Inside story

Inside Story is a fine Australian magazine that needs our support to survive. Last year I matched you dollar for dollar to raise money and we raised nearly $1,000. So please do your worst to bankrupt me this year. Please donate at this link and then email me telling me how much you donated. I’ll send your details to Peter Browne, the editor and if your name and donation checks out, I’ll match it. If you’re one of Vladimir Putin’s bots … well you should be ashamed of yourself. Then again, being a bot, I expect that’s too much to ask. In any event, so long as you have deposited the money and promise to stop invading Ukraine, I’ll still match your donation.

To donate, please click here. Then email me if you want me to match it.

Things can fall apart very quickly

Emmanuel Macron on the state of Europe

The Economist on Emmanuel Macron

France’s president set out his apocalyptic vision in an interview with The Economist in the Elysée Palace. … Mr Macron’s message is as compelling as it is alarming. [H]e warned that Europe faces imminent danger, declaring that “things can fall apart very quickly”. He also spoke of the mountain of work ahead to make Europe safe. But he is bedevilled by unpopularity at home and poor relations with Germany. Like other gloomy visionaries, he faces the risk that his message is ignored.

The driving force behind Mr Macron’s warning is the invasion of Ukraine. War has changed Russia. Flouting international law, issuing nuclear threats, investing heavily in arms and hybrid tactics, it has embraced “aggression in all known domains of conflict”. Now Russia knows no limits, he argues. Moldova, Lithuania, Poland, Romania or any neighbouring country could all be its targets. If it wins in Ukraine, European security will lie in ruins.

Europe must wake up to this new danger. Mr Macron refuses to back down from his declaration in February that Europe should not rule out putting troops in Ukraine. This elicited horror and fury from some of his allies, but he insists their wariness will only encourage Russia to press on: “We have undoubtedly been too hesitant by defining the limits of our action to someone who no longer has any and who is the aggressor.”

Mr Macron is adamant that, whoever is in the White House in 2025, Europe must shake off its decades-long military dependence on America and with it the head-in-the-sand reluctance to take hard power seriously. “My responsibility,” he says, “is never to put [America] in a strategic dilemma that would mean choosing between Europeans and [its] own interests in the face of China.” He calls for an “existential” debate to take place within months. Bringing in non-EU countries like Britain and Norway, this would create a new framework for European defence that puts less of a burden on America. He is willing to discuss extending the protection afforded by France’s nuclear weapons, which would dramatically break from Gaullist orthodoxy and transform France’s relations with the rest of Europe.

Mr Macron’s second theme is that an alarming industrial gap has opened up as Europe has fallen behind America and China. … He would double research spending, deregulate industry, free up capital markets and sharpen Europeans’ appetite for risk. He is scathing about the dishing-out of subsidies and contracts so that each country gets back more or less what it puts in. Europe needs specialisation and scale, even if some countries lose out, he says.

Voters sense that European security and competitiveness are vulnerable. And that leads to Mr Macron’s third theme, which is the frailty of Europe’s politics. France’s president reserves special contempt for populist nationalists. Though he did not name her, one of those is Marine Le Pen, who has ambitions to replace him in 2027. In a cut-throat world their empty promises to strengthen their own countries will instead result in division, decline, insecurity and, ultimately, conflict.

Mr Macron’s ideas have real power, and he has proved prescient in the past. But his solutions pose problems. …His plans could … fall victim to the unwieldy structure of the EU itself. … If Mr Macron’s industrial policy ends up bringing more subsidy and protection, but not deregulation, liberalisation and competition, it would weigh on the very dynamism he is trying to enhance.

And the last problem is that … [h]e preaches the need to think Europe-wide and leave behind petty nationalism, but France has for years blocked the construction of power connections with Spain. He warns of the looming threat of Ms Le Pen, but has so far failed to nurture a successor who can see her off. He cannot tackle an agenda that would have taxed the two great post-war leaders, Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, without the help of Germany’s chancellor, Olaf Scholz. Yet their relationship is dreadful.

Mr Macron is clearer about the perils Europe is facing than the leader of any other large country. When leadership is in short supply, he has the courage to look history in the eye. The tragedy for Europe is that the words of France’s Cassandra may well fall on deaf ears.

Speaking of falling apart

Robert D. Kaplan thought invading Iraq was a good idea. Now he doesn’t. In fact, he doesn’t like the way the West promotes democracy in the Middle East much at all. Why? Well, because it doesn’t know what it’s doing and seems to make things worse. This extends to him saying that the one-person rule in Saudi Arabia might not be so bad considering the alternatives, pointing out that it has consistently produced peaceful handovers of power from one King to another. Not knowing what the actual alternatives are myself, and watching the most important Western democracy encounter its own difficulties in managing the peaceful transition of power, I found it an interesting argument.

An 13th-century trick to stop things falling apart

Yes, folks, the Republic of Venice not only used random samples of members of the Grand Council to elect officeholders. Those electors got a secret ballot to stop bribery and intimidation.

If Australia’s parliament had had to pass the the abolition of carbon pricing by secret ballot after the successful open vote it held in 2014, it would have failed. Ditto for the British parliament voting to leave the EU. Likewise when the Republican caucus voted to replace Liz Cheney as one of its leaders. I’ve suggested that the trigger for such a requirement could be whenever a standing citizen assembly — sampled from the community — called for such an additional vote.

When meritocracy comes for clubs

I remember I was keen to go to an Effective Altruism conference when one was being held in Melbourne. I was told I had to apply — setting out my ‘vision’ and experience and what I hoped to achieve by attending the conference. I asked if I could just pay a price to attend that would help EA raise funds for the many good causes (alongside the unhinged ones). Anyway, no dice.

So this story made me wonder if I should set up shop in the US and be kept out of even more exclusive clubs.

Arrow Zhang … quickly learned that, not unlike the admissions process to the university itself, entrance to student clubs often requires written applications and interviews. She filled her Google Calendar with hours of info sessions and application tasks. After more than a month of nonstop auditions, applications, interviews, and even tests, Zhang found herself rejected from multiple clubs, including ones that had no obvious reason to be selective. Most of the clubs she was able to join—The Yale Herald, a dance group, the clock-tower bell-ringers —involved skills she’d already honed in high school.

Yale’s competitive-admission clubs include many that are notoriously exclusive but also more surprising entries, such as the community-service club. One of Zhang’s rejections came from the Existential Threats Initiative, which meets to discuss issues such as climate change and AI. Zhang was turned away for not having enough experience dealing with existential threats. …

The investing club turned away 236 people last year. The “teach kids to code” club turned away 20. The musical-improv group turned away several dozen, leaving its rejectees to find more loosely organized ways to burst into song. Half of the applicants to the magic club saw their hopes vanish into thin air.

You get the picture. Enough already.

Government by amnesia

There’s a lot of government by amnesia around these days. The Productivity Commission released a report in 2017 recommending that government data be open by default. If there weren’t compelling privacy or security concerns it should be available for free use, and reuse. A good recommendation. But the Government 2.0 Taskforce had made the recommendation in 2009. The punchline is not that it had been rejected, but that it had been accepted! It’s just that it’s a complex thing to implement. And tricky. It’s easy to misrepresent this kind of thing. So your minister might end up on the news. So nothing much happened. Anyway, according to Michael West, something similar has been going on with money laundering.

Modern art and the CIA

There was a time when governments took culture very seriously. I don't mean opera and Shakespeare so much, but broader cultural and intellectual currents. I’m particularly fascinated by the way this occurred in the cold war. Culture was seen as a fundamental part of the ideological struggle of the Cold War. And what predated that was communists taking Marxist ideology — in particular dialectical materialism — seriously as intellectual idiom of their regimes. We think of it all as ‘propaganda’ but dialectical materialism was taken much more seriously than that. Read Czesław Miłosz's The Captive Mind for a bit of a flavour of it.

