Two types of anti-semitism

Why is Gen Z so tolerant of hate speech and verbal harassment of Jews, when it shows the lowest tolerance for such speech against other groups?

Jonathan Haidt

I was struck and provoked into this post by a recent post on American campus anti-semitism by someone I’m normally a big fan of — Jonathan Haidt. Haidt explains the extraordinary and catastrophic transformation of the culture of American universities in just a decade. The graph extracted above ia spectacular demonstration of what he’s talking about, even if at least some of the rot in the red line is attributable to the propaganda of Fox News and its epigones).

The kind of comment I’ve extracted above is now quite common in the opinionosphere and, as you would expect from Haidt, it is properly documented here. Thus in his post in a literal sense it is true and Haidt’s sources show that it’s based on younger people’s stated opinions about “Jews” not “Israel”. It also explains that the engine behind this position is young people’s identitarian ideologies and their seeing “Jews” as oppressors and the Palestinians as the oppressed. (The coloniser/colonised dichotomy is also being shoehorned into place here, though it’s a bit of a rough and ready fit.)

This speaks to the power of the new paradigm Haidt has done so much to articulate and critique, rather than to anti-semitism as a force in itself. That is, Israel, and by association Jewishness is caught up in the way in which the oppressor oppressed dichotomy dominates discourse, chewing through everything in its wake. All that is true, and it’s lamentable. It demonstrates the bankruptcy of the identitarian frolic our whole civilisation has been on for a few decades now and the reorientation of ideological debate around ‘attack surfaces’ which of course leads to the hardening of those attack surfaces — now revved up by social media.

But we’ve seen this before. Privileged students celebrating the Hamas attacks even before Israel’s response to them is barbaric. But it’s of a piece with the ‘you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs’ approach we saw from Stalinists in response to Stalin’s crimes, and Maoists in response to Mao’s crimes. Ditto when Pol Pot went on the rampage (or, for that matter Donald Rumsfeld glee at how messy the ‘liberation’ of Baghdad was.)

Then there’s something that’s more clearly anti-semitism — and antisemitism capable of mutating into genocidal antisemitism. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m thinking that the folks outside the Sydney Opera House chanting ‘Gas the Jews’ weren’t privileged university students. And, far from feeling defended against such outrages, officials advised Jews to steer clear of the relevant areas.

I re-published Suzanne Rutland’s documentation of anti-semitism among muslim school students in Sydney’s South Western suburbs. It was virulent enough to leave Jewish teachers feeling threatened and afraid to reveal their Jewish identity. To refresh:

Jewish teachers in these schools have experienced harassment from their Muslim students; one Jewish teacher had to request a transfer on compassionate grounds following ongoing harassment from the students. Teachers who are Jewish in schools with a high concentration of Muslim Arabic pupils have been counseled not to reveal that they are Jewish. One said, “I am not able to come out—I want my students to know I am a person like anyone else, just flesh and blood”. Another, almost in tears, said this: “I am terrified that the students will find out that I am Jewish. I am very ashamed to say this”. Another teacher who is not Jewish, but who is interested in Judaism, mentioned this interest to the principal of the school who was supportive but warned the teacher not to reveal this interest to the students.

In these interviews, the teachers said that most of the prejudicial views came from the students’ homes; students reported that this is what their parents have told them. The students experience a sense of disconnection when their teachers tell them something different about the Jewish people or the Holocaust from what they have learnt at home. In addition, outside authorities, including the religious leaders in the mosques, tend to undermine Western influences so that teachers in government schools often face serious discipline problems. As one teacher put it:

We [the teachers] have been called sharmuta—which means whore, prostitute in Arabic—we have made complaints.... The students are learning that there are no serious consequences for disrespect, for hatred, for racism, discrimination, verbal abuse, and even violence.

I know that in Syria, Lebanon, Sudan, Iraq, Kuwait, they do know how to respect authority figures and teachers and even women to a certain level within their own culture. They have been allowed to use our system and disregard it at the same time because there are no consequences for their behaviour.

We don’t seem to be doing much about it. Jewish students have successfully taken legal action against anti-semitism in Brighton Secondary College in Victoria and good on them, but I expect you need to be fairly wealthy or from a fairly well established community to have the funds splash on our legal system which guzzles funds like a Abrams tank guzzles fuel.

Still, perhaps some Jewish organisations should try helping out some Jewish students and teachers out in the kind of action taken by the Brighton Secondary College students. Meanwhile the official response seems to be to more or less turn a blind eye. I don’t say that because I have any great confidence that I know what officials should do, but I do think we should be open about it as an important problem and something that our schools need to work against. Where is the ABC on the subject? Perhaps it’s done some stories on it. I don’t know.

Some final thoughts:

Israel’s abandonment of a settlement with the Palestinians that is not based on domination makes it harder for us to fight anti-semitism here — even if it is an essentially separate subject. I’m aware that many defenders of Israel believe that their efforts to arrive at a settlement have been consistently rebuffed by the Palestinian leadership. I have two responses to that. First, I don’t know enough to disagree with much conviction but there are plenty of people I respect who do. And secondly, whether or not it is just, whether or not it is possible, my own hunch is that if such a peace cannot be delivered Israel will eventually become engulfed by the very oppressor/oppressed dichotomy that Haidt laments as it influences international opinion. (To say nothing of the greater numbers muslims will be able to deliver to Western politicians). So in the long run, it seems to me that if a reasonable peace cannot be forged Israel’s position will become more and more precarious — as white South Africa’s did.

A truly liberal society would really focus on fighting anti-semitism in its schools. Australia should work vigilantly to prevent immigrants from importing foreign hatreds to our shores, and when it does happen we should be clear eyed and articulate about where the problems are — rather than handle them with the usual ideological culture war in which accusations of Islamophobia and anti-semitism are thrown around by all the usual suspects and no-one is any the wiser. And where there was the kind of anti-semitism I’ve documented above we’d put some real effort into engaging relevant community in the task of supporting liberal values.

William Hague gets on board

William Hague has caught the bug for democratic lottery. And he writes about it well. This simple sentence is a nice little microcosm. “Social media companies are poisoning the democratic world with the addictive spread of narrow and intemperate opinions.” Hear hear.

Writing about the idea, first proposed in Ireland seven years ago, that a citizen assembly be consulted about what to do about abortion, Hague takes up the story.

This idea was met by considerable scepticism. The Irish opposition party of the time, Fianna Fail, thought that “an issue of such sensitivity and complexity” could not be dealt with adequately in this way. The chosen citizens would just reflect the existing deep divisions in society. They would not be sufficiently expert. A judge-led commission would have more expertise and carry more weight. That would be more “intellectually coherent”.

Yet the citizens’ assembly was established nonetheless, and over the following six months something fascinating and inspiring occurred. An appointed chairwoman and 99 “ordinary” people, chosen at random and therefore completely varied in age, gender, regionality and socioeconomic status, did a remarkable job. They adopted some commendable principles for their debates, including respect, efficiency and collegiality. They listened to 25 experts and read 300 submissions. They heard each other out and compromised more effectively than elected representatives.

