Must we be run by psychopaths?

That’s the question Marxist investment analyst and one of my favourite bloggers, Chris Dillow asks.

The post office scandal is not merely a matter of a few bad bosses. It should raise questions about the very structure of our society.

It's easy to say that Paula Vennells was corrupt and/or incompetent and that the Horizon system was faulty. But this is trivial. Anyone who has switched a computer on knows that software is buggy, and countless thousands of people are stupid and dishonest: you could throw a brick from your house and hit a dozen of them - more in some parts of London. A well-ordered society has mechanisms which prevent such people getting power or doing much damage if they do get it. The Post office scandal shows that we lack such mechanisms, in at least four respects:

- There's good evidence that companies actually select for psychopaths. People who are unusually concerned with status and power are precisely those who aim for the top of hierarchies (whereas many others of us just want to get on with our jobs), and psychopaths' superficial charm and fluency appeals to hirers. As David Allen Green says, "the likes of Paula Vennells are always with us and will always somehow obtain senior positions." This is consistent with a finding by Luigi Zingales and colleagues, that a lot more corporate fraud occurs than is actually detected. What's more, companies also select for over-confidence as they mistake "competence cues" - the right body language or the illusion of knowledge - for actual ability. (All this might also apply to politics).

- Ministers failed to control or to replace Post Office management, believing - in a remarkable example of not understanding the function of ownership - that it "has the commercial freedom to run its business operations without interference from the shareholder." Ed Davey distinguishes himself from the other ministers merely by being so uncouth as to have blurted this out in public.

- Police for years did not investigate the likely fraud and perversion of the course of justice by Post Office bosses. The fact that they have begun to do so since the screening of the ITV drama reminds us that the Met is more concerned with PR than with justice.

- The courts failed to acquit innocent sub-postmasters, for systemic reasons discussed by David Allen Green. This was not an isolated miscarriage of justice; it occurred over 700 times.

We should think of our main social institutions - markets, the democratic process, the legal system and so on - as selection devices. What we have here is evidence that these do not operate as you might think they should, not in one or two instances but systematically and persistently. The Post Office board and government ministers did not select honest or competent bosses. The police did not choose to investigate serious crimes. And the courts failed to correctly distinguish between the guilty and the innocent.

I’d add this.

Every modern democratic government I know of is a democratised monarchy. That is, there is a single point of sovereignty, a single head of government. A prime minister in a Westminster system, a president in a congressional one. I never gave this much thought until one day, I realised that Pericles wasn’t the prime minister of Athens. He wasn’t anything much other than one of ten generals at any one time and he was elected again and again. Beyond being one of ten generals (and there were other officials) he had no formal primacy. Likewise, the Roman Republic was assiduously built as an anti-monarchy, with every office held by two officeholders who needed to agree to exercise the power of the office fully.

Why is this important? First, in a modern democracy, the head of government usually has vast power if they want to abuse it to appoint their cronies. Scott Morrison did this with the AAT. Donald Trump has already said he’ll do it even more than last time if he manages to get into the White House again.

More fundamentally, systems of accountability reach up, in principle to a single point of sovereignty. And this system of accountability is increasingly a system of accountability theatre. And it’s all run by folks who are in some loose way part of the same system — and people who’ve been selected by others as sound chaps — like the Rev Paula Vennells who as the bodies piled up at the Post Office became non-executive board member at the Cabinet Office, chair of Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, was associatd with the NHS Care Quality Commission. In between her reverend activities, she helped out in the Church of England's Ethical Investment Advisory Group. In one of those capacities Paula no doubt helped out with other sound chaps who might have been running into a spot of bother with unruly underlings.

So what? Well there’s one institution in this pyramid of sound chaps, that has a major role — indeed it can take upon itself a veto role — but it is not part of this hierarchy. It isn’t accountable, except to itself and the consciences of its members, so it doesn’t do accountability theatre.

The jury.

That’s why we need to develop jury-like mechanisms to oversee travesties of justice like this, a jury-like body to whom folks can go if they’re being given the Robodebt treatment. Such bodies could be from sub-sections of the population, but the most important thing is that there is some process that rotates membership and makes the group representative of the population we’re trying to serve.

Woody Allen Jesus: A Masterpiece

I saw Tim Minchin’s second musical, Groundhog Day, this week. I thought it was marvellous and recommend it to anyone in Melbourne. I know the film is supposed to be a masterpiece, and Bill Murray is his usual great self. But I still got bored. I think it’s hard to sustain for a movie length and the plot became a bit contrived — but it was fine — was glad I’d seen it. Anyway, that’s just me. Everyone else thinks the movie is great, so I’d go with their view rather than my impatience. Anyway where was I? Yes, the thing is that, as Tim Minchin said, he didn’t fancy musicalising most movies, but, in the immortal words of Groucho Marx, in this case, he’d make an exception. And the American fantasy (they’re almost invariably the ones who do this kind of thing — think Genie, Mr Ed, Bewitched) is just wonderfully suited to a musical. Thanks to the star who put me onto it — and got Eva and I tickets.

