Wellbeing: escaping the iron law of business-as-usual

I really enjoyed this week’s uncomfortable collision with reality with colleague Gene Tunny. We covered a lot of ground talking about the use and abuse of the wellbeing agenda.

Where does it come from? Why is it taking off as an approach to policy making?

How do we make the most of this as authorisation to improve our world?

By avoiding the pitfalls!

I argue that the main pitfall is imagining ourselves to be part of some grand new way of thinking. Bureaucrats and think tanks reach for frameworks and schematic diagrams. But if they’re the wrong kinds — if they’re schematic rather than built to aid action — those frameworks simply give us new labels with which to dress up the same old same old and the iron law of business-as-usual takes hold again. Until the next new fad, the next new vocabulary.

But done well, we could really address some big problems at the same time as improving the health and prosperity of our communities.

Famous last shot?

Australia Post and micro-economic reform in the bush

A couple of months ago Christine Holgate rang me asking if Lateral Economics would do an economic analysis of giving companies like the one she heads — Team Global Express — access to the ‘last mile’ of Australia Post’s network for parcel delivery. I told her I’d proposed the very policy she was proposing all those years ago when Australia led the world in imposing the National Competition Policy. Only I’d generalised the case into a principle which I called ‘extended access’. Micro-economic reform is often taken to have undermined cross-subsidies to the bush. However at least in post as the letter delivery monopoly fails to keep pace with economic growth, so too does the honeypot from which any cross-subsidy to be bush can be funded. As Australia Post defends its market position, it does so by holding the bush to ransom, ensuring higher prices and less responsive service.

From the paper I wrote back in the 1990s:

Before access is compelled in the NCP these tests must be met:

that the asset is of national significance,

that providing access will increase competition and

that access will not be contrary to the public interest.

In fact we would like to see less monopolistic and restrictive behaviour than we do even where these tests cannot be passed. But the judgement is made that we impose access only where we are confident its benefits (in reducing monopoly) outweigh its costs (attenuating freedom of contract and increasing business uncertainty).

But why should we be so reticent in requiring fully government owned business (GBEs) to eschew monopolistic or restrictive behaviour? … Put another way, wherever a GBE faces a conflict between commercial objectives (its own self-interest) and being competitive (including providing competitors and potential competitors with access to its facilities [which are more consistent with the public interest]) competitive rather than commercial objectives should dominate. … Where we see it as legitimate for a privately owned enterprise to resist access if it considers this would be inimical to its owner’s interests, we should regard such reasoning as inherently suspect in the case of GBEs.

… I will call this ‘extended access’ to distinguish it from the existing access arrangements which apply by virtue of the National Competition Policy.

Thus The Australian reported:

Rural and regional Australians could save hundreds of millions of dollars if the Albanese government allowed third-party delivery companies, such as FedEx, DHS and Team Global Express, to access Australia Post offices and drivers, a new report has found.

Under current regulations, third party delivery services are unable to use Australia Post’s so-called last mile delivery infrastructure, which includes everything from its distribution centres where posties pick up parcels, to licensed post offices and the vans and bikes parcels are delivered in.

While customers in cities can have their parcels dropped at nearby locations operated by the third parties, many regional customers do not have this option due to many towns having only one post office – run by Australia Post.

Churchill once said that the Americans always do the right thing, after they’ve exhausted all the alternatives. Perhaps Australia will too.

