Branko on how history didn’t end in Eastern Europe

I recall while doing some research on three Austro-Hungarians — Friedrich Hayek, Michael Polanyi and Karl Popper — how disastrous each of them thought the formula Woodrow Wilson took to Versailles — self-determination. Of course Wilson didn’t mean self-determination for blacks in Dixieland but no matter. It was a formula that blew up the four Central and Eastern European empires and some omelettes were made with some egg breaking issues arising along the way.

Anyway, here’s Branko Milanovic on Eastern European nationalism as a perpetual motion machine for violence and instability.

Eastern Europe was the terrain of imperial competition. The empires often successfully absorbed domestic elites, but with increasing literacy, urbanization and greater share of intellectuals in local populations, the elites turned to defining the “nation”. This was part of the pan-European Romantic movement. The intellectual elites began by studying local customs, poetry, folk dancing, then turned toward codification and standardization of languages, and moved to the claims for national self-determination. Depending on the empire they were part of, the elite’s nationalism was anti-Russian, anti-Ottoman, anti-Austrian and anti-German. In some cases (like Poland) it was simultaneously directed against all three. Nationalism underwrote all the 19th century rebellions: Serbian, Greek, and later Bulgarian and Albanian against the Ottomans, Polish against the Russian Empire, Croatian against Hungarians, Hungarian against Austrians.

After the Versailles Peace Treaty, it seemed that the elites’ goals were fulfilled: four imperial powers disintegrated. But it was an illusionary success for nationalist elites whose objective always was to include 100% of its nationality (which itself might have been broadly defined) within its borders even if meant including other peoples who, in their turn, wanted to include 100% of its nationality within its own borders. Thus the end of empires was succeeded by inter-national conflicts in countries that were composed of several nationalities (the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia) or contained significant minorities (Poland and Romania); or were left with the feeling of national deprivation precisely because they included within its borders much less than 100% of its nationality (Hungary).

Such elites were ideologically very close to fascism and it is not strange that the support that the Nazis enjoyed in Eastern Europe was significant, and the places where they did not enjoy support were the countries where the Nazis planned to destroy local elites. Hence, the elites had to turn against them.

In all cases, nationalist elites looked for Western support. At times, it was forthcoming as when the principal western powers (UK and France) had an interest in dismembering the empires (from 1916 onward with respect to Austria-Hungary), or when they tried to contain them for ideological reasons (as with the Soviet Union), or for purely military reasons (France with respect to Germany between the two world wars). In other cases, the support was not forthcoming and the countries were trafficked by the great powers in Versailles and Yalta. But that did not stop the elites in their self-understanding to believe they were the defenders of the “Western civilization”. Depending on conditions, they defended (or “defended”) it, against communism, Russia’s Asianism, Turkic Ottomans, or against whoever the nationalist intelligentsia thought was less culturally advanced than themselves and their own nation.

The communist rule that to many countries came with the Soviet Army, made nationalism go underground. Its expressions were no longer tolerated. But it continued to exist, and as communist grip loosened and its economic failure become more obvious, the underground “waters” of nationalism grew into a torrent. That torrent blew everything in front of itself in the revolutions of 1989-90. The revolutions were self-servingly interpreted by the participants and Western elites as the revolution of liberalism. In reality, they were revolutions of nationalism and self-determination directed against an imperial power, the Soviet Union (identified with Russia). Since the 1989-90 revolutions suddenly commanded widespread popular support, it was easy to proclaim them as revolutions of democracy rather than of nationalism. That was particularly easy in countries without ethnic minorities or “others”. But where it was not the case, it led to violent conflict: in the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Its current, and bloodiest, chapter is now being written in the war between the two most important successor states of the USSR: the conflict that was feared already at the time of the Belovezha Accords, but was hoped to be somehow avoided.

East European nationalisms always define themselves as “emancipatory” and “liberal” when dealing with stronger powers, while, once themselves in power, in regard to those who are weaker or less numerous, they behave imperially, reproducing the very same traits of which they are critical in others. …

This particular pattern of elite thinking opens a possibly unsolvable problem for the Russian intellectual elite. It shares, thanks to its anti-communism, and despite its imperial background, many of the features of East European elites. But since the latter are anti-Russian, the two cannot coexist in harmony. The Russian pro-Western elite finds itself in no-man’s land. It cannot find any sympathy among East European elites, nor can it find any sympathy among the Western elites because the latter are supporting Eastern Europe.…

The Russian elite thus finds itself intellectually (and in terms of sympathy) isolated. They can proffer banal points of liberalism but nobody believes them. Or they can, as many seem to be doing, turn back to imperialism and invent a fiction of Euro-Asianism that gives them a special place in the world in which they do not need the approval of Western and East European elites. In either case, the outcome is dire.

Meanwhile elsewhere in Eastern Europe

And further east: The Caliphate as a Jewish haven

The Ottoman dynasty is the protector of Turkey’s Jews. When our ancestors were expelled from Spain, when they looked for a country who could shelter them, they [Ottomans] saved them from destruction. Under the shade of their state, [Jews] found safety of life, honor and property, the freedom of religion and language. It is our conscientious duty to help them in their dark days, as much as we can.

The Jewish train station manager from which the last caliph embarked in 1924.

I’m too ignorant to recommend this interpretation, but not too ignorant to be intrigued by it.

Few seem to have noticed, but this year, 2024, is the centennial of a pivotal event that deeply impacted the course of the modern Middle East, if not the world: the abolition of the Caliphate, or the “successorship” to the Prophet Muhammad, which led the worldwide Muslim community politically since the birth of Islam in the early seventh century.

The Caliphate had its ups and downs, and was at times more symbolic than effective, but it had meaningfully survived into the twentieth century under the banner of its last seat, the Ottoman Empire. But the latter collapsed in the aftermath of World War I, allowing one of its generals, the staunchly secular Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), to abolish the Ottoman monarchy in 1922 and proclaim the Republic of Turkey a year later. …

Initially, Kemal did not touch the Caliphate. While his republic commenced in the new capital, Ankara, the old Caliphate, now held by the last Ottoman crown prince Abdulmejid II, continued in Istanbul as a non-political but still prestigious institution. If things continued like that, it could have turned into an entity like the Vatican State, preserving a moral authority not just in Turkey but also in the broader Sunni world. Yet Kemal had little patience for any authority other than his own. About sixteen months after the abolition of the monarchy, he also abolished the Caliphate on March 3, 1924. …

Was the abolition of the caliphate a good decision? Secularist Turks who adore Atatürk, along with many secularists or nationalists around the Muslim Middle East, would say of course. Many Westerners, who may associate the Caliphate with the various extremist manifestations of Islam today—perhaps even the notorious terror army, ISIS, which proclaimed a monstrous “caliphate” of its own—may readily agree.

