They think the paintings are rubbish. I don't think they are. The auction's in two days

And other great things I found this week

Robert Martiensen (1933 — 2007)

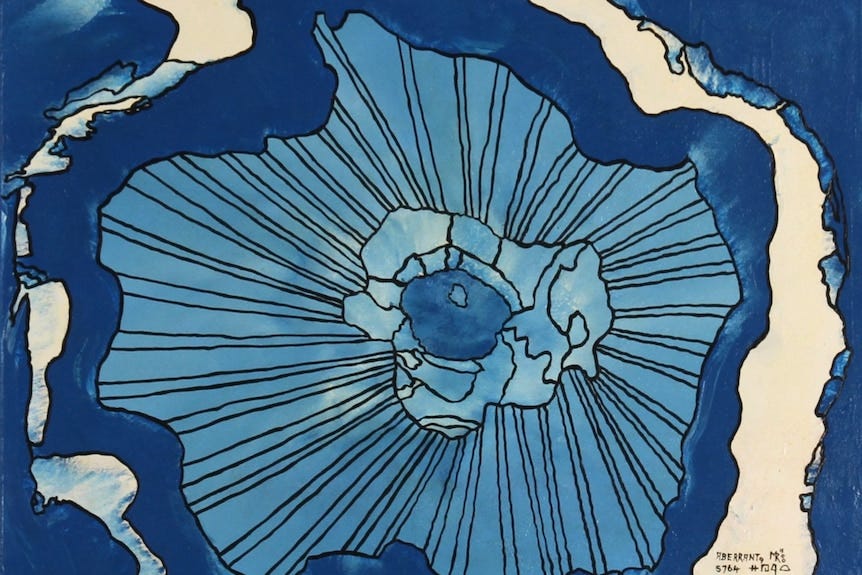

I discovered the book (cover illustrated below) browsing in Readings in Carlton. Wonderful story. Lovely paintings. I’m surprised more of a fuss isn’t being made of it. The extract below is from the ABC website and here’s a Guardian article on Martiensen.

Days after his death in 2007, the extraordinary discovery of Martiensen's artworks came across the desk of Elizabeth Arthur, a psychotherapist and art valuer who lives just across the state border, in Hamilton, Victoria.

"The secretary put through a call, which she doesn't do except in an emergency," Dr Arthur said.

Dr Arthur said the call was from an auctioneer for Elders in South Australia, a stock and land company that specialises in rural land and clearance sales.

"He said, 'I've got this estate to auction. And we've discovered a lot of paintings. When I say a lot of paintings, I mean thousands of paintings'," Dr Arthur said.

The auctioneer then told Dr Arthur that the paintings were about to be sold off, but he wasn't sure they should be.

"He said, 'The family has said they're rubbish, get rid of them. I don't think they are. The auction's in two days. Could you come over tomorrow and assess them?'" Dr Arthur said.

"So everything else was cancelled and off I went to South Australia."

What an arsehole!

The crushing bore, and a bit of family folklore

The scene from Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, illustrates his concept of the arsehole, though I guess it should be spelled in American as it’s an american word in this context. The essence of the phenomenon isn’t just the crushingly boring nature of the asshole. People often say on meeting some person with great charisma that they felt like the charismatic was making contact with them like they were the only person in the room. A crushing bore makes the transition to an asshole by bullying their way into our attention and insisting on the urgency immense significance of … the immensely insignificant. And that they’re the only person we could possibly be interested in.

Anyway, many years ago I christened the content of such communication “Pal Dog Food” after the asshole in this ad. #AussieAussieAussieOiOiOi.

“I don’t care where you go”. Great treks across the outback won’t do it. Perhaps Burke and Wills were really just looking for a better dog food. (As top dog breeders do.) Turns out they could have saved themselves the trouble. It doesn’t matter where you go! Capiche?

Of course, looking at it now, I was being unfair. He’s harmless enough and nothing on the asshole in the nine minute monologue below. NINE MINUTES. The bore of transcendental magnitude. I don’t care where you go. You’re in the dunny with him!

The three things that will empty your bladder that YOU WON’T BELIEVE!!

As I texted my kids when I saw this:

Enjoy! It’s one star from me, and three from Margaret.

Chimps are liberals and humangoes are (Burkean) conservatives

Comment from me on another substack which is worth checking out.

