Turning over a new leaf edition

And other fine things I was involved in or found on the net this week

Well in the great English speaking democracies, new leaves are being turned over, or perhaps they’re not. As Ezra Klein pointed out, the real secret of the previous situation in the US was that Trump and rapidly declining Biden were stupendously bad candidates. Get a half way decent one and who knows? Kamala is hardly the ideal candidate for the Dems, but so far she’s making the contest interesting.

Will Keir Starmer’s new government manage to change things sufficiently that people will look back on it and say, as some of us say of the first three quarters of the Hawke and Blair Governments, “that was how it is done”. If so, what are the lessons from then for now? I think one is to realise that parliament long ago ceased to be a clearing house of ideas. Rather it is a kind of crucible of negative energy.

Trying to repurpose this essay on the Hawke Government, I’d say the applicable lessons are that Starmer’s can be a transformative, truly good government if it is able to generate some sense of the community’s problems being solved in the community for transmission to parliament which is then tasked with not screwing things up. Thus under Hawke’s Accord, when the social partners (capital and labour) made deals to lift growth, the Opposition had little choice but to support it, as it reflected the hard work of their base — business.

I’m not suggesting Starmer get himself an accord, but if he follows the advice of Demos and Martin Wolf, be might be able to create the same kind of situation Hawke created in the glory days of the mid 1980s, which then gave him the political capital to get through a savage recession and win four terms in office!

Martin Wolf: involve citizens more in UK politics

Many things need to change, among them how the country governs itself

As you’d expect, I think this is a great column and agree that the Demos paper is excellent. As I noted on Substack when I read it:

Martin Wolf is my favourite neoliberal

Someone capable of backing what was good about it early on but also one capable of seeing its limitations, not just as an economic but also a political doctrine and then having something to say about what to do next. In this he is a great centrist liberal in the tradition of Raymond Aron and Michael Polanyi. Here's Daniel Mahoney on the point

Contemporary academic political theory, especially in the United States, is dominated by a largely sterile debate between liberals and communitarians. Academic liberals affirm the moral autonomy of the individual and the priority of rights over a commonly shared understanding of the good life. To a remarkable degree, they take for granted the moral preconditions of a free society--those habits, mores, and shared beliefs that allow for the responsible exercise of individual liberty. Raymond Aron's forceful retort to Hayek applies equally to other currents of academic liberal theory: they "presuppose, as already acquired, results which past philosophers considered as the primary objects of political action." Contemporary liberals fail to see that "a society must first be, before it can be free.

Over to Martin

The UK has a new government, with a huge majority. But only just over a third of the voters voted for it. Moreover, it has won power in a country that has lost confidence in democratic politics: recent polling for the independent think-tank, Demos, shows that “76 per cent of people have little or no trust that politicians will make decisions in the best interests of people in the UK”.

This is a crisis for democratic politics, not just for politicians. It is in such seas of distrust that demagogues ply their trade in scapegoats and falsehoods. …

In an excellent “Citizens’ White Paper”, Demos … states, “if government wants to be trusted by the people, it must itself start to trust the people.” The fundamental aim is to change the perception of government from something that politicians and bureaucrats do to us into an activity that involves not everyone, which is impossible, but ordinary people selected by lot. …

The idea is to select representative groups of ordinary people affected by policies into official discussion on problems and solutions. This could be at the level of central, devolved or local government. The participants would not just be asked for opinions, but be actively engaged in considering issues and shaping (though not making) decisions upon them.

Ambitiously, the paper outlines the following six steps for the next 100 days

announce flagship panels to feed into the government’s five mission boards (for growth, clean energy, crime, opportunity and the NHS);

create a standing pool of citizens from which mission boards and departments could draw;

create a hub of expertise on participation in government;

announce a programme of flagship citizens’ assemblies;

create levers for participatory policymaking within government, such as training and support;

and involve citizens in hearings by parliamentary select committees.

In the longer term, it suggests, there could be three more steps:

create a duty to consider participation;

involve citizens in scrutiny of past legislation; and

create an independent mechanism governing how all this might work.

This would evidently mark a large change in how government works. …

[T]here are powerful reasons why [this could improve things], all laid out in the paper. First, ordinary people have lived experience that ministers, civil servants and the normal range of experts will lack. …

Second, by debating on complex issues and interrogating expert witnesses, citizen bodies might reach a degree of consensus on hugely controversial issues, such as planning controls, “net zero”, prisons, immigration and assisted dying. …

Third and most important, the engagement of ordinary people could make the public feel that governance is no longer just done by remote figures, but is something in which people like themselves are also engaged. If we could credibly feel that today’s representative democracy is a huge success, none of this need be considered. But it is not. So it should be, now.

Reducing the temperature of politics?

Following the assassination attempt on Trump, the producer of Rory Stewart’s documentary series on ignorance asked me to participate in the Moral Maze’s episode on reducing the temperature of politics. Which I did. I had thought it was an hour long discussion with four people chosen for the episode joining four regulars. In fact each of the four newbies gets 11 minutes to be interrogated by the four regulars. Not an easy format in which to get one’s message across, but I did my best. My message? How citizens’ juries and like mechanisms can lower the temperature.

Did someone mention lowering the temperature?

9/10 for the diagnosis in this column, for suggesting that the polarisation we see around is rooted in discourse rather than economics. I include it because it’s rare that it is put as baldly as it is here. I’d put it less baldly perhaps, because there are important economic drivers, particularly intensifying locational disadvantage, but I think it’s more right than wrong. I start from the thought that the growing polarisation is pretty mysterious if we understand it as stemming principally from material causes.

