What's your legacy: quiz

And other things I found this week

Ask a silly question …

Matt Gaetz

I haven’t caught up with all the excitement about Donald Trump’s nominees. Matt Gaetz has some black marks against him. (In fact in finalising this newsletter I learn that his nomination’s been withdrawn.) It may have been the purest hypocrisy, I have no idea, but it was still worth drawing attention to senior Congressional Democrats (and I presume Republicans) not just being active traders of stocks that give them obvious conflicts of interest as policy and lawmakers. They are also active insider traders! #NiceWorkIfYouCanGetIt.

Fortunately we’re cleaning up our own act down under … Oh wait!

Inspector Clouseau — with a dash of self-righteousness

Bernard Keane holds up his placard chanting

Inspector Clouseau

Got to go

Quite

The head of what is increasingly regarded as the National Corruption Cover-up Commission, Paul Brereton, has screwed up — several times. Most recently, it was during a speech to the National Public Sector Governance Forum, large chunks of which were devoted to Brereton trying to explain away his failings.

Part of Brereton’s speech was about expectations management. It’s not so much about finding individuals corrupt, he explained: after all, “individual accountability alone cannot bring about systemic change. For this reason, the commission is prioritising corruption prevention and education alongside its investigations.”

[But] there’s nothing as educational to public officials as seeing one of their own locked up for corruption. … So, the NACC is devoting resources to giving ethics lessons to decision-makers, when it is painfully clear corruption problems within the federal government stem not from ignorance of the vast array of ethical advice available … but from politicians’ wilfully self-interested political decisions and public servants’ blatant violations of the Commonwealth procurement rules.

Brereton also … has a tightly defined view of accountability. He singles out the resignation of Kelly Bayer Rosmarin as CEO of Optus in the wake of its massive outage. Repeating remarks he has made previously, he says, “Who is going to benefit from the resignation of Optus’ chief executive? I don’t see that Optus is going to benefit in any operational sense. Reputationally, there’s been a sacrifice to the gods if you like, but that’s about all there is to it.”

So much for fostering a culture in which responsibility is accepted — apparently leaders actually delivering on the idea of taking responsibility is merely a “sacrifice to the gods” — another indication that Brereton sees himself as elevated above the primitives howling for his resignation in the wake of his robodebt failings.

Brereton devotes more than 1,200 words to explaining away his decision to help block an investigation into robodebt despite having what he downplays as a “past professional relationship” with one of the chief perpetrators — a misjudgment that the inspector of the NACC found amounted to officer misconduct by Brereton. …

In other words, maybe — maybe — he made a mistake, but he was trying to do the right thing. For a set of decisions described by the inspector as “an error of judgment rather than a matter of mere procedure”, it’s an extraordinary response from the man supposedly setting the culture of one of the crucial “guardrail institutions” of Australian democracy.

Further allegations that have since come to light about Brereton inviting the beneficiaries of the NACC’s decision not to investigate robodebt to help edit the accompanying media statement, if true, demonstrate that Brereton’s lack of judgment is much worse than merely failing to get the balance right.

If Brereton believes leaders should foster cultures where responsibility is taken, he’d have resigned already. The fact one of his few public appearances was partially devoted to trying — unsuccessfully — to downplay and explain away findings against him should tell him that he has failed as a leader of an integrity institution.

Brereton whinged about Quentin Dempster — a bloke who’s done more for public integrity in his life than Brereton can ever hope to achieve — who suggested it was “revolver in the library” time for Brereton. To put it in a way that won’t offend Brereton’s apparently highly refined sensibility, the gods won’t be appeased until he sacrifices himself. Nor will the NACC’s reputation recover.

A clever painting

David Brooks on meritocracy: Is it an improvement?

David Brooks writes like he breathes. Pretty much all the time. Too much to be sure. I listened to this 1 hour article for a while and got some of the goodies I’ve extracted below out of it, but didn’t listen to, or read the whole thing:

The most important of the [university reformers] was James Conant, the president of Harvard from 1933 to 1953. Conant looked around and concluded that American democracy was being undermined by a “hereditary aristocracy of wealth.” American capitalism, he argued, was turning into “industrial feudalism,” in which a few ultrarich families had too much corporate power. Conant did not believe the United States could rise to the challenges of the 20th century if it was led by the heirs of a few incestuously interconnected Mayflower families.

So Conant and others set out to get rid of admissions criteria based on bloodlines and breeding and replace them with criteria centered on brainpower. His system was predicated on the idea that the highest human trait is intelligence, and that intelligence is revealed through academic achievement.

By shifting admissions criteria in this way, he hoped to realize Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a natural aristocracy of talent, culling the smartest people from all ranks of society. …

It’s gotten harder to secure a good job if you lack a college degree, especially an elite college degree. When I started in journalism, in the 1980s, older working-class reporters still roamed the newsroom. Today, journalism is a profession reserved almost exclusively for college grads, especially elite ones. A 2018 study found that more than 50 percent of the staff writers at The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal had attended one of the 34 most elite universities or colleges in the nation. A broader study, published in Nature this year, looked at high achievers across a range of professions—lawyers, artists, scientists, business and political leaders—and found the same phenomenon: 54 percent had attended the same 34 elite institutions. The entire upper-middle-class job market now looks, as the writer Michael Lind has put it, like a candelabrum: “Those who manage to squeeze through the stem of a few prestigious colleges and universities,” Lind writes, “can then branch out to fill leadership positions in almost every vocation.”

When Lauren Rivera, a sociologist at Northwestern, studied how elite firms in finance, consulting, and law select employees, she found that recruiters are obsessed with college prestige, typically identifying three to five “core” universities where they will do most of their recruiting—perhaps Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. Then they identify five to 15 additional schools—the likes of Amherst, Pomona, and Berkeley—from which they will more passively accept applications. The résumés of students from other schools will almost certainly never even get read.

“Number one people go to number one schools” is how one lawyer explained her firm’s recruiting principle to Rivera. That’s it, in a sentence: Conant’s dream of universities as the engines of social and economic segregation has been realized.

Conant’s reforms should have led to an American golden age. The old WASP aristocracy had been dethroned. A more just society was being built. Some of the fruits of this revolution are pretty great. Over the past 50 years, the American leadership class has grown smarter and more diverse. Classic achiever types such as Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Jamie Dimon, Ketanji Brown Jackson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Pete Buttigieg, Julián Castro, Sundar Pichai, Jeff Bezos, and Indra Nooyi have been funneled through prestigious schools and now occupy key posts in American life. The share of well-educated Americans has risen, and the amount of bigotry—against women, Black people, the LGBTQ community—has declined. Researchers at the University of Chicago and Stanford … concluded that up to two-fifths of America’s increased prosperity during that time can be explained by better identification and allocation of talent.

