Make sure you listen to this podcast before you get the news

Atul Gawande tries to figure out what’s wrong with that conversation where the patient and the doctor try to decide whether to escalate treatment or decide enough is enough. And he tells us how that conversation went with his daughter's piano teacher.

A wonderful lecture.

Social media as ed tech: circa 1899

A new cry from the beloved country

The main goal of colonialism was to plunder the colonialised. So decolonialisation must be a good thing. Surely? I’m not here to tell you it wasn’t. Nor am I an apologist for colonialism. Still, perhaps it’s worth saying the unsayable. Knowing what we know now, you wouldn’t want to be too confident that decolonisation was such a great thing.

Ditto Apartheid — which I opposed then and oppose now. Not just back then in South Africa but also today in Palestine. Just (as Socrates was wont to say) without much confidence that I know what the fuck I’m talking about.

Here’s the latest from our intrepid correspondent trying to figure out stuff, given his post-school realisation that his education on broader social and political questions was little more than a bunch of clichés and question-begging platitudes. (For which I would like to offer my condolences from Boomers everywhere. It may not be much by way of consolation, but it was a stuff-up, not a conspiracy — promise.)

Here are some brief statistics conveying the severity of its problems:

South Africa has a Gini coefficient of ~67, meaning it has the world’s highest level of income inequality. Its Gini coefficient was 0.59 in 1994.

The real unemployment rate is estimated at around 44.1% of the population

The average citizen spent 19.9% of 2023 with zero power due to rolling blackouts

South Africa’s homicide rate in 2022-2023 was 45 per 100,000 people, one of the highest in the world and a 50% increase from 2012-2013

South Africa has the world’s largest private security industry with over ~10,000 private security companies, reflecting the failure of the state to provide critical public services like policing and public safety

0.01% of the population (3500 people) owns 15% of national wealth. …

The country’s growing political and social instability is what many South Africans find the most concerning of all. These fears were spectacularly validated in 2021 when an entire province- KwaZulu Natal- collapsed into a state of total anarchy, mob violence and looting, galvanised by the active incitement of embittered former President Jacob Zuma. Many South Africans fear that this unprecedented episode of civil breakdown only marks a glimpse of things to come, given the country’s present trajectory. …

The problem is political

The reason for this dismal state of affairs, put simply but accurately, is the ANC. Morally and politically triumphant in the wake of dismantling Apartheid, the party of Mandela has revealed itself with time to be a profound disappointment. …

‘Load shedding’- the euphemism for regular self-imposed power blackouts needed to avoid total grid shutdown- is in large part due to the capture of the public energy sector by organised crime and ANC corruption. Billions of dollars earmarked for maintaining South Africa’s ageing energy infrastructure are siphoned into the pockets of officials. Coal theft syndicates steal high-quality black coal and sell it on the black market; gangs take advantage of load shedding to steal tens of thousands of kilometres of copper cabling. …

At this point, the ANC has transitioned from political party into outright political mafia, with an explicit policy of inserting political cadres across the entirety of the public sector to tighten its grip on power. …

The main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), is informally but potently understood as being the party for white people (who constitute ~7% of the population). As such it has a terrible problem with attracting votes and politicians from the country’s black majority, meaning its vote share is permanently restricted to within 20-30%. This is why the DA has formed a coalition with over 10 other parties to form a Multi-Party Charter, hoping to win enough seats to be able to form a winning majority against the ANC.

The other major player in South Africa is the EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters), which despite only beginning in 2014 has risen rapidly to become the country’s third largest party, to the point that it is now placed to challenge the DA as the official opposition party. This is deeply concerning. The EFF is a Marxist-Leninist, black nationalist party led by radical demagogue Julius Malema, who is on the record refusing to rule out that he would call for the future killing of white people in South Africa. (The video below is quite remarkable)

Under Malema … the EFF is amassing momentum and the latest polling has the EFF hovering around the 20% share of the national vote- about the same as the DA.

And yet unbelievably, the EFF are not the most dangerous political force operating in South Africa today. The 2024 elections are haunted by the spectre of Jacob Zuma, who is on the vengeful warpath against the ANC with the openly militaristic MK (uMkhonto we Sizwe) party. The MK have openly threatened large-scale violence if they are barred from running by the courts:

“We are sending a loud and clear message to the ANC that if these courts, which are sometimes captured, if they stop MK, there will be anarchy in this country. There will be riots like you’ve never seen in this country. There will be no elections. No South Africans will go to the polls.”

Closing the gap: Whatevah …

While we’re on stuff about which most of us have strong views but none of us really understands, I discovered Michael Dillon as one of the truth-tellers when I was writing My Big Piece how incoherent the PC’s report on Indigenous evaluation strategy was. Here is Dillon again with a report from the front. It cuts through the bureaucratic bland-out, but still leaves me a little unsatisfied. He says that the answer isn’t just more funding and better-organised government, but that’s pretty much all he writes about. The elephant in the room, or perhaps the other elephant, is how much money can be spent on things that don’t work because they don’t manage to mobilise indigenous agency.

It’s fair enough that Michael doesn’t cover all bases. However, this was my two cents worth in My Big Piece:

The system can only sustainably expand what works by bolstering the status of the individuals and communities who have made it work and giving them much more authority and resources within that system. … Those in the system need to be made accountable not just for talking about expanding what works but for making sure it happens, despite the discomfort it will undoubtedly cause. To that end, a regular report could be [made], by the auditor-general or some other independent guardian of integrity in the system, to document, say every two years, what progress was being made towards this goal of spreading “what works” and particularly the increasing empowerment of those who make it work.

Anyway, Matt’s words are to be read to the theme of “we’re here because we’re here, because we’re here because we’re here”. You’ll be shocked, SHOCKED — as I was — to read that progress has not been better. It’s almost as if those in charge are trying to achieve something else.

The problem is clear in the latest Closing the Gap annual report, a masterful example of sophisticated political management and bureaucratic obfuscation. This tightly organised combination of new and previous policy commitments, 2023 achievements and key actions for 2024 purports to outline the Commonwealth’s strategic priorities for the next year. But closer analysis reveals deep-seated flaws in policy design, strategic omissions and evasions and a deep-seated lack of ambition, all wrapped in a slick presentation replete with selective case studies, graphics, some useful governance charts and an avalanche of uninformative facts and figures. There is nothing strategic about this document.

Who’d have thought?

Despite their tactical and ideological differences, both major parties have used excessively complex bureaucratic processes, extremely low transparency, high-flown promises and the tactical politicisation of specific issues to divert attention from more important underlying issues. Their guiding principles appear to be to deflect, defer and delay. …

To take just one important example, the agreement identifies nineteen targets and four priority reforms and allocates responsibility for implementation to eight state and territory jurisdictions along with the Commonwealth and the Australian Local Government Association. The Coalition of Indigenous Peaks — which itself has a nascent federal structure in each state and territory — is also ostensibly an equal partner.

No line of sight nor responsibility exists between any one target and any one government or minister … . National-level data is deficient across all targets and all four priority reforms, at least partly because the targets themselves have been poorly chosen and loosely specified. Most importantly, the targets are not aligned with dedicated investment strategies. …

Instead of bringing macro-level strategic coherence the four priorities have been converted into arenas of micro-focused navel-gazing. [It’s impossible to understand this given how all four priorities were represented in a very natty diagram. NG] While the agreement requires each jurisdiction to publish an annual report and develop an on-going implementation plan, the joint council that manages its operation decided some years ago to shift to annual implementation plans, adding a further layer of process. Instead of being a roadmap laying out each jurisdiction’s multi-year pathway to each target, the plans merely recount innumerable actions and funding decisions, most with limited timeframes.

