The world of bullshit we’ve built

Reflections on a scene from Utopia

Cross-posted at Troppo.

I recently took my son to the stage play of Yes, Prime Minister. … The decades have made a huge difference in the sensibility of the new production … . The series ran through most of the 1980s, a period that contained its share of tumult. … But somehow the dramas were genteel, reflecting battles between those privileged enough to be in the system. Waste in government continued, powerful people and time-servers were protected when they should have been exposed and dealt with. But one could be forgiven for thinking, at the end of an episode, ‘it was ever thus’. [A generation] on, as the moral dilemmas piled up in the stage-play, the governors conspired against the governed.

It’s hard to put one’s finger on it, but to speak loosely, I’d say that when I joined it fifty-odd years ago, life inside the workforce was about 80% the lifeworld — just getting on with people, doing one’s job whatever it was. I was in Canberra and got a holiday ‘bridging’ job in the ACT over the summer hols. I was part of a small team administering rebates to people on their public housing rent for various reasons of need. (Rosemary who I was assisting was a very nice person and had loved being a nurse. She didn’t love this, but it was OK and it paid better.) In any event, although it was administrative, it was still a concrete system, not unlike running public transport or a newsagent. At least inside the beast, you could tell whether anything too silly was being done.

The other 20% was, if you like ‘the system of the system’ which hierarchies are preoccupied with. Reports to superiors and so on, though given how concrete what one was doing was, this worked reasonably well. I guess it wouldn’t be hard to find stories of fairly comprehensive waste to protect some superior’s view of things. But there was little high farce of the kind so beautifully sent up in Utopia.

I’d never accuse this world of being ‘high performing’. It was quite mediocre, but it was human, it muddled through, one wasn’t encouraged to have tickets on yourself. There was a tea lady of some standing who came round every morning and afternoon. Nor do I want to suggest that such an office wouldn’t contain antagonisms — perhaps quite deep ones. But there was quite an ethic of getting on and helping out. And that contributed to a deep kind of egalitarianism. Seniority was respected but not fawned over. And commonsense was a strong anchor in life.

Fast forward to today and the degree of farce is just off the charts. At the tail end of the world I’m describing, we did away with national anthems beginning movies and toasts to the Queen at the very most pompous events. Now everything is populated with new pieties. Each meeting — often each speech given at a function — is preceded by an acknowledgement of country. People are constantly involved in farcical activities — of the kind satirised in Utopia.

Almost certainly their workplace operates with a whole anti-thinking apparatus up in lights — mission and vision statements and ‘values’ statements. If you’re at one of these events it is not a good move, for your blood pressure, your self-respect or your career to say that you don’t think that the values of an organisation can be written in a list hung in the foyer — that values aren’t like that. That values might have names in our language, but they are present in our lives as choices.

Now even after fifty years of development such things still don’t take up that much time. But they are central to the official governance of the organisation. I don’t think of them as causes so much as symptoms of something much deeper. They’re the tip of a large iceberg in which;

What is said and what is done within and by organisations are able to float pretty much freely away from each other;

There was always plenty to object to in the worlds of mainstream politics and media, but today they are mostly infantile — including most ‘quality’ media coverage of politics which is glorified racecalling.

Government reports are full of bland-out — pleasing words “improve”, “reform”, “sustainable”, “accountable”, “transparent” and on and on, and only someone who wasn’t paying attention thinks those words mean what they say. They could mean what they say, they could mean the opposite. Unless I’m deep in some issue, I don’t read government reports because they can’t be understood without being an insider. The same goes for corporate reports. And come to think of it, would you get much more than a fairly predictable schtick from the annual report of a major NGO?

Back then, discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation could live a fairly robust existence within the ‘commonsense’ of the workplace and this was obviously a very bad thing. So in major respects things are better than that today. We also go after things like bullying in the workplace. And there’s a lot of it about. So going after it is certainly a laudable goal. But it’s a very difficult goal and we don’t proceed as if it were. The upshot is that we’re giving lots of power to people who can game such systems — bullies in fact. Should we give up on anti-bullying? I’d hope we wouldn’t need to, but I think it’s quite likely that — perhaps after a few years where the new arrangements help a little — the systems become gamed by bullies so badly that they do more harm than good. Have we set these systems up to help us know if things are going awry? Nope. We’ve set them up as we always do — as elaborate role plays with accountability theatre to the higher-ups. What could possibly go wrong?

These dot points are just that — a few scattered thoughts. Many more phenomena could be itemised — perhaps I’ll do that as they occur to me.

I won’t claim to be able to articulate it much beyond what I’ve said here. It’s bugged me that I can’t do better for ages, but watching the Utopia clip above spured me to note it, because, it’s trying to make a similar point.

Great anti-bullying idea for schools

Podcast of the week

The Brits do ‘formats’ way more than us. They make a lot of money from it as a major exporter of reality TV formats. (Fun fact acquired from Lateral Economics’ work for the Screen Producers of Australia) But they’re age-old on the BBC. I remember my parents tuning in to My Word when I was a kid. And there are any number of other programs whether one’s brow is high or low. Much less so here. And it continues in programs like Great Lives.

In any event, I found this half-hour on Arthur Ashe riveting. Others had had the same idea as he had in the final of Wimbledon in 1975 — to send back ‘dead’ returns to rob the new kid Jimmy Connors of the ball speed he thrived on. But a 39-year-old Ken Rosewall had tried that the previous year at Wimbledon and lost 6–1, 6–1, 6–4. Ashe was 32 and seemingly past his prime. And his score against Connors was 3-0. From memory, Ashe added a deadly mix of low balls testing Connors's forehand volley and a cat-like sense around the court. You can watch 25 minutes highlights here.

But the podcast was interesting for the man Ashe was, a man who survived the viciousness of Virginia 1950s Jim Crow racism with a grace and a steel that left me in awe.

How the Right Turned Radical and the Left Became Depressed

From a one year old Ross Douthat column. Differences in wellbeing between lefties and righties in the US is very striking.

