Giraffes

Giraffes are not very sensible, especially from the air. But they are remarkable.

Escape from planet sensible

Stunning listening

On planet sensible everyone is ‘rational’. (Quick, let’s not dwell on what ‘rational’ means or we could be here all day!) People seek to discover and pursue what’s in their own interests. Bertrand Russell I think during his time as a conscientious objector to WWI said to Maynard Keynes that he really couldn’t take economics seriously. As he watched people gleefully march off to the slaughter of the trenches in their millions, he couldn’t take seriously a discipline that was built on the axiom that people act in their own interest.

And on planet sensible, purveyors of information purvey it and consumers consume it according to their interests. And ideologists seek to persuade audiences that they’re right and that their opponents are wrong. And, where there’s disinformation, people call for ‘fact checking’. Everyone knows that fact checking has near negligible impact on disinformation, but on planet sensible when something tricky comes up, you just keep doing what you’re doing and maybe use expressions like “innovation” and “a complexity lens” a little more.

The first time I realised I might have reached escape velocity from planet sensible was during the ‘cash for comment’ scandal in which ‘shock jocks’ Alan Jones and John Laws were outed for changing their populist tune on banks and Telstra in exchange for cash. I recall someone saying to me that they were finished from this. As I wrote on Troppo many years ago (Why is John Clarke so funny and why now?):

I never thought it would hurt their ratings. It didn’t. When I was a kid in grade 5 I used to listen to Garner Ted Armstrong, an evangelist on the radio. I had been brought up by devout atheists and I didn’t really take in what I was being told as being true or false. I liked the cadence of speech, the simplicity and predicability of the positions taken, the compelling tone. People listen to talk-back radio or at least shock jocks like that. They don’t care if its true or not. They are being entertained. But I expect that paradoxically, if things get said as obvious truisms on those shows, it produces subtle shifts in people’s views, in what is thinkable and sayable and what’s not. It becomes possible. I guess Goebbels knew this.

Anyway, I’ve liked Peter Pomerantsev since I read his excellent This is not propaganda. But I found his latest bit of historical anthropology thoroughly gripping — or at least this podcast. It is about Sefton Delmer whose unique life experience made him a perfect cross-cultural English-German go-between during WWII. Before the war he had become an uber foreign correspondent who got himself onto Hitler’s planes as he toured his dominion. He then repaired to the UK during the war. And one thing you can say about the Poms during WWII. They might have a reputation for being stuck up and stuck in the mud, but when the chips were down they turned to full on geniuses in their field and gave them a vast amount of leeway to do what they had to do. Churchill, Keynes, Turing and this guy. Sefton Delmer did deep disinformation into Nazi Germany. And he left the orbit of planet sensible.

The biggest ‘aha’ moment for me was the way in which this mid-century cultural go-between understood that the key to understanding Hitler was not just that he was pretty morose and boring except when he was being the Fuhrer giving a speech. And he was play-acting. Delmer understood that the audiences he played to were play-acting too. Hitler cast them into a role. (Come to think of it I said something slightly similar about Churchill’s speeches in this piece.)

Then his whole disinformation operation (in which people impersonated Nazis to reveal the corruption in the Nazi system) penetrated the rationality barrier. He understood that persuasion would not work. Instead his broadcasts into Nazi Germany rehearsed knowing and cynical roles Nazis could take within their system. In other words, to effect a change in the German psyche one needed Nazis to give themselves permission to change the way they saw themselves. One needed to forge for them a new role. And to do that, all that was necessary was to role play those roles. From 1943 the broadcasts did not try to hide their essentially fictitious character — that they were British propaganda. They were presenting a funnier, more engaging, more realistic and more authentic representation of German life than was done by the Germans.

Addressing the question of why the allies got the atomic bomb before the Germans, Churchill said “our Germans were better than their Germans”. Ditto Delmers

Highly recommended.

Medical Cannabis improves mental health

Coleman Drake, Dylan Nagy, Matthew D. Eisenberg, and David Slusky #32514

Abstract:

Evidence on cannabis legalization’s effects on mental health remains scarce, despite both rapid increases in cannabis use and an ongoing mental health crisis in the United States. We use granular geographic data to estimate medical cannabis dispensary availability’s effects on self-reported mental health in New York state from 2011 through 2021 using a two-stage difference-in-differences approach to minimize bias introduced from the staggered opening of dispensaries. Our findings rule out that medical cannabis availability had negative effects on mental health for the adult population overall. We also find that medical cannabis availability reduced past-month self-reported poor mental health days by nearly 10%—3.37 percentage points—among adults 65 and above. These results suggest medical cannabis access has positive health impacts for older populations, likely through pain relief.

The biggest experiment in history is still going.

Though it’s already failed

I have a fascination with the extraordinary phenomenon of government by default. It’s more striking having read Dan Davies exploration of Stafford Beer’s management cybernetics in The Unaccountability Machine because at its heart is the not very amazing idea that a competent organisation has various layers of interaction with various layers of government.

But there’s a lot of government without anyone governing about. A vast number of decisions get made on autopilot without anyone really making them. A particularly consequential example was designing the Keating Government’s stimulus rather unfortunately called One Nation in 1991. At no time did the government go through a process of deciding how big they wanted the fiscal stimulus to be. They called for new policy proposals, and went into a Budget round with Treasury and Finance trying to knock off the new proposals. Treasury and Finance were so successful that at the end of their work they discovered their stimulus was 1/4 of a percent of GDP. Then panic stricken we were all recalled to Canberra to come up with some new proposals. (They didn’t, as I recall just go back down the list and rescue some proposals that had got the chop.) Anyway, that’s how I proposed additional Family Payments and that doubled the stimulus to around 1/2 of GDP.