The latest Commonwealth implementation plan lists sixty-five commitments of varying significance; state and territory plans are generally much more complicated. A requirement that jurisdictions explain how they would “close the gap” has been transformed into a requirement to publish a profusion of meaningless facts and intentions to develop plans. …

All in all, the latest Closing the Gap report makes for depressing reading. It comes across as a convoluted box-ticking exercise, overflowing with plans, partnership committees, good news stories and the like. It makes no serious attempt to look behind the available data to acknowledge and reflect on the challenges of those families caught up in extreme poverty, cycles of alcohol-and drug-induced despair, youth suicides, and the trauma of extraordinary rates of incarceration and unfathomable out-of-home-care rates for Indigenous children.

The report’s implicit agenda is to defer committing financial resources, and delay making difficult decisions. … In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. famously wrote that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.” It is time the government commissioned an independent strategic review of the Indigenous policy domain, akin to the recent 2023 Defence Strategic Review, aimed at bringing a much greater degree of discipline, rigour and, most importantly, urgency to a worsening crisis blighting the life opportunities of many tens of thousands of First Nations citizens.

The fact that the depth and severity of this crisis is largely invisible to most Australians increases the responsibility on governments to act; it is not an excuse or rationale for inaction.

We need more loons running the place

Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Do we really want our rulers attending universities all over the world?

Intimations of Margaret Preston

When I happened on Kate Jarvik Birch’s picture above, I naturally thought of my favourite Margaret Preston painting, Implement Blue in the NSW Art Gallery. (Below)

From a brief article in the American Chronicle.

Birch finds inspiration in everything. Sometimes she even paints what she had for breakfast. “We infuse all the things around us in our everyday lives with memories, you know?” she says. “And we don’t even realize that we’re doing it because they’re kind of the background of our lives. But every once in a while, one object will end up meaning more than we realize.” Viewers have found immense meaning in her depictions of the mundane objects of our lives—a stick of butter, a leftover cupcake, a stack of crayons. Several years ago, for example, she painted a small rendering of cranberry sauce on Thanksgiving. “I remember my mom saying, ‘Nobody is going to buy that, that is the weirdest painting, why did you do that,’” she recalls. “The woman who ended up buying it was so emotional because her mom had just died fairly recently, and they had this inside joke about cranberry sauce, so it spoke to her so vividly and brought up so many memories for her.”

Cruel but fair

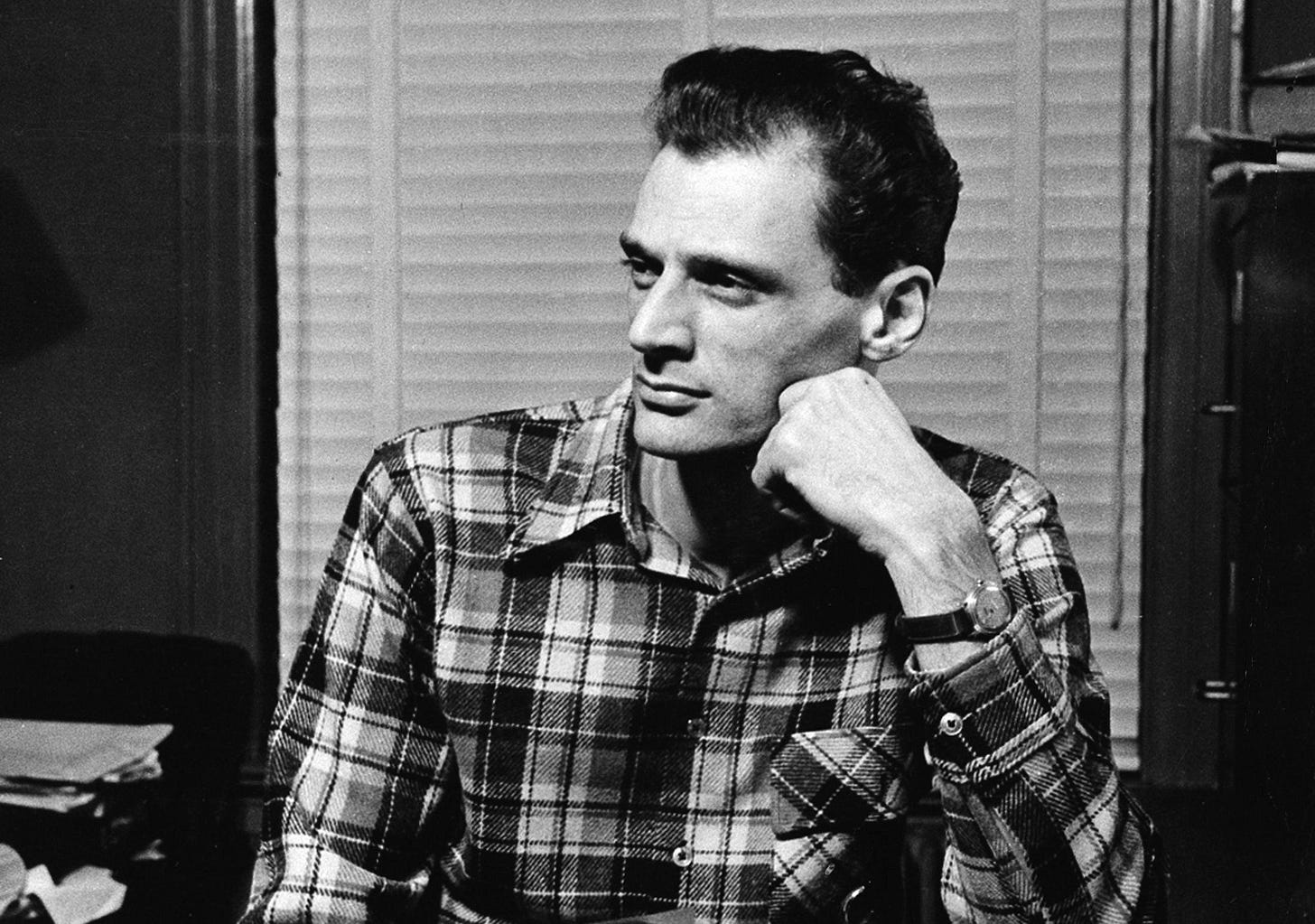

The great Arthur Miller explains himself

From the Atlantic.

In april 1948, the 32-year-old playwright Arthur Miller set out to build a 10-by-12-foot studio—two windows, clapboard walls, a desk fashioned from an old door—on land he’d bought in rural Connecticut. Once it was done, he sat down and began to write. By the next morning, he had completed the first act of what would become his most famous work; he’d known only its opening lines, he said, and that it would end in the calamity presaged by its title, Death of a Salesman. The play was finished in six weeks, and it debuted 75 years ago, on February 10, 1949.

Eight months into the play’s Broadway run, Miller answered a letter from Barbara Beattie, a junior at the University of Richmond who had reached out as part of an assignment for a journalism class. Beattie’s daughter discovered Miller’s letter while helping her mother, now 94, move out of her home. … Beattie received an A in the class.

Oct 5, 1949

Dear Miss Beattie;

If there is a formal genesis of Death of a Salesman it certainly is in the Elizabethan drama, particularly Shakespeare. From the point of view of form I have long felt that the spaciousness of his plays had been forfeited for a physical concentration which contradicts life itself. I have learned from him, if you will, that words themselves are the best scene setting; that it is not necessary to devise elaborate plot machinery in order to “set” a scene which itself can explain itself—in short, to proceed to the meat of a scene at once and to make it happen where and when it logically would happen, and not where a stationary setting forces it to happen.

As well, my form is one which permits time for what in effect are soliloquies. As I see it, the force of the Elizabethan form lay in its ability to follow the mental processes of its protagonists wherever they might lead. The same may be said of mine. This cannot be said of the “realistic” form, called Ibsen’s, which itself imposes upon the story and the characters instead of following them, making way for them. In such plays incredible ingenuity, and much time, is wasted in the mere effort to justify the simple meeting of two characters.

The history of man is his blundering attempt to form a society in which it pays to be good.

