A moment of truth

One has to admire the high-mindedness of the Lib/Lab Coalition to agree to tighter controls of electoral funding, but it seems that they’ve done so for their political competitors. Obviously not imposing the same disciplines on themselves was an administrative error which will not only be walked back but unwound and repositioned over the course of subsequent decades.

Be that as it may, this sets the scene for us to discover what the cross-bench is made of. Helen Haines, has already said that undoing these outrages will be a precondition of agreeing to support a government in the event of a hung parliament. Good on her. Presumably most if not all the other crossbenchers will follow suit. But how will they do that?

One way would be to keep things as they are, but with a better deal for the cross-bench. The other way would be to look for a solution which might institutionalise better behaviour. Ideally it would take such matters out of the hands of politicians or at least begin establishing the machinery that could do so over time — as I suggested a few weeks ago. In Michigan they’ve had a similar problem of self-dealing by the politicians — gerrymandering. Their response has been the Michigan Independent Citizens' Redistricting Commission, a body with 13 ordinary citizens chosen by lottery.1 It’s cleaned up gerrymandering.

Not only is that commission much harder to corrupt than it is to corrupt most government commissions (because their commissioners are appointed by government), but the Michigan operation is now one of the few pioneering examples of allotted bodies actually being built into the routines of governing in Western countries.

If the crossbench were to bring something like that about, well then as they retire they can all feel satisfied that they left behind something that institutionalised the spirit they told us they were bringing to the parliament. And their handiwork would even assist their mission as parliamentarians.

Insider dealing: Bernard Keane is not impressed

Always nice to see a bit of electoral funding reform. Naturally the major parties are largely exempt, but they’re playing the long game and no doubt they’ll lift their own game a few decades after they’ve fixed things for the other parties.

What a sordid mob this government is.

In 2022, Labor promised voters it would reform the awful Commonwealth political donation laws to require real-time disclosure of donations over $1,000. It was simple promise, to fix one of the worst elements of the current system, in which we can wait up to 18 months to find out who donated above $16,900.

At any time in the past nearly three years, Labor could have legislated that requirement. It would have passed easily with the support of the crossbench. Instead, Labor’s Don Farrell, special minister of state and long-time party powerbroker, made it his goal to use political funding reform to shore up Labor’s incumbency within the political system. Inevitably, to accomplish that, he needed the support of the other major party.

The result is a grubby deal between Labor and the Coalition that hands tens of millions more in taxpayer dollars to the major parties and attempts to lock in their incumbency. And we don’t even get real-time disclosure of donations over $1,000. Instead, the transparency-averse Liberals have demanded, and got, a $5,000 threshold from Farrell, to be disclosed monthly outside of election campaigns.

It’s all of a piece with a government that came to power promising to be materially better than its predecessor around transparency and integrity, but which has consistently preferred secrecy.

It also throws out the window one of the supposed core objectives of Albanese Labor, to demonstrate to voters that the political system can work in their favour, rather than those of vested interests. The major parties are two of the biggest vested interests of all, and the new regime will deliver for them and undercut their independent competitors. If we were talking about corporations, it’d be a colossal breach of competition law. …

All of this has proceeded in the absence of any proper inquiry into how the legislation’s mix of donation and spending caps will operate, or the opportunity for the public and independent experts to have their say via a Senate inquiry process. Oddly enough, Farrell was happy to use the traditional post-election Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters inquiry into the 2022 election as an excuse for refusing to progress Labor’s election commitment for much of this parliamentary term. Suddenly, Farrell found parliamentary inquiries no longer to his taste when he had his own stitch-up to progress. …

Australia needs another big, 2022-style slump in the level of support for major parties to break a political business model nakedly serving only the interests of Labor and the Coalition, and the unions and businesses that support them.

