Kamala’s awkward laugh

Some stars make awkwardness or lack of social fluency a feature rather than a bug. I’d say Nicole Kidman brings a kind of awkwardness to her characters and thereby somehow conveys their greater authenticity. Taylor Swift deploys a hint of awkwardness to give herself a relatability. Or so I fancy.

And then there’s awkwardness in politicians.

Sometimes their awkwardness is a sign that they’re keeping themselves intact as humangoes. That’s the premise of this column which doesn’t seem to put its best foot forward displaying its sympathy for a soccer player who bites his opponents. This is likened to the laugh Kamala uses for multiple purposes on the public stage. But however unfortunate it is to imply that perhaps Kamala should just bite her opponents, the point the columnist makes is worth making.

As I know from watching politicians at close quarters, sometimes you’re surprised that they can never quite make it into the elite political media performers club even though in private there’s no hint of the awkwardness that turns up on the screen.

One large political memory that dogs her, and makes people doubt her electability, is her performance in debates ahead of the 2020 Democratic nomination, when she suffered badly at the hands of her rivals. But she suffered for reasons that would actually be strengths were she to face Trump this November. That is, she started her political career as a prosecutor. … And as a prosecutor she did things that the liberals of 2019 and 2020 briefly believed they didn’t like, and that Democratic presidential hopefuls temporarily pretended to be against, but that pretty much everyone else heartily supports. She prosecuted people who’d committed crimes. She saw them convicted and sent to jail and prison. This made her an easy target for primary opponents playing to Left-wing voters. …

As the Democrat’s nominee in the national election, she won’t have this problem. In fact, the one time we’ve seen Harris on the national stage where she didn’t have to satisfy the niche politics and personalised cultural fetishes of the Left wing of the Democratic Party was the 2020 Vice Presidential Debate, when she clearly outperformed Mike Pence. … More to the point, she would stand in challenging contrast to her 78-year-old opponent, Donald Trump. …

Unfortunately for Trump and his fans, the rush of adrenaline that stood him from the floor of that Pennsylvania stage, triumphantly grazed, to shake his fist and yell “Fight!” a few times with blood scored across his face like warpaint, wore off almost at once. His 90-minute acceptance speech at the Republican Convention a few days later — in which he quickly abandoned his prepared text and lapsed into a list of complaints that he himself has rendered hackneyed with repetition — was one of the great missed opportunities in America’s recent political history. Handed such a propitious moment, Trump lacked the imagination, the discipline, the energy to exploit it. The fact that it went listlessly, boringly on for an hour and a half didn’t express stamina and vitality so much as inertia….

Harris, by contrast, has been a lively, relaxed, concise campaign speaker since her quick and dubious coronation. She’s in an enviable if not paradoxical position, where “(presumptive) Democratic Presidential Nominee” is the most comfortable, least risky, least political role she’s played in recent years. Running for president lets her be less of a political animal, as we’ve come to understand that species in the era of presidential primaries and personality contests. She no longer needs to placate progressives with waffling and apologies, which she isn’t very good at. And, between now and November, she won’t have to sit for intimate conversations with her sisters of political identity, where she’s often overdone the chummy relating and ended up generating cringeworthy content. She just has to be what she already is, an ambitious ex-prosecutor who wants millions of people she doesn’t know to vote her into a better job.

Love this summary of Biden by Bernie

Team B

Meanwhile a friend sent me this video of two of the most impressive Democrats in full flight and asked what I thought. Here’s what I thought:

They’ve very impressive and if the Democrats ran them as a presidential ticket in either order (Though I think Gretchen Whitmer would be the better presidential nominee). I’d be astonished if an indisciplined fascist loon like Donald Trump could beat them.

It highlights the cost of the timid careerism within the Democrats that these folks weren’t even able to run. Instead the movers and shakers in the party tugged the forelock to incumbent power until it looked like falling off the perch. And then once Biden’s candidacy became unviable, they immediately closed ranks and inserted the next incumbent.

On the other hand, having citizens’ juries on my mind for these last years, I find the hyper fluency of both of these folks deeply alienating. I don’t mean to disparage them personally. They might be good folks bent on doing good things for their people. And to do it, this is what they have to do. But here they are on their autocues playing themselves and pumping out the

liestalking points. Lies like Kamala has been ‘fighting for you’ in Washington. Now nothing against Kamala, but with the best will in the world, if Kamala really is doing the best for the people, 80 percent of her time will be taken up accommodating the demands of the powerful. That’s the system. But it’s no fun to say that, so Kamala is “fighting for us”.Consider the Swiss Prime Minister. You don’t know who he or she is do you? Neither do I. The position is rotated every year to give each of a seven member council the job. Imagine a political system that understood itself as eliciting and serving the needs of the people without fetishising the role of The Leader. It’s possible you know.