However, there is a counter-argument made by scholars including Boston College professor Jonathan Laurence that is worth considering: The abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate, which represented a tolerant and modernizing Islam, left a vacuum that was filled by secular autocrats and reactionary Islamists whose vicious cycle of conflict explains much of the tragedy of the modern Middle East. If the Caliphate continued, as a sane religious authority to restrain extremism, the course of the Muslim world could be better for all, including non-Muslim minorities, which have suffered terribly in the past hundred years.

The Ottoman Caliphate’s much-forgotten friendship with the Jews may provide the best case study for why that argument makes sense.

A Judeo-Islamic Tradition

The story of that friendship is quite fascinating …. Friendship between Muslims and Jews actually goes back to the very genesis of Islam, which was born in 610 CE in the city of Mecca as a new proclamation of Abrahamic monotheism to polytheist Arabs. The Qur’an, as preached by the Prophet Muhammad, retold many stories of the Bible and showed great respect to all its prophets. First and foremost among them was Moses, whose stories dominate the Qur’an, and who appears as a role model for Muhammad himself.

That is also why Islam, as it quickly turned into a world empire, vowed to destroy idolatry, but tolerated Jews and Christians as fellow monotheists with divine revelation—“The People of the Book.” The legal status offered to them (dhimma, or “protection”), was far short of equal citizenship that we enjoy in the modern liberal world, but Jews found it quite tolerant for its time, especially in comparison to medieval Christendom, where anti-Judaism was rampant and religious persecution was recurrent.

That is why, for centuries, Jews often preferred living under Muslim rule. They even had remarkable moments of flourishing in the Middle East, North Africa, and especially Muslim Spain, as acknowledged by many Jewish historians. Among them was the late Eli Barnavi who wrote about the “golden age of the Jewish communities in Muslims lands,” marking “a period of brilliant economic prosperity and cultural creativity.” Another historian, Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, defined “the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry,” under Muslim rule, as the “closest parallel in Jewish history to the contemporary golden age of American-Jewish life.”

“The Best Place in the World for Jews to Live”

The latest of these Jewish golden ages under Islam was in the Ottoman Empire, which emerged at the dawn of the fourteenth century as a small Turkish principality in Western Anatolia, only to expand constantly towards East and West, the latter including Byzantium, the remnant of Rome. A little-known fact is that Ottoman conquests over Byzantium, which had harsh laws against Jews, were seen by the latter as a blessing. Indeed, only after the Ottoman conquest of Bursa in 1326, were Jews allowed to build a synagogue, engage in business, or purchase houses and land.

Good news of Ottoman tolerance soon reached Europe. Hence Ashkenazi communities expelled from Hungary in 1376, from France in 1394, and from Sicily, Bavaria, and Venetian-ruled Salonika, migrated to Ottoman lands. In 1453, the Ottomans finally conquered the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, one of the greatest cities on earth, which became their new capital. The city attracted even more Jewish immigrants from Europe, because “after 1453, Istanbul was unquestionably the best place in the world for Jews to live,” in the words of Yale historian Alan Mikhail. “Nowhere were Jews as prosperous and free.”

It’s not your data. SHOCK!!

Crikey! reports that AI is being trained on data of people who never consented. Should we be surprised? Should we be concerned?

I-MED and harrison.ai have gone to ground as politicians and advocates slam the companies over Crikey’s revelation that the companies are training artificial intelligence on patients’ private medical scans without their knowledge.

Yesterday, a Crikey investigation exposed how Australia’s biggest medical imaging provider had given a buzzy healthcare technology startup backed by industry heavy hitters access to potentially hundreds of thousands of Australians’ chest X-rays, raising concerns from privacy experts.

This data was used to train an AI tool that has propelled harrison.ai into becoming a darling of Australia’s startup scene with a valuation in the hundreds of millions of dollars, and helped modernise I-MED’s business.

Neither company responded to repeated requests for comment from Crikey about the legal basis for using and disclosing this personal information.

I think it’s unfortunate that we are falling into a kind of left-right culture war on this stuff and becoming proprietarian over data — a non-rival good. Fiona Stanley lowered the incidence of spina bifida among the indigenous people of WA using data without anyone’s consent.

I tried to sketch some of the principles we should be trying to develop here and then offered a commentary on a more recent case study in this piece. But no-one took much notice.

HT: George, a subscriber.

Freakonomics heal thyself

It’s a fair cop.

There was this Freakonomics podcast, “Why Is There So Much Fraud in Academia?” Several people emailed me about it, pointing out the irony that the Freakonomics franchise, which has promoted academic work of such varying quality (some excellent, some dubious, some that’s out-and-out horrible), had a feature on this topic without mentioning all the times that they’ve themselves fallen for bad science.

As Sean Manning puts it, “That sounds like an episode of the Suburban Housecat Podcast called ‘Why are bird populations declining?'”

And Nick Brown writes:

Consider the first study on the first page of the first chapter of the first Freakonomics book (Gneezy & Rustichini, 2000, “A Fine is a Price”, 10.1086/468061), in which, when daycare centres in Israel started “fining” parents for arriving late to pick up their children, the amount of lateness actually went up. I have difficulty in believing that this study took place exactly as described; for example, the number of children in each centre appears to remain exactly the same throughout the 20 weeks of the study, with no mention of any new arrivals, dropouts, or days off due to illness or any other reason. Since noticing this, I have discovered that an Israeli economist named Ariel Rubinstein had similar concerns (https://arielrubinstein.tau.ac.il/papers/76.pdf. pp. 249–251). He contacted the authors, who promised to put him in touch with the staff of the daycare centres, but then sadly lost the list of their names. The paper has over 3,200 citations on Google Scholar.

I replied: Indeed, the Freakonomics team has never backed down on many ridiculous causes they have promoted, including the innumerate claim that beautiful parents are 36% more likely to have girls and some climate change denial. But I’m not criticizing the researchers who participated in this latest Freakonomics show; we have to work with the news media we have, flawed as they are.

And, as I’ve said many times before, Freakonomics has so much good stuff. That’s why I’m disappointed, first when they lower their standards and second when they don’t acknowledge or wrestle with their past mistakes. It’s not too late! They could still do a few shows—or even write a book!—on various erroneous claims they’ve promoted over the years. It would be interesting, it would fit their brand, it could be educational and also lots of fun.

This is similar to something that occurs in the behavioral economics literature: there’s so much research on how people make mistakes, how we’re wired to get the wrong answer, etc., but then not so much about the systematic errors made in the behavioral economics literature itself. As they’d say in Freakonomics, behavior can be driven by incentives.

Oops: Nobel prize-winner tallies two more retractions, bringing total to 13

A Nobel prize-winning genetics researcher has retracted two more papers, bringing his total to 13.

Gregg Semenza, a professor of genetic medicine and director of the vascular program at Johns Hopkins’ Institute for Cell Engineering in Baltimore, shared the 2019 Nobel prize in physiology or medicine for “discoveries of how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.”

