Rough end of the pineapple edition

And other things of interest — fine and not so fine — I found on my travels

Giving liberal democracy the rough end of the pineapple

The invariably wise Steve Randy Waldman on the disastrous Supreme Court Decision on presidential immunity. I’m genuinely surprised that none of the right wing judges didn’t take the opportunity to even pretend to themselves that they weren’t bona fide. Their judgement doesn’t even stack up against originalism. They seem to have fitted up a 21st century president with more immunity to the rule of law than their head of state (King George III) had before American revolution.

The United States is no longer a liberal democracy.

As of Monday, July 1st, 2024 and the Supreme Court's decision in Trump v. United States, the United States fails liberal democracy's most basic test. Citizens no longer have rights against the state that cannot be abrogated without due process, because presidential prerogatives are granted priority above due process and rendered immune from challenge by the courts.

The Supreme Court has legislated a loophole through the constraints on presidential power that is so large, so conveniently and readily accessible, that all notional limits to government power can be circumvented by a determined President, with almost no risk of being held accountable.

In a nutshell, the decision claims that the President has "conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority" over "commanding the Armed Forces of the United States" and "pardons for offenses against the United States".

[T]he nature of Presidential power entitles a former President to absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within his conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority.

A President, the decision pretends, remains accountable for "unofficial acts". For "official acts" beyond his "conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority", the President enjoys "at least a presumptive immunity from criminal prosecution for a President’s acts within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility."

In theory, this "presumptive immunity" can be rebutted, overcome, but

In dividing official from unofficial conduct, courts may not inquire into the President’s motives. Such a “highly intrusive” inquiry would risk exposing even the most obvious instances of official conduct to judicial examination on the mere allegation of improper purpose... Nor may courts deem an action unofficial merely because it allegedly violates a generally applicable law.

This decision is Stephen Miller, translated into legalese:

Our opponents, the media, and the whole world will soon see as we begin to take further actions that the powers of the President... are very substantial and will not be questioned. 1

Commanding the armed forces plus the pardon power, if unaccountable and unreviewable, are sufficient to impose dictatorship.

"Can't you just shoot them? Just shoot them in the legs or something?", Donald Trump asked of General and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley, when protesters gathered at the White House following the killing of George Floyd. …

From Sonia Sotomayor's dissenting opinion:

The President of the United States is the most powerful person in the country, and possibly the world. When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune. …

It's not about Donald Trump. United States Presidents are usually not of great character. It takes tremendous ambition, and a certain degree of sociopathy, to win a prize as coveted and valuable as that office. Every President must be willing to do things that the less sociopathic among us would struggle to live with. Even just and necessary military action imposes misery and death on people who do not deserve it, who bear no fault.

Donald Trump is bad. Barack Obama repudiated prohibitions against assassination that were table stakes for the "good guys" when I grew up, and simply normalized the practice. At least Obama was sufficiently chastened by risks of accountability that he had the Office of Legal Counsel perform a thorough analysis before he assassinated a US citizen. (They said it was okay.) Joe Biden has to his great credit largely ceased America's drone assassination programs.

Should we have trusted the character of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney to protect our rights? The character of Bill Clinton? Richard Nixon? A rights regime that depends upon the character of the President is not a rights regime at all. Whether it's Donald Trump on anybody else, the ring of power that the Supreme Court has forged will do its work of tempting tyranny and atrocity. There are always crises, and in crises, anything seems justified. The scandal becomes failing to exploit the tools you have at hand. …

John Roberts has always presented himself as an institutionalist. He is not an institutionalist. On Monday, John Roberts did far more damage to America's instituions than Donald Trump did on January 6. …

his Court has created a crisis. The scandal becomes failing to exploit the tools you have at hand. It is to Joe Biden's deep discredit that, when pressed for Supreme Court reform, he commissioned a study and then did nothing with it.

We are in a Wile-E-Coyote moment. The cliff has gone out from beneath our feet, but we have not yet fallen. The awful powers latent in the Supreme Court's decision have not yet been abused to crush democracy, but inevitably, inevitably, they will, if they remain as this Supreme Court has defined them.

If the possibility is not permanently foreclosed on November 5, if by the grace of God alone we get another shot, we need to pack the court ASAP, and then generate a test case under which this calamity of a decision will be overturned. Normalizing court-packing is not great, but it's the only check the other branches currently have when the Supreme Court consitutionalizes atrocity.

Once this awful decision has been relegated to history, I hope that we do restructure the Court to make it structurally less susceptible to serving as a tool for factional mischief. …

But that is all for the future. The Supreme Court set the world aflame on Monday. If you haven't noticed the heat, if you don't notice the blisters already forming on your skin very soon, then we are all going to burn.

Giving the planet the rough end: Martin Wolf

At the heart of attempts to halt damaging climate change is a pair of ideas: decarbonise electricity and electrify the economy. So, how is it going? Badly, is the answer. Will things change soon enough? Not on today’s trajectory.

Worse, the politics, always difficult, have become even more so: people just do not want to pay the price of decarbonising the economy. Here is a sobering fact: in 2023, the production of electricity generated by fossil fuels reached an all-time peak.

The share of electricity produced this way did fall, from 67 per cent in 2015 (the date of the celebrated Paris Agreement) to 61 per cent in 2023. But global output of electricity jumped 23 per cent in those eight years. As a result, even though generation from non-fossil-fuel sources (including nuclear) rose by an impressive 44 per cent, that from fossil fuels rose by 12 per cent. …

Yes, there exists a politically irrelevant “de-growth” movement. But halting growth, even if it were politically acceptable (which it is not!), would not eliminate demand for electricity. That would require us to reverse the growth of the past 150 years, instead. The only solution is faster decarbonisation and so greater investment in electricity generated by renewables, nuclear, indeed any source other than burning fossil fuels.

