Maybe Gallipoli wasn't such a bad idea

And other things of sufficient terrificness to be published in my newsletter

Maybe Gallipoli wasn’t all bad

I was surprised to read this ‘what if’ history of the Gallipoli campaign. Now I have to warn you that I am a Collingwood supporter, and, among many other wise words, our coach Craig McCrae says that we should not live in the “What if”. But that is now. And Gallipoli was then.

I’m way too ignorant for you to take my views on it seriously, but it seemed quite persuasive to me. Originally published in Inside Story on April 2020.

What was not recognised at the time, and is still largely forgotten, was how much had been achieved during the eight months of the campaign. The Allied landings in April 1915 were the biggest amphibious assault in the history of warfare, waged against an enemy given months of warning of the impending attack, with superior manpower and firepower and in full control of the high ground. And the lack of men and matériel that hampered the tenacious General Hamilton from the outset would never be properly rectified.

After the war, ample evidence emerged to vindicate Hamilton’s conviction that, had his army stuck it out through the bitter winter into 1916 and been adequately reinforced and resupplied, it would have broken through at Gallipoli, neutralised Turkey and helped bring the war to a much earlier conclusion. It would be revealed that twice — during the naval attack at The Narrows in March 1915 and during the August offensive — the Allies had come breathtakingly close to victory.

In 1917 German journalist Harry Stuermer, who had been based in Turkey, revealed that Turkish defences at The Narrows were at breaking point after the British and French bombardment on 18 March 1915 and, desperately short of ammunition, would have been unable to withstand a renewed attack the following day — had the naval commanders not lost their nerve after losing several warships. Ismail Enver Pasha, the Ottoman war minister, later verified the account: “If the English had only had the courage to rush more ships through the Dardanelles they could have got to Constantinople.”

Stuermer also wrote that the Turkish leadership was convinced the Allies were about to break through in August. There was panic in Constantinople and the state archives and bullion reserves had been moved to Asia Minor in the expectation that the capital was about to fall.

The decision to open a new front at Suvla Bay, north of Anzac, as part of the August push was a brilliant tactic to outflank the Turks that unravelled under the incompetent leadership of the ageing Lieutenant General Frederick Stopford, who inexplicably ordered his troops to pause and rest as soon as they had landed. It was later confirmed that Stopford’s force faced just 1500 Turks who were taken completely by surprise. The general’s prevarication gave the Turks time to reinforce and hold their ground, largely because of the initiative of Colonel Mustafa Kemal, who a decade later would emerge as president of the Turkish republic. When General William Birdwood, one of the most distinguished commanders at Gallipoli, made a return visit in 1936, the Turkish army’s chief of staff, General Fahretein Pasha, told him, “When we saw your troops landing there we were taken utterly by surprise, and we wired Constantinople advising the government to evacuate the capital as the British would be through.”

Adding value to our commodities

It’s a perennial talking point in Australia. We just dig up dirt and don’t turn it into anything. Surely we should add more value? Well, there are examples where we should, but solving these kinds of problems is the kind of thing that markets are remarkably good at doing.

Anyway, here we go again. The Government is throwing some money at adding value in green tech. This puts me in mind of some other seat-of-the-pants industry policy done by John Button way back in the mid-1980s. It involved handing over what today would be over $100 mil to a German company to retool an ailing Geelong-based textile manufacturer. It would take fine wool from the Western district and target the Italian fine textile market for export. I'm not sure it was a terrible thing to try. Why? Because if it was successful it would have built some skills and would have been imitated by others to Australia’s benefit. But it was certainly a bad idea in hindsight.

It was, from memory, a flop. The market in textiles is tricky in ways that you might expect to be hard to see from the outside — particularly at the high end where Australia’s fine wool goes. If 'everyone knows' we should be adding value to some commodity we produce, that isn't the best indication that we really should be.

In green tech, government sharing some risk in helping capital formation as it’s doing with the Clean Energy Finance Corporation seems like a good idea in principle and seems to work in practice. (In fact I suspect we should put more effort into growing small Australian greentech companies into larger ones than we do and possibly less to start-ups and very early stage capital. At least we do at least have industry super funds who seem to be doing quite a good job at growing innovative companies.)

Anyway, I’m surprised that if the government was looking for things to subsidise, it wouldn’t lean more heavily on the ideas it can take off the shelf from Ross Garnaut’s and Rod Sims’ Superpower Institute.

In the meantime, the indefatigable Bernard Keene and Glen Dyer explain why the market is actually helping us add value to our dirt in battery making, but that the smart way to do it might still be not to make that many batteries themselves.

If Labor is to be believed, only government intervention and spending billions of taxpayer dollars will enable Australia to “compete” in the new global protectionism race to build local manufacturing. But what if Australia was already competing effectively in manufacturing?

There’s iron ore magnate Twiggy Forrest’s push into green hydrogen and renewables, worth $1.14 billion (US$750 million), here and in the United States. But there are also four lithium hydroxide refineries either being built or planned: two by Albemarle, which is building two new trains at its existing Kemerton facility in Western Australia; one by IGO, which with Albemarle will use ore from the huge Greenbushes mine near Esperance; and a Wesfarmers-SQM project at Kwinana.

Lithium hydroxide, currently used in automotive manufacturing, is increasingly important in lithium battery manufacturing. There is also a lithium phosphate trial plant being built in the Pilbara by Pilbara Minerals — lithium phosphate is another key battery ingredient.

There are also two major and one smaller rare-earths processing plants built or being built, plus a couple more planned, including one near Dubbo in NSW.

BHP has major plans for copper and uranium in South Australia too. … BHP has a copper smelter at Olympic Dam and has started upgrading concentrates from the OZ Minerals sites into smelted metal (it then has to be refined into actual metal). That has a capacity of 500,000 tonnes a year, but there is talk BHP will upgrade that with a two-stage smelter that would produce around 1.7 million tonnes a year. That will also need an upgrade to the company’s electro-refinery at Olympic Dam, which will become one of the biggest manufacturing centres in the country by the early 2030s.

These expensive and high-tech production processes are crucial to the export of battery-grade materials. It makes more sense to invest in these processes — which companies already are because it’s profitable — than trying to build batteries more expensively here from scratch. …

Underlying Labor’s policies is the belief that if we produce the raw materials, we should control the entire supply chain and produce the finished product, otherwise someone else is just getting all the benefit. It’s a widely held but bizarre belief that ignores the benefits of comparative advantage for everyone, and which assumes that if we engage in protectionism, other countries won’t do exactly the same. It’s also far more expensive for taxpayers, especially when large corporations are prepared to make crucial investments themselves.

Filed under “Eclipse of the life-world”

This is a long way from a complete explanation of the phenomenon. It may be no more than a straw in the wind, but the specific claims have some truth to them, I think. And they fit a larger pattern — the gradual asphyxiation of the life world by the world of (bureaucratised) systems. (I tried to say something about that here). As Hannah Arendt put it, bureaucracy is government by no-one. In any event, here is Alan Jacobs.

I think there’s a strong causal relationship between (a) the overly structured lives of children today and (b) the silly political stunts of protestors and “activists.”