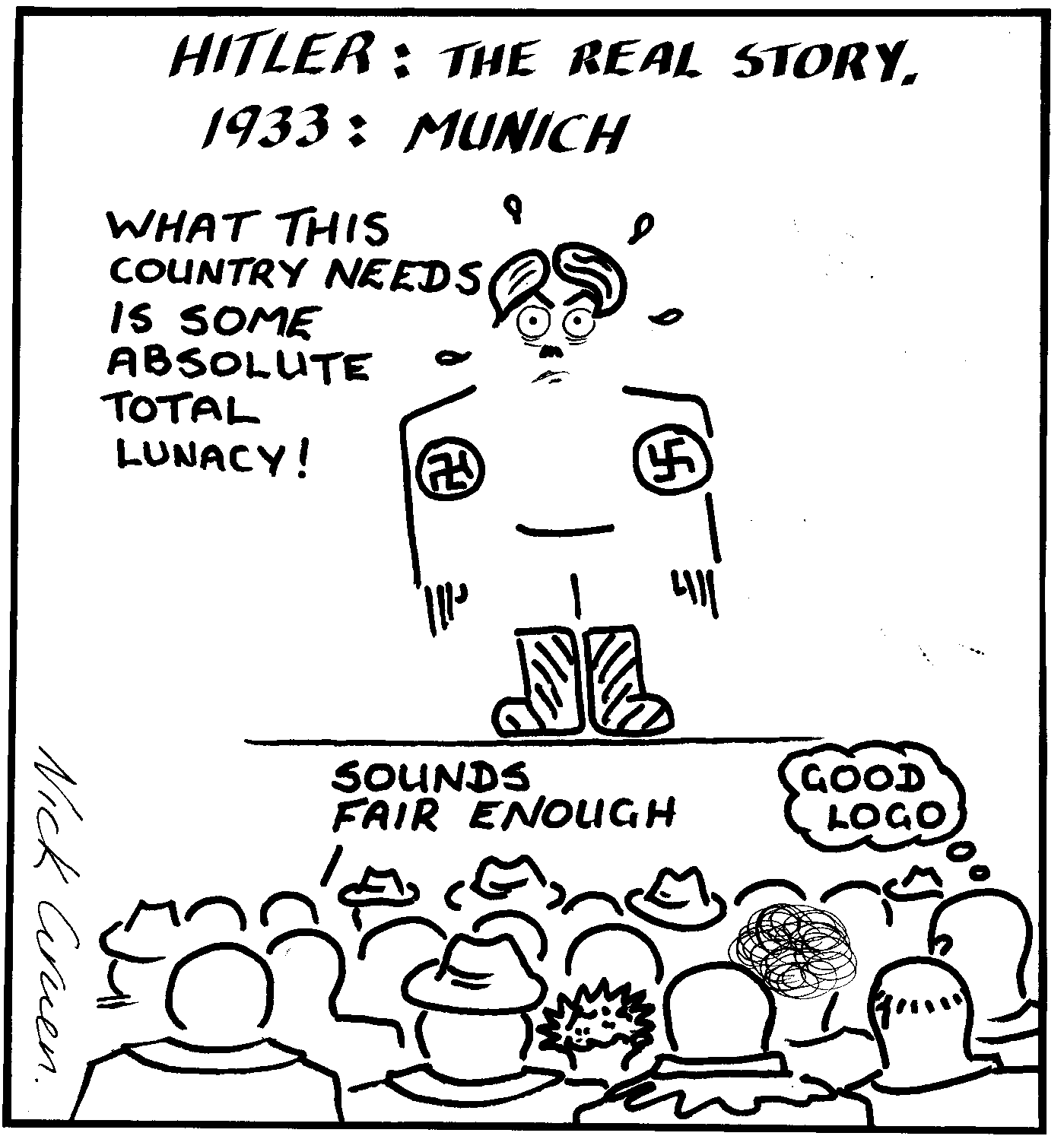

The more things change, the more controversial the salutes get

Great fun

Childbirth and Firm Performance: Evidence from Norwegian Entrepreneurs

John Bonney, Luigi Pistaferri, and Alessandra Voena #33448

Using multiple administrative data sources from Norway, we examine how firm performance changes after entrepreneurs become parents. Female-owned businesses experience a substantial decline in profits, steadily decreasing to 30% below baseline ten years post-childbirth. In contrast, male-owned businesses show no decline, often growing in revenues and costs after childbirth. The profit decline for female-owned firms is most pronounced among highly capable entrepreneurs, women who are majority owners, and those with working spouses. Entrepreneurial effort is key to performance, and our findings suggest that time demands from childbirth and childcare are a significant determinant of the decline in firm profits.

Firm Pay and Worker Search

Sydnee Caldwell, Ingrid Haegele, and Jörg Heining #33445Whether and how workers search on the job depends on their beliefs about pay and working conditions in other firms. Yet little is known about workers' knowledge of outside pay. We use a large-scale survey of full-time German workers, linked to their Social Security records, to elicit pay expectations and preferences over specific outside firms. Workers believe that they face considerable heterogeneity in their outside pay options, and direct their search toward firms they believe would pay them more. Workers' expected firm-specific pay premia are highly correlated with pay policies observed in administrative records and with workers' valuations of firm-specific amenities. Most workers are unwilling to search for a new job—or leave their current firm—even for substantial pay increases. Switching costs are equivalent to 7 to 18% of a worker’s annual pay. Attachment varies across firms, and cannot be explained by either differences in firm-specific amenities or switching costs.

HT: Reader George

Digging in an Italian vineyard

Monogamy: pining for the fiords in China too!

From the indefatigable documenter of relationships worldwide:

China’s marriages have hit rock bottom - only 6.1 million weddings in 2024. This has massive economic consequences - fewer marriages mean mean fewer births, an ageing population, with declining labour productivity, and a rising dependency burden.

Bloomberg blames marital collapse on economic hardship. But my interviews with Chinese young people suggest three further drivers.

Cultural liberalisation means singledom is more permissible, while status is tied to economic success;

Online connectivity enables young women to celebrate independence & equality;

Men and women seem to be retreating into digital worlds.

This isn’t just about empty pockets - it echoes a global pattern of shifting aspirations and the rise of solitude.

Let’s dig in to the data on what’s driving China's demographic crisis.

The Greta Garbo civilisation

A scary interview. What if there isn’t a loneliness epidemic so much as an aloneness epidemic. In other words, what if people don’t want to be with other people. What if it’s too much trouble. It’s nice that, given his newfound purchase on the problem the journalist interviewed is trying to do something about it. But that’s individually. But it’s also a collective problem. And there are things that can be done collectively at very low cost about the leaching away of the life world. Like this.

A strange and sad story

From the Newyorker mailout.

As Janet Malcolm worked on “Trouble in the Archives,” a two-part piece about prominent psychoanalysts who disagreed about Freud, she began a correspondence with Kurt Eissler, the head of the Sigmund Freud Archives. Perhaps no journalist has ever been so attentive to the emotional dynamics in the encounter between writer and subject, the transferences that obscure our ability to take in the reality of a relationship. Malcolm often coolly described the aftermath of such projections, but drafts of her letters to Eissler, preserved in Yale’s archives, capture an experience of escalating intimacy. She had planned for her piece to center on Jeffrey Masson, an unorthodox Freudian scholar who had become Eissler’s nemesis. But, in a letter to Eissler written toward the end of 1982, she said she now felt that “the animating consciousness should be yours. To put it bluntly, I find you more interesting than Masson.”

They began to have evening conversations, often at Eissler’s apartment. “I am less and less aware that you are working for a publication,” Eissler wrote her. Five days later, he observed, “It’s so rare that one feels free to talk more or less without inhibition to somebody and has the feeling the other party does the same.” Professional considerations did not diminish “the charm + beauty of the ‘event’ for it is an event for me,” he wrote.