Concerning the idea of Elizabethan tragedy and my own, I could speak for many hours. Central to Shakespeare’s tragedy is the idea of the Fall, which implies social stature of a royal level. I too see the Fall as a critical aspect of tragedy, but our world has changed, and it is no longer possible to think of the Fall as that of a socially elevated person exclusively. But social status, to my mind, was and is only a superficial expression of a deeper Fall, so to speak, namely, the destruction of a man’s idea of what he is by forces opposing him. Any class is thereby given entrance to the precincts of the tragic, and so it is in a democratic society. Under Elizabethan feudalism this notion was unthinkable if only because none but the royal had the alternatives of seemingly absolute choice, the liberties of the masses being hedged about by all sorts of rigid proscriptions.

Today we are all “free” to aspire to any height, we have the hero’s necessary alternatives. My moral object, therefore, is to attempt to direct the efforts of men toward the clear appreciation of reality, exposing the illusory in order that man may realize his creative potentialities. In another context, Shakespeare was attempting the same thing, as in the history plays where the catastrophe derives from the impossible ambitions of the monarch or those of the subjects against the monarch. A certain ideal order is therefore implied as having been violated in his work, and in mine. His ideal was feudal; it supposed that life would be good when men behaved in accordance with their social position and neither lapsed into a lower level, (Prince Hal), nor created havoc by attempting to crash into one above them, (The King in Hamlet ).

My ideal order is less easy to formulate if only because it does not yet exist, while he was writing within a society whose theory was sufficient for him. I see man’s happiness frustrated until the time arrives when he is judged, given social honor and respect, not by what he has accumulated but by what he has given to his society. This ideal is posited not for itself, but because I know that the frustration of the creative act is the cause of our hatred for each other, and hatred is the cause of our fears. We reward our dealers, our accumulators, our speculators; we penalize with anonymity and low pay our teachers, our scientists, our workers who make and do and build and create. And so the urge that is in all of us to give and to make is turned in upon itself, and we accept the upside-down idea that to take and to accumulate is the great good. And whether we succeed in that or not, we are sooner or later left with the awareness of our emptiness, our inner poverty, and our isolation from mankind. When a man reaches that knowledge and has the sensitivity to feel the loss of his true self deeply, he is a tragic figure; but not unless he tries to find himself despite the world can he raise up in us the actual feeling that something fine and great and precious has been discovered too late. The history of man is his blundering attempt to form a society in which it pays to be good. The tragic figure now, and always, is the man who insists, past even death, that the stultifying combinations of evil give way before the outpouring of humanity and love that is bursting from his heart. This is why tragedy endures, and this is why it has really never changed excepting in its superficial aspects of rank etc.

I hope some of this has been clear. I write at such length because there are not many who have taken the trouble to examine the matter at all.

Sincerely yours,

Arthur Miller

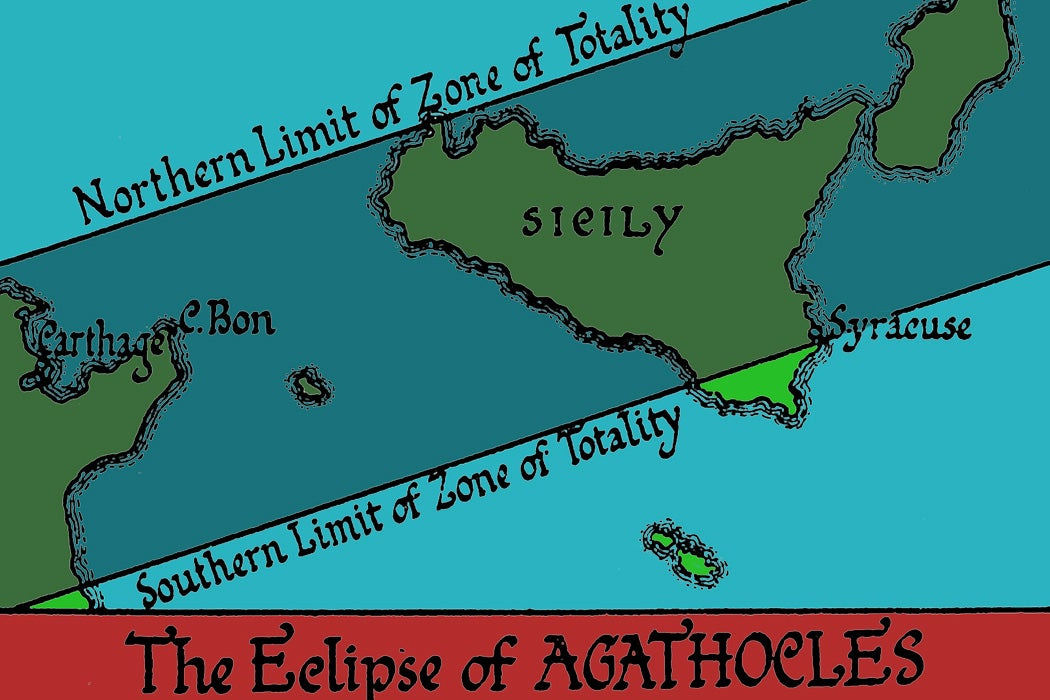

The eclipse of Agathocles

There was panic down in Concepts Division when someone mentioned that, in over two years of operation, we’d effectively erased the dating of the eclipse of Agathocles as we’d ponced on about Ukraine, Israel and the usual culture war fodder on slow weeks.

Of course, it was inadvertent, but that’s what they said about slavery. In any event after a quick word with our newsroom, this article was uncovered:

Among the many stories of the ancient world described by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus was a battle in Western Asia between the Medes and the Lydians. The fight was notable mainly for the fact that it was interrupted when “day was on a sudden changed into night,” after which the warning parties quickly agreed to make peace. …

Two millennia later, astronomers sought to use their knowledge of celestial mechanics to determine just when this apparent solar eclipse occurred. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, scientists including Isaac Newton took up the question but failed to reach a consensus. Estimates ranged from 626 to 583 BCE.

In 1811 British astronomer Francis Baily tried… using newly developed tables for calculating the Moon’s motion. He confidently wrote that the battle had actually taken place on September 30, 610 BCE. Yet when Baily tried to date other eclipses mentioned in ancient Greek writings, he was less successful—often failing to find a time and place that even generally fit the historical accounts. Reluctantly, he suggested that it might be necessary to make “some alteration” in astronomers’ calculations of lunar movement.

In the 1850s, another British astronomer, George Airy, took the problem from the opposite direction, attempting to use historical clues to determine a factor in the Moon’s movements over the centuries known as secular acceleration. He focused his attention on a historical account of an eclipse seen by Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse, as he fled a blockade by Carthaginian forces. Airy, who had a background in classical studies himself, worked with historians and naval experts to try to figure out which route would have made most sense to the ancient figure and how quickly he could have sailed along various paths.

Airy’s methods, using historical accounts to guide astronomic theories, were widely accepted by other astronomers for a time. But in 1878, it was challenged by American astronomer Simon Newcomb. Newcomb was far more skeptical about claims regarding historical accounts of eclipses. For example, he suggested that Herodotus’s battle story may have actually described a partial eclipse, a dark cloud covering the Sun, or even just nightfall appearing to come “on a sudden” as the armies were swept up in fighting.

Newcomb was devoted to promoting a standard of scientific thinking that depended on careful training. Unlike classically trained scholars like Airy, who viewed ancient Greek scholars as something like peers, he distrusted the reports of people who had no concept of modern science.

Ultimately, it was scientific progress that solved the secular acceleration question. Reflectors placed on the Moon by Apollo astronauts allowed researchers to measure it directly. Today, astronomers are confident that a solar eclipse was visible in Western Asia in 585 BCE, but historians remain unsure about whether it really interrupted a battle.

Good piece on President Carter

Martin Wolf on democracy

Martin Wolf continues his advocacy for the proposition that representation by sampling should have a role in our democracy.

Why Does Beauty Matter?

As readers may have noticed from tweets like the one immediately above, and similar tweets from that account, I follow Culture Critic on Twitter and also now, the corresponding substack from which this post comes. I had a crack at the same question which has always bugged me a good while ago on my blog.