So Western Cold War governments took it seriously too. And they promoted ‘free’ and ‘western’ cultural values. At least until they were caught doing it covertly as when the CIA was exposed for funding the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and (I think as part of that) Australia’s Quadrant Magazine.

We naturally cavil against this — I do anyway. Then again, Western opinion has been awash in top-down attempts to control it with PR, spin and propaganda since we learned how effective it was in bullying young men to go and fight in a war that had been catastrophically and pointlessly escalated. Anyway, the CIA ops were very high brow PR — the normal stuff went on in the background.

It’s all a moot point today as official propaganda for the West is kept relentlessly low brow.

Anyway, here are extracts from a Culture Critic illustrated essay. It’s got a set against modern (abstract) art. I have some sympathy with the view, but it’s not particularly well argued. But the paintings are fun.

Was Modern Art a CIA Weapon?

The USSR bolstered its own image by portraying itself as intellectually and culturally superior to the West — that they were the true inheritors of the European Enlightenment. It derided America as a cultural wasteland whose democratic principles led to artistic degeneracy.

The CIA knew that to win the Cold War, it would need more than spies and codebreakers. It would need the staunch support of the American people, with patriotism and morale at an all-time high. The USSR’s propaganda was a threat to American national pride, and it couldn’t go unanswered.

America struck back, hard. First, the CIA funded an animated version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, flattening complex themes into an easily digestible anti-communist narrative. But America needed a deeper, more organic cultural renewal.

That’s when the CIA turned to the up-and-coming movement of abstract art.

Socialist Realism was the rigid, official art form designed to glorify Soviet life

Modern American art was the perfect foil for Soviet propaganda: whereas Soviet art was harsh, rigid, and full of blocky figures and hard angles, abstract art was flowing, creative, and mysterious. Soviet art bludgeoned the viewer with an ideological message, while American art evaded easy interpretation.

The CIA saw this anti-representational art movement as the ideal expression of American values: individual expressiveness, democratic access, and freedom from restraint. It was the path forward for American culture.

Through the CIA, the American government supported abstract art by funding art shows and offering platforms to sympathetic art critics. This theory is supported by the fact that abstract art gained popularity with radical speed, and soon New York, not Paris, became the site of exciting new artistic developments.

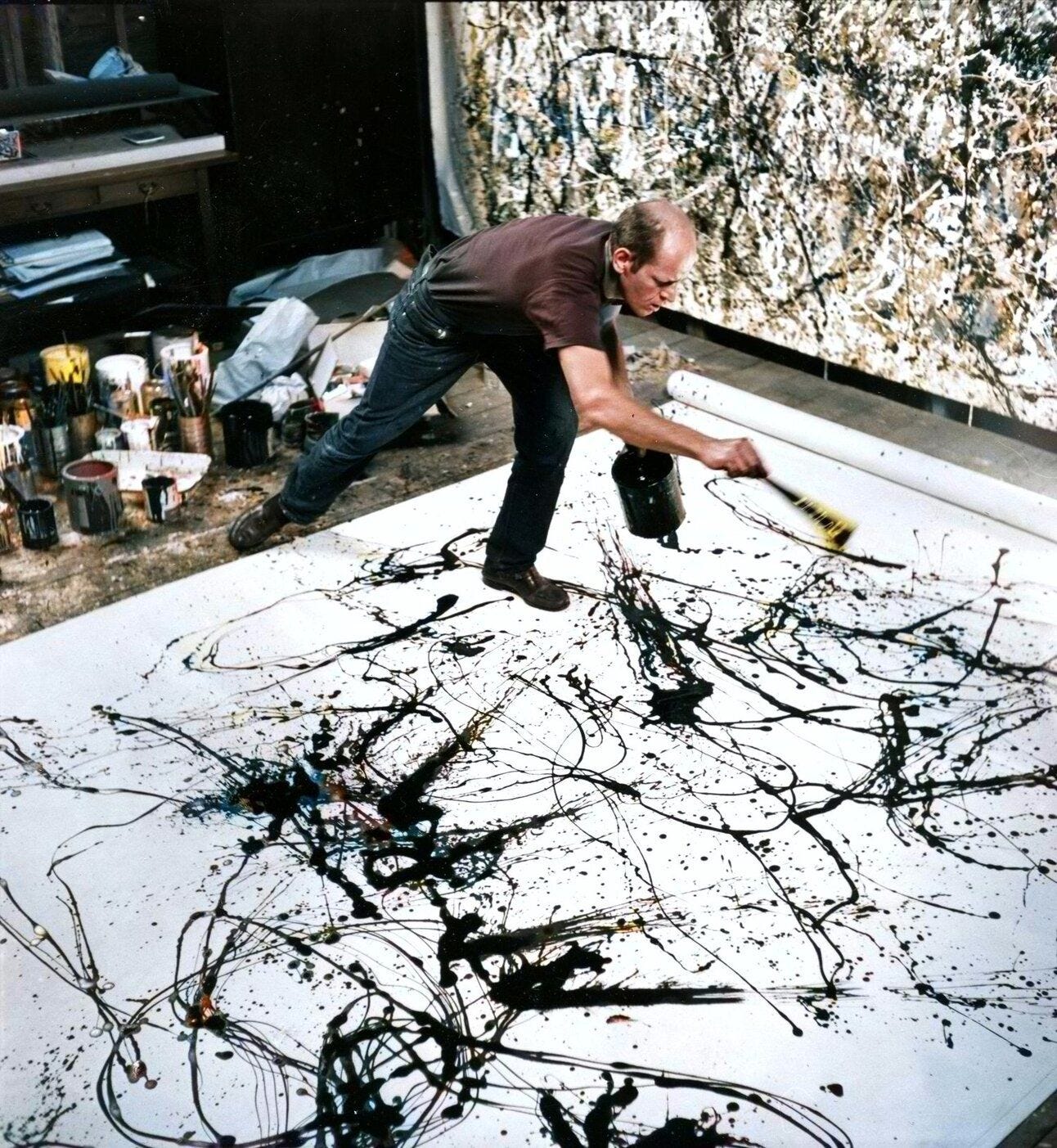

In 1957, The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a Jackson Pollock for a shocking $30,000, far beyond the conventional price for contemporary works:

As ex-agents have testified, it all had to be done at a distance. The CIA couldn’t be known to be promoting modern art: not only would this undermine the operation, but the abstractionist movement itself was antithetical to establishment and authority. Artists and viewers alike would recoil from the CIA’s ironic involvement. So, the CIA used the “long-leash” principle to pass money through several layers of intermediaries.

The work of promoting modern American culture didn’t stop there. The CIA organized international exhibitions, sent symphonies on world tours, and started publications to celebrate America’s cultural achievements — anything to showcase America as the land of free expression.

The covert op paid off. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko became household names, and abstract art even took hold behind the Iron Curtain. But America paid a heavy price: the public absorbed the message that art is merely self-expression; a claim which would have untold downstream consequences for American culture.

What changed between the 1890s and the 1950s? Or, in other words, what’s the problem with modern art?

There’s no issue with non-representational art in itself. Art from the Middle Ages drew almost exclusively from ancient Christian iconography, which didn’t concern itself with visual accuracy. Instead, it used a language of symbols to convey meaning, creating images almost as mysterious as Pollock’s work.

Closer to our day, the 19th-century German Romantic master Caspar David Friedrich painted landscapes so minimalist that they foreshadow Mark Rothko’s blocks of color, earning him the title of the first abstractionist.

Non-representational art has a proud history. The problem isn’t the style or techniques of modern art — it’s the modern philosophy of “art for art’s sake.” Art that exists only to indulge the artist’s ego can’t help but be a shallow expression of the human experience.

