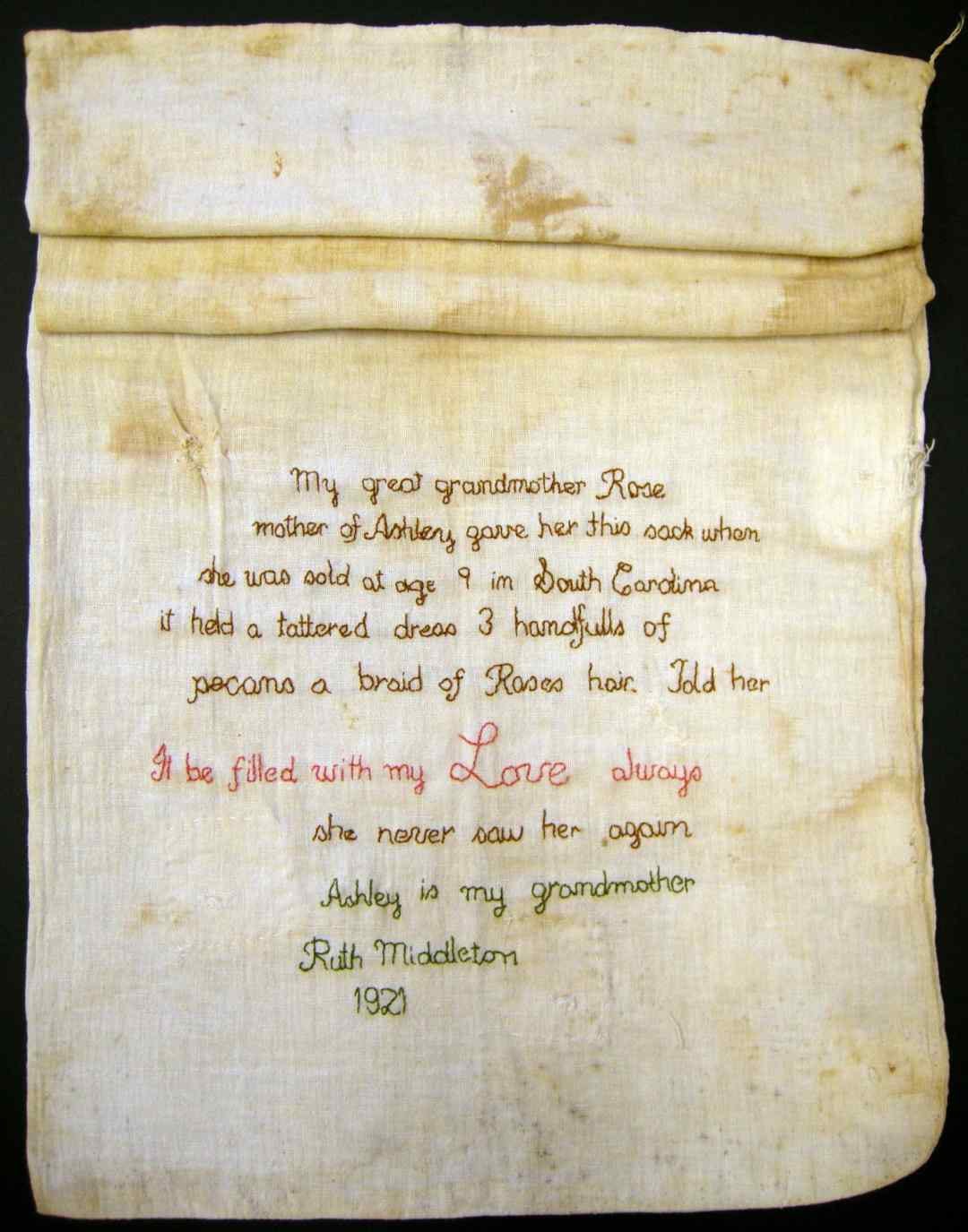

When they’re selling your 9 year old daughter …

What do you do when your nine year old daughter is being sold and you’ll never see her again? You give her a sack. If you can’t access the FT, where I found the story on the button below, you can read about it on Wikipedia.

Doubling giving in Australia: it isn’t that hard

In this chat with Sam Rosevear, the Executive Director, Policy, Government Relations and Research of Philanthropy Australia we discuss the plan he’s been working on to double donations to charity in Australia by the end of the decade. That’s an additional $13 billion per year! And as you’ll see from our discussion it shouldn't be that hard to do. It shouldn't cost government much because most of the action involves a few nudges. If you'd like to access the audio file, it's here:

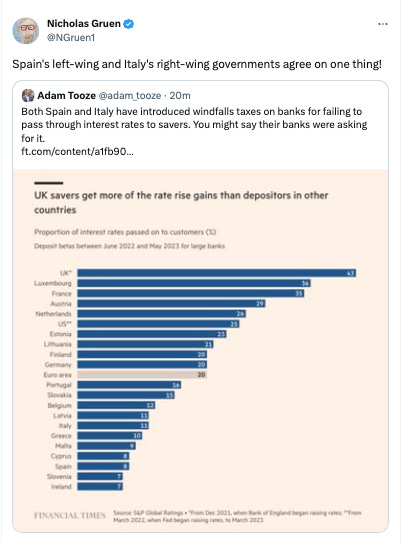

Twitter links on this Substack

In case you hadn’t noticed, even though Elon withdrew Substack’s access to Twitter’s API, when you see a tweet in my newsletters, it’s a graphical image of the tweet which is linked to the original tweet — so there’s essentially no change for readers. (Well … except that they won’t be able to forget every time they click on one of the tweets below, I’ve lavished another 15 seconds of my life on their user experience. This is attributable to the mission statement of this substack which is “We aim to leverage our unique skills and attributes appropriately and sustainably to deliver a world class user experience”.

?

Hayek and Hitler’s chief legal apologist

OK, that headline is a bit of a beat-up. But it’s true. Carl Schmidt, whom Hayek described as Hitler’s chief apologist didn’t like democracy because it just produced a free for all for pressure groups.

In 1920s Germany, Schmitt observed that the laws adopted by the Reichstag (the lower house of the Weimar parliament) often catered to the interests of narrow economic groups rather than those of the public at large. …

Schmitt pointed out a legal reason why special interests were able to influence lawmaking in this manner. In his view, it was because the Reichstag was able to adopt two different kinds of laws: Laws that are general and abstract in character and laws that discriminate between societal groups, making some people better off at the expense of others. Thus, he highlighted the Reichstag’s large amount of discretion to favor certain interest groups. It seems that Schmitt’s main motivation for doing so was to question the legitimacy of the political system of the Weimar Republic. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, he did not go on to further promote generality in lawmaking.

