Western civilisation

A good idea: Still is, always was

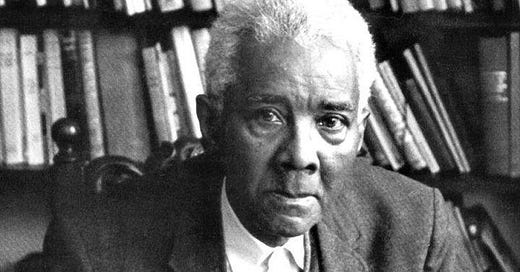

When asked what he thought of Western civilisation, Ghandi famously said he thought it would be a good idea. It’s great line. And he was making a devastatingly good point. But there you go. I love Western Civilisation. And of course as Ghandi reminds us, it’s done a whole lot of horrible things. Which brings me to an excellent column on the remarkable CLR James.

“I denounce European colonialism”, wrote CLR James in 1980, “but I respect the learning and profound discoveries of Western civilisation.” … Cyril Lionel Roberts James, described by V.S Naipaul as “the master of all topics”, was one of the great (yet grossly underrated) intellectuals of the 20th century. He was one of the few Leftist intellectuals – as Christopher Hitchens once said about George Orwell – who was simultaneously on the right side of the three major questions of the 20th century: Fascism, Stalinism and Imperialism. But today his praise for ‘Western culture’ would probably be dismissed as a slightly embarrassing residue of a barely concealed ‘Eurocentrism”’ …

James’s admiration for Western culture and the Western canon is something many black radicals, who otherwise admire James for his opposition to colonialism, struggle to understand about him. … James, though, was, to his core, a radical humanist who believed in the collective power of human beings to transform society and be masters of their own future. He held this fundamental principle throughout his life, above any narrow characteristic such as race, ethnicity, or nationality. While James opposed dogmatic, class-reductionist forms of Marxism that didn’t take into account the importance of racist oppression, or were indifferent to the specific struggles of black people for their freedom, he had no time whatsoever for half-baked romantic notions of ‘negritude’, or essentialist black nationalism.

James was strongly anti-imperialist, yet he wasn’t anti-Western (a distinction that often gets lost these days), and was one of the few radical Leftists who talked of Western civilisation unironically, without “scare quotes”. James himself, in a 1969 essay called Discovering Literature in Trinidad, was explicit about the influence of ‘Western civilisation’ on his outlook:

“I didn’t learn literature from the mango tree, or bathing on the shore and getting the sun of colonial countries; I set out to master the literature, philosophy and ideas of Western civilisation. That is where I have come from and I would not pretend to be anything else.”

He was, as Farrukh Dhondy observed in his biography, “the only intellectual of the black diaspora to unequivocally espouse and embrace the intellectual, artistic and socio-political culture of Europe”. For James, the emancipation of the black mind would come from embracing the works of “dead white men” such as Socrates, Sophocles, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Thackeray and Dickens, as much as the works of W.E.B. Du Bois, Aime Cesairé, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison.

He believed the European canon provided black people with a means of empowering themselves both culturally and intellectually, to broaden their imagination, to liberate them from the tyranny of geography and race, and help them transcend their particularity and enter into a universal conversation across colour lines, based on a shared humanity. …

This legacy is important for us today, because James understood that the Enlightenment, though conceived and initiated (for historical reasons, not genetic ones) mainly by privileged white European men, is the common property of all of humanity.

Indeed, it was the struggle of those who were initially excluded, like black people, against a background of colonial domination and racial subordination that brought the seemingly abstract Enlightenment ideals of liberty and equality closer to concrete reality; the Haitian revolution, which he documented so majestically in The Black Jacobins, is an embodiment of this struggle. What the French started in 1789, the Haitians completed in 1804. For James, then, the Enlightenment, and the struggle to complete it, was and still is a global, and hence a universal, project.

The antisemitism breaking out in Melbourne’s suburbs

A very upsetting podcast, which the ABC, in its very considerable wisdom, doesn’t make easily available as a podcast. Click on the image and listen.

Why I don't support the CEO Sleepout

Anne-Marie Elias wants a little more actual contact with the folks and the problem.

The missing piece for me is that the CEO's do not spend their night talking to the homeless but to each other. … Don't get me started on last year's stunt of using Virtual Reality to show CEOs what life is like on the streets (you can see my views here).

A well-known homelessness sector advocate told me they tried to attend the CEO Sleepout with homeless people but were turned away by Vinnies staff. And I get it - you don't want to upset the "orderlyness" of the event or the participants having to talk to someone who may have a number of problems going on, but seriously WHY NOT?

This is why I despair at the CEO sleep out - I know in my heart if the CEOs spent a day in the shoes of those who are homeless - they will see something far more important than hustling to be sponsored for a PR exercise, but rather they may actually choose to be a bigger part of the solution - like offer their time to truly understand the problem and help with meaningful solutions like jobs, housing, education, literacy, financial inclusion and more. …

The ACTU has been leading this discourse for some time under the leadership of Sally McManus which is largely ignored by the very corporates the CEO Sleepout attracts.