Sadly the author has no idea what to do about the problem he so pungently diagnoses. Having identified the incentives within our political culture, he then defaults back to some bromides of American conservatism. Back to the constitution. What can be done about social media? No mention. Would greater use of sortition lower the temperature and change some incentives? No mention.

Stone-faced media pundits wonder if we’ve taken things too far; politicians put out press releases about how we must seek “unity” and “lower the temperature” of politics.

But as Peggy Noonan observed at the Wall Street Journal, it all seems so pro forma. Maybe there will be joint press conferences, a photo-op on the Capitol steps, or a brief period of respite from “fascist” talk. But will we get anything that’s beyond surface-level? To parse the metaphor, there is no wall thermostat to simply “turn down the temperature.” Calls to de-escalate are all to the good, but they are almost all focused on the epiphenomenal—the problem isn’t the rhetoric, per se. The problem is where the rhetoric comes from. That rhetoric is just part of a system of complex incentive structures that systematically poison political talk, ideas, and action.

One characteristic of today’s disease in the public mind is that it seems to be driven specifically by our political life—not by underlying social conditions. American society is not one that, on paper, should be seething with hatred. The tension in public life is not driven by a suppressed underclass groaning against oppression. There is no grand sectarian religious enmity. At a personal and local level, race relations have never been better. Religion, class, race, and a host of other elements, of course, all feature prominently in the cacophony that is public debate, but only after they have been fit into a larger national political narrative. Most Americans, even the extreme partisan agitators, honestly seem to care less and less about whether someone is black or white, an active Christian or an atheist, an East Coast elite or Midwestern farmer, so much as they care what kind of American you are, as the Internet meme goes. They care about the political “community” you are a part of, and what identity markers you embrace.

The vitriolic politics we practice is not feeding off already-simmering social tensions. It creates these identities and “communities,” most of which would not otherwise cohere on their own. Rather than managing and mitigating the tensions that naturally arise in any society, our political process actively generates new ones and calls forth the worst in human nature to bolster them. If there is to be a serious effort to make this moment a turning point—to tame the existential, “by-any-means-necessary” politics—it would require more than press releases or calls for a fabricated unity. It would require serious thought about our political practices and how they might change.

It may be impossible to say in advance what that sort of reflection would entail. But it would have to go beyond “taking a step back” or the other clichés and instead consider some deeply rooted qualities of our public life that incentivize the vitriol.

Which the author proceeds not to explore.

Me on Forecasting

Hopping into another Nobel Prize Winner

The world is full of Nobel Prize winners who end up a prisoner of their discipline. Even some of my favourite Nobels — like Paul Krugman, and in this case Ben Bernanke — are vast repositories of disciplinary knowledge and technical virtuosity within their discipline. But when it becomes necessary to have a slightly wider view to understand how blinkered their own discipline is? Well there aren’t many Nobel Prizes for that sadly. And that’s what’s needed here. I wrote this for the FT in the wake of Bernanke’s report, and they liked it but had already gone with Andy Haldane’s excellent piece on the same subject. Here it is on Evonomics.

By the mid 19th century, it was proven that hand-washing could slash hospital death rates. But it was water off a duck’s back to mid-19th-century surgeons. This was partly because it remained unexplained — indeed unexplainable — within the prevailing paradigm in which disease reflected an imbalance in the body’s four humours.

I thought of this reflecting on Ben Bernanke’s recent review of the Bank of England’s economic forecasting. As I argued last August, the Bank could dramatically improve the governance of forecasting by using open forecasting tournaments. Yet, the idea wasn’t even considered.

Economists are famed for their hubris, and their poor forecasting. In 1929, Prof. Irving Fisher famously forecast “a permanently high plateau” on Wall St. The Great Crash began within the week!

Following similar disasters after the 1973 oil price hike, the ‘Lucas critique’ shaped a new approach. Economists’ models had misforecast the economy because they were naïvely trained on data from a period when things were different — in this case when oil prices were far stabler.

Lucas’s answer was models that captured the structure of the economy. However, those models provide just one interpretation of economic structure and a radically simplified one at that. Their similarly dismal forecasting performance should have surprised no-one. But they surprised Lucas, who began by overestimating how much the problem could be tamed with updates to the economist’s technical toolbox and, like Fisher before him, then became wildly overconfident about the value of the result.

Good judgment is fundamental. Bernanke’s review discusses it, but its governance is a black box. Good judgement emerges from the back-and-forth between sound chaps within the Bank’s hallowed halls — he hopes.

So how do you find people with consistently good judgement and promote their status over the time-servers and the merely clever? As I know from chairing the data prediction platform Kaggle, neither their seniority nor their CV help. Though Dr Bernanke is probably an exception, you certainly don’t expect unusually good judgment from Nobel laureates in economics. Despite recent improvements, Nobels have mostly been awarded for cleverness, not usefulness. This was particularly so in the years during which Robert Lucas got his. There were quite a few others peddling similar wares.

Since the 1980s, psychologist Philip Tetlock has pioneered forecasting tournaments in numerous disciplines. Even to get them going, he had to pin forecasters down. Rather than tell us that some war, coup, or recession was “very likely,” he required them to nail down their percentage chances of being right, as weather forecasters do when telling us the chances of rain.

This gives us a far better evidence for sorting the also-rans from the ‘superforecasters’ who consistently outperform — like the superforecasters outperforming established economic forecasters right now in predicting the Fed’s funds rate.

So what distinguishes superforecasters? They master purely cognitive, technical tasks where necessary, but they are also generously endowed with broader, more ethical and social epistemic virtues. They tend to be cautious, humble, self-critical, actively curious and open to alternative views. These qualities are neither taught nor assessed in university courses in economics — or other subjects, for that matter.

