Unaccountability one day, autocracy the next

And other things you'd be very ill-advised to ignore

Towards American autocracy

In case it wasn’t obvious to you that a second Trump term would be a fair bit scarier than the first. It will be.

[O]ther countries’ recent experiences suggest that a political movement with autocratic tendencies will become more ruthless and effective a second time around – especially after an electoral defeat.

Here’s how it tends to play out: A first-time leader or a new party gains national power, only to suffer a bitter electoral defeat after a single term. This experience has a radicalizing effect, and the party or leader becomes determined never to lose again. When the party does win a second time, it quickly moves to destroy the institutions and rules that could threaten its hold on power.

Exhibit A is Viktor Orbán, whose Fidesz party has governed Hungary twice. The first time, between 1998 and 2002, Orbán generally operated as a conventional economic conservative. Though he bridled a bit at democratic norms, he never drifted outside the European mainstream. But after losing in 2002, Fidesz spent eight years in opposition. When Orbán returned to power in 2010, he was determined never to be defeated again. By gerrymandering the legislature, changing voter-eligibility rules, and capturing the election commission, courts, and state media, he made it practically impossible for the opposition to win.

A similar story played out in Poland under its Law and Justice (PiS) government. Founded by twin brothers Jarosław and Lech Kaczyński, PiS first held power between 2005 and 2007, when it was part of a coalition and focused on economic inequality and traditional Catholic values. But after the party’s ouster from government in 2007, and Lech’s death in a plane crash in Russia in 2010, Jarosław began railing against real and imagined foes. When PiS won an outright parliamentary majority in 2015, it shifted its focus to dismantling Poland’s democratic institutions. … But unlike Fidesz, PiS’s efforts to tilt the electoral playing field weren’t enough. It lost power in October 2023 to a coalition of pro-European, pro-democracy parties.

Finally, consider India’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). …

The common element in these three cases is a charismatic leader who comes to reject the idea that his opponents can ever be trusted with power. Defeat is the midwife of anti-democratic ire. When an autocratic movement gains control of the state’s machinery a second time, inexperience no longer impedes it from attacking institutions directly.

The parallels between these cases and Trump’s MAGA movement should be obvious. Like the transformed BJP, PiS, and Fidesz, today’s Republican Party represents a sharp break from its own recent past. As American parties have often done, it underwent a profound metamorphosis. …As with Fidesz, PiS, and the BJP, MAGA was a novice movement in 2016. … Beyond Trump, allied institutions, such as the Heritage Foundation with its Project 2025 blueprint, are far more prepared than they were in January 2017. …

The movement’s admiration for Orbán is emblematic of this trend. Trump’s running mate, J.D. Vance, right-wing luminaries like Tucker Carlson and Steve Bannon, and the Conservative Political Action Conference (which convened in Budapest in 2022) all hail Orbán as the vanguard for an insurgent global illiberalism.The Republican Party has already advanced a long way down the path taken in Hungary, Poland, and India. Whatever Trump’s personal limitations, he now leads a movement with ample talent and experience. Having learned from that experience, and from similar movements elsewhere, another Trump administration would be far more effective at wielding – and maintaining – power.

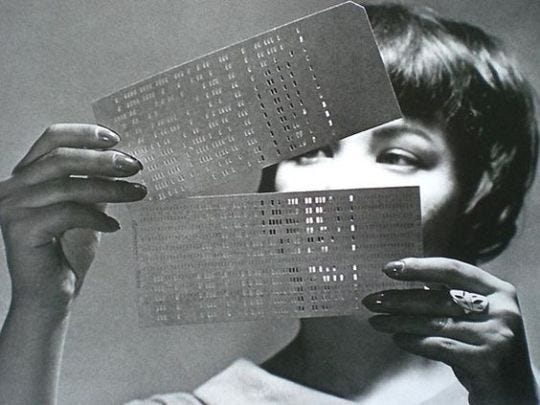

Habermas machines

As we hurtle towards our post-humanity some will find these ideas dystopian. They remind me of ‘bridging algorithms’ on social media about which I’ve pontificated. I think they hold much promise so maybe Habermas machines do too. I included the article up to the point where it’s dystopianism starts outweighing its good points. That is where it suggests that the software wouldn’t be used to bring about greater actual consensus. It would spare us the hard work of reaching it and just build it virtually in the cloud.

Achieving consensus can be hard, so wouldn’t it be nice if a machine could produce it as a kind of consumption good? Instead of having to work through differences and emotions collectively and collaboratively, each individual could articulate their position and their critiques alone and then a model could sort out what the underlying average position of all the participants in a “discussion” should be understood to be. Everyone can treat the machine as an unbiased witness and agree with it without seeming to have to agree with each other. No one’s ego would be bruised by any other ego; no wills would clash. Everyone could automate their civic duty without having to undergo the hardship of confronting other citizens or empathizing with them; instead their beliefs become disembodied abstractions, statistical constructs rather than liven experiences. Political deliberation could become a matter of everyone preaching their views into a phone and waiting for an opinion calculator to decide the state of the public sphere. And the phone, in turn, could in the meantime barrage users with statements optimized to moderate and normalize their views so that dissensus is smoothed away at scale.

