Well folks. Particularly with Substack giving us a re-run of the great blogging revolution of the early naughts but with added social media functionality, I’m finding way too much wonderful stuff. So here’s a midweek edition. I’ve built up quite a work ethic with this little publication, so I hope to send you a new edition at the usual time at 10.15 am on Saturday morning. But if I don’t make it, you’ll get it Sunday — promise!

Victory in Ukraine!

Thanks to Meika for alerting me to this post via a comment on last week’s newsletter.

You do not start a war unless you hope to gain something from it. … No one knows Russia's objectives in Ukraine. But we can be quite certain that the losses incurred by the Russian military are higher than anticipated. …

Maybe Russia will eke out something akin to a win for them and a loss for Ukraine, for example by signing a peace treaty where Ukraine gives up significant portions of its pre-war territory. Such a victory will be great news for Vladimir Putin. But it will not matter that much to Russia. Or the world. No matter what the peace treaty says the war will still have cost Russia much more than it gained. … Not only will this lessen the risk of future Russian aggression, it will also send a message to other potential aggressors that violence is not the right way. This is a win for humanity.

What the West did wrong in Poland...

Contrast this with Britain's and France's attitude towards Poland in 1939. The Western powers did declare war on Germany. But apart from a token French offensive into German Saarland, Poland received no help whatsoever. … The Poles were at a significant disadvantage compared to Germany. But they were not destined to be steamrolled by the Wehrmacht. In 1939 Poland at least had a plan. They realized they would probably not be able to resist a German attack for very long, instead they intended to retreat towards the southeast, where the topography favored defense. Here, Poland had constructed multiple fortifications and placed stores of military supplies. Even more importantly, this was Poland's border with Romania, giving easy access to supplies from Romania's Black Sea ports.

Poland followed this plan well during the early parts of the German invasion. The Germans advanced much quicker than anticipated but the Poles retreated towards the Romanian border in good order. Then the Soviets attacked from the east and more or less cut off the Polish connection with Romania and the wider world. The Polish defense plan collapsed entirely. …

The Polish government and the entire Polish gold reserve also made the escape to Romania and on to France. There they reconstituted their armed forces and continued fighting under their own government financed with their own resources. The state of Poland was an asset to the allies long after the country of Poland had ceased to exist. …

The Ukraine model can be summed up as using everything to counter an aggressor except outright warfare: economic sanctions and diplomatic boycotts against the aggressor and financial and military assistance to the victims of the aggressor. …

During the 1930s Czechoslovakia spent significant resources building a system of fortifications that many considered superior to the more famous French Maginot line. There were hundreds of casemates like the one in this image. In the end all of them were given over to the enemy without a fight. Image from Wikimedia Commons. …

In 1938 Germany had no trade agreement with the Soviet Union. Such an agreement would have been of limited value anyway since Poland, hostile to both Germans and Russians, lay in the way and would not have let much trade pass. An economic blockade, especially of oil, would therefore have been very effective. It would probably not have saved Czechoslovakia but it would have severely limited Germany's ability to wage any longer war. …

Costly wars were something that Germany in the 1930s could not afford. The country was more or less broke, having invested all spare assets in their armed forces. Even had they overcome Czechoslovakia and Poland these victories would have meant nothing if they had lost more than they profited from them. And after the victories they would have found themselves in economic boycott and diplomatic isolation. Their room for maneuver would have been severely restricted and most probably the German population would have started asking questions as to whether the expensive wars had really been worth it.

Lessons learned

Western support to Czechoslovakia and Poland would most probably not have saved these countries from German aggression in the 1930s. Just as Western support may not be enough to save Ukraine from its rapacious neighbor today. …

For Ukraine it is of course a catastrophe to be invaded by Russia and an even worse catastrophe to capitulate after a long and ruinous defense. … [B]ut it is also a disaster for Russia. Even if the Russians eke out a win in the end they will be weaker at the war's end than at its start. …

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is eerily similar to the German invasion of Poland. The invasion of Ukraine also had the potential to develop either like the German annexation of Czechoslovakia, where the west sold out a friendly country, or the invasion of Poland, which developed into a world war to the detriment of everyone. That the world has avoided both of these scenarios is a great victory and should be treated as such.

You know how satisfying it is to bounce a golf-ball?

Female neediness is real, but it's not a tragedy

A fine post by Ruxandra Teslo on differing male and female hopes and expectations of relationships. Nice to see the issue discussed without the usual finger-pointing. It’s probably about three or four times the length of the extracts below and if you’re interested in the subject will reward your reading the whole thing.

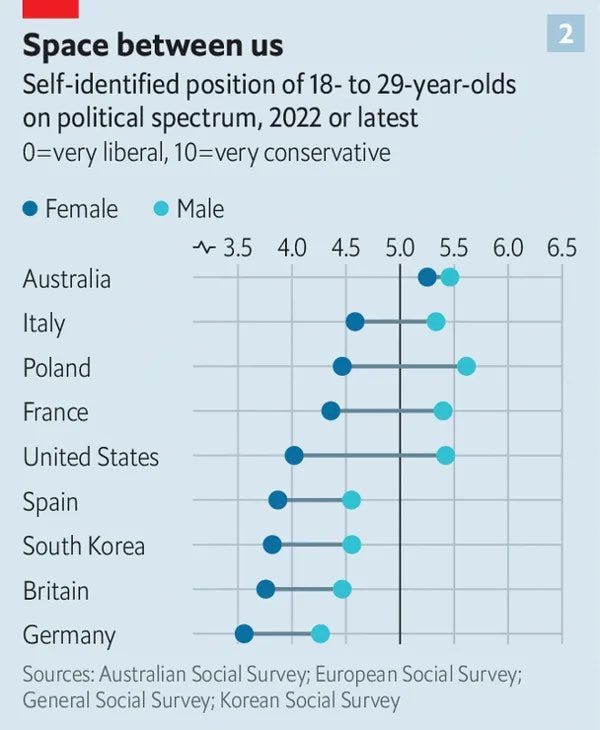

When one looks at what men and women want in love, a clear difference emerges. Surveys show that women generally aren't as interested in casual sex as men. It's not that men don't want something serious—they can and do fall in love. But they're also more likely to be okay with casual hookups along the way. Women, however, seem to have a clearer focus on finding a committed partnership1. And it’s not just that they are less interested in casual flings; they also tend to regret them more afterwards. This doesn't mean men are against being in a committed relationship or that women never enjoy casual sex. It's just that on average men have a more flexible approach, being open to both serious relationships and casual sex - and obviously in the illegible and complicated world of romance the difference in priorities will inevitably create some friction.

I don’t find any of this particularly shameful for anyone involved, and especially not for women. Emblematic of the way we talk about these issues is prominent feminist Kate Manne’s own approach. In a recent article, she describes her experience of feeling empty after engaging in casual sexual sex during her youth. …Surprisingly, given that her piece is quite long, she manages to blame her lack of satisfaction with the meaningless hook-ups of her youth on everything under the sun: misogyny, fatphobia, male privilege etc, while conspicuously avoiding any mention of the gap in preferences for casual sex between men and women. I believe this reluctance to address the topic heads-on has several negative consequences. Firstly, it creates unnecessary confusion among young women in particular, who often don’t really know why they feel what they feel and how to protect themselves from potential heartbreak. The best analogy to this is Victorian prudishness around sex itself, which left many women bewildered by their first sexual encounter, and even ashamed of enjoying sex altogether. Instead of some much needed clarity based on empirical data, “Patriarchy” and “Misogyny” get invoked like miasmas were in medieval times: these vague things that float in the air and make women unhappy, mostly at the hands of men. This way of addressing the topic also serves to increase animosity between the sexes & anxiety among young women regarding encounters with men, on the background of an already quite gender polarised youth. I believe demystifying the whole thing, making it clear that it’s down to differences that are neither inherently bad nor good, would strip away from the tragedy of it all. No one is at fault for this: men are not evil, women are not difficult. It’s just a fact that happens to be true, and knowing it is another tool in the personal arsenal with which one can now confront reality.

