Why Conservatism Failed: can we build a living tradition?

And other highlights of my week on the net

Why Conservatism Failed

A striking essay, ending with a rhetorical inversion of the Benedict option even if it shares the same antecedent reasoning:

Pity about taking insurrectionist Josh Hawley seriously but that’s in another, less good article.

A living tradition teaches its participants what it means to be good (a good farmer, a good policeman, a good violinist), aligning their own desires with what sustains the tradition. These virtues aren’t merely moral ideas: They are materially and socially rewarded, and their opposing vices are punished. As time goes by, a conversation within the tradition emerges about how best to achieve its purposes, whether to change its practices or adopt new ones, how to honor what has come before while embracing the best of new developments. But this link to the past is also a link to the future: To put in the years of effort and loyalty required to master a tradition, one has to believe that the institution will continue to live on and reward its disciples, changing in some of its particulars but steadfast in the pursuit of its ends.

The digital era has ushered in a further phase of the technological destruction of tradition. Whereas some kinds of automation create new demand for higher-skilled work, digital automation based on even rudimentary forms of artificial intelligence can instead increase demand for low-skill work pushing buttons. Training on the collective efforts of thousands of years of culture, machine-learning algorithms aim to supplant human performance for classification, writing, drawing, coding, driving, making music, and a host of other practices. While the best humans may always outperform computers, these technologies knock out the bottom rungs of skilled practice that allow for the development of mastery in the first place.

The increased power to simulate human culture goes alongside the increasing availability, searchability, and profitability of “intellectual property” (the detritus of past popular culture), such that continued production of new culture and art has become optional. The incentives for investors skew more every year towards the marketing, exploitation, and further development (aided by deepfake technology) of the old over the discovery of the new. For instance, while the advent of mass media in the last century weakened older musical cultures by undermining the need to make music within the home, it also produced wave after wave of new popular music forms: jazz, country, rock, hip-hop, electronica, and so on. But since the rise of instantly accessible, algorithmically recommended digital music, a strange quietude has settled upon the whole field. This combination of stasis, decadence, and simulation characterizes human culture after tradition …

Realizing what time it is, that we are living after tradition, isn’t a counsel of despair. Those who look to build a human future have been freed from a rearguard defense of tradition to take up the path of the guerrilla, the upstart, the nomad. We can bid farewell with fondness to the modern defenders of tradition. But we must heed the words of the Lord: “Let the dead bury their dead.” Come with me if you want to live.

Branko Milanovic: Does the UN still exist?

Independently of the great powers, he can try to bring the warring sides to the table. He can set himself in Geneva, indicate the date at which he wants the ‘interested parties’ to send their delegates, and wait. If some do not show up, or ignore him, at least we shall know who wants to pursue the war, and who does not. He is the only non-state actor in the world with this kind of moral authority. Technically, the world has entrusted him with the task of preserving peace—or at least with the attempt to preserve peace. He seems to have singularly failed.

It is not however only Guterres’ fault. The origins of the recent decline of the UN go back 30 years to the end of the cold war. Three factors have made the current UN possibly worse than even the defunct League of Nations.

The first is that after the end of the cold war the United States, finding itself in the position of hyperpower, did not want to be trammelled by any unnecessary global rules. … After the end of the cold war, the US and its allies attacked five countries on four continents without UN authorisation: Panama, Serbia, Afghanistan, Iraq (the second war) and Libya. France and the United Kingdom, also veto-wielding members of the Security Council, participated in most of these violations of the UN Charter, even if France refused to go to war against Iraq. And Russia attacked Georgia and Ukraine (the latter twice). Thus these four permanent members broke the charter eight times. Among the permanent members, only China did not do so.

The second reason for the decline of the UN and international organisation is ideological. Helped by the proliferation of non-governmental organisations (and false NGOs), the new ideologues broadened the mission of the UN to many subsidiary issues. Many of these new mandates are utterly meaningless. I was asked to advise on Sustainable Development Goal number ten, reduction of inequality. I did not do so. I thought it made no sense, was impossible to monitor and consisted of pious wishes, many mutually contradictory.

The third, related reason is financial. As the mandate of the UN, the World Bank and other international institutions was broadened to include practically everything imaginable, it became obvious that the resources provided by governments were insufficient. Here NGOs met billionaires and private-sector donors. In a series of actions unthinkable when the UN was created, private interests simply infiltrated themselves into organisations created by states and began to dictate the new agenda. I saw this first-hand in the World Bank research department, when the Gates Foundation and other donors suddenly began to decide on priorities and to implement them. Perhaps their objectives as such were praiseworthy, but they should have gone about realising them independently. … Researchers or country economists in institutions such as the World Bank spent most of their time chasing private donors. Being good at fundraising gave them a power base within the institution. Thus, instead of being good researchers or good country economists, they became managers of funds who then hired outside researchers to do their primary jobs. The institutional knowledge which existed was dissipated.