Fascinating interview with Penn of Penn and Teller

A really fascinating interview with Penn on his life (which involved homelessness leading to several years of jail!) And he offers some fascinating insights on working with Donald Trump, whom he said he enjoyed working with, and got on with but was the only person he’d ever met before or since with a particular characteristic. The ABC in its wisdom don’t allow you to download the file, but you can play it by clicking here, or on the image above.

X’s Community Notes’s promising new algorithm

Though we’re astonished by their openness to all, that’s not the secret sauce behind Wikipedia and open source software. Their openness just leverages the real miracle which is that they’re new kinds of meritocracies. Meritocracies of volunteers are particularly strong on people doing the work for intrinsic motivation. And rather than being banned, the trolls are managed largely by being rendered irrelevant. Anyone can deface a Wikipedia page, but it can be reset in minutes. Meanwhile those given greater authority on the site are those making the most and best contributions.

But it’s easier to adjudicate what’s good and bad on Wikipedia because of the NPOV — the neutral point of view. Wikipedia rewards accurate reporting of facts. It will tell you when Donald Trump was born and what crimes he has been convicted of. But, malignant narcissists can be a real drag as president, Wikipedia doesn’t even try to tell you whether he was a good president.

So what could be the equivalent standard of merit on social media? I think bridging algorithms fit that bill. One bridging algorithm would promote the views of those who are best thought of by those who disagree with them. Imagine how different X or other social media platforms would be if they deployed algorithms like that? Well X now does — only not on tweets, but on “Community Notes”.

It’s a feature that allows users to add context to tweets. This context can include additional information, clarifications, or corrections to the content of the tweet. The idea is to help provide more accurate and complete information to the audience, leveraging the collective knowledge and expertise of the community. These notes are visible to other users and can be rated for helpfulness, ensuring that the most useful information is highlighted. This feature aims to enhance the quality of information shared on the platform and combat misinformation.

Blockchain royalty Vitalik Buterin weighs in:

The last two years of

boughtnot boughtbought by Elon Musk for $44 billion last year, Elon enacted sweeping changes to the company's staffing, content moderation and business model, not to mention changes to the culture on the site that may well have been a result of Elon's soft power more than any specific policy decision. But in the middle of these highly contentious actions, one new feature on Twitter grew rapidly in importance, and seems to be beloved by people across the political spectrum: Community Notes.When you write a note, the note gets a score based on the reviews that it receives from other Community Notes members. These reviews can be thought of as being votes along a 3-point scale of

HELPFUL,SOMEWHAT_HELPFULandNOT_HELPFUL, but a review can also contain some other tags that have roles in the algorithm. Based on these reviews, a note gets a score. If the note's score is above 0.40, the note is shown; otherwise, the note is not shown.The way that the score is calculated is what makes the algorithm unique. Unlike simpler algorithms, which aim to simply calculate some kind of sum or average over users' ratings and use that as the final result, the Community Notes rating algorithm explicitly attempts to prioritize notes that receive positive ratings from people across a diverse range of perspectives. That is, if people who usually disagree on how they rate notes end up agreeing on a particular note, that note is scored especially highly.

There’s plenty more in the article, and I didn’t read it all, but it’s using similar kind of logic to the logic of bridging algorithms. X isn’t likely to migrate this to its main offering any time soon — it would cost them even more money than the craziness they’ve been going through already — but it’s great to see experience building with these kinds of approaches.

HT: Jim Savage

The Era of Predictive AI Is Almost Over

It has been a busy week and so your newsletter is a little shorter than usual. Not only that, but I’ve not even read this article. But it looks interesting — even if the graphic is a bit lame.

Weird medieval guys

And to make up for my awkward failings this week, here is the only known contemporary image of the famous attack of the 11th-century Spanish killer frog.