As has often been noted, American children today rarely play: they engage in planned, supervised activities completely dictated by adults. Those of us who were raised in less fearful times spent a lot of time, especially during school vacations, figuring out what to do: what games to play, what sorts of things to build, etc. To do all this, we had to learn strategies of negotiation and persuasion and give-and-take. I might agree to play the game Jerry wants to play today on the condition that we play the game I want to play tomorrow. You could of course refuse to negotiate, but then people would just stop playing with you. Over time, therefore, kids sorted these matters out: maybe one became the regular leader, maybe they took turns, maybe some kids opted out and spent more time by themselves. Some were happy about how things worked out, some less happy; there were occasionally hurt feelings and fights; some kids became the butt of jokes.

I was one of those last because I was always younger and smaller than the others. (Story of my childhood in one sentence.) That’s why I often decided to stay home and read or play with Lego. But eventually I would come back, and when I did I was, more or less, welcomed. We worked it out. It wasn’t painless, but it wasn’t The Lord of the Flies either. We came to an understanding; we negotiated our way to a functional little society of neighborhood children.

But in today’s anti-ludic world of “planned activities,” kids don’t learn those skills. In their tightly managed environments, they basically have two options: acquiescence and “acting out.” And thus when they become politically aware young adults and find themselves in situations they can’t in conscience acquiesce to, acting out is basically the only tool in their toolbox. So they bring a microphone and speaker to a dinner at someone’s house and demand that everyone listen to their speech on their pet issue. Or they blockade a bridge, thereby annoying people who probably agree with their political news and giving decision-makers good reason to condemn them. Or they dress up in American flags and storm the U. S. Capitol building. And they act out because they can’t think of anything else to do when political decisions don’t go their way. After all, they’ve been doing it all their lives.

When kids do this kind of thing, we’re not surprised; we say, hey, kids will be kids. When adults do it, we call them assholes. We raise our children in such a way – this is my thesis – that we almost guarantee that they’ll grow up to be assholes. Congratulations to us! We’ve created a world in which, pretty soon, the Politics of Assholery will be the only kind of politics there is.

Peter Singer on free speech

I’m not a fan of Cofnas’s thesis. Even if it were correct, I think acting on it could do very little good, and as its truth was confirmed it would do lots of harm. So it’s a bit like looking for some new more powerful poison. It might exist, but life is short and there are better things to do. But if academic freedom means anything it means he should be free to say it. The cultural incentives against saying what he’s saying are pretty strong anyway. The idea that saying things that are contrary to DEI dogma is a sacking offence is laughable.

Nathan Cofnas is a research fellow in the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge [and] a college research associate at Emmanuel College. Working at the intersection of science and philosophy. …

In January, Cofnas published a post called “Why We Need to Talk about the Right’s Stupidity Problem.” No one at Cambridge seems to have been bothered by his argument that people on the political right have, on average, lower intelligence than those on the left.

Some people at Cambridge were, however, very much bothered by Cofnas’s February post, “A Guide for the Hereditarian Revolution.” To follow Cofnas’s “guide,” one must accept “race realism”: the view that heredity plays a role in the existing social and economic differences between different demographic groups. Only by challenging the taboo against race realism, Cofnas believes, can conservatives overcome “wokism,” which he sees as a barrier to understanding the causes of inequality and to allowing people to succeed on the basis of merit.

If Harvard University admitted students “under a colorblind system that judged applicants only by academic qualifications,” Cofnas asserted, Black people “would make up 0.7 percent of Harvard students.” He also wrote that in a meritocracy, the number of black professors at Harvard “would approach 0 percent.”

That post gave rise to a petition from Cambridge students demanding that the university dismiss Cofnas. The petition currently has about 1,200 signatures.

On Feb. 16, the Master of Emmanuel College, Doug Chalmers, responded to the protests by saying that the college is committed to “providing an environment that is free from all discrimination.” The relevance of this comment is unclear; although there are many statements in Cofnas’s post that one can reasonably object to, it does not advocate racial discrimination. Importantly, though -- or so it seemed at the time -- Chalmers added that the college is also committed to “freedom of thought and expression,” and he acknowledged Cofnas’s “academic right, as enshrined by law, to write about his views.”

On the same day, professor Bhaskar Vira, pro-vice-chancellor for education at Cambridge, issued a brief statement that began, “Freedom of speech within the law is a right that sits at the heart of the University of Cambridge. We encourage our community to challenge ideas they disagree with and engage in rigorous debate.” He then made the obvious point that “the voice of one academic does not reflect the views of the whole university community,” adding that many staff and students “challenge the academic validity of the arguments presented.” His statement concluded by seeking to reassure students who were “understandably hurt and upset” by Cofnas’s views that “everyone at Cambridge has earned their place on merit and no one at this University should be made to feel like this.”

There was no suggestion, in the statements made by Chalmers or Vira, that either Emmanuel College or the University of Cambridge was considering dismissing Cofnas. Yet, in the face of continuing protests, both the college and the university bowed to the pressure and began their own inquiries, as did the Leverhulme Trust. The university’s inquiry and that of the Trust are, at the time of writing, ongoing, but on April 5 Cofnas received a letter notifying him that Emmanuel College had decided to terminate its association with him.

In justifying that decision, the letter informed Cofnas of the views of a committee that had been asked to consider his blog:

“The Committee first considered the meaning of the blog and concluded that it amounted to, or could reasonably be construed as amounting to, a rejection of Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion (DEI and EDI) policies. ... The Committee concluded that the core mission of the College was to achieve educational excellence and that diversity and inclusion were inseparable from that. The ideas promoted by the blog therefore represented a challenge to the College’s core values and mission.”

These sentences imply that at Emmanuel College, freedom of expression does not include the freedom to challenge its DEI policies, and that challenging them may be grounds for dismissal. That is an extraordinary statement for a tertiary institution to make. It is even more surprising given that the adoption of DEI policies is a relatively recent phenomenon.

Emmanuel College’s decision does not prevent Cofnas from continuing to hold his research fellowship in the Faculty of Philosophy. But that would cease to be the case if the university inquiry were to reach the same conclusion as the college.

The academic world will be watching what happens. Were the University of Cambridge to dismiss Cofnas, it would sound a warning to students and academics everywhere: when it comes to controversial topics, even the world’s most renowned universities can no longer be relied upon to stand by their commitment to defend freedom of thought and discussion.