Anyway, the visit to the theatre produced the predictable return home to check out more. And I stumbled onto this version of the song you can see in the video above. It’s more heavily produced and more musical in a way, but the version above brings out how truly funny it really is. And how musical. Just a remarkable thing I didn’t know about, until this week. Here’s another version which I also enjoyed and perhaps performed better than the other two — the backing singers are lovely. But the impassivity of the audience makes it much worse than the video above I think.

Ukraine, Gaza, Taiwan

I don’t like this column for various reasons. It’s grandiose. Overblown. The analogies it draws are strained. Ukraine and Gaza are very different affairs. And likening the Americans not getting their way in Ukraine, Gaza and Taiwan wouldn’t be “a geopolitical event akin to the disintegration of the Soviet Union”. Still, it does draw attention to something I’ve been thinking for a while and which is the one core of sense that Donald Trump’s been talking for his whole life. America has decided to use its vast power as a global hegemon pretty much everywhere in the world, rather than a pivotal alliance maker. Europe should be the main funder of European security. It should be the main funder of NATO, not the Americans.

The war in Ukraine should be Europe’s war. The fact that it doesn’t have the arms to fight it means that, at least in the short term, the US should sell or lease them to Europe (like it did for the UK during WWII till Pearl Harbour was attacked and Germany declared war on the US (Yes it really did that!). Instead, the US is fighting Russia. And Republicans won’t fund it. So it looks like being the usual disaster. I was also intrigued that, in arguing a strong pro-Israeli line in the podcast I included last month, Russ Roberts argued that the US should not fund Israel’s wars. Very interesting.

Anyway, the column is definitely food for thought. As is this piece from the London Review of Books.

If the US succeeds in its attempt to halt Israel’s military campaign in Gaza with Hamas still in power, and pivots to international recognition of a Palestinian state, as the US State Department has recently signalled it hopes to do, it would be impossible for either Israelis or their regional enemies to see the October 7 terror attacks, backed by Iran, as anything other than a massive Iranian victory and US-Israeli defeat.

Ukraine appears to be on a similar glide path towards military and diplomatic defeat, made in the US. While Washington has shovelled over $100 billion in military and related aid into Ukraine, it has refused to provide the Ukrainians with the offensive weapons they need to repel Putin’s offensive. As a result, the Ukrainian army has begun to bleed out, while appearing to lack any serious capacity to hit targets of military or political significance inside Russia. Come springtime, it seems likely that Putin will go on the offensive, seize the remainder of the Donbas region, and then use his overwhelming superiority in airpower and missiles to bombard Ukrainian cities until Zelenskyy shows up at the negotiating table. The likely result of such negotiations is Ukraine ceding large chunks of Ukraine to Putin, who will declare victory in the war he started in 2022.

Barring major shifts in tactics on either battlefield, both of the above scenarios, in which Iran and Putin emerge the victors, and recipients of tens of billions of dollars in US military aid and diplomatic support are the losers, seem more likely than not — and no amount of blather will be able to disguise them, especially during the upcoming US election season. Israel’s ties to the Gulf States will evaporate, as their oil-rich kingdoms seek to cut deals with Iran in the hope of protecting themselves from another October 7 on their own soil, while the goal of wiping Israel off the map will seem plausible again to a new generation of poverty-stricken young Arabs in shattered countries like Syria, Iraq, Libya and Egypt. A similar dynamic will likely take hold in Europe, where Germany and other EU states will be incentivised to cut deals with Putin at the expense of their smaller, weaker Eastern neighbours. In both regions, America will cease to function as the local hegemon.

But the bad news hardly stops there. Seeing major US military allies in Europe and the Middle East defeated, Chinese military planners may spy an excellent opportunity to blockade Taiwan, or even invade the island, and then dare the US to evict them. Having already lost two major proxy wars — and being unlikely to risk direct military confrontation with China in her own backyard — it seems safe to predict that the US would decline to fight.

Taken together, these near-simultaneous defeats would be a setback of an entirely different order from the botched US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, or even the collapse of America’s fantastical nation-building enterprise in Iraq. Yet the most frightening thing about the above scenario is not the fact that each component of the catastrophe seems plausible enough, but that all three of these likely disasters is the product of an Alice-in-Wonderland approach to reality that defines America’s global vision. In each case, the defeats of key American proxies over the next 12 months can be understood as the products of tactical failures rooted in failed US military doctrine, which is in turn grounded in strategic choices and assumptions that have proven to be wildly delusional and yet stubbornly and mystifyingly resistant to change.

Minister’s speeches

I always wonder why Minister’s speeches are a drawcard. They’re invariably lists of platitudes and lists of the Government’s achievements usually communicated in a way that makes it impossible to know if they are achievements. You know “We spent $3,500 billion on this or that” while leaving you without any clear benchmark to compare it to.

And then there are speeches by Andrew Leigh. This one’s to the Australasian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society and so it’s about “Using Artificial Intelligence For Economic Research”.

My favourite example of how AI can boost productivity comes from a large randomised trial involving 758 BCG management consultants (7 percent of the company’s global workforce), carried out by Fabrizio Dell’Acqua and coauthors (Dell'Acqua et al 2023). The researchers asked consultants to do various tasks for a fictional shoe company. There were creative tasks (“Propose at least 10 ideas for a new shoe targeting an underserved market or sport.”), analytical tasks (“Segment the footwear industry market based on users.”), writing and marketing tasks (“Draft a press release marketing copy for your product.”), and persuasiveness tasks (“Pen an inspirational memo to employees detailing why your product would outshine competitors.”).