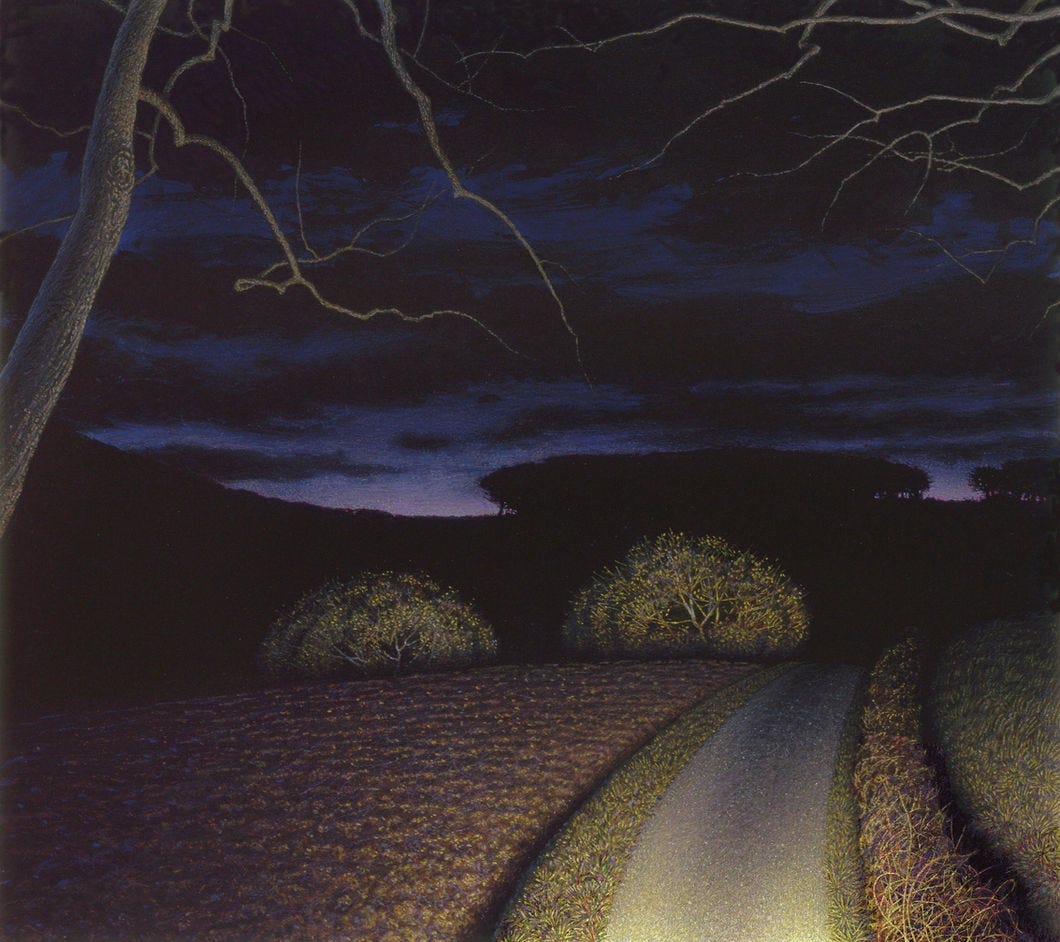

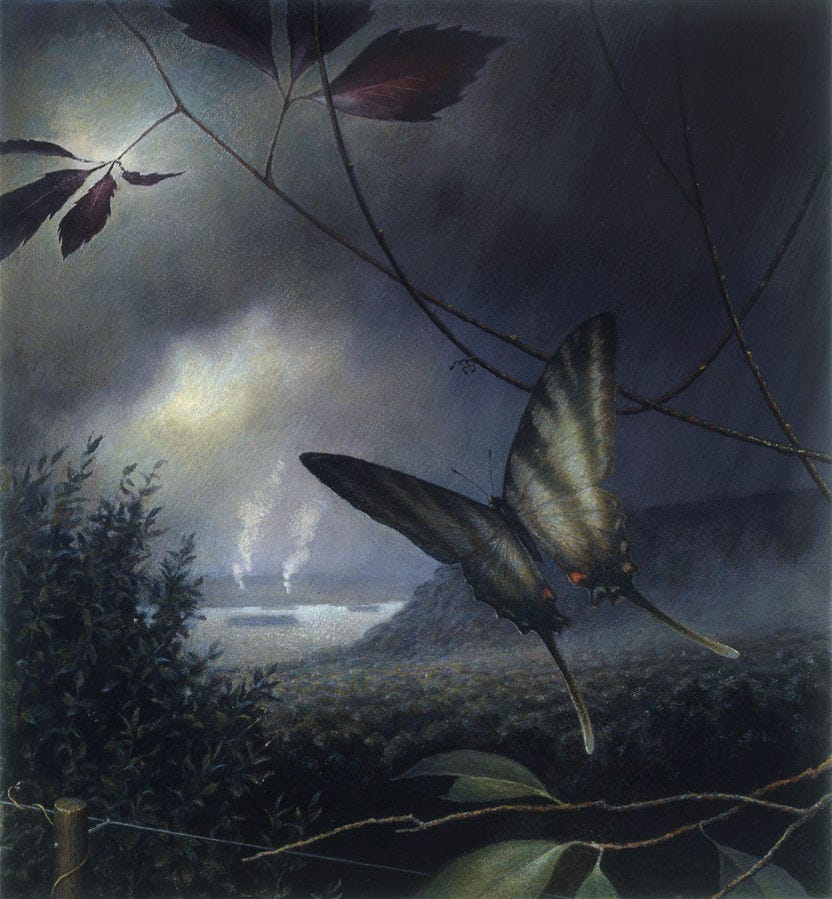

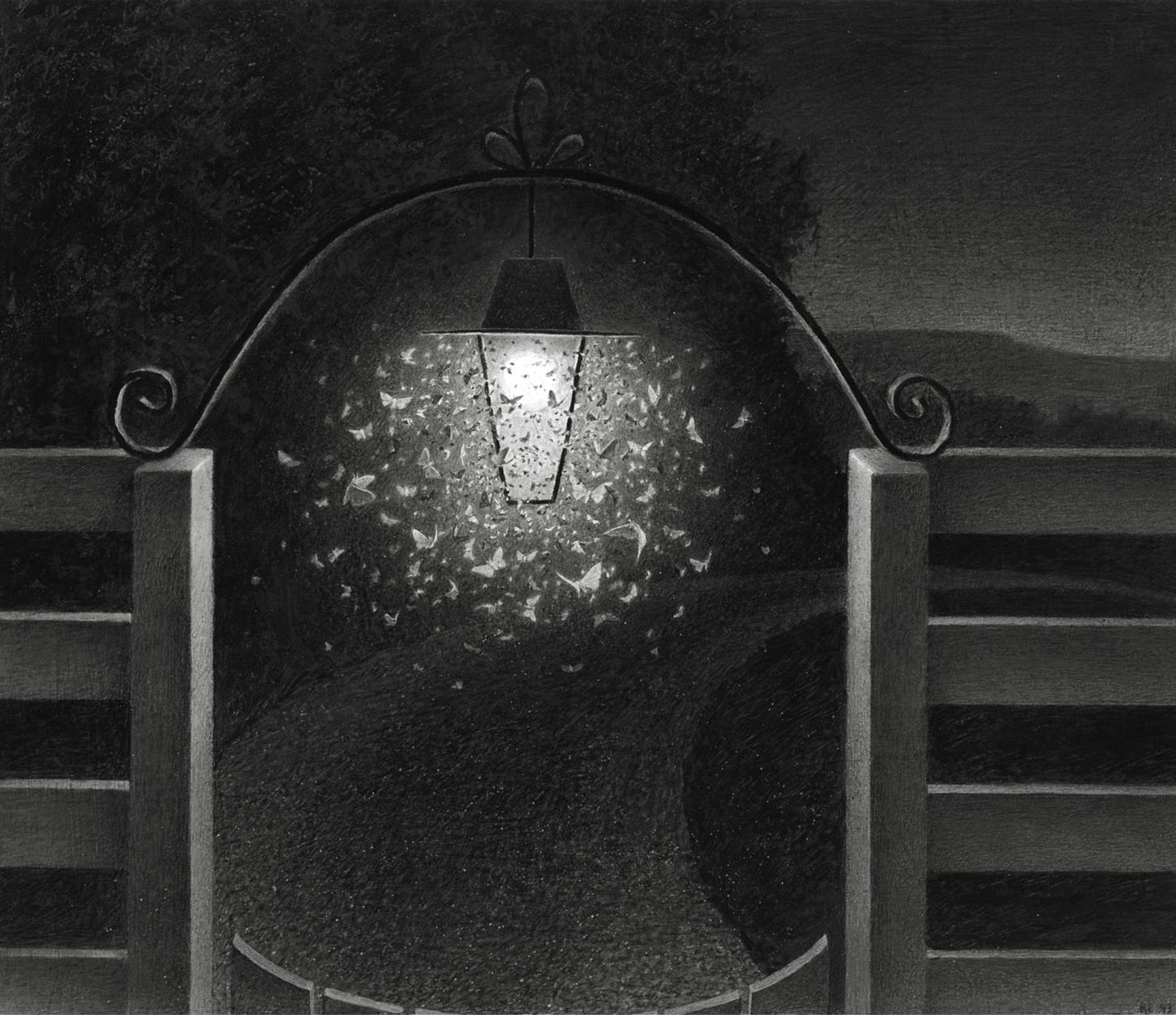

Rob Evans (who knew?)

The first of the images below kept beguiling me each few weeks when it populated blank internet tabs in Google Chrome’s Arts and Culture Extension. So I checked it out. There were plenty more beguiling images where that came from.

A feast for ears

Heaviosity half-hour

Differences in organisation across the ideological aisle

From Tanner Greer, one of the more interesting US conservatives.

