Two things I'd like to fix: scaling 'what works' and democracy

And other great things I found on the net this week

Two things I’d like to fix: scaling 'what works' and democracy

In this podcast I got two wishes. What two things would I fix if I could. Chris Vanstone from The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) asked to interview me as part of TACSI's thinking about its own future. I agreed but made two suggestions. First, that we record the discussion and make it a podcast.

Second, given his description of the process as exploring “what futures do you want to see”, I said that I'd expect to critique that as a starting point right off the bat. Why? Because this kind of framing suffers from grandiosity. I'm not some hero charting a course to the future. I'm a little munchkin noticing things, trying to figure out what problems and opportunities exist in what Humphrey Bogart called our "crazy mixed up woild" in Casablanca.

The ensuing session was really engaging I thought. Kudos to Chris for being an unfazed master of silence while he thinks. Oh, and the two things I want to fix?

We talk as if we'll scale up social programs that work and scale down the less successful ones. But we haven't done it since, now let me see. Since … Well ever actually! And that's the case in most countries.

Oh and democracy — I want to fix that (and this'll make you laugh) I don't think it's that hard! I think we just need to introduce jury-like mechanisms into our democracy. If you're interested, have a look at the trailers for this documentary.

If you'd like to listen to the audio of this podcast, it’s here.

Ned Morgan rides again

Bob Solow: 99 and counting

A marvellous interview of Bob Solow who is about my favourite economist, and I think was my father’s, not least for his jokes. My wife Eva is not, to put it mildly, particularly interested in economics, nor, if the truth be told, most (possibly all) economists. Her response to this podcast? “WHAT A CUTIE!”.

If you want to read his very funny review of J. K. Galbraith’s New Industrial State, it’s here. It’s jokes are still funny, though I doubt he’d be quite so dismissive with the benefit of hindsight. This is how it starts:

More than once in the course of his new book, Professor Galbraith takes the trouble to explain to hist reader why its messagewill not be enthusiastically received by other economists. Sloth, stupidity, and vested interest in ancient ideas all play a part, perhaps also a wish - natural even in tourist-class passengers - not to rock the boat. Professor Galbraith is too modest to mention yet another reason, a sort of jealousy, but I think it is a real factor. Galbraith is, after all, something special. His books are not only widely read, but actually enjoyed. He is a public figure of some significance; he shares with William McChesney Martin the power to shake stock prices by simply uttering nonsense. He is known and attended to all over the world. He mingles with the Beautiful People; for all I know, he may actually be a Beautiful Person himself. It is no wonder that the pedestrian economist feels for him an uneasy mixture of envy and disdain.

And here’s my favourite passage which I’m happy to take as a kind of credo. You’ll detect the same hesitancy about overconfidence and ideological excess.

There is a long-standing tension in economics between belief in the advantages of the market mechanism and awareness of its imperfections. . . . There is a large element of Rorschach test in the way each of us responds to this tension. Some of us see the Smithian virtues as a needle in a haystack, as an island of measure zero in a sea of imperfections. Others see all the potential sources of market failure as so many fleas on the thick hide of an ox, requiring only an occasional flick of the tail to be brushed away. A hopeless eclectic without any strength of character, like me, has a terrible time of it. If I may invoke the name of two of my most awesome predecessors as President of this 1 Association, I need only listen to Milton Friedman talk for a minute and my mind floods with thoughts of increasing returns to scale, oligopolistic interdependence, consumer ignorance, environmental pollution, intergenerational inequality, and on and on. There is almost no cure for it, except to listen for a minute to John Kenneth Galbraith, in which case all I can think of are the discipline of competition, the large number of substitutes for any commodity, the stupidities of regulation, the Pareto optimality of Walrasian equilibrium, the importance of decentralizing decision making to where the knowledge is, and on and on. Sometimes I think it is only my weakness of character that keeps me from making obvious errors.

Be that as it may, Bob Solow has just done an interview with Steven Levitt — he of Freakonomical fame and it’s marvellous. Highly recommended for all comers, not just economists. He’s referred to as 98, but he’s since turned 99. On Aug 23rd.

New feature: the two minute hate

Dani Rodrik: speaking sense about trade

Dani Rodrik spoke sense about trade when all about him were losing theirs. (OK that last set of words wasn’t a sentence, but you can blame Rudyard Kipling for that. My point is that Rodrik’s been making sense on the subject of trade while most other people have treated it as a high class culture war.

“Free trade” conjures an image of governments stepping back to allow markets to determine economic outcomes on their own. But any market economy requires rules and regulations – product standards; controls on anticompetitive business conduct; consumer, labor, and environmental safeguards; lender-of-last-resort and financial-stability functions – which are typically promulgated and enforced by governments. …

Viewed in this light, it becomes clear that hyper-globalization – which lasted roughly from the early 1990s until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic – was not a period of free trade in the traditional sense. The trade agreements signed over the past 30 years were not so much about removing cross-border restrictions on trade and investment as they were about regulatory standards, health and safety rules, investment, banking and finance, intellectual property (IP), labor, the environment, and many other issues that previously lay in the domain of domestic policy.

Nor were these rules neutral. They tended to prioritize the interests of politically connected big businesses, such as international banks, pharmaceutical companies, and multinational corporations, over all else. These businesses not only got better access to markets globally; they also were the primary beneficiaries of special international arbitration procedures to reverse government regulations that reduced their profits.