Malcolm seemed similarly carried away. “I would frankly rather give up the whole project than cause you distress,” she wrote. Her letters were exuberant, tender, and sometimes mischievous. Once, she described how Masson had slept over at her house and, when he came down for breakfast in the morning, criticized one of Eissler’s books. Then she wondered about “my motives in gratuitously reporting to you Masson’s reaction. . . . How perverse we all are! The last thing in the world I would have wanted was to give you cause ‘to complain’ about me.”

Both Eissler and Malcolm seemed to worry that there was something inappropriate about the “personal glow,” as Eissler put it, of their correspondence. “Your mind is too penetrating for my liking,” he wrote. Later, he announced, “I shall have to make an unpleasant decision during the next few hours or days, namely whether I should continue to write you letters of this kind.” By the next sentence, he seemed to have reached his decision: the correspondence could continue, if it was for a “limited duration. The gods do not grant us joy for a long time, they are right we get so quickly spoiled.”

Shortly before the piece was published, Malcolm wrote Eissler that she was in a “terrible bind about this. Although the piece is what brought us together, I fear that it is what will tear us apart.” Eissler assured her that, even if she wrote about him in a “mildly evil way, I still would think of you with gratitude and appreciation in my heart.”

In the article, published at the end of 1983, Malcolm describes Eissler’s “singular mixture of brilliance, profundity, originality, and moral beauty on the one hand, and willfulness, stubbornness, impetuosity, and maddening guilelessness on the other.”

A few weeks after the piece came out, Eissler sent back a book by Jorge Luis Borges that Malcom had given him. “Should I interpret the return of my book as a tidying up of loose ends at the end of a relationship, or should I see it as a sign of your continuing friendliness and good will?” she asked in a letter. It appears that the first interpretation was more accurate. Four days later, he wrote that he was dismayed by some of the details her piece had divulged. “I decided to terminate our relationship,” he wrote.

Malcolm wrote to Eissler that she had recently defended him in public when someone accused him of moral lapses: “I had never intended to tell you about it, but your harsh and implacable letter has made me feel somewhat bitter, and caused me to wonder whether my loyalty to you isn’t a little ridiculous.”

Reading the letters, I felt as if I were accessing secrets about Malcolm’s reporting, perhaps even a romantic drama never before revealed, but in fact I wasn’t discovering anything that she hadn’t already articulated. “A correspondence is a kind of love affair . . . tinged by a subtle but palpable eroticism,” she wrote in “The Journalist and the Murderer,” published six years later. “It is with our own epistolary persona that we fall in love, rather than with that of our pen pal.”

Musa al-Gharbi: on elites and wokeness

I’d noticed this guy, but not taken any time to take him in. I had imagined it was a right wing rant against wokeism. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. But there’s not that much right about it either. It’s certainly pretty predictable. Anyway, Martin Turkis gave it a rave review and I’m two chapters in. Expect to hear some more from me. This is a good discussion, even though I found the guest’s manner a little off-putting. The discussion really starts hitting its stride towards the end of the public part of the podcast. (And I don’t have a subscription so I’ve not listened to the rest.)

How far can Trumpism go without integrity?

Venkatesh Rao has a style that I find somewhat cultish. Still, I don’t think that’s affectation and it’s more a generational thing. More people find him compelling than find me compelling, so there. And it has to be admitted, my taste for new cultural references is a bit thin. I don’t much go for Star Wars, Star Treck or even Lord of the Rings metaphors. I positively dislike Matrix metaphors and, though I’ve learned which is the red and which is the blue pill, it’s a matter of perverse and self-sabotaging pride that I can never remember which is which. I do know there’s no green pill, but can’t help wondering what it does.

In any event, his argument in this piece seems right to me. A social formation which does not invite integrity will degrade. Elon’s adventure might have some good things about it, though I suspect that’s overdone — time will give us more information and more perspective. But without cultivating the speaking of truth to power — what the Greeks called parrhesia — you’ll start sinking after the initial cleaning of the augean stables is done.

He offers Boyd’s Razor:

If your boss demands loyalty, give them integrity instead.

If your boss values integrity, then give them loyalty in return.

… Loyalty-testing (which is the Right-Authoritarian version of doctrinal purity-testing in the Left-Authoritarian sense) is absolutely central to how they operate. It is the biggest shared element of leadership philosophy between Musk and Trump.

In the short term, ignoring Boyd’s razor makes the Boydian playbook radically easier and cheaper to implement. It just degenerates to “operate at a faster tempo” or some such over-simplification. But in the long term, ignoring Boyd’s razor creates a closed-off intellectual monoculture within the entity deploying Boydian strategies. …

Integrity is very easy to kill in a culture. You can simply tag people who dissent as traitors and fire them. You can intimidate people into loyalty. You can rope in the energies of a certain breed of extremely high-energy, high-IQ, but low-orientation grinder who will willingly pull all-nighters, put in 100-hour-weeks for years on end, and even go on suicide missions for you, either because they lack the aptitude for the moral reasoning Boyd’s Razor calls for, or are too young to have cultivated it, since it develops through morally demanding decision-making experience rather than smarts.

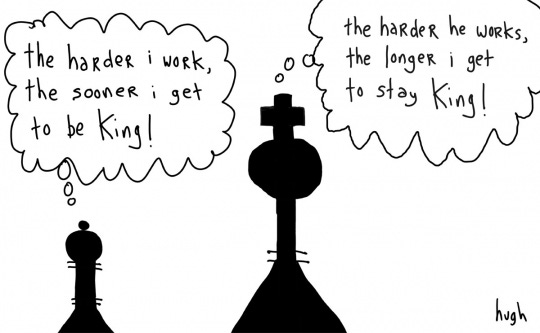

Why do people like Musk and Trump operate this way? It’s King logic, the essence of monarchist tendencies, as illustrated in this classic Gaping Void cartoon [above]: Boyd’s razor is the moral compass of Boydian theory, and monarchism is mostly about throwing it away by becoming a solipsistic self-certifier of your own truths. So loyalty becomes the same thing as truth, and integrity becomes a meaningless concept, since it can only exist in a pluralist context, where sometimes you give others the benefit of doubt rather than yourself. The pawn in this picture will never ever stop to ponder a loyalty/integrity question because they’ve surrendered that moral agency to the king. That is why they can work mindlessly hard with a “maniacal sense of urgency.”

