Who railed most against colonialism in the 18th century? The father of conservatism, that's who!

And other great things I've been finding lately

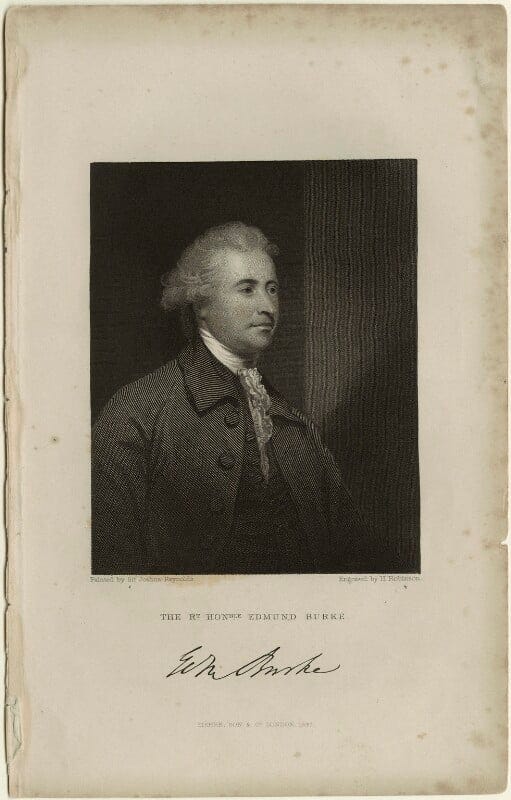

Edmund Burke: father of conservatism and founding critic of colonial oppression

Fine essay from crossover journal Compact. (I’ve always liked Burke!)

In addition to opposing revolutionary change, Burke was his era’s leading critic of colonial oppression. … Burke was alone in asking how traditional British liberties could be reconciled with “that vast, heterogeneous, intricate Mass of Interests, which at this day forms the Body of the British Power.” … These issues were neglected in 18th- and 19th-century British liberal thought. But Burke took seriously problems others ignored.

Burke not only understood the complexity of the empire, he also expressed sustained and deep reservations about it—whether in India, Ireland, or America. Here again, he was an exception. … No thinker or statesman of the 18th or 19th century expressed anything like the indignation that Burke did against the injustices, cruelty, greed, and moral sclerosis of the empire. Similarly, no thinker matched Burke’s clarity and depth in recognizing that the empire had already become an alibi for a narrow assertion of power. This, even as the empire’s only warrant was its potential to serve as a means of humble, and thus moral, engagement with strangers.

He saw through the abusive distortions of civilizational hierarchies, racial superiority, and assumptions of cultural impoverishment by which British power justified its expansionism and avarice in India and elsewhere. …None of the well-known liberals or socialists of the 19th century expressed anything like Burke’s indignation and searching critique of the empire. The British Empire and its principal early instrument, the East India Company, certainly had their critics. But no such critic would have, as Burke did, pressed that criticism by calling into question the very possibility of “drawing up an indictment against a whole people.” … None would have sensed, as Burke did, that in the distant and often exotic spectacle of the empire, there lurked an intimate internal threat: “In order to prove that the Americans have no right to their liberties, we are every day endeavoring to subvert the maxims which preserve the whole spirit of our own.” And certainly none had the moral courage to express, as Burke did to his constituents in Bristol … “I confess to you freely, that the sufferings and distresses of the people of America in this cruel war, have at times affected me more deeply than I can express. … Yet the Americans are utter strangers to me.”

By the second half of the 19th century … historian J.R. Seeley commented, “We seem, as it were, to have conquered and peopled half the world in a fit of absence of mind.” Burke’s writings and parliamentary career are a conspicuous and impressive exception to this tradition of neglect, presumption, and absent-mindedness. …

It is an enduring tribute to Burke, the man and the thinker, that his sympathy and ire and ultimately his political thought, are anchored in thinking through and feeling with tactile intensity specific episodes, replete with proper nouns, imagined habitation of real but distant places, and an engagement with vital traditions of those who were often complete strangers. This is what Raymond Williams meant by his “style of thinking,” and it is essential to understanding Burke’s views on the empire. He was a rare and capacious political iconoclast, whose sympathies were always attentive to the concrete. So far from complacently ratifying present realities, he was always attentive to injustices committed in the name of his country.