Recently I was completely blown away by how magnificent the Legislative Council is. I mean just take a look at it. … I wonder about Christoper Alexander’s question. Why is it that virtually every major building built before 1940 is beautiful and virtually every building built after – say – 1950 is ugly? …

One clue that I got was at a Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission roundtable on ‘liveability’. After lots of discussion about the appropriate ‘metrics’, I mucked up a little and said that I hadn’t heard anyone mention the idea of beauty. This was not regarded as a very helpful comment. Several people addressed the unease by saying that people disagreed about what was beautiful, and after the face saving gesture of mentioning the word in the report, the issue was politely dropped. …

This was an elite gathering. Full of economists, social planners of various descriptions, a writer and an academic or two. The group was chosen for its breadth. All of the rest there would have had tertiary education and most of them were relatively senior. But building a city to be beautiful, well that was pretty esoteric stuff. My sexuality wasn’t questioned. Indeed, everyone was very polite. But it was a little as if I had said that it is impossible to have a great city without a giant statue of a camel.

So what is going on?

If you’re interested in what I made of it, click through here. Meanwhile here’s Culture Critic’s take:

Plato and Aristotle identified three properties — truth, goodness, and beauty — which have the unique ability to take you to the brink of the human experience. …

What sets beauty apart from the other transcendentals is its ability to slip under your intellectual radar. You don’t have to analyze the meter of Beethoven’s Cavatina before it brings tears to your eyes. A sunset’s glow or a lovely face makes you catch your breath instantly, not after a long examination.

Beauty is hard to define precisely because it bypasses your analytical shields and grasps directly at your heart. …

We already touched on the way beauty functions as the meeting place between the limitations of our lives and the invitation to the infinite.

In fact, you could say this is the primary role beauty serves in every culture.

In this sense, beauty is the link between culture and spirituality. It lifts our eyes above our immediate concerns, putting us in touch with the greater purpose of our lives.

How can culture survive without a sense of transcendence? It’s no accident that the great cultures that shaped history — Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and more — left behind vivid mythologies as well as great art. Their spiritual reality was immediate to their daily life.

What’s more, beauty is an essential mode of passing on culture.

What inspires you more, a list of rules, or a beautiful ritual? It's probably the latter, which is why cultures enshrine their most sacred truths in beautiful stories, songs, objects, buildings, and even garments. One of beauty’s crucial roles is to keep its people united in their collective identity and safeguard truth for future generations.

That’s why beauty is such an effective way to measure the health of a culture.

And it also begs the important question:

What Happens When We Lose Touch With It?

Action on climate change

The problem with a talking cure

My colleague Gene Tunny (the economist — not to be confused with Gene Tunney, who was boxing heavyweight champion of the world from 1926 to 1928) weighs in on coal mining in Queensland. Right now we seem to be pursuing a talking cure for greenhouse emissions. We’re doing quite a lot of things quite vigorously and they’ll reduce greenhouse emissions, but there’s a lot of remarkably slipshod analysis (I’m looking at you CSIRO) and there’s this problem of intermittency. Perhaps we’ll get round it to zero emissions, but I expect we’re muddling through and we’ll have to do more than muddle to hit that milestone on time.

Despite the Queensland Government promoting the so-called Clean Economy, our state Treasury is still highly dependent on coal royalties, and the prosperity of our regional economies is highly correlated with coal mining. Coal prices remain at high levels and may deliver Treasurer Cameron Dick some additional budget billions if they don’t fall substantially by the end of the financial year. …

There appears to be widespread support for decarbonisation in advanced economies, which would imply a very challenging adjustment for Queensland. However, coal (and gas) will likely remain important to the state economy for at least several decades. There are well-known facts about two-thirds to three-quarters of our coal exports being coking coal, essential for steel production for now, and how China and India keep building new coal-fired power plants. For example, according to Reuters, India is adding nearly 14 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity this year. Worldwide, coal consumption is 75% above what it was in 1992, the year of the Rio Earth Summit, which brought in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (Figure 2). Greta Thunberg was right that all the fine words of our leaders have amounted to nothing more than “Blah, Blah, Blah.” Consumption of coal is stabilising but is not yet plummeting as rapid decarbonisation advocates would like to see.

The other consideration is growing concerns that the transition to greener electricity will be rocky, with intermittent renewables making supply less reliable, for example. In my latest Economics Explored podcast interview, I spoke with Kansas City-based investment manager Ben Fraser of Aspen Funds, who is betting that the rocky energy transition will bolster demand for energy-dense, reliable fossil fuels. Ben argues:

“we’re at the early stages of an energy crisis that we haven’t seen in a long time. And it’s really going to be driven by a supply shortage of fossil fuels. As we’re making a transition into more green energy, renewable energy sources, that is really being driven by a political narrative that…at its worst is creating a huge gap of understanding of what it’s going to take to make this transition. And [we’re] really putting ourselves in a really bad position from a production and supply standpoint of fossil fuels over the next several decades that we believe is going to be pretty, pretty severe.” [at 14:55]

“And so we really believe there’s a huge opportunity to get into fossil fuel production. So we’re investing a lot into these operating wells at really good prices.” [at 27:58]

(As this picture makes clear, Gene Tunny the economist is not now, nor has he ever been the heavyweight boxing champion of the world. ed.)

… This is not to deny we need to respond to climate change over the coming decades. But it probably won’t be by sharply cutting coal consumption anytime soon. Physicist Sabine Hossenfelder is probably right that, globally, we’ll have to undertake risky climate engineering as it will end up being the “cheapest way to get us out of this unfolding climate disaster”, as she puts it.

Very cool that you can teach a dog the rules of volleyball

Be grateful for great, grateful beasts

Intriguing

Is Cordelia real?

I loved having this pointed out to me, as I was too uneducated to know it already. Then again, as someone once said, there are more things in heaven and earth. The extract below is the entirety of the unpaywalled beginning of a paywalled post.

In May 1994, an undergraduate called Pamela Bunn posted a comment in the online community known as Shaksper, asking about Cordelia’s “character development.” Bunn was wondering how to best convey on stage all the large emotions Cordelia would be feeling in the opening of King Lear. Terence Hawkes, one of the academics who brought the ideas of Derrida, Foucault and other post modernists to Britain, responded like this:

Cordelia is not a real, live flesh and blood human being. In consequence, she has no ‘character’, and it does not ‘develop’. To suppose otherwise, as your teachers have apparently encouraged you to do, is to impose the modes of 19th and 20th century art on that of an earlier period which knew nothing of them. It is, in short, to turn an astonishing and disturbing piece of 17th century dramatic art, whose mode is emblematic, into a third rate Victorian novel, whose mode is realistic. Cordelia has no private motives, or emotions, other than those clearly presented in the play as part of its thematic structure. The play uses her to raise matters of large public concern such as duty, deference, the nature of kingship, the right to speak, the function of silence, the roles available to women in a male-dominated world, and so on. These are not the newly-minted slogans of wild-eyed Cultural Materialist revolutionaries, but the fundamental principles on which informed and entirely respectable analysis of the plays has proceeded for fifty years and more. Read the fine and justly famous essay by L.C.Knights, “How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth?”. It was first published in 1933.

Another way of putting this is to say that the whole play (and only the words of the play) is what matters, not what Knights calls the abstractions of the plot and characters. To talk about Cordelia’s motivations and thoughts is to talk about something not written, and is thus bad criticism. On this view, the characters of the play are not persons, but are “symbols of a poetic vision.”

The historical argument for this perspective is that drama before the age of Shakespeare was largely that of the morality play, in which archetypes were used to make moral points. The most obvious descendant of that sort of drama are the characters in Ben Jonson who represent certain “humours”—these are not individuals, but types, comparable with the work of the Roman playwright Terence. To the contemporary audience, Shakespeare was more like this, part of a culture of sermons and speeches.