Hayek argued that Schmitt’s observations from Weimar Germany were not only accurate but indicative of a larger problem that concerned all Western-style democracies. He emphasized that modern parliaments are typically charged with making both kinds of laws identified by Schmitt. Because of this, Hayek referred to modern parliaments as “unlimited” democratic institutions.

Hayek didn’t much like democracy either. It’s certainly a clear and present danger to anything people might vote against. So he wrote a model constitution in which people might vote, but they couldn’t do too much harm. They couldn’t do too much of anything much. Hayek’s model constitution involved separating governance from law-making with two governing chambers. The lower Governmental Assembly would have functions similar to the executive branch in our system. It would be elected by the people and engage in the usual argy-bargy and coalition building of party politics. But those receiving direct government support, like pensioners, the disabled and unemployed and government employees would be disenfranchised. Letting them vote for politicians who might solicit their vote with a promise of pay rises was “hardly a reasonable arrangement”.

And the Governmental Assembly must govern consistently with laws made in the Legislative Assembly. The Legislative Assembly’s lawmaking was to “serve the formation and preservation of an abstract order … but not the achievement of particular concrete purposes, and finally to exclude all provisions intended or known to affect principally particular identifiable individuals and groups”.

Ronald Hamowy who is a major Hayek scholar and fanboy finds these constraints on the Legislative Assembly “stunning” in their implications. He can’t understand how one legislates sensibly without concrete purposes in mind, and concludes that the scheme is both unworkable and self-contradictory in various ways. As a long line of critics both sympathetic and otherwise have pointed out, Hayek’s scheme is marked by the very utopian rationalism he deplores elsewhere. One of Hayek’s preoccupations was his abiding fear that taxing the rich a higher proportion of their income than the poor was a slippery slope that enabled the poor to use their greater numbers to prey on the rich. His principle of non-discrimination achieved this but, as Harnowy pointed out, it permitted military or any other non-discriminatory kind of conscription, including temporary – say two year – enslavement.

Jerry Seinfeld on awards

A great line in Annie Hall is when Alvie says to Annie something like “All they do in California is give away awards. Adolf Hitler, best fascist dictator.” Anyway, you may have seen this speech by Jerry Seinfeld, but, watching it perhaps for the third or fourth time as I remembered to place it before you for your delectation, I chuckled away. It’s very good.

Freddie Deboer on being sick of writing

No — doesn’t sound too enticing does it. I wavered as I read through the paragraphs. “These are good paragraphs”, I’d think. But what do they amount to? Oh well, that’s kind of the point of the piece. It’s four stars from me (but only three and a half from Margaret.)

As I write this, I am newly recovered from major shoulder surgery. I’m very happy to say that my condition has settled into a manageable pain that merely makes me crabby; for the first 24 or so hours after the nerve block they put in my arm wore off, the experience was genuinely harrowing. There were a few hours where my constant instinct was to reach for my phone, though I had no idea what specifically I needed to find—I felt that there had to be some information, out there, if you understand me, something to explain my condition.

The pain was so much more than what felt reasonable, some part of me believed that God must have left an equation up on a wall in Gabbatha, where if you plugged in what the doctors and nurses said to me beforehand and then keyed in the coefficient of my actually existing pain units (A-EPUs) and divided by the seemingly salient fact that it’s the year two-thousand-and-twenty-goddamn-two, the world would realize that my pain in that moment exceeded the rational, and there would be some embarrassed adjustment of the dials that left me merely sore and constipated and consumed with growing disdain toward a body that is now old in several ways that are incontrovertible and non-negotiable. Which, after several more days, is more or less where I am.

One other consequence of that surgery is that I’m forced to sleep in a sling. I don’t recommend it. I’m also forced to sleep laying on my back, and I don’t recommend that, either. The result has been that I have been up all night, stealing spare hours of sleep when and where I could. Otherwise, I think, usually about deep philosophical questions of unanswerable nature. You do that late at night, too. I’m convinced this tendency is part of our genetic endowment, as humans, as primates. In any event, one thought that has recently arrested me is this: Why does Las Vegas exist?

There is a certain path dependency to history; things seem mundane to us, because we live in a timeline in which they have existed our entire lives, and so their fundamental strangeness never assaults us. This reality has been mined to great effect by stand-up comics, when, for instance, they ask what the first person to milk a cow was thinking or why we park in a driveway but drive on a parkway. If we wish to take a darker tack, we might wonder how it is that there is bipartisan consensus on defending the murderous theocrats who run Saudi Arabia, when they would seem to be obvious targets for left and right alike. But I haven’t pondered that question recently. I have been devoting my thoughts to Las Vegas. …

I am a man with an unusual problem: I am a writer, a writer of shortform, argumentative nonfiction, and yet lately, writing the type of A-to-B-to-C essays that satisfy that format is getting harder and harder. Not harder as in more of a challenge; quite the contrary, if I felt any challenge was left in that genre for me, I would find the work more interesting. No, the problem is that after 15 years of ponderously explaining what I mean and what I don’t, my commitment to meaning is all but dead. I have never been deluded into t

hinking that my writing can make a difference in any real way, beyond perhaps briefly edifying and entertaining my readers. Fundamentally, I’m motivated by form, by image, by the desire to stretch, to develop my craft, to challenge myself, and to show off. I write to write and always have. That’s why I write so much, to make it new; that’s what I’m writing this essay, and why you will find no thesis in it. I’m tired of writing things that arrive at conclusions the reader can copy and paste. The great professional question ahead of me is: Will I in time wander so fully away from basic sense-making that no one wants to pay for my work anymore?

The oldest recorded song

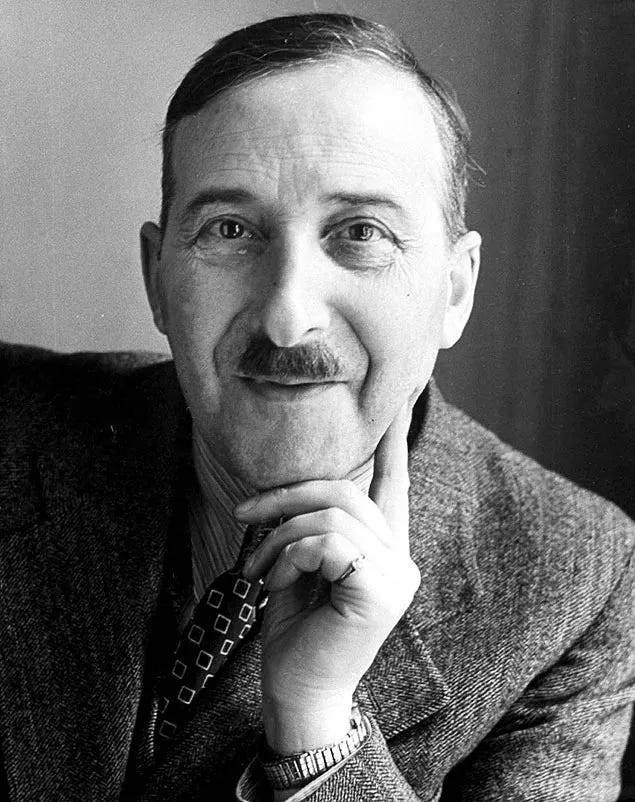

Who said anything about it being an audible record?Michael Polanyi

Also available here. If you’re so inspired by the first lecture, you can’t wait for all four, you can download them yourself here. Here’s a taste — the transcript of the introduction to the first lecture.

