Why Trump's tariffs are better than you think — and much worse

Bumper edition including other things I happened upon this week

Bernard Keane to cross-bench: Here’s how you can major party-proof politics for decades

Bernard Keane joins Club Michigan, proposing we build sortition (selection by lottery) into politics as usual.

Community independent MPs who might hold the balance of power after the coming election could have a relatively limited window to force the major parties to comply with their demands. The experience of Australia’s last minority government, from 2010-13, was of an initial honeymoon period that gave way to the Gillard government reneging on its commitments to Andrew Wilkie regarding gambling reform, and eventually walking away altogether from the Greens on whom Labor relied for lower house support.

While the independents have issues that are — rightly — a priority for them like genuine climate action and tax reform, delivering a longer-lasting impact on how government works in Australia should also be a priority. Individual policies can be overturned by the next majority government; structural and institutional reforms can last much longer. One of the Gillard-era reforms that has stuck, for instance, is an independent Parliamentary Budget Office, even if it’s currently too small to deliver the kind of impactful fiscal advice that would genuinely worry the major parties.

Keane proceeds to list numerous additional initiatives such as

the creation of a US style Government Accountability Office, which churns out a massive number of audits and evaluations of US government programs and offers policy insights gleaned from assessing the effectiveness of government policies.

Lifting funding for the auditor-general to enable it to produce one report a week.

Annastacia Palaszczuk’s ending of the absurdity of keeping cabinet papers secret for decades should be copied.

Freedom of information laws should be strengthened to curb the capacity of the public service to delay and refuse requests and significantly reduce the grounds on which documents can be censored before release.

And Helen Haines has already prioritised repealing Don Farrell’s attack on independents via political funding laws.

These would significantly improve the accountability of governments and how they run their programs. What they wouldn’t do directly is lift the overall standard of policymaking, or expand policymaking into areas the major parties consider no-go zones, like genuine climate action, or reversing the rotten GST deal with Western Australia, or properly taxing profits from offshore gas.

Helen Haines has already prioritised repealing Don Farrell’s attack on independents via political funding laws. Th[is and other reforms] would significantly improve the accountability of governments and how they run their programs. What they wouldn’t do directly is lift the overall standard of policymaking, or expand policymaking into areas the major parties consider no-go zones, like genuine climate action, or reversing the rotten GST deal with Western Australia, or properly taxing profits from offshore gas.

A reform that would change that dynamic is one championed by, inter alia, economist Nicholas Gruen, who has pushed the idea of citizens’ assemblies for some time. Not an issue-specific citizens’ assembly, as Allegra Spender and other independents have proposed for housing policy (and the Greens proposed for climate policy in 2010) but a standing assembly that could set its own agenda and pursue issues of public policy it deemed worthwhile.

Crucially, the standing assembly would be chosen by sampling, like juries in the court system, rather than election (Gruen explains the pluses and minuses of both approaches here). It wouldn’t have legislative power, though it could have some of the powers of, say, Senate committees, such as asking public officials to give evidence. Gruen suggests one mechanism by which the assembly could interact with Parliament proper — requiring a secret parliamentary ballot on an issue where Parliament has declined to agree to the assembly’s proposals.

But the primary benefit, surely, would be to introduce a genuine contest in policymaking. Currently policymaking is dominated by the party that controls the executive. There is some limited non-executive policymaking apparatus available via parliamentary and particularly Senate committees, though these are usually controlled by one or other of the major parties. A standing assembly prepared to investigate issues the major parties don’t want to touch, to conduct hearings, debate solutions and produce its own recommendations, would disrupt the major party control of policymaking (and help push the media out of its policy laziness).

There are plenty of practical questions about how it would operate — Gruen tackles some of them here — but he repeatedly points to the success of the Michigan Independent Citizens’ Redistricting Commission, a 13-member standing body picked by lottery that ended gerrymandering in that state by Republicans and Democrats after a 2018 vote took the power to draw electoral boundaries away from politicians.

Such bodies are no more perfect than other human institutions, but the Michigan commission is now seen as a national example to address the blight of gerrymandering. Such an assembly would represent a genuine source of fresh thinking in what is an increasingly stale and rigid governmental process controlled by the major parties and their partisan conception of what is possible. It might also stick well beyond when the current generation of politicians has moved on.

The dirty electoral funding deal: how to get something better.

I talk to Leon Gettler about the way electoral funding is manipulated by the major parties to entrench their own power.

Democracy is supposed to be a competition, not a rigged game, yet we see politicians making decisions that serve their own interests rather than the public good.

I argue that it's absurd to have politicians determining the terms of political competition — they should have no more to do with that than they should with setting electoral boundaries.

We need a new kind of institution—one that takes key decisions like electoral out of the hands of politicians and puts them in the hands of a jury of everyday Australians.

I discuss the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, a model that has helped clean up gerrymandering in the U.S., and how a similar approach could work here.

Listen to the podcast here, or click below.

Jay is stumped

I’ve admired Jay Rosen’s media analysis for some time. He was one of the early and most consistent critics of he-said-she-said journalism. I wondered where he was up to because, as much as he-said-she-said journalism gives me the shits, when you think about the alternatives, which are reporting more truthfully, you’re likely to lose the audience who loses out in your choices. So you don’t really get to lean against the escalating lies in any politically significant sense. Anyway, judging from these tweets, Jay’s stumped. I sympathise.