Similarly, tighter IP rules – which allow pharmaceutical and tech companies to abuse their monopoly positions – were smuggled in under the guise of freer trade. Governments were pushed to free up capital flows, while labor remained trapped behind borders. Climate change and public health were neglected, partly because the hyper-globalization agenda crowded them out, but also because the creation of public goods in either domain would have undercut business interests. In recent years, we have witnessed a backlash against these policies, as well as a broad reconsideration of economic priorities more generally.

What some decry as protectionism and mercantilism is really a rebalancing toward addressing important national issues such as labor displacement, left-behind regions, the climate transition, and public health. This process is necessary both to heal the social and environmental damage done under hyper-globalization, and to establish a healthier form of globalization for the future.

Musk: you wouldn’t read about it

Brought to you by fruitcake watch ®

Well actually you would read about it. That’s why you’re reading this right?

I’ve steered clear of Walter Isaacson’s tomes because of reviews like this, but sometimes the reviews are fun.

“Who or what is to blame for Elon Musk? Famed biographer of intellectually muscular men Walter Isaacson’s dull, insight-free doorstop of a book casts a wide but porous net in search of an answer. Throughout the tome, Musk’s confidantes, co-workers, ex-wives and girlfriends present a DSM-5’s worth of psychiatric and other theories for the ‘demon moods’ that darken the lives of his subordinates, and increasingly the rest of us, among them bipolar disorder, OCD, and the form of autism formerly known as Asperger’s.

But the idea that any of these conditions are what makes Musk an ‘asshole’ (another frequently used descriptor of him in the book), while also making him successful in his many pursuits, is an insult to all those affected by them who manage to change the world without leaving a trail of wounded people, failing social networks and general despair behind them.

The answer then must lie elsewhere. There’s a lot to work with here, but it doesn’t make reading this book any easier. Isaacson comes from the ‘his eyes lit up’ school of cliched writing, the rest of his prose workmanlike bordering on AI. I drove my espresso machine hard into the night to survive both craft and subject matter … To his credit, Isaacson is a master at chapter breaks, pausing the narrative when one of Musk’s rockets explodes or he gets someone pregnant, and then rewarding the reader with a series of photographs that assuages the boredom until the next descent into his protagonist’s wild but oddly predictable life.

Again, it’s not all the author’s fault. To go from Einstein to Musk in only five volumes is surely an indication that humanity isn’t sending Isaacson its best … There is a far more interesting book shadowing this one about the way our society has ceded its prerogatives to the Musks of the world. There’s a lot to be said for Musk’s tenacity, for example his ability to break through Nasa’s cost-plus bureaucracy. But is it worth it when your savior turns out to be the world’s loudest crank? … there’s a whiff of desperate masculinity floating through the book, as rank as a Pretoria boys’ locker room … When you are as messed up as our hero, there is a lot of psychological work to be done to stop the downward spiral, work more boring than building a rocket. Work even more boring than this book.”

–Gary Shteyngart on Walter Isaacson’s Elon Musk (The Guardian)

BMW rejects Kant’s categorical imperative: SHOCK!!

The Two-Parent Privilege

Alice Evans’ high signal to noise review of “The Two-Parent Privilege” - a new book by Professor Melissa Kearney

[The book] advances 10 key claims. Let’s assess!

Single motherhood is rising, primarily amongst women with less education.

Children of single mothers (especially sons) have lower social mobility. They are more likely to remain in poverty and less likely to graduate from college.

If we care about poverty and inequality, this discussion is entirely legitimate. It needn’t imply shame or stigma.

Economics partly explains the decline in marriage. If working class men lack decent jobs and earn little more than poor women, they become less attractive grooms.

Culture also matters. Even when male wages increased during a fracking boom, marriage rates remained low.

Financial resources, supportive parenting, reading together, and warmth confer massive inter-generational benefits. In all four respects, single mothers are disadvantaged. Shattered and stressed, they struggle to match “the two parent privilege”.

Boys are especially sensitive to parental inputs (Bertrand & Pan).

Kids do better when they have a more nurturing environment and better schooling - which could be achieved via greater government investment.

Fertility is down not due to economics, but a shift in cultural priorities. An MTV show on teenage mums made girls much more averse!

I agree with all 9 claims above, but not the 10th…

Some interested thoughts on Elon

Greg Clark on assortative mating, genetics, social mobility and whether social policy works.

I remember happening upon Greg Clark giving a lecture at Melbourne University in the wake of his big book Farewell to Alms. Because my bullshit meter spends most of its time set to ‘very sensitive’ (unless I’m watching my team’s coach Craig McCrae’s post match presser) I had intuited from the fact that the book was the flavour of the month in the blogging scene that this was some academic who’d written a trade book to popularise his work which seemed a bit one dimensional — on the theme of the role of genetics in history.

Anyway, I went along and was pleased to find out how wrong my priors were (which is, I regret to inform you dear reader, about the most fun I ever have.) His lecture summarised what seemed like about twenty years of research and though I can’t vouch for it as if I’ve checked it out carefully, seemed to make some pretty powerful (and depressingly fatalist) points on the importance of genetics in social outcomes.

Anyway, this is a radioactive subject — and there are lots of people I’d be steering well clear of on the subject — but somehow his manner and what seemed to be the painstaking nature of his research meant that I was good with it. And who else names each of his major research outputs to be some lame spoof of Hemmingway’s titles. The first was Farewell to Alms. The next, The Son also rises. And now Ask not for whom the bell curve tolls.