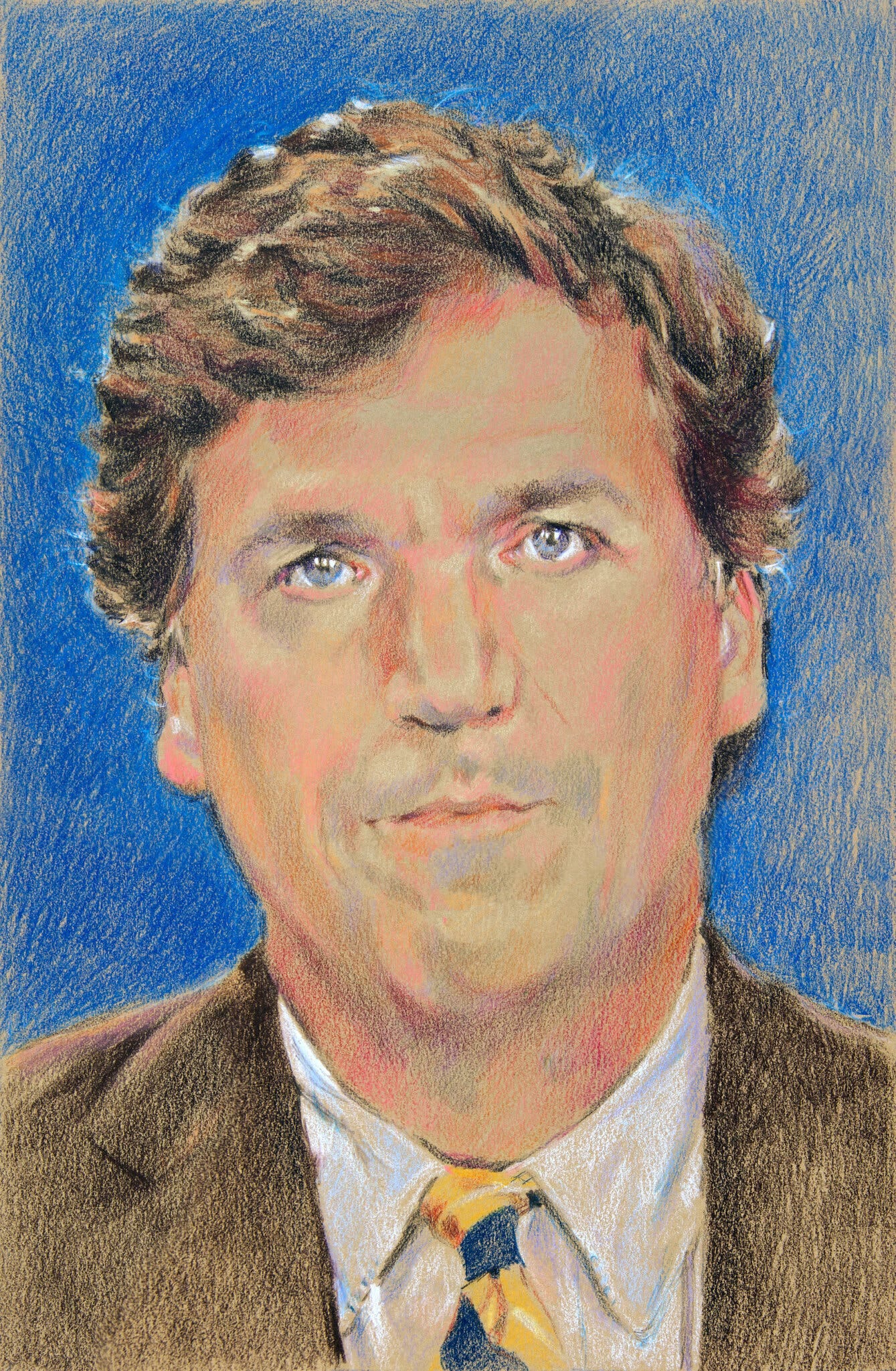

Noah Smith on Tucker

A great, and sad piece which gets right to the heart of things — and to my fascination with Tucker. Tucker represented another stage we were going through. Smith captures this brilliantly the stage at which fellow feeling dies as a source of political communication. With right wing TV pundits before Tucker — like Bill O’Reilly one could disagree with them, but also understand and even sympathise to some extent with where they were coming from. (And understanding requires some level of sympathy in the sense Adam Smith used the term — some level of being able to see through another’s eyes, — by feeling through another’s feelings.) As Smith argues none of that’s true for Tucker whose modus operandi is optimisation and who is, in that sense a cypher.

