When the constitution is torn asunder

And many, many other things you need to read and read NOW!

Two for one

Well folks, what with history having sped up and all, I ended up with more content than I thought I should ask you to digest in one day. So, if the spirit is willing, there’ll be another one tomorrow!

You’re welcome.

Extra-constitutionality and Civic Sede Vacantism

Some people would call this argument radical. I’d say it has ‘imaginative vigour’. AKA: it doesn’t pull its punches. It follows through on a line of thinking. It is not politically radical until one decides what actions, if any, one takes on it. And the author Josh Marshall is not calling for any blood in the streets. He’s offering clarity of thought. With the usual caveats — i.e. the right to be persuaded I’m wrong — he seems right to me.

For almost a year I’ve been thinking through an idea... a form of civic sede vacantism. The reference is... to a strain of hyper-traditionalist Catholic thought which held... that none of Vatican II canons or the successive Popes counted because they were heretical... The key is their idea that the papal throne was empty. That’s the meaning of the Latin phrase, sede vacante.

My interest... grew out of my belief that civic democrats in the US have far too great an essentialism about the law and constitutional jurisprudence... It breeds a kind of fatalism and passivity.

In Trump v. United States... the Supreme Court claimed that Presidents have wide immunity from criminal law after they leave office. For many... this was an ‘everything changed’ moment... But now that’s the law, as so many people I know put it. Only it’s not. This isn’t a decision I disagree with. It’s simply wrong... The authors of the Constitution knew precisely how to confer immunity... They did it with Congress.

Now, as a practical matter we... comply with [these decisions]. The alternative is the abyss. But it’s a practical decision.

Now, here is the point where people ask... You’re saying this isn’t actually the law or the Constitution. But we still comply with it as though it were. What’s the point?... I think it does matter. We are living in a moment in which the system of legal, interpretive legitimacy has fatally broken down... Now it’s no longer operating at all. That throne is empty of anything that commands our allegiance... If the Supreme Court decides... that people born on American soil are not citizens... It won’t mean that the plain... meaning of the 14th Amendment changed. It will mean that the people who currently hold power have opted to rule outside the Constitution.

If the court says the President can... dismantle Department after Department... because [of] some kind of indivisible sovereign power cribbed from an inter-war German far-right ideologue, that won’t make it so. It will remind us that we are... grappling with a renegade, corrupt court... as well as a renegade and lawless president.

Again, you may say this is some weird semantic distinction that has no real meaning... But some semantic distinctions are important... The language we use... shapes how we understand the present reality and what possibilities we can see within it. We need to... grapple with the corruption rather than living within it.

As I said, I’ve been mulling this for months. But I decided to write it out after I heard an account of a townhall meeting with Maryland’s senators... A key part of their message was we need to let the legal cases play out. This is precisely the wrong message.

As we’ve seen... the courts — even in their current degraded state — play a key, important role. But they’re just a tool in a larger contest... There are good odds the final decisions... will themselves be corrupt and unconstitutional... So it’s not that courts don’t matter. They do. A lot. But we shouldn’t be thinking we’re going to wait on what any court decides... I reject the assumption. At the margins there are questions about what’s constitutional. We’re way past the margins... We’re waiting to see if the courts will follow the Constitution. And there’s a good chance they won’t.

We’re embarked on a vast battle over the future of the American Republic... in which the executive and much of the judiciary is acting outside the constitutional order. That battle is fundamentally over public opinion... The courts are a tool. Federalism is a big, big tool... But it’s really about public opinion. And that means it’s about politics. The American people will decide this. Waiting on the courts is just a basic misunderstanding of the whole situation.

The eclipse of the other

The psychological parallels between fascism and anarcho-libertarianism

Adam Smith built his whole theory of humanity on the diad between self and other.

We’re born as infantile blobs of ego and then gradually

We figure out others exist — particularly those on whom we depend for our existence.

We crave the approval of our care-giver (wondering whether no approval = no food = no me). And so ‘the other’ comes into our consciousness.

But the other is never as distinct as our own self. We can virtually never escape what Iris Murdoch called “the fat relentless ego”.

But we try according to our lights in our private lives. And we have to if we’re to be part of some larger social whole.

All forms of human governance beyond simple brute alpha-male force are built on a reversal of this psychology. The art of good governance is for the ruler to be thinking more about the other (the ruled) ahead of themselves. Which is a difficult trick to pull off because for the ruler as much as anyone else, that fat ego is as relentless as ever. This is one reason we honour the good leader. We’re grateful to them.

A mature democracy has a robust expectation of this psychology operating at the level of government at least as an ideal. And one barrier that Donald Trump’s sociopathy has magisterially brushed aside is the expectation that such values are at least paid lip-service to. He’s flouted this expectation all the way to the top.

Way back in the 2015 Republican primaries, even though Trump thinks nothing of reneging on promises when it suits him, he still refused to commit to supporting the successful nominee if it wasn’t him. Likewise during the debates against Hilary Clinton, when accused of evading tax, he spoke as if he was in a pub arguing with other private individuals. “That makes me smart.”

Likewise on the occasion of a recent plane crash, four hours after putting out an official statement expressing condolences, offered some half-arsed private commentary on social media.

The airplane was on a perfect and routine line of approach to the airport. The helicopter was going straight at the airplane for an extended period. It is a CLEAR NIGHT, the lights on the plane were blazing," Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform. "Why didn’t the helicopter go up or down, or turn? Why didn’t the control tower tell the helicopter what to do instead of asking if they saw the plane. This is a bad situation that looks like it should have been prevented. NOT GOOD!!!

No-one would have too many problems with this as a bit of private bullshitting in a bar. But most of us understand that it lacks certain basic requirements of good speech from a public official. There’s a huge gulf between this and Boris Johnson’s sociopathy — which, in its continuing dissembling, continued paying the tribute vice pays to virtue.

This is the eclipse of ‘the other’ as the frame through which the ruler sees the world. The ruler sees no ‘other’ — any more than is necessary to have an audience.

These are the thoughts that came to mind as I read this from John Ganz:

[T]he fascist ego and the radical, “anarchist” libertarian ego are identical on a structural level, that is to say, they are the same form of subjectivity in different moments. That is not to say that every single fascist is a libertarian or vice versa, or that they exactly have the same psychological origin story. What they both share is a fundamental misrecognition of the Other: the other is just a thing, some material for exploitation or domination. As such, they cannot understand and fundamentally distrust anything that doesn’t openly declare a relation between self and others that is non-exploitative or based on non-domination. They both cannot recognize any universal interest, only the wars and temporary alliances of particular interests, be they individuals, nations, or races. To put it somewhat differently, their universal is just the particular, it becomes the Absolute. Libertarians like to say, “Well, we hate the state, while fascists worship the state.” But this is merely a semantic game. The state as fascists understand it is not the state as liberals and socialists understand it: as the sphere where pluralistic, particular interests are reconciled for the general good. They have no such ideal. They view the state instead as a crude vehicle or weapon for the movement or the race. And neither have any conception of “citizenship” as conventionally understood, a set of inalienable rights: citizenship is a mutable and revocable thing like employment, based on the notion of one’s productive contribution to the whole.

From this piece — though it doesn’t say all that much more than the quoted para:

Patrimonialism: the descent

I didn’t fancy an article in The Atlantic titled “One word that describes Trump”. Sounded a bit cute to me — and linkbaity. But there you go. Sometimes your first instincts are wrong. And my second instinct was to assume that Jonathan Rauch wouldn’t waste my time. Which he didn’t.

What exactly is Donald Trump doing?

Since taking office, he has reduced his administration's effectiveness by appointing to essential agencies people who lack the skills and temperaments to do their jobs. His mass firings have emptied the civil service of many of its most capable employees. He has defied laws that he could just as easily have followed (for instance, refusing to notify Congress 30 days before firing inspectors general)... He has disregarded the plain language of statutes, court rulings, and the Constitution, setting up confrontations with the courts that he is likely to lose. Few of his orders have gone through a policy-development process that helps ensure they won't fail or backfire—thus ensuring that many will...