Why Trump’s tariffs are better than you think — and much worse

Gene Tunny and me in Crikey!

When economists tell you Donald Trump is *all* wrong about foreigners paying for his tariffs, don’t believe them. When large countries trade, they move prices.

A brash new president sweeps into power. He knows one thing: his country is getting ripped off. Disdainful of experts and the lumbering processes of the domestic and international legal order, he slaps tariffs on imports from countries with which he renegotiated free trade agreements. He even wants to make imperialism great again.

If this were a small country, it would be quickly and severely punished. With small countries more dependent on trade, imposing tariffs has a similar effect to putting rocks in their harbour. Its trading partners would swiftly retaliate. More rocks.

But the new president I’ve described presides over the United States — the world’s largest consumer market, the issuer of the dominant reserve currency and the anchor of global financial flows. And that changes everything.

Small countries generally trade at the world price. So their consumers pay the tariff. Donald Trump is wrong that foreigners will pay his tariffs. But, when economists tell you he’s all wrong, don’t believe them. When large countries trade, they move prices. That means foreigners do effectively pay some of their tariffs. With free trade a shibboleth of our profession, economists keep forgetting it, but we’ve known of this so-called “optimal tariff” argument since at least 1844.

This means that for large countries, tariffs create two offsetting effects. First, they harm an economy by “distorting” it — moving production and consumption away from their optimal configuration. This “rocks in the harbour” effect is minimal when tariffs are low because it rises as the square of the tariff. By contrast, the terms of trade effect are linear. So, below some moderate level, tariffs induce more in terms of trade gains than they cost in distorting the economy.

Simple, indicative modelling by Lateral Economics, of which I’m CEO, suggests gains outweigh losses for a general tariff imposed by the US of up to 40% and that the “optimal tariff” is around 20%.

The US as a whole ends up $135 billion ahead as a result of imposing an optimal tariff.

American consumers lose $75 billion in purchasing power;

Their businesses get a better deal from international markets

Prices paid by importers fall by $89 billion; and

Prices paid to exporters rise by $42 billion.

The additional tariff revenue also funds cuts to more distorting taxes, producing economic benefits of another $79 billion.

So initially, Trump’s tariffs could appear to “work”. That’s where the real trouble starts. The additional costs will be large, but they’ll take time to emerge, particularly in the US.

The terms of trade benefits to America are terms of trade losses to its trading partners.

The speed and capriciousness of imposing tariffs will disrupt some markets as supply chains fracture and bottlenecks emerge.

Trust in American agreements will erode — what’s an agreement with America worth when it can be torn up on a whim? And why negotiate new agreements?

Other countries will begin to reciprocate, both by breaching agreements when it suits them and also by retaliating with their own trade barriers as occurred so disastrously during the Great Depression.

The true danger of America’s tariff experiment is thus not just the immediate economic damage to America’s trading partners and allies, but also the erosion of the very system that has lifted more than 1 billion people out of extreme poverty and underpinned global prosperity for decades.

While the US might benefit in the short and even medium run, it is effectively sawing through the branch it sits on. Though it requires forbearance from the Americans, as from all countries, the international trading system was never built on pure altruism — it was built because even the strongest economy benefits more from being the leader of a prosperous, rules-based order between nations (however imperfect) than the biggest bully in a Hobbesian state of nature.

That lesson, demonstrated economically in the 1930s and militarily in the 1940s, seems to have been forgotten. Whether we’ll have to learn it again hangs in the balance.

And here’s an economist making our point

Claiming that domestic consumers pay tariffs — which isn’t quite true.

Sam Harris and Niall Ferguson on what’s happenning

A friend sent me this as representative of two different ways of looking at the horror show in the White House. I don’t much like either speaker. Sam Harris sets my teeth on edge in ways it would take too long to elaborate here. And I don’t find Niall Ferguson’s history all that interesting and his right wing interventions seem pretty predictable to me.

He made a fool of himself in taking on Krugman a few years ago, parading a misunderstanding of Keynesian economics together with slurring Keynes as childless and gay which, he felt explained Keynes’ line that in the long run we’re all dead. He did at least have the grace to retract his comments calling them “stupid and tactless.”. ‘Tactless’ suggests he still doesn’t appreciate how low his comment was, but ‘stupid’ is roughly on target.

Anyway there’s nothing surprising about Sam’s response. Like most of us, he thinks the way Trump has behaved is disgraceful. But focusing on that stops us asking more important questions that might help us understand what’s going on. I’m neither endorsing or disagreeing with Ferguson’s comments. Time will (probably) tell. But, in their attempt to look at events through the eyes of a ‘realist’ theory of international relations, they do give us a different perspective.

A complete unknown: I loved it

I loved “A Complete Unknown”, the biopic about Dylan. I’ve always thought the hullabaloo about him going electric was silly, and this is that story. It’s a pretty standard kind of bio pic in a way but made electrifying by the actors who played the main characters. The music is all sung live, which definitely gives it immediacy and there’s nothing more alluring than an authentic fake ;)

But the thing that really distinguished it for me was the three way relationship between Dylan, Dylan’s more established girlfriend Suzie and Joan Baez who comes in and out of Dylan’s life. Both of Dylan’s lovers have an “I don’t know how to love him” problem. Now admittedly this problem isn’t quite had at quite that altitude. Mary Magdalen really did find herself in a singular situation — what with her having a huge crush on the Son of God and all ….