But we have to recognise that so far, for all the talk, emissions are not falling and so both stocks of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and global temperatures are rising.

A far more dangerous, because far more politically potent, response to this than that of “de-growthers” comes from their opposites — the free-marketeers and nationalists. This is: “Who cares? Let the fossil-fuel economy rip.” To this viewpoint a recent paper … finds that … the costs of mitigating [climate change] … are just a sixth of the costs of the likely climate change [estimated at at least 11 percent of global GDP by 2050].

Until recently, I still hoped we could be lucky: market forces (plus massive investment by China) might drive the world towards renewables fast enough. This no longer seems plausible, because the pace of the switch to renewables needs to be vastly accelerated (quite apart from the many other needed investments).

If [Brett Christophers is correct] in his book, The Price is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet … some combination of heavy carbon taxes, long-term subsidies and changes in the design of electricity markets will be needed.

Nor is this all. As Lord Nicholas Stern and Joseph Stiglitz argue in “Climate Change and Growth”, among the most important problems in this area is the failure of capital markets to price the future appropriately. Thus, the returns today’s investors seek imply that the welfare of future human beings is close to irrelevant.

This only makes sense if one can assume that the future will be fine. But what if the decisions investors are taking ensure it will not be? Then institutions — governments, evidently — must influence, if not override, those decisions. This makes the case for influencing (or setting) the cost of capital very powerful. …

An important recent paper from Bruegel, “The economic case for climate finance at scale”, makes a persuasive case for financing an accelerated exit of these countries from their reliance on coal.

A hundred years from now, people are likely to remember our era as the time when we knowingly bequeathed a destabilised climate. The market will not fix this global market failure. But today’s political fragmentation and domestic populism make it almost inconceivable that the needed courage will be forthcoming either. We talk a lot. But we find it effectively impossible to act on the needed scale. This is a tragic failure.

And many more here.

Joe and the elephant

Joe Biden has been fitting the world up with the rough end of the pineapple, but we have an even more specific term for this phenomenon — the elephant in the room. That is, the thing it is bleedingly obvious you should be thinking about when you’re busy on other things. In a recent newsletter I referred to the Keating Government’s 1991 stimulus package.

At no time did the government go through a process of deciding how big they wanted the fiscal stimulus to be.

Anyway, as a connoisseur of such things, I couldn’t help notice this comment about Joe’s performance finally becoming so bad that even those who’ve been covering up or at least smoothing over what all our lying little eyes were telling us — couldn’t deny it. It may be something else, it may be the way he overcame stuttering, but it doesn’t really matter. People really don’t want to be led by an 82 year old who seems obviously senile.

Here’s Dan Gardner:

On Saturday, Peter Baker, The New York Times reporter, noted that The Times had spoken with “dozens” of those close to the president. None indicated there had ever been serious discussions about whether Biden should run again, or how, if he did, the campaign should deal with fears that his mental faculties were in precipitous decline.

If any of the president’s advisers has ever addressed Mr. Biden’s age with him in a forthright way, they have not acknowledged it. According to recent interviews with dozens of his closest aides and friends, the president engaged in no organized process outside of his family in deciding to run for a second term.

None of the advisers described a meeting or a memo that outlined pros and cons of a re-election campaign that might have addressed the consequences of age. None said they discouraged him from running or, for that matter, discussed how to address his age if he did. Instead, he simply told them to assume he was running unless he decided otherwise.

To me, that is damning.

He goes on to explain how the Bay of Pigs invasion was similar. All understood that concealing the US Government’s role was fundamental to the plan’s success.

But there is one fact that staggers imagination.

Ten days before the invasion, a story appeared on the front page of The New York Times. The first sentence read:

For nearly nine months Cuban military forces dedicated to the overthrown of Premier Fidel Castro have been training in the United States as well as Central America.

That’s bad.

Remember, this was a plan that hinged on secrecy. Even if the rebels landed successfully and set up camps in the mountains, as planned, the whole thing would be ruined if anyone knew the US was behind it. And now it was on the front page of The New York Times.

You might think the officials in charge would say, “well, that’s it then. Tell everyone to go home.” They did not.

Britain gives itself the rough end of the pineapple

The politics of masterbation (seriously!)

The smooth end of the pineapple maybe

Matthew Crawford is a fine writer and thinker whose book The world outside your head I highly recommend. He’s also always been interested in masculinity, but I think more so since COVID. In any event, this is an amazing story. It’s also of a time and on a subject I find fascinating. Back in the cold war, the intelligence services of us freedom loving countries, and particularly the US, took culture seriously. Today it’s all PR and propaganda. They also took intellectual currents seriously, though in hindsight given what they got up to, it’s pretty clear they took them too seriously.

The connection to contemporary ‘anti-fapping’ movements in today’s manosphere may not be entirely gratuitous, but it seems a little strained. But there you go. The cold war stuff is pretty fascinating. It’s a long article, and it’s openly accessible on Unherd, so consider what I’ve reproduced below as a teaser and then head over there for the whole thing if it piques your fancy.

In the young, online manosphere, there is growing movement to refrain from masturbation … Young men have set themselves this challenge, not out of religious conviction, but from a determination to reclaim for themselves a certain degree of self-command. It is the rare appearance of ascetic practice in a society that is at once libertine and shot through with a political moralisation of sex.