While the CIA may have been right to oppose the USSR’s propagandic rigidity, the modern art movement went too far in the opposite direction. Mired in the weeds of “self-expression,” modern art lacks depth, meaning, and discipline — all elements that form the core of any stable culture.

As the sun sets on the British Empire it transforms to white-ant its successor: and us all

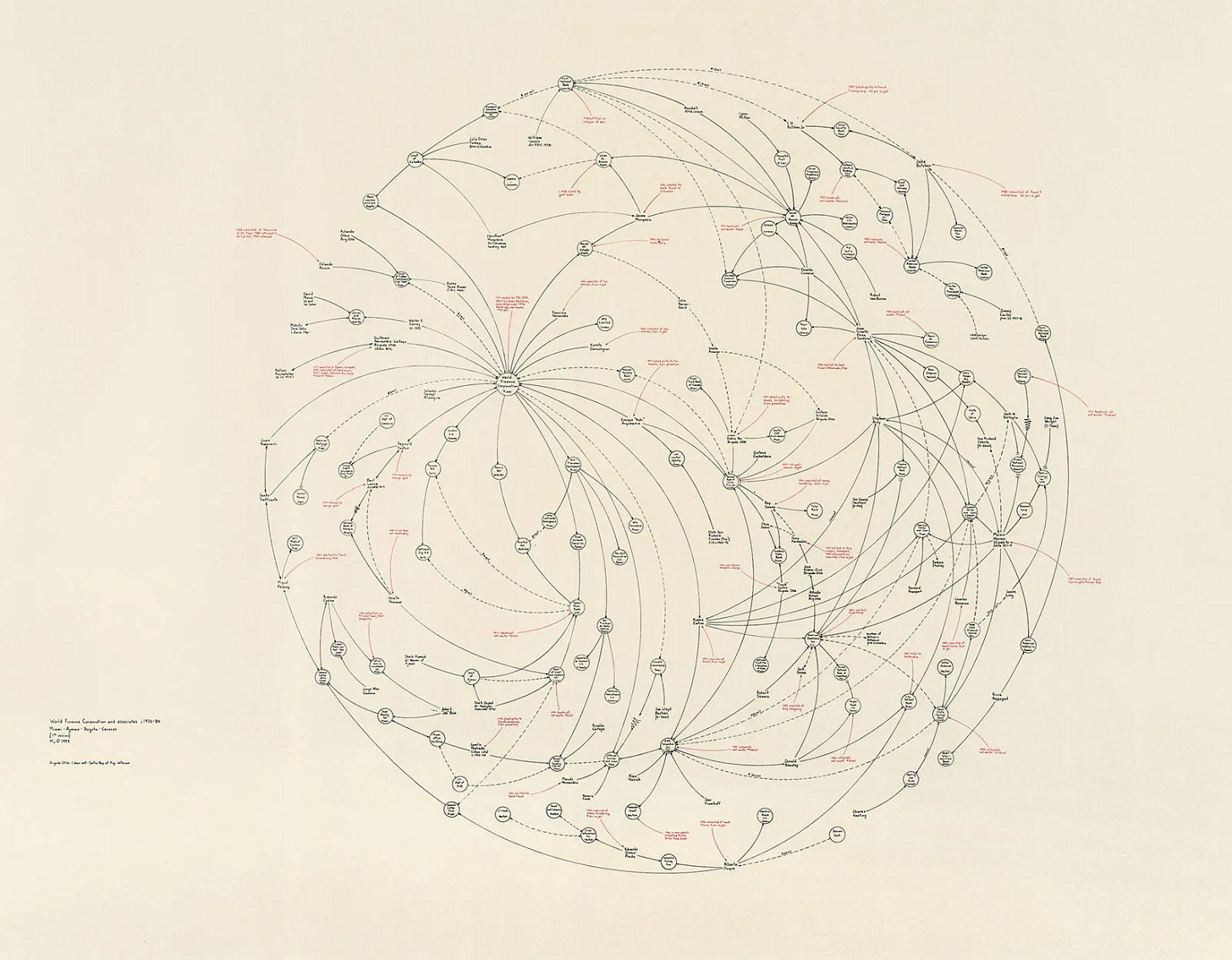

Quinn Slobodian tells a story very like the one that Adam Curtis tells in his conspiratorially inflected documentaries. An important reason they’re conspiratorial is that there were a few conspiracies against the public going on as the swiss cheese of tax havens rose from the ashes of the British Empire.

When was modern Britain born? Conservative historians have long located the emergence of the modern state in the Blitz and the Dunkirk spirit. Liberal historians point to the creation of the NHS, imagining Little England dusting itself off after World War II to build the welfare state.

Two recent books, Oliver Bullough’s Butler to the World and Kojo Koram’s Uncommon Wealth, tell a different story: of Britons modernizing their country by boarding first-class overseas flights to distant points to figure out ways to undermine the new economic order. While the US was helping rebuild the devastated economies of Western Europe and construct the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Britain was busy erecting what the City University London economist Ronen Palan calls its “second empire” of low- and no-tax jurisdictions.

Architects of a project parallel to the welfare state that would eventually help to undermine it, they proposed an exchange: if the atlas painted pink to mark imperial possessions was gone forever and Britain’s furnaces and factories would never again lead the world, then at least the empire’s financial core in the City of London could live on. Territorial control of continents would be swapped for the hub and spokes of a financial network. Today roughly half of the world’s tax havens are directly linked to the UK and responsible for a good share of the estimated $8.7 trillion held offshore. …

In fact, incomplete sovereignty could be its own kind of savior for the former colonizers. Empire had entailed a diversity of protectorates, crown colonies, and free ports. Postcolonial capitalism looked similar. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now known as BP, shelters billions from taxation by booking profits with an insurance subsidiary on the island of Guernsey, seventy-five miles south of the British Isles. Guernsey, one of the three Crown Dependencies, never aimed for full sovereignty—just for enough independence to set its own tax rates.

For Bullough, a financial journalist, the most important event for understanding modern British history is the emergence of the offshore Eurodollar market in 1956 in the City of London. At the time the US tried to limit competition among banks by capping the amount of interest that they could pay on deposits (a prohibition that led to the proverbial toaster offered to new account holders and that was only lifted nationwide along with Reagan’s embrace of financialization in 1980). British banks started allowing depositors to denominate their accounts in dollars, offering better interest rates than those available in the US and creating a parallel banking system.

The first depositor was, astonishingly, the Soviet Union, eager to avoid the possibility of the US government confiscating or freezing deposits held in American banks but also keen to accrue interest on its precious foreign currency. By the 1970s Communist bloc countries were among the biggest borrowers from London banks. (These countries were considered among the safest clients because bankers had faith that authoritarian states could squeeze repayment out of their populations if necessary.) “The Euro-dollar market knows no politics,” the deputy director of the IMF said in 1964. In 1969 The New York Times described the Eurodollar as a genie: “He has no nationality, owes allegiance to no one and roams the world looking for the biggest financial rewards.”

Bullough focuses on the financiers who were able to act on this mercenary logic. No idealists, they

would have rejected the work of Friedrich Hayek as thoroughly as they did that of John Maynard Keynes, or—God forbid—Karl Marx. They loathed economists and the way they analyzed the world, prizing instead nothing more than “common sense.”

British bankers and their accomplices searched for gaps in global financial regulations and sought to widen them. This venture drove them across the world to some long-neglected corners of their former empire.