Without Boyd’s Razor, you may win early battles with Boydian strategy, but you will descend into paranoia and increasingly vicious monocultural extremism and excess as you attempt to consolidate your position.

I’m no fan of what Musk-Trump are doing, so I’m happy they are ignoring Boyd’s Razor (and on a massive scale — their entire supply chain of talent is gated primarily by loyalty testing) and setting themselves up for eventual failure.

Respecting Boyd’s razor from Day 1 slows you down, and is generally costly — Boyd himself respected it absolutely, in how he treated both his own commanding officers and acolytes, and paid a heavy price for it. The better-known Boydian “do something/be somebody” fork is downstream of Boyd’s razor. The do/be choice only ever presents itself if you first navigate the loyalty/integrity moral maze successfully.

But paying the cost of following Boyd’s Razor buys you something. It builds up defensible positions steadily over time because it catalyzes pluralism, dissent, and openness to novel ideas. It fuels truth-seeking instincts rather than truth-manufacturing instincts. It prioritizes outcomes over theaters of appearance. It expands your coalition by learning from others, even adversaries, and co-opting them, rather than shrinking it into a cult. It allows you to keep the complete cycle of creative destruction going.

By contrast, ignoring Boyd’s Razor sends you down an intellectual cul-de-sac. The associated paradigm, no matter how powerful, eventually exhausts itself. Aside: this is why Musk’s “first principles thinking” is a fragile and questionable epistemic posture even when practiced sincerely. In complex systems, especially social ones, to keep things generative, you eventually have to deprecate some existing “first principles” and add new ones. And the main way you do that is by listening to high-integrity people whom you don’t immediately behead for disloyalty if they disagree with you. …

It is useful to contrast Musk with Steve Jobs, whom he is often compared to. Jobs too had an autocratic, bullying personality. But he appears to have respected Boyd’s Razor. One senior executive who was close to him said that the way to succeed at Apple was “do the right thing, and make Steve happy.” In Jobs’ world, there was room for integrity to survive. Room for you to try and do your idea of “the right thing.” In Musk’s world, the razor has apparently degenerated to “Just make Elon happy; he knows what the right thing to do is.” (though it wasn’t always this way).

And it’s not about whether or not people can withstand autocratic, scary bosses who demand a lot and practice a sadistic management style. In many ways, Jobs was worse than Musk, for example in imposing a very secretive need-to-know communication culture instead of an open flow (10 points to Musk on that front). It’s about whether or not you can hold the excruciating moral tension of Boyd’s razor in your head. Jobs could. As far as I can tell, Musk cannot.

What truly burns people out is not that their boss is too demanding, hot-tempered, or even sadistic. What burns people out is not being allowed to exercise their integrity instincts. Being asked to turn off or delegate their moral compass to others. Plenty of people have the courage, the desperation, the ambition, or all three, to deal with demanding and scary bosses. But not many people can indefinitely suspend integrity instincts without being traumatized and burning out. …

And finally, to connect all this to my current obsession, steppe nomad culture, the difference between Genghis Khan and Timur, and the reason the former left behind a relatively long-lasting 3-generation empire (even if in multiple shards) while the latter’s empire unraveled immediately, is that Genghis respected Boyd’s Razor and Timur did not.

Boyd’s Razor is going to slit the throat of many otherwise brilliant strategists who don’t think a costly moral compass that prices integrity over loyalty is worth paying for and installing into your operations.

They will deserve it.

Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious.

An extract from Ross Douthat’s newly-released book.

In the final season of The Sopranos, a season that begins with Tony Soprano having an extended near-death experience, Paulie Gualtiere, one of Tony’s capos and the show’s most superstitious character, confesses to his boss that he once had a vision of the Virgin Mary in the Jersey mob’s strip club, the Bada Bing. Tony doesn’t tell Paulie that it was just a hallucination or that the Queen of Heaven wasn’t really there; he just stresses—mobster to mobster, murderer to murderer—that Paulie shouldn’t let it get in the way of his everyday obligations.

“I’m not saying there’s nothing out there,” he says. “But you gotta live your life.” …

In this spirit, one can imagine a reader conceding a great deal to my sketch of the human situation—acknowledging the appearances of order and design, the deep mystery of consciousness, the peculiarly privileged-seeming position of human beings in the cosmos, the resilience of mystical experiences and seemingly supernatural happenings—and still circling back around to … Tony telling his friend not to lose sleep over the unknowable.

This is why I’m trying to emphasize the convergence of different forms of evidence, not a single line of argument alone. For my own part I think that the default to helplessness is mistaken no matter what. … If a vision of transcendent goodness and mercy appears to you, a sinner, and you don’t understand what it means, the most obvious interpretation is that you gotta change your life.

But you don’t have to agree with me, because the world doesn’t ask you to make a leap toward faith or belief based on just a single prompting—one potential resurrection, one apparent limit on scientific certainty, one strip-club supernatural vision. Rather it offers multiple prompts, multiple indicators, converging and overlapping and all pointing the human intellect in a similar direction—with strong indications of cosmic order and design and a strong possibility of human significance within that order and good reasons to think that we can reach up toward the supernatural even as the supernatural reaches out or down to us. …

If mind might well precede matter, and the laws of the universe indicate that some intelligence created and sustains existence, and human reason seems to have a privileged ability to unlock existence’s mysterious underlying order, and the seemingly supernatural intrudes upon the natural as often in the modern world as in the past—well, then, you, as a man or a woman trying to chart the best course through a finite lifespan, with difficult moral choices at every turn and death awaiting sooner rather than later, have every reason to take pretty strong interest in the story you’ve found yourself inside, what part you might be asked to play in it, and how, for you and everyone, it might ultimately end.