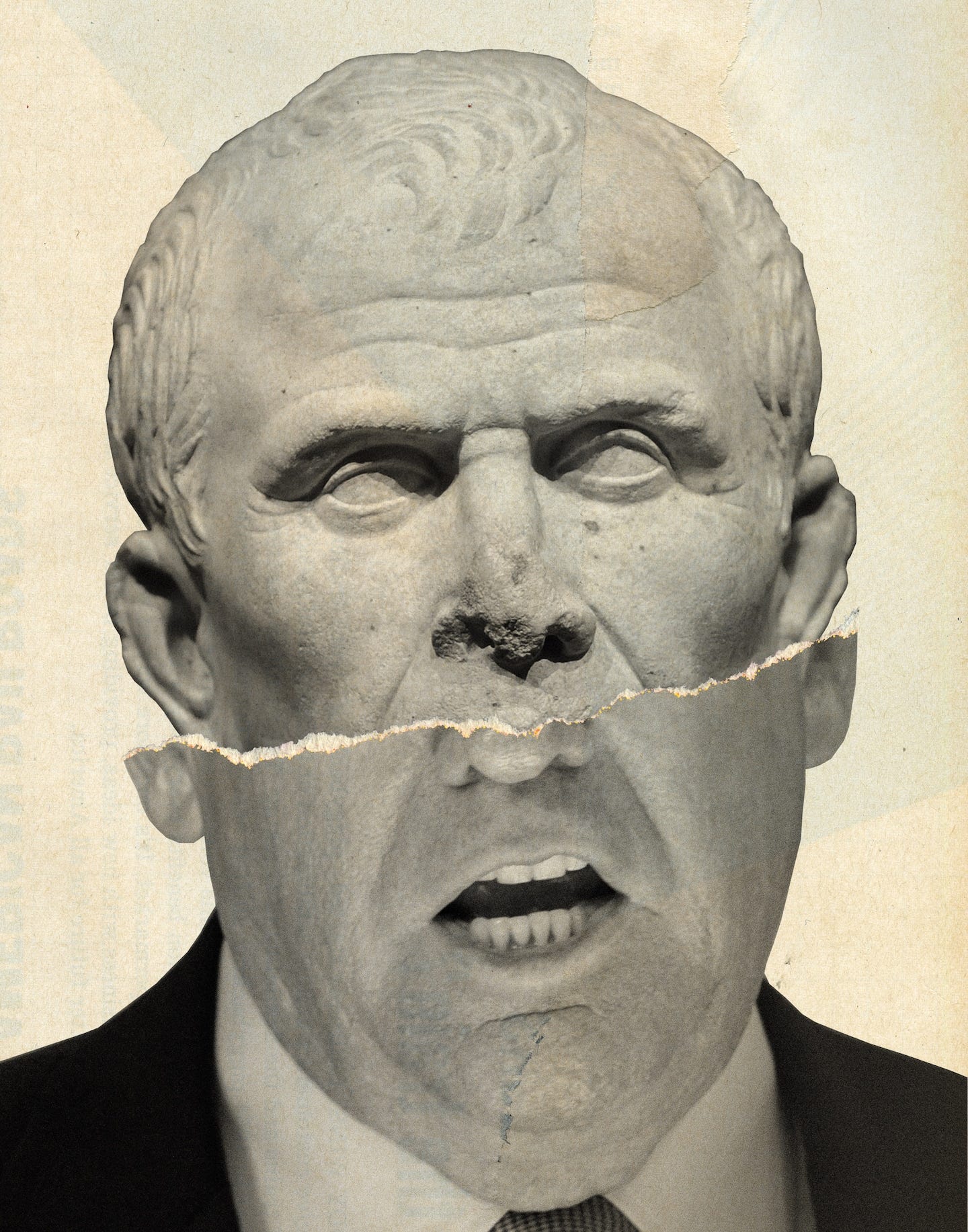

Drifting into dictatorship

Mainstream folks are no longer so optimistic about the Great Republic’s capacity to withstand the onslaught that’s coming. In the session I participated on on Democracy in London on the 15th Martin Wolf commented that “In America, they’re about to elect a fascist. It’s as simple as that”.

Now the Editor at Large for the Washington Post is singing the same song. Thanks to Andrew Denton for sending it to me. I usually give the WaPo a miss because of its strict paywall, but this article is open.

Like people on a riverboat, we have long known there is a waterfall ahead but assume we will somehow find our way to shore before we go over the edge. But now the actions required to get us to shore are looking harder and harder, if not downright impossible. … [Once he wins the Republican nomination] Trump will not only dominate his party. He will again become the central focus of everyone’s attention. … Trump enjoys some unusual advantages for a challenger, moreover. Even Ronald Reagan did not have Fox News and the speaker of the House in his pocket.

Trump will not be contained by the courts or the rule of law. On the contrary, he is going to use the trials to display his power. That’s why he wants them televised. Trump’s power comes from his following, not from the institutions of American government, and his devoted voters love him precisely because he crosses lines and ignores the old boundaries. …

And just wait until the votes start pouring in. Will the judges throw a presumptive Republican nominee in jail for contempt of court? Once it becomes clear that they will not, then the power balance within the courtroom, and in the country at large, will shift again to Trump. The likeliest outcome of the trials will be to demonstrate our judicial system’s inability to contain someone like Trump and, incidentally, to reveal its impotence as a check should he become president.

If Trump does win the election … what limits [his] powers? The most obvious answer is the institutions of justice — all of which Trump, by his very election, will have defied and revealed as impotent. A court system that could not control Trump as a private individual is not going to control him better when he is president of the United States and appointing his own attorney general and all the other top officials at the Justice Department. Think of the power of a man who gets himself elected president despite indictments, courtroom appearances and perhaps even conviction? Would he even obey a directive of the Supreme Court? Or would he instead ask how many armored divisions the chief justice has? …

Trump will not be the only person seeking revenge. His administration will be filled with people with enemies’ lists of their own, a determined cadre of “vetted” officials who will see it as their sole, presidentially authorized mission to “root out” those in the government who cannot be trusted. Many will simply be fired, but others will be subject to career-destroying investigations. The Trump administration will be filled with people who will not need explicit instruction from Trump, any more than Hitler’s local gauleiters needed instruction. In such circumstances, people “work toward the Führer,” which is to say, they anticipate his desires and seek favor through acts they think will make him happy, thereby enhancing their own influence and power in the process.