The main thrust of that moralisation has been to protect women from male sexuality; here is an instance of men seeking to protect themselves. They do so on the supposition that their vital energy has been dissipated and colonised by a culture, and an industry, of pornography that is predatory and dehumanising.

One might suppose, then, that this movement would find sympathetic allies among feminists who notice a symmetry of concerns. And surely there are such feminists. But we also hear alarm, in a register typical of today’s politics: these young men are displaying disturbing fascist tendencies. …

Whatever meaning and political valence the no-fap movement has for its adepts, the journalistic Left’s ready identification of sexual self-regulation with “fascism” has a definite genealogy. Retracing this gives us a glimpse into a fascinating chapter of 20th-century social engineering, a programme of sexual “liberation” that is still with us and can feel, if not obligatory, certainly on the agenda for all who would be well-adjusted. Acquaintance with this history should disabuse us of the idea that the sexual revolution was an entirely organic eruption of cultural change, and that it happened in the Sixties. Sexual liberation was the goal of a therapeutic para-state whose organs sprang into existence almost overnight at the conclusion of the Second World War. Its political purpose was to forestall the possibility of fascism in the United States.

It would be too simple to say the sexual revolution was a government psy-op, but neither has the role of government been adequately appreciated.

… In the early Thirties, one wing of the psychoanalytic movement splintered off and became politicised under the leadership of Wilhelm Reich. Reich was convinced that fighting fascism would require a psychological transformation of the entire German population. Their susceptibility to authoritarian politics and attraction to the Fuhrer were due to the unhealthy festering of irrational forces in individual psyches, rooted ultimately in sexual “repression”. Through the efforts of Archibald MacLeish, arch-WASP literary man of the Ivy League and liberal activist, these ideas gained influence in the American security services during the war, and particular the OSS, which was planning for the reeducation of the Germans upon their defeat and subsequent military occupation. And, in fact, the US-led Allied High Commission took up this project of Freudian political therapy in its rule over the defeated Germans, which lasted until 1955.

To put the matter crudely, the Germans were going to have to start masturbating more. More seriously, the working-class family, with its sharply distinguished sex roles and ideal of a strong father, was found to be at the root of the political problem.

Reich called himself a Freudo-Marxist. The term announced a political program that would require nothing less than a moral revolution, working at the deepest level of the individual. …

The public tyranny of capitalist domination and the private tyranny of conscience form a circle of mutual support, on Reich’s view. Revolution cannot succeed unless it works ruthlessly on the psychological level. Indeed, revolution carried out on the level of economy and politics alone leads to bourgeois “defense reactions”, the most disastrous of which is fascism.

It is in the family that repressive authority is incubated and reproduced. Someone less invested in moral revolution may object that it is in the family that our faculties of moral perception develop, a gradual training of the affections whereby the child begins to apprehend an objective order of good. If all goes well, he comes to prefer virtue over vice through the mediating guidance and concern — the authority — of his parents. Reich would entirely agree, but with an opposite thrust. That is, he agrees that the moral sense is a product of authority, but insists that authority can only be repressive, never generative. It is always exercised self-interestedly, never generously for the good of another. Morality is the very thing that needs to be liquidated in the revolution.

As Philip Rieff puts Reich’s point, “A revolution must sweep out the family and its ruler, the father, no less cleanly than the old political gangs and their leaders…. The destruction, then, of the ancient mystique of fatherhood defines the revolutionary task.” …

Reich wasn’t just one more radical crank, fascinating to intellectuals but of little consequence. In fact, he was part of a larger intellectual movement that gained a substantial institutional footing in the United States in the decade immediately after Second World War.…

Immediately after the war, the War Department undertook a study to determine the causes of psychiatric breakdown in American soldiers, using interviews to probe their minds. … And what were the findings of the study? The problems of these broken soldiers were due, not to violence, but to the repression of violence, and of sexuality, typical of family life. Small town life in middle America, it turned out, was a breeding ground of precisely those unhealthy character traits that, under the right conditions, give rise to fascist movements. …

The problem with Americans was that they were latent Nazis. Presumably this came as a surprise to those soldiers who had lately placed their young bodies in the service of a national effort to defeat the Nazi regime.

In 1946, President Truman declared a mental health crisis in America, a watershed moment in the emergence of the therapeutic state. … The American government, in particular, would turn to the Freud family for guidance on how to control the enemy within, convinced that “hidden under the surface of their own population were the same dangerous forces” that had led to the death camps. The inner lives of Americans were now something that needed to be managed. Anti-fascism in the United States would be a science of social adjustment working at a deep level of the psyche, modeled on the occupation government’s parallel effort in Germany.

Immediately after the Second World War, the distrust of the people among America’s Northeastern Protestant liberals got joined to an imported version brought by European émigré intellectuals who had narrowly escaped death at the hands of a Nazi murder state that enjoyed a kind of terrifying democratic mandate, in the narrow procedural sense of winning the support of a majority in its rise to power. These émigrés were therefore understandably ill-disposed to the masses, and toward democracy in its primary sense of rule by the people.

The concerns of this politicised psychoanalytic movement got grafted onto the regime of technocratic administration that liberals had been advancing in the US for half a century. The fateful consequence, clearly visible in retrospect, is that the administrative state became the therapeutic state, with the “helping professions” serving as expert handmaidens to the new regime. Flush with victory in its first ideological war, confident in the surfeit of legitimacy that comes with victory, the government took up anti-fascism as a wider mandate of moral and social transformation.