If you’re in London, maybe I’ll see you there.

Burke: the first conservative. And the last

And it doesn’t rain, it pours. For Edmund Burke anyway. Here’s another excellent piece on him with a simple and powerful point to make.

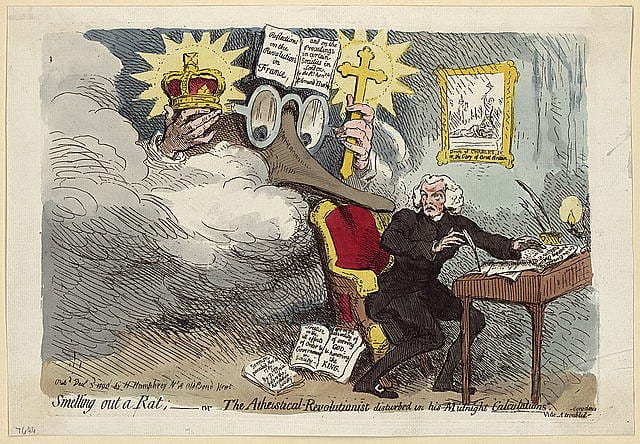

t is difficult to find much in common between Burke’s thought and the positions taken by modern conservatives of all stripes. Burke insisted that all change must be measured, necessary, and organic, building on the past instead of sweeping it away. In economic matters, modern conservatives have embraced the ideology of ‘move fast and break things.’ The conservative attitude to history is likewise instructive. Although certainly very far from being an anti-imperialist, Burke nonetheless recognized that India had its own history that, just like any other state, conditioned how it ought to be governed. He railed against British administrators who were tearing up this history. Today, many conservatives deride academics looking to undo those acts of historical vandalism and excavate pre-colonial histories and defend European empires on grounds of the economic development that they supposedly brought to their colonies, exactly the kind of argument Burke most despised: he might have seen in them the equivalent of the “sophisters, economists and calculators” that he decries in Reflections on the Revolution in France, the people who rip up beautiful old things and replace them with cold rationalism and base financial motives.

So how has modern conservatism ended up so far from Burkean principles while lauding him as their forefather? We can find an answer by comparing Burke with one of his near-contemporaries: Thomas Malthus. It has been said of Malthus that what he wrote about the mechanics of population growth was entirely true more or less until the moment at which he wrote it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, first published in 1798 and revised frequently until the last edition in 1826, he claimed that population growth expanded geometrically while cultivation expanded arithmetically, with the result that in time, the yield of the land falls far short of the demands of the human beings who lived off it. In fact, as A. E. Wrigley has shown, this was indeed the case in pre-industrial economies, where land had to be used to produce both agricultural goods and raw materials for production: textile fibers, straw and skins, and above all, wood for fuel. Trying to grow food at a pace that could keep up with population growth would mean sacrificing industrial production, with negative consequences for wages. Yet, although he did not know it, at the exact time at which Malthus wrote, Britain was breaking out of this population trap, largely through coal, a fuel that produced much greater energy for negligible land use compared to wood. Malthus’s ideas were thus invalidated at the exact moment of writing by the rise of fossil fuels.

Modern conservatism’s divergence from Burke has a similar source: industrial capitalism. It would be meaningless to speak of Burke’s “views on capitalism,” because the vocabulary of capitalism was not yet part of political language: his was still the era of what István Hont called “commercial society.” He was devoted to the cause of private property when this was associated with the rule of law and social stability rather than free exchange. He strongly favored commerce at a time when commerce was primarily understood not as synonymous with private enterprise but as a vehicle of national enrichment and a means of softening men’s manners. At the end of his life, he wrote approvingly of the “desire for accumulation,” but he thought of this accumulation in terms of individual luxury, not in its capitalist sense as a means of reinvestment for the sake of further expansion. In other words, while he was supportive of the individual ingredients of what we now call capitalism, the concept itself was beyond his horizon.

Later thinkers, however, would recognize in capitalism a force that operates like a revolution. Not just Marx and Engels, at once somber and invigorated in their observation that “all that is solid melts into air”; also Max Weber and, later, Joseph Schumpeter, who observed a “process of industrial mutation … that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in.” Capitalism is, in other words, a state of permanent revolution.