Playing those DEEP notes along with your ditty

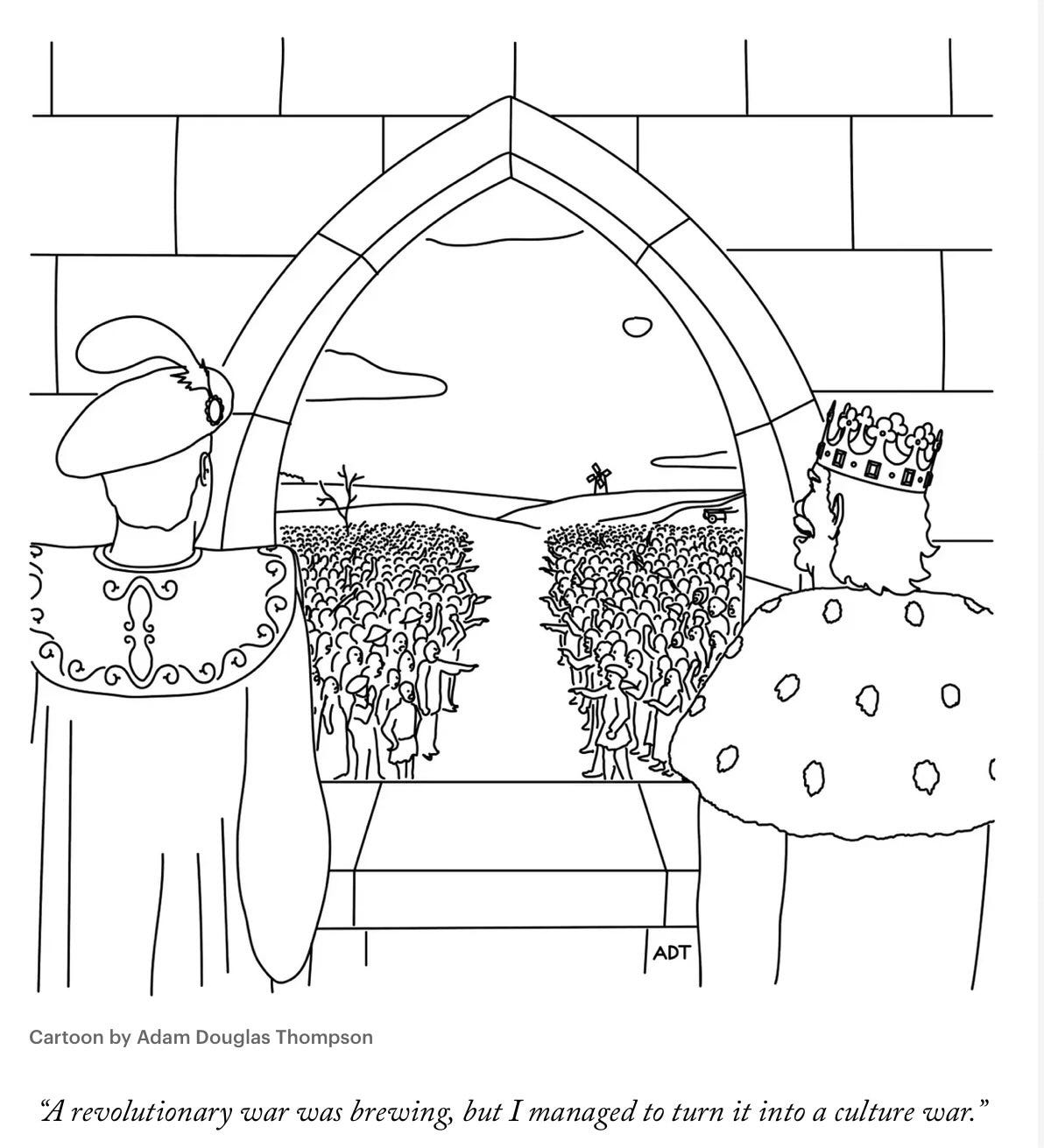

HT: Paul Krugman

Tim Harford on Moore’s and Wright’s Laws.

It is remarkable how much discussion of renewables occurs in terms of average cost reductions and not in terms of how we solve the intermittency problem (see diagram). The intermittency problem seems a lot tougher to me. (Just look at how little the purple and orange areas are! And even they present a massive underestimate of how much we’ve solved seasonal intermittency — storing months of energy is a massively bigger job than storing it for a few hours.) In the meantime, here’s a column from Tim Harford that commits this sin, but still makes for interesting reading. I’d like to have heard more about how Moore’s and Wrights Laws might apply to batteries or any other technologies that might help us tackle intermittency.

[I]n 1965, electronics engineer Gordon Moore published an article noting that the number of components that could efficiently be put on an integrated circuit was roughly doubling every year. … The question is, why? The way Moore formulated the law, it was just something that happened: the sun rises and sets, the leaves that are green turn to brown, and computers get faster and cheaper.

But there’s another way to describe technological progress, and it might be better if we talked less about Moore’s Law, and more about Wright’s Law. Theodore Wright was an aeronautical engineer who, in the 1930s, published a Moore-like observation about aeroplanes: they were getting cheaper in a predictable way. Wright found that the second of any particular model of aeroplane would be 20 per cent cheaper to make than the first, the fourth would be 20 per cent cheaper than the second, and [so on]. Wright’s Law applies to a huge range of technologies: what varies is the 20 per cent figure. Some technologies resist cost improvements. Others, such as solar photovoltaic modules, become much cheaper as production ramps up.

In a new book, Making Sense of Chaos, the complexity scientist Doyne Farmer points out that both Moore’s Law and Wright’s Law provide a good basis for forecasting the costs of different technologies. Both nicely describe the patterns that we see in the data. But which one is closer to identifying the underlying causes of these patterns? Moore’s Law suggests that products get cheaper over time, and because they are cheaper they then are demanded and produced in larger quantities. Wright’s Law suggests that rather than falling costs spurring production, it’s mass production that causes costs to fall.

And therein lies the missed opportunity. We acted as though Moore’s Law governed the cost of photovoltaics. While there were of course subsidies for solar PV in countries such as Germany, the default view was that it was too expensive to be much use as a large-scale power source, so we should wait and hope that it would eventually become cheap. If instead we had looked through the lens of Wright’s Law, governments should have been falling over themselves to buy or otherwise subsidise expensive solar PV, because the more we bought, the faster the price would fall.

… [I]f we had acted more boldly 40 years ago, solar PV might have been cheap enough to put fossil fuels out of business at the turn of the millennium. [But it wouldn’t have without solving the intermittency problem — ed.] That, of course, presupposes that Wright’s Law really does apply. It might not. Perhaps technological progress depends more on a stream of results from university research labs, and cannot be rushed — in which case, patience is the relevant virtue and a huge splurge on new technologies would be a waste of money. So — Moore’s Law, or Wright’s Law?

Sounds naïve to back moderate Palistinians

But Maggie did. And what is the alternative?

For a party that has failed to escape Thatcher’s long shadow, afflicted in its dotage with a cargo-cult weakness for matronly blondes of dubious merit, perhaps what is most remarkable is how far the current Conservative Party’s aspiring populist wing diverges from Thatcher’s own approach to the conflict. Following its invasion of Lebanon in 1982, a disaster that she correctly foresaw would birth new and harder threats to both the Western order and Israel’s own security, Thatcher placed an embargo on British weapons sales to Israel, a policy that was not lifted until 1994. Her rationale, as she told ITN, was that Israeli troops had “gone across the borders of Israel, a totally independent country, which is not a party to the hostility and there are very very great hostilities, bombing, terrible things happening there. Of course one has to condemn them. It is someone else’s country. You must condemn that. After all, that is why we have gone to the Falklands, to repossess our country which has been taken by someone else.”

A famously unsentimental woman, Thatcher framed the conflict in terms that seem strikingly empathetic to today’s eyes. In 1985, she visited an “utterly hopeless” Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan, where, as she recounts in her 1993 memoirs, The Downing Street Years, “I talked to one old lady, half blind, lying in the shade of a tree outside her family’s hut. She was said to be about 100. But she had one thing above all on her mind, and spoke about it: the restoration of the Palestinians’ rights.” For Thatcher — perhaps counterintuitively, viewed through the prism of today’s Conservative party — the “plight of the landless Palestinians” was a major foreign-policy concern. Under her helm, the British government worked hard to bring about a peace deal, though her efforts were frustrated at every turn by both Israeli and American intransigence: as she “scrawled” on one cable from the British ambassador in Washington: “The US just does not realise the resentment she is causing in the Middle East.”