Climate Capitalists

Niels Joachim Gormsen, Kilian Huber, and Sangmin Simon Oh #32933Firms' perceived cost of green capital has decreased since the rise of sustainable investing. Green and brown firms perceived their cost of capital to be the same before 2016, but after the post-2016 surge in sustainable investing, green firms perceived their cost of capital to be on average 1 percentage point lower. This difference has widened as sustainable investing has intensified. Within some of the largest energy and utility firms, managers have started applying a lower cost of capital to greener divisions. The changes in the perceived cost of green capital incentivize cross-firm and within-firm reallocation of capital toward greener investments.

Sent by a subscriber

Skidelsky on Budget Black Holes

Is growing its way out of trouble still available to the new UK Government.

[M]uch of the political debate has focused on the size of the UK’s fiscal hole. Is it really £22 billion, or is it larger? How much of it was inherited debt, and how much was the result of the new government’s pay increases for public-sector workers? …

The current fiscal framework is partly a reaction to the discretionary budget practices of the 1950s and the 1960s. During that period, governments prioritized maintaining non-inflationary full employment over balancing the budget. Deficits were used to reduce unemployment, while surpluses were seen as tools to control inflation. The main flaw of this approach was that stimulating growth through higher spending and tax cuts proved far easier than reducing inflation through spending cuts and higher taxes. Consequently, inflationary pressure was built into the full-employment commitment.

In response, British governments shifted their focus to ensuring price stability, making it their primary macroeconomic objective. John Maynard Keynes’s insight that even an efficient market economy cannot sustain full employment was largely dismissed. As the pendulum swung from one extreme to the other, finding a middle ground became increasingly difficult.

Nowadays, the case for increased public investment is made exclusively in supply-side terms. … While clean energy offers much higher returns than fossil fuels, the thinking goes, markets alone cannot deliver the necessary investments to combat climate change, making “smart” public spending critical. As a recent Evening Standard editorial put it, a “truly radical new government” would “break with convention” and invest in “infrastructure projects that help lay the foundations of a vibrant economy.” …

The UK’s fiscal straitjacket cannot be loosened without demand-side measures. Although arguing for increased public investment may seem counterintuitive with unemployment near 4%, its lowest level since the 1970s, the headline unemployment rate fails to capture the economy’s actual capacity utilization. The inactivity rate – the proportion of people aged 16-64 who are neither working nor seeking employment – stands at 21.8%. With roughly 25% of the workforce employed part-time – and many unable to find full-time positions – and 6% of the working-age population on disability benefits, the true level of underutilized potential could be two or even three times higher than official unemployment figures suggest.

Last year, I argued that US President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) contained the germ of an important fiscal concept: the balanced budget multiplier. According to this principle, an increase in government spending accompanied by an equal increase in taxation will boost aggregate demand, as some of the money taken by the tax would have been saved rather than spent.

The IRA, which includes $369 billion in clean-energy subsidies and tax breaks, also aims to balance the budget over ten years by generating an extra $739 billion in revenues from higher economic growth and corporate taxes. So far, the results seem to support this strategy: since 2021, the US economy has grown steadily, with unemployment dropping to a 50-year low of 3.4% in 2023 (before rising to 4.2% in 2024) and inflation falling to 2.5%. In the UK, Reeves considered a similar approach, but with major tax increases off the table, she faces the same fiscal constraints as her Tory predecessor, Jeremy Hunt.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this. The first is a straightforward Keynesian insight: to reduce national debt, government policies must focus on ensuring that GDP grows faster than the debt, not on cutting spending. A key lesson from 14 years of Conservative rule is that when fiscal austerity brings the economy to a halt, public debt as a share of GDP invariably increases.

Second, British governments lack their American counterparts’ freedom to disregard financial sentiment, however misguided, and cannot raise taxes at will. The exchange controls that once prevented capital flight are long gone, and the UK no longer has the imperial power to force money to stay ashore.

That said, with adequate preparation, a British government should be able to issue “net-zero bonds,” similar to the war bonds used to fund World War I and World War II, to finance its clean-energy transition. This fiscal initiative could meet both supply-side needs and demand-side imperatives.

Art competition winner

I was driving through Richmond the other day and saw an art competition exhibiting in an ex-church, so I wandered in. It was the Contemporary Art Society of Victoria and the lady inside told me that Nolan, Tucker and others had exhibited with it. And this is the picture that won — chosen by loved Melbourne Mosaicist Deborah Halpern. You can still pick it up this weekend for $420!

Or this for $350

Rick Morton on Robodebt

Excellent step by step walking through the shocking Robodebt debacle. It also makes clear that Renée Leon protested a little too much from her next gig as a university Vice Chancellor. She argues she did the right thing and got sacked for her trouble. She may well have done so, but that was after quite a few months where she was an active part of the cover up. Anyway, she had current board members vouching for her, so things should work out for her.

Brad goes Sherlock Holmes on Trump appointed Fed Governor

She became a hawk on Biden’s watch — a little like Republican congressfolk’s fiscal hawkishness (while Democrats are in office that is.)

Liberalism is losing the information war

Here’s Noah Smith observing how badly the US’s reflexive liberalism disadvantages it in information warfare. It put me in mind of a time during the cold war when upper middle class culture was taken seriously with both the Russians and Americans pumping money into supporting high culture. That was for its propaganda value and just because back in the day, upper middle class elites who run the show respected high culture. In the West that involved covert US funding of the Congress for Cultural Freedom and in Australia Quadrant Magazine.

Anyway, things are different now. Psyops get down to troll farms.

The U.S. is starting to realize that we’re losing the information war (badly)

Last year I wrote one of the scarier posts I’ve ever written, about how liberalism is losing to totalitarianism in the global information war:

My thesis is that liberalism is losing because, in effect, it has refused to fight — liberal countries decided that our own governments were omnipotent leviathans who must be forever kept away from the arena of speech, while foreign governments are simply one more kind of atomistic “private” actor whose rights are never to be infringed. If the government of China controls our information diet, we decided, that is freedom, while if the government of America dares to push back, that is oppression.

I think we’re now just starting to realize how badly this idea has cost us. The U.S. Justice Department has just indicted a group called Tenet Media — which sponsors a bunch of big-time right-wing podcasters on YouTube — for “covertly funding and directing” the Americans who worked for it, publishing videos “in furtherance of Russian interests”.

The podcasters in question include Tim Pool, Dave Rubin, Benny Johnson, and Lauren Southern — all prominent pro-Trump right-wing firebrands. Rubin and Pool apparently made the most money from Tenet.

Only time will tell how much each media figure knew that Russia was trying to manipulate them (unless Trump gets elected and kills the investigation, of course). And we don’t know how effective Tenet was in getting right-wingers to say pro-Russia things, or how effective those messages were in swaying American public opinion.

But what this case does show is that foreign governments’ attempts to manipulate Americans’ opinions are far more extensive than most people realize, and that our government’s process for finding and countering them is very slow and cumbersome. Yes, we fought back this time —belatedly. But it took us a very long time to do so, and even this one effort may eventually get canceled. The many long years in which we accepted foreign government propaganda as “private” speech have probably made us hesitate either to investigate it when it does break the law, or to even believe that it might be worth investigating.

