When the facts change I change my ideology

And some great things I found on the internet this week

Brink Lindsey: When the facts change I change my ideology

In this episode of Uncomfortable Collisions with Reality, I chat with Brink Lindsey about his ideological trajectory — he began as an adherent of schlock philosopher Ayn Rand and has gradually transitioned towards the centre of the political spectrum via libertarianism and Hayek. (Rand regarded Hayek as poisonously, treasonously left wing. After all he saw a role for government, including in ameliorating destitution).

But Hayekian libertarianism had embarrassingly little to say about the emerging problems of our time — noticeably cultural, political and environmental degradation. So, wishing to be reality based and all, Brink sought the answers in more eclectic ways.

The conversation is built around the title of Brink's Substack, "The Permanent Problem". This was inspired by Keynes's essay "Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren”, in which Keynes sketches out the problems he expects to emerge by around the early decades of the new century. For by then, as Keynes prophesied, we'll have solved the economic problem. And that leaves us with the permanent problem — how to live agreeably and well.

If you prefer audio only, you can find it here.

Rory Stewart raises an idea dear to my heart

Thanks to friend and collaborator Nicholas Searle for pointing out that 15 minutes into his regular podcast with Alastair Campbell, Rory proposes the idea of a standing citizen assembly with the power to compel a secret ballot of a house of parliament if it’s unhappy with its previous vote.

Apparently he got the idea from a ‘very interesting’ Australian friend.

80% discount on a Compact subscription

Compact is an intriguing and ambitious attempt at a ‘crossover’ e-zine combining left and right wing responses to the world as it collapses around us — or perhaps muddles through. It has quite a few writers I don’t have much time for, but lots of writers saying interesting things. So I subscribed for a year and have been pleasantly surprised — and have extracted a number of articles in this substack. And now, as a direct response to the fact that pilgrims ate turkeys and cranberries and established Thanksgiving several hundred years ago, they’ve got a special offer on.

80% off. All you have to do is follow these instructions. “From now through Sunday evening, new readers can use discount code THANKSGIVING”

Prejudice to the effective working of government: you wouldn’t want that

Rex Patrick, stalwart of good government and transparency everywhere isn’t happy. I think he probably overstates his case, but, especially given what we’ve got used to, not by much. Thanks to Andrew Beesley for drawing my attention to it. I wonder, when he looks back what Mark Dreyfus will think of his time as Attorney General.

Secrecy is woven into the fabric of the Australian Government. There are eleven general secrecy offences in the criminal code, 295 non-disclosure duties in 102 laws that attract criminal liability, and 569 specific secrecy offences in 183 laws.

A rationalisation and a review of secrecy laws was long overdue.

But buried in this review is a bombshell. Carried out by the Attorney-General’s Department, the review report makes a key recommendation that disclosure of information that could cause a loss of trust in Government should be criminalised.

Paragraph 146 states:

“… disclosure of information that harms the effective working of Government undermines the Australian community’s trust in government and the ability of Commonwealth departments and agencies to deliver policies and programs. It is appropriate that conduct which causes or is likely to cause prejudice to the effective working of government be covered [by secrecy provisions enforceable under the criminal code]”

The national security bureaucrats’ view seems to be that secrecy is essential to ensure trust in government!

The infamous character of Sir Humphrey Appleby in the Yes Minister TV show would be so proud.

If implemented, this recommendation would raise for public servants a criminal penalty for anything embarrassing, anything that might put a question in the way of policy information or even any wrongdoing by officials to the extent that revealing such might undermine confidence in government.

Three reasons Italy has such low murder rates

Italy has among the lowest murder rates of all European countries. …

So what explains the “Italian paradox”? While I haven’t done an exhaustive study, I suspect that three main factors are involved.

First, age. Italy has the fifth oldest population in the world, after Japan, Germany and two microstates. It’s well known that nearly all violent crime is committed by men between the ages of 15 and 30, so countries in which a greater share of the population is older than 30 will tend to have lower murder rates, all else being equal. By way of example the average Italian is almost 46, whereas the average Dutch person is only 43 and the average Dane is only 42.