However, forecasting tournaments can teach these qualities (as they generate better forecasts) because they relentlessly reward whatever forecasters do to make themselves more accurate and less overconfident. They provide excellent institutional infrastructure for managing forecasting. They generate information about who is performing well and the incentives to match them, enabling experimentation with new approaches, including building teams with diverse skills.

All this has been kind of obvious for decades. Had we already embraced it, we would have moved on to new problems. Today’s four-day weather forecasts are as accurate as one-day forecasts 30 years ago. Yet improvements have gone missing in economic forecasting. That’s partly because it’s more difficult. (Human beings, unlike air molecules, worry and scheme. They cycle through collective gloom and euphoria.) But we won’t know till we take away the excuses. And even if forecasting tournaments don’t improve forecasting accuracy, they’ll improve forecasting.

First, by properly measuring and identifying outperformers, the focus turns to what works to improve forecasts, not going through the motions and keeping your nose clean with the higher-ups. Second, continually testing forecasts and forecasters’ confidence in those forecasts against unfolding events would expose and punish hubris. Third, a focus on changing confidence in forecasts should also help us detect turning points and provide better forward visibility for rare but highly consequential events like recessions and crashes. They matter more for economic decision-making than whether growth next year will be 1.75 or 2 per cent.

But with rare and unlikely events, how can we trust even superforecasters until they’ve built a track record over numerous cycles? Tetlock and his colleagues are onto it, exploring how forecasters narrow differences between themselves by persuasion and the extent to which superforecasting in one area should give us confidence in others.

I, for one, am relieved that superforecasting teams — no doubt viewing it from many angles — think an AI apocalypse is way less likely than AI pundits do.

Here’s to the unflashy ones

This appreciation of Joe Biden is probably a little too generous, but otherwise mentions all the good things. I’m a fan of the unflashy politicians who surprise on the upside. Most surprise in the opposite direction. In this he reminds me of LBJ, another master of the Senate. At least as the story is told by Robert Caro, he was regarded with contempt by the conceited courtiers of Camelot (though JFK wasn’t too bad to him). LBJ was barely consulted in drafting Kennedy’s Civil Rights Bill, but LBJ eventually got more heavily involved and turned things around before putting it through under his own presidency. The next year President Johnson got through the The Voting Rights Act which was more ambitious still. He took some pleasure in revealing his true nature as a turncoat against the racism many Southerners assumed him to harbour.

At least from our present vantage point, I think Biden’s been the best president in decades, making it even sadder that he’s been so instrumental in reducing America’s capacity to reject an incipient fascist.

For the past few weeks, Joe Biden has cut a deeply unattractive figure. Unable to escape a lifetime of resentments and mired in self-pity, he has stubbornly bucked his party’s elite. …

But the same qualities that have served him so terribly as a candidate were also responsible for his policy successes. Right now, most Democrats can see Biden only as a millstone, but history will remember him as one of the most effective presidents of his era. His fingerprints will be all over the American future.

When Biden came to office, pundits liked to cast him as a placeholder. … Their underestimation stoked his determination to prove himself as one of history’s great men. He privately boasted that his performance would make him worthy of the presidential pantheon that included Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson.

With a one-vote majority in the Senate, he audaciously set out to test the limits of what he could accomplish. The American Rescue Plan, passed in the first months of his presidency, pushed social policy in novel directions. It transferred money directly into bank accounts through the child tax credit, the closest the federal government has come to experimenting with universal basic income. For a brief, glorious moment, the legislation helped cut childhood poverty in half. …

At a moment when Democrats described moderate Republicans as useless toadies, Biden wooed them—and cobbled together bipartisan majorities to pass an infrastructure bill and the CHIPS Act. …

His signature accomplishment was the Inflation Reduction Act. … With its subsidies for clean energy, it will be remembered as the first massive American effort to contain climate change. And perhaps just as significantly, it will be remembered as the moment when the nation reembraced industrial policy. That is, the state began using its resources to guarantee the international dominance of American firms in electric vehicles and alternative energies, the industries of the future.

Biden walked the picket line and lent presidential prestige to the [union] movement. He reversed several generations of indifference to the problem of monopoly and installed regulators who went after Big Tech ferociously.

His supreme self-confidence allowed him to buck the conventional wisdom of foreign-policy mandarins. Both Barack Obama and Trump wanted to end the war in Afghanistan, but only Biden had the courage to actually follow through on that decision—although his chaotic execution of a move that voters overwhelmingly supported eroded confidence in his presidency. A devoted believer in old-fashioned transatlanticism, he plowed money and arms into the defense of Ukraine, as if the future of Europe depended on it. These were bold decisions that a president with lesser experience—and a lesser sense of his own acumen—wouldn’t have had the gumption to make. …

Over the course of Biden’s term, when the press dismissed him as a failure, he kept pushing forward. He never shifted blame onto his aides—and never fired them to cover his own mistakes. He pushed ambitiously, even though he often did so at the risk of his own humiliation.