Here is how Knights expressed the argument:

A Shakespeare play is a dramatic poem. It used action, gesture, formal grouping and symbols, and it relies upon the general conventions governing Elizabethan plays… its end is to communicate a rich and controlled experience by means of words—words used in a way which, without some training, we are no longer accustomed to respond… To stress in the conventional way character or plot or any of the other abstractions that can be made, is to impoverish the total response.

He then quotes two other critics, first M.C. Bradbrook,

It is in the total situation rather than in the wrigglings of individual emotion that the tragedy lies.

And then G. Wilson Knight,

We should not look for perfect verisimilitude to life, but rather see each play as an expanded metaphor… The persons, ultimately, are not human at all, but purely symbols of a poetic vision.

But impressive as Knights’ essay is (and Hawkes was summarising Knights), what does it amount to? As a commenter on Shaksper said, “We are all deeply indebted to Terence Hawkes for alerting us to the remarkable discovery that fictional characters aren’t real people.”

Seeing the text as a whole doesn’t negate the idea that character matters. The argument is really to declaim a single vision of drama for the period, and then to assume Shakespeare fits that vision rather than alters it.

Indeed, Knights’ basic argument—that we cannot infer anything about a character that is not stated in the text—is flat wrong.

The rest of this essay is for paid subscribers. Below the paywall, you can find out why L.C. Knights was wrong. (But also a little bit right...) And you’ll learn the difference between “opaque” and “transparent” criticism, one of the most useful models for how we talk about literature.

A paid subscription gives you access to essays where you learn the different ways of understanding and interpreting works of literature. If you want to cultivate your taste through deeper knowledge and increased insight, become a paid subscriber today. It’s approximately the cost of a cup of coffee once a week, but gives you access to all my writing. And you can join our book club sessions (usually 7pm, UK time, monthly, on a Sunday; I’m open to other times.)

Hubris: Bush’s abated in retirement. Tony Blair’s didn’t

No animals were harmed making this video

But there was no cheering up the girl

Transitioning: from Wall St Journal neoliberal to a New Deal supporting neo-reactionary, from atheist to catholic

What makes people change their mind? And why does Heinz Arndt’s confession so often apply to them?

In my own case, these political prejudices (if not, I would like to think, the moral convictions) underwent great changes over half a century, from a brief youthful Marxist phase to decades of Fabian-Keynesian views which gradually gave way to … a sceptical – monetarist near-libertarian position … It might be thought that such an odyssey would induce a decent humility: if I could be so completely wrong earlier what grounds of confidence have I that I am right now? I can only shamefacedly report that this has not been my experience. [LOL: Ed.]

To adopt an old joke which doesn’t do the rounds of politics as much as it did just as it was becoming acceptable to say risque things, Ahmari’s had more positions than the Kama Sutra. I wondered why I should have any interest in his latest incarnation. I’m not sure that I do. But he does speak eloquently about how he changed his mind. I was fascinated with the earlier part of this podcast, where Ahmari describes his presence among the refugees heading for Europe and the disconnect between his experience and its representation on mainstream media. As Andrew Sullivan, not a Catholic convert, but born and raised as one, mentions in his shownotes:

We clashed a little, but I also gave him space and time to explain his own strange journey to this brand of neo-reactionism. In my view, his biography tells you a lot about his need for moral and political “absolutes.” In my book, that makes him close to the opposite of a conservative.

I found it pretty interesting up to and including some of the stuff on the conversion. And then I kind of got the hang of the guy. And his desire to present himself as ‘post-liberal’. Like lots of other folks who style themselves in the same way — I’m looking at you Patrick Deneen — beyond the objections to the state we’re in, there wasn’t much of a ‘there’ there.

Cute

Applying the Judeo-Communist theory in Australia: the Australian Security Intelligence Organization and the Australian Jewish community

Philip Mendes

I caught up nearly a year ago now with Prof Philip Mendes from Monash University to talk to him about his area of specialty, which is out-of-home care for kids. In our discussion he mentioned he was doing some research on the way ASIO and its forerunner organisations targeted Jews for surveillance on the grounds that — well Jews are communists. I mean if it’s good enough for Hitler, it’s good enough for me. My Dad was Jewish and he was a communist. Well he wasn’t actually, but I think you get my point. Anyway, Philip recently sent me an article he was publishing on the subject and I asked if he could condense it to 1,500 words. He agreed, and here is the result.

In a 1938 report by the Commonwealth Investigation Branch, an Inspector Mitchell described a prominent Australian Jewish progressive Hirsch Munz as ‘arrogant’, and consequently ‘the type that gives some understanding of Hitler’s attitude towards the Jews’.

These anti-Semitic stereotypes presented by Mitchell were arguably widespread in Australian security circles in this period. In a recently published book chapter,

I examine ASIO and its predecessor organisations obsessive investigation of alleged links between Australian Jewry and Communist activities from the early 1930s till about the early 1960s. ASIO’s targeting of both Jewish individuals and Jewish organisations arguably reflected a soft application in Australia of the Judeo-Communist theory, the belief propagated by the Nazis and other far right European anti-Semites that Jews secretly created the World Communist movement in order to achieve global power. That conspiracy theory was employed as a key rationale for enabling the murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust.

To be sure, some leading Communists in Europe and elsewhere (i.e. most notably Trotsky) were Jews. But most prominent Communists globally were not of Jewish background, and most Jews were not Communists.

In Australia, some sections of the Jewish community – particularly those who had migrated from Eastern and Central European countries where right-wing regimes persecuted Jews – were sympathetic to socialist and communist causes. That identification was reinforced by the Soviet Union’s strong (albeit short-lived) support for the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the anti-racist solidarity provided to Jews by the Communist Party (CPA) and other left-wing groups in that era.

But most of the small Australian Jewish population, which totaled only 35,000 in 1947 before rising to 53,000 by 1952, were not aligned with progressive groups. And even many Jewish progressives were alienated by the increasing evidence of institutionalized anti-Semitism emanating from Stalin’s Soviet Bloc as reflected in the widely reported Slansky show trial of late 1952 in Czechoslovakia and the Doctors Plot of early 1953 in the Soviet Union.

Yet oddly, ASIO framed all Jews as potential subversives. It was arguably not surprising – particularly once the Cold War began – that they monitored the leading Jewish Left group, the pro-Soviet Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism (JCCFAS) and other Jewish groups connected to the CPA. However, their concern with alleged Jewish links to subversive activities went way beyond progressives, and included probing a diverse range of Jewish organisations including Zionists, cultural centres, student groups, the social democratic but fiercely anti-Communist Bund, peak community leadership bodies, and even the Jewish welfare agency. They also investigated many committed anti-Communists including the future Governor-General Sir Zelman Cowen, the pro-Israel academic Professor Julius Stone, and the conservative Jewish community leader Isi Leibler.

ASIO’s disproportionate targeting of Jews seemed to reflect assumptions about Jewish connections with Communism that dated back to the early 1930s. It’s not evident how these prejudices directly seeped into the security services perspective, although it seems that some far Right British operatives may have shared them with Australian colleagues. Regardless, it seems to have been embedded in their thinking by World War Two when a plethora of reports aligned Jews, particularly those of Eastern European background living in inner city Melbourne suburbs, with Communist activities.

During the war, ASIO actively investigated alleged connections between Jewish communities and Communism in every state of Australia. This was despite the fact that Jewish numbers outside the major capital cities of Melbourne and Sydney were tiny. ASIO operations even included a monitoring of sermons by leading (anti-Communist) Rabbis such as Dr Herman Sanger of Temple Beth Israel in Melbourne during the Jewish high holy days. ASIO also erroneously assumed that Jewish (pro-Zionist) criticisms of British policy in Mandatory Palestine were aligned with Communist views, despite the long-term ideological conflict between Communist and Zionist perspectives.