And as it happens there exists in our world civilization, as in every prior human civilization worthy of the name, a vast body of personal writing and reporting and theorizing and argument on exactly these pretty-damn-important matters. There exists a substantial set of practices and rituals and wisdom literatures that are supposed to align human consciousness with cosmic purpose, that claim to help unite the individual human story with the larger drama, and to make sure that your soul is both prepared for that potentially cracked door at the conclusion of your life and protected from forces that might not want you to successfully pass through.

All of this religion offers—right now, today, as you read these words. Once you concede that the universe might be a bit more than just a collision of atoms doing meaningless expansions and contractions, you are not standing alone next to an enigmatic aurochs, staring with bafflement into its inhuman eyes. No, you are standing in the same place that generations of human beings have found themselves before: at the beginning of a journey, a quest, a pilgrim’s progress, that you have good reason to believe is going somewhere quite important, somewhere of ultimate significance. And the choice this book is concerned with, the choice to become religious or not, is fundamentally a choice between looking around at the piled-up knapsacks and guidebooks that prior pilgrims have carried and used and written, and deciding to see what they might have to offer—or just wandering onward, willfully blind without a compass or a map.

Overheads on research

A guardedly optimistic story if true

The unbearable lightness of blandout

Not the kind of thing I watch on YouTube — but more fool me. I found it great food for thought about many things other than filmmaking.

HT Gene Tunny for sending it to me.

Cruel but fair

OK — I have to be able to publish dumb pet videos sometimes

The best of BBC Radio 4

I’m working with someone in the BBC on a documentary on the other way to do democracy. In any event we’re preparing for a funding round and he sent me the guide for those pitching. Why am I telling you. Well, I found it an intriguing look into how they commission and the broadcasting values implicit in the process. But I’m reproducing it here because you can scan it as I did for the greatest hits of BBC Radio 4. All the ones I looked for were available online. The document is here.

Heaviosity half-hour

Husserl (Yay!) v Heidegger (Boo!)

As a reader of this newsletter, you’ll be familiar with the rules of Heaviosity half-hour. A substantial passage or series of passages are quoted. They have to be about philosophers no-one understands (or at least I don’t understand) which means they’re likely to be Germans. And their surnames have to start with “H”.

To maintain their relevance to the accelerationist tastes of young folk today, there must also be a World War, goodies — wearing white — and baddies — wearing black with red and white armbands and given to occasional controversial movements of their right arm (though barracking is discouraged). And a car chase.

It can’t have escaped your notice that these conditions are so onerous that they’ve not yet been met in full.

Until now.

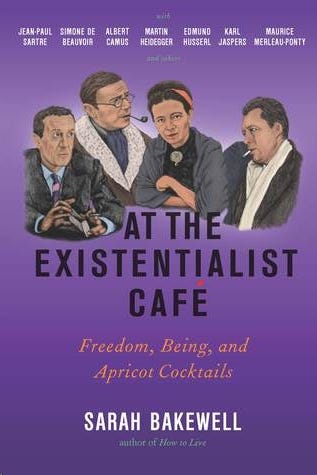

From Chapter 6 of At the Existentialist Cafe

A few days later, the European crisis was resolved — temporarily. Benito Mussolini brokered a meeting in Munich on 29 September, attended by Hitler, Daladier and Chamberlain. No one from Czechoslovakia was in the room when, in the early hours of 30 September, Daladier and Chamberlain caved in to Hitler’s increased demands. The next day, German forces entered the Sudetenland.

Chamberlain flew back to Britain triumphant; Daladier flew back to France ashamed and full of dread. Greeted by a cheering crowd as he got off the plane, he reportedly muttered, ‘Les cons!’ — the idiots! — at least that was the story Sartre seems to have heard. Once the initial relief passed, many in both France and Britain doubted that the agreement could last. Sartre and Merleau-Ponty were pessimistic; Beauvoir preferred to hope that peace might prevail. The three of them debated the matter at length.

As a side effect, the peace deal reduced the urgency about getting Husserl’s papers out of Germany. It was not until November 1938 that the bulk of them were transported from Berlin to Louvain. When they arrived, they were installed in the university library, which proudly organised a display. No one could know that in two years’ time the German army would invade Belgium and the documents would be in danger again.

That November, Van Breda returned to Freiburg. Malvine Husserl had now decided to seek a visa so as to join her son and daughter in the US, but this took a long time, so in the meantime Van Breda arranged for her to move to Belgium. She arrived in Louvain in June 1939, joining Fink and Landgrebe, who had moved there in the spring and were getting to work. With her came a huge cargo: a container of her furniture, the full Husserl library in sixty boxes, her husband’s ashes in an urn, and a portrait of him, which Franz Brentano and his wife Ida von Lieben had jointly painted as an engagement present before the Husserls’ marriage.

Brentano’s papers — still stored in an archive office in Prague — had meanwhile been through their own adventure. When Hitler moved on from the Sudetenland to occupy the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, a group of archivists and scholars gathered most of them and spirited them out of the country on the very last civilian plane to leave. The papers ended up in the Houghton Library at Harvard University, and are still there today. The few files left behind were defenestrated through the office window by German soldiers, and mostly lost.

The Husserl archives survived the war and are mostly still in Louvain, with his library. They have kept researchers busy for over seventy-five years, and have generated a collected edition under the title Husserliana. So far, this comprises forty-two volumes of collected works, nine volumes of extra ‘materials’, thirty-four volumes of miscellaneous documents and correspondence, and thirteen volumes of official English translations.

One of the first to travel to Louvain to see the archive was Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who already knew Husserl’s earlier work well, and had read about the unpublished manuscripts in an article in the Revue internationale de philosophie. In March 1939, he wrote to arrange a visit to Father Van Breda so as to pursue his special interest in the phenomenology of perception. Van Breda welcomed him, and Merleau-Ponty spent a blissful first week of April in Louvain, absorbed in the unedited and unpublished sections which Husserl had intended to add to Ideas and to The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology.