Half the consultants were asked to do the tasks as normal, while the other half were asked to use ChatGPT. Those who were randomly selected to use artificial intelligence were not just better – they were massively better. Consultants using AI completed tasks 25 percent faster, and produced results that were 40 percent higher quality. That’s like the kind of difference you might expect to see between a new hire and an experienced staff member.

The researchers found that AI was a skill leveller. Those who scored lowest when their skills were assessed at the start of the experiment experienced the greatest gains when using AI. Top performers benefited too, but not by as much. The researchers also found instances in which they deliberately gave tasks to participants that were beyond the frontiers of artificial intelligence. In those instances, people who were randomly selected to use AI performed worse – a phenomenon that the researchers dubbed ‘falling asleep at the wheel’. …

[R]rather than regaling you with high-level studies, I decided that I would take a different tack. As an economist speaking to an agricultural economics conference, I thought that the best way of making my point might be to actually demonstrate what the tools can do.

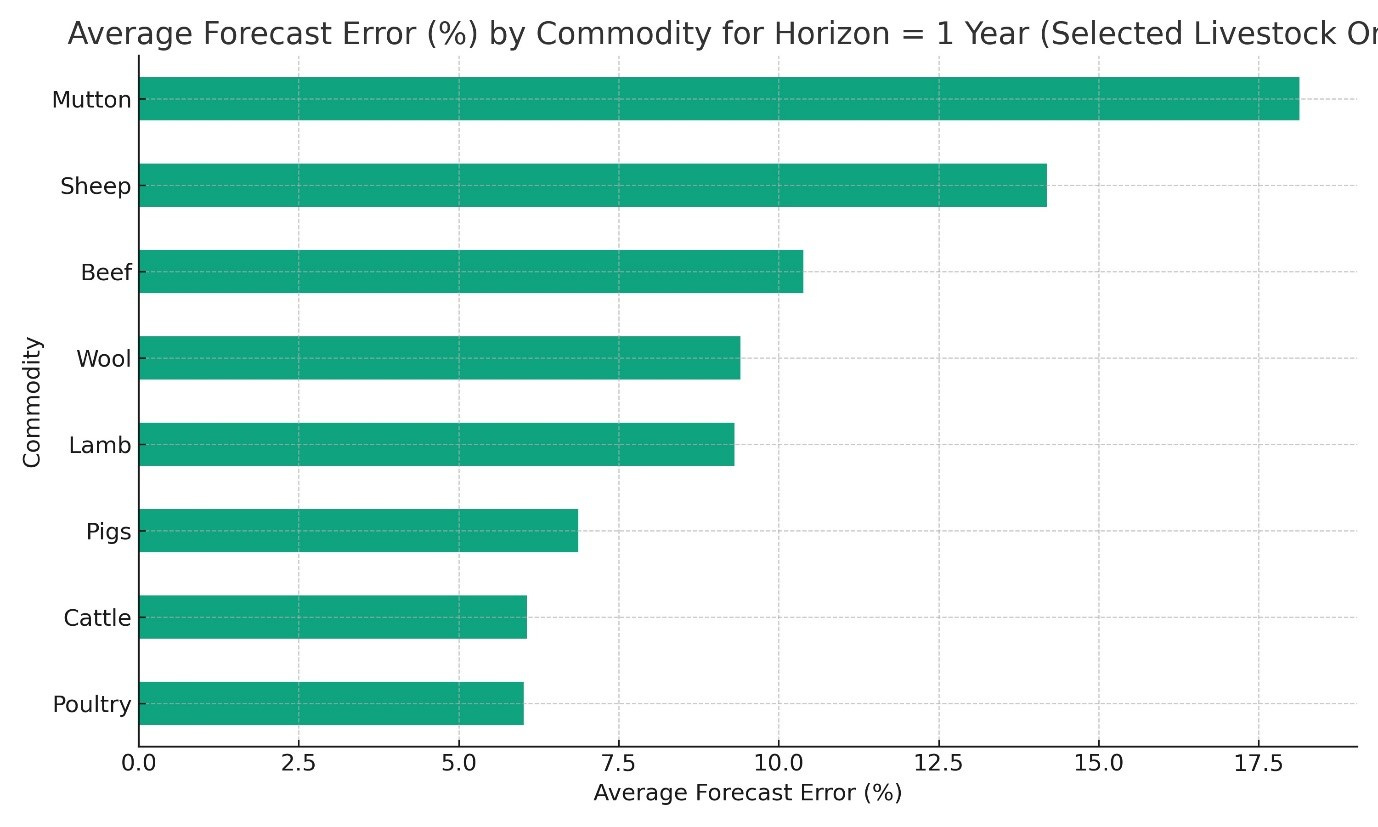

To start, I logged on to the ABARES site, and downloaded the Historical Agricultural Forecast Database. If you haven’t played around with it before, this is an impressive database, containing tens of thousands of forecasts for different agricultural commodities. I uploaded it into ChatGPT4, and asked it to describe the dataset. It read the data directory and data pages together, quickly told me in plain English what each variable was, and pointed out a few notable features of the dataset, such as the fact that forecast years range from 2000 to 2022, and wheat is the most common commodity forecast.