The security obsession with Jewish/Zionist links to Communism probably reached its peak in May 1950 when the Victorian Special Branch police, influenced by the proposed Communist Party Dissolution Act, questioned a number of Jewish youth in Melbourne about their political activities. Some were members of a pro-Communist group, but others were aligned with a moderate labor Zionist group. The police reportedly threatened some of the young people, who had been born in Europe, with deportation, and the affair caused major anxiety amongst Melbourne Jewry. Following media and Labor Party criticism, Prime Minister Menzies felt obliged to deny in Parliament that ASIO officials were involved in this affair or had asked the Victoria Police to undertake any action.

Much of my book chapter covers ASIO’s long-term investigation of the progressive JCCFAS and its alleged Communist links from its founding in 1942 till at least the early 1960s. I also examine ASIO’s personal investigations of Council personnel such as Norman Rothfield, Judah Waten, Aaron Mushin, and members of the Komesaroff family However, despite many years of recording phone conversations, photographing meetings, reporting personal and business relations, monitoring international travel, and photocopying media reports of public events, ASIO never found any ‘smoking gun’. None of the Jewish organisations or individuals investigated were ever determined to have participated in or incited violent or illegal activities that would reasonably be judged as a security risk. It is hard not to disagree with a member of the Komesaroff family who reflected that ASIO failed to discriminate between legitimate political ‘dissent and disloyalty’, and hence wasted an enormous amount of taxpayer resources spying on his family and others.

But that comment also raises the question as to whether or not ASIO’s obsession with an alleged Jewish-Communist nexus caused any significant harm. On the one hand, Australia did not witness any trials of Jewish Communists who were accused of spying for the Soviet Union. There was no Rosenberg-type case in Australia, although a few Jews were named at the 1949-50 Victorian Royal Commission into Communism, and some Jews were interrogated at the 1954 Royal Commission on Espionage. But none of those named or interrogated were ever convicted of espionage, and despite the best efforts of the far-Right anti-Semitic League of Rights, it seems few Australians were aware of this alleged Jewish connection with Communism.

However, some Australian Jews were definitely harmed by ASIO actions. One example that I don’t discuss in my chapter was that of Professor Bernard Rechter, a pharmaceutical researcher and educator, who was active in Jewish community affairs and a member of the Communist Party from about 1943-56. Rechter had two ASIO files, which document his varied political activities such as protesting the arrival of the West German Ambassador, and speaking to a JCCFAS forum on the contentious question of Soviet anti-Semitism.

Notably, they also document repeated attempts by ASIO to undermine his employment opportunities. For example, he secured employment at the CSIRO and RMIT, and both times ASIO advised the employers to withdraw their offers. However, the Kiwi Shoe Polish company in Burnley St. Richmond employed Rechter in their manufacturing laboratory as an industrial chemist, and courageously refused to bow to ASIO demands to dismiss him. An ASIO report in November 1953 noted drily that ‘there is no evidence that he has at any time discussed with fellow employees matters pertaining to Communism, neither has he made any subversive utterances’ (Note 28, NAA: A6119, 99). And this was precisely the point. Rechter was a gentle intellectual who went onto to become the founding director of the Australia Centre of Jewish Civilisation at Monash University in 1992. He posed no security threat at all, yet ASIO actively sought to undermine his career advancement.

In my chapter, I conclude that ASIO’s essentializing of Jews as Communists was historically and politically inept. It displayed little understanding of the key role that the Judeo-Communist theory had played in persuading the Nazis and other European peoples in the first half of the 20th century to participate in the mass slaughter of European Jewish populations. ASIO failed to consider the potential harm that its application could inflict on the welfare of Jews living in Australia.

Heaviosity half-hour

Hannah Arendt on Eternity versus Immortality

Over my head, but hey, this is heaviosity half-hour. And it’s good food for pondering. The kind of thing that might provoke my tiny mind to some insight one day.

That the various modes of active engagement in the things of this world, on one side, and pure thought culminating in contemplation, on the other, might correspond to two altogether different central human concerns has in one way or another been manifest ever since “the men of thought and the men of action began to take different paths,” that is, since the rise of political thought in the Socratic school. However, when the philosophers discovered—and it is probable, though unprovable, that this discovery was made by Socrates himself—that the political realm did not as a matter of course provide for all of man’s higher activities, they assumed at once, not that they had found something different in addition to what was already known, but that they had found a higher principle to replace the principle that ruled the polis. The shortest, albeit somewhat superficial, way to indicate these two different and to an extent even conflicting principles is to recall the distinction between immortality and eternity.

Immortality means endurance in time, deathless life on this earth and in this world as it was given, according to Greek understanding, to nature and the Olympian gods. Against this background of nature’s ever-recurring life and the gods’ deathless and ageless lives stood mortal men, the only mortals in an immortal but not eternal universe, confronted with the immortal lives of their gods but not under the rule of an eternal God. If we trust Herodotus, the difference between the two seems to have been striking to Greek self-understanding prior to the conceptual articulation of the philosophers, and therefore prior to the specifically Greek experiences of the eternal which underlie this articulation. Herodotus, discussing Asiatic forms of worship and beliefs in an invisible God, mentions explicitly that compared with this transcendent God (as we would say today) who is beyond time and life and the universe, the Greek gods are anthrōpophyeis, have the same nature, not simply the same shape, as man. The Greeks’ concern with immortality grew out of their experience of an immortal nature and immortal gods which together surrounded the individual lives of mortal men. Imbedded in a cosmos where everything was immortal, mortality became the hallmark of human existence. Men are “the mortals,” the only mortal things in existence, because unlike animals they do not exist only as members of a species whose immortal life is guaranteed through procreation.18 The mortality of men lies in the fact that individual life, with a recognizable life-story from birth to death, rises out of biological life. This individual life is distinguished from all other things by the rectilinear course of its movement, which, so to speak, cuts through the circular movement of biological life. This is mortality: to move along a rectilinear line in a universe where everything, if it moves at all, moves in a cyclical order.

The task and potential greatness of mortals lie in their ability to produce things—works and deeds and words—which would deserve to be and, at least to a degree, are at home in everlastingness, so that through them mortals could find their place in a cosmos where everything is immortal except themselves. By their capacity for the immortal deed, by their ability to leave nonperishable traces behind, men, their individual mortality notwithstanding, attain an immortality of their own and prove themselves to be of a “divine” nature. The distinction between man and animal runs right through the human species itself: only the best (aristoi), who constantly prove themselves to be the best (aristeuein, a verb for which there is no equivalent in any other language) and who “prefer immortal fame to mortal things,” are really human; the others, content with whatever pleasures nature will yield them, live and die like animals. This was still the opinion of Heraclitus, an opinion whose equivalent one will find in hardly any philosopher after Socrates.

In our context it is of no great importance whether Socrates himself or Plato discovered the eternal as the true center of strictly metaphysical thought. It weighs heavily in favor of Socrates that he alone among the great thinkers—unique in this as in many other respects—never cared to write down his thoughts; for it is obvious that, no matter how concerned a thinker may be with eternity, the moment he sits down to write his thoughts he ceases to be concerned primarily with eternity and shifts his attention to leaving some trace of them. He has entered the vita activa and chosen its way of permanence and potential immortality. One thing is certain: it is only in Plato that concern with the eternal and the life of the philosopher are seen as inherently contradictory and in conflict with the striving for immortality, the way of life of the citizen, the bios politikos.

The philosopher’s experience of the eternal, which to Plato was arrhēton (“unspeakable”), and to Aristotle aneu logou (“without word”), and which later was conceptualized in the paradoxical nunc stans (“the standing now”), can occur only outside the realm of human affairs and outside the plurality of men, as we know from the Cave parable in Plato’s Republic, where the philosopher, having liberated himself from the fetters that bound him to his fellow men, leaves the cave in perfect “singularity,” as it were, neither accompanied nor followed by others. Politically speaking, if to die is the same as “to cease to be among men,” experience of the eternal is a kind of death, and the only thing that separates it from real death is that it is not final because no living creature can endure it for any length of time. And this is precisely what separates the vita contemplativa from the vita activa in medieval thought. Yet it is decisive that the experience of the eternal, in contradistinction to that of the immortal, has no correspondence with and cannot be transformed into any activity whatsoever, since even the activity of thought, which goes on within one’s self by means of words, is obviously not only inadequate to render it but would interrupt and ruin the experience itself.

