Welcome to a few items today with the main newsletter coming tomorrow (in the absence of global nuclear armageddon)

A word I made up

📘 Agonocracy (noun)

/ˈæɡəˌnɒkrəsi/

From Greek agōn (ἀγών), meaning “contest” or “struggle,” especially in a public or performative setting, and -cracy from kratos (κράτος), meaning “power” or “rule.”

Agonocracy: literally, rule by contest.

Government by factions whose views are pre-determined by political advantage, culture war, and party discipline. Politicians, talking heads, and their supporting players in consulting or the bureaucracy are strategic performers seeking outcomes — manipulative effectiveness, not deliberative authority.

As the system totalises, sincere engagement increasingly becomes a category error — mistaking appearances for underlying realities.

🗣️ More simply:

Agonocracy:

• where decisions are upstream of debate;

• debate is legitimating theatre; and

• participating sincerely is how you get played.

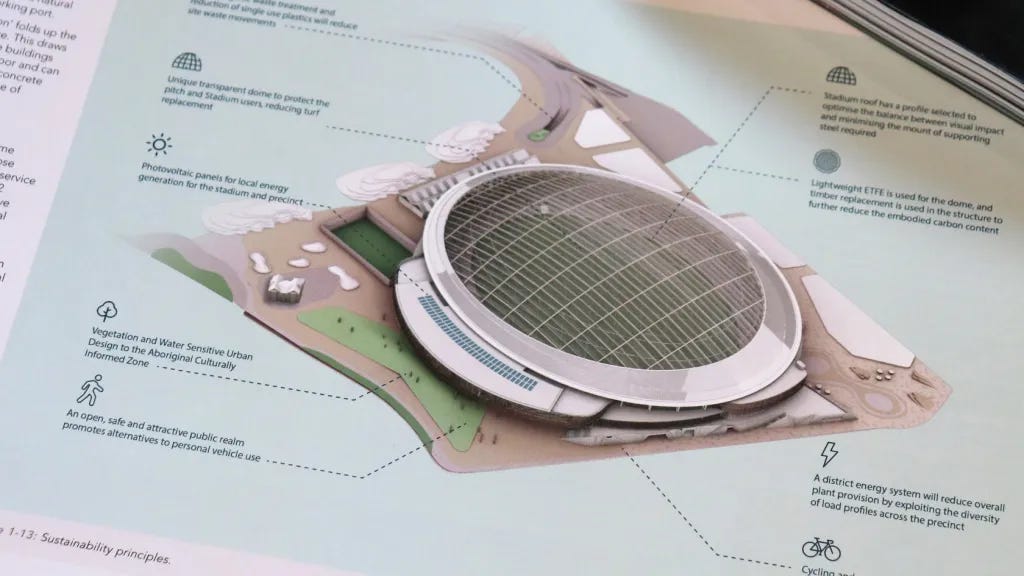

Bernard Keane on me on KPMG on Hobart stadium

Economist Nicholas Gruen has rubbished the work of big four auditor KPMG for the Tasmanian government on the controversial proposal to build a new stadium in Hobart.

Big four audit firm KPMG tried to dictate how a government body should assess the case for a new stadium in Hobart, omitted obvious inclusions that would have undermined the case for the stadium, and made some bizarre assumptions, independent economist Nicholas Gruen has revealed in evidence to the Tasmanian Parliament.

Earlier this year, in the wash-up from the Tasmanian election and after a demand by Jacqui Lambie Network MPs, Gruen was commissioned by the minority Tasmanian government to prepare an independent report on the building of a new stadium in Hobart. His report found that the cost of the stadium had been significantly understated by the government.

Giving evidence to Tasmania’ Parliamentary Accounts Committee, Gruen took aim at the work of KPMG, which was commissioned by the government body building the stadium, the Macquarie Point Development Corporation, to provide economic analysis for the project.

Gruen identified a number of howlers in KPMG’s work, as well as the fact that it refused to comply with a request from the Tasmanian Planning Commission (TPC) to provide an alternative public project scenario to enable an understanding of the opportunity cost of the project.

The TPC’s guidelines are explicit that “the economic impact report should also consider the opportunity cost of domestic investment — for example, a ‘counter-factual’ estimate of the impact of an alternative investment of equivalent public funds.” Gruen’s own report provided a counter-factual case of an educational facility.

But KPMG point-blank refused to comply, and criticised the commission for its “false premise that the opportunity cost of the stadium is an alternative investment that the government may choose to do.” It’s a bizarre argument: trying to determine whether a major project involving both public land and extensive government spending should proceed must surely involve some consideration of what alternative uses such assets could be put to.