Providing my commands in plain English, I asked it to drop forecasts for sub-regions, and create variables for the percentage error in the forecast and the forecast horizon. Then I asked it to plot forecast errors against the forecast horizon. This scatterplot, based on 14,622 observations, shows that forecasts get better as the year approaches.

Now let’s see how the forecasts compare across commodities. To keep things simple, I’ll focus from this point onwards only on forecasts that are made for the next year.

Here’s the livestock forecasts, which range from an 18 percent error in mutton forecasts to a 6 percent error in poultry forecasts. Note that this chart was produced using regular language, not by coding.

So poultry forecasters are more accurate than mutton forecasters. Perhaps you might forget that fact. So let’s ask ChatGPT to make a digital art image that helps it stick in your mind.

And so on.

The history of equality

An interesting review of what sounds like a good book

In a famous essay, the economist and philosopher Amartya Sen pointed out that we are all in favour of equality. We just disagree about whether we mean equality of money, or power, or respect, or legal standing, or whatever. The question is ‘equality of what?’ But there is an even deeper question than this: ‘equality of whom?’ Where is the line between those considered as equals and those who are not – between the fourteen and the one? …

It is easy to invoke equality without facing its limits. Contra John Lennon, it is actually very hard to imagine a world with no countries. ‘For all the high-minded talk of “global equality” in recent times’, McMahon writes, ‘its contours have most often been imagined from within the walls of nation-states, where equality extends only to those who share a passport and more often than not a place of birth.’ …

There’s no romanticisation in these pages. Not only did hunter-gatherers kill or expel in order to maintain order, they also formed hierarchies. Or rather, hierarchies formed them. McMahon insists that hierarchies are everywhere in human history, just as they exist in every primate community. Human beings ‘cannot live without hierarchies’, he writes, since ‘status is part of the air we breathe’. …

But at the same time, religion in general (and Christianity in particular) has been among the most propulsive forces for equality in the last two millennia. Both Jews and Christians learn that each of us is made in the image of God. Early Christians lived essentially as communists, while Early Church leaders, following Christ’s example, were outspoken critics of the wealthy. St Basil the Great, for example, told his fourth-century congregation in Caesarea that ‘the more you abound in wealth, the more you lack in love’ and that a rich person who failed to help a poor person was a ‘murderer’. …

While it is clear that for much of modern history the Church has not been a good advertisement for equality, it is also clear that much modern egalitarian thinking rests on theological foundations. As McMahon writes of 18th-century reform efforts, ‘The very fact that equality was on the horizon at all owed much to these varied Christian efforts. Over the course of centuries, Christians had made of equality a moral good, investing it with a sacral status … Equal was how God had made us; equal was how God intended his beloved to be.’ …

The Roman Empire in which Christianity flourished had its own abstract ideal of equality under natural law for all male Roman citizens … a principle that became part of the legal code itself under Emperor Justinian. McMahon distils the partnership between secular and religious forces: ‘Thus did the Roman law and Christian theology work together, each in its own way, to situate equality amid inequality, while concealing inequality in equality itself. The one justified the other. And as both the empire of Christianity and the empire of Rome grew, so did that complementary and reinforcing function.’ …

The rancour of modern politics is an obstacle to the practical pursuit of greater equality. Right-wing nationalists are dusting off the playbooks of the 1920s and 1930s, whether they admit it (or even know it) or not. In the face of growing concerns over immigration, the proto-fascist French thinker Maurice Barrès wrote at the end of the 19th century, ‘the idea of the fatherland implies an inequality, but to the detriment of foreigners, not, as is the case today, to the detriment of French nationals.’ Meanwhile, too many on the Left are practising a rancorous identity politics of their own, in which, as McMahon writes, ‘white heterosexual men are cast as uncertain allies and privileged exceptions to the rest of humanity’.

There is some hard politics ahead of us, for sure. If we are to stand any chance of cultivating a humane reimagining of equality, we will have to do some hard thinking too.

More movement in the lava lamp of social media

From The Economist:

The weird magic of online social networks was to combine personal interactions with mass communication. Now this amalgam is splitting in two again. Status updates from friends have given way to videos from strangers that resemble a hyperactive tV. Public posting is increasingly migrating to closed groups, rather like email. What Mr Zuckerberg calls the digital “town square” is being rebuilt—and posing problems.

This matters, because social media are how people experience the internet. Facebook itself counts more than 3bn users. Social apps take up nearly half of mobile screen time, which in turn consumes more than a quarter of waking hours. They gobble up 40% more time than they did in 2020, as the world has gone online. As well as being fun, social media are the crucible of online debate and a catapult for political campaigns. In a year when half the world heads to the polls, politicians from Donald Trump to Narendra Modi will be busy online.

The striking feature of the new social media is that they are no longer very social. Inspired by TikTok, apps like Facebook increasingly serve a diet of clips selected by artificial intelligence according to a user’s viewing behaviour, not their social connections. Meanwhile, people are posting less. The share of Americans who say they enjoy documenting their life online has fallen from 40% to 28% since 2020. Debate is moving to closed platforms, such as WhatsApp and Telegram.