Second, immigration or lack thereof. Compared to most other countries in Western Europe, Italy has had relatively little non-Western immigration since the Second World War. The country remains about 92% ethnic Italian, with the remaining 8% made up of Romanians, Albanians, Slovenes, Arabs and Chinese.

This matters because non-Western immigrants to Europe, particularly those from the Middle East, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, are substantially overrepresented in violent crime. In Denmark, where we have excellent data, non-Western immigrants are convicted for violent crime at a rate 3–4 times higher than native Danes – with age and sex differences explaining only a small part of the disparity. And it’s the same story in the rest of Northern Europe.

Third, healthy drinking culture. One major correlate of violent crime across European countries is the prevalence of alcohol abuse, which tends to be higher in Eastern Europe – particularly the Baltics (as well as Ukraine and Russia). Indeed, there’s a close correspondence between the homicide rate and the death rate from alcohol abuse disorders.

Fascinating revisionism on breach of promise

I don’t know how reasonable the argument in the book reviewed below is, but it’s certainly interesting.

Simmonds is mistress of the well-turned phrase and the arresting observation. She is also a fine historian. In her elegantly written new book, Courting: An Intimate History of Love and the Law, she interrogates the strange and the familiar to illustrate love’s history in Australia and its long entanglement with law.

Her sources are “the papery remains of blighted affection,” the records of the 1000 or so cases involving alleged breaches of promises to marry that were brought before Australian courts between 1788 and 1976. … Together with this close reading of the past, Simmonds offers some broad-reaching readings of historical change. She delights in challenging established truths.

Simmonds’s litigants are not wealthy, and mostly not very respectable, for “working-class people… were the people who went to court.” As a corrective to bourgeois scholarship, she draws on their voices to argue that the rules of nineteenth-century working-class courtship were different from those of middle-class courtship. Women in paid employment were never limited to the private sphere like their middle-class employers, and “they also had more sex.” Sex before marriage was perfectly acceptable so long as marriage followed. Simmonds writes with cheerful bias that the “countervailing working-class romantic culture… was delightfully resistant to respectable mores.”

But Simmonds’s corrective goes further. American and British histories of love mark the 1890s as the period of greatest change, the time when women moved into the public sphere and capitalism moved courtship out of the home. But “Australia tells a different story,” says Simmonds. Capitalist prosperity came early to Australia, and by 1880 Australian city environments were “based more on pleasure than prohibition,” offering cost-free romantic opportunities to lovers of all classes:

Far from being a classic tale of embourgeoisement — of the working classes becoming respectable — what we see by the 1880s is the middle classes gradually taking up more expansive working-class romantic geographies. …

Simmonds’s structural analysis is compelling. Breach of promise required women to take a public stage, to stand in judgement of men, to take their own feelings seriously. The action “elevated private pain to a question of public justice,” and “put a price on the unremunerated feminine labours of love.” Its abolition marked the loss of “compensation for psychic and economic injury” and “the individualism of emotional harm.” It was not “the triumph of love over sexist tradition” but “the final chapter in a story of how love… lost many of its ethical and material foundations.”

This is a radical rewriting of legal and emotional history. It will be fascinating to see how historians currently researching these fields choose to engage with it.

Why I love Kilkenomics

I always thought it was something weird about me — that I loved Kilkenomics so much. But when we arrived, the organisers asked us to record on the WhatsApp group why we liked Kilkenomics. Turned out on listening to the segment (see above) the Kilkenomics tragic wasn’t such a rare species after all. And that was just those who were appearing on panels in the shows. I met one couple in the audience from the Northern Territory. “What brings you to Ireland” I asked them. Kilkenomics was the answer! 60 shows, pretty much all booked out, and when you’d finished you mingled with the audience who’d buttonhole you and ask why you’d said what you’d said.

Peter Turchin on the impact of AI

An important dimension in the declining social power of American workers is the evolution of the Democratic Party, which was a party of the worker class during the New Deal, but by 2000 became the party of the credentialed “ten percent”. The rival party, Republicans, primarily served the wealthy 1%. The 90% were left out in the cold. … Workers didn’t accept their immiseration meekly. There are many signs of growing popular discontent. But history teaches us that revolutions are not made by the “masses.” Popular immiseration and resulting discontent needs to be channeled against the governing regime, and this requires organization by breakaway elites, so-called “counter-elites”.