And Tucker found that he could get more viewers if he broadened his set of targets. Besides Ukraine, he attacked tech companies, pharmaceutical companies, and hedge fund managers. This strategy took advantage of the fact that lots of Americans hold a mix of conservative cultural views and progressive economic views. But it was not done out of any sort of progressivism — only a very few extremely credulous lefties were fooled. Instead, Tucker — like Trump in his 2016 campaign — simply realized that if he attacked a bunch of different targets instead of always focusing on the same old villains, he could generate outrage among a wider set of viewers. It was “populist” only in the sense that it was done for the sake of popularity. Tucker is like an algorithm, doing a brute-force grid search over the space of things that it’s possible to get people mad about, optimizing for attention and money.

Watching Tucker, I often find myself thinking of his predecessor, Bill O’Reilly. It’s a little embarrassing to confess, but I used to enjoy The O’Reilly Factor — not because I liked what Bill had to say, but because he humanized the conservative movement. He was a little bit like the right-wing uncle I never had — he makes you mad as hell at Thanksgiving dinner, but he tells you what he really thinks, and you can understand why he thinks it. When O’Reilly brought people onto his show that he disagreed with, you could tell he was really trying to reason with them, not just optimize for minute-by-minute ratings. I can’t watch Tucker like I could watch O’Reilly. Watching Tucker is more like talking to ChatGPT; you just know there’s nothing behind the words.

And make sure you watch the video. It’s a remarkable performance. Quite the cultural artefact methinks. I’ve written elsewhere about how often comedy gets to the heart of our discourse more directly than the various more ‘serious’ discourses we have. This takes it one further suggesting that in our extraordinary times comedy seems to be the only mainstream genre that can speak to the heart of the matter.

Watch it now!

A sketch of Tucker’s trajectory

He exercised power in ways that were new and unique for a cable star. He was a sophisticated political operator as much as he was a talented television host — to an astonishingly unsettling degree, as he continued to thrive while making racist and sexist comments and earning the praise of neo-Nazis. Like Donald Trump — to say nothing of other Republican politicians and conservative media figures — he gave voice to an anger, sense of grievance and conspiratorial mind-set that resonated with many Americans, particularly those on the far right. Unlike Mr. Trump — not to mention his motley crew of cheerleaders and imitators — Mr. Carlson developed and articulated a coherent political ideology that could prove more lasting, and influential, than any cult of personality. Mr. Carlson has left Fox News. But his dark and outsize influence on the conservative movement — and on American politics — is hardly over. …

When Mr. Carlson met with Mr. Ailes in 2009 to discuss a job at Fox News, Mr. Carlson’s career was at a nadir. He’d been let go from both CNN and MSNBC. He’d developed a game show pilot for CBS that wasn’t picked up. His stint on ABC’s “Dancing With the Stars” lasted just one episode. His finances were so stretched that he’d decided to sell his suburban New Jersey mansion out from under his wife and four children.

“You’re a loser and you screwed up your whole life,” Mr. Ailes told Mr. Carlson, according to an account of the conversation Mr. Carlson later gave to his friend, the former Dick Cheney adviser Neil Patel. “But you have talent. And the only thing you have going for you is that I like hiring talented people who have screwed things up for themselves and learned a lesson, because once I do, you’re gonna work your ass off for me.”

Mr. Carlson didn’t disappoint. …

Against transparency

As Chair of the Government 2.0 Taskforce in 2009, I spent a year or so as Australia’s Mr Transparency. I remember even then thinking that transparency was a Good Thing, but over the decades I’d acquired a natural suspicion of big abstract ideas that everyone knows are good. That’s particularly the case where I can’t get my thoughts properly around the idea. After all, this was at just the time when we were codifying an idea that we’d previously honoured informally — the idea of privacy. If Cabinet are going to have productive discussions they need full and fearless advice. They need to be able to have full and fearless debates before their decisions are made. This isn’t a strong against against transparency necessarily, but it is a strong argument against transparency maximalism.