Dylan isn’t the the son of God but he does tip the scales as a serious, Grade A Space Cadet and he’s going to be doing what he’s going to be doing. The girls aren’t quite in the same league. Suzie is a complete mess in the face of the vast gulf between her and Bob. Joan understands it too. But there’s more to her than that. She’s got dignity and fight. And the movie shows her with the grace to understand that Bob is a gift she can’t hang onto, even if it took her a good part of her lifetime to come to terms with that.

I thought the scene they talk about in the video above is one of the great scenes in movies. My own interpretation of it seems to be different to the actors’ own interpretation, but this is 1965 when the relationship was pretty much over. So I understood their singing “It ain’t me babe” in the scene not as some kind of reconciliation, but rather the reverse, their letting go and so more fully swimming in the river of life as a result. That’s what the words of the song suggest after all.

Most of the movie is good watching. And I’ll never forget that scene. Go see it.

The original performance

Leo Strauss’s 1941 crack at our problem

Those European expats in the UK and the US from the 30s and 40s on, and a bunch of natives — James Burnham and R.G. Collingwood — had a lot more serious things to tell us about politics than later scholars IMO. Here’s Roger Berkowitz’s latest at the Hannah Arendt Centre for politics and the humanities.

To comprehend the powerful popular and democratic revolutionary rejection of liberal society that is sweeping the world, we need to look clearly at the limits and failures of liberalism. To that end, Matthew Rose has an essay out that offers an account of the difficulty of building a lasting and meaningful liberal and open society. Rose approaches his analysis of the weakness of the open society through a reading of a 1941 speech given by Leo Strauss... Strauss in his lectures asked, "whether liberal societies could endure despite their weaknesses." He sought to defend the open society, but did so by arguing that the open society of liberalism would need to be able to incorporate certain virtues typically associated with strong and closed societies. Specifically, Strauss argued that even an open society needs to cultivate the "martial virtues of courage, heroism, and loyalty," that allow people to prove themselves. His point is that to live a meaningful human life we need more than simply to stay alive, work, and procreate—the goods of a liberal and bourgeois life. As Rose writes:

"Rather, we prove our humanity only by exercising our radical ability to contradict those goods, only by risking our lives for a value greater than mere survival. To live as a human being is to fight to the death for something higher than life. Within this moral world—a world so fundamentally hostile to liberal modernity—man is not made for comfort and security. He is tempted by them. The man who wishes truly to live must flirt with death."

Strauss' 1941 lecture was titled "German Nihilism." As did Arendt, Strauss saw the way that nihilism led to what Arendt called a justified disgust at liberal society. That both Strauss and Arendt wanted to save liberalism from itself does not mean that they thought they could ignore its weaknesses. For Strauss... the weakness of liberalism was its rejection of the values of a closed society. Rose explains:

"Strauss assumed his American students might have difficulty seeing the possible strengths, to say nothing of the seductive appeal, of a way of life associated with ignorance and bigotry. He therefore tried to show them how liberal and democratic ideals might appear from a perspective that denies their moral legitimacy—not out of resentment or bad faith, but out of loyalty to a higher order of values. The rights of man, the relief of the human estate, the happiness of the greatest possible number—for advocates of the open society, these are ideals that have inspired social progress... But to defenders of the closed society, Strauss argued, the moral prestige of these slogans evinces a different kind of shift. It is a sign that humanity has been debased rather than ennobled.

To draw his listeners into anti-liberal ways of thinking, Strauss sketched the development of modern political thought from the perspective of the closed society. This interpretation casts the arc of modernity in a disturbing light, depicting as decline what Enlightenment thinkers hailed as advance. It sees modernity as the story of how and why Western societies chose to lower their moral ideals, exchanging the demanding codes of antiquity and biblical religion for the comfortable norms of commercial society... Heroic ideals, attainable only by the exceptional few, were defined down for the ordinary many; ideals that promoted spiritual or intellectual excellence were balanced by those promoting health and prosperity; ideals that imposed self-denial were replaced by those that indulged self-expression.

As Strauss's reading of modernity suggests, the closed society is defined by what it affirms no less than by what it rejects. He emphasized that its conflict with the open society is ultimately over the most fundamental question: Which way of life is best for man? For defenders of the closed society, human life should be ordered to a political end whose achievement requires the highest and rarest human qualities... As Strauss described it:

Moral life . . . means serious life. Seriousness, and the ceremonial of seriousness . . . are the distinctive features of the closed society, of the society which by its very nature, is constantly confronted with, and basically oriented toward, the Ernstfall, the serious moment... Only life in such a tense atmosphere, only a life which is based on constant awareness of the sacrifices to which it owes its existence, and of the necessity, the duty of sacrifice of life and all worldly goods, is truly human.

Duty, sacrifice, danger, struggle—here we enter the charged atmosphere of a moral world that Strauss feared his students... failed to understand. It saw the best human life as one that dares to risk all for the sake of heroic possibilities. It saw the desire to pledge oneself to a great cause and to prostrate oneself before great authorities as essential to human virtue... But the conflict between the open and closed societies is not a conflict between reason and revelation. It is a conflict over the necessity of life-and-death struggles for human excellence. If the open society is constituted by free argument and equal recognition, the closed society is formed by loyalty, courage, sacrifice, and honor. It celebrates the virtues that it believes make political order possible: the willingness to forgo material comforts, to close ranks against outsiders and oppose enemies, and, above all, to fight to the death with no thought for profit or pleasure..."