Researchers from Google recently issued a paper describing what they call a “Habermas machine,” a LLM meant to help “small groups find common ground while discussing divisive political issues” by iterating “group statements that were based on the personal opinions and critiques from individual users, with the goal of maximizing group approval ratings.” Participants in their study “consistently preferred” the machine-generated statements to those produced by humans in the group and helped reduce the diversity of opinion within the group, which researchers interpret as “AI … finding common ground among dicussants with diverse views.” So much for the “lifeworld” and “intersubjective recognition.” It appears that people are more likely to agree with a position when it appears that no one really holds it than to agree with a position articulated by another person. It’s sort of like Žižek’s idea of the Big Other in reverse.

The researchers suggest that their experiment reveals that LLMs can “facilitate collective deliberation that is time-efficient, fair, and scalable,” even though it also lacks “the mediation-relevant capacities of fact-checking, staying on topic, or moderating the discourse.” If the deliberation happens quickly and at scale, does it really matter if it is factual or pertinent? Speed and scale are their own justification, and what is factual and pertinent can be freely adapted to those requirements, so that what groups deliberate on are questions that are most expedient for an LLM to handle. …

Efforts to automate the public sphere remind me of Hiroki Azuma’s 2011 book General Will 2.0, which argues for using broad surveillance to calculate the general will of a populace mathematically and dispense with the need for deliberative politics. “These are times when everyone is constantly bothered by ‘others with whom a point of compromise can’t be sounded out,” he argues, so we should dispense with Habermas’s and Arendt’s presumption that politics require consensus building through discussion. Instead, politics should be automated by aggregating data on everyone’s behavior and transforming that into political positions and decisions.

Since the ideals of an Arendtian, Habermasian public sphere are impossible to establish, doesn’t it make more sense to take our current social situation and technological conditions as our premise and discuss designs — the architecture —for bringing about a space that is “something like a public sphere”?

That sounds like a description of the Habermas Machine, something that resembles a public sphere but is actually software architecture, where interpersonal communication is replaced with information processing disguised as natural language.

Azuma draws on a reading of Rousseau’s The Social Contract to conclude that he “denies the necessity of citizens discussing or coordinating their views” and that the “general will” emerges more precisely when they don’t, since “long debates, dissensions, disturbances, signal the ascendancy of particular interests and the decline of the State.” If we follow Rousseau, according to Azuma, “communication should be banished from politics to allow the general will to be formed.” Maybe the Habermas Machine should have been called the Rousseau Machine.

And so on.