Since then those hesitations have been borne out — for instance in my discussions with James D'Angelo about the ways in which transparency has harmed American democracy. (Our democracy itself regards secret ballots as sacrosanct. So in that case transparency is bad right?.) Anyway, a reader sent me this piece from the Newyorker. It provides some excellent examples of the difficulties of the area and some tantalising quotes from academics who might have thought deeply on the subject, but we really only ever get them crystallising the problem rather than making much progress towards helping us understand how we should think of transparency.

“There is a standard view that transparency is all good—the more transparency, the better,” the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen, an associate professor at the University of Utah, told me. But “you have a completely different experience of transparency when you are the subject.” In a previous position, Nguyen had been part of a department that had to provide evidence that it was using state funding to satisfactorily educate its students. Philosophers, he told me, would want to describe their students’ growing reflectiveness, curiosity, and “intellectual humility,” but knew that this kind of talk would likely befuddle or bore legislators; they had to focus instead on concrete numbers, such as graduation rates and income after graduation. Nguyen and his colleagues surely want their students to graduate and earn a living wage, but such stats hardly sum up what it means to be a successful philosopher.

In Nguyen’s view, this illustrates a problem with transparency. “In any scheme of transparency in which you have experts being transparent to nonexperts, you’re going to get a significant amount of information loss,” he said. What’s meaningful in a philosophy department can be largely incomprehensible to non-philosophers, so the information must be recast in simplified terms. Furthermore, simplified metrics frequently distort incentives. If graduation rates are the metric by which funding is determined, then a school might do whatever it takes to bolster them. Although some of these efforts might add value to students’ learning, it’s also possible to game the system in ways that are counterproductive to actual education.

Transparency is often portrayed as objective, but, like a camera, it is subject to manipulation even as it appears to be relaying reality. Ida Koivisto, a legal scholar at the University of Helsinki, has studied the trade-offs that flow from who holds that camera. She finds that when an authority—a government agency, a business, a public figure—elects to be transparent, people respond positively, concluding that the willingness to be open reflects integrity, and thus confers legitimacy. Since the authority has initiated this transparency, however, it naturally chooses to be transparent in areas where it looks good. Voluntary transparency sacrifices a degree of truth. On the other hand, when transparency is initiated by outside forces—mandates, audits, investigations—both the good and the bad are revealed. Such involuntary transparency is more truthful, but it often makes its subject appear flawed and dishonest, and so less legitimate. There’s a trade-off, Koivisto concludes, between “legitimacy” and “the ‘naked truth.’ ”

A little perspective on Australia’s recent cold snap

From another time

Sent in by a friend and a reader of the newsletter

Cameron Murray’s HouseMate

Or why we should impose ‘extended access’ on ABC videos

I like the general thrust of this scheme suggested last year by Cameron Murray.

According to economist Cameron Murray, it has managed to boost home ownership for 25-34-year-olds from 60 to nearly 90 per cent over the past four decades, at a time when the percentage of Australians that age who own a home has plunged from 60 to 45 per cent.

So, how have they done it?

"What Singapore has that Australia does not is a public housing developer, the Housing Development Board, which puts new dwellings on public and reclaimed land, provides mortgages, and allows buyers to use their compulsory retirement savings [what Australians call superannuation] for both a deposit and repayments," Murray says.

I could embed the video in which Murray explains the scheme, but it’s made by Our ABC and unlike the commercials, it doesn’t facilitate embedding, just another example of why we need to introduce ‘extended access’ for all government business enterprises — including the ABC.

Arise: the new world chess champion

Terry Eagleton on Charles III

Not a great article by any means. The author writes books and articles like other people breathe, but it kicks off with a a good story of our “fussy, petulant, self-indulgent’ prince and goes on to wonder about the king:

Some years ago, while he was still a lowly Prince of Wales, he granted an audience to some Rhodes scholars from Oxford at a time when I was teaching there. “Who teaches you?” he asked them. “Not that dreadful Terry Eagleton, I hope.” …

I assumed that it was my political views, rather than the cut of my jacket or my reluctance to ride to hounds, that Charles found distasteful, and it was this which disturbed me most. I had imagined that royal persons like himself were set above the political realm, impeccably even-handed in their treatment of Tories and Trotskyists.