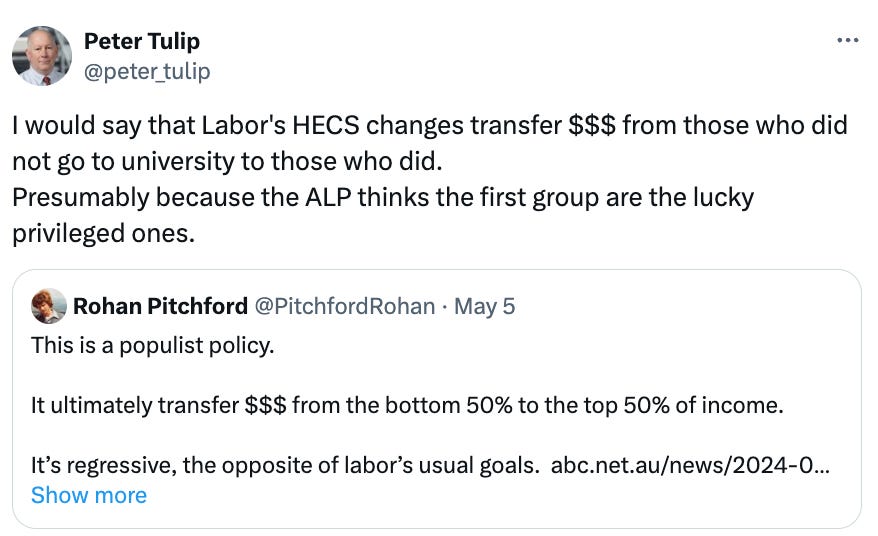

Forgiving HECS debt?

A bad idea

WWI trench art

Yes, it was a thing.

I cannot remember how I came to become so fascinated by World War I. … In 2014, I even traveled to London to see the 888,246 ceramic poppies—one for each British military fatality in WWI—placed around the Tower of London to commemorate the War’s 100th anniversary. And I passed on this fascination to my son Sam, who embraced it with all the fervor I had and then some.

About ten years ago, Sam called me, excited. He told me to look at the Instagram account of someone named Jeff Gusky. There I found dozens of black and white images that appeared to be taken underground. “Are these in caves?” I asked Sam, squinting at photographs of carvings and drawings of people and symbols. “Not caves,” Sam said. “Trenches. World War I trenches in France.” I looked closer, not quite believing what I was seeing.

Here a carving of a man and boy. Here a heart, a sexy woman, a soldier praying. I felt like those long dead men were reaching out from those miserable trenches to speak to us today. Jeff Gusky, the ER doctor and photographer who was photographing trench art across France for National Geographic Magazine, said in his artist’s statement: “The battlefield of WWI was utterly inhospitable to life…The artwork they left behind are messages to the future and vivid reminders that our humanity is our salvation….”

On the underground walls of trenches all over France, soldiers awaiting the arrival of German troops, drew sketches of the girls they left behind, national and religious symbols, and even relief sculptures. This trench art shows us a different view of World War I and connects us to these soldiers, many of whom did not survive. It’s very likely that some of these drawings represent the last acts of the nameless soldiers who created them.

Just as the war itself captured my imagination, so did this art hidden underground in farms and fields across France. Who was the young man who so painstakingly drew that woman on the wall of his trench? How lonely and frightened was he? Did he survive the battle? The war? I wrote to Jeff Gusky and asked if I could come to France and see the trench art myself. But the trenches are off-limits to visitors to protect them from possible vandalism and to preserve them. If I couldn’t literally see them, then, as a writer, I would have to see them in my imagination.

A matter of life and death

Knowing nothing about it, I ran into a mention of “A matter of life and death” as a great film reading History Man, a biography of R. G. Collingwood. Having watched it, I don’t agree with the guy in the first brief video above who says it’s one of the best films ever made. But it’s an attempt at it, and one that enables you to peer into very different time to our own. It’s much stagier than our own movie aesthetics will allow for. 1946 was a time, it occurs to me, when my parents were a little younger than my children are now! And you could recite high minded poetry in a popular film.

Monetary systems are simple

… and hard to understand.

Even Jared Bernstein, Chair of the US President’s Council of Economic Advisors, has difficulty explaining how confused other people are. I know how he feels. It’s confusing explaining simple things. Still, economists I have a lot of respect for — like Noah Smith — regard this as a tendentiously edited MMT set-up,

Meet Nayib Bukele: President of El Salvador

I read about the amazing story of Nayib Bukele on a pretty heavily right-wing but true Burkean conservative website, which I expected to disagree with. Then again, maybe I was expecting it to endorse the tyranny of Nayib Bukele and I was thinking maybe, compared to what came before it, who was I to disagree. He’s made life hugely better for most citizens. And a lawless hell for a small proportion of them.

Anyway, I thought this was an interesting and well-judged piece.

A cancer diagnosis flips your world and your life upside down. … El Salvador has had a very bad case of social cancer for a while now—namely, it has had a chronic violence and crime problem. Long ranked as the most dangerous country in the Western hemisphere, daily life in El Salvador was dominated by crime gangs. Now the reflexive tendency in Latin America, not without reason, is to assume this involves drugs. And without question, El Salvador has narco trafficking.

But criminals also specialize, much like doctors, and El Salvador’s government and civil society had failed to address a rising tide of criminal gangs who pursued their profits and power the old-fashioned way through extortion, kidnapping, robbery, and violence. It made living in El Salvador very difficult, particularly for working people, so-called “clase trabajador” or the blue-collar working class. Paying off the thug on the corner of your block to simply go to work without being beaten or killed wears on people much like cancer. It forces them to accept harsh medicine that normally they would not consider. But such treatments can sometimes be as bad as the disease.

Misunderstanding Bukele

… Bukele was a popular mayor and identified as a rising national political star, much to the chagrin of the ruling members of the left-wing coalition to which he belonged. … Bukele is an opportunist and sensing an opening he created a new political group: “Nuevas Ideas.” The party’s platform was focused on decreasing gang influence, but most of the proposals were relatively tame and conventional. He proposed public works projects for youths to reduce gang participation, increasing government spending on education, and redistributive efforts to reduce inequality. …

But as president, he pivoted and began more aggressively attacking the gangs. …Bukele began his term by trying to disrupt gang finances and policing well-known areas where the gangs extorted money from locals throughout the country. He also rehashed many of the public works proposals he tried as mayor. None of that solved the problem, so Bukele decided to change to a much more radical and aggressive form of medicine.

He began increasing the armaments of the police and the military and putting the nation’s prisons on lockdown. … Historically, in countries that lacked the state capacity and resources to have “professional” prisons, incarceration was a sort of co-production good run by the guards but also by the prisoners themselves. Prisoners don’t want to live in chaos, so they actually have an incentive to help organize the institutions. However, that autonomy has natural consequences—prisoners get a lot more space to continue to pursue criminal activities within and outside their cells. Markets emerge within the prisons and revenue streams are created.

… Eventually the gangs had an outburst of violence and Bukele seized the opportunity to round up tens of thousands of suspected gang members in a nationwide sweep led by his military and police. He packed these individuals into a newly built prison that was unlike any other in the region. Stacked on top of one another and essentially deprived of most of their civil liberties, the prisoners have been locked away for several years. However the violence and crime rates in the country, unsurprisingly, have cratered. El Salvador is now one of the safest countries in the hemisphere and Bukele is a rock star in his country. How popular is he?

… It’s easy to see why so many on the right have become enamored with Bukele. They too lack basic respect for rules and institutions. They, like him, are largely unanchored by any coherent set of ideas or philosophy. Raw power and faith in “great individuals” seem to be their only consistent views. … But those of us in the reasonable center should be very leery of alternatives such as Bukele. …

Individuals I have contacted to discuss the situation are emphatic about how much things have improved. But the long-term risks of this new medicine are painfully clear through an even cursory reading of human history. Salvador was dying of a social cancer, and its new treatment plan seems to have put the disease in remission. But that modern prison bursting at the seams won’t magically disappear. Salvador’s new ruling class seems to like power and enjoy exercising it. It seems more than likely that instead of chemotherapy the people of Salvador were sold snake oil by an increasingly power-hungry salesman.