As Gruen put it to state MPs “it takes some nerve to argue that your requirement is based on a ‘false premise’. It is, rather, based on the textbook application of the most fundamental concept in economics — that of opportunity cost.”

Infrastructure Australia’s Guide To Economic Appraisal also states that “the capital costs should include the opportunity cost of the land used, even where this is currently owned by government”. But KPMG did not include the opportunity cost of the land on which the stadium will be built in its costings for the project, thus understating the costs by over $150 million.

KPMG’s work contains other serious problems. Gruen estimates that overall “there are an additional $322 million of costs on top of the cost estimate presented in the Project of State Significance project, bringing total capital costs to $1,096 million compared with the claimed $775 million.”

And KPMG wildly overstates how many interstate visitors would attend matches — thereby inflating the benefits from interstate tourism. KPMG based its figures on how many interstate visitors attended AFL matches in Launceston. Problem is, those matches featured two interstate teams, whereas the new stadium would host matches involving the local Tasmanian team and one interstate team. Then KPMG inflated that number based on the assumption that matches in the new stadium would attract bigger crowds than in Launceston.

Nor does KPMG anywhere respond to Gruen’s earlier report. In fact, in its late January addendum for the corporation, KPMG rather ostentatiously pretends that Gruen’s report, which raised a large number of concerns about KPMG’s assumptions, simply doesn’t exist. It suggests KPMG lacked the wherewithal to mount any sort of intellectual defence of its overly generous assumptions — and conjures memories of its outrageous and deeply conflicted role in the TAHE scandal in NSW.

Gruen told Crikey it’s symptomatic of a broader problem in public policy. “There is no-one in the system whose job it is to get to the truth. Rather we have a ‘for’ and ‘against’ position and they fight it out in front of an audience of partisans. As this system reaches its end point it’s no-one’s job to seek or speak the truth. Ultimately the Westminster system has been slowly drowned by the party system and media imperatives.

“The only way to rescue democratic accountability from this unaccountability machine is a crossbench with the balance of power — the thing that empowered me to seek and speak the truth about the stadium.”

Me with Leon Gettler on Trump’s tariffs and trust in the US

Or here if you want to listen on your podcaster.

Great minds think alike

What do these inventions all have in common?

The telephone

Calculus

The theory of evolution

The light bulb

The airplane

The radio

Penicillin

Decimal Logarithms

Yes, you’re right. All these incredible inventions were independently discovered/invented by more than one person at roughly the same time. (Except penicillin - please pay attention.) Well … in addition to my coming up with the idea of a standing body of citizens chosen by lottery to pressure politicians to serve the citizenry so too did Philosophy Bear. As he put it introducing the idea.

This could be the most important piece I’ve ever done. I certainly hope it is, because if it happens, and if it works, politics will change, and I’m not the only one sick of the status quo.

In other news, at least on this post, Bear put his picture at the bottom of his post. I would never do that.

In any event, over to Bear.

The essential ideas herein were independently developed by me and Nicholas Gruen, who have since had some conversations on the subject. I mention him to give him full credit, but no blame should be assigned to him for any error or foolishness in the specifics of what I outline. If you dislike something I say, do not assume he endorses it. In particular, the name I assign— Government Watch— is just what I call it

An apology for a necessary evil

In the following piece, I will sound like a salesman. I hate that, but some things are so important they've got to be sold. I have such a proposal.

I write about a lot of proposals here, but this one is almost unique in how little money and power it would take. It would cost a few tens of millions to run for several years. I believe— and I don't say this lightly — that it could be the most effective available way to spend money. There's a small (<1%) but real chance it could be as consequential as, for example, the storming of the Bastille...

The general idea of sortition

Electoral democracy has all sorts of problems, but having everyone discuss and debate every political issue isn't feasible and would waste oceans of precious human life (time). Sortition tries to get the best elements of both. Sortition means selecting officials or representatives by chance— a random sample of the population they are to represent.

The best argument for sortition is a five-minute conversation with the average politician.

It's not that politicians are bad necessarily (but a lot are) it's more that they're so incredibly differen— so abstracted from the lives of ordinary people.

They're different for many reasons. They're different in virtue of the strange qualities they were born with, different in virtue of the strange deeds they had to do to get their positions, and different in virtue of the strange company they now keep...

The paradox of Democracy: Anyone representative of the people's values would likely have a great deal of trouble winning an election to represent the people.

Whether or not sortition would work to run a country is an open question, but it does function well enough as a source of reasoned commentary and criticism. There have been various experiments with sortition— mostly creating bodies to advise the government, often on a specific topic. These experiments are generally thought to have been enormously successful. Perhaps surprisingly, people do not dig in but are able to come to a wide-ranging consensus— typically humane, rational, and comprehensive. Most participants learn a great deal. Many leave lifelong advocates of sortition. Few have negative experiences.