In foreign affairs, he has antagonized Denmark, Canada, and Panama; renamed the Gulf of Mexico the "Gulf of America"; and unveiled a Gaz-a-Lago plan...

Even those who expected the worst from his reelection (I among them) expected more rationality. Today, it is clear that what has happened since January 20 is not just a change of administration but a change of regime—a change, that is, in our system of government. But a change to what?...

There is an answer, and it is not classic authoritarianism—nor is it autocracy, oligarchy, or monarchy. Trump is installing what scholars call patrimonialism. Understanding patrimonialism is essential to defeating it. In particular, it has a fatal weakness that Democrats and Trump's other opponents should make their primary and relentless line of attack...

Weber wondered how the leaders of states derive legitimacy, the claim to rule rightfully. He thought it boiled down to two choices. One is rational legal bureaucracy (or 'bureaucratic proceduralism'), a system in which legitimacy is bestowed by institutions following certain rules and norms. That is the American system we all took for granted until January 20. Presidents, federal officials, and military inductees swear an oath to the Constitution, not to a person...

The other source of legitimacy is more ancient, more common, and more intuitive—'the default form of rule in the premodern world,' Hanson and Kopstein write. 'The state was little more than the extended "household" of the ruler; it did not exist as a separate entity.' Weber called this system 'patrimonialism' because rulers claimed to be the symbolic father of the people—the state's personification and protector. Exactly that idea was implied in Trump's own chilling declaration: 'He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.'...

Patrimonialism is less a form of government than a style of governing. It is not defined by institutions or rules; rather, it can infect all forms of government by replacing impersonal, formal lines of authority with personalized, informal ones. Based on individual loyalty and connections, and on rewarding friends and punishing enemies (real or perceived), it can be found not just in states but also among tribes, street gangs, and criminal organizations.

In its governmental guise, patrimonialism is distinguished by running the state as if it were the leader's personal property or family business... In the first portion of his rule, [Putin] ran the Russian state as a personal racket. State bureaucracies and private companies continued to operate, but the real governing principle was Stay on Vladimir Vladimirovich's good side … or else...

To understand the source of Trump's hold on power, and its main weakness, one needs to understand what patrimonialism is not. It is not the same as classic authoritarianism. And it is not necessarily antidemocratic...

Patrimonialism's antithesis is not democracy; it is bureaucracy, or, more precisely, bureaucratic proceduralism. Classic authoritarianism—the sort of system seen in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union—is often heavily bureaucratized... By contrast, patrimonialism is suspicious of bureaucracies; after all, to exactly whom are they loyal? They might acquire powers of their own, and their rules and processes might prove obstructive. People with expertise, experience, and distinguished résumés are likewise suspect because they bring independent standing and authority. So patrimonialism stocks the government with nonentities and hacks, or, when possible, it bypasses bureaucratic procedures altogether... Patrimonial governance's aversion to formalism makes it capricious and even whimsical...

Also unlike classic authoritarianism, patrimonialism can coexist with democracy, at least for a while... Once in power, patrimonialists love to clothe themselves in the rhetoric of democracy...

Nonetheless, as patrimonialism snips the government's procedural tendons, it weakens and eventually cripples the state... Even if authoritarianism is averted, the damage that patrimonialism does to state capacity is severe. Governments' best people leave or are driven out. Agencies' missions are distorted and their practices corrupted. Procedures and norms are abandoned and forgotten. Civil servants, contractors, grantees, corporations, and the public are corrupted by the habit of currying favor...

Patrimonialism explains what might otherwise be puzzling. Every policy the president cares about is his personal property... He broke with 50 years of practice by treating the Justice Department as 'his personal law firm.' He treats the enforcement of duly enacted statutes as optional—and, what's more, claims the authority to indemnify lawbreakers... His agencies screen hires for loyalty to him rather than to the Constitution...

Yet when Max Weber saw patrimonialism as obsolete in the era of the modern state, he was not daydreaming. As Hanson and Kopstein note, 'Patrimonial regimes couldn't compete militarily or economically with states led by expert bureaucracies.' They still can't. Patrimonialism suffers from two inherent and in many cases fatal shortcomings.

The first is incompetence... Patrimonial regimes are 'simply awful at managing any complex problem of modern governance,' they write. 'At best they supply poorly functioning institutions, and at worst they actively prey on the economy.'...

Eventually, incompetence makes itself evident to the voting public without needing too much help from the opposition. But helping the public understand patrimonialism's other, even greater vulnerability—corruption—requires relentless messaging...

Patrimonialism is corrupt by definition, because its reason for being is to exploit the state for gain—political, personal, and financial. At every turn, it is at war with the rules and institutions that impede rigging, robbing, and gutting the state... As Larry Diamond of Stanford University's Hoover Institution said in a recent podcast, 'I think we are going to see an absolutely staggering orgy of corruption and crony capitalism in the next four years unlike anything we've seen since the late 19th century, the Gilded Age.'...

Jonathan Rauch’s latest book

Oh and Jonathan Rauch is amazingly productive for someone who has something to say. Here he is speaking about the subject of his next book.

Noah Smith nails it: again!

Noah Smith explains where he disagrees with N.S. Lyons. Me too.

"Men don't care what's on TV. They only care what else is on TV." — Jerry Seinfeld

N.S. Lyons is a popular essayist in the "national conservative" tradition. His Substack, The Upheaval, is recommended reading, even though I agree with less than half of what he writes. He is well-read and well-informed, he integrates information from across many domains, and he isn't afraid to think deeply about the big questions of history in real time...

In a recent essay entitled "American Strong Gods", Lyons identifies what in my opinion is a deep truth about our current historical moment. He writes of the end of the "Long Twentieth Century", a period that was defined by liberalism (social, political, and economic), and anchored by rejection of Adolf Hitler:

I believe that what we're seeing today truly is the end of an era, an epochal overturning of the world as we knew it, and that the full import and implications of this haven't really struck us yet.

More specifically, I believe Donald Trump marks the overdue end of the Long Twentieth Century…

Our Long Twentieth Century had a late start, fully solidifying only in 1945, but in the 80 years since its spirit has dominated our civilization's whole understanding of how the world is and should be…In the wake of the horrors inflicted by WWII, the leadership classes of America and Europe understandably made "never again" the core of their ideational universe...

Like all good essays, this overstates its case. The American-led liberalism of the postwar order was not a purely defensive project. The UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were not motivated by fear of Hitler's return, but by a desire to expand the boundaries of human freedom and dignity beyond anything seen in the prewar period...

And yet there is an important sense in which Lyons is right. The spectacular horrors and the spectacular failure of Hitler's regime provided a moral anchor that liberals could always use to argue for greater liberalism...

Lyons is right that the Trump Era marks the end of Hitler as the summum malum of Western culture — at least in the United States...

This tweet, I think, is illustrative of the thinking on the American right. It would be wrong to say that the Trump movement, or modern National Conservatism, represents a wholehearted endorsement of Nazism. But it should be uncontroversial to say that the American Right views wokeness as a greater threat than the potential return of Hitler.

Why has the legend of Hitler lost its terror? There are several reasons. The generation that fought and defeated the Nazis has largely passed away, meaning that for most Americans, Hitler only exists as a character in movies and books; as with Tamerlane or Genghis Khan, the fear of a mass murderer fades as the centuries pass...

Lyons is far more sanguine about this shift than I am. Personally, I think it was a good idea to vilify Hitler. As a general moral principle, "don't be Hitler" honestly seems pretty solid. And even if your only concern is the might of Western civilization, a man whose ideologically-motivated military campaigns led to the end of European global empires, slaughtered over 20 million Slavs, ended German's status as a great power, and cemented Soviet rule over half of Europe seems like he should probably serve as an example to avoid...