This is how the entire UN system went into decline and we ended up in a position where the head of the only international institution ever created by humankind whose role is preservation of world peace has become a spectator—with as much influence on matters of war and peace as any other of the 7.7 billion denizens of our planet.

French philosophers: Noam is not impressed

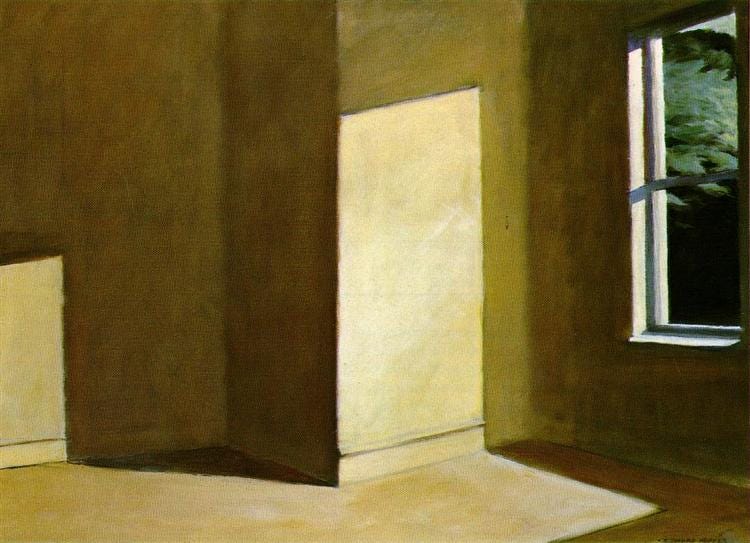

The Waning Years of Edward Hopper

A wonderful, if melancholy essay:

The picture we now call Stairway was very uncharacteristic for him, and not just because it was on wood panel instead of canvas. It gives us the view from midway down a staircase in a narrow front hallway. At the bottom is a doorway that opens onto a shadowy landscape ending in dark hills silhouetted against a blue sky. Hopper made this painting during a difficult time of depression, illness, and surgeries.

Once again it’s a memory picture—the staircase and doorway are the ones still to be found at his boyhood home in Nyack. It’s also sets down an imagined moment of supernatural power, because Hopper told Jo it was inspired by “a repeated dream of levitation, sailing downstairs & out thru door.” Yet, however it is that dreams and memory have blended here, it was to arrive at what may be a bleak premonition, a downward passage into twilight.

If Russia breaks the nuclear taboo

A weird article addressed to Vladimir Putin, rather than the reader. But on the off-chance he’s reading this, it would be churlish not to reproduce it. Moreover, it suggests that most of the stuff you read about the nukes option is shallow, and (paradoxical as it may seem) out of its depth. This piece confirms my own suspicion that WWI should be looming more prominently in our minds as a precedent than WWII.

If Washington believed that it needed to avoid giving Moscow any justification for even larger nuclear strikes, and thus keep the war as limited as possible, might the first use of nuclear weapons since 1945 generate a less dramatic chain of effects than we often assume?

The breaking of the taboo on nuclear use would still be consequential. Diplomatically, the international response to Russia would be furious and nearly utterly unanimous. The strains that have been appearing in Russia’s relationships with China and India could become chasms. …

The costs on the ground for Ukrainian soldiers and civilians could be horrendous, even though it is unclear what Russia would stand to gain militarily from causing that harm. That might give Kyiv, which is currently making the case for more hardware after this week’s bombardment, a compelling case for seeking forceful military intervention from the US and its allies. Social media, at least in the West, would be flooded with determination to make Moscow pay for its nuclear malfeasance.

Yet were Putin to make this terrible decision, the Biden administration might still have strong incentives to restrict Western involvement in the war. Such restraint might dismantle some of the all-or-nothing hypotheticals about the use of nuclear weapons which have helped sustain the taboo. That could be the necessary price for averting a globally catastrophic escalation.

Fascinating exploration of Clarence Thomas’s grim views and from whence they came

At least for those of us who knew nothing about them.

Alito argues that the Second Amendment can be enforced, over and above state law, because of the due-process clause. Thomas roots his justification in the privileges-or-immunities clause, and in its backstory of slavery and abolition. Not only does that free Thomas from Alito’s white frontiersmen of yore but it also allows him to conjure the history of Black slaves arming themselves against their masters, and of Black freedmen protecting their families during Jim Crow. In his concurring opinion in McDonald v. Chicago (2010), a landmark guns case, he concludes with this resonant image:

One man [in 1919] recalled the night during his childhood when his father stood armed at a jail until morning to ward off lynchers. . . . The experience left him with a sense, “not ‘of powerlessness, but of the “possibilities of salvation” ’ ” that came from standing up to intimidation.