Ladies and gentlemen, I thank you very much. And I thank the University of California for this wonderful opportunity to address you. I'm afraid the title, which I have given to these lectures may sound strange history and hope. Yet these words refer to plain fact the history of mankind falls into two sharply divided periods, two periods of vastly different lengths. The first extends from the beginnings of human society and all through recorded history up to the French Revolution. All during these ages, men had accepted existing custom and law as the foundation of society. There had been changes and many great reforms, but never, never had the deliberate contriving of unlimited social improvement been elevated to a dominant principle. The first government to adopt this task, namely the deliberate contriving of unlimited social improvement, was that established by the French Revolution. Thus, the end of the 18th century marks the dividing line between the men's expense of essentially static societies and the brief period during which public life has become increasingly dominated by fervent expectations of a better future. Such is the history, the brief history of hope as a political and social force. Such then the justification of entitling an analysis of our age by the words history and hope. In the Western countries where it had its origin. The pursuit of these hopes achieved in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, the most humane and most free societies the world had ever seen. It has engendered an intellectual life of unprecedented range and has led to a new flowering of the arts, which rivaled the splendors of Greece and the Renaissance. It has created immense wealth, more evenly distributed than before, and nearly abolished poverty. But another stream of the same flow led to different results. It established the Soviet empire, which has spread its power and influence during the last 44 years over a major part of the globe. Thus, hardly had the march of humanity towards its new hopes got under way that it already divided mankind into two rival camps, mortally opposed to each other by the different visions of progress. Last June, the leaders of these two camps met in Vienna, and on his return, one of these, President Kennedy reported that the Soviets am using his words, that the Soviets and we have wholly different views of right and wrong, and above all, have wholly different concepts of where the world is and where it is going. Terrible situation. But here in this place, in this university, we are only concerned with understanding it. You must ask how the pursuit of progress has engendered and established over vast areas the system of ideas which mortally conflicts with the original hopes of human progress. You may tempted to think that the dominance of Soviet ideologies was imposed by sheer force, by force of arms, but this would leave unexplained how the power of communist governments originally came into existence at the centers from which it subsequently spread to other parts. It must face the fact that at these centers of power, the these centers of power were originally established by groups of deeply convinced adherents who gained influence over broad masses. And we must face also the fact that these ideas are so different from our own are still echoing around the globe and gaining followers, particularly among the more educated people. And we must acknowledge also that these converts embraced these ideas with fervent hopes for humanity and that they are dedicated to fight and suppress any opposition to them. I think the main difficulty in understanding this rise of modern totalitarian ideas lies in the habit of thinking of it in terms of a conflict between progress and reaction. This is false. The revolutions of the 20th century are not of this kind. They do not aim at restoring either the dogmas or the authorities shattered by the French Revolution. They are dogmatic and oppressive in an entirely new way, which, by a very curious process, harnesses to its purpose the great intellectual and moral passions by which free thought and popular government were first achieved in Europe and America.

The Nudgestock oath: repeat after me …

My other reason for leaving 9-5 life

Grandstanding and getting results: a story

Here’s a story that always stuck with me from Stephan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday.

One day I had an express letter from a friend in Paris, saying that an Italian lady wanted to visit me in Salzburg on important business, and could I see her at once? She called on me the very next day, and what she had to tell me was indeed shocking. Her husband, a distinguished medical doctor of humble social origin, had been educated at the expense of Matteotti. When Matteotti, leader of the Socialists, was murdered by the Fascists, world opinion, already weary with all the demands on it, had reacted once more against a single crime. All Europe had risen in indignant protest. His loyal friend the doctor had been one of the six brave men who dared to carry Matteotti’s coffin openly through the streets of Rome. Soon after that, ostracised and under threat, he had gone into exile. But the fate of Matteotti’s family weighed on his mind. In memory of his benefactor, he tried to smuggle Matteotti’s children out of Italy to safety abroad. However, in the attempt he himself had fallen foul of spies or agents provocateurs, and had been arrested. As everything calling Matteotti to mind was an embarrassment to Italy, the outcome of a trial on those grounds would not have been too bad for him, but by devious means the public prosecutor had associated his trial with another going on at the same time, and that case was concerned with an attempt to blow up Mussolini with a bomb. So this doctor, who had won the highest honours serving his country on the battlefields of the Great War, was sentenced to ten years’ hard labour.

Naturally his young wife was extremely distressed. Something, she said, must be done to overturn the sentence, which her husband could not survive. An appeal must go out to all the literary names in Europe to unite in loud protest, and she was asking me to help her. My immediate reaction was to advise her against trying to get anywhere with protests. I knew how threadbare such demonstrations had worn since the war. I did my best to explain that no country, for reasons of national pride, was going to let outsiders change the decisions of its judiciary, and that European protests in the case of Sacco and Vanzetti in America had had the opposite of the desired effect. I urged her not to do anything of that kind, pointing out that she would only make her husband’s situation worse, because Mussolini would never—indeed, could never—recommend leniency if foreign attempts were made to force his hand. But I was genuinely shocked myself, and promised to do my best. It so happened that the next week I was going to Italy, where I had friends in influential positions. Perhaps they could quietly do something to help her husband.

I approached my friends on my very first day in the country. But I could see how fear had already eaten into all minds. As soon as I mentioned the doctor’s name everyone looked awkward and said No, he was sorry, but he had no influence, it was impossible to do anything. I went from one to another. I came home feeling ashamed and afraid the man’s poor wife might think I hadn’t done all I could. Nor, as a matter of fact, had I. There was still one possibility—the direct approach. I would write to the man in whose hands the decision lay, Mussolini himself.

I did that. I sent him a perfectly honest letter. I was not, I wrote, going to begin with flattery, and I ought also to say at once that I did not know the doctor personally or the extent of what he had done. But I had seen his wife, who was certainly innocent of any crime, and she too would suffer the full rigour of the court’s sentence if her husband spent all those years in the penitentiary. I did not intend to criticise the verdict in any way, but I could well imagine that it would save the young woman’s life if her husband were allowed to serve his sentence not in the penitentiary, but on one of the island penal colonies where wives and children are allowed to live with exiles.