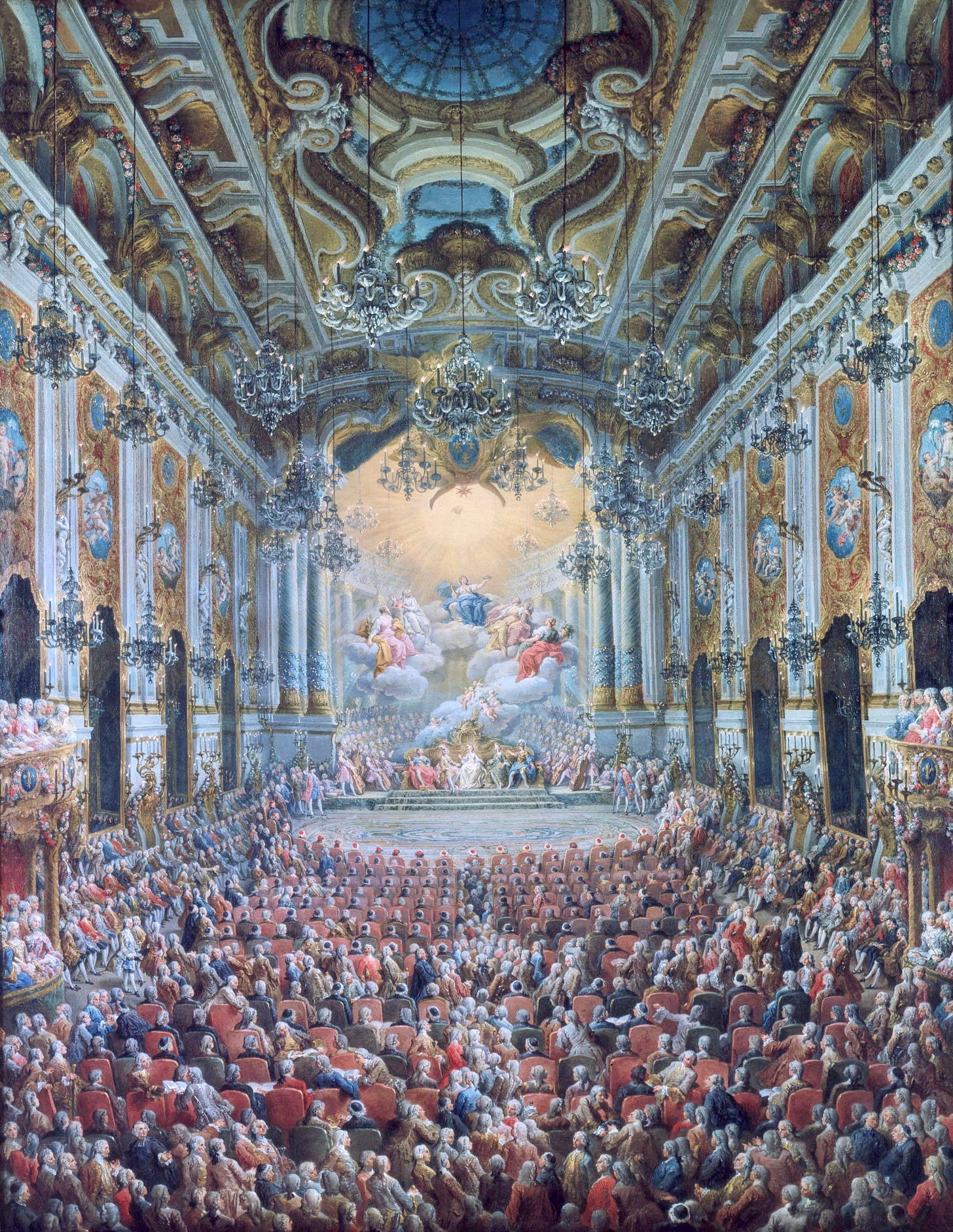

Giovanni Paolo Panini

Who knew? (Not me)

Guaranteed minimum income trials disappoint

The Employment Effects of a Guaranteed Income: Experimental Evidence from Two U.S. States

Eva Vivalt, Elizabeth Rhodes, Alexander W. Bartik, David E. Broockman & Sarah Miller. Paper here.

We study the causal impacts of income on a rich array of employment outcomes, leveraging an experiment in which 1,000 low-income individuals were randomized into receiving $1,000 per month unconditionally for three years, with a control group of 2,000 participants receiving $50/month. We gather detailed survey data, administrative records, and data from a custom mobile phone app. The transfer caused total individual income to fall by about $1,500/year relative to the control group, excluding the transfers. The program resulted in a 2.0 percentage point decrease in labor market participation for participants and a 1.3-1.4 hour per week reduction in labor hours, with participants’ partners reducing their hours worked by a comparable amount. The transfer generated the largest increases in time spent on leisure, as well as smaller increases in time spent in other activities such as transportation and finances. Despite asking detailed questions about amenities, we find no impact on quality of employment, and our confidence intervals can rule out even small improvements. We observe no significant effects on investments in human capital, though younger participants may pursue more formal education. Overall, our results suggest a moderate labor supply effect that does not appear offset by other productive activities.

Randomized Controlled Trial of a Guaranteed Income

Sarah Miller, Elizabeth Rhodes, Alexander W. Bartik, David E. Broockman, Patrick K. Krause & Eva Vivalt Paper here.

This paper provides new evidence on the causal relationship between income and health by studying a randomized experiment in which 1,000 low-income adults in the United States received $1,000 per month for three years, with 2,000 control participants receiving $50 over that same period. The cash transfer resulted in large but short-lived improvements in stress and food security, greater use of hospital and emergency department care, and increased medical spending of about $20 per month in the treatment relative to the control group. Our results also suggest that the use of other office-based care—particularly dental care—may have increased as a result of the transfer. However, we find no effect of the transfer across several measures of physical health as captured by multiple well-validated survey measures and biomarkers derived from blood draws. We can rule out even very small improvements in physical health and the effect that would be implied by the cross-sectional correlation between income and health lies well outside our confidence intervals. We also find that the transfer did not improve mental health after the first year and by year 2 we can again reject very small improvements. We also find precise null effects on self-reported access to health care, physical activity, sleep, and several other measures related to preventive care and health behaviors. Our results imply that more targeted interventions may be more effective at reducing health inequality between high- and low-income individuals, at least for the population and time frame that we study.