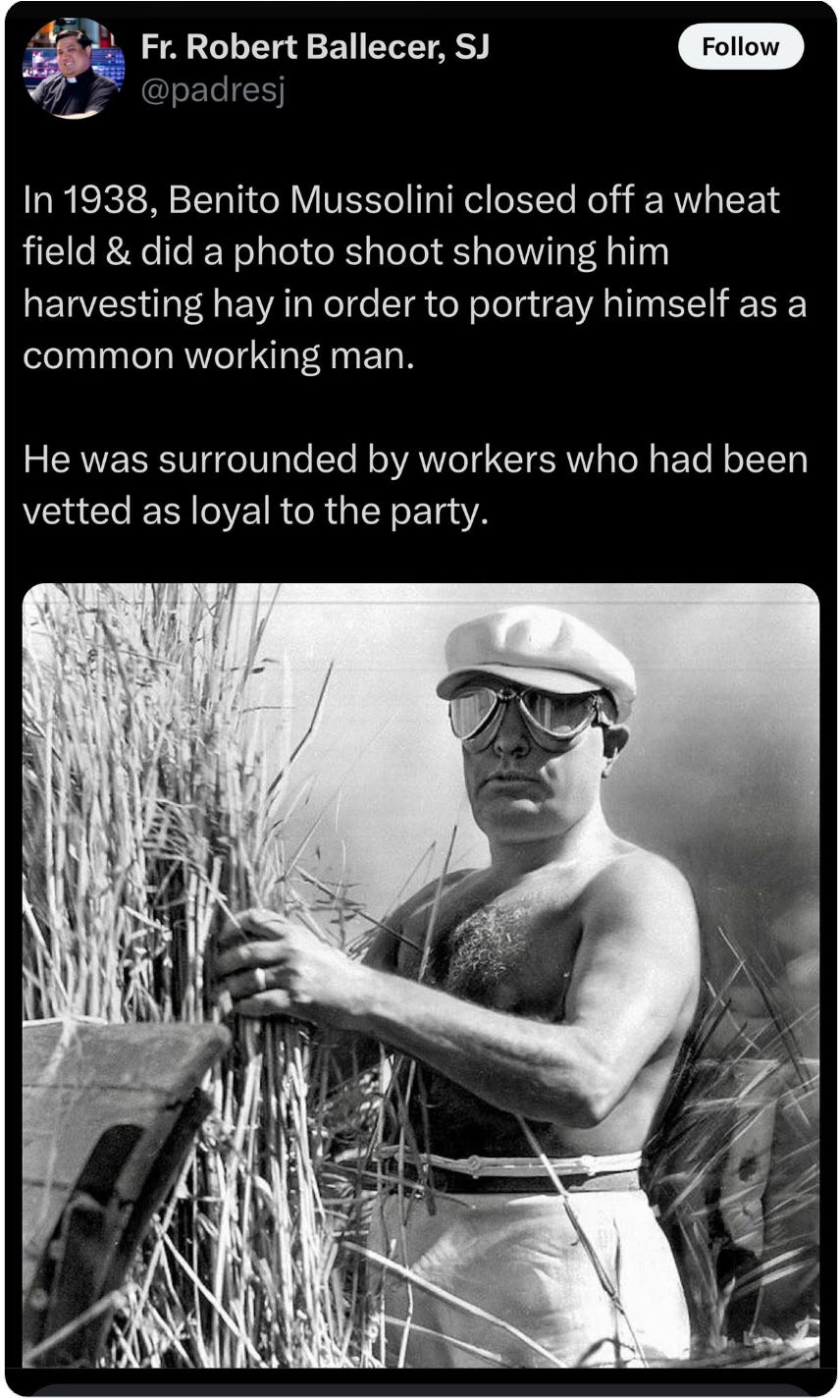

A photoshoot to make Italy Great Again

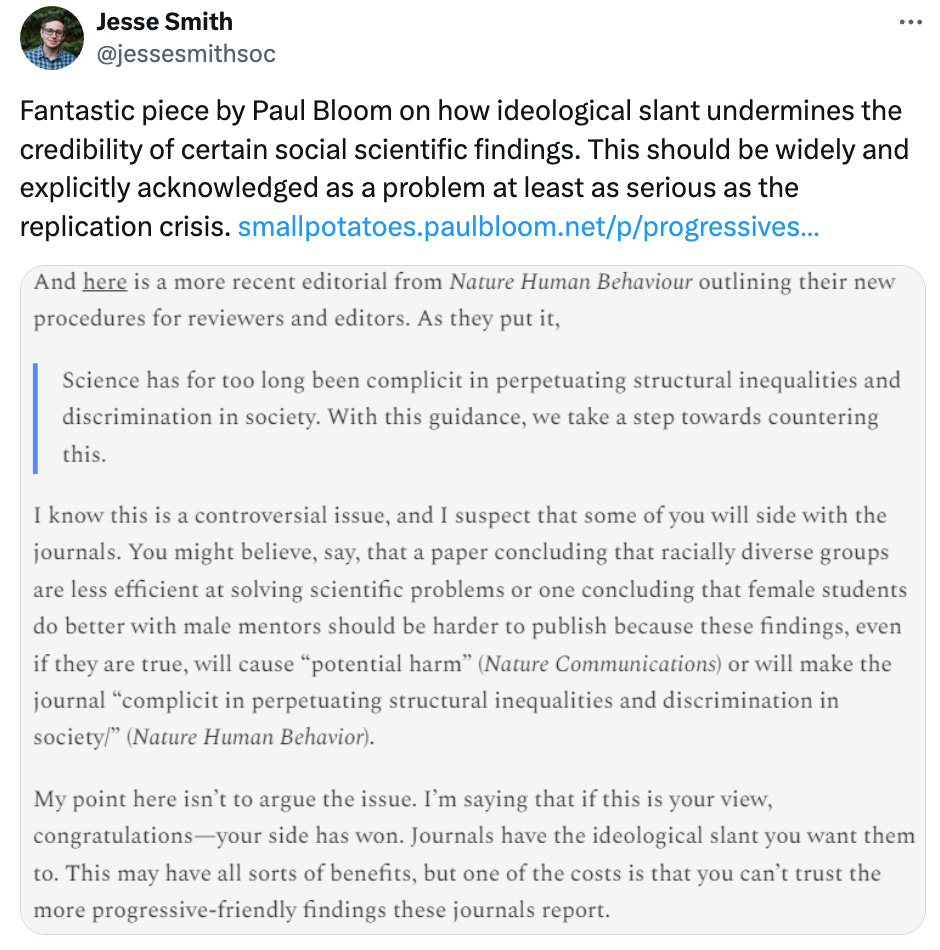

When polarisation engulfs the elites who can you trust?

As Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, electoral democracy depended on an elite political class which, though it was divided into ideological factions, was nevertheless committed to basic democratic norms across the aisle. So what if that consensus breaks down. That process seems well advanced in the US.

Machiavelli used to say that the Prince didn’t need to worry about il popolo — the ordinary folk. They just wanted to lead their quiet lives. If you governed well they’d be grateful. They wouldn’t give you any trouble. The elites on the other hand — i grandi — were different. There his message was different. Be afraid. Be very afraid. I grandi were insatiable. It’s something to ponder when one thinks of certain particularly well placed grandi — people like current Republican nominated US Supreme Court judges, Rupert Murdoch, Elon Musk and Peter Thiel.

There is a way round this huge problem. Let those ordinary folk defend democratic norms. But the institutions have to be right to do so. Ordinary folk don’t defend basic democratic norms when they’re having their say about who should be government. But they do in other circumstances.

Turns out, as demonstrated in this 2021 article, done right we can build bottom-up defence of the democratic norms that must be defended if government of the people, by the people for the people is not to perish from the earth. You just select some ordinary folks by lottery and ask them to — well — defend democracy — as ordinary folk have been doing on the Michigan Independent Citizens' Redistricting Commission since 2018.