Anyway, all kinds of major things happen not because anyone decided to do them, but somehow they emerged in the ether. A lot of things happen this way in education and academe. What is the science behind the way universities are ranked? Well it all started with the US News and World Report needing a new angle to boost their circulation against Time and Newsweek so they released college rankings. Now there are some more indexes. Were they developed or adopted on the merits? Nope. They were adopted because the consumers of educational services want to know who’s the best — so they can go to those establishments. And there were lists available that had been cobbled together by various bodies with their own agendas. And then everyone had to do it. Today there’s a vast structure of competition even though we know the metrics are as dodgy as hell.

And, as this post makes clear, the whole idea of ‘peer review’ just kind of happened. And at least some of us who’ve seen it in action think its wastefulness is the very least of its problems. It is woeful at picking up basic errors, it imposes huge delays at substantial cost, and as this piece explains, if you look at the way academics behave rather than what they say, peer review is not taken seriously. Just one illustration of this — there are others in the piece is this. If peer review was taken seriously, rejected papers would be rewritten before resubmission to another journal — which is rare.

[S]cience has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth.

Most of those folks didn’t even realize they were in an experiment. … If we had noticed what was going on, maybe we would have demanded a basic level of scientific rigor. Maybe nobody objected because the hypothesis seemed so obviously true: science will be better off if we have someone check every paper and reject the ones that don’t pass muster. They called it “peer review.” This was a massive change. … (Only one of Einstein’s papers was ever peer-reviewed, by the way, and he was so surprised and upset that he published his paper in a different journal instead.) …

Now pretty much every journal uses outside experts to vet papers, and papers that don’t please reviewers get rejected. … This is the grand experiment we’ve been running for six decades.

The results are in. It failed. …

By one estimate, scientists collectively spend 15,000 years reviewing papers every year. … And universities fork over millions [correction: at least five billion — ed] for access to peer-reviewed journals, even though much of the research is taxpayer-funded, and none of that money goes to the authors or the reviewers. [I]f peer review improved science, that should be pretty obvious, and we should be pretty upset and embarrassed if it didn’t.

It didn’t. In all sorts of different fields, research productivity has been flat or declining for decades, and peer review doesn’t seem to have changed that trend. New ideas are failing to displace older ones. Many peer-reviewed findings don’t replicate, and most of them may be straight-up false. …

Does it catch bad research and prevent it from being published?

It doesn’t. Scientists have run studies where they deliberately add errors to papers, send them out to reviewers, and simply count how many errors the reviewers catch. Reviewers are pretty awful at this. In this study reviewers caught 30% of the major flaws, in this study they caught 25%, and in this study they caught 29%. These were critical issues, like “the paper claims to be a randomized controlled trial but it isn’t” and “when you look at the graphs, it’s pretty clear there’s no effect” and “the authors draw conclusions that are totally unsupported by the data.” Reviewers mostly didn’t notice. …

(When one editor started asking authors to add their raw data after they submitted a paper to his journal, half of them declined and retracted their submissions. This suggests, in the editor’s words, “a possibility that the raw data did not exist from the beginning.”) …

[S]cientists tacitly agree that peer review adds nothing, and they make up their minds about scientific work by looking at the methods and results. Sometimes people say the quiet part loud, like Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner:

I don’t believe in peer review because I think it’s very distorted and as I’ve said, it’s simply a regression to the mean. I think peer review is hindering science. In fact, I think it has become a completely corrupt system.

And that’s before you consider the extent to which peer review suppresses risk taking in the ideas game — one of the central reasons I’m out of academia.

I think we had the wrong model of how science works. We treated science like it’s a weak-link problem where progress depends on the quality of our worst work. If you believe in weak-link science, you think it’s very important to stamp out untrue ideas—ideally, prevent them from being published in the first place. You don’t mind if you whack a few good ideas in the process, because it’s so important to bury the bad stuff.

But science is a strong-link problem: progress depends on the quality of our best work. Better ideas don’t always triumph immediately, but they do triumph eventually, because they’re more useful. You can’t land on the moon using Aristotle’s physics, you can’t turn mud into frogs using spontaneous generation, and you can’t build bombs out of phlogiston. Newton’s laws of physics stuck around; his recipe for the Philosopher’s Stone didn’t. We didn’t need a scientific establishment to smother the wrong ideas. We needed it to let new ideas challenge old ones, and time did the rest.

Words and their meaning

I loved this exchange so much that I filmed it manually. Now it’s been released by Working Dog. A delicious presentation of how much we listen for nice words to decide whether we like something or not.

Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis

I know next to nothing about the self styled anti-populist, Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis but I know a little more now and liked what I learned.

Biden’s ICC response undermined his policy

A rules based order for thee …

While the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden is a staunch supporter of Israel, it has also expressed serious misgivings over how Israel has been carrying out its military campaign in Gaza. … Given these concerns and actions, one would have expected the Biden administration to at least offer a measured statement expressing “grave concerns” over the ruling, calling for all actors to ensure that their behavior is in line with humanitarian law and then perhaps saying that the quickest solution to the crisis is not through the courts but by the parties reaching a cease-fire.