The accompanying podcast

I listened to about half of this and then got bored, but it’s an interesting story covering much of the terrain covered by the article.

More on Nazis and the CIA — this time on psychodelics

This is a pretty interesting podcast, even though I won’t make it a regular because of the density of ads.

Felix Martin where the money is in AI

I like Felix’s drawing superforecasting into the mix with the explanation of how AI became so powerful. Rather than try to engineer into the machine what humans know, it proceeded more as if it were trying to help the machine learn things with endless usually incremental extensions of its own knowledge.

The stunning applications that have sparked the AI boom seem very different at first sight. In March 2016, Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo programme wowed the world when it beat all-time great Lee Sedol at the two-person board game. [Six] years later, OpenAI seemed to be doing something completely different again when it launched a natural language chatbot capable of ad-libbing Shakespearean verse.

Yet these landmarks all stem from the same innovation: a dramatic improvement in the accuracy of computerised predictive modelling, as AI pioneer Rich Sutton explained in a 2019 blog post. For decades, researchers trained computers to play games and solve problems by encoding hard-won human knowledge. They effectively tried to mimic our ability to reason. But these attempts were eventually bested by a far less complicated approach. Naive learning algorithms proved consistently superior when they were fuelled with sufficient computing power and fed with enough data. “Building in our discoveries” Sutton concluded, “only makes it harder to see how the discovering process can be done.”

That lesson is familiar. In the best-selling 2015 book "Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction", Canadian psychologist Philip Tetlock and his co-author Dan Gardner explained that the same agnostic method is a winner for humans too. In prediction tournaments, methodical and open-minded amateurs systematically outperform. Common sense plus the willingness to absorb a lot of data is more effective than deep domain knowledge and specialist expertise. Today’s frontier AI models essentially automate the superforecasters’ approach.

This simple recipe – learning algorithms plus computing power plus data – produces prodigious predictive results. It also provides a guide to where the long-term value in AI lies.

Start with the algorithms. The non-profit research institute EpochAI estimates that between 2012 and 2023, the computing power required to reach a set performance threshold halved approximately every eight months. Such are the cost efficiencies captured by recent innovation in neural networks.

Yet the long-term value in these algorithms is much trickier to pin down. Digital code is vulnerable to imitation and theft. The pace of future innovation is difficult to predict. The human talent currently sitting in AI labs owned by tech giants can easily walk out of the door.

The second ingredient – brute computing power – is a simpler proposition. [I]t has generated the lion’s share of the gains in the performance of AI models. … Yet …[t]he first two ingredients of AI – algorithms and compute – are worth nothing without the third: data. What is more, the better the data, the less valuable processing power becomes.

This fact has been easy to overlook. The most prominent AI applications are general-purpose chatbots which have been trained on sprawling hauls of unvetted text harvested from the web. They preferred quantity of data to quality, with computing power left to compensate. Training OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4 was estimated by Morgan Stanley to have involved at least 10,000 graphics chips crunching well over 9.5 petabytes of text. That compromise determined the result: remarkably lifelike interlocutors which are prone to incorrigible hallucinations and increasingly at risk of costly litigation for copyright infringement.

Special-purpose applications of AI have a lower profile but demonstrate where the future is more likely to lie. Nobel Prize-winning scientist Venki Ramakrishnan said Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold model solved “a fifty-year grand challenge in biology”. Just as remarkable is the fact that it required the equivalent of fewer than 200 graphics chips. That was possible because it was trained on a painstakingly curated database of 170,000 protein samples. High-quality data not only radically improves the effectiveness of AI models, but also the economics of the technology.

Companies which own useful, specialised data will be the biggest winners from AI. It’s true that richly-valued tech giants such as Alphabet owner Google and Amazon dominate some of that space too. Yet much less glamorous – and more reasonably priced – banks, utilities, healthcare providers and retailers are sitting on AI goldmines as well. Datasets, not datacentres, are where the long-term value in AI is hiding.

AI pop

Well some of the images haven’t quite made it out of uncanny valley, but most of the rest of it has. Which shows us just how prefab our culture was before AI. Still I expect it won’t be long till AI can do some interesting new Beatles numbers. And how hard can a pretty good Bach cantata be?

Mrs Hayek gets the rough end of the pineapple

This is a strange hatchet job in the Newyorker on Friedrich Hayek likening his thought to Freud’s. He had a low opinion of Freudianism. Hayek in fact wrote a book on psychology — and concluded (why am I not surprised?) that the brain was a spontaneous order of connections not unlike a market. In that he might have been more right about the brain than he was about the market. But that’s a matter of opinion. In any event, the article seems oblivious to this.

Anyway I was intrigued by the — well the intrigue. After putting the boots in by explaining how Hayek took to defending Pinochet, the article spends some time on his scheming to be rid his wife.

The great trial of Hayek’s life was his twenty-four-year marriage to Helena (Hella) Fritsch, much of which he spent trying to get out of. Caldwell and Klausinger devote the last three chapters of their biography to the divorce—and for good reason, even if they can’t see it. In Hayek’s anguished bid to end his marriage, we find, just as Freud would have anticipated, the private pathology of the public philosophy, the knowledge problem in practice. That we should discover those pathologies in a marriage is less remarkable than it might seem. From the treatises of antiquity to the novels of Jane Austen to the economics of Thomas Piketty, writers of all sorts have understood the overlap between unions of soul and contracts of need.