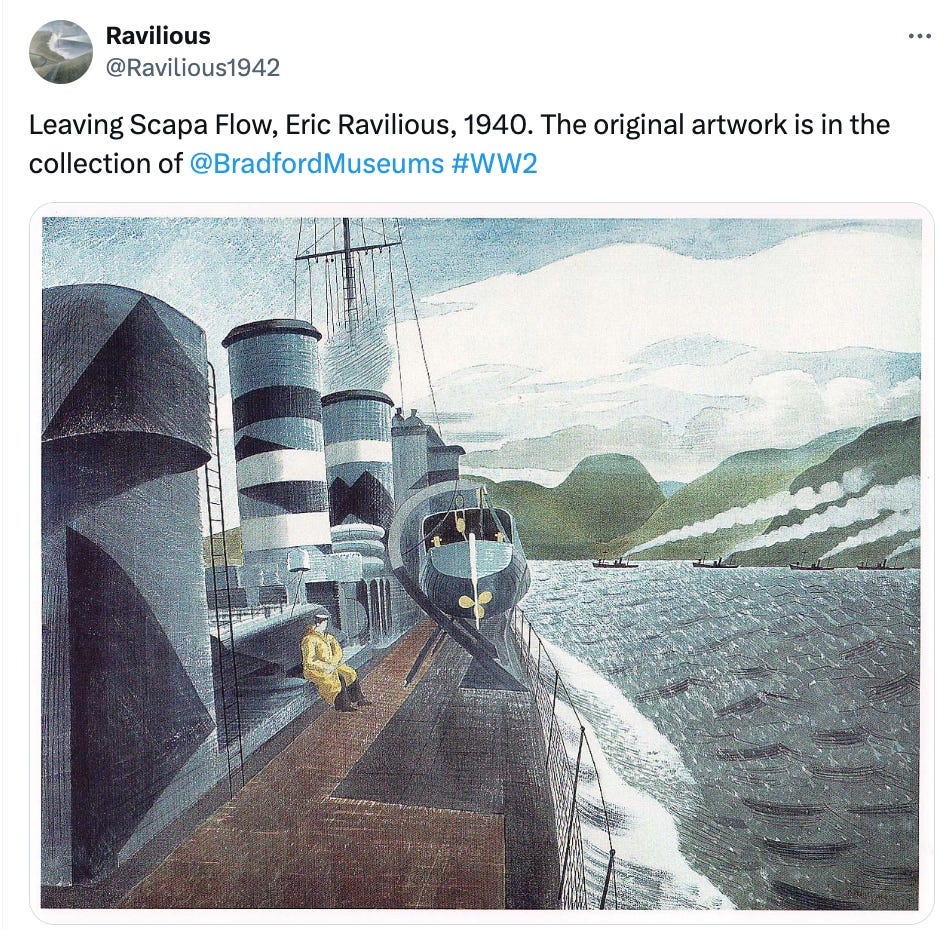

David Tiley: RIP

David Tiley was one of the stars of the early blogging scene at his blog Barista. You can have a look on this link on Archive.org, but it’s difficult to search. When I tried it, I couldn’t find any of the posts of his I remember. However after poking around I realised that back in those glory days, Ken Parish and I had, for several years, edited “Best Blog Posts”. And sure enough in Best Blog Posts 2007, I found the post I was looking for. From the time I got to know him David’s health was fragile and involved occasional dramatic visits to hospital. Here’s the beginning of his entry in Best Blog Posts 2007.

Coming back slowly

I’ve been home from hospital for a few days, and I can focus on fine print. I’ve cut my fingernails so I can type again. Bread tastes funny and I can’t tolerate coffee. I’ve been away a lot longer than we expected.

My first conscious memory after my bowel resection is one of the worst things you can confront in a hospital - an apologetic surgeon. I’d been hit by a medical emergency which was 50 years in the making.

When I was very small I had some kind of unidentified infection, which stopped one kidney from growing. Instead, the bowel had occupied the space, which meant the spleen had moved too. Reorganising my unexpected gut design, the doctors nicked my spleen, which collapsed and had to be removed, while I bled badly.

Two days later, I responded to the trauma with a small heart attack.

The next ten days became a blur of disconnected vignettes, my bed a nest, pushed from scan to scan and ward to ward.

With all that morphine I made friends with a huge bear in the corner. I lost control of my visual cortex and lay for days in a muddle of spontaneous images, some viciously ugly, most collaged from shattered pieces of coloured Perspex cut with frozen, scanned memories. In my own naturally verbal sensorium, I suppose this was the pictorial equivalent of voices in my head. I puzzled for hours over the way that could happen but still be under control, which I guess is the way visual artists function, in a parallel to the stream of words coming from my fingers to this screen.

I twisted back and forth on a mobius strip of recursive identity, trying to work out who I was if the drugs had seized my brain. The “I” that I needed being a creature which could ask questions, organise my bedclothes and work out whether to put my hearing aids in or not.

I remember a man across the ward who was 86-years-old, stone deaf, who shouted very loudly and was mentally flitting through the twilight zone. The doctors seemed to think he might have had a stroke at home; his family simply ignored his ravings, as if they had known his behaviour for a long time.

Next to him was a young man of Islander background who had been in some sort of fight. His mates came and he swanked around, making moves and swaying his hips, laughing about the violence. His big sister was on the mobile talking about someone else who had been arrested over the incident. But that night, when everyone else had gone home, I heard him sobbing in his mother’s arms.