That didn’t happen. Instead, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken issued a statement calling the ICC’s actions “shameful.” Biden echoed Blinken’s harsh reaction, labeling the arrest warrants “outrageous.” He went on to say that “whatever this prosecutor might imply, there is no equivalence—none—between Israel and Hamas.” The administration is going as far as to consider imposing sanctions against ICC officials.

The harsh response by Biden and Blinken might be disappointing to those who support the ICC’s decision. But their responses are problematic for a more fundamental reason: They undermine a core pillar of the Biden-Blinken foreign policy agenda, namely that the U.S. is the guardian of the rules-based order. Both of them commonly invoke that phrase to contrast U.S. behavior with that of Russia and China, casting those two states as revisionist powers unwilling to work within the arrangement of international institutions and legal rules established and enhanced since World War II.

[W]hen the court brought charges against Russian President Vladimir Putin last year, Blinken remarked, “I think anyone who’s a party to the court and has obligations should fulfill their obligations.” Biden himself called the ICC charges against Putin “justified,” while ordering U.S. intelligence agencies to provide evidence of Putin’s war crimes to the court. Hence, from the standpoint of the Biden administration, in bringing to light the crimes committed by Putin’s government, the ICC was showing that international law and norms matter.

Now, by dismissing outright the ICC’s charges against Israel’s leadership, Biden and Blinken have laid bare a hypocrisy born of power politics: ICC rulings are great for adversaries, but not for allies. It’s rules for thee, but not for me.

The truth is that the U.S. has a checkered history when it comes to adhering to the rules of the rules-based order. But until now, the Biden administration had at least sought to give the appearance of working within that order and had often extolled its virtues. The dismissive manner by which Biden and Blinken dismissed the ICC charges effectively undercut their efforts over the past three years to rebuild the perceived strength of international institutions following the years of neglect and disdain by the administration of former U.S. President Donald Trump. …

While the Biden administration did not need to vociferously endorse the ICC’s decision. … Biden could have simply stated that he saw the ICC’s rulings as “unhelpful.” That would not have been so inconsistent with his earlier statements on the ICC’s prosecution of Putin and therefore would not have exposed him to accusations of hypocrisy.

For someone so astute in the ways of realpolitik as Biden, his response is particularly surprising. When the staunchest supporter of a rules-based order is openly hypocritical about the application of that order’s rules, it gives up the game. Even if one gives no weight to respecting norms and the law for their own sake, Biden’s knee-jerk reaction to the ICC’s ruling against Netanyahu, someone who Biden himself has disparaged, undermines his administration’s broader strategic objectives. International law can be a tool of the strong as much as protection of the weak, and Biden just mishandled that tool.

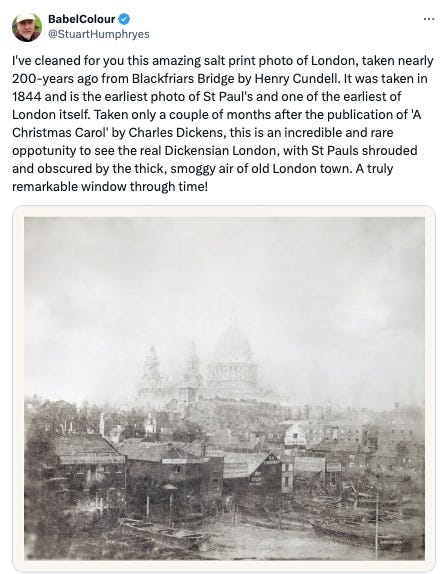

The London of the Chartists

Raymond Aron

Politically … the big question has been: Is dialogue accepted? Do people accept discussion? Here, our societies accept dialogue. The essence of the Soviet regime is its refusal of dialogue. For thirty-five years, I have chosen the society that accepts dialogue. As far as possible, this dialogue must be reasonable, but it accepts unleashed emotions, it accepts irrationality: societies of dialogue are a wager on humanity. The other regime is founded on the refusal to have confidence in those governed; founded also on the pretention of a minority of oligarchs that they possess the definitive truth for themselves and for the future. I detest that; I have fought it for thirty-five years and I will continue to do so. The pretention of those few oligarchs to possess the truth of history and of the future is intolerable.

Raymond Aron, 1983, (1997) Thinking politically: a liberal in the age of ideology.

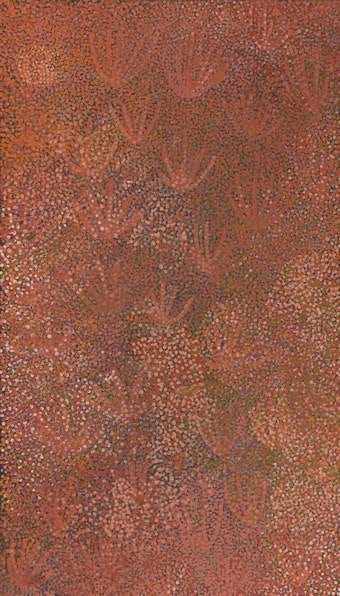

Emily Kam Kngwarray at the Tate

Rob Henderson on the new friendlessness

I read a new paper published in the journal Communications Psychology by social psychologists Lara B. Aknin and Gillian M. Sandstrom. The paper, titled “People Are Surprisingly Hesitant to Reach Out to Old Friends,” reports study results from more than 2,000 participants. More than 90 percent of the subjects said they’d lost touch with an old friend, but the majority of these subjects also said they felt neutral or negative about reaching out to them. Oddly, people reported being as willing to speak with a complete stranger or pick up garbage as they are to contact an old friend. […]

A 2019 survey found that 30 percent of millennials of both sexes said they are always or often lonely, and 27 percent said they have no close friends. Gen Z doesn’t look much different and might even be in a worse position. In her 2023 book “Generations,” the psychologist Jean Twenge points out that from the 1970s into the 2000s, teenagers spent about two hours per day with friends. By 2019, this had dropped to just one hour per day. In the 1970s, more than half of 12th graders got together with their friends almost every day. By 2019, only 28 percent did.

