We're not on a slippery slope: we're in free fall

So says Stanford's Larry Diamond. And lots of other things to think about and enjoy.

Fancy a tour of Sydney?

Sydney wears its history lightly. Too lightly. It dazzles with its harbour, hums with its cosmopolitan energy, and yet, beneath the surface, lies a past as layered as the sandstone beneath it. The trouble is, most of us never really get to see it. That’s where my daughter’s boyfriend Conner Bethune’s Australiana Tours comes in.

Conner doesn’t do things by halves and has been researching for over a year. He invites you to step beyond the postcard views and into the stories. The rebels and rogues, the dreamers and doers.

This Sydney Walking Tour is a journey through time, carefully curated to take you from 200,000 BC to 2000 AD in as many years (I think this is a misprint, as elsewhere it says three hours and people have certainly finished the tour in the same month they started it. Even so, leaving nothing to change, a rescue helicopter is on stand-by.) It’s a living, breathing narrative of Australia’s past (this bit checks out because any living narrative is usually a breathing narrative — please pay attention).

It’s not just about the big events. It’s about the characters who lived them—the misfits and masterminds, the stubborn, the brilliant, the bold [not to be mistaken for the rebels and rogues, the dreamers and doers ed].

At this point, you might be wondering: This sounds like it costs a fortune.

Well, it is run on a "pay what you feel" model. He offers an engaging, high-quality tour, and you decide what it’s worth. The more you pay, the more you get to feel. No pressure, no barriers—just the chance to experience the story of Australia’s premier city.

WHEN: 10.00 am Sundays; 9.00 am Saturdays.

WHERE: Just outside Museum Station, Sydney

HOW: 3-hour tour, including a coffee break at a local cafe

NEXT SESSION: 10.00 am Sunday 23 February 2025.

28 reviews: all five star!!

Juries in the political system: surely not?

The British think tank Radix asked me to give an after-dinner speech to a conference of NGOs involved in promoting democracy which I delivered by teleconference.

Almost all democracies mix two approaches: representation by election and representation by sampling. But in modern politics, we’ve sidelined the latter, except in the judicial system. Elections don’t just select representatives; they shape the kind of people who rise to power. The system favours self-promotion, rewards spin, and turns politics into a competition for attention rather than a forum for governing. We assume elections will keep politicians accountable, but in practice, they reinforce a cycle where honesty is a liability and manipulating people takes priority.

Representation by sampling works differently. When people are selected by lottery to deliberate on political issues, they tend to engage with one another in ways that cut through party lines and ideological divides. I explore examples of how this has worked, from ancient Athens to modern citizen assemblies, and outline a proposal: a standing Citizens’ Assembly to sit alongside existing institutions, providing an independent check on government.

This isn’t about replacing elections, but about balancing them with another democratic principle—one we’ve neglected for too long. I mention a documentary on the establishment of the Michigan Independent Citizens' Redistricting Commission which is . And you can find the audio at Spotify:

After completing Conner’s tour, Paul Keating returns home …

Free fall not slippery slope: Larry Diamond

I recall, not so long ago wondering how Pericles of Athens managed to dominate the 5th century BC Athenian government for so long. What was the Athenians’ equivalent to a prime minister or a president? Of course there was no such office. Athens’ democracy understood itself as surviving in the teeth of tyranny and oligarchy. Pericles was one of ten generals and he was repeatedly returned in elections but he gained his ascendancy because of his political skills which, I presume, were built on the bedrock of his performance in the assembly. The Roman Republic was no different in this sense — established as an anti-monarchy with officeholders enjoying office by twos. Consuls were the highest office and there were two elected at a time. They ruled together giving each an effective veto over the other.

Modern democracies are all democratised constitutional monarchies (whether the monarch is hereditary (as in Britain and most Commonwealth countries) or elected (as in the US and many congressional systems). They were democratised by subjected to progressively greater checks and balances. And yet, as we’re seeing now, however many checks and balances we’ve imposed upon the single point of sovereignty, it remains as a single point of failure.

In any event, here is prominent scholar of democracy — Larry Diamond arguing that “Trump's America Is in a Free Fall—Not a Slippery Slope—to Tyranny.”

“There is no universally accepted definition of a constitutional crisis, but legal scholars agree about some of its characteristics. It is generally the product of presidential defiance of laws and judicial rulings. It is not binary: It is a slope, not a switch. It can be cumulative, and once one starts, it can get much worse.” — Adam Liptak

A mere month into his second term as president, Donald Trump and his loyalists in government are already posing grave risks to the legal, constitutional, and normative foundations of American democracy. The threat Trump poses is much more severe than during his first term...

This time, there are no weighty figures in his administration willing to put the Constitution above personal loyalty to him. This time, Trump and his MAGA team have had four years to plan a more concerted assault on democratic checks and balances... And this time, Trump and his loyalists have a long agenda of revenge against a wide range of actors who they believe have wronged them and who they now want to punish and subdue.

Having won the presidency fair and square, Donald Trump has earned the right to propose, and in many cases to implement, radical new policy directions. But he does not have the right to violate the law, the Constitution, and the civil liberties of Americans in doing so...

First, the crisis of American democracy is now squarely upon us. Multiple illegal and unconstitutional acts are happening, and the guardrails that check and restrain authoritarian abuse are rapidly falling away...

Second, it is going to get a lot worse. Trump is following an authoritarian playbook for destroying constitutional government that has been widely deployed over the last two decades... The pathway to authoritarianism in America lies in subverting our constitutional checks and balances. Trump has moved rapidly on that front and there will be much more to come...

Third, democratic backsliding is moving quickly now in part because of the lack of resistance. Part of this void owes to confusion and division within the opposition (the Democrats), part to opportunism and submission among congressional Republicans, and part to the tactical decisions of key actors in business, the media, and the bureaucracy to comply in advance, again partly out of opportunism but also heavily out of fear. Fear is the common denominator in all of this—palpable, paralyzing, and quite justifiable fear. Fear now stalks the land. This is the most visceral indication that America has entered an existential era for the future of democracy...

The threats to American democracy in the United States are now immediate, serious, and mounting by the day. However, it is possible to contain them. Doing so will require a national, multifront bipartisan strategy. But time is of the essence... The key is to unite in defense of our democratic checks and balances, rather than to argue that every one of Trump's policy initiatives is illegitimate. The markets will take care of stupid and self-harming tariff policies. They will not on their own save American democracy...

Donald Trump was not truthful when he said he just wanted to be a dictator on Day One. He aspires to make it last for four years, and probably well beyond... But it is important to separate policy directions that are cruel and heartless, and that undermine even the president's own stated goals, from actions that are anti-democratic in law or in motive and effect...

It may be specious to claim that this is being done to balance the books when foreign aid is barely 1% of the federal budget. But it is not necessarily unconstitutional, or even undemocratic, for presidents to do cruel, shortsighted, and deceitful things...

All of this becomes illegal, unconstitutional, and undemocratic when it is done unilaterally and arbitrarily, bypassing Congress and its preeminent authority to appropriate funds... The president does not have the authority on his own to suspend all foreign aid flows, much less terminate them, much less eliminate an entire agency established and annually funded by Congress...

The catalogue of Trump's presidential actions that defy the law and the Constitution is rapidly growing. On the very first day of his new presidential term, Trump ordered an end to birthright citizenship for undocumented immigrants, seeking with the mere stroke of a pen to set aside the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Four federal judges have blocked that executive order... On Friday, Jan. 24, Trump fired 17 inspectors general in government departments and agencies...

The most ominous question is what will happen if the federal judiciary arrives at a clear and final ruling that some (or even most) of these acts are unconstitutional or illegal, and then Trump carries on with them defiantly... "There has been no clear example of 'open presidential defiance of court orders in the years since 1865.'" That could now change...

The federal district judge who ordered the above ruling warned that defiance of court orders could cause individuals to be held in criminal contempt of court. That would seem to be an important step toward restoring the founding vision of a federal government with three distinct branches and reciprocal checks and balances. We need to realize the most important insight of James Madison's constitutional genius, the dictum that "ambition must be made to counteract ambition." But in tweeting on Sunday, Feb. 9, that "Judges aren't allowed to control the executive's legitimate power," Vice President JD Vance may have been laying the groundwork to restore the United States to an era of constitutional chaos that we have not seen since the Civil War...