The result was an overwhelming recommendation that the constitution should be changed, and a clear majority view that the relevant section of it should be deleted and replaced, permitting their parliament to legislate on abortion in any way it saw fit. This was later endorsed in a historic referendum. One of the country’s most intractable issues had been resolved clearly and decisively, in a way the political parties could not have managed and would not have dared. …

[Then after summarising some of the ways in which democracy is coming apart, Hague continues.] At a time when all these trends are turning people against their own compatriots and reducing debate to simplistic and unsubstantiated assertions, it has to be a source of hope that if you put 100 random people in a room with an important question and plenty of real information, they will often prove that democracy isn’t yet finished. They will listen patiently, think clearly and find solutions. Somewhere, in this gathering darkness of hatred, lies and opposing cultural identities, there are open-minded and constructive citizens willing to turn on a light.

He also notes how many of his fellow parliamentarians are against the idea. It’s easy to say that that would reduce their power, but in my experience it’s not nearly so simple. Politicians think their job is to come up with good policy. They do try, but the whole fabric of political life is keeping powerful people happy. But they live in hope. Perhaps one day more of them will realise that to actually do good policy you need allies. And a citizen assembly is a useful ally for a positive centrist government (from either the left or right), just as the accord was a very powerful ally for the Hawke and Keating Governments.

My one disappointment is that, Hague’s imagination does not run beyond the idea of citizen assemblies as bodies with only advisory power. But I would say that, wouldn’t I?

I don’t know about the devil, but it sure is pretty

Metaphysical misdirection: how did fancy maths coexist with childishly naïve empirical beliefs?

It’s a good question, with some good thoughts in an attempt to answer it.

There's something very weird about the timeline of scientific discoveries.

For the first few thousand years, it’s mostly math. Maybe a bunch of math nerds hijacked the list, but it's pretty obvious that humans figured out a lot of math before they figured out much else. The Greeks had the beginnings of trigonometry by ~120 BCE. Chinese mathematicians figured out the fourth digit of pi by the year 250. In India, Brahmagupta devised a way to “interpolate new values of the sine function” in 665, and by this point we're already at mathematics that I no longer understand.

Meanwhile, we didn't discover things that seem way more obvious until literally a thousand years later. It's not until the 1620s, for instance, that English physician William Harvey figured out how blood circulates through animal bodies by, among other things, spitting on his finger and poking the heart of a dead pigeon. We didn't really understand heredity until Gregor Mendel started gardening in the mid-1800s, we didn't grasp the basics of learning until Ivan Pavlov started feeding his dogs in the early 1900s, and we didn't realize the importance of running randomized-controlled trials until 1948. Oh, and for 13 centuries, people thought that rotting meat turns into maggots, until Francesco Redi did this (See graphic).

What took us so long? How did all this low-hanging fruit go unplucked for centuries? Our ancestors weren't stupid—they were absolutely nailing it in math, racking up centuries of top-notch numbers stuff, even while they were like , “I hope my meat doesn't rot and turn into maggots.”

Pascal weighs in on a similar distinction

Pascal isn’t speaking about the same distinction here, but the post Mastroianni’s post on mathematical versus scientific reason above put me in mind of this pense from Pascal’s Pensees. It’s on the difference between mathematical and what Pacal calls ‘intuitive’ reasoning. One might also call it ‘vision’.

The difference between the mathematical mind and the practical mind. — In the one the premisses are palpable, but removed from ordinary use, so that from want of habit it is difficult to look in that direction, but if we take the trouble to look, the premisses are fully visible, and we must have a totally incorrect mind if we draw wrong inferences from premisses so plain that it is scarce possible they should escape our notice.

But in the practical mind the premisses are taken from use and wont, and are before the eyes of every body. We have only to look that way, there is no difficulty in seeing them; it is only a question of good eyesight, but it must be good, for the premisses are so numerous and so subtle, that it is scarce possible but that some escape us. Now the omission of one premiss leads to error, thus we must have very clear sight to see all the premisses, and then an accurate mind not to draw false conclusions from known premisses.

All mathematicians would then be practical if they were clear-sighted, for they do not reason incorrectly on premisses known to them. And practical men would be mathematicians if they could turn their eyes to the premisses of mathematics to which they are unaccustomed.

The reason therefore that some practical men are not mathematical is that they cannot at all turn their attention to mathematical premisses. But the reason that mathematicians are not practical is that they do not see what is before them, and that, accustomed to the precise and distinct statements of mathematics and not reasoning till they have well examined and arranged their premisses, they are lost in practical life wherein the premisses do not admit of such arrangement, being scarcely seen, indeed they are felt rather than seen, and there is great difficulty in causing them to be felt by those who do not of themselves perceive them. They are so nice and so numerous, that a very delicate and very clear sense is needed to apprehend them, and to judge rightly and justly when they are apprehended, without as a rule being able to demonstrate them in an orderly way as in mathematics; because the premisses are not before us in the same way, and because it would be an infinite matter to undertake. We must see them at once, at one glance, and not by process of reasoning, at least up to a certain degree. And thus it is rare that mathematicians are practical, or that practical men are mathematicians, because mathematicians wish to treat practical life mathematically; and they make themselves ridiculous, wishing to begin by definitions and premisses, a proceeding which this way of reasoning will not bear. The mind does indeed the same thing, but tacitly, naturally and without art, in a way which none can express, and only a few can feel.

Practical minds on the contrary, being thus accustomed to judge at a glance, are amazed when propositions are presented to them of which they understand nothing and the way to which is through sterile definitions and premisses, which they are not accustomed to see thus in detail, and therefore are repelled and disheartened.

But inaccurate minds are never either practical or mathematical. Mathematicians who are only mathematicians have exact minds, provided all things are clearly set before them in definitions and premisses, otherwise they are inaccurate and intolerable, for they are only accurate when the premisses are perfectly clear.

And practical men, who are only practical, cannot have the patience to condescend to first principles of things speculative and abstract, which they have never seen in the world, and to which they are wholly unaccustomed.

Thomas Hardy’s Christmas Ghost

From the London Review of Books blog:

Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘A Christmas Ghost-Story’ was published in the Westminster Gazette in December 1899, two months after the start of the Second Anglo-Boer War. The ghost is that of a soldier, and the poem emphasises his unknown nationality:

South of the Line, inland from far Durban,

There lies – be he or not your countryman –

A fellow-mortal. Riddled are his bones,

But ’mid the breeze his puzzled phantom moansWhen the Daily Chronicle accused Hardy of peddling pacifism, he spent much of Christmas Day writing a riposte to the editor, reminding him that the soldier’s ghost in his story now had ‘no physical frame’; ‘his views are no longer local, nations are all one to him; his country is not bounded by seas, but is co-extensive with the globe itself.’ He concluded:

Thus I venture to think that the phantom of a slain soldier, neither British nor Boer, but a composite, typical phantom, may consistently be made to regret on or about Christmas Eve (when even the beasts of the field kneel, according to a tradition of my childhood) the battles of his life and war in general.

As a child, I thought that the unknown soldier’s country was also unknown, and considered it extraordinarily wonderful that a stateless subject was commemorated in Westminster Abbey.

Hardy and his wife both strongly opposed the imperial war in South Africa. ‘The Boers fight for homes & liberties,’ Emma Hardy wrote. ‘We fight for the Transvaal Funds, diamonds, & gold!’ …

Hardy’s radical universalism punctuates his work. In 1917 he wrote to the secretary of the Royal Society of Literature:

That nothing effectual will be accomplished in the cause of Peace till the sentiment of Patriotism be freed from the narrow meaning attaching to it in the past (still upheld by Junkers and Jingoists) and be extended to the whole globe.