The Republican and Democratic parties are not the same: power flows differently within them. … My perspective on all this has been strongly shaped by two research articles penned by political scientist Jo Freeman.1 In her youth Freeman was a new left activist, one of the founding activist-intellectuals of feminism’s second wave. She is perhaps most famous today for two essays she wrote in her activist days (both under her movement name “Joreen”). The first, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” is a biting critique of the counterculture dream of eliminating hierarchy from activist organizations. The second, “Trashing: the Dark Side of Sisterhood,” is one of the original descriptions of “Cancel Culture.” There Freeman provides a psychological account of how cancellation (she calls it “trashing”) works and the paralyzing effect it has within leftist organizations, where cancellations are most common.2 If you have never read these essays I recommend you do. Freeman’s internal critiques of left-wing movements at work are more insightful than most rightwing jeremiads against them. …

That is the mystery that drives much of Freeman’s late ‘80s work: why did the feminist movement succeed so brilliantly with the Democrats, but fail so miserably with the Republicans? Freeman argues that this had less to do with demographics or deep ideological alignment than with the structures and operational culture of each party. Although both parties have changed in the days since Freeman stalked the convention floors, many of the differences she observed between the two parties still hold true today.

The place to start is a 1980 vote on the floor of the Democratic National Convention. That year the primary feminist organizations working the convention hall were the National Woman’s Political Caucus (NWPC) and the National Organization for Women (NOW). Their pet cause was the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The Democrats had already endorsed the amendment, so NOW and the NWPC decided to up the ante: they would support a party plank that read “the Democratic Party shall offer no financial support and technical campaign assistance to candidates who do not support the ERA.” This measure, known as Minority Report #10, became the focus of their efforts.

Jimmy Carter’s delegates controlled the floor. Though no enemy to feminism, his team thought Ten was ill advised. The Democrats’ existing support for the ERA was robust, Carter balked at draconian single-issue “loyalty tests” that might erode his shaky coalition, and he did not wish to make feminist issues central to his campaign. He had the numbers to defeat this change. NOW and the NWPC understood this. Knowing full well that they could not win, the feminist groups decided to push for a floor vote anyway. The vote went just as expected. They lost the floor fight. The Democratic platform did not change.

What did this public defeat portend for the movement? Victory. Losing the fight on the floor did not set the movement back an inch. Far from it: at the next convention these same women’s organizations were given a greater share of decision making authority. All potential presidential candidates courted NOW’s endorsement months before the 1984 convention began; their preferred amendments were incorporated into the platform without issue. “Because feminists got pretty much everything they wanted prior to the Democratic Convention,” Freeman comments, “there wasn’t much to do there except celebrate.”3

This is somewhat mysterious. The feminist movement leaders sought an intentional defeat—but only gained power because of it.

We still see this story play out on the left today. Though the contest for clout has shifted out of the convention halls and out onto social media, when you look at the trajectory of leftist movements over the 2010s—such as the Black Lives Matter movement—you find a similar pattern. Protests that closed with policy defeat, changing nothing but media coverage, did not lead to the marginalization of protest leaders or their moment. Quite the opposite: with each defeat the influence these movements held over the Democratic establishment grew.

Why does this happen? Freeman argues that peculiar features of Democratic Party organization and political culture allow activists to profit from defeat. … For Freeman the most important fact about the Democratic Party is that its representative constituent groups exist in an organized form independent of the party apparatus proper. This means that the position (and to a lesser extent the power) of the men and women who lead these constituencies is not dependent on the favor of party leaders. To the contrary, Democratic Party leaders tend to think of their personal power as being dependent on the support of the constituencies the activist leaders represent.

This has two important implications. The first is that the power and career success of Democrats who either lead or strongly identify with a minority constituency “is tied to that of [their minority] group as a whole. They succeed as the group succeeds. When the group obtains more power, individuals within that group get more positions.”

Democratic leaders think of their party as a bargaining table: various groups looking for representation in the Democratic Party come to this table, demonstrate what they can do for the party, demand that the party do something for them in turn, and negotiate with competing constituencies on matters of policy and personnel. The more electorally important an identity group is, the more personnel slots it will generally receive.

The preceding paragraph is an imperfect model of actually existing Democratic politics—but it is the mental model of Democratic politics that Democratic politicians use as a reference point when evaluating the real thing. Ideals shape behavior. In this case, the ideal model makes Democratic politicians sensitive to signals of commitment and cohesion on the part of potential constituencies.

In other words: activist leaders have much to gain from making a ruckus. Every brouhaha an activist can foment shows that the constituency they claim to represent is real—and must be reckoned with. As Freeman puts it:

In the Democratic Party, keeping quiet is the cause of atrophy and speaking out is a means of access. Although the Party continues to be one of multiple power centers with multiple access points, both the type and importance of powerful groups within it has changed over time. State and local parties have weakened in the last few decades and the influence of national constituency groups has grown. The process of change has resulted in a great deal of conflict as former participants resist declining influence (e.g. the South, Chicago’s Mayor Daley) while newer ones jocky for position (women and blacks). Successfully picking fights is the primary way by which groups acquire clout within the Party.

