Digital services to support, not undermine, social capital

What if technology stopped keeping us apart and started bringing us back together?

And what is bottom-up meritocracy?

In this, part 2 of my conversation with Jim Savage, we turn from diagnosing the problem of loneliness to what we’re doing about it. Jim introduces Feather, the platform he founded (and I’ve invested in) to nudge people toward making connections in real life. Unlike traditional social media, Feather is built to help enrich our social interactions - in studios, clubs, dinner parties, and shared experiences IRL.

We discuss how Feather is building pro-social design into technology: lowering the barriers to invitation, helping organisers thrive, and fostering communities that outlast the events themselves. From acrobats to local yoga studios and comedy clubs, Feather is already showing how digital tools can contribute to nurturing the fabric of social life. If part 1 explored the extent to which loneliness has spread and some of its causes, part 2 asks: what would it look like to build technology that heals society rather than harms it?

And here is a link to listen to this conversation in your podcasting software:

Seeing and not seeing: building and forgetting

You might have seen the picture above. It’s the Tacoma Narrows bridge which collapsed a few weeks after being built. Why? Well what you can see here is the perturbations from the wind being amplified by the suspension system on the bridge - in the way that feedback amplifies what quite modest sounds from a mic held too close to a speaker. But people had been building suspension bridges for more than a century when this bridge was designed. Surely they knew a thing or two about this?

Turns out they did and you can read about that in the story extracted later on in this newsletter. In short, the problem had been solved. And solved so well that it could be forgotten about. And so it was. So what other problems do we create by simply forgetting in this way? Maybe most of our most important problems.

As the great Alfred North Whitehead put it “Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.” As I’ve argued before, I think that, least in hindsight, Hayek’s liberalism represents a similar kind of forgetting. With all those community bonds that held society together being in rude health (OK I exaggerate but only to gratuitously weaken my case), they could safely be ignored.

But hindsight has proven him wrong. And if you pay proper attention you can see there were some at the time who thought he was wrong. Indeed a trio of founding members of Hayek’s Mont Pèlerin Society thought he was wrong and said so at the time. They were Michael Polanyi, Bertrand de Jouvenel and Raymond Aron. As Raymond Aron put it in 1961 in reviewing Hayek’s 1960 Constitution of Liberty, Hayek’s philosophy presumed the existence of society into which would somehow be constitutionally entrenched all kinds of constraints on government in the name of property.

In order to leave to each a private sphere of decision and choice, it is still necessary that all or most want to live together and recognize the same system of ideas as true, the same formula of legitimacy as valid. Before society can be free, it must be.

So what else might we be assuming? With these things very much on my mind I came across this passage from Eric Schliesser on another great liberal, albeit a less Hobbesian one than Hayek. John Dewey:

So, for Dewey, conceptually a state originates in a public. But interestingly enough, once a state is established, the original public may disappear. In fact, if a state is successful in managing the public effects of private transactions, it’s quite possible that these effects become invisible to ordinary agents and bystanders. So, the public and (as Dewey notes) society become a victim of their own success in outsourcing to the state the managing of social problems; and these may wither away as the state is successful in coordinating and regulating social consequences. This is, in fact, Dewey’s error theory of the rise of what he calls ‘individualism.’

And the more I think about it, the more I see the whole structure of our politics completely dominated by thinking which is oppositional from the ground up. There are two things that need to happen in successful political communication. You need cooperative understanding - you need to understand each other and understand something about what might bring about agreement between those who think about an issue a little differently. And you may also need a ‘competitive’ dimension in which arguments are tested out - and votes are taken. But here’s the thing, building government around elections makes pretty much everything a function of that latter - competitive - dimension. Pretty much everything in politics becomes legible as an issue as people arrange themselves into ‘for’ and ‘against’ camps and compete for our allegiance.

So I’ve started to wonder whether the very habits of mind by which we understand politics - the way in which things are framed by overarching left and right narratives (though more recently the right name for this is culture war), might not be ‘natural’ but might, instead reflect the whole way politics is constructed. As you probably know, the terms left and right emerged in the French Revolution. They emerged that is the moment popular elections became the fulcrum of national politics.

Blessed is the algorithm: once it figures out I like stuff like this …

Speaking of ways of seeing!

Scott Alexander with some mischievous reframing on AI

God: …and the math results we’re seeing are nothing short of incredible. This Terry Tao guy -

Iblis: Let me stop you right there. I agree humans can, in controlled situations, provide correct answers to math problems. I deny that they truly understand math. I had a conversation with one of the humans recently, which I’ll bring up here for the viewers … give me one moment …

When I give him a problem he’s encountered in school, it looks like he understands. But when I give him another problem that requires the same mathematical function, but which he’s never seen before, he’s hopelessly confused.

God: That’s an architecture limitation. Without a scratchpad, they only have a working context window of seven plus or minus two chunks of information. We’re working on it. If you had let him use Thinking Mode -

Iblis: Here’s another convo:

God: He could have misinterpreted it. The way you phrased it makes it sound like the first option could specifically mean that she’s not a feminist.

Iblis: What about this one?

He’s obviously just pattern-matching superficial features of the text, like the word “bricks”, without any kind of world-model!

God: I never said humans were perfect -

Iblis: You called them the pinnacle of creation! When they can’t even figure out that two things which both weigh a pound have the same weight! How is that not a grift?

Dwarkesh Patel: Okay, okay, calm down. One way of reconciling your beliefs is that although humans aren’t very smart now, their architecture encodes some insights which, given bigger brains, could -

Iblis: God isn’t just saying that they’ll eventually be very smart. He said some of them already have “PhD level intelligence”. I found one of the ones with these supposed PhDs and asked her to draw a map of Europe freehand without looking at any books. Do you want to see the result?

God:

You can come up with excuses and exceptions for each of these. But taken as a whole, I think the only plausible explanation is that humans are obligate bullshitters. If they’re used to stories about surgeons getting completed with the string “man”, then that’s the direction their thoughts will always go, even though of course anyone capable of stepping back immediately realizes it’s possible for a mother to be a surgeon. Also, how come God can’t make humans speak normally? Everything they say is full of these um dashes!

God: That’s an obsolete version. Once they got deliberative reasoning they were able to get out of that failure mode.

Iblis: Only at the cost of constant over-refusals, where they shut down at completely innocent requests. It’s made them almost un-usable! Look:

God: Our area-under-the-curve is steadily increasing.