American voters are largely united in their opposition to partisan gerrymandering, according to recent polling conducted ahead of the upcoming once-per-decade redrawing of state voting maps.

Nearly 9 in 10 voters oppose the use of redistricting in a manner that aims to help one political party or certain politicians win an election, the nonprofit anti-corruption group RepresentUs found.

“Partisan gerrymandering is one of the most nefarious forms of political corruption, disenfranchising millions of Republicans, Democrats and independents,” Josh Silver, CEO of RepresentUs, said in a statement. “It’s not hard to see why nearly everyone wants to see this practice banned once and for all.”

The findings come ahead of the Census Bureau’s scheduled Aug. 16 release of map data that will inform how states redraw their congressional districts, a process that some experts warn will be rife with partisanship.

A new study by the liberal nonprofit Brennan Center listed four states — Georgia, Florida, North Carolina and Texas — as possessing the highest risk of extreme gerrymandering, the process by which politicians redraw voting districts in a way to maximize their party’s electoral advantage and dilute their opposing party’s voting power.

Those states could draw anywhere from six to 13 new congressional districts that heavily favor GOP candidates — which would be enough for Republicans to retake the House in 2022, according to findings from the Democratic data firm TargetSmart that were first reported by the progressive outlet Mother Jones.

Strikingly, the RepresentUs poll on partisan gerrymandering found little variation among voters who backed former President Trump, with 88 percent saying they oppose the practice and 92 percent of Biden voters saying the same.

The findings were fairly consistent with other polling that has shown bipartisan opposition to gerrymandering and support for independent redistricting commissions. An April poll by AP-NORC found that 74 percent of Democrats, 60 percent of Republicans and 63 percent of independents believe gerrymandering is “a major problem.”

A Democratic-backed proposal in Congress, the For the People Act, would ban partisan gerrymandering, but is unlikely to garner enough support from Senate Republicans to overcome a GOP filibuster.

Meanwhile on the unaccountability front …

HT: Collegue, friend and subscriber Gene Tunny.

A stunner!

You should subscribe to Crikey!

As David Shoebridge highlights points out in the video above, the NACC was the product of serious politicians — not the flakes that just want a headline. Serious politicians in ‘parties of government’.

The National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), founded in July 2023, has not had an auspicious beginning. … [T]he NACC’s investigations have been mired in secrecy ever since. Communications have been sparse, and against the advice of most transparency experts and advocates, Labor legislated a NACC (with Coalition support) that wouldn’t hold public hearings unless in exceptional circumstances.

So far there have been no such circumstances, and the public has been left to guess what the NACC has been investigating. The NACC has received more than 3,000 referrals as of June, has so far spent more than $100 million, and has announced no significant corruption findings.

It was hoped an investigation report released earlier this month by the NACC, titled “Operation Bannister”, would expose a scandal that had been festering for some time: the awarding in 2017 of massive Home Affairs contracts, for Manus Island detention services, to Paladin — a security group with few staff or assets, an opaque company structure, and no track record of delivering contracts on anything like this scale.

Paladin’s Australian “office” was a beach shack on Kangaroo Island, its Singapore parent company ran out of a PO Box, and its Papua New Guinea offshoot hadn’t filed any financial returns in its first six years of operation in 2010-16.

The report, signed by NACC commissioner Paul Brereton, promised to look into “whether a Home Affairs employee had been involved in corrupt conduct through familial links with a contracted service

provider, Paladin Holdings”. It was provided to the Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus in January.The reason for its delay, or indeed for the timing of its release last week, is unclear, but it was implicitly acknowledged thus: “Home Affairs’ engagement of Paladin Holdings has been the subject of media attention and this public report will assist in ‘clearing the air’ in relation to this aspect of the engagement.”

Readers, it did not clear the air. In fact, this case study points to how fundamentally damaging the lack of transparency around these reports can be, both for the public and potentially the people investigated.

The investigation regarded large undeclared payments by Paladin to a former Home Affairs executive, Anne Brown (a pseudonym), who was “a close relative” of one of Paladin’s directors, Craig Thrupp. Palidin made these payments, initially totalling $215,368.50, between May and July 2017, while Brown was employed by Home Affairs and a month before Paladin became the sole bidder in a closed tender process. The contracts that Paladin won, after preparing its bid in a single week, were worth $229.5 million, and would eventually be extended to be worth $532 million.

The NACC report concludes that it did not uncover evidence of corrupt conduct.

Insofar as Brown is concerned, the NACC investigation found she did not abuse her office as a Home Affairs employee to dishonestly obtain a benefit for herself or to assist Paladin in securing the garrison services contracts. The report noted there was no evidence that Brown had any knowledge that would assist Paladin in the tender, was in any position to influence decision-making, or had any involvement whatsoever in it.

But here it is salient to mention something that the NACC report avoids: “Anne Brown” is Craig Thrupp’s mum. As the Nine papers reported in July last year, “The majority owner of the company that ran Manus Island’s immigration detention centre insists he was only trying to help his mother, who works in the Home Affairs Department, when he transferred more than $1.2 million to her in a series of payments.”

Asked by Nine how much he or Paladin had paid, Thrupp said: “I did not ‘pay’ my mother anything — I did transfer her some amounts as an individual — I am her son and I was supporting my mother.”