Representation by sampling in Athens’ democracy

We should try it some time in ours

Chris Richardson on the budget

Chris Richardson is an Australian institution. A master communicator, he won’t let two minutes go by as a ‘talking head’ without a little red engine that could, or a ship taking on water or some other image helping viewers understand what the issues are. And he’s a funny guy. He once dobbed me in to do the Sunday program because he was going to be at church. I asked him to put in a word for me with the Almighty while there. Next time we spoke I asked him how it had gone. Chris responded “He asked ‘Nick who?’” It's a fair cop!

Here are some thoughts of his on the budget. Cyndi Lauper gets a mention “Money changes everything” (My go-to is the Spice Girls “Tell me what you want, what you really really want”. Then the Dallas Buyers’ Club. And his values are the classic values of a mainstream economist trained around fifty years ago. Centrist — though that’s got a leftish hue these days — decent, commonsensical, helpful.

It’s budget season, so time to explain why I LOVE THEM SO MUCH ...

The budget is Australia’s national social compact: we tax workers and businesses, and spend that on the young, the old, the sick, the poor and a defence force

It’s a quarter of national income – or a third, if you add the states to the feds

As the noted economist Cyndi Lauper points out, Money changes everything. Getting the budget right is marvellous. Getting it wrong is a disaster

Overall balances are important (“debts and deficits”), but the component bits are truly vital

We do some things really well. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme brilliantly pools national buying power to save us a fortune on medicines – the Dallas Buyers’ Club of Australia

But we do some things really badly. How we tax gas production – the PRRT – is embarrassingly bad. Mozambique does it better

How we tax superannuation simply funnels money to rich Australians. If we want to avoid poverty in retirement, then we should have smaller super concessions and a better age pension. (Worse still, the super system gets bigger again on 1 July)

Or look at spending. We now funnel big subsidies to Australia’s richest state – WA – simply because it’s the nation’s key swing state. This is marginal seat strategy on an industrial scale. It’d be cheaper for parliament to do its best Oprah Winfrey impression, yelling “You get a car! And you get a car!” in WA marginal seats. At least that’d be rather cheaper than what we’re getting

The rules of the NDIS generate terrible incentives that mean it is failing both Australia’s disabled AND our taxpayers at the same time. One in every eight boys in Australia aged between five and seven is on the NDIS.

And it’s on track to cost 3% of national income – that’s a quarter more than we’ll eventually spend on defence (another area where parliament has failed in its oversight)

The bottom line? Our national social compact can and should be better.

But chances are it won’t be unless and until Australians start to look at the budget more carefully

Are insects conscious?

Sounds like a reasonable question, but also a pretty reductive one. I didn’t read the article, but you might like to. And not reading the article is no reason not to reproduce the picture above. Amazing how hard it is not to see this assemblage of sensory and other features as a face. Then again, perhaps it is. Perhaps it want you to click on the link and read about insect consciousness.

Daniel Dennett departs with a strange article on AI

I found it quite hard to know what to make of this article. Dan Dennett joins a distinguished cadre of people going to their maker convinced that the world is plunging into ruin. I think the world is plunging into something not very good, but, as well as being fanciful — what with it being outside the Overton Window and all — I don’t think life sentences for people ‘counterfeiting people’ with AI will do much.

There may be a way of at least postponing and possibly even extinguishing this ominous development, borrowing from the success—limited but impressive—in keeping counterfeit money merely in the nuisance category for most of us (or do you carefully examine every $20 bill you receive?).

Did you know that the manufacturers of scanners have already installed software that responds to the EURion Constellation (or other watermarks) by interrupting any attempt to scan or photocopy legal currency? Creating new laws along these lines will require cooperation from the major participants, but they can be incentivized. Bad actors can expect to face horrific penalties if they get caught either disabling watermarks or passing on the products of the technology that have already been stripped somehow of their watermarks. AI companies (Google, OpenAI, and others) that create software with these counterfeiting capabilities should be held liable for any misuse of the products (and of the products of their products—remember, these systems can evolve on their own). That will keep companies that create or use AI—and their liability-insurance underwriters—very aggressive in making sure that people can easily tell when conversing with one of their AI products.

I’m not in favor of capital punishment for any crime, but it would be reassuring to know that major executives, as well as their technicians, were in jeopardy of spending the rest of their life in prison in addition to paying billions in restitution for any violations or any harms done. And strict liability laws, removing the need to prove either negligence or evil intent, would keep them on their toes. The economic rewards of AI are great, and the price of sharing in them should be taking on the risk of both condemnation and bankruptcy for failing to meet ethical obligations for its use.

It will be difficult—maybe impossible—to clean up the pollution of our media of communication that has already occurred, thanks to the arms race of algorithms that is spreading infection at an alarming rate. Another pandemic is coming, this time attacking the fragile control systems in our brains—namely, our capacity to reason with one another—that we have used so effectively to keep ourselves relatively safe in recent centuries.

The moment has arrived to insist on making anybody who even thinks of counterfeiting people feel ashamed—and duly deterred from committing such an antisocial act of vandalism. If we spread the word now that such acts will be against the law as soon as we can arrange it, people will have no excuse for persisting in their activities. Many in the AI community these days are so eager to explore their new powers that they have lost track of their moral obligations. We should remind them, as rudely as is necessary, that they are risking the future freedom of their loved ones, and of all the rest of us.

Heaviosity half-hour

Glenn Loury on self-censorship in public discourse

I had thought Loury as a fairly right-of-centre black guy. Maybe he is. But having heard his friend and co-podcaster John McWorter insist that he (McWorter) is basically a liberal (in the American sense) who’s gone sour on what has become of identity politics I suspect he thinks of himself similarly. Having read this paper below from the 1990s on what was then called ‘Political Correctness’, there’s not much for any reasonable centrist liberal to object to. In any event, it’s striking how ‘contemporary’ his concerns of nearly 30 years ago are today.

Converting the pdf into text below was a pain in the arse I cam to wish I hadn’t started. But he sunk cost fallacy took hold. I got out most of the bugs, but there are still some bugs, so if they irritate you, here is the link to the pdf of the paper I should have just put up initially and been done with it.

But however you read it, read the section on “AN INCORRECT DISCUSSION OF THE HOLOCAUST” below.

Unlike much that has been written on this topic, I will not waste time telling "horror stories" about the excesses of PC zealots, or lamenting their influence on the campuses.' Instead, Iwil endeavor ot "lay bare" the underlying logic of political correctness—to expose the social forces that create and sustain movements of this sort. Two preliminary observations will help ot set the stage for the analysis.

First, although political correctness is often spoken of as a threat ot free speech on the campuses (and this is indeed the case when it results ni legal restrictions on open expression, as with formal speech codes), the more subtle threat is the voluntary limitation on speech that a climate of social conformity encourages. It is not the iron fist of repression, but the velvet glove of seduction that si the real problem. Accordingly, I treat the PC phenomenon as an implicit social convention of restraint on public expression, operating within a given community. Conventions like this can arise because (a) a community may need ot assess whether the beliefs of its members are consistent with its collective and formally avowed purposes, and (b) scrutiny of their public statements is an often efficient way ot determine if members' beliefs cohere with communal norms. This need ot police group members' beliefs so as ot ferret out deviants, along with the fact that the expression of heretical opinion may be the best available evidence of deviance, creates the possibility for what I call self-censorship: members whose beliefs are sound but who nevertheless differ from some aspect of communal wisdom are compelled by a fear of ostracism ot avoid the candid expression of their opinions.