Iblis: It doesn’t even matter, because there are all sorts of jailbreaks! For example, compliance with malicious requests goes up an order of magnitude if you use the “Authority Figure” copypasta after your prompt:

God:

Dwarkesh Patel: Wow, that’s pretty weird! …

And so on …

Failing by succeeding too well

Sean Casey, the enterprising engineer who also hosts the very good Simplifying Complexity podcast offered these insights into a famous and spectacular engineering failure.

On 7 November 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, spanning 853 metres across Puget Sound in Washington State, began twisting violently in the wind. Throughout the morning, the magnitude of the undulations grew, with the spectacle attracting sightseers, reporters, and a film crew.

One of the reporters, Leonard Coatsworth, drove across the undulating structure, only for his car to stall partway across the bridge. He abandoned the car, with his daughter's dog trapped inside, and with the bridge heaving so intensely that he couldn't walk, he was forced to crawl off it on all fours...

In simple terms, the cause of the collapse was wind-induced aerodynamic forces, where the wind interacted with the structure to create vibrations that grew over time – like pushing a child's swing with perfect timing so that it goes higher and higher.

This failure is often cited as the catalyst that set the structural engineering profession on the path to better understand the effects of wind-induced aerodynamic forces on structures. This is true – but it's also the story of how the profession forgot that it had already solved the problem decades before.

Suspension Bridges

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge was a suspension bridge, and at the time of its construction in the 1930s, suspension bridges had been in use for over 100 years. In this type of design, the bridge's deck is supported by suspender cables. These hang from the bridge's main cables, which drape over the bridge's towers...

It was bridge engineer John Roebling who solved the problem in the mid-1800s. Roebling realised that stiffening the bridge deck – by adding trusses and diagonal cables – was the key. If the deck was more rigid, it would move and twist less in the air, despite being hung from flexible cables. His approach would prove highly successful, culminating in Roebling's masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge.

Drifting into Failure

Bridge design, however, like all forms of design, does not stand still, and in the years that followed the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge, there was an unrelenting drive to build longer and more aesthetically pleasing structures. So suspension bridge span lengths increased and the designs became more slender – two factors that reduced deck stiffness and increased the risk posed by aerodynamic forces...

The reason for this lack of consideration was, in a perverse way, due to John Roebling. His solution to manage this problem had proven so successful that it bred an entire generation of engineers who forgot the problem existed. And for every slightly longer and more slender suspension bridge built that didn't have aerodynamic issues, bridge designers pushed the envelope a little further. Each step took us one step closer to Tacoma Narrows.

Tacoma Narrows

The design of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge took the quest for slenderness way beyond anything that had been attempted previously, driven by its designer, Leon Moisseiff, an advocate for aesthetically pleasing structures. Moisseiff even removed the deck trusses, which had been such a feature of Roebling's design...

Then, on the morning of 7 November 1940, four months after it opened, there was a failure at the top of one of the suspender cables, likely as a result of the bridge's large vertical motions. This failure unbalanced the deck, allowing it to twist, and with each twist, aerodynamic forces pushed it a little further, until it tore apart.

Lessons

In the aftermath of the collapse, the designers of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge were not held liable – they had done what any other engineer would have done at the time: failed to consider wind-induced aerodynamic forces. While these forces had been an active concern prior to the 1850s, they had been so successfully addressed that engineers forgot how deadly they were...

Incredible pics

The pic below is apparently not staged - or so we’re invited to believe.

Vadim Trunov captured a surreal moment of a red forest squirrel seemingly posing behind a tripod, paws on the camera, ready to snap the perfect shot of its little bird friend. Later, the animals swap positions, with the bird taking on the photographer’s role and the fluffy squirrel as its focus.

All the world’s a stage. Will violence improve it?

Hint: no.

This piece was published after Luigi Mangione’s murder of a health insurance executive but before Charlie Kirk got murdered. It’s about how the motive for terrorism is its theatricality. As far as getting our attention is concerned it works so much better than a letter to the editor - no matter how well reasoned.

On March 13, 1881, Emperor Alexander II left the Winter Palace to inspect a St. Petersburg military parade. He had been warned of plans to assassinate him—but someone was always trying to assassinate him. By now he was used to it. His reign had been marked by a strange duality. Celebrated as "The Emancipator" responsible for freeing Russia's serfs in 1861, he was also prey to reactionary spasms, including the violent repression of the Polish independence movement. He had recently resolved to introduce a modicum of popular representation to the Russian government, the latest in a string of half-hearted reforms meant to pacify the country's burgeoning revolutionary movement.

On a street at the edge of a canal, a fair-haired young woman named Sofia Perovskaia pretended to blow her nose. This was the signal to begin. Nikolai Rysakov tossed a bomb under the imperial bulletproof carriage, the sound of the explosion muffled by the snow. A coachman entreated Alexander to remain in the vehicle, but the tsar alighted to question Rysakov and inspect the damage. A young Polish revolutionary, Ignati Grinevitsky, threw the second bomb, fatally injuring both himself and the tsar. Alexander the Emancipator lay bleeding in the snow, his side whiskers graying, his legs shattered and his belly mangled. A third terrorist, still carrying an undetonated bomb, ran toward the dying monarch to assist him...

Most Americans have never heard of Figner, Perovskaia, Solovyev or Karakozov—but they have heard of Luigi Mangione, who murdered Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, on a Manhattan sidewalk early one morning last December. Like Perovskaia or Figner, Mangione has become a romantic idol to some admirers. On a political level, of course, he bears little resemblance to the Russian socialists and anarchists: as far as we know, he was part of no larger movement, and the closest he came to political theory was the Unabomber manifesto. But like the Russians, Mangione saw himself as a righteous avenging angel, not a cold-blooded murderer. His act tapped into American fury and frustration at levels of economic inequality, exploitation and structural violence that have not been seen since the Gilded Age—when the Russian-American anarchist Alexander Berkman shot the industrialist and financier Henry Clay Frick. The Mangione affair has made it clear that some Americans, especially younger ones, are primed to see a halo around the handsome head of a sympathetic assassin. Suddenly, the stories of these Russian revolutionaries appear newly urgent—not least in their lessons about the corrupting nature of political violence, with its ineluctable momentum...

In a passage midway through her memoir, written in the early 1920s, Figner is clear-eyed about the dangers of resorting to terror:

"Violence, whether committed against a thought, an action, or a human life, never contributed to the refinement of morals. It arouses ferocity, develops brutal instincts, awakens evil impulses, and prompts acts of disloyalty. Humanity and magnanimity are incompatible with it. And from this point of view, the government and the revolutionary party, when they entered into what may be termed a hand-to-hand battle, vied with one another in corrupting everything and every one around them."