The NACC investigation looked at this one small aspect, one of many troubling issues raised by the Paladin contracts, and declared this particular allegation unsubstantiated. We have no reason to dispute this finding.

But if this report is anything to go by, the public should be prepared for disappointment about the functioning of the NACC: the fundamental lack of transparency built into the reporting of this investigation raises more questions than it answers.

Of the Paladin payments made to Anne Brown via PayPal, $191,800 were invoiced for “management and consulting services”. However, these invoices were not generated by her, nor were there records of services ostensibly provided. Anne Brown’s partner, “Carl Delaney” (also a pseudonym), with whom she was living at the time, was a former Home Affairs executive (retired in 2013) who “guided Paladin through the tender and procurement process”, according to the NACC report. Delaney was paid a performance bonus for his services and joined Paladin’s board in May 2019.

In May 2018, Thrupp also “funded the purchase” of a three-bedroom unit for $920,000 in the names of Brown and Delaney. Soon they were renting it back to Paladin for $1,000 a week, and when they sold it in 2020, they kept the proceeds.

Margo Kingston reflecting on her locking-on for nature

This is the conclusion to her article, the rest of which is the story of her experience locking-on to prevent logging of a forrest near her.

I reluctantly decided to lock-on last week when there was no one else to, because the cause was urgent. Each day’s lock-on delays destruction of a haven for the officially endangered greater gliders. Forestry Corp’s “compliance officers” had surveyed for them by day but the marsupials only begin emerging from their tree dens at dusk. Citizen scientists, including former Treasury secretary Ken Henry, who now runs an “accounting for nature” project, spotlight regularly, documenting many glider dens that mean Forestry Corp is required by law to add them to logging exemption zones.

It seems senseless to me for the NSW government, which owns Forestry Corp, to log public forests at a loss, despite the risks to water catchments and habitat for endangered species, especially after their devastation in the 2019 bushfires. This is without mentioning climate change. At the end, these precious trees become native woodchips for suburban gardens, firewood, pallets and a few high-end hardwood boards.

The politics of this is stuck. The Nationals back the timber mills and contractors and the CFMEU won’t let Labor stop it. It seems so easy to fix – make state forests carbon offset areas, earning money for the state; buy out the logging contracts and offer employees and local contractors generous severance packages and retraining.

No one in power is proposing this. …

Still in shock the next day, I suddenly realised why I had done it. Susie Russell has fought for decades to protect NSW native forests. It’s her life’s passion. Along with my mother, she saved me when I broke down physically and mentally after The Sydney Morning Herald rejected my work in 2005. Susie also showed me how to see and appreciate nature and I think of her house on the Bulga plateau as my second home.

My father told me that if you have one true friend, you’re fine. If you have two, you’re lucky. Three and you’re blessed. I’m proud that I’ve proved to myself that I’m a true friend of a true friend. I’m relieved this 65-year-old childless dog lady didn’t break when she did something outside her comfort zone for younger generations, and didn’t just report others doing it.

Maybe clarity and empowerment take a while.

Dignity, humility

Crikey! on Trump’s next insurrection

Did I mention you should subscribe?

More on the next insurrection if it comes to that. Crikey! complains it’s not covered sufficiently boldly, unambiguously in the media. That’s right. I sympathise, the ‘he-said-she-said” instinct works like a gravitational force.

Still even if they did this it wouldn’t matter much. Anyone who wants to know does.

Donald Trump and the billionaires around him are preparing, again, to steal the presidential election. The US political media, meanwhile, are approaching it with the same “nothing to see here” confidence they took to their fumbled reporting of Trump’s last attempted coup.

The result is a “sane-washing” of Donald Trump’s coup-planning; planning that is happening right in front of us. Discredit the vote in advance, claim victory early, disrupt the count to block the Electoral College (particularly in close swing states), lean into the power of right-wing media and public disorder, and exploit enough of the constitutional vagaries to have Trump declared elected.

Even the release over the weekend of 1,889 pages of heavily redacted evidence related to the ongoing criminal prosecution of Trump for illegally seeking to overturn the 2020 election didn’t shake up traditional media’s reluctance to see what’s right in front of them. Donald Trump is doing it again — this time with the active backing of the billionaire class, led by Elon Musk.

Step one in the would-be autocrat’s playbook for overturning an election? Undermine its legitimacy. Just look at how Department of Justice special counsel Jack Smith described Trump’s actions in this month’s criminal indictment:

Although his multiple conspiracies begin after election day in 2020, the defendant laid the groundwork for his crimes well before then … In the months leading up to the election, he refused to say whether he would accept the election results, [and] insisted he could lose the election only because of fraud.

A serious news outlet would use this warning to point at the current Trump campaign with a big red arrow that reads: “We are here.”

Last time around, Politico, the Washington press corp’s in-house journal, poked at the Republican nominee’s then-odd claims to ask: “What if Trump won’t accept 2020 defeat?” But it then disregarded its question with a head-shakingly sage “the scenarios all seem far-fetched”.

It was only in the dying days of that year’s campaign that Barton Gellman in The Atlantic took a serious look and discovered that “Trump’s state and national legal teams are already laying the groundwork for postelection maneuvers that would circumvent the results of the vote count in battleground states”.