As Musa al-Gharbi writes, the happiness gap between liberals and conservatives is a persistent social-science finding, across several eras and many countries. [And] the view that “my life is pretty good, but the country is going to hell,” which seems to motivate certain middle-class Donald Trump supporters, would have been unsurprising to hear in a bar or at a barbecue in 1975 or 1990, no less than today.

But something clearly has shifted. In Gallup polling from 2019, just before the pandemic, the happiness gap between Republicans and Democrats was larger than in any previous survey. And the trend of worsening mental health among young people, the subject of much discussion lately, is especially striking among younger liberals. (For instance: Among 18- to 29-year-olds, more than half of liberal women and roughly a third of liberal men reported that a health care provider had told them they had a mental health condition, compared with about a fifth of conservative women and around a seventh of conservative men, according to an analysis of 2020 Pew Research Center data by the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt.) …

In new polling commissioned by The Wall Street Journal … the share of Americans saying that patriotism is very important to them fell from 70 percent in 1998 to 38 percent today. The percentage calling religion very important fell from 62 percent to 39 percent over the same period. The percentage saying that having kids was very important dropped from 59 percent to 30 percent. Only money saw its professed importance rise. …

Unfortunately in finding its heart’s desire the left also seems to have found a certain kind of despair. It turns out that there isn’t some obvious ground for purpose and solidarity and ultimate meaning once you’ve deconstructed all the sources you consider tainted. And it’s at the vanguard of that deconstruction, among the very-liberal young, that you find the greatest unhappiness — the very success of the progressive project devouring contentment.

But that project is now entrenched in so many American institutions that there’s no natural anti-institutional form for these discontents to take. …

here is a coherent (if insufficient) left-wing account of the decline of family, patriotism, religion — one that emphasizes the corrosive role of consumer capitalism, its dissolving effect on all loyalties higher than the self, its interest in creating addictions for every age and walk of life. …

But the contemporary left is fundamentally too invested in liberating the individual from oppressive normativity to sustain any defense of the older faiths and folkways — which is why it has often ended up as consumerism’s cultural ally despite its notional “late capitalism, man” critique.

Thus our peculiar situation: a once-radical left presiding somewhat miserably over the new order that it long desired to usher in, while a once-conservative right, convinced that it still has the secret of happiness, looks to disruption and chaos as its only ladder back from exile.

Race: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t

Another fine piece on the dilemmas of racial politics from Joseph Heath.

It’s kind of obvious that political campaigners put the best spin on their position they can. But if you pay close attention, most political debate barely rises to any kind of meaningful exchange of viewpoints at all. As Charles Wylie pointed out to me recently, there’s an obvious tension between the goals of indigenous socio-economic equality with non-indigenous Australians and their self-determination. It doesn’t mean we can’t go for both, but no-one who doesn’t want to be called racist wants to get tangled up in the actual difficulties of asking whether it’s possible and what it would mean.

If there’s much political theory on this, I’d be interested to know of it. In the meantime, the best I've seen is James Burnham’s making the points I’ve just made in a more lofty but different way. I wrote them up in my ‘coming out’ as “Alt-Centre”.

There is a sharp divorce between what I have called the formal meaning [of political speech], the formal aims and arguments, and the real meaning, the real aims and argument (if there is, as there is usually not, any real argument).

The formal aims and goals are for the most part or altogether either supernatural or metaphysical-transcendental—in both cases meaningless from the point of view of real actions in the real world of space and time and history; or, if they have some empirical meaning, are impossible to achieve under the actual conditions of social life. In all three cases, the dependence of the whole structure of reasoning upon such goals makes it impossible for the writer (or speaker) to give a true descriptive account of the way men actually behave. A systematic distortion of the truth takes place. And, obviously, it cannot be shown how the goals might be reached, since, being unreal, they cannot be reached.

From a purely logical point of view, the arguments offered for the formal aims and goals may be valid or fallacious; but, except by accident, they are necessarily irrelevant to real political problems, since they are designed to prove the ostensible points of the formal structure—points of religion or metaphysics, or the abstract desirability of some utopian ideal. …

This method, whose intellectual consequence is merely to confuse and hide, can teach us nothing of the truth, can in no way help us to solve the problems of our political life. In the hands of the powerful and their spokesmen, however, used by demagogues or hypocrites or simply the self-deluded, this method is well designed, and the best, to deceive us, and to lead us by easy routes to the sacrifice of our own interests and dignity in the service of the mighty.

Anyway, enough theory. Here’s the piece.

If you did a survey of Americans, most would probably say that it’s a terrible idea to play two national anthems before football games. (Football, incidentally, is by far the most integrated sport in America). Why? Because it’s divisive. It defeats the entire purpose of having a national anthem. But of course Americans cannot express this opinion publicly without being labeled racist, as Megyn Kelly discovered. Naturally once Kelly was attacked, a bunch of Republicans leaped to her defence, which then made her position politically toxic for all Democrats. (Meanwhile a number of Democratic politicians, following that party’s infallible instinct for adopting politically suicidal positions, chimed in not just to defend the practice of racially-segregated anthems, but to castigate white fans for not standing during the “Black national anthem.” And people wonder why Democrats have trouble getting Americans to vote for them…)

In any case, it’s not difficult to see the norm that has emerged here. On the liberal/progressive side, any opposition to Black nationalism gets coded as racist. (I’m assuming there is no need to defend here the claim that wanting to have your own national anthem is a nationalist sentiment.) Many Americans, however, find this extremely confusing, because as far as they can tell, Black nationalism just is racist. That’s because, like most minority nationalists, Black nationalists are opposed to integration, while seeking to promote heightened racial solidarity (so they do things like guilt-trip Black athletes for attending “white colleges”). Cultivating in-group solidarity practically always generates out-group antagonism, and so unless people bend over backwards to avoid it, nationalism has an unpleasantly exclusionary quality.