That Strauss saw value in the moral vigor of martial and tribal values does not mean he wanted to trade an open society for a closed society. He was, as Rose sees, "alarmed by the ease with which theoretical attacks on liberalism could turn into excuses for political evil." Instead, he argued that to preserve liberalism we would need to develop a pedagogy and culture that incorporate elements of the closed society with the open society. Rose writes:

"But as Strauss looked to the war raging in Europe and imagined a future that learned from its mistakes, he proposed a strikingly different form of education. He argued that good teachers should not seek to dispel the allure of the closed society; instead, they should carefully draw students directly inside of it. This pedagogy would enable students to experience the power of the closed society's moral demands, to sense the appeal of its political life, and to feel challenged by its vision of human excellence."

Strauss didn't wish to turn his students into sophisticated enemies of liberalism. His goal was to turn them into virtuous defenders of democracy. But to become true patrons of the open society, they needed qualities of character that could be developed only through a proper appreciation of traditional society ... The closed society was also right about some important things. It acknowledged our need to be loyal to a particular people, to inherit a cultural tradition, to admire inequalities of achievement, to reverence the authority of the past, and to experience self-transcendence through self-sacrifice. … As Strauss observed, these are permanent truths, not atavisms, no matter how unpalatable they are to the progressive-minded. A society that cannot affirm them invites catastrophe, no less than does a society that cannot question them.

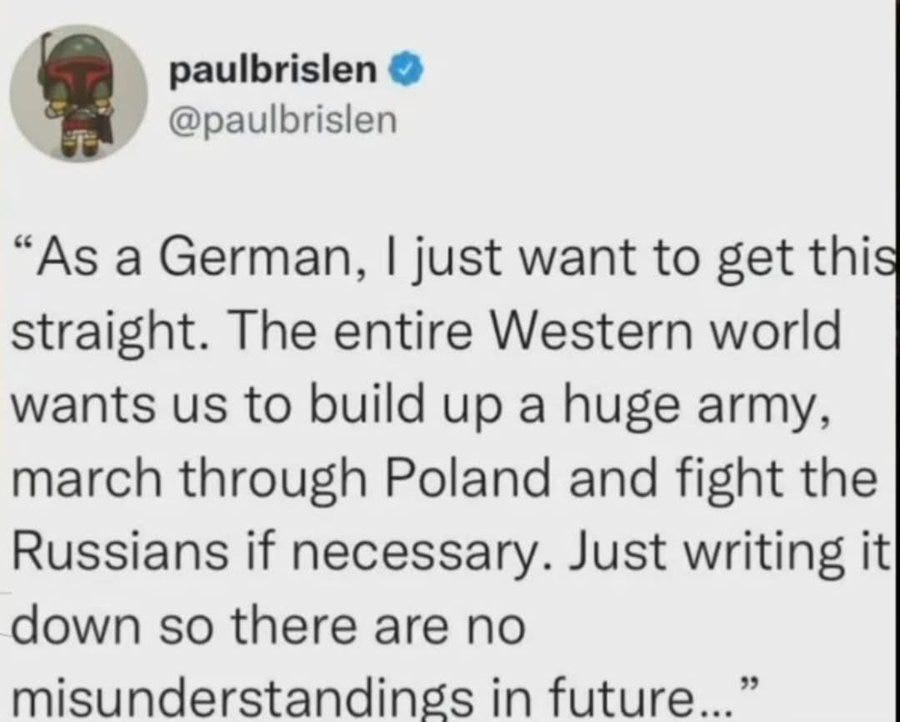

Henry Ergas on Ukraine

Henry Ergas takes on Tom Switzer’s realpolitik on the US, Ukraine and Russia.

Tom Switzer attempts to justify Russia's invasion of Ukraine and excuse Donald Trump's recent actions as morally and politically legitimate. Switzer's method is simplicity itself. The West … has been consistently ill-intentioned and aggressive, seeking to encircle Russia through NATO expansion. Russia, in contrast, has been consistently well-intentioned and defensive, merely responding to the West's belligerence.

Aggravating its culpability, the West, once the invasion was under way, refused to take peace negotiations seriously, rejecting Russian proposals aimed at ending the hostilities. To be faced with these claims is to struggle with the dilemma a bee faces in a nudist colony: one scarcely knows where to begin.

But given how often it is raised, the constant complaint about NATO expansion, which casts Russia as yet another victim in the unending pantheon of global victimhood, provides a useful starting point. To view the expansion of NATO as an exercise in encircling Russia is geographically and historically absurd. …

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the countries it had suborned were left with Communist era militaries desperately needing fundamental reform. … NATO's programs, going from partnerships to memberships, helped implement sweeping reforms while providing a crucial stabilising degree of mutual assurance.

Those objectives were clearly articulated and explicitly accepted by Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin. But even putting that aside, Switzer's claim encounters obvious difficulties.

To begin with, NATO expansion cannot explain Russia's attacks on the sovereignty of Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, much less the full-scale invasion of Georgia in August 2008. In none of those cases was NATO even vaguely at issue …

Additionally, the claim misrepresents the outcome of NATO's Bucharest summit in April 2008. Far from endorsing Ukrainian accession, that summit, as journalist Sylvie Kauffmann has painstakingly shown using French and German diplomatic sources, buried it for all time. Moreover, France and Germany, which led the intransigent opposition to Ukrainian accession, made that abundantly clear to Putin while giving firm assurances as to the future.