On the other hand, that the sentiment of Foreignness – if the sense of a contrast be really rhetorically necessary – attach only to other planets and their inhabitants, if any.

I may add that I have been writing in advocacy of those views for the last twenty years.

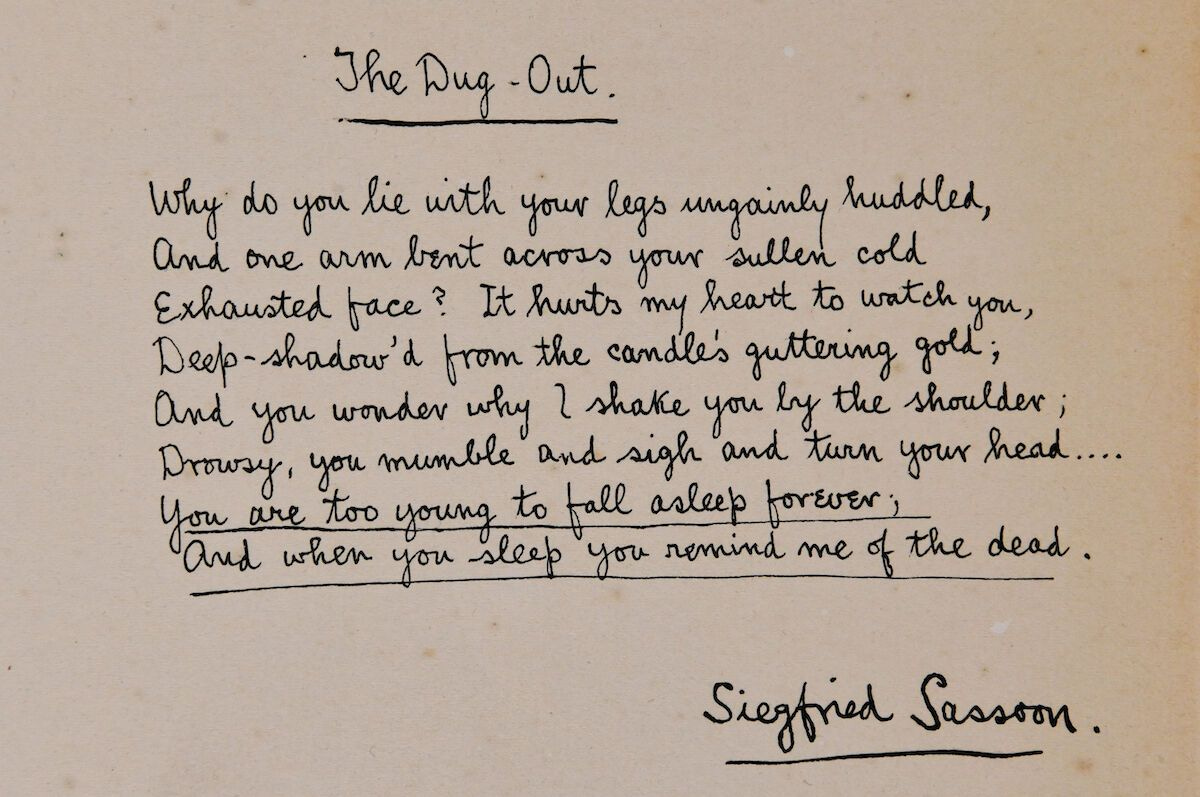

Hardy’s friend Siegfried Sassoon – his father was of Jewish and Iraqi Indian descent and his mother was an Anglo-Catholic Germanophile who gave him his German name – had good reason to reject the idea that conflict was inevitable or desirable. He began writing to Hardy in January 1916, a few months before the Battle of the Somme. Wounded in 1917, he sent his famous statement of protest first to Hardy. Published by Sylvia Pankhurst in her newspaper, The Workers’ Dreadnought, on 28 July, it was read out in the House of Commons by a Labour MP two days later and printed in the Times the next day.

‘I am a soldier,’ Sassoon wrote, ‘convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest.’ He was sent to Craiglockhart, a military psychiatric hospital in Edinburgh, in lieu of being court-martialled. After the war, Sassoon joined the Labour Party and lectured on pacifism, becoming literary editor of the Daily Herald, ‘the new labour paper’, as he referred to it in a letter to Hardy. In February 1922 Florence Hardy told Sassoon that she had heard Hardy say, ‘in a loud & clear voice’: ‘I wrote my poems for men like Siegfried Sassoon.’ Sassoon selected his poem ‘The Dug-Out’ for the tribute book from a younger generation of poets that he presented to Hardy in October 1919.

The end of history: been there, done that

Why Have Feminists Been So Slow to Condemn the Hamas Rapes?

Good question. Quite a good answer if only the author weren’t so tribal. Overly preoccupied with where she — and everyone else she talks about — is in the ideological spectrum.

Until recently, feminist groups in the United States have had little to say. This silence sits oddly with how quick our movement has been to credit much iffier claims and to raise consciousness around sexual misconduct that falls far short of rape. What happened to the clarion call to “believe women”? What happened to #metoo? …

Where’s the Women’s March? Feminist Majority? The National Women’s Studies Association? Despite much urging, It took the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women eight weeks to issue a statement condemning the October 7 attacks, finally expressing alarm over “the numerous accounts of gender-based atrocities and sexual violence” and calling for investigation and prosecution. …

Slowly, under pressure from the media, some feminist organizations are finally chiming in. … Whatever the reason, it shouldn’t have taken this long to acknowledge reality. It shouldn’t have been this hard. It shouldn’t take conservatives like Bret Stephens and the right-wing Independent Women’s Forum to speak plain truths about rape—if about little else. Meanwhile, the left spouts extravagant slogans like “Palestinian liberation is queer liberation”—the ultimate in “everything is connected” politics. In a similar vein, the Georgia-based abortion fund ARC-Southeast put out a long statement headed “Reproductive Justice Includes Palestinian Liberation” without so much as mentioning that abortion is illegal in both Gaza and the Palestinian Authority. Maybe they don’t know. That statement has been cosigned by over 50 reproductive rights and justice organizations, including the National Network of Abortion Funds. …

Virginia Woolf wrote, “As a woman, I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world.” A noble thought—whatever happened to it?