To the extent that there is any debate over Black nationalism in America, it therefore consists of a bunch of people calling each other racist. If you support it, you’re a racist, but if you criticize it, you’re also a racist. What this translates into in practice is that sensible Americans don’t want to say anything on the subject, because they don’t want to be called racist. In particular, it means that all educated white Americans to the left of Mitt Romney know enough to keep their mouths shut. (This is why white Americans get so excited when someone like John McWhorter, or now Coleman Hughes, comes along, who is willing to defend publicly the position that most liberal white Americans privately hold.)

LoU Zeldis at Rebecca Hossack Gallery

An economist, a lawyer, a theologian and a journalist walk into a panel show

Really terrific exchange, particularly between Martin Wolf and Daniel Markovits. Madeleine Pennington is good too, but it would have taken more skilful chairing than the session got. It’s often quite good if a chair directs discussion and doesn’t let it wander any old where. But this chair didn’t recognise when he needed to give his horses their head, because they were answering his questions in far more interesting ways than were dreamt of in his philosophy. So he did the journalist’s thing which is to demand that his interviewees answer his questions in the way he had in mind rather than in a way that makes an actual contribution to the discussion. (I’m reminded of the first time I saw Yanis Varoufakis being interviewed.)

On Bowles, Friedman, and the Loyalty Oath

Great post which I reproduce in full:

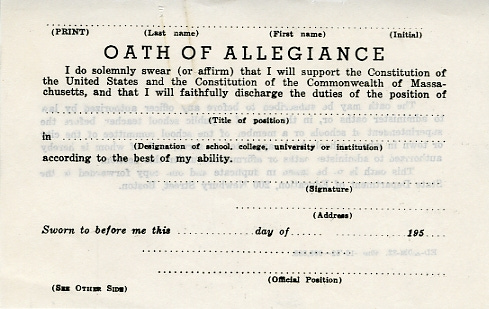

In March of 1966 the economist Sam Bowles was threatened with dismissal by Harvard University for refusing to sign the following oath of allegiance:

The oath had been required of all teachers in the state since 1935, including those employed at private institutions.

I understand from conversations with Sam that he had no particular objection to the text of the oath, but believed that the requirement to sign it was unconstitutional. As a result, he risked losing a job that he had begun just a few month earlier, at the age of twenty-six. He was married with two children at the time.

Sam was not the first to refuse to sign the oath, but he was among the last. The requirement was indeed judged unconstitutional in April 1967 following a challenge by Joseph Pedlosky, then an Assistant Professor of Mathematics at MIT. As it happens, the ruling in Pedlosky v. Massachusetts Institute of Technology was based not on freedom of speech concerns, but rather on the vagueness of the pledge to discharge one’s duties to the best of one’s ability:

The courts are exposed to the very real possibility of being asked to determine the degree of skill and faithfulness with which the plaintiff discharges the duties of his private position in teaching mathematics and perhaps to compare that degree with that of the best of his ability. This evaluation process is altogether too vague a standard to enforce judicially. It is not a reasonable regulation in the public interest.

While Sam was able to keep his position in the end, there was a period of time during which the outcome was far from certain. During this period, I understand from Sam that he was contacted by the University of Chicago with an offer of employment, and that this offer was supported by Milton Friedman.

This is interesting because Friedman and Bowles were about as ideologically far apart as it was possible to be in the profession at the time.

Four years later, Gottfried Haberler came to hear of Friedman’s support for the offer, and was appalled. He wrote a brief letter to Friedman asking for confirmation, and got the following reply:

Some years back I had occasion to read some of the work which Bowles had done in connection with our consideration of him at that time. I was very favorably impressed indeed by the intellectual quality of the work and the command that it displayed of analytical economics. At that time I was very much in accord with our decision to make him an offer of a position. He turned us down to stay at Harvard.

I have very vague recollections about what has happened this year. I do not know for certain whether or not we did make an offer to him this year. We may have done so; and if so, I would not have objected since the only consideration I would have considered relevant would have been his intellectual qualities.

This speaks well of Friedman, of course. But it also had a deep and lasting effect on Sam, who recalls and occasionally recounts this tale.

Update: Sam, via email, says

It is a story worth recounting in this highly polarized world. Universities sometimes act like, well, universities.

Update #2: Sam Bowles and Milton Friedman both sought to influence public opinion and policy, and relished debate. This clip from a debate between the two in 1990 … is worth a look. [It’s the YouTube video above.]

What a comedian can get away with

Henry Oliver on imagination as the apex faculty

A good article putatively of the ‘how to be a successful entrepreneur’ genre but which is far more general in its application than that. It expresses the ideal as a balance between the poles of various dichotomies — intrinsic and extrinsic, mimesis and anti-mimesis, innovative and conventional. But there’s something more elusive between the poles which is the true self.

Emerson has a crack at it as does the silicon valley guru Paul Graham who argues that imagination is the key. Though even here I think he doesn’t quite go far enough because imagination is more than, as Graham puts it “the kind of intelligence that produces ideas with just the right level of craziness”. The most powerful point being made is the way in which imagination is the faculty which must (by definition) initate the new. It might begin as a spark, but effective imagination working in the world is more than that. It is not much use unless it comes with sufficient clarity and conviction for something to be seen through.

I’ve chopped the piece around a bit to get it to a reasonable size, but the piece will reward your clicking through to the whole thing.

When [Larry Page] was twelve, Page read Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla, which described how Tesla remained anonymous because of his lack of commercial ability. Despite the fact that he was a genius, whose ideas were lighting up the world, “He was just one of the strange individuals of whom it takes a great many of varying types to make up a complete population of a great metropolis.” That is the final sentence of Prodigal Genius. It made twelve-year-old Larry Page cry, and stayed with Page for the rest of his life.

[T]he most important insight of his career [was] that to be a successful innovator, one must be commercial, as well as create something new—was a revelation delivered emotionally. That is what made him an Edison of our time, rather than a Tesla. He learned how to conform when he needed to, and when to stick to his own ideas. … Larry Page was so successful because he harnessed the productive tension between conformity and independence. He was neither part of the crowd nor inimically opposed to it. He found a balance between mimesis and anti-mimesis. …

So, the question arises—how can we become anti-mimetic, to avoid the trap of imitating and fighting our rivals and thus limiting ourselves?