Good interview

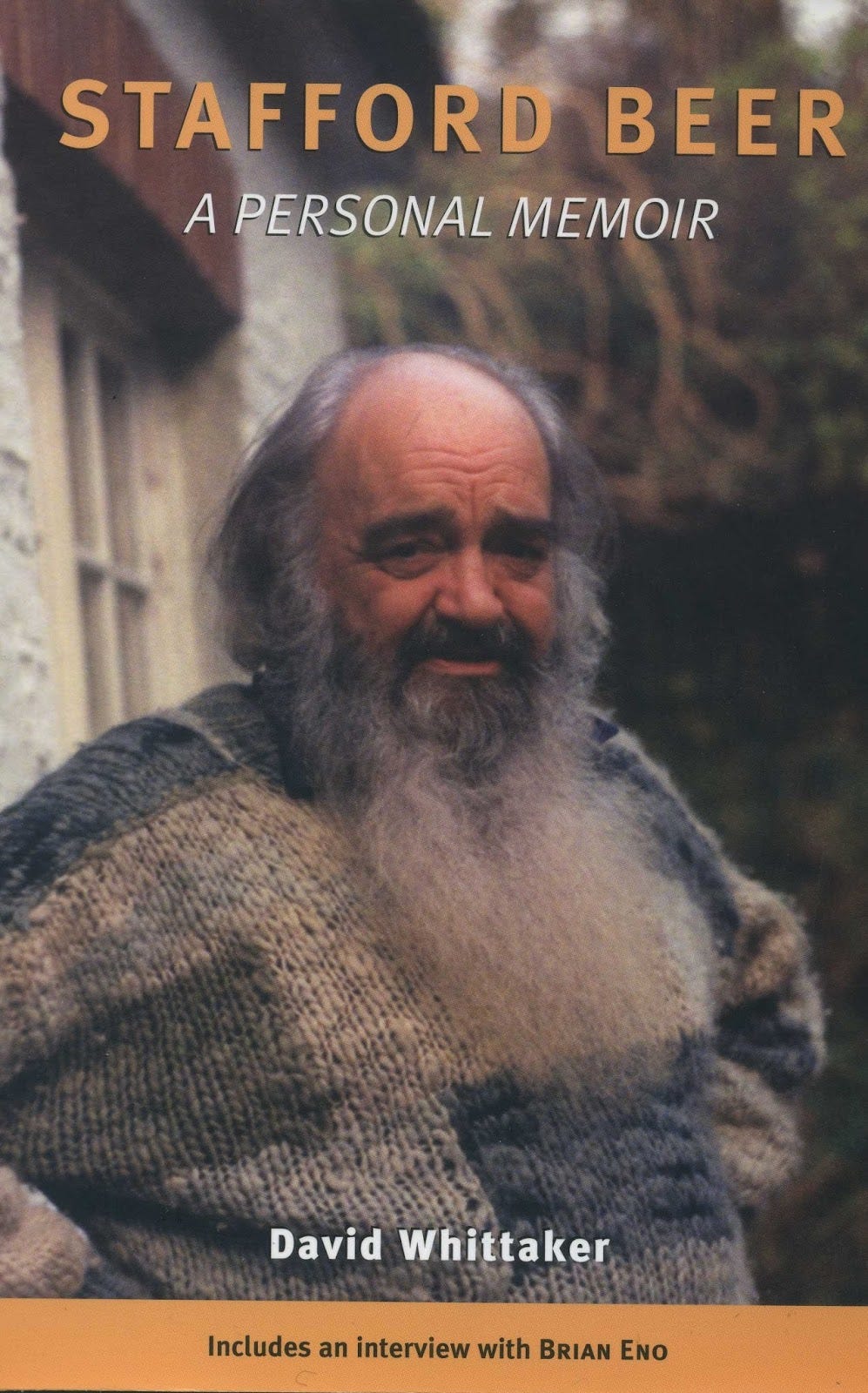

Stafford Beer

Yet another person I should have known about but didn’t. The author despairs that people don’t listen, don’t work out who’s got something to say, and who’s pretending. Well no they don’t. And so it goes. In any event, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation takes itself a little more seriously than our ABC and allows you to listen to its flagship Lecture series all the way back to 1961, so you can listen to Stafford Beer delivering the lectures “Designing Freedom” from 1973. As you can hear if you listen to them, Beer’s concerns back then were, let’s just say, prophetic.

Anyway, here’s Kevin Munger on Beer from that old and venerated standard of the blogosphere Crooked Timber.

As someone who reads and writes for a living, in the hope that these actions will change the world for the better, I occasionally experience an odd emotion when I read something that’s decades old that condenses some thought I’ve been grasping towards. Part of this emotion is simple scientific envy, that someone beat me to it; part of it is pride, of wanting to share the idea with my peers and enjoy some reflection of its glory. Beneath these feelings, though, is despair – despair that someone else, someone more famous and smarter and older than me already wrote this idea down and yet it didn’t matter.

Stafford Beer’s writing, career trajectory and just overall weltanschauung had this effect on me. The man:

Was born into aristocratic British society and thus had establishment connections and legitimacy.

Correctly diagnosed a variety of fundamental incompatibilities between our inherited institutions, the contemporary scale of our societies and rapid change in communication technology.

Developed an impressive reputation, giving over 500 invited lectures and frequent media appearances, as well as a flourishing and remunerative career as a business consultant.

Cashed out this reputation and connections in a series of increasingly transgressive attacks on what he saw as a complacent and unscientific establishment. (His inaugural address, upon being elected president of the Operational Research Society, is particularly spicy.)

Actually had the chance to implement his radical ideas at the level of a medium-sized country, and demonstrate at least preliminary evidence for their effectiveness.

I’m impressed

David Marr on the frontier

Larissa Behrendt’s review of David Marr’s book. With my mother having Queensland squattocracy ancestry (she was a cousin of Banjo Patterson), I expect there are similar skeletons in my cupboard.

Marr paints his characters meticulously. Richard Jones, an astute businessman and Christian evangelical, amassed large tracts of land on which to graze his sheep. His accumulation of wealth rested on clearing the land of its original occupants. Aboriginal people were slaughtered with no protection from the colony, a process that Jones was able to keep at arm’s length by giving others the bloody work of “dispersal” or “reprisal.”

Like many other Christians, Jones failed to see the humanity in Aboriginal people and so his charity couldn’t extend to them. At the height of his landholding, he would have more than 600,000 acres. His is the story of the “entrepreneur gentleman,” a type whose wealth was often portrayed as coming from acumen and savvy but who, in truth, took land with brute force (even if not by his own hand) and then used his wealth, power and position (in parliament, commerce and banking) to ensure that laws favoured his interests and didn’t protect those who had been removed.

Marr’s profile of Edmund B. Uhr reveals a man with his own aspirations for large landholdings and status, whose appointment as magistrate gave him the power to condone violence or turn a blind eye to it, often for his own convenience. Marr then tracks the exploits of two of Uhr’s sons, brothers Reg and D’Arcy, as they move through Queensland and into the Gulf country as officers of the Native Police. They helped clear Aboriginal populations from traditional lands, suppressing resistance while avoiding having literal blood on their hands. …

Killing for Country also sets what was occurring in Australia in the context of colonisation processes around the globe, a facet that is too often overlooked. He notes, for instance, that the American war of independence had been sparked by a refusal to grant more land to the colonisers, and the British weren’t keen to make that mistake again. When the line around the Sydney colony’s nineteen counties was breached, there was little appetite to rein anyone in. …

The violence perpetrated against our ancestors, often coupled with sexual violence against Aboriginal women, was sparked not just by the taking of land but by Aboriginal communities standing up against settler abuse of women and children. The treatment of Aboriginal women in the process of colonisation still feels under-researched; it is not adequately captured in the archives or written colonial records.

Henry Ergas on Sydney Theatre Company

Pity poor Chekhov. It is hard to think of anything that would have appalled him more than actors ending the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of The Seagull by donning keffiyehs in protest … It is true that the stunt, which seamlessly combined the ludicrous with the repulsive, is merely agitprop’s latest triumph over art – a triumph encouraged by cultural policies that increasingly allocate public funding … on the basis of politics rather than merit. …

There may be an element of justice in the STC reaping what it sowed; but it cannot erase the injustice to Chekhov. In effect, of all the great Russian authors of the 19th century, it was Chekhov who most firmly opposed the confusion between art and propaganda. Writing at a time when incessant political agitation and revolutionary fanaticism had permeated Russian life, he adamantly rejected the view that writers should tell the public what to think, much less dispense public lessons in morality.

His reluctance to assume that role was strengthened by his disdain for the intelligentsia – a term coined in Russia in 1860 – and notably for its “progressive” mainstays. …

Rather than being bullied into toeing the “progressive” line, Chekhov described creators’ duties as two-fold. The first was intellectual humility: “it is simply dishonest”, he wrote, “to pronounce on issues one scarcely understands”.

The second was to refrain from histrionics, instead setting out, “like a reporter”, exactly what one saw, and “allowing the jury, ie, the public, to do the evaluating”. Accused by the radical poet Aleksey Pleshcheyev of being insufficiently “tendentious” (a characteristic the revolutionaries regarded as a virtue), he replied that “far from not protesting, I protest constantly against lies – is that not a tendency?”.

The supreme value for Chekhov was consequently truth, which he wrote about in terms of “pravda”, a Russian word connoting both justice (“rightness” in a moral sense) and truth (“rightness” as factual correctness). And a truth to which he was strongly committed was European civilisation’s contribution to human progress.

Both Dostoevsky and Tolstoy considered Western Europe, and notably England, the very image of hell. But Chekhov’s letters eulogise its great assets: respect for others, political moderation, freedom under law.

Repelled by the unchecked cruelty of “Asiaticness”, he argued that “the Englishman exploits Hindus, but he gives them roads, aqueducts, museums, Christianity”: the other exploiters, including the Russian empire, only gave back “brutal officialdom and blind obedience”, condemning the people they subjugated to perpetual barbarism. …

Born in an area of southern Russia where Jews were allowed to settle, and being himself – as the grandson of serfs – an outsider, he formed lifelong friendships with Jews that would have been unthinkable to writers from Russia’s north. His early work featured some typical anti-Semitic tropes; he abandoned them once the pogroms got under way.