The lights have gone out in the town square. Social media have always been opaque, since every feed is different. But TikTok, a Chinese-owned video phenomenon, is a black box to researchers. Twitter, rebranded as X, has published some of its code but tightened access to data about which tweets are seen. Private messaging groups are often fully encrypted.

Some of the consequences of this are welcome. Political campaigners say they have to tone down their messages to win over private groups. A provocative post that attracts “likes” in the X bear pit may alienate the school parents’ WhatsApp group. Posts on messaging apps are ordered chronologically, not by an engagement-maximising algorithm, reducing the incentive to sensationalise. In particular, closed groups may be better for the mental health of teenagers, who struggled when their private lives were dissected in public.

In the hyperactive half of social media, behaviour-based algorithms will bring you posts from beyond your community. Social networks can still act as “echo chambers” of self-reinforcing material. But a feed that takes content from anywhere at least has the potential to spread the best ideas farthest.

Yet this new world of social-media brings its own problems. Messaging apps are largely unmoderated. For small groups, that is good: platforms should no more police direct messages than phone companies should monitor calls. In dictatorships encrypted chats save lives. But Telegram’s groups of 200,000 are more like unregulated broadcasts than conversations. Politicians in India have used WhatsApp to spread lies that would surely have been removed from an open network like Facebook.

Split UK Treasury in two: Andy Haldane

Andy Haldane suggests Solomon’s solution in this FT column. It reminds me that our Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser chopped our Treasury in two to cut it down to size. But that just created two economic departments, two streams of pointy headed briefs in the Cabinet process where there had been one. Still Andy’s ideas are a bit different, so they may not be subject to the fallacy of ‘metasticy’. Andy led the ‘levelling up’ exercise that the Silly Party Prime Minister Boris Johnson appointed.

The most powerful thing a powerful person can do is to give that power away. Power should be to politicians as money is to philanthropists; it is in the act of giving that they receive. Nowhere is that truer than when it comes to restoring growth to the UK’s stagnating economy.

Finance ministers like to play the role of magicians, producing rabbits from fiscal hats. The last Autumn Statement in the UK saw 100 bunnies produced from a single hat that, weeks earlier, was said to be empty. Unfortunately, having spotted the sleight of hand, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) revised down their projections for medium-term UK growth. To restore sustainable economic growth, the UK’s next chancellor’s … first fiscal trick should be to chop themselves, and the institution over which they preside, in half.

The most powerful and consequential act of Gordon Brown’s decade-long chancellorship came on his first day in office. That was to cede power for the setting of monetary policy to the Bank of England. In giving, he then received a golden decade of low inflation and interest rates and sustained economic growth.

Today’s conditions are less propitious, which is why the next chancellor needs to follow the Brown playbook but with greater boldness, distributing more powers to those best able to deliver sustained growth. This pro-growth strategy should have two elements, one national, one regional.

First, there should be a separation of the Treasury’s finance and economy ministry functions. The Treasury has always pursued a fiscal-first strategy, ensuring the nation’s books are balanced over the medium term to avoid funding crises. This is a crucial role and requires a singular institutional focus supported by appropriate fiscal rules. But that focus has meant policies to deliver sustained growth have played second fiddle.

The Treasury’s fiscal-first strategy has come at the expense of too little attention to growth and too little sustained public investment in the infrastructure and social capital needed to support it.

To break this cycle, growth should be given equal billing with fiscal sustainability as a policy objective. That can be achieved by creating a new economy ministry with an explicit growth mission. And to ensure growth is balanced geographically, this new economy ministry should be based at the Treasury’s new campus in Darlington. …

Existing proposals from both main UK parties, while pointing in the right direction, are incremental shifts from a heavily centralised starting point that again makes Britain an international outlier. To harvest the full fruits of local growth, power-sharing needs to be far bolder.

I see an important role for citizens assemblies in keeping local leaders’ decisions attuned to the public’s needs.

That means redrawing the terms of existing devolution deals for Wales, Scotland, London and, in time, Northern Ireland, as well as empowering the English regions. …

It would be naive to think shifting powers alone would be sufficient to kick-start UK growth. But bold governance shifts like this are necessary conditions for stirring it from its slumber. The next government, by giving power generously, could ensure it and we all receive economically in the years ahead.

Click through for some effective communication

Elenor Rigby

Malcolm Gladwell’s podcasting outfit Pushkin publishes many interesting podcasts — even if they’re a tad over-produced and repetitive. Anyway, I loved the content of this and listened to another one, which wasn’t nearly as good — but was interesting — “Back in the USSR”. But I’ll try to remember not to go back for more. In 20 minutes there were four ad breaks.

From a tweet thread of recently built churches

Correspondence from last week

Nicholas, I agree with you and Tom Friedman that Israel’s response to the Hamas attack has been a disaster not only for Palestinians but for Israel’s future existence as a Middle East nation.

From the start of the war Israel should have gone out of its way to ensure that Gazan civilians could move to a safe zone (if need be, within Israel) to escape the subsequent carpet bombing.