This is not a simple question of taking the path less trodden. Girard warned that many people leave the familiar path only to fall into the gutter. All too often, the non-conformist is the most conventional of all. As Peter Thiel said, “The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.”

True anti-mimesis comes from the inner self, the originating force inside us. You might call this a mind, or a soul. To the Ancient Greeks, it was a daemon, an inner spirit. We often think of it as consciousness: the something inside you that is uniquely you and feels like you.

This inner self means something inside us pre-exists mimesis. We are not blank slates. When we see something we want to imitate, it must chime with something already inside us. We do not blindly imitate what we are exposed to. There is interplay. “The fact narrated,” the transcendentalist philosopher Emerson said, “must correspond to something in me to be credible or intelligible.” …

What we need is imitation that is provocative, not passive. As Emerson said,

Truly speaking, it is not instruction, but provocation, that I can receive from another soul. What he announces, I must find true in me, or reject; and on his word, or as his second, be he who he may, I can accept nothing.

When people with language far beyond our context speak, we might want to imitate them. That is provocation—it draws out something of us that we wish to develop, like Page and Tesla.

Girard’s insights teach us how difficult it can be to do this in a non-conformist manner. Emerson anticipated that: “To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.” The more limits we allow on the people, places, ideas, and circumstances we are exposed to, the more limits we impose on our language, on our context—the less aspirational we can be. But the more people we are exposed to, the more chances there are for extrinsic motivation to dampen our intrinsic motivation.

We do not need to follow Girard to control our own mimetic desires. Prohibition and ritual are not the only techniques. We can follow Emerson and expand our imagination, expand our language, expand our world. We can nurture our inner light. To Girard, we want what others prevent us from possessing. But to Emerson, history was the application of the manifold spirit of man to the manifold world. Nurture your spirit.

The aim of a startup is to make something everyone wants that no-one has thought of before, to have an idea that only seems obvious in retrospect. In this way, a good founder is an essentially creative person. That’s why Paul Graham describes imagination as the most important form of intelligence. …

There is much good writing available about how to be anti-mimetic, but nothing can substitute for the expansion of your imagination. Art provokes like nothing else can. All great art—music, movies, paintings, literature, architecture, photography, theatre—can be a means of expanding our consciousness, including biographies of Tesla. Travel accomplishes this as well, as do all forms of engaging with new cultures. To insist on yourself, as Emerson had it, you must expand, create, and discover yourself through the acquisition of new language and new ideas. We must discover the best of the world and be provoked by it.

Jane Austen: where has she been all this time?

As you know, our mission statement is “We exist to be world-class in everything we do and to occasionally mention Jane Austen”. Just last week, someone in our Special Features Division was counselled for inappropriate behaviour. They had pointed out the glaring disparity between this mission statement and the fact that Jane Austen hasn’t been mentioned on the substack since its inception over two years ago. Anyway, after some organisational angst, we dipped into our values statement here at I Know Nothing Productions. There Value Four says that we’re the change we want to see. So the word went out. We were after something on the internet that showed how Jane Austen changed fiction for a very, very (or even extremely) long time.

As it turned out, we were able to go one better.

How Jane Austen Changed Fiction Forever

‘Free indirect style’ is cool

I wavered over including this piece — does it say anything big or super interesting? Well depends on your point of view. I found it interesting. But when I watched the video I knew I wanted to show it to you. Again, this is a ‘me’ thing because I’ve become interested in the new medium of explainer videos, but somehow watching the video — it’s not much more than five minutes — made the points more vividly. They went in more.

At the beginning of her very first book says Evan Puschak, Austen “did something that changed fiction forever.” Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, has in his latest video chosen Sense and Sensibility as an example with which to explain the key technique that set its author’s work apart. When, in the scene in question, the dying Henry Dashwood makes his son John promise to take care of his three half-sisters, the younger man inwardly resolves to himself to give them a thousand pounds each. “Yes, he would give them three thousand pounds,” Austen writes. “It would be liberal and handsome! It would be enough to make them completely easy. Three thousand pounds! He could spare so little a sum with a little inconvenience.”

What, exactly, is going on here? Before this passage, Puschak explains, “the narrator is describing the thoughts and feelings of John Dashwood.” But then, “something changes: it’s suddenly as if we’re inside John’s mind. And yet, the point of view doesn’t change: we’re still in the third person.” This is a notable early example of what’s called “free indirect style,” which literary critic D. A. Miller describes as a “technique of close writing that Austen more or less invented for the English novel.” When she employs it, “the narration’s way of saying is constantly both mimicking, and distancing itself from, the character’s way of seeing.”

Alain de Botton on Jane Austen

I poked around on the same site I watched the video above and found this video which I also liked. And its appreciation of my father’s favourite book Pride and Prejudice was the same as the one I offered in my own effort called “Adam Smith is to markets what Jane Austen was to marriage”.

Men Mansplaining to Men: SHOCK!!

Let me explain something. In addition to sexism, there’s also another factor at work. The Economist splains the issues.

“Mansplaining”, before it was so named, was identified by Deborah Tannen in her 1990 book “You Just Don’t Understand”. Ms Tannen, a linguist at Georgetown University. … Ms Tannen says … “the inequality of the treatment results not simply from the men’s behavior alone but from the differences in men’s and women’s styles.” … In Ms Tannen’s schema, men talk to determine and achieve status. Women talk to determine and achieve connection. To use metaphors, for men life is a ladder and the better spots are up high. For women, life is a network, and the better spots have greater connections.

What evidence shows that male and female styles differ? Among the most compelling is a crucial piece left out of the “simple sexism” explanation: men mansplain to each other. Elizabeth Aries, another researcher, analysed 45 hours of conversation and found that men dominated mixed groups—but she also found competition and dominance in male-only groups. Men begin discussing fact-based topics, sizing each other up. Before long, a hierarchy is established: either those who have the most to contribute, or those who are simply better at dominating the conversation, are taking most of the turns. The men who dominate one group go on to dominate others, while women show more flexibility in their dominance patterns. The upshot is that a shy, retiring man can find himself endlessly on the receiving end of the same kinds of lectures that Ms Tannen, Ms Chemaly and Ms Solnit describe.