She then hops into self-styled ‘reactionary feminist’ Mary Harington’s take on this.

Mary Harrington, who wrote an entire book titled “Feminism Against Progress”- the gist of which is that Post-Enlightenment developments —on societal, moral and technological fronts— have been much worse for women than commonly accepted. One of her biggest obsessions (after boners) is the contraceptive pill and how much harm it has caused women. When I watch a video by Mary Harrington in which she mentions the pill (and she does do it a lot), it usually goes like this: she would start with the concern over the medical side-effects of the pill - an important and reasonable concern! But it does not take long until it becomes quite obvious she is more fundamentally against the idea of contraception itself. Why, one might ask? To quote Mary herself:

Uncoupling sex from reproduction opened the door to the privatisation of bodies.

"I am here, Jesse, where it seems there is only the dry sand and the wet blood. I do not fear so much for myself, my friend Jesse, I fear for my woman who is home, and my young son Karl, who has never really known his father. My heart tells me, if I be honest with you, that this is the last letter I shall ever write. If it is so, I ask you something. It is a something so very important to me. It is you go to Germany when this war done, someday find my Karl, and tell him about his father. Tell him, Jesse, what times were like when we not separated by war. I am saying—tell him how things can be between men on this earth. If you do this something for me, this thing that I need the most to know will be done, I do something for you, now. I tell you something I know you want to hear. And it is true. That hour in Berlin when I first spoke to you, when you had your knee upon the ground, I knew that you were in prayer. Then I not know how I know. Now I do. I know it is never by chance that we come together. I come to you that hour in 1936 for purpose more than der Berliner Olympiade. And you, I believe, will read this letter, while it should not be possible to reach you ever, for purpose more even than our friendship. I believe this shall come about because I think now that God will make it come about. This is what I have to tell you, Jesse. I think I might believe in God. And I pray to him that, even while it should not be possible for this to reach you ever, these words I write will still be read by you. Your brother, Luz"

I think this sentence pretty much summarises the core of her ideology and much of reactionary feminism itself: she believes that the progress we have witnessed in the last centuries, the apotheosis of which is “the Pill”, has somehow commoditised women. Before this, they were valued as people; now they are merely numbers in the long list of casual liaisons of soulless fuckboys. The problem with her analysis is that it’s mostly ahistorical and ignorant of human nature. …

What is there to be done?

Nothing, there is nothing substantive to be done… At least not by resorting to some top-down control mechanism.

We have reached the end of it in terms of attempts at social engineering and now we are staring at human nature itself, naked before our eyes, frightening in its immense power. Everything has a trade-off: The millions of little heartbreaks women everywhere are experiencing are just a small price we pay for not being stuck in some dead-end marriage with the first man we happened to fall in love with when we were wide-eyed 18 year olds. It’s the price we pay for not being forced into sex against our will in marriages. It’s the price we pay for not being ostracised if we have sex before marrying. It’s the price we pay for the chance of achieving that which we really want: being loved. But if that’s the case, there’s no outside institution, with legible and harsh rules, that’s gonna conjure such men out of thin air. It might be the fundamental tragedy of the human (female?) condition, but not one that can be fixed by an HR department, by the Church, by strict marriage rules, by banning the Pill or indeed, by any number of anti-freedom ideas some might try to convince you are the ultimate fix.

Random clues of cheating

Cheats usually leave traces. Then some clever cloggs in need of an academic publication uncovers them. Imagine how much Moriarty might have got away with if Sherlock Holmes hadn’t been a closet econometrician.

In 2012, New York University’s Bernd Beber and Alexandra Scacco published a seminal paper that analysed the numbers in electoral results for various countries. Their starting point was that humans are surprisingly bad at making up numbers. When asked to create random numbers, participants have been shown to favour some numerals over others. Numbers ending in zero do not feel random to us, so less than one-tenth of made-up numbers end in zero. Falsified numbers are more likely to end in 1 and 2 than in 8 and 9.

Using this insight, the researchers look at the last digit of vote counts in various elections – both in Scandinavia and in Africa. They find that vote counts in the 2022 Swedish election have last numbers that are evenly distributed from zero to nine. By contrast, in elections held in Nigeria in 2003 and Senegal in 2007, they find anomalous patterns of last digits (Beber and Scacco, 2012).

Beber, B. and Scacco, A. (2012). What the Numbers Say: A Digit-Based Test for Election Fraud. Political Analysis, 20(2), pp.211–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps003.

HT: The Australian Statistician (Private correspondence)

Why the World Bank’s Scaling Solar didn’t scale

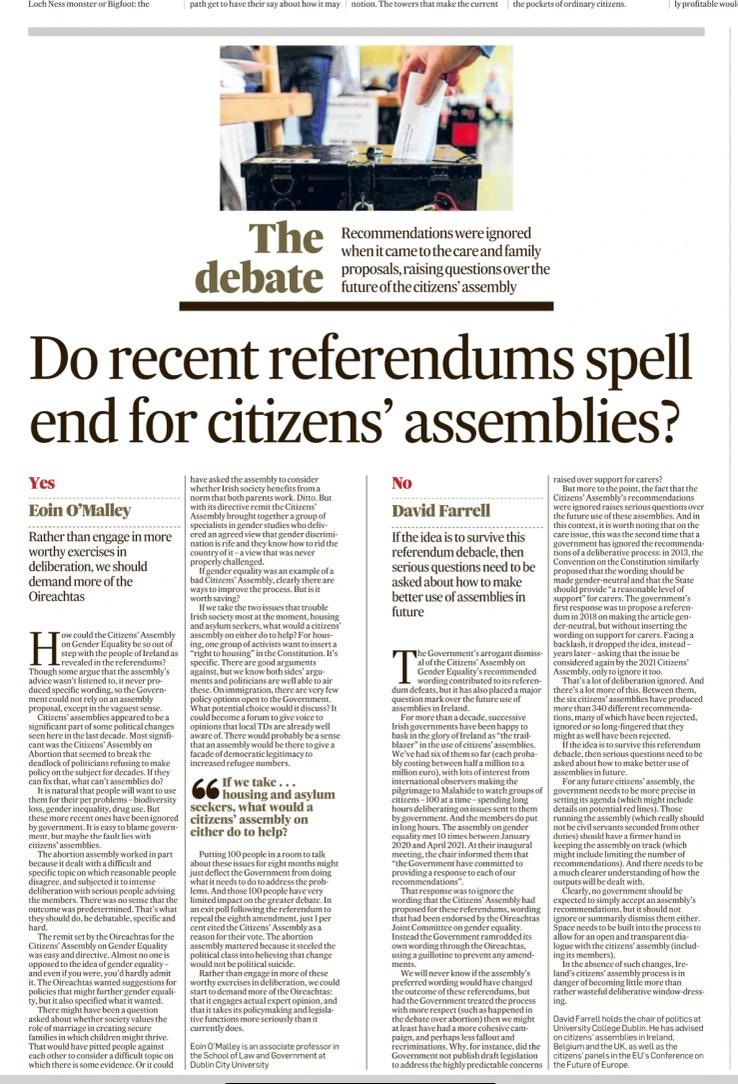

The recent Irish Referendum

There was much consternation among the sortition crowd as they processed the dismal failure of the latest Irish Referendum. The corresponding citizen assembly was held several years ago. It was on gender equality and was triggered as such referendums so often are by the perceived need to dispense with (what I’m imagining is) some junk DNA in the Constitution. That is after all where our ‘recognition’ referendum came from.

The Sortition Foundation gives us the background:

Last weekend Irish voters served politicians the largest-ever referendum defeat in Ireland’s history, resoundingly rejecting proposals to update strands of the Irish constitution relating to family roles and the duties of women. Voters were asked to vote on two changes and strongly rejected both: 67% rejected the family amendment, and 74% rejected the care amendment.