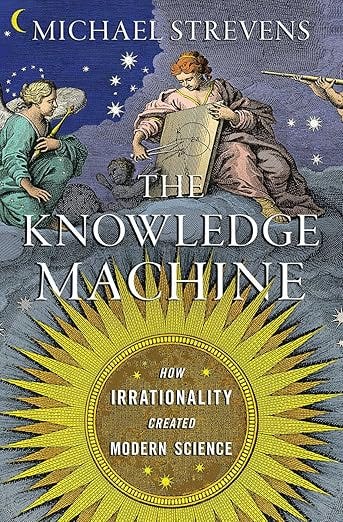

Here’s an extract from a pretty good book on the scientific method. Be that as it may, I expressed some doubts about its central argument in this comment on a review.

In the meantime, here’s a rather sympathetic cameo of Karl Popper’s views on science, what Popper was trying to achieve with them, what was good about them, and what was slightly nuts about them.

Unearthing the Scientific Method

Karl Popper’s and Thomas Kuhn’s profoundly different theories of the way science works—and the idea they share that points the way to the truthIN 1942, Karl Popper was excavating the bones of a gigantic extinct bird, the monumental moa, near Christchurch, New Zealand. A position teaching philosophy just north of Antarctica was his refuge from Hitler’s armies, which had marched into his home city of Vienna four years before.

When he was not prospecting for oversized avian remains, he was hard at work writing a condemnation of totalitarianism, in both its Nazi and communist forms, to be published at the end of the war. The twentieth century’s political and human chaos showed, Popper thought, that progress of any sort would be possible only through the vigorous exercise of the highest forms of critical thought, and for this Austrian refugee and antipodean adoptee, highest of all was scientific inquiry—perhaps the only human activity, he wrote, “in which errors are systematically criticized and fairly often, in time, corrected.” Much of his life’s work was therefore given over to an investigation of the rational basis of science, presented to the world in his philosophical masterpiece The Logic of Scientific Discovery.

The ideas in that book would change the way generations of physicists, biologists, economists, and philosophers would think about the scientific method. After Popper moved from New Zealand to take up an academic post in Britain in 1946, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, and declared by the Nobel Prize–winning biologist Sir Peter Medawar to be “incomparably the greatest philosopher of science that has ever been.”

Popper, born in 1902, turned 12 the day that Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, precipitating the Great War. He came of age in the social and economic devastation that followed. “The war years and their aftermath,” he later wrote, “were in every respect decisive for my intellectual development. They made me critical of accepted opinions, especially political opinions.” He continued:

The famine, the hunger riots in Vienna, and the runaway inflation . . . destroyed the world in which I had grown up. . . . I was over sixteen when the war ended, and the revolution incited me to stage my own private revolution. I decided to leave school, late in 1918, to study on my own. . . . There was little to eat; and as for clothing, most of us could afford only discarded army uniforms. . . . We studied; and we discussed politics.

For a few months, Popper threw in his lot with the communists, only to back away after a violent demonstration led to several protesters’ deaths—a consequence, he thought, not only of police brutality but also of the demonstrators’ tactical aggression.

He remained a socialist, however, and around 1919 resolved to take up manual work. At this time he was squatting in an abandoned wing of a former military hospital, feeding himself by tutoring American university students. The experiment with blue-collar labor turned out badly: he was, he tells us, too feeble to wield a pickaxe and too distracted by philosophical ideas to produce the straight edges and square corners required of a cabinetmaker. Abandoning these pursuits, he became a social worker, caring for neglected children. Not much later he left behind socialism itself, reasoning that while freedom and equality are both much to be desired, to have both was impossible—and in the end, “freedom is more important than equality.”

Figure 1.1. Police attempt to contain communist demonstrators in Vienna, June 1919.

In the same year, Popper heard Einstein lecture on his new theory of relativity: “I remember only that I was dazed. This thing was quite beyond my understanding.” But he was struck by Einstein’s willingness to subject his theory to empirical tests that might disprove it:

Thus I arrived, by the end of 1919, at the conclusion that the scientific attitude was the critical attitude, which did not look for verifications but for crucial tests; tests which could refute the theory tested, though they could never establish it.

In that single italicized word germinated Popper’s greatest and most influential idea.