In fact, we’ve probably just scratched the tip of the iceberg. The FBI recently reported that the Russians have 600 “active influencers” in America, but has not released the list. The Tenet indictment names only two such influencers. Meanwhile, a former aide to New York governor Kathy Hochul was just arrested for being a Chinese spy. Given that she was just about the most blatant and obvious spy ever, it’s fair to say she’s probably far from the only one working in American politics.

What do the totalitarians want Americans to think? Most of Russia’s efforts seem to be supporting Trump and opposing Democrats. That’s unsurprising, given that Trump is far more pro-Russian than Harris, and probably plans to force Ukraine into ceding territory to Russia (or worse). But more fundamentally, the goal of the totalitarians seems to be to sow chaos and division in American society. The weaker America is internally, the less it will be able to oppose China and Russia on the international stage.

Fortunately, I think cases like Tenet Media are causing Americans to — very slowly — wake up and realize that the information war is a war, and that they are losing that war. Jeremiah Johnson has an excellent post explaining why we should all be more worried about foreign governments’ attempts to control our media:

And the Foundation for Defense of Democracies just released an excellent report entitled “Cognitive Combat”, where they make arguments similar to those I’ve made, but in much greater detail.

My main worry at this point is that the election of Trump this fall will plunge America back into another four years of bitter social strife, distracting and delaying us from even being able to start fighting back in the information war.

JD Vance explains himself

And gets fitted up for saying that he’s made up the dog eating stories. Which is not what he’s saying. Anyway, no matter. Those who live by the sword die by the sword — or here’s hoping. Right now we have an psycho with a good chance of becoming president again, people who’ve warned against him rearranging themselves to catch a ride on his coattails and the more normal presidential candidate — the one with a greater apparent grip on reality — not giving interviews and, it seems barely able to survive them. I’m rooting for her. Strange times.

A fine way to finish a presidency

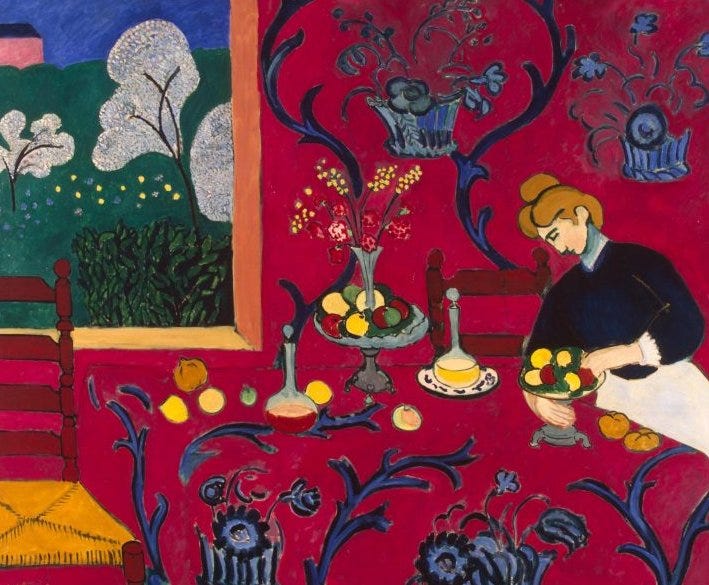

Commissioning Matisse

Sergei Shchukin was a Russian businessman. He was also a patron and art collector. Henri Matisse was one of his favorite artists. When Shchukin decided to commission artwork for his Moscow home, he chose Matisse. He requested an exterior painting in blue tones, aiming for a serene and elegant atmosphere. Matisse accepted the commission. Shchukin was not used to being disobeyed. True to his style, Matisse finally decided to do the opposite. He painted an interior. It was a vibrant red, full of passion and rebellion. Matisse wasn't sure of the Russian magnate's reaction. Would he consider it an insult? What reprisals would he take? But Shchukin was a visionary. He loved the painting and told Matisse a phrase that predicted what would eventually happen: "The public is against you, Henri, but the future is yours." The color was not just an element but the absolute protagonist. It challenges perspective. A revolutionary painting at its time. And for many, it is one of Matisse's greatest works. This anecdote illustrates the relationship between a visionary patron and a bold artist. Shchukin was investing not in a painting but in the history of art.

The Dessert: Harmony in Red (aka The Red Room). From this tweet.

Great interview, about what seems like a great book

Life advice from a comedian

Comedians have more smarts (and courage) than your average bear

And lots more magnificent paintings of sunsets.

Heaviosity half hour

Hannah Arendt and eudaimonia

I’m not too sure I understand this too well, or agree with what I do understand. But there you go. This substack is pretty promiscuous with anything interesting.

The ancient saying that nobody can be called eudaimōn before he is dead may point to the issue at stake, if we could hear its original meaning after two and a half thousand years of hackneyed repetition; not even its Latin translation, proverbial and trite already in Rome—nemo ante mortem beatus esse dici potest—conveys this meaning, although it may have inspired the practice of the Catholic Church to beatify her saints only after they have long been safely dead. For eudaimonia means neither happiness nor beatitude; it cannot be translated and perhaps cannot even be explained. It has the connotation of blessedness, but without any religious overtones, and it means literally something like the well-being of the daimōn who accompanies each man throughout life, who is his distinct identity, but appears and is visible only to others. Unlike happiness, therefore, which is a passing mood, and unlike good fortune, which one may have at certain periods of life and lack in others, eudaimonia, like life itself, is a lasting state of being which is neither subject to change nor capable of effecting change. To be eudaimōn and to have been eudaimōn, according to Aristotle, are the same, just as to “live well” (eu dzēn) and to have “lived well” are the same as long as life lasts; they are not states or activities which change a person’s quality, such as learning and having learned, which indicate two altogether different attributes of the same person at different moments.

This unchangeable identity of the person, though disclosing itself intangibly in act and speech, becomes tangible only in the story of the actor’s and speaker’s life; but as such it can be known, that is, grasped as a palpable entity only after it has come to its end. In other words, human essence—not human nature in general (which does not exist) nor the sum total of qualities and shortcomings in the individual, but the essence of who somebody is—can come into being only when life departs, leaving behind nothing but a story. Therefore whoever consciously aims at being “essential,” at leaving behind a story and an identity which will win “immortal fame,” must not only risk his life but expressly choose, as Achilles did, a short life and premature death. Only a man who does not survive his one supreme act remains the indisputable master of his identity and possible greatness, because he withdraws into death from the possible consequences and continuation of what he began. What gives the story of Achilles its paradigmatic significance is that it shows in a nutshell that eudaimonia can be bought only at the price of life and that one can make sure of it only by foregoing the continuity of living in which we disclose ourselves piecemeal, by summing up all of one’s life in a single deed, so that the story of the act comes to its end together with life itself. Even Achilles, it is true, remains dependent upon the storyteller, poet, or historian, without whom everything he did remains futile; but he is the only “hero,” and therefore the hero par excellence, who delivers into the narrator’s hands the full significance of his deed, so that it is as though he had not merely enacted the story of his life but at the same time also “made” it.