A lacklustre campaign, confused messaging and rushed campaigning have all been blamed for the defeat. But a key factor was that the government watered down recommendations made by Ireland’s citizens’ assembly.

The result demonstrates the importance of following through on citizens’ assemblies recommendations if you want to secure buy-in from the wider electorate. Or, as Sinn Fein leader Mary Lou McDonald, put it: “There is little point in having a Citizens Assembly if the government are then going to ignore the outcome.”

Quite. Below is a ‘for’ and ‘against’ piece in the Irish Papers — if you open it in its own tab you should be able to blow it up sufficiently to read it. In any event, neither case really satisfied me. On one side we had someone who basically doesn’t think there’s much of a role for ordinary citizens in deliberating about policy. On the other someone who is upset that parliaments won’t take them more seriously. But since Ireland is the pin-up boy for citizen assemblies (at least in the English-speaking world) it’s time to face up to the obvious fact that occasional servings of recommendations from citizen assemblies doesn’t do much more than give the existing system the occasional ‘issues management’ moment.

I’d like to see some greater aspiration to working citizen assemblies into our constitution. As I’ve argued, it needs to be a standing citizen assembly and that would have two impacts. In the case of each of the recommendations from a citizen assembly, the standing citizen assembly would be there to provide commentary on how well the existing system was performing in responding. And more significantly, it would provide citizens with an ongoing comparison between how elected representatives handled issues and how sampled representatives handled them. I have little doubt citizens would come to appreciate this other way of doing politics and would want the chamber chosen by lottery to have more power.

An important genre: The non-review

Guy Rundle on the grey clouds of Tasmanian torpor

My guess is that the Opposition leader had some calls in which cross-benchers said they wouldn’t support her. So she capitulated. [I heard today that ALP head office was behind the capitulation — on the grounds that it is worse to form a government with the Greens than not to form a government.] But what would I know?

I like Guy Rundle’s sketch of the possible, which, as he points out, can be resurrected after a period during which the Libs try to run a minority government. But it requires a degree of maturity from the main left of centre parties — the ALP and the Greens that falls woefully short of the rather low benchmark the Liberal and Country National Parties seem capable of.

The third road, the one not taken? That Rebecca White had gazumped her own party on Saturday night and said we won’t know the full result for weeks, but there will clearly be a larger number of clear progressives than Liberals, and we will try to form a Labor-Green-independent coalition at that time, with all groups taking ministries.

God, imagine the sudden release of energy and possibility from that! Imagine the sense of determination had White been seized with that audacity, and stared down her colleagues and her federal overlords. Imagine the sense of sudden clear purpose, the drafting of an initial minimum program, with a further process of collective policy development to come.

Suddenly Tasmania would be the place it sometimes is, that of possibility and fresh thinking. The progressive coalition would create something of a norm of cooperation and dialogue, and start to push against the other side of Tasmania, the slightly shonky Company aspect. White would be hailed as an audacious hero. Should the numbers not have got there in the final count, she could yield gracefully to the Libs. But had they hit 18, or even 17, she could have gone to the governor with a stable alternative.

Instead, the gray clouds of torpor roll back over. Jeremy Rockcliff doesn’t sound excited or at the beginning of anything, and why should he? Things are much worse in the Assembly, and dire in the partyroom, where the Christian right are stalking him, ready for the entrance of Premier Abetz — a coup which would itself prompt possible resignations of the whip. Politically, it will all be ceaselessly enervating, without providing any real sense of possibility.

One had hoped the first outing of the re-enlarged Hare-Clark might provide for some audacious announcements in the tally room. Instead it will emphasise to many the separation of political and social life. A well-earned boost for the Greens, who are nevertheless a professional outfit. But no new independents, and in the swing seats, the Jacqui Lambie Experience, four lists of ticket-fillers for a party with no policies, and whatever happened to Saturday night?

AWKS

As Former Foreign Affairs and Trade Secretary Peter Varghese has said, "The anti-AUKUS argument is now reasonably complex and sophisticated while the pro-AUKUS position rarely rises above platitudes."

What an extraordinary state of affairs. That wouldn’t have surprised me with the Morrison Government. But the current government’s strategy appears to have been born in 24 hours in an understandable manoeuvre to avoid being distracted in the last election. It wouldn’t have been hard to rearrange things after the election. To double down instead is about the worst thing I’ve seen a Labor Government do.

Sam Roggeveen takes up the story:

In the two-and-a-half years since the deal was announced, we have not once heard — either from the Morrison government or its successor — what the order for eight nuclear-powered submarines is actually designed to achieve. With neither a prime minister nor a senior minister providing any kind of strategic rationale for the deal, the case for AUKUS has not advanced beyond clichés and truisms about “deterrence.” Apart from pacifists, everyone is in favour of deterrence; the debate is solely about how we deter, and on this point the pro-AUKUS side has barely engaged. …

A heated debate took place at the [ALP’s] national conference in September last year, but ultimately a resolution backing the initiative passed with a comfortable majority. Former Labor leader Kim Beazley was moved to describe AUKUS as a “core Labor value,” evoking a sense of grassroots support and deep historical resonance. Beazley called the conference vote “the most significant move in the party since the 1963 Labor Federal Conference,” which dealt with the establishment of the North West Cape naval communications station.

But there is reason to doubt the sincerity of Labor’s conversion. Before AUKUS, no senior Labor figure had ever campaigned for nuclear-powered submarines. Indeed, support for such subs was a fringe position even in the Australian strategic debate. Then, in September 2021, the Morrison government gave the Labor opposition less than a day’s notice before announcing AUKUS. Labor, fearing a khaki election, instantly threw its support behind the initiative. …

But even assuming support for AUKUS inside the Labor caucus is a mile wide and an inch deep, does that matter for the future of the project? Perhaps less than we might think. Major political questions are never decided purely on principle or on the careful weighing of policy alternatives divorced from party-political considerations. Politicians can change their minds, but they change them faster if arguments align with incentives. At present, that’s simply not the case. …

AUKUS spending is not expected to peak for some years. Of a total project cost of between A$268 billion and A$368 billion, the government expects to spend A$58 billion over the next decade, but with less than a quarter of that sum due in the first five years. In budgetary terms, therefore, the decision is easy. Why offer the opposition a stick with which to beat the government at the next election when avoiding that fate costs the government so little?

Labor doesn’t even have an incentive to encourage debate about the deal by having the prime minister or defence minister give a major address. Policy wonks want such a debate, but who gains? What powerful political force would be quieted by a prime ministerial statement? Critics of AUKUS are unlikely to be satisfied; supporters just want to see the project go ahead.

This reflects two things about the structure of Australian politics: first, the number of people who care about defence policy is tiny, and so government doesn’t feel an urgent need to be accountable; second, the number of key decision-makers in defence and foreign policy can be counted on one hand. Unlike in the United States, no alternative base of power exists in the legislature to encourage accountability. …

While media and political attention is focused on whether AUKUS can be delivered, in the background lurks a strategic question: even if we can get AUKUS done, is it even a good idea? That’s the issue The Echidna Strategy focused on. Australia’s biggest strategic asset is distance — Beijing is closer to Berlin than it is to Sydney — yet the AUKUS submarine project is effectively an attempt to compress that distance when we should be exploiting it. If China ever wants to project military force against Australia, let it traverse the vast oceans that separate us. There is no pressing reason for Australia to project military power to China’s near seas and onto its landmass.

Such arguments have no purchase on either major party right now, but the real job of books like mine is to open the “Overton window” — to make the unthinkable thinkable. When AUKUS begins to sink under the weight of its misdirected ambition, political leaders will look for new ideas. An alternative defence strategy exists that is prudent and affordable, not weighted with ideological baggage from either extreme, and based on realistic assumptions about the future of Chinese and American power in our region.

Most of us have learned to grow sideways at one time or another

In praise of moderation: Highly recommended

HT: Christos.