[…] These trends have been developing for decades. In his classic 1990 book “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience,” the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi observed: “Unfortunately, few people nowadays are able to maintain friendships into adulthood. We are too mobile, too specialized and narrow in our professional interests to cultivate enduring relationships. . . . It is a constant surprise to hear successful adults, especially men — managers of large companies, brilliant lawyers and doctors — speak about how isolated and lonely their lives have become.”

Of course, many of us still manage to invest in close relationships. And it is an investment. A widely cited study found that it takes about 50 hours of socializing to go from acquaintance to casual friendship and a total of 200 hours to become close friends. This underscores just how wasteful it is to let our friendships decay. It’s unwise to discard these investments or be reluctant to recover them, especially when the cost is a simple message and conversation every now and then.

Friends do more than just make us feel good. Research over decades suggests that it is nearly impossible to be happy without close social ties. Friendship, in fact, accounts for about 60 percent of the difference in happiness between people, even for introverts.

In their book “The Social Brain: The Psychology of Successful Groups,” the Oxford psychologist Robin Dunbar and his coauthors report that the number and quality of your friendships have a larger effect on your health than your weight, how much exercise you do, what you eat, and the quality of air you breathe. They go on to write, “By far the biggest medical surprise of the past decade has been the extraordinary number of studies showing that the single best predictor of health and wellbeing is simply the number and quality of close friendships you have.”

One 2008 study found that having a friend you see regularly delivers as much life satisfaction as an extra $150,000 a year. […] The unhappy truth is that relationship deterioration is the natural state of things unless we’re willing to do the work of maintenance.

John Cleese on taking Fawlty from good to great

Inspired dedication: it can make all the difference

If you’re working on something good, and at great effort you can make it — make the effort. Inspiring words from John Cleese.

From Antony Beevor’s Second World War

Thomas Sowell on Marx and Marxism

I got quite a lot of ‘engagement’ as they say in marketing from making this observation on the passage below. If you’re interested the discussion is here.

I’m a major non-fan of Sowell, while agreeing with plenty of his shots against his usual targets — such as this one

“The hubris of imagining that a whole society could be constructed from the ground up on the vision of one man, rather than evolving from the experience of millions, spread over the generations or centuries.”

Anyway, here are the one-liners.

Re-reading Sowell on Marx and Marxism. It begins with a thoughtful balanced overview of Marx’s philosophy and economics and then gives Sowell’s evaluation. Some great lines:

Marxism “provides a rationalisation for dismissing ideas according to their supposed origins – bourgeois, for example – instead of confronting them in either factual or logical terms.”

“Much of the intellectual legacy of Marx is an anti-intellectual legacy. It has been said that you cannot refute a sneer.”

“The Marxian vision took the overwhelming complexity of the real world and made the parts fall into place, in a way that was intellectually exhilarating and conferred such sense of moral superiority that opponents could be simply labelled and dismissed as moral lepers or blind reactionaries.”

“The Marxist constituency has remained as narrow as the conception behind it. The Communist Manifesto, written by two bright and articulate young men without responsibility even for their own livelihoods – much less for the social consequences of their vision – has had a special appeal for successive generations of the same kinds of people. The offspring of privilege have dominated the leadership of Marxist movements…”

“Intellectuals enjoy a similar insulation from the consequences of being wrong, in a way that no businessman, military leader, engineer of even athletic coach can. Intellectuals and the young have remained historically the groups most susceptible to Marxism…”

“Some of the most distinguished names in Western civilization – have become apologists for brutal dictatorships ruling in the name of Marx and committing atrocities that they would never countenance under another label. People who could never be corrupted by money or power may nevertheless be blinded by a vision.”

A thing of terrificness and coolosity

Go on, click through and play the video!

Henry Oliver on what he’s about

tl;dr. Most of us die without writing a great novel, but we can all read Anna Karenina. ….

This is a project in defiance of mediocrity. Whether or not I succeed is not the point. It is not the point at all. Non-acceptance is the animating spirit of excellence. The best thing I can do is each day to join the discussion about where excellence can be found.

My interest in academic criticism is exploitative. I want to know who came first, who invented, who bubbles at the source of the stream. As Ezra Pound said, without that knowledge you can never sort out what you know or compare the value of books.

Looking through the “Literature” leaderboard on Substack recently, I was struck by how much of it was self-help and writing advice, personal transformation and creative writing—by how much of it was not about that sort of knowledge.

I’m not against all of this. There are many fine writers doing this work. But a lot of what I saw in the “Literature” leaderboard wasn’t about literature. It was about reassurance, community, development, growth, writing, and so on.

This blog is not about any of that. You might find writing advice here, and it might help you as a writer, who knows. You will certainly find some version of self-help, though not of the usual sort. But my principal business here is to to acquire knowledge and to explicate.