Hannah Arendt on Natality

I don’t think this is a great essay it’s by Karin Fry. Apart from anything else, it uses way to many fancy words — like “Heidegger” (39 times) and “ontology” (5 times). It even uses them together twice!!

But I sure do agree with the money quote from Hannah — contra Heidegger.

Men, although they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin.

And so, on with the show:

From very early on in her intellectual career, Hannah Arendt’s interest in life and the political implications connected to the fact of being born is significant. The concept of “natality” is central to her overall theory of politics, and perhaps, its most optimistic aspect. Focusing on life and natality, as opposed to death and mortality, raises the political life into a hopeful activity in which one truly displays aspects of the self to the world in meaningful ways. Focusing on natality suggests that individual action is important and earthly events are significant. Connected to her concepts of political action and plurality, natality is at the heart of Arendt’s theory of politics.

Natality and Augustine

Having attended Martin Heidegger’s lectures during the period in which he was writing Being and Time, Arendt’s first significant break from his point of view occurs in her doctoral dissertation, published in 1929 as Der Liebesbegrif bei Augustin: Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation. This work has been translated into English as Love and Saint Augustine (published in 1996), and includes later revisions Arendt made to her thesis as she anticipated its English publication during 1964–5. Because of her failure to finish the revision, there is controversy concerning the overall significance of her investigation of Augustine.1 Nonetheless, her revisions to the English translation include the term “natality” and indicate that her examination of Augustine’s work may have inspired the formation of this concept. Ultimately, Arendt explains natality more thoroughly in her later work, especially in The Human Condition. Nonetheless, Arendt’s thesis and its revision provide interesting clues to the overall significance of natality to the rest of her theory.

Martin Heidegger’s fundamental ontology looms large over her dissertation, although her thesis supervisor Karl Jaspers’s Existenz philosophy also has an influence. Arendt’s analysis of Saint Augustine’s theory is a phenomenological exploration of the concept of love in much the same vein as Heidegger’s exploration of time. Nevertheless, there are two aspects in particular that break with Heidegger’s work. Throughout her career, Arendt’s major criticism of Heidegger involves his lack of attention to the active life of politics, in favour of the contemplative life of eternal truths. Although this criticism is expressed more directly in her later work, it emerges in her discussion of Augustine’s concept of love and is explored in two different ways in this text. First, there is an analysis of natality, or what it means to be born, as opposed to Heidegger’s emphasis on mortality. Second, Arendt develops a critical analysis of Augustine’s discussion of love of the neighbour from the Christian worldview. This criticism extends to Heidegger’s work as well, since Heidegger fails to give much attention to positive relations with others in Being and Time. Focusing on the solitude of death, as opposed to the potential of birth, may result in a more solitary and less politically oriented philosophy.

Heidegger’s Being and Time ([1927] 1967) is known for exploring the authentic life of the individual in the mode of being-towards-death. The authentic person faces up to his mortality and does not pretend life is endless. Only through acknowledging that life is limited will one be filled with the urgency to make authentic decisions about one’s present life. Often, Heidegger writes about this as a seemingly solitary and individual task, since mortality is uniquely one’s own. In ordinary experience, other people distract us and encourage us to be inauthentic, as they are caught up in everyday concerns that refute the idea that death is an ever-present possibility. Heidegger calls other people in the inauthentic mode of engagement with the self das Man, sometimes translated as “the they”. Engaging with the inauthentic “they” leads one away from facing mortality and towards getting caught up in the idle chatter of everyday concerns. Even though Heidegger mentions the possibility of authentically being-with-others, what he calls Mitsein, its discussion is not as emphasized as the seemingly more usual problematic relation with other people that produces inauthentic behaviour based in either distraction or outright denial of the limited time that one has on earth.2 By examining different forms of love in Augustine’s work, Arendt finds problems that may easily extend to Heidegger’s ontology. Arendt rejects the solitary “authentic” existence that seems to be the outcome of both Heidegger and Augustine’s work.

According to Arendt, Augustine describes love as involving appetitus, or craving, which concerns desiring an object thought to bring happiness (Arendt 1996: 9). However, craving is not unrelated to fear, since all goods can be lost. Arendt notes appetitus in Augustine’s work is often related to mortality, since mortality can be understood as an enemy to be feared, connected to loss. Typically, mortality is beyond personal control, and humans crave the ability to face the future without fear or loss of life (ibid.: 11–12). As Arendt’s biographer Elizabeth Young-Bruehl notes, the ultimate goal of craving is a “life without fear” (Young-Bruehl 2004: 491). Yet, to truly satisfy the craving, the right kind of love is required. Through loving God, the fear of mortality is superseded by a love that produces eternal life, which is crucial for the Catholic saint. The wrong sort of love, cupiditas, is love for things of this world and in Augustine’s framework it is exemplified by those who belong to the city of man, doomed to not be saved. Arendt describes cupiditas in Heideggerian terminology as a flight from death. Those who crave for permanence cling “to the very things sure to be lost in death” (Arendt 1996: 17). This produces unsatisfying enslavement to things outside of one’s control that can be lost against one’s will (ibid.: 20). Fear of death does not end with cupiditas because one is still tied to temporal things that can be lost (ibid.: 23). Arendt describes this phenomenon as a type of “flight from the self” and parallels it to Heidegger’s description of inauthentic life (ibid.). Through cupiditas, one is distracted from fear of mortality, but the self gets lost in earthly things and the anxiety about death is not resolved (ibid.: 23–5).

Augustine’s cure for this state differs from Heidegger’s, largely due to Augustine’s overtly Christian concerns. Caritas is the right kind of love that pursues eternity (ibid.: 17). The correct kind of love, caritas, finds eternity through rejecting the objects of the temporal world and closes the gap between the individual and God (ibid.: 20). Through caritas, God, or the beloved “becomes a permanently inherent element of one’s own being” (ibid.: 19). The true happiness of the eternal life of the soul emerges through this love, by transcending human, mortal nature (ibid.: 30). Unlike for Heidegger, being and time are opposed for Augustine. Arendt states that in Augustine’s work, to truly be “man has to overcome his human existence, which is temporality” (ibid.: 29). In effect, “Death has died” (ibid.: 34). Humans are essentially liberated from mortality because of an eternal afterlife. The love of life on this earth is a sinful temptation, or at best, secondary and derivative, as compared to the rewards of caritas.