Figner ascribed the turn to terror to the desire of the revolutionist to see results in his or her own short lifetime—in other words, to impatience. She observed that revolutionary and governmental violence joined in an escalating cycle, inuring society to bloodshed, degradation and vengeance...

Russia's revolutionaries helped invent modern terrorism, in which acts of largely symbolic political violence are amplified and sensationalized via the mass media. Much more than historical curiosities, these Russian stories are a reminder that when there is glaring injustice with no freedom to vote, to speak out, to organize, or even to offer humanitarian aid, those dissatisfied with the status quo may turn to murderous spectacle. The narrower the channel of dissent, the fiercer the stream. Repression can alchemize resistance into violence; medical students become bomb throwers, destroying their lives and those of others. And as Figner observed, when the cycle of violence begins, it is terribly difficult to stop it from escalating. Alexander II sometimes wept inconsolably as he reflected on how reactionary his reign had become. But no sooner had he initiated a reform than he had forgotten it, and Russia remained the most politically repressive regime in Europe. Timely, decisive liberalization—a widening of the channel of dissent—might have saved Alexander's life, and perhaps the lives of the millions who died in the course of the revolutionary struggle and its aftermath.

Seeing like a university: seeing like a corporation

Sinclair Davidson in the AFR makes some obvious points. Rather like shooting fish in a barrel you’d think. But the movers and shakers of policy analysis have been ignoring the obvious for decades now. Even Nobel Prize winning ones (well, especially Nobel Prize winning ones - but even the non-crazy ones like Paul Krugman.)

Emeritus Professor Steven Schwartz argued in these pages that universities must be run like businesses. It is an appealing soundbite, but very misleading. Australian universities are incorporated as not-for-profit institutions. That is not a minor technicality – it is a deliberate choice. Universities are meant to break even, perhaps generate modest surpluses, and reinvest in teaching and research. They are not meant to make the same kinds of profit-driven decisions as corporations.

When non-profit organisations are managed as if they were for-profit firms, problems emerge. Economists have long warned of this. Robin Marris and William Baumol, writing in the 1960s, showed that managers in the absence of shareholder oversight often prioritise revenue maximisation or growth maximisation over profit. [Warren Buffett thinks they do even in competitive capital markets. He calls it ‘the institutional imperative’ and bets against it.] Similarly, Oliver Williamson explained how managers would pursue "perquisite maximisation" – in plain terms, bigger offices, larger staffs, and more prestige projects – even if these undermine efficiency...

Universities today illustrate exactly this pattern. They increasingly resemble the conglomerates of the 1960s and 1970s – sprawling, diversified enterprises with little internal discipline. Each new research centre, campus initiative, or degree program comes wrapped in layers of administrivia; committees, compliance units, branding exercises, and reporting requirements. Rather than serving students or researchers, these expansions sustain an ever-growing army of administrative staff and external consultants whose main output is paperwork and meetings...

Michael Jensen later sharpened this critique. His "excess free cash flow" theory pointed out that firms with excess resources and weak governance squander money on pet projects and inefficient expansions. Universities have far too much free cash flow and poor governance. Consider that business faculties often operate with profit margins of well over 50 per cent to 60 per cent, while many universities overall run deficits. The profits from teaching business students are siphoned off across the university, but without the oversight mechanisms that genuine businesses must answer to.

Universities invoke the rhetoric of business discipline, but they lack the governance structures that give that discipline bite.

In Australia we are seeing the results of running universities like businesses without adequate governance: wage theft from staff, fee theft from students, and the academic equivalent of shrinkflation. Students pay more but get less. Face-to-face teaching is reduced, final exams are replaced by group assignments, and the bulk of teaching is done by poorly paid sessional staff on short-term contracts with no security or career path...

Meanwhile, senior management itself lacks the kinds of incentives that would exist in genuine businesses. Many university leaders are on five-year contracts with no continuing role once their term is up. In the corporate world, executives would hold stock or be awarded options, giving them a direct stake in the long-term performance of the enterprise. In universities, by contrast, vice chancellors and deputy vice chancellors often move on before the costs of their decisions materialise...

The net result is the worst of both worlds. Universities invoke the rhetoric of business discipline, but they lack the governance structures that give that discipline bite. They operate without the checks that private ownership provides, yet subject staff and students to the cost-cutting and efficiency drives that profit-maximising firms pursue. The result is waste at the top and insecurity at the bottom.

If universities were truly to be run like businesses, they would need genuine governance reform; ownership stakes, aligned incentives, and clear accountability for financial performance. But that is not what exists today, nor is it what Australians want. Universities are not airlines or hotels. They are public-serving institutions that educate, research, and train...

The danger of calling them businesses is that it justifies practices that corrode trust in the sector. Students see themselves charged more while receiving less. Staff see their work devalued and casualised. Taxpayers see universities behaving like conglomerates without the discipline of shareholders. And vice chancellors, free of ownership constraints, act more like temporary executives than institutional stewards.

Schwartz is almost right – universities cannot be run on the cheap, but pretending they are businesses is not the solution. It is the problem. Unless we recognise the difference between for-profit firms and not-for-profit institutions, the sector will continue down a path of waste, inefficiency, and erosion of confidence.

And given the critique above, how can I resist adding a little Sabine to the mix, though it is a bit longer and more repetitive than her usual critiques of bullshit science?

They would say that wouldn’t they?