With regard to the third branch of government, the judiciary, the ultimate nightmare would be if Trump defied a final judgement on a matter by the Supreme Court. But if the Supreme Court were to radically embrace the theory of the unitary executive by overturning hallowed precedents, for example on presidential impoundment or the illegal dismissal of federal officials, that would also have chilling implications for the future of American democracy...

The last line of defense is civil society. Liberal democracy has survived and thrived in wealthy capitalist economies because of the density and vigor of independent policy organizations, interest groups, religious institutions, media, think tanks and universities, and the strength of independent businesses that do not depend on the state for their markets. These form a thick layer of autonomous capacity to organize and mobilize in the face of abuse, illegality, and incipient tyranny. But in this century, this vital Tocquevillian arena of democratic vitality in the United States has been badly strained by intense political polarization and declining trust in one another and in all the institutions of government...

Many business leaders backed Trump politically, sincerely believing that his intention to cut corporate and personal income taxes and reduce government regulation would spark a new era of investment and growth. These business leaders want to privilege the financial interests and economic policy preferences that motivated their often reluctant political support for Trump. They were never happy with the “DEI agenda” imposed upon them by left-of-center administrations and constituencies, and hoped that all of Trump’s imperial excesses will prove to be mostly bark and little bite. They hardly seem ready for the ferocity of what is coming, and many analysts are questioning how much they will care until the chaos of an authoritarian presidency run amok begins to unravel economic and social stability in the U.S.—which it will.

Nothing to see here — except “bipartisan gaslighting”

Quinn Slobodian on the three strains of Trumpery

Quinn Slobodian is a Canadian historian who’s documented the the international dimensions and remarkable achievements of Hayek’s neoliberalism in Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism and the eye popping aspirations of the anarcho-capitalists in Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy. They’re both striking books which I recommend.

[W]e are witnessing something new: the convergence of three strains of politics that have never simultaneously been this proximate to power. Those projects come from different but related places: the Wall Street–Silicon Valley nexus of distressed debt and startup culture; anti–New Deal conservative think tanks; and the extremely online world of anarchocapitalism and right-wing accelerationism. Within the new administration, each strain is striving to realize its desired outcome. The first wants a sleek state that narrowly seeks to maximize returns on investment; the second a shackled state unable to promote social justice; and the third, most dramatically, a shattered state that cedes governing authority to competing projects of decentralized private rule. We are watching how well they can collaborate to reinforce one another. The future condition of the government—and by extension the country—depends on how far the dynamo spins. …

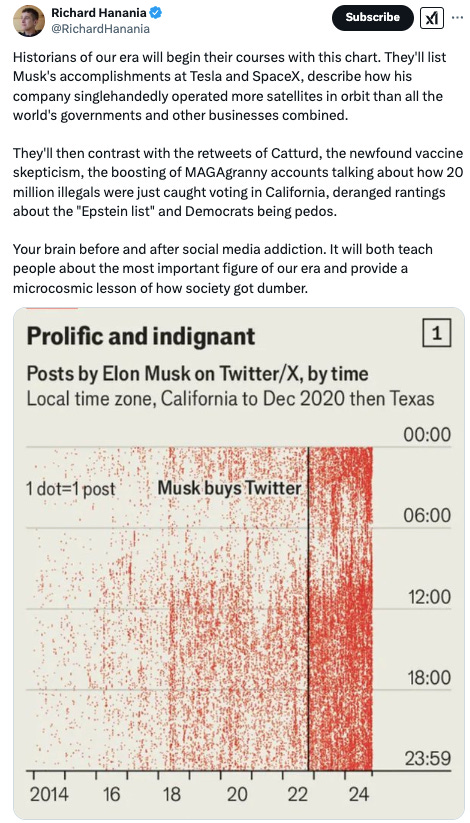

Though [Twitter]’s value sharply declined, it also added to the mercenary mystique that Musk had built up over the past decade by managing at least a half dozen businesses under the principle that you can keep services running even as you “delete” (his favorite word) many of the humans involved. …

One could stop here and conclude that Musk simply wants to turn the government from being an exceptionally bad corporation to one that is marginally less bad—a managerial dictatorship, but a temporary one. This is the version of the story that convinced Democratic lawmakers and financial columnists, who have long promoted the analogy between citizens and consumers, that DOGE could be a good idea. “Streamlining government processes and reducing ineffective government spending should not be a partisan issue,” announced Congressman Jared Moskovitz (D-FL) when he joined the DOGE caucus in December. “If Doge can actually unleash digital reform in the US government, and in a non-corrupt manner, that would be an unambiguously good thing,” Gillian Tett wrote last month in the Financial Times. This model is also consonant with the Singaporesque sovereign wealth fund announced last week, and with the federal backstop announced two weeks ago for enormous AI infrastructure funds like the Stargate Project, involving OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank. Musk would attack the state to save it. …

The second way to understand the DOGEstorm is not through Musk but rather through the more systematic approach of Russell Vought at the Office of Management and Budget and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose operations he ground to a halt this past weekend, firing dozens. … Vought has said that America is in the “late stages of a complete Marxist takeover” that needs to be reversed aggressively by putting government employees “in trauma,” treating them as “villains,” and sending “power away from Washington and back to America’s families, faith communities, local governments, and states.” … The point, as Steve Bannon has stressed for years, is to deconstruct the administrative state, leaving in its place a government that rules intensively but not extensively. This project has had a fairly stable intellectual lineage. …

The third program that underpins the present moment is often described as a project of right-wing accelerationism. That term is usually associated with Curtis Yarvin, the former computer programmer and amateur poet who was graced with a long interview in The New York Times just after the election. …

What do they see? Right-wing accelerationists imagine existing sovereignty shattering into what Yarvin, writing under the pen name Mencius Moldbug, calls a “patchwork” of private entities, ideally governed by what one might call technomonarchies. Existing autocratic polities like Dubai serve as rough prototypes for how nations could be dismantled into “a global spiderweb of tens, even hundreds, of thousands of sovereign and independent mini-countries, each governed by its own joint-stock corporation without regard to the residents’ opinions.” These would be decentralized archipelagoes: fortified nodes in a circuitry still linked by finance, trade, and communication. Think of the year 1000 in Middle Europe but with vertical take-off and landing taxis and Starlink internet. Yarvin expressed the essence of the worldview recently when he enthused over Trump’s proposal to ethnically cleanse the Gaza Strip and rebuild it as a US-backed colony securitized as an asset and sold to investors—as he called it, “the first charter city backed by US legitimacy: Gaza, Inc. Stock symbol: GAZA.”

Accelerationists do not want merely to make government more efficient, nor simply to prevent it from pursuing redistribution or propagating progressive values. “Speed up the breakdown” is the mantra. Their objective is not to tame or starve the beast but to kill it. Adherents to this extreme ideology are obviously a minority, and it’s not clear at all that Musk himself shares it, let alone Trump. But even if they don’t, DOGE’s actions are helping to unsettle the division between public and private authority. Libertarians have long seen gated communities as laboratories of private government and reminisced about the law and order of the supposedly stateless Western frontier. Musk’s move to reboot the company town by incorporating Starbase, Texas could be seen as a first step toward a world where private actors make laws and jurisdictions that fit their personal needs. …

In the paradigm of empire-by-contractor, the state grants concessions to mining or satellite enterprises. This would be a throwback to the nineteenth century, when the freebooter William Walker invaded Honduras, The Englishman James Brooke became the “Raj of Sarawak,” and, as Atossa Araxia Abrahamian has described, the Michigander John Munro Longyear staked out a patch of Arctic and fashioned himself as the “King of Spitsbergen” in what is now Svalbard. “Countrypreneurship” already has a foothold in the private enclave of Próspera in Honduras. The former Andreessen Horowitz partner Balaji Srinivasan has sketched blueprints of “the Network State” for his 1.1 million followers on X, describing “startup societies” as opt-in collectives with votes defined by share size and CEOs as leaders. He has praised Trump’s early executive orders as “a fusillade of legal cruise missiles” that were “meticulously planned to strike every single source of blue power, simultaneously, both in the US and abroad.”