Real democracies, which is to say republican ones, don’t work like this. They are the only political form which doesn’t need to invoke a legitimating power external to the people themselves. Instead, the people legitimate themselves, in their everyday speech, action and law-making. This lends them an unusual authority, but it breeds uncertainty as well. It means that political society is founded only in itself, with no pre-written script or divine agenda, and this feels close to a sense of groundlessness. Democracies have to make things up as they go along, more like experimental theatre than Shakespearian drama. “The people” sounds like a firm enough foundation, but in reality the people are divided, diverse and keep changing. This is why democracy is the kind of politics suitable to modernity — to a sense of societies as historical rather than eternal, and men and women as self-fashioning rather than determined by tradition. …

Coronations are solemn charades in which we agree to suspend our disbelief in myth and divine order in order to assuage our fear that, as democrats, we may be standing on nothing more solid than ourselves. As with the currency, it’s our faith in something intrinsically valueless that makes it work. We need an Other, and the Windsors are on hand to provide it. In the days when the monarch had real authority, he or she would dress up in finery partly to dazzle their subjects, but also, as Edmund Burke argues, to cloak and soften the brutality of their power. Kings were men in drag, draping the ugly phallus of their dominion beneath alluring feminine garments.

In the end, however, it doesn’t work all that well. Royalty is meant to represent an oasis of stability and continuity in the increasingly fluid, unstable, unpredictable environment we know as market society. What’s happened instead is that the moral behaviour of that world has now invaded the inner sanctum of the royal family itself, with its litany of break-ups, cock-ups, publicity wars and dysfunctional relationships. It’s worth keeping this in mind as our democracy bows to an unelected head of state.