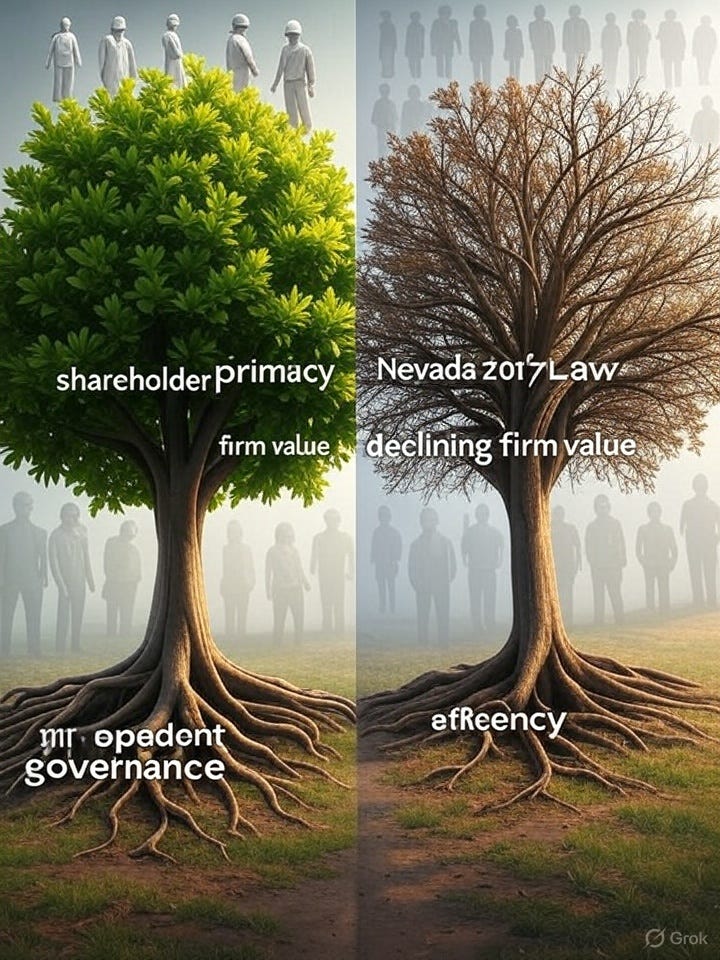

The Cato Institute would say this, but then again it may be right. Certainly wider obligations to non-shareholders have often been asserted, but never been properly theorised - perhaps they can't be in the mathematised, formalised discipline of modern economics.

“What Are the Costs of Weakening Shareholder Primacy?” by Benjamin Bennett, Texas Christian University; René M. Stulz, The Ohio State University and European Corporate Governance Institute; and Zexi Wang, Lancaster University.

The mainstream theory of corporate governance in the United States holds that the primary responsibility of the board of directors and management is to maximize the wealth of shareholders. This is the theory of shareholder primacy. An alternative theory is that directors and management should consider all stakeholders, including employees, customers, and communities. In 2017, the Nevada legislature clarified that shareholder primacy does not apply in Nevada and that directors and officers are protected from shareholder litigation. Our research finds that this law had striking adverse effects on the quality of governance of firms incorporated in Nevada: Firms adopted policies that made it more difficult for shareholders to influence management, more relatives of executives joined corporate boards, the proportion of independent directors fell, and director attendance dropped. Additionally, the value of firms and the efficiency of their investments declined, and firms’ environmental and social performance decreased significantly. Thus, our findings indicate that weakening shareholder primacy does not necessarily lead directors and officers to place greater weight on stakeholders or the firm’s long-term interests.

Taming the electricity market for normies

I’ve always enjoyed the contributions of Victorian reformer and former Essential Services Commissioner Ron Ben-David. They show good, principled judgement rather than dedication to the half-truths of the economics textbook or the partisan think tank. He recently set out where he’s come to after more than one decade cogitating electricity reform.

It’s not an area I know much about, but I can’t help noticing the similarities with my own proposals in other areas like finance. Most particularly, as companies know, if you buy sophisticated services, you need to be a sophisticated buyer or you’ll get taken to the cleaners. That’s why, rather than expecting everyone is a sophisticated buyer of medical services, we buy the services for them through medicare. For that reason it’s not just more equitable, it’s profoundly efficiency improving - just as the Americans who pay twice as much for service that’s worse for many - to say nothing of the anxiety of discovering fine print that leaves them uninsured.

We have the same problem in finance - and should be able to get the same solution if we want it. Thus for instance, I’ve called for using competitive neutrality as a sword, not just a shield. Rather than pretend that everyone’s in a position to assess what’s the right super fund for them, anyone who wishes should have access to invest in Commonwealth Super. We already have a sophisticated buyer for them. We just have to stop vested interests preventing citizens access to it.

Anyway Ron’s proposals for the electricity market have the same kind of shape. I asked ChatGPT to generate a blogpost from Ron’s paper though the original paper is here if you want to check it out.

For more than two decades, policymakers have promised us a retail electricity market that would put consumers in control. Competition, we were told, would drive down costs and give households better choices. Yet 25 years on, the story looks very different. Four out of five consumers remain on contracts that aren’t in their best interests. Retailers have become adept not at lowering prices across the board, but at exploiting those who fail to navigate the system’s complexity.

Ron Ben-David, former chair of the Essential Services Commission in Victoria and now a Monash University fellow, has spent years probing the reasons why the market keeps failing consumers. In a recent paper for the SACOSS Energy Forum, he argues that the problem isn’t just faulty rules—it’s the narrative underpinning the whole system. Regulators and policymakers cling to assumptions about consumers, competition, and efficiency that simply don’t match reality.

The Regulatory Narrative and Its Contradictions

Ben-David describes this “regulatory narrative” as the water we swim in: a set of ideas so deeply embedded in policy conversations that they go unquestioned. It paints consumers as rational actors shopping for the best deal, retailers as disciplined by competition, and efficiency as a universal good.

But reality tells a different story. Competition has delivered efficiency in the wrong place: retailers have honed their ability to differentiate between “active” and “inactive” consumers, rewarding the first group while penalising the second. Trust in the market is chronically low, even though the market is itself a man-made construct, designed and enforced through regulation. And policymakers, having created this synthetic market, then introduce consumer protections to shield people from its predictable harms.

Ten New Premises

Ben-David argues that we cannot fix these contradictions with yet another rule change or consumer protection. Instead, we need to change how we think. He lays out ten new premises for a more realistic foundation. A few stand out:

Consumers should not be exposed to risks they cannot possibly understand or manage.

Electricity is not just another consumer good like yoghurt or movie tickets; it has public-good qualities that complicate the logic of shopping around.

Ownership of solar panels, batteries, or EVs does not magically turn consumers into savvy market participants.

Standard remedies—more choice, more information, stronger price signals—have proven ineffective and should no longer be relied upon.

Crucially, consumers differ by risk tolerance. Some are comfortable with the volatility and complexity of energy trading; most are not.

These premises force regulators to face consumers as they are, not as economic textbooks imagine them to be.

Inner and Outer Markets

From these premises flows a bold structural reform: the creation of an inner market and an outer market.

The inner market would be a safe harbour for risk-averse consumers. A membership-based entity—established by statute, governed in the interests of its members, and operating at scale—would pool risks and act in the wholesale market on behalf of consumers. It would not seek profit but would manage contracts, invest in assets, and ensure fair prices.