I took the letter, addressed it to His Excellency Benito Mussolini, and put it in the usual Salzburg postbox. Four days later I heard from the Italian Embassy in Vienna. His Excellency, said the Embassy, thanked me for my letter, said that he would do as I asked, and in addition to commuting the doctor’s sentence had taken it upon himself to shorten its length. At the same time I had a telegram from Italy confirming that the doctor, as I had asked, had been moved to a penal colony. Mussolini himself had granted my request with a single stroke of his pen, and in fact the convicted doctor soon received a full pardon. No letter in my life has ever given me so much delight and satisfaction, and if I ever think of my own literary success, it is this instance of it that I remember with especial gratitude.

Sinead sings Moorlough Shore

Your hills and dales and flowery vales That lie near the Moorlough Shore. Your vines that blow by borden's grove. Will I ever see no more Where the primrose blows And the violet grows, Where the trout and salmon play. With my line and hook delight I took To spend my youthful days. Last night I went to see my love, And to hear what she might say. To see if she'd take pity on me, Lest I might go away. She said, "I love an Irish lad, And he was my only joy, And ever since I saw his face I've loved that soldier boy." Well perhaps your soldier lad is lost Sailing over the sea of Maine. Or perhaps he is gone with some other lover, You may never see him again. Well if my Irish lad is lost, He's the one I do adore, And seven years I will wait for him By the banks of the Moorlough Shore. Farewell to Sinclaire's castle grand. Farewell to the foggy dew. Where the linen waves like bleaching silk And the falling stream runs still Near there I spent my youthful days But alas they all are gone For cruelty has banished me Far away from the Moorlough Shore.

More Sinead

And this is quite something

But then I can’t think of a pop song I think more highly of.

Frank Bongiorno on Ryan Cropp on Donald Horne

I was less of a fan than most people of Donald Horne. If you picked up one of his many books, you’d find some interesting things, but they usually left me wondering whether they were worth the trouble reading, let alone writing. Like lots of journalists, he wrote too much commentary which kind of got one’s attention but then left me at least pretty unsatisfied. Paul Kelly with whom Bongiorno compares him is similar — though oh so much more ponderous (not to mention panderous). The Lucky Country is a fine exception to all this. I remember reading its conclusion and being really impressed. Anyway, it’s a good review. Below are a few paragraphs that caught my eye as they were a surprise. I didn’t know he was one of the returning expats who left, disliked the experience and came back to do something really remarkable — like Manning Clarke, Patrick White and Arthur Boyd.

he early Horne, as painted by Cropp, is a deeply unattractive figure. The retrospective assessment of one of the friends with whom he fell out — that Horne was a “posturing prick” — seems accurate. Put bluntly, he comes across as a chancer and, at times, a bully, a master of the putdown with “weathervane critical instincts.”

Cropp allows us to see as much, but shows forbearance in offering judgement. He allows the suggestion to hang over his narrative that much of the bitterness of Horne’s persona came out of personal trauma, and it is hard not to see the decline of Horne’s family life in his remark that “the harsh fact of human existence is that there are always clouds on the horizon.” He read voraciously, but the intellectual shallowness and derivative nature of most of what he had to say before the late 1950s are striking. And he could be brutal in his dealings with others, especially with pen in hand and press at the ready.

He was also good at serving powerful masters, to his (and often their) advantage, while seeking to maintain the conceit that he was really an outsider gatecrashing the party. We are familiar with his kind of elite populism from our own times. Invective triumphed over argument, ritualised scepticism over evidence, the too-clever-by-half smart-alec over the searcher for truth.

All of that might have been forgivable in a student journalist or politician; it is less so in a man in his late twenties spouting nonsense about economic planning and rising totalitarianism among Canberra politicians and bureaucrats. It is among the ironies of Horne’s career that he barracked so hard in the 1940s and 1950s for the political and policy mediocrity that he would later condemn in his most famous writing. …

We don’t normally think of Horne as one of the Australian postwar expatriates, presumably because his time there was only four years and his fame came in Australia a decade later. But there are good reasons to think that these years mattered a great deal to his intellectual development and later thinking. He didn’t do well among the British, but nor did he think highly of them — despite having arrived with a fairly conventional middle-class Australian view of Britain as the measure of all things. It is hard not connect his later nationalism to this experience.

More contradictions of ESG

[M]oral high grounds invariably crumble — mostly due to changes in scientific knowledge, attitudes, money or politics. Even Joe Biden demanded that big oil companies in America get pumping when rising fuel prices risked three congressional elections last year. …

War of course is an extreme example of how norms shift. Cluster bombs, which are back in the news, were banned in every equity portfolio I have ever managed. But today Ukraine drops them in the name of freedom. Divestment is suddenly appeasement.

Unless investors can see the future, therefore, this problem is intractable. Likewise, ESG’s second fatal inconsistency: knowing where to stop. … Next year, for example, European firms with more than 500 employees will be forced to collect environment, social and governance data on every single company up and down their supply chains. Yes, seriously.

But wait. In 2025, these rules apply if you have a minimum of 250 staff. Then small and medium-sized companies start getting dragged into the legislation the year after. “Ciao Luca! It’s your uncle in Milano. What were your factory’s emissions last quarter — grosso modo?” Death by fatuous and incomparable data.

And somebody has to arbitrarily decide the relative weightings between “E” or “S” and “G”. This is the final inconsistency I raised in my speech: that everyone has their own view on what is good and bad. Why are huge efforts made to exclude tobacco stocks from portfolios but not food companies who overload our meals with sugar, salt and saturated fats? Beats me. Nearly half a billion people suffer from type 2 diabetes around the world. …

Or how come we hold companies to account over diversity and not work-related mental illness, which makes up half of all days lost to sick leave? Some investors care about governance, others homelessness outside their office. The result is that no one has a clue whether to punish the likes of ExxonMobil or reward it for committing to spend a billion dollars a year on green energy research. If both, in what proportion?

Meta is uber green but stinks on “S” and “G”, according to a report just published by Internews. No wonder both companies are found in sustainable funds. It’s a free for all. So much so that only 41 per cent of Europe’s most sustainable “Article 9” products even bother to target a minimum 90 per cent exposure to sustainable assets, according to Morningstar data.