Our specific proposal

Our idea is a twist on sortition. Generally speaking, sortition bodies are convened for a fixed period to deal with a specific issue and are often attached to the government—whether as an official organ or an experiment. Our aim is to create:

A permanent body chosen by sortition from the general population, tasked with commenting on political events, decisions, and public matters as it sees fit, wholly independent of government and administered by an NGO.

We haven't settled on a name yet, so for the moment I'll use my old name for it: Government Watch...

We think Government Watch will work because it meets real and felt needs. People are aware that they are being manipulated with complexity, sensationalism and outright dishonesty. Issues are often difficult, and even when they're not, bad actors have an interest in making them feel difficult. The public has a sense— often accurate— that many of the people who know more about political questions than they do have very alien values and goals. I'm not talking about some hypothetical rube here, I'm talking of myself as much as anyone. I know I feel this way about a ton of issues (e.g. industrial policy, energy grid security). We all want to know what we'd think if we had time to dig into the issues and talk about them.

In the ideal case, Government Watch would become a lighthouse for everyone who isn't involved in politics, and who wants to know what they and their peers might think if they had the time to learn about and discuss the issues in great depth...

Analogies

Is sortition just issue polling? No, because:

It gives participants a chance to think, learn, and talk before voting.

Issue polling presents us with fixed options and aggregates us into numbers, rather than allowing us to phrase our own response— it thus ignores the real complexity of opinion. The rich terrain of thought is reduced to a 1D elevation graph.

A statement written by a group to represent their feelings can have far more nuance, persuasiveness, and pathos than a polling result...

Risk management

Like other mini-publics, the Government Watch would have to have access to expert testimony as desired to work. It would need, as far as possible, the capacity to select its own sources of testimony. I see the expert testimony process— the selection and approach to the experts— as a key point that needs to be gotten just right, or else real and apprehended biases will result.

The primary risk to the effectiveness of our proposed NGO is the development of a perception that the body is not truly neutral— that either the selection of participants or the facilitation of the process is unfair. Absolute precision, both fairness and the appearance of fairness would be required, since players of all sorts would be seeking to delegitimate every decision they disagreed with...

Trying to change the world is a dice roll, always. Fortunately, Government Watch can succeed at lesser and greater levels. The moonshot— what I and Gruen hope for and genuinely believe is a real possibility— is the situation described above where the body we create is constantly in the news giving the public information about what they would likely come to believe if they had the opportunity to deliberate. But lesser, and still significant triumphs are possible...

Cost and mechanics

Back-of-the-coaster calculations suggest it could be run at 12 million dollars a year, covering:

A stipend for 120 participants equal to forty hours at the median hourly wage per week.

A small publicity, facilitative, and administrative team

Venue hire

Remarkably cheap. In terms of the facilitators, I would suggest targeting for recruitment multiple people who have run and/or helped facilitate citizens' assemblies previously.

Naturally, a body like I've described is going to vary a bit based on the luck of which 120 people happen to be sitting on it, and thus opinions on close questions might be unstable. My proposal for dealing with this— implement a supermajority requirement for passing motions. Two-thirds (80 out of 120) seems like a natural bar— and will serve to give the decisions stability...

The full article is here:

Heaviosity half-hour

Franz Kafka’s advice on a laughing fit at the office - lean in!

Apologies for the long paragraph. Blame Kafka. I’m just a faithful scribe here.

From his letter to Felice, January 8 to 9, 1912.