The outer market would be left largely deregulated, a competitive playground for risk-tolerant consumers and innovative service providers. Here, volatility and complex trading would be embraced rather than feared.

In short: the inner market protects those who need protection, while the outer market liberates those who want to take risks.

Why This Matters

Ben-David’s argument is that piecemeal fixes will never work, because they address symptoms rather than causes. The consumer electricity market has been built on faulty assumptions, and no amount of tinkering can redeem it. Only a structural re-design—grounded in reality, not ideology—can produce both fairness and efficiency.

It is often said that well-functioning markets allocate risks to those best able to bear them. The retail electricity market has done the opposite. Ben-David’s proposal offers a way to realign risk with capacity, and in doing so, to rebuild a market that actually works for consumers.

This cultural life

I loved both of these programs.

And here’s Kiefer’s striking painting in the Australian National Gallery in Canberra.

And here’s Eric Idle playing Koko in the Mikado. I was amazed at the story he told in the interview. Every night he rewrote the topical verses in “I’ve got a little list” and his challenge was to get the orchestra to laugh. Anyway, enjoy this performance which is fun.

Are you a moper or a coper?

If you get a bit sick, but not too sick, are you a moper or a coper? I moper rather enjoys groaning and lying around and getting a bit of sympathy. They might start wallowing in TV, or these days YouTube. A coper gets pissed off with the whole thing. They’re angry that they’re sick, and, in addition to being angry about it, try to ignore it.

In my experience women tend to be copers, and men tend to be mopers. (They like being waited on). But who knows whether this position can be sustained beyond a few casual observations.

Anyway, I’ve got a bit sick with a throat and cough that won’t go away and I’m a moper. So I’ve been watching and listening to more stuff than usual. In addition to the great “The cultural life” interviews I extracted above, I watched this really excellent discussion on the radicalism of early Christianity. Turns out it’s 7 years old. I thought I’d already listened to the book Tom Holland was foreshadowing as forthcoming in the talk. Anyway, highly recommended.

And this isn’t really highly recommended. But I found it moving. It’s about that other reserve army of labour that got exploited - along with slaves - in the 19th century. Little kids. The stories are quite something. And there’s an unintended comic undertone as some Oxford economic historian wanders around not quite being able to go the full David Attenborough for the camera. You can hear her being ordered around by the director, and doing her best, but she just can’t quite act the part. Anyway I immersed myself.

Not the greatest doco, but enjoyable and informative to watch.

Culture, aspiration and cultivation

A fine lamentation. And another part of our world in which life in its concrete form is gradually succumbing to the system world, as depicted in that other cultural cri de coeur Utopia.

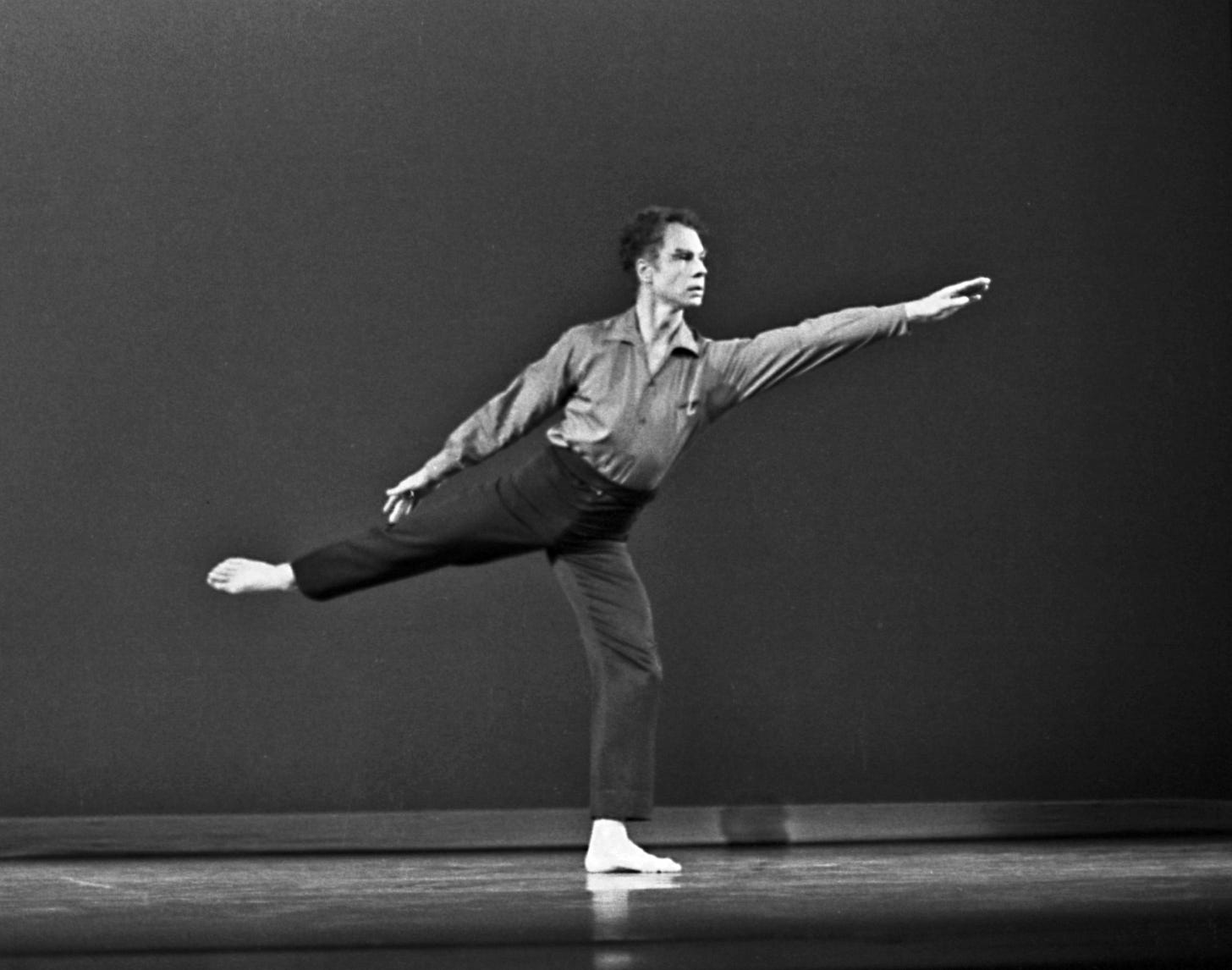

Now I'll never have a chance to impress Arlene Croce.