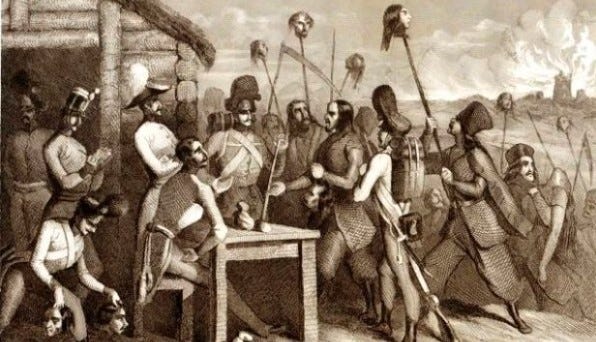

Galicia 1846

I’m listening to Revolutionary Spring, Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848-1849, which is long (perhaps a bit too long), fascinating and full of things I knew nothing about. Here’s one scene in Galicia in what is now Poland in 1846

Nowhere in pre-1848 Europe did socially motivated resentment blend with political conflict to more destructive effect than in Galicia in the Austrian Empire. On the evening of 18/19 February 1846, an extraordinary encounter took place in front of the inn at Lisia Góra, about seven kilometres north of Tarnów, one of the principal towns of western Galicia. Polish patriots had gathered to launch an insurrection against the Austrian authorities. Among them were delegates of the Polish National Government in Parisian exile, including Count Franciszek Wiesiołowski and other distinguished figures, members of the Polish landowning nobility, along with officials from their estates, and members of the Polish clergy and professional class. All were armed in preparation for an uprising whose purpose was to seize control of Galicia and the Free City of Cracow, establish a national executive council and work from there towards the restoration of an independent Polish state. But Poland was a heavily agrarian society and the conspirators understood that they would need the support of the peasantry if their enterprise were to succeed. Peasants from many nearby villages had been summoned to appear before the inn with their weapons in hand: scythes, pitchforks, flails and pickaxes. A priest by the name of Morgenstern, who was party to the plot, addressed the peasants, urging them to join forces with the Polish lords. Then Count Wiesiołowski spoke. He promised the peasants that the rewards for their participation would be generous indeed: all their feudal burdens would be lifted; there would be no further labour services; the hated Crown monopoly on salt and tobacco would be abolished. Armed with their scythes and flails, the peasants should join the march on Tarnów and help to found a new Poland.

After Wiesiołowski had finished, a village official by the name of Stelmach, who had been standing with the peasants, spoke up against Wiesiołowski, reminding the peasants of the good things the Austrian government had done for them and begging them to remain loyal to their emperor. Emboldened by this appeal, another peasant spoke up, warning the crowd that ‘if you follow the lords, they will harness you and use you just as you use your horses and oxen’. There was a pause in which everything seemed to hang in the balance. Then one of the insurgent noblemen lowered his gun and shot the peasant who had just spoken. The intention was to intimidate the gathering, but the effect was the opposite: the peasants now furiously attacked the insurgents. The landlords fired off their pistols and hunting guns but ‘in hand-to-hand fighting it was the peasants with their scythes, the terrifying weapon of the Polish rustic, who had the decisive advantage’. There were fatalities on both sides. The insurgents left forty men, most of them gravely wounded, in the hands of the peasants and the rest fled from the scene.

Some more from Revolutionary Spring:

CRACKS IN THE DAM

Little was known of Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti when he acceded to the papal throne after a hurried two-day conclave on 16 June 1846, but he profited from general relief at the death of his predecessor, the stern and reactionary Gregory XVI. The old pope had died at the age of eighty; the new man, who adopted the name Pius IX, was forty-eight years old with a warm personality, an attractive countenance and a cheerful, winning manner. Whereas Gregory had opened his reign in 1831 with a wave of violent repressions, Pius’s first act in office was a blanket amnesty to the political prisoners languishing in the jails of the Papal States.

The response took everyone, including the Pope, by surprise. When the amnesty was made known, it unleashed a wave of euphoria in the city. Crowds formed in the summer twilight, chanting ‘Viva Pio Nono!’ Contemporary witnesses speak variously of joy, delirium and intoxication. It was, one clerical observer recalled, as if a ray of divine love had suddenly descended on the town. There were extraordinary scenes on the Piazza del Quirinale, the square in front of the papal palace. Thousands of Romans converged hoping for blessing, and at around 10.30 in the evening the Pope appeared at the balcony of the palace with his hands raised in greeting, to deafening cheers and then silence as the people fell en masse to their knees to receive his blessing. ‘To describe the explosion of universal jubilation’, an eyewitness recalled, ‘is not just difficult, it is absolutely impossible. – Everyone looks up towards this most beloved sight; all cry out in choked voices, blocked, because impeded by abundant tears of tenderness.’[209] A few hours later, at around one in the morning, an even bigger crowd assembled in the square, and for the second time that night the Pope bestowed his blessing on his people.

This was papal government in a new key: charismatic and eloquent. The American journalist Margaret Fuller, to whom we owe the most evocative and insightful eyewitness accounts of Roman events, was riding with a friend on the Campagna when she happened to see the Pope on foot, taking exercise, walking quickly in ‘simple white drapery’ and accompanied only by two young priests in spotless purple: ‘all busts and engravings of him are caricatures’, she wrote; ‘it is a magnetic sweetness, a lambent light that plays over his features, and of which only great genius or a soul tender as his own would form an adequate image’.[210] And it was quickly apparent that the Pope was warming to his role, that he ‘liked to please’, as one observer put it.[211] Reformist initiatives brought further waves of adulation. There were judicial and prison reforms; a committee was appointed to consider the construction of railways (something Gregory XVI had refused to countenance); tariffs on staple grains were reduced to alleviate the social distress of the poor; plans were announced for gas lighting in the capital (another of Gregory’s pet hates); censorship restrictions were relaxed; laymen joined priests in key administrative and deliberative organs; a civil guard manned by Roman taxpayers was created to keep order in the city. On 1 October 1847, the Pope announced that Rome was in future to be ruled by two bodies: a deliberative municipal council of one hundred members, only four of whom were to be clergymen, and a senate to consist of nine members elected by the municipal council – this concession in particular was greeted with loud rejoicings: on 3 October, a great demonstration of thanks was held, attended by about 4,000 of the Civic Guard. Stirred by the rise of nationalist sentiment in the city, Pius IX even became, in January 1848, the first pope ever to pronounce the words ‘God bless Italy!’ in public.