Anyway, I recommend the podcast which is here.

Some pronounced weirdness

In this world of opinion formation by spectacle, here are two spectacles I send your way. The first is this video.

The second is the video in this tweet. We must all make of these two videos what we will. Perhaps the person in the first video is on an extreme anti-trans campaign. Who am I to say?

Boys’ and girls’ reading: Amazing graph

Anne Boleyn: the French connection

There’s more than meets the eye — even if what meets the eye was, by all accounts, an important part of the story!

From a review of Hunting the Falcon: Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and the Marriage That Shook Europe, By John Guy & Julia Fox

Guy and Fox have ransacked the French archives to far greater effect than is usual in our traditionally Anglocentric approach to history. … Anne Boleyn spent seven formative teenage years in France. … The lessons she learned in France shaped the woman who returned to England, besides forming part of her attraction to Henry. In France, she observed the centuries-old game of courtly love, with all its perils, and, even more importantly, the movement sponsored by the French royal ladies to reform a corrupt and overly ritualistic Catholic Church. Even though France, unlike England, recognised the Salic Law, forbidding women from ascending the throne, she was witness there to a far stronger tradition of women exercising influence and even power than existed across the Channel.

Those years also made Anne a lifelong Francophile, a vital fact given the tug of war that was European politics in the 16th century. … Henry’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon, was identified above all by her Spanish ancestry; she served effectively and at times even literally as Spain’s ambassador in England. Just as her star began to fade, with the end of her years of fertility and her chances of giving Henry a male heir, England’s alliance with her imperial relations fell into jeopardy. Surprisingly, Anne Boleyn – the daughter of an English gentleman and an English noblewoman – was able to provide a counterweight. So thoroughly had she absorbed the culture of France that she could be presented almost as France’s representative in England. Her ‘addiction to all things French’, as the authors call it, framed the ways in which ‘she wanted to change England’. Anne and Henry’s prenuptial visit to Calais in October 1532 saw the French king, Francis I, seemingly give his blessing to their marriage. …

Anne’s role on this European stage has long been almost ignored, save for the innuendo-laden suggestion that her naughty, Frenchified ways held Henry in thrall. But Guy and Fox foreground her placement here and both the advantages and the perils that it brought. … Her reorganisation of her court along French patterns, with its freer association of men and women, paved the way for the accusations of adultery made against her. Her Francophilia did her no favours with the notoriously Francophobic English people. …

Their years together, after all, saw Henry change from the idealistic young golden king into, as the authors put it, ‘a narcissist who saw exercising control as his birthright’. Henry went from someone who apparently contemplated giving Anne a kind of joint sovereignty to someone who never really trusted or respected women again and who confronted any challenge with ‘a wall of anger’. …It would be pointless to cite here all of Guy and Fox’s discoveries. Taken individually, they may not seem spectacular to non-specialist readers. Yet the pace and conviction of the story the authors tell will carry them along. In many places, where once we had speculation, we now have certainty. This book is at once an education and a joy to read.

Peter Martin, Phil Lowe and the gravy train

Peter Martin has implored Phil Lowe not to line his pockets by joining the board of an Australian bank — like so many of his predecessor bureaucrats did — including former RBA Governors Glenn Stevens, Ian Macfarlane and former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry. Quite. And good on Martin Parkinson who, as far as I know has kept himself to higher standards.

Gus O’Donell, formerly the most senior civil servant in the UK (in which role he was universally referred to by way of the acronym GOD) took on a role with a financial institution, but it as as “a strategic adviser to the chief executive of Toronto Dominion Bank”, not a board member of a major British bank.

Note the indecent speed with which Lowe’s forebears have taken up cushy positions in the companies whose fates hung on their previous decisions as bureaucrats.

Philip Lowe’s predecessor, the man to whom he was deputy, Glenn Stevens, finished up as Reserve Bank Governor in September 2016 and joined the board of the Macquarie Bank and Macquarie Group in December 2017. He has been chair of Macquarie Bank and Macquarie Group since 2022.

Stevens’ predecessor as governor, Ian Macfarlane, finished as head of the Reserve Bank in September 2006 and joined the board of the ANZ bank in February 2007.

The governor he replaced, Bernie Fraser, finished at the Reserve Bank in September 1996 and joined the board of the industry funds that became Australian Super in the same year, becoming chair of the super-fund-owned ME Bank in 2000.

Ken Henry stepped down as head of the Australian Treasury (and a member of the Reserve Bank board) in April 2011 and in November that year joined the board of the National Australia Bank. In 2015 he was made its chair.

The man Henry replaced at the Treasury, Ted Evans, stepped down in April 2001 and joined the board of Westpac that year, becoming its chair in 2007.

I’ve dealt with each of these people while they were governors or treasury secretaries and I’ve never seen anything that made me doubt their integrity.

And yet in my view, none of them should have gone on to work for the type of organisations they used to regulate.

I expect Philip to do the right thing, unlike those that have come before him.

Three minute maestro

This is a bullet chess masterpiece from Magnus Carlsen. He and his opponent had 1 second a move plus one minute for the entire game! The quality of the game would have beaten pretty much anyone in a classical game. Is Magnus that good. Well, no. His blink of an eye judgements worked out. But that wasn’t the only game of that quality he played in this encounter. Both commentators are grandmasters. One is very strong.