And yet it’s not obvious that we have produced either a better leadership class or a healthier relationship between our society and its elites. Generations of young geniuses were given the most lavish education in the history of the world, and then decided to take their talents to finance and consulting. For instance, Princeton’s unofficial motto is “In the nation’s service and the service of humanity”—and yet every year, about a fifth of its graduating class decides to serve humanity by going into banking or consulting or some other well-remunerated finance job.

Forgotten creeds from the summer of 2020

A piece about the ideological madness of the summer of George Floyd. I remember when the director of the school I’m a visitor to at King's College London calling for widespread reflection at Kings about how they’d been part of oppression of minorities and had to try harder. This because some cops had murdered a black guy on the tele in the US.

The first time I heard somebody recite a land acknowledgment was at a symposium in Edmonton. The year was 2014. The speaker, one of the literature professors who organized the event, acknowledged the claims of various groups of indigenous people to the land on which the University of Alberta was built. I think he mentioned the Cree, Blackfoot, and Métis nations, among others.

My first thought was: interesting. My second thought, almost simultaneous with the first, was: unserious.

How did I know the speaker wasn’t serious? I didn’t have to investigate what was in his heart. I didn’t have to study the history of the province. It was enough to know this: if he were serious about the claims to the land, he wouldn’t be working at the University of Alberta. And if the university were serious about the claims, it would set up shop somewhere else.

The land acknowledgment was similar to the letter of introduction from the fictional character Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice. Mr. Collins apologizes to the Bennet family for being heir to the estate that the Bennet daughters will therefore not inherit. The unseriousness of his apology is immediately apparent to Elizabeth and her father.

“And what can he mean by apologizing for being next in the entail? -- We cannot suppose he would help it, if he could. Can he be a sensible man, sir?”

“No, my dear; I think not. I have great hopes of finding him quite the reverse. There is a mixture of servility and self-importance in his letter, which promises well.”

Mr. Collins is not seriously acknowledging the claims of the Bennets to the land. “Quite the reverse.” He’s seriously going to inherit and occupy the estate. What does he mean when he apologizes to Mr. Bennet for “being the means of injuring your amiable daughters”? Maybe he wants to accept his inheritance graciously, proving that he is the kind of gentlemanlike man who deserves to inherit an old country house. Or maybe the apology is just cheaper than giving up the inheritance. By the same token, the apology doesn’t look like grace; it looks like “servility and self-importance.”

The statements against the racism of academic departments at Pomona College issued by the same departments in the summer of 2020 were unserious in the same way. If the professors who signed the statements believed what they said about the work to which they had dedicated their lives, they would have chosen different lives. Their actual choices were premised on the idea that teaching linear algebra (for example) to undergrads, even to black undergrads, was not a form of antiblackness. …

The economics department made a series of deeply ambiguous promises.

Looking inward, as we move forward with renewed urgency in addressing issues of economic justice, we re-commit ourselves:

• In working with formal models, to make clear that abstractions such as markets and capitalism are embedded in and affected by systems of power, inequality and racism;

• In formulating and interpreting empirical work, to be mindful of hypotheses stemming from analyses centered on systems of power, inequality, and racism;

• In the treatment of our discipline, remember that the focus on positive economics and getting the “objective” facts right can stifle important normative discussions . . .

According to one interpretation, they were promising to change the fundamental practices of their research -- “working with formal models,” “formulating and interpreting empirical work,” “getting the ‘objective’ facts right” -- so they could “move forward with renewed urgency in addressing issues of economic justice.” Possibly they were going to rename themselves “department of economic justice” rather than “economics.” Possibly they were promising to change the very object of their study, to cross out “scarcity” and write “justice.” Or, alternatively, they might have been listing the tradeoffs involved in doing what they had always done, and promising to remember them. For example, when they focused on “getting the ‘objective’ facts right,” they were necessarily electing to “stifle important normative discussions,” because it was more important to get the facts right than to tell people how to be good, because they lacked expertise in how to be good, and because no one wanted to hear from them how to be good. …

Earlier I said these statements were promptly forgotten, but that isn’t quite right. I mean, it’s probably true that no one -- almost no one -- thinks about the wave of departmental statements against racism from the summer of 2020. But everyone remembers the price we paid for issuing those statements.

And the price wasn’t cheap! Think of the price paid by Professor Hudlicky, whose article was depublished, and whose reputation was marred by vague and therefore unanswerable intimations of racism.

Then there’s the price paid by [the chemistry journal] Angewandte Chemie. Everyone knows the editors don’t stand by their authors. They don’t respect the results of peer review. They depublished an article -- not for demonstrated plagiarism or academic fraud, but in response to social pressure. …

That is the price paid by all professors who sign such statements. Rather than acquiring a moral authority that no one wants to give us, we confuse ourselves, we gain a reputation for moral confusion, and we pay for it with our actual authority.

The Shrieking of Bats

While they whizz through the air in the twilight, hither

and thither, they shriek out loud, but their shrieks are

heard only by their own kind. Treetops and barns, decrepit

steeples, throw back an echo which they hear in their flight

and which tells them what obstacles are looming in front

and when the way is open. If you deprive them of their

voices, they cannot find their way any more; everywhere

colliding with things and flying against walls, they fall

dead to the ground. Without them there is an overwhelming

increase of what they normally destroy: vermin.

GÜNTER KUNERT. A little more explanation is here.

Waiting to enter the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square

Some fun from John Kay

I’ve been reading (actually listening to) John Kay’s The Corporation of the 21st century. These two passages are from Chapter 25 on bureaucracy.

In 1944 the US Office for Strategic Services (the precursor of the CIA) produced a ‘sabotage manual’ to advise people in occupied European states on how to obstruct the conduct of the war with little personal risk.5 Suggestions included:

Insist on doing everything through ‘channels’. Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.

Make ‘speeches’. Talk as frequently as possible, and at great length. Illustrate your ‘points’ by long anecdotes and accounts of personal experiences.

When possible, refer all matters to committees, for ‘further study and consideration’. Attempt to make the committee as large as possible – never less than five.

Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible.

Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.

Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open the question of the advisability of that decision.

Advocate ‘caution’. Be ‘reasonable’ and urge your fellow-conferees to be ‘reasonable’ and avoid haste which might result in embarrassments or difficulties later on.

Many readers, especially academic ones, will be able to testify to the continuing effectiveness of these techniques even in peacetime.

And another passage:

Arnold Weinstock was one of the most effective British managers of his generation. In 1968 his company, GEC, acquired its sclerotic rival, English Electric. On completing the takeover, Weinstock observed that ‘administrative, commercial and similar overheads are uniformly too high throughout the group’. A letter he wrote to the executives of English Electric set out a new approach:

Our philosophy of personal responsibility makes it completely unnecessary for you to spend time at meetings of subsidiary boards or of standing committees. Therefore all standing committees are by this direction disbanded and subsidiary boards will not need to meet again except perhaps for statutory purposes once a year. If you wish to confer with colleagues by all means do so; even set up again any committee you and the other members feel you must have for the good of the business. But remember that you will be held personally accountable for any decision taken affecting your operating unit and also remember that you are not obliged to join any such gathering. Incidentally, on this matter of personal responsibility, prior permission from HQ is required for any proposal to employ management consultants.

This letter should be on the desks of business executives but especially those of university administrators, hospital managers and civil servants. Meetings, both formal and informal, are essential to cooperative activity. But there is an important difference between the meeting that occurs to exchange information and agree on actions and the meeting that takes place because it is 2:30pm on the second Wednesday of the month and it is your turn to serve on the Procrastination Committee.

And I picked up this bon mot from the book

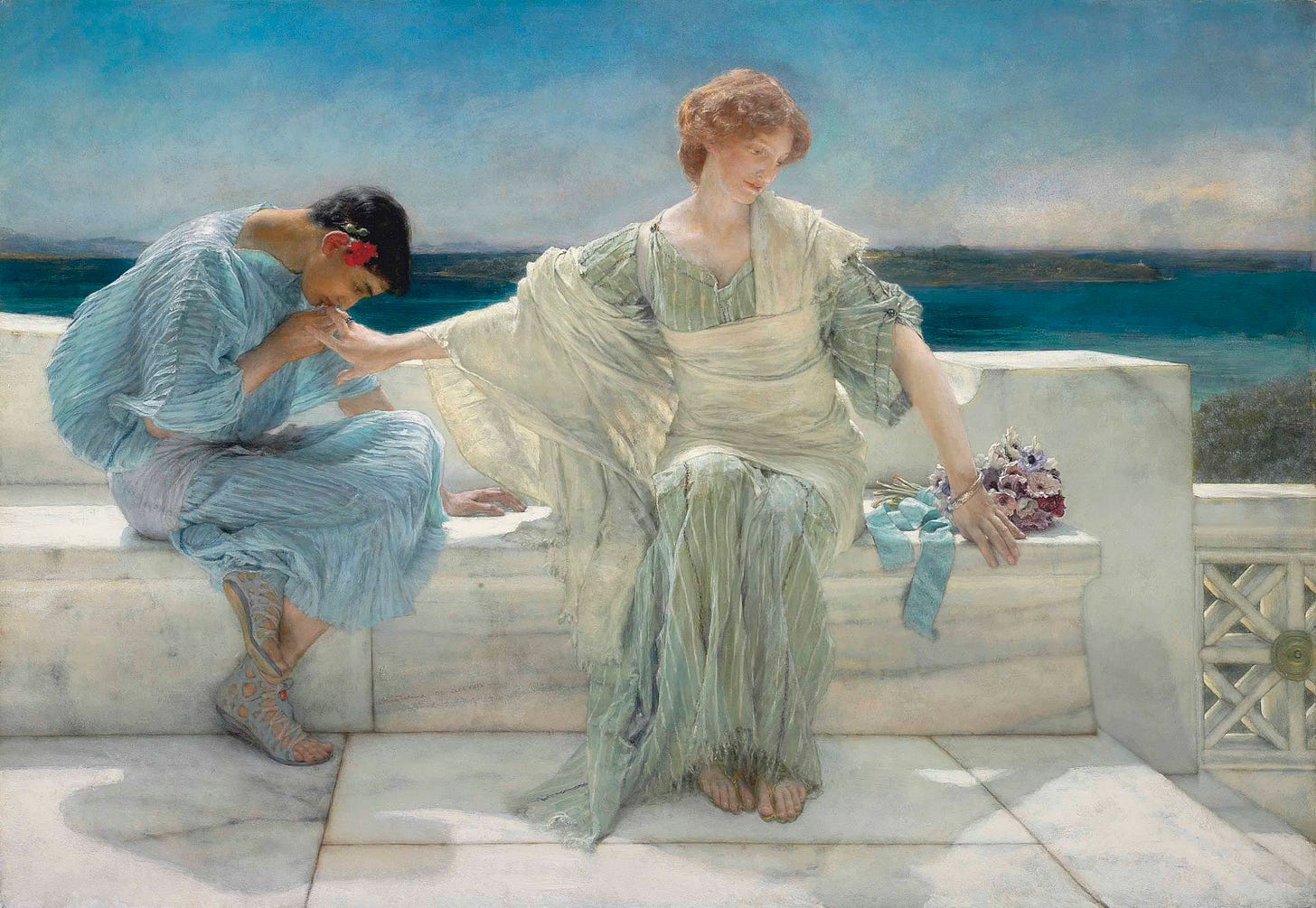

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

The art of lolling about (in Technicolor)

Or by podcast

Isabella Webber on inflation

Paul Krugman wasn’t impressed with Isabella Webber’s ideas about inflation, until he checked them out more carefully … and graciously apologised (See below). In any event here’s Webber’s latest. As I’ll outline in a subsequent newsletter, the recipe she gives of governments being traders of last resort in critical commodities — selling into rising markets and buying from falling ones was first articulated in the 7th century BCE Chinese Guanzi. She tracks this doctrine into the story of her terrific book How China Escaped Shock Therapy.

Unemployment weakens governments. Inflation kills them. That’s what a government official from Brazil once told me. But in rich countries including the United States, the politically destructive power of inflation had been forgotten. Standard policy tools left us unprepared and the Biden administration was slow to fight back. The re-election of Donald Trump should serve as a warning to democratic governments.