There was something volatile in this new and intense relationship between the pope and the population of Rome. Did he really have a choice about whether to bestow his blessing when thousands of citizens gathered in the square in front of his palace in the middle of the night? Over the summer months, the clamorous expressions of popular enthusiasm for the Pope began to grate on the nerves of well-to-do citizens, who feared that they might serve as a cover for crimes against property or even for political upheavals.[212] And this was indeed the core of the problem, because the enthusiasm for Pius IX soon acquired political connotations. The cry ‘Long Live Pius IX!’ soon morphed into: ‘Long live Pius IX, king of Italy!’ and to this was soon added ‘Death to the Austrians!’, or even ‘Death to the Pope’s evil advisers!’ What if, as actually happened on the evening of Tuesday, 7 September 1847, crowds who had converged on the residence of the Tuscan legation to cheer Duke Leopold II of Tuscany, subsequently made their way to the Piedmontese legation to cheer Charles Albert, the king of Piedmont-Sardinia, and then, with their spirits fired up, marched into the Piazza Venezia, where the legation of the Austrians was situated? As the foreign overlords of Lombardy and Venetia and the conservative Catholic hegemon on the Italian peninsula, the Austrians were objects of obsessive hatred for Italian liberals, patriots and democrats of every stripe. The sight of Roman crowds chanting ‘Death to the Austrians’ and ‘Long Live Italian Unity!’ rang alarm bells in Vienna.[213] ‘The revolution has seized upon the person of Pius IX as its flag’, wrote Metternich in the summer of 1847.[214]

From Pius IX’s perspective, these were profoundly unsettling developments. There were quite narrow limits to the reforms the Pope was willing to concede. He was a moderate with a progressive reputation, but not a liberal. How could the divinely appointed monarch of what was in essence a theocracy share real power over the great affairs of state with laymen and popular assemblies? There could be no question of the Pope’s supporting a campaign of any kind against the Austrians, on whose support and regional clout his security depended. He was not immune to the patriotic emotion of his fellow Italians, but the dream of a politically united Italy was, in his eyes, a chimera and perilous trap. And as the liberals and radicals in Rome became more confident and articulate, his misgivings deepened. ‘God bless Italy!’ he cried to a crowd outside his palace on 10 January 1848. But then he added: ‘Do not ask of me that which I cannot, I must not, I wish not to do.’ ‘The Italians’, Margaret Fuller wrote in May 1847, ‘deliver themselves, with all the vivacity of their temperament, to perpetual hurras, vivas, rockets and torchlit processions. I often think how grave and sad the Pope must feel, as he sits alone and hears all this noise of expectation.’[215]

The raucous lovefest in Rome unfolded against a background of rising political tension across Europe. As the harvest failures of 1846/7 pushed up grain prices, hunger riots were reported from across Spain, Germany, Italy and France. In Prussia alone, 158 food riots – marketplace riots, attacks on stores and shops, transportation blockades – took place during April/May 1847, when prices were at their highest. There was a surge of banditry and petty crime in the Italian states, striking fear into the hearts of the middle classes. Contemporaries noted a hardening of political discourse. In France, as we have seen, the toasts and speeches given at banquets acquired a more radical edge. In the summer of 1847, the moderate journal Il Felsineo noted the influx from neighbouring Tuscany of new and ‘pernicious’ communist doctrines.[216]

Disquieted by the liberal patriotic cult around Pius IX, the Austrians reinforced their troops in the garrison city of Ferrara on the northern border of the Papal States: on 17 July 1847, the Austrian generals Nugent and d’Aspre entered the city with 800 soldiers under fluttering flags and fixed bayonets. Although the Austrians possessed longstanding treaty rights in respect of Ferrara, the reinforcement had a dramatic effect. The agitation around the Pope reached a new pitch of intensity, liberal and radical opinion throughout Italy linked the news of Austrian troop movements with (unfounded) rumours of a reactionary conspiracy to bring down Pius IX. The mood of agitation and outrage deepened. The radical Tuscan newspaper Il Popolo reported in September 1847 that the peasants of the Valdichiana, an alluvial river valley that passes through the provinces of Arezzo and Siena, were fully apprised of the situation, they talked ‘only of the Pope and of the Germans’ [i.e. the Austrians]: ‘for them the only notion is the Pope, and by this they understand, or rather replace, every other idea. The claim that if the Pope were to ask for it, they would drop everything to come and defend him against the Germans, is on everybody’s lips.’[217]

The Italian sovereigns responded to this tide of political emotion in different ways. In Tuscany, long known for the relative mildness of its governance, the Grand Duke moved closer to the reformist elites, issuing decrees easing the censorship of the press and enlarging the consultative state council. In Piedmont, King Charles Albert vacillated, surfing the wave of anti-Austrian feeling but offering, for the moment, only minimal concessions to the reformers. Impatience at the resulting deadlock pushed the moderates back towards an accommodation with the radicals: they no longer sought partial adjustments but a major recalibration of the kingdom’s administration and institutional landscape, including the demand for a constitution. In the south, Ferdinand II, king of the Two Sicilies, tried a different approach. He shuffled his ministers and offered crowd-pleasing windfalls to the poorest strata, such as the abolition of the hated duty on milled grains, while holding back on substantial reform. But unlike his Piedmontese colleague, the Bourbon Neapolitan monarch was neither willing nor able to offer himself as a plausible partisan of the national idea, which he regarded as a noxious utopia.[218]

In 1847, as the harvest crisis began to bite into the kingdom’s economy, the Neapolitan man of letters Luigi Settembrini published an anonymous clandestinely printed pamphlet bitterly attacking the monarchy and its servants. Settembrini had grown up in a milieu saturated with radical and patriotic activism. He was the son of a lawyer who had played a role in the Neapolitan revolution of 1799. During the constitutional revolution of 1820–21, seven-year-old Luigi had often accompanied his father to meetings of the Carbonari. In 1834, he had joined Mazzini’s Giovine Italia, together with an even more secretive sect called Figliuoli della Giovine Italia (Sons of Young Italy), which emulated the Illuminati and cultivated a democratic and neo-Jacobin sensibility. In the following year he secured a professorial position at the Liceo in Catanzaro, one of the four high schools of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, all the while remaining an active participant in the radical underground. Betrayed by a priest in May 1839, he was arrested and imprisoned for three years. Unable to resume his professorship after his release in 1842, he eked out a living as a private teacher. He took a sympathetic interest for a time in the arguments of Gioberti, but soon rejected them as impractical fantasies. In the summer of 1847, he wrote the swingeing attack on the Neapolitan regime for which he is best remembered today, at least in Italy.

The Protesta del Popolo delle Due Sicilie (Protest of the People of the Two Sicilies) was a searing indictment of virtually every feature of the Bourbon monarchy. The country’s government, Settembrini wrote, was ‘an enormous pyramid’, whose base was made up of ‘cops and priests’ and whose summit was the king, the ‘biggest and most disgusting worm’ in the pile (interestingly enough, Büchner and Weidig had used the same metaphor for Grand Duke Ludwig II of Hesse-Darmstadt). ‘From the usher to the minister, from the common soldier to the general, from the gendarme to the Minister of Police, from the parish priest to the king’s confessor’, every officeholder of this kingdom was ‘a ruthless and crazed despot toward those who are his subordinates, and a servile slave towards his superiors’.