But Lyons believes that the end of anti-Nazism as the West's guiding principle will pave the way for the return of morality, community, rootedness, faith, and civilizational pride — the kind of things conservatives like...

I'm not quite so sure about Lyons' reading of history here. After all, as Robert Putnam chronicled in his book The Upswing, the postwar decades in America saw the greatest surge in church attendance, civic participation, family formation, and social solidarity since the early days of the Republic...

The "strong gods" were never stronger than they were among the generation of Americans who grew up listening to FDR preach liberalism on the radio and who went on to crush Adolf Hitler into the dust. Nor is it difficult to draw a causal line between the unifying struggle of the Second World War and the great American unity that followed.

The Greatest Generation believed with all their hearts that Hitler was Satan on Earth. But they did not believe that family, community, and tradition were little Hitlers that needed to be crushed in order to uphold the open society. Indeed, their society was both open and deeply rooted. My grandparents knew the names and the life stories of every one of their neighbors until the day they died; how many "national conservative" intellectuals and diehard Trump fans can say the same?...

Lyons believes that Trump is bringing [the "strong gods"] back:

Mary Harrington recently observed that the Trumpian revolution seems as much archetypal as political... This masculine-inflected spirit of thumotic vitalism was suppressed throughout the Long Twentieth Century, but now it's back…

Today's populism is…a deep, suppressed thumotic desire for long-delayed action, to break free from the smothering lethargy imposed by proceduralist managerialism and fight passionately for collective survival and self-interest...

Lyons thus sees Trumpism as a sort of Fight Club style reassertion of wild, unapologetic, masculine drive — only instead of directing it toward anarchism like Tyler Durden, Lyons sees Trump and Musk indulging their manly passion in the dismantling of the civil service.

But Lyons never explains exactly how this destructive impulse will bring back the return of the "strong gods" he yearns for. He sees the civil service and other American postwar institutions as obstacles to the revitalization of rootedness, family, community, and faith, but he doesn't really look beyond the smashing of those supposed obstacles toward the actual rebuilding. He just sort of assumes it will happen, or that it's a problem for another day.

I believe he's headed for disappointment. Trump's movement has been around for a decade now, and in all that time it has built absolutely nothing. There is no Trump Youth League. There are no Trump community centers or neighborhood Trump associations or Trump business clubs...

The MAGA movement, you see, is an internet thing. It's another vertical online community — a bunch of deracinated, atomized individuals, thinly connected across vast distances by the notional bonds of ideology and identity. There is nothing in it of family, community, or rootedness to a place. It's a digital consumption good. It's a subreddit. It is a fandom.

N.S. Lyons and the national conservatives have entirely misapprehended the cause of America's abandonment of rootedness, community, family, and faith. We didn't abandon those "strong gods" because liberals went too hard on old Adolf. We abandoned them because of technology..."

Farewell Blogger Kevin …

prompting self-reflection on anti-woke from Helen Lewis

Helen Lewis was one of the few on the left who joined the crusade against woke. I doubt I was much associated with the crusade but I felt the same then — and I do now. But I also thought then — as I do oh so much more now — that as infuriatingly immature and self-righteous as it was (and still is) woke was never on a par with what was coming at us from the right. But while I was ready for Donald Trump to be a lot better organised than he was last time, I hugely underestimated the ease with which he could simply operate outside the constitution. Then again, I shouldn’t be so surprised. He has obviously enough, operated in defiance of the law for his whole business life.

Kevin Drum, an old school blogger … died recently from cancer. Drum was forced out of Mother Jones at the height of Peak Cancel in 2021, for offences such as writing that he didn’t want to watch Parasite because it had subtitles. After a fair few twitterstorms along these lines, his junior colleagues wrote an open letter that accused him of racial insensitivity. …

Drum took his writing independent and — as far as I can see — declined either to badmouth Mother Jones publicly or to join the lucrative “I’ve been cancelled” circuit. … For years, Drum had been bringing in huge amounts of traffic for Mother Jones (something like a third of the total at times). Despite this, he refused all salary raises, preferring that the money go instead to his junior colleagues. “At any other company in America, he would have been paid fairly half a million to $750k a year,” writes Dreyfuss. “He brought in many times more revenue than that. But he never made more than $85k. He asked every single year that they take the money and put it into paying the fellows more and giving them a better stipend or lower premium for healthcare.” The same junior colleagues whose material conditions had been improved by Drum were the ones to cast him out.

Because I was raised a Christian, this story inevitably reminded me of The Good Samaritan. The point of that parable is that the priest and the Levite pass by the half-dead assault victim, while the Samaritan (from another tribe, one that Jesus’s audience would have hated) stops to help. The priest is an ostensibly holy man, with high social status, who has just come from performing rituals in the temple. But he has no compassion for the materially needy person right in front of him1. This is basically what a lot of 2020-era social justice people reminded me of—they wanted to do moral things that were well-rewarded with status and approbation, but they had no charity for the people right in front of them. Drum appears to have been the opposite: a good Samaritan.

Lately I’ve been questioning myself. Given the re-election of Donald Trump, did I spend too much time in the last half-decade writing about the excesses of the left?

My starting position has always been that the excesses of the left helped re-elect Donald Trump; also, that you can’t expect to be taken seriously on vaccines when you are denying sexual dimorphism2. But of course, the charge is frequently thrown about that anyone vaguely “anti woke” was just pandering to a rightwing moral panic. Now, that’s partially true. The Trump administration’s alleged commitment to free speech is tissue-thin—see the detention of Palestine activist Mahmoud Khalil. Nonetheless, stories like Kevin Drum’s really happened, and they were abominable. I’m proud that I stood up to my political “side” when that was unpopular.

Propaganda and lies?

Don’t worry. It’s to save the world

Note the careful juxtaposition in the text of his tweet. The committees of Samoa moved inland (because of a tsunami) and there’s rising sea levels. Sadly, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres drifted pretty close to a flat lie in his sound bite.

And here’s a depressing Swedish radio broadcast about how much PR bullshit has seeped into the UN’s ‘messaging’ on climate change. Like they say, climate change is real and scary enough. Viral memes are scary when you think the US is now ruled by little else. But degrading institutions to catch a meme is unforgivable. Source.

The Power of Proximity to Coworkers: Training for Tomorrow or Productivity Today? NBER Working Paper No. 31880 November 2023

Amidst the rise of remote work, we ask: what are the effects of proximity to coworkers? We find being near coworkers has tradeoffs: proximity increases long-run human capital development at the expense of short-term output. We study software engineers at a Fortune 500 firm, whose main campus has two buildings several blocks apart. When offices were open, engineers working in the same building as all their teammates received 22 percent more online feedback than engineers with distant teammates. After offices closed for COVID-19, this advantage largely disappears. Yet sitting together reduces engineers' programming output, particularly for senior engineers. The tradeoffs from proximity are more acute for women, who both do more mentoring and receive more mentorship when near their coworkers. Proximity impacts career trajectories, dampening short-run pay raises but boosting them in the long run. These results can help to explain national trends: workers in their twenties who often need mentorship and workers over forty who often provide mentorship are more likely to return to the office. However, even if most mentors and mentees go into the office, remote work may reduce interaction: pre-COVID, having just one distant teammate reduced feedback among co-located workers.

Martin Wolf: Can Europe rise to the occasion?

Having warned the world as best he could Martin Wolf is trying to meet the moment — by being useful. He asks what’s necessary for Europe to meet the catastrophe and shape its own destiny.

“We were at war with a dictator; now we are fighting against a dictator supported by a traitor.” Thus, in a brilliant speech, did Claude Malhuret, hitherto a little-known French senator, define the challenge of our age. He was right... The US and the world have been transformed for the worse. The question is how Europe can respond.

In the 1970s, I lived and worked in Washington DC... This was the era of Watergate. I watched Congress take its obligation to protect the constitution seriously. Nixon, facing impeachment, resigned.