The idea had its roots in a conundrum posed by the Edinburgh philosopher David Hume in 1739, in the first decades of the Scottish Enlightenment. Imagine Adam, mused Hume, waking in Eden for the first time—naked, alone, wholly unspoiled by knowledge of any sort. Wandering through the primeval woods, he makes some elementary discoveries: fire burns, fruit nourishes, water drowns. Or more exactly, he makes some particular observations: he burns his fingers in some particular fire; he finds some particular pieces of fruit from some particular trees nourishing; he sees some particular animal drown in some particular river. Then he generalizes, using all his newborn wit: best you avoid getting too close to any fire; best to satisfy your hunger by eating fruit from that kind of tree; and so on. This sort of generalization from experience is called inductive reasoning, or, for short, induction.

What, Hume asked, justifies these generalizations? Why is it reasonable to think that merely because this fire burned you yesterday, it will burn you again today? It’s not that Hume was recommending that you plunge your hand into the flames any time soon. He just wanted you to explain your reluctance.

There is an obvious answer to Hume’s innocent inquiry: things tend to behave the same way at all times—at least most things, most of the time. Fire will tend to affect flesh similarly, yesterday, tomorrow, and next week. So, in the absence of any other information, your best bet for predicting fire’s future effect is to generalize from the effects you’ve already seen. The practice of induction is justified, in other words, by appealing to a universal tendency to regularity or uniformity in the behavior of things. Hume considered this answer, and replied: yes, but what justifies your belief in uniformity? Why think that fire’s effects are fixed? Why think that future behavior is in general like past behavior?

There’s an obvious answer to that question, too. We think that behavior will be the same in the future as it was in the past because in our experience, it always has been the same. We justify our belief in uniformity, then, by saying that nature has always been uniform in the past, so we expect it to continue to be uniform in the future.

But that, as Hume observed, is itself a kind of inductive thinking, generalizing as it does from past to future. We are using induction to justify induction. Such circular reasoning cannot stand. The snake in the garden swallows its own tail.

There is no other route, Hume thought, by which inductive thinking might be vindicated. He was a philosophical skeptic: he believed that all those inferences that are so vital for our continued existence—what to eat, where to find it, what to pass over—are at bottom without justification. But like many skeptics, he was also a conservative: he advised us to press on with induction in our everyday lives without asking awkward philosophical questions. The English philosopher Bertrand Russell, writing about Hume two hundred years later, could not accept this philosophical quietism: if induction cannot be validated, he wrote, “there is no intellectual difference between sanity and insanity.” We will end up like the ancient Greek skeptic who, having fallen into a ditch, declined to climb out because, for all he knew, his future life in the mud would be as good as, perhaps much better than, life above ground. Or as Russell put it, our position won’t differ from that of “the lunatic who believes that he is a poached egg.”

For all that, there is still no widely accepted justification for induction. Popper saw no alternative but to accept Hume’s argument; unlike Hume, however, he concluded that we must abandon inductive thinking altogether. Science, if it is to be a rational enterprise, must not regard the fact that, say, fire has been hot enough to burn human skin in the past as a reason to think that it will be hot enough to burn skin in the future. Or to put it another way, the fact that fire has burned us in the past may not in any way be counted as “evidence for” the hypothesis that fire will be hot enough to burn us in the years to come. Indeed, science ought not to make any use whatsoever of the notion of “evidence for.” So there can be no evidence for the hypothesis that the earth orbits the sun (since that implies that the earth will in the future continue to orbit the sun); no evidence for Newton’s theory of gravitation; no evidence for the theory of evolution; no evidence in fact for anything that we’ve ever called a “theory.”

This might sound like just the sort of insanity that Russell feared. But Popper was no poached egg. Science, he thought, had a powerful replacement for the inductive thinking undermined by Hume. There may be no such thing as evidence for a theory, but what there can be—and here Popper recalled his youthful bedazzlement by Einstein in 1919—is evidence against a theory. “If the redshift of spectral lines due to the gravitational potential should not exist,” Einstein wrote of a certain phenomenon predicted by his ideas, “then [my] general theory of relativity will be untenable.” As Einstein saw, we can know for sure that any theory that makes false predictions is false. To put it another way, a true theory will always make true predictions; false predictions can issue only from falsehood. No assumptions about the uniformity of nature are needed to grasp that.

If your theory says that a comet will reappear in 76 years and it doesn’t turn up, there is something wrong with the theory. If it says that things can’t travel faster than the speed of light and it turns out that certain particles gaily skip along at far greater speeds, there is something wrong with the theory. And indeed, if your theory says you are a poached egg and you find yourself strolling the London streets on two sturdy legs far from the nearest breakfast establishment, then that theory, too, is wrong. Russell needn’t have worried. Unlike inductive thinking, this is all just straightforward, incontrovertible logic.

Such is the logic, according to Popper, that drives the scientific method. Science gathers evidence not to validate theories but to refute them—to rule them out of the running. The job of scientists is to go through the list of all possible theories and to eliminate as many as possible, or, as Popper said, to “falsify” them.