The summit was therefore anything but a Western provocation; on the contrary, the veto German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Nicolas Sarkozy placed convinced Putin he could get away with dismembering Georgia and Ukraine. …

Last but not least, the encirclement hypothesis is at odds with what was the Ukraine invasion's predictable consequence: not just NATO's revitalisation but its extension – which the Soviet Union had done everything it could to avoid – to Sweden and Finland, exposing Russia's northern flank.

Were Russia really concerned about potential NATO aggression, it is impossible to conceive of an outcome that would pose greater strategic risks.

Nor do Switzer's claims about the Ukraine peace negotiations fare any better. … the French and Germans were eager, if not desperate, for a deal to be done. And there is every sign the US would have readily accepted a reasonable outcome. What was always lacking was any serious commitment by Putin to halting a war of attrition he firmly believed Russia would win.

In the end, Switzer's purported explanations, which portray Russia as purely reactive, fail because they ignore the internal dynamics that propel the Putin regime's incessant aggressiveness. …

Switzer ignores the plain, unvarnished truth: that given those dynamics, the Putin regime will pursue its global efforts to destabilise and suborn for so long as it can do so at a cost it finds bearable. And for exactly that reason, a ceasefire will bring a durable peace only if it is accompanied by credible security guarantees – guarantees the US alone has the military capabilities to provide.

But rather than providing those guarantees, the Trump administration is sharing in the loot, compelling Ukraine to pay, through mining concessions, for the assistance it has received. The contrast between [WWII’s Lend Lease which had no hard repayment obligations and was more than made up for by Marshall Plan aid] and now is bad enough. To dress it up as morally and politically justified is an appalling error of judgment.

Joy

Education for the very serious people

Another great article from Dean Ashenden on our flailing education system.

The Vatican has the Dicastery of the Doctrine of the Faith. Australian schooling has AERO. New, not very important but very symptomatic, the Australian Education Research Organisation fits snugly into the elaborate machinery of Labor's "national approach" to schooling. … But its key sponsors hope it will proclaim the doctrine in a system dependent on prescription, surveillance and compliance.

The doctrine is this: schooling is first and foremost about knowledge; teaching is first and foremost about getting prescribed knowledge into young heads; … teaching must be based on evidence supplied by this research. The faith: that in this way the long slide in the performance of Australian schools will at last be arrested and reversed.

In AERO's view, though, there is no doctrine or faith. … The point? To inform and prompt thinking, interpretation, explanation: what is this evidence telling us? What do these numbers mean? What's going on here, and why? What, for example, should we do with evidence showing that smaller classes have not produced better performance? Just say: no more smaller classes? Or ask why smaller classes aren't being used more effectively? How can we actually do what effectiveness research has made possible? Research can go only so far; it reflects schooling as it is, not how it has to be; the rest is up to government and policy. …

But teachers are not like medical practitioners and students are not like patients. Teachers try to enlist students in their cause; students might or might not join in. [They might do their best to make sense of what the teachers seems to want, or pretend that they're trying to, or subvert or resist the teacher's efforts in myriad ways.] Much of what students learn is not what is taught but what students think has been taught; often it has not been taught at all, for students learn all kinds of other things in the classroom and everywhere else at school. They learn about themselves, the world, how the world treats them, and how they can and should treat others. Students are, in other words, co-producers of learning, of themselves, and of each other. They learn, and they grow.

What students learn and how they grow, taken in its full extent and complexity, depends partly on what teachers do but mostly on the circumstances in which they and teachers meet. … The central question is not how to make teaching more effective (as effectiveness research assumes) but how to make schools more productive. Which combination of the many factors of production is most productive of what kinds of learning and growth for which students? The failure to ask what the evidence is telling us about what is going on and what could go on is the seed of the policy failure ….

One of the consequences of AERO's use of … effectiveness research is the assumption that teaching "knowledge" is the only game at school and there is only one way to play it. Of course knowledge is core business in schooling: knowledge of reading, writing, maths and science are "basic"; didactic teaching is for most kids and some purposes the shortest route between a fog and an aha! moment; the precepts of "explicit" teaching may well help to improve didactic teaching; and "effectiveness" research and its "effect sizes" can indeed make teachers and school leaders more aware of options and less reliant on hunch, habit and anecdote.

But what about other kinds of classroom teaching? And other ways of learning? Is AERO's "teaching model" a one-punch knockout? The sovereign solution to the many things that students, teachers and schools contend with?

To look at AERO's teaching model is to wonder whether the organisation is living in some other reality, a world in which there are no students who refuse to go to school, or leave school as soon as they can, or last the distance but leave with not much to show for it, or wag it, or bully and harass or are bullied and harassed, … or have little or no sense of "belonging" at school or "attachment" to it. Why on this crowded stage is AERO putting the spotlight solely on what the teacher is doing in the classroom? Can teaching be expected to change the whole experience of being at school? Or is that somebody else's problem?

And what about kinds of knowledge other than formal, out-there, discipline-derived knowledge, the staple that has launched a thousand curriculums … And what about students' knowledge of their own capabilities and options? The suspicion arises that what AERO is after is schooling for the poor, for the denizens of the "long tail of attainment," cheap, narrowed down and dried out, a something that is better than nothing.

