Trump: the upside

Yes, folks, there is an upside. AOC has removed her pronouns so that’s a win.

And some of the appointments might be improvements on the usual careerists — particularly in health. (Though there are also fruitcakes like RFK Jr.) Anyway, read on for some straws in the wind. The US is unique among the countries I know of in the period of time a new administration gets between winning an election and taking power. It’s a particularly silly season which rewards the pundit. I’m thinking some pretty seriously bad things will happen. But we can all live in hope for the next month and a bit. Oh and the crowds that turn up will be … well … YUGE! The biggest ever seen. Anywhere.

Saving the world in your spare time (OK, you got paid for it.)

AIs argue it out: seriously!

In February 2023, Google’s artificial intelligence chatbot Bard claimed that the James Webb Space Telescope had captured the first image of a planet outside our solar system. It hadn’t. When researchers from Purdue University asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT more than 500 programming questions, more than half of the responses were inaccurate(opens a new tab).

These mistakes were easy to spot, but experts worry that as models grow larger and answer more complex questions, their expertise will eventually surpass that of most human users. If such “superhuman” systems come to be, how will we be able to trust what they say? “It’s about the problems you’re trying to solve being beyond your practical capacity,” said Julian Michael(opens a new tab), a computer scientist at the Center for Data Science at New York University. “How do you supervise a system to successfully perform a task that you can’t?”

One possibility is as simple as it is outlandish: Let two large models debate the answer to a given question, with a simpler model (or a human) left to recognize the more accurate answer. In theory, the process allows the two agents to poke holes in each other’s arguments until the judge has enough information to discern the truth. The approach was first proposed six years ago, but two sets of findings released earlier this year — one in February(opens a new tab) from the AI startup Anthropic and the second in July(opens a new tab) from Google DeepMind — offer the first empirical evidence that debate between two LLMs helps a judge (human or machine) recognize the truth.

“These works have been very important in what they’ve set out and contributed,” Michael said. They also offer new avenues to explore. To take one example, Michael and his group reported in September(opens a new tab) that training AI debaters to win — and not just to converse, as in the past two studies — further increased the ability of non-expert judges to recognize the truth.

Your Turing Test

Scott Alexander has a test you can do to figure out whether you can tell AI art from human produced art. I am not interested in doing the test, but will replicate images I like throughout this newsletter. If you want to do the test you can do it here.

Getting officials who are interested in the truth

Educated elites bemoaning the return to power of Donald Trump would do well to ask how they contributed to this outcome. Trust in institutions is down, perhaps especially for those institutions charged with helping the public discern the truth. Observers often blame the “information ecosystem”—in particular, the internet—but elites have also undermined public faith by allowing science and the wider pursuit of truth to be politicized. The incoming administration presents the opportunity for a reset.

To that end, Trump should nominate Stanford University’s Dr. Jay Bhattacharya to lead the National Institutes of Health. Bhattacharya exemplifies qualities that were lacking in our nation’s scientific leadership during the pandemic. The ostracism and condemnation he faced for his dissenting views provides a vivid illustration of elite failures to live up to their own deepest values.

In the early months of the pandemic, deep uncertainty prevailed. We knew people were dying in frightening numbers in China’s Hubei Province, the north of Italy, and then in New York City. Early projections of mortality rates from the World Health Organization and mathematical modelers in Britain were alarming. The World Health Organization announced that the case fatality rate—the percentage of deaths among known cases—was 3.4 percent. But we also knew that early projections of morbidity in pandemics tend to be far too high, because early at that stage, the “cases” we see are people showing up sick at hospitals and clinics. That was the situation in February and March 2020. We didn’t know how many people had contracted the novel coronavirus with mild illness or without getting sick. …

Very early in the pandemic, Bhattacharya set out to gather vital information and to question what had too soon become settled assumptions. First, he joined with colleagues to ascertain what is known as “seroprevalence,” meaning to find out how many people in the population had been exposed to the novel coronavirus. … Bhattacharya, his collaborators, and others working on this problem quickly found that the infection fatality rate … was much lower than the early dire projections, and that risk of death was concentrated among the elderly.