In order to explain how temporality works in Augustine’s thought, Arendt turns to natality. Heidegger emphasizes the future eventuality of death, but for Augustine, it is the past that is more crucial for influencing the present and the future (ibid.: 47). In her revision to the dissertation for its English translation, Arendt changes her discussion of the importance of the past for Augustine to include the word “natality”. By this time, she has already elaborated upon natality in The Human Condition and other works. She includes the following statement in her revision of her thesis: “the decisive fact determining man as conscious, remembering being is birth or ‘natality,’ that is, the fact that we have entered the world through birth” (ibid.: 51). In her original dissertation, Arendt discusses only the phenomena of “beginning” and “origin” but adds the word “natality”, which signifies that some of the inspiration for this idea can be found with Augustine (Scott & Stark 1996: 132–3). In fact, Arendt usually quotes Augustine whenever she discusses natality or birth. In relation to Heidegger, mortality is still important for Arendt, but not as emphasized because natality and the potential that humans have for living has greater significance for political action. Jeffrey Andrew Barash argues that the difference in temporal emphasis between Arendt’s examination of Augustine and Heidegger’s temporality is fundamental to her criticism of Heidegger as a whole.3 Barash describes Heidegger’s ontology as being a type of existential “futurism”, whereas Arendt stresses the importance of memory and remembrance more greatly than Heidegger (Barash 2002: 172–6). For Arendt, memory and origin are fundamentally related to the capacity for humans to act politically.

Arendt connects the notion of natality within Augustine’s thought to gratitude for all that has been given. This links natality with Arendt’s idea of amor mundi, or love the world. Whereas so much philosophical analysis in Western philosophy emphasizes abstract and eternal realities, Arendt insists that a love of this world is needed. In the Augustinian framework, remembrance and gratitude quiet the fear of death (Arendt 1996: 52). Arendt describes the love that seeks eternity as a kind of recollection, a return to the self and to the Creator who made the self, linking it with origins (ibid.: 50, 53). This appreciation of the past is an appreciation of God’s part in the creation of the universe and of the self (ibid.: 50). Arendt then connects the awareness of the origin to the potential for human action. It is because humans know and are grateful for their origin that they are able to begin and act in the story of humanity (ibid.: 55). Arendt notes that Augustine uses two different words to describe the difference between the beginning of the universe and human beginnings. Principium refers to the beginning of the universe, while initium refers to the human beginnings as they act in the world (ibid.). The remembrance of the origin involves both facets, although Arendt notes that for Augustine, it seems that the initium of a human being is equally, if not more, important (ibid.: 55; Arendt 1958: 177 n. 3). Augustine is on to something with his examination of the importance of remembering origins for Arendt. Because of his interest in birth and gratitude for the world, there is the potential for a real connection to the importance of things in this world and an understanding of the meaningfulness of each individual life. However, Augustine’s Christian ideology forecloses this possibility for Arendt due to the way that Christianity understands the world, the individual’s role in it and the proper relationships to other people. The Christian world-view prioritizes the eternal and heavenly over earthly events affecting mortal humans.

Arendt asserts that for Augustine, human beings have a crucial temporal role. The existence of mortals who live life sequentially means that time and change can be marked and events in the universe can have a purpose when viewed sequentially. Different from God’s time of eternal simultaneity, humans mark what occurs in the world, and contribute to it through action. She concludes in her English revision that “it was for the sake of novitas, in a sense, that man was created” (Arendt 1996: 55). Although Heidegger also examines humanity’s relation to time, he does not emphasize the fact of birth in Being and Time except to say that we are thrown towards our deaths, since being born and dying are beyond our free choice.4 Arendt specifically points to Heidegger as someone who promotes expectation of death as unifying human existence (ibid.: 56). In contrast, she asserts that it is remembrance of the origin that is important, giving “unity and wholeness to human existence” (ibid.). She states “Only man, but no other mortal being, lives toward his ultimate origin while living toward the final boundary of death” (ibid.: 57, emphasis added). It is not only mortality, but natality, that leads to action.

Arendt’s English translators, Scott and Stark, emphasize that it is Augustine who guides Arendt in abandoning Heidegger’s death-focused phenomenology, by focusing instead on birth and origin (ibid.: 124). However, Arendt is not entirely uncritical of Augustine, and the last third of the dissertation examines a problem that arises out of Augustine’s Christian and Platonic worldview. In his own way, Augustine also prioritizes eternal things, such as the eternity of the soul and the eternal nature of the universe as God’s creation. Therefore, he does not acknowledge the importance of acts on this earth. The greater importance of the whole of creation and its eternal nature means that the individual life has little significance, especially outside of its potential for heavenly existence (ibid.: 60). Arendt states that for Augustine “life is divested of the uniqueness and irreversibility in which temporal sequences flow from birth to death” (ibid.). All of creation is deemed to be good as part of God’s creation. Actions only seem evil if one does not adopt the perspective of the whole and looks at events as sequential, instead of simultaneous in God’s time. Unique events are not good because of their individual distinction, but only because they are part of God’s universe. Consequently, the individual is “both enclosed and lost in the eternally identical simultaneity of the universe” (ibid.: 62). Human life does not possess autonomous significance outside of the eternal plan. Arendt believes that Augustine’s failure to acknowledge the importance of an individual life is Platonic in origin and is another instance of emphasizing the eternal and abstract at the cost of the earthly. In this sense, humans are not “worldly” and do not love this world (ibid.: 66).

In fact, to be saved, humans must pick a love that is outside of the world, caritas, as opposed to cupiditas that clings to the worldly (ibid.: 78). Cupiditas or covetous, sinful love detaches individual things from God’s creation and sins by doing so (ibid.: 81). Alternatively, choosing God through the right kind of love, caritas, makes the actual world a “desert” for Arendt, since the saved person can live in the world only because they have oriented themselves towards God and eternity (ibid.: 90). Those who will be saved view the world as God does, which raises questions for Arendt about neighbourly love. Love of the neighbour comes from caritas, but as such, is not a love that acknowledges the neighbour’s worldly existence (ibid.: 93–4). To love a neighbour in the proper way for Augustine, one must renounce oneself and worldly relations in order to imitate God. Instead of loving neighbours for their uniqueness, love of the neighbour “leaves the lover himself in absolute isolation and the world remains a desert for man’s isolated existence” (ibid.: 94). Every human is the same, as part of God’s creation, and not loved for any other reason. Humanity is alienated from the world and from each other. As Elizabeth Young-Bruehl describes it, since humans love neighbours for the sake of God, “love of our neighbors for their own sakes is impossible and … our neighbors are used” (Young-Bruehl 2004: 493). In this case, neighbours are loved as vehicles to gain salvation and to satisfy craving by enjoying the love of God (ibid.: 492). The common traits of humans, like their being part of God’s creation and their need to imitate Christ are emphasized by Augustine, rather than what is unique and distinct about them. Within this context, Arendt’s criticisms of Augustine’s love of the neighbour imply a needed shift in focus to the positive relation one could have with others by acknowledging the significance of their lives in this world. Arendt’s criticisms of Augustine’s love of the neighbour can be applied to Heidegger’s philosophy as well because both Heidegger and Augustine prioritize an authentic self or authentic relation to God, over engagement with others in the political realm.