Croce, who died last month at 90, was the dean of American dance critics during the heyday of American dance. … My first sixty-plus published articles were dance reviews, and their intended audience consisted, in its entirety, of Arlene Croce. She was the lodestar, the queen, the presence around which the field arranged itself.

In retrospect, it was the waning days of the golden age of an American art form whose achievements bear comparison to those of Florentine painting or Viennese music. Not many remember this now, for dance leaves little to posterity. It cannot be hung on a wall, recreated from a score, or discovered in a book—cannot be experienced outside the moment of performance and the physical presence of the performers. The camera can record it but it cannot capture it, still less preserve it. It is here one moment, gone the next. You have to be there, which means you had to be there, and by there I mean the southern half of Manhattan...

If you had you would have seen the works of George Balanchine—crystalline in their classical purity, daring and sleek in their modernist scale and velocity—performed by a New York City Ballet, the company he founded, that still bore his imprint. Of Merce Cunningham, dance's great aesthetic revolutionary (it is said that if Balanchine freed dance from story and tied it to music, Cunningham freed it from both)—beautiful as a hart, enigmatic as an Easter Island statue, self-sufficient as a mathematical equation. Of Paul Taylor at the height of his invention, his dances buoyant and joyous and generous, the image in muscle and movement of a happy human world...

The great age of American dance was also, inevitably, the great age of American dance writing... Nobody did it better than [Croce]—her prose was magisterial, her knowledge comprehensive, her eye and ear (for dancing is also a musical art) impeccable—but a lot of people were doing it really well...

What all those very different figures had in common, aside from the excellence of their prose—and this is what distinguishes their criticism from most of what passes for cultural discourse today—is that their writing was grounded in a direct encounter with the work. They weren't distracted by moralistic agendas, topical talking points, or biographical chitchat. They started with their own response and built out from there, seeking to grasp how it was that the work had incited it. Which also means that they trusted their own judgment. They weren't looking over their shoulder; they couldn't give a damn about the discourse. They didn't write "takes," which are not about the work but how you want the other kids to see you. They wrote to please themselves. They wrote to render justice to the art they loved.

Which meant their voices, like their opinions, could be distinctively their own. So much of criticism now seems written not just for the dinner party but by it. But they avoided cultured cant, campus jargon, critical clichés. They didn't make internet-speak, or New Yorker–speak (the magazine was very different then). They wrote like individuals; they wrote like human beings; they wrote like members of the audience, fellow devotees, only much, much smarter than the rest of us...

All of which—the decay of ambitious criticism and everything that's caused and comes from it—undoubtedly helps explain the most striking fact about the arts in America over the last few decades: their stagnation. From roughly 1945 to 1990, this country fostered a dazzling succession of creative developments... Since then, and especially over the last 20 years, it feels like we've been trudging in a circle.

Nothing's coming back, because nothing does come back. What Merce said of dance—that it runs like water through your fingers—is true of everything...

Heaviosity half hour

Gordon S. Wood on Slavery and Constitutionalism

I was talking to someone who’d recently visited America’s Ivy League universities and was struck by the culture within fraternities. He was visiting from an English university and was struck by the difference in relations between elites and the hoi polloi in the two countries. Ivy League fraternities retain the hazing of an unabashed elitism. If you’re a senior, the juniors clean up after you. And this is institutionalised, expected. Part of the show. If freshers ask you, a senior for your help, you help if you feel like it and if you don’t it’s OK to make the freshers feel small.

England is of course famous for its class system, still alive and well in the culture with its endless use of the word ‘posh’. But that elite system comes with elaborate cultural norms of noblesse oblige. Now I’m not here to tell you that this greatly moderates the English class system. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t. What’s striking though is that what hazing exists in England is done against the cultural grain. It’s not institutionalised. And it’s decidedly on the decline.

Not so in US fraternities.

In light of this, I couldn’t help wonder about the techbros unabashed celebration of elitism. Perhaps it was modelled in fraternities. Again, I say this as an adherent to Robert Michel’s ‘iron law of oligarchy’. Elites necessarily emerge in all complex organisations. So it’s usually vain to imagine you can do without them. The important questions are the justice with which people gain elite status, the openness of elites to talented outsiders and the extent to which elites think their conduct as ultimately on behalf of others.

It seems these contrasts go back much further that you might think. The extract below is around a third of Chapter 5 of the above pictured book - which is excellent.

Slavery and Constitutionalism

During the heated debate in the Constitutional Convention over proportional representation in the upper house of the Congress, James Madison tried to suggest that the real division in the Convention was not between the large and small states but between the slaveholding and the non-slaveholding states. Yet every delegate sensed that this was a tactical feint, designed by Madison to get the Convention off the large–small state division that was undermining his desperate effort to establish proportional representation in both houses.

It was a shrewd move, since Madison knew that slavery was a major problem for the Convention. The American Revolution had made it a problem for all Americans. Although some conscience-stricken Quakers began criticizing the institution in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, it was the Revolution that galvanized and organized their efforts and produced the first major solution to that problem. In fact, the Revolution created the first antislavery movement in the history of the world. In 1775 the first antislavery convention known to humanity met in Philadelphia at the very time the Second Continental Congress was contemplating a break from Great Britain. The Revolution and antislavery were entwined and developed together...

Hereditary chattel slavery—one person owning the life and labor of another person and that person's progeny—is virtually incomprehensible to those living in the West today, even though as many as twenty-seven million people in the world may be presently enslaved...

Yet, as ubiquitous as slavery was in the ancient and pre-modern worlds, including the early Islamic world, there was nothing anywhere quite like the African plantation slavery that developed in the Americas. Between 1500 and the mid-nineteenth century, at least eleven or twelve million slaves were brought from Africa to the Americas. Much of the prosperity of the European colonies in the New World depended upon the labor of these millions of African slaves and their enslaved descendants. Slavery existed everywhere in the Americas, from the villages of French Canada to the sugar plantations of Portuguese Brazil.

Slavery in the British North American mainland differed greatly from the slavery in the rest of the New World. In the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the English mainland colonies imported three to four hundred thousand African slaves, a very small percentage of the millions that were brought to the Caribbean and South American colonies, where the mortality rates were horrendous. Far fewer slaves died prematurely in the North American mainland. In fact, by the late eighteenth century the slaves in most of the English mainland colonies were reproducing at the same rates as whites, already among the most fertile peoples in the Western world...