So much for history. What about the future? The rise of intelligent machines will undermine social stability in a far greater way, than previous technological shifts, because now A.I. threatens elite workers—those with advanced degrees. But highly educated people tend to acquire skills and social connections that enable them to organize effectively and challenge the existing power structures. Overproduction of youth with advanced degrees has been the main force driving revolutions from the Springtime of Nations in 1848 to the Arab Spring of 2011.

The A.I. revolution will affect many professions requiring a college degree, or higher. But the most dangerous threat to social stability in the U.S. are recent graduates with law degrees. In fact, a disproportionate share of revolutionary leaders worldwide were lawyers—Robespierre, Lenin, Castro—as well as Lincoln and Gandhi. In America, if you are not one of super-wealthy, the surest route to political office is the law degree. Yet America already overproduces lawyers. In 1970 there were 1.5 lawyers per 1000 population; by 2010 this number had increased to 4.

Too many lawyers competing for too few jobs didn’t depress all lawyer salaries uniformly. Instead, competition created two distinct classes: winners and losers. The distribution of starting salaries obtained by law school graduates has two peaks: the right one around $190k with about a quarter of reported salaries, and the left one around $60k with about half salaries, and almost no salaries in between. This “bimodal” distribution evolved from the usual (“unimodal”) one in just one decade, between 1990 and 2000. Here’s what it looked like by 2010:

[T]hose in the right peak have succeeded in getting into the pipeline to elite status. Most of those in the left bulge, on the other hand, will become failed elite aspirants, especially considering that many of them are crushed by $160k or more of debt they incurred to pay for law school.

If the outlook for most people holding new law degrees looks dire today, the development of new A.I. will make it much worse. A recent Goldman Sachs report estimates that 44% of legal work can be automated—lawyers will be the second worst-hit profession, after Office and Administrative Support. If market forces are allowed to have their way, we will create a perfect breeding ground for radical and revolutionary groups, feeding off the vast army of intelligent, ambitious, skilled young people with no employment prospects, who have nothing to lose but their crushing student loans. Many societies in the past got into this predicament. The usual outcome is a revolution or a civil war, or both.

Unless the worst fears of the doomers are realized, in the long run, undoubtedly, we will learn how to race with smart machines, rather than against them.[xvi] But in the short-medium term (say, a decade), the generative A.I. will deliver a huge destabilizing shock to our social systems. Since we can foresee the effect of ChatGPT and its ilk on potentially creating large numbers of counter-elites, in principle, we can figure out how to manage it. The problem is that I have no confidence that our current polarized, gridlocked political system is capable of adopting the policy measures needed to defuse the tensions brought about by elite overproduction and popular immiseration. I hope I am wrong; but if not, prepare for a rough ride.

The cutie in chief

Vale Max Corden

David Cameron and the wages of cynicism

On the wages of neglect and exploitation.

Whatever your take on Brexit and the unravelling of Britain’s political establishment since the 2016 referendum, it’s hard to dispute the fact that the foundations were laid well in advance. Just ask any journalist who covered the European Council’s post-summit media conferences during the years of David Cameron’s peak anti-EU belligerence. The former British prime minister’s contempt for the European project was stunning; anyone in the room would have known that this kind of rhetoric couldn’t be unwound. Ultimately, the only one who seemed surprised that his words might set the stage for what Britain is grappling with today was Cameron himself.

Here’s how the press conferences would work. The summit would break in the early hours of the morning and hundreds of journalists would rush to their home country’s briefing room to receive their quotable quotes. Interpreters would scramble; the basement’s unflappable audiovisual team would swoop into action. As twenty-eight heads of government or state took to their podiums, the biggest show in Brussels would reach its climax amid a frenzy of mostly upbeat activity.

Twenty-seven press conferences would follow a similar script. The leader would tell journalists that, yes, negotiations had been tough but middle ground had been found (the passive voice was perfect for EU leaders not wanting to lay blame or take responsibility). If a deal had ultimately been struck it had been in the name of European solidarity. The message was reliably similar: you don’t always get what you want, but it was worth the compromise.