The importance that Arendt places on natality and the fact that humans are born with such potential for individual distinction is paramount in her political philosophy. Although her concept of political action is not examined in relation to Augustine, it seems that both in the original dissertation and through her English revisions, her criticisms about Western philosophy typically ignoring natality emerge and are restated. By ignoring natality, those who focus on the eternal and emphasize contemplation above all else, miss the significance of this realm. For this reason, Elizabeth Young-Bruehl argues that Arendt’s interest in natality has its roots in her thesis on Augustine, but also in her personal political experiences as a displaced German Jew during the Second World War (ibid.: 495). To ignore the political, earthly realm because of ideological or intellectual concerns could result in deadly earthly consequences. For Arendt, it is not always problematic to be interested in things of this world, but rather, quite the reverse. To ignore this world at the expense of some ideal vision of politics allows for untold evils to occur. Furthermore, it misses what is precisely important about humanity: their potential to act and to be distinct individuals whose earthly lives are meaningful. Arendt argues that in both Christian and Platonic worldviews, the emphasis is on non-earthly matters, making efforts to distinguish oneself in this realm futile (Arendt 1958: 21). In Between Past and Future, Arendt connects Augustine’s discussion of “beginning” with freedom and the ability to act. She states “Because he is a beginning, man can begin; to be human and to be free are one and the same. God created man in order to introduce into the world the faculty of beginning: freedom (Arendt [1961] 1968: 167). As Scott and Stark note, if Arendt had not examined Augustine’s work, “it is difficult to imagine the context out of which her analysis of freedom and its relationship to politics may have emerged” (Scott & Stark 1996: 147). Similarly, Young-Bruehl comments that despite her criticisms of Augustine’s philosophy, it is through the writing of her thesis that Arendt begins to retrieve natality from its neglect by philosophy (Young-Bruehl 2004: 495). Although the seeds of Arendt’s concept of natality emerged in her thesis on Augustine, her later work describes the concept in much more detail.

Natality fully formed

Arendt’s notion of natality is more fully developed in arguably her most important work, The Human Condition. This book lays out the framework for Arendt’s political theory in which political action is central. The activity of labour, which is the unending effort to sustain the survival of human life, and the activity of work, which builds a world of permanent things, are necessary preconditions for political action. For Arendt, the activities of labour and work are connected to natality “in so far as they have the task to provide and preserve for, to foresee and reckon with, the constant influx of newcomers who are born into the world as strangers” (Arendt 1958: 9). Since natality grounds all initiative, it is related to labour and work. However, action has the closest connection with the human condition of natality. She states that “the new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting” (ibid.: 9). Of all parts of the active life, political action is most connected to initiating something new, and that capacity is the result of natality, or the fact that humans are born with untold potential.

Action is grounded in natality, but it also relates to the human condition of plurality. Arendt describes plurality as “the condition – not only the conditio sine qua non, but specifically the conditio per quam – of all human life” (ibid.: 7). Plurality concerns the fact that all human beings are unique and different from one another, but also political equals. With the idea of plurality, Arendt is not focused upon the physical differences between humans, which she calls otherness (ibid.: 176). Although otherness is connected to plurality, otherness is shared with all organic life, and even inorganic objects. Therefore, otherness is not distinctly human (ibid.). On the other hand, plurality concerns who a person is. The plurality that is displayed in human political action is the fact that “nobody is ever the same as anyone else who ever lived, lives, or will live” (ibid.: 8). Plurality is inherent in the human condition and Arendt’s politics are attentive to the important differences between humans. Whereas Platonic-inspired political theory shapes the political community based upon participants conforming to a true ideal of the most just state, Arendt expects disagreement in politics based upon legitimate differences in points of view. It would be anti-democratic to get rid of plurality, but also, it would replicate the Platonic or Christian model which minimizes the significance of earthly events. Plurality is exemplified in political action, through what individuals accomplish and what they reveal about themselves to the world.

The most important trigger for political action is natality. To act means to begin something new and it is because they are “initium, newcomers and beginners by virtue of birth, men take initiative, are prompted into action (ibid.: 177). Arendt quotes Augustine, once again showing how her ideas about natality are reflected in Augustine’s thought. She translates Augustine’s Latin into “that there be a beginning, man was created before whom there was nobody” (ibid.). For both Arendt and Augustine, each birth is unique and brings something new into the world. New political actions are grounded in the fact that each person can begin. Someone’s effect on the world cannot be predicted or controlled, but what can be assured is that it will be different due to human plurality. Arendt calls political action the actualization of the condition of natality, which answers the question: “Who are you?” (ibid.: 178). It is through action in words and deeds that “men show who they are, reveal actively their unique personal identities” (ibid.: 179). Acting and beginning allow humans to disclose who they are to others. Arendt’s difference from Heidegger is quite clear on this point. Although natality affects labour and work as well, Arendt thinks “natality, and not mortality may be the central category of the political, as distinguished from metaphysical, thought” (ibid.: 9). Arendt agrees with Heidegger and Jaspers that death is an important limit on human life, and represents an existential boundary condition, but she ultimately thinks that birth is more crucially connected to politics. Therefore, to ignore birth, may very well result in philosophical theories that ignore the active life as well. Her difference with Heidegger’s approach is demonstrated in the following. She states:

The life span of man running toward death would inevitably carry everything human to ruin and destruction if it were not for the faculty of interrupting it and beginning something new, a faculty inherent in action like an ever-present reminder that men, although they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin.

(Ibid.: 246, emphasis added)

Action is what is distinctive about humanity and it interrupts the natural life cycle with something new and surprising. A focus on mortality, instead of natality, ignores the hopeful beginnings that occur within a mortal life. In her last work, The Life of the Mind, Arendt suggests that if Augustine could draw out the correct consequences of his view, he would have defined humans as “natals” as opposed to “mortals” (Arendt 1978b: 109). It is what occurs by virtue of birth that defines who human beings are. Furthermore, in contrast to Heidegger, a focus on natality implies a more positive relationship to others, since it is Arendt’s view that action is not evaluated on its own, but needs other people for its meaning to be assessed. It is the spectators and witnesses who judge human action and decide its meaning. Who a person is cannot be disclosed in isolation but requires a community into which the action falls. Ultimately, death happens alone, so focusing on the phenomena of death is much more isolating. It is not surprising that by prioritizing mortality, as opposed to natality, the result would be a largely negative analysis of interpersonal relationships, as in Heidegger’s case.

Arendt often discusses the miraculous nature of action that is grounded in natality. Arendt suggests that the “new” appears as though it is a miracle, because it seems to arise against all odds (Arendt 1958: 178). In The Human Condition Arendt states that action is the “only miracle-working faculty of man” (ibid.: 246). She continues:

The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, “natural” ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is, in other words, the birth of new men and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born.