Striving to find a workable peace, Thatcher asserted the only possible solution to the conflict was an approach which balanced “the right of all the states in the region — including Israel — to existence and security, but also demanded justice for all peoples, which implied recognition of of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination”. Writing of her visit to Israel in 1986, the first by a British prime minister, Thatcher remarked that “The Israelis knew… that they were dealing with someone who harboured no lurking hostility towards them, who understood their anxieties, but who was not going to pursue an unqualified Zionist approach.” Instead, she “believed that the real challenge was to strengthen moderate Palestinians, probably in association with Jordan, who would eventually push aside the… extremists. But this would never happen if Israel did not encourage it; and the miserable conditions under which Arabs on the West Bank and in Gaza were having to live only made things worse.”

The British-Jewish historian Azriel Bermant’s excellent 2016 book, Margaret Thatcher and the Middle East, makes for enlightening and perhaps discomfiting reading in the light of the Gaza War. An idealistic supporter of both Anglo-Jewry and Israel, whose own daughter Carol volunteered on a kibbutz, Thatcher nevertheless approached the country with a critical detachment. With a keener eye to Israel’s internal dynamics than Braverman or Johnson, Thatcher viewed the Right-wing Likud leaders Menachim Begin and Yitzhak Shamir with distaste, as former terrorists against the British state with whom she was forced to deal by circumstance. Her preference throughout was for the Labor leader Shimon Peres who she viewed as a moderate, committed to a lasting peace settlement. To Thatcher, peace would entail not an independent Palestinian state — she thought this unviable, and most probably undesirable — but the incorporation of the West Bank and Gaza under the rule of Jordan’s Anglophile King Hussein.

Yet when Thatcher signed on to an European Community declaration of support for Palestinian statehood, just days after the PLO confirmed its commitment to the destruction of Israel, and was condemned for this by the Labour leader Jim Callaghan — British attitudes on the conflict were yet to assume their present form — Thatcher responded in robust terms. “The words in the communiqué I support entirely,” she told the House. “They concern the right of the Palestinian people to determine their own future. If one wishes to call that ‘self- determination’, I shall not quarrel with it. I am interested that the Right Hon. Gentleman appears to be attempting to deny that right. I do not understand how anyone can demand a right for people on one side of a boundary and deny it to people on the other side of that boundary. That seems to deny certain rights, or to allocate them with discrimination from one person to another.”

Strikingly, Thatcher condemned Israel for its annexation of the Golan Heights from Syria, for its attack on Saddam Hussein’s Osirak nuclear power plant, and for its seizure of Palestinian land for settlements, including the housing of Soviet Jewish refugees: as she told the House in 1990, “Soviet Jews who leave the Soviet Union – and we have urged for years that they should be allowed to leave – should not be settled in the Occupied Territories or in East Jerusalem. It undermines our position when those people are settled in land that really belongs to others.” Indeed, as she later remarked in her memoirs, “I only wished that Israeli emphasis on the human rights of the Russian refuseniks was matched by proper appreciation of the plight of landless and stateless Palestinians.” With such sentiments, it is doubtful that today’s self-proclaimed Thatcherites would find a prominent place for Thatcher herself in their nascent faction.

Pity this kind of stuff needs to come from right-wingers.

Ineffective altruism

Lifting medical debt has little impact on Americans’ lives

It’s a neat trick. You buy up distressed medical debt, which will probably never be paid. So it’s very cheap. Some people tell you with tears in your eyes that it has changed their lives. Some of them are telling you the truth. You raise tens of millions for the cause and can claim to be relieving $11 billion in debt (even if the creditors took almost all of the hit). Everyone’s a winner. But if these researchers are doing their job properly, the ultimate effect is negligible.

Filed under “good ideas that didn’t seem to work out”. I’ve had quite a few of those myself.

Over the past decade, R.I.P. Medical Debt has grown from a tiny nonprofit group that received less than $3,000 in donations to a multimillion-dollar force in health care philanthropy.

It has done so with a unique and simple strategy to tackling the enormous amounts that Americans owe hospitals: buying up old bills that would otherwise be sold to collection agencies and wiping out the debt.

Since 2014, R.I.P. Medical Debt estimates that it has eliminated more than $11 billion of debt with the help of major donations from philanthropists and even city governments. In January, New York City’s mayor, Eric Adams, announced plans to give the organization $18 million.

But a study published by a group of economists on Monday calls into question the premise of the high-profile charity. After following 213,000 people who were in debt and randomly selecting some to work with the nonprofit group, the researchers found that debt relief did not improve the mental health or the credit scores of debtors, on average. And those whose bills had been paid were just as likely to forgo medical care as those whose bills were left unpaid.

“We were disappointed,” said Ray Kluender, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School and a co-author of the study. “We don’t want to sugarcoat it.”

Allison Sesso, R.I.P. Medical Debt’s executive director, said the study was at odds with what the group had regularly heard from those it had helped. “We’re hearing back from people who are thrilled,” she said.

Choking: it’s a no from me, but what would I know?

Intriguing essay from Mary Gaitskill who hates the idea behind the new craze and then wonders what would she know? Extracted below is the end of a long essay in the original sense of the word — essai being the french word for ‘attempt’. She’s trying to figure something out.

… I distinctly recall doing things in my youth that a month earlier I would’ve said I’d never do — and I only did some of those things once, with a particular person. It wasn’t even a question of liking or desiring that person more than others. It was about responding to him in a way that was unique to him and me, together. How can that be factored into a chart?

Which is exactly what makes it troubling that choking, rather than being accepted as something that some people like, has seemingly become something you’re expected to like or to do regardless; the sudden taste for it seems crowd-sourced, and that is not a mode that favours intimate nuance. This predicament is also very much reflected in the interviews conducted by the NLM. As one young woman said:

“… and so I fake moaned a lot when he was choking me ‘cause I felt like, ‘cause I’m also like a people pleaser. I like to make people feel happy. So I felt like I had to make him feel comfortable and everything like that… even though it’s just like during that time I was just like, oh this is new, it’s going to happen. Um, but also at the same time I’m just like, I don’t necessarily fully like this. I wish it was different.”

It is true that women have fake-moaned over all kinds of things, for millennia. It’s a perennial struggle for many people — men as well as women — to learn how to say no. But it seems different when it’s a girl feeling like she has to reassure someone who’s squeezing the bones of her throat. Reading those words online from a young woman I don’t know made me feel sad. If she were my daughter, it would break my heart. It would also make me angry without knowing quite where to direct my anger.

Then I remember: my mother would’ve been pretty sad and mad about some of the stuff I got up to if she had actually heard me talk about it. It’s probably impossible for mothers, for older people generally, not to sometimes feel that way about the stuff that much younger people get up to on their way past the acceptable and the known, especially “stuff” that looks or sounds violent. It’s easy to forget that, like the charts and the data, what you can see from the outside via interviews and articles does not reveal the inner workings, the private interplay that can happen even when people are being crude with each other. It’s easy to forget that what looks grotesque and awful on paper might feel exalted when you’re in the middle of it. And that each generation has to make its way through its own grotesque, awful and amazing experience.