When men and women get together, the problem gets more systematic. Women may be competitive too, but some researchers (like Joyce Benenson) argue that women’s strategies favour disguising their tactics. And if Ms Tannen’s differing goals play even a partial role in the outcome, we would expect exactly the outcome we see. A man lays down a marker by mentioning something he knows, an opening bid in establishing his status. A woman acknowledges the man’s point, hoping that she will in turn be expected to share and a connection will be made. The man takes this as if it were offered by someone who thinks like him: a sign of submission to his higher status. And so on goes the mansplaining. This is not every man, every woman, every conversation, but it clearly happens a lot. …

Ms Chemaly is right that not all the lessons should be aimed at getting women and girls to speak more like men. Both boys and girls should be taught that there are several purposes to talking with others. To exchange information, to achieve status and to achieve connection are goals of almost any conversation. If one party to a chat expects an equal exchange and the other is having a competition, things get asymmetrical—and frustrating.

So, boys and girls, if you have something to say, speak up—your partner may not necessarily hand you the opportunity. And if you find yourself having talked for a while, shut up and listen. Your partner isn’t necessarily thick: it could be the other person is waiting for you to show some skill by asking a question. There are plenty of intra-sex differences among boys and among girls, and enough to commend both approaches to conversation. So the best way to think of this is not the simple frame that women need to learn how to combat “old-fashioned sexism”. Rather, both sexes need to learn the old-fashioned art of conversation.

Ecclesiastes, Skepticism, Conservatism, and Warren Buffett

Moderns and postmoderns pride themselves on skepticism, and yet many are quite certain that they know better than the ancients, that their atheism is truly skeptical in contrast to naive religious belief. They wield skepticism to challenge authority they view as irrational or corrupt, but fail to direct the skepticism at themselves.

My claim here is modest. It is not to argue in favor of tradition over change in the abstract, but to point out that skepticism as a philosophical worldview and temperamental disposition cannot be used to justify the rejection of tradition. Rather, skepticism can favor philosophical conservatism, the view that we should presume conventional wisdom correct unless we can prove otherwise, with a strong margin of safety.

If you want to challenge tradition you need to overcome skepticism. You need to believe that you know better than hundreds and thousands of years of received understanding. Scientific progress is one area where this seems to be the case. We used to think the earth is flat, now we don’t. We used to be geocentric, now we are heliocentric. Proving that scientific progress validates moral progress, however, is a harder case. Does the fact that Aristotle was wrong about gravity mean he was wrong about friendship? The problem with modern overconfidence is the rubric of relative comparison; does being smarter than another make you any more right? Does being more clever than someone else make you holistically wiser? No. This is one argument in Ecclesiastes. The sage excels the fool, yet both are fools, just different in degree. To quote Hegel, the human condition is the night in which “all cows [sage and fool] are black.” Both sage and fool suffer the same fate. Zoomed out, they are indistinguishable.

A core theme in Warren Buffett’s shareholder letters is the importance of avoiding fatal errors. Avoiding the permanent loss of capital is far more important than anything else. Buffett makes a few investments a year, sometimes none. Buffett retains a large cash position on the Berkshire balance sheet, an inherently conservative attitude. One test that Buffett asks us to apply when investing: could you forget about the investment for 10, 20, 30, 40 years and be happy knowing you’ll come back to it? Applied spiritually, we could expand the question: what deeds will we not regret having done at the end of our lives? What beliefs and values can we feel relatively secure about?

Now you might say that Buffett’s restraint is conservative, but his investments require confidence. There is no contradiction here. Being conservative about most things frees us up to take a few real bets. This is another under-appreciated aspect of tradition; by offering us a playbook it reduces the number of decisions we need to make. It allows us to focus on making decisions that move the needle.

It is often thought that existentialism and traditionalism are opponents. The one is associated with hippies and boomers, the other with baroque institutions. But existentialism and traditionalism are compatible in three ways: 1) an existentialist chooses to accept the yoke of tradition 2) an existentialist lives inside tradition so as to make it unique and 3) an existentialist locates opportunities for action where tradition fails to be directive.

Ecclesiastes says we can’t know much and that what we do know won’t help us much. Buffett says only invest in what you know well. But Ecclesiastes also says that we should focus on what is in our sphere of power; following the divine commandments, living a life in awe of God, taking modest pleasure in trying to live decently, accepting that the consequences of our deeds are not in our control. Moreover, there is no such thing as outperformance, since all is vanity. Live humbly. Ironically, this will yield the best return on invested breath.

The battle for Israel’s soul

What are Conditions in Gaza Like?

Activist Narratives and Basic Health Metrics Tell Two Different Stories

Coleman Hughes isn’t buying Norman Finkelstein’s (and David Cameron’s!) “open-air prison” narrative on Gaza or at least wants him to explain why the numbers don’t support his story. Note: this is pre-war — pre-rubble — Gaza.

A paper authored by a scholar at the University of Gaza put life expectancy at 72.5 years in 2006 (admittedly dated). Comparing that to the UN’s data on global life expectancy between 2005-2010, Gaza would have been around the 50th percentile of nations at the time.

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (located in the West Bank), in partnership with UNICEF, the UN Population Fund, and the Arab League, did two extensive studies of Palestinian Health in 2006 and 2010––(dated by now, but still worth looking at). For the 2010 study, they interviewed 15,355 families in the West Bank and Gaza.

According to the 2010 study, Gaza had an under-5 mortality rate of 26.8 (per 1,000). At the time, the World Bank put the overall under-5 mortality rate for the Middle East and North Africa at 27.6––which would make Gaza slightly better than average for the region. Today, the global population average is around 38.