In addition, Bhattacharya and other colleagues drew attention to the tremendous collateral damage of trying to stop the spread of the virus by locking down societies. He argued that most such measures were unnecessary, as most of the population was at low risk of serious illness. In October 2020, he co-authored a very brief document, the Great Barrington Declaration. He has called it the least original thing he has ever written, given how closely it hewed to pre-Covid public-health precepts. …

The Great Barrington Declaration should have been treated as a serious attempt by distinguished scholars to interrogate assumptions and debate the costs and benefits of a highly questionable policy consensus resting on shaky evidence. Instead, leading public-health officials—led by the then-director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins—dismissed Bhattacharya and his co-authors as “fringe epidemiologists.”

The attempt to suppress discussion of the trade-offs entailed by pandemic-containment measures was another indication of the orthodoxy that had set in by the fall of 2020. Why didn’t the NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launch seroprevalence studies in March of that year, as Bhattacharya and his colleagues had? Why didn’t the NIH commission quality studies to find out more about whether masks work to slow viral transmission in the population, or whether school closures were really reducing deaths and serious illness from the virus? …

Rather than acknowledge how little they knew, public-health leaders too often doubled down and insisted that they already had the answers. The mantra was “follow the science”: a slogan that often seemed to defy the basic scientific—and liberal—imperative to respect criticism, tolerate dissenters, and be open to revising one’s views. The result was an insistence on poorly justified policies and a series of bewildering flip-flops in public-health messaging on matters like masking, airborne transmission, the lab-leak hypothesis, and whether vaccines prevent infection. A decline of trust in health agencies was an inevitable consequence.

Not for profit media

The Australian superannuation system shows how not-for-profit structures work better for retail wealth management than for profit funds — who disgorge large amounts of money on marketing. Now it seems not for profit structures work for better for media. And for similar reasons perhaps — each is less tempted to pick up every penny that can be had by underestimating your customers. WaPo columnist makes a meal of a simple thing — ProPublica is a successful not-for-profit media company.

The plight of the news business has gotten steadily worse over the past decade. Cable TV networks are shedding audience share at an alarming rate. Increasingly, they seemed to have forgotten who their audience even is. The hosts of “Morning Joe” visiting Mar-a-Lago was the sort of move, judging from the backlash, that is likely to increase its progressive audience’s flight from MSNBC. CNN, in its effort to be all things to all people, is also hemorrhaging viewers. Many national newspapers are losing subscribers (and hollowing out their coverage), and local media has been shriveling for years. (The Post’s decision not to endorse a presidential candidate unleashed an exodus of hundreds of thousands of readers who had expected a clarion voice in defense of democracy.)

It is not merely this shrinkage in conventional news consumption that should be alarming. The preponderance of voters who get no news whatsoever suggests the very notion of an “informed electorate” might become a thing of the past.

Sign up for the Prompt 2024 newsletter for answers to the election’s biggest questions

However, there is a part of the news ecosystem that seems to be growing by leaps and bounds: nonprofit news, especially the juggernaut ProPublica, which has been responsible for buckets of scoops that for-profit media have missed.

I recently spoke with Stephen Engelberg, ProPublica’s editor. He described the extraordinary expansion of an experiment that began in 2008 with a $10 million budget. Since then, its national coverage and staff (now about 150) have boomed, its budget has increased to $50 million, and it has created hubs across the country to fill the gap in regional and state news. It went from 36,000 donors in 2022 to 55,000 today.

Starting with a single hub in Illinois, it has added others in the South, Southwest, Northwest, Midwest, Texas (in collaboration with the Texas Tribune) and New York. It has received seven Pulitzer Prizes, five Peabody Awards, eight Emmy Awards and 15 George Polk Awards in the short time it has operated.

Moreover, ProPublica has pioneered an inventive partnership with local papers all over the country. ProPublica provides an enterprising investigative reporter with salary for a year plus the infrastructure necessary to report the story, including editors, research assistance and lawyers.

“This was a massive shift in what we are doing,” Engelberg says. He is producing a body of work that provides, as he put it, “substantial knowledge all over the country.”

