, hunger, and pain.” Given the growth of commerce, things could not be otherwise, according to Smith, but the disappearance of qualities so essential to manhood and therefore to citizenship was nevertheless a disturbing development. Politics and war, not commerce, served as the “great school of self-command.” If commerce was now displacing “war and faction” as the chief business of mankind (to the point where the very term “business” soon became a synonym for commerce), the educational system would have to take up the slack, sustaining values that could no longer be acquired through participation in public events.

Horace Mann, like Smith, believed that formal education could take the place of other character-forming experiences, but he had a very different conception of the kind of character he wanted to form. He shared none of Smith’s enthusiasm for war and none of his reservations about a society composed of peace-loving men and women going about their business and largely indifferent to public affairs. As we shall see, Mann’s opinion of politics was no higher than his opinion of war. His educational program did not attempt to supply the courage, patience, and fortitude formerly supplied by “war and faction.” It therefore did not occur to him that historical narratives, with their stirring accounts of exploits carried out in the line of military or political duty, might fire the imagination of the young and help to frame their own aspirations. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he distrusted any sort of appeal to the imagination. His educational philosophy was hostile to imagination as such. He preferred fact to fiction, science to mythology. He complained that young people were given a “mass of fictions,” when they needed “true stories” and “real examples of real men” (III:90–91). But his conception of the truths that could safely be entrusted to children turned out to be very limited indeed. History, he thought, “should be rewritten” so as to enable children to compare “the right with the wrong” and to give them “some option of admiring and emulating the former” (III:59–60). Mann’s objections to the kind of history children were conventionally exposed to was not only that it acclaimed military exploits but that right and wrong were confusingly mixed up together—as they are always mixed up, of course, in the real world. It was just this element of moral ambiguity that Mann wanted to eliminate. “As much of History now stands, the examples of right and wrong … are … brought and shuffled together” (III:60). Educators had a duty to sort them out and to make it unambiguously clear to children which was which.

Mann’s plea for historical realism betrayed not only an impoverished conception of reality but a distrust of pedagogically unmediated experience—attitudes that have continued to characterize educational thinking ever since. Like many other educators, Mann wanted children to receive their impressions of the world from those who were professionally qualified to decide what it was proper for them to know, instead of picking up impressions haphazardly from narratives (both written and oral) not expressly designed for children. Anyone who has spent much time with children knows that they acquire much of their understanding of the adult world by listening to what adults do not necessarily want them to hear—by eavesdropping, in effect, and just by keeping their eyes and ears open. Information acquired in this way is more vivid and compelling than any other since it enables children to put themselves imaginatively in the place of adults instead of being treated simply as objects of adult solicitude and didacticism. It was precisely this imaginative experience of the adult world, however—this unsupervised play of young imaginations—that Mann hoped to replace with formal instruction. Thus he objected to “novels and all that class of books,” which offered “mere amusement, as contradistinguished from instruction in the practical concerns of life.” His objection, to be sure, was directed mainly against “light reading,” which allegedly distracted people from “reflection upon the great realities of experience”; but he did not specifically exempt more serious works of fiction, nor is there any indication, in the vast body of his educational writings, that he recognized the possibility that the “great realities of existence” are treated more fully in fiction and poetry than in any other kind of writing (III:60).

The great weakness in Mann’s educational philosophy was the assumption that education takes place only in schools. Perhaps it is unfair to say that Mann bequeathed this fatal assumption to subsequent generations of educators, as part of his intellectual legacy. An inability to see beyond the school after all—a tendency to speak as if schooling and education were synonymous terms—should probably be regarded as an occupational hazard of professional educators, a form of blindness that is built into the job. Still, Mann was one of the first to give it official sanction. His thinking on this point was more striking in what it omitted than in what it said in so many words. It simply did not occur to him that activities like politics, war, and love—the staple themes of the books he deplored—were educative in their own right. He believed that partisan politics, in particular, was the bane of American life. In his Twelfth Report he described the excitement surrounding the presidential election of 1848 in language that unmistakably conveyed the importance of politics as a form of popular education, only to condemn the campaign (in which he himself had won election to the House of Representatives) as a distraction from his more important work as an educator.