Over a month ago P&I published a piece where I proposed that. See https://johnmenadue.com/how-to-stop-a-gaza-apocalypse-xmas/

The world is now asking how it was possible for Israel to create an Apocalypse for Palestinians when Jews still grieve their own Holocaust. I lost an aunt in a concentration camp.

From Percy Allan

Don’t let anyone tell you galaxies are not extremely large

Heaviosity half hour

Purpose in Biology: it’s roaring back into vogue!

The story goes round among biologists everywhere that teleology is a woman of easy virtue, whom the biologist disowns in public, but lives with in private.

Michael Polanyi, 1964.

The concluding paragraph of Michael Polanyi’s Magnum Opus Personal Knowledge (1958)

Thanks to Martin Turkis (with whom I’m collaborating) for bringing this magnificent passage to my attention.

Imagine if we could have a culture that revered science and yet was mesmerised less by reductionism — the technique by which science made its early giant steps for mankind — but by that other, more meaningful aspect of reality that science and reason uncovers: the emergence of the higher from the lower.

Looking back…on the immensities of the past, we realize that all that we see there, throughout the universe, is shaped by what we now ultimately believe. We see primordial inanimate matter, the motions of which are determined—whether mechanically or statistically—by intrinsic fields of forces. We see its particles settling down into orderly configurations which our physical theories can trace back (however imperfectly) to the fundamental properties of inanimate matter. This universe is still dead, but it already has the capacity of coming to life. Can we see then all the works of the human mind invisibly inscribed already in the configuration of primeval incandescent gases? No, we cannot; for the capacity of coming to life is due to the power of a field to consolidate centres of first causes. Each such centre bears a possibility of achievement which, however limited, uncertain, and unspecifiable in its outcome, characterizes this centre as an essentially new and autonomous prime mover. The centres of individual beings are short lived, but the centres of the phylogenetic fields of which individuals are offshoots go on operating through millions of years; indeed, some of these may endure for ever—we cannot tell. But we do know that the phylogenetic centres which formed our own primeval ancestry have now produced…a life of the mind which claims to be guided by universal standards. By this act a prime cause emergent in time has directed itself at aims that are timeless… pursuing…ultimate liberation. We may envisage then a cosmic field which called forth all these centres by offering them a short-lived, limited, hazardous opportunity for making some progress of their own towards an unthinkable consummation. And that is also, I believe, how a Christian is placed when worshipping God.

Can reason survive academia?

Susan Haack’s “Can Philosophy be Saved?”

As you will discover if you read on — which I recommend — Susan Haack is not a happy camper. Not happy at all. What does philosophy (and pretty much all the social sciences) need to be saved from? What the great Charles Sanders Peirce called “sham reasoning”, or as I called it in this piece, metaphysical fairy floss. I’ve reproduced the piece in full, but also extracted a couple of ‘pull quotes’ and you could do worse than poke around from those. (Though you might be able to do better by reading it through!)

Once again—now, heaven help me, even in the pages of Free Inquiry!—I find myself “otherwise minded,” the cannibal among the missionaries. Why so? I certainly share our editor’s sense that academic philosophy is in bad shape, and his concern for the future of our discipline. But his diagnosis—that, in what he sees as a kind of culture war in our profession, the side that appeals to “awe and transcendence” seems to be winning—strikes me as way off the mark; and his prescription—that we should fight back by renewing our commitment to a philosophy informed by a policy of “strict scientific naturalism”—strikes me as more likely to aggravate our ills than to cure them.

Yes, something is rotten in the state of philosophy. I’d go so far as to say, as an unusually candid friend put it a few years ago, that our profession is “in a nose-dive.” (How far can it go? What can I say?—the sky’s the limit.)

How did this happen? Some of the problems are the result of changes in the management of universities affecting the whole academy: the burgeoning bureaucracy, the ever-increasing stress on “productivity,” the ever-spreading culture of grants-and-research-projects, the ever-growing reliance on hopelessly flawed surrogate measures of the quality of intellectual work, the obsession with “prestige,” and so on. And some of the problems are the result of changes in academic publishing: the ever-more-extensive reach of enormous, predatory presses that treat authors as fungible content-providers whose rights in their work they can gobble up and sell on, the ever-increasing intrusiveness of copy-editors dedicated to ensuring that everyone write the same deadly, deadpan academic prose, the endless demands of a time- and energy-wasting peer-review process by now not only relentlessly conventional but also, sometimes, outright corrupt, and so forth. Other problems, however, are more specific to our discipline: our decades of over-production of Ph.D.s, for example, the pressure we put on graduate students to publish while they’re still wet behind the ears, the completely artificial importance we give to “contacts” and skill in grantsmanship and, over the last decades, our craven willingness to sacrifice our own judgment in submission to the ranking gods of the PGR.

In an environment like this, an environment of perverse incentives that reward, not the truly serious, but the clever, the quick-witted, the flashy, the skillful self-promoter, and the well-connected, it’s no wonder that the very virtues that good intellectual work, and perhaps especially good philosophical work, requires—patience, intellectual honesty, realism, courage, humility, independent judgment, etc.—are rapidly eroding.