Contrast this with Trump’s second impeachment in 2021 for inciting insurrection. His guilt was beyond doubt... but only seven Republican senators voted to convict. Congress let him off. The consequences were predictable.

Since the 1970s, the US has suffered a moral collapse... We see this in what this administration does to US commitments, allies, the press, and the law. My colleague John Burn-Murdoch has shown Maga attitudes resemble those of today’s Russians: power will not be yielded easily.

If the US is no longer the defender of liberal democracy, Europe is the only force potentially strong enough to fill the gap. To succeed, it must secure its home, relying on resources, time, will, and cohesion.

Europe can increase defence spending... While spending has risen, only Poland surpasses the US, relative to GDP. Fortunately, EU fiscal deficits and debt levels are lower than those of the US. The EU and UK’s combined purchasing power exceeds that of the US and dwarfs Russia’s. Economically, Europe has resources... though it needs reforms to catch up technologically.

Yet economic strength cannot turn into strategic independence overnight... European weaponry depends too much on US technology. Time is needed. The feared impact of lost US military support for Ukraine shows Europe’s vulnerability.

The third ingredient is will... Defending European values will be costly and even dangerous. Rightwing elements with Maga-like views exist. Some countries—Hungary, Slovakia, perhaps Austria—will have pro-Putin governments. Marine Le Pen has flirted with pro-Putin positions... The far right and far left are rising in Germany. Europe has “fifth columns” almost everywhere.

Yet some leaders, notably in Germany, are showing will... Friedrich Merz, expected to be the next chancellor, has agreed to amend the “debt brake” and spend billions on infrastructure and defence. He pledged to do “whatever it takes” for European security. Whether he delivers remains to be seen.

Finally, cohesion is essential... Unlike the US, China, or Russia, Europe is not a state. It lacks shared politics and finances. It needs near-unanimity in foreign policy and defence. Europeans relied on the US because it was the easiest course... If the US abandons them, they will still be tempted to shift the burden to a few big powers. Even coordinating Germany, France, and the UK will be difficult without a leader.

We have an irresistible force and an immovable object... Trump’s unreliability is the force; Europe’s inertia the object. Overcoming this must be done quickly. Until then, Europe will depend on an unreliable US.

If Europe does not mobilise quickly, liberal democracy might founder... Today feels a bit like the 1930s. This time, alas, the US looks to be on the wrong side.

Sabine Hossenfelder on Europe v the US

Henry Farrell to Silicon Valley: Take a chill pill

Written before the 2024 presidential election of Donald Trump.

It's a rare buccaneer who runs a book club. But in October 2012, the chief administrator of the Silk Road drug market, under the pseudonym "Dread Pirate Roberts," was on the dark web assigning readings from the anarchist libertarian philosophy of Murray Rothbard. Rothbard had argued that markets and individual connections were really all we needed. As the Dread Pirate, whose real name was Ross Ulbricht, summarized it, a happier world awaited those who took the exit road from ordinary politics. They could escape the "thieving murderous mits [sic]" of the state to embrace the freedom that emerged from a "multitude of voluntary interactions between individuals."

For Ulbricht, Silk Road wasn't just a way to make money but the tech-fueled expression of a political philosophy. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin had (supposedly) enabled a new realm of voluntary exchange outside the grasp of government, allowing people to buy and sell drugs and guns without the feds interfering. Of course, state tyranny might reemerge if voluntary organizations like Silk Road started to steal from their users, or spied on, or even killed them. Ulbricht, however, believed that the forces of market competition would prevent this from happening, leading to "freedom and prosperity the likes of which the world has never known."

Ambitious libertarian projects to escape the sordid compromises of politics have been part of Silicon Valley culture since the beginning. But Ulbricht's dream of escape from politics and its vexations has become increasingly influential in the decade since the Dread Pirate Roberts book club. [Though Ulbrich was arrested and sentenced to two terms of life imprisonment plus 40 years without parol for participating in “a continuing criminal enterprise, distributing narcotics by means of the internet, conspiracy to commit money laundering, conspiracy to traffic fraudulent identity documents, and conspiracy to commit computer hacking, he was pardoned by the new President on Trump’s second day of office in 2025.] Several prominent Silicon Valley investors and entrepreneurs have become disenchanted with the U.S. government, East Coast media, and even their own employees...

If Silicon Valley thinkers are to take their political commitments to liberty and technological progress seriously, they need to acknowledge and deal with the contradictions in their ideological positions rather than papering over them. Rather than spinning out business models into unconvincing grand social theories, they ought start with good theories and think seriously about the implications for their business models.

Here, they might usefully learn from a consistent line of reasoning in classical liberalism that they currently neglect. Eighteenth-century liberals like Hume and the authors of The Federalist Papers were obsessed with the dangers of faction, and the need to channel it so that it did not overwhelm society. Their twentieth- and twenty-first-century heirs, like Ernest Gellner, Douglass North, and Barry Weingast, have adapted the tools of social science to understand the circumstances under which open societies can live and thrive despite, and sometimes thanks to, their internal contradictions.

The lessons are straightforward, even if they jar painfully with some common myths in the Valley. Actual free markets require a state that is both powerful and constrained. Real technological progress is not solely generated by risk-taking entrepreneur-heroes in a social vacuum. It is also the contingent by-product of a fragile set of common social and political arrangements. Without constitutional constraints, voluntary interactions tend, as Silk Road did, to degenerate into gangster capitalism. And the trick of creating a vibrant open order is not to try to escape the sordid bargains of politics, or to eliminate your enemies, but to channel disagreement usefully. You cannot escape the company of those whom you detest, however unpleasant you may find it—that is the fundamental premise of the open society. When you try, you discover (as many libertarian schemers looking to improve the human condition have discovered) that you bring the disagreements along with you. You have to figure out ways to live with those who oppose you and whom you oppose, and ideally to derive collective benefit from your mutual vexations...

Profit models blur into grand plans to improve the human condition, and vice versa. Srinivasan, in addition to writing about the benefits of exit, has invested heavily in crypto. His Network State conferences bring together investors and political activists into shared arguments and, perhaps, coordinated actions in the future...

It is hard not to be tempted by an ideology which suggests that your industry's approach to business and technology provides the basic matrix on which the entire future order of the planet and, perhaps, the nearer parts of the galaxy, ought be constructed. It becomes remarkably easy to view countertendencies that frustrate your business interests or critics who puncture your personal amour-propre as world-historic threats to progress, who need to be utterly defeated. Your business efforts can, almost imperceptibly, become entwined with grand narratives, in which you and your comrades are the heroes who bring about extraordinary changes in the history of the world and cosmos. All this makes it difficult even to discern the contradictions and awkward questions that attach to your ideology, as they do to all ideologies, let alone to address them...

Finally, and most generally, the open society is inevitably vexing. It is full of people who disagree with you, who have different aspirations and understandings of how to reach them, who will criticize you, annoy you, and make you generally unhappy... [F]or better or worse, this pain and mess is unavoidable. If you want to live in a free and open society, you have no choice but to endure it... These thinkers, and the rest of us too, should summon their courage to deal with it, and perhaps even turn their energies to thinking about how it could be channeled better and more usefully.