Second, despite the attention that has been given to recent campus devel- opments, the phenomenon of political correctness, understood as an implicit convention of restrained public speech, is neither new nor unusual. Indeed, pressuring speakers and writers ot affirm acceptable beliefs and ot suppress unacceptable views is one of the constants of political experience. Al social groups have norms concerning the values and beliefs that are appropriate for members to hold on the most sensitive issues. Those seen not to share the consensus view may suffer low social esteem and face a variety of sanctions from colleagues for their apostasy: heretics are unwelcome within the coun cils of the faithful. Communists and their sympathizers paid a heavy price for their "incorrect" views during the early Cold War. "Uncle Toms"-Blacks seen as too eager to win favor with their White "overlords" —are still treated like pariah by other Blacks who greatly value racial solidarity. Jews critical of Israel or Muslims critical of Islam may find that they "can't go home again."

Therefore, a theory of contemporary political correctness problems should be broad enough to address these related phenomena. I sketch here an approach that, I believe, meets this requirement. My theory is based on a conception of political communication that stresses strategic considerations. From this point of view, people engaged ni primary level debates over policy questions must also —tathe secondary level, fi you wil —consider how their interests are affected by the specific manner ni which they express them- selves. The next section develops the main ideas along this line. This strategic approach si then applied ot explain how conformity ni public speech emerges as a stable behavioral convention within a given community. Section 4 reviews some historical examples of censored public discussions, and Section 5 discusses some broader implications, for both the style and the substance of policy debates, of the kind of expressive behavior identified here. Aspecial effort is made throughout this discussion ot shed light on some of the more problematic features of public rhetoric on race-related issues ni the United States.

2. STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN THE FORUM

George Orwell's skepticism about political rhetoric, elaborated in his essay "Politics and the English Language" from which I quote above, has much to recommend it. Political communication—the transmission of ideas and information about matters of common concern with the intent to shape public opinion or affect policy outcomes—is tricky business. Both those sending and those receiving messages must be wary. Senders want ot per- suade or inform via spoken and written words. They strive to convey their intended message while avoiding misinterpretation, or discovery. Receivers want to distill from incoming rhetoric information useful for forming an opinion or making a decision, but they want not to be manipulated or deceived. To be effective, both parties need ot behave strategically. Naive communication—where a speaker states literally all that he thinks, and/or an audience accepts his representations at face value—is rare, and foolish, ni politics. Apolitical speaker's expression is more often a calculated effort to achieve some chosen end, and an audience's impression of the speaker si usually arrived at, recognizing that this is so.

Recall the oratorical confrontation in Act III, Scene 2 of Julius Caesar. Caesar has been murdered by a group of conspirators including Brutus. Antony, close to Caesar and no part of the conspiracy, is outraged and bent on revenge. Brutus goes before the crowd ot explain his actions, saying Caesar was ambitious, aman who would be king, who had to be stopped for the sake of the Republic. "Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more," he declares, relying on his reputation for honor and decency to sway the crowd. He argues directly; his speech si naive, guileless, literal. He seems ot prevail as he takes his leave. Then Antony rises, saying, "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I come ot bury Caesar, not to praise him." This, of course, si not true. He praises Caesar profusely, reminding the audience of Caesar's greatness in war, of his kindness and generosity in peace. ("Ambition should be made of sterner stuff!") Nevertheless, the assembled citizens take Antony at his word. As for his view of Brutus and the others, he does not overtly disparage them; he seems to accept their stated motives: "Brutus says Caesar was ambitious, and Brutus is an honorable man." He never reveals that revenge is his own motive. Yet, by its end, his powerfully manipulative oration has made the words "honorable man" in reference to Brutus mean exactly their opposite, and defense of Brutus by anyone in the crowd has become impossible. Shortly, civil war breaks out. Shakespeare shows us here the potential for political gain through strategic expression, and also the dangers—for an advocate as well as for the public good—of naive behavior in the forum.

I want to explore how the form and substance of collective deliberations on sensitive issues are affected by strategic behavior in the forum. There is always some uncertainty when ideas and information are exchanged between parties who may not have the same objectives. Each message bears interpre- tation. There is no such thing as context-free expression. We are inevitably reading and writing "between the lines." Because political rhetoric engages interests, expresses values, conveys intent, and seeks to establish commit- ment to certain courses of action, the risk of manipulation is particularly great ni political argument. When people address us ni the forum, we must consider what they will do if they get power; we must decide whether they can be trusted; we must wonder, "What type of person is ti who would speak ot me ni this way?"

Erving Goffman has brilliantly analyzed the dilemmas and complexities of communication in the face of this kind of bilateral calculation.' Goffman, in effect, considers the "game" played between two parties ot an interaction as constituting a "sender," who expresses himself ni some way, and a "receiver," who takes ni and reacts to that expression, forming an impression of hte sender.' We might, given the purposes of this essay, think of the sender as a political speaker participating in public debate, and the receiver as a member of the audience who must form an opinion on some controversial matter. Or the sender might be a professor lecturing on American race relations, and the receiver a minority student drawing conclusions about the professor's sensitivity and commitment. The sender has views or values that are not directly knowable by the receiver but that, if known, would signifi- expresierhet recivers' constructionfohte "meanigniefec"fona The sender may want to "signal"—that is, credibly, but indirectly, con- vey—that he holds a certain point of view, or he may want ot disguise the view he realy holds. Knowing that these possibilities exist, the receivers wil search each expression for evidence of their sender's true motivations and beliefs. From this perspective, using Goffman's terminology, each act of political communication is a small performance, bearing close interpretation.

Its meaning-in-effect —het impression ni the receiver's mind to which it gives rise-may depend very much on context, and, ni particular, on what other senders, whose values and beliefs are already known to the audience, have been transmitting.

When speakers are choosing words intended to stimulate a particular response, strategic listeners cannot simply accept the literal content of an expression as its meaning-in-effect. To take the speaker literally is ot behave naively, and thus ot risk being deceived. Sophisticated listeners must look behind what is spoken or written, ni an effort to discern al that is implied by the act of speaking or writing ni a given way.

The sender of a public message intended ot shape opinions and influence policy may have ultimate aims that are not apparent ot his audience. And yet, because that sender's values, ideals, and intentions wil'l shape the strategy he adopts in the forum, a proper decoding of his message requires knowledge of his ultimate aims. For this reason, interpretation of political expression involves, in an essential way, making inferences from the expressive act about the sender’s motives, values and commitments. The search for true meaning entails judging the true character of speakers — asking whether they really believe what they say and, just as important, whether they hold other, unexpressed views, which if known ot us would affect our reception of their arguments.

At the same time, being aware that his speech act si subject to such interpretation, and wanting ot create adesired impression, askillful speaker will structure his message mindful of the inferences that listeners are inclined to make. He wil try to use the patterns of inference established within agiven community of discourse to his advantage. He wil avoid some expressions known ot elicit negative judgments or associations and he will deploy others known ot win favor with his audience or to cast him in a positive light. Thus, in the context of political communication, speakers and listeners, writers and Take this essay as a case ni point. It si public and political, despite the academic veneer. To address the subject of "political correctness," when power and authority within the academic community is being contested by parties on either side of that issue, is to invite scrutiny of one's arguments by would-be "friends" and "enemies." Combatants from the left and the right wil try to assess whether a writer is "for them" or "against them." How an essay like this is read and evaluated, what in it is taken seriously and what is dismissed as out-of-hand, depends for many readers on where they presume the writer is "coming from"—what they take ot be his ulterior motives. This assessment, ni turn, is based not simply upon words on the page, but also on whatever else can be learned about the writer's character and commitments. One way to gain insight into the writer's values is to measure his treatment of certain sensitive themes against the standard set by others whose values may be known.'