The British press conferences were very different. It was as though Cameron had attended a meeting in a parallel universe. The unelected bureaucrats had tried to put one over on Great Britain, the prime minister would tell us. But fear not — the ever-vigilant British government had seen through the ruse and stepped in to stop another case of continental thieving. And before you had time to take it in, Cameron would move on to domestic affairs, making a point of only taking questions from British journalists and speaking straight down the camera into the houses of the British public. Then he’d skedaddle — no conciliatory statement, no acknowledgement that this political union had brought years of peace, prosperity and a sense of democratic purpose that would have been unthinkable in the Europe of the early postwar era.

Click through and watch this remarkable 1929 cinematography

By contrast: David Goodhart arguing for British leadership in the EU

I’m writing a piece on the economics of generosity. It’s point? That generosity is a public good. In fact, generosity is often so generative that it is often enlightened self-interest — enough of the public dividends of generosity return to the generous that they’re revealed to be feathering their own nest as they do their good deeds. In any event, the sheer meanness — the abusiveness of the Conservative approach to the EU — makes a great contrast to those who were arguing for a much more enlightened and self-interested bit of self-interest before the Brexit fiasco. I’ve extracted his whole article for the Times in 2014 at the end of this newsletter.

Marcia sings some great songs

Despite the extract below, the list of songs on this new album are religious or about religion, but are mostly not what I’d call ‘gospel’. But the interview is interesting. And the song she sings is one of the great popular songs written in my lifetime (in my not particularly musically astute opinion) and she sings it very finely (in my not particularly musically astute opinion).

When she hears I’m a Black woman, Hines addresses me as “girlfriend” – the universal catchcry of Black sisterhood. She began recording the album after the end of Covid lockdown measures. “It was the right time to do [the album] and it was really interesting because Covid was just kind of

over and I think, girlfriend, we needed a little bit of God.”“A little bit of God” is what she offers. The album features 11 songs, mostly church hymns with some contemporary gospel. I confess I have been listening to the record all morning, having grown up with gospel music. “I think there’s something to be said about people who praise,” says Hines. “That voice. You know what I’m saying.”

There is something so wonderfully nostalgic that comes from listening to gospel. As a non-religious person, I feel a healing and hopeful energy that transcends religion. Hines agrees. “It touches your heart,” she says. “We all have hearts, you know, whether you want to admit it or not. I think there’s a peace that comes upon you when you go into a church, because nobody fights in church, nobody. I mean, like you go to church to find peace.”

Ain’t that the truth. Whether or not God happens to reside within them, I so love the quiet peacefulness of visiting churches.

Hannah Arendt: What remains?

Thanks to Robert Manne who sent me this noting my previous publication of Arendt’s great lecture on receiving the Lessing Prize.

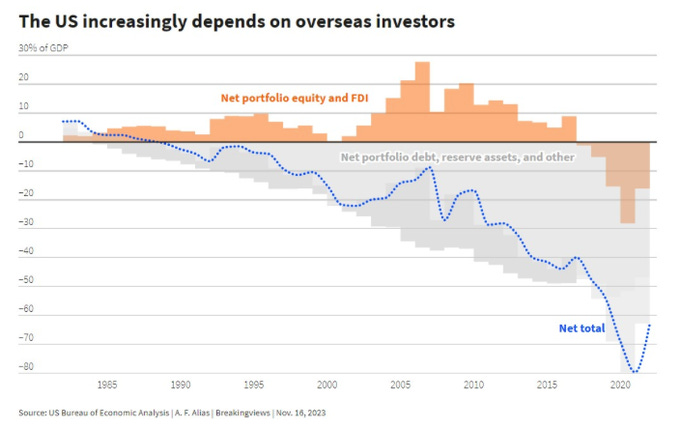

Felix Martin on the transformation of the US balance sheet and how you should respond

My friend Felix Martin with some contrarian wisdom on today’s troubled times. Ken Rogoff offers some similar ideas here.