US state sovereignty will be eroded to some degree by the time the dust settles on Silicon Valley Leninism and the computers of the bureaucracy boot up to a blank screen. This prospect will rightfully concern those who believe in constitutional constraints and the need for a state that does more than fund weapon systems, finance AI data centers, and cut paychecks for border police. For sympathetic observers, however, the goings-on in Washington are inspiring the same exhilaration that the anarchocapitalist economist Murray Rothbard felt when he watched the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It was, he said, “a particularly wonderful thing to see unfolding before our very eyes, the death of a state.”

Eco books to avoid

As usual, I agree with Noah Smith. Here are four eco books to avoid and why.

Books to avoid

And here we come to my “anti-reading” list.4 I’ll try to keep it short, but there are some pop econ books whose ideas and argumentation are so poor that the average person will not benefit from reading them.

Power and Progress, by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson

I wrote a really long and mostly negative review of this book a year ago:

In a nutshell, this book says that the Luddites were right, and that automation is bad for average people. The history and evidence to support this argument are both highly questionable, and sometimes just plain sloppy. Meanwhile, the authors’ policy recommendation is that tech businesses should be incentivized or compelled to invent technologies that complement human labor, instead of ones that automate it away — as if any entrepreneur or engineer knows that in advance. The whole book isn’t very credible, and feels more than anything like a jeremiad against the tech-bro class.

Debt: The First 5000 Years, by David Graber

I can hardly believe it was 11 years ago, but in my early days as a fiery and irritable blogger I once wrote a scathing review of David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years. Just for fun, let me quote from that review:

[T]he main problem with Debt: The First 5000 Years is that after slogging through all 560 pages, I can't for the life of me tell what point it's trying to make about the phenomenon of debt…Debt is a sprawling, rambling, confused book…Graeber continually talks around the idea of debt…Perhaps capitalism is a rotten, inhumane system that kills relationships, rewards violence and trickery, and enslaves us all to the brutal logic of the market before inevitably destroying the planet. Or perhaps not. But either way, there's little insight to be gained by reframing the issue in terms of debt.

I don’t think I can do better than that summary here.

The Deficit Myth, by Stephanie Kelton

No, I haven’t read this book! I have a limited time to exist and be awake in this universe, and I am not going to spend it reading a 336-page book about MMT. For those who don’t know, MMT is a pseudo-theory5 that pushes infinite government deficits without concretely specifying why deficits are safe or how they think the economy actually works. I haven’t read The Deficit Myth, but I have read a couple of MMT papers, and that was quite enough to get the gist:

When economists do read Kelton’s book, they come away with the same conclusion: there’s just no actual theory there. Here’s what a pair of economists from the Banque de France had to say:

Overall, it appears that MMT…is a more that of a political manifesto than of a genuine economic theory…As Hartley (2020) notes, MMT “is not a falsifiable scientific theory: it is rather a political and moral statement by those who believe in the righteousness – and affordability – of unlimited government spending to achieve progressive ends”.

And here’s Giacomo Rondina of the University of California San Diego:

[M]y reading of the MMT academic literature suggests that MMT has not yet provided a fully coherent theory of the macroeconomics of government intervention…As a consequence, many macroeconomic practitioners “peeking under the hood” (cit.) of MMT cannot help but feel a sense of frustration in understanding how exactly the engine is supposed to work.

I salute these brave souls for being able to endure more MMT nonsense than I was. In any case, my friendly advice is to do what I did instead, and avoid spending mental effort on this stuff.

Freakonomics, by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner

The years have not been kind to poor old Freakonomics. The blockbuster result that made the book famous — that abortion caused the big crime drop in America, by reducing the number of unwanted children who grow up to commit lots of crimes — turned out to probably be false. Some other economists found a coding error in the famous abortion-crime study that totally invalidated the result. The authors tried to argue that it still held, using some more complicated methods, but these methods weren’t very credible or convincing. Meanwhile, the other chapters in the book are often more about sociology and anthropology than economics, and the chapters that are about economics tend to be about results that are cute but ultimately not that important. Freakonomics is a fun read, but at this point it’s more of a historical artifact than a guide to good economics.

Change in Europe?

The new German Chancellor — From October last year.

Fear and the desperate hope of being able to portray himself as a “peace chancellor” shortly before Germany’s federal election next year have become Scholz’s dominant motives. But “fear is the mother of all cruelty,” as Michel de Montaigne, the sixteenth-century French philosopher, put it. French President Emmanuel Macron has no doubt read Montaigne and understands that warning.

Instead of acting decisively at Ramstein, Scholz had a nice coffee with Biden, shortly before the US president was awarded the special level of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. But that award ceremony was a moment that united Great Britain, France, Germany, and the US merely in nostalgia, not in defining the decisive action and sense of purpose which Europe needs today.

Indeed, the ceremony recalled nothing so much as how Germany’s government behaved in the years before the fall of the Berlin Wall and reunification, before the division of Europe was overcome, before the war in Ukraine. The old Europe of the Cold War sought comfort in the past and confidence in the solitary US leadership that defined the era. Europeans forging their own decisions were rarely even an afterthought back then. For example, did no one even think of inviting Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk to the meeting in Berlin?

Biden’s flight back to Washington following the aborted Ramstein conference and the diminished meeting in Berlin’s Chancellery may take on an almost symbolic significance in the future: the last Atlanticist US president for a long time bidding farewell to Europe. And the Europeans, without leadership and without the slightest idea of what lies ahead, waving goodbye to him, dreamily reminiscing about earlier times.

The Hungarian playbook

From Peter Browne in Inside Story.

The backers of Donald Trump’s attack on his country’s institutions — an assortment of plutocrats, activists, far-right think tanks, conservative academics and cynical media moguls — hold a constellation of not always compatible beliefs. Their ranks range from intellectuals like the Catholic political scientist Patrick Deneen, who wants to replace the hated liberal meritocracy with a new elite made up of people like him, to the anti-egalitarian blogger Curtis Yarvin, who favours a United States run by a monarch. Somewhere in between are the hardheads at the Heritage Foundation, authors of the Project 2025 blueprint for neutering the “deep state.”

If anything unites them it’s admiration for Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. Deneen especially likes its policies to encourage larger families (designed to avoid the need for any immigrants whatsoever). Heritage Foundation president Kevin Roberts believes Orbán’s “defeat” of progressives and promotion of conservative Christian values “should be celebrated.” Vice-president J.D. Vance is a longstanding fan; conservative polemicist Rod Dreher seems happiest reading the latest edition of the Hungarian Conservative on the banks of the Danube.

So it’s no mystery that Princeton University’s Kim Lane Scheppele, a sociologist who once worked in Hungary’s constitutional court, has been in high demand in recent weeks. A partial list of her media engagements includes interviews by Associated Press, PBS News Hour, Slate, CNN, Democracy Now! and her “old friend,” the redoubtable Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, in his indispensable Substack newsletter.

Outside the world of right-wing punditry and activism, Orbán is probably best known for having announced that Hungary has transformed into an “illiberal democracy.” Illiberal it may be, but “democracy” is a stretch. In her analysis of the 2022 election, the fourth consecutive win for Orbán’s Fidesz party, Scheppele shows how Hungarian elections “hinge less on party platforms, campaigns, and attractive candidates than on election laws — laws that Orbán intentionally shapes to disadvantage the opposition.”

The Hungarian electoral system’s shortcomings go back to compromises struck when communist governments were teetering across Central and Eastern Europe in 1989. Hungary already had a multiparty system, but it was so heavily constrained that party leaders had to try to imagine what rules would give their party the best chance of success once elections were freer. Some favoured a system of “party lists,” others wanted single-member electorates. All of them wanted to exclude small parties.

The compromise, writes Scheppele, was a new election law that “lacked any mechanism to ensure that parliamentary-seat distribution would match the distribution of party votes.” The results of the first election under the new system, in 1990, made this vividly clear. “The largest vote-getter, the centre-right Hungarian Democratic Forum [later dissolved], won 25 per cent of the vote but received 43 per cent of the seats. The second-highest vote getter, the centre-left Free Democrats, won 21 per cent of the vote” — almost as much — “but only 24 per cent of the seats.”