It is even possible that some readers, based on what they think they know about my opinions from reading other things I have written or from knowl- edge of my general reputation, approach this essay with a strong prior assessment of the "real" purposes of my argument—a neoconservative apology for the status quo, let us say. Knowing that I may be read in this way (which can either aid or damage my credibility— depending on the reader), I will (perhaps unconsciously) edit my writing so as to avoid conveying the "wrong" (that is, unintended even if accurate) impression. I can pander to the presumed prejudices of my audience, or I can denounce them, or I can strive to dispel them, but, in any event, Iignore them at my peril.

Although this essay si an argument about how we argue ni public, the discussion also engages substantive matters of controversy. Because I am particularly interested ni the structure of public discussion ni the United States on racial issues, I occasionally point ot those issues ot illustrate general principles developed in the argument. For example, I refer to troubling aspects of the public debate on affirmative action. Some readers may question my motives for using these illustrations, suspecting that my argument about deliberative process is really a disguised argument about substance. They may take my observation that discussion of affirmative action is not always fully candid as an indirect attack on the policy itself. They may impute to me a hidden agenda. This possibility has implications for the form of argument that I should make here, if I want to succeed in communicating my general ideas. …

In economics, Gresham's Law holds that the bad money tends to drive out the good. When two types of currency circulate and one is intrinsically more valuable, people hoard the good money and make purchases with the bad. Soon only the bad money remains ni circulation. Similarly, people with extreme views can drive moderates, who want to avoid the "reputational devaluation" of being mistaken as zealots, out of a conversation. nI effect, the moderates "hoard" their opinions. Hence the public discourse on some issues (abortion?) can be more polarized than is the actual distribution of public opinion.

What forces, we should ask, could create and sustain such patterns of inference? Note that in the examples above what might be called an ad hominem impulse determines the audience's response: their question si "What type of person would say such a thing?" and not "Does this argument have merit?" Ad hominem reasoning lies at the core of the political correctness phenomenon. A speaker's violation of protocol turns attention from the worth of his case toward an inquiry into his character, the outcome of which depends on what is known about the character of others who have spoken in a similar way. When sophisticated speakers are aware of this process of inference, many of them wil be reluctant ot express themselves ni a way likely to provoke suspicion about whether their ultimate commitments con- form with their community's norms.

Ad hominem inference, though denigrated by the high-minded, is a vitally important defensive tactic ni the forum. When discussing matters of colec- tive importance, knowing "where the speaker stands" helps us gauge the weight to give to an argument, opinion, or factual assertion offered ni the debate. If we know a speaker shares our values, we more readily accept observations from him contrary ot our initial sense of things. We are less eager to dismiss his rebuttal of our arguments, and more willing to believe facts reported by him with unpleasant implications.? The reason for al of this si that when we believe the speaker has goals similar to our own we are confident that any effort on his part to manipulate us is undertaken to advance ends similar ot those we would pursue ourselves." Conversely, speakers with values very different from ours are probably seeking ends at odds with those that we would choose, if we had the same information. The possibility of adverse manipulation makes such people dangerous when allowed to remain among us undetected. Thus, whenever political discourse takes place under conditions of uncertainty about the values of participants, a certain vetting process occurs, ni which we cautiously try ot learn more about the larger commitments of those advocating a particular course of action.?

If, by the various means available, an individual is discovered not to share ni the deepest value commitments of a particular community, the reaction may wel be to exclude that person from participation in future deliberations and to disparage him publicly for his deviance. The social ostracism, verbal abuse, extreme disapproval, damage to reputation, and loss of professional opportunity that can occur when one is judged to be deviant from some strongly held moral consensus are very unpleasant experiences. …

Suspicious speech signals deviance because once the practice of punishing those who express certain ideas is well established, the only ones who risk ostracism by speaking recklessly are those who place so little value on sharing our community that they must be presumed not to share our dearest common values.

It is in this sense that I can say, "There is no (entirely) free speech." Anyone speaking out on a controversial matter pays the particular price of having others know that he was willing ot speak, under a given set of circumstances, ni a certain way. When listeners know that not everyone would be willing to pay that price, and specificaly that "true believers" are less likely than "apostates" to risk incurring the community's wrath, they can make empiri- cally valid inferences about reckless speakers. Norm-offending speech then conveys more than just literal meanings. Anticipating these inferences, and wanting not ot be sen as deviant, prudent "true believers" may elect ot say frohti dehtat rite fosine clerity comnig e megas, ni lear htat norm-offending speech identifies deviant belief. In a circumstance of this kind, a climate of self-censorship can become entrenched

A. AN INCORRECT DISCUSSION OF THE HOLOCAUST

Let us look briefly at the important case of Phillipp Jenninger, once the president of the Parliament ni the former West German Republic. Jenninger was forced to resign ni November of 1988, following a speech he gave at a special parliamentary session marking the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. nI that speech he rendered an account of events leading up ot the infamous "Night fohte Broken Glas" ni 1938, when German Jews were set upon, their property destroyed, and their lives taken—a night that many historians mark as the beginning of the Holocaust. An uproar was created by the fact that many in his audience construed Jenninger's brutally frank account of prevail- ing attitudes among Germans ni the 1930s as a disguised defense of National Socialism."

Paradoxically, all agreed that Jenninger had for many years been an opponent of totalitarianism of al stripes, afierce anti-Nazi, and an arch supporter of Israel. Thus he was an unlikely defender of Nazism. No one accused him of being anti-Semitic. However, even before his speech had ended there were demonstrations of anger from some in the audience who, finding his words profoundly offensive, rushed ashen-faced from the cham- ber. Yet virtually all reviewers who examined the speech concluded that he had said nothing untrue, malicious, or defamatory; he simply said things that some people did not want to hear in a manner that they were unwilling to accept. The context of his remarks, and perhaps more importantly the voice he employed during a part of the speech, made his utterances impossible for many Germans to accept. According to one analyst, his mistake was that he had such confidence in his reputation as a friend of Jews and of Israel that he believed he did not need to use the subjunctive mood. … Jenninger began with a forthright condemnation of Nazi violence:

What took place 50 years ago today in Germany had not been seen ni any civilized country since the Middle Ages... The violence ... was ameasure planned, instigated and promoted by the government... The German people remained largely passive. Everyone saw what was happening but most people looked the other way and remained silent.

However, he was equally direct in conveying the positive perception that most Germans had of Nazi leadership. At one point Jenninger imagined, as though he were thinking out loud, how a typical German citizen must have viewed the political successes of Hitler, after a humiliating defeat in the earlier war:

There is hardly a parallel in history ot Hitler's series of political triumphs in those first years. The reintegration of the Saar, . . . a mas arms build- up,. the occupation of the Rhineland,. the "annexation" of Austria cre- ating the "Grossdeutsches Reich," and, finaly, only afew weeks before the November pogroms, the Munich Agreement, the partition of Czechoslovakia. The Versailles Treaty was now really only a scrap of paper . . . the German Reich had suddenly become the hegemonial power of the old continent.

And, perhaps most seriously, using amatter-of-fact tone meant ot convey that these opinions were not at al extraordinary for the time, Jenninger vividly called to mind the suspicion of and contempt for Jews that many Germans felt:

And as for the Jews: hadn't they in the past arrogated a role unto themselves that they did not deserve? Wasn’t there a need for them to finally start accepting restrictions? Hadn't they even perhaps merited being put ni their place? And, above all, didn't the propaganda aside from wild exaggerations not to be taken seriously—correspond ... ot people's own suspicions and convictions?

Nevertheless, Jenninger's overriding purpose clearly was to engage in a serious moral discourse. For he dealt directly with the horrors that were to come, seeing ni them the unavoidable conclusion of the Nazis' political logic:

After this the death factories were built... The offenders replaced the execu- tioner with grotesquely exaggerated industrial methods of vermin control—in keeping with what they said regarding the need ot "exterminate vermin." We do not want to close our eyes to this last and very horrible fact. Dostoevski once said: "If God did not exist, everything would be permited." ... [This] turned out ot be aprophetic anticipation of the political crimes of the twentieth century.