A quarter of a century ago, then French Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine coined a new term to describe the United States: “l’hyperpuissance” – the world’s sole “hyperpower”. It was the guarantor of global security, the rule-maker for global trade, and the undisputed international hegemon. Today, the “Pax Americana” lies in tatters; free trade is a fading dream; and it is summits such as this week’s meeting between Presidents Xi Jingping and Joe Biden which set the world agenda. The days of America’s undisputed global dominance are over. Geopolitically, we live once more in a multipolar world.

Yet in international finance, the unipolar moment is more extreme than ever. The U.S. dollar remains the de facto global currency, while the United States is in a league of its own as the world’s biggest net debtor. Take the country’s net international investment position (NIIP) - the benchmark metric of a nation’s overall balance sheet, which subtracts the sum of foreign investors’ financial claims on it from its own investors’ claims abroad. In June 2023 this stood at -$18 trillion, or a deficit equivalent to 67% of U.S. economic output. That is more than double the deficit of 33% a decade earlier, and more than seven times larger than in 2007. No other economy comes close when it comes to soaking up the savings of the world. …

A less orthodox option would be to invest in emerging markets instead. Before you fall out of your chair, here are three reasons why that might work.

The first is simply that many emerging economies are also significant net creditors these days. … The second is that geopolitical fragmentation is working in many emerging economies’ favour. As the U.S. encourages manufacturers to shift supply chains away from China, hitherto less competitive alternatives from Mexico and Brazil to Vietnam and India are filling the gaps. …

Finally, there is the fact that, in the last few years, emerging market policymakers have left their advanced economy counterparts for dust. Their governments have been more fiscally orthodox and their central bankers more ahead of the curve. …These days the “Washington Consensus” of sound money and disciplined public finances is to be found not in Washington but the emerging world.

David Goodhart on British leadership within the EU

Britain’s natural role in the EU is to lead an “outer ring” of countries that want the benefits of the single market, and pooled sovereignty in many areas like trade, but do not want to join the quasi-state that the Eurozone countries are now headed towards. But for the past generation our polarised debate has prevented us thinking clearly about how to achieve that goal.

Instead we have swung between Tony Blair’s New Labour which believed we could thrive at the heart of the EU and a Tory party that has been too busy arguing about whether it wants to be in Europe at all to pursue an effective outer ring strategy. This polarisation was perfectly captured by the Clegg v Farage debates, the neo-federalist versus the rejectionist.

The greatest failure of British foreign policy of the past generation is not Iraq or Afghanistan. No, it is the fact that most of the political class in Central and Eastern Europe, and in particular Poland and the Czech Republic, actually wants to join the Euro.

There are some good reasons for this. For a start they have to join as part of the treaty they signed when they joined the EU in 2004. In the case of Poland there is also its historic reconciliation with Germany that seems to require Eurozone membership.

But what has also driven Poland in a more federalist direction is the lack of a realistic alternative in which it could be fully embedded in the European project without having to sacrifice so much of its recently regained national sovereignty. And therein lies the great British foreign policy failure.

The outer ring can be imagined in many ways but it currently does not even exist informally. The 10 “outs” not in the 18-strong Euro are merely “pre-ins” (with the exception of Britain and Denmark which both have opt-outs): the EU, increasingly, simply is the Eurozone. The European Commission even told Greece that if it left the Eurozone it would have to leave the EU too.

The EU has always accommodated different alliances of countries and even allowed some to join together to pursue specific forms of integration on their own—such as the Schengen agreement on passport-less travel.

This time, though, there is a more fundamental divide. The majority of European countries are heading towards a quasi state with a single currency, fiscal and tax policy, social policy, banking structure, with significant transfers from rich to poor countries, and elements of a common foreign policy. There will be a lot of foot-dragging along the way but that is the path. Meanwhile, a minority of countries want to remain self-governing nation states yet also wish to pool sovereignty in EU institutions where appropriate.

The only answer to this divide is an outer ring to complement the Eurozone: a porous periphery through which some countries will want to move on the way to the Eurozone core and others from that core (Greece? Italy?) may want to retreat to if Eurozone membership becomes politically unacceptable.