The impact is unmistakable. This year, ProPublica has averaged 11.8 million page views per month on- and off-platform (views on propublica.org and on aggregators such as Apple News and MSN). That represented a jump of 22 percent since 2022. It also just passed 200,000 followers on Instagram and has nearly 130,000 followers on YouTube.

It has partially filled the demand for local reporting that has resulted from the brutal realities of the newspaper industry’s consolidation. But it has also found relevance by being serious and focused, instead of giving way to many legacy media outlets’ impulse to lure back readers with games and frivolous lifestyle columns.

“I would say they are missing the point,” Engelberg says. “You get subscriptions by consistently providing material you can’t get elsewhere.”

In reading the output of ProPublica and its affiliates, I am struck by the density and depth of the reporting. You learn new things, not simply what people are saying about things you already know. Rather than following the same three or four D.C.-centric stories with endless iterations (What does Sen. Tom say about the White House announcement that it would oppose Rep. Jane’s tweet?), ProPublica does not assume its audience wants to hear only about those stories or is allergic to diverse topics.

There are still gaps nationwide. There are places all over the country where granular coverage of local politics is nonexistent. Every day, school board meetings, city councils and other public hearings go unreported. It has become difficult to persuade people to pay for that sort of local coverage.

But perhaps, rather than giving news consumers the equivalent of junk food, meaty coverage about critical events could draw disaffected readers and viewers back. I can only hope, for the sake of our democracy, that ProPublica will spawn imitators and provide competition to spur for-profits to be a better version of themselves.

Marty Makary: fruitcake or truth-teller?

Vinay Prasad is a substacker I was sent to by someone with a medical background whom I have a lot of respect for. Is it right? Who knows? I presume it’s got a lot going for it and that Marty is more a truth-teller than a fruitcake. Certainly most of the medical officers dishing out putatively independent advice in our country left a lot to be desired. Like Brendan “Masks are silly, oh no wait, they’re compulsory” Murphy and his band of merry men.

Marty Makary, distinguished Hopkins professor, surgeon, best-selling author, and original thinker nominated to be FDA commissioner.

Marty Makary, a Johns Hopkins Surgeon, and professor, has been nominated to serve as FDA commissioner. 20 years ago, Marty was first author on the surgery checklist paper, which was later made into a bestselling book by Atul Gawande,

Marty has a long history of pushing back on captured and corporate interests in medicine. His books, Unaccountable and the Price we Pay, are both aimed at making health care better and more affordable for consumers.

During the COVID19 pandemic, Marty gained prominence for questioning government dogma that many were scared to tackle. When the government wrongly pushed masking toddlers and vaccine mandates, Marty stood up to say that those were inappropriate. He defended nurses who got COVID on the wards, and then were fired for not getting a vaccine they did not need, which did not benefit their patients.

Marty’s positions took real courage at a time when his colleagues kept a low profile, fearful of that their tenured jobs would be threatened. Marty is also known for hundreds of academic articles, in addition to a 2024 book Blind Spots, which is a top book according to Amazon’s nonfiction 2024 list.

Colleagues of Marty have this to say about him:

“I have not always agreed with Marty,” says Vinay Prasad, professor and physician at UCSF, “years ago he wrote a paper on medical error and I wrote a rebuttal.”

“But when he met me, he raised the topic, and wanted to learn more about how he might improve the work. He asked me what I thought about the broader thesis of medical error, and we reached a lot of common ground.”

“Marty is not like 99% of academics. He thinks for himself. Naturally, two people will never agree on everything, and no one is infallable, but Marty got the most important things right on covid:

Natural immunity provides strong protection against severe disease from reinfections

Schools should be open

Kids should not wear cloth masks

Community mask mandates have no data

Vaccines should target the elderly, nonimmune and not young, or those who had covid

Myocarditis is an important safety signal

VITT is game over for J&J

After vaccination, we have to go back to normal

CDC should run RCTs of NPIs

Peter Marks at FDA inappropriately pushed out Gruber and Krause

Scientists should have more humility

There is a fundamental conflict between Fauci giving out grants and setting policy- no one will criticize him

Covid began in an NIH funded lab in Wuhan, and we must stop GOF research”

On these issues Marty, and not his peers, was right.”