Extract from Crack-up capitalism

Your Own Private Liechtenstein

Quinn Slobodian first book on neoliberalism, The Globalists, took me by surprise. Previous books I’ve read have tended to detail the development of neoliberal doctrine and frame the whole thing as the story of intellectual entrepreneurialism as if the folks at universities play nice and try to influence the world by persuading it. In this model of the world Hayek sets up the Mont Pèlerin Society the meetings of which are confidential and then gradually pieces together the allies to found and fund think tanks.

True, it’s all a bit dodgy watching their views transform themselves in line with their funding. Thus, once they started raising money from Standard Oil, the Chicago School suddenly got less keen on vigorous anti-trust. But The Globalists shows you how much more ambitious they really were. And it let’s you see how clever and effective it was for them to influence the ambitions, the purposes and the contents of international agreements.

Reading The Globalists it seems the neoliberals were very influential in getting Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) written into international agreements. ISDS clauses impose on host governments obligations to gerry built corporate judicial systems other than their own. Australia was taken before one by the tobacco lobby for having the temerity to regulate cigarette packaging.

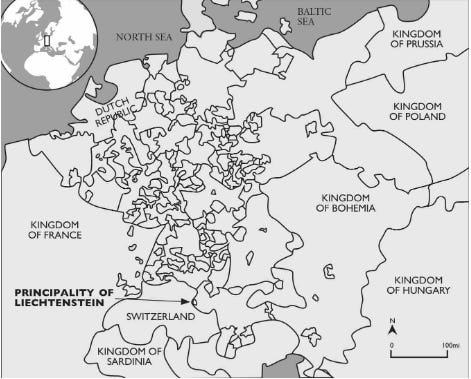

Anyway, Slobodian’s next book is Crack-up Capitalism — the remarkable story of the power of the idea of zones. Zones designed to attract capital and which thus stand outside standard national legal, regulatory and/or tax law. It’s a powerful idea and of course it’s being exploited by the powerful. Here’s an extract — the chapter on Liechtenstein.

It’s been said that if you light a cigarette when you enter Liechtenstein on the highway from Switzerland, you’ll still be smoking it when you cross into Austria.1 The principality is about the length of Manhattan, a craggy green valley along the river Rhine. It seems an unlikely place to offer a template for political organization for the twenty-first century. Yet despite—and because of—its miniature size, the aura of the principality shines bright in the libertarian mind. In 1985, the Wall Street Journal called Liechtenstein “the supply-siders’ Lilliputian lab.” The year after, Leon Louw and Frances Kendall used it to argue for cantonization in apartheid South Africa. Radical libertarians celebrate it as the “first draft” of a state designed as a service provider with citizens as customers, and dream about “a world of a thousand Liechtensteins.”

Among its virtues is the presence of a resident libertarian theorist. Prince Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein, the world’s fourth-wealthiest monarch, with a net worth of over $2 billion, has offered himself as a tribune for the cause, sketching blueprints for what he calls “the state in the third millennium”—an alternative globalism based on secrecy, autocracy, and the right of secession. To some market radicals, this last bit of confetti from the Holy Roman Empire is the preview of a potential coming future.

1.

The charm of Liechtenstein begins with its origins: it was bought for cash. At the beginning of the 1700s, a member of the Viennese court purchased two stretches of land from the bankrupt Hohenems dynasty and melded them into a single principality. The territory was rechristened with the surname of its new owners. Becoming a fully sovereign state in 1806, Liechtenstein was part of the German Confederation until that confederation dissolved in the middle of the century, after which it came under the umbrella of the Hapsburg Empire. Neither the principality’s original buyer nor any of his heirs lived there; until 1842, none even visited it. They enjoyed diplomatic immunity in Vienna, four hundred miles away. Liechtenstein was just one of their many properties, strewn across what was still the aristocratic patchwork of central Europe.

When the Hapsburg Empire broke up after its defeat in the First World War, Liechtenstein affiliated itself with Switzerland. Austrian currency, made worthless by hyperinflation, was ditched for the Swiss franc, which became legal tender in the microstate in 1924. The war dealt a blow to the House of Liechtenstein: most of its scattered properties lay in what became the new state of Czechoslovakia, which followed a policy of economic nationalism and expropriated foreign-owned holdings. The princely family lost more than half its land, with compensation at what they reckoned was a fraction of the true value. Liechtenstein’s application to join the League of Nations was rejected in 1920, but the microstate still had its sovereignty and sought ways to make use of it. Ideas for a lottery and a horse-betting operation surfaced and vanished, as did a proposal to launch an extranational currency unit known as the globo. Plans to mimic Monaco and become an alpine Monte Carlo also came to naught. In the end, Liechtenstein chose instead to become something that did not yet properly have a name: a tax haven.

The central institution of the tax haven is the trust. Invented in England, the trust dates back to the time of the Crusades, when people departing to fight in the Holy Wars sought to leave their property in the hands of a confidant. In the medieval and early modern period, putting land in trust with friends or living relatives was a way to avoid it being confiscated upon their death by authorities or tax collectors. They were a means of asserting the power of elites against the rise of tax-collecting rulers. Into the twentieth century, they have filled a similar purpose. The sociologist Brooke Harrington has shown how trust and estate professionals adopted some of the code of earlier knights, bound by personal ties that float above and beyond the confines of terrestrial nation-states. For centuries the heart of the profession was the City of London, but the introduction of income tax in many countries around the time of the First World War created more incentive for secreting away personal wealth, and companies whose businesses were fragmented among the newly created states looked for a single seat of incorporation. Liechtenstein and Switzerland stepped in to fill the gap.