Agitation pervaded the country. There was no stagnant mind; there was no stagnant atmosphere. … Wit, argument, eloquence, were in such demand, that they were sent for at the distance of a thousand miles—from one side of the Union to the other. The excitement reached the humblest walks of life. The mechanic in his shop made his hammer chime to the music of political rhymes; and the farmer, as he gathered in his harvest, watched the aspects of the political, more vigilantly than of the natural, sky. Meetings were every where held. … The press showered its sheets over the land, thick as snow-flakes in a wintry storm. Public and private histories were ransacked, to find proofs of honor or proofs of dishonor; political economy was invoked; the sacred names of patriotism, philanthropy, duty to God, and duty to man, were on every tongue.

The campaign of 1848, as Mann described it, elicited an intensity of popular response that would be the envy of our own times, yet Mann could find in all this only “violence” and “din”—a “Saturnalia of license, evil speaking, and falsehood.” He wished that the energy devoted to politics could be devoted instead to “getting children into the schools” (XII:25–26). Elsewhere in the same report he likened politics to a conflagration, a fire raging out of control, or again to a plague, an “infection” or “poison” (XII:87).

Reading these passages, one begins to see that Mann wanted to keep politics out of the school not only because he was afraid that his system would be torn apart by those who wished to use it for partisan purposes but because he distrusted political activity as such. It produced an “inflammation of the passions” (XII:26). It generated controversy—a necessary part of education, it might be argued, but in Mann’s eyes, a waste of time and energy. It divided men instead of bringing them together. For these reasons Mann sought not only to insulate the school from political pressures but to keep political history out of the curriculum. The subject could not be ignored entirely; otherwise children would gain only “such knowledge as they may pick up from angry political discussions, or from party newspapers.” But instruction in the “nature of a republican government” was to be conducted so as to emphasize only “those articles in the creed of republicanism, which are accepted by all, believed in by all, and which form the common basis of our political faith.” Anything controversial was to be passed over in silence or, at best, with the admonition that “the schoolroom is neither the tribunal to adjudicate, nor the forum to discuss it” (XII:89).

Although it is somewhat tangential to my main point, it is worth pausing to see what Mann considered to be the common articles in the republican creed, the “elementary ideas” on which everyone could agree (XII:89). The most important of these points, it appears, were the duty of citizens to appeal to the courts, if wronged, instead of taking the law into their own hands, and the duty to change the laws “by an appeal to the ballot, and not by rebellion” (XII:85). Mann did not see that these “elementary ideas” were highly controversial in themselves or that others might quarrel with his underlying assumption that the main purpose of government was to keep order. But the substance of his political views is less germane to my purpose than his attempt to palm them off as universal principles. It is bad enough that he disguised the principles of the Whig party as principles common to all Americans and thus protected them from reasonable criticism. What is even worse is the way in which his bland tutelage deprived children of anything that might have appealed to the imagination or—to use his own term—the “passions.” Political history, taught along the lines recommended by Mann, would be drained of controversy, sanitized, bowdlerized, and therefore drained of excitement. It would become mild, innocuous, and profoundly boring, trivialized by a suffocating didacticism. Mann’s idea of political education was of a piece with his idea of moral education, on which he laid such heavy-handed emphasis in his opposition to merely intellectual training. Moral education, as he conceived it, consisted of inoculation against “social vices and crimes”: “gaming, intemperance, dissoluteness, falsehood, dishonesty, violence, and their kindred offenses” (XII:97). In the republican tradition—compared with which Mann’s republicanism was no more than a distant echo—the concept of virtue referred to honor, ardor, superabundant energy, and the fullest use of one’s powers. For Mann, virtue was only the pallid opposite of “vice.” Virtue was “sobriety, frugality, probity”—qualities not likely to seize the imagination of the young (XII:97).