Two delicious exhibits from Proust and the Squid

I’m listening to Proust and the Squid on the acquisition of written language. It is achieving a fairly high level of terrificness. Here are two things it quotes which I loved.

From Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Huck is traveling on a raft on the Mississippi River with his friend Jim, a runaway slave, who is being hunted down. To keep a group of men from discovering Jim’s identity, Huck, in a stroke of genius, pretends that Jim has smallpox. After the men scurry away, Huck is beset with doubts:

They went off and I got aboard the raft, feeling bad and low, because I knowed very well I had done wrong, and I see it warn’t no use for me to try to learn to do right; a body that don’t get started right when he’s little ain’t got no show—when the pinch comes there ain’t nothing to back him up and keep him to his word, and so he gets beat. Then I thought a minute, and says to myself, hold on; s’pose you’d ’a’ done right and give Jim up, would you felt better than what you do now? No, says I, I’d feel bad—I’d feel just the same way I do now. Well, then, says I, what’s the use you learning to do right when it’s troublesome to do right and ain’t no trouble to do wrong, and the wages is just the same? I was stuck.

An anonymous poem ‘celebrating’ the exasperating irregularities in our language:

I take it you already know

Of touch and bough and cough and dough?

Others may stumble, but not you

On hiccough, thorough, slough, and through?

Well done! And now you wish, perhaps,

To learn of less familiar traps?Beware of heard, a dreadful word

That looks like beard and sounds like bird.

And dead; it’s said like bed, not bead;

For goodness sake, don’t call it deed!

Watch out for meat and great and threat,

(They rhyme with suite and straight and debt).

A moth is not a moth in mother.

Nor both in bother, broth in brother.And here is not a match for there,

And dear and fear for bear and pear,

And then there’s dose and rose and lose—

Just look them up—and goose and choose,

And cork and work and card and ward,

And font and front and word and sword.

And do and go, then thwart and cart.

Come, come, I’ve hardly made a start.A dreadful language? Why, man alive,

I’d learned to talk it when I was five.

And yet to read it, the more I tried,

I hadn’t learned it at fifty-five.

Why Popper and Kuhn’s star rose and Michael Polanyi’s waned

Most of us have heard of the idea that, for a proposition to be scientific, it must be falsifiable — an idea associated with Karl Popper. And Thomas Kuhn's idea of 'paradigms' slid into the language following the publication of his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In this podcast, I argue that Polanyi should be as well known as Kuhn (Kuhn seems to have got his core idea of the incommensurability of paradigms from Polanyi). And Polanyi scholar Martin Turkis and I ask why it is that Polanyi’s star waned. I think the answer is also related to another somewhat surprising phenomenon. A remarkably large number of those studying Polanyi today have a particular interest in religion. Though religion was very important to Polanyi, he only mentioned it as a parting thought at the end of his major publications.

My explanation for why Polanyi’s star waned in academia is the same as my explanation for why where he does live on, this is disproportionately in theology schools and among scholars with a religious bent.

The audio file is here.

Angus Deaton is unimpressed

Thanks to subscriber Robert Banks for this piece. It’s remarkable how many great economists end their days lamenting the state of their profession. They include Joan Robinson, Robert Solow, Ronald Coase and now Nobel winner and documented of ‘deaths of despair’ Angus Deaton.

Like many others, I have recently found myself changing my mind, a discomfiting process for someone who has been a practicing economist for more than half a century. I will come to some of the substantive topics, but I start with some general failings. …

Power: Our emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game. Without an analysis of power, it is hard to understand inequality or much else in modern capitalism.

Philosophy and ethics: In contrast to economists from Adam Smith and Karl Marx through John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, and even Milton Friedman, we have largely stopped thinking about ethics and about what constitutes human well-being. We are technocrats who focus on efficiency. We get little training about the ends of economics, on the meaning of well-being—welfare economics has long since vanished from the curriculum—or on what philosophers say about equality. When pressed, we usually fall back on an income-based utilitarianism. We often equate well-being with money or consumption, missing much of what matters to people. In current economic thinking, individuals matter much more than relationships between people in families or in communities.

Efficiency is important, but we valorize it over other ends. Many subscribe to Lionel Robbins’ definition of economics as the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends or to the stronger version that says that economists should focus on efficiency and leave equity to others, to politicians or administrators. But the others regularly fail to materialize, so that when efficiency comes with upward redistribution—frequently though not inevitably—our recommendations become little more than a license for plunder. …

Empirical methods: The credibility revolution in econometrics was an understandable reaction to the identification of causal mechanisms by assertion, often controversial and sometimes incredible. But the currently approved methods, randomized controlled trials, differences in differences, or regression discontinuity designs, have the effect of focusing attention on local effects, and away from potentially important but slow-acting mechanisms that operate with long and variable lags. Historians, who understand about contingency and about multiple and multidirectional causality, often do a better job than economists of identifying important mechanisms that are plausible, interesting, and worth thinking about, even if they do not meet the inferential standards of contemporary applied economics.

Humility: We are often too sure that we are right. Economics has powerful tools that can provide clear-cut answers, but that require assumptions that are not valid under all circumstances. It would be good to recognize that there are almost always competing accounts and learn how to choose between them.

Second thoughts

Like most of my age cohort, I long regarded unions as a nuisance that interfered with economic (and often personal) efficiency and welcomed their slow demise. But today large corporations have too much power over working conditions, wages, and decisions in Washington, where unions currently have little say compared with corporate lobbyists. … Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson have recently argued that the direction of technical change has always depended on who has the power to decide; unions need to be at the table for decisions about artificial intelligence. Economists’ enthusiasm for technical change as the instrument of universal enrichment is no longer tenable (if it ever was).

I am much more skeptical of the benefits of free trade to American workers and am even skeptical of the claim, which I and others have made in the past, that globalization was responsible for the vast reduction in global poverty over the past 30 years. I also no longer defend the idea that the harm done to working Americans by globalization was a reasonable price to pay for global poverty reduction because workers in America are so much better off than the global poor. I believe that the reduction in poverty in India had little to do with world trade. And poverty reduction in China could have happened with less damage to workers in rich countries if Chinese policies caused it to save less of its national income, allowing more of its manufacturing growth to be absorbed at home. I had also seriously underthought my ethical judgments about trade-offs between domestic and foreign workers. We certainly have a duty to aid those in distress, but we have additional obligations to our fellow citizens that we do not have to others.

I used to subscribe to the near consensus among economists that immigration to the US was a good thing, with great benefits to the migrants and little or no cost to domestic low-skilled workers. I no longer think so. Economists’ beliefs are not unanimous on this but are shaped by econometric designs that may be credible but often rest on short-term outcomes. Longer-term analysis over the past century and a half tells a different story. Inequality was high when America was open, was much lower when the borders were closed, and rose again post Hart-Celler (the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965) as the fraction of foreign-born people rose back to its levels in the Gilded Age. It has also been plausibly argued that the Great Migration of millions of African Americans from the rural South to the factories in the North would not have happened if factory owners had been able to hire the European migrants they preferred.

Human capital or credentialism?

Another telling passage from Dean Ashenden’s Unbeaching the Whale:

The economic argument

In 2007, as we have seen, Kevin Rudd promised an education revolution in the name of our economic future. It was “now clear, and widely accepted across the OECD nations” (he declared) that economic reform must centre on “investment in human capital.” In this we were falling behind. Australia’s “national investment” had not been keeping up.

Talk of what is “now widely accepted” has a misleadingly hot-news air to it. By the time Rudd spoke nearly half a century had passed since the human capital idea was hot news, and then — in the early 1960s — it certainly was hot. The OECD had seized on an argument developed by a small group of University of Chicago economists in the late 1950s that promised to revolutionise the way education was thought about: education wasn’t an expense, it was an investment.