You see in December 2013 because of the passing of a beautiful young boy - Jordan Filoia - a group of us volunteered at Rev Bill Crews' Exodus Foundation restaurant in Ashfield - we did this for three years and in that time noticed the increasing number of working families and people, the retired teachers or factory workers who can no longer make ends meet on their stagnated wages or their meagre pension. …

Last year Vibewire ran a #hack4homelessness (see the final report here ) and the thought that we would do that event without homeless people at the front and centre never crossed our mind. In fact we had two homeless people who stayed with us the whole weekend and ended up on the judging panel. Another two homeless people were unidentified - you wouldn't be able to pick them even if you tried - they chose to be anonymous and that was respected by the organisers and the participants. One homeless worker was so sure they knew they could pick who they were - they didn't! These people work day jobs, they wear suits and look just like you and me - the difference is they don't have a home, or even a room, they couch surf, sleep on trains and sometimes in their car.

How are YOU #BattlingTheBullshitBorg

This is what Karl did

Therapeutic placebos

In 2019 I wrote this after listening to a fascinating guest on the placebo effect on the inimitable Russ Roberts’ podcast Econtalk:

As medicine was made more scientific, the placebo effect was discovered, and then marginalised. Yet it was of unarguable therapeutic power. Of course it’s entirely appropriate that, if one is looking for drug therapies, one wants to find drugs that, other things being equal, do better than sugar pills.

But in the process, the trail goes cold on keeping the placebo effect in the frame, not only for what it might help us understand, but, more remarkably, even for its therapeutic potential. There’s been vanishingly little investigation of the joint effect of the drug and the placebo acting together. And it turns out that, investigating the placebo effect more broadly, it seems likely that it has something to do with empathic bonds — between some source of authority like the doctor and the patient. Or perhaps from anyone.

It’s a deep subject. Anyway, as luck would have it, I got to invest in a start-up that was using the placebo effect to good therapeutic effect. It was also started by someone who I thought displayed a high degree of terrificness. Here’s a story from MIT on what she and her other founder have produced.

I hate needles. I am a grown woman who owns a Buzzy, a vibrating, bee-shaped device you press against your arm to confuse your nerves and thus reduce pain during blood draws. …

That’s why I was so excited to read about Smileyscope, a VR device for kids that recently received FDA clearance. It helps lessen the pain of a blood draw or IV insertion by sending the user on an underwater adventure that begins with a welcome from an animated character called Poggles the Penguin. …

But how Smileyscope works is not entirely clear. It’s more complex than just distraction. Back in the 1960s, Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall posited that pain signals travel through a series of “gates” in the spinal cord that allow some to reach the brain and keep others out. …

Not all stimuli are equally effective. “[In] traditional virtual reality you put on the headset and you go somewhere like a beach,” Leong says. But that kind of immersive experience has nothing to do with what’s happening in the real world. Smileyscope aims to reframe the stimuli in a positive light. Mood and anxiety can also affect how we process pain. Poggles the Penguin takes kids on a thorough walk-through of a procedure before it begins, which might reduce anxiety. And experiencing an underwater adventure with “surprise visitors” is undoubtedly more of a mood-booster than staring at clinic walls, waiting for a needle prick.

“There are a lot of ways to distract people,” says Beth Darnall, a psychologist and director of the Stanford Pain Relief Innovations Lab. But the way Smileyscope goes about it, she says, is “really powerful.”

Researchers have been working on similar technologies for years. Hunter Hoffman and David Patterson at the University of Washington developed a VR game called SnowWorld over two decades ago to help people with severe burns tolerate wound dressing changes and other painful procedures. “We created a world that was the antithesis of fire,” Hoffman told NPR in 2012, “a cool place, snowmen, pleasant images, just about everything to keep them from thinking about fire.” Other groups are exploring VR for postoperative pain, childbirth, pain associated with dental procedures, and more.

Companies are also working on virtual reality devices that will address a much tougher problem: chronic pain. …

Gadgets

Speaking of investments I’ve made, this comes from a list of gadgets of the year. Some are cool and many are silly. But this one jumped out because I once invested in a Y-Combinator graduate start-up established by a person with a quite substantial hearing deficit and he was doing something whose time had obviously come; creating a hearing aid to be controlled from an app on your smart-phone with a target price of US$100 rather than the price you get from ‘audiologists’ which is $2-12,000, a good chunk of which goes to audiologists for posing as hearing aid specialists when they’re really hearing aid salespeople. The audiologist scam should have been busted up years ago and replaced with something more efficient and effective, but has not been. In any event, they don’t call it hardware for nothing. Hardware is hard. Much harder than software. The start-up I invested in went broke. But now someone’s done it — or says they have.