Beyond the curtain at my side was a Czech chippie, who got away from the Russians in the 50s. Eighty-years-old, still smooth skinned and strongly built, he lives with his wife who is five years older on a piece of land somewhere in the hills. His eyes lit up when he talked of his two ponies. Lying there patiently, waiting for his heart to calm, I felt like he was an inspiration, a direction for a life well lived.

I rowed on through the hospital, my bed a dinghy, across rivers of knowledge. Bowels. Spleen. Hearts. I saw slices of my own heart beating, which were slowed down and repeated with their own sound track. “Beat” is not the right word - the thing flutters, endlessly precise, fabulously fragile, each dancing move identical for every second from the womb to the grave.

I am very sorry I didn’t know he was ailing and couldn’t go and see him to say goodbye. But so many people made it to his memorial, I’m not too sure I could have got to the front of the queue in time! RIP David.

Click here for an obituary in ScreenHub which David edited for two decades.

Like Srsly: Wow!

At 4,500,000 views you might want to make it 4,500,001

The vibe shift

Steve Randy Waldman still wallowing in his grief for liberal democracy. Silly Steve and his Trump derangement syndrome.

Last night we endured a ranting lunatic allege that the nearly 80,000 alleged gang members El Salvador's President Bukele has detained without process have been dumped onto America's streets, contributing to a US crime wave that simply does not exist over the relevant time frame. (The crime wave that did exist emerged only during the ranting lunatic's presidency, years before, and has been subsiding ever since.)

In the meantime, we still haven't settled on an alternative to the ranting lunatic that sane people might vote for.

Nevertheless, I'm stuck in a news cycle three-weeks old. Remember that one? The one that marked the end of liberal democracy in the United States by providing a road map for how a US President can wield the vast powers of the American state without He or His suboordinates facing any practical risk of accountability to the law?

I mean, I know there has been a vibe shift. But I'm having a hard time letting go of the whole liberal democracy thing. I guess it's pretty cringe.

A standing citizen assembly in Western Sydney

Tim Dunlop on giving a talk at a function celebrating the establishment of a standing citizen assembly in Western Sydney.

The entire evening was a testament to … the fact that a community brought together under the right circumstances and with a shared commitment to making that community better is, almost by definition, steeped in love and kindness.

Back in August last year, WentWest, the nonprofit Primary Health Network in the area, provided financing and support for two two-day citizens assemblies (CAs) on the subject of health outcomes. …

The assembles that were held last year—one consisting entirely of First Nations’ participants and developed in conjunction with the local Indigenous population—were so successful that WentWest decided to provide funding for a permanent Assembly. So, what is now known as the Western Sydney Citizens’ Assembly will be an ongoing structure and a range of other local people will be invited to participate in appraisals of the way healthcare is delivered in their area. The idea is to influence government policy and provide data so that governments are better able to address these issues.

I think the permanence of this Citizens’ Assembly makes it unique in Australia, but god, I hope other communities take inspiration from what they have done and that it isn’t unique for too much longer. …

The thing that stands out is the transformative effect they have on those involved.

[E]veryone I spoke to was brimming with enthusiasm for what they had been part of. For many of them, this sort of public participation was a new and daunting experience, but by the end of the process, they were fully engaged citizens keen to do more. They had not only gained knowledge of how healthcare works and the scale of some of the problems the system faced—by reading the provided literature and listening to various experts speak—they had educated those experts in turn, sharing their experiences and concerns about engaging with healthcare in the area. …

Even getting up and speaking at an event like this was a challenge for many of them and one young woman, the mother of a beautiful four-month old daughter, told me after she spoke that standing at the lectern was harder than giving birth! But they all spoke so beautifully, straight from the heart, displaying not just the practical knowledge they had gained through the Assemblies but the sense of democratic empowerment that had been instilled in them by this simple process.

I don’t think there was a dry eye in the house.

Unfortunately, though perhaps not surprisingly, none of the politicians who had been invited to the event bothered to show up, and I can’t tell you how angry this makes me. …

Letter to a teacher

Wonderful article from Dean Ashendon

A time capsule when so much more was in play, so much more seemed possible. But not many people understood how hard what they were proposing seems to have been. The article suggests some fairly straight line between the sensibilities and sympathies of the individual students involved and the political action that might address their plight. Alas history since 1967 suggests it ain’t no straight line.

“Dear Miss,” begins Letter to a Teacher. “You won’t remember me or my name. [But] I have often had thoughts about you and about that institution which you call ‘school’ and about the boys that you fail.

“You fail us right out into the fields and factories and there you forget us.”

The Letter was addressed to every teacher, every school, the system. The “us” (and the “I”) were eight boys in their early teens, sons of Italian peasant families from Barbiana, a hamlet in the backblocks north of Florence. They wrote, nearly sixty years ago, for all of Italy’s poor.

Schools, they said bitterly, are like hospitals that tend to the healthy and reject the sick. Schools are reserved for those who can get their culture at home.

Schools make boys like us hate study, so the best years for learning are spent “fooling around with sex or fooling around with sport.”

Schools don’t let the poor understand because they’re not allowed to talk about poverty. It’s not nice to talk about such things.

Schools turn maths, history, languages, science, “fine things,” into pathetic exercises, learning for marks, learning for the profit of individuals.

The boys, the authors of Letter to a Teacher, had been required to go to school until they were fourteen. They’d done their five years at elementary school but then there was nowhere for them to go — there was no media inferiore in or near Barbiana. The gap was filled by the local priest, Don Lorenzo Milani.