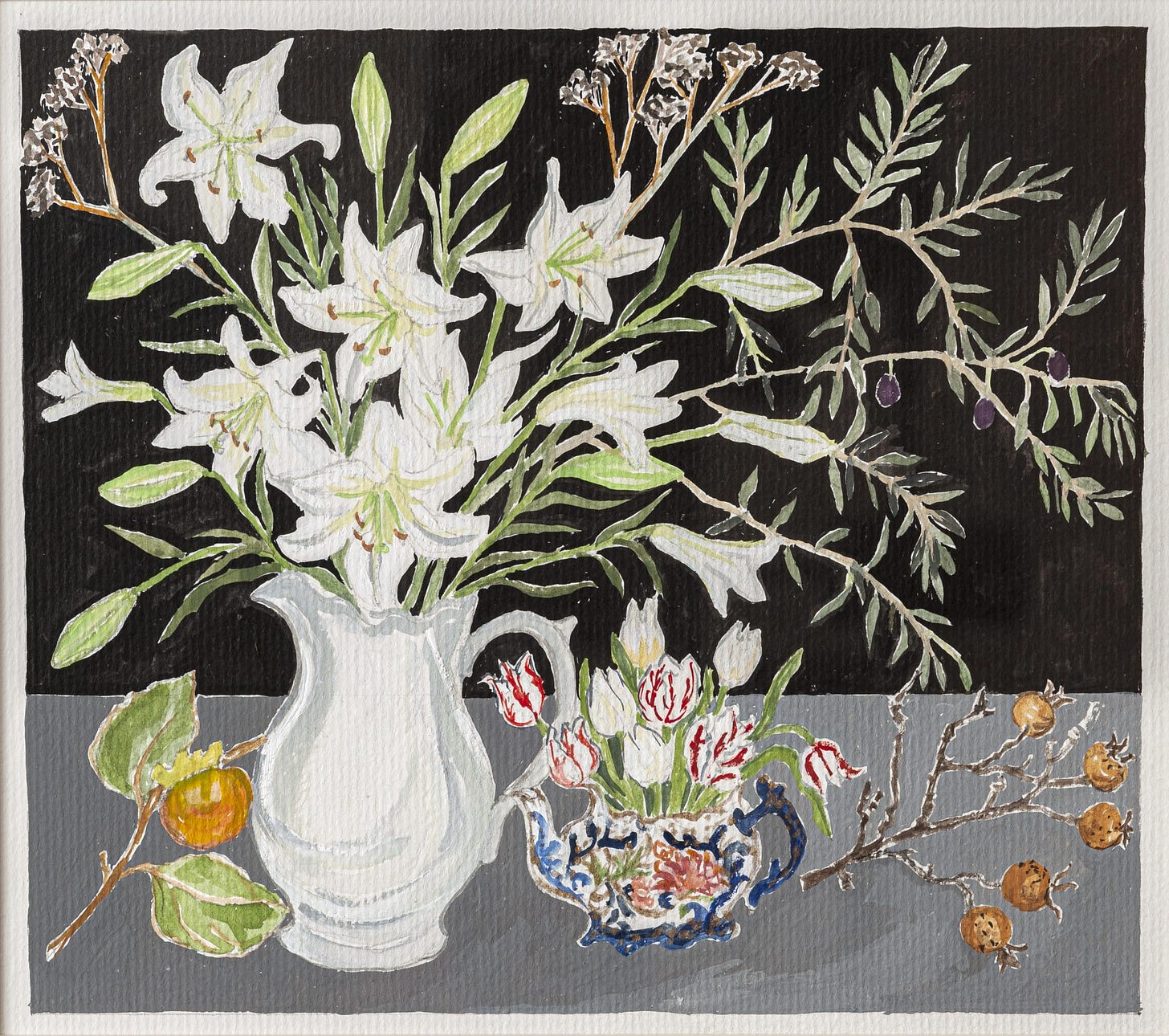

Alexandra Lewisohn at 44 Downstairs

Development aid: what to do

Felix Martin offers some helpful advice. Certainly more helpful than the feckless PR of “17 Sustainable Development Goals measured by 169 separate targets”.

Donald Trump’s new administration has plunged international development assistance into an existential crisis... Within hours of taking office... [he] issued an executive order mandating a 90-day pause on most aid to poorer countries. Last week, the State Department confirmed it was cutting more than 90% of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s programmes.

The radical overhaul is upending other countries’ development assistance too. Prime Minister Keir Starmer... announced he was slashing Britain’s aid budget... to help meet U.S. demands for increased defence spending. The previous government had already reduced aid from 0.7% of GDP. Britain’s minister for international development promptly resigned.

Yet the travails of the traditional model of development assistance started well before the latest assault... Four longer-term trends were already challenging its basic assumptions.

The first is the globalisation of international capital markets... Over the last decade, however, more than 90% of capital flows to low and middle-income countries came from private investors.

That change was due in large part to a second long-term trend: the economic transformation of the [Global South]... In 1990, developing nations accounted for barely more than a third of global GDP. Today, their share is about 60%... many of those countries are exporting capital, including... China.

A third trend... was its ever more expansive objectives. Until the end of the 1980s, development essentially meant economic growth... By 2015, [the UN’s] 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development... included no fewer than 17 Sustainable Development Goals measured by 169 separate targets.

More comprehensive notions of development led to less consensus on how to promote it – the fourth long-run trend... In the following two decades, the focus shifted to making aid conditional on market-liberalising policy reforms... The fact that China... had eschewed the so-called “Washington Consensus”... was simply too big to ignore.

All four of these long-term trends were driven by geopolitical shifts... The concept of aid unlocking private finance in pursuit of broad social and environmental objectives... relied on the rules-based, international order that flourished after 1989.

Trump’s return to the White House means the geopolitical tectonic plates are shifting once again. The challenge... is to find a model of development assistance which also serves donors’ strategic interests in a more contested and multipolar world.

One candidate is the model adopted by China... Since 2013, [China] has provided at least $1.3 trillion in development finance under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – becoming... the largest single bilateral donor in the world... Yet economically, its success is questionable... 80% of lending by the People’s Republic is now supporting borrowers in financial distress... “the world’s largest official debt collector.” That is hardly a model most donors would wish to imitate.

Another possibility is that the United States reallocates its aid budget to the State Department... Yet it is not obvious how international development assistance could coherently serve an explicitly isolationist US foreign policy... There is a reason no one ever founded a Nationalist International.

The most successful model of how to marry idealism with strategic utility... is hiding in plain sight... the process of accession to the European Union which... has enabled eleven... countries in eastern Europe to join the ranks of the most prosperous nations on earth.

It is tempting to think the EU’s circumstances are so specific that there can be nothing for other donors to learn... The real secret sauce was explicit political partnership, the coherence of aid and trade, and... extreme openness... to private capital inflows...

In 1993, the EU’s current Eastern members had an average per capita GDP barely one tenth of its Western old guard... Three decades later, Poland is richer than Portugal, Slovenians are better off than Spaniards... Just as notable as the economic impact... has been its geostrategic success...

If that is not a model of international development assistance fit for a hard-nosed, realist age, it is difficult to know what is.”

On the Economic Infeasibility of Personalized Medicine, and a Solution.

Technological advances and genomic sequencing opened the road to personalized medicine: specialized therapies targeted to patients displaying specific molecular alterations. For instance, targeted therapies are now available for 50% of lung cancer patients—with some alterations affecting less than 1% of patients—greatly increasing life expectancy. In an investment model of drug development, we show that current institutions mandating experimentation and approval of individual therapies eventually disincentivize investments in personalized medicine as researchers identify increasingly rare alterations. Recent AI-based technologies, such as AlphaFold3, make personalized medicine viable when regulatory approval regards the process for drug discovery rather than individual therapies.

A fun post

Great advice on using AI

The craft of stand-up takes a few years to master

Yoram the stand-up economist was quite funny when I first saw his videos, but he’s got a lot better.

Marilyn!

I happened upon this one hour lecture on Marilyn from 2012 in the LRB. I was suspicious of the easy ideological overlay of the author, and an undertone of self-righteousness. But the content was fascinating and I’ve always had a fascination and deep admiration for Marilyn, made all the more tantalising by her unsurprising failure to achieve what she wanted to achieve despite a shocking start in life. The lecture is 10,000 words long and I listened to it as a podcast, but I've asked ChatGPT to extract the most intriguing and interesting 600 words which I reproduce below.