I said in my essay about self-help and John Stuart Mill,

Mill’s advice is that we must keep learning, not accept what we are told, take seriously those who we disagree with, and through this process elevate our vision of life. It isn’t a joyless prescription for a puritan life. Instead, Mill is telling you to expand what you pay attention to.

… The true common reader is not the person who reads Jane Austen in the same manner that they read Agatha Christie or watch television. The true reader wants to see great work for themselves, to know what Jane Austen is in the way that the only way to know a river or a mountain is to go to it. The common reader wants to understand, not just experience.

I want to know, not just to enjoy; I believe that knowledge is a much greater form of enjoyment than uncritical reading. As Pound said, we study literature like biologists, and we go outside to learn botany by looking not at engravings but at trees.

This blog is an encouragement that you can be a literary biologist, you can learn to see literature for what it really is, to understand it better. You can learn, though immersion and critical reading, to find the living language in dead old books. You can acquire the historical knowledge and critical acumen to see the techniques of writing, to see the skull beneath the skin.

We knew not whether we were in heaven or earth

Is phone use so harmful for adolescents?

Jonathan Haidt has led the charge against social media use by adolescents and I have a lot of sympathy for his position. A lot of this critique below seems rather mealy mouthed. I’m happy to believe the author that studies don’t demonstrate causation, but those social media algorithms reek of bad, rent-seeking intentions, and the rent they extract isn’t just economic rent, but cultural rent. So while we look for better evidence, I’m good with a pretty full-on moral panic against social media impact on kids. Other mealy mouthed sentiments below are that we mustn’t panic.

But apart from the atmospherics what does she actually mean? This then draws in other arguments which, unless you get a bit panicky in your desire not to panic seem bogus; like that “Focusing solely on social media may mean that the real causes of mental disorder and distress among our children go unaddressed”. Excuse me while I remember that wearing masks against COVID might backfire by making us complacent.

My colleagues and I have repeatedly failed to find compelling support for the claim that digital-technology use is a major contributor to adolescent depression and other mental-health symptoms. …

At the end of last year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report concluding, “Available research that links social media to health shows small effects and weak associations, which may be influenced by a combination of good and bad experiences. Contrary to the current cultural narrative that social media is universally harmful to adolescents, the reality is more complicated.” …

Of course, Haidt is not alone in asserting that these apps cause such problems. Social media has been compared to heroin use in terms of its impact and has been blamed for things such as declining test scores and young people having less sex. …

The reality is that[The world would be improved by the complete eradication, no EXTERMINATION of the expression ‘the reality is that’. Ed] correlational studies to date have generated a mix of small, conflicting, and often confounded associations between social-media use and adolescents’ mental health. [See, that sentence wasn’t so bad was it?] The overwhelming majority of them offer no way to sort out cause and effect. When associations are found, things seem to work in the opposite direction from what we’ve been told: Recent research among adolescents—including among young-adolescent girls, along with a large review of 24 studies that followed people over time—suggests that early mental-health symptoms may predict later social-media use, but not the other way around. …These results do not negate the very real fears that people—including the young people that we study—have about social media, nor do they negate the reality that many young people struggle with mental-health problems. Taking a safety-first approach to kids and social media is perfectly reasonable. I certainly believe that Big Tech companies can and should be doing a lot more to design platforms with the needs and best interests of adolescents in mind. …

But the problem with the extreme position presented in Haidt’s book and in recent headlines—that digital technology use is directly causing a large-scale mental-health crisis in teenagers—is that it can stoke panic and leave us without the tools we need to actually navigate these complex issues. Two things can be true: first, that the online spaces where young people spend so much time require massive reform, and second, that social media is not rewiring our children’s brains or causing an epidemic of mental illness. Focusing solely on social media may mean that the real causes of mental disorder and distress among our children go unaddressed. …

All adolescents will eventually need to know how to safely navigate online spaces, so shutting off or restricting access to smartphones and social media is unlikely to work in the long term. In many instances, doing so could backfire: Teens will find creative ways to access these or even more unregulated spaces, and we should not give them additional reasons to feel alienated from the adults in their lives.

Heaviosity half-hour

Rethinking liberalism, the only game in town

At least compared with ‘post-liberalism’

Thanks to reader Meika for drawing my attention to this book. As you can see, it comes with some rave reviews. Thrilling books are my kind of thing. So far I’ve found it quite frustrating. The author is an academic who seems to be trying to slough off the worst depredations of the profession. Yet he’s got a fair way to go.

I couldn’t count the number of times he told me what he was about to say, what his terms were and, in particular endless rehearsals of what wasn’t saying. And, through these circumlocutions, I think he has trouble writing to his thesis rather than who he read and how he got there. I’d have stopped but for Meika’s recommendation on encountering this repetition in the second paragraph of the book.

I am not a religious man, and even so I still wasn’t prepared for what greeted us. The beach and surrounding area were packed with thousands and thousands of partyers. It was beer, bikinis, Santa hats, and tattooed flesh as far as the eye could see. As I said, I’m not religious, nor I should add prudish, but …

Still, the topic couldn’t be more important and Lefebvre really is trying to get at fundamentally important things. I started perking up when I finished reading the passage below, but I’ve not got much further, so I look forward to reading further and seeing how far our intellectual adventurer gets.

Liberalism and the Good Life

TO LAUNCH MY INVESTIGATION of how liberalism has shaped us, I begin at the beginning, with the early liberals who created the tradition in the nineteenth century. What is remarkable is that they explicitly conceived of their doctrine in relation to the question of how to live well, and specifically how to do so in light of the many social and political pressures of modern life.