Barbiana was a huddle of little houses with just one glimpse of riches, a beautiful fourteenth-century church. Don Milani was there because he was a troublemaker. Head office (aka the bishop) had no time for troublemakers, especially not then, in Italy, in the mid 1950s. …

Coming to the priesthood from the high bourgeoisie after a road-to-Damascus experience, Milani was among the new wave of insurgent priests, deeply committed to the Church but not to its orthodoxies. … On schooling, Milani was at one with many of a broadly left persuasion — including communists such Loris Malaguzzi, founding genius of early childhood education in Emilio Reggio — in believing that children and childhood were to be respected, listened to, and encouraged toward understanding and action in their own lives. The reading list at Barbiana included The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. …

Milani did not like to give religious instruction; his schoolroom bore no religious iconography so that even communist and atheist parents would see that this was not “the priest’s school.” His mission wasn’t to proselytise, or not directly anyway. It was to give the poor what was theirs by right, the right to know and to understand. …

Increasingly Milani and the boys ran a “hospital” that made a point of welcoming the “sick” — the failed, the ejected, the bitter who came to Barbiana as its fame grew. “They had never heard that one goes to school to learn, that to go is a privilege,” the boys report. “The teacher, for them, was on the other side of a barricade and was there to be cheated. It took them one hell of a time to believe that there was no marks book.” …

Letter to a Teacher came from a year’s relentless labour. … Letter to a Teacher was an instant sensation, first in Italy — its statistical achievements won a prize usually reserved for promising physics students, and it was even credited with triggering the student uprising of 1968 — and then, as it was translated into one language after another (around forty eventually) a source of astonishment and inspiration to hundreds of thousands around the world, including me.

In the longer run, though, the boys were right to worry. They had worked and written in that brief moment when the world was young and all seemed possible. …[And click through to Dean’s article for Letter’s lessons for today.]

Please do read Letter to a Teacher. Those 100-odd pages from another time and another place remind us of how far we’ve come and how far we haven’t, of what kids can do if they’re given half a chance, and of the kind of schooling that every kid should have.

Heaviosity half hour

From the fine philosopher who writes Footnotes2Plato.

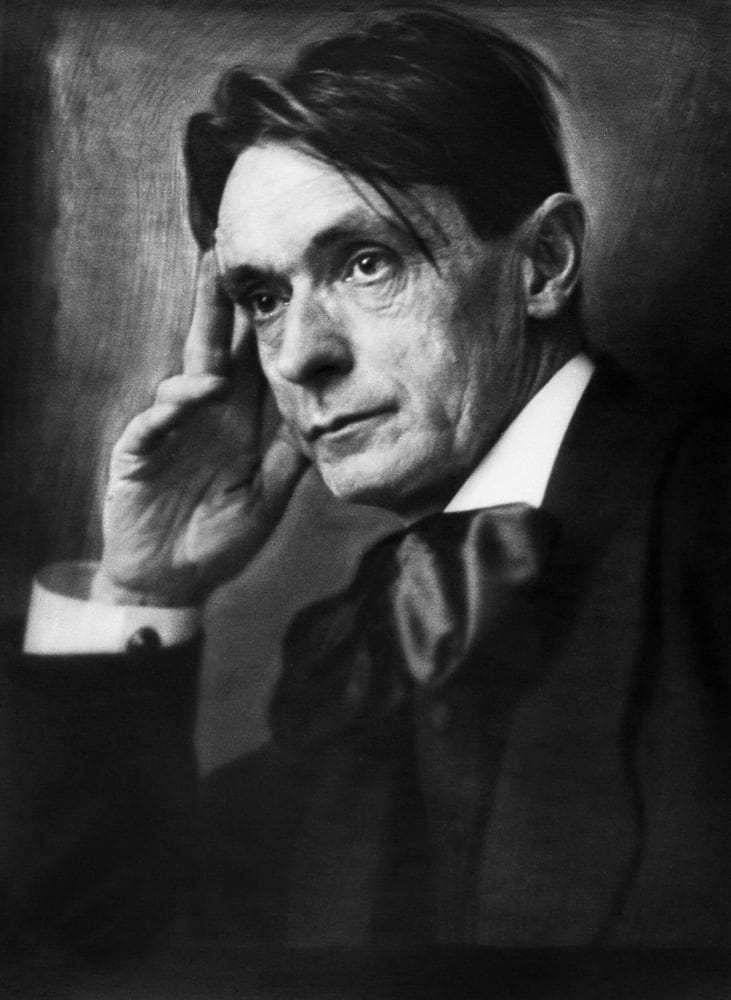

"Toward a Goethean Physics" (Part 1 of 3) Below are some excerpts and more or less stream of consciousness reflections upon reading the student notes from Rudolf Steiner’s so-called “Light Course” (GA 320; Dec 1919-Jan 1920). The number headings correspond to each of his lectures. In Part 2 I’ll share reflections on lectures 4-6, and in Part 3, lectures 7-10. These notes are helping me prepare for a presentation next month at MysTech’s “Mysteries of Light” conference.

1.

Rudolf Steiner spent much of the 1880s editing and philosophically explicating Goethe’s natural scientific works, including his theories of color, plant metamorphosis, and animal morphology. At the time he felt fruitful application of the Goethean method to physical science was an impossibility. A new approach would only be possible if physics realized of its own accord that the then current materialistic direction of its research into such phenomena as light, warmth, and electricity, was a dead end. A new start would be necessary on fundamentally different footing. Three decades later (1919/20), when Steiner delivered the Light Course in Stuttgart, the situation had changed. Physics had found itself “caught up in transformation,” so much so that “there is much we could interpret as the dawn of a new worldview” (LC, p. 16).