These late works of Husserl’s are different in spirit from the earlier ones. To Merleau-Ponty, they suggested that Husserl had begun moving away from his inward, idealist interpretation of phenomenology in his last years, towards a less isolated picture of how one exists in a world alongside other people and immersed in sensory experience. Merleau-Ponty even wondered whether Husserl had absorbed some of this from Heidegger — an interpretation with which not everyone agrees. Other influences might be seen too: from sociology, and perhaps from Jakob von Uexküll’s studies of how different species experience their ‘environment’ or Umwelt. Whatever the source, Husserl’s new thinking included reflections on what he called the Lebenswelt, or ‘life-world’ — that barely noticed social, historical and physical context in which all our activities take place, and which we generally take for granted. Even our bodies rarely require conscious attention, yet a sense of being embodied is part of almost every experience we have. As I move around or reach out to grasp something, I sense my own limbs and the arrangement of my physical self in the world. I feel my hands and feet from within; I don’t have to look in a mirror to see how they are positioned. This is known as ‘proprioception’ — the perception of self — and it is an important aspect of experience which I tend to notice only when something goes wrong with it. When I encounter others, says Husserl, I also recognise them implicitly as beings who have ‘their personal surrounding world, oriented around their living bodies’. Body, life-world, proprioception and social context are all integrated into the texture of worldly being.

One can see why Merleau-Ponty saw signs of Heidegger’s philosophy of Being-in-the-world in this new interest of Husserl’s. There were other connections too: Husserl’s late works show him considering the long processes of culture and history, just as Heidegger did. But here there is a great difference between them. Heidegger’s writings on the history of Being are suffused with a longing for some home time, a lost age or place to which philosophy should be traced, and from which it should be renewed. Heidegger’s dream-home often calls to mind the forested Germanic world of his childhood, with its craftsmanship and silent wisdom. At other times, it evokes archaic Greek culture, which he considered the last period in which humanity had philosophised properly. Heidegger was not alone in being fascinated by Greece; it was a sort of mania among Germans at the time. But other German thinkers often focused on the flowering of philosophy and scholarship in the fourth century BC, the time of Socrates and Plato, whereas Heidegger saw that as the period in which everything had started going wrong. For him, the philosophers who truly connected with Being were pre-Socratics such as Heraclitus, Parmenides and Anaximander. In any case, what Heidegger’s writings on Germany and Greece share is the mood of someone yearning to go back into the deep forest, into childhood innocence and into the dark waters from which the first swirling chords of thought had stirred. Back — back to a time when societies were simple, profound and poetic.

Husserl did not look for such a simple lost world. When he wrote about history, he was drawn to more sophisticated periods, especially those when cultures were encountering each other through travel, migration, exploration or trade. At such periods, he wrote, people living in one culture or ‘home-world’ (Heimwelt) meet people from an ‘alien-world’ (Fremdwelt). To those others, theirs is the home-world and the other is the alien-world. The shock of encounter is mutual, and it wakes each culture up to an amazing discovery: that their world is not beyond question. A travelling Greek discovers that the Greek life-world is just a Greek world, and that there are Indian and African worlds too. In seeing this, members of each culture may come to understand that they are, in general, ‘worlded’ beings, who should not take anything for granted.

For Husserl, therefore, cross-cultural encounters are generally good, because they stimulate people to self-questioning. He suspected that philosophy started in ancient Greece not, as Heidegger would imagine, because the Greeks had a deep, inward-looking relationship with their Being, but because they were a trading people (albeit sometimes a warlike one) who constantly came across alien-worlds of all kinds.

This difference highlights a deeper contrast of attitude between Husserl and Heidegger in the 1930s. During that decade’s events, Heidegger turned increasingly to the archaic, provincial and inward-looking, as prefigured by his article about not going to Berlin. In response to the same events, Husserl turned outwards. He wrote about his life-worlds in a cosmopolitan spirit — and this at a time when ‘cosmopolitan’ was becoming recast as an insult, often interpreted as code for ‘Jewish’. He was isolated in Freiburg, yet he used his last few talks of the 1930s, in Vienna and Prague, to issue a rousing call to the international scholarly community. Seeing the social and intellectual ‘crisis’ around him, he urged them to work together against the rise of irrationalism and mysticism, and against the cult of the merely local, in order to rescue the Enlightenment spirit of shared reason and free inquiry. He did not expect anyone to return to an innocent belief in rationalism, but he did argue that Europeans must protect reason, for if that was lost, the continent and the wider cultural world would be lost with it.

In his 1933 essay ‘On the Ontological Mystery’, Gabriel Marcel provided a beautiful image that sums up Husserl’s view of what ‘alien’ encounters and international mingling can do for us. He wrote:

I know by my own experience how, from a stranger met by chance, there may come an irresistible appeal which overturns the habitual perspectives just as a gust of wind might tumble down the panels of a stage set — what had seemed near becomes infinitely remote and what had seemed distant seems to be close.

A tumbling of stage sets and abrupt readjustment of perspectives characterise many of the surprise encounters seen so far in this book: Heidegger’s boyhood discovery of Brentano, Levinas’ discovery of Husserl in Strasbourg, Sartre’s discovery of Husserl (and Levinas) via Raymond Aron at the Bec-de-Gaz — with more to come. Merleau-Ponty’s 1939 discovery of Husserl’s late work was among the most fruitful of these moments of discovery. Largely out of that single week of reading in Louvain, he would develop his own own subtle and rich philosophy of human embodiment and social experience. His work, in turn, would influence generations of scientists and thinkers to this day, linking them to Husserl.