From another time

Cousin Ren from the 1980s

From Vermeer in Bosnia: Selected Writings of Lawrence Weschler

In lieu of a preface:

Why I Can’t Write Fiction

Friends of mine sometimes ask me why I don’t try my hand at writing a novel. They know that novels are just about all I read, or, at any rate, all I ever talk about, and they wonder why I don’t try writing one myself. Fiction, they reason, should not be so difficult to compose if one already knows how to write nonfiction. It seems to me they ought to be right in that, and yet I can’t imagine ever being able to write fiction. This complete absence of even the fantasy of my writing fiction used to trouble me. Or not trouble me, exactly—I used to wonder at it. But I gradually came to see it as one aspect of the constellation of capacities which make it possible for me to write nonfiction. Or, rather, the other way around: the part of my sensibility which I demonstrate in nonfiction makes fiction an impossible mode for me. That’s because for me the world is already filled to bursting with interconnections, interrelationships, consequences, and consequences of consequences. The world as it is is overdetermined: the web of all those interrelationships is dense to the point of saturation. That’s what my reporting becomes about: taking any single knot and worrying out the threads, tracing the interconnections, following the mesh through into the wider, outlying mesh, establishing the proper analogies, ferreting out the false strands. If I were somehow to be forced to write a fiction about, say, a make-believe Caribbean island, I wouldn’t know where to put it, because the Caribbean as it is is already full—there’s no room in it for any fictional islands. Dropping one in there would provoke a tidal wave, and all other places would be swept away. I wouldn’t be able to invent a fictional New York housewife, because the city as it is is already overcrowded—there are no apartments available, there is no more room in the phone book. (If, by contrast, I were reporting on the life of an actual housewife, all the threads that make up her place in the city would become my subject, and I’d have no end of inspiration, no lack of room. Indeed, room—her specific space, the way the world makes room for her—would be my theme.)

It all reminds me of an exquisite notion advanced long ago by the Cabalists, the Jewish mystics, and particularly by those who subscribed to the teachings of Isaac Luria, the great, great visionary who was active in Palestine in the mid-sixteenth century. The Lurianic Cabalists were vexed by the question of how God could have created anything, since He was already everywhere and hence there could have been no room anywhere for His creation. In order to approach this mystery, they conceived the notion of tsimtsum, which means a sort of holding in of breath. Luria suggested that at the moment of creation God, in effect, breathed in—He absented Himself; or, rather, He hid Himself; or, rather, He entered into Himself—so as to make room for His creation. This tsimtsum has extraordinary implications in Lurianic and post-Lurianic teaching. In a certain sense, the tsimtsum helps account for the distance we feel from God in this fallen world. Indeed, in one version, at the moment of creation something went disastrously wrong, and the Fall was a fall for God as well as for man: God Himself is wounded; He can no longer put everything back together by Himself; He needs man. The process of salvation, of restitution—the tikkun, as Luria called it—is thus played out in the human sphere, becomes at least in part the work of men in this world. Hence, years and years later, we get Kafka’s remarkable and mysterious assertion that “the Messiah will come only when he is no longer needed; he will come only on the day after his arrival; he will come not on the last day but on the very last.”

But I digress. For me, the point here is that the creativity of the fiction writer has always seemed to partake of the mysteries of the First Creation (I realize that this is an oft-broached analogy)—the novelist as creator, his characters as his creatures. The fictionalist has to be capable of tsimtsum, of breathing in, of allowing—paradoxically, of creating—an empty space in the world, an empty time, in which his characters will be able to play out their fates. This is, I suppose, the active form of the “suspension of disbelief.” For some reason, I positively relish suspending my disbelief as long as someone else is casting the bridge across the abyss; I haven’t a clue as to how to fashion, let alone cast, such a bridge myself. …

(1985)

Leo Strauss as a moderate: an introductory appreciation

I’ve never quite been able to figure out much about Leo Strauss. There was the thing about esotericism. Sounded cool to me. Who hasn’t had the experience of needing to communicate esoterically when explicitly saying what you think invites not just trouble, but a complete misunderstanding of your motives and therefore what you think. So you communicate esoterically and those who have the nous can pick up the signals? The gay community made an art form of this throughout the years of repression — right down to having their own creole polari. They could speak in two registers, one the apparent meaning for the straight folks and one the true meaning for those who understood. Not that this was Strauss’s schtick, but who can’t appreciate that it’s sometimes necessary for people to disguise their message — to hide it between the lines of what they write? But when I read Strauss on this, I couldn’t really figure out what he was getting at. And then there are ‘Straussians’. And Peter Theil is a Strausian. And he’s not my cup of tea.

Anyway I suspect Daniel Mahoney’s and my political ideology might be fairly different too. But I’ve always appreciated his writing. And I greatly appreciated this introduction to Strauss. Mahoney writes with great passion about moderation. Good on him!

From the “grandiose failures of Marx and Nietzsche,” “the father of communism” and “the stepgrandfather of fascism,” respectively, Strauss drew this important conclusion: “wisdom cannot be separated from moderation and hence [the need] to understand that wisdom requires unhesitating loyalty to a decent constitution and even to the cause of constitutionalism.” It would be hard to surpass in eloquence or wisdom Strauss’s oft-cited remark that such moderation “will protect us against the twin dangers of visionary expectations from politics and unmanly contempt” for it. This, of course, was a classical moderation, not to be confused with the slow-motion accommodation to the zeitgeist proposed by some, then and now. Strauss wanted the liberally educated to remain committed to practical moderation and to cultivate the high-minded prudence of the responsible citizen and statesman. All of this is admirable and, in today’s context, profoundly countercultural.

When I first read Natural Right and History as a graduate student in the early 1980s, I was won over by the mixture of wisdom and spirited solicitude for Western civilization that seemed to mark the book from beginning to end. Strauss pointedly took aim at facile relativism and the thoughtless denial of natural right that were typical of the most influential currents of modern philosophy and social science. Without being openly or obviously religious, he had every confidence that reason could adjudicate between thoughtless hedonism and “spurious enthusiasms” on the one hand, and “the ways of life recommended by Amos or Socrates” on the other. He freely evoked such uplifting and ennobling categories as “eternity” and “transcendence” (even if in a more specifically philosophical idiom) and feared that the abandonment of the quest for the “best regime” and the best way of life would undermine the human capacities to cultivate the soul and “transcend the actual.” Human beings could become too at home in this world, he feared.

Strauss’s respectful but hard-hitting critique of the “fact-value” distinction articulated by the great German social scientist Max Weber allowed me as a young man to more fully appreciate how crucial discerning moral evaluation is to seeing things as they are. Such calibrated moral evaluation is integral to social science (and political philosophy), rightly understood. Among other things, Strauss brilliantly pointed out that, and how, Weber departed from his own theory: “His work would be not merely dull but absolutely meaningless if he did not speak almost constantly of practically all intellectual and moral virtues and vices in the appropriate language, i.e. in the language of praise and blame.” A striking discussion in Natural Right and History observed that “the prohibition against value judgments in social science” would allow one to speak about everything relevant to a concentration camp except the most pertinent thing: “we would not be permitted to speak of cruelty.” Such a methodologically neutered description would turn out to be an unintended, biting satire—a powerful indictment of the social science enterprise founded on it.