The theoretical discoveries of electromagnetic, radioactive, quantum, and relativistic phenomena had destroyed the old mechanistic categories. As Whitehead put it in 1925: “The old foundations of scientific thought are becoming unintelligible. Time, space, matter, material, ether, electricity, mechanism, organism, configuration, structure, pattern, function, all require reinterpretation. What is the sense of talking about a mechanical explanation when you do not know what you mean by mechanics?” (SMW, p. 16). Science was in search of a new world-picture, and Steiner’s hope was that the Stuttgart Waldorf teachers he was offering some improved suggestions to would be able to sow Goethean seeds into the next generation of scientists and engineers. We should not forget that the real aim of Steiner’s lecture cycle was to help create an educational environment wherein children would be encouraged to remain in a participatory relationship with their embodied, sensory experience of warmth, light, and sound, even as (when age appropriate) more abstract mathematical and classificatory concepts are introduced.

Mechanistic physicists have tended to look for hidden causes behind phenomena. Steiner gives the example of the ether, which in the 19th century was widely believed to be behind the phenomena of light and electricity. Wave movement or vibration in the ether was thought to be the objective cause behind the visible phenomena of color. Goethe does not conjecture hidden causes, as if the unknown might explain the known. Instead, he patiently stays with the sequence of phenomena, finding their true relations and thereby distilling the archetypal phenomenon linking them together. This is akin to a move Whitehead makes as part of his reformulation of Einstein’s tensor equations and natural philosophy in Principle of Relativity (1922). Whitehead rejects “the shy ether behind the veil” hypothesized by 19th century physicists. Instead, in line with his earlier criticisms of the “bifurcation of nature” and affirmation that “everything perceived is in nature” (Concept of Nature, 1920), he asserts that “the ether is exactly the apparent world” (Principle of Relativity, p. 37). A few years later, in his first lecture as a professor of philosophy at Harvard University, Whitehead further explained his approach to scientific knowledge in a way that is strikingly convergent with Goethe’s natural scientific method and clearly open to Steiner’s spiritual scientific extension: “According to the view which I am putting before you there is nothing behind the veil of the procession of becomingness, though there is much pictured on that veil and essential to it which our dim consciousness does not readily decipher.

Indeed the metaphor of a veil of appearance is wholly wrong. Reality is nothing else than the process of becomingness, of which we are dimly conscious. Every detail of the process is open for consciousness, though in fact our individual consciousness is only aware of a very small fragment of what is there for knowledge.” (“First Lecture,” 1924, p.17) Whitehead’s process of becomingness is akin to Goethe’s metamorphosis of phenomena. Both thinkers reject the search for hidden forces, as if our experience of color was an epiphenomenal effect of the trembling of an all-pervading but stubbornly invisible ether substance. If there are fields and forces in nature (and there do appear to be!), let us stick with those we can directly feel and refrain from unnecessarily introducing impercepta. It may of course prove helpful to invent hypotheses concerning as yet unperceivedphenomena. There is much pictured in nature’s metamorphosis that we are not yet but could become conscious of. Hypotheses allow us to go in search of new, subtler phenomena. The confusion begins when a hypothesis conjectures not just the unperceived but the unperceivable. When this occurs, purely conceptual phantoms are dressed up to look like they could be actually existing phenomena. The real phenomena are ignored or distorted so as to fit the expectations of the conceptual model. We become wed to the model and increasingly divorced from the life-world it is supposed to help us understand. Physics must remain within the bounds of feeling alone if it “is not to degenerate into a medley of ad hoc hypotheses” (Whitehead, SMW, p. 17).

After all, as Schelling could already remind us back in 1797 (Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, p. 18): “you can in no way make intelligible what a force might be independent of you. For force as such makes itself known only to your feeling.” It is worth sharing a few additional lines from Schelling’s Ideas (p. 10-11): “[we] are not born to waste [our] mental power in conflict against the fantasy of an imaginary world, but to exert all our powers upon a world which has influence upon us, lets us feel its forces, and upon which we can react. Between us and the world, therefore, no rift must be established.” Instead of attempting to explain the known by something unknown, a participatory, organic science stays with the unfolding phenomena. Thinking activity that can attend to the rhythmic flow of pure experience need never encounter a rift between subject and object. The attempt to explain the perception of a crimson sunset in terms of either electromagnetic waves in space or electrochemical waves in the brain is a textbook case of Whitehead’s “fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” Our experience of red is not simply in our head or in nature. Red has no discernable material cause. Colors are better understood as species of ecological relationship between light, darkness, and sight.

These three elements cannot themselves be explained by reference to anything else, since they are what is given to us in perception. Natural science is simply the study of the patterns disclosed in perception, ie, the search for systematic relations among percepta. Rightly arranged, the facts themselves flower into theory. The archetypal phenomena blossom not behind or beneath what we see but between seer and seen. We can study sight itself, turning out scientific attention onto our own consciousness as percipients of nature. But this means leaving the limits of natural science behind to begin a complementary but fundamentally new kind of inquiry. Steiner called it spiritual science. Spiritual science does not go beyond phenomena but recognizes the role of our own conscious imaginative, inspired, and intuitive thinking activity in disclosing novel phenomena. But that is a subject explored elsewhere. Steiner lists the three typical starting points of natural scientific research: Classification (into species and genera), Causation (in terms of forces or fields), Generalization (into mathematical laws of nature). He contrasts these with the Goethean scientific method. Goethe rejected rigid classification of finished forms, seeking instead to trace the gradual transformation or metamorphosis of one phenomenon into another.