In this chapter, I will not refer to John Rawls, Pierre Hadot, or the idea of society as a fair system of cooperation. That will wait until the next chapter, when I turn to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But lest I give the impression that nineteenth-century liberalism is a relic or thing of the past, I want to start this one with a contemporary figure to give it life: Leslie Knope, the hero of the television comedy Parks and Recreation (2009–15). To my mind, she is the best—the most vibrant, relevant, relatable, and just generally awesome—representative of the spirit of early liberalism.

Leslie is not the standard face of the tradition. That distinction goes to one of the great, so-called classical liberal thinkers. It is their famous portraits we tend to picture: a windswept John Locke, white-wigged Adam Smith, chiaroscuroed Immanuel Kant, or muttonchopped John Stuart Mill. But give me a chance to make my case. She belongs to this pantheon as much as any other.

The Greatest Liberal Who Never Lived

Parks and Recreation was initially conceived as a spin-off of another workplace comedy, the US adaptation of The Office (2005–13), and its cocreators Greg Daniels and Michael Schur were showrunners of that earlier series. I mention this because the first season of Parks and Recreation is in the snarkier vein of its predecessor. Set in the fictional town of Pawnee, Indiana (with the town slogan “First in Friendship, Fourth in Obesity”), the show is about a team of civil servants in the Department of Parks and Recreation. When we first meet Leslie (played by Amy Poehler), she is a thirty-four-year-old midlevel bureaucrat who is trying yet failing to take on the political system from the inside. Smart but not savvy, she is routinely ridiculed and ignored by her colleagues.

Conflict in the workplace is a tried-and-true formula for television. It makes for snappy dialogue and absurd situations. But where The Office elevated it to an art form, this formula had unintended consequences for Parks and Recreation, specifically for how Leslie was portrayed. In a retrospective on the show, Schur recalled that a test audience member for its early episodes felt that Leslie came across as a “bimbo.” That description struck a nerve. It was the opposite of how he had envisaged her as a strong, capable feminist. So the show pivoted. Rather than center on internal conflict within the office team (with Leslie as its butt), going forward its dynamic would be based on external conflict between the outside world and the office team (with Leslie as its leader).1

This changed everything. From then on, every season of Parks and Recreation revolves around a new threat to the parks, rivers, and playgrounds of Pawnee, whether from state budget cuts, the predations of the private sector, or most often, the stupidity and cynicism of its townsfolk. And every season, Leslie and her team roll up their sleeves to defend the public good with grit and verve. Almost overnight, Parks and Recreation went from being a clever yet derivative office sitcom to something else entirely. “What I felt was that the show had an argument to make about teamwork and friendship and positivity and being an optimist and believing in the power of public service,” said Schur at the ten-year cast reunion. “I don’t feel that we left anything on the table. Working on it felt like the most important thing I’ll ever do.”2

Parks and Recreation is indeed admirable and high-minded, but it is first and foremost a comedy. Leslie especially is a mix of the ridiculous and sublime. The show writers give her all the trappings for a US audience to identify her as a capital L Liberal. To mention a handful, she (inadvertently) marries two male penguins; is gifted an Obama-style “Knope” (in lieu of “Hope”) poster; writes a cookbook titled The Feminine Mesquite; claims that her ideal man would have “the brains of George Clooney inside the body of Joe Biden”; says that were she to have a stripper name, it would be Equality; and hosts an annual celebration, “Galentines’ Day,” for her female friends. For a slightly longer example, in one episode Leslie serves as a judge in the Miss Pawnee Beauty Pageant. To ensure a genuinely talented woman wins, she invents her own scorecard with the categories “teeth, interior life, knowledge of herstory, presentation, intelligence, fruitful gestures, lack of ostentation, je ne sais quoi, the Naomi Wolf factor, voice modulation.” And in case Leslie’s over-the-top liberalism hasn’t hit you yet, here is the interview question she poses to the most conventionally pretty contestant: “Alexis de Tocqueville called America the ‘great experiment.’ What can we do as citizens to improve on that experiment?”3

That is the ridiculous. But there is also the sublime. I am serious about Leslie being a singularly compelling representation of the liberal spirit. Explaining why will lead to the topic of this chapter: how liberals in the nineteenth century sought to give a modern answer to the age-old question of how to live well.

If Parks and Recreation has a political philosophy, it is about the value of the commons along with the need to keep public land, resources, and institutions free. From that core idea stems three features that make Leslie a model of early liberalism.

The first is an unstinting commitment to the public good. Early liberalism has a bad and misleading reputation in this regard. One term is largely to blame, classical liberalism, which refers to a version of liberalism that privileges individual rights, free markets, small government, and moral individualism. Whatever we may think of that package, it is important to recognize it as an anachronism when applied to the nineteenth century. Early liberals didn’t walk around referring to themselves as classical. What would that even mean given that they were busy inventing the tradition? The term was instead coined by twentieth-century economists and social theorists who worried about egalitarian and socialist tendencies in the liberalism of their own day.4 In response, they invented a term—classical liberalism—to designate what they regarded as the true core of liberalism, projected it back onto the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and then claimed themselves as its true and rightful heirs.