In the end, according to this interpretation, which sounded right to me, she was betrayed by Arthur Miller — not in a romantic sense (though he may have done that too) but in a deeper sense: In his incomprehension of her, and in particular his interpretation of her striving for some kind of articulation of her own being against the grain of the situation she found herself, as hysteria.

She was luminous ... Unlike Dietrich, Garbo or indeed Elizabeth Taylor ... there isn’t a single straight line [in her face] ... Even Laurence Olivier, who mostly couldn’t stand her, had to concede that ... she lights up the scene (the cinematographer Jack Cardiff said that she glowed) ... But the question of what ... she was lighting up ... is rarely asked. Luminousness can be a cover – in Hollywood, its own most perfect screen ... Monroe herself knew the difference between seeing and looking. "Men do not see me," she said, "they just lay their eyes on me."

In Reno in the summer of 1960, journalist Bill Weatherby found himself Monroe’s confidant ... She made thinking seem like a serious, deliberate process ... "She gave thinking her serious attention" ... Monroe’s written fragments, poems, diaries and notebooks ... give us the opportunity to look into the mind of a woman who was not meant to have one ... "In times of crisis," she wrote, "I try to think and use my understanding."

At an integration party ... Weatherby became the lover of Christine, a young black woman ... Monroe, it turned out, was the only white star who had ever interested Christine ... "She’s been hurt. She knows the score ... I don’t read the gossip stuff. That’s what comes out of her movies ... She’s someone who was abused. I could identify with her ... I never could identify with any other white movie star. They were always white people doing white things."

Christine had put her finger on the pulse of cinema. What matters is who it allows – or rather invites – you to be ... Monroe is an emblem of that delusion – she made her way to the top from nowhere – but she also exposed the ruthlessness and anguish at its core ... All at once, Weatherby understood the link between Hollywood and the racist American South ... "Blacks," he states, "had been more rigidly typed than Monroe" ... Hollywood trashes its stars – especially its women ... Monroe more or less consistently hated the roles she was assigned ... "If I hadn’t become popular," she said to Weatherby, "I’d still be a Hollywood slave."

James Baldwin identified with her too ... Lee Strasberg’s daughter ... remembered a self-portrait Monroe drew alongside a sketch of a Negro girl ... And according to Gloria Steinem ... when the Mocambo nightclub in Los Angeles was reluctant to hire ... Ella Fitzgerald, Monroe offered to take a front table every night if he hired Fitzgerald ... Fitzgerald never forgot ... Monroe, she said later, was "an unusual woman – a little ahead of her times."

One of Monroe’s heroes was Abraham Lincoln ... she described Sandburg’s poems as "songs of the people by the people and for people" ... "There was something democratic about her," Sandburg commented ... Being attached to Lincoln is a way of reminding America of ... a strong but permanently threatened liberal version of itself.

Monroe wanted money to free herself ... "I’ll never tie myself to a studio again," she said to Weatherby, "I’d rather retire" ... Monroe surrounded herself with people who saw it as their task to rip the cover off national self-deceit ... She had her own brush with McCarthyism when Arthur Miller was summoned by HUAC and she spoke out on his behalf.

Someone screams – a woman: someone else, or rather pretty much everyone else, covers their ears ... As Monroe put it in one of the fragments of her 1951 notebook, "Actress must have no mouth" ... "You see," she said in the last interview she gave, "I was brought up differently from the average American child because the average child is brought up expecting to be happy" ... "When you’re famous you kind of run into human nature in a raw kind of way ... You’re always running into people’s unconscious."

Above all she wanted to be a serious actress ... "I wanted to be an artist, not an erotic freak" ... This was not mere pretension ... According to Lee Strasberg, she read the part of Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie at the Actors Studio more powerfully than any actress he had ever heard ... "Nobody owns me, see?"

That is why so much hung finally on The Misfits ... "He was supposed to be writing this for me," she said to Pepitone, "He could have written me anything and he comes up with this" ... She wanted to get her point across ... It could have been one of the most radical moments in her film career, the occasion where she offers up her diagnosis, explains what’s wrong with America, the dangers beneath the illusion of innocence and perfection ... "If that’s what he thinks of me, well, then I’m not for him and he’s not for me."

Heaviosity half hour

Ezra Klein: How the founders baked in instability

From Why we’re polarized.

The most powerful critique of America’s political system was published in 1990 by a Spanish political sociologist named Juan Linz.

Linz was an outsider to American politics and, more important, to its self-serving mythologies. Born in the Weimar Republic in 1927 and raised in Spain under the Francoist dictatorship, Linz both lived through and studied the circumstances in which political systems fail. The causes of collapse were often encoded in the architecture of the government: he showed that systems based around an independent president tended to dissolve, as conflicts between the executive and the legislature were often irresolvable, and irresolvable conflicts end in crisis and collapse.

But America’s political system posed a puzzle for Linz. As an outside observer, he was free from the quasi-religious reverence we afford our founding documents. He knew that the American political system had failed wherever else it had been tried. He knew that America itself was loath to impose its system on other nations—for all our nation-building adventurism, we never give any country developing into a democracy a system that works like ours. But he also knew that in America, the American political system had worked.

In 1990, in a paper entitled “The Perils of Presidentialism,” Linz explained why. The “vast majority of the stable democracies” in the world were parliamentary regimes, where whoever wins legislative power also wins executive power.9 America, however, was a presidential democracy: the president is elected separately from the Congress and can often be at odds with it. This system had been tried before. America, worryingly, was the only place where it had survived.

The problem is straightforward. In parliamentary systems, the prime minister is the leader of the coalition that controls the legislature. If that coalition loses an election, it loses power. But at any given moment, only one party or coalition holds power. In presidential systems, by contrast, one party can control the legislature and another can control the presidency. Both parties, then, have a claim to democratic legitimacy. “Under such circumstances,” asked Linz, “who has the stronger claim to speak on behalf of the people: the president or the legislative majority that opposes his policies?”

It gets worse. What happens when the majorities that the president and the Congress represent are different majorities, who voted at different times and through different methods? Linz noted that presidents tend to be elected by voters but legislatures tend to reflect geography, with small towns and rural areas given outsized power. It’s hard enough resolving a democratic disagreement that plays out among a single electorate. What do you do when you’re facing a disagreement that reflects different kinds of electorates?

It’s a question with no answer. In general, we assume a system like this encourages compromise, and that’s true, when the competing political coalitions are open to compromise. But a system like this can also encourage crisis—crises where, in other countries, “the armed forces were often tempted to intervene as a mediating power.”10

This is why there are no long-standing presidential democracies save for the United States. And it’s why America doesn’t impose its specific form of government on others. “Think about Germany, Japan, Italy, and Austria,” wrote Vox’s Matt Yglesias.

These are countries that were defeated by American military forces during the Second World War and given constitutions written by local leaders operating in close collaboration with occupation authorities. It’s striking that even though the US Constitution is treated as a sacred text in America’s political culture, we did not push any of these countries to adopt our basic framework of government.11

Linz admitted that he couldn’t fully answer the question of why America was different. He suspected that “the uniquely diffuse character of American political parties—which, ironically, exasperates many American political scientists and leads them to call for responsible, ideologically disciplined parties—has something to do with it.” Whatever the explanation, Linz continued, “the American case seems to be an exception; the development of modern political parties, particularly in socially and ideologically polarized countries, generally exacerbates, rather than moderates, conflicts between the legislative and the executive.”12

Linz was writing in 1990, when America’s political parties were far more exceptional, far more mixed and moderated, than they are today. But what read in 1990 like an explanation of what made America’s political system different now reads like an analysis of why America’s system is in crisis. The Garland affair is a perfect example. For all the fury over McConnell’s behavior, what, exactly, did he do wrong?