The anti-semitism sting

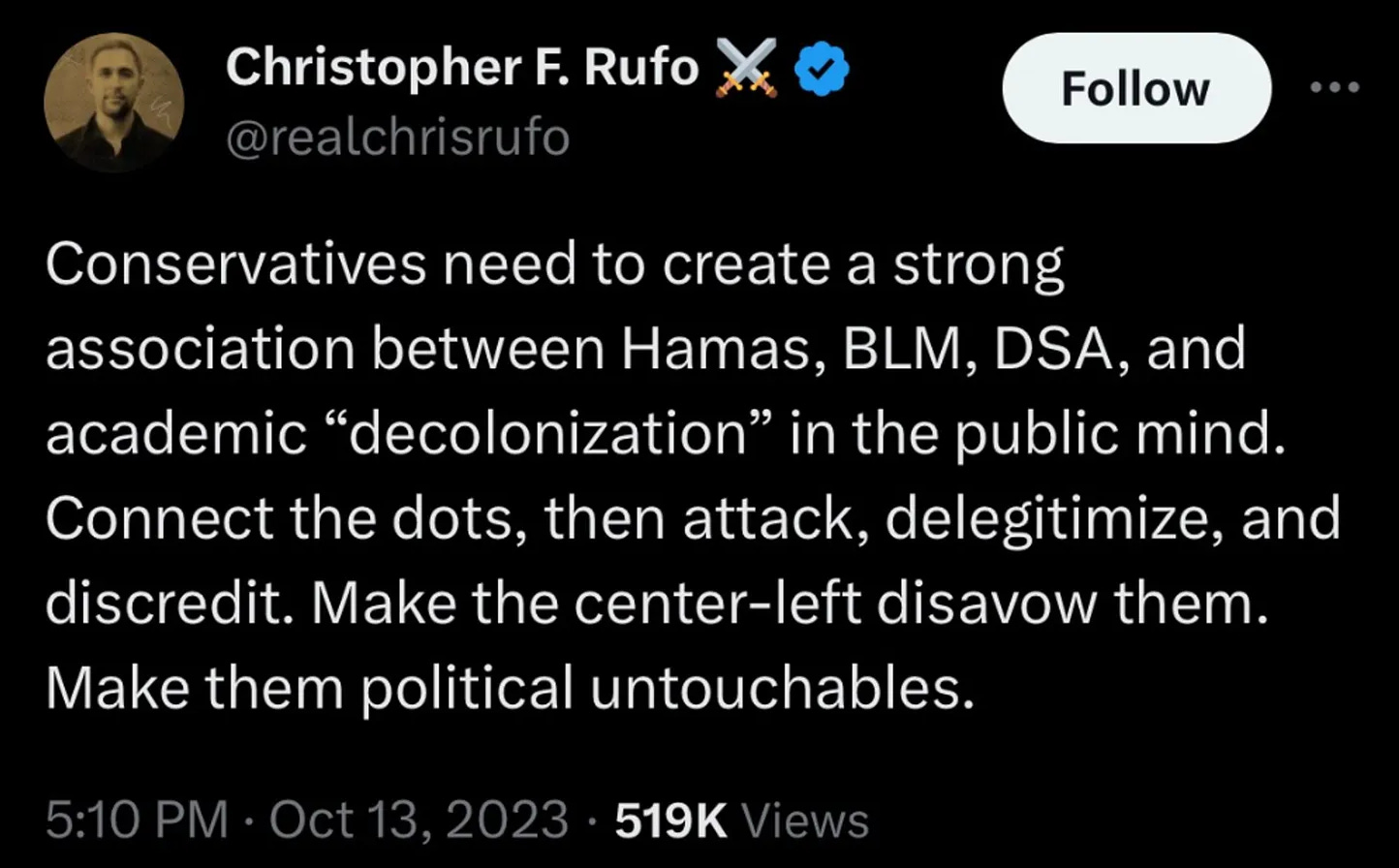

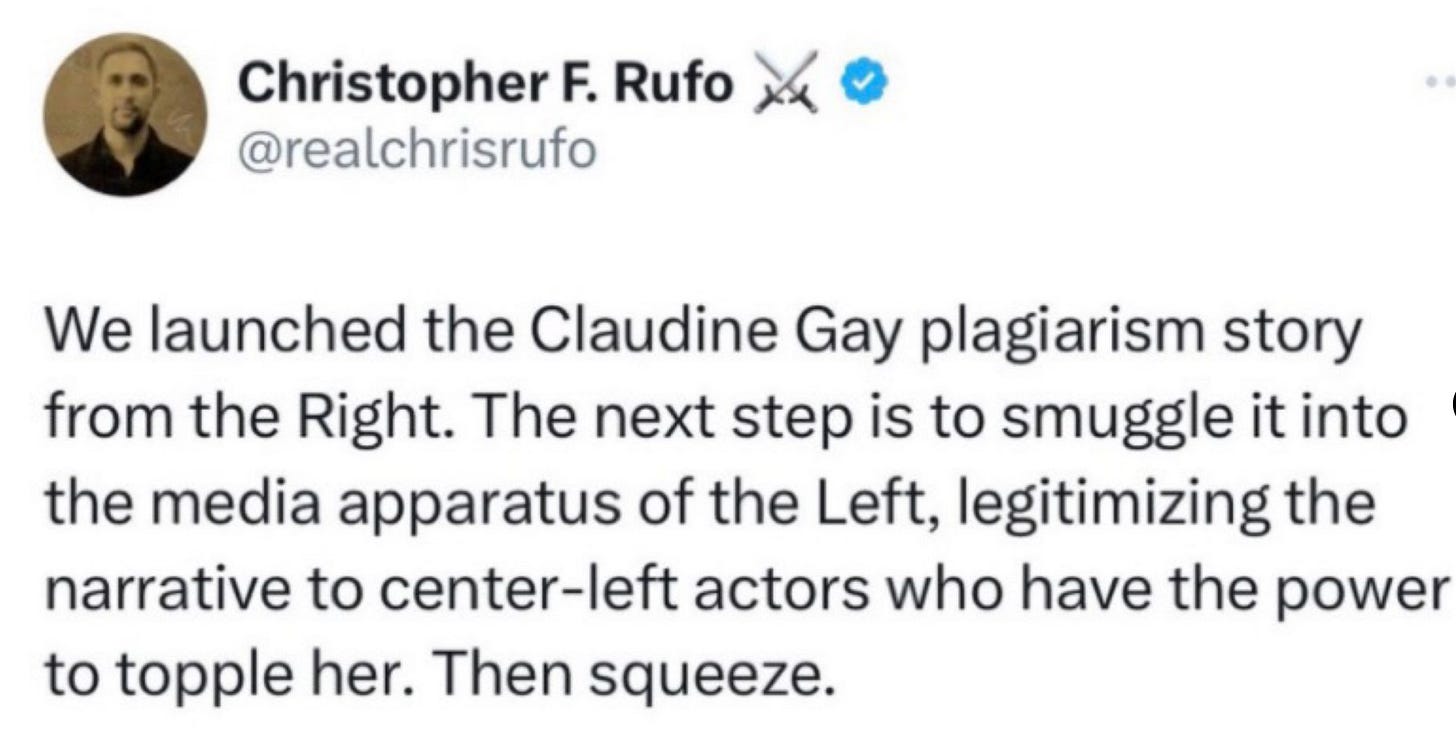

A good provocative bit of debunking by Don Moynihan:

Elise Stefanik, a member of Congress who has trafficked in Great Replacement white nationalist theory, called three female leaders of universities to Congress alleging they were enabling anti-semitism. She called for all of them to resign. One did. Two universities stood by their leaders. Other far-right figures pursued Claudine Gay, the President of Harvard, accusing her of plagiarism. But really the goal is to remove her as a symbol of diversity, equity and inclusion. And too many in the media have been active participants in this campaign. …

[I]t makes sense to start with Christopher Rufo. Rufo is the most effective culture war strategist in attacking public education generally, and what he argues is the excessively liberal nature of higher education, in particular. His main tactic, repeated again and again, is to come up with a negative brand, and then demand that powerful actors denounce that negative brand, and do something about it that erases a broader set of liberal values. He has done this with discussions of race (labeling it Critical Race Theory) and gender (accusing those allowing discussion of gender in schools to be “groomers”) in classrooms. He saw the opportunity to leverage anti-semitic student protests as part of his broader attack on higher education. …

Stefanik’s hearing saw the leader of Penn, after the urging of some donors, resign. But Harvard announced its support for Gay. Then Rufo took a different tack, which was to push a campaign against Claudine Gay for instances of plagiarism.