Oh, and imagine if economics really was about maximising utility or wellbeing. Why what with hearing improving most people’s lives, economists would be shouting the importance of these guys from the rooftops. Every year, Treasurers might issue a Budget Paper on gains in consumer surplus from product innovation with a particular focus on how technology can improve people’s lives, particularly the disabled.

Lovely

Sora: big news for YouTubers

AI jumped the barrier to motion today, though its ability to produce deep fakes means it’s still in testing and is not generally available. It’s stunning and I wish I could use it!

Some anti-anti-capitalism

Jeremiah is not too keen on Jeremiads against capitalism. The author is cofounder of the left-of-centre Center for New Liberalism.

Complaints about The Man were a common theme in film and television through the 70s, 80s, and 90s. As with so many parts of pop culture, the phrase had roots in black film and television before migrating to the mainstream. What used to be a mainstay of blaxploitation1 films was now being parroted by white teenage stoners. Anybody who grew up in the 90s can perfectly recollect “It’s just like, Society, mannnnn. It’s like, The Man, screwing us over” as spoken by an angsty teen. …

Ugh, Capitalism and all its variations are a reliable way to give any statement that oomph, that hit of seriousness. It can signal that you’re one of the Good Guys, one of the people who gets it. Patricia Lockwood’s excellent book No One is Talking About This is one of the finest examples of internet logic I’ve seen:

Capitalism! It was important to hate it, even though it was how you got money. Slowly, slowly, she found herself moving toward a position so philosophical even Jesus couldn’t have held it: that she must hate capitalism while at the same time loving film montages set in department stores.

There are of course a few lonely souls who can actually define capitalism correctly and make coherent arguments about it. Rare as they may be, some people actually are writing detailed critiques of capitalism as an economic system. Good for them, even if I think they tend to be wrong more often than right. I hope they keep going.

But that’s not the typical way this argument goes. The typical way it goes is basically two words: “Ugh, capitalism”. There’s no escaping this, not until we have another generational shift and complaining about capitalism becomes as culturally passé as complaining about The Man Keeping You Down. It’s likely that as capitalism replaced The Man, some other boogeyman-societal-force will replace capitalism a few decades from now. In the meantime, we should at least notice the pattern.

This would be nice: but I’m not holding my breath

Why does everywhere look the same?

Except old stuff. That’s the question Culture Critic asks, before supplying a blizzard of stuff that doesn’t look the same — because it’s old. This is what Vikings came up with when they started building churches.

Noah Smith: Ukraine, Russia and Poland

Interesting piece from the omni-interested Noah Smith

Americans never asked for a lesson in East European history, but we’re getting one. Tucker Carlson, exiled from Fox News and now broadcasting mainly on

If you’re interested, you can watch the full interview here. Mostly, it’s just Putin talking, and most of what he talks about is the history of East Europe. He’s arguing that Ukraine is rightfully part of Russia, by dint of linguistic and cultural similarity and historical relationships. He only mentions NATO expansion — a favorite hobbyhorse of Ukraine’s detractors in the West — after Tucker prompts him to talk about it, and even then only briefly.

This is a kind of imperialism that people in the U.S. are not used to thinking about. Mostly, when we Americans think of empires, we think of either the British or the Nazis — most of the fictional empires we depict in media, like the one in Star Wars, are just a mashup of those two. We therefore think of imperialists as being motivated primarily either by commercial interests and resource extraction, or by insane ideologies. But we rarely think about ethnic imperialism — an empire trying to gobble up neighboring polities because of linguistic and cultural similarity, so that it can be the ruler of a specific cultural sphere. (In fact, the British conquest of Ireland, the Japanese conquest of Korea and China, and Hitler’s annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia all had major elements of ethnic imperialism, but we tend to forget that aspect.)

Ethnic imperialism is exactly what we’re facing in Russia right now. Putin doesn’t want Ukraine’s wheat farms. Nor is he motivated by some world-conquering ideology. He simply wants Russia to rule over all the places he views as being within its historic and linguistic sphere of influence.

The question is where that sphere stops. Putin assured Carlson that he has no designs on Latvia or Poland. This rather pointedly leaves out Estonia, where 25% of the population are Russian speakers, and which Russia continually bullies despite its NATO membership. But the elephant in the room here is really Poland.

Russia vs. Poland

Poland and Russia have a long history of conflict. In the early 1600s, Poland invaded Russia and occupied Moscow. Half a century later, Russia struck back, invading and occupying part of Poland, even as Sweden crushed the Poles from the west. Russia then defeated the Swedes and fully conquered Poland in the late 1700s, ruling for a little over a century until World War 1 allowed Poland to break free. The USSR tried to reconquer the country after WW1, but was defeated. They then schemed with Nazi Germany to divide up Poland between them. After the Nazis betrayed the Soviets and were defeated, the USSR allowed Poland to keep its official status as an independent country, but in practice it was tightly controlled by Moscow. In the 1980s, Poland asserted its independence again with the Solidarity movement, which hastened the end of Russian control over East Europe as a whole.