In this age of overlapping emergencies — hurricanes, an Avian flu outbreak, two regional wars — threats to supply chains are becoming commonplace. Each threat brings the risk of inflation and its power to destabilize governments, including our own. With such emergencies being the new normal, if we learned anything from last week’s earthquake election result, it's that we need new means of protecting our society and democracy.

Among the biggest problems that need fixing: Many business sectors today are dominated by large corporations that can profit from these one-time events.

Using A.I. and natural language processing in an upcoming paper, several co-authors and I analyzed more than 130,000 earnings calls of publicly listed U.S. companies and found that businesses can coordinate price hikes around cost shocks. This enabled companies, by and large, to pass on or amplify the impact of the initial cost increase in response to shocks in the wake of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine.

In other words, the sudden news of cost shocks, like the onset of a pandemic and war, grants companies more freedom to coordinate price hikes across sectors because they realize that their rivals are very likely going to do the same. …

In the wake of Covid, most companies managed to pass on their higher costs to the consumer and defend their margins, while some even increased them. But even if they simply keep their profit margins in response to a cost shock, their [dollar] profits increase. …

Massive shocks can be even better news for the sectors directly hit. Take oil. When demand collapsed overnight because people stayed home during the shutdowns, fossil fuel companies, suddenly faced with an unprecedented collapse in demand, closed some of their highest-cost oil fields and refineries. When demand recovered, the result was a shortage that led to record-high margins. …

Working people suffer through no fault of their own. Even if their wages eventually catch up, they are squeezed and feel cheated in the first place. This is why sellers’ inflation deepens economic inequality and political polarization, which are already threatening democracy.

President Biden mobilized a few unconventional measures to fight inflation, including an antitrust renewal to address outsize corporate power and increasing oil supply by drawing down the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. These actions were an important departure from old orthodoxies, but were ad hoc and retroactive. The main policy tool remained increasing interest rates. Sharp rate increases deepened the housing crisis, exacerbated the debt crisis for developing countries and increased the costs of investments urgently needed to address the climate crisis.

Economic stabilization used to be part of the disaster preparedness toolbox. It is time we add it back in. Just as it was recognized that some banks were too big to fail after the global financial crisis, we have to recognize that some other sectors are “too essential to fail.” In essential sectors, we need to move from a pure efficiency logic to strategic redundancies. This requires policy interventions.

Ports and other critical infrastructure should have spare capacity and a well-paid work force large enough to ramp up activity when needed. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a publicly owned buffer stock of oil, should be employed systematically to buy when prices collapse and sell when prices explode to avoid price extremes. It should buy oil on the open market when demand is falling short, thus preventing prices from collapsing, and sell oil when there is a threat of short supply, thus preventing prices from exploding. Such countercyclical purchases and sales by buffer stocks in commodity markets operate on the same logic as central banks’ open market operations in money markets.

It is not enough to release oil when prices spiral upward. As we have learned during the pandemic, a collapse in prices can create a sudden reduction in production capacity that breeds price spikes when demand picks back up.

Another lesson is that where markets are global, it is a good idea to coordinate stabilizing measures internationally — as the International Energy Agency did for its member states. And where futures markets exist, buffer stocks can buy futures when prices fall and sell when they rise for stabilization.

Countercyclical price stabilization through buffer stocks is important beyond oil. We also need it for critical minerals to encourage investments in the green supply chain and for food staples like grains, to avoid violent commodity price fluctuations in the wake of extreme weather events.

In addition to buffering essentials, we need policies that align public and private interests with resilience. As long as corporations see profits go up thanks to threats of shortages in times of disaster, we cannot assume that they prepare for emergencies in the best interest of the public. Price-gouging laws and windfall-profit taxes are relevant policy tools here.

Of course, the main task remains tackling the root causes of the emergencies. But this is a momentous task, especially in our climate change era, and in the interim a systemic set of buffers, regulations and emergency legislation is necessary. Without this economic disaster preparedness, people’s livelihoods and the outcome of elections remain at the whim of the next shock.

Heaviosity half hour

Alasdair MacIntyre and characters (and character)

Tanner Greer launches into an interesting excursus based on Paul Graham’s identification of the ‘character’ of different cities.

It makes the point of how communal thinking is. But note how all these qualities are technical ones. None speak to ethos or character. This puts me in mind of Alasdair MacIntyre’s critique of modernity in After Virtue — his idea that the ethos of an epoch and a civilisation is captured in its exemplary characters.

Go here for Tanner’s essay, with lashings of Graham’s essay.

Meanwhile here’s MacIntyre’s After Virtue on how characters embody the ethos of a time and place. What characters enjoy the same status today? Billionaires I guess.

Chapter 3

Emotivism: Social Content and Social Context

A moral philosophy—and emotivism is no exception—characteristically presupposes a sociology. For every moral philosophy offers explicitly or implicitly at least a partial conceptual analysis of the relationship of an agent to his or her reasons, motives, intentions and actions, and in so doing generally presupposes some claim that these concepts are embodied or at least can be in the real social world. Even Kant, who sometimes seems to restrict moral agency to the inner realm of the noumenal, implies otherwise in his writings on law, history and politics. Thus it would generally be a decisive refutation of a moral philosophy to show that moral agency on its own account of the matter could never be socially embodied; and it also follows that we have not yet fully understood the claims of any moral philosophy until we have spelled out what its social embodiment would be. Some moral philosophers in the past, perhaps most, have understood this spelling out as itself one part of the task of moral philosophy. So, it scarcely needs to be said, Plato and Aristotle, so indeed also Hume and Adam Smith; but at least since Moore the dominant narrow conception of moral philosophy has ensured that the moral philosophers could ignore this task; as notably do the philosophical proponents of emotivism. We therefore must perform it for them.

What is the key to the social content of emotivism? It is the fact that emotivism entails the obliteration of any genuine distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative social relations. Consider the contrast between, for example, Kantian ethics and emotivism on this point. For Kant—and a parallel point could be made about many earlier moral philosophers—the difference between a human relationship uninformed by morality and one so informed is precisely the difference between one in which each person treats the other primarily as a means to his or her ends and one in which each treats the other as an end. To treat someone else as an end is to offer them what I take to be good reasons for acting in one way rather than another, but to leave it to them to evaluate those reasons. It is to be unwilling to influence another except by reasons which that other he or she judges to be good. It is to appeal to impersonal criteria of the validity of which each rational agent must be his or her own judge. By contrast, to treat someone else as a means is to seek to make him or her an instrument of my purposes by adducing whatever influences or considerations will in fact be effective on this or that occasion. The generalizations of the sociology and psychology of persuasion are what I shall need to guide me, not the standards of a normative rationality.