Already apparent in his first major play, Ivanov, the condemnation of anti-Semitism became a crucial part of his outlook during the Dreyfus Affair, which spurred him –for the first and only time – into political activity. Indeed, when his greatest supporter and close friend, publishing magnate and theatrical empresario Aleksei Sergeevich Suvorin, published an anti-Semitic attack on Dreyfus, he terminated their relationship, never to be resumed.

Kilkenomics 2024: Get your Golden Ticket. Get it NOW!

People travel from all round the world to attend Kilkenomics. Seriously. I met a couple from the NT. What else were they doing in Ireland I asked them. “Oh, not much. We came for Kilkenomics.” But since the shows now all sell out, you need to get your skates on. Book now! Festivities start the day after we find out whether the US Presidency has fallen to a fascist.

I didn’t read Walter Isaacson’s Elon biography so you don’t have to either

I avoided even much of the reviews of Walter Isaacson’s herogram of Elon because it seemed clear it was written to a formula. Anyway, happening on this review, I agree with it wholeheartedly (which is ridiculous because I’ve read almost nothing). Anyway, we all have to have our heuristics and I was following mine here. (You’re welcome).

And it starts with a scene with Max Levchin who took over from me as Chair of Kaggle.

There’s a scene in Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Elon Musk that unintentionally captures the essence of the book:

[Max] Levchin was at a friend’s bachelor pad hanging out with Musk. Some people were playing a high-stakes game of Texas Hold ‘Em. Although Musk was not a card player, he pulled up to the table. “There were all these nerds and sharpsters who were good at memorizing cards and calculating odds,” Levchin says. “Elon just proceeded to go all in on every hand and lose. Then he would buy more chips and double down. Eventually, after losing many hands, he went all in and won. Then he said “Right, fine, I’m done.” It would be a theme in his life: avoid taking chips off the table; keep risking them.

That would turn out to be a good strategy. (page 86)

There are a couple ways you can read this scene. One is that Musk is an aggressive risk-taker who defies convention, blazes his own path, and routinely proves his doubters wrong.

The other is that Elon Musk sucks at poker. But he has access to so much capital that he can keep rebuying until he scores a win.

Isaacson, our narrator, doesn’t grasp the difference. He doesn’t understand poker well enough to recognize Musk as the grandstanding sucker at the table. So he portrays Musk’s complete lack of impulse control as a brilliant, identity-defining strategic ploy. (If you go all-in and lose six times, then go all-in a seventh time and win, then you’re still down five buy-ins.)

Isaacson clearly knew what sort of book he was setting out to write. He is a star biographer, one who specializes in penning classic, “Great Man” stories of history-defining figures. He has chronicled the lives of Ben Franklin, Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, and others.

The motivating premise of these “Great Man” stories is that history is made by unrestrained, risk-taking geniuses. Isaacson strives to give his readers insights into the complex inner lives of these singular, special individuals: what drives them, where they come from, what they have figured out that positioned them to make such a dent in the universe?

The “Great Man” version of history is always limiting (and, as Brian Merchant argues, it should probably be retired at this point), but it is particularly ill-suited to a character like Musk. Isaacson wants his reader to appreciate Musk’s accomplishments and also ponder his personal “demons.” But there is a deeper puzzle that Isaacson constantly avoids “Is Elon Musk really some world-bending genius, or has he just benefitted from the world’s biggest case of survivor bias?”

That’s not a question that Isaacson is comfortable assessing.

Quite.

I didn’t read much further on, but had the review recommended, so if it takes your fancy read on. And I might just say that I’m not sure that it’s survivor bias. How could I or anyone else be. Until, and perhaps even after we get the biographer the author longs for “with a sharper eye, a more discerning ear and a more tenacious voice.”

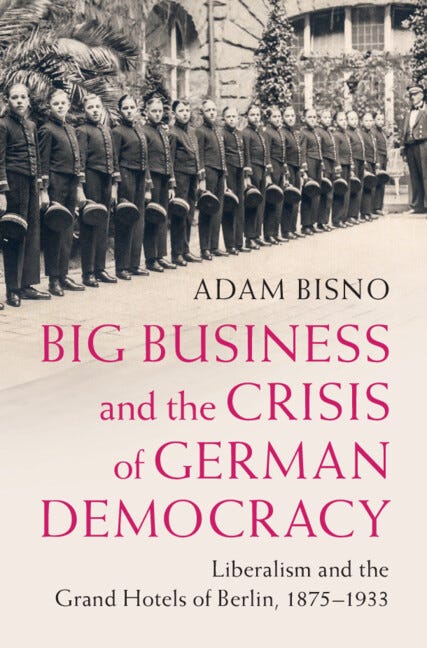

You’re Jewish and Hitler sets up Nazi Headquarters in your hotel: What do you do?

In February 1931, two years before he became chancellor, Adolf Hitler checked in to Berlin’s Hotel Kaiserhof and made it his headquarters in the capital. The building soon swarmed with Nazis, who transformed the clientele overnight. Jewish custom evaporated. Business suffered. A year and a half later, with revenues in freefall, the hotel’s parent company needed to act. Its board, majority Jewish, took up the issue at a meeting on September 15, 1932. The question facing them: What are we going to do about Hitler? …

The chairman, William Meinhardt … weighed in first: “As a hotel company, we must remain neutral on matters of religion and politics. Our houses must remain open to all.” Another board member, Wilhelm Kleemann, managing director of Dresdner Bank and head of the Jewish Community of Berlin, now protested: “I know for certain that Jewish guests no longer stay at the Kaiserhof and no longer visit the restaurant, either.”

But Meinhardt had decided, and enough board members agreed: Hitler could stay. …

In all their fragility, grand hotels were liberal institutions par excellence. They depended on the free movement of goods and people as well as the self-regulatory capacity of guests and staff. And yet, at the heart of the thing lay a dark irony. The grand hotel as a liberal institution, much like the era’s liberal constitutions, disenfranchised the majority for the benefit and prestige of the minority.

Grand hotels in Berlin had never been reliably profitable because they were too expensive to run. From 1875 to 1914, staff outnumbered guests, at some properties by a ratio of 2:1. … From 1919 to 1923, Berlin’s hoteliers were ambivalent about Germany’s new republic. But after the hyperinflation of 1923, when the German economy collapsed, that ambivalence turned to antipathy. They never forgave the republic and refused to acknowledge publicly its successes after 1923. Instead, the hoteliers continued to heap scorn on the Weimar Republic, using it as the scapegoat for their own failures of judgment and accounting. The scapegoating intensified at the advent of the next crisis, the Great Depression. The republic all but written off, Hitler looked like the future – a future that might be better for business. …

Meinhardt and the others, [with] full knowledge … had facilitated everything, deciding to keep the Kaiserhof available to Hitler all the way down to his assumption of power on January 30, 1933. What’s more still, this story of the failure of liberal hoteliers is in microcosm the story of the failure of German liberalism, a catastrophe that expanded from the Kaiserhof to the chancellery to the rest of Europe and then the world. The decisions of liberal businessmen mattered. Faced with their nemesis in flesh and blood, they turned to liberal argumentation for support. It didn’t work.