The same 2010 PCBS study puts Gaza’s infant mortality rate at 20.1 (per 1,000). If it were its own country, that would have put Gaza in the 45th percentile among nations at the time. The global average was 37 in 2010 and is 28 today. Either way, this suggests that Palestinians in Gaza were doing better than average relative to the world. …

So either one of two things is true:

(1) These data are basically correct, and the (pre-war) conditions in Gaza were that of a middling developing nation. If true, the descriptions of Gaza as similar to a “concentration camp” or “open-air prison” begin to sound absurd. We should assume that the laundry list of facts seeming to support that picture stem from bad scholarship and/or cherry-picking. Surely, a “concentration camp” or “open-air prison” would not yield a population with health metrics above the global average––and on par with all the Arab nations surrounding it.

Or:

(2) The data here are wrong or misleading in some way. This is hardly impossible, considering how sparse they are to begin with. But if they are misleading, it would behoove Finkelstein and others who describe Gaza as a hellhole to explain in detail why these data––largely from Palestinian sources––are misleading.

My hunch is that (1) is the right interpretation. If nothing else, it would help explain this rather rosy Al-Jazeera segment from 2017.

Heaviosity half-hour

How life works; how cancer works

I’m still going on Philip Ball’s magnificent How Life Works, (or was when I wrote this) which I last extracted here. I’m still plying it for insights into all the dumb ways we think. (By “we”, at least in this context, I mean other people, not me — pretty obviously.) Anyway, in this passage, we see the importance of the different levels of coherence — and emergence — in trying to understand the world. And how, for all their magnificence, the early achievements of reductionism may be leading us further from, rather than closer to, reality.

Thinking can be so tricky!

Cancer as Demented Development

If there’s one affliction for which we have been long hoping for “unbelievable things,” it is cancer. Many decades of research have already transformed the chances of surviving it: almost 90 percent of people diagnosed with prostate, breast, or thyroid cancer in England, for example, are now still living five years later, and more than half of those diagnosed with any cancer are expected to survive for at least another ten years. But some types of cancer are still merciless: only 13 percent of people with brain or liver cancer, and just 7.3 percent of those with pancreatic cancer, will live with it for more than five years.

Militaristic metaphors about a “war against cancer” are rightly deplored by healthcare professionals—but it is now becoming clear that there can be no real victory in such a struggle anyway. We can and surely will continue to make advances in coping with cancer and extending the lifespan for those who have it. But whereas viral diseases such as smallpox or polio, or even COVID-19, can in principle be eradicated, cancer is different. For it looks ever less like a disease (or even a group of diseases) in the normal sense, and ever more like an inevitable consequence of being multicellular.

The common view that cancer is caused by uncontrolled cell proliferation was first proposed in 1914 by the German embryologist Theodor Boveri. Initially it was thought that this dysregulation is caused by errant genes from viruses that infect cells and inject their genetic material into the genome. In 1910 the American pathologist Francis Peyton Rous transferred cells from a cancer tumor in a chicken into another chicken, and found that the healthy chicken developed cancer too, suggesting it was caused by an infectious agent. Because the agent could not be extracted by a filter that would block bacteria, Rous concluded that it must be a virus. He was awarded the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this discovery of tumorinducing viruses.

The cancer-inducing viral genes were named oncogenes, after the ancient Greek word for tumors. (Yes, there was cancer in the ancient world too—contrary to a popular misconception, it is not a modern affliction.) But it soon became clear that there are analogues of such genes already in the human genome, which can unleash tumor growth if mutation sends them awry. In their normal healthy form, where they tend to be involved in regulating cell division, they are known as “proto-oncogenes.”9 Only if they acquire the fateful mutation do they turn a cell cancerous. In the view most widely held for the rest of the twentieth century, the excessive cell proliferation characteristic of tumors results from a genetic mutation in somatic (body) cells—the so-called somatic mutation theory. The narrative that developed is that such mutations transform cells into a “rogue” form in which they multiply without constraint.

It’s telling what kinds of genes oncogenes are. More than seventy of them are now known for humans, and typically they encode growth factors and their receptors, signal-transducing proteins, protein kinases, and transcription factors. In other words, they all tend to have regulatory functions—and moreover, ones that can’t be ascribed any characteristic phenotypic function but lie deeply embedded in the molecular networks of the cell. As we’ve seen, the consequences of dysfunction in such gene products can be extremely hard to predict or understand, for they may be highly dependent on context and might ripple through several different pathways of molecular interaction.

At the same time, the existence of all these oncogenes points to another instantiation of the canalization of disease. For the manifestation of cancer is much the same in any tissue or organ: cells develop in ways they should not, producing tumors that can deplete and disrupt the body’s resources to a lethal extent. In general, cancers stem from a change in the regulation of the cell cycle, the process by which cells divide and proliferate. Many dysfunctions of regulatory molecules caused by gene mutations can disrupt the cell cycle.

Such mutations may be inherited, conferring increased risk of developing cancer. That is the case, for example, for certain alleles of the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have been linked to breast cancer. But carcinogenic mutations can also be acquired de novo from environmental factors, such as chemicals or ionizing radiation that can damage DNA. The link between cancer and chemical agents in the environment was first established in relation to cigarette smoke, thanks in particular to the work of British epidemiologists Richard Doll and Bradford Hill in the 1950s.10 Thus, many cancers are not associated with any preexisting genetic vulnerability but are linked to random mutations in “genetically healthy” tissues. Only a small fraction of breast cancers, for example, are associated with the inheritable risk variants of BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Even the most careful and healthy of us will be exposed to carcinogenic agents. As the media are all too eager to tell us, they are present in many types of food, and we are constantly and unavoidably bombarded with ionizing radiation such as cosmic rays and X-rays. Our bodies have ways of suppressing the dangers of carcinogens and repairing the damage they do; in general, only if exposure is too great do problems arise. Some genes associated with cancer in fact play roles in preventing those problems: they are so-called tumor suppressors. Mutations to these genes might therefore lead to cancer because they inhibit the gene product from doing its prophylactic job. BRCA1 is one such, being a member of a group of genes that collectively repair damaged DNA. It’s ironic, as well as terribly confusing, then, that BRCA1 is named for the cancer-inducing nature of its malfunctioning allele: BReast CAncer type 1. Once again, the practice of linking a gene to an associated phenotype does not aid our appreciation of how genes work.