Thus, it only became clear after Burke’s own lifetime that the economic system whose foundations – private property, commerce, enlightened self-interest – he had endorsed was also fundamentally opposed to his other great political aim of opposing radical, instantaneous political and social change. This is not a contradiction with which Burke himself had to grapple, but it has posed a problem for those who have come after him. It is notable that, for the most part, the only people since Burke who have really advocated his ideas have ended up, like G. K. Chesterton, arguing for dramatic changes in the distribution and nature of property that would effectively abolish capitalism. Chesterton’s eclectic philosophy of ‘distributism’ was consciously put forward as an alternative to both capitalism and socialism: in essence, he chose conservatism over property, and as a result, he looks like a radical. Others, such as Russell Kirk, only maintained their Burkean flavor by refusing to engage with economics.

Brad Delong’s speculations about humanity

I agree with them all, but what would I know? I wasn’t there.

The history of human evolution is still extraordinarily blurred. Moreover, in my view, very, very, very little of “EvoPsych” results are going to durably replicate. Whatever I would teach about human evolution before 50,000 years or so would, I think, probably be wrong.

Nevertheless, it is very important. So let me set out 10 theses. These are all debatable and disputable. But I think they are worth keeping in mind as likely (ha!) results of our evolutionary history, and as important underpinnings of the economic history of the past 50,000 years:

We are all very very very close cousins. The overwhelming proportion of all of our ancestry comes from one roughly-1000 person or so group 70,000 years ago. Small admixtures from other human groups that were then roaming the world were then added to this mix.

We were human long before 70,000 years ago. People from 10 or 20 times further in the past would in all likelihood be able to fit into our society. Homo ergaster, homo erectus, homo heidelbergensis, homo neanderthalis, homo denisovo, the Red Deer Cave people, and us homo sapiens—and maybe homo floresiensis—are all, in a very real sense, us.

We are cultural-learning intelligences, coevolved biologically and culturally to build up a huge component of our nature-manipulation and group-organization toolkits from observing others of our species, and thus learning the accumulated cultural patterns of past ages.

We are, overwhelmingly, collectively an anthology intelligence: smart not because each of us is smart, but because we can and do learn from, teach, and communicate with others at a furious rate.

We are also a time-binding anthology intelligence: not just us around here who are now thinking, but also our predecessors thinking in the past. That is what gives us our smarts, and allows us to survive.

Since the invention of writing 5000 years ago, the time-binding-ness of our anthology-intelligence nature has been amped up by a full order of magnitude. Our knowledge from the past is not just embedded in present-day cultural patterns, but is also via direct communication from them to us, as we take durable squiggles and from them spin-up and run on our wetware sub-Turing instantiations of the human minds that made the squiggles.

Our intelligence on an individual level is quite limited. We find it very hard to think except in terms of narratives: those narratives usually taking the form of cause and effect, of journeys forward through space, and of sin and retribution, nemesis and hubris. Thoughts that do not fall into those patterns are very hard for us to have, and very very hard for us to communicate to others.

Thus we should not expect our anthology intelligence to get things right. It can get things right in an awesome and mindbending way. But large groups of people can also get things very very wrong and persist in error to a remarkable degree.

Given how incompetent most of us must be in most of the work that our culture has the knowledge to have somebody do, our prosperity—nay, our survival—depends on establishing a cooperative division of labor. We both divide labor and also induce ourselves to cooperate by being primed to form and reinforce social bonds based not on grooming each other to remove parasites (as other monkeys do), and not by mock-mounting each other in para-reproductive activity (as canids do), but rather via forming gift-exchange relationships.

With the invention of money, all of a sudden each of our individual social gift-exchange networks changes from having to be a long-term close-relationship network (limited only to our close kin, our immediate neighbors, and our good friends—and not all of those). All of a sudden our potential division of labor expands to encompass every single other human in the world. This has powerful consequences for us as an anthology intelligence devoted to organizing ourselves and manipulating nature.

Thanks to Robert Manne for sending this to me.

Interview with Jewish philosopher Susan Neiman

Thanks to a friend for pointing me to this article.

Out of centuries of Jewish suffering have come two contrasting philosophical impulses. One focuses on the need for the Jewish people to protect themselves against inevitable attacks. It is supported by the biblical verses that urge Jews to remember the Amalekites, the tribe who once killed their ancestors. It is epitomised by the nationalism of Benjamin Netanyahu.