In the 2014 election, Republicans took control of the Senate with a decisive fifty-four-vote majority. True, the 2014 election had the lowest turnout in seventy years, and sure, only a third of Senate seats are up for election in any given year, and yes, the Senate is a noxiously undemocratic institution that gives a voter in Wyoming sixty-six times as much power as a voter in California, but the rules are what they are. McConnell was leader of a Republican majority in the US Senate. He had the votes to block any nominations Obama might make—why shouldn’t he have used them? Did the voters who gave him that majority really want him to let Obama replace Scalia with a Democratic justice, no matter how moderate? Wouldn’t it have been more of a betrayal of his voters if he’d led a new Republican majority in the Senate to help Obama flip the Supreme Court to a 5–4 liberal split?

You can argue, as many did, that Obama represented a more legitimate democratic majority. He won a national election, with much higher voter turnout, in 2012. He was president of the United States of America. He had nominated a clearly qualified candidate, in accordance with the historical norm. McConnell’s behavior was both unprecedented and dangerous: in flatly refusing to consider any candidates nominated by a president of the other party, McConnell established a principle that could destroy the Supreme Court. Given the Senate’s small-state bias, it’s easy enough to imagine extended periods of divided control, and given McConnell’s successful deployment of absolute obstruction, it’s easy enough to imagine vacancies on the Court going continuously unfilled.

But why is that McConnell’s problem? Why should he have been the one to fold? Perhaps Obama should have bowed to the winners of the most recent election and nominated a Scalia-esque conservative to fill Scalia’s seat. It may sound ridiculous, but both McConnell and Obama represented legitimate electoral majorities, and there was no obvious way to resolve their differences.

Ideological differences are easier to resolve when they are smaller. That’s why Linz put “the uniquely diffuse character of American political parties” at the center of America’s unusual political success. In the twentieth century, the ideological and demographic diversity of the Republican and Democratic coalitions lowered the stakes of partisan political disagreement considerably. Our core cleavages played out within the two parties rather than just between them. But those days are gone.

McConnell’s obstructive innovations are a cause of our current divisions, but they are also a consequence of them. The question that Supreme Court vacancies pose in the modern era is different from the question they posed in previous eras. That’s because a more polarized political system has led to a more polarized Supreme Court (which, as with the Garland case, is further polarizing the political system—remember, everything is a feedback loop!).

In an analysis published after Justice Anthony Kennedy retired, law professors Lee Epstein and Eric Posner wrote in the New York Times that in the ’50s and ’60s, “the ideological biases of Republican appointees and Democratic appointees were relatively modest.”13 Even as late as the ’90s, justices regularly voted in “ideologically unpredictable ways.” In the 1991 term, for instance, Byron White, a Democratic appointee, “voted more conservatively than all but two of the Republican appointees, Antonin Scalia and William Rehnquist.”

But that’s changed. Over the past decade, “justices have hardly ever voted against the ideology of the president who appointed them,” Epstein and Posner find. “Only Justice Kennedy, named to the court by Ronald Reagan, did so with any regularity.” Their chart is striking:

The Supreme Court is a powerful institution in American life, and it has often been a controversial institution in American life, but it has not always been a politically polarized institution in American life. As the parties have become more ideological, however, their expectations for Supreme Court justices followed suit.

It’s easy to read an analysis like this and think the authors are describing a golden age. But it’s all a matter of perspective. The eras of relative moderation are considered eras of failure and betrayal by the political parties responsible for them. Republicans lament the heterodoxies of justices like Earl Warren, John Paul Stevens, David Souter, and Anthony Kennedy—indeed, it’s precisely in response to these unpredictable appointments that the parties began to develop more ideological and reliable methods of sourcing judges.

Scalia was one of those more ideological justices, and he made the case for his approach explicitly. “It really enrages me to hear people refer to it as a politicized court,” he said in 2012. “Maybe the legislature and the president are not as stupid as you think. They assuredly picked those people because of who they are and when they get to the court they remain who they were.”14 In this telling, the point of the nomination process is to find a candidate who will vote in concert with the expectations of his sponsors. Future divergence isn’t a feature of independent thinking but a flaw in vetting.

Today, candidates considered for Supreme Court vacancies have a vanishingly small chance of surprising their sponsors in the future. The path to being nominated to the Court runs through decades of ideological and professional party service. Kennedy’s ultimate replacement, Brett Kavanaugh, was a top staffer in the George W. Bush administration in addition to being a member of the conservative legal group the Federalist Society.

It’s not just that more ideologically reliable candidates raise the stakes around Supreme Court nominations. Deeper political divides are leading to more partisan cases: consider the Right’s multiyear effort to convince the Court to destroy Obamacare, a campaign with no corollary in the aftermath of, say, Medicare’s or Medicaid’s passage. Partisan disagreement and paralysis in Congress are making the Court’s judgments more consequential, as when the Court throws out a bill or invalidates a program; legislators rarely have the bipartisan consensus or partisan power to revisit the legislation and answer the Court through modifications.

This is the context for the Garland collision. Yes, McConnell broke with past practice in refusing to even consider qualified Democratic candidates. But he was operating in an era when the Supreme Court had become a more partisan institution rendering more partisan decisions on more partisan cases. The idea that nominees should be judged on professional merit rather than philosophical alignment had long since ceased to reflect the real workings of the system. There is perhaps no single vote members of the US Senate take with as much long-term ideological importance than that of a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court, and asking them to keep that vote, and that vote alone, separate from the ideological promises they make to their voters, and to themselves, is bizarre.

This is a problem that afflicts much in American governance. The rules, as set down in the Constitution and our institutions, push toward partisan dysfunction, conflict, and even collapse. The system works not through formal mechanisms that ensure the settlement of intractable disputes but through informal norms of compromise, forbearance, and moderation that collapse the moment the stakes rise high enough. McConnell didn’t break any laws or devise any new powers to stop Garland; he just led his party to break with the historical practice of appointing Supreme Court justices they didn’t agree with ideologically—a historical practice that forces parties to regularly cross their ideologies and voters for the good of the system. In breaking with that precedent, he was doing precisely what his voters wanted, and they rewarded him for it in the next election. Why should any of his successors do anything different?

But now imagine a world where Republicans, due to their advantages in small states, routinely hold the Senate while Democrats, who’ve won the popular vote in six of the last seven presidential elections, routinely hold the White House. What happens to the Supreme Court in that world? Do vacancies just go unfilled? What if Democrats then come to see the Supreme Court as fundamentally illegitimate, as its conservative majority relies on Republicans refusing to consider Democratic nominees? Do Democrats continue abiding by its rulings?

As Linz argued, a presidential political system in which power is divided among different branches works when the parties that control those branches are ideologically mixed enough to cooperate with one another, and that was, for much of the twentieth century, the secret to the American political system’s success. But now America’s political parties are ideologically polarized. They are also, importantly, nationalized.

All politics isn’t local

Nebraska senator Ben Nelson was the final, crucial vote on the Affordable Care Act. Nelson was an old-school Democratic centrist, a transactional, silver-haired former insurance executive who held on in a red state through acts of ostentatious moderation and a laser-like focus on Cornhusker interests. But he was in a bind. The choice on Obamacare was yes/no. Democrats needed his vote to pass the law. Nelson wanted the law to pass. But Obamacare was unpopular back home, and Nelson was up for reelection in 2012. He was caught between his career, his party, and his conscience.

Nelson’s solution was to split the ideological interests of Nebraska’s Republicans from the financial interests of Nebraskans. Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion was built with an unusual structure. Typically, Medicaid is funded by a roughly 60:40 split between the federal government and the states. The Affordable Care Act, however, promised that the federal government would pay 100 percent of the law’s new Medicaid costs for three years, before phasing down to a 90:10 split by 2020. But some conservatives said that even the 10 percent states were being asked to pay was too much. This was, in particular, a charge levied by Nebraska’s popular Republican governor, Dave Heineman. So Nelson negotiated a special deal on the state’s behalf: for Nebraska, the federal government would carry 100 percent of the Medicaid expansion’s bill, a subsidy worth more than $100 million.