It’s clear that this history is very much on Putin’s mind when he thinks about Ukraine. Ukraine’s name comes from a word meaning “borderlands”, and it’s clear that Putin thinks about this “border” as being the one between Russia and Poland:

Originally, the word ‘Ukrainian’ meant that a person was living on the outskirts of the state, near the fringe, or was engaged in border service. It didn’t mean any particular ethnic group.

So, the Poles were trying in every possible way to polonise this part of the Russian lands and actually treated it rather harshly, not to say cruelly. All that led to the fact that this part of the Russian lands began to struggle for their rights…[I]n 1654, even a bit earlier, the people who were in control of [Ukraine] addressed Warsaw…demanding their rights be observed…When Warsaw did not answer them and in fact rejected their demands, they turned to Moscow so that Moscow took them away [from Poland].

Putin is thinking a lot about the 1600s, and the conflict between Russia and Poland that took place in that century. He sees Poland as a natural rival for influence in East Europe, especially over Ukraine. And in a way, he’s right. Linguistically, Ukrainian lies somewhere between Russian and Polish. In fact, at one point some Russian soldiers invading Ukraine claimed to have found a version of the Ukrainian language written in the Latin alphabet. The language they were looking at was Polish.

And it’s no coincidence that Poland has been one of the most steadfast countries supporting Ukraine’s war effort against Russia, contributing a higher percent of its 2022 GDP than any country except Latvia and Estonia, and excoriating Republicans in the U.S. for wanting to abandon Ukraine.

So Putin, like many Russian leaders of the past, sees the limitation of Polish power and influence in East Europe as a priority. Poland is much smaller than Russia — it has only a quarter of Russia’s population — but it’s large enough that keeping it subjugated is a constant headache. Russia’s greatest success in subjugating Poland came when Western powers — the Swedes in the 1650s and the Nazis in the 1930s — helped pincer the country from the other side.

This is probably why Putin, in his interview with Tucker, blamed Poland for provoking the Nazi invasion by refusing to cede territory to Hitler. In Putin’s cosmology, the world is only set aright when Poland acknowledges its status as a secondary, subordinate power.

And this is a clue to why Putin decided to crush Ukraine’s independence sooner rather than later. The last three decades has seen an expansion of Polish power and autonomy unprecedented since the 1600s.

Really enjoyable and interesting interview with Billy Joel

And YouTube being what it is, served up some more. It was great too. If you have the time both are highly recomended.

Peak psycho? we may have some way to go

Unrolling a tweet thread from Lindsay Beyerstein

It's fashionable to say Hofstadter was wrong and the paranoid style has always been central to American politics. But you can't read this and deny that there has been a sea change. Trump is promising to lead the Battle of Armageddon.

When Hofstadter wrote the paranoid style, huge swathes of American public, including much of the GOP was scandalized and shaken when Goldwater said extremism in defense of liberty was no vice.

People incorrectly conflate the paranoid style with conspiracy theories. The paranoid style is often associated with conspiracy theories, but there's more to it than that. It's a behavior pattern marked by overheated suspicion and hostility.

Ronald Reagan often trafficked in conspiracy theories but he did not embody the paranoid style. He claimed Gerald Ford faked his own assassination attempt for sympathy but his political brand was sunny and optimistic.

Abraham Lincoln invoked what was arguably a conspiracy theory in his House Divided speech. And some authors cite it to prove the paranoid style is ubiquitous--but Lincoln's political brand was the opposite of the paranoid style. …

You can point to episodes in American history where the paranoid style crept towards the mainstream, like the McCarthy Era. But the fact remains Joe McCarthy embodied the paranoid style and Harry Truman largely didn't. Though both worried about subversion.

McCarthy died in disgrace after he went after the US military. Right wing propagandists from William F. Buckley to Anne Coulter tried to rehabilitate his image and it never worked because the American public didn't like that sort of thing.

But now you've got Trump, the protege of Roy Cohn, who was the protegé of Joe McCarthy himself, … swearing to use the Department of Justice to investigate "every Marxist prosecutor" and assailing General Milley as some kind of radical leftist and on and on and on. And it barely even makes the news.

#HitlerBingo

We’re all fascinated with how things could have gone quite so bad as they did in the 1930s and 40s. In fact one family member has been unkind enough to christen my own frequenet references to the guy at the centre of it all “Hitler Bingo”. If the cap fits wear it. If you’ve ever played #HitlerBingo you’ll be pretty amazed by this story of confusion and loss. You can read the story here if you don’t mind spoilers.

Recommended.