Thomas tells some of this history in Bruen. He dedicates a paragraph to the horror Chief Justice Roger Taney expressed—in the infamous Dred Scott decision declaring that Black people, enslaved or free, were not citizens of the United States—at the prospect of Black citizens having the right “to keep and carry arms wherever they went.” Mocked and misunderstood on Twitter, the paragraph reprises a longer story, which Thomas narrates in McDonald, of how terrified whites were of Black slave revolts in antebellum America. Citing the work of Herbert Aptheker, the Communist author of a pioneering history of slave rebellions, Thomas notes that white fears of Black revolt would be “difficult to overstate.”

If there is any rational basis to the Court’s claim that people have the right to carry guns because they fear violence at the hands of a generalized other, it is in Thomas’s account of Black arms and Black history. Of the four pro-gun opinions in Bruen, Thomas’s is the only one in which we find an empirical example of a people’s justifiable need for armed self-defense in the face of violent enemies and government indifference. “Seeing that government was inadequately protecting them” under Jim Crow, he writes, Black people took up arms “to defend themselves” against white terrorists. The only history that can make sense of the Court’s position on guns, in other words, is that of race war.

In his second year on the Court, Thomas said that he was “proudly and unapologetically irrelevant and anachronistic.” Almost thirty years later, he has become what conservatives of every era seek to be: anachronistic and relevant.

Under Thomas’s aegis, the Court now assumes a society of extraordinary violence and minimal liberty, with no hope of the state being able to provide security to its citizens. In his Bruen concurrence, Alito extends Thomas’s history of Reconstruction to all modern America: “Many people face a serious risk of lethal violence when they venture outside their homes.” Like the Black citizens of Reconstruction, he argues, few of us should expect the police to protect us. “The police cannot disarm every person who acquires a gun for use in criminal activity,” Alito writes, “nor can they provide bodyguard protection for [New York] State’s nearly 20 million residents.”

Inside the Thatcher Larp: Lanchester on Liz Truss

LARPing — live-action role-playing — seems to be making its way out of the intellectual dark web and into the mainstream as well it might. Kayfabe can’t be far behind.

The fact is that the influence of Boris Johnson, even before and after he was leader, has wrecked the Tory Party as a serious instrument of government. Under him, it became a condition of Parliamentary Membership that MPs pretend to believe a falsehood: that Brexit does not involve serious costs and trade-offs, losses as well as gains. In their refusal to endorse that falsehood, most of the sensible Tories were driven out of the party. The ensuing talent crisis led to the selection of Truss. The succession of May, Johnson and Truss to the prime ministership resembles one of those tragic but horribly memorable failed suicide attempts, in which the sufferer shoots themself in the head but fails to die. The Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget may be remembered as the day the Tory Party finally got the job done.

Richard Rorty as prophet

I didn’t find this an especially good article, but I was struck by Rorty’s prophecy and agreed with his comments on patriotism:

The American philosopher Richard Rorty died in 2007, but in 2016 he achieved a different kind of celebrity for having foreseen the election of Donald Trump. In a book called Achieving Our Country, published in 1998, he had written that increasing inequality and the immiseration of the working class as a result of globalisation would lead “the nonsuburban electorate” to “start looking for a strongman to vote for – someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots… All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.”

One of the best essays, “Does Being an American Give One a Moral Identity?” is a call for unashamed patriotism as an essential condition for political effectiveness:

“If one lives under a dictatorship, it is a bad thing to let one’s citizenship contribute to forming one’s moral identity. If one lives in a functioning constitutional democracy, I would argue, it is an unequivocally good thing. It amounts to being idealistic about one’s country, something citizens of a democracy ought to be. To abandon such idealism amounts to opting out, to becoming an ironic spectator of the nation rather than a participant in its political life.” …

“There is no reason for us to deny that our country has been racist, sexist, homophobic, imperialist, and all the rest of it,” he continues. “But there is every reason to remember that it has also been capable of reforming itself, over and over again… The historical memories of those successes ought to be enough to make it possible for us to incorporate our American citizenship into our moral identities.”

By contrast, Rorty believed that the fragmentation of identities advocated by multiculturalism is politically harmful: “Teaching [both black and white children] that the two groups have separate cultural identities does no good at all. Whatever pride such teaching may inspire in black children is offset by the suggestion that their culture is not that of their white schoolmates: that they have no share in the mythic America imagined by the Founders and by Emerson and Whitman, the America partially realised by Lincoln and by King.

“That mythic America is a great country, and the insecure and divided actual America is a pretty good one… But, by proclaiming the myth a fraud, multiculturalism cuts the ground from under its own feet, quickly devolving into anti-Americanism, into the idea that ‘the dominant culture’ of America, that of the WASPs, is so inherently oppressive that it would be better for its victims to turn their backs on the country, rather than claiming a share in its history and future.”