If emotivism is true, this distinction is illusory. For evaluative utterance can in the end have no point or use but the expression of my own feelings or attitudes and the transformation of the feelings and attitudes of others. I cannot genuinely appeal to impersonal criteria, for there are no impersonal criteria. I may think that I so appeal and others may think that I so appeal, but these thoughts will always be mistakes. The sole reality of distinctively moral discourse is the attempt of one will to align the attitudes, feelings, preference and choices of another with its own. Others are always means, never ends.

What then would the social world look like, if seen with emotivist eyes? And what would the social world be like, if the truth of emotivism came to be widely presupposed? The general form of the answer to these questions is now clear, but the social detail depends in part on the nature of particular social contexts; it will make a difference in what milieu and in the service of what particular and specific interests the distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative social relationships has been obliterated. William Gass has suggested that it was a principal concern of Henry James to examine the consequences of the obliteration of this distinction in the lives of a particular kind of rich European in The Portrait of a Lady (Gass 1971, pp. 181–90), that the novel turns out to be an investigation, in Gass’s words, ‘of what it means to be a consumer of persons, and of what it means to be a person consumed’. The metaphor of consumption acquires its appropriateness from the milieu; James is concerned with rich aesthetes whose interest is to fend off the kind of boredom that is so characteristic of modern leisure by contriving behavior in others that will be responsive to their wishes, that will feed their sated appetites. Those wishes may or may not be benevolent, but the distinction between characters who entertain themselves by willing the good of others and those who pursue the fulfilment of their desires without a concern for any good but their own—the difference in the novel between Ralph Touchett and Gilbert Osmond—is not as important to James as the distinction between a whole milieu in which the manipulative mode of moral instrumentalism has triumphed and one, such as the New England of The Europeans, of which this was not true. James was of course, at least in The Portrait of a Lady, concerned with only one restricted and carefully identified social milieu, with a particular kind of rich person at one particular time and place. But that does not at all diminish the importance of his achievement for this enquiry. It will in fact turn out that The Portrait of a Lady has a key place within a long tradition of moral commentary, earlier members of which are Diderot’s Le Neveu de Rameau and Kierkegaard’s Enten-Eller. The unifying preoccupation of that tradition is the condition of those who see in the social world nothing but a meeting place for individual wills, each with its own set of attitudes and preferences and who understand that world solely as an arena for the achievement of their own satisfaction, who interpret reality as a series of opportunities for their enjoyment and for whom the last enemy is boredom. The younger Rameau, Kierkegaard’s ‘A’ and Ralph Touchett put this aesthetic attitude to work in very different environments, but the attitude is recognizably the same and even the environments have something in common. They are environments in which the problem of enjoyment arises in the context of leisure, in which large sums of money have created some social distance from the necessity of work. Ralph Touchett is rich, ‘A’ is comfortably off, Rameau is a parasite upon his rich patrons and clients. This is not to say that the realm of what Kierkegaard called the aesthetic is restricted to the rich and to their close neighbors; the rest of us often share the attitudes of the rich in fantasy and aspiration. Nor is it to say that the rich are all Touchetts or Osmonds or ‘A’s. But it is to suggest that if we are to understand fully the social context of that obliteration of the distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative social relationships which emotivism entails, we ought to consider some other social contexts too.

One which is obviously important is that provided by the life of organizations, of those bureaucratic structures which, whether in the form of private corporations or of government agencies, define the working tasks of so many of our contemporaries. One sharp contrast with the lives of the aesthetic rich secures immediate attention. The rich aesthete with a plethora of means searches restlessly for ends on which he may employ them; but the organization is characteristically engaged in a competitive struggle for scarce resources to put to the service of its predetermined ends. It is therefore a central responsibility of managers to direct and redirect their organizations’ available resources, both human and non-human, as effectively as possible toward those ends. Every bureaucratic organization embodies some explicit or implicit definition of costs and benefits from which the criteria of effectiveness are derived. Bureaucratic rationality is the rationality of matching means to ends economically and efficiently.

This familiar—perhaps by now we may be tempted to think overfamiliar—thought we owe originally of course to Max Weber. And it at once becomes relevant that Weber’s thought embodies just those dichotomies which emotivism embodies, and obliterates just those distinctions to which emotivism has to be blind. Questions of ends are questions of values, and on values reason is silent; conflict between rival values cannot be rationally settled. Instead one must simply choose—between parties, classes, nations, causes, ideals. Entscheidung plays the part in Weber’s thought that choice of principles plays in that of Hare or Sarte. ‘Values’, says Raymond Aron in his exposition of Weber’s view, ‘are created by human decisions . . .’ and again he ascribes to Weber the view that ‘each man’s conscience is irrefutable’ and that values rest on ‘a choice whose justification is purely subjective’ (Aron 1967, pp. 206–10 and p. 192). It is not surprising that Weber’s understanding of values was indebted chiefly to Nietzsche and that Donald G. Macrae in his book on Weber (1974) calls him an existentialist; for while he holds that an agent may be more or less rational in acting consistently with his values, the choice of any one particular evaluative stance or commitment can be no more rational than that of any other. All faiths and all evaluations are equally non-rational; all are subjective directions given to sentiment and feeling. Weber is then, in the broader sense in which I have understood the term, an emotivist and his portrait of a bureaucratic authority is an emotivist portrait. The consequence of Weber’s emotivism is that in his thought the contrast between power and authority, although paid lip-service to, is effectively obliterated as a special instance of the disappearance of the contrast between manipulative and non-manipulative social relations. Weber of course took himself to be distinguishing power from authority, precisely because authority serves ends, serves faiths. But, as Philip Rieff has acutely noted, ‘Weber’s ends, the causes there to be served, are means of acting; they cannot escape service to power’ (Rieff 1975, p. 22). For on Weber’s view no type of authority can appeal to rational criteria to vindicate itself except that type of bureaucratic authority which appeals precisely to its own effectiveness. And what this appeal reveals is that bureaucratic authority is nothing other than successful power.