That’s how I would write the article. In short, Marty is the first nominee for FDA commissioner I have seen in my entire life who has ever said anything that went against corporate interests. He had courage to stand up for the weak and powerless during COVID. He is not a pharma-shill. He has true integrity. He is a good communicator.

He did not get everything right during COVID; no one did, but his batting average is pretty damn good. More importantly, his decisions are guided by his reading of evidence, and he is open to refine his thinking. That makes him something rare in medicine: a scientist.

Were all slave societies brutal?

Well I have little doubt the answer is yes. But some were a lot more brutal than others. And that depended on what was being done and the technologies in use, and, as Adam Smith knew, on the degree of skill the slaves were expected to show. More skill => less brutality. As Adam pointed out, if a slave figured out a smarter way of doing something, not only did he not gain from adopting it, he might get a belting for being lazy. So slavery looked like the cheapest form of labour, but was really the most expensive.

The portrayal of slaveowners as inherently sadistic figures is common. … Yet historical evidence suggests that the brutality of slavery was shaped by production systems and crop requirements, rather than solely by individual malice. …

Athenian slaves were used in a wide range of tasks, from agriculture and household labor to skilled trades. Skilled slaves, especially those involved in specialized crafts, were seen as valuable assets and were sometimes even allowed to earn wages or buy their freedom. Moreover, they were treated with comparative moderation, as Athenian slaveowners sought to protect their lucrative investments.

By contrast, the Spartan system relied on the total subjugation of helots – agrarian slaves who were essential to sustaining Sparta’s martial society. … Due to their large numbers and the Spartans’ constant fear of rebellion, they were treated with immense brutality, including periodic state-sponsored purges aimed at limiting their population. …

Robert C. Allen’s study of slavery in East Africa during the 19th century provides insight into how specific crop types influenced the harshness of slave treatment. In regions where labor-intensive cash crops like cloves were produced, slaveholders subjected slaves to grueling conditions in order to maximize their productivity. … Conversely, regions focused on the cultivation of less labor-intensive crops, such as dates or grains, required a more stable workforce, resulting in comparatively milder treatment. …

In the Caribbean, sugar plantations stand out as an example of particularly harsh slave conditions. Why? Michael Craton has argued that brutality in sugar economies resulted from the high demand for labor and the immense profitability of sugar. Plantation owners viewed slaves as replaceable parts of the production process, leading to a brutal cycle of overwork and high mortality rates. Rather than investing in the long-term productivity of their slaves, sugar plantation owners found it economically advantageous to work them to exhaustion and then replace them with new laborers from the Atlantic slave trade. …

In Bermuda, maritime slaves performed skilled work essential for the operation of ships and, therefore, of the island’s broader economy. As a result, these slaves were often afforded relative autonomy. They enjoyed a level of trust that was largely unknown on Caribbean plantations. As in the case of ancient Athens, the skill demands of maritime labor moderated the degree of brutality to which slaves were subjected.

These skill demands also had a lasting legacy. The premium Bermuda’s slaveowners placed on skilled labor meant that slaves acquired various technical competencies, which they were able to use to their economic advantage after emancipation. The demand for skilled labor helped foster a culture of productivity and adaptability, which laid the foundations for the island’s relative success in modern times. …

What’s more, these enduring impacts are evident in contemporary studies of cognitive and economic outcomes across former slave societies. Bermuda and Barbados, both of which developed distinct socio-economic structures favoring skilled labor and early education under slavery, exhibit higher average IQ scores than countries like Jamaica, where the slave economy prioritized labor-intensive crops over education or skill development. The correlation between historical labor demands and present-day cognitive outcomes underlines how the socio-economic foundations of slave societies continue to shape those societies in subtle but significant ways. …

I enjoyed reading this but didn’t read all the way through

Wellbeing: some more malarky

A good FT column on the British Statistical Office reaching for the holy grail of a measure of wellbeing — and (as you’d understand if you put any serious thought into it) failing miserably. HT: a subscriber and friend.