The subject of morality brings us by a short step to religion, where we see Mann’s limitations in their clearest form. Here again I want to call into question the very aspects of Mann’s thought that have usually been singled out for the highest praise. Even his detractors—those who see his philanthropy as a cover for social control—congratulate Mann on his foresight in protecting the schools from sectarian pressures. He was quite firm on the need to banish religious instruction based on the tenets of any particular denomination. In his lifetime he was unfairly accused of banishing religious instruction altogether and thus undermining public morals. To these “grave charges” he replied, plausibly enough, that sectarianism could not be tolerated in schools that everyone was expected to attend—compelled to attend, if he were to have his way (XII:103). But he also made it clear that a “rival system of ‘Parochial’ or ‘Sectarian’ schools” was not to be tolerated either (XII:104). His program envisioned the public school system as a monopoly, in practice, if not in law. It implied the marginalization, if not the outright elimination, of institutions that might compete with the common schools.

His opposition to religious sectarianism did not stop with its exclusion from the public sector of education. He was against sectarianism as such, for the same reasons that made him take such a dim view of politics. Sectarianism, in his view, breathed the spirit of fanaticism and persecution. It gave rise to religious controversy, which was no more acceptable to Mann than political controversy. He spoke of both in images of fire. If the theological “heats and animosities engendered in families, and among neighbors, burst forth in a devouring fire” into school meetings, the “inflammable materials” would grow so intense that no one could “quench the flames,” until the “zealots” themselves were “consumed in the conflagration they have kindled” (XII:129). It was not enough to keep the churches out of the public schools; it was necessary to keep them out of public life altogether, lest the “discordant” sounds of religious debate drown out the “one, indivisible, all-glorious system of Christianity” and bring about the “return of Babel” (XII:130). The perfect world, as it existed in Mann’s head, was a world in which everyone agreed, a heavenly city where the angels sang in unison. He sadly admitted that “we can hardly conceive of a state of society upon earth so perfect as to exclude all differences of opinion,” but at least it was possible to relegate disagreements “about rights” and other important matters to the sidelines of social life, to bar them from the schools and, by implication, from the public sphere as a whole (XII:96).

None of this meant that the schools should not teach religion; it meant only that they should teach the religion that was common to all, or at least to all Christians. The Bible should be read in school, on the assumption that it could “speak for itself,” without commentaries that might give rise to disagreement (XII:117). Here again Mann’s program invites a type of criticism that misses the point. His nondenominational instruction is open to the objection that it still excluded Jews, Muhammadans, Buddhists, and atheists. Ostensibly tolerant, it was actually repressive in equating religion narrowly with Christianity. This is a trivial objection. At the time Mann was writing, it still made sense to speak of the United States as a Christian nation, but the reasoning on which he justified a nondenominational form of Christianity could easily be extended to include other religions as well. The real objection is that the resulting mixture is so bland that it puts children to sleep instead of awakening feelings of awe and wonder. Orestes Brownson, the most perceptive of Mann’s contemporary critics, pointed out in 1839 that Mann’s system, by suppressing everything divisive in religion, would leave only an innocuous residue. “A faith, which embraces generalities only, is little better than no faith at all.” Children brought up in a mild and nondenominational “Christianity ending in nothingness,” in schools where “much will be taught in general, but nothing in particular,” would be deprived of their birthright, as Brownson saw it. They would be taught “to respect and preserve what is”; they would be cautioned against the “licentiousness of the people, the turbulence and brutality of the mob,” but they would never learn a “love of liberty” under such a system.