Orbán took a bad system and made it worse. Having won government in 1998 and then lost it in 2002, he set about devising the means not just to regain government but also to hang onto it indefinitely. Although his main opponents at the time, the Socialists, managed to retain government in 2006, their mishandling of the global financial crisis gave Orbán the opening he needed. His Fidesz party returned to government in 2010 with more than 80 per cent of seats, a dangerous super-majority:

He could amend the constitution at will, which he did twelve times during his first year in office — including removing, early on, the four-fifths hurdle for rewriting the constitution. Less than a year into his first term, Orbán unveiled a new constitution drafted behind closed doors, debated before parliament for only nine days, and passed on a party-line vote. The new constitution was accompanied by hundreds of new laws, many affecting elections.

The new constitution left to the government the drawing of new electoral boundaries. Predictably, Fidesz drew the boundaries to suit its own interests, locking up opposition voters in larger electorates and maximising its own yield from its supporters. Writes Scheppele: “A study of the initial districts showed that if Fidesz and the left-opposition won equal numbers of votes under this new map, Fidesz would come out ten seats ahead.”

The list of electoral fiddling since then combines dubious practices — changes in the qualifications needed to vote, coercion at polling booths, new rules for allocating “excess” votes under the party-list system — with broadscale efforts to restrict public debate and undermine the rule of law. Media proprietors have been forced to sell their outlets to the government’s friends; judicial independence has been undermined; the Constitutional Court’s powers have been curbed. In the words of a European parliament resolution, Hungary has become a “hybrid regime of electoral autocracy.” …

As Scheppele told journalist Peter Geoghegan, “Orbán has been to US conservatives what Sweden once was to American social democrats. In a small country, far, far away, there is proof of concept that one’s political philosophy works.”

Of course, there are many reasons why Trump and Musk can’t simply take the Orbán path. In a country of fewer than ten million people it’s much easier to control the media, the judiciary and the population at large. Many much larger and quite powerful American states are outside the control of the Republican Party. The US opposition is much more united than the splintered anti-Fidesz forces have been in Hungary. The US Congress is a separate centre of power, and in a fair election the House of Representatives is likely to be back in Democratic hands in two years’ time. …

Project 2025 drew heavily on Orbán’s strategy, Scheppele added. “First you defund everything your opponents do. Then you purge the civil service of those who are not loyal to you. Then you threaten the media with economic sanctions so they fall in line. You pack the courts; you cow the parliament. All major actions of state are designed to cut off any form of accountability to anyone outside the tight inner circle. The point of all this is to shove public money into private pockets. Orbán is teaching all of those things and the Trump team are not dull pupils.”

Ironically, just as Orbán’s influence on the American right has become crystal clear, the popularity of his own party has plummeted. Politico’s poll of polls shows Fidesz’s support, 54 per cent at the last election, down to 37 per cent and the opposition Respect and Freedom Party — a more conventionally conservative newcomer also known as Tisza — rocketing to 41 per cent.

Fidesz’s current problems started with a paedophile scandal early last year that cost the country’s president and justice minister their jobs. “But the underlying discontents,” says Timothy Garton Ash, a distinguished historian of Central Europe, “are much deeper: all the accumulated dissatisfactions of fourteen years under one and the same government. Inflation last year was 18 per cent. People see the failings in public services and read about Orbán’s cronies getting fabulously rich.”

Hungary’s often-divided opposition is no doubt learning from its successive defeats (and so are voters). The country’s next election, due next year, will be the big test of Orbán’s quest to impose one-party rule.

“How do I make this book the perfect version of what it can be?”

I’ve always admired compelling fiction that’s not autobiographical — it seems to show a superior capability — but it’s also even further from anything I could ever do convincingly. If Rooney is to be believed — and I’m happy to believe he — she is something of a thoroughbred fiction writer — like I imagine Jane Austen. The connection between the writer’s life and the art is of no interest to her — whether the writer is herself or some other writer. Very intriguing.

I also loved her refusal to play the autobiographical writer — even if they did get her to pose from some silly photographs. A favourite passage from the interview.

There are stylistic aspects to “Intermezzo” that make it different from your past books. But it’s not that different. The way I think about it, any character from one of your novels could walk into another of those novels and the reader wouldn’t be like, What is that person doing here? Do you ever wonder if your books are too similar, and about how your writing might change in the future? That’s a really good question. I would have to answer it by saying I don’t care about my career. I think about, How do I make this book the perfect version of what it can be? I never think about it in relation to my other work, and I never think about what people will say about how close or distant it is from my oeuvre. I don’t think of myself as even having an oeuvre. I just think about: I’ve got these characters. I’ve got these scenarios. How do I do justice to them? I don’t feel myself thinking about my growth as an artist, if you will.

You’re not being a little disingenuous? I’m skeptical. It’s fair to be skeptical. There is a huge cultural fixation with novelty and growth. Everything has to grow all the time. Get bigger, sell more and be different — novelty, reinvention. I don’t find that very interesting. When you say one of my characters could walk into another of my novels, perhaps that is true, but they haven’t. There is no Ivan in any of my previous books. He is a new guy, and for me that’s enough. I do understand that people might feel, Oh, she’s repeating herself because it’s another book about people — same age range, same milieu, some of them are in Dublin, some are in the west of Ireland — and they’re traveling back and forth, and they’re having these relationships, and there’s sex and there’s talking, and they have political beliefs or whatever. Yeah, that is all my books, and perhaps it always will be. I don’t know. I’m wary of saying this, because it could sound like I’m trying to compare myself to the great masters of the past and I absolutely am not, but when I look at writers whose work has transformed my life, I look at Austen, Henry James, Dostoyevsky. Those writers produced work that adheres to what you’re describing, where it feels like a figure from one of their books could stroll into any of the other novels that they wrote and be at home. But each of the novels is its own world, and it’s intense and it’s profound and it’s beautiful, and that’s what I’m striving for.

Autism and modernity

From correspondence on last week’s newsletter which argued that the move from Hayek’s idea of liberalism to Trumpery was a move from one regime that was destructive of the order on which it relied for its functionality.

From Julie Thomas

Hayek was autistic. So obvious don't you think Nicholas? Or is it still bad form to diagnose dead people? And am I diagnosing or just recognising the signs of this obsessive way of thinking that I've seen in the living autistics I know?

From me:

Thanks Julie, come to think of it, autism could be a reasonable explanation for Hayek. As John Gray observed the ”liberal economy emerges morally naked in Hayek's account of it”. Unlike Adam Smith and Schumpeter for instance, he was uninterested in the extent to which the market might itself help replenish the stock of social capital it relied upon to function.

But when you think about it, virtually every major architect of the philosophy of modernity was off-the-charts autistic. Machiavelli, Descartes and Hobbes come to mind. In fact the only one I'm familiar with seems less autistic is Adam Smith. I often think of Western modernity as a kind of Faustian bargain. We got an incredible new world view and set of institutions, but those instincts and institutions that knit us together, that provide care, whether in our households or workplaces? Well they couldn't compete now could they? And here we are.

The private jet

Tina Brown on crossing the threshold.

I have sometimes pondered the pivotal moment when money changes people forever. The answer is without doubt the acquisition of the private plane—it’s the moment when you leave the human race forever. And having just flown back on JetBlue Mosaic from the Dominican Republic sitting next to an enormous Russian chomping plantain chips, I attest wholeheartedly that it’s a loss of connection not to be regretted.

So it is no surprise to me that Bill Clinton, in his new memoir Citizen, ascribes his dependence on Jeffrey Epstein’s private plane to the travel needs of the Clinton foundation. Who else is going to put his Boeing 727 at the service of an ex-president to fly around to what our soon-to-be 47th president once called “shithole countries” than a fraudulent pedophile like Epstein in desperate need of adding sheen to his slime? In 2002 Epstein picked up Clinton in Siberia on the “Lolita Express” and flew him to a US naval base in Japan, which hardly sounds like the thrumming locus of nubile orgies.

