In case you’ve not seen it yet

Australia’s equivalent of half-time at the Superbowl

Things that are obviously, frustratingly dumb

And would be dead easy to fix

You know when you’re answering a survey and the people who’ve sent you the survey won’t let you leave a space blank or a question unanswered. Generally I close the whole survey when that happens if I can. We were programming a survey for a consultancy project in a professional version of SurveyMonkey the other day and had to decide whether to put soft or ‘hard’ returns in. There should be a setting in which it gives you one ‘reminder’ and if you want to ignore the reminder it lets you return a blank. They’ve had 24 years to think of this idea, but here’s hoping one day it will come.

Why, (oh why? don’t computers delay going to ‘sleep’ if you leave them downloading something if going to sleep will stop the download.

To get a little more serious, why has almost no-one of any prominence talked about reforming the US presidential pardon power. It would require a constitutional amendment, but why wouldn’t the politics of campaigning for such an amendment and putting some bipartisan committee in charge of it be good politics for the reforming party? (I’d prefer it was selected by lot from the community, but I would say that wouldn’t I?)

And let’s not forget forecasting

The link in the second tweet is to my FT column on the subject.

Geriatric Joe, and his ‘cowardly and complacent’ party

Remember how the Democrat Party thinking it would be easy against clown candidate Donald Trump thought they could put up a terrible candidate to do an honour lap. At least she had genuine competition in the primaries. Joe Biden has, IMO been a good president. But he comes across as senile. Perhaps that’s just the effect of his very admirable struggle against a stutter. If so counting him out on those grounds would be unfair to Biden. The pity is, and I hate to go all utilitarian on you, but it would be unfair to a hundred million or more Americans. And yet, there’s not been a single really heavy hitting Democrat who has done the right thing and simply put their hand on Joe’s shoulder and said “Enough! And if you don’t call it quits I’ll blow up your campaign by saying the obvious publicly.” Not one.

Meanwhile, Kevin Munger tells us to get out the “Make America a Gerontocracy” hats, informing us that:

In 2024, either Trump or Biden would be the oldest person to win a presidential election. We have the second-oldest House in history (after 2020-2022), and the oldest Senate. A full 2/3 of the Senate are Baby Boomers!

Not only is the age distribution of US politicians an outlier compared to our past—we also have the oldest politicians of any developed democracy. And not just the politicians, but the voters, too: more Americans will turn 65 years old in 2024 than ever before—and given macro-trends in demography, maybe than ever again.

And here is the Economist

AMERICAN POLITICS is paralysed by a contradiction as big as the Grand Canyon. Democrats rage about how re-electing Donald Trump would doom their country’s democracy. And yet, in deciding who to put up against him in November’s election, the party looks as if it will meekly submit to the candidacy of an 81-year-old with the worst approval rating of any modern president at this stage in his term. How did it come to this? …

Mr Trump, leading polls in the swing states where the election will be decided, is a coin-toss away from a second presidential win. Even if you do not see Mr Trump as a potential dictator, that is an alarming prospect. A substantial share of Democrats would rather Mr Biden did not run. But instead of either challenging him or knuckling down to support his campaign, they have instead taken to muttering glassy-eyed about the mess they are in.

There are no secrets about what makes Mr Biden so unpopular. Part of it is the sustained burst of inflation that has been laid at his door. Then there is his age. Most Americans know someone in their 80s who is starting to show their years. They also know that no matter how fine that person’s character, they should not be given a four-year stint in the world’s hardest job.

Back in 2023 Mr Biden could—and should—have decided to be a one-term president. He would have been revered as a paragon of public service and a rebuke to Mr Trump’s boundless ego. Democratic bigwigs know this. In fact before their party’s better-than-expected showing in the midterms, plenty of party members thought that Mr Biden would indeed stand aside. This newspaper first argued that the president should not seek re-election over a year ago. …

Democratic leaders have been cowardly and complacent. Like many pusillanimous congressional Republicans, who disliked Mr Trump and considered him dangerous—but could not find it within themselves to impeach or even criticise him—Democratic stalwarts have been unwilling to act on their concerns about Mr Biden’s folly. If that was because of the threat to their own careers, their behaviour was cowardly.

Given this, you might think that the best thing would be for Mr Biden to stand aside. After all, the election is still ten months away and the Democratic Party has talent. Alas, not only is that exceedingly unlikely, but the closer you look at what would happen, finding an alternative to Mr Biden at this stage would be a desperate and unwise throw of the dice .