Theōria, or “contemplation,” is the word given to the experience of the eternal, as distinguished from all other attitudes, which at most may pertain to immortality. It may be that the philosophers’ discovery of the eternal was helped by their very justified doubt of the chances of the polis for immortality or even permanence, and it may be that the shock of this discovery was so overwhelming that they could not but look down upon all striving for immortality as vanity and vainglory, certainly placing themselves thereby into open opposition to the ancient city-state and the religion which inspired it. However, the eventual victory of the concern with eternity over all kinds of aspirations toward immortality is not due to philosophic thought. The fall of the Roman Empire plainly demonstrated that no work of mortal hands can be immortal, and it was accompanied by the rise of the Christian gospel of an everlasting individual life to its position as the exclusive religion of Western mankind. Both together made any striving for an earthly immortality futile and unnecessary. And they succeeded so well in making the vita activa and the bios politikos the handmaidens of contemplation that not even the rise of the secular in the modern age and the concomitant reversal of the traditional hierarchy between action and contemplation sufficed to save from oblivion the striving for immortality which originally had been the spring and center of the vita activa.

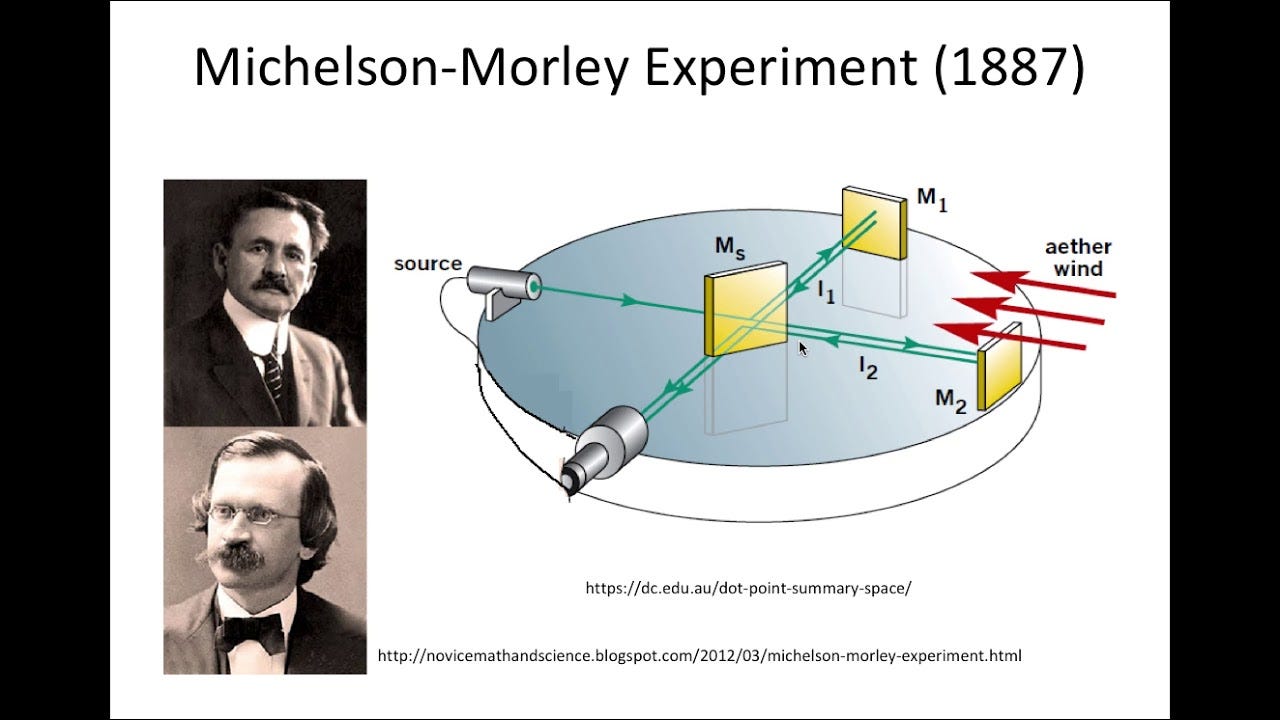

Magnificent section on relativity from Michael Polanyi

Relativity

The story of relativity is a complicated one, owing to the currency of a number of historical fictions. The chief of these can be found in every textbook of physics. It tells you that relativity was conceived by Einstein in 1905 in order to account for the negative result of the Michelson- Morley experiment, carried out in Cleveland eighteen years earlier, in 1887. Michelson and Morley are alleged to have found that the speed of light measured by a terrestrial observer was the same in whatever direction the signal was sent out. That was surprising, for one would have expected that the observer would catch up to some extent with signals sent out in the direction in which the earth was moving, so that the speed would appear slower in this direction, while the observer would move away from the signal sent out in the opposite direction, so that the speed would then appear faster. The situation is easily understood if we imagine the extreme case that we are moving in the direction of the signal exactly at the speed of light. Light would appear to remain in a fixed position, its speed being zero, while of course at the same time a signal sent out in the opposite direction would move away from us at twice the speed of light.

The experiment is supposed to have shown no trace of such an effect due to terrestrial motion, and so—the textbook story goes on—Einstein undertook to account for this by a new conception of space and time, according to which we could expect invariably to observe the same value for the speed of light, whether we are at rest or in motion. So Newtonian space, which is ‘necessarily at rest without reference to any external object’, and the corresponding distinction between bodies in absolute motion and bodies at absolute rest, were abandoned and a framework set up in which only the relative motion of bodies could be expressed.

But the historical facts are different. Einstein had speculated already as a schoolboy, at the age of sixteen, on the curious consequences that would occur if an observer pursued and kept pace with a light signal sent out by him. His autobiography reveals that he discovered relativity:

after ten years’ reflection...from a paradox upon which I had already hit at the age of sixteen: If 1 pursue a beam of light with the velocity c (velocity of light in a vacuum), 1 should observe such a beam of light as a spatially oscillatory electromagnetic field at rest. However, there seems to be no such thing, whether on the basis of experience or according to Maxwell’s equations. From the very beginning it appeared to me intuitively clear that, judged from the standpoint of such an observer, everything would have to happen according to the same laws as for an observer who, relative to the earth, was at rest.

There is no mention here of the Michelson-Morley experiment. Its findings were, on the basis of pure speculation, rationally intuited by Einstein before he had ever heard about it. To make sure of this, I addressed an enquiry to the late Professor Einstein, who confirmed the fact that ‘the Michelson-Morley experiment had a negligible effect on the discovery of relativity’.

Actually, Einstein’s original paper announcing the Special Theory of Relativity (1905) gave little grounds for the current misconception concerning the origins of his discovery. It opens with a long paragraph referring to the anomalies in the electrodynamics of moving media, mentioning in particular the lack of symmetry in its treatment, on the one hand, of a wire with current flowing through it moving relative to a magnet at rest, and on the other of a magnet moving relative to the same electric current at rest. It then goes on to say that ‘similar examples, as well as the unsuccessful attempts to observe the relative motion of the earth in respect to the medium of light lead to the conjecture that, as in mechanics, so also in electrodynamics, absolute rest is not observable....’1 The usual textbook account of relativity as a theoretical response to the Michelson-Morley experiment is an invention. It is the product of a philosophical prejudice. When Einstein discovered rationality in nature,unaided by any observation that had not been available for at least fifty years before, our positivistic textbooks promptly covered up the scandal by an appropriately embellished account of his discovery.