The late TV legend Barbara Walters used to lament the necessity to vacation every year with the crass termagant CEO of a bra company just because said termagant happened to own her own plane. Most of Henry Kissinger’s inner circle was dictated by who could fly him where and when. Knowing this, the host of any speaking invitation had to sleuth out some ponderous plutocrat to fly him from New York to Stuttgart to keynote at a conference, only to be told by Henry that his flying host, too, required a “role” on the agenda.

The question of who an ex-president is going to scare up to transport him (or her…hah, as if) round the world in the manner he’s been accustomed to is a knotty dilemma that confronts every departing POTUS, or CEO of any mighty corporation. A leading M&A lawyer once told me that corporate merger negotiations often run aground on a vague-sounding contractual term known as “the social issues.” The social issues are, primarily, the private plane. Can the exiting big shot still have use of it? How often? With how many co-passengers? No plane, no deal.

Historians searching for the real reason the Bidens clung to power too long may look no further than the looming loss of Air Force One. After flying private a few times with gilded friends, I am convinced it’s the single most seductive experience in the world. You realize there is no one you wouldn’t kill, betray, or sleep with to ensure a lifetime of luxe relief from the armpit of mass transit.

The Perils of Flying Private

The Obamas won’t even cross the road these days—or in Barack’s case, play a round of golf at a prestigious club—without the use of a private plane belonging to one of their billionaire circle. It is worth examining who did and did not make the cut at his notorious Martha’s Vineyard 60th birthday party in 2021 based on whether or not the guest in question could provide future access to wings. Obama’s lofty insertion into the 2024 campaign in Pittsburgh — scolding Black men for not showing enough enthusiasm for Harris because, “well, you just aren't feeling the idea of having a woman as president, and you're coming up with other alternatives and other reasons for that”- can be attributed — I submit, to too much time spent gazing down at the world from the window of a Gulfstream. I will never forget catching sight of former Vice President Al Gore, a month after his loss in the 2000 election, trundling his own wheelie bag towards the passenger welcome area at Newark airport.

Unfortunately for those in public life, the allure of—no, the addiction to—flying private is full of hazard, a true satanic temptation from the mountaintop. As Bill Clinton says in Citizen: “The bottom line is, even though it allowed me to visit the work of my foundation, traveling on Epstein’s plane was not worth the years of questioning afterward.” You bet. Name me the pure-hearted billionaire who wants nothing in return. There is no greater hazard than the offer of a Gulfstream to foster dubious associations with influence-seeking Saudi potentates, borderline Kazakh shysters, odious oligarchs, and the rest of the cast of incorrigibles—and land you on the cover of the New York Post.

A right-wing takedown of Biden and Blinken on foreign policy. Overly snide if you don’t agree, but I was glad I read it.

The past, the present and the future: a writer reassesses: a fine piece

In the spring of last year, I broke seven ribs in one go. …

I was like one of those new housing developments in New York that look just fine from the outside but are semi-uninhabitable due to shoddy construction. … For the several weeks after my injury, though, I found myself very much stuck in the present. In part I was tethered there by the new limitations of my body. The simplest of actions, which I’d generally had the fortune to take for granted, suddenly ranged from arduous to impossible—lying down or sitting up, turning around, laughing or coughing or, god forbid, sneezing.

I’d always figured that my preference for the past and the future is one of the reasons I’m drawn to writing fiction. Stories are driven by what characters want, which always enlists both the past and the future. A character’s past experiences shape who they are in the present time of the story, including what their desires are; and, barring Time’s Arrow-type conceits, those desires relate to how things will be in the future.

We can see this most clearly in novels like Persuasion or The Great Gatsby, where the reintroduction of the past into the present—Captain Wentworth showing up in Anne Elliot’s life seven years after she broke off their engagement; Jay Gatsby reviving an acquaintance with Daisy Buchanan five years after he was posted overseas in WWI and she went on to marry another man—propels the plot forward. Some novels tilt even more toward the past, with their narratives largely comprised of, or deriving their power from, events that occurred prior to the present time—think any number of elegaic English novels, from Brideshead Revisited (the title says it all) to The Go-Between to The Remains of the Day. Other novels choose to start from the beginning of the story which is being told, planting their stakes firmly in the future.

As a writer, the present felt to me like the shallowest of the three temporal eras. The past provides context for and significance to the characters’ present-day actions; and the potential consequences of those actions, i.e., the future, create relevance and urgency. In contrast, the present seemed to be mainly concerned with execution, moving the characters from point A to B to C.

I’d previously viewed this set-up in fiction as using the present simply as the “excuse” for the narrator to recall past events. But it also enables the author to refract the telling of those events through the medium of time, providing an interpretation that is mediated by both knowledge (the narrator knows what happens after the events they are recounting) and change (the narrator now is a different person from who they were then). This results in a richer, more nuanced story—at the expense, I’d argue, of a certain degree of surprise and momentum.

This backward-looking structure does afford another kind of surprise, in stories that utilize the present for revelation as well as refraction: the narrator, examining the past in the light of the present, discovers something new about what they experienced. This can happen because the present-day narrator obtains information that transforms their understanding of the past—in The End of the Affair, for instance, Bendrix learns the real reason for, well, the end of his affair. Or it can be a subtler, internal sort of discovery, the narrator realizing as they are telling their story what they have missed until now, as with Stevens in The Remains of the Day, a contender for most emotionally repressed character ever.

As with Breakfast at Tiffany’s, in rereading The Remains of the Day I was able to appreciate an important aspect of that novel’s treatment of time. The present-day storyline is about Stevens driving across England to visit his ex-colleague Mrs. Benn (nee Kenton), the former housekeeper of the residence where Stevens still works as butler. The narrative builds toward their meeting, which takes on greater significance as we learn, through Stevens’s memories, about their relationship—and then skips right over it! The reader only finds out what happened two days later, when Stevens reflects on his conversation with Mrs. Benn, allowing himself, finally, to admit his regret at what might have been. Thus, even the most critical present-day event in the book is related as coming from the past; that’s the only way Stevens is able to share it with us, after he has safely sealed it away in time, something to be recollected and not experienced. Here the absence of the present speaks to its power. A narrator can control the past and project the future, but the present must be lived in.

It’s a reminder that applies not only in fiction but also in life As my ribs healed up, I found myself recurringly surprised and grateful for each movement that caused less pain than I had remembered, and then no pain at all. The day I managed a full-on sneeze was a celebratory one. I’ve tried to hold on to this new appreciation of all the things I previously never even noticed—at least, until the next injury.

Inappropriate Technology: Evidence from Global Agriculture

An influential explanation for global productivity differences is that frontier technologies are adapted to the high-income countries that develop them and "inappropriate" elsewhere. We study this hypothesis in agriculture using data on novel plant varieties, patents, output, and the global range of crop pests and pathogens. Innovation focuses on the environmental conditions of technology leaders, and ecological mismatch with these markets reduces technology transfer and production. Combined with a model, our estimates imply that inappropriate technology explains 15-20% of cross-country agricultural productivity differences and re-shapes the potential consequences of innovation policy, the rise of new technology leaders, and environmental change.

Getting DOGE'd

Some of the worthiest looking road-kill from the free-fall. From The Polymerist Substack

On February 15, 2025 at about 6:30 PM I got an email I had been dreading. An acting director in the Department of Health and Human Services had told me that my probationary period was over because of performance reasons. This is a lie. I have three performance evaluations that demonstrated my proficiency and excellence as a reviewer at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). I’ve received multiple awards at the FDA including the Honors Award. I’ve even given a keynote talk at the Diabetes Technology Conference in October 2024. I have submitted my appeal about this being a wrongful termination and I’ve been in touch with my NTEU chapter. …

Being a Medical Device Reviewer for FDA.

In the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) there are just a handful of reviewers and maybe a medical officer or two that hold the line of safety and effectiveness for the American public in very specific disease focused areas. I was part of the diabetes branch, a disease that affects about 11.6% of the United States population or roughly 38.4 million people. The diabetes branch in CDRH deals with both the measurement of glucose and hemoglobin A1c as well as insulin delivery systems such as automated insulin delivery algorithms (artificial pancreas), insulin pumps, and continuous glucose monitors. Any clinical trials associated with these devices would also come to us for review.