Their dilemma has become a perennial one. What should a corporate board of directors do when the interests of democracy and the interests of their business don’t seem to align? Favor the latter was the answer in 1932. Is it still?

Great column by Hugh White on Kissinger

I’ve found, a little to my surprise, that the closer one examines Kissinger’s record in office during those years, the better he looks. Indeed, one can argue that he was, in his strange partnership with Richard Nixon, the most effective and important American statesman since the remarkable generation of Wise Men that launched America into the post-war world. …

Kissinger never shared the breezy confidence in American preponderance that has been so characteristic of his adopted country. He focused instead on the limits of America’s power, and the need accordingly to set realistic aims and pursue them economically. His perspective was closer to that of traditional European great powers, all too aware of the other great powers that surround and challenge them. …

It has often been remarked that Kissinger’s approach to international affairs was deeply rooted in European rather than American ideas of both the purposes and methods of statecraft. But it is worth looking more deeply at what that meant and how it worked when he took high office at such a demanding time.

The best place to start is with A World Restored, the first of two books he published in 1957 and still well worth reading today, especially the first and last chapters. In it, Kissinger used the 1814-1815 Congress of Vienna and the role of Klemens von Metternich as case studies in statecraft, and in particular to argue that the true objective of statecraft should be to establish or preserve order, rather than to seek improvement – to keep things stable, rather than make them better.

This did not make him a crude Morgenthau realist, because he was concerned with order, rather than with power for its own sake, but it did set him against the Wilsonian tendency to see America committed to making the world a better place. Moreover, his thinking about the problems of order in the post-war world were framed by a European rather than American attitude to power. It was this perspective that made Kissinger so suited to managing the crisis of American power that confronted him in the years after 1969. To a remarkable degree, the times suited him. …

Alas in retirement, despite writing a lot about it, he had little useful to say about this challenge. There is, though, no doubt that America today needs someone of Kissinger’s stamp to conceive and create a sustainable relationship with this powerful rival. No such person seems to be available. With US policy currently in the hands of China hawks who are eager to launch a new Cold War but have no idea how it could be won or why it must be fought, the lack of sober, realistic statesmanship is all too obvious. …

It is perhaps a little trite, but also I think probably true, to attribute some of Kissinger’s talents and his success to his experiences – as a Jewish child in Nazi Germany, as a soldier during the Second World War and its aftermath in Europe, and as an engaged analyst of the early Cold War. He understood what a really serious, life-and-death strategic contest was like. His successors are less well prepared. They do not even understand that this is what the new Cold War with China will be like.

China laments the passing of a great power realist

In the Lowy Interpreter, Ye Xue and Sophie Wushang Yi write of sadness at Kissinger’s death as one who sought to avoid great power conflict.

While Western perceptions of Kissinger remain polarised, the perspective in China, as predominantly portrayed in the media and encapsulated by President Xi Jinping’s tribute, stands as notably favourable. “Henry Kissinger was a world-renowned strategist and also an old friend and good friend of the Chinese people,” Xi declared.

The title “old friend of the Chinese people” is considered the highest courtesy for the government of China to bestow on foreign individuals, and Chinese media has endeavoured to make the public understand that Kissinger was deserving of the title because of his understanding of and appreciation for Chinese history and culture. There have been frequent references to Kissinger’s 2011 treatise On China.

From the viewpoint in China, Kissinger’s legacy is framed by two crucial historical periods. The first, during the Cold War, saw Kissinger champion the normalisation of China-US relations, establishing a policy framework that endured for four decades. Central to this approach was humility in the ideological domain, recognising the authority of the Chinese Communist Party, and providing sufficient assurances on the Taiwan issue. Embracing this “live-and-let-live” attitude, the two countries maintained a generally stable relationship for decades

The second period, amid contemporary great power competition, witnessed Kissinger advocating for peaceful coexistence between China and the United States. His concept of “co-evolution” emphasised the importance of avoiding misunderstandings and suspicions, and managing the China-US relationship from the perspective of international order and the well-being of human society.

Acknowledged as a realist in diplomacy in support of US interests, Kissinger’s strategic beliefs are portrayed as rooted in his experience during the Second World War, fostering an understanding of the necessity of a stable international order, maintained through coordination among major powers. For example, what has been frequently mentioned is that Kissinger wrote:

China does not see itself as a rising, but a returning power. It does not view the prospect of a strong China exercising influence in economic, cultural, political, and military affairs as an unnatural challenge to the world order – but rather as a return to a normal state of affairs.

Snapshot of our labour market

Australia’s premier labour market economist puts out a weekly newsletter. And he’s just published a snapshot on past research on the Australian labour market. As he writes:

So much of that research still has lessons for us today, or is important for understanding how we got to where we are now in studying labour markets, yet doesn’t seem to be widely known. I’m starting in this Snapshot with articles published between the mid-1970s and mid-1990s.

He starts with Bob Gregory.

Bob Gregory (1991), ‘Jobs and gender: A lego approach to the Australian labour market’ , Economic Record, 67, Supplement, 20-40. The only place to start a review of research on the Australian labour market in the 1980s and 1990s is with Bob Gregory. This article asks the question: ‘Why, despite strong employment growth during the 1980s, did unemployment remain high at the end of the decade?’ The answer, it turns out, is straightforward, yet at the same time a major departure from how dynamics in the Australian labour market had been thought to operate.

New job creation in the 1980s attracted extra workers, not by pulling people out of unemployment, but by bringing extra workers into the labour force. A slightly more detailed account is that: (i) During the 1980s, job growth was biased towards part-time jobs in industries where females accounted for a large share of employment; and (ii) Females taking up those jobs came primarily from outside the labour force, rather than from unemployment.

The article presents us with several lessons for studying labour markets: • The importance of looking beneath the aggregate numbers. In this case, that means dividing the labour market between males and females, and employment between full-time and part-time. Of course, it’s not just a matter of looking at disaggregated measures. It’s also about choosing a level of disaggregation that gets to the essence of the question being considered, and at the same time is as simple as possible.

• The need to understand unemployment, not just in terms of workers shifting between employment and unemployment, but also taking into account movement into and out of the labour force.

• Every episode needs to be seen anew. Applying the unemployment/ employment relationship from the 1930s predicts a much larger decrease in the rate of unemployment in the 1980s than actually occurred.

Understanding the 1980s required recognising that this was a new episode, where movements to and from the labour force had become a much more important aspect of cyclical adjustment than in the 1930s.