For 26 years the two Sicilies have been crushed by a government whose stupidity and cruelty can hardly be described…The ministers who compose the entire government are vicious or stupid…. This is the country where the science of economics was born and where even today many distinguished men write learned treatises, and yet its administration is placed in the hands of idiots and thieves…. In a kingdom so beautiful and fertile that could nourish twice as many inhabitants as it possesses, bread often runs short, men are often found dead from starvation; grain often has to be brought from Odessa, from Egypt and from countries that are called barbarous. If you ask the ministers: Do you know how much grain there is? Do you know how much the kingdom needs? They know nothing…. All are oppressed and the source of all these evils is the government.[219]

This was strong stuff, even by the standards of an age rich in denunciatory rhetoric. Unlike the mild and oblique critiques of the northern moderates, Settembrini’s indictment left no space for negotiation or compromise (how do you negotiate with a worm?). Protesta del Popolo was a literary sensation in the kingdom and throughout the Italian peninsula. A copy of it was thrown by an enthusiast into the carriage of King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies while he was visiting Palermo.[220] A Neapolitan liberal estimated that more than 1,000 copies were in circulation on the mainland; everyone in Naples and across the provinces was talking about it. Many copies were hunted down and destroyed by police, but the precious few that escaped were ‘read by everyone, whether friends or enemies of the government’. Liberal activists and printers were arrested on suspicion of having written it or played a part in its production.[221] A French translation helped to darken the (already poor) reputation of the Neapolitan Bourbons in the eyes of continental liberal opinion. Fearing that he would be identified as the author, arrested and sentenced to death, Settembrini fled to Malta on 3 January 1848. He would return only a few weeks later, when the revolution that had broken out in Palermo reached the Neapolitan mainland.

—

By the mid 1840s, the Prussian political system, too, seemed to be living on borrowed time. This was not just a matter of rising popular expectations, but of financial necessity. Under the terms of the State Indebtedness Law of 17 January 1820, the Prussian government was prevented from raising state loans unless these could be cleared through a ‘national estates assembly’. During the 1820s and 1830s, successive Prussian finance ministers had avoided trouble by raising loans indirectly through the nominally independent Seehandlung, a state bank, and keeping overall borrowing to a minimum. But this could not continue for ever. The king, Frederick William IV, was a passionate railway enthusiast at a time when the economic, military and strategic importance of the revolution in transport technology was becoming increasingly apparent.[222] Since this was an area too important to be left to the private sector, it was clear that the Prussian state would soon have to extend its reach and face infrastructural expenditures it could not cover without raising substantial loans. And this it could only do if it convened a ‘national estates assembly’. The king was reluctant, but he had no choice: no assembly, no railway.

The ‘United Diet’ as the new composite body was called, was controversial even before it met. There was a small chorus of moderate conservative enthusiasts, but they were drowned out by the roar of liberal and radical critique. Most liberals felt that the new assembly fell far short of their legitimate expectations. ‘We asked you for bread and you gave us a stone!’ thundered the Silesian liberal Heinrich Simon in a polemical essay published – to avoid the Prussian censors – in Saxon Leipzig.[223] If the Patent was offensive to liberals, it also alarmed hard-line conservatives, who saw it opening the door to a full-blown constitutional settlement. And at the same time the announcement of the United Diet also triggered a further expansion of political expectations.

On Sunday, 11 April 1847 – a cold, grey, rainy Berlin day – a crowd of provincial delegates numbering over 600 were herded into the White Hall of the royal palace for the inaugural ceremony of the United Diet. The king’s opening speech, delivered without notes over more than half an hour, was a warning shot. The king was in no mood for compromise. ‘There is no power on earth’, he announced, ‘that can succeed in making me transform the natural relationship between prince and people…into a conventional constitutional relationship, and I will never allow a written piece of paper to come between the Lord God in Heaven and this land.’ The speech closed with a reminder that the Diet was no legislative parliament. It had been convened for a specific purpose, namely, to approve new taxes and a state loan, but its future depended upon the will and judgement of the king. Its task was emphatically not to ‘represent opinions’. He would only reconvene the Diet, he told the deputies, if he considered it ‘good and useful, and if this Diet offers me proof that I can do so without injuring the rights of the Crown’.[224]

In the event, the deliberations of the Diet were to prove the ultra-conservatives right. For the first time, Prussian liberals of every stripe found themselves performing together on the same stage. They mounted a campaign to transform the Diet into a proper legislature. If the government refused, they insisted, the Diet would not approve the government’s spending plans. The importance of this experience in a state where the press and political networks were still fragmented along regional lines can scarcely be overstated. It fired liberals with a sense of confidence and purpose; it also taught them a first lesson in the virtues of political cooperation and compromise. As one conservative ruefully observed, the liberals regularly worked ‘late into the night’ coordinating their strategy for key political debates.[225] By this means they succeeded in retaining the initiative in much chamber debate.

The conservatives, by contrast, were a shambles. Throughout much of the proceedings they seemed on the defensive, reduced to reacting to liberal proposals and provocations. As the champions of provincial diversity and local autonomy, they found it harder to work together on an ‘all-Prussian’ plane. For many conservative noblemen, their politics was inextricably bound up with their elite corporate status – this made it difficult to establish a common platform with potential allies of more humble station (Hungarian conservatives faced the same problem). Whereas the liberals could agree on certain broad principles (constitutionalism, representation, freedom of the press), the conservatives seemed worlds away from a clearly defined joint platform, beyond a vague intuition that gradual evolution on the basis of tradition was preferable to radical change.[226] The conservatives lacked leadership and were slow to form partisan factions. ‘One defeat follows another’, Leopold von Gerlach remarked on 7 May, after four weeks of sessions.[227] The liberal deputy Adolphe Crémieux noticed the same asymmetry in Paris in mid February 1848: ‘the [opposition] movement in Paris is magnificent, the camp of the conservatives is in disarray’.[228]

In purely constitutional terms, the Prussian United Diet was a nonevent. It was not permitted to transform itself into a parliamentary legislature. Before it was adjourned on 26 June 1847, it rejected the government’s request for a state loan to finance the eastern railway, declaring that it would only cooperate when the king granted it the right to meet at regular intervals. ‘In money matters’, the liberal entrepreneur and deputy David Hansemann famously quipped, ‘geniality has its limits.’ Yet in terms of political culture the United Diet was of enormous importance. Unlike its provincial predecessors, it was a public body whose proceedings were recorded and published, so that the debates in the chamber resounded across the political landscape of the kingdom. The Diet demonstrated in the most conclusive way the exhaustion of the monarch’s strategy of containment. It also signalled the imminence – the inevitability – of real constitutional change. How exactly that change would be brought about, however, remained unclear.