Apoptosis—the capacity of cells to spontaneously die in certain circumstances—is another evolved protection against tumor formation. Some cancers arise from a failure of apoptosis to happen when it should—when, for example, a cell has acquired too much DNA damage—and some treatments for cancer aim to induce apoptosis in tumor cells. Apoptosis is in some ways a default state of our cells: if they are grown in culture in isolation from others, they typically undergo apoptosis, because they rely on signals from neighboring cells to tell them not to.

Given the well-established link between cancer and genetic mutation, the disease has come to be seen as an aberration that is best understood and mitigated by seeking its genetic origins and developing treatments to suppress them. But decades of effort based on this picture have yielded little in the way of treatments. Our defenses against cancer remain depressingly crude: surgery to cut out tumors, and chemotherapy and radiotherapy to blast tumor cells with chemicals and radiation deadly not only to them but also to any healthy tissues that are caught in the crossfire—hence the debilitating ravages of traditional therapeutic regimes.

In recent years, this picture of cancer as a “disease to be cured at its genetic roots” has been waning. Ironically, it was genomics that most challenged that approach. The possibility of accumulating and sifting vast genomic data sets in the early 2000s led to the creation of the Cancer Genome Atlas, a joint project of the US National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute in 2006, which aimed to catalog all the significant gene mutations associated with cancers. The hope was that, once a cancer patient’s specific cancer-linked mutations were identified, it would be possible to prescribe exactly the right drugs needed to cure them. But despite funding to the tune of a quarter of a billion dollars, the effort has yielded little in the way of cures. One major trial of such targeted therapies for lung cancer, aggressively named BATTLE-2, had gravely disappointing clinical outcomes, failing to find any effective new treatments. In 2013, cancer scientist Michael Yaffe concluded that looking for cancer-linked genes was not the right strategy, and had been adopted more because scientists had the techniques to pursue it than because they had good reason to think it would work. “Like data junkies,” he wrote, “we continue to look to genome sequencing when the really clinically useful information may lie someplace else.” Where else? Yaffe suggested that the molecular interaction networks of cancer cells would be a good place to start. But oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee thinks we need to look at the larger picture: the higher levels of the hierarchy. We should look, he says,

in an intersection between the mutations that the cancer cell carries and the identity of the cell itself. The context. The type of cell it is (lung? liver? pancreas?). The place where it lives and grows. Its embryonic origin and its developmental pathway. The particular factors that give the cell its unique identity. The nutrients that give it sustenance. The neighboring cells on which it depends.

Perhaps in the end too, we need to reposition the whole concept of causation of cancer. The unpalatable truth is that tumor formation is something that our cells do: it is better regarded as a state that our cells can spontaneously adopt, much as “misfolded” proteins are one of their inevitable attractor states. You might say that if cells are to exist at all as entities that can replicate and self-regulate in communal collectives—that is, in multicellular organisms like us—it may be inevitable that they have the potential to become cancerous.11 To develop into tumors is one of the particular hazards of pluripotent stem cells, precisely because they have such fecund versatility. This poses challenges for using stem cells in regenerative medicine. It is precisely because our cells may naturally turn into cancer cells that we have evolved (imperfect) mechanisms to guard against them. By the same token, people doing bad things do not, in general, represent some anomaly or malfunction of the human brain—that is, sadly, just one of the consequences of being creatures like us—but we have developed (imperfect) social defenses against them. No one realistically expects to “cure” all bad behavior.

Some researchers believe that cancer is itself an evolutionary throwback: the cells revert to an ancient state, before they had learned to coordinate their growth in multicellular bodies. Whether that’s the right way to see it isn’t clear,12 but it’s certainly the case that the genes that tend to be most active in cancer cells are the “oldest” in evolutionary terms: those that have analogues in primitive forms of life. Analogues of the p53 gene, mutations of which are implicated in more than 50 percent of all cancers, for example, can be found in some single-celled members of the group of organisms called Holozoa, thought to have originated about a billion years ago.

Cancer reveals how precarious multicellularity can be. Abundant proliferation is, a priori, the best Darwinian strategy for cells: it’s precisely what we’d expect them to do, and bacteria are extremely good at it. But just as living in society requires us to suppress some of our instincts—we have to share resources, make compromises, restrain the impulse to plunder, cheat and fornicate with the partners of others—so too, when they are part of a multicellular body cells must moderate a tendency to replicate. They need to know when to stop. We’ve seen that a rather sophisticated system of molecular transactions lies behind this capacity for multicellular living, particularly involving complex regulatory mechanisms that attune a cell’s behavior to its circumstances and its neighbors. It is not surprising that sometimes these systems break down, and our cells return to a Hobbesian “state of nature.”

This doesn’t mean, however, that cancer is a simple story of “selfish individualism” in cells, pitched against “altruistic collectivism.” In 1962 David Smithers warned about the dangers of taking too reductionistic a view of cancer. It is, he said,

no more a disease of cells than a traffic jam is a disease of cars. A lifetime of study of the internal-combustion engine would not help anyone to understand our traffic problems. The causes of congestion can be many. A traffic jam is due to a failure of the normal relationship between driven cars and their environment and can occur whether they themselves are running normally or not.

Smithers dismissed efforts to explain this or indeed any aspect of organismal behavior on the basis of what goes on in an individual cell as “cytologism.” He would surely have been dismayed to see that logic pursued to an even more atomized degree by attributing all events to changes in the activity of specific genes.

The analogy of the traffic jam is perhaps even better than Smithers appreciated. For traffic jams can be triggered by a single individual doing something, such as braking too hard too suddenly. But it is doubtful whether this can be identified as the cause of the jam, because a jam will only result if it happens within the right (or wrong) context—in that case, if the density of traffic is above a certain threshold. Either way, the jam is a collective phenomenon that cannot be deduced or predicted from the behavior of a single driver. As Smithers put it, “Cancer is a disease of organization, not a disease of cells.” He argued that the key criterion for whether cancer develops is the organizational state of the tissue.