Weber’s general account of bureaucratic organizations has been subjected to much cogent critcism by sociologists who have analyzed the specific character of actual bureaucracies. It is therefore relevant to note that there is one area in which his analysis has been vindicated by experience and in which the accounts of many sociologists who take themselves to have repudiated Weber’s analysis in fact reproduce it. I am referring precisely to his account of how managerial authority is justified in bureaucracies. For those modern sociologists who have put in the forefront of their accounts of managerial behavior aspects ignored or underemphasized by Weber’s—as, for example, Likert has emphasized the manager’s need to influence the motives of his subordinates and March and Simon his need to ensure that those subordinates argue from premises which will produce agreement with his own prior conclusions—have still seen the manager’s function as that of controlling behavior and suppressing conflict in such a way as to reinforce rather than to undermine Weber’s account of managerial justification. Thus there is a good deal of evidence that actual managers do embody in their behavior this one key part of the Weberian conception of bureaucratic authority, a conception which presupposes the truth of emotivism.

The original of the character of the rich man committed to the aesthetic pursuit of his own enjoyment as drawn by Henry James was to be found in London and Paris in the last century; the original of the character of the manager portrayed by Max Weber was at home in Wilhelmine Germany; but both have by now been domesticated in all the advanced countries and more especially in the United States. The two characters may even on occasion be found in one and the same person who partitions his life between them. Nor are they marginal figures in the social drama of the present age. I intend this dramatic metaphor with some seriousness. There is a type of dramatic tradition—Japanese Noh plays and English medieval morality plays are examples—which possesses a set of stock characters immediately recognizable to the audience. Such characters partially define the possibilities of plot and action. To understand them is to be provided with a means of interpreting the behavior of the actors who play them, just because a similar understanding informs the intentions of the actors themselves; and other actors may define their parts with special reference to these central characters. So it is also with certain kinds of social role specific to certain particular cultures. They furnish recognizable characters and the ability to recognize them is socially crucial because a knowledge of the character provides an interpretation of the actions of those individuals who have assumed the character. It does so precisely because those individuals have used the very same knowledge to guide and to structure their behavior. Characters specified thus must not be confused with social roles in general. For they are a very special type of social role which places a certain kind of moral constraint on the personality of those who inhabit them in a way in which many other social roles do not. I choose the word ‘character’ for them precisely because of the way it links dramatic and moral associations. Many modern occupational roles—that of a dentist or that of a garbage collector, for example—are not characters in the way that that of a bureaucratic manager is; many modern status roles—that of a retired member of the lower middle class, for example—are not characters in the way that that of the modern leisured rich person is. In the case of a character role and personality fuse in a more specific way than in general; in the case of a character the possibilities of action are defined in a more limited way than in general. One of the key differences between cultures is in the extent to which roles are characters; but what is specific to each culture is in large and central part what is specific to its stock of characters. So the culture of Victorian England was partially defined by the characters of the Public School Headmaster, the Explorer and the Engineer; and that of Wilhelmine Germany was similarly defined by such characters as those of the Prussian Officer, the Professor and the Social Democrat.

Characters have one other notable dimension. They are, so to speak, the moral representatives of their culture and they are so because of the way in which moral and metaphysical ideas and theories assume through them an embodied existence in the social world. Characters are the masks worn by moral philosophies. Such theories, such philosophies, do of course enter into social life in numerous ways: most obviously perhaps as explicit ideas in books or sermons or conversations, or as symbolic themes in paintings or plays or dreams. But the distinctive way in which they inform the lives of characters can be illuminated by considering how characters merge what usually is thought to belong to the individual man or woman and what is usually thought to belong to social roles. Both individuals and roles can, and do, like characters, embody moral beliefs, doctrines and theories, but each does so in its own way. And the way in which characters do so can only be sketched by contrast with these.

It is by way of their intentions that individuals express bodies of moral belief in their actions. For all intentions presuppose more or less complex, more or less coherent, more or less explicit bodies of belief, sometimes of moral belief. So such small-scale actions as the mailing of a letter or the handing of a leaflet to a passer-by can embody intentions whose import derives from some large-scale project of the individual, a project itself intelligible only against the background of some equally large or even larger scheme of beliefs. In mailing a letter someone may be embarking on a type of entrepreneurial career whose specification requires belief in both the viability and the legitimacy of multinational corporations: in handing out a leaflet someone may be expressing his belief in Lenin’s philosophy of history. But the chain of practical reasoning whose conclusions are expressed in such actions as the mailing of a letter or the distribution of a leaflet is in this type of case of course the individual’s own; and the locus of that chain of reasoning, the context which makes the taking of each step part of an intelligible sequence, is that particular individual’s history of action, belief, experience and interaction.

Contrast the quite different way in which a certain type of social role may embody beliefs so that the ideas, theories and doctrines expressed in and presupposed by the role may at least on some occasions be quite other than the ideas, theories and doctrines believed by the individual who inhabits the role. A Catholic priest in virtue of his role officiates at the mass, performs other rites and ceremonies and takes part in a variety of activities which embody or presuppose, implicitly or explicitly, the beliefs of Catholic Christianity. Yet a particular ordained individual who does all these things may have lost his faith and his own beliefs may be quite other than and at variance with those expressed in the actions presented by his role. The same type of distinction between role and individual can be drawn in many other cases. A trade union official in virtue of his role negotiates with employers’ representatives and campaigns among his own membership in a way that generally and characteristically presupposes that trade union goals—higher wages, improvements in working conditions and the maintenance of employment within the present economic system—are legitimate goals for the working class and that trade unions are the appropriate instruments for achieving those goals. Yet a particular trade-union official may believe that trade unions are merely instruments for domesticating and corrupting the working class by diverting them from any interest in revolution. The beliefs that he has in his mind and heart are one thing; the beliefs that his role expresses and presupposes are quite another.

There are then many cases where there is a certain distance between role and individual and where consequently a variety of degrees of doubt, compromise, interpretation or cynicism may mediate the relationship of individual to role. With what I have called characters it is quite otherwise; and the difference arises from the fact that the requirements of a character are imposed from the outside, from the way in which others regard and use characters to understand and to evaluate themselves. With other types of social role the role may be adequately specified in terms of the institutions of whose structures it is a part and the relation to those institutions of the individuals who fill the roles. In the case of a character this is not enough. A character is an object of regard by the members of the culture generally or by some significant segment of them. He furnishes them with a cultural and moral ideal. Hence the demand is that in this type of case role and personality be fused. Social type and psychological type are required to coincide. The character morally legitimates a mode of social existence.