This is all well and good as a polemical tactic. Yet it is revisionist and historically inaccurate. Precious few early liberals would have understood themselves in the classical doctrine imputed to them. “Liberals always saw themselves as fighting for the common good and continued to see this common good in moral terms,” writes Helena Rosenblatt in her superb The Lost History of Liberalism (2018). “Today we may think that they were naive, deluded, or disingenuous. But to nineteenth-century liberals, being liberal meant believing in an ethical project.”5 To return to Parks and Recreation, many characters dismiss and deride Leslie as naive or deluded. But no one ever suggests that she is disingenuous. When we leave her in the final episode, it is with real moral and political weight that she twice cites Theodore Roosevelt’s credo, “Public service is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.” Early liberals would heartily endorse that message.

The second feature that marks Leslie as an early liberal is a love of localities. If you’ve seen Parks and Recreation, you know that over and above the many romantic pairings of its characters, the real love story is between Leslie and the town of Pawnee itself. It is a rocky relationship, to be sure. Still, all of her strivings are dedicated to ameliorating this place and making it special. Seasons 1 and 2, for example, are about transforming a giant pit into a park. Season 3 centers on reviving Pawnee’s traditional harvest festival. With each subsequent season following suit, amor mundi—care and love of the world—might as well be the show’s motto.6 That brings Leslie into the company of the great early liberals. They too were apprehensive and saddened by the tendency of the modern world to flatten difference, and make everything (including people, regions, towns, culture, opinion, language, food, sport, and art) uniform and sterile. Thus when Leslie is elected to city council in season 4 and ends her acceptance speech with “I love this city,” it comes with an implicit promise to protect it from all that threatens sameness and mediocrity. Here as well, nineteenth-century liberals would nod in agreement.

The third feature may be surprising: a suspicion of democracy, if not outright hostility toward it. Right from its plucky theme song, Parks and Recreation seems light and upbeat. Yet it has a dark and even misanthropic message: your average citizen in a modern-day democracy is either incompetent or acts in bad faith when it comes to public affairs. Perhaps the show and its writers believe in democracy and “the people” in the abstract, but its contempt for the citizens of Pawnee is boundless (and given that they created those citizens, the contempt is downright Calvinist). From the first episode to the last, Parks and Recreation never wavered. The town hall forums it features are equal parts vanity and idiocy; the elected officials it presents are clueless or venal; and the townspeople Leslie fights so hard for are always ready to trade the public good for their own worst impulses. The tension between her and the citizens of Pawnee reaches such a boiling point that when faced with the prospect of being recalled from city council, she lets rip with a speech: “I love Pawnee, but sometimes it sucks. The people can be very mean and ungrateful, and they cling to their fried dough and their big sodas, and they get mad at me when their pants don’t fit. I’m sick of it. Pawnee is filled with a bunch of pee-pee heads.”7

With its talk of pee-pee heads and big sodas, why we should take Parks and Recreation seriously? Well, this episode aired in 2013, and Leslie’s speech parodies a notorious remark by then- senator Barack Obama from five years earlier. Speaking at a fundraiser in San Francisco, he said that given the failed policies of the Clinton and Bush administrations, it is no wonder that white working-class voters “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them, or anti-immigrant sentiment, or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations .”8 Those were high-impact words. Besides Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables,” I can’t recall any that incited so much lasting resentment and solidarity with such economy. Later in the book, I will investigate whether contemporary liberalism and a contemporary liberal way of life is necessarily in tension with democracy. Was Obama’s remark just a gaffe or is there something there? It is not an issue to settle quickly or easily. Yet there can be no doubt that early liberalism was suspicious of democracy. In fact, as we will see, that was how it got its start: as a doctrine to either contain or train democracy. Like Leslie, early liberals suspected that most citizens most of the time could not be relied on to direct the polis.

Misanthropy

An abiding impression about liberals is that they tend to have a rosy, often Pollyannish view of the world. A prominent conservative once referred to himself as “a liberal who has been mugged by reality.”9 Liberals tend not to take kindly to the suggestion that they are fantasists. But given that most of them believe that people can be reasonable and rational in their dealings with others, and thus have faith in the possibility of human progress, perhaps they can recognize a grain of truth in the slight.10

Putting to the side the question of whether present-day liberals can be accused of optimism, no one would dare suggest it of their forerunners. Political theorist Judith Shklar makes this point to great effect in a masterpiece of liberal thought, Ordinary Vices (1984). Her book focuses on the early modern thinkers who inspired liberalism, especially two nobles from Bordeaux: Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) and Montesquieu (1689–1755). Shklar’s insight about these thinkers is that they are deeply misanthropic. They expect the worst from human beings, and nothing bad we do surprises them.

This is no mere psychological observation. It cuts to the heart of their philosophy, and with it, later developments in liberal thought and practice. Montesquieu is an instructive case. Shklar calls his work “misanthropy’s finest hour.”11 Why? Because when confronted with the probability that political rulers will abuse their power and inflict all manner of cruelties to secure their ends, he designed a legal and political system to minimize the damage they could do: “Misanthropy is politically a paradox. Disdain and fear could and did serve as the basis of political decency, legal restraints, and the effort to create limited government that would attenuate the effects of the cruelty of those who rule. Misanthropy can, however, also initiate slaughter.… [M]isanthropy is more significant than mere meanness of spirit.”12

Hatred of the human, Shklar makes clear, can lead to different outcomes. It can lead someone to conclude that we must put our faith in God to save us (as did Saint Augustine). It can also lead to the conviction that it would be best for the human race to let itself die out (as said Hamlet to Ophelia). It can lead another to think the present dispensation of culture is so rotten that it would be best to raze it to the ground and start over (as Friedrich Nietzsche might have felt). But it can lead a politically minded soul in quite another direction. Unlike Augustine, Montesquieu did not place his faith in an outside source. And unlike Hamlet and Nietzsche, his misanthropy was not despairing or destructive. He claims instead that what human beings need are legal and political institutions to protect the weak from the strong. Today we call his solution constitutionalism, and its doctrines of the separation of powers and rule of law are foundation stones of our own liberal democracies. Montesquieu’s misanthropy did not express itself in hopelessness or violence. He rolled up his sleeves to save humanity from its own worst impulses. He is, in this respect, a little like Leslie.