As well as misconceiving, AERO is misconceived. Its job is to gather research from up there and packaging it for consumption down below. It wants teaching to be based on research evidence — [on just two kinds of research evidence, in fact —] as if what teachers and school leaders know from experience, debate and intuition isn't really knowledge at all, as if it's research evidence or nothing. That most teachers and others in schools don't use research evidence very often is taken not as a judgement about priorities but as an "obstacle" to uptake.

AERO claims that "evidence-based practices are the cornerstone of effective teaching" without providing or citing evidence to support the claim. More, it implies that the "how" of teaching is the only thing that teachers should concern themselves with, that teaching and schooling are free of doubts and dilemmas, of messy questions of judgement, decision and purpose. …

At the risk of an apparent sectarianism, let me suggest that Martin Luther had the necessary idea: the priest should not stand between God and the flock but beside the flock reading God's Word for themselves and finding their own way to salvation. AERO should stand beside teachers and schools, and it should help them stand beside their students. But that is not what AERO was set up to do. …

AERO is not going to go away, but perhaps it can be pressed to lighten up. It should be persuaded, first, to accept that teaching is a sense-making occupation and that schools are sense-making institutions. Schools should not be treated as outlets applying recipes and prescriptions dispensed by AERO or anyone else.

Second, AERO's evidence should bear on the system in which schools do their work as well as on the schools and their teachers. That should include evidence about whether and how Australia's schooling system should join schools and teachers as objects of reform.

Third, AERO should be pressed to rethink its conception of "evidence." Schools do and must use many kinds of evidence, including some that they gather formally or informally themselves. Evidence derived from academic research may well be a useful addition to the mix, but that is all. It is — and AERO should say so — provisional and contingent, not altogether different from other kinds of evidence schools use. …

And, most important of all: … The lens must be widened to include the organisation of students' and teachers' daily work and the organisation of students' learning careers as well as what teachers can do in the classroom as it now exists. AERO should identify schools working to organise the curriculum around each students' intellectual growth and the development of their capacities as individuals and as social beings. It should put those schools in touch with one another, and work with them on a different kind of research, on finding ways through an essential but immensely difficult organisational and intellectual task.

Billy Budd as political thought … and political tragedy

Fine essay.

Amazing fellow

This guy is an extraordinary fellow and I strongly recommend you acquaint yourself with him if you haven’t. He is powerfully articulate without being facile in expressing himself. It’s a great performance which, as David Marr observes, reaches out to normies with great empathy.

Sadly his appeal remains at the level of humour and empathy, but not at the level of gender ideology. I couldn’t detect any progress from late 70s unisex clichés upgraded for the age of trans. Yes, there’s a lot of transphobia about. No that doesn’t mean it’s OK to allow folks born as men to participate in women’s sport, to use womens’ dunnies and self-identifying their way into women’s prisons and domestic violence shelters without further discussion with women whose interests are involved.

Oh well, you can’t have everything I guess.

Fascinating

Boris Vasilievich Spassky, Mensch: RIP

An ornament to our species has died. He gave what he had.

GM Boris Spassky, the 10th world champion of chess who defeated “Iron” GM Tigran Petrosian in 1969 to reach the chess Olympus and who lost his title to GM Bobby Fischer in the Match of the Century in 1972 in Reykjavik, died on Thursday aged 88. His death was confirmed by the Chess Federation of Russia.

Spassky, who was the oldest living world chess champion—a title now passing to GM Anatoly Karpov—was eloquent and funny, a freethinker, and an anti-Communist. In the late 1960s, he was the best player among the Soviet contingent that was put to a halt by Fischer.

"You can't imagine how relieved I was when Fischer took the title off me," Spassky would later say. "Honestly, I don't recall that day as unhappy. On the contrary, I've thrown off a very strong burden and breathed freely."

This was not only a deliberation many years after the match; Spassky expressed the same feelings when he was interviewed in Reykjavik shortly after the final game.

"You know, I am not disappointed to lose this match. I don’t know exactly why, but I think life for me will be better after this match. Of course, I would like to explain why I think so.

"I had a very hard time when I won the chess title of the champion in 1969. Perhaps the main difficulty is that I had very big obligations for chess life, not only in my country but all over the world. I had to do many things for chess but not for myself as a champion of the world."

Boris Vasilievich Spassky was born January 30, 1937, in Leningrad—a city he himself preferred to call Petrograd, the name that was used from the time of Russia's involvement in World War I until Lenin's death in 1924.

In the summer of 1941, Boris and his older brother, George, were evacuated from the besieged Leningrad to an orphanage in the village of Korshik in the Kirov Oblast. It is said that during the long train ride (the distance is over a thousand kilometers), Spassky learned the rules of chess.

His parents suffered and barely survived. In an interview published in 2017, Spassky tells the story that his father was on the verge of dying of starvation and survived as his wife sold her belongings and brought him a bottle of vodka.

Eventually, their parents took Boris and George to Moscow, where they stayed until the summer of 1946. After their return to Leningrad, when he was nine years old, his brother took him to Krestovsky Island, and there he saw a chess pavilion. It was there where he fell in love with the game.

Much later he would say: "Looking back, I had a sort of predestination in my life. I understood that through chess I could express myself, and chess became my natural language."

Sam Roggeveen on Australia’s defence

Sam cuts through some of the excitement of the recent Chinese Navy visit. Hard headed and knowledgeable. Is he right? How would I know?