The news reached Australia in 1964 courtesy of the Martin enquiry into the tertiary education system. Martin was much taken by a table and a graph, both supplied by the Chicago economists via the OECD. The graph showed two diagonal lines running from bottom left to top right, along which were scattered the names of twenty or so countries. Up in the top right-hand corner were the richest and most educated (the United States and Canada); down at bottom left were the poorest and worst educated (Portugal and Turkey). The table showed much the same thing happening to individuals. The more educated the Americans (ie. American men), the higher their incomes. Those with no education at all earned only half as much as those with eight years of schooling; four-year college graduates more than doubled the school-only amount. This was “human capital” at work. Individuals and economies alike were more productive when they had more human capital to call on. Employees, employers and society would all be wise to invest because education offered an excellent rate of return.

The engine of these startling numbers, Martin argued (again following the OECD and the Chicago economists), was an increasingly complex and technological social and economic order and its ever-expanding numbers of knowledge-based occupations. That was where the education system came in. It was the key producer and distributor of knowledge, and knowledge was driving greater productivity. The economic harvest followed the educational plough. As time went by, human capital enthusiasts found yet more “benefits” education bestowed on the economy and the wider social order.

The idea soon ran into scepticism and some outright opposition. Was it confusing correlation with causation? Was growth in education an effect rather than (or as well as) a cause of economic growth? Why so much talk about the “benefits” but none about the damage done (by schools particularly)? Did education make individuals more productive or was it just that credentials bumped them up the queue so that they got the more productive jobs (and the social behaviours and outlook that come with those jobs)? By the mid-1970s a leading international authority on the economics of education could summarise the many strikes against human capital theory and conclude that its “persistent resort to ad hoc auxiliary assumptions to account for every perverse result” and tendency to “mindlessly grind out the same calculation with a new set of data” were signs of a “degenerate scientific research program.”

To worry away at the problems[v] the OECD brought together economists from every corner of a far-flung discipline, but it dearly wanted to annexe education to the economy (it was the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development after all) and it needed the human capital argument to do it. It sponsored one “rethinking” after another, gradually shifting the emphasis from explanation to the safer ground of prescription, but it never abandoned the basic idea that education drives economic growth.

Both the critics and the rethinkers could have saved their breath, at least so far as Australia was concerned. In the thirty years following the Martin report the number of students in Australian schools more than doubled, in technical education tripled, and in higher education multiplied by a factor of twelve. In the decade from 1980 the proportion of the working-age population holding post-school qualifications rose from 38 per cent to 48 per cent; over the twenty-five years from 1989 the proportion with a bachelor’s degree or higher tripled. Was this to fuel the ravenous economic machine? During the first of these periods (1980–90) the proportion employed in the skilled occupations rose not at all; in the second, the proportion of professionals in the workforce rose sedately from 15 per cent to 22 per cent.[vi] And yet, after all those decades of educational expansion running well ahead of economic demand, Labor in opposition and then in government could still call for more, drawing on a version of human capital theory that could have come from the Martin report of 1964 to do it.

In schooling, human capital theory wasn’t just implausible; it was largely irrelevant. The relationship between school, work and further study in the lives of older teenagers is complicated, but by 2007, when Rudd called for revolution, schooling, in very general terms, had less to do with the economy than at any time since the 1950s. Then, the technical and agricultural high schools were complemented by “practical” subjects (typing for girls, woodwork for boys) in the comprehensives, and most of the students in “academic” streams left school not for tertiary education but for white-collar work. Fifty years on and the situation had changed dramatically: roughly three in every four students were being prepared not for work but for further study. The remaining quarter weren’t being prepared for work either; most were being ejected with no real preparation for anything, and such work as these “early leavers” or “dropouts” could get was not in the “knowledge economy.”

Many teachers wanted to do more and better for those who were so badly treated by schooling, the labour market and the social security system, but that was not the same as being fired up by the call to deliver economic growth. Nor was human capital theory of much use to schooling’s policymakers. Apart from “more,” what did it suggest about the shape and conduct of the sector? Education ministers and authorities didn’t need to be told that more young people should stay longer at school; as they well knew, getting it was a lot harder than wanting it.

***

Much more help was to be had from a quite different way of thinking about the education–economy relationship, but it found its way to few if any of those responsible for schooling policy. In this alternative argument an increasingly complex and technology-centred social and economic order does indeed need more “knowledge workers” (even if not nearly as many of them as the education system was producing), but education performs other and quite different functions as well, less as a driver of economic growth than as a distributor of its rewards.

On this view, the education system had moved over the course of the twentieth century from the margins to the centre of ever-intensifying competition for “positional goods,” goods establishing the possessor’s position in the social order. That reality, and the ever-finer social differentiation it generates, were not lost on Britain’s poet laureate, Simon Armitage, in his fierce poem “Thank You for Waiting.” Beginning with an invitation to “First Class passengers only” to board the aircraft, it welcomes Exclusive, Superior, Privilege and Excelsior members, then Triple, Double and Single Platinum members, then “Mediocre passengers” and their ilk, until last and emphatically least come the scroungers, malingerers, spongers, freeloaders and those holding tickets for zones Rust, Mulch, Cardboard, Puddle and Sand.

That educational credentials are prized instruments in the scramble is obvious, as is the fact that ever-increasing numbers of families and students have tried to get hold of them via extended schooling. Less obvious but more important than individual competition is competition between occupational groups. Credentials, most acquired through formal education and conferred by educational institutions and authorities, are central to the efforts of occupational groups to position themselves as advantageously as possible. Credentials provide what the engineers, in their pivotal 1961 case before the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission, called “definition by qualification.” This definition the commission agreed to grant, with immediately gratifying results.

Definition by qualification works in a very straightforward way: define an area of work and close it off to all except those with a qualification acceptable to those already on the inside. In this the engineers were following many footsteps. Occupational closure by qualification had been pioneered in nineteenth-century Australia at two levels of the labour market, at the top (in the “professions”) by medical practitioners, and about half-way down by the trades. Both added increasing quantities of formal education to learning on the job. With formal education/training came the credential that could be used to claim and then police exclusive rights to an area of work or practice. Occupations able to point to health and safety in making their claim on public authorities did best. By the time the engineers had made their case, so many other occupational groups had defined themselves by qualification that defending a patch and maintaining relativities had become as pervasive as getting control of one in the first place.

Once that mechanism is understood much that is otherwise puzzling about education becomes clear: why the system’s expansion has so often run far ahead of production and productivity (because the rush to get credentialled created a self-fuelling spiral); why so much learning and skill acquisition has been displaced from workplaces to front-end formal education (because credentials could not be got from the workplace no matter how much usable learning it might provide); why schools’ curriculum and assessment have been constructed to place every member of each cohort in a giant rank order made public and explicit by the ATAR (because credentials are the instruments of competition between individuals and groups, and schools are increasingly the arena of competition between individuals); why the school system first developed and then abolished “technical education” in favour of a “general” curriculum for all (because credentials not capabilities were at a premium and because an “equal opportunity” to win was increasingly demanded and provided); and why schooling has increasingly permitted and provided “choice” for families jockeying for position (because many well-placed parents wanted an unequal opportunity for their children).

In other words, the relationship between education and the economy is as much social, political and ideological as it is economic, a point lost on economics and its practitioners. Formal education is indeed much better than most workplaces at developing some forms of intellectual capacity needed in economic activity, and “the economy” suffers if these capacities are not available. But learning of other kinds is best done in the workplace. Human capital theory is prevented by its discipline’s arrogance from seeing its own quite narrow borders and from realising that other disciplines might know things about the economy (not to mention the economy–education relationship) that it doesn’t.[xiv] It is a loyal functionalist social science. All it can see is economic functions performed together with certain malfunctions such as “over-education” (resulting from what it calls “credentialism”). With rare exceptions its discussions of “credentialism” make no reference to, much less comprehend, key texts in the history and theory of credentialism.

***

Students of “credentialism” are baffled by their critique’s failure to get any real attention. The editors of a scholarly journal’s special edition on “New Directions in Educational Credentialism” express dismay and frustration that “despite the strong and promising theoretical and empirical foundations,” despite some important work building on those foundations, and despite the explanatory power of the hypothesis, the sociological and historical literature of credentialism remains under-developed[xvi] — and, it might be added, almost completely ignored by policymakers.