Nor is it any wonder that, in response to all these perverse incentives, over the years, philosophy has become more and more out of touch with its own history, more and more hyper-specialized, more and more fragmented into cliques, niches, cartels, and fiefdoms, and more and more dominated by intellectual fads and fashions: “feminist” this, that and the other, “formal” everything, the enduring Kripke-cult, the recurrent outbreaks of galloping Gettieritis, the vagueness boom, the virtue epistemology bandwagon, the social epistemology blob, etc., etc. And—not surprisingly, given that the neo-analytic paradigm, though institutionally still well-established, seems pretty close to intellectual exhaustion—another notable recent trend has been a craze for “naturalizing” one area of philosophy after another, for “experimental philosophy,” “neurophilosophy,” evolutionary everything, and so on and on.

But isn’t there also, as our editor claims, a notable renaissance of religiously-oriented philosophy? I would have thought that, if there were, I would have noticed; but I’ve seen no sign of any such trend. That’s why, in response to his invitation—explaining that, if there is indeed such a religious revival going on, I’d somehow missed it—I asked what he had in mind; and wasn’t entirely surprised when he acknowledged that such evidence as he had was, as he said, “anecdotal”—more precisely, it was hearsay. So all I can say is that, from where I sit, it looks as if, outside the religious universities. the prevailing culture in the academy (as in the country more generally) is actually increasingly secular.

But isn’t recent work aimed at reconciling Dewey’s A Common Faith with the rest of his oeuvre, as our editor says, “telling”? I can only say that, by my lights, thoughtful scholarship of this kind would be a step forward, not something to be feared. Well, what about those humungous grants doled out by the Templeton Foundation—don’t they exert a significant influence? I have no evidence of this, either. It’s not just that, to judge by my (admittedly limited) experience, a good deal of Templeton’s money seems to be frittered away on conferences and lecture series perhaps best described as “much ado about not very much”; it’s also that Templeton’s religious agenda is hardly a secret—we’re all aware of it, and surely, if we have a lick of sense, discount for it.

But even if I’m wrong, and Templeton’s influence in our field really is significant, it could only be because philosophy professors have been foolish enough to buy into the idea that what we need to do good work is buckets of money for a research team, assistants, equipment, travel to conferences, and the like. Nonsense! How likely is it that a philosopher will make real headway on some significant problem because Templeton gives him millions of dollars to do so? Significantly less likely, I’d say, than if he didn’t have to waste his time meeting with his “research group” and managing a bunch of assistants and a monstrous budget; i.e., pretty darn unlikely. To be sure, landing a whopping grant will likely make you a big man on campus; and, skillfully deployed, all that money may even make you a “name” in our profession. But we all know, if we’re honest with ourselves, that the way to get good philosophical work done is not to give plausible people huge grants, but to allow serious people the freedom to follow ideas where they lead—freedom from pressure to rush the work, exaggerate their results, or reach conclusions deemed politically acceptable, freedom from anxiety that failure to conform to intellectual fashion or to defer to this or that Big Noise may make it difficult to publish in the “prestigious” journals and, more generally, freedom from demands to go along to get along.

By now, probably, some readers are rolling their eyes impatiently. Even if you’re not convinced that a growing religious influence is as important an element in the decline of our discipline as our editor supposes, they will ask, surely you agree that it’s desirable that philosophy be conducted on the basis of strict, scientific naturalism? Sorry, no: here too I have real reservations.

For one thing, by now “naturalism” (like “realism,” “relativism,” “pragmatism,” “feminism,” etc.) is so over-used and so abused that it’s more confusing than helpful. It refers indiscriminately to a whole unruly family of ideas—a family with more than the usual complement of eccentric aunts, alcoholic uncles, bratty children, testosterone-crazed adolescent tearaways, and demented great-grandpas still fighting the battles of their long-ago glory days. For another, and most to the present purpose, an ugly specter haunts the naturalist family mansion: the specter of scientism, i.e., of inappropriate, uncritical deference to the sciences.

In some senses of the word, my philosophy is certainly naturalistic. It doesn’t rely on supernatural assumptions, nor does it reach supernatural conclusions; and I haven’t the slightest inclination to appeal to awe, or transcendence. Moreover, I think philosophy is about the world, not just about our concepts or our language; so my approach is, as I said in Defending Science, “worldly”: it relies on experience as well as reasoning, and is entirely open to calling on the work of the sciences where it’s relevant. In short, it represents a modest form both of naturalism-as-opposed-to-supernaturalism and of naturalism-as-opposed-to-apriorism. But, as the word “modest” signals, I have no sympathy with scientism: in particular, I don’t believe either that we can simply hand philosophical questions over to the sciences to resolve, or that only questions resoluble by the sciences are legitimate. And this leaves me swimming against the rising tide of scientistic philosophical naturalisms.

Thirty years or so ago, in the wake of Quine’s profoundly ambiguous “Epistemology Naturalized,” Alvin Goldman was promising that cognitive science would tell us whether the structure of epistemic justification is foundationalist or coherentist, and Stephen Stich and the Churchlands were announcing that science—cognitive science in Stich’s case, neuroscience in the Churchlands’—had shown the old folk psychological ontology of beliefs and desires to be as mythical as phlogiston, so that epistemology is a pseudo-discipline, a “subject” with no subject-matter. At the time, such ideas seemed like bizarre aberrations; by now, they are so commonplace we scarcely notice how wild they are.