I can also laugh, Felice, have no doubt about this; I am even known as a great laugher, although in this respect I used to be far crazier than I am now. It even happened to me once, at a solemn meeting with our president—it was two years ago, but the story will outlive me at the office—that I started to laugh, and how! It would be too involved to describe to you this man's importance; but believe me, it is very great: an ordinary employee thinks of this man as not on this earth, but in the clouds. And as we usually have little opportunity of talking to the Emperor, contact with this man is for the average clerk—a situation common of course to all large organizations—tantamount to meeting the Emperor. Needless to say, like anyone exposed to clear and general scrutiny whose position does not quite correspond to his achievements, this man invites ridicule; but to allow oneself to be carried away by laughter at something so commonplace and, what's more, in the presence of the great man himself, one must be out of one's mind. At that time we, two colleagues and I, had just been promoted, and in our formal black suits had to express our thanks to the president—here I must not forget to add that for a special reason I owed the president special gratitude. The most dignified of us (I was the youngest) made the speech of thanks—short, sensible, dashing, in accordance with his character. The president listened in his usual posture adopted for solemn occasions, somewhat reminiscent of our Emperor when giving audience—which, if one happens to be in a certain mood, is a terribly funny pose. Legs lightly crossed, left hand clenched and resting on the very corner of the table, head lowered so that the long white beard curves on his chest, and, on top of all this, his not excessively large but nevertheless protruding stomach gently swaying. I must have been in a very uncontrolled mood at the time, for I knew this posture well enough, and it was quite unreasonable for me to be attacked by fits of the giggles (albeit with interruptions), which so far however could easily be taken as due to a tickle in the throat, especially as the president did not look up. My colleague's clear voice, eyes fixed straight ahead—he was no doubt aware of my condition, without being affected by it—still kept me in check. But at the end of my colleague's speech the president raised his head, and then for a moment I was seized with terror, without laughter, for now he could see my expression and easily ascertain that the sound unfortunately escaping from my mouth was definitely not a cough. But when he began his speech, again the usual one, all too familiar, in the imperial mold, delivered with great conviction, a totally meaningless and unnecessary speech; and when my colleague with sidelong glances tried to warn me (I was doing everything in my power to control myself), and in so doing reminded me vividly of the joys of my earlier laughter, I could no longer restrain myself and all hope that I should ever be able to do so vanished. At first I laughed only at the president's occasional delicate little jokes; but while it is a rule only to contort one's features respectfully at these little jokes, I was already laughing out loud; observing my colleagues' alarm at being infected by it, I felt more sorry for them than for myself, but I couldn't help it; I didn't even try to avert or cover my face, but in my helplessness continued to stare straight at the president, incapable of turning my head, probably on the instinctive assumption that everything could only get worse rather than better, and that therefore it would be best to avoid any change. And now that I was in full spate, I was of course laughing not only at the current jokes, but at those of the past and the future and the whole lot together, and by then no one knew what I was really laughing about. A general embarrassment set in; only the president remained relatively unconcerned, as behooves a great man accustomed to the ways of the world and to whom the possibility of irreverence toward his person would not even occur. Had we been able to slip out at this moment (the president had evidently shortened his speech a little), everything might still have gone fairly well; no doubt my behavior would have remained discourteous, but this discourtesy would not have been mentioned, and the whole affair, as sometimes happens with apparently impossible situations, might have been dealt with by a conspiracy of silence between the four of us. But unfortunately my colleague, the one hitherto unmentioned (a man close to 40, a heavy beer drinker with a round, childish, but bearded face), started to make a totally unexpected little speech. At that moment this struck me as quite incomprehensible; my laughter had made him lose his composure, he had stood there with cheeks blown out with suppressed laughter—and now he embarked on a serious speech. Actually this was quite consistent with his character. Empty-headed and impetuous, he is capable of defending generally accepted statements, passionately and at length, and the boredom of this kind of speech, without the absurd but engaging passion, would be intolerable. Now, the president in all innocence had said something to which this colleague of mine took exception. In addition, influenced by my continuous laughter, he may have forgotten where he was; in short, he assumed the moment had come to air his particular views and to convince the president (a man utterly indifferent to other people's opinions). So now, as he started to hold forth, brandishing his arms, about something absurdly childish (even in general, but here in particular), it was too much for me: the world, the semblance of the world which hitherto I had seen before me, dissolved completely, and I burst into loud and uninhibited laughter of such heartiness as perhaps only schoolchildren at their desks are capable of. A silence fell, and now at last my laughter and I were the acknowledged center of attention. While I laughed my knees of course shook with fear, and my colleagues on their part could join in to their hearts' content, but they could never match the full horror of my long-rehearsed and practiced laughter, and thus they remained comparatively unnoticed. Beating my breast with my right hand, partly in awareness of my sin (remembering the Day of Atonement), and partly to drive out all the suppressed laughter, I produced innumerable excuses for my behavior, all of which might have been very convincing had not the renewed outbursts of laughter rendered them completely unintelligible. By now of course even the president was disconcerted; and in a manner typical only of people born with an instinct for smoothing things out, he found some phrase that offered some reasonable explanation for my howls—I think an allusion to a joke he had made a long time before. He then hastily dismissed us. Undefeated, roaring with laughter yet desperately unhappy, I was the first to stagger out of the hall. By writing a letter to the president immediately afterwards and through the good offices of one of the president's sons whom I know well, and thanks also to the passage of time, the whole thing calmed down considerably. Needless to say, I did not achieve complete absolution, nor shall I ever achieve it. But this matters little; I may have behaved in this fashion at the time simply in order to prove to you later that I am capable of laughter.