There is an aspect of this story that is even more curious. For the programme which Einstein carried out was largely prefigured by he very positivist conception of science which his own achievement so flagrantly refuted. It was formulated explicitly by Ernst Mach, who, as we have seen, had first advanced the conception of science as a timetable or telephone directory. He had extensively criticized Newton’s definition of space and absolute rest on the grounds that it said nothing that could be tested by experience. He condemned this as dogmatic, since it went beyond experience, and as meaningless, since it pointed to nothing that could conceivably be tested by experience.2 Mach urged that Newtonian dynamics should be reformulated so as to avoid referring to any movement of bodies except as the relative motion of bodies with respect to each other, and Einstein acknowledged the ‘profound influence’ which Mach’s book exercised on him as a boy and subsequently on his discovery of relativity.

Yet if Mach had been right in saying that Newton’s conception of space as absolute rest was meaningless—because it said nothing that could be proven true or false—then Einstein’s rejection of Newtonian space could have made no difference to what we hold to be true or false. It could not have led to the discovery of any new facts. Actually, Mach was quite wrong: he forgot about the propagation of light and did not realize that in this connection Newton’s conception of space was far from untestable. Einstein, who realized this, showed that the Newtonian conception of space was not meaningless but false.

Mach’s great merit lay in possessing an intimation of a mechanical universe in which Newton’s assumption of a single point at absolute rest was eliminated. His was a super-Copernican vision, totally at variance with our habitual experience., For every object we perceive is set off by us instinctively against a background which is taken to be at rest. To set aside this urge of our senses, which Newton had embodied in his axiom of an ‘absolute space’ said to be ‘inscrutable and immovable’, was a tremendous step towards a theory grounded in reason and transcending the senses. Its power lay precisely in that appeal to rationality which Mach wished to eliminate from the foundations of science. No wonder therefore that he advanced it on false grounds, attacking Newton for making an empty statement and overlooking the fact that—far from being empty— the statement was false. Thus Mach prefigured the great theoretic vision of Einstein, sensing its inherent rationality, even while trying to exorcise the very capacity of the human mind by which he gained this insight.

But there yet remains an almost ludicrous part of the story to be told. The Michelson-Morley experiment of 1887, which Einstein mentions in support of his theory and which the textbooks have since falsely enshrined as the crucial evidence which compelled him to formulate it, actually did not give the result required by relativity! It admittedly substantiated its authors’ claim that the relative motion of the earth and the ‘ether’ did not exceed a quarter of the earth’s orbital velocity. But the actually observed effect was not negligible; or has, at any rate, not been proved negligible up to this day. The presence of a positive effect in the observations of Michelson and Morley was pointed out first by W.M.Hicks in 1902 and was later evaluated by D.C.Miller as corresponding to an ‘ether-drift’ of eight to nine kilometres per second. Moreover, an effect of the same magnitude was reproduced by D.C.Miller and his collaborators in a long series of experiments extending from 1902 to 1926, in which they repeated the Michelson-Morley experiment with new, more accurate apparatus, many thousands of times.

The layman, taught to revere scientists for their absolute respect for the observed facts, and for the judiciously detached and purely provisional manner in which they hold scientific theories (always ready to abandon a theory at the sight of any contradictory evidence), might well have thought that, at Miller’s announcement of this overwhelming evidence of a ‘positive effect’ in his presidential address to the American Physical Society on December 29th, 1925, his audience would have instantly abandoned the theory of relativity. Or, at the very least, that scientists— wont to look down from the pinnacle of their intellectual humility upon the rest of dogmatic mankind—might suspend judgment in this matter until Miller’s results could be accounted for without impairing the theory of relativity. But no: by that time they had so well closed their minds to any suggestion which threatened the new rationality achieved by Einstein’s world-picture, that it was almost impossible for them to think again in different terms. Little attention was paid to the experiments, the evidence being set aside in the hope that it would one day turn out to be wrong.

The experience of D.C.Miller demonstrates quite plainly the hollowness of the assertion that science is simply based on experiments which anybody can repeat at will. It shows that any critical verification of a scientific statement requires the same powers for recognizing rationality in nature as does the process of scientific discovery, even though it exercises these at a lower level. When philosophers analyse the verification of scientific laws, they invariably choose as specimens such laws as are not in doubt, and thus inevitably overlook the intervention of these powers. They are describing the practical demonstration of scientific law, and not its critical verification. As a result we are given an account of the scientific method which, having left out the process of discovery on the grounds that it follows no definite method overlooks the process of verification as well, by referring only to examples where no real verification takes place.

At the time that Miller announced his results, relativity had yet made few predictions that could be confirmed by experiment. Its empirical support lay mainly in a number of already known observations. The account which the new theory gave of these known phenomena was considered rational, since it derived them from one single convincingly rational principle. It was the same as when Newton’s comprehensive account of Kepler’s Three Laws, of the moon’s period and of terrestrial gravitation—in terms of a general theory of universal gravitation—was immediately given a position of surpassing authority, even before any predictions had been deduced from it. It was this inherent rational excellence of relativity which moved Max Born, despite the strong empirical emphasis of his accounts of science, to salute as early as 1920 ‘the grandeur, the boldness, and the directness of the thought’ of relativity, which made the world-picture of science ‘more beautiful and grander’.

Since then, the passing years have brought wide and precise confirmation of at least one formula of relativity; probably the only formula ever sent sprawling across the cover of Time magazine. The reduction of mass (m) by the loss of energy (e) accompanying nuclear transformation has been repeatedly shown to confirm the relation e=mc2, where c is the velocity of light. But such verifications of relativity are but confirmations of the original judgment of Einstein and his followers, who committed themselves to the theory long before these verifications. And they are an even more remarkable justification of the earlier strivings of Ernst Mach for a more rational foundation of mechanics, setting out a programme for relativity at a time when no avenues could yet be seen towards this objective.

The beauty and power inherent in the rationality of contemporary physics is, as I have said, of a novel kind. When classical physics superseded the Pythagorean tradition, mathematical theory was reduced to a mere instrument for computing the mechanical motions which were supposed to underlie all natural phenomena. Geometry also stood outside nature, claiming to offer an a priori analysis of Euclidean space, which was regarded as the scene of all natural phenomena but not thought to be involved in them. Relativity, and subsequently quantum mechanics and modern physics generally, have moved back towards a mathematical conception of reality. Essential features of the theory of relativity were anticipated as mathematical problems by Riemann in his development of non-Euclidean geometry; while its further elaboration relied on the powers of the hitherto purely speculative tensor calculus, which by a fortunate accident Einstein got to know from a mathematician in Zürich. Similarly, Max Born happened to find the matrix calculus ready to hand for the development of Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics, which could otherwise never have reached concrete conclusions. These examples could be multiplied. By them, modern physics has demonstrated the power of the human mind to discover and exhibit a rationality which governs nature, before ever approaching the field of experience in which previously discovered mathematical harmonies were to be revealed as empirical facts.

Thus relativity has restored, up to a point, the blend of geometry and physics which Pythagorean thought had first naïvely taken for granted. We now realize that Euclidean geometry, which until the advent of general relativity was taken to represent experience correctly, referred only to comparatively superficial aspects of physical reality. It gave an idealization of the metric relations of rigid bodies and elaborated these exhaustively, while ignoring entirely the masses of the bodies and the forces acting on them. The opportunity to expand geometry so as to include the laws of dynamics was offered by its generalization into many- dimensional and non-Euclidean space, and this was accomplished by work in pure mathematics, before any empirical investigation of these results could even be imagined. Minkowski took the first step in 1908 by presenting a geometry which expressed the special theory of relativity, and which included classical dynamics as a limiting case. The laws of physical dynamics now appeared as geometrical theorems of a four- dimensional non-Euclidean space. Subsequent investigation by Einstein led, by a further generalization of this type of geometry, to the general theory of relativity, its postulates being so chosen as to produce invariant expressions with regard to all frames of reference assumed to be physically equivalent. As a result of these postulates, the trajectories of masses follow geodetics, and light is propagated along zero lines. When the laws of physics thus appear as particular instances of geometrical theorems, we may infer that the confidence placed in physical theory owes much to its possessing the same kind of excellence from which pure geometry and pure mathematics in general derive their interest, and for the sake of which they are cultivated.

From Personal Knowledge, 1958.