Nelson was doing what members of Congress have done since the dawn of the republic: winning support for a polarizing national policy by extracting a material concession for his state. The American political system is built on a deep sense of place. The House isn’t meant to host the meeting of two parties but of 435 districts; the Senate is not meant to represent red and blue but to balance the interests of fifty states. This reflects the Founders’ belief—true in their time—that our political identities were rooted in our cities and states, not the more abstract bonds of nationhood. “Many considerations … seem to place it beyond doubt that the first and most natural attachment of the people will be to the governments of their respective States,” wrote James Madison in Federalist 46.

The centrality of state and local political concerns in national politics has been one of the American political system’s brakes on polarization. The zero-sum forces of two-party competition were moderated by the regional interests of politicians rooted, first and foremost, in a particular place. Sure, you may be a Republican, and that bill might be pushed by Democrats, but you’re a Republican from Oklahoma, dammit, and that bill is good for Oklahoma. Catering to a member of Congress’s particularistic interests, either through the direct design of the legislation or through earmarks offering unrelated benefits, gave congressional leaders ways to build coalitions that the logic of partisanship denied. Your party might not want you to vote for that bill, but if you vote for it, your district will get money for a bridge it desperately needs, and putting your name on that bridge is worth more than keeping your copartisans happy.

At least, it was.

In his book The Increasingly United States, Daniel Hopkins tracks the troubling nationalization of American politics. At the core of that nationalization is an inversion of the Founders’ most self-evident assumption: that we will identify more deeply with our home state than with our country. Hopkins traces the change here in a variety of clever ways. He ran a text analysis of digitized books going back to 1800, comparing use of the phrase “I am American” with “I am a [Californian/Virginian/New Yorker/etc.].” Prior to the Civil War, expressions of state identity were far more common than expressions of national identity. National identity took the lead in the run-up to World War I, the two traded places for a while in the early twentieth century, and then, around 1968, expressions of national identity raced ahead and never looked back. He shows that when you ask Americans to rank their most important identities in surveys, almost everyone lists nationality in their top three, while the number listing their state, city, or neighborhood lags far behind. He finds that people are likelier to feel insulted when America is being criticized than when their state or city comes in for scorn. He shows that when asked to explain why they are proud of their nation or their state, they routinely express national pride in terms of politically relevant values, while state pride tends to focus on geographic features. I love America because of freedom; I love California because of beaches.

If all of this seems obvious—if you take the centrality of national identity for granted—that’s the point: what was unimaginable to the Founders is self-evident to us.

As goes identity, so goes politics. In an analysis of more than 1,600 state party platforms dating back to 1918, Hopkins finds while “the platforms in earlier eras focused more on state-specific topics,” modern platforms “now emphasize whatever topics dominate the national agenda.” Similarly, he shows that in 1972, “knowing which way a state leaned in presidential politics told one nothing about the likely outcome in the gubernatorial race.”15 Today, it tells you most of what you need to know.

The culprit here is obvious. In recent decades, the media and political environments have both nationalized. Voters following politics today get constant cues to think about national politics, but coverage of state and local politics is declining. For instance, growing up, I read the Los Angeles Times and listened to LA’s public radio station, KCRW, which fed me national political stories but also state and local stories. I developed, as a result, a pretty strong identity around California politics, which was less polarized than national politics and focused on very different questions. What I never did was read the New York Times, because we didn’t get it, or listen to national political podcasts, because they didn’t exist.

If I were growing up outside Los Angeles today, perhaps I’d be reading the newly revitalized LA Times, but it’s likelier, as a political junkie, that I’d be reading the New York Times and the Washington Post and Vox, listening to political podcasts, and watching cable news. All of that would be civic-minded and informative, but it would be pounding away at my national political identity and underdeveloping the parts of my political psyche rooted in the place I actually lived. A nationalized media means nationalized political identities.

States used to have different political cultures from that of the nation as a whole. That gave members of Congress crosscutting incentives from what the national parties wanted. Now those incentives are, like so many others, stacked. As Hopkins writes, “Rather than asking, ‘How will this particular bill affect my district?’ legislators in a nationalized polity come to ask, ‘Is my party for or against this bill?’ That makes coalition building more difficult, as legislators all evaluate proposed legislation through the same partisan lens.” A more nationalized politics is a more polarized politics.

Here’s an easy way to realize the truth of Hopkins’s point: if local interests drove voting patterns, you could predict how a member of Congress would vote on the Affordable Care Act by knowing whether the uninsured rate among his or her constituents was above or below the national average. The ACA was, above all else, a direct subsidy to areas with larger uninsured populations from areas with smaller ones. But how a member of Congress voted on the ACA was almost perfectly predicted by party affiliation—as evidenced by the fact that not a single Senate Republican voted for it and not a single Senate Democrat voted against it. State conditions predicted nothing.

A weird thing happened as we nationalized our politics. We became disgusted with the ways that local politics played out nationally. Take earmarks, the small addenda members of Congress would add on to bills to fund a road, a hospital, or a job-training bill back home. Earmarks were a way that bipartisan cooperation was, yes, bought. The Congress reporter Jon Allen described how it worked in a 2015 Vox article:

In 2003, I asked Jack Murtha, the Democratic defense appropriator who controlled about $4 billion in earmarks each year, about Tom DeLay, the Republican leader known as “The Hammer” for his ability to nail down votes. Murtha sat in the far corner of the Democratic side of the House, out of view from the press galleries, and DeLay would sometimes come to visit him before a tight vote. When DeLay needed a few Democrats to secure a win on the floor, Murtha said, “He comes over to the corner, and we work it out.” Murtha’s earmarking power meant that he had a roster of people who owed him favors. For a little more money, he could easily swing a small bloc of votes to help DeLay pass a bill. Murtha and DeLay didn’t agree on much, but earmarks kept them talking, and working with each other.16

In 2011, Congress got rid of earmarks entirely. They were considered a corrupt, and a corrupting, form of politics. Much better to have Congress run on pure principle and partisanship than the grimy work of negotiating something tangible for your constituents. To ideologues, transactional politics always looks dirty. To the transactional, ideologues look self-destructive.

That is, in the end, what happened to Nelson. Rather than being celebrated back home for cutting Nebraska such a sweet deal, conservative media pounced on him. His concession got branded the “Cornhusker Kickback,” and his own governor told him to turn it down. “Now it’s a matter of principle,” Heineman told Politico. “The federal government can keep that money.”17 Nelson called him “foolish” but backed down. The provision was stripped from the bill. Nelson, seeing the writing on the wall, declined to run for reelection in 2012 and was replaced by a Republican.

That same year, Heineman cautioned his constituents against accepting the Medicaid expansion they could’ve had for free. “If this unfunded Medicaid expansion is implemented, state aid to education and funding for the University of Nebraska will be cut or taxes will be increased,” he warned.18

I was in tears about Kevin Drum; I can remember even before he was at the Washington Monthly. Absolutely unique voice that will not be replaced. (I will happily watch anything and everything with subtitles and was excited to read the words of "Dance The Night" off the screen since Dua Lipa is hardly the most intelligible singer in the world)

"This is why there are no long-standing presidential democracies save for the United States."

The French presidential system had been in force since 1958 and has some similarities with US presidential democracy - some important differences are summarised below (source: Google AI overview)

"The French semi-presidential system grants the President more power than the US presidential system, with the French President holding the head of state and having significant influence over the government, while the US President, as both head of state and government, faces greater checks and balances.

Here's a more detailed comparison:

French Semi-Presidential System:

Head of State and Government:

The French President is both the head of state and holds significant influence over the government, although a Prime Minister also serves as the head of government.

Power:

The French President has considerable power, including the ability to dissolve parliament and appoint the Prime Minister, and can issue decrees with the force of law.

Impeachment:

The French Constitution does not provide for any impeachment of the president, and the president's power is subject to fewer restrictions"