Interesting discussion about AI

It’s over six months old, but I still found this discussion of some major things going on in AI pretty interesting, particularly the prospect that AI might not be dominated by the current AI overlords Microsoft and Google thanks to ‘quantisation’ (the sliming down of LLMs to be nearly as good on low powered kit) and open sourcing.

Israel

Interesting piece by Ralph Leonard — from 2021. I don’t know enough to endorse his views or otherwise. But I was interested to read the piece.

It may be, among other things, extremely banal and trivial to observe— or in the case of the Palestinians mourn — the supposed ‘immaculate conception’ of Der Judenstaat on its 73rd year. Nonetheless, there is enough perspective to contemplate on some questions that may be worn out, but are still pressing for us in our present. Is Zionism a national liberation movement for Jews or a settler colonial project (or both)? Has it made Jews more or less safe? Has the ancient scourge of anti-Semitism been cured by it? Have Jews been ‘normalised’ in the world by it? Is Israel a ‘light unto the nations’, or is it just another rotten nation state in a long line built on and maintained by violence?

Jewish people, as is par the course, occupy all sides of this argument. There are Zionists who earnestly believe Israel is the closest thing in history to a man made miracle. Other Zionists pander to Western prejudices on the ‘Muslim question’ in Europe by portraying Israel, the “villa in the jungle”, as on the front line in the ‘clash of civilisations’ against the Muslim hordes. There are Hasidic sects who regard Israel as an obscene blasphemy and only with the arrival of the Messiah can truly ‘authentic’ Jewish state come into an existence. There are leftist and progressive Jews who feel guilt and shame that in the name of the Jewish people a settler state was erected on the ruins of so many Palestinian Arab towns and villages. Conversely, there are some Jews who don’t have a guilty conscience at all. Indeed they wish to evict more Palestinians with a divine mandate and collaborate with fanatical evangelical Christians to expedite the end of days. And let’s not forget the disillusioned liberal Zionist for whom Israel was paradoxically a means for them to comfortably assimilate into the liberal democratic West. They blame Netanyahu and his cronies for being the gravedigger of the Zionist dream and making Israel resemble more and more a shtetl with an air force.

As is always the case with Israel, one has to live with multiple contradictions pulsating in your head. In fact, to echo Flaubert, contradiction is what keeps one’s sanity in place. Do I sometimes wish that Theodore Herzl, Max Nordau, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion had never convinced Jews and Gentiles that the answer to the ‘Jewish Question’ was to create an irredentist Jewish state on Arab land in West Asia? Yes. Does that then mean I desire the ‘obliteration’ of the Israeli nation and society? Of course not. Was there something fundamentally absurd in bourgeois and petit-bourgeois European Jews being intoxicated by the mad rhythms of messianic blood and soil mysticism? Yes. Do I wish the German revolution of 1918–19 had succeeded, thus averting the rise of fascism, preventing the Shoah, and hopefully charting out a better course for the Jewish question? Absolutely. Am I angered, horrified and disgusted at seeing a whole new generation of Palestinians being born into dispossession and/or occupation and exile already suffered by their grand parents, great-grand parents, and soon to be great-great-grand parents? Damn right I am! …

Moreover, the Jewish state rules over millions of non-Jews, treating them as dependents and subjects, not citizens, and continuing to dispossess and humiliate them, intensifying their already impassioned enmity towards it. They don’t see the justice of being gracious recipients of ‘Jewish sovereignty’. Because of this Israel’s ‘international legitimacy’ is always fragile. How long until even America’s wall to wall, blind support for Israel whatever it does begins to crack? To put it simply, to talk of Israel as the ‘solution’ to the alienation of galut is mistaken. As Christopher Hitchens once observed, Israel is not “the alternative to the diaspora. It is part of the diaspora.” The global Jewish diaspora is around 18 million, scattered across many nations and continents. Only in Israel do Jews live as dangerously they do, the bloodshed of the recent past fresh in their minds, quietly fearing when the next round will kick off. Only in Israel do Jews live in range of rockets fired by Judeophobes. Only in Israel do Jews have to live with barbed wire fences, bomb shelters, iron walls, machine guns, iron dome and specially designed bomb proof buses underwritten by diaspora and Gentile generosity. Only in Israel is there talk of a second Shoah befalling Jews if Iran acquires nukes. What is the old cliché about Jews and irony?

Heaviosity half-hour

The people’s republic of Walmart

HT: Martin Turkis, for suggesting I check out this book.

I’m enjoying the book which argues — contra Hayek — that the success of a firm like Walmart shows the practicality of central planning! The thing the author’s don’t highlight is that while Walmart and other very large companies are indeed, centrally planned, they are bounded on all sides by markets — for products, capital, labour and human capital, and for technology. And that gives them a great deal of information which is not available in a centrally planned economy. Yet it is true that we have pioneered new IT systems which establish highly productive feedback relations between the edge of systems and their centre. I riffed on this in a forward to a discussion paper by Deloitte in 2014.*

Over eighty years ago, a young Friedrich Hayek issued an historic challenge to economists who’d argued that a socialist central planner could replicate the utopian efficiency of a ‘perfect market’. Hayek argued that even if central planners were well motivated, they could not replicate a perfect market without perfect information – which they could never have. He was vindicated as an old man when the Soviet Union collapsed. Hayek was the first and most successful champion for ‘the edge’.