Before Hella, there was Lenerl—Helene Bitterlich, a distant cousin whom Hayek fell in love with after the First World War, and who shared his feelings. Sexually inexperienced and hopeless around women, Hayek didn’t make a move. Eventually, another man did, and Lenerl accepted his proposal. Hayek began seeing Hella, and they married in 1926. Within a decade, he confessed to Hella that he had married her on the rebound from Lenerl. He secretly arranged to be with Lenerl at a future point and asked Hella for a divorce. She refused the divorce and any further discussion of it.

After the Second World War, Hayek resumed his efforts. Because he intended to support Hella and their children after the divorce, he resolved to get a higher-paying job in America. For two years, he crisscrossed the Atlantic, sometimes without telling Hella the purpose of his trips. By 1948, he had an offer from the University of Chicago. When he disclosed his plan to Hella, she again refused to grant him a divorce. He had his attorney scour the country’s various divorce laws, including Reno’s. Hella, too, spoke with a lawyer, who made clear that Hayek could not divorce her without her consent.

That Hayek and Hella should have found themselves in the marital equivalent of a Hayekian market—uncertain about each other’s plans, ignorant of each other’s moves, captive to each other’s tacit knowledge—did not give him perspective or pause. Instead, he did what victims, and left-wing critics, of the market often do. In a letter to Hella, he insisted on the objective facts of the situation and asserted the rationality and right of his position. He forgot the first rule of Hayekian economics, that all data is subjective. Hella told him that if he left her, she would have a nervous breakdown, forcing him to return to take care of their children. Then she resumed her silence.

Hayek tried a different tack, drawn from another page of his economic writing. In “The Meaning of Competition,” Hayek had taken issue with the economist George Stigler’s claim that “economic relationships are never perfectly competitive if they involve any personal relationships between economic units.” Hayek countered that the corollary of imperfect knowledge in a competitive market is the trust that we must invest in other individuals, who supply us with goods and services. We depend on our personal connections—and connections to those connections—to send us to the best doctor, restaurant, or hotel. Personal networks, and the reputations that move along them, make markets work and give market actors a competitive edge.

Seeking to alter the terms of his contest with Hella, Hayek leveraged his power and connections to get a better vantage, to see further than Hella and to make the world work for him. He knew he couldn’t take the job at Chicago without resolving his divorce, but he couldn’t put Chicago off indefinitely. With his network of academic friends and private donors, he secured a temporary appointment at the university for the winter quarter of 1950. That bought him time. It also involved considerable subterfuge, toward his wife, friends, and colleagues and supervisors at the London School of Economics, who were led to believe that he would return to Britain.

To get a divorce in America, Hayek needed to establish residence in a state other than Illinois, which had restrictive divorce laws. There could be no whiff of his using the state simply to get the divorce; he’d have to get a job there and give up his appointment at L.S.E. He secured a temporary post at the University of Arkansas for the spring quarter of 1950. He arranged for his mother to move to London, if necessary, to help take care of the children and make sure Hella made no sudden moves.

“The choreography was precise,” Caldwell and Klausinger write. In the course of two days in February, while he was in America, Hayek resigned from L.S.E. and informed Hella that he was leaving her. If she wanted him to support her and the children, she had to grant him the divorce. On the advice of a lawyer, Hayek gathered more evidence of their incompatibility. He hired a handwriting expert from Vienna, who determined, from letters written by Hella and Hayek, that she was “remote from the facts of life” and he “prevails in life and knows how to master it.” In July, they were divorced. A month later, he was married to Lenerl.

The story has a final Hayekian twist. Responding to the Labour government’s drastic devaluation of the pound, Hella’s attorneys had wisely stipulated that Hayek’s alimony payments be set out in dollars. Hayek agreed, though not without sniffing that her lawyers “were interested solely in their fees.” Hayek’s L.S.E. colleague, the economist Lionel Robbins, tussled with him over whether he had got a raw deal. Robbins, once Hayek’s best friend, had sided with Hella during the divorce and become one of her close advisers. He dismissed Hayek’s complaints: “Your conception of justice is very different from mine.”

Sally Rooney’s latest, read by Sally Rooney

Great fun

I enjoyed this LRB podcast on Wilfred Owen

One thing it made me think of when Owen’s last poetry was contrasted with Rupert Brooke’s romantic war poetry was James Burnham’s statement that 9/10ths of all political discourse is just wish fulfilment. Very true also for war talk. Until the war starts. Then, all of a sudden reality intervenes. Alas, it rarely happens in politics. The moving finger having writ, moves on.