(Ibid.: 247)

For Arendt, the potential that humans have by virtue of being born allows humans to have faith and hope for the world because new possibilities for action occur with each new birth (ibid.). When discussing the miraculous nature of action, Arendt often references Jesus of Nazareth. Arendt is not concerned with the divine qualities of Jesus, but the philosophical implications of his worldview. She believes that the “glad tidings” of the Gospels can be viewed as relating to the miraculous nature of action. Moreover, Arendt connects the statement that a “child has been born unto us” from the book of Isaiah explicitly to natality. Arendt allegorically extends this saying beyond the birth of Jesus, to being an expression of faith and hope for the world generally, since the birth of a child signifies a new hope (ibid.). For Arendt, “miracle working” can be understood as being within human capacities because humans can interrupt the world with new beginnings (Arendt [1961] 1968: 169). These beginnings cannot be predicted and are surprising, lending to the seemingly miraculous nature of the event. This does not mean one should wait for specific miracles to cure society’s ills, but one could “expect” the unforeseeable and unpredictable in human affairs because of the arrival of new actors and their plurality (ibid.: 170). In fact, Arendt thinks political action is like a “second” birth by beginning something new and disclosing who one is (Arendt 1958: 176). She states that the impulse for this second birth “springs from the beginning which came into the world when we were born and to which we respond by beginning something new on our own initiative” (ibid.: 177). Unlike our initial birth, this metaphorical re-birth is chosen and confirmed by human actors through their action. By acting, actors reveal who they are and are remembered.5 This “re-birth” springs from our natal condition and our ability to begin something new.

In contrast to her analysis of Augustine who seeks immortality in the realm of the afterlife, Arendt thinks there is the possibility for immortality in the actions of political actors on this earth. She models this idea after the views of the pre-philosophical Greeks, whose memorable actions are described in the works of Homer and Herodotus. For Arendt, the pre-philosophical Greeks admired political action most of all. The primary concern of politics was not legislating, but acting memorably before a community. Largely, this was because human actions in words and deeds have an immortality to them that can be remembered after the actors die. Arendt claims that all that remains after death is the stories that can be told about that individual (ibid.: 193). For the pre-philosophical Greeks, to not be remembered is equivalent to living and dying like animals (ibid.: 19). It is through political action that humans appear to each other as distinctly human. Entering the common, public world allows persons to outlast their mortal lives and be remembered (ibid.: 55). Arendt states that when the agent is disclosed in the act in a profound way, the act shines in brightness and in glory (ibid.: 180). This act is remembered, in memory, in narratives, or more officially in monuments, documents or art (ibid.: 184).

Arendt insists that the actor cannot control what will be disclosed in his act and, therefore, it should not be thought of as a mere means to an end, which would allow the actor to fabricate his public persona (ibid.). Actions reveal an agent, but one who is not the author or producer of his own life story, because one cannot control how others will remember particular actions (ibid.). In fact, the narrative about an action can change over time, if new facets of the act are later revealed or if the community itself changes, and therefore, the public reception of the act may change. Unlike objects, which can be shaped and controlled through human fabrication, human beings are not materials to be managed (ibid.: 188). Actions are unpredictable, and result in disclosures of individuals without their total pre-knowledge or control. In contrast to some philosophical, economic or religious theories that tend to view history as being made by individuals who can pull the strings or direct the play, Arendt rejects this type of manipulation and alternatively grounds history on the memories of the community (ibid.: 186). Consequently, action requires courage, since the reception of action cannot be controlled and one risks negative exposure (ibid.). One must be willing to leave the protection of private life and expose oneself to the judgements of others in action. For Arendt, the reason that action is unexpected and cannot be predicted is because of natality (ibid.: 178).

Although one can readily recognize the need for the individual life to be disclosed and remembered, a troubling aspect of Arendt’s analysis is that it appears that this occurs only through political action. Recognition and remembrance occur privately for everyone in our relationships with others, however. Arendt states that all lives can be told as a story and she names this fact as the pre-political and prehistoric condition for history (ibid.: 184). Publicly, however, immortality and distinction occur primarily for those interested in politics. Arendt comments that not everyone would want to participate in politics. In fact, she describes herself as a political thinker, not a political actor. Additionally, even if one acts politically, the likelihood that one’s acts will be remembered are not good (ibid.: 197). Arendt does not discuss this issue, but it seems that public self-disclosure is possible if one is interested in politics, perhaps in other areas of public engagement, but it will not occur for all and more often than not, the acts themselves will be forgotten. It is understandable that the greatness of action is not egalitarian and many acts are forgettable. Yet, since actual self-disclosure of “who” one is seems inextricably linked to public, political life, it is troubling that it will not occur for most. Nonetheless, Arendt’s criticism that the respect for political action has been lost because modern life fails to recognize the importance of individual actions is notable. Politics is important. Arendt thinks that politics should not be thought of as a game of manipulation by those involved, but as a stage upon which an actor courageously relinquishes control and reveals himself. Since politics has come to be understood as being like controlled fabrication, Arendt asserts that there has been “almost complete loss of authentic concern with immortality” (ibid.: 55). This means there is failure to recognize the unique importance of individual life as well as the importance of specific earthly events.

Conclusion

Hannah Arendt was interested in birth, and what she would later call natality, from the very beginning of her career. Her interest in political action and plurality are rooted in the concern for natality and events that occur throughout one’s life on earth. Plato famously compared philosophy to practising for death, since he thought philosophers are well versed at separating the soul from the body when they use their minds to ascertain the truth (Plato 1995: 235). Arendt rejects this approach by keeping her mind attuned to the appearance of life. For Arendt, interests in eternal truths or political or philosophical ideologies should not always take precedence over more worldly actions. It is through the fact of birth, so easily ignored by the tradition of philosophy, that a more deeply held appreciation of individual and collective life can emerge.

Notes

1. Scott and Stark (1996) argue that the seeds of many of Arendt’s concepts like the pariah-parvenu as well her distinctions between the public, private and social, come from her work on Augustine (Arendt 1996: 125–34). Other thinkers are less focused on the importance of the work with Augustine. Margaret Canovan stresses Arendt’s rejection of many parts of Augustine’s thought. Canovan observes Arendt’s need to change so much of the original thesis during the translation process so that it more greatly resembled her later theory (Canovan 1992: 8). It should also be noted that since Arendt did not complete the revision for translation into English, it suggests she was in some way dissatisfied with the work.

2. Frederick A. Olafson (1998) argues that Heideggerian ethics could be grounded in his concept of Mitsein, even though Heidegger does not discuss this directly.

3. It should be noted that Arendt also thinks that Augustine is guilty of overemphasizing the future, because of his interest in eternal salvation (Arendt 1978b: 109).

4. Anne O’Byrne argues in Natality and Finitude (2010) that Martin Heidegger’s work can be viewed as suggesting numerous implications for natality.

5. Ann W. Astell (2006: 376) links the “second birth” to Saint Augustine’s second birth when he was reborn in Christ.