Thanks to John Simon of Castlecrag for telling me about Audette House

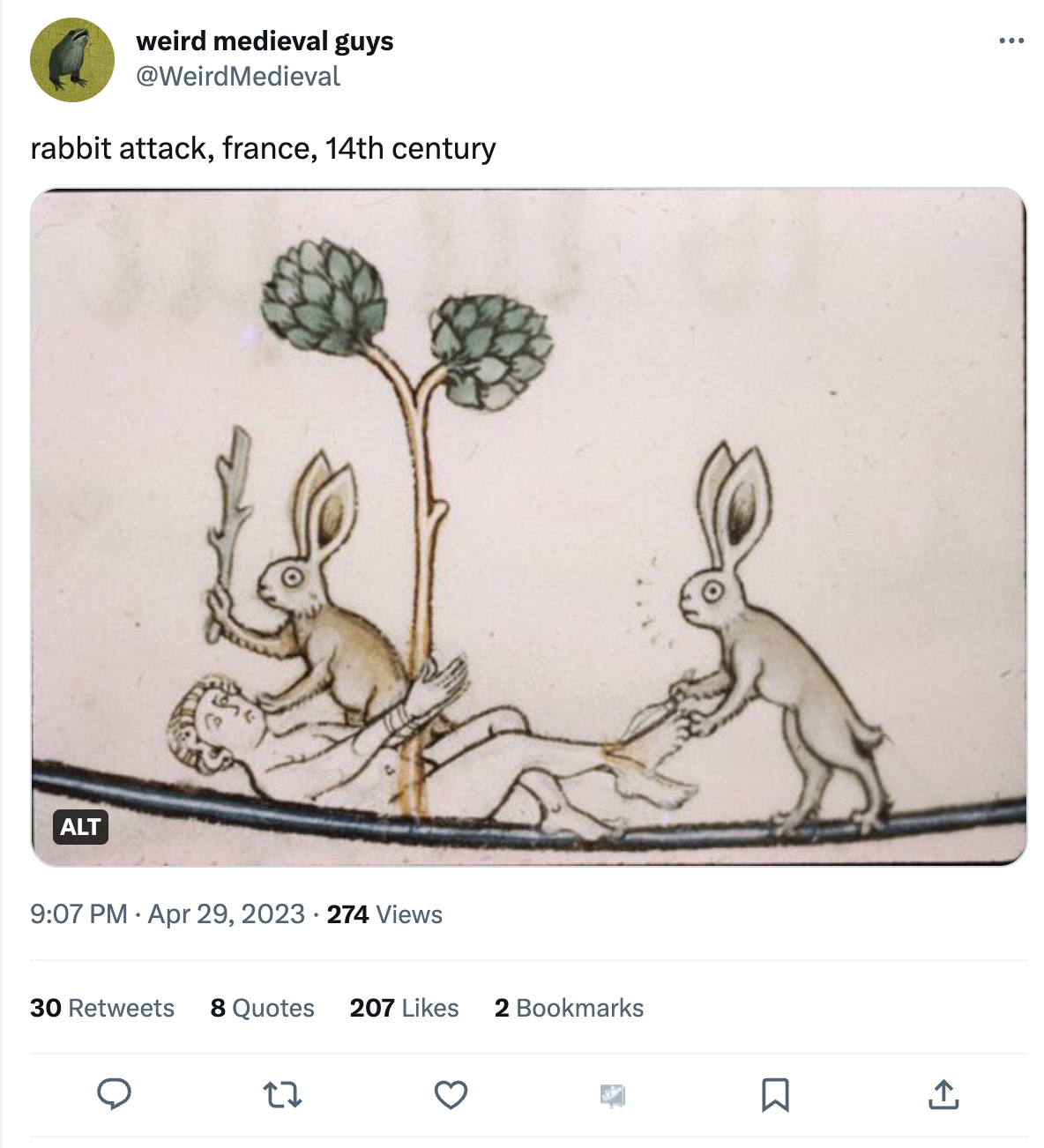

I’m getting to like these weird medieval guys

Patriots: Wake up and smell the crazy

Yes, folks, this is a segment about the US. And Trump.

On Thursday, Trump strolled into a New Hampshire diner to bask in the admiration of his supporters and press the flesh. There, he was confronted by one of his more adoring fans — Micki Larson-Olson, whose red-white-and-blue-streaked hair, USA-themed peaked military cap, and flashy Trump-branded fare conveyed her enthusiasm for the cause. “She’s a Jan. 6er,” one of the restaurant’s patrons called out. Trump did not recoil from this revelation. He was drawn to it. …

“Patriots, I hear the woman,” Trump said of his supporter, who informed him that her misdemeanor conviction resulted in her imprisonment for 161 days. “It’s terrible,” he continued, “what they’re saying is so sad, what they’ve done to January 6.” The Dispatch reporter Andrew Egger identified Larson-Olson, a regular Trump-rally attendee, as the person who identified herself to him as “Q Patriot.” She went on to regale him with tales about how “they used murdered and experimented-with children to create” the Covid vaccines and provided previously unknown details about Pope Francis’s clinical contributions to Operation Warp Speed.

Larson-Olson held nothing back in comments she provided NBC News. “The punishment for treason is death, per the Constitution,” she said, adding that the Republicans who certified the votes of the 2020 election “deserve death.” The Trump superfan hoped she would secure “a front seat” to witness “Mike Pence being executed.”

Lippmann’s The Public Philosophy

(This video is not related to the content below, but is worth watching in its own right.)

A couple of weeks ago I reproduced a section in an early chapter of Walter Lippmann’s The Public Philosophy and as I came upon this section towards the end I thought of you dear reader. A good discussion of the unbalance that comes when rights are not understood as entailing duties. It’s a particularly relevant discussion in our age of algos amping up the agro on social media.

ONLY within a community which adheres to the public philosophy is there sure and sufficient ground for the freedom to think and to ask questions, to speak and to publish. Nobody can justify in principle, much less in practice, a claim that there exists an unrestricted right of anyone to utter anything he likes at any time he chooses. There can, for example, be no right, as Mr. Justice Holmes said, to cry “Fire” in a crowded theater. Nor is there a right to tell a customer that the glass beads are diamonds, or a voter that the opposition candidate for President is a Soviet agent.