Liechtenstein’s status as a remnant of the premodern feudal system made the posture of chivalrous keeper of secrets all the more convincing. In 1920, a multinational consortium created a new bank there. The same year, the first holding company was created. In 1926, the microstate passed a law that allowed foreign companies to act as if they were domiciled in the mountain valley. All that was required was having a local lawyer act as your agent. In the eyes of the tax collector, their residence became your residence. The number of registered companies quadrupled within a few years, rising to around twelve hundred in 1932; by the early twenty-first century, there would be seventy-five thousand of them. Accounts were anonymous, registration could be in any language, the shares could be denominated in any currency, and all the subsidiaries of the mother company would be covered anywhere in the world. One of the enduring features of the Liechtenstein system is that a corporation could be made up of just a single person, their identity vanishing inside a legal black box. Liechtenstein’s trademark offering was the Anstalt, originally developed in Austria as a type of foundation for charitable purposes. Liechtenstein adapted it as a way to shield family fortunes from inheritance taxes.

“Considered as a country,” a journalist wrote in 1938, “Liechtenstein is much too small to be independent. But considered as a safe it is a very large one, practically the largest one ever built.” The quaint streets of Liechtenstein’s capital, Vaduz, with a population of a few thousand, were lined with the corporate offices of the world’s largest companies, including IG Farben, Thyssen, and Standard Oil. Liechtenstein also debuted another practice beloved of the superrich: letting them buy citizenship. In 1938, the price was $5,500. (Adjusted for inflation, this is about $110,000 in today’s money—similar to the current entry level for naturalization “by investment” in countries like Vanuatu and Grenada.) Most of the newly minted Liechtensteiners did not stay. They drove in, took the oath of citizenship, and drove away. Liechtenstein became known as “the capital of capital in flight.”

In 1938, Liechtenstein’s monarch took up residence in the principality itself for the first time, as Prince Franz-Josef II fled the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. By an agreement whose terms remain opaque, the country was left untouched by German forces. There was a small domestic Nazi movement, and Hitler sympathizers were allowed in the fifteen-person parliament, but a slightly comical attempt at a putsch was put down with the aid of Boy Scouts. An international commission of historians later found that although forced laborers were used on lands owned by the royal family in Austria, Liechtenstein—unlike its neighboring Switzerland—did not traffic in gold or art stolen from Jews.

After the war, Liechtenstein continued to develop its status as an “Eden for nervous capitalists.” The 1950s saw the expansion and extension of the offshore world, as more corporations sought to escape taxation by creating holding companies outside the country they operated in. By 1954, Liechtenstein had between six thousand and seven thousand holding companies, including a subsidiary of Ford, alongside other companies disguised behind made-up names like Up and Down Trading Corporation. As one trustee explained, someone showing up with a briefcase full of cash would be given a range of options for placing it in an account either personally or through a nominee. A charter was needed, but it only had to include the company’s name, the date of incorporation, and the name of the nominee; an annual meeting was required, but it could be held by your nominee—and could be a meeting of one. As with the famous numbered bank accounts of Switzerland, secrecy was what was being paid for—a bolt-hole beyond the sight of the expanding postwar state. “Swiss bankers keep their lips sealed,” a saying went, “but the Liechtenstein bankers don’t even have tongues.”

The era from the early 1970s to the late 1990s were the “golden years” for tax havens. Liechtenstein was joined by others, including Bermuda, the Bahamas, and, above all, the Cayman Islands. By the late 1970s, Liechtenstein hosted more companies than citizens and boasted a GDP per capita second only to Kuwait. Alongside its regular corporate clients were some shadier ones. In the 1960s, the CIA used Liechtenstein to register front organizations for its covert involvement in the civil war in the Congo. (The generic name of its holding company was Western International Ground Maintenance Organization.) A few decades later, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions accused Liechtenstein of facilitating investments into apartheid South Africa. An Austrian company built a plant in South Africa through an anonymous Liechtenstein subsidiary, while a British business selling asbestos sourced from South African mines to the United States used a Liechtenstein shell company to avoid sanctions.

As for individuals with Liechtenstein connections, they included the Nigerian military ruler Sani Abacha as well as the newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell, who siphoned his employees’ pensions into a secret account in Liechtenstein. Intelligence reports also linked the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar and the Zairean dictator Mobuto Sese Seko to banks of the microstate. Even more prominent were Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, who used Liechtenstein trusts to stash away some of their embezzled fortune, estimated at $1–$5 billion. (When they wanted money, they would send the phrase Happy Birthday to their Swiss banker, who would retrieve cash from Liechtenstein and then contact their agent in Hong Kong for delivery to Manila.) Another notable client was the Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, whose lavish holiday residence was technically owned by a company in the tony London neighborhood of Fitzrovia, which was, in turn, owned by P&A Corporate Services Trust of Vaduz. Liechtenstein was a portal to “Moneyland,” as one journalist put it, a domain beyond tax-collecting states.