As Europe was miserably shivering with thermostats turned down and energy costs surging during the winter of 2022-23, the good news was that we in Britain were boosting net inclusive income per head. Everyone in the country moaning about broken public services is mistaken — their quality has been improving. And for almost two decades, the “inclusive” measure of capital (the nation’s wealth including human, natural and fixed capital) has not changed more than 2.1 per cent from its 2005 level in the face of global financial crises, pandemics and periods of austerity.

If you think these statistics are irrational, irrelevant or even nonsense, do not take it out on me or the UK’s Office for National Statistics, which produced these official figures earlier this month. The guilty party is those that hold the very popular view that we must ditch headline measures such as GDP and aim to rectify all the long known faults with this statistic.

Ever since Robert F Kennedy senior castigated GDP in 1968, saying “it measures everything . . . except that which makes life worthwhile”, statisticians have wanted to create holistic measures of wellbeing that included not only material market outcomes, but the quality of public services, unpaid household chores, the pollution of the planet’s air and waterways, cultural ecosystems, intellectual property and the degradation of our atmosphere by greenhouse gases. This, proponents have argued, would force politicians to have the right priorities and create a better society.

Well, in the UK, the results are in and they are, frankly, a bit of a mess. The ONS has attempted to measure all of these things, attach financial values to them and create measures of gross inclusive income, net inclusive income, and inclusive capital.

The statistics agency describes how some measures have gone up, some gone down and some (inclusive capital) stayed the same in a release with seemingly random numbers akin to the fictitious TV maths quiz Numberwang. Dig into the details and you find nuggets such as the supposed rise in the quality of public services on an annual basis from 2005 to 2020.

I have no criticism of the ONS or their attempt to undertake this work. It is painstaking and difficult and will inevitably involve seemingly arbitrary decisions about many non-market goods and their weights in the overall inclusive wealth and income accounts. There is already quite a bit of imputed and seemingly difficult to understand data in the existing measures of national income and wealth.

The problem lies with those thinking that the world would be different, and that their priorities would become national priorities, if we ditched GDP and measured something else instead.

By far the most important priority for national statistical agencies is to produce figures that are broadly accurate, tangible and understandable. That means GDP and other measures of paid activity in the economy are extremely valuable as a gauge of how money flows and the resources available for households and government to consume and to invest. It means making sure your statistical quality does not degrade to the extent that everyone treats official UK labour market data as a bit of a joke. It also means putting in effort to measure and understand pollution, cultural capital, perceptions of public services, human loneliness, unpaid household work and all the other things that matter to us.

A much lower priority, however, is to seek to add them all up by imputing values and creating a single index of everything. Doing that creates an index of nothing or statistics that are so difficult to understand that they have little value. Ultimately, it is not the job of national statistical agencies to weight the values of good and bad in society. That is the role of democracy.

Reserve currencies and stablecoins

Uncle Sam can rest easy for now. A Russian plan to break the grip of the U.S. dollar through a new international payments network met a cool reception at the BRICS summit in Kazan … with the emerging market club’s official declaration failing to mention the “BRICS Bridge” initiative by name. Rather than slipping, in fact, the greenback’s supremacy may be strengthening because of an entirely different monetary innovation: dollar-backed stablecoins.

Russia’s BRICS Bridge would enable the settlement of trade and finance between Brazil, China, India and other members of the group, using their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). A mooted second stage would introduce a new international currency backed in part by gold. That could threaten not just the reach, but also the value, of the U.S. dollar. The yellow metal would rally, and the greenback wilt, if use of the new monetary unit were to take off. …

Instead, the most important monetary announcement of the week took place in California. On Monday, San Francisco-based U.S. payments firm Stripe announced the acquisition of a little-known crypto startup for US$ 1.1 billion. Its target – called, coincidentally, Bridge – is a specialist in stablecoins: private, digital currencies pegged to a fiat currency such as the dollar. This Stripe-Bridge stablecoin tie-up is more likely to define the future world monetary order than the BRICS Bridge CBDC one. It is also likely to strengthen, not weaken, the role of the greenback – and perhaps its value too.