It is, I hope, now clear why I picked the examples that I did when I referred to Victorian England and Wilhelmine Germany. The Public School Headmaster in England and the Professor in Germany, to take only two examples, were not just social roles: they provided the moral focus for a whole cluster of attitudes and activities. They were able to discharge this function precisely because they incorporated moral and metaphysical theories and claims. Moreover these theories and claims had a certain degree of complexity and there existed within the community of Public School Headmasters and within the community of Professors public debate as to the significance of their role and function: Thomas Arnold’s Rugby was not Edward Thring’s Uppingham, Mommsen and Schmöller represented very different academic stances from that of Max Weber. But the articulation of disagreement was always within the context of that deep moral agreement which constituted the character that each individual embodied in his own way.

In our own time emotivism is a theory embodied in characters who all share the emotivist view of the distinction between rational and non-rational discourse, but who represent the embodiment of that distinction in very different social contexts. Two of these we have already noticed: the Rich Aesthete and the Manager. To these we must now add a third: the Therapist. The manager represents in his character the obliteration of the distinction between manipulative and nonmanipulative social relations; the therapist represents the same obliteration in the sphere of personal life. The manager treats ends as given, as outside his scope; his concern is with technique, with effectiveness in transforming raw materials into final products, unskilled labor into skilled labor, investment into profits. The therapist also treats ends as given, as outside his scope; his concern also is with technique, with effectiveness in transforming neurotic symptoms into directed energy, maladjusted individuals into well-adjusted ones. Neither manager nor therapist, in their roles as manager and therapist, do or are able to engage in moral debate. They are seen by themselves, and by those who see them with the same eyes as their own, as uncontested figures, who purport to restrict themselves to the realms in which rational agreement is possible—that is, of course from their point of view to the realm of fact, the realm of means, the realm of measurable effectiveness.

It is of course important that in our culture the concept of the therapeu-tic has been given application far beyond the sphere of psychological medicine in which it obviously has its legitimate place. In The Triumph of the Therapeutic (1966) and also in To My Fellow Teachers (1975) Philip Rieff has documented with devastating insight a number of the ways in which truth has been displaced as a value and replaced by psychological effectiveness. The idioms of therapy have invaded all too successfully such spheres as those of education and of religion. The types of theory involved in and invoked to justify such therapeutic modes do of course vary widely; but the mode itself is of far greater social significance than the theories which matter so much to its protagonists.

I have said of characters in general that they are those social roles which provide a culture with its moral definitions; it is crucial to stress that I do not mean by this that the moral beliefs expressed by and embodied in the characters of a particular culture will secure universal assent within that culture. On the contrary it is partly because they provide focal points for disagreement that they are able to perform their defining task. Hence the morally defining character of the managerial role in our own culture is evidenced almost as much by the variety of contemporary attacks upon managerial and manipulative modes of theory and practice as it is by allegiance to them. Those who persistently attack bureaucracy effectively reinforce the notion that it is in terms of a relationship to bureaucracy that the self has to define itself. Neo-Weberian organization theorists and the heirs of the Frankfurt School unwittingly collaborate as a chorus in the theatre of the present.

I do not want to suggest of course that there is anything peculiar to the present in this type of phenomenon. It is often and perhaps always through conflict that the self receives its social definition. This does not mean however, as some theorists have supposed, that the self is or becomes nothing but the social roles which it inherits. The self, as distinct from its roles, has a history and a social history and that of the contemporary emotivist self is only intelligible as the end product of a long and complex set of developments.

Of the self as presented by emotivism we must immediately note: that it cannot be simply or unconditionally identified with any particular moral attitude or point of view (including that of those characters which socially embody emotivism) just because of the fact that its judgments are in the end criterionless. The specifically modern self, the self that I have called emotivist, finds no limits set to that on which it may pass judgment for such limits could only derive from rational criteria for evaluation and, as we have seen, the emotivist self lacks any such criteria. Everything may be criticized from whatever standpoint the self has adopted, including the self’s choice of standpoint to adopt. It is in this capacity of the self to evade any necessary identification with any particular contingent state of affairs that some modern philosophers, both analytical and existentialist, have seen the essence of moral agency. To be a moral agent is, on this view, precisely to be able to stand back from any and every situation in which one is involved, from any and every characteristic that one may possess, and to pass judgment on it from a purely universal and abstract point of view that is totally detached from all social particularity. Anyone and everyone can thus be a moral agent, since it is in the self and not in social roles or practices that moral agency has to be located. The contrast between this democratization of moral agency and the elitist monopolies of managerial and therapeutic expertise could not be sharper. Any minimally rational agent is to be accounted a moral agent; but managers and therapists enjoy their status in virtue of their membership within hierarchies of imputed skill and knowledge. In the domain of fact there are procedures for eliminating disagreement; in that of morals the ultimacy of disagreement is dignified by the title ‘pluralism’.

This democratized self which has no necessary social content and no necessary social identity can then be anything, can assume any role or take any point of view, because it is in and for itself nothing. This relationship of the modern self to its acts and its roles has been conceptualized by its acutest and most perceptive theorists in what at first sight appear to be two quite different and incompatible ways. Sartre—I speak now only of the Sartre of the thirties and forties—has depicted the self as entirely distinct from any particular social role which it may happen to assume; Erving Goffman by contrast has liquidated the self into its role-playing, arguing that the self is no more than ‘a peg’ on which the clothes of the role are hung (Goffman 1959, p. 253). For Sartre the central error is to identify the self with its roles, a mistake which carries the burden of moral bad faith as well as of intellectual confusion; for Goffman the central error is to suppose that there is a substantial self over and beyond the complex presentations of role-playing, a mistake committed by those who wish to keep part of the human world ‘safe from sociology’. Yet the two apparently contrasting views have much more in common that a first statement would lead one to suspect. In Goffman’s anecdotal descriptions of the social world there is still discernible that ghostly ‘I’, the psychological peg to whom Goffman denies substantial selfhood, flitting evanescently from one solidly role-structured situation to another; and for Sartre the self’s self-discovery is characterized as the discovery that the self is ‘nothing’, is not a substance but a set of perpetually open possibilities. Thus at a deep level a certain agreement underlies Sartre’s and Goffman’s surface disagreements; and they agree in nothing more than in this, that both see the self as entirely set over against the social world. For Goffman, for whom the social world is everything, the self is therefore nothing at all, it occupies no social space. For Sartre, whatever social space it occupies it does so only accidentally, and therefore he too sees the self as in no way an actuality.