Since then, the economic dynamics of the Internet have increasingly demonstrated the importance of the edge. The distributed intelligence of peer production on platforms like Wikipedia and open-source software projects challenge more hierarchical forms of production.

But, as this report documents, a new mode of production is growing in importance. In this mode the centre provides a platform of services to the edge, usually ‘in the cloud’, with an ongoing data stream between the platform and the edge.

This vastly enriched data flow means the centre can be better informed about circumstances at the edge than was ever dreamt of in Hayek’s philosophy. This doesn’t justify throwing the switch back to central planning, though it is,as this report documents, already inspiring new departures in business and elsewhere.

* As a paid-up member of The Cathedral, Deloitte inhabits the infinite present, which means that nine-year-old discussion papers get erased from their website. But I’ve hoisted it here if you’re interested.

Be that as it may, here is a fun section from The People’s Republic of Walmart.

Sears’s Randian Dystopia

It is no small irony that one of Walmart’s main competitors, the venerable, 120-plus-year-old Sears, Roebuck & Company, destroyed itself by embracing the exact opposite of Walmart’s galloping socialization of production and distribution: by instituting an internal market.

The Sears Holdings Corporation reported losses of some $2 billion in 2016, and some $10.4 billion in total since 2011, the last year that the business turned a profit. In the spring of 2017, it was in the midst of closing another 150 stores, in addition to the 2,125 already shuttered since 2010—more than half its operation—and had publicly acknowledged “substantial doubt” that it would be able to keep any of its doors open for much longer. The stores that remain open, often behind boarded-up windows, have the doleful air of late-Soviet retail desolation: leaking ceilings, inoperative escalators, acres of empty shelves, and aisles shambolically strewn with abandoned cardboard boxes half-filled with merchandise. A solitary brand-new size-9 black sneaker lies lonesome and boxless on the ground, its partner neither on a shelf nor in a storeroom. Such employees as remain have taken to hanging bedsheets as screens to hide derelict sections from customers.

The company has certainly suffered in the way that many other brick-and-mortar outlets have in the face of the challenge from discounters such as Walmart and from online retailers like Amazon. But the consensus among the business press and dozens of very bitter former executives is that the overriding cause of Sears’s malaise is the disastrous decision by the company’s chairman and CEO, Edward Lampert, to disaggregate the company’s different divisions into competing units: to create an internal market.

From a capitalist perspective, the move appears to make sense. As business leaders never tire of telling us, the free market is the fount of all wealth in modern society. Competition between private companies is the primary driver of innovation, productivity and growth. Greed is good, per Gordon Gekko’s oft-quoted imperative from Wall Street. So one can be excused for wondering why it is, if the market is indeed as powerfully efficient and productive as they say, that all companies did not long ago adopt the market as an internal model.

Lampert, libertarian and fan of the laissez-faire egotism of Russian American novelist Ayn Rand, had made his way from working in warehouses as a teenager, via a spell with Goldman Sachs, to managing a $15 billion hedge fund by the age of 41. The wunderkind was hailed as the Steve Jobs of the investment world. In 2003, the fund he managed, ESL Investments, took over the bankrupt discount retail chain Kmart (launched the same year as Walmart). A year later, he parlayed this into a $12 billion buyout of a stagnating (but by no means troubled) Sears.

At first, the familiar strategy of merciless, life-destroying post-acquisition cost cutting and layoffs did manage to turn around the fortunes of the merged Kmart-Sears, now operating as Sears Holdings. But Lampert’s big wheeze went well beyond the usual corporate raider tales of asset stripping, consolidation and chopping-block use of operations as a vehicle to generate cash for investments elsewhere. Lampert intended to use Sears as a grand free market experiment to show that the invisible hand would outperform the central planning typical of any firm.

He radically restructured operations, splitting the company into thirty, and later forty, different units that were to compete against each other. Instead of cooperating, as in a normal firm, divisions such as apparel, tools, appliances, human resources, IT and branding were now in essence to operate as autonomous businesses, each with their own president, board of directors, chief marketing officer and statement of profit or loss. An eye-popping 2013 series of interviews by Bloomberg Businessweek investigative journalist Mina Kimes with some forty former executives described Lampert’s Randian calculus: “If the company’s leaders were told to act selfishly, he argued, they would run their divisions in a rational manner, boosting overall performance.”