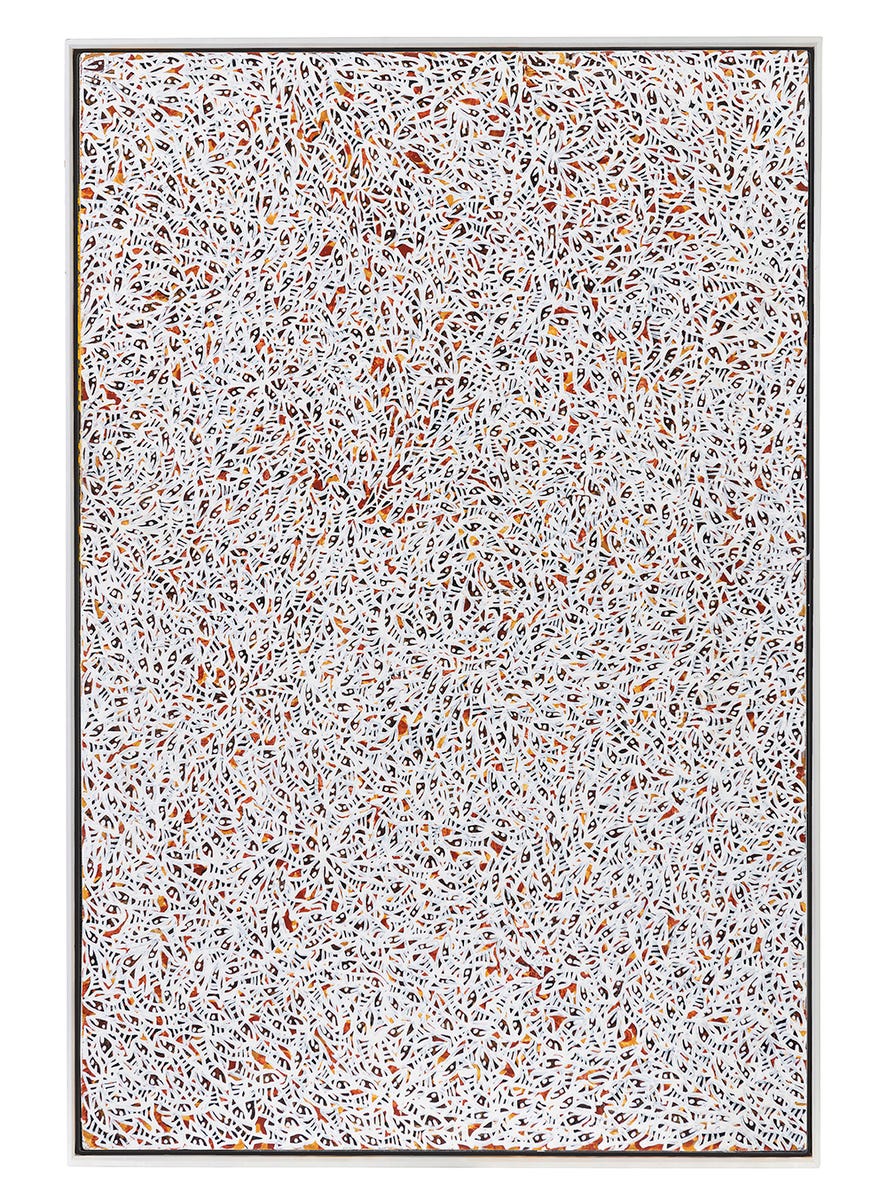

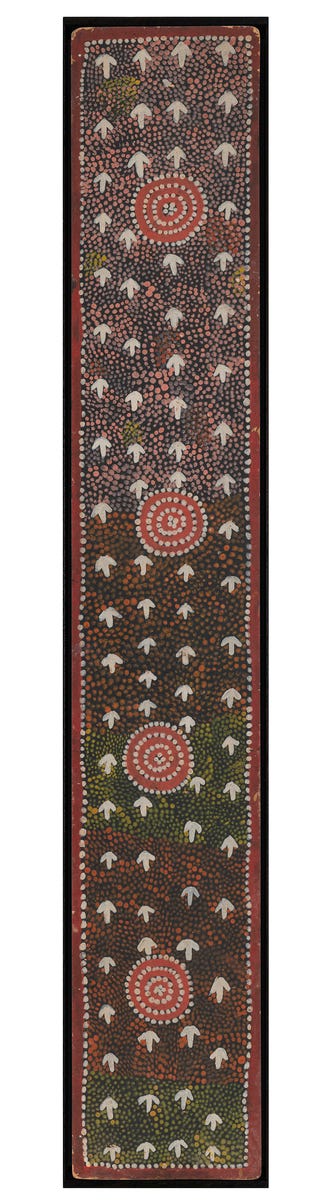

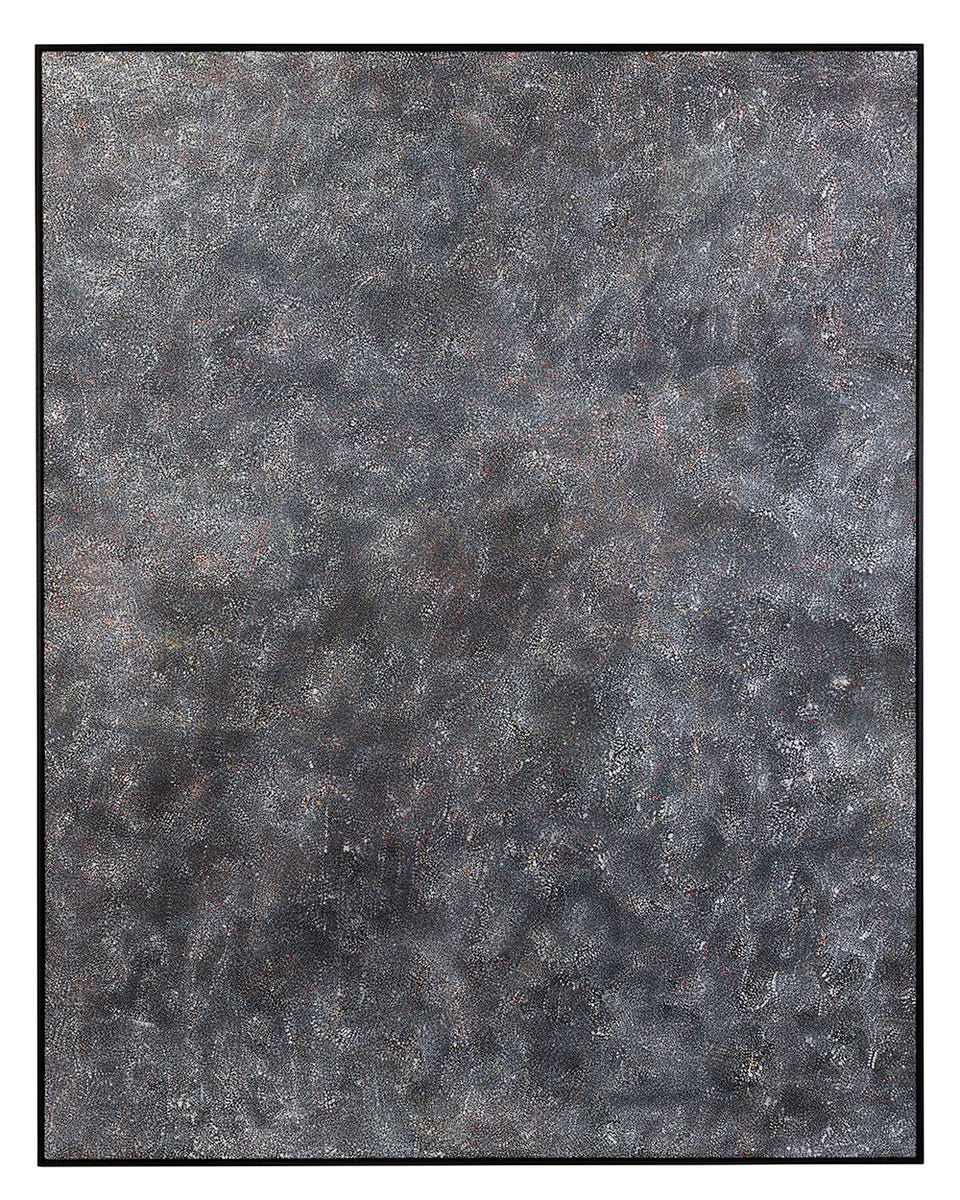

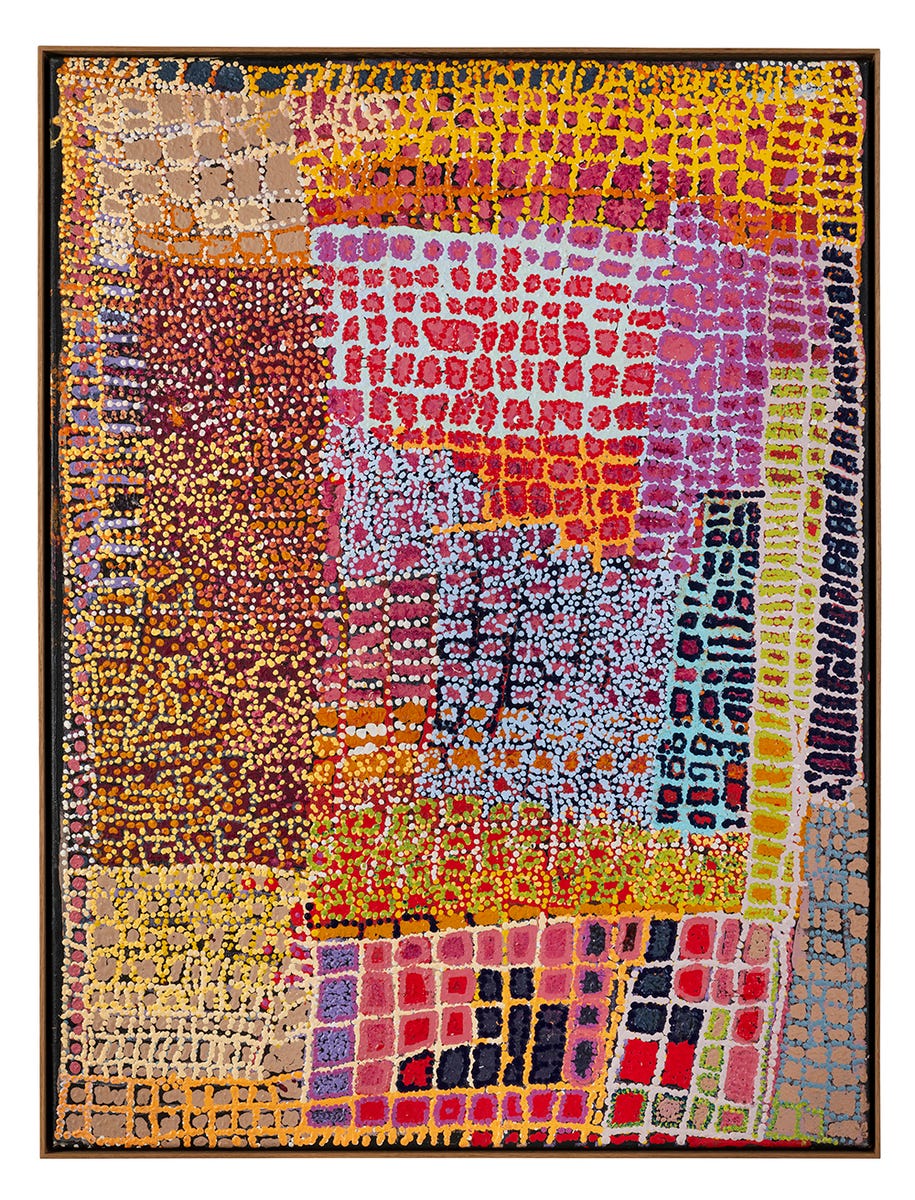

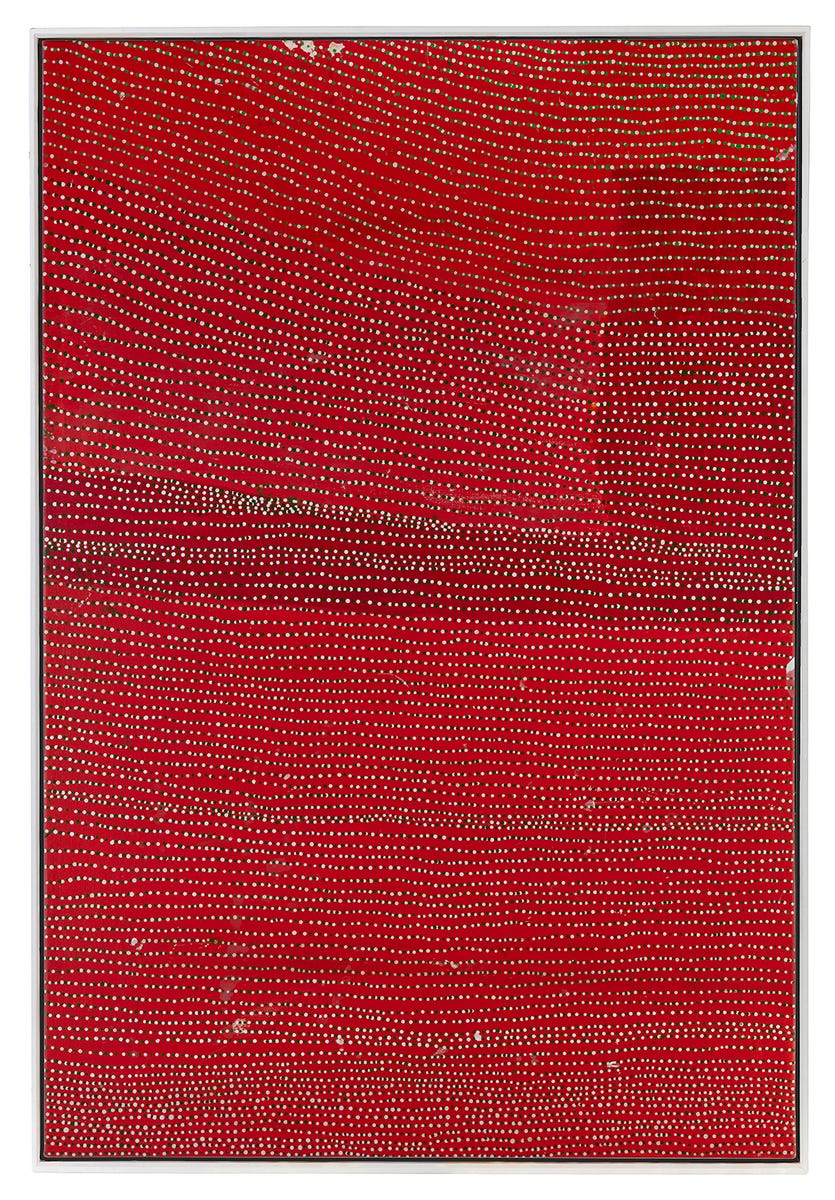

From the Significant exhibition

Details here.

Heaviosity half-hour (well maybe a minute or two)

Whitehead on the nature of scientific propositions (eg, “really, the earth goes around the sun”)

We are told by logicians that a proposition must be either true or false, and that there is no middle term. But in practice, we may know that a proposition expresses an important truth, but that it is subject to limitations and qualifications which at present remain undiscovered. It is a general feature of our knowledge, that we are insistently aware of important truths; and yet that the only formulations of these truths which we are able to make presuppose a general standpoint of conceptions which may have to be modified. I will give you two illustrations, both from science: Galileo said that the earth moves and that the sun is fixed; the Inquisition said that the earth is fixed and the