Underlying both initiatives are three trends of the last fifteen years. The first is the spread of mobile telephony. That democratised digital payments and made them possible on the move. The second is the steep decline in the cost of computing power and internet bandwidth. That opened up digital settlement in the cloud. The third was innovation in cryptography. That enabled the development of secure, decentralised digital ledgers such as blockchains, and the cryptocurrencies that can operate on them.

Private, digital currencies like bitcoin were the first to emerge from this revolutionary mix. Two advantages over bank-based currencies make them in principle a killer app. The first is the intrinsically international nature of the internet, which makes web-based cryptocurrencies global in scope. There is no need for cumbersome national intermediaries: money can flow freely around the world. To the communications miracle of VOIP, voice over internet protocol, can be added the financial miracle of MOIP, or money over internet protocol. The second advantage lies in functionality. Traditional currencies, even in virtual form, can only settle payments. Cryptocurrencies are programmable: they can automate other financial services too. A technology which economises on bankers and lawyers is always a popular idea.

Unfortunately, the first generation of private, digital currencies were hobbled by a key design flaw. Following bitcoin’s lead, most adopted their own standard units, untethered from existing currencies. That rendered their market value nebulous, which in turn led to epic speculative booms and busts. It also implied competition with existing national currencies, and so provoked a ferocious regulatory backlash. The result is that as of today, transactions in own-standard cryptocurrencies have tumbled from their 2021 peak.

The digital revolution, however, is now beginning to birth public, digital currencies like CBDCs too. CBDCs share the plus of programmability with their private, digital counterparts. But as virtual representations of existing fiat currencies, they swerve the speculative volatility and regulatory exposure that caused own-standard cryptocurrencies to come unstuck.

Yet while CBDCs are an advance on private cryptocurrencies in these respects, in others they take a step back. By definition, they are designed to settle payments under a particular central bank, not as part of an seamless global network. That’s why add-ons like BRICS Bridge are necessary to allow them to facilitate cross-border trade and finance. Then there is the awkward detail that they pose an existential threat to traditional banking systems. If money-users can transact directly using risk-free central bank money, why would they continue to hold deposits at risky commercial banks? To ask the question is to answer it – and to keep bank treasurers up at night.Stablecoins, the latest innovation in digital currency, are a hybrid of the private and public models and claim to deliver the best of both their worlds. Like private cryptocurrencies, they offer a real-time, global payments platform – without the need for any BRICS Bridge. Like CBDCs, they offer digital tokens collateralised by traditional national money – rather than free-standing monetary units at the mercy of speculative whims. In short, they promise the functionality of a global, decentralised blockchain combined with the familiarity, and regulatory acceptance, of the fiat regime.

Stripe CEO Patrick Collison dubs the resulting combination “room-temperature superconductors for financial services” – an analogy with the Holy Grail of electrical engineering that would permit near-frictionless transmission of energy. No doubt that’s a touch of hype. Stablecoins have had their niggles too. Tether, the largest of today’s providers, was fined $42 million in 2021 by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission for inaccurately representing the collateral it held.

Still, customers like the concept. In stark contrast to the own-standard crypto complex, the number of active stablecoin users has roughly tripled in two and a half years. Stablecoins, it seems, give the people what they want: constant, real-time access to a globally usable, digital dollar.

[E]ven if Russia’s BRICS Bridge eventually catches on, it’s unlikely to extinguish the “exorbitant privilege” of which then French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard-d’Estaing famously accused the United States as far back as 1965. Far more probable is that Stripe-Bridge reinforces former U.S. Treasury Secretary John Connally’s equally notorious retort: “It’s our currency, but your problem.”