He also believed that the new structure, called Sears Holdings Organization, Actions, and Responsibilities, or SOAR, would improve the quality of internal data, and in so doing that it would give the company an edge akin to statistician Paul Podesta’s use of unconventional metrics at the Oakland Athletics baseball team (made famous by the book, and later film starring Brad Pitt, Moneyball). Lampert would go on to place Podesta on Sears’s board of directors and hire Steven Levitt, coauthor of the pop neoliberal economics bestseller Freakonomics, as a consultant. Lampert was a laissez-faire true believer. He never seems to have got the memo that the story about the omnipotence of the free market was only ever supposed to be a tale told to frighten young children, and not to be taken seriously by any corporate executive.

And so if the apparel division wanted to use the services of IT or human resources, they had to sign contracts with them, or alternately to use outside contractors if it would improve the financial performance of the unit—regardless of whether it would improve the performance of the company as a whole. Kimes tells the story of how Sears’s widely trusted appliance brand, Kenmore, was divided between the appliance division and the branding division. The former had to pay fees to the latter for any transaction. But selling non-Sears-branded appliances was more profitable to the appliances division, so they began to offer more prominent in-store placement to rivals of Kenmore products, undermining overall profitability. Its in-house tool brand, Craftsman—so ubiquitous an American trademark that it plays a pivotal role in a Neal Stephenson science fiction bestseller, Seveneves, 5,000 years in the future—refused to pay extra royalties to the in-house battery brand DieHard, so they went with an external provider, again indifferent to what this meant for the company’s bottom line as a whole.

Executives would attach screen protectors to their laptops at meetings to prevent their colleagues from finding out what they were up to. Units would scrap over floor and shelf space for their products. Screaming matches between the chief marketing officers of the different divisions were common at meetings intended to agree on the content of the crucial weekly circular advertising specials. They would fight over key positioning, aiming to optimize their own unit’s profits, even at another unit’s expense, sometimes with grimly hilarious result. Kimes describes screwdrivers being advertised next to lingerie, and how the sporting goods division succeeded in getting the Doodle Bug mini-bike for young boys placed on the cover of the Mothers’ Day edition of the circular. As for different divisions swallowing lower profits, or losses, on discounted goods in order to attract customers for other items, forget about it. One executive quoted in the Bloomberg investigation described the situation as “dysfunctionality at the highest level.”

As profits collapsed, the divisions grew increasingly vicious toward each other, scrapping over what cash reserves remained. Squeezing profits still further was the duplication in labor, particularly with an increasingly top-heavy repetition of executive function by the now-competing units, which no longer had an interest in sharing costs for shared operations. With no company-wide interest in maintaining store infrastructure, something instead viewed as an externally imposed cost by each division, Sears’s capital expenditure dwindled to less than 1 percent of revenue, a proportion much lower than that of most other retailers.

Ultimately, the different units decided to simply take care of their own profits, the company as a whole be damned. One former executive, Shaunak Dave, described a culture of “warring tribes,” and an elimination of cooperation and collaboration. One business press wag described Lampert’s regime as “running Sears like the Coliseum.” Kimes, for her part, wrote that if there were any book to which the model conformed, it was less Atlas Shrugged than it was The Hunger Games.

Thus, many who have abandoned ship describe the harebrained free market shenanigans of the man they call “Crazy Eddie” as a failed experiment for one reason above all else: the model kills cooperation.

“Organizations need a holistic strategy,” according to the former head of the DieHard battery unit, Erik Rosenstrauch. Indeed they do. But is not society as a whole an organization? Is this lesson any less true for the global economy than it is for Sears? To take just one example: the continued combustion of coal, oil and gas may be a disaster for our species as a whole, but so long as it remains profitable for some of Eddie’s “divisions,” those responsible for extracting and processing fossil fuels, these will continue to act in a way that serves their particular interests, the rest of the company—or in this case the rest of society—be damned.

In the face of all this evidence, Lampert is, however, unrepentant, proclaiming, “Decentralised systems and structures work better than centralised ones because they produce better information over time.” For him, the battles between divisions within Sears can only be a good thing. According to spokesman Steve Braithwaite, “Clashes for resources are a product of competition and advocacy, things that were sorely lacking before and are lacking in socialist economies.”

He and those who are sticking with the plan seem to believe that the conventional model of the firm via planning amounts to communism. They are not entirely wrong.

Interestingly, the creation of SOAR was not the first time the company had played around with an internal market. Under an earlier leadership, the company had for a short time experimented along similar lines in the 1990s, but it quickly abandoned the disastrous approach after it produced only infighting and consumer confusion. There are a handful of other companies that also favor some version of internal market, but in general, according to former vice president of Sears, Gary Schettino, it “isn’t a management strategy that’s employed in a lot of places.” Thus, the most ardent advocates of the free market—the captains of industry—prefer not to employ market-based allocation within their own organizations.