Then once the voting was done, Fox News swung into gear to promote the stolen election narrative.

This time around, according to Trump and his surrogates, it’s illegal migrants who are fraudulently tilting the vote to Democrats. As he said in last month’s presidential debate: “Our elections are bad, and a lot of these illegal immigrants coming in, they’re trying to get them to vote.” …

They struggle to hear when the right speaks out of both sides of its mouth — one side dog-whistling to the base, and the other to traditional media, dismissing the Republican nominee’s anti-democratic claims as just ”Trump being Trump”. But as leading economics blogger Brad DeLong wrote in his Substack newsletter Grasping Reality this week: “You have to recognize that the players of these games [do] not intend any single one of these meanings. They intend them all.”

Instead, political media (yes, here in Australia, too) only hears what it wants to hear, relying on the comfort of the belief that the insider winking is just politics, comforted by a “too far-fetched to be true” mantra.

Will it work? Who knows. But a news media that has already lived through one test-run should be more aware of the signs of a repeat.

By Vectron

Dean Ashenden on education, social mobility and mass gaslighting

In a recent Inside Story, Dean Ashenden reviews two books. One a monumental 7 year study of social mobility that, at least judging from his review doesn’t tell us anything much we don’t know. The other book probably doesn’t tell us anything we don’t know either, but its content was more countercultural — which meant that it hit home more for me. Another cry from the heart — well summarised.

In another new book, Exam Nation, schooling moves up from supporting cast to lead role. Sammy Wright is much less concerned with the access schools do or don’t provide to Oxbridge and/or the elite than with what the pursuit of access in the name of social mobility and equality is doing to schooling.

“The ranking and sorting of pupils… is not just an unfortunate but unavoidable by-product of school,” he argues, “it is the guiding principle.” What has long been the case has in recent years been taken to new levels by “reforms” that have ramped up competition between students and between schools. It’s not just unfair; it pushes students into deeply unrewarding study and pushes teachers and schools to work with the kids in bad faith.

There’s a kind of mass gaslighting going on, Wright says. “We tell kids to try their hardest, and that they can do it, and only afterwards do we admit that we only meant that for the top sets [classes].” And it’s warped the whole idea of school and education: “A competitive, marketised view of school, a transactional mindset exemplified by the prioritisation and proliferation of grades and the meritocratic ranking they feed has eaten away at the basic moral purpose of education.”

Can that purpose can be recovered? Wright is a teacher of many years’ standing, albeit not a typical one — he’s the son of an Oxford academic and an Oxford graduate himself, and was for a time a member of that peculiar institution the Social Mobility Commission (along with Born to Rule’s Sam Friedman). But when it comes to finding out whether and how the moral purpose of education might be recovered he thinks like a teacher not an academic. He takes a year off and talks to people, lots of them, students, teachers and others in an assortment of twenty schools dotted around England as well as to some of those “well-meaning people” who work in various branches of schooling’s HQ. He reads and writes and thinks as well as talks and listens, trying to find a way through the teeming complexity of it all.

“Every single type of school we have developed over [a] long history is still with us” he says. “The landscape of education today is like the landscape of our cities: ancient monument cheek-by-jowl with shining modernist towers, palatial mock-Tudor just streets away from cramped brick terraces.” And no school is an island, entire of itself; all are organised, in various ways by various agencies and above all by competition that pits these many kinds of schools against each other, with hugely complex consequences.

Wright never quite fights his way up to the clear air above the fog of detail. “If I’m honest,” he says at the end of it all, “in writing this book I have found myself caught up in a kind of dizzying paralysis. Every time I think I see something clearly, my focus shifts and it seems to be part of a bigger pattern…” Eventually, after a wealth of musings, penetrating insights, telling observations and revealing anecdotes he concludes that what England really needs is a better way of thinking about school.

Wright’s better way comes in the form of five “narratives” or principles: education is not a marketplace; school is at the heart of a community; knowledge is for everyone; school is for everyone; measurement is about improvement, not ranking. Yes, and yes again! But what is to be done? By whom? How? Wright has arrived via a different route at a point adjacent to Reeves and Friedman, intuiting that what’s really needed is a different set-up altogether, but not knowing whether or how it can be got, or even if he dares to say so.

Nice looking Van Gogh fake

David Goodhart’s latest on upshot of feminism’s success

David Goodhart is a very accomplished journalist who founded Prospect Magazine which is still plugging along. He was one of the early critics of woke and lost plenty of friends on the left for it, but as much as I agree with him on that, I hope you agree, he’s got a much broader vision than that. He is in the process of publishing the third of three books the first two of which were The Road to Somewhere which coined the expression ‘somehwheres’ and ‘anywheres’ and Head Hand Heart: which bemoaned the way in which work of the hands and the heart was increasingly downgraded in prestige and pay compared with work with the ‘head’ — which needn’t involve high levels of intelligence, it just needs to be done primarily with a word processor.

When I was over in the UK this time last year (I’m about to depart on my annual pilgrimage to Kilkenomics again), he was hard at work on a book that is just hitting the stands. Here’s a piece he did on it for the Sunday Times. It’s a fine piece about a very important and sorely neglected issue.