What moral modes are open to the self thus conceived? To answer this question, we must first recall the second key characteristic of the emotivist self, its lack of any ultimate criteria. When I characterize it thus I am referring back to what we have already noticed, that whatever criteria or principles or evaluative allegiances the emotivist self may profess, they are to be construed as expressions of attitudes, preferences and choices which are themselves not governed by criterion, principle or value, since they underlie and are prior to all allegiance to criterion, principle or value. But from this it follows that the emotivist self can have no rational history in its transitions from one state of moral commitment to another. Inner conflicts are for it necessarily au fond the confrontation of one contingent arbitrariness by another. It is a self with no given continuities, save those of the body which is its bearer and of the memory which to the best of its ability gathers in its past. And we know from the outcome of the discussions of personal identity by Locke, Berkeley, Butler and Hume that neither of these separately or together are adequate to specify that identity and continuity of which actual selves are so certain.

The self thus conceived, utterly distinct on the one hand from its social embodiments and lacking on the other any rational history of its own, may seem to have a certain abstract and ghostly character. It is therefore worth remarking that a behaviorist account is as much or as little plausible of the self conceived in this manner as of the self conceived in any other. The appearance of an abstract and ghostly quality arises not from any lingering Cartesian dualism, but from the degree of contrast, indeed the degree of loss, that comes into view if we compare the emotivist self with its historical predecessors. For one way of re-envisaging the emotivist self is as having suffered a deprivation, a stripping away of qualities that were once believed to belong to the self. The self is now thought of as lacking any necessary social identity, because the kind of social identity that it once enjoyed is no longer available; the self is now thought of as criterionless, because the kind of telos in terms of which it once judged and acted is no longer thought to be credible. What kind of identity and what kind of telos were they?

In many pre-modern, traditional societies it is through his or her membership in a variety of social groups that the individual identifies himself or herself and is identified by others. I am brother, cousin and grandson, member of this household, that village, this tribe. These are not characteristics that belong to human beings accidentally, to be stripped away in order to discover ‘the real me’. They are part of my substance, defining partially at least and sometimes wholly my obligations and my duties. Individuals inherit a particular space within an interlocking set of social relationships; lacking that space, they are nobody, or at best a stranger or an outcast. To know oneself as such a social person is however not to occupy a static and fixed position. It is to find oneself placed at a certain point on a journey with set goals; to move through life is to make progress—or to fail to make progress—toward a given end. Thus a completed and fulfilled life is an achievement and death is the point at which someone can be judged happy or unhappy. Hence the ancient Greek proverb: ‘Call no man happy until he is dead.’

This conception of a whole human life as the primary subject of objective and impersonal evaluation, of a type of evaluation which provides the content for judgment upon the particular actions or projects of a given individual, is something that ceases to be generally available at some point in the progress—if we can call it such—towards and into modernity. It passes to some degree unnoticed, for it is celebrated historically for the most part not as loss, but as self-congratulatory gain, as the emergence of the individual freed on the one hand from the social bonds of those constraining hierarchies which the modern world rejected at its birth and on the other hand from what modernity has taken to be the superstitions of teleology. To say this is of course to move a little too quickly beyond my present argument; but it is to note that the peculiarly modern self, the emotivist self, in acquiring sovereignty in its own realm lost its traditional boundaries provided by a social identity and a view of human life as ordered to a given end.

Nonetheless, as I have already suggested, the emotivist self has its own kind of social definition. It is at home in—it is an integral part of—one distinctive type of social order, that which we in the so-called advanced countries presently inhabit. Its definition is the counterpart to the definition of those characters which inhabit and present the dominant social roles. The bifurcation of the contemporary social world into a realm of the organizational in which ends are taken to be given and are not available for rational scrutiny and a realm of the personal in which judgment and debate about values are central factors, but in which no rational social resolution of issues is available, finds its internalization, its inner representation in the relation of the individual self to the roles and characters of social life.

This bifurcation is itself an important clue to the central characteristics of modern societies and one which may enable us to avoid being deceived by their own internal political debates. Those debates are often staged in terms of a supposed opposition between individualism and collectivism, each appearing in a variety of doctrinal forms. On the one side there appear the self-defined protagonists of individual liberty, on the other the self-defined protagonists of planning and regulation, of the goods which are available through bureaucratic organization. But in fact what is crucial is that on which the contending parties agree, namely that there are only two alternative modes of social life open to us, one in which the free and arbitrary choices of individuals are sovereign and one in which the bureaucracy is sovereign, precisely so that it may limit the free and arbitrary choices of individuals. Given this deep cultural agreement, it is unsurprising that the politics of modern societies oscillate between a freedom which is nothing but a lack of regulation of individual behavior and forms of collectivist control designed only to limit the anarchy of self-interest. The consequences of a victory by one side or the other are often of the highest immediate importance; but, as Solzhenitzyn has understood so well, both ways of life are in the long run intolerable. Thus the society in which we live is one in which bureaucracy and individualism are partners as well as antagonists. And it is in the cultural climate of this bureaucratic individualism that the emotivist self is naturally at home.

The parallel between my treatment of what I have called the emotivist self and my treatment of emotivist theories of moral judgment—whether Stevensonian, Nietzschean or Sartrian—is now, I hope, clear. In both cases I have argued that we are confronted with what is intelligible only as the end-product of a process of historical change; in both cases I have confronted theoretical positions whose protagonists claim that what I take to be the historically produced characteristics of what is specifically modern are in fact the timelessly necessary characteristics of all and any moral judgment, of all and any selfhood. If my argument is correct we are not, although many of us have become or partly become, what Sartre and Goffman say we are, precisely because we are the last inheritors—so far—of a process of historical transformation.

This transformation of the self and its relationship to its roles from more traditional modes of existence into contemporary emotivist forms could not have occured of course if the forms of moral discourse, the language of morality, had not also been transformed at the same time. Indeed it is wrong to separate the history of the self and its roles from the history of the language which the self specifies and through which the roles are given expression. What we discover is a single history and not two parallel ones. I noted at the outset two central factors of contemporary moral utterance. One was the multifariousness and apparent incommensurability of the concepts invoked. The other was the assertive use of ultimate principles in attempts to close moral debate. To discover where these features of our discourse came from, how and why they are fashioned, is therefore an obvious strategy for my enquiry. To this task I now turn.