Quine had equivocated, using “science” sometimes to refer to our presumed empirical knowledge generally, and sometimes to refer to the sciences specifically; now, it seems, a false equation of “empirical knowledge” with “scientific knowledge” is ubiquitous. Self-styled “experimental” and “empirical” philosophers pursue Goldman’s old fantasy of squeezing substantive philosophical results out of psychological experiments and surveys; proponents of “metaphysics naturalized”—apparently forgetting questions of history, law, etc., not to mention such questions as what building the physics department is in or what they had for breakfast yesterday—confidently assure us that “with respect to anything that is putatively a matter of fact about the world, scientific institutional processes are absolutely and exclusively authoritative.”

But what about the brand of naturalism most immediately relevant here, naturalism-as-opposed-to-supernaturalism? Whether construed as a metaphysical thesis to the effect that there are no supernatural entities, phenomena, etc., or as a methodological principle to the effect that we should avoid positing such things, this is entirely negative, ruling out certain kinds of approach and certain kinds of theory but silent on where we should go from there. Or so it seems to me. But our editor is by no means alone in supposing that, if we reject supernaturalism, we must conclude that there is nothing but “matter and energy and their interactions,” and that this means that philosophy must look to the sciences for answers. Even if we can articulate an interpretation in which this “nothing-but” thesis is true, the conclusion that the sciences can resolve philosophical questions doesn’t follow. Indeed, reasoning as if it did follow exactly parallels the reasoning of religious people who, asking rhetorically, “can science explain everything?” take for granted that, if the answer is “no,” then religion must fill the gaps; and it is no less faulty.

So, just as naturalism-as-opposed-to-apriorism succumbs to scientism when it falsely assumes that whatever isn’t a priori must be science, naturalism-as opposed-to-supernaturalism succumbs to scientism when it falsely assumes that whatever isn’t religion must be science. Granted, theological “explanations” don’t really explain anything; but it doesn’t follow, and it isn’t true, that science can explain everything. The achievements of the sciences certainly deserve our respect and admiration. But, like all human enterprises, science is fallible and incomplete, and there are limits to the scope of even the most advanced and sophisticated future science imaginable.

Evolutionary psychology, for example, might tell us a good deal about the origin of the moral sentiments or the survival value of altruism; but it couldn’t tell us whether or, if so, why these sentiments, or this disposition to help others, could constitute the basis of ethics. Cognitive science might tell us a good deal about people’s tendency to notice and remember positive evidence and to overlook or forget the negative; but it couldn’t tell us what makes evidence positive or negative, or what makes it stronger, what weaker. Neuroscience might tell us a good deal about what goes on in the brain when someone forms a new belief or gives up an old one; but it couldn’t tell us what believing something involves, or what makes a belief the belief that 7 + 5=12 rather than the belief that Shakespeare’s plays were really written by Francis Bacon, or what evidence warrants a change of belief. More generally, none of the sciences could tell us whether, and if so, why, science has a legitimate claim to give us knowledge of the world, or how the world must be, and how we must be, if science is to be even possible.

And the rising tide of scientistic philosophy not only threatens to leave the very science to which it appeals adrift with no rational anchoring; it also spells shipwreck for philosophy itself. We don’t need to imagine the disaster; we can watch it unfold before our eyes in Alex Rosenberg’s The Atheist’s View of Reality. His title, with its presumptuous suggestion that he speaks for all of us, should already raise a red flag. His next move—adopting “scientism” for the view that all atheists share—makes matters worse. For one thing, it’s downright perverse: “scientism” has long been a pejorative term; and anyway, we already have a perfectly good word for the view that all atheists share: “atheism.” For another, this perverse verbal maneuver glosses over the fact that by no means all atheists are motivated by scientific considerations. And from then on things get, as children say, “worser and worser.” Endlessly repeating his mantra, “physics fixes all the facts,” Rosenberg gleefully announces that this means there is no meaning, no values—moral, social, political or, apparently, epistemological—and, in effect, no mind: “the brain does everything without thinking about anything at all.”

“Well, yes,” you may say, “this is, admittedly, dreadful stuff; but it’s not at all the kind of thing we reasonable humanists are proposing.” I’m glad to hear it; but you’re making my point for me. To my mind—yes, Professor Rosenberg, I do have one!—answering questions like “What’s distinctive about human mindedness?” “What’s the relation between natural and social reality?” “How does philosophy differ from the sciences?” “What has philosophy to learn from the sciences, and they from it?” etc., requires serious philosophical work.

[S]erious philosophical work, like any serious intellectual work, means making a genuine effort to discover the truth of some question, whatever that truth may be. If, rather than make this effort, we rely on slogans—whether on religious slogans like “Restore Awe and Transcendence,” or on anti-religious slogans like “Save Scientific Naturalism”—we will fall into what Peirce called sham reasoning: “it is no longer the reasoning that determines what the conclusion shall be, but the conclusion that determines what the reasoning shall be.” The inevitable result, he warned in 1896, will be “a rapid deterioration of intellectual vigor”; which, he regretfully continued, “is just what is taking place before our eyes.” Sadly, it still is.