The second emphasises Jews’ responsibility to other oppressed peoples. This was the tradition Susan Neiman imbibed as a child in 1960s Georgia. She attended an Atlanta synagogue whose rabbi supported Martin Luther King. When she was three, it was bombed, most likely by white supremacists. She recited Passover verses with her mother, remembering those that urged Jews not to oppress strangers because they were once “strangers in the land of Egypt”. “That was the central experience of growing up — if you’re a Jew, you care about social justice and the civil rights movement.”

Now an outspoken philosopher, Neiman wants to reclaim Jewish universalism as a radical act. Israel’s war with Hamas has pushed the world to pick sides. “People have, differently in so many places across the world, become so tribalist. I hate the words pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian: they make it look as if we’re talking about a football match. I’m pro-peace.” She has the advantage of being able to invoke Albert Einstein. For 23 years, she has led the Einstein Forum in Potsdam, Germany, a research institute based at his one-time summer home. “Einstein was a total universalist Jew . . . We do care about his politics and his biography because that’s why he became a cultural icon. The second half of his life, he spent more time as a public intellectual than he did working on physics.” Einstein became convinced of the need for a Jewish national home, but he feared the cost if it came without peace. “Should we be unable to find a way to honest co-operation and honest pacts with the Arabs, then we have learned absolutely nothing from our 2,000 years of suffering and will deserve our fate,” he warned in 1929. Today Neiman echoes Einstein’s concerns. “[Netanyahu’s] policies are creating anger and frustration all over the world, they will rebound on Jews, see Dagestan [where an antisemitic mob stormed an airport].” The “carpet bombing . . . of Gaza is not in Israeli interests, even if you just care about Jewish lives.” She strives to see the mistreatment of Jews and non-Jews through the same eyes. “Discrimination and oppression of any group of people on the basis of their ethnic heritage is racism.” She condemns Hamas’s “pogrom” against Israeli Jews and the ensuing “pogroms” against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank. Yet a strong universalist commitment faces a difficult context. In 1948, Einstein, Hannah Arendt and other leading Jewish figures wrote to the New York Times, criticising a future Israeli prime minister’s party as “fascist”. By contrast, “calling the Israeli far right fascist today would not just bring accusations of antisemitism, it would carry a professional death sentence,” says Neiman. To many Germans, criticism of Israel clashes with the paramount importance given to remembering the Holocaust. To many Jews today, universalism itself feels hollow, when parts of the left have shown little compassion for Jews’ own suffering. “I’m scared about rising antisemitism,” says Neiman. “But I don’t think the way to solve the problem is to become more anti-Muslim. That is one direction that people are going in, particularly in Germany.”

From a subscriber and friend.

Here you see the very famous Renee Fleming teaching a student how to make an aria into a spectacle of self-indulgence. What Fleming insists on is luxuriously decadent - she makes a defect a point of pride. A pedagogical flaw is made a curriculum goal. The casualty is objectivity, and ultimately the art form. And all this as a result of the misplaced concern about “relatability”.

Inserting the subject into the curriculum has whipped round universities like a firestorm - it’s seen in the positive light of making the curriculum more egalitarian and friendly. Yet people need to walk, and to walk they need friction, and if they don’t get friction from art and learning, they will get it from demagogues and charlatans.

Richard Fiedler interviews Richard Flanagan

A really marvellous interview.

Cool poem, cool clock

And the poem. By Simon Armitage.

Poetry

In Wells Cathedral there’s this ancient clock,

three parts time machine, one part zodiac.

Every fifteen minutes, knights on horseback

circle and joust, and for six hundred yearsthe same poor sucker riding counterways

has copped it full in the face with a lance.

To one side, some weird looking guy in a frock

back-heels a bell. Thus the quarter is struck.It’s empty in here, mostly. There’s no God

to speak of — some bishops have said as much —

and five quid buys a person a new watch.

But even at night with the great doors lockedchimes sing out, and the sap who was knocked dead

comes cornering home wearing a new head.

Can science bring peace?

Michael Polanyi’s slightly crazed but thrilling speculations

I came upon a typescript of the lecture below given as the cold war was gearing up in 1946. With the wisdom of hindsight it’s wildly unrealistic. It displays what I call the impatience of the intellectual — the idea that by dint of insight the world will somehow be dragged along. At the same time I found it thrilling. A generous vision. Polanyi was a friend of Hayek’s and about to head off to the inaugural meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society the next year. He would drift away from it after 8 years.