Heaviosity half-hour

Philosophy Bear on The Ballad of Reading Gaol

A fine essay.

The Ballad as a rejection of all law and politics

For he who lives more lives than one

More deaths than one must die.

-The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Section IIIThey think a murderer's heart would taint

Each simple seed they sow.

It is not true! God's kindly earth

Is kindlier than men know,

And the red rose would but blow more red,

The white rose whiter blow.

-The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Section IV1.

When I was young a number of horrific experiences convinced me that I could either choose to be wholly on the side of humanity—all of humanity—or a misanthrope. I chose the first option, although I fall short constantly. Trying to explain how that commitment to being on the side of humanity works on the level of feeling—to show how certain ideas are emotionally and aesthetically coherent with each other in order to create a harmony in how I feel about humans in general, is what led me to write this essay.

We'll get to "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" soon, as promised in the title, but before we do I want to take a detour through the Gospel of John. (Don't worry—I'm an agnostic and this isn't going to turn into a religious essay.)

One of the most famous passages in the New Testament is the story of the woman taken in adultery. You may remember it as the story with the line: "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone". It's in the Gospel of John:

"[…] Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. Early in the morning he came again to the temple. All the people came to him and he sat down and began to teach them. The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery; and making her stand before all of them, they said to him, 'Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now in the law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?' They said this to test him, so that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, 'Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.' And once again he bent down and wrote on the ground. When they heard it, they went away, one by one, beginning with the elders; and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus straightened up and said to her, 'Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?' She said, 'No one, sir.' And Jesus said, 'Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again'"

Now my friend Karl Hand, biblical scholar extraordinaire, assures me of two things. Firstly, there is almost no doubt that this passage is a later addition, written by another author. Secondly, among the relatively small number of scholars who defend the authenticity of this passage, most are conservatives. However, in my research, I found that, while evangelical and fundamentalist Christians generally defend the whole of the bible, on the grounds that God would not let his word be polluted with error, there is a small grouping of far-right cranks who argue that this passage is, unlike the rest of the Bible, inauthentic. The, uh, always interesting source Conservapedia has it:

"Historians and scholars agree that the story of Jesus and the woman caught in adultery is not authentic and was added decades later to the Gospel of John by scribes. The story was almost certainly added for the purpose of Democrat ideology: if no one who has sinned should cast the first stone, then the message is that no one should punish or even criticize sinners. It is also clear from the writing style that this story was added later."

It is most curious, surely, that the very same people who have defended the literal accuracy of the Bible, even to the extent of claiming the world is 6000 years old, are suddenly astute textual critics when it comes to this passage? How overwhelmingly threatening it must be, to be the sole portion distressing enough to move these arch-conservatives away from the doctrine of biblical inerrancy.

2.

The reason why the strange conservatives at Conservapedia are keen to disavow this, and only this passage is that it proposes, more or less explicitly, that because we all share in the same sinful nature, none of us has the right to punish another. Such a perspective, however impractical it may be, is a conceptual threat to all systems of authority, laws, hierarchy, and ultimately even to organised society. Nonetheless, I think it's one of the best wishes anyone has ever made.

The two oldest functions of government are criminal punishment and defense of territory. This last category might even be seen as a special case of punishment—deterrence through the use of incentives. It's often said that the state is defined by a monopoly on violence; well, the most fundamental form of that violence for the state is punishment. This story of a woman, her accusers, and God become flesh cuts against the very heart of government, conventional morality and capitalism. It is, in the purest, most glorious, and sadly most impractical sense, anarchist.

The same radical message appears in many places, but few as eloquent as "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" almost two thousand years later—but here it comes with a twist.

3.

In 1895, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor for "gross indecency with another man". He spent much of his sentence in Reading Gaol.

While at Reading Gaol he watched, appalled, as Charles Thomas Wooldridge was executed for the crime of slitting his wife's throat. Oscar Wilde was a humanitarian, an anarchist, a socialist, and a man who never softened to the world's cruelties. The idea of executing anyone was truly indecent to him, and he saw the hypocrisy of a violent society punishing violence.

After being released from prison he wrote "The Ballad of Reading Gaol."

4.

"The Ballad of Reading Gaol" is a poem, and therefore its content cannot be distilled into a list of "points". As Harold Bloom once said, the meaning of a poem could only be another poem. Yet there are clear themes which, however superficial it may be to do so, we can grab and isolate.

Where "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" differs from the story in John of the woman taken in adultery is that it proposes two reasons why punishment is fundamentally indecent. These reasons are in tension with each other, but not, I think, ultimately contradictory.

The first reason is that we are all fundamentally sinful in nature, so whoever performs the punishment is implicitly claiming to be fundamentally different from the punished in a way which just isn't true. This reasoning can be found in the story of the woman taken in adultery.

The second reason it gives isn't so obviously present in that biblical story. People are noble and beautiful, and whatever their flaws, don't deserve the dehumanisation, agony and humiliation that comes with punishment, at least as it is practiced in our society.

Describing the prisoners coming out after the morning of the hanging:

"And down the iron stair we tramped,

Each from his separate Hell.