The diabetes branch works to ensure that if you are going to be diagnosed with diabetes that the diagnostic instruments are accurate and precise, the devices being used to manage your disease are accurate and precise, and any form of insulin delivery should be safe and effective (you don’t want an unintentional overdose or underdose of insulin… this is how you or your child might die). The patient population spans from 2-year-olds who get a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes all the way to an older adult who may develop type 2 diabetes. This work spans the pre-market authorization side in that we try to ensure any new device is safe and effective, but it also spans the post-market side.

CDRH reviewers work to authorize new devices and also work on monitoring safety issues associated with currently authorized devices or potentially unauthorized devices. The FDA calls this “total product lifecycle” or TPLC and it includes compliance. On the prescription drug side there are usually distinct teams that exclusively work on these issues. In CDRH we are just lucky to get to work on both.

If you are a patient and you complain about the inaccuracy of your device or that it’s not working as expected and you file a complaint to the FDA then ultimately, it’s going to be a reviewer handling your complaint. If a company reports incidents that result in patient death or serious harm (e.g., going to the hospital) known as medical device reports or MDRs then these are monitored by the FDA reviewers too. You can also look them up through FDA’s MAUDE database. For some devices we can look at every single MDR since they might be few and far between. For other high-volume devices there can be millions of MDRs submitted every year. All of this data is public.

Inspections of manufacturing facilities can also come to CDRH reviewers for concurrence or requesting consults on specific actions the agency might take such as a warning letter, untitled letter, or a regulatory meeting. These establishment of inspection reports or EIRs are how the product evaluation experts within CDRH support the Office of Inspections and Investigations.

Any recalls that are initiated by manufacturers will get classified by the CDRH reviewers. The reviewers may even initiate the recall or issue a public safety notice due to the agency’s concerns for public safety. CDRH reviewers will recommend either class I (the most severe), class II, or class III (the least severe) for a recall. Any unauthorized devices that are on the market are something we also look for and try to notify the public is aware that they could be really dangerous. …

PS this scene [The YouTube video above] keeps playing in my head now. I originally experienced it as a kid. I’m now experiencing it as a father. Life goes on.

A gift from the YouTube algorithm

Raymond Aron contra Hayek

Readers will have noted my enthusiasm for Aron on previous occasions. This is a fine article of appreciation with the following passage explaining what he objected to about Hayek — roughly what I object to about him:

Aron’s [anxieties] were energizing, not debilitating, constructive and enormously productive: productive in light, in sober guidance, in providing a model of equanimity in the midst of storms. So Manent talks about the other part of his title, “Politics as Science,” that is, politics as something to know and the knowledge required to know it. Here we encounter a surprising contribution to current debates over liberalism. For Aron was often, and rightly, said to be a “liberal.” But his liberalism escapes our categories, and his liberalism illustrates what liberalism can be, arguably should be, to defend its deepest values: human equality and liberty, science and truth, justice and peace. Aron taught (less by words than by example) that it must be political.

To make this capital point, Manent employs a technique that Charles Péguy called “the method of eminent cases.” He highlights Aron’s critical engagement with Friedrich Hayek and his chef d’oeuvre, The Constitution of Liberty. Prior to his critique, Aron acknowledges his fundamental agreement with Hayek. “It so happens that, personally, I share [Hayek’s] ideal”—namely, that government should afford citizens the widest range of liberty and that when it impinges on liberty it should do so by means of law— “The reservations which I shall formulate do not, therefore, have their origin in a different hierarchy of values, but in the consideration of several facts.”

The first fact to consider is a massively obvious one: that particular political communities, liberal ones included, live in a world composed of a variety of political forms and regimes, most of them not liberal. Hayek, however, all but ignores foreign policy (while Aron devoted “a good third” of his corpus to it); Hayek’s “ideal” of replacing the rule of men with the impersonal rule of law cannot serve as a guide in this important, sometimes decisive area of common life. Here one needs the quintessential political virtue of prudence and elites and populaces capable of working together. A clear-eyed defender of human liberty must take into account these political conditions and constraints.

This leads to a second lacuna on Hayek’s part. He takes for granted what previous political thinkers saw as one of the “prime tasks” of politics: forming men to live together in society. Political order—liberal order especially, which is especially demanding—does not appear spontaneously. Human beings must work at it constantly. In particular, along with the widest berth given to individual belief and choice, in liberal polities there must be a social consensus that grounds and frames the public’s living-together. This can be inherited from the past, but it must be constantly monitored and supported, repaired, and updated as needed. Politicians and political scientists must make this a central concern.

Finally, liberal order requires its own sort of civic “virtue,” a virtue that sometimes makes contradictory demands on its members, depending on time, circumstance, and issue. In times of serious foreign danger, with elites this virtue must take on something of Machiavelli’s virtù without succumbing to the Machiavellian temptation to utter immorality. Liberal populaces must understand the rulers’ need for cunning and must have a capacity for hardness that ordinary liberal life tends to undermine. This difficult sort of eutrapelia, or adjusting to dramatically different circumstances and exigencies, also requires attention and cultivation.

Thus, from the beginning to the end of his career, Aron asked himself, are we—citizens and elites—formed by and capable of the demands of the society we have inherited or chosen, one quite different from those that surround us and with which we must engage? He reminded the liberal individual that he was so because he was a free citizen, a member of a liberal, self-governing political order. He should judge and act in accordance with that fuller truth. When France and the West took an antinomian path in the 1960s, Aron was there to remind them that liberty was not license and that liberty in society requires authority. All these lessons (and more) are developed in Liberty and Equality.

In pondering these parting words, the reader, I submit, will be struck by four things: 1) the use Aron makes of the authority the wise man possesses to restate the obvious; in this, common sense finds itself confirmed, which is important in a hyperpartisan and ideological age; 2) his ability to enlarge the discussion, in part because of wide learning, in part because of his independence of mind; 3) his prescience—this no doubt because of how deeply he penetrated into the nature of liberal society and, one must add, into its enemies, natural and ideological; and, finally, 4) the larger horizons he opens: to be more precise, his openness and opening to philosophy. While reading Liberty and Equality, one will experience the sure guidance of a true educator, perhaps the rarest sort of educator: a political educator.

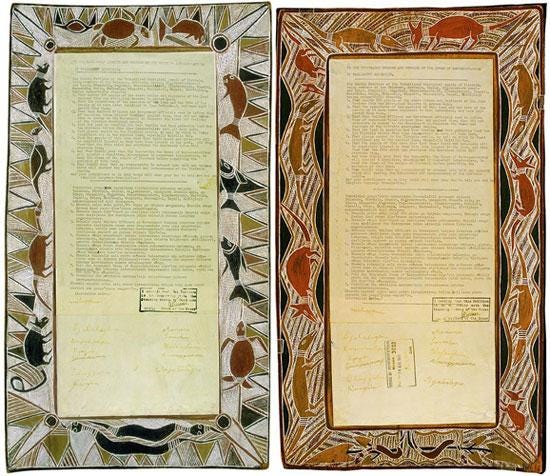

The bark petitions

Listen to this wonderful interview with the author of a new book on the 1963 bark petitions. A great listen.

Martin Wolf on the US, Russia, Europe and Ukraine

Arguably, for Trump, “dictator” may be a term of commendation, not condemnation. Again, for him, owning a valuable asset in another country might be the only reason to protect it. Even so, demanding a vast sum from a poor country that has been the victim of an unprovoked aggression is outrageous, particularly when Ukraine must rebuild. It is worse that the value of US demands was some four times its assistance. Moreover, according to the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker, Europeans provided more assistance than the US, which made just 31 per cent of total bilateral commitments and 41 per cent of military commitments to Ukraine between January 2022 and December 2024. Yet where are they in these negotiations? Nowhere. Trump is deciding for Ukraine and Europe, on his own. (See charts.)

In all, the US has spent just 0.19 per cent of GDP on military assistance for Ukraine. This is trivial, particularly in comparison with the cost of its previous wars. In return, it has gained the humiliation of what was once thought to be a powerful enemy and the vindication of the ideals of liberal democracy, for which Ukrainians are fighting and the US once fought.