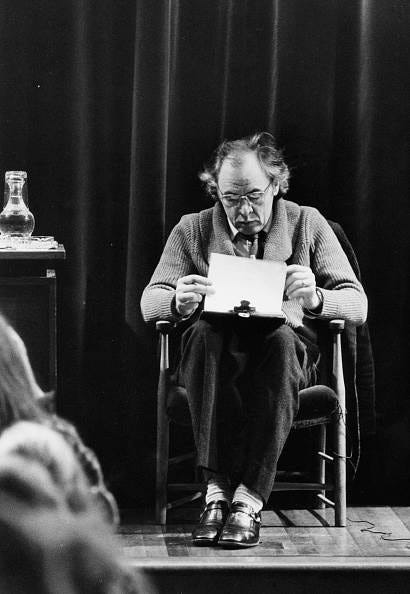

R D Laing asks “who’s the fruitcake?”

His son’s bio suggests RD.

Peter Owen reviews R D Laing: A Biography by Laing’s son Adrian.

When R D Laing was thirty-six, he wrote in his diary: ‘I feel I am going to become famous, and receive recognition. Most of my work has not “hit” the public yet. Eventually it will, like the light of a dead star.’ Within a year of that entry, the light of the dead star had arrived, and Laing had become one of the gurus of the Sixties – together with Timothy Leary, Alan Watts, Herbert Marcuse and Allen Ginsberg.

The result, as described by his son Adrian in this frank and sometimes brutal biography, was disastrous. For the next twenty years, like a fly hit by fly spray, Laing flew around in a euphoric daze punctuated by broken relationships, drunken brawls and fits of depression. When he died of a stroke at the age of sixty-one, his latest book had been rejected by several publishers, and he had been struck off the Medical Register.

Laing walked out on his young family soon after fame arrived, so he was a relative stranger to Adrian and his brother Paul when he invited them to a conference in a Christian residential community in 1974. It was a memorable occasion. They were already late for dinner when Laing persuaded a Glasgow cab driver to try and find ‘Fatima House’, somewhere near Kilmarnock. By the time they had stopped at every pub on the way, all three were staggering drunk, and Laing had vomited in the back of the cab. At midnight he thundered on the door until everyone in the house was awake; then, admitted to the hall, he rushed up to a statue of Jesus with the comment, ‘Just the man l want to talk to’, and proceeded to fondle the statue intimately and slobber over its behind while his sons screeched with laughter on the floor. Typically, Laing delivered a serious and thoughtful lecture on sin and redemption the following morning.

Understandably, Adrian Laing developed a considerable admiration for his father. This began to wear thin in the mid-Eighties, as he began to gauge the extent of Laing’s self- destructiveness. Called to the Hampstead police station in the middle of the night (Adrian was by then a lawyer), he learned that his father had been arrested after throwing a bottle of wine through the window of the Rajneesh Centre and shouting rude comments about ‘the orange wankers’. He was also found to be in possession of cannabis. A few days later, turning up at the police station to be charged, he was so drunk that the police declined to charge him. ‘Good,’ shouted Laing, ‘then all I have to do is to stay fucking drunk.’ Finally persuaded to plead guilty, he was given a conditional discharge. …

Laing was a lifelong depressive. My own view is that although a naturally brilliant therapist, he also had very little to ‘say’ – in the sense that Freud and Jung had so much to say. This explains why some of his most famous books, like The Politics of Experience and Knots, are so short.

He had another problem. His views achieved such an impact because he was prone to exaggerate – as in the famous comment that from the moment of birth ‘the baby is subjected to forces of outrageous violence called love’, and that the mother and father ‘are mainly concerned with destroying most of its potentialities’. All this sounded arresting against the background of the leftist and revolutionary rhetoric of the Sixties, but was bound to sound less convincing as time placed it in rational perspective. So, after a period of meditating in Ceylon and India in the early Seventies, Laing came back to find that his serious reputation was beginning to fade. It was at this stage that he put on dark glasses and went into the guru business, advising his audiences to drink Perrier water, and practising a dramatic form of therapy called ‘rebirthing’ that involves much noise and confusion. But as his second marriage broke up, Laing went into the cycle of depression and heavy drinking that was finally to kill him. …

This book made me think of Goethe’s comment ‘Beware of what you wish for in youth, because you’ll get it in middle age.’ But I also found that it brought me a real understanding of a man who was sensitive, decent, and – like so many Scots – too clever for his own good.