Husserl had perfectly understood the value to posterity of his unpublished works, unfinished, chaotic and barely legible though they were. He wrote to a friend in 1931, ‘the largest and, as I actually believe, most important part of my life’s work still lies in my manuscripts, scarcely manageable because of their volume’. The Nachlass was almost a life form in itself: the biographer Rüdiger Safranski has compared it to the giant conscious sea in Stanislaw Lem’s science-fiction novel Solaris. The comparison holds up well, since Lem’s sea communicates by evoking ideas and images in the minds of humans who come close to it. Husserl’s archive exerted its influence in much the same way.

The whole hoard would have been lost without the heroism and energy of Father Van Breda. It would never have existed at all had Husserl not persisted in refining and developing his ideas long after many thought he had simply retired and gone into hiding. Moreover, none of it would have survived without a bit of sheer luck: a reminder of the role contingency plays in even the most well-managed human affairs.

From Chapter 13: Having once tasted phenomenology

One philosopher who had expected to die of a heart attack at a young age, but did not, was Karl Jaspers. On marrying, he had warned Gertrud that they could not expect long together, perhaps a year or so. In fact, he lived to eighty-six, and died on 26 February 1969 — Gertrud’s birthday. Heidegger sent her a telegram afterwards with the simple words: ‘In remembrance of earlier years, in honor and sympathy.’ She wrote back on the same day, ‘Thinking likewise of the earlier years, I thank you.’ She lived until 1974.

Perhaps the best way to mark Karl Jaspers’ passing is to revisit a radio talk he gave about his life, as part of a series in 1966–7. He spoke of his childhood by the North Sea, and especially about holidays with his parents in the Friesian islands. On the island of Norderney one evening, his father took his hand as they walked to the water’s edge. ‘The tide was out, our path across the fresh, clean sand was amazing, unforgettable for me, always further, always further, the water was so low, and we came to the water, there lay the jellyfish, the starfish — I was bewitched,’ said Jaspers. From then on, the sea always made him think of the scope of life itself, with nothing firm or whole, and everything in perpetual motion. ‘All that is solid, all that is gloriously ordered, having a home, being sheltered: absolutely necessary! But the fact that there is this other, the infinity of the ocean — that liberates us.’ This, Jaspers went on, was what philosophy meant to him. It meant going beyond what was solid and motionless, towards that larger seascape where everything was in motion, with ‘no ground anywhere’. It was why philosophy had always, for him, meant a ‘different thinking’.

Seven months after the death of Jaspers came that of another philosopher who had written about human life as a constant journey beyond the familiar: Gabriel Marcel, who died on 8 October 1973. For him, as for Jaspers, human beings were essentially vagabonds. We can never own anything, and we never truly settle anywhere, even if we stay in one place all our lives. As the title of one of his essay collections has it, we are always Homo viator — Man the Traveller.

Hannah Arendt died of a heart attack on 4 December 1975, aged sixty-nine, leaving a manuscript of Sartrean dimensions which her friend Mary McCarthy edited for posthumous publication as The Life of the Mind. Arendt never quite resolved the puzzle of Heidegger. Sometimes she condemned her former lover and tutor; at other times she worked to rehabilitate his reputation or to help people understand him. She met him a few times when she visited Europe, and tried (but failed) to help him and Elfride sell the manuscript of Being and Time in America to raise cash. Elements of his work always remained central to her own philosophy.

In 1969, she wrote an essay which was published two years later in the New York Review of Books as ‘Martin Heidegger at Eighty’. There, she reminded a new generation of readers of the excitement his call to thinking had generated, back in the ‘foggy hole’ of Marburg in the 1920s. Yet she also asked how he could have failed to think appropriately himself in 1933 and thereafter. She had no answer to her own question. Just as Jaspers had once let Heidegger off lightly by calling him a ‘dreaming boy’, so Arendt now ended her assessment with an overgenerous image: that of the Greek philosopher Thales, an unworldly genius, who fell into a well because he was too busy looking at the stars to see the danger in front of him.

Heidegger himself, although seventeen years older than Arendt, outlived her by five months, before dying peacefully in his sleep on 26 May 1976, aged eighty-six.

For over forty years, he had nursed his belief that the world had treated him badly. He had continued to fail to respond to his followers’ hopes that he would one day condemn Nazism in unambiguous terms. He acted as though he was unaware of what people needed to hear, yet his friend Heinrich Wiegand Petzet reported that Heidegger knew very well what was expected: it just made him feel more misunderstood.

He did not let his resentments put him off his work, which continued to lead him up and down the mountain pathways of his thoughts in his late years. He spent as much time as possible at Todtnauberg, receiving visits from pilgrims and sometimes from more critical visitors. One such encounter was with the Jewish poet and concentration-camp survivor Paul Celan, who gave a reading in Freiburg in July 1967 while on temporary release from a psychiatric clinic. The venue was the same auditorium where Heidegger had given his Nazi rectorial address.

Heidegger, who admired Celan’s work, tried to make him feel welcome in Freiburg. He even asked a book-dealer friend to go around all the bookshops in the city making sure they put Celan titles in their windows so the poet would see them as he walked through town. This is a touching story, especially as it is the single documented example I have come across of Heidegger actually doing something nice. He attended the reading, and the next day took Celan up to the hut. The poet signed the guest book, and wrote a wary, enigmatic poem about the visit, called simply ‘Todtnauberg’.

Heidegger liked receiving travellers, but had never been a Homo viator himself. He was disdainful about mass tourism, which he considered symptomatic of the modern ‘desert-like’ way of being, with its demand for novelty. In later life, however, he became fond of taking holidays in Provence. He agonised over the question of whether he should visit Greece — an obvious destination, given his long obsession with its temples, its rocky outcrops, and its Heraclitus and Parmenides and Sophocles. But that was why he was nervous: too much was at stake. In 1955, he arranged to go with his friend Erhard Kästner. Train and boat tickets were booked, but at the last minute Heidegger cancelled. Five years later the two men planned another trip, and again Heidegger pulled out. He wrote to warn Kästner that this was probably how things would go on. ‘I will be allowed to think certain things about Greece without seeing the country … The necessary concentration is best found at home.’