Suppose that you have accumulated much evidence and discarded many theories. Of the theories that remain on the list, it is impossible, according to Popper, to say that one is more likely to be true than any of the others: “Scientific theories, if they are not falsified, forever remain . . . conjectures.” No matter how many true predictions a theory has made, you have no more reason to believe it than to believe any of its unfalsified rivals.

Let me repeat that. Popper is sometimes said (by the New Oxford American Dictionary, for example) to have claimed that no theory can be proved definitively to be true. But he held a far more radical view than this: he thought that of the theories that have not yet been positively disproved, we have absolutely no reason to believe one rather than another. It is not that even our best theory cannot be definitively proved; it is rather that there is no such thing as a “best theory,” only a “surviving theory,” and all surviving theories are equal. Thus, in Popper’s view, there is no point in trying to gather evidence that supports one surviving theory over the others.

Scientists should consequently devote themselves to reducing the size of the pool of surviving theories by refuting as many ideas as possible. Scientific inquiry is essentially a process of disproof, and scientists are the disprovers, the debunkers, the destroyers. Popper’s logic of inquiry requires of its scientific personnel a murderous resolve. Seeing a theory, their first thought must be to understand it and then to liquidate it. Only if scientists throw themselves single-mindedly into the slaughter of every speculation will science progress.

Scientists are creators as well as destroyers: it is important that they explore the theoretical possibilities as thoroughly as they can, that they devise as many theories as they are able. But in a certain sense they create only to destroy: every new theoretical invention will be welcomed into the world by a barrage of experiments devised solely to ensure that its existence as a live option is as short as possible. There can be no favorites. Scientists must take the same attitude to the theories that they themselves concoct as to those of others, doing everything within their power to show that their own contributions to science are without any basis in fact. They are monsters who eat their own brainchildren.

It is carnage, this mass extermination of hypotheses. Yet Popper, the survivor of two world wars, thought it essential to human progress:

Let our conjectures . . . die in our stead! We may still learn to kill our theories instead of killing each other.

TO BE AN IMAGINATIVE EXPLORER of new theoretical possibilities and a ruthless critic, determined to uncover falsehood wherever it is found—that is the Popperian ideal. Scientists are both empirical warriors and intuitive artists, combining originality and openness to new ideas with an intellectual honesty that regards nothing as above suspicion.

Tough and tender, hard-eyed yet broad-minded, passionate, courageous, imaginative—who would not sit for such a self-portrait? Working scientists fell head over heels for Popper’s ideas. “There is no more to science than its method, and there is no more to its method than Popper has said,” proclaimed the cosmologist Hermann Bondi, declaring Popper the uncontested winner of the Great Method Debate. The eminent neuroscientist John Eccles wrote, “I learned from Popper what for me is the essence of scientific investigation—how to be speculative and imaginative in the creation of hypotheses, and then to challenge them with the utmost rigor.”

Popperian formulations abound not only in philosophical panegyric but also in practice, most notably in postwar Britain, where Popper made his home. In attempting to undercut the work of the neuroendocrinologist Geoffrey Harris in 1954, the anatomist Solly Zuckerman declared that a scientific hypothesis “falls to the ground the moment it is proved contrary to any of one of the facts for which it is designed to account”; he then flaunted a single ferret brain that he supposed would annihilate Harris’s career.

Popper’s contribution to the mythos of science is familiar to many scientists and science lovers. I often wonder whether they grasp, however, how peculiar a view of the logic of science lies at its core—a view on which no amount of evidence can give you more reason to believe a theory than you had when it was first formulated and completely untested; a view on which induction is a lie; a view on which you have no grounds whatsoever to think that the future will resemble the past, that the universe will go on humming the same tune rather than spontaneously changing its song.

Almost every other philosopher of science finds room for induction. Some believe that Hume’s problem must have a solution—that is, a philosophical argument showing that it is reasonable to suppose that nature is uniform in certain respects, though we may still be waiting for the thinker clever enough to unravel the Humean knot. Some believe, like Hume himself, that it has no solution but that we must go on thinking inductively regardless, both in our science and in our everyday lives. All believe that induction is essential to human existence. What made Popper different?

Perhaps there is a clue in a story told about Hans Reichenbach, a professor of philosophy in Berlin in the early 1930s. Like Popper, Reichenbach escaped to the English-speaking world as totalitarianism engulfed his Germanic homeland. Reichenbach had not thought much about Hume’s worry that the future may fail to resemble the past until 1933. In that year, the Nazis burned the Reichstag, took control of the University of Berlin, and expelled many of its Jewish professors and staff, Reichenbach included. “Then,” Reichenbach is said to have observed, “I understood at last the problem of induction.”