Out into God's sweet air we went,

But not in wonted way,

For this man's face was white with fear,

And that man's face was grey,

And I never saw sad men who looked

So wistfully at the day.I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every careless cloud that passed

In happy freedom by."Or:

"They hanged him as a beast is hanged:

They did not even toll

A reguiem that might have brought

Rest to his startled soul,

But hurriedly they took him out,

And hid him in a hole."The passages where he describes the mourning of the prisoners for Woolridge before and after he dies are beautiful. The contrast between the men's shabby surrounds and the glory of their souls as they keep a vigil on Woolridge's behalf rends us:

"The Warders with their shoes of felt

Crept by each padlocked door,

And peeped and saw, with eyes of awe,

Gray figures on the floor,

And wondered why men knelt to pray

Who never prayed before.All through the night we knelt and prayed,

Mad mourners of a corse!"5.

It is possible to believe in both bits of reasoning. People are too beautiful and important to be brutalized, and too fallen to administer punishment without being hypocrites. They're not logically inconsistent, and I don't think they're aesthetically or emotionally inconsistent either. Just like a sufficiently skilled art work can contain moments of appalling ugliness alongside tremendous beauty without those "cancelling out", so too are people woven through with glory and horror. Too beautiful to be judged, and too ugly to judge something as glorious as a human.

6.

I am speculating here, but I wonder if there isn't something erotic or romantic in Wilde's outlook on Woolridge:

"And I knew that he was standing up

In the black dock's dreadful pen,

And that never would I see his face

In God's sweet world again.

Like two doomed ships that pass in storm

We had crossed each other's way:

But we made no sign, we said no word,

We had no word to say;

For we did not meet in the holy night,

But in the shameful day."Now, this is further stepping into the realm of pure speculation, but I wonder if that romantically charged perspective on Woolridge wasn't a path by which Wilde humanized him—saw past the horrific thing he'd done? Romantic and erotic energies have this power—to randomly connect us with, and make us sympathizers for, people we would otherwise despise, or at least try not to think about. This is a side of the erotic we don't often consider. We often conceive of eroticism as turning people into objects in our mind, but what about its capacity to make us sympathizers? Sometimes this power takes on a sinister or at least ambivalent aspect—like the people who fantasize about serial killers and court them in prison. Sometimes it is exalted in literature, as in Romeo and Juliet: Would a rose by any other name not—etc. etc.

7.

Obviously, a conservative will find much to disagree with in the poem, but "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" is an uncomfortable read, whatever your political orientation. I'm all for mercy, but as someone who thinks women have historically had a rough deal, I wasn't comfortable with Wilde's seemingly blithe dismissal of Woolridge's murder of his wife:

"Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!""Well sure, he brutally murdered his wife, but in a funny sort of way, doesn't every man kill his wife?" To which the answer is no. There is a very important sense in which the vast majority of men don't kill their wives—the literal sense. Is Wilde playing with words here to minimize a gross act of violence against a woman?

Perhaps. But there's also a sense in which Wilde's sentiment can be read not as minimization of what Woolridge did, but maximization of the emotional violence inherent in a certain sort of marriage. In this regard, this stanza might be read not as an apologia for Woolridge, but as a biting critique of patriarchal marriage. I'm not fully comfortable with this defense of Wilde, but we shouldn't feel comfortable about art.

To fully draw out the critical power of the poem, we must remember that there are four victims in it. The first is Woolridge; the second is Wilde and the prisoners collectively; the third is the collective warders, doctors, and reverends of the prison who are brutalized by what they do; and the fourth, and most gravely wronged of all, is Laura Ellen/Nell Woolridge, murdered by Thomas Woolridge. Having recognized the victims, we then need to consider the possibility that simply because they are human, not a single one of them deserved what happened to them.

The passage also has to be read alongside Oscar Wilde's own life. Wilde was aware of the sour face of love. Love sent him to prison and ruined his health and his reputation.

8.

Because I like to make up words, let's call generalized opposition to punishment antipoenaism, from "poena" which is Latin for "punishment" and "anti" which is Latin for "anti". Could antipoenaism ever be viable? Is antipoenaism the sort of idea which depends for its interest on whether it is, or ever will be, viable?

No. Antipoenaism is pretty obviously not viable with the world the way it is—some people need incentives not to do bad things. However, it could be viable in a future where we have the technological capacity to restrain the violent without removing their liberty (see Iain Banks' concept of the slap drone) or to cure the violent of their violent tendencies.

But I think antipoenaism is an idea that holds power even in a world where it is not feasible, and should hold that power to shock and shame us all. Jesus' provocation, "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone", holds our imaginations even now. We need a compass that points us towards utopia, even if we can't make it there, and even if it can't be real—you won't see the world as it is without crazy dreams of what it could be.

9.

It's very interesting that the greatest piece of work by Wilde is "The Ballad of Reading Gaol." Wilde was an aesthete, holding that art should be for its own sake—the sake of beauty—and not to serve pedagogic, political or moral purposes. How weird then that his best and most passionate work brims with moral significance and feeling. The chronic ironist driven by circumstances to express real passion is a potent thing (happens all the time on Twitter). I wonder—and this is pure speculation—if Wilde's aesthete sensibilities weren't like a shell to contain his powerful moral sense, which perhaps he feared might be, in today's language, "cringe". When the physical, emotional, and moral torture he had experienced finally burst through that qlippah, his best work emerged.

10.

I don't know if Wilde was, in any overall sense, a good person, I haven't studied his life closely, and even if I had, I am no judge of souls. But it is unbearable to think of what happened to the spirit, at once both kind and soaring, present in this poem. Fuck you to those that valorize the sort of society that did that to Wilde.