Liechtenstein did not put all its energies into what was tactfully called wealth management. As an early commentator put it, even though Liechtenstein’s taxes and fees were very low, there was more than enough gold dust to float up and coat the small country. Wealth gained through its novel status as a tax shelter let it move into industrialization. By the 1980s, Liechtenstein was one of the most industrialized nations in the world, with factories manufacturing products ranging from fake teeth to central heating plants. It went from exporting laborers as farmhands to importing them as factory workers. Over half its workforce commuted from neighboring countries—with no chance of naturalization.

Citizenship was governed by a radical spirit of communitarianism. After they ended their early practice of selling passports, the only way to become a citizen was by approval from community members voting via secret ballot, followed by approval from the parliament and the prince. So few ever made it through that most did not even try. As the number of corporations registered in the country soared into five digits, the number of immigrants per year averaged only a couple of dozen. Liechtenstein was applying its version of the Singapore Solution: a microstate with maximal openness to capital and closed borders for new citizens. It was a land both of the future and of the past: women did not have the right to vote until 1984.

2.

Liechtenstein is usually treated as a curiosity—a fairy-tale kingdom in the heart of Old Europe. What made it part of the libertarian war of ideas was the adventurous ideological entrepreneurship of Prince Hans-Adam II. Born in 1945 and baptized as Johannes Adam Pius Ferdinand Alois Josef Maria Marko d’Aviano von und zu Liechtenstein, Hans-Adam was the first monarch to be raised in the territory. After working briefly in a London bank and interning at the US Congress, he attended business school in St. Gallen, an hour’s drive north of Vaduz. The country was still poor enough in the 1960s that Hans-Adam’s father sold a Leonardo da Vinci painting from their collection to the National Gallery in DC, in part to pay for his son’s lavish wedding. Hans-Adam recalled being educated in an era that taught that “the bigger, the better.” Smaller nations seemed destined to be swallowed by one of the two feuding Cold War camps. Liechtenstein’s lack of even its own seat in the United Nations made Hans-Adam wonder if he was being set up for failure.

Given supervision of the country’s finances in 1970 and taking over duties from his father as regent in 1984, Hans-Adam was described as “the technological age’s manager-prince,” bringing his business school mentality to the task of government. Worried that Liechtenstein was being lapped by other tax havens like Panama and the Channel Islands, he set up branch offices in Zurich, Frankfurt, and New York City, and increased the number of the country’s banks from three to fifteen. Assets under management tripled in the mid-1980s. He also went on a charm offensive. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted a blockbuster show of pieces from the princely collection. The principality’s fairy-tale air was only enhanced by the 3,100-pound golden stagecoach on display in the exhibition.

Another one of the prince’s goals was reversing the embarrassment of rejection from the League of Nations and earning a seat in the UN, which succeeded in September 1990. In his first address from the floor of the General Assembly, Hans-Adam did not follow tradition by delivering bromides about international cooperation. Instead, he made an astonishing argument: that all nations were ephemeral and should remain open to the possibility of their imminent dissolution. States cannot live forever, he argued. They have “life cycles similar to the human beings who created them.” Extending their life spans could sometimes end up causing more violence than letting them peacefully die. To cling too tightly to the existing configuration was “to freeze human evolution.” Borders themselves were arbitrary—“the product of colonial expansion, international treaties or war and very seldom have people been asked where they want to belong.”

Such proclamations verged on the scandalous as breakaway movements threatened national crack-ups from Quebec to Belgium to Belgrade. The UN had a formal policy against secession and discouraged minorities inside existing nation-states from seeking independence. But the mood was changing as Hans-Adam spoke. The Soviet Union’s stepwise dissolution seemed to be showing that peaceful disintegration was possible. In his address, the prince welcomed the Baltic states Latvia and Estonia, which entered the UN at the same time as the microstate. He also welcomed both North and South Korea as new members. The Cold War’s end was allowing for the recognition of multiple claims on a single people along with a surge of new nations.

The prince proposed that the way to help rather than hinder human evolution was to create a means for continuous churning of the world map. This would happen through referendums. Such a rearrangement could move by stages, devolving first responsibilities for local affairs and taxation; but if that did not satisfy a population, it could go all the way to the splitting of a state into two or more new entities. The idea originated in a parlor game that Hans-Adam’s family used to play: speculating about how their erstwhile patron and protector, the Hapsburg Empire, might have survived. Hans-Adam believed that it could have happened if the empire had allowed for the proliferation of smaller self-determining units—a decentralization within a loose union to save the interdependent whole. He thought the model was just as valid a century later. The high-pressure system of globalization could only preserve the all-important economic unity if polities were given the option of splitting into fragments.

Hans-Adam cross-fertilized the Holy Roman Empire’s model of aristocratic state ownership, which had given rise to Liechtenstein itself, with the fluid idea of sovereignty represented by the global clients of Liechtenstein’s banks. Those corporations’ tangle of overseas subsidiaries and shell companies suggested that sovereignty could be unbundled, relocated, and recombined. Hans-Adam’s own family had ruled Liechtenstein from afar for centuries. Why shouldn’t the modern state also be a “service provider,” where all capacities except for national defense were contracted out to private actors? This was an opt-in, opt-out vision of citizenship, explicitly designed as an analogue to the marketplace. The people, he wrote, should be “the shareholders of the state.”