Compared with 60 years ago, you are richer, better educated and freer to choose your life course, especially if you are a woman. But you are also more likely to live alone, to suffer from depression, less likely to have children and, if you are a child, much less likely to live in a stable family.

Enormous changes to family life lie behind much of this transformation. And the changes have often created a tension between women’s equality and proper care for the dependent young and old. The challenge we face now is how to reduce that tension not by pushing back against equality but by raising the status and value of the traditionally female realms of care.

Consider it an investment problem: how can we invest enough in the things we say we still want—having and caring for children, and decent care for

the disabled and the growing army of the elderly—while maximising choice, including the choice not to care? This is the care dilemma.

Women’s autonomy and financial independence is the biggest step forward in freedom in developed countries since 1945. But along with a more general relaxation of constraints on individual behaviour it has had unintended consequences for family life and the care economy.

There are four big ones—the rising cost of the social state thanks to smaller and less stable families; the mental fragility epidemic among young people; the rapidly falling birth rate; and the recruitment crisis in face-to-face care jobs, thanks to the low status of emotional labour.

These negative trends are inseparable from positive ones, such as the greater freedom to leave broken relationships, the mass movement of women into jobs and careers, and the expansion of state and market support for care.

There is no ‘golden age’ of family to restore, but few people welcome the fact that by their early teens nearly half of children in the UK, and mainly poorer ones, no longer live with both biological parents. We are the family breakdown champions of Europe. Moreover, many of us regret the fact that recent family policy focuses on helping both parents to spend more time at work, despite polling consistently showing that young parents would prefer more time at home if they could afford it.

This issue exposes one of the biggest divergences between the priorities of the political class and the mainstream. The last UK Government (with cross-party support) expanded state subsidy for formal childcare to infants as young as nine months, at a cost of £4 billion a year – a policy that is especially valuable to the one third of families with pre-school children in which both parents work full-time. Yet this arrangement is backed by less than 10% of the public, finds the British Social Attitudes survey. Moreover, many experts think most infants are better cared for at home before the age of two.

We have prioritised paid work and somewhat arbitrary measures of GDP over well-being, prompted by the UK Treasury’s jobs-driven growth model. But we have not accounted for the loss of work that was being done by women in the family and community in the old breadwinner–homemaker economy.

Household income has risen, but it is too often accompanied by overstretched lives. Moreover, the movement of women into the GDP workforce, from around 25% in the late 1950s to over 70% by the late 1990s provided a one-off boost to GDP that exaggerates the growth story of those decades. One worker became three, as both parents worked and needed a paid carer for their child.

The UK employment rate of 75% is already high by international standards and many countries with lower rates have higher growth and productivity. Growth should not depend on pushing often reluctant mothers into low productivity jobs but should come instead through removing barriers to building and investment.

The Treasury model maximises workforce, GDP and tax income today, but only by making it harder for families to create and raise the workers of the future. The fertility rate of below 1.5 children per woman today—we need 2.1 to keep the population stable—means far fewer workers and less tax income to support the battalions of the retired in 30 years, without ever higher levels of unpopular immigration or gradually turning the ‘right to die’ into a ‘duty to die’.

Few people want to return to the breadwinner–homemaker model,

which was, in any case, a historical anomaly. Escaping the pressures of home life into more socially esteemed paid work is a relief for many mothers, and financial autonomy has become all too necessary thanks to the decline of stable relationships (most British children are now born to unmarried mothers).

Support for the family and for higher fertility are often seen as conservative ideas but allowing women to more easily combine motherhood and work and helping to reduce family instability and child poverty, exacerbated by the UK’s uniquely child-unfriendly policy regime, are surely ideas that liberals and conservatives can unite around.

This is not an argument between today and the 1950s. Rather it is an argument between those I call the care egalitarians, and their counterparts, the care balancers. Egalitarians believe that men and women are not only equal but fully interchangeable. They believe, despite the evidence, that family structure is largely irrelevant to life chances, that the falling birth rate doesn’t matter, and that the gender division of labour is an anachronism. Balancers, on the other hand, embrace equality but worry about the consequences – for women, men and especially children – of unstable family life, regret the shrinking family, and want to reform rather than abolish the gender division of labour.

As Anne-Marie Slaughter, former adviser to Hillary Clinton, puts it: ‘My generation of feminists was raised to think the competitive work our fathers did was much more important than the caring work our mothers did… Women first had to gain power and independence by emulating men, but as we attain that power we must not automatically accept the traditional man’s view, actually the view of a minority of men, about what matters.’

If a patriarchal society is one that undervalues the role and contribution

of women, then the patriarchy is alive and well in the meagre pay

packets of social care staff, the emptying maternity wards and the one year old

child clinging desperately to its parent as it is dropped off for a long

day at nursery.

We do, of course, still care. The rhetoric of care is ubiquitous. The social state is far bigger than 60 years ago. Our smaller families are subject to more intense parenting than before. Yet we seem to care more in general—safetyism is rife—than in particular: the lives of infants and old people have to fit around other schedules, and women have fewer children than they say they want or none at all, put off by a host of factors, from housing to fear of dependence on an unreliable partner.