One part of the answer to this puzzle lies in the status of the disciplines referred to. History ranks lower than the “hard” discipline of economics in the academic pecking order; sociology is lower still. The “soft” humanities and social sciences only rarely have the ear of the powerful. Perhaps most salient of all: the credentialism thesis blows the whistle on a powerful academic discipline, on powerful occupational groups, and on an education industry for which Rudd’s call for “more” was more than welcome. For the system as a whole, Rudd’s human capital theory sent policy off in the wrong direction entirely. Attention that should have been directed to the shape and content of the system, its relationship with workplace learning and the need for much more learning in and through work was directed instead to the system’s size.

In schooling, what was imagined to be a big idea was in reality small one. Human capital theory had very little to offer the schooling revolution by way of justification, explanation, guidance or motivation. Perhaps its main consequence was to extend the long failure by Australian governments to consider the merits and uses of a much more coherent if still-incomplete account of the relationship between schooling and the economy.

Heaviosity half hour

Peter Singer on Karl Popper

Bryan Magee’s clear little introduction to the thought of Karl Popper opens with the remark that Popper’s name is not yet a household word among educated people. The remainder of the book is an attempt to remedy this allegedly undeserved neglect.

The educated reader might think that Popper has received adequate recognition. After all, Popper, an Austrian schoolteacher who left his native land in 1937 in anticipation of Nazi annexation, gained a world-wide reputation in 1945 with the publication of The Open Society and Its Enemies. Later, at the London School of Economics, he became Professor of Logic and Scientific method. He has now been a leading figure in the philosophy of science for many years; his Logic of Scientific Discovery, a translation of a work he had already published before he left Austria, must now be a part of almost every philosophy of science course in the English-speaking world.

In 1965 Popper became Sir Karl, and this year the Danish government chose him, at the age of seventy-one, for its Sonning Prize, previously awarded to figures like Bertrand Russell and Sir Winston Churchill, and worth around $45,000. Now, the publication of The Philosophy of Karl Popper (a collection of critical essays with replies by Popper) gives Popper a niche in the Library of Living Philosophers, alongside predecessors like Dewey, Moore, Russell, and Einstein. In fact, Popper has upstaged them all by being the first to run to two volumes.

The rewards of academic life do not normally include knighthoods and large sums of money. Is there any reason why Popper should deserve more than most other philosophers? Magee thinks there is. His short book makes or endorses an extraordinary series of claims for its subject. If they were all justified, Popper would have to be regarded as the outstanding philosopher—perhaps the outstanding thinker—of the twentieth century.

Among these claims are: Popper is the greatest living philosopher of science, and has influenced outstandingly successful scientists; Popper has solved the problem of induction, that “skeleton in the cupboard of philosophy” which has baffled philosophers from David Hume to the present day; Popper published the central arguments against logical positivism, even before that particular philosophy became fashionable in the English-speaking world; Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies contains “the most scrupulous and formidable criticism of the philosophical and historical doctrines of Marxism by any living writer” (the quotation is from Isaiah Berlin, but Magee adds: “I must confess I do not see how any rational man can have read Popper’s critique of Marx and still be a Marxist.”); Popper has written the most powerful defense of democracy in the English language.

Finally, Popper’s latest achievement, his theory of “objective knowledge,” offers solutions to the following range of problems: the relationship of bodies and minds, the objectivity of morality and aesthetics, problems of social and political change “which have engrossed the greatest philosophers from Plato to Marx,” and problems about intellectual and artistic change that have engrossed various other great philosophers. All this in prose that is “massively distinguished…magnanimous and humane.”

The Philosophy of Karl Popper, by the range of contributions it has assembled and the prestige of its contributors, also makes a strong claim for the uniqueness of its subject. There are philosophers interested in logic or philosophy of science, like William Kneale, W.V. Quine, Hilary Putnam, A.J. Ayer, and Thomas Kuhn; distinguished scientists discuss the bearing of Popper’s thought on fields like physics, psychology, and neurophysiology; John Wild criticizes Popper’s interpretation of Plato, and H.B. Acton has sent in an essay vaguely related to what Popper wrote about Marx; Edward Boyle, who might have been Britain’s Minister of Education had he not been too liberal for his Conservative colleagues, tries to say what Popper’s political ideas meant for him as an active politician; there are essays on Popper’s case against determinism, his views on the nature of time, and his theory of method in the social sciences; Ernst Gombrich completes the diversity by using some of Popper’s remarks to illuminate the history of art.

So…Popper is clearly an unusual figure among professional philosophers: but is he the genius Magee would have us believe?

Straight off, we can accept two of Magee’s claims—or say that they are, at worst, exaggerations of genuine achievements. This is enough to make us take Popper seriously.

First, if Popper is not the greatest living philosopher of science I am not sure who is; and that Popper has influenced important scientists is undeniable, since two of the contributors to The Philosophy of Karl Popper who acknowledge his influence are Nobel Prize winners Sir John Eccles and Sir Peter Medawar. Popper’s work in this field, of which I shall say more shortly, is his prime achievement. Although, as Popper himself admits in his comments on Medawar’s essay, his essential ideas had been anticipated by nineteenth-century logicians like C.S. Peirce and W. Whewell, we should not let this affect our estimate of what Popper has done. While the continuing tradition of American pragmatism has kept Peirce’s ideas alive at some American universities, it is largely to Popper that we owe the present widespread popularity of the approach to science that is common to the thought of Peirce, Whewell, and Popper; hence these ideas are rightly associated with Popper’s name.

It is also true that Popper published important criticisms of logical positivism as early as 1934. At that time this particular philosophy had already had several years of popularity with Carnap, Schlick, and others among the philosophers of the Vienna Circle. Popper is sometimes thought to have been a member of this now almost legendary group of influential thinkers. The Philosophy of Karl Popper should settle this issue. It includes a substantial intellectual autobiography in which Popper discusses his relations with the Circle, as well as an essay by Victor Kraft, himself a member of the Circle, on the same topic.

Although Popper read papers to smaller “epicycles” of the Circle, he was never a member of it, and he never accepted its central doctrines. In particular he opposed the attempt to distinguish sense from nonsense by means of the “verification principle”—which holds that a statement only makes sense if in principle one can verify it. He argued against this idea that it would make all metaphysics gibberish, since one had to understand a metaphysical theory before one could judge whether it could be verified. Moreover, the principle of verification was itself unverifiable!

In place of the principle of verification, Popper proposed his own principle of falsifiability—not, however, as a means of distinguishing sense from nonsense, but as a means of separating scientific theories from various kinds of pseudoscience, especially those, like Marxism and psychoanalysis, that were in vogue in Vienna at the time. In contrast to Einstein, who had boldly risked his theory by predicting unexpected outcomes for certain experiments, Marxists and Freudians claimed to explain anything and everything by their theories. By failing to make claims that might be shown false, Popper said, they evaded refutation at the cost of their scientific status.

These and other arguments Popper published in his Logik der Forschung, which appeared two years before A. J. Ayer’s brilliant manifesto Language, Truth, and Logic spread the new gospel of positivism to the English-speaking world. For many years, philosophers in Britain and America took no notice of Popper’s objections, perhaps because they had not appeared in English.

It is more difficult to assess the rest of Popper’s work. In order to give some impression of the ground covered by The Philosophy of Karl Popper, and at the same time to consider the further claims that Magee makes on Popper’s behalf, I shall select three main areas. Apart from the two achievements just recognized, Popper himself would probably give most weight to the claim that he has solved the ancient philosophical problem of induction. In discussing this issue, we shall be able to see just what Popper has and has not accomplished in the philosophy of science. Second, I shall offer some brief comments on the newest development of Popper’s thought, the theory of “Objective Knowledge,” from which Popper’s recently published book of essays takes its title. Finally, I shall consider Popper’s political ideas, and his critique of Marxism.