These past two weeks then have made two things clear. The first is that the US has decided to abandon the role in the world it assumed during the second world war. With Trump back in the White House, it has decided instead to become just another great power, indifferent to anything but its short-term interests, especially its material interests. This leaves the causes it upheld in limbo, including the rights of small countries and democracy itself. This also fits with what is happening inside the US, where the state created by the New Deal and the law-governed society created by the constitution are both in danger of destruction.

In response, Europe will either rise to the occasion or disintegrate. Europeans will need to create far stronger co-operation embedded in a robust framework of liberal and democratic norms. If they do not, they will be picked to pieces by the world’s great powers. They must start by saving Ukraine from Putin’s malevolence.

From a reader on Michael Longley

In responding to this piece on the Irish poet Michael Longley

What really hits home is Michael Longley saying "Because when you're proficient stylistically, it's terribly easy to produce forgeries. And what the inner adventure of poetry has taught me about is courage and patience and honesty.”

I assume that every generation has had to discover this same thing for itself. Of course it applies both to writing and every other creative act we are capable of performing e.g. painting, writing philosophy, warfare, governance. Just when the line is crossed is hard to say - it could be in the choice of a word or mid sentence or halfway through a book. It correlates with experience, but also with laziness.

Since you referred to it in your bulletin this week, ‘pearl clutching’ is a species of forgery. Or is it, for isn’t it the case that we often need unpleasant information repeated many times before it flags us down? Obviously a diet of unpleasant information merely produces nausea - so much for vitality. But in some things and for some time a daily dose may be required - think of it as something you do with your calcium supplements or anti-depression agents.

AI in government … sigh

From Tim Murray on LinkedIn:

𝗧𝗟𝗗𝗥: 𝗚𝗼𝘃 𝗮𝘀𝘀𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗱 𝗮 𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘁 𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗼𝗳 𝗖𝗼𝗽𝗶𝗹𝗼𝘁, 𝗳𝗼𝘂𝗻𝗱 𝗶𝘁 𝘄𝗮𝗻𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴. 𝗜 𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗻𝗸 𝗶𝗻𝗱𝗶𝘃𝗶𝗱𝘂𝗮𝗹𝘀 𝘄𝗮𝗻𝘁 𝘁𝗼 𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗟𝗟𝗠𝘀 𝗯𝘂𝘁 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝘀𝘆𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗺/𝘃𝗼𝗰𝗮𝗹 𝗺𝗶𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗺𝗮𝗸𝗲 𝗶𝘁 𝗵𝗮𝗿𝗱. 𝗜 𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗻𝗸 𝗔𝗣𝗦 𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗳𝗳 𝗻𝗲𝗲𝗱 𝘁𝗼 𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘁 𝗻𝗲𝘄 𝘁𝗼𝗼𝗹𝘀 ([𝗰𝗼𝘂𝗴𝗵] 𝗼𝘂𝘁𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲 𝗼𝗳 𝘄𝗼𝗿𝗸). 𝗜𝘁’𝘀 𝗵𝗮𝗿𝗱 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗴𝗼𝘃 𝘁𝗼 𝗵𝗮𝘃𝗲 𝗔𝗡𝗬 𝗰𝗿𝗲𝗱𝗶𝗯𝗶𝗹𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗼𝗻 𝗔𝗜 𝗹𝗶𝗺𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗶𝗿 𝗼𝘄𝗻 𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗳𝗳

The APS (the Australian Centre for Eval, assessing TSY) released a report on a Copilot trial. As a former APS employees who actively uses many new technologies, I can now be "frank and fearless". I found the report depressing (for Australia and the quality of APS work). I worry the reporting (and summary) doesn’t reflect the “silver linings”, feeding opponents

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗻𝗼𝘁-𝘀𝗼-𝗴𝗼𝗼𝗱

-𝗟𝗼𝘄 𝘂𝘀𝗮𝗴𝗲 𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗲𝘀: Despite a smooth rollout LLMs were barely used

-𝗕𝗶𝗮𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗽𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗶𝗽𝗮𝗻𝘁𝘀: The report said participants were opt-in and likely had positive priors about AI. But realistically, the APS has broader biases (in selection of employees, and conditioning/training), so I doubt we can generalise that

-𝗟𝗶𝗺𝗶𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗰𝗮𝘀𝗲𝘀: Copilot was useful for basic tasks. I worry the APS's aversion to risk, slowness and lack of curiosity/innovation played a role. I worry uses were too concentrated in "New Google!" or "Robo staff member!" to explore the potential appropriately

-𝗜𝗱𝗲𝗼𝗹𝗼𝗴𝗶𝗰𝗮𝗹/𝗹𝗲𝗴𝗮𝗹 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝗰𝗲𝗿𝗻𝘀: Elephant in the room: the unresolved legal and ethical issues (and what APS staff might be worried about or have agendas against). I know a lot of APS folks are worried about IP/other implications, aren’t coming in neutral

𝗦𝗶𝗹𝘃𝗲𝗿 𝗹𝗶𝗻𝗶𝗻𝗴𝘀

-𝗜𝗻𝗰𝗿𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲𝗱 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝗳𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗷𝘂𝗻𝗶𝗼𝗿 𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗳𝗳: That's great, but it makes me wonder if they're less jaded, biased and change averse, more willing to try new ways of working

-𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝘁𝗼 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲: The report talks about the need for more training. No surprise there: "more training" is the APS answer to everything, even when the issue intersects with individual/cultural resistance to change/fear of novelty

-𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗮𝗹𝗹 𝗔𝗜 𝗶𝘀 𝗰𝗿𝗲𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗲𝗾𝘂𝗮𝗹: The report low-key mentioned that many critiques were Copilot specific. Participants compared it unfavourably to others, suggesting different products. Sadly, this didn’t make the summary (or reporting, that I saw)

I worry the report (and trial) is an excuse to be very slow with change. That’s a recipe for mediocrity, falling further behind. I also think the APS has little to no credibility on regulation if they don’t allow experimentation internally (other than in the slowest of ways). The APS had a chance to really explore AI, but instead got stuck in old ways of thinking. Maybe it's time for a more "frank and fearless" approach to innovation. The report can be accessed here.

Mary Harrington

One of the more lucid elaborations of Mary Harrington’s view of the world.

Speaking of Government: some ideas for the campaign trail

Edward III liked to dress up as a bird. In 1348, at a tournament in Bury St Edmunds, he revealed himself as a gleaming pheasant with copper-pipe wings and real feathers. The next year, celebrating Christmas with the archbishop of Canterbury, he wore a white buckram harness spangled with three hundred leaves of silver, adorned with one of his mottoes: ‘Hay hay the wythe swan/by godes soule I am thy man.’ Troupes of wodewose (green men) were arranged around him in a pageant, complete with virgins, elephants and bats – a spectacle of sovereign marvels. Another of Edward’s mottoes was ‘it is as it is.’ He loved to play pretend.

Great fun

ESG Is The Most Polarizing Nonwage Amenity: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Brazil

We examine job-seekers' heterogeneous preferences for nonwage amenities, with a focus on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices, using an incentivized field experiment in Brazil. Our findings reveal that ESG is the most polarizing nonwage amenity across multiple sociodemographic groups, with the strongest preferences observed among highly educated, white, and politically liberal individuals (Colonnelli et al., 2025). While women report a stronger preference for work-from-home policies, all other non-wage amenities exhibit minimal variation across sociodemographic groups. Our findings highlight the critical role of corporate values in shaping economic outcomes within an increasingly polarized society.

Heaviosity half-hour

The Foucault moment. Do-gooding goes counterfeit.

Vice always comes disguised as virtue. No exceptions

I love that quote from Ryan Meade, a Thomist legal scholar. Trouble is, the disguises are getting better and better. I think of the story told here as a watershed moment (I wonder why watershed moments are called watershed moments — rather than ‘rotary sprinkler’ moments for instance — but I digress). My point is that it was pretty clear what was going on in the state sanctioned apartheid run in the Southern states of the US before civil rights. You didn’t have to have a very sophisticated theory to work out that it was wrong, and that civil rights were right.