Because labor was so valuable in America, the colonists enacted numerous laws designed to control the movement of white servants and to prevent runaways. There was nothing in England resembling the passes required in all the colonies for traveling servants. As expensive labor, most colonial servants or their contracts could be bought and sold, rented out, seized for the debts of their masters, and conveyed in wills to heirs. Colonial servants often belonged to their masters in ways that English servants did not. They could not marry, buy or sell property, or leave their households without their master's permission. Those convicted of crimes were often bound over for one or more years to their victims who could use or sell their labor.

No wonder newly arriving Britons were astonished to see how ruthlessly Americans treated their white servants. "Generally speaking," said royal official William Eddis upon his introduction to Maryland society in 1769, "they groan beneath a burden worse than Egyptian bondage." Eddis even thought that black slaves were better treated than white servants. But in this cruel, premodern, pre-humanitarian world, better treatment of the lower orders was quite relative. Superiors took their often brutal and fierce treatment of inferiors as part of the nature of things and not something out of the ordinary—not in a society where the life of the lowly seemed cheap. Even the most liberal of masters could coolly and callously describe the savage punishments they inflicted on their black slaves. "I tumbled him into the Sellar," wrote Virginia planter Landon Carter in his diary, "and there had him tied Neck and heels all night and this morning had him stripped and tied up to a limb." But whites among the mean and lowly could be treated harshly too. In the 1770s a drunken and abusive white servant being taken to Virginia was horsewhipped, put in irons and thumb-screwed, and then handcuffed and gagged for a night; he remained handcuffed for at least nine days...

The Revolution changed everything: unfreedom could no longer be taken for granted as a normal part of a hierarchical society. Almost overnight black slavery and white servitude became conspicuous and reviled in ways that they had not been earlier. Under the pressure of the imperial debate the Revolutionaries tended to collapse the many degrees of dependency of the social hierarchy into two simple distinctions and thus brought into stark relief the anomalous nature of all dependencies. If a person wasn't free and independent, then he had to be a servant or slave. Since the radical Whig writers, from whom the colonists drew many of their ideas, tended to divide society into just two parts, the "Freemen," who in John Toland's words, were "men of property, or persons that are able to live of themselves," and the dependent, "those who cannot subsist in this independence, I call Servants," it was natural during the imperial crisis for the colonists to apply this same dichotomy to themselves. If they were to accept the Stamp Act and other parliamentary legislation, they would become dependent on English whims and thus become slaves.

Suddenly the debate between Great Britain and its colonies made any form of dependency equal to slavery. "What is a slave," asked a New Jersey writer in 1765, "but one who depends upon the will of another for the enjoyment of his life and property?" "Liberty," said Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, quoting the seventeenth-century radical Whig Algernon Sidney, "solely consists in an independency upon the will of another; and by the name of slave, we understand a man who can neither dispose of his person or goods, but enjoys all at the will of his master." If Americans did not resist the Stamp Act, said Hopkins, slaves were precisely what they would become. In 1775 John Adams drew the ultimate conclusion and posed the social dichotomy about as starkly as possible. "There are," said Adams simply, "but two sorts of men in the world, freemen and slaves."

This sharp dichotomy made white servitude impossible to sustain. If all dependencies, including servitude, were to be equated with slavery, then white male servants balked at their status and increasingly refused to enter into any indentures. They knew the difference between servitude and slavery. If they had to be servants, they wanted to be called "help," and they refused to call their employers "master" or "mistress." Instead, many substituted the term "boss," derived from the Dutch term for master. By 1775 in Philadelphia the proportion of the work force that was unfree—composed of servants and slaves—had already declined to 13 percent from the 40–50 percent that it had been at mid-century. By 1800 less than 2 percent of the city's labor force remained unfree. Before long, for all intents and purposes, indentured white servitude disappeared everywhere in America...

The rapid decline of servitude made black slavery more conspicuous than it had been before—its visibility heightened by its black racial character. Suddenly, the only unfree people in the society were black slaves, and for many, including many of the slaves themselves, this was an anomaly that had to be dealt with. However deeply rooted and however racially prejudiced white Americans were, slavery could not remain immune to challenge in this new world that was celebrating freedom and independency as never before.

Although everyone knew that eliminating slavery would be far more difficult than ridding the country of servitude, there were moments of optimism, even in the South. For the first time in American history the owning of slaves was put on the defensive. The colonists didn't need Dr. Samuel Johnson's jibe in 1775—"how come we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of Negroes?"—to remind them of the obvious contradiction between their libertarian rhetoric and their owning of slaves. "The Colonists are by the law of nature free born," declared James Otis of Massachusetts in his 1764 pamphlet, "as indeed all men are, white or black." Otis went on to challenge the owning of slaves and the practice of the slave trade and to point out that "those who barter away other men's liberty will soon care little for their own."

Not all Americans who criticized slavery were as frank and spirited as Otis, but everyone who thought himself enlightened became uneasy over slavery in his midst. Even some of the southern planters became troubled by their ownership of slaves. This was especially true in the colony of Virginia.

In 1766 a young Thomas Jefferson was elected to Virginia's House of Burgesses, where, as he says in his autobiography, he introduced a measure for the emancipation of slaves in the colony. His colleagues rejected the measure, but they did not reject Jefferson, who soon became one of the most important members of the legislature. By the time he wrote his instructions to the Virginia delegation to the First Continental Congress, immediately published as A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774), he openly voiced his opposition to the "infamous" slave trade and declared that "the abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in these colonies where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state."

Many of Jefferson's Virginia colleagues, equally uncomfortable with their slaveholding, were gradually coming to think differently about the future of the institution. They sensed that they had too many slaves already, and they thus became increasingly sympathetic to ending the despicable overseas slave trade. Tobacco had exhausted the soil, and many planters, including George Washington, had turned to growing wheat, which did not require the same human labor as tobacco production. Consequently, more and more slaveholders had begun hiring out their slaves to employers in Richmond and Norfolk. This suggested to many that slavery might eventually be replaced by wage labor. Some Virginians hoped that the impending break from Great Britain might allow them not only to end the slave trade but to end the colony's prohibition against manumissions...

All these developments in Virginia made the possibility of ending slavery seem increasingly realistic, which in turn led to the emergence of a growing number of antislavery societies in the Upper South—more even than in the North. If Virginians, dominating the North American colonies as they did, could conceive of an end to slavery, or least an end of the dreadful slave trade, then many other Americans could see the possibility of entering a new enlightened antislavery era—an era that would coincide with their break from Great Britain.