This is the solution to the European riddle, not just for Britain but for the rest of the union too. It would also be an opportunity to bring in to the outer ring the EFTA countries currently outside the EU like Norway, Iceland and Switzerland, and even in the medium-term Turkey, which has no desire to join a European quasi-state.

For Britain it is the obvious ‘Gesamtkonzept’, the big idea that can give some shape and grandeur to our European policy which otherwise seems like so much sniping and self-interest.

So why has Britain not been doggedly seeking partners for this strategy, especially in Scandinavia and eastern Europe, at least from the time in the mid-1990s when it was clear there was going to be a big Eurozone? Why has David Owen, the former Labour foreign secretary, been almost the only weighty figure arguing for this strategy?

One answer is that the need for a more formal outer ring was only starkly posed very recently with the Eurozone crisis of 2010 and the sudden shift towards a single economic policy for the Euro countries. It is also true that there is little agreement among the outs about what an outer ring should look like.

But, according to Owen, this failure to pursue an outer ring policy is mainly down to the failure to reach a national consensus on Europe. Much of the establishment, including the Foreign Office, has been neo-federalist, while public opinion, and most of the Conservative party, has been consistently hostile to further integration at least since the mid-1980s.

Labour was a European “player” when it came to power in 1997 but it had no interest in thinking about an outer ring, because it naively believed the country could take its place at the heart of the EU and join the Euro. According to David Owen, Blair expected to enter the Euro on the back of a Baghdad ‘bounce’.

Today the British government has friendly enough relationships with Sweden and Denmark but has made no consistent attempt to cultivate them or a broader group that might include the Poles, Czechs, Hungarians and Dutch.

Indeed in EU circles Britain is said to have “lost” Poland, despite championing its entry in 2004 and then being the only large county to open its labour market to Poles from day one. Poland has, perhaps, been condemned by geography and history to seek a path to the heart of the Eurozone at a time when Britain has been pulling in the other direction. But matters have been made worse by Britain’s stiff-necked approach to coalition-building. On freedom of movement, on energy policy and on the EU budget, Britain has been noisily arguing against what Poland perceives as its vital national interests. Picking fights with allies is not how to build a coalition.

Polish foreign minister Radek Sikorski now makes speeches attacking David Cameron for questioning the benefits of unqualified free movement. Yet this same Sikorski as a young Polish nationalist in the late 1980s used to love tweaking the noses of bien pensant Brits at north London dinner parties (I attended some of them and had my nose tweaked). The Oxford graduate was a convinced Thatcherite and yet today he can see no alternative to becoming a junior partner to Berlin. He is a walking British foreign policy disaster.

And Britain has not done much better elsewhere. No one wants to be a member of a club that Britain is leading. Sweden, for example, shares many of Britain’s positions but does not like being seen as too close to London.

The Euro crisis does, however, provide a second chance for an outer ring strategy. There are likely to be seven countries outside the Eurozone for at least 20 years and a few more will most likely be permanent outs. The outs, both temporary and permanent, are not of one mind—some like Britain would prefer to return to an EU as it was in the early 1990s, others are happy with the EU as it is—but this situation at least requires some formalisation.

As a first step David Owen has proposed that the outs—led by Britain, Poland and Sweden—create a non-Euro group (NEG) as “a constructive element of the EU that challenges the assumption that non-Euro membership is a form of second class citizenship.”

It has never been Britain’s destiny to be at the heart of the EU but equally, to be outside completely, to be merely an important trading partner, would also be a historical anomaly.

The threat of exit does give Britain some leverage over the European project in the next few years—because if it successfully left it would be a game-changing boost to anti-EU forces in other countries. That leverage should be invested in some variant of the outer ring.

If we fail in this task, all is not lost. For there is one country in Europe that is still capable of thinking strategically and realises that a future EU must be flexible enough to accommodate Britain and the other permanent outs. Like so much in modern Europe, Britain’s outer ring may end up being made in Germany.

From The Times, 2014

Thanks Jim

To-day's offering, Nicholas - worth it simply for the Hannah Arendt interview of around 60 years ago! Many thanks. Oh, and I enjoyed the bathing machines lined up on the strand at Aldeburgh in Suffolk back in the 1930s. An area I first knew in the latter 1980s.