I focus on the Times not because it is unusual, but because it is the standard bearer for the news. It wasn’t just the Times. Other national media treated the topic as national news. Something more important than almost everything else. Something that deserves your attention.

In doing so, the media fed Rufo’s feeding frenzy. The story was newsworthy because they said it was newsworthy. It justifies the dubious idea that Congress, which has another government shutdown pending, should spend its time investigating the research record of one university leader. Which will then generate another round of stories.

Rufo’s campaign worked. He announced it publicly, explained its motivations, the media played their assigned role, and Rufo took the credit. You might ask how this can happen, but the better question is why it keeps happening. …

Gay is being attacked because she is seen by the right as undeserving of the job. A diversity hire. Too woke. Taking the university in the wrong direction. In particular, Gay is under attack because she has been perceived as too supportive of DEI as a university Dean.

If Gay is removed, it will be as much a victory for the New York Times, Jake Tapper and others in the media as it will be to Chris Rufo. A testimony to their power, but also to their incredulity and willingness to serve the goals of others.

The Satire of the Trades

‘The scribe, whatever his place at the Residence. He cannot be poor in it’.

From an ancient Egyptian text. HT: Brad Delong

Beginning of the teaching made by the man of Tjaru called Dua-Khety for his son called Pepy. It was while he was sailing south to the Residence to place him in the writing school among the children of officials, of the foremost of the Residence.

He said to him:

I have seen violent beatings: so direct your heart to writing. I have witnessed a man seized for his labour. Look, nothing excels writing. It is like a loyal man. Read for yourself the end of the Compilation and you can find this phrase in it saying ‘The scribe, whatever his place at the Residence. He cannot be poor in it’.

He accomplishes the wish of another when he is not succeeding I do not see a profession like it that you could say that phrase for, so I would have you love writing more than your mother and have you recognise its beauty For it is greater than any profession, there is none like it on earth. He has just begun growing, and is just a child, when people will greet him (already). He will be sent to carry out a mission,and before he returns, he is clothed in linen (like an adult man).

I do not see a sculptor on a mission or a goldsmith on the task of being despatched but I see the coppersmith at his toil at the mouth of his furnace his fingers like crocodile skin his stench worse than fish eggs.

The jeweller drills in bead-making using all of the hardest hard stones. When he has completed the inlays, his arms are destroyed by his exhaustion. He sits at the food of Ra with his knees and back hunched double.

The barber shaves into the end of the evening continually at the call, continually on his elbow, pushing himself continually from street to street looking for people to shave. He does violence to his arms to fill his belly, like bees that eat at their toil.

The reedcutter sails north to the marshes to take for himself the shafts (?). When he has exceeded the power of his arms in action, When the mosquitoes have slaughtered him and the gnats have cut him down too, then he is broken in two.

The small potter is under his earth even when he is stood among the living. He is muddier with clay than swine to burn under his earth. His clothes are solid as a block and his headcloth is rags, until the air enters his nose coming from his furnace direct. When he has made the pestle out of his legs, the pounding is done with himself, smearing the fences of every house, and beaten by his streets.

Let me tell you what it is like to be a bricklayer the bitterness of the taste. He has to exist outside in the wind, building in his kilt, his robes a cord from the weaving-house stretching round to his back. His arms are destroyed by hard labour. mixed in with all his filth. He eats the bread with his fingers though he can only wash the once.

For the carpenter with his chisel (life) is utterly vile covering the roof in a chamber, measuring ten cubits by six. to cover the roof in a month after laying the boards with cord of the weaving-house All the work on it is done, but the food given for it couldn’t stretch to his children.

The gardener has to carry a rod and all his shoulder bones age, and there is a great blister on his neck, oozing puss. He spends his morning drenching leeks, his evening in the mire. He has spent over a day, after his belly is feeling bad. So it happens that he rests dead to his name aged more than any other profession.

The field labourer complains eternally his voice rises higher than the birds, with his fingers turned into sores, from carrying overloads of produce (?). He is too exhausted to report for marsh work, and has to exist in rags. His health is the health on new lands; sickness is his reward. His state work there is whatever they have forgotten. If he can ever escape from there, he reaches his home in utter poverty, downtrodden too much to walk.

The mat-weaver (lives) inside the weaving-house he is worse off than a woman, with his knees up to his stomach, unable to breathe in any air. If he wastes any daytime not weaving, he is beaten with fifty lashes. He has to give a sum to the doorkeeper to be allowed to go out to the light of day.

The weapon-maker is denigrated utterly going out to the hill-land. What he give to his ass is greater than the work that results, and great is his gift to the man in the country who puts him on the track. He reaches his home in the evening, and the travelling has broken him in two.

The trader goes out to the hill-land after bequeathing his goods to his children, fearful of lions and Asiatics. He recognises himself again, when he is in Egypt (He reaches his home in the evening, and the travelling has broken him in two.) His house is of cloth for bricks, without experiencing any pleasure.

The stny-worker his fingers are rotted, the smell of them is as corpses, and his eyes are wasted by the mass of flame. He can never be rid of his stn, spending his day cut by the reed; his own clothing is his horror.

The sandalmaker is utterly the worst off with his stocks of more than oil. His health is health as corpses, as he bites into his skins.

The washerman does the laundry on the shore neighbour to the crocodiles. ‘Father is going to the water of the canal’, he says to his son and his daughter. Is this not a profession to be glad for, more choice than any other profession? The food is mixed with places of filth, and there is no pure limb on him. He puts on the clothing of a woman who was in her menstruation. Weep for him, spending the day with the washing-rod, with the cleaning-stone upon him. He is told ‘dirty washbowl, come here, the fringes are still to be done!’

The bird-catcher is the most utterly miserable he is more miserable than any other profession. His toil is on the river, mixed in with the crocodiles. When the collection of his dues takes place, then he is always in lament. He can never be told ‘there are crocodiles surfacing’: his fear has blinded him. If he goes out, it is on the water of the canal, he is as at a miracle. Look, there is no profession free of directors, except the scribe – he IS the director.

If, though, you know how to write that is better life for you than these professions I show you; protector of the worker, or his wretch the worker? The field labourer of a man cannot say to him ‘do not watch over (me)’. Look, the trouble of sailing south to the Residence, look, it is trouble for love of you. A day in the school chamber is more useful for you than an eternity of its toil in the mountains. It is the fast way, I show you. Or should I inspire desire for being woken at dawn to be bruised?

Let me tell you in another manner do not come too close in good bearing. If you enter when the lord of the house is at home, and his arms are extended to another before you, You are to be seated with your hand on your mouth. Do not request anything beside him, but react to him when addressed, and avoid joining the table.

If you are walking behind officials do not come too close in good bearing. If you enter when the lord of the house is at home, and his arms are extended to another before you, You are to be seated with your hand on your mouth. Do not request anything beside him, but react to him when addressed, and avoid joining the table.

Be serious with anyone greater in dignity Do not speak matters of secrecy, for the secretive is the one who can shield himself Do not speak matters of boasting, but take your seat with the reliable.