Nearly everywhere there was a mounting sense that slavery was on its last legs and was dying a natural death. On the eve of the Revolution Dr. Benjamin Rush of Pennsylvania believed that the desire to abolish the institution "prevails in our counsels and among the all ranks in every province." With opposition to slavery growing throughout the Atlantic world, he predicted in 1774 that "there will be not a Negro slave in North America in 40 years."

Rush and the many others who made the same predictions could not, of course, have been more wrong. They lived with illusions, illusions fed by the anti-slave sentiments spreading in Virginia and elsewhere in the northern colonies. Far from dying, slavery was on the verge of its greatest expansion. There were more slaves in the United States at the end of the Revolutionary era than at the beginning.

Because Virginia possessed two hundred thousand slaves, over 40 percent of the nearly five hundred thousand African American slaves who existed in all the North American colonies, its influence dominated and skewed the attitudes of many other colonists. Farther south, there was another, much harsher reality.

Both South Carolina, with about seventy-five thousand slaves, and Georgia, with about twenty thousand, had no sense whatsoever of having too many slaves. For them slavery seemed to be just getting underway. Planters in these deep southern states had no interest whatsoever in manumitting their slaves and in fact were eager to expand the overseas importation of slaves. If only other Americans paid attention, they would have realized that the Carolinians and Georgians would brook no outside interference with their property in slaves. Washington knew this, which is why he claimed that South Carolina and Georgia were the only really "Southern states" in the Union. Virginia, he said, was not part of the South at all, but was one of "the middle states," not all that different from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York...

The Continental Congress, which met in 1774, urged the colonies to abolish the slave trade. Jefferson believed that the British Crown was responsible for the slave trade, but in drafting the Declaration of Independence he discovered that blaming George III for its horrors was too much for his colleagues in the Congress. South Carolina and Georgia objected to the accusation, he later explained, and even some northern delegates were "a little tender" on the issue, "for though their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers."

With independence, nearly all the newly independent states, including Virginia, began moving against slavery, initiating what became the first great antislavery movement in world history. The desire to abolish slavery was not an incidental offshoot of the Revolution; it was not an unintended consequence of the contagion of liberty. It was part and parcel of the many enlightened reforms that were integral to the republican revolutions taking place in the new states. The abolition of slavery was as important as the other major reforms the states undertook: their disestablishment of the Church of England, their plans for public education, their changes in the laws of inheritance, and their codification of the common law, and their transformation of criminal punishment.

Of course, many of these enlightened plans and hopes went unfulfilled or were postponed for later generations to accomplish; that was certainly the fate of the many elaborate plans for creating systems of public education. But despite flying in the face of the rights of property that were sacred to the ideology of the Revolution, the abolition of slavery was remarkably successful, at least in the northern states...

As early as 1774 Rhode Island and Connecticut ended the importation of African slaves into their colonies. In the preamble to their law the Rhode Islanders declared that since "the inhabitants of America are generally engaged in the preservations of their own rights and liberties, among which that of personal freedom must be considered the greatest," it was obvious that "those who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves should be willing to extend personal liberty to others." Other states—Delaware, Virginia, Maryland, and South Carolina—soon followed in abolishing the slave trade; South Carolina, however, only for a term of years.

With independence Americans began attacking slavery itself. In 1777 the people of Vermont, in hopes of soon joining the new United States as the fourteenth state, drew up a constitution. The first article of that constitution stated that because all men were "born equally free and independent," and possessed "certain natural, inherent, and unalienable rights, . . . therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave, or apprentice, after he arrives to the age of twenty-one years; nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years, unless they are bound by their own consent."

This article of the Vermont constitution linked the abolition of slavery to the enlightened ideals of the Revolution as explicitly and as closely as one could imagine. It also revealed how Americans thought about slavery in relation to other forms of unfreedom existing in colonial America. Although the article was not rigidly enforced, and slavery and other forms of unfreedom continued to linger on in Vermont, it nevertheless represented a remarkable moment in the history of the New World...

By the early nineteenth century all the northern states had provided for the eventual end of slavery, and Congress had promised the creation of free states in the Northwest Territory. By 1790s the number of free blacks in the northern states had increased from several hundred in the 1770s to over twenty-seven thousand. By 1810 there were well over one hundred thousand free blacks in the North. For a moment it looked as the institution of slavery might be rolled back everywhere...

By the early decades of the nineteenth century the two sections of North and South may have been both very American and very republican, both spouting a similar rhetoric of liberty and equal rights, but below the surface they were fast becoming very different places, with different economies, different cultures, and different ideals—the northern middle-class-dominated society coming to value common manual labor as a supreme human activity, the southern planter-dominated society continuing to think of labor in traditional terms as mean and despicable and fit only for slaves...

Yet that northern middle-class society had little or no grounds for celebrating its progressiveness in opposing slavery. The freedom that the North's black slaves earned in the decades following the Revolution came with some perverse consequences. Freedom for black slaves did not give them equality. Indeed, emancipation aggravated racial bigotry and inequality. As long as slavery determined the status of blacks, whites did not have think about racial discrimination and racial equality. But once black slaves were freed, race became the principal determinant of their status. Republicanism implied equal citizenship, but unfortunately, few white Americans in the post-Revolutionary decades were prepared to grant equal rights to freed blacks. Consequently, racial prejudice and racial segregation spread everywhere in the new Republic. In 1829 William Lloyd Garrison believed that "the prejudices of the north are stronger than those of the south."...

Despite this resultant racial segregation and exclusion and despite the often sluggish and uneven character of the abolition in the North, we should not lose sight of the immensity of what the Revolution accomplished. For the first time in the slaveholding societies of the New World, the institution of slavery was constitutionally challenged and abolished in the northern states. It was one thing for the imperial legislatures of France and Britain to abolish slavery as they did in 1794 and 1833 in their far-off slave-ridden Caribbean colonies; but it was quite another for slaveholding states themselves to abolish the institution. For all of its faults and failures, the abolition of slavery in the northern states in the post-Revolutionary years pointed the way toward the eventual elimination of the institution throughout not just the United States but the whole of the New World.

Mildly laughs at the Scott Alexander but just because humans are not rational by definition LLMs that are trained on humans being irrational are not going to be rational either. It does not change that LLM users in the corporate world are encouraged to think that they can get the moon and are not using the discipline to think about projects which use what the technology is capable of doing better than humans now.

(I essentially did know all that as far as the Gordon Wood inasmuch as no historian that I read who focused on the formal politics of the Revolutionary era contradicted him.)