Heaviosity Half Hour: with Lorraine Daston

Discretion

From Rules: A Short History of What We Live By

Because discretion will figure so prominently in the history of how rules are formulated and applied, it is worth briefly pausing to examine its meaning and history. Discretion is one form of judgment, though not the whole of judgment, which embraces not only knowing when to temper the rigor of rules but also matters of taste, prudence, and insight into how the world works, including the human psyche. Although the word discretion has a Latin root, discretio, derived from the verb discerne, meaning “to divide or to distinguish,” and related to the adjective discretus, the root of the word discrete, its meanings in classical Latin hew to the literal definition.31 But in post-classical Latin, starting in the 5th or 6th century CE, discretio begins to take on the additional meanings of prudence, circumspection, and discernment in weighty matters—perhaps in connection with the biblical passage 1 Corinthians 12:10, in which Saint Paul enumerates different spiritual gifts, including that of distinguishing good from evil spirits (discretio spirituum in the fourth-century Latin translation by Saint Jerome, a phrase that was later to become important in the persecution of false prophets, heretics, and sorcerers).32 The sixth-century Rule of Saint Benedict exploits this extended range of meanings to the hilt. Once entrenched in usage, the meanings of the late Latin root discretio and its derivatives in other European languages seem to have remained remarkably constant, always associated with marking and making significant distinctions. Discretio accordingly flourished in the Latin of medieval scholastics, whose disputatious style of argument, framed in questions, objections, and replies, favored a sharp eye for subtle distinctions. For example, the index of the works of the great medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) lists at least two hundred appearances of the word, in contexts ranging from the distinction between good and evil, the hierarchy of venal and mortal sins, and kinds of tastes and smells, as well as in connection with the virtues of prudence and modesty, the judgments of the common sense (sensus communis) that integrates impressions from the various sense organs into a unified object of perception in Aristotelian psychology—and also the distinction between good and evil spirits in 1 Corinthians 12:10.33 The Lexicon philosophicum (1613), compiled by German philosopher Rudolph Goclenius the Elder (1547–1628) and a standard reference work for most of the seventeenth century, still covered much the same semantic territory four hundred years later: the primary meaning of discretio is “discrimination or distinction of one thing from another.”34

Discretio and its vernacular cognates had two sides, already evident in the abbot’s role in the Rule of Saint Benedict, the one cognitive and the other executive. To be able to distinguish between cases that differ from one another in small but crucial details is the essence of the cognitive aspect of discretion, an ability that exceeds mere analytical acuity. Discretion draws additionally upon the wisdom of experience, which teaches which distinctions make a difference in practice, not just in principle. A hypertrophy of hairsplitting is the besetting sin of scholasticism, and a mind that makes too many distinctions risks pulverizing all categories into the individuals that compose them, requiring as many rules as there are cases. In contrast, discretion preserves the classificatory scheme implied by rules—in the case of the Rule of Saint Benedict, categories such as mealtimes or work assignments—but draws meaningful distinctions within those categories—the sick monk who needs heartier nourishment; the weak monk who needs a helping hand on kitchen duty. What makes these distinctions meaningful is a combination of experience, which positions discretion in the neighborhood of prudence and other forms of practical wisdom, and certain guiding values. In the case of the Benedictine monastery these are the Christian values of compassion and charity; in the case of legal decisions, these may be values of fairness or social justice or mercy. Discretion combines intellectual and moral cognition.

But discretion goes beyond cognition. The abbot’s discernment would count for naught if he could not act upon those meaningful distinctions. The executive side of discretion, already present in the Rule of Saint Benedict, implies the freedom and power to enforce the insights of the cognitive side of discretion. Discretion is a matter of the will as well as the mind. As we shall see in Chapter 8, the willfulness of discretion had by the seventeenth century come to be tarred with the same brush as arbitrary caprice, a sign that the cognitive and executive sides of discretion had begun to split apart. The practical wisdom of those exercising power no longer commanded trust and therefore undermined the legitimacy of their prerogatives. Without its cognitive side, the executive powers of discretion became suspect. The history of the English word discretion roughly parallels this evolution. Originally imported from the Latin via French (discrecion) in the twelfth century, the meanings of discretion relating to cognitive discernment and to executive freedom coexist peacefully from at least the late fourteenth century.35 Whereas the cognitive meanings are however now listed as obsolete, the executive meanings endured—and became increasingly controversial, as every contemporary argument about the abuse of the discretionary powers of the courts, the schools, the police, or any other authority testifies. Cognitive discretion without executive discretion is impotent; executive discretion without cognitive discretion is arbitrary.

Exercising discretion in the modern sense stands opposed to following rules faithfully. In contrast, the abbot’s discretion is part of the Rule, neither contravening nor supplementing its stern imperatives. In modern jurisprudence, both Anglo-American and continental, the discretion of the judge to interpret and enforce the law is subsumed under the ancient concept of equity, often interpreted as an emergency brake to be pulled if the application of the letter of the law in a particular case would not only betray its spirit but also result in patent injustice.36 There is good reason to believe that Benedict was familiar with at least the Roman law practice of equity; he invokes “reasons of equity” to justify both greater severity and lenience in the observance of the Rule (discretion in the contexts of legal equity and moral casuistry will be addressed in Chapter 8).37 For the moment, however, it is important to flag how the abbot’s role in Benedict’s Rule exceeds that of the equitable judge in at least one crucial respect. It belongs to the wisdom of the judge to decide whether or not and how much the general law or rule should be bent to the contours of a particular case in order that justice be served. For Aristotle, who laid the cornerstone of the concept of equity (epieikeia in Greek) in the Greco-Roman tradition, the judge who exercises discretion in such cases in effect completes the work of the legislator, who cannot foresee all possible eventualities. “When therefore the law lays down a general rule, and thereafter a case arises which is an exception to the rule, it is then right, where the lawgiver’s pronouncement because of its absoluteness is defective and erroneous, when the legislator fails us and has erred by over-simplicity, to correct the omission—to rectify the defect by deciding as the lawgiver would himself decide if he were present on the occasion, and would have enacted if he were cognizant of the case in question.”38 This view still finds a home in some schools of constitutional law, which hold that it is the duty of the judge to plumb the intentions of the original framers of the Constitution and interpret its dictates accordingly.39 Comparing such adjustments to the law to the pliable leaden ruler used by the builders of island of Lesbos to measure curved solids, Aristotle attempted to correct the deficiencies of the too-general law. Aristotle’s ideal judge personifies the legislator, not the law itself. In contrast, Benedict’s ideal abbot personifies the Rule.

Even a rule curved by discretion cannot quite capture the quality of exemplification. A judge may display practical wisdom in jiggering general laws to fit particular cases but need not model the qualities of justice and rectitude in private life. Indeed, the maxim that elevates the rule of law over the rule of persons instills caution whenever rules are personalized, much less personified. Obedience to the law does not require that citizens model their conduct on that of judges and lawyers, however learned they may be in legal matters. But the monk who submitted himself to the Rule of Saint Benedict embraced the living standard of the abbot, who in turn represented Christ and was therefore addressed as “Abba, Father!” The Rule was read to novice monks at regular intervals, and its detailed precepts were to be heeded and internalized. But without the animating presence of the abbot, the Rule would have been a mere list of do’s and don’t’s, not a way of life. That punctilious obedience alone did not suffice to master the monastic way of life is indicated by the number of precepts that chastise those who obey, but without conviction: an order is to be carried out without foot-dragging, negligence, or listlessness (5.14) and above all with “no grumbling” (4.39, 23.1, 34.6, 40.8–9, 53.18). The “rule” of the Rule of Saint Benedict refers not to the detailed precepts (though these more closely resemble rules in the modern sense), nor even to precepts tempered with discretion, but to the entire document, a “rule” in the singular and a model to be emulated.

The Red Pill of History (scrub numbered footnotes)

Check out this quote.

The universal is not a real thing with a subjective existence nor in the soul nor outside the soul, it has only an objective existence in the soul and is something fictitious existing in this objective existence as the external thing exists in a subjective existence.

William of Ockham.

Notice something strange about it? Ockham is attributing solidity to the ‘subjective’ and a fantastical unreality to the ‘objective’. How things have changed. This is part of the backdrop to the story told in Daston and Galison’s 2007 book Objectivity.