Freedom of speech has become a central concern of the Western society because of the discovery among the Greeks that dialectic, as demonstrated in the Socratic dialogues, is a principal method of attaining truth, and particularly a method of attaining moral and political truth. “The ability to raise searching difficulties on both sides of a subject will,” said Aristotle, “make us detect more easily the truth and error about the several points that arise.” 8 The right to speak freely is one of the necessary means to the attainment of the truth. That, and not the subjective pleasure of utterance, is why freedom is a necessity in the good society.

This was the ground on which Milton in the Areopagitica opposed the order of Parliament (1643) that no book should be printed or put on sale unless it had first been licensed by the authorities:

As therefore the state of man now is; what wisdom can there be to choose, what continence to forbear without the knowledge of evil?…Since therefore the knowledge and survey of vice is in this world so necessary to the constituting of human virtue, and the scanning of error to the confirmation of truth, how can we more safely, and with less danger, scout into the regions of sin and falsity than by reading all manner of tractates and hearing all manner of reason? 9

The method of dialectics is to confront ideas with opposing ideas in order that the pro and the con of the dispute will lead to true ideas. But the dispute must not be treated as a trial of strength. It must be a means of elucidation. In a Socratic dialogue the disputants are arguing co-operatively in order to acquire more wisdom than either of them had when he began. In a sophistical argument the sophist is out to win a case, using rhetoric and not dialectic. “Both alike,” says Aristotle, “are concerned with such things as come, more or less, within the general ken of all men and belong to no definite science.” 10 But while “dialectic is a process of criticism wherein lies the path to the principles of all inquiries,” 11 “rhetoric is concerned with the modes of persuasion.”12

Divorced from its original purpose and justification, as a process of criticism, freedom to think and speak are not self-evident necessities. It is only from the hope and the intention of discovering truth that freedom acquires such high public significance. The right of self-expression is, as such, a private amenity rather than a public necessity. The right to utter words, whether or not they have meaning, and regardless of their truth, could not be a vital interest of a great state but for the presumption that they are the chaff which goes with the utterance of true and significant words.

But when the chaff of silliness, baseness, and deception is so voluminous that it submerges the kernels of truth, freedom of speech may produce such frivolity, or such mischief, that it cannot be preserved against the demand for a restoration of order or of decency. If there is a dividing line between liberty and license, it is where freedom of speech is no longer respected as a procedure of the truth and becomes the unrestricted right to exploit the ignorance, and to incite the passions, of the people. Then freedom is such a hullabaloo of sophistry, propaganda, special pleading, lobbying, and salesmanship that it is difficult to remember why freedom of speech is worth the pain and trouble of defending it.

What has been lost in the tumult is the meaning of the obligation which is involved in the right to speak freely. It is the obligation to subject the utterance to criticism and debate. Because the dialectical debate is a procedure for attaining moral and political truth, the right to speak is protected by a willingness to debate.

In the public philosophy, freedom of speech is conceived as the means to a confrontation of opinion — as in a Socratic dialogue, in a schoolmen’s disputation, in the critiques of scientists and savants, in a court of law, in a representative assembly, in an open forum.

Even at the canonisation of a saint, [says John Stuart Mill] the church admits and listens patiently to a “devil’s advocate.” The holiest of men, it appears, cannot be admitted to posthumous honors, until all that the devil could say against him is known and weighed. If even the Newtonian philosophy were not permitted to be questioned, mankind could not feel as complete assurance of its truth as they now [1859] do. The beliefs which we have most warrant for, have no safeguard to rest on, but a standing invitation to the whole world to prove them unfounded. If the challenge is not accepted, or is accepted and the attempt fails, we are far enough from certainty still; but we have done the best that the existing state of human reason admits of; we have neglected nothing that could give the truth the chance of reaching us: if the lists are kept open, we may hope that if there be a better truth, it will be found when the human mind is capable of receiving it; and in the meantime we may rely on having attained such approach to truth, as is possible in our day. This is the amount of certainty attainable by a fallible being, and this is the sole way of attaining it.13

And because the purpose of the confrontation is to discern truth, there are rules of evidence and of parliamentary procedure, there are codes of fair dealing and fair comment, by which a loyal man will consider himself bound when he exercises the right to publish opinions. For the right to freedom of speech is no license to deceive, and willful misrepresentation is a violation of its principles. It is sophistry to pretend that in a free country a man has some sort of inalienable or constitutional right to deceive his fellow men. There is no more right to deceive than there is a right to swindle, to cheat, or to pick pockets. It may be inexpedient to arraign every public liar, as we try to arraign other swindlers. It may be a poor policy to have too many laws which encourage litigation about matters of opinion. But, in principle, there can be no immunity for lying in any of its protean forms.