Although Brownson did not share Mann’s horror of dissension, he too deplored the widening gap between wealth and poverty and saw popular education as a means of overcoming these divisions. Unlike Mann, however, he understood that the real work of education did not take place in the schools at all. Anticipating John Dewey, Brownson pointed out that

our children are educated in the streets, by the influence of their associates, in the fields and on the hill sides, by the influences of surrounding scenery and overshadowing skies, in the bosom of the family, by the love and gentleness, or wrath and fretfulness of parents, by the passions or affections they see manifested, the conversations to which they listen, and above all by the general pursuits, habits, and moral tone of the community.

These considerations, together with Brownson’s extensive discussion of the press and the lyceum, seemed to point to the conclusion that people were most likely to develop a love of liberty through exposure to wide-ranging public controversy, the “free action of mind on mind.”

Wide-ranging public controversy, as we have seen, was just what Mann wanted to avoid. Nothing of educational value, in his view, could issue from the clash of opinions, the noise and heat of political and religious debate. Education could take place only in institutions deliberately contrived for that purpose, in which children were exposed exclusively to knowledge professional educators considered appropriate. Some such assumption, I think, has been the guiding principle of American education ever since. Mann’s reputation as the founding father of the public school is well deserved. His energy, his missionary enthusiasm, his powers of persuasion, and the strategic position he enjoyed as secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education made it possible for him to leave a lasting mark on the educational enterprise. One might go so far as to say that the enterprise has never recovered from the mistakes and misconceptions built into it at the very outset.

Not that Horace Mann would be pleased with our educational system as it exists today. On the contrary, he would be horrified. Nevertheless, the horrors are at least indirectly a consequence of his own ideas, unleavened by the moral idealism with which they were once associated. We have incorporated into our schools the worst of Mann and somehow managed to lose sight of the best. We have professionalized teaching by setting up elaborate requirements for certification, but we have not succeeded in institutionalizing Mann’s appreciation of teaching as an honorable calling. We have set up a far-ranging educational bureaucracy without raising academic standards or improving the quality of teaching. The bureaucratization of education has the opposite effect, undermining the teacher’s autonomy, substituting the judgment of administrators for that of the teacher, and incidentally discouraging people with a gift for teaching from entering the profession at all. We have followed Mann’s advice to de-emphasize purely academic subjects, but the resulting loss of intellectual rigor has not been balanced by an improvement in the school’s capacity to nourish the character traits Mann considered so important: self-reliance, courteousness, and the capacity for deferred gratification. The periodic rediscovery that intellectual training has been sacrificed to “social skills” has led to a misplaced emphasis on the purely cognitive dimension of education, which lacks even Mann’s redeeming awareness of its moral dimension. We share Mann’s distrust of the imagination and his narrow conception of truth, insisting that the schools should stay away from myths and stories and legends and stick to sober facts, but the range of permissible facts is even more pathetically limited today than it was in Mann’s day.

History has given way to an infantilized version of sociology, in obedience to the misconceived principle that the quickest way to engage children’s attention is to dwell on what is closest to home: their families; their neighborhoods; the local industries; the technologies on which they depend. A more sensible assumption would be that children need to learn about faraway places and olden times before they can make sense of their immediate surroundings. Since most children have no opportunity for extended travel, and since travel in our world is not very broadening anyway, the school can provide a substitute—but not if it clings to the notion that the only way to “motivate” them is to expose them to nothing not already familiar, nothing not immediately applicable to themselves.

Like Mann, we believe that schooling is a cure-all for everything that ails us. Mann and his contemporaries held that good schools could eradicate crime and juvenile delinquency, do away with poverty, make useful citizens out of “abandoned and outcast children,” and serve as the “great equalizer” between rich and poor (XII:42, 59). They would have done better to start out with a more modest set of expectations. If there is one lesson we might have been expected to learn in the 150 years since Horace Mann took charge of the schools of Massachusetts, it is that the schools can’t save society. Crime and poverty are still with us, and the gap between rich and poor continues to widen. Meanwhile, our children, even as young adults, don’t know how to read and write. Maybe the time has come—if it hasn’t already passed—to start all over again.