Just why this is so is a paradox that conservative economics has attempted to account for since the 1930s—an explanation that its adherents feel is watertight. But as we shall see in the next chapter, taken to its logical conclusion, their explanation of this phenomenon that lies at the very heart of capitalism once again provides an argument for planning the whole of the economy.

Excruciating

Imre Lakatos

I ran into this intriguing letter from the well-known philosopher of science Imre Lakatos to LSE in 1970. At the time Maoist aspirations for a revolution in culture from the students up (or perhaps that is down) were all the rage, not entirely unlike various identitarian excesses today. In his letter Lakatos draws the distinction between the students claims that were and were not justified very deftly. So I thought might be interested in it.

Dear Director,

The Majority Report of the Machinery of Government Committee . . . contains the principle that students, as well as staff, should determine the general academic policy of the School. This principle is clearly inconsistent with the principle of academic autonomy, according to which the determination of academic policy is exclusively the business of academics of some seniority. The implementation of this latter principle has been achieved - and sustained - in a long historical process. I came from a part of the world where this principle has never been completely implemented and where during the last 30-40 years it has been tragically eroded, first under Nazi and then under Stalinist pressure. As an undergraduate I witnessed the demands of Nazi students at my University to suppress 'Jewish-liberal- marxist influence5 expressed in the syllabuses.

I saw how they, in concord with outside political forces, tried for many years - not without some success - to influence appoint- ments and have teachers sacked who resisted their bandwagon. Later I was a graduate student at Moscow University when resolu- tions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party determined syllabuses in genetics and sent the dissenters to death. I also remember when students demanded that Einstein's 'bourgeois relativism' (i.e. his relativity theory) should not be taught, and that those who taught such courses should confess their crimes in public. There can be little doubt that it was little more than coincidence that the Central Committee stopped this particular campaign against relativity and diverted the students' attention to mathematical logic and mathematical economics where, as we know, they suc- ceeded in thwarting the development of these subjects for many years. (I am fortunate that I did not have to witness the humiliation of University Professors by the students of Peking University during their 'cultural revolution'.)

Invoking these ghastly memories may seem out of place in this country. It will be said that here there is no political force or motivation behind students' demands. Unlike the demands of Hitler's, Stalin's and Mao's youth, their aim is to improve rather than erode the university tradition of informed research and competent teaching.

But is this so? The 'Minority Report' which the LSE Students' Union adopted, has an underlying philosophy which may have been taken directly from the posters of Mao's 'Cultural Revolution'. As Adelstein, one of its authors, put it (The Times, 18.3.68):

Student representation on governing bodies is only the beginning , and representation can be good or bad - it can give a false sense of unity. The next thing is for students to begin to run their own courses, initially through their own societies, and then to demand that they should run a particular part of a course: its content, how it is taught, and who teaches it.

The next step is for students to appoint their own teachers and to do some teaching themselves. Ultimately , students should work for a certain amount of the time. Academic and intellectual problems become meaningful if they are associated with practical life I accept the word militancy, but it means for me that one is prepared to consider any action that will achieve one's end, which is in accordance with one's ends. One would not rule out any mode of action because it has not been accepted in the past We do initiate unconstitutional action.

We do not accept constitutional limits because they are undemocratic. When democracy fails, this is the only way of doing it . . . (my italics).

Should one leave such an extremist manifesto of a member of the Machinery of Government Committee of the London School of Economics without comment? Can one accept the 'beginning' stage of this programme without argument, without having to fear that this is only the thin end of the wedge? According to the Majority Report, we can. I shall argue that we cannot.

I

The crucial shortcoming of the Majority Report is that it does not demarcate between two completely different sets of student demands. The first set of demands are for free expression of student complaints and criticism and for guarantees that these complaints and criticism will get a proper hearing ; also for participation in decision-making in matters in which they are nearly, equally, or even more competent than the academic staff. These demands were originally opposed - and in many places still are - by the champions of the paternalistic in loco parentis conception of University authority, but they no longer meet opposition at the LSE, in my opinion rightly so.

The second set of demands are completely unjustified demands for student power - as opposed to demands for student rights of criticism - concerning appointments, establishing new chairs, positions, designing syllabuses and, in general, concerning the content of teaching and research. The policy of the 'revolutionaries' is to blur the distinction.

This policy has achieved considerable success, mainly because of the widespread but unproven assumption that if it had not been for 'revolutionary' militancy, even the justified demands might not have been satisfied to the degree they are satisfied now. But whether this is true or not, it does not alter the plain and sad fact that these militants have no interest whatsoever in the apolitical and constructive student demands. They only advocate the demands for freedom for political expediency, in order to win the students' support for their demands for (their) power. They are turning surreptitiously the justified revolt against academic paternalism into a political revolt against academic autonomy. This is why it is so important to draw a sharp line between the two kinds of demands.

I didn’t read the whole letter which is quite long, but as usual the blue button will take you there should you wish.