In the end, he did go. He took an Aegean cruise in 1962, with Elfride and a friend called Ludwig Helmken — a lawyer and politician of the centre right who had a past at least as embarrassing as Heidegger’s, since he’d joined the Nazi Party in 1937. Their cruise sailed from Venice down the Adriatic, and then took in Olympia, Mycenae, Heraklion, Rhodes, Delos, Athens and Delphi, before returning to Italy.

At first, Heidegger’s fears were confirmed: nothing in Greece satisfied him. Olympia had turned into a mass of ‘hotels for the American tourists’, he wrote in his notebook. Its landscape failed to ‘set free the Greek element of the land, of its sea and its sky’. Crete and Rhodes were little better. Rather than traipse around in a herd of holiday makers, he became more inclined to stay on the boat reading Heraclitus. He hated his first glimpse of smoggy Athens, although he enjoyed being driven by a friend up to the Acropolis in the early morning before the crowds arrived with their cameras.

Later, after lunch and a folk-dance performance at the hotel, they went to the Temple of Poseidon on Cape Sounion — and at last Heidegger found the Greece he was looking for. Gleaming white ruins stood firm on the headland; the bare rock of the cape lifted the temple towards the sky. Heidegger noted how ‘this single gesture of the land suggests the invisible nearness of the divine’, then observed that, even though the Greeks were great navigators, they ‘knew how to inhabit and demarcate the world against the barbarous’. Even now, surrounded by sea, Heidegger’s thoughts naturally turned to imagery of enclosing, bounding and holding in. He never thought of Greece in terms of trade and openness, as Husserl had done. He also continued to be annoyed by the encroachments of the modern world, with the other tourists’ infernal clicking cameras.

Reading Heidegger’s account of the cruise, we get a glimpse of how he responded when the world failed to fit his preconceptions. He sounds resentful, and selective in what he is prepared to see. When Greece surprises him, he writes himself further into his private vision of things; when it fits that vision, he cautiously grants approval. He was right to have been nervous of making the trip: it did not bring out the best in him.

There was one other late moment of surprise and beauty. As the ship sailed out of the bay of Dubrovnik on its way back to Italy, a pod of dolphins swam up at sunset to play around the ship. Heidegger was enchanted. He recalled a cup he had seen in Munich’s museum of antiquities, attributed to Exekias and dating from around 530 BC, on the sides of which Dionysus was depicted sailing on a vessel entwined with grapevines as dolphins cavorted in the sea. Heidegger rushed for his notebook — but as he wrote about the image, the usual language of enclosure took over. As the cup ‘rests within the boundaries’ of its creation, he concluded, ‘so too the birthplace of Occident and modern age, secure in its own island-like essence, remains in the recollective thinking of the sojourn’. Even the dolphins had to be gathered into a homeland.

One never finds Jaspers’ open sea in Heidegger’s writing; one does not encounter Marcel’s endlessly moving traveller, or his ‘stranger met by chance’. When an interviewer from the magazine Der Spiegel asked Heidegger in 1966 what he thought of the idea that humans might one day travel to other planets, leaving Earth behind — because ‘where is it written that man’s place is here?’ — Heidegger was appalled. He replied: ‘According to our human experience and history, at least as far as I see it, I know that everything essential and everything great originated from the fact that man had a home and was rooted in a tradition.’

For Heidegger, all philosophising is about homecoming, and the greatest journey home is the journey to death. In a conversation with the theology professor Bernhard Welte towards the end of his life, he mentioned his wish to be buried in the Messkirch church cemetery, despite the fact that he had long since left the faith. He and Welte both said that death meant above all a return to the soil of home.

Heidegger had his wish. He now lies in the Catholic graveyard on the outskirts of Messkirch. His grave is secular, bearing a small star in place of a cross, and he shares it with Elfride, who died in 1992. Two other Heidegger family graves lie to left and right of them, with crosses. The effect of the three monuments together, with Martin’s and Elfride’s larger than the others, is oddly reminiscent of a Calvary.

On the day I visited, daffodils had been freshly planted on all three graves, with handfuls of small pebbles on Martin’s and Elfride’s headstone. Sticking up perkily from the soil between their stone and that of Martin’s parents was a little stone cherub — a dreaming boy, cross-legged, with his eyes closed.

One of the graves beside Martin Heidegger’s belongs to his younger brother, Fritz, who had protected Martin’s manuscripts during the war and, along with Elfride, helped him with secretarial work and other support throughout life.

Fritz had done what Heidegger had only philosophised about: he stayed close to home, living in Messkirch and working at the same bank all his life. He also remained within the family religion. Locals knew him as a lively and humorous man who, despite a stutter, was a regular star of Messkirch’s annual Fastnacht week or ‘Week of Fools’ — a festival just before Lent marked by speeches filled with hilarious wordplay in the local dialect.

Some of this wit comes across in Fritz’s remarks to his brother. He would joke about ‘Da-da-dasein’, poking fun at Martin’s terminology as well as at his own speech impediment. Never claiming to understand philosophy, he used to say that Martin’s work would only make sense to the people of the twenty-first century, when ‘the Americans have long set up a huge supermarket on the moon’. Still, he diligently typed his brother’s writings, a great help for a philosopher who was uncomfortable with typewriters. (Heidegger felt that typing spoiled writing: ‘It withdraws from man the essential rank of the hand.’) Along the way, Fritz would gently suggest amendments. Why not write in shorter sentences? Should not each sentence convey one single clear idea? No response from his brother is recorded.

Fritz Heidegger died on 26 June 1980, his life relatively unsung until recent years, when he caught biographers’ interest as a kind of anti-Martin — a case study in not being the twentieth century’s most brilliant and most hated philosopher.

The fine print is that 4 identify as Republican, 4 as Democrat with the remaining 5 unaffiliated. This isn’t ideal from my point of view, but I presume it was required to get things through and it turns out that Republican voters are almost as against gerrymandering (88% against) as Democrat voters (92%).