Objectivity Is New

The history of scientific objectivity is surprisingly short. It first emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and in a matter of decades became established not only as a scientific norm but also as a set of practices, including the making of images for scientific atlases. How ever dominant objectivity may have become in the sciences since circa 1860, it never had, and still does not have, the epistemological field to itself. Before objectivity, there was truth-to-nature; after the advent of objectivity came trained judgment. The new did not al ways edge out the old. Some disciplines were won over quickly to the newest epistemic virtue, while others persevered in their alle giance to older ones. The relationship among epistemic virtues may be one of quiet compatibility, or it may be one of rivalry and con flict. In some cases, it is possible to pursue several simultaneously; in others, scientists must choose between truth and objectivity, or be tween objectivity and judgment. Contradictions arise.

This situation is familiar enough in the case of moral virtues. Dif ferent virtues — for example, justice and benevolence — come to be accepted as such in different historical periods. The claims of justice and benevolence can all too plausibly collide in cultures that hon or both: for Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, a man’s word is his bond; Portia replies that the quality of mercy is not strained. Codes of virtue, whether moral or epistemic, that evolve historically are loosely coherent, but not strictly internally consistent. Epistemic virtues are distinct as ideals and, more important for our argument, as historically specific ways of investigating and picturing nature. As ideals, they may more or less peacefully, if vaguely, coexist. But at the level of specific, workaday choices — which instrument to use, whether to retouch a photograph or disregard an outlying data point, how to train young scientists to see — conflicts can occur. It is not always possible to serve truth and objectivity at the same time, any more than justice and benevolence can always be reconciled in spe cific cases.

Here skeptics will break in with a chorus of objections. Isn’t the claim that objectivity is a nineteenth-century innovation tantamount to the claim that science itself begins in the nineteenth century? What about Archimedes, Andreas Vesalius, Galileo, Isaac Newton, and a host of other luminaries who worked in earlier epochs? How can there be science worthy of the name without objectivity? And how can truth and objectivity be pried apart, much less opposed to each other?

All these objections stem from an identification of objectivity with science tout court. Given the commanding place that objectivity has come to occupy in the modern manual of epistemic virtues, this conflation is perhaps not surprising. But it is imprecise, both histori cally and conceptually. Historically, it ignores the evidence of usage and use: when, exactly, did scientists start to talk about objectivity, and how did they put it to work? Conceptually, it operates by synec doche, making this or that aspect of objectivity stand for the whole, and on an ad hoc basis. The criterion may be emotional detachment in one case; automatic procedures for registering data in another; recourse to quantification in still another; belief in a bedrock reality independent of human observers in yet another. In this fashion, it is not difficult to tote up a long list of forerunners of objectivity — except that none of them operate with the concept in its entirety, to say nothing of the practices. The aim of a non-teleological history of scientific objectivity must be to show how all these elements came to be fused together (it is not self-evident, for example, what emotional detachment has to do with automatic data registration), designated by a single word, and translated into specific scientific techniques. Moreover, isolated instances are of little interest. We want to know when objectivity became ubiquitous and irresistible.

The evidence for the nineteenth-century novelty of scientific objectivity starts with the word itself. The word “objectivity” has a somersault history. Its cognates in European languages derive from the Latin adverbial or adjectival form obiectivus/obiective, introduced by fourteenth-century scholastic philosophers such as Duns Scotus and William of Ockham. (The substantive form does not emerge until much later, around the turn of the nineteenth century.) From the very beginning, it was always paired with subiectivus/subiective, but the terms originally meant almost precisely the opposite of what they mean today. “Objective” referred to things as they are pre sented to consciousness, whereas “subjective” referred to things in themselves.6 One can still find traces of this scholastic usage in those passages of the Meditationes de prima philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy, 1641) where Rene Descartes contrasts the “formal real ity” of our ideas (that is, whether they correspond to anything in the external world) with their “objective reality” (that is, the degree of reality they enjoy by virtue of their clarity and distinctness, regard less of whether they exist in material form). Even eighteenth-cen tury dictionaries still preserved echoes of this medieval usage, which rings so bizarrely in modern ears: “Hence a thing is said to exist OBJECTIVELY, objective, when it exists no otherwise than in being known; or in being an Object of the Mind.”

The words objective and subjective fell into disuse during the sev enteenth and eighteenth centuries and were invoked only occasion ally, as technical terms, by metaphysicians and logicians. It was Immanuel Kant who dusted off the musty scholastic terminology of “objective” and “subjective” and breathed new life and new meanings into it. But the Kantian meanings were the grandparents, not the twins, of our familiar senses of those words. Kant’s “objec tive validity” (objektive Gilltigkeit) referred not to external objects ('Gegenstande) but to the “forms of sensibility” (time, space, causal ity) that are the preconditions of experience. And his habit of using “subjective” as a rough synonym for “merely empirical sensations” shares with later usage only the sneer with which the word is in toned. For Kant, the line between the objective and the subjective generally runs between universal and particular, not between world and mind.

Yet it was the reception of Kantian philosophy, often refracted through other traditions, that revamped terminology of the objective and subjective in the early nineteenth century. In Germany, idealist philosophers such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling turned Kant’s distinctions to their own ends; in Britain, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who had scant German but grand ambitions, presented the new philosophy to his countrymen as a continuation of Francis Bacon; in France, the philosopher Victor Cousin grafted Kant onto Descartes. The post-Kantian usage was so new that some readers thought at first it was just a mistake. Coleridge scribbled in his copy of Henrich Steffens’s Grundzuge der philosophischen Naturwissenschaft (Foundations of Philosophical Nat ural Science, 1806): “Steffens has needlessly perplexed his reasoning by his strange use of Subjective and Objective — his Subjectivity] = the Objectivity] of former Philosophers, and his 0[bjectivity] = their Subjectivity].” But by 1817 Coleridge had made the barbarous terminology his own, interpreting it in a way that was to become standard thereafter: “Now the sum of all that is merely OBJECTIVE, we will henceforth call NATURE, confining the term to its passive and material sense, as comprising all the phaenomena by which its existence is made known to us. On the other hand the sum of all that is SUBJECTIVE, we may comprehend in the name of the SELF or INTELLIGENCE. Both conceptions are in necessary antithesis.”

Starting in the 1820s and 1830s, dictionary entries (first in Ger man, then in French, and later in English) began to define the words “objectivity” and “subjectivity” in something like the (to us) familiar sense, often with a nod in the direction of Kantian philosophy. In 1820, for example, a German dictionary defined objektiv as a “rela tion to an external object” and subjektiv as “personal, inner, inhering in us, in opposition to objective”; as late as 1863, a French dictionary still called this the “new sense” (diametrically opposed to the old, scholastic sense) of word objectif and credited “the philosophy of Kant” with the novelty. When the English man of letters Thomas De Quincey published the second edition of his Confessions of an English Opium Eater in 1856, he could write of “objectivity”: “This word, so nearly unintelligible in 1821 [the date of the first edition], so in tensely scholastic, and consequently, when surrounded by familiar and vernacular words, so apparently pedantic, yet, on the other hand, so indispensable to accurate thinking, and to wide thinking, has since 1821 become too common to need any apology.” Some time circa 1850 the modern sense of “objectivity” had arrived in the major European languages, still paired with its ancestral opposite “subjectivity.” Both had turned 180 degrees in meaning.