The Origins of Liberalism

Strictly speaking, Montesquieu is not a liberal. Neither is anyone living and writing prior to the nineteenth century. Historians have been firm on this point in recent years.13 The fact is that the terms liberal and liberalism were only recently used in an explicitly political sense: first in Spain in 1810, and then within a decade, across Europe and North America. From this perspective, it is acceptable to call an eighteenth-century figure such as Montesquieu a protoliberal, forerunner of liberalism, pioneer, or even influencer. But liberal, full stop? That’s a step too far.

Are the historians just being pedantic? Not at all. Their guiding premise is eminently sensible: to grasp what makes liberalism special, we need to pay attention to the context that gives rise to it. Only then can we appreciate what causes and concerns motivated early liberals. Pinpointing the origins of liberalism matters. At stake is not just when liberalism was created but also why.

To explain, let us remain a moment longer with Montesquieu. He developed his political philosophy in relation to an urgent problem of his day: royal absolutism. That problem is why his misanthropy took the form it did, namely, constitutionalism. He designed his ideas of the rule of law and separation of powers to scatter the power of any single person—whether his own fictional antihero Uzbek from Persian Letters or a real Louis XIV—who would govern through fear and threat.

Montesquieu is not alone in this endeavor. A similar story could be told about the other major forerunner of liberalism, Locke. Only a few details need amending. He too feared ambitious monarchs—“lions and tygers” such as Charles I as well as his beastly sons Charles II and James II—who would usurp powers that rightly belonged to the people. Moreover, and again like Montesquieu, Locke’s misanthropy (or if that is too harsh a word, his healthy skepticism of the great and powerful) had its own celebrated offspring: a conception of political legitimacy as based on the consent of the governed along with natural rights to life, liberty, and possessions.

Not even the most persnickety historian would deny that Montesquieu and Locke are hugely influential for the liberal tradition. On paper, they even furnish most of its main ideas, including the separation of powers, rule of law, consent of the governed, and individual rights. Furthermore, and this is Shklar’s argument, they set a mood of misanthropy for those full-fledged liberals who follow in their footsteps. Yet something essential is missing: the development of these ideas and this mood in relation to the single greatest political problem that would animate the nineteenth century. It was up to thinkers who took the name liberal to do that.

What was that problem? Ironically, the very thing that brought the world of cruel kings and bold princes crashing down: democracy. Nineteenth-century liberals of all stripes were exercised by the fact that not just political but also social, economic, moral, and cultural power would increasingly be wielded by the common man. Some, like François Guizot and Jacob Burckhardt, flatly opposed this development. Others, like Tocqueville and Mill, hoped to educate and tame it. But nineteenth-century liberals were united in repurposing, among other things, ideas and institutions originally meant to combat royal absolutism—including those I listed in connection with Montesquieu and Locke—to either restrain or guide democracy and the newfound political, social, and moral power of the people. Liberalism was their solution to the problem of democracy. That is why historians are correct to insist that liberalism is not some universal and timeless doctrine that champions freedom in the abstract. To locate its origins in any other moment in time would miss its crucial feature: a deeply conflicted attitude toward democracy.

Early liberalism’s ambivalence toward democracy is one of its most valuable features for us today. Its great authors—and I will pay special attention to Tocqueville—were extraordinary observers of modern everyday life. They knew not only that democracy was about universal suffrage and legal and political equality but that it also triggered an epochal set of social, moral, cultural, and psychological transformations. Individualism (meaning the temptation for democratic citizens to withdraw into private life and cease to care much about public affairs), materialism (meaning the temptation for democratic citizens to seek pleasure and fulfillment in small everyday gratifications), and conformity (meaning the temptation for democratic citizens to follow majority opinion without much question or fuss) are all ushered in by democracy, and have the potential to wreck our chances for happiness and self-realization. Individualism paves the way for selfishness, materialism leads to anxiety, and conformity breeds mediocrity. Those were some of the dangers early liberals confronted, and a way of life inspired by liberal ideals was their solution. Being a liberal citizen in the nineteenth century, at least for the thinkers I treat in this book, was not about trying to squash democracy or push for voter restrictions. It was an ethical project of learning to navigate modern life as best as possible.

And here is the point: I don’t know about you, but when I look at the world today, I don’t see the forces of individualism, materialism, and conformity much abated. The antidemocratism of early liberalism is thus not something we should want to periodize as the prejudices of a benighted age. Neither is it something to sanitize by saying that liberalism has today made peace with democracy and the two are now happily reconciled. Doing so would not just be historically inaccurate with respect to the nineteenth century but also practically foolish for the twenty-first. We would deny ourselves the resources that the liberal tradition invented to inhabit the democratic world.

Thanks for that last tweet, Nicholas, quite delightful.

Yes, it's hilarious!