My list of other essential reading of articles by Bob Gregory includes: • Cross-country analysis (with Anne Daly and V. Ho) of the gender pay gap, using the 1969/72 Equal pay case decisions in Australia as a ‘natural experiment’, with the objective to identify the impact of discrimination and the scope for policy to affect wage outcomes (for example, Gregory et al., 1989).

• Analysis of the determinants of wage growth in Australia, proceeding from the breakdown of the Phillips curve in the 1970s and 1980s, to present an insider-outsider theory of wage setting and alternative empirical approaches to testing the impact of demand on wage growth (Gregory, 1986).

• Work (with Boyd Hunter) on the differential impact of the macroeconomy on labour market outcomes between neighbourhoods (Census Collector Districts) in Australia from 1976 to 1991 (Gregory and Hunter, 1995; and see also Hunter, 1995).

Aristeia

Triffic post with a triffic video to watch at the end — which I’ve posted above. I’d certainly heard the performance, but not watched it.

1988 was, for George Michael, “what pop critics call an ‘imperial’ year.” In that year he “reigned over the charts and, essentially, could do no wrong.” It was the year of Faith, his debut solo album, which spent twelve weeks at number one, and produced four number one singles, each of which, if you were alive at the time, you still remember well enough to hum today. Chris Molanphy, on his Hit Parade podcast, explains “imperial period” with the paradigm case, the most imperial of imperial periods by any pop musician: Elton John, 1970-1975. In that short stretch of time Elton John recorded and released seven consecutive number one albums, and it all peaked in 1975, when he sent three singles and three separate albums to the top of the charts. …

For Elton John, the 1975 peak was also the end. Immediately, song quality and song quantity declined; and audiences turned against him when, in a 1976 interview, he outed himself as bisexual. He became, in Molanphy’s words a “modest, second-tier pop act.” This fall is part of the paradigm. When Elvis died in 1977, “all alone,” as Gillian Welch sang, “in a long decline,” John Lennon quipped that “Elvis really died the day he joined the army.” …

The aristeia is “the main compositional unit of battle narrative” in Homer’s Iliad.1 An aristeia displays “the excellence or prowess of a Homeric warrior when he is on a victorious rampage, irresistibly sweeping all before him, killing whomever of the enemy he can catch or whoever stands against him.” In the oral tradition from which the Iliad derives, the aristeia was a major element: “the audience would have been able to appreciate both the fulfillment of the norm and artful, meaningful variations on it.” If during a hero’s aristeia he displays god-like powers, it is because his powers have in fact been enhanced by the gods. When the Greek leader Diomedes got his aristeia, in Book 5 of the Iliad, Athena “gave to Diomedes / courage and energy, so he would win / great glory and shine bright among the Greeks.”2 “She spurred him to the center of the fray.” Just as “no dam, no fence around the verdant vineyards / can hold its place against the sudden onslaught / during a downpour sent by Zeus,” “So Diomedes routed the dense ranks / of Trojans, forced them into retreat.” Diomedes is shot by a Trojan archer, but a comrade pulls out the arrow, and Athena “made his feet and hands and limbs feel nimble, / and stood beside him, speaking words on wings,” urging him back into battle: “In your chest I put / the dauntless courage that your father had.” In battle, Athena “steered [Diomedes’ spear] beneath [Pandarus’s] eye and through his nose, / smashing his white teeth,” and later, emboldened, Diomedes does battle with, and gets the better even of Ares, god of war. Eventually a hero’s aristeia ends, but woe betide he whose aristeia ends mid-fray, divine favor removed and the shield-wall opening a flood of charging Trojans.

Calling aristeia a “compositional unit” is calling it a mere convention attached to a particular genre. That’s not right at all. Aristeia a real phase in real life-histories. In a culture where glory was available in battle, the portraits of aristeia were bloody, but prowess and excellence are available in many other domains, and therefore so is aristeia. Elton John’s imperial period was his aristeia: greatness was effortless and everything he touched turned to gold. Aristeia, in anticipation, is the brass ring you’re reaching for, and the vision you will manifest, as you stumble through the twentieth mile, nail another rejection letter to the wall, and wipe the latest thrown-tomato from your face. And then afterward, looking back, it’s apt to be the cause of nostalgia or of depression.

Inspiration porn: From a secular saint

And food for thought

Thanks to my friend Muneeb’s tweet above I came upon this story. But not before tweeting back:

“Great institutions, like great buildings, are always built around some fusion of practicality and noble purpose

Modernity laid siege to this idea, first announcing itself clearly in the triumph of modernist architecture before munching its way through all our institutions.”

Pakistan's shambolic public health system suffers from corruption, mismanagement and lack of resources. But one public sector hospital in Karachi provides free specialised healthcare to millions, led by a man whose dream was inspired by the UK's National Health Service.

Dr Adib Rizvi's most distinguishing feature is not just his grey hair. You can spot him in a crowd of people in a cramped hospital corridor by the respect he commands among patients and staff.

It doesn't only come from being the founder and the head of one of Pakistan's largest public health organisations.

Quite the opposite, for a man who's spearheaded a life-long mission of providing "free public health care with dignity," Dr Rizvi is unassuming as he walks around the hospital wards checking on his patients.

Many of them he knows by name. They include children as well as the elderly, Muslims as well as non-Muslims.

The rapport he enjoys with them is striking. He's seen as a friend, someone they trust, someone who's not after whatever little money they may or may not have.

PS: I also like the Heidegger quote (not!). Heidegger going the full, peak Heidegger. Being enters its full beingness <insert nonsense here> #HaveYouEverThoughtWhatTheNazisCouldDoForYou.

Outspiration porn

Great podcast

The iTunes link didn’t work, so just click on the mosaic. The subject? Justinian and Theodora.

J.S. Mill on thinking dialogically

My own consciousness and experience ultimately led me to appreciate quite as highly as he did, the value of an early practical familiarity with the school logic. I know of nothing, in my education, to which I think myself more indebted for whatever capacity of thinking I have attained. The first intellectual operation in which I arrived at any proficiency, was dissecting a bad argument, and finding in what part the fallacy lay: and though whatever capacity of this sort I attained, was due to the fact that it was an intellectual exercise in which I was most perseveringly drilled by my father, yet it is also true that the school logic, and the mental habits acquired in studying it, were among the principal instruments of this drilling. I am persuaded that nothing, in modern education, tends so much, when properly used, to form exact thinkers, who attach a precise meaning to words and propositions, and are not imposed on by vague, loose, or ambiguous terms. The boasted influence of mathematical studies is nothing to it; for in mathematical processes, none of the real difficulties of correct ratiocination occur. It is also a study peculiarly adapted to an early stage in the education of philosophical students, since it does not presuppose the slow process of acquiring, by experience and reflection, valuable thoughts of their own. They may become capable of disentangling the intricacies of confused and self-contradictory thought, before their own thinking faculties are much advanced; a power which, for want of some such discipline, many otherwise able men altogether lack; and when they have to answer opponents, only endeavour, by such arguments as they can command, to support the opposite conclusion, scarcely even attempting to confute the reasonings of their antagonists; and therefore, at the utmost, leaving the question, as far as it depends on argument, a balanced one.