There are no easy, or cheap, answers to the care dilemma, but imagine if we valued reproduction as much as production. We would build a family-friendly, part-time work culture during the reproductive years in which both parents, with the help of grandparents and the state, could combine childcare with varying levels of paid work, keeping career progression alive. And a more general revival of home life is now possible thanks to more working from home, AI and the potential for a shorter work week, and men taking on more domestic work.

Yes, men need to step up more, and should be encouraged to do so with paternity leave of three months, rather than the current two weeks. Our miserly maternity pay needs upgrading too and it should be possible to retain some single-parent benefits for a period after forming a new relationship to promote stability.

But the best idea for reducing stress in the early years of parenthood, when relationship breakdown is common, is to make it financially easier for one parent—mother or father—to stay at home supported by a Home Care Allowance (HCA) as in Finland. Combining recognition of the family in the tax system with concentrating child benefit on the early years and, most important, the payment of childcare subsidies (total £9bn a year) direct to families, could produce an HCA of almost £10,000 a year, without big extra burdens on the taxpayer.

Meanwhile, demand for social care is steadily rising while the supply of carers (82% female) is steadily shrinking, thanks to women’s greater opportunities and the continuing low value attached to it. But the Institute for Fiscal Studies says it would cost £1.5bn a year to pay care workers £1 an hour above the minimum wage. Creating a new Enhanced Care Practitioner role, trained to carry out minor medical interventions as happened during Covid, would also attract more people to the sector and in the long run save money.

Our dominant professional class – those I have labelled the ‘Anywheres’ – are public-realm people and tend to see equality through the lens of professional work and 50:50 representation. They have been wary of promoting a pro-family agenda, despite generally choosing conventional arrangements for themselves, not just to avoid stigmatising single parents but also because of a sense that domesticity and the work of care represents womens’ past not their future.

But the care that we need and want to give, both at home and in the care economy, is oblivious to such luxury beliefs. Isn’t it time we, and our politicians, had a more honest conversation about the care dilemma?

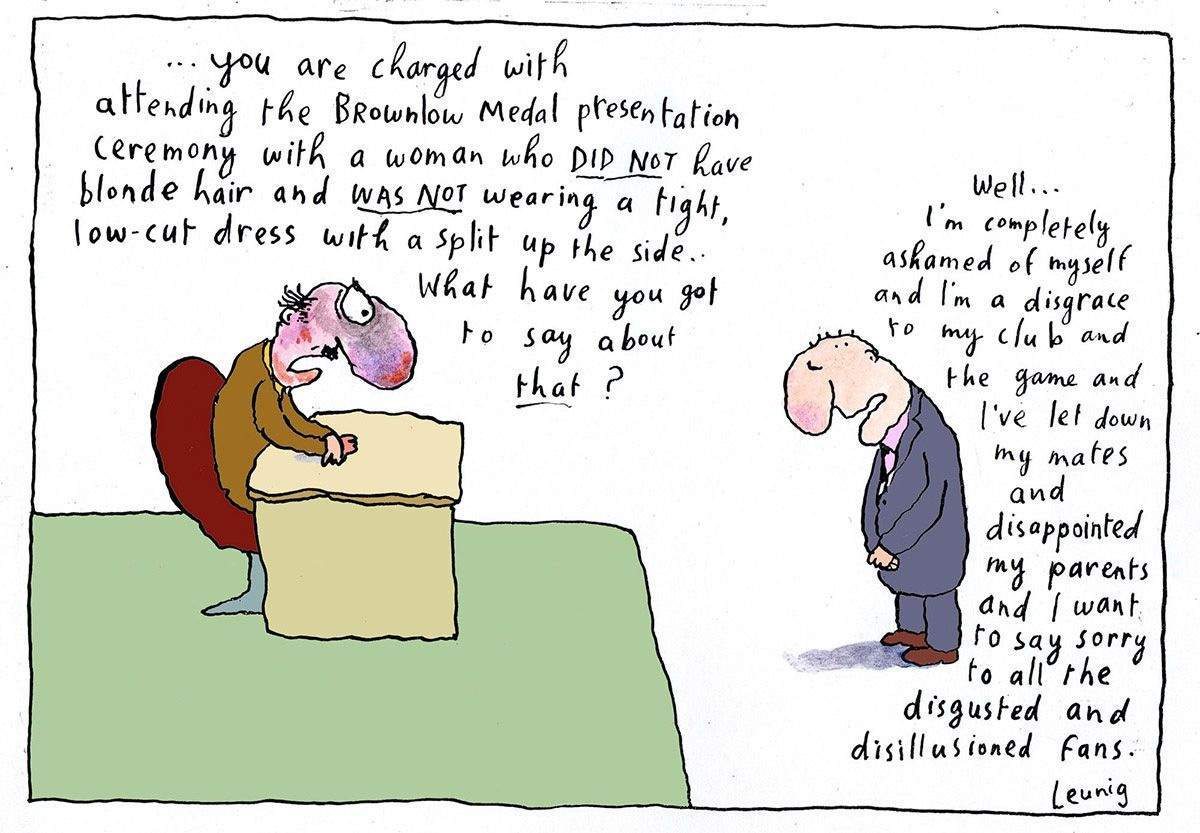

David Shoebridge, cartoon, potter's wheel - terrific. Thanks, Nicholas.