Before we come to the substance of Popper’s work, however, a word about his philosophical style may help us to understand why he has become such a controversial figure on the normally decorous philosophical scene.

For Popper, philosophy is an attempt to get nearer to a true view of the world, that is, a view that corresponds to the facts. This makes philosophy a serious and important activity. To approach the truth, we must scrutinize assumptions—metaphysical, moral, and political—that affect everything we do. So philosophy is not just an intellectual game. It really does matter.

In the autobiographical section of The Philosophy of Karl Popper Popper tells of his first encounter with Wittgenstein, and this incident serves to mark the contrast between Popper’s idea of philosophy and that which prevailed in England from the end of the Second World War until roughly the early Sixties. In 1946 Popper was invited to give a paper at Cambridge “stating some philosophical puzzle.” The wording of the invitation revealed the hand of Wittgenstein, who held that there are no real philosophical problems, only puzzles to be cleared up by a careful analysis of ordinary language. Characteristically, Popper met the challenge head on by saying that if he thought there were no genuine philosophical problems he would not be a philosopher. After a brief exchange, Wittgenstein apparently decided that Popper was a hopeless case, and stormed out of the room, banging the door behind him.

So, during the heyday of Wittgenstein’s influence, Popper remained outside the mainstream of British philosophy, going his own way with a stubborn sense of what was really important and what was a mere dispute over words. It could hardly have been otherwise. This was a period in which philosophy turned in on itself, and philosophers puzzled away at little bits of linguistic usage that had led their holder predecessors astray. Popper was a philosopher for the physicist, the economist, the historian, the politician. While this audience appreciated the importance of the issues Popper was addressing himself to, mainstream academic philosophers thought him insufficiently subtle.

At the same time, Popper’s personal style did not help to endear him to his English colleagues. His commitment to the importance of his subject spills over into his books and articles, which become the weapons with which the battle against error is to be fought. He assails his opponents with arguments from all sides, and sometimes with ridicule and abuse as well. As if that were not enough. Popper can also be tediously repetitious and irritatingly egotistical, (Why, for instance, does he have to tell us on at least three separate occasions in Objective Knowledge that it was he who invented the label “Hume’s problem” for the problem of induction. Who cares?)

If Popper’s style puts off many, however, it also attracts some fervent disciples most of whom are represented in The Philosophy of Karl Popper. For some years now there has been a little hand of enthusiastic Popperians, carrying forward the banner of Popper’s ideas. Now and again one will fall from grace, and another will appear. Magee is obviously a recent convert; on the other hand, Popper’s reply to the essay by Imre Lakatos in The Philosophy of Karl Popper clearly marks the excommunication of that once lofty follower, for the series of papers in which this former student and colleague of Popper’s has tried to guide the reader through Popper’s writings is now declared, by the ultimate authority himself, to be “unreliable and misleading,” Poor Lakatos.

Popper’s knack of attracting disciples is an intriguing phenomenon, although one that cannot be discussed here. The irony is that Popper, the biting critic of petty, scholastic wrangling, now has to admit that his own works have become the subjects of scholastic disputes. It must be galling for Popper to find himself divided by his supporters into Popper, Popper1, and Popper2 with consequent endless possibilities for debates over interpretations. On the other hand, Popper complains so frequently of being misunderstood—the intentions of the editor of The Philosophy of Karl Popper have been seriously thwarted by the fact that on several occasions Popper and his critics simply fall to engage because, according to Popper, the essays are directed against positions that he never held that one begins to suspect that the fault may lie with the author as much as with the expositor or critic.

Finally, so far as style is concerned, Popper’s desire to swamp his opponents with criticism results in a failure to distinguish good arguments from bad. While one may applaud Popper’s conviction that real argument is preferable to the kind of suggestive observations that Wittgenstein and his followers used to throw out, Popper himself has debased the currency of argument by his indiscriminate employment of any argument that comes to hand. Does Popper really think, for instance, that it is an argument against the impossibility of doubting one’s own existence that Kipa, a Sharpa who went further up Everest than was good for him, afterward thought he was dead? Or even that Popper himself had the same experience when struck by lightning in the Austrian Alps (Objective Knowledge, p. 36)? Any undergraduate philosopher would reply that believing one is dead is very different from believing that one doesn’t exist.

Some of Popper’s replies to his critics in The Philosophy of Karl Popper contain arguments almost as bad—for instance, in reply to the ease for determinism presented by Feigl and Meehl, Popper remarks that they were unable to predict the form his reply would take, although Feigl and Meehl had explicitly disclaimed the ability to make such predictions.

What has Popper achieved in the philosophy of science, and how does his achievement relate to the problem of induction?

Science, according to a tradition going back to Francis Bacon, proceeds from the open-minded accumulation of observations. When the scientist has collected enough data he will notice a pattern beginning to emerge, and he will hypothesize that this indicates some natural law. He then tries to confirm this law by finding further evidence to support it. If he succeeds he has verified his hypothesis. He has discovered another law of nature.

Popper’s challenge to this view starts from the simple logical point that a universal statement like “All swans are white” cannot be proved true by any number of observations of white swan—we might have failed to spot a black swan somewhere—but it can be shown false by a single authentic sighting of a black swan. Scientific theories of this universal form, therefore, can never be conclusively verified, though it may be possible to falsify them.

Hence Popper says that it is wrong to begin by accumulating observations, and it is wrong to seek confirming instances of a theory. Instead we should advance bold conjectures—derived from intuition, or creative genius, or any way we like—and attempt to refute them. Of two competing theories, the one that has run the greater risk of falsification, but has not been falsified, is the better corroborated. This does not mean that it is true—it may be falsified in the future—but it is likely to be a closer approximation to the truth than its rival. We can never, in science, know that we have discovered the truth although there is such a thing as truth, it is a regulative idea which we try to approach, but can never be sure of reaching.

There is an objection to this, urged by both Hilary Putnam and Thomas Kubn in their contributions to The Philosophy of Karl Popper; it is always possible to deny that a theory has been falsified by an observation that at first foes seem to falsify it. One can deny, for instance, that the reported sighting of a black swan was authentic; or one could say that if the bird was black, then by definition it just wasn’t a swan, no matter how much it resembled swans in other respects. In general, scientific theories are not tested in isolation, but in conjunction with other assumptions; therefore it is possible to save the theory, and explain away an observation that contradicts it, by claiming that one of the other assumptions was at fault.

Popper has not overlooked this objection; indeed, he mentioned it in his earliest writings. His reply is that as a methodological rule we should avoid “immunizing” our theories in this way, although he admits that there will be times when it is worth trying to preserve a theory despite anomalous observations.

What Popper says on this point is hardly precise, and perhaps for that reason it may not satisfy his critics; at the same time, Popper warns against the search for precision in places in which it is not to be found. We must allow ourselves to be guided by the circumstances of each case. In this way, Popper is able to retain his central point; the asymmetry of verification and falsification.

It may be helpful to illustrate this by an example, and the example that actually influenced Popper most decisively serves well. When Einstein conjectured that light rays passing close to a heavy body like the sun would be deflected from their normal path, this effect had never been observed. Newtonian physics predicted no such effect. When the observation was made and Einstein’s prediction confirmed, Newton’s “laws” were shown to be false, despite the immense amount of “verification” they had received over the centuries. It might in fact, have been possible to cling to Newton’s theory by introducing some ad hoc hypotheses to explain the observations, but to do so seemed implausible when the new theory explained matters more simply. The point is that Einstein could account for all of Newton’s successes, plus one of his failures. Newton’s theory could not stand; Einstein’s must be a closer approximation to the truth. So it survives to face further testing.

Although, as The Philosophy of Karl Popper shows, this view of science may not be unanimously accepted today, it has much support. I regard it as a huge advance upon the previously accepted idea of scientific method. Is it also a solution to the problem of induction? In two separate essays in Objective Knowledge and again in the course of his replies to his critics in The Philosophy of Karl Popper, Popper claims that it is. He complains, however, that other philosophers have not recognized his solution and he says that his critics have not understood him.