A particularly Australian problem

Wonderful video sent by a good friend

Matthew Crawford on embodied cognition

I remember reading this thrilling section of Crawford’s excellent book “The world beyond your head: How to Flourish in an Age of Distraction”.

RIDING MOTORCYCLES: GYROSCOPIC MAN

We remain capable of learning new skills throughout life. Evolution has endowed us not with a fixed design and scripted behaviors, adapted to cope with a particular environment (securing food and mates in the Pleistocene savannahs, as the evolutionary psychologists keep insisting), but rather with highly plastic neural resources and “an ongoing regime of monitoring and recalibration,” as Clark says. When we begin to learn a new skill, new equipment often mediates between our bodies and the world, and the loop of perception through action may take a detour through physical phenomena that are quite alien to the natural human body. In that case, we find ourselves returned to the condition of being like a toddler, figuring out how to maneuver ourselves through the world.

The steering dynamics of a motorcycle are a subtle and astonishing thing. At higher speeds, to make a motorcycle initiate a turn to the left, you apply pressure as though you were trying to turn the handlebars to the right. Motorcyclists call this counter-steering, and it is indeed counterintuitive. Turning the handlebars briefly to the right makes the bike lean to the left because of gyroscopic precession, and it is the leaning that accomplishes the turning. (The reader may recall a classroom demonstration of gyroscopic precession involving a spinning bicycle wheel that one holds by its axle, while seated on a chair that is free to swivel. Tilting the axle—that is, trying to rotate it on a horizontal axis perpendicular to the axle itself—is hard to do, and makes the chair you are sitting in swivel on a vertical axis. It is a very weird experience; there seem to be demonic forces at work.)

In cornering a motorcycle there is a series of motions and exertions that get installed in muscle memory through practice, and these are integrated with the visual cues of cornering. Once the integration is fairly secure, it is the visual cues that the motorcyclist attends to, not the muscular exertions. The higher the speed, the more intensely they are attended to; the level of concentration involved in motorcycle road racing is truly impressive, as will be appreciated by anyone who has seen a picture of a rider at full lean through a corner. You will see his inside knee, sometimes even inside elbow, scraping the ground (racing leathers have plastic pucks on the knees so they don’t get torn up). The next time you see such a photo, look for the rider’s eyes. If they are visible through the helmet’s visor, you will see them directed nearly perpendicular to the bike’s direction of travel, as the rider looks all the way through the corner.

This brings up another uncanny fact about motorcycle steering: the bike goes wherever your gaze is focused. Most important, if your eyes lock on some hazard in the road, you will surely hit it. This is not a superstitious motorcyclist’s version of Murphy’s Law; it is a reliable fact, and it reveals something deep about the “intentionality” of our prereflective sensorimotor negotiation of the world. Inhabiting the kind of bodies that we do, our gaze and our locomotion are connected in ways that work for us, and we don’t have to think about it. But this accomplished integration becomes a liability when riding a motorcycle, and must be deliberately short-circuited. You have to learn to unlock your eyes as quickly as possible from every hazard, and instead look where you want to go.

This visual demand is absolutely counterintuitive. When walking, we move away from a hazard (for example a snarling dog) while keeping it in view. Our action programs, visual system, and “affect” (immediate, visceral judgments of good or bad such as happens when we see a spider) are integrated in a way that is adaptive for us, and have achieved a certain automaticity. But when the relation of your body to the world is mediated by a machine, one that requires a very different set of muscle responses to achieve the desired avoidance, then you aren’t well adapted until you have reintegrated muscle response, visual system, and affect into a very different collection of automated responses. At the heart of this learning process for the motorcyclist is a phenomenon utterly unknown to the natural human body, namely gyroscopic precession.

Gibson’s work sheds light on all this. He suggested that the concept of an “ecological niche” is necessary to properly understand perception. A niche is not quite the same as a habitat. A niche “refers more to how an animal lives than to where it lives.” It is not simply the physical surroundings, but the aspects of those surroundings that are meaningful for an animal given its way of life. When you live on two wheels, gyroscopic precession is as important a feature of your ecological niche as gravity.

Gibson’s most interesting and controversial point is that what we perceive, in everyday life, is not pure objects of the sort a disinterested observer would perceive, but rather “affordances.” The affordances of the environment are “what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill.” Affordances elicit and guide action; Gibson suggests they also organize perception. Things in our environment show up in the vivid colors of good (for a motorcyclist: a median strip with a curb that is low enough that it could serve as an escape route if things get hairy in front of you) and bad (the oily patches that are usually present in the center of a lane at an intersection, where cars drip fluids while idling). As Alva Noë puts it, “When we perceive, we perceive in an idiom of possibilities for movement.”

Our perception of these possibilities depends not only on the environmental situation, but also on a person’s skill set. A martial artist faced with a belligerent man at a bar sees the way the man is standing, and his distance, as affording certain strikes and foreclosing others, should it become necessary. Because of long practice and habituation, when he looks at the man’s stance, this is what he sees. He may also perceive the furniture nearby, and the objects lying within reach on the bar, in terms of their affordances for combat. He sees things that people like you and me don’t. That’s why we shouldn’t mess with him.

Affordances lie in the fit between an actor and his or her environment. When that relationship is mediated by a prosthetic, such as a motorcycle, it changes the field of objects that we perceive and how we perceive them. Gibson considered only the natural human body when he investigated the ways movement through our environment influences our perception. But his idea of affordances provides a useful foundation for thinking about culture and technology—that is, for thinking about the distinctly human ecological niches that we create for ourselves. This becomes important for my concept of the situated self, and we will develop it further in the chapter “Encountering Things with Other People.” But for now let us stay focused on motorcycling and try to explicate this one instance of a specialized human ecological niche in fuller detail.

In addition to gyroscopic precession, a further “unnatural” challenge in motorcycling is the categorically different rate at which you are moving toward the things in your visual field, compared with our usual bipedal locomotion. This makes it imperative to keep one’s eyes fluid. One has a certain amount of time, typical of the particular environment one inhabits, to judge a hazard and respond accordingly. A ship’s captain on the open sea has a lot more time to avoid another ship than an alligator wrestler has to read the signs of his opponent’s impending move. At high speeds these “judgments” (if that is the right word) must be very fast. They cannot be the result of a conscious inferential process (just as they are not when we are running to catch a fly ball), because inference is a slow and cognitively costly activity. The subconscious integration of sensorimotor data that one is performing while riding a motorcycle at high speeds requires a great deal of concentration, but not a lot of articulate thinking.