In our time the application of these fundamental principles poses many unsolved practical problems. For the modern media of mass communication do not lend themselves easily to a confrontation of opinions. The dialectical process for finding truth works best when the same audience hears all the sides of the disputation. This is manifestly impossible in the moving pictures: if a film advocates a thesis, the same audience cannot be shown another film designed to answer it. Radio and television broadcasts do permit some debate. But despite the effort of the companies to let opposing views be heard equally, and to organize programs on which there are opposing speakers, the technical conditions of broadcasting do not favor genuine and productive debate. For the audience, tuning on and tuning off here and there, cannot be counted upon to hear, even in summary form, the essential evidence and the main arguments on all the significant sides of a question. Rarely, and on very few public issues, does the mass audience have the benefit of the process by which truth is sifted from error — the dialectic of debate in which there is immediate challenge, reply, cross-examination, and rebuttal. The men who regularly broadcast the news and comment upon the news cannot — like a speaker in the Senate or in the House of Commons — be challenged by one of their listeners and compelled then and there to verify their statements of fact and to re-argue their inferences from the facts.

Yet when genuine debate is lacking, freedom of speech does not work as it is meant to work. It has lost the principle which regulates it and justifies it — that is to say, dialectic conducted according to logic and the rules of evidence. If there is no effective debate, the unrestricted right to speak will unloose so many propagandists, procurers, and panderers upon the public that sooner or later in self-defense the people will turn to the censors to protect them. An unrestricted and unregulated right to speak cannot be maintained. It will be curtailed for all manner of reasons and pretexts, and to serve all kinds of good, foolish, or sinister ends.

For in the absence of debate unrestricted utterance leads to the degradation of opinion. By a kind of Gresham’s law the more rational is overcome by the less rational, and the opinions that will prevail will be those which are held most ardently by those with the most passionate will. For that reason the freedom to speak can never be maintained merely by objecting to interference with the liberty of the press, of printing, of broadcasting, of the screen. It can be maintained only by promoting debate.

In the end what men will most ardently desire is to suppress those who disagree with them and, therefore, stand in the way of the realization of their desires. Thus, once confrontation in debate is no longer necessary, the toleration of all opinions leads to intolerance. Freedom of speech, separated from its essential principle, leads through a short transitional chaos to the destruction of freedom of speech.

It follows, I believe, that in the practice of freedom of speech, the degree of toleration that will be maintained is directly related to the effectiveness of the confrontation in debate which prevails or can be organized. In the Senate of the United States, for example, a Senator can promptly be challenged by another Senator and brought to an accounting. Here among the Senators themselves the conditions are most nearly ideal for the toleration of all opinions. 14 At the other extreme there is the secret circulation of anonymous allegations. Here there is no means of challenging the author, and without any violation of the principles of freedom, he may properly be dealt with by detectives, by policemen, and the criminal courts. Between such extremes there are many problems of toleration which depend essentially upon how effective is the confrontation in debate. Where it is efficient, as in the standard newspaper press taken as a whole, freedom is largely unrestricted by law. Where confrontation is difficult, as in broadcasting, there is also an acceptance of the principle that some legal regulation is necessary — for example, in order to insure fair play for political parties. When confrontation is impossible, as in the moving picture, or in the so-called comic books, there will be censorship.

I live in terror that something I've ordered will end up in the "transport hub" north of Hobart. I live 20KM south of Hobart and would have a return journey of 80km while passing innumerable POs, including the GPO.