If you come out from the school chamber when you have been told the midday hour, for coming and going in the streets Debate for yourself the end of the place

If an official sends you on a mission say it exactly as he says it, without omission, without adding to it. Whoever leaves out the declamation (?),his name shall not endure, but whoever completes with all his talent, nothing will be kept back from him, he will not be parted from all his places.

Do not tell lies against a mother – that is the extreme for the officials. If it has happened, his arms are mustered, and the heart has made him weak, do not add to it with meekness. That is worse for the belly, when you have heard. If bread satisfies you, and drinking two jars of beer, there is no limit for the belly one would fight for; if another is satisfied standing up, avoid joining the table.

Look, you send out the throng, you hear the words of officials, Behave then like the children of (important) people, when you are going to collect them. The scribe is the one seen hearing (cases); Would fighters be the ones to hear? Fight words that are contrary; move fast when you are proceeding – your heart should never trust. Keep to the paths for it: the friends of a man are your troops.

Look – Abundance is on the path of the god and Abundance is written on his shoulder on the day of his birth. He reaches the palace portal, and that court of officials is the one allotting people to him. Look, no scribe will ever be lacking in food or the things of the House of the King, may he live, prosper and be well! Meskhenet is the prosperity of the scribe, the one placed before the court of officials. Thank god for the father, and for your mother, you who are placed on the path of the living. See what I have set out before you, and for the children of your children.

This is its end, perfect, in harmony.

Chile rejected a left-wing constitution. Now it’s rejected a right wing one

Which leaves it with the dictator’s constitution

Chicago economics probably gave Chile the best economy in South America. But it still couldn’t break out into the kind of industrial growth and economic complexity that produced the Miracle in the tiger economies of Asia from the 1960s on. I’m not sure I trust this report, so nicely does it confirm with the authors’ priors, and the big interpretations (for instance at the end) seem like hunches, but the whole story is fascinating. And like a few referendums in Australia, it shows how voters demanding change doesn’t mean they can agree on what it should be!

In the early phase, when progressives like Boric took the lead in opposing the old constitution, the international left saw Chile as a model for radical change, and some American leftists argued the United States should rewrite its foundational document from scratch. Now that Chile is stuck for the foreseeable future with the constitution it spent four years trying to replace, few seem to be turning to the South American nation for lessons. This is a mistake. Chile’s aborted attempt to rewrite its constitution is a cautionary tale for all of those seeking a radical break—whether from the right or from the left—with the “end-of-history” consensus known as neoliberalism. …

[T]he fruits of the Chicago Boys’s neoliberal reforms came mainly under the stewardship of Pinochet’s democratic successors. After two decades of political turmoil and economic pain under Allende and Pinochet, Chile witnessed an economic boom in the 1990s thanks to high commodity prices. Democratically elected presidents also secured trade deals that had previously eluded the pariah dictatorship. GDP growth averaged 7 percent a year, and per capita GDP doubled by 2010—the year Chile became the first South American country to join the OECD.

Beneath all the achievements hailed by economists, the “Chilean miracle” had a dark underside. Rates of single motherhood soared from 13 percent in 1975 to 40 percent in 2015. Mass unemployment during the 1980s, the result of Pinochet’s fiscal austerity, gave way to mass job insecurity during the period of rising prosperity. Older forms of informal employment gave way in recent years to the expanding gig economy of delivery and rideshare apps.

Moreover, despite all the radical changes, the Chilean economy never escaped the curse suffered by most of Latin America: reliance on the export of primary products. Chile accounts for about 25 percent of global copper production, and the mineral accounts for 55 percent of the country’s exports. …

[T]he nascent social movement coalesced around the core demand to replace the 1980 constitution. Piñera, the embattled president, acquiesced to a referendum on the question of Chile’s magna carta, and in October 2020, 80 percent of Chileans voted to convene a constitutional convention.

For a time, the hard left, which had been marginal in Chile ever since Pinochet toppled Allende, appeared ascendant. The progressive Gabriel Boric, a former student activist who promised that Chile would be the “tomb of neoliberalism,” defeated the Pinochet apologist José Antonio Kast by a large margin in 2021. In a show of the zeitgeist, voters also elected left-leaning delegates to the 2021 constitutional convention by a margin of two to one.

What ensued in the convention made clear that the Chilean left has more in common with the college-educated progressives of North America than the leftists of Mexico and Bolivia— who still manage to appeal to workers and rural populations. The televised convention quickly devolved into Chile’s own oppression olympics. …

[With the recent constitutional draft by the right] vague language left open the possibility that abortion would be banned altogether, with no medical exceptions, and that water would remain privatized. That said, the fact the right-wing document lost less resoundingly than the left-wing one speaks to the continued backlash against Chilean progressivism. …

The truth is that Chilean voters, on the whole, are interested neither in progressive identity politics nor in dogmatic social conservatism—nor in third-way centrism. Rather, like so many others, they hunger for the quotidian staples of industrial democracy: stable and well-paying jobs, security, good pensions, immigration enforcement, and affordable, reliable healthcare. Under Boric, the left has made clear it can’t deliver on these items.

Like Brexit in Britain, Chile’s multiyear constitutional experiment offered a rare opportunity to forge a new societal and economic consensus. Its failure portends an interminable struggle over control of a declining economy between a performative, self-defeating left and a similarly impotent reactionary right. Whatever the future brings, one thing is certain: The Chilean miracle has run its course.

Orwell’s preface to Animal Farm

This preface was not published with the book in 1943 for reasons that are explained in the piece. This is from the New York Times archive from its original publication in 1972. Apologies for various rogue gaps in words. I fixed quite a lot, but didn’t eliminate them. Thanks to Danny Finley for bringing it to my attention.

This book was first thought of, so far as the central idea goes, in 1937, ‐but was not written down until about the end of 1943. By the time when it came to be written it was obvious that there would be great difficulty in getting it published (in spite of the present book shortage, which ensures that anything describable as a book will “sell”), and in the event it was refused by four publishers. Only one of these had any ideological motive. Two had been publishing anti‐Russian books for years, and the other had no noticeable political color. One publisher actually started by accepting the book, but after making the prelim inary arrangements he decided to consult the Ministry of Information, who appear to have warned him, or at any rate strongly advised him, against publishing it. Here is an extract from his letter:

“I mentioned the reaction I had had from an important official in the Ministry of Information with regard to ‘Animal Farm.’ I must confess that this expression of opinion has given me seriously to think. . . . I can see now that it might be regarded as something which it was highly ill advised to publish at the present time. If the fable were addressed generally to dictators and dictatorships at large then publication would be all right, but the fable does follow, as I see now, so com pletely the progress of the Russian Soviets and their two dictators, that it can apply only to Russia, to the exclusion of other dictatorships. Another thing: it would be less offensive if the predominant caste in the fable were not pigs.* I think the choice of pigs as the ruling caste will no doubt give offense to many people, and particularly to anyone who is a bit touchy, as undoubtedly the Russians are.”

This kind of thing is not a good symptom. Obviously it is not desirable that a Government department should have any power of censorship (except security censorship, which no one objects to in wartime) over books which are not officially sponsored. But the chief danger to freedom of thought and speech at this moment is not the direct interference of the M.O.I. or any official body. If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country, intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves.