Those data are inextricably bound up with a host of mechanical contingencies. A motorcyclist feels the road through his tires, and racers are very particular about the air pressure, the cross-sectional shape, and the particular rubber compound used. A constant curvature in the tire’s cross section will make the bike feel linear in its response to the rider’s leanings. A flatter cross section or “profile” will produce a larger contact patch while the motorcyclist is riding upright in a straight line (thus increasing braking power at the end of a straightaway, which is important because then the rider can initiate braking later), while a peakier profile will have a larger contact patch while the cyclist is leaned over in the turns. Choice of tire profiles therefore depends somewhat on the track and a team’s race strategy. Different rubber compounds break loose with more or less abruptness, which influences the rate at which the rider can apply throttle coming out of a corner (in this situation traction, not horsepower, is the limiting factor; in general, traction is “conserved” and must be judiciously allocated among lean angle, acceleration, and braking). Some tires communicate better than others. The rider also feels the road through the suspension, which on race bikes is separately adjustable for compression and rebound damping, as well as effective spring rate. Some racers are particular even about the steering head bearings, claiming they can feel the difference between tapered roller bearings and ball bearings. Needless to say, a racer does not attend to any of these elements while leaned over at 130 miles an hour in a corner, knee on the ground, separated by a few feet from other riders in a pack. (Such is the mutual trust of skilled professionals.) The mechanical contingencies of traction and gyroscopic precession become second nature, and are given no more thought than the hockey player gives to his stick while he is playing, or the blind man gives to his cane.

The philosopher Adrian Cussins writes about two different ways of knowing about speed. He relates the experience of riding his motorcycle around London, adjusting his speed in response to various weather and traffic conditions, and contrasts this with the way one knows one’s speed when one reads it off a dial or digital readout. In that case, speed is rendered as a number, and to learn the significance of this number one has to compare it with another number: the posted speed limit. But this “significance” is of a much thinner kind. Cussins’s point is that knowing one’s speed in this second way is to render speed as a proposition: I know that I am going forty-five miles per hour. This is a fact—the sort that has objective validity, but is divorced from the particular driving situation in which the motorcyclist finds himself. “Forty-five miles per hour” is not speed, it is a representation of speed. It has the virtue of standardization; it is the kind of fact that is transportable “from one embodied and environmentally specific situation to another.”

These two ways of knowing about speed “are taken up in very different, sometimes competing, cognitive orientations to the world,” as Cussins puts it. When the objective representation of speed interposes itself between the motorcyclist and his perception of his situation, it can interfere with his direct world-inhabiting. Cussins writes that “the great advantage of experiential content is that its links to action are direct, and do not need to be mediated by time-consuming—and activity-distancing—inferential work.”

If Cussins is right, reliance on a speedometer tends to subtly bump us out of a skillful way of driving, and this is due to the interference of objective knowledge with experiential knowledge. But Cussins doesn’t elaborate how this interference might happen. Following some clues in the cognitive science literature, I’d like to suggest that the interference is due to a substitution that occurs, wherein the symbolic representation of speed becomes an object of attention, displacing somewhat the ecological, sensorimotor experience of speed. Crucially, unlike the ecological experience, the symbolic representation of speed is “affect-neutral” (it isn’t scary), so it doesn’t prime the action programs (here, evasive maneuvers) that for an experienced rider have become integrated with his threat perception and have achieved a certain level of automaticity.

The negative affordances that a motorcyclist sees aren’t limited to things like oily spots on the pavement. The road is, after all, a social place. You do well to notice the brunette in the short skirt standing at the intersection, because the guy driving the car in front of you may slam on the brakes. But the old lady following closely in the car behind you won’t. You have been watching the old lady with interest. As far as you can make out in your vibrating mirror, she has a look of sour disapproval on her face, and it is directed at your taillight. You also notice the driver of the delivery truck that has just appeared at a side street. He appears to be laughing: he is engaged in a conversation with someone else in the cab of the truck, seated on the side opposite to the side that you are approaching from. The driver looks like just the slovenly sort who would pull out without double-checking. (Motorcyclists become ethnographers of necessity, or rather rank stereotypers, for the same reason that cops do: they face risk. Stereotyping is efficient for snap judgments.) Having been scared many times in the past, you are attuned to the kind of information that is important when riding in urban areas, and this information is different in kind from your instrument-read speed.

I suspect overreliance on the speedometer may slacken the bonds between action and perception, and indeed there is evidence that when our attention is diverted to symbolic representations, it can have such a loosening effect. This is what appears to be going on with a chimpanzee named Sheba who has been taught numerals. Andy Clark tells her story:

Sheba sits with Sarah (another chimp), and two plates of treats are shown. What Sheba points to, Sarah gets. Sheba always points to the greater pile, thus getting less. She visibly hates this result but can’t seem to improve. However, when the treats arrive in containers with a cover bearing numerals on top, the spell is broken, and Sheba points to the smaller number, thus gaining more treats.

The interpretation is that the numerals, because they don’t look tasty, “allow the chimps to sidestep the capture of their own behavior by ecologically specific, fast-and-frugal subroutines.” They provide “a new target for selective attention and a new fulcrum for the control of action.”

Abstracting from the concrete objects of their environment, the chimps become better at maximizing their utility. They become more Protestant, we might say: to get maximum treats in the future requires a bit of asceticism for the moment, and this becomes possible if you redirect your attention to something abstract, such as money (for the Protestant) or numerals (for the chimp). The abstract thing becomes “a new fulcrum for the control of action,” as Clark says. Thus is born civilization.

But when it comes to motorcycling, “ecologically specific, fast-and-frugal subroutines” are mostly a good thing, because everything happens very fast. Let us call them perception-action circuits. Just as reaching is triggered by the sight of something tasty for chimps and other non-Protestants, the solicitations of the motorcycling-specific environment trigger steering and other control inputs for the rider. These circuits are tied to affect: the kind of response you have to the sight of something tasty or something dangerous. In the case of a learned skill, these perception-action-affect circuits represent an achieved integration, and serve as the foundation for fluid, relatively effortless performance.

Is there a role for explicit thinking in this kind of performance?

Thanks for that.

I'm biased against Nazis. In the words of Indiana Jones, I hate those guys.

I shouldn't have called him overrated. I don't know nearly enough. I hate the guy.

Actually, on a quick squiz of my post it seems I didn't say he was overrated. But the quote from him was windy and decidedly not to my taste. It's the kind of stuff that I can be drawn into as if it contains something that would reward some real sympathetic pondering. And, based on how I respect lots of people who have a high regard for Heidegger, it probably would.

But on purely cost benefit grounds I desist. I doubt it would be of much help to me either in understanding stuff or in articulating it. That's got a lot to do with my own strengths and weaknesses in thinking about stuff and whom I'm interested in trying to think with — my 'audience' if you will. I don’t' think spouting Heidegger would be of assistance with the task of thinking with ordinary folks about the perplexities of the world we find ourselves in (dare I say, the world we've been 'thrown into' LOL.)

And he was a Nazi. Hate those guys!