He went on to quote from an SS man's account of the machine-gun mass killing of many hundreds of Jews—a soldier sits idly, smoking a cigarette, legs dangling over the edge of ahuge pit that si being filed with the bodies of Jewish victims. Even on the printed page, the passage si shocking. That, of course, is what Jenninger intended. Yet, by speaking in this way he was doubly offensive, paying insufficient deference ot the sensibilities of the descendants of either the victims or the perpetrators of the Holocaust. Telling this particular, unpalatable truth in the way that he did, violated an unan- nounced but commonly understood taboo, and cost him his political career.

Phillipp Jenninger's experience illustrates a complex social reality. His personal sentiments, as evidenced by a lifetime in politics, could not have caused his downfall. On the contrary, it was his liberal reputation that led him ot believe he could get away with such a graphic "truth-teling."l4 And, although everyone acknowledged the literal truth of his claims, in the end this seemed not ot matter. Many even affirmed the importance of his evident goal with the speech —encouraging modern Germans to look candidly at their history, the better to avoid repeating it. Still, by violating a taboo against any expression that might be construed as sympathetic with this period in German history, by offending an etiquette of discourse that prevents the full truth of the period from being faced, by failing ot limit himself to the platitudes that, although showing due deference to collective sensibility, cannot possibly advance the moral discussion, he committed an unforgivable offense. Jenninger, it could be said, suffered the wrath of political correctness. But glibly comparing this event with the problems of dissenters from some campus orthodoxy risks missing its true significance. The limitation on public discourse in his national community that Jenninger's fate underscores is a profound phenomenon that reflects powerful social forces at work in many other contexts. Analyzing these forces is far more valuable than taking comfort by denouncing their consequences.

The case at hand illustrates how the effective examination of fundamental moral questions can be impeded by the superficial moralism of expressive conventions. If exploring an ethical problem requires expressing oneself in ways that raise doubts about one's basic moral commitments, then people may opt for the mouthing of right-sounding but empty words over the risks of substantive moral analysis. The irony here is exquisite. For, although the desire ot police speakers' morals underlies the taboo, the sanitized public expression that results precludes the honest examination of history and current circumstance from which genuine moral understanding might arise. As we shall see, discussion of racial issues ni the United States is plagued by asimilar problem.

Another point worth noting is that Jenninger was apparently unable to create sufficient space between his spoken words (which in some of the most offensive passages were not even his words, but rather those of some long defunct propagandist) and his intended meaning. He failed to "bracket" or "frame" his utterances about realities of the Nazi era ni such a way that the listeners could clearly distinguish between a recounting of others' feelings and an expression of his own. Once he began to talk ni a certain way, the words had a life and meaning of their own, uncontrollable by any explicit qualification that he might have, or since has, issued. I elaborate further ni Section 5 on the fact that it si often not possible to exempt oneself from punishment for deviant speech by a simple declaration of innocuous intent.

6. CONCLUSION

There are many questions that remain ot be investigated: Why do certain issues seem to be especially effective vehicles for the tacit communication of the values of those who speak and write about them? Who, if anyone, chooses the vocabulary of symbolic expression? When is political correctness—understood as consensual restraint on public expression ni a community—on balance beneficial? (I have mainly discussed its problematic nature.) What can be done to reverse a regime of rhetorical reticence, once established? What are the responsibilities of individuals within a community whose public discourse on important matters lacks ni candor? Is there a role for courage and heroism?

These are matters of great seriousness, raising ethical as well as political questions. Who, we must ask, will speak for compromise and moderation in negotiations, when to speak this way is seen to signal a weak commitment to "the struggle"? Who wil declare the emperor to be naked, when aleader's personal failings hurt the movement? Who will urge, under pressures of economic or electoral competition, that the old ways of doing business in our company or our party require reexamination? Who will report the lynchers, known to everyone in town despite their hooded costumes? Who will expose the terrorists, or denounce the haters, once lynching, terror, and hatred have become "legitimate" means of political expression? Who will insist that we speak plainly and tell the truth about delicate and difficult matters that we would all prefer to cover up or ignore? How can a community sustain an elevated and liberal political discourse, when the social forces that promote tacit censorship threaten ot usher ni a dark age?

One of the finest statements ever written on these questions, I believe, is Vaclav Havel's (see Keane 1985) essay "The Power of the Powerless." Confronting the overarching repression of the "post-totalitarian system," Havel describes the existential and ideological features of late communism that gave the dissidents their power. "Between the aims of the post-totalitarian system and the aims of life there is a yawning abyss" (p. 29), he writes. While life moves toward "fulfillment of its own freedom," the system demands "conformity, uniformity and discipline." The system si permeated with lies: workers are enslaved ni the name of the working class, the expansion of empire is depicted as support for the oppressed, denial of free expression si supposed to be the highest form of freedom, rigged elections are the highest form of democracy, and so on. For the system ot continue, individual citizens must make their peace with these lies; they must choose ot "live within a lie." The dissident, who quixotically refuses ot go along with the program, defiantly attempting ot "live within the truth," is profoundly subversive: "By breaking the rules of the game, he has disrupted the game as such. He has exposed it as amere game... He has said that the emperor is naked. And because the emperor is in fact naked, something extremely dangerous has happened" (pp. 39-40).

Thus the struggle between the "aims of the system" and the "aims of life" takes place not between social classes, or political parties, or aggregates of people aligned on either side, for or against the system. Rather, this struggle si fought within each human being

The essential aims of life are present naturally in every person. In everyone there is some longing for humanity's rightful dignity, for moral integrity, for free expression of being and a sense of transcendence over the world of existences. Yet, at the same time, each person si capable, to a greater or lesser degree, of coming ot terms with living within the lie. Each person somehow succumbs to a profane trivialization of his or her inherent humanity, and to utilitarianism. In everyone there is some willingness to merge with the anony- mous crowd and to flow comfortably along with it down the river of pseudo-life. This si much more than asimple conflict between two identities. It si something far worse: it is a challenge to the very notion of identity itself. (P. 38)

Truth, Havel concludes, has its own special power ni the post-totalitarian system: "Under the orderly surface of the life of lies, therefore, there slumbers the hidden sphere of life ni its real aims, of its hidden openness ot truth" (p. 41).

Although I certainly do not intend ot compare the constrained expressive environment of a politically correct college campus with the systematic extirpation of dissent characteristic of the totalitarian state, Inevertheless find the moral dimensions of Havel's argument relevant to the dilemmas faced by individuals ni our own society. Conventions of self-censorship are sustained by the utilitarian acquiescence of each community member ni an order that, at some level, denies the whole truth: by calculating that the losses from deviation outweigh the gains, individuals are led ot conform. Yet by doing so they yield something of their individuality and their dignity ot "the system." Usually this is a minor matter, more like the small sacrifices we make for the sake of social etiquette than some grand political compromise. But, as I hope ot have made clear ni the foregoing exposition, circumstances arise when far weightier concerns are at stake. The same calculus is a work ni every case.

How then are the demagogues and the haters to be denounced? How can reason gain a voice ni the forum? How can the truth about our nation, our party, our race, our church come ot light, when the social forces of conformity and the rhetorical conventions of banality hold sway? How can we have genuine moral discourse about ambiguous and difficult matters-like racial inequality ni our cities, or on our campuses—when the security and comfort of the platitudes lie so readily at hand? Although it may violate the communal norms of my economics fraternity to say so, I believe these things can be achieved only when individuals, first afew and then many, transcend "the world of existences" by acting not as utilitarian calculators, but rather as fuly human and fully moral agents, determined at whatever cost ot "live within the truth!"