Any fair‐minded person with journalistic experience will admit that during this war official censorship has not been particularly irksome. We have not been subjected to the kind of totalitarian “coordination” that it might have been reasonable to expect. The press has some justified grievances, but on the whole the Government has behaved well and and has been surprisingly tolerant of minority opinions. The sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary. Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban. Anyone who has lived long in a foreign country will know of instances of sensa tional items of news—things which on their own merits would get the big headlines—being kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervened but because of a general tacit agreement that “it wouldn't do” to mention that particular fact. So far as the daily newspapers go, this is easy to understand. The British press is extremely centralized, and most of it is owned by wealthy men who have every motive to be dishonest on certain important topics. But the same kind of veiled censorship also operates in books and periodicals, as well as in plays, films and radio. At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right thinking people will accept without question. It not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other but it is “not done” to say it, just as in mid‐Victorian times it was “not done” to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.

* It is not quite clear whether this suggested modification is Mr. —'s own Idea, or originated with the Ministry Information; but seems to have the official ring about it.

At this moment what is demanded by the prevailing orthodoxy is an un critical admiration of Soviet Russia. Everyone knows this, nearly everyone acts on it. Any serious criticism of the Soviet regime, any disclosure of facts which the Soviet Gov ernment would prefer to keep hidden, is next door to un printable. And this nation wide conspiracy to flatter our ally takes place, curiously enough, against a background of genuine intellectual tolerance. For though you are not allowed to criticize the Soviet Government, at least you are reasonably free to criticize our own. Hardly anyone will print an attack on Stalin, but it is quite safe to attack Churchill, at any rate in books and periodicals. And throughout five years of war, during two or three of which we were fighting for national survival, countless books, pamphlets and articles advocating a compromise peace have been pub lished without interference. More, they have been published without exciting much disapproval. So long as the prestige of the U.S.S.R. is not involved, the principle of free speech has been reasonably well upheld, There are other forbidden topics, and I shall mention some of them presently, but the prevailing attitude toward the U.S.S.R is much the most serious symptom. It is, as it were, spontaneous, and is not due to the action of any pressure group.

The servility with which the greater part of the English intelligentsia have swallowed and repeated Russian propaganda from 1941 onward would be quite astounding if it were not that they have behaved similarly on several earlier occasions. On one controversial issue after another the Russian viewpoint has been accepted without examination and then publicized with complete disregard to historical truth or intellectual decency. To name only one instance, the B.B.C. celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Red Army without mentioning Trotsky. This was about as accurate as commemorating the battle of Trafalgar without mentioning Nelson, but evoked no protest from the English intelligentsia. In the internal struggles in the vari ous occupied countries, the British press has in almost all cases sided with the faction favored by the Russians and libeled the opposing faction, sometimes suppressing material evidence in order to do so. A particularly glaring case was that of Colonel Mikhailovich, the Yugoslav Chetnik leader. The Russians, who had their own Yugoslav protégé in Marshal Tito, accused Mikhail ovich of collaborating with the Germans. This accusation was promptly taken up by the British press: Mikhailovich's supporters were given no chance of answering it, and facts contradicting it were kept out of print.

In July, 1943, the Germans offered a reward of 100,000 gold crowns for the capture of Tito, and a similar reward for the capture of Mikhailovich. The British press “splashed” the reward for Tito, but only one paper mentioned (in small print) the reward for Mikhailovich; and the charges of collaborating with the Germans continued. Very similar things happened during the Spanish Civil War. Then, too, the factions on the Republican side which the Russians were determined to crush were recklessly libeled in the English left‐wing press, and any statement in their defense, even in letter form, was refused publication. At present, not only is serious criticism of the U.S.S.R. considered reprehensible, but even the fact of the existence of such criticism is kept secret in some cases. For example, shortly before his death Trotsky had written a biography of Stalin. One may assume that it was not an altogether unbiased book, but obviously it was saleable. An American publisher had arranged to issue it and the book was in print — I believe the review copies had been sent out when the U.S.S.R. entered the war. The book was immediately withdrawn. Not word about this has ever appeared in the British press, though clearly the existence of such a book, and its suppression, was a news item worth a few paragraphs.

It is important to distinguish between the kind of censorship that the English literary intelligentsia voluntarily impose upon themselves, and the censorship that can sometimes be enforced by pressure groups. Notoriously, certain topics cannot he discussed because of “vested interests.” The best‐known case is the pat ent‐medicine racket. Again, the Catholic Church has considerable influence in the press and can silence criticism of itself to some extent. A scandal involving a Catholic priest is almost never given publicity, whereas an Anglican priest who gets into trouble . . . is headline news. It is very rare for anything of an anti‐Catholic tendency to appear on the stage or in a film. Any actor can tell you that a play or film which at tacks or makes fun of the Catholic Church is liable to be boycotted in the press and will probably be a failure. But this kind of thing is harmless, or at least it is understandable. Any large organization will look after its own inter ests as best it can, and overt propaganda is not a thing to object to. One would no more expect The Daily Worker to publicize unfavorable facts about the U.S.S.R. than one would expect The Catholic Herald to denounce the Pope. But then every thinking person knows The Daily Worker and The Catholic Herald for what they are.

What is disquieting is that where the U.S.S.R. and its policies are concerned one cannot expect intelligent criticism or even, in many cases, plain honesty from liberal writers and journalists who are under no direct pressure to falsify their opinions. Stalin is sacrosanct and certain aspects of his policy must not be seriously discussed. This rule has been almost universally observed since 1941, but it had operated, to a greater extent than is sometimes realized, for 10 years earlier than that. Throughout that time, criticism of the Soviet regime from the left could obtain a hearing only with difficulty. There was a huge output of anti Russian literature, but nearly all of it was from the conservative angle and manifestly dishonest, out of date and actuated by sordid motives. On the other side, there was an equally huge and almost equally dishonest stream of pro‐Russian propaganda, and what amounted to a boycott on anyone who tried to dis cuss all‐important questions in a grown‐ manner.

The author

You could, indeed, publish anti‐Russian books, but to do so was to make sure of being ignored or misrepresented by nearly the whole of the high brow press. Both publicly and privately you were warned that it was “not done.” What you said might possibly be true, but it was “inopportune” and “played into the hands of” this or that reactionary interest. This attitude was usually defended on the ground that the international situation, and the urgent need for an Anglo‐Russian alliance, demanded it: but it was clear that this was a rationalization. The English intelligentsia, or a great part of it, had developed nationalistic loyalty toward the U.S.S.R., and in their hearts they felt that to cast any doubt on the wisdom of Stalin was a kind of blasphemy. Events in. Russia and events elsewhere were to be judged by different standards. The endless executions in the purges of 1936–38 were applauded by life‐long opponents of capital punishment, and it was considered equally proper to publicize famines when they happened in India and to conceal them when they happened in the Ukraine. And if this was true before the war, the intellectual atmosphere is certainly no better now.

But now to come back to this book of mine. The reaction toward it of most English intellectuals will be quite simple: “It oughtn't to have been published.” Naturally, those reviewers who under stand the art of denigration will not attack it on political grounds but on literary ones. They will say that it is a dull, silly book and a disgraceful waste of paper. This may well be true, but it is obviously not the whole of the story. One does not say that a book “ought not to have been published” merely because it is a bad book. After all, acres of rubbish are printed daily and no one bothers. The English intelligentsia, or most of them, will object to this book be cause it traduces their Leader and (as they see it) does harm to the cause of progress. If it did the opposite they would have nothing to say against it, even if its literary faults were 10 times as glaring as they are. The success of, for instance, the Left Book Club over a period of four or five years shows how willing they are to tolerate both scur rility and slipshod writing, provided that it tells them what they want to hear.