The conclusion of the First World War had enshrined the idea of Wilsonian self-determination, usually understood as based on a common language, common territory, and common history. This was the justification by which Czechoslovakia had expropriated his family’s properties. Hans-Adam countered that a nation should not be premised on a transcendent idea of the state as a bearer of an ineffable essence, or even of a community of shared fate. He preached instead a premodern idea of statehood. It was nebulous, open to adaptation, even—as his own state showed—open to purchase and sale. Liechtenstein set itself up as the international champion of the contractual communities that people like Murray Rothbard dreamed of. Given a pulpit at the UN, Hans-Adam espoused a libertarian blueprint for what he called “the state in the third millennium,” or what Rothbard called “nations by consent.” It was anarcho-capitalism by way of the Alps.

The prince practiced what he preached, bringing his version of self-determination into his own country. In the year 2000, a red booklet arrived in the mailboxes of every citizen in Liechtenstein with Hans-Adam’s proposed revision to the constitution. The proposal greatly increased the prince’s power, giving him the right to put forward and veto bills, dissolve parliament, and enact emergency laws. It also included something remarkable: a nuclear option that permitted the population to hold a referendum to abolish the monarchy itself. And true to Hans-Adam’s UN speech, the proposal permitted any of Liechtenstein’s eleven communes to secede after a majority vote (while reserving the right for the prince to order a second vote). The clause was watered down from the prince’s original version, which included the possibility of individuals to secede without the need for approval from the parliament or the prince. When members of the parliament balked at what was called a “princely power grab,” Hans-Adam showed he was serious about his transactional relationship to the territory. He suggested he would be happy to sell the country to Bill Gates and rename it Microsoft if the constitutional reform did not go his way. “My ancestors bailed out Liechtenstein when it was bankrupt and thus acquired sovereign rights,” he told the New York Times. “If ever the people decided time is up for this ruling family, they would have to find someone else rich enough to take our place.”

The prince had no intention of letting go of his investment cheap—but finding someone as rich as he would have been a tall order. The House of Liechtenstein was wealthier than the House of Windsor. The proposed constitutional revision passed in 2003, making Hans-Adam Europe’s “only absolute monarch” but also the only one building in a constitutional exit from the monarchy and the country itself. The combination was odd, out of step with the times. There was talk of Liechtenstein being ejected from the Council of Europe. But the confrontation with parliament meant that Hans-Adam’s model had passed its stress test. The next year, the “tycoon-monarch” passed the governing duties on to his son.

3.

Hans-Adam’s Liechtenstein was a combination of hereditary male autocracy and direct democracy chained to a dependency on capital hypermobility and secrecy. The Economist called it “democratic feudalism.” The prince’s hybrid version of medieval and modern politics sparked the imagination of libertarians in the 1990s and the first years of the twenty-first century, becoming an important touchstone for their criticism of European integration. Liechtenstein was the avatar of a different Europe and an alternative way of relating to the world economy. “Europe’s enclaves could be more than amusing anomalies,” wrote John Blundell (seen earlier as a champion of the homeland of Ciskei). “They could contain the seeds to subvert the European Union.” Specifically, critics argued that the European Union should follow Liechtenstein’s example by including a clause allowing for popular referendums to leave the union.

Underpinning the libertarian critique of the EU was a romanticizing of the continent’s earlier fragmentation. Historian Paul Johnson argued that “the so-called feudal system, often used as a synonym for backwardness, was in fact a series of ingenious devices to fill the power vacuum left by the fall of Rome.” “When the Roman Empire in the West disintegrated,” he wrote, “the ensuing Dark Ages saw state functions assumed by powerful private individuals or defensible cities.” A German economist proposed that “the European culture is the most successful in world history not despite but because it is fragmented into so many small countries that compete with one another.” Far from being impractical, the messy jumble of polities on the European peninsula dead-ending in the Atlantic was a source of strength. The ideal Europe was a “free market of states” with a common repository of rule of law and entrepreneurial spirit, a fractured assembly of sovereignties in a pool of shared culture.

This counternarrative turned the official history of European integration on its head. The sign of progress was not fusing sovereignties and decision-making and overlaying the continent with ever more shared laws and regulations. The arc of progress did not bend toward “ever closer union.” Rather, Europe had been on the path to greater liberty when it was politically fissured. Advocates of Brexit praised the success of Liechtenstein, Monaco, Luxembourg, Singapore, Hong Kong, and other small territories in the “age of the statelet.” Among the celebrants of medieval Europe was the founder of the Far Right party that would help win the Brexit vote. The fact that Liechtenstein was in the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) and European Economic Area (EEA) without joining the EU meant that it had free trade without free movement of people—another model of partial integration attractive to advocates of Brexit.

Hans-Adam II stood alongside other Euroskeptics. In 2013, he appeared at a gathering of neoliberals and nationalists with the economist Bernd Lucke, who had just founded the Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD), soon to become the first Far Right party to enter the Bundestag. The prince also became a member of the Hayek Society, which included key members of the AfD in its ranks. Another member of the House of Liechtenstein, Prince Michael, a wealth manager by profession, was the founder of the European Center of Austrian Economics Foundation, which translated Alvin Rabushka’s book on the flat tax into four languages.

Hans-Adam presented his argument about the state as service provider at the conference of the Ludwig von Mises Institute alongside people advocating the breakup of Switzerland and the European Union. The prince’s proposals bore a striking resemblance to those of the institute’s namesake, another child of central Europe and an icon for the libertarian Right. In a famous book from 1927, Mises had argued for secession by plebiscite and speculated on the possibility of the secession of the individual. In his regal style, Hans-Adam included references to no other thinkers in his writing, but the shared spirit of Mises connected his proposals to the ideas of Rothbard and the other paleo-libertarians across the Atlantic.