Skeptics will perhaps be entertained but unimpressed by the curious history of the word “objectivity.” Etymology is full of oddities, they will concede, but the novelty of the word does not imply the novelty of the thing. Long before there was a vocabulary that cap tured the distinction that by 1850 had come to be known as that between objectivity and subjectivity, wasn’t it recognized and observed in fact? They may point to the annals of seventeenth-cen- tury epistemology, to Bacon and Descartes.14 What, after all, was the distinction between primary and secondary qualities that Descartes and others made, if not a case of objectivity versus subjectivity avant la lettrel And what about the idols of the cave, tribe, marketplace, and theater that Bacon identified and criticized in Novum organum (New Organon, 1620): don’t these constitute a veritable catalogue of subjectivity in science?

These objections and many more like them rest on the assump tion that the history of epistemology and the history of objectivity coincide. But our claim is that the history of objectivity is only a sub set, albeit an extremely important one, of the much longer and larger history of epistemology — the philosophical examination of obstacles to knowledge. Not every philosophical diagnosis of error is an exercise in objectivity, because not all errors stem from subjectiv ity. There were other ways to go astray in the natural philosophy of the seventeenth century, just as there are other ways to fail in the science of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Take the case of the primary-secondary quality distinction as Descartes advanced it in the Principia philosophiae (Principles of Philosophy, 1644). Descartes privileged size, figure, duration, and other primary qualities over secondary qualities like odor, color, pain, and flavor because the former ideas are more clearly and distinctly per ceived by the mind than the latter; that is, his was a distinction among purely mental entities, one kind of idea versus another — what nineteenth-century authors would (and did) label “subjec tive.” Or Bacon’s idols: only one of the four categories (the idols of the cave) applied to the individual psyche and could therefore be a candidate for subjectivity in the modern sense (the others refer to errors inherent in the human species, language, and theories, respec tively). Bacon’s remedy for the idols of the cave had nothing to do with the suppression of the subjective self, but rather addressed the balance between opposing tendencies to excess: lumpers and split ters, traditionalists and innovators, analysts and synthesizers. His epistemological advice —bend over backward to counteract one sided tendencies and predilections — echoed the moral counsel he gave in his essay “Of Nature in Men” on how to reform natural incli nations: “Neither is the ancient rule amiss, to bend nature as a wand to a contrary extreme, whereby to set it right; understanding it where the contrary extreme is no vice.”

The larger point here is that the framework within which seven teenth-century epistemology was conducted was a very different one from that in which nineteenth-century scientists pursued scientific objectivity. There is a history of what one might call the nosology and etiology of error, upon which diagnosis and therapy depend. Subjectivity is not the same kind of epistemological ailment as the infirmities of the senses or the imposition of authority feared by earlier philosophers, and it demands a specialized therapy. However many twists and turns the history of the terms objective and subjective took over the course of five hundred years, they were always paired: there is no objectivity without subjectivity to suppress, and vice versa. If subjectivity in its post-Kantian sense is historically specific, this implies that objectivity is as well. The philosophical vocabulary of mental life prior to Kant is extremely rich, but it is notably differ ent from that of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: “soul,” “mind,” “spirit,” and “faculties” only begin to suggest the variety in English, with further nuances and even categories available in other vernaculars and Latin.

Post-Kantian subjectivity is as distinctive as any of these concepts. It presumes an individualized, unified self organized around the will, an entity equivalent to neither the rational soul as con ceived by seventeenth-century philosophers nor the associationist mind posited by their eighteenth-century successors. Those who deployed post-Kantian notions of objectivity and subjectivity had discovered a new kind of epistemological malady and, consequently, a new remedy for it. To prescribe this post-Kantian remedy — objectivity — for a Baconian ailment — the idols of the cave — is rather like taking an antibiotic for a sprained ankle.

Although it is not the subject of this book, we recognize that our claim that objectivity is new to the nineteenth century has implica tions for the history of epistemology as well as the history of science. The claim by no means denies the originality of seventeenth-century epistemologists like Bacon and Descartes; on the contrary, it magni fies their originality to read them in their own terms, rather than tacitly to translate, with inevitable distortion, their unfamiliar pre occupations into our own familiar ones. Epistemology can be re conceived as ethics has been in recent philosophical work: as the repository of multiple virtues and visions of the good, not all simul taneously tenable (or at least not simultaneously maximizable), each originally the product of distinct historical circumstances, even if their moral claims have outlived the contexts that gave them birth.18

On this analogy, we can identify distinct epistemic virtues — not only truth and objectivity but also certainty, precision, replicability — each with its own historical trajectory and scientific practices. Histo rians of philosophy have pointed out that maximizing certainty can come at the expense of maximizing truth; historians of science have shown that precision and replicability can tug in opposite direc tions.19 Once objectivity is thought of as one of several epistemic virtues, distinct in its origins and its implications, it becomes easier to imagine that it might have a genuine history, one that forms only part of the history of epistemology as a whole. We will return to the idea of epistemic virtues below, when we take up the ethical dimen sions of scientific objectivity.

The skeptics are not finished. Even if objectivity is not coextensive with epistemology, they may rejoin, isn’t it a precondition of all sci ence worthy of the name? Why doesn’t the mathematical natural philosophy of Newton or the painstaking microscopic research of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek qualify as a chapter in the history of objectivity? They will insist that scientific objectivity is a transhis- toric honorific: that the history of objectivity is nothing less than the history of science itself.

Our answer here borrows a leaf from the skeptics’ own book. They are right to assert a wide gap between epistemological precept and scientific practice, even if the two are correlated. Epistemology (of whatever kind) advanced in the abstract cannot be easily equated with its practices in the concrete. Figuring out how to operationalize an epistemological ideal in making an image or measurement is as challenging as figuring out how to test a theory experimentally. Epistemic virtues are various not only in the abstract but also in their concrete realization. Science dedicated above all to certainty is done differently — not worse, but differently — from science that takes truth-to-nature as its highest desideratum. But a science devoted to truth or certainty or precision is as much a part of the history of sci ence as one that aims first and foremost at objectivity. The Newtons and the Leeuwenhoeks served other epistemic virtues, and they did so in specific and distinctive ways. It is precisely close examination of key scientific practices like atlas-making that throws the contrasts between epistemic virtues into relief. This is the strongest evidence for the novelty of scientific objectivity.

Objectivity the thing was as new as objectivity the word in the mid-nineteenth century. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, men of science began to fret openly about a new kind of obstacle to knowledge: themselves. Their fear was that the subjective self was prone to prettify, idealize, and, in the worst case, regularize observa tions to fit theoretical expectations: to see what it hoped to see. Their predecessors a generation or two before had also been beset by epistemological worries, but theirs were about the variability of nature, rather than the projections of the naturalist. As atlas makers, the earlier naturalists had sworn by selection and perfection: select the most typical or even archetypical skeleton, plant, or other object under study, then perfect that exemplar so that the image can truly stand for the class, can truly represent it. By circa 1860, however, many atlas makers were branding these practices as scandalous, as “subjective.” They insisted, instead, on the importance of effacing their own personalities and developed techniques that left as little as possible to the discretion of either artist or scientist, in order to obtain an “objective view.” Whereas their predecessors had written about the duty to discipline artists, they asserted the duty to disci pline themselves. Adherents to old and new schools of image making confronted one another in mutual indignation, both sides sure that the other had violated fundamental tenets of scientific competence and integrity. Objectivity was on the march, not just in the pages of dictionaries and philosophical treatises, but also in the images of sci entific atlases and in the cultivation of a new scientific self.