The issue involved here is quite a simple one: Is every opinion, however unpopular— however foolish, even—en titled to a hearing? Put it in that form and nearly any English intellectual will feel that he ought to say “Yes.” But give it a concrete shape, and ask, “How about an attack on Stalin? Is that entitled to a hearing?” and the answer more often than not will be “No.” In that case, the cur rent orthodoxy happens to be challenged, and so the principle of free speech lapses. Now, when one demands liberty of speech and of the press, one is not demanding absolute liberty. There always must be, or at any rate there always will be, some degree of censorship, so long as organized societies endure. But freedom, as Rosa Luxemburg said, is “freedom for the oth er fellow.” The same principle is contained in the famous words of Voltaire: “I detest what you say; I will defend to the death your right to say it.” If the intellectual liberty which without a doubt has been one of the distinguishing marks of Western civilization means anything at all, it means that everyone shall have the right to say and to print what he believes to be the truth, provided only that it does not harm the rest of the community in some quite unmistakable way. Both capitalist democracy and the Western versions of Socialism have till recently taken that principle for granted. Our Government, as I have already pointed out, still makes some show of respecting it. The or dinary people in the street— partly, perhaps, because they are not sufficiently interested in ideas to he intolerant about them—still vaguely hold that “I suppose everyone's got a right to their own opinion.” It is only, or at any rate it is chiefly, the literary and scientific intelligentsia, the very people who ought to be the guardians of liberty, who are beginning to despise it, in theory as well as in practice.

One of the peculiar phenomena of our time is the renegade liberal. Over and above the familiar Marxist claim that “bourgeois liberty” is an illusion, there is now a widespread tendency to argue that one can defend democracy only by totalitarian methods. If one loves democracy, the argument runs, one must crush its enemies by no matter what means. And who are its enemies? It always appears that they are not only those who attack it openly and consciously, but those who “objectively” endanger it by spreading mistaken doctrines. In other words, defending democracy involves destroying all independence of thought. This argument was used, for instance, to justify the Russian purges. The most ardent Russophile hardly believed that all of the victims were guilty of all the things they were accused of: but by holding heretical opinions they “objectively” harmed the regime, and therefore it was quite right not only to massacre them but to discredit them by false accusations. The same argument was used to justify the quite conscious lying that went on in the left wing press about the Trotskyists and other Republican minorities in the Spanish Civil War. And it was used again as a reason for yelping against habeas corpus when Mosley [Sir Oswald Mosley, the British Fascist leader] was released in 1943.

These people don't see that if you encourage totalitarian methods, the time may come when they will be used against you instead of for you. Make a habit of impris oning Fascists without trial, and perhaps the process won't stop at Fascists. Soon after the suppressed Daily Worker had been reinstated, I was lecturing to a working men's college in South London. The audience were working‐class and lower‐middle‐class intellectuals—the same sort of audience that one used to meet at Left Book Club branches. The lecture had touched on the freedom of the press, and at the end, to my astonishment, several questioners stood up and asked me: Did I not think that the lifting of the ban on The Daily Worker was a great mistake? When asked why, they said that it was a paper of doubtful loyalty and ought not to he tolerated in war time. I found myself defending The Daily Worker, which has gone out of its way to libel me more than once. But where had these people learned this essentially totalitarian outlook? Pretty certainly they had learned it from the Communists themselves!

Tolerance and decency are deeply rooted in England, but they are not indestructible, and they have to be kept alive partly by conscious effort. The result of preaching totalitarian doctrines is to weaken the instinct by means of which free peoples know what is or is not dangerous. The case of Mosley illustrates this. In 1940, it was perfectly right to intern Mosley, whether or not he had committed any technical crime. We were fighting for our lives and could not allow a possible Quisling to go free. To keep him shut up, without trial, in 1943 was an outrage. The general failure to see this was a bad symptom, though it is true that the agitation against Mosley's release was partly factitious and partly a rationalization of other discontents. But how much of the present slide toward Fascist ways of thought is traceable to the anti‐Fascist unscrupulousness it has entailed?

It is important to realize that the current Russomania is only a symptom of the general weakening of the Western liberal tradition. Had the M.O.I. chipped in and definite ly vetoed the publication of this book, the bulk of the English intelligentsia would have seen nothing disquieting in this. Uncritical loyalty to the U.S.S.R. happens to be the current orthodoxy, and where the supposed interests of the U.S.S.R. are involved they are willing to tolerate not only censorship but the deliberate falsification of history. To name one instance. At the death of John Reed, the author of “Ten Days that Shook the World”—a first‐hand account of the early days of the Russian Revolution—the copyright of the book passed into the hands of the British Communist party, to whom I believe Reed had bequeathed it. Some years later, the Brit ish Communists, having destroyed the original edition of the book as completely as they could, issued a garbled version from which they had eliminat ed mentions of Trotsky and also omitted the introduction writ ten by Lenin. If a radical intelligentsia had still existed in Britain, this act of forgery would have been exposed and denounced in every literary paper in the country. As it was, there was little or no protest. To many English intellectuals it seemed quite a natural thing to do. And this tolerance of plain dishonesty means much more than that admiration for Russia happens to be fashionable at this moment. Quite possibly that particular fashion will not last. For all I know, by the time this book is published my view of the Soviet regime may be the generally accepted one. But what use would that be in itself? To exchange one orthodoxy for another is not necessarily an advance. The enemy is the gramophone mind, whether or not one agrees with the record that is being played at the moment.

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech—the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of 400 years has been founded on the opposite notice. For quite a decade past I have believed that the existing Russian regime is a mainly evil thing, and claim the right to say so, in spite of the fact that we are allies with the U.S.S.R. in a war which I want to see won. If I had to choose a text to justify myself, I should choose the line from Milton: “By the known rules of ancient liberty.”

The word ancient emphasizes the fact that intellectual freedom is a deep‐rooted tradition without which our characteristic Western culture could only doubtfully exist. From that tradition many of our intellectuals are visibly turning away. They have accepted the principle that a book should be published or suppressed, praised or damned, not on its merits but according to political expediency.

And others who do not actually hold this view assent to it from sheer cowardice. An example of this is the failure of the numerous and vocal English pacifists to raise their voices against the prevalent worship of Russian militarism. According to these pacifists, all violence is evil, and they have urged us at every stage of the war to give in or at least to make a compromise peace. But how many of them have ever suggested that war is also evil when it is waged by the Red Army? Apparently the Russians have a right to defend themselves, whereas for us to do so is a deadly sin. One can explain this contradiction in only one way—that is, by a cowardly desire to keep in with the bulk of the intelligentsia, whose patriotism is directed toward the U.S.S.R. rather than toward Britain.

I know that the English intelligentsia have plenty of reason for their timidity and dishonesty; indeed, I know by heart the arguments by which they justify themselves. But at least let us have no more nonsense about defending liberty against fascism. If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear. The common people still vaguely subscribe to that doctrine and act on it. In our country—it is not the same in all countries: it was not so in Republican France, and it is not so in the United States today—it is the liberals who fear liberty and the intellectuals who want to do dirt on the intellect: it is to draw attention to that fact I have written this preface.

You don't need an elaborate theory to be appalled by the murder of thousands of innocent people, regardless of which side is doing it.