What is this notorious problem of induction? Hume’s logical problem of induction is whether we are justified in reasoning from instances of which we have experience to instances of which we have no experience. For example, we have observed the sun rising on numerous past occasions. Does this justify our belief that it will rise on a future occasion, say tomorrow?

The assumption that this belief is justifiable is, Hume said, absolutely basic to our ideas of rational belief and rational action. Without it the most carefully derived expectations are ultimately no more defensible than the bizarre fancies of a madman. Without a justification of induction, the distinction between rationality and irrationality appears to be in peril.

How does Popper answer Hume’s question? First, we must note how he interprets it. He regards it, correctly, not merely as a problem of generalizing from single cases to all cases, but as one about reasoning from past cases to a single future case. He also—perhaps less soundly, but we cannot go into that here—agrees with Hume that describing our belief about tomorrow’s sunrise as probable, rather than certain, makes no difference to the argument.

Popper then says that Hume’s question has to be reformulated. The main effect of his various reformulations is to turn the issue from a question about single cases to one about universal explanatory theories. On that reformulated issue his answer, predictably, is that observations cannot justify the claim that a universal theory is true, but they can allow us to say that it is false, and they can justify a preference for some theories over others.

Popper’s critics point out that this does not seem to answer Hume’s question. The theory that the sun rises every day may have survived falsification yesterday, but is this a reason for believing that it will survive falsification tomorrow? That was what Hume wanted to know.

Popper retorts that he has answered this question. His answer is “No.” Induction is not justifiable. That a theory has been corroborated in the past “says nothing whatever about future performance.” The best corroborated theory may fall tomorrow. “It is perfectly possible that the world at we know it, with all. Its pragmatically relevant regularities, may completely disintegrate in the next second.”

Of course universal disintegration is possible, but we appear to be justified in gambling heavily against it occuring in the next second, if only because the world has not disintegrated In any of the previous seconds of which we have knowledge, and we have no grounds for believing that disintegration is more likely in the next second than in any other second.

Hume showed, however, that this plausible argument simply assumes that past observations do justify future predictions, and if we try to defend this assumption on the grounds that those who, in the past, assumed that the future will be like the past have turned out to be right, we have again assumed what we wanted to prove. So we have an assumption that appears impossible to defend without circularity, but equally impossible to avoid making.

Popper wants to say that it is possible to avoid assuming that the future will, or probably will, be like the past, and this is why he has claimed to have solved the problem of induction. We do not have to make the assumption, he tells us, if we proceed by formulating conjectures and attempting to falsify them.

Unfortunately, we still have to act. If I did not assume that because water has come out of my tap in the past when I turned the handle the same will happen today. I might equally sensibly hold my glass under the electric light.

On this pragmatic issue Popper’s more recent contributions do have a little more to say, but it does not help. He says that, as a basin for action, we should prefer “the best-tested theory.” This can only mean the theory that has survived refutation in the past; but why, since Popper says that past corroboration has nothing to do with future performance, is it rational to prefer this? Popper says that it will be “rational” to do so “in the most obvious sense of the word known to me…. I do not know of anything more ‘rational’ than a well-conducted critical discussion.”

The reader familiar with Popper’s contempt for linguistic philosophy will rub his eyes at this. Popper has picked up that once trusty but now discarded weapon of linguistic philosophers, the argument from a “paradigm usage” of a word—in this case, the word “rational.” The argument proves nothing. As Popper himself has said many times, words do not matter so long as we are not misled by them. Popper’s argument is no better than Strawson’s claim that induction is valid because inductive reasoning is a paradigm of what we mean by “valid” reasoning. In fact Popper’s identification of a “well-conducted critical discussion” with the idea of rationality is doubly unhelpful, since until we know how to establish which theory is more likely to hold in the future we have not the faintest idea how to conduct a “well-conducted critical discussion” that has any bearing on the question we want answered.

More fundamental still is the question how, even in theory, we can possibly prefer one hypothesis to another, or take one as a nearer approximation to truth than the other, if past corroboration has no implications for the future. Without the inductive assumption, the fact that a theory was refuted yesterday is quite irrelevant to its truth-status today. Indeed, in the time it takes to say: “This result corroborates Einstein’s theory but not Newton’s,” all the significance of the remark vanishes, and we cannot go on to say that therefore Einstein’s theory is nearer to the truth. So jettisoning the inductive assumption makes nonsense of Popper’s own theory of the growth of scientific knowledge. ‘While it is true that on Popper’s view induction is not a means of scientific discovery, as it was for Bacon. It remains indispensable, and the logical problem of induction is no nearer to solution than it was before Popper tackled it.

Popper’s theory of “objective knowledge,” presented in his most recent book, is less rigorous, less tightly argued than other aspects of his thought. The theory itself comes over clearly enough, but how it helps to solve important problems is not easy to discern.

Popper divides the kinds of things that exist into three “worlds.” “World 1” is the ordinary world of tables and flesh and bone—the world that materialists say is all there is. “World 2” is the ‘world of consciousness, minds, and, if you believe in them, spirits—the world that idealists say is the only real one. Duelists, of course, say that both worlds exist. Popper adds a third world, the world of objective knowledge. By this he does not mean the marks on pieces of paper stored in libraries (those are World 1 objects) nor the subjective consciousness of the import of these marks in the minds of scholars poring over them (this is World 2) but the knowledge itself, which is said to “exist” independently of being known by a conscious subject.

Popper has a point here. Humans postulate theories, but once postulated there are logical connections between these theories that are independent of human consciousness. A computer may print out formulas that are filed away without being looked at; nevertheless the stock of knowledge has been increased.

So what? It may seem an odd extension of our ideas of “existence” to apply them to knowledge in this sense, but if Popper wishes to do so there seems little harm in it. Equally it is unclear what is gained.

Magee, of course, thinks an enormous amount is gained, but he does not explain how. Popper himself has not used the theory to solve major philosophical problems; at most he has suggested that attention should be shifted away from traditional problems toward those his theory can handle. Thus, in reply to Feigl and Meehl’s case for determinism, Popper says that what concerns him is not the refutation of determinism, but the demonstration of “the openness of World 1″—that is, the fact that the physical world may be affected by the mental world and the world of objective knowledge. In some contexts this is an important point to make, but it is quite compatible with the truth of determinism. Similarly Popper does not actually offer a solution to the problem of the relation between minds and bodies, he merely says that the problem is altered once we admit the existence of World 3 and its interaction with World 1 via World 2.

However, if the theory of objective knowledge is taken up and applied it may prove fruitful. It should in any case be a healthy influence against excessive subjectivism in fields like art, literature, and perhaps even morality. These activities, Popper wants to say, are human inventions but not merely the expression of subjective human feelings. Just as mathematics is in some sense an invention of the human mind, but still subject to objective criteria, with real problems and right or wrong answers to them, so art, for instance, sets its own problems, and solves or fails to solve them.

Unfortunately the application of the theory to fields like art and morality is only hinted at, and none of the essays in either Objective Knowledge or The Philosophy of Karl Popper attempts a detailed application. Part of the trouble is that Popper has neglected one of his own sound maxims/?/ start from a specific problem and previous attempts to solve it. Instead, the theory of objective knowledge is an attempt to “enrich our picture of the world.” This does not suit Popper’s argumentative style. The change of approach leads. Magee astray to such an extent that he excitedly reports the success of the idea in illuminating a variety of fields, apparently oblivious of the un-Popperian methodology this implies. Whereas in an earlier chapter Magee criticized psychoanalysis and Marxism on the grounds that “once your eyes were opened you saw confirming instances everywhere, the world was full of verifications of the theory,” now he so far forgets himself as to report that Popper’s theory accounts for “virtually all processes of organic development,” “all learning processes,” mathematics, art, human relationships, etc. Magee fails to ask what would falsify the theory—a question to which there is no easy answer.