Still Hayek and Polanyi shared a belief in the indispensability of the market. A belief that has been dramatically vindicated by all that’s followed. And yet Hayek’s vision was so dire and so driven by a kind of asymmetric moral panic. The market had to be saved from the slippery slope of creeping socialism (to say nothing of galloping mixed metaphors). But neither the people nor their government needed to be saved from creeping capitalism. As John Gray wrote, even when he was a fan of Hayek, the market emerges morally naked in Hayek’s vision. How different, how much more balanced, how much more generous is Polanyi’s vision.

From "The Listener", 25th April. 1946.

When I was a boy and preparing to become a scientist, I used to cherish great hopes for a new world organized by science. At that time, about forty years ago, I was living in Budapest. I was a great reader of Mr. Wells' novels. I devoured them almost as they came from the press in England. They made me impatient with traditional statesmanship, and I firmly determined to follow Mr. Wells in sweeping aside all this gimcrack world - as he thought it was - putting in its place a new world run on scientific lines. However, two great wars and a number of revocations have taught me to look upon human affairs in a different light. I still remain grateful to Mr. Wells for his bold inspiration, and I share his enthusiasm for radical reform - as I share that of his modern successors, such as Professor Bernal - but I no longer believe, as they do, that the decisive problems of our world can be solved by applying the methods of science.

Our troubles today are political and not technical. After all, if all we wanted was scientific planning, we could have had that through Hitler. Had Hitler been allowed to conquer the planet, the Germans would certainly have planned the resources of the world quite scientifically. And even now, if world planning were our paramount need, we could just sit back and wait for someone to conquer the world by atomic force. For there is no doubt that any future atomic dictatorship of the world would be scientifically planned to the last button. Yet the prospect of world dictatorship does not fill us with hope but with dismay. So, you see, it is not true to say that planning is what we desire above all. And this brings us to the real problem of our time, the principal starting point of which is at least fairly simple and pretty well recognized.

Nations armed with modern weapons are so dangerous to one another that they cannot continue to live together on this planet as independent states. As a result, the present political organization of the world threatens to collapse. It is even now heading towards a clash, which would inevitably lead straight to the establishment of a world dictatorship. We all know that our task is to prevent this, and the only way is to establish world control through the free cooperation of states. We must radically revise the political organization of mankind and establish a democratic international authority with supreme control over all armed power.

And we have to do this without delay. It is useless to say that the task is too big, for we have no acceptable choice. So, let us look at our task and see where to begin. A free government can only be set up by groups that sufficiently trust each other. Mr. Churchill could safely allow Mr. Atlee to overthrow him because he knew that upon taking power, Mr. Atlee would not order him to be shot. Two rival groups can continue to sustain a system of free government as long as they mutually trust each other to observe the constitution of the country. A free control of world power could be established straight away if – but only if – the nations of the world would sufficiently trust each other to observe the future constitution of world government. Every plan for the pooling of atomic power turns on this very difficulty at some point or another. If these plans fail from the start today, it's because nations dare not place their freedom and their very existence in the hands of a machinery of power which they fear might be captured.

The essential condition for a free world government is, therefore, to establish the necessary confidence between nations all over the planet, and the crucial question is on what grounds such confidence can be based. This is a decisive problem. Suppose we consider two nations inhabiting opposite sides of the globe and speaking different languages. They may have few direct contacts; in fact, only just enough to realize that they form a potential menace to each other. If they are to trust each other in spite of this, the reason must lie in some universal belief concerning all nations, that they are subject to certain moral obligations and that people can on the whole be relied on to observe these obligations. Otherwise, there is no reason that I can see why millions of men and women in one country should trust millions of unknown men and women in another country. For if man were essentially rapacious and ready to steal, lie, and kill unless the police kept him under constraint, then each nation would have to expect any other nation to take the first possible opportunity to break the constitution of world government and try to capture absolute power over the planet. And so long as suspicion of this kind is general, world government remains impossible, and world dictatorship approaches inevitably.