sun moves; and Newtonian astronomers, adopting an absolute theory of space, said that both the sun and the earth move. But now we say that any one of these three statements is equally true, provided that you have fixed your sense of ‘rest’ and ‘motion’ in the way required by the statement adopted. At the date of Galileo’s controversy with the Inquisition, Galileo’s way of stating the facts was, beyond question, the fruitful procedure for the sake of scientific research. But in itself it was not more true than the formulation of the Inquisition. But at that time the modern concepts of relative motion were in nobody’s mind; so that the statements were made in ignorance of the qualifications required for their more perfect truth. Yet this question of the motions of the earth and the sun expresses a real fact in the universe; and all sides had got hold of important truths concerning it. But with the knowledge of those times, the truths appeared to be inconsistent.

Again I will give you another example taken from the state of modern physical science. Since the time of Newton and Huyghens in the seventeenth century there have been two theories as to the physical nature of light. Newton’s theory was that a beam of light consists of a stream of very minute particles, or corpuscles, and that we have the sensation of light when these corpuscles strike the retinas of our eyes. Huyghens’ theory was that light consists of very minute waves of trembling in an all-pervading ether, and that these waves are traveling along a beam of light. The two theories are contradictory. In the eighteenth century Newton’s theory was believed, in the nineteenth century Huyghens’ theory was believed. To-day there is one large group of phenomena which can be explained only on the wave theory, and another large group which can be explained only on the corpuscular theory. Scientists have to leave it at that, and wait for the future, in the hope of attaining some wider vision which reconciles both.

Science and the Modern World, p. 183-4 Source: Footnotes2Plato

I don't understand what your point is I'm afraid.

to be fair to the judges, I heard that this president as king was likely the case 40 years ago