THE AVALANCHE

By the mid 1840s, the conflicts unfolding in the Swiss cantons had started to fuse into an all-Swiss crisis. In 1845, the Catholic government of Lucerne announced the passage of a decree readmitting the Jesuits, who were hated throughout Protestant Switzerland, and directing them to take control of the cantonal education system. To forestall possible unrest, the government detained liberal leaders, stirring further outrage and triggering waves of refugees into the neighbouring cantons. ‘It was and is unheard of in the history of our fatherland’, a liberal eyewitness declared, ‘that such a great number should have been forced to leave their homes and flee from such a small country [the canton of Lucerne] on account of their political opinions.’[229] Twice, the liberals in neighbouring Aargau mounted abortive armed raids into Lucerne. On the second occasion, in the spring of 1845, over 4,000 men marched on the city, led by the radical Bern lawyer Ulrich Ochsenbein. The liberals hoped that they would be welcomed by the population there as ‘liberators from the tyranny of the Catholic populists’.[230] But the Lucerners repulsed both raids with the assistance of allied troops drawn from the neighbouring conservative cantons of Zug, Uri and Unterwalden. The chasm between the progressive and the Catholic camps deepened. While liberals in the progressive cantons pushed through amendments to their constitutions, the Catholic cantons pulled more closely together and formed the Sonderbund, or Special League, a fully fledged military alliance with provision for a central military authority.[231]

The liberals in the federal diet responded in the following year by proposing that the Sonderbund be declared illegal under the federal constitution (whether it was or not depended on whether you viewed Switzerland as a genuine federation or simply a confederacy of quasi-independent states). In January 1847, the presidency of the Diet (Vorort) had passed to Bern, a strongly liberal canton whose government was headed by the very Ulrich Ochsenbein who had commanded the volunteer brigades in the raid on Lucerne. The Diet resolved to act against the Sonderbund and decreed the formation of a federal army. About the likely outcome there could be little doubt: the progressive cantons commanded three times the population and nine times the resources of their conservative opponents.

The war that followed lasted twenty-five days, took ninety-three lives and left 510 wounded on both sides, though it would have been much deadlier, had the federal command not pursued a policy of humane restraint.[232] The most lethal confrontation was the Battle of Gisikon in the Reuss Valley in the canton of Lucerne. The troops of the Sonderbund had dug in on elevated ground above the River Reuss and a Colonel Ziegler of the Federal Army led three successive assaults on their positions, until, after two hours of bitter fighting, the Sonderbund troops ceded their emplacements and retreated. Thirty-seven men were killed and about 100 wounded. This was not just the longest and bloodiest battle of the war, but also the last pitched battle ever to be fought by the Swiss Army and the first in world history to see the use of purpose-designed ambulances, in the form of wagons operated by nurses and volunteers from Zurich, to treat the wounded on the battlefield.

Contemporaries were in no doubt as to the significance of this conflict. For Ulrich Ochsenbein, a passionate, Protestant man of strong opinions, the raid on Lucerne was nothing less than a world-historical stand-off between Jesuitical servitude and ‘a people struggling for its mental and physical freedom’.[233] In Paris and Vienna, the Swiss crisis was seen – not least by the statesmen – as a ‘test case in the struggle between revolution and reaction in central Europe’. The Swiss troubles should not be understood in isolation, the French envoy in Berlin wrote to Guizot, but rather as one aspect of ‘the revolutionary question in general’.[234] Metternich and Guizot hoped to prevent the success of the liberal movement in Switzerland from infecting neighbouring territories and both supported the Catholic cantons, though mutual distrust prevented an armed intervention. Official press reporting in France depicted the war as a struggle in defence of suppressed cantonal and religious liberties. Prussia, too, was implicated in the Swiss upheaval. King Frederick William IV of Prussia was the sovereign of Neufchâtel, one of the cantons of the Swiss confederation. Prussia was formally neutral in the conflict, but the king’s sympathies were firmly on the side of the Sonderbund and against the liberal cantons struggling to create a new Swiss state.

There was nothing anybody could do to prevent enthusiasm for the Swiss liberals from spreading into France and south-western Germany. In the autumn and winter of 1847–8, there were toasts to ‘Swiss liberty’ by the radical speakers at French banquets. Across south Germany and the Rhineland, there were spontaneous demonstrations and open letters with lists of signatories expressing solidarity with the federal cause. Donations for the widows and orphans of fallen federal troops poured in from the German Confederation, France, Belgium and England.[235] Italian patriots arrived from Austrian-controlled Milan.

German radicals came to see the events in Switzerland as the opening chapter of the revolutions of the following year. ‘In the highlands were fired the very first shots, / In the highlands against the priests!’ sang Ferdinand von Freiligrath, radical bard of the German revolution. In Freiligrath’s poem, the Sonderbund war is an ‘avalanche of rage’ that, once in motion, rolls across Europe, from Sicily to France, Lombardy and the German states.[236] In Baden and Württemberg, volunteers – most of them radicals – signed up to fight for the liberal cause in Switzerland. Among the officers of the federal forces was the German radical Johann Philipp Becker. Born in 1809 at Frankenthal in the Palatinate, Becker had been imprisoned for his role in political agitation after the 1830 revolutions and settled in Switzerland with his wife and children in 1837. He continued to be politically active as a radical democrat, though he also made a solid living from a range of business ventures, including part-ownership of a cigar factory. He was appointed adjutant of Ochsenbein’s division of the Federal Army in the autumn of 1847 and fought bravely against the Sonderbund, acquiring military experience that would serve him well during the German revolutionary upheavals of 1848 and 1849.

European opinion distilled the Swiss crisis into a binary clash between Protestants who were also liberal and conservatives who were also Catholic. The reality, in this small but highly diverse country, was much more complex. There were Catholics and Protestants on both sides. The canton of Ticino, though Catholic, did not join the Sonderbund. Catholic and Protestant liberals alike distrusted and feared the neo-Jacobin radicals in their own religious camp. Both the commander-in-chief of the Sonderbund, General Johann Ulrich von Salis-Soglio from the Grisons, and the commander of the federal troops, General Guillaume Henri Dufour, were conservative Protestants. The officers serving on the federal side included conservative Protestants sceptical of the liberals in Bern, and the officers of the Sonderbund included individuals of liberal convictions. And on both sides officers and men believed that they were fighting for ‘liberty’ against ‘tyranny’ (no one fought under the banner of servitude!).[237] The image of a binary stand-off between progress and reaction endowed this small war with a disproportionate European resonance, building solidarities and mobilizing spirits. But it also masked a multitude of lesser conflicts that cut in different directions across the embattled cantons: town vs country, the mountains vs the lowlands, liberals vs radicals, Catholic cantonal particularists vs papalist ultramontanes, conservative vs liberal Protestants. Had the Swiss war lasted longer, these fractures might have widened, undermining the cohesion of the two parties, and the Austrians might well have mounted an armed intervention in support of the Sonderbund, tipping the balance in the other direction. European liberals and radicals saw and drew inspiration from the triumph of ‘liberty’ over ‘reaction’, but they missed the many fissures and instabilities. On this occasion, as on so many before and since, victory was a poor teacher.