Part of the reason for libertarians to defend the Liechtenstein model was that the Liechtenstein model was under attack. Tax avoidance and money laundering, long allowed to proliferate unchecked, became politicized after the Cold War amid renewed concerns over drug trafficking, corruption, and, after 2001, terrorism. A first sign was a report on “harmful tax competition” published by the intergovernmental organization of the richer nations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in 1998. A task force set up by another club of the world’s most powerful nations, the G8, put Liechtenstein on a blacklist of fifteen “non-cooperative states” related to money laundering in 2000; it was the only one from Europe. The blacklisting dealt a blow to Liechtenstein’s reputation. A major leak in 2008—the first of a string that would include the Panama, Paradise, and Pandora Papers—showed that among those holding accounts in Liechtenstein through a trustee was a German dog named Günter. Financial institutions were forced to change regulations to cut back on the possibility of anonymous account holders. Liechtenstein’s primary bank lost nearly 10 percent of its assets as customers pulled out when they could no longer remain unknown.

The targeting of Liechtenstein did not dim its glamour for market radicals. On the contrary, it became possible to narrate the tax haven as a capitalist David fighting against a globalist regulatory Goliath. Paradoxically, a place that was among the wealthiest per capita in the world, tailor-made to protect the finances of the even wealthier, was cast as the underdog—a victim of “financial imperialism.” Hans-Adam led the defense, arguing that the OECD was threatening to develop into a global tax cartel and even a world government. Borrowing a line invented by Swiss bankers in the 1960s, he defended the origins of Liechtenstein’s bank secrecy as part of an effort to save persecuted Jews—an interpretation made doubtful by the fact that some of Hitler’s closest corporate allies, IG Farben and Thyssen, housed their corporations there years after the Nazi seizure of power. In an even more eyebrow-raising claim, the prince cast his country as the end station of an Underground Railroad for the superrich. “So long as you have tax pirates,” he said, “I don’t feel any moral guilt about being a tax haven just as people once took up slaves to help them escape their poor fate.” When the German government sought more insight into the internal workings of Liechtenstein’s banks, which were found to hold tens of millions of German accounts, he described it as the “Fourth Reich.”

4.

To libertarians, Liechtenstein looked like a wormhole back to an earlier form of global political economy, free of the treaties and international regulations that seemed to be tightening the noose around secrecy jurisdictions by the first decade of the twenty-first century, and the integration that libertarians feared would lead to redistribution and infringements on private property. Like Hong Kong and Singapore, it was a living example of the way things could be, premised on a globally interconnected world with no barriers to the movement of goods and money—a strip of rural land inserted almost invisibly into the circuitry of international finance, one of the “fragile islands of freedom” threatened by the expansion of the regulatory state. Recall that the end of the Cold War saw two apparently contradictory trends. On the one hand, there was greater economic interdependence, with globalization the buzzword on everyone’s lips. On the other hand, the political landscape was more fragmented than ever, as the UN tacitly opened up the possibility for something it had never accepted before: secession and nationalist movements by minority populations were now considered legitimate politics. The originality of Liechtenstein was its particular spin on this new form of politics. If new groups could make claims, then what if they began to make them as clients of services rather than as members of a national community?

There was something genuinely ideological about this vision of a world of tax havens that the mythology around Liechtenstein helps us to understand. It was not merely escape or exit in the negative sense but a fully formed philosophy of radical decentralization with secession as an ever-present option. The billionaire prince promoted his vision through the Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination, founded in Princeton with a $12 million gift, as well as the Liechtenstein Foundation for Self-Governance, which seeks to disseminate the country’s model abroad. The libertarian world pays attention. In 2018, the Ludwig von Mises Institute’s Jeff Deist praised “breakaway movements of the kind that Prince Hans of Liechtenstein is writing about, that government be rethought of as more of a service provider and subjects being thought of, or citizens being thought of, as customers.” A libertarian think tanker who helped blunt the OECD campaign against tax havens never fails to mention that the right to secede is enshrined in the Liechtenstein constitution. “Shouldn’t people in other nations have the same freedom?” he asks.

One person who took the rhetoric literally was Daniel Model, a corrugated packaging mogul and former curling champion. After moving from his native Switzerland to Liechtenstein, he went one step further, releasing a “declaration of sovereignty” that rejected membership in any human collective he had not expressly consented to and condemned democracy as a system of organized theft. Model declared his independent state Avalon, headquartered in a dove-gray mansion the size of a city block in a rural Swiss village. He drew its name from The Mists of Avalon, a fantasy novel written by Marion Zimmer Bradley that revisits the legends of King Arthur from the point of view of women. Avalon became Model’s own private Liechtenstein. In 2021, he hosted a conference called Liberty in Our Lifetime, devoted to finding places all around the world where one could escape the state. One of the speakers, who praised the Liechtenstein model of secession by referendum and designed his own scheme of “free private cities” with citizenship by contract, said that the attendees were driven by one question: “Are there possibilities to opt out?”

The search for such fantasy escapes took libertarians from Central London to East and Southeast Asia to European microstates. But sometimes they also went farther afield, seeking economic freedom in what they misidentified as the earth’s remaining empty lands.