Here lies the challenge of our time. Our task, it would seem, is to gain general acceptance for certain beliefs about the nature of man and make these the basis of a new free world government. You may think this a strangely abstract way of approaching the problems of world politics. But let me just show what it would mean. We might start with a declaration of the Duties of Man: of his duty to respect the truth and to keep his promises. We should declare these obligations equally valid both between individuals and groups. We should add justice, equity, and general decency to the list of man's moral obligations, and so go on to compile a complete code of moral behavior. This might constitute our 'Declaration of the Duties of Man'. I believe that we should find that all the essential rights of man follow clearly from recognition of his moral obligations. For such recognition implies the demand that man be left free to act according to his own conscience. And it implies likewise certain political demands. For in order to fulfill his moral duties, man must have protection and support by free institutions. But our declaration would mean little, and our political demands would remain unattainable, unless we first achieve an important change of outlook.

The principal obstacle to our program lies in fact today in the widespread acceptance of a certain philosophy which contradicts it. This philosophy, which has many forms and branches, regards man as a bundle of appetites restrained only by social discipline. In one way or another, this philosophy tends to reduce - or tries to reduce - the moral aspirations of man to some form of material desire. It tries to debunk the spiritual endeavors of man by exposing glaringly, and with a false emphasis, the material conditions to which they are subject. It reduces love, which is essentially unselfishness, to sex, which is essentially selfish. It makes conscience, which is the rock of fearlessness, appear to be the product of fear. It identifies justice, which springs from our will to do right, with envy, which is a temptation to the contrary. It makes us regard freedom, which is at the root of all social aspirations of man as a mere ideological product of capitalism. It supplies us with a bag of intellectual tricks by the help of which any youngster of fourteen can explain away with a sense of superior wisdom all moral manifestations from the conversion of St. Paul down to the Battle of Britain. There is no interpretation of history in art, politics, science, law, religion - so absurd that it will not be accepted uncritically today as long as it is couched in terms of 'complexes' or 'social needs' or some other similar reach-me-down theories.

We must undertake to sweep away this whole way of thinking. We need a new enlightenment to reassert the spiritual life of man should be reinterpreted in spiritual terms. Such a movement would release the significant moral forces of our time, which today are led astray by the false and degrading theories of man's nature. It should redeem all the patriotic devotion that has been corrupted today into fascism. Moreover, it should set free, above all, the immense craving for brotherhood and social justice, which is harnessed today to the engines of class war. If only we could persuade good men to believe again in goodness, and generous men to trust once more in the power of generous sentiments, a peaceful world would arise even today.

Here, I believe, is the point where doctrinal religion will play its part. The religions of the Bible serve as a great source of moral certitude. Christian theology and Christian worship are penetrating guides, striking a reasonable balance between man's physical desires and his spiritual obligations.

Yet, I do not think that the future recognition of moral reality as the basis of our lives needs to be achieved, or is even likely to be achieved, through a general reversion to the Church. For the spirit of man is most vitally revealed today in the great social movements and creative activities of our age. It is embodied in our aspirations for justice and peace, which are higher and more insistent than those of any time before us. It thrives in the integrity of our scientists and scholars and in the incomparable force of our pictorial arts. Once the bearers of this spirit fully recognize the danger to freedom in our days and are resolute that they must both have and uphold freedom, they will secure recognition once more of the true nature of man.

It is in this recognition of man's moral nature that men will find the mutual confidence needed to establish a free order of the world. I would predict that, in the long run, this will bring men back to the Christian faith and the Christian Churches. Modern men will find their way back to God through solving the problem of social freedom. They will discover, more and more, that the foundations of freedom are akin to the foundations of religion.

Hi Nicholas,

We spoke briefly after your Kilkenomics Show The People vs The Elite, you mentioned that you are working on some videos and that I should email you to get more detail. I don't have your email (and can be a little slow at thinking on my feet).

Please email me the details on the videos etc.

brmrjm@gmail.com

I mentioned that I'm a member of the DiEM25, Yanis Varoufakis's political movement and recently worked on the movement's policy regarding developing Democratic Workplaces as the centrepiece in rejuvinating democracy. Part of the framework we are looking to develop around public and private organizations includes local Citizens Assemblies playing a leading role in oversight. I'd like to share our policy with you as having watched you in a couple of the Kilkenomics shows I know you'll be brutally honest with any fedback.

Thank you,

John