Some researchers, building on that view, have even called for an abandonment of the notion of a “cancer cell.” “Normal and cancer development,” argue biologists Carlos Sonnenschein and Ana Soto, “belong to the tissue level of biological organization.” This view is supported by recent research that reveals cancer not as a genetic disease but as a (problematic) change in development—that is, as a pathology of how cells build tissues.13 It would be quite wrong to view cancer cells as having capitulated to a kind of individualistic abandon, for they are still human cells, with all the regulatory equipment that entails, and are not as “selfish” as has often been implied. Cancer isn’t really a consequence of the uncontrolled proliferation of a rogue cell, but might be best seen as the growth of a new kind of tissue or organ.

In 2014 pathologist Brad Bernstein and his coworkers looked at brain tumors using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq; p. 242). What he found dismayed him: in any single tumor there is not one single type of cancer cell at work, but many. Recall that this technique shows us what is being transcribed in each individual cell in a sample, and thus which genomic regions within each cell are active. Here it revealed cancerous tumors as mosaics of different cell types—including plenty of nonmalignant “healthy cells” that have apparently been corralled into helping support the cancerous growth. Tumors are more like loosely structured organs than an undisciplined mass of replicating cells: a sort of deranged recapitulation of normal development.

This was not entirely news. Previous studies had seemed to suggest that one of four distinct types of cancer cells might be present in any given brain tumor, creating four different classes of tumor—each requiring a different kind of treatment. Bernstein’s single-cell analyses of a particularly malignant type of brain tumor called a glioblastoma, however, revealed that all four cell types were typically present in every tumor that he and his colleagues looked at—albeit in different proportions, so that only the dominant type would be seen if the tumor was studied as a whole.

These different cell types arise by differentiation of a kind of cancer “stem cell,” just as normal embryonic stem cells differentiate into distinct tissues. The difference is that tumor cells don’t quite make it to a mature, well-behaved state: they get stuck in a form that continues to proliferate. But they still have a plan of sorts, and it seems to be a developmental plan. It’s as if they “want” to be a kind of differentiated, multicellular tissue or organism—and moreover, one that interfaces seamlessly with the host organism. Some aspects of tumor development look like processes seen in developing organs; others look more akin to the way certain tissues such as blood vessels or bone can reorganize and rejuvenate themselves in response to other changes in the body.

In following these developmental paths, tumors may exploit the healthy cells around them. In a study of cancers of the head and neck, Bernstein and his colleagues learned that some tumors incorporate a high number of seemingly ordinary fibroblasts—connective tissue cells. Some tumors might just have just 5–10 percent of actual tumor cells; the rest are nonmalignant cells sitting in the tumor ecosystem. The tumors seem to be able to repurpose these cells for their own ends. Healthy epithelial cells, for example, can become reprogrammed into mobile mesenchymal cells that break free from the tumor and help the cancer disperse and spread through metastasis—making it very hard to treat. In another study, cancer biologist Moran Amit and his colleagues found that cancer cells can reprogram ordinary neurons so that they promote tumor growth.

Cancer cells are unusually plastic: they can transition back and forth between different states more readily than normal cells. The cells might differentiate a little bit and then revert, for example. Such reversibility and plasticity create challenges for therapies that target a single cell type, for the interchangeability of these states gives cancer cells an evasion strategy. On the other hand, this fluidity of state suggests a new and dramatic approach to treating cancer. Instead of simply trying to kill the tumor cells, it might be possible to “cure” them by guiding them gently back to a nonmalignant state—much as mature somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a stem-cell state (p. 259). This is called differentiation therapy, and some researchers are now hunting for chemical agents that can cause the switch. Some preliminary results for treating a particularly recalcitrant form of leukemia called APML (acute promyelocytic leukemia) this way have been encouraging.

Whether this strategy will pan out remains to be seen, but it’s a good example of the philosophy of treating disease at the right level of intervention: matching the solution to the problem. If cancer is at root a matter of cells falling into the “wrong” state—the wrong basin of attraction—perhaps the real goal is to get them back out again. That might have more in common with the kind of cell-state engineering involved in stem-cell research than with developing drugs against molecular targets. It’s about redirecting life itself to new destinations.

We mustn’t forget, however, the proviso that disease is a physiological state, and often not reducible to the level of molecules or even cells. As Polish oncologist Ewa Grzybowska points out, most cancer patients die not from the growth of the primary tumor but via the process of metastasis, in which the cancer spreads throughout the body. Metastasis generally kills because it disrupts the body’s vital physiological functions: “More and more elements of the whole system become faulty, and when the tipping point is achieved, the whole organism starts to shut down,” Grzybowska says. “Our approaches seem very crude: to eliminate tumor mass and to kill every tumor cell, even if it is very costly and causes collateral damage.” Perhaps, she suggests, the notion of causal emergence can help to better define new therapeutic targets at the level that matters most: where lower-level complications become transformed into higher-level breakdowns. It’s a question of finding the right perspective.

Thanks Wil. I completely agree with you of course and you would have noticed from a post or two I've circulated my pride in Western culture — I can't believe my luck as the heir of such a patrimony. And yes, it also brought us black chattel slavery. The historian John Lucaks wrote a book on the subject of the difference between patriotism (good) and nationalism which I recommend.

There's a lot of simple silliness about sadly, so I ignore most of it. It's a great pity that there was such a cultural vacuum that Billy Bragg felt the need to write a book about it. We're all proud of what we appreciate about the world we're part of — or we should be, and with that, keen to live up to the best values within it. And propagate and improve them.

Billy Bragg, who isn't one of the world's greatest thinkers, but whose values and ability to articulate a view I greatly appreciate, wrote a book a while ago called The Progressive Patriot. I found it useful to help me thinking through my patriotism towards Australia while avoiding nationalism and jingoism. In the modern world of identity politics this is a slightly challenging needle to thread, and not one that I'd usually discuss with my lefty friends, some of whom have fully bought into the official set of values that one must profess in order to be part of the In Group, allowing one to be derisive and snarky online.