Now things are complicated and tangled up in symbolic structures. It’s much easier to hide in there. From our vantage point, redlining and other unsavoury practices in the US’s north were pretty bad too, but they were concealed in the innards of systems. Today things are more hidden still. And the DEI measures we take are commensurately more indirect. Does it promote diversity, equity and inclusion to advantage a kid at an elite school who has one great grandparent who was indigenous. It could, but it doesn’t look like a priority. Still if you’re running things and making these distinctions, well it could get a bit awkward. So self-identification of the beneficiary seems so much safer for the decision makers involved.

From Sanjida on Goodreads.

This is a wicked, as in cruel, book about elite hypocrisy. This is a roast. If you are the type of person who reads reviews on Goodreads, chances are, he's roasting you. I kind of loved it, even when I thought he was overgeneralizing and not playing fair. (I mean, not fair to me, because I'm not like that, even though I totally am, lol).

Anyway, over to Musa Al-Gharbi:

Coda: White Liberals

In a prescient series of essays for Radical America in 1977, Barbara and John Ehrenreich defined the professional-managerial class (the term they coined for symbolic capitalists) as "salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations." In layman's terms, the major role they play in society is to keep the capitalist machine running (in the present and in perpetuity), maximize its efficiency and productivity, and justify the inequalities that were required in order to achieve these ends.

This posed a bit of a problem for symbolic capitalists, who, as the Ehrenreichs noted, were generally aligned with the New Left. They sympathized with radical feminism, the Black Power movement, environmental activism, the weakening of sexual taboos, socialism, the antiwar movement, and so on. However, they also had bills to pay and, as time went on, families to support—and there were lots of lucrative new opportunities for those who were willing and able to partake in the globalized knowledge economy.

Toward the end of the second Awokening, the primary way most resolved this tension without nakedly “selling out” was to insist that they would use their new influence within “the machine” to help the disadvantaged. That is, they would be subversive “cogs,” who would engage in a “long march through the institutions” and leverage them toward alternative ends. They would learn to uplift those who were suffering and empower those who were marginalized through the very systems and institutions that would have otherwise exploited and oppressed them. Notice, however, that in defining their own flourishing within the “system” as a means of increasing their capacity to help the desperate and vulnerable, symbolic capitalists provided themselves with a powerful justification for climbing as high up the ladder as they could and accumulating more and more into their own hands: the more resources they controlled, and the more institutional clout they wielded, the more they would be theoretically able to accomplish on behalf of the needy and vulnerable (and the less capital would be in the hands of the “bad” elites). “Doing well” was redefined as a means of “doing good.”

From the outside, it often seemed as though symbolic capitalists were relentlessly engaged in a rat race to enhance their own social position. However, the Ehrenreichs noted, they typically did not think of themselves as being oriented toward such banal ends. Granted, the promised reallocation of the assets and opportunities amassed—ostensibly on behalf of the downtrodden—would likely never come (and indeed, some four decades after the Ehrenreichs published their essays, we’re still holding our breath on that). However, symbolic capitalists could nonetheless generate a sense of “progress” toward their egalitarian commitments by pushing their institutions to take symbolic actions with respect to empowering women and minorities, validating LGBTQ people, protecting the environment, and so forth.

The second key strategy adopted by the symbolic capitalists to reconcile their “day jobs” with their political beliefs was to try to live in accordance with their New Left values personally (that is, to find ways to signal their own individual commitment to feminism, antiracism, environmentalism—including through “just” consumption), and to encourage their peers to do the same. In the process, they turned the campaign for social justice “inward”—into a psychological and even spiritual project. The status quo may persist, largely as a result of their own work no less. However, symbolic capitalists could still think of themselves as virtuous in light of how they carried themselves in the private sphere and by conspicuously demonstrating the purity of their own hearts and minds.

Over the course of their essays, the Ehrenreichs powerfully explain some of the “pull” factors that led symbolic capitalists of the 1970s to disengage from social justice activism. However, there were also “push” factors that led them away from direct action during the second Awokening. Exploring those is perhaps an ideal way to both close out this chapter and transition to the themes of the next.

In the news media of the 1960s (as remains the case today in some respects), racism was depicted as primarily a problem of “backwards” rural and southern areas. However, as civil rights leaders began to see major breakthroughs in the South, they decided that their work was not yet done. At the invitation of the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, a Chicago-based civil rights body, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) launched a campaign against the de facto segregation in northern schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces in 1966. They began by trying to move Black families into predominantly white neighborhoods in Chicago. Rather than being welcomed with open arms by enlightened urban northerners, they were violently resisted at every turn.

Here, it is worth quoting King at length:

Bottles and bricks were thrown at us; we were often beaten. Some of the people who had been brutalized in Selma and who were present at the Capitol ceremonies in Montgomery led marchers in the suburbs of Chicago amid a rain of rocks and bottles, among burning automobiles, to the thunder of jeering thousands, many of them waving Nazi flags. Swastikas bloomed in Chicago parks like misbegotten weeds. Our marchers were met by a hailstorm of bricks, bottles, and firecrackers. “White power” became the racist catcall, punctuated by the vilest of obscenities. . . . I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I had never seen, even in Mississippi, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as in Chicago.

As King explained in his 1967 address to the American Psychological Association, this vicious reception among the people who were supposed to be “allies”—among those who had been cheering the civil rights movement elsewhere—this stalling-out of progress in the section of the country that was supposed to be easier than the South led to deep rage in the Black community. The SCLC’s message of nonviolence, forbearance, faith in humanity, and interracial cooperation increasingly rang hollow. Riots broke out. Increased repression followed. Black militias gained prominence, encouraging African Americans to defend themselves against white aggression. Black nationalist movements grew.

As scenes of unrest played out in northern streets (rather than comfortably far away in the South), media coverage of King and civil rights demonstrations grew overwhelmingly hostile. Despite previously holding King up as a national hero, the Johnson administration cut off contact and access altogether when King began to criticize the Vietnam War. In 1967, with President Johnson’s blessing, the FBI launched a new campaign, COINTELPRO–BLACK HATE, seeking to “disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities” of King, the SCLC, and many other civil rights organizations and activists. Public opinion quickly soured as well: at the time he was assassinated, King had a 75 percent disapproval rating according to polls.

Seeing the establishment turn so rapidly on a person who had bent over backward to accommodate them—who had consistently extended the benefit of the doubt to whites and encouraged others to do the same—the sense grew in Black organizing spaces that white liberals could not be trusted. They may even be worse than right-wing opponents, many argued. Reactionary conservatives, for instance, would directly tell you how they felt and what they were after. You could plan around that; you could work with that (even if what they had to say was often horrifying or offensive). It was much harder to deal with people who pretended to be on board but were unwilling to make meaningful sacrifices and constantly deflected blame for social problems onto others. It was much more difficult to work with people who wouldn’t resist the movement per se, but instead tried to hijack it to suit their own interests. It was far tougher to tolerate someone who would not only lie to others but who couldn’t seem to be honest with themselves about what they were trying to accomplish and what their ideal endgame was. As Ebony magazine editor Lerone Bennett Jr. explained at the time:

White friends of the American Negro claim, with some justification, that Negros attack them with more heat than they attack declared enemies. . . . Oppressed people learn early that the problem of life is not the problem of evil but the problem of good. For this reason, they focus their fire on the bona fides of avowed friends. . . . The white liberal is a man who finds himself defined as a white man, as an oppressor in short, and retreats in horror at that designation. But—and this is essential—he retreats only halfway, disavowing the title without giving up the privileges, tearing out, as it were, the table of contents and keeping the book. The fundamental trait of the white liberal is his desire to differentiate himself psychologically from white Americans on the issue of race. He wants to think, and he wants others to think, he is a man of brotherhood. . . . What characterizes the white liberal, above all, is his inability to live the words he mouths . . . he joins groups and assumes postures that permit him and others to believe something is being done. The key word here is believe.

King grew increasingly disillusioned as well, arguing toward the end of his life that “Negros have proceeded from a premise that equality means what it says, and they have taken white America at their word when they talked of it as an objective. But most whites in America in 1967, including many persons of goodwill, proceed from a premise that equality is a loose expression for improvement. White America is not even psychologically organized to close the gap—essentially, it seeks only to make it less painful and less obvious but in most respects to retain it. Most abrasions between Negros and white liberals arise from this fact.”