Were he to withdraw today, the Democratic Party would have to frantically recast its primary, because filing deadlines have already passed in many states and the only other candidates on the ballot are a little-known congressman called Dean Phillips and a self-help guru called Marianne Williamson. Assuming this was possible, and that the flurry of ensuing lawsuits was manageable, state legislatures would have to approve new dates for the primaries closer to the convention in August. A series of debates would have to be organised so that primary voters knew what they were voting for. The field could well be vast, with no obvious way of narrowing it quickly: in the Democratic primary of 2020, 29 candidates put themselves forward.

The entertainment that saved over 6,000 souls

An astonishing and wonderful story.

In 1902, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a few of the highlights in store for visitors at Coney Island’s soon-to-open “electric Eden,” Luna Park:

…the most important will be an illustration of Jules Verne’s ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’ … and a naval spectatorium. Beside these we will have many novelties, including the River Styx, the Whirl of the Town, Shooting the White Horse Rapids, the Grand Canyon, the ’49 Mining Camp, the infant incubator, water show and carnival, circus and hippodrome, Yellowstone Park, zoological gardens, performing wild beasts, caves of Capri, the Florida Everglades and Mont Pelee, an electric representation of the volcanic destruction of St. Pierre.

Hold up a sec…what’s this about an infant incubator? What kind of name is that for a roller coaster!? …

The real draw were the premature babies who inhabited these cribs every summer, tended to round the clock by a capable staff of white clad nurses, wet nurses and Dr. Martin Couney, the man who had the ideas to put these tiny newborns on display…and in so doing, saved thousands of lives.

Couney, a breast feeding advocate who once apprenticed under the founder of modern perinatal medicine, obstetrician Pierre-Constant Budin, had no license to practice.

Nor did he have an MD.

Initially painted as a child-exploiting charlatan by many in the medical community, he was as vague about his background as he was passionate about his advocacy for preemies whose survival depended on robust intervention.

Having presented Budin’s Kinderbrutanstalt — child hatchery — to spectators at 1896’s Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin, and another infant incubator show as part of Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Celebration, he knew firsthand the public’s capacity to become invested in the preemies’ welfare, despite a general lack of interest on the part of the American medical establishment.

Thusly was the idea for the boardwalk Infantoriums hatched.

Or watch this video

Glamour Feminism

In my endless scouring of the world and the internet for stories, I was deep into Glamour picking up all kinds of new tips — like the way Kelly Clarkson’s ‘style team’ have her wearing tight fitting clothes since she’s lost weight. Subscribers take note. (Is it OK to observe that it’s not all that much weight? I dare say it’s not! — slaps wrist, crosses out offending text).

Anyway, what should I come across but this article on how three global brands are coming together to end child marriage? And who better to represent global feminism than three talking heads, one who’s put an extra bit of effort into her makeup that morning (though no more than other mornings), all of whom are known to us because of their incomparable style. Oh — and I nearly forgot, the guys they married.

Glamour takes up the story:

Their star power is undeniable, and they’ve each commanded countless column inches. Of the three of them, two are accomplished lawyers (one married a man who would become the first Black president in US history; the other, a Hollywood star), and one is a computer science and economics major with an MBA who has become one of the world’s richest women.

Now that’s glamour. Anyway, needless to say, their cause is a fine one. And I expect women’s empowerment in poorer countries is one of the best ways to lift our species.

Cancel culture as the new lingua franca

More on Claudine Gay et al

In this age when talking points circulate — initially by email and then though the mouths of talking heads, it’s usually more worth one’s time reading a piece in which someone takes their own side to task. As here:

The hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman has had a busy few months. Mere days after the October 7 attacks, he was calling for the names of any university students who signed letters blaming Israel to be added to a public list — to make sure they didn’t get jobs in the future. In December, he led the social media campaign against former Harvard President Claudine Gay following her disastrous senate hearing — tweeting more than 100 times about her — until a mysteriously-funded dossier documenting her historic plagiarism instances helped ignite a flurry of negative headlines that finally forced forced her resignation. Last week, he floated the possibility of funding the same research against the leaders of MIT, Yale, Princeton, Stamford, Penn and Dartmouth. He might even invest in a startup to do it for him.

All of this activism has propelled him from just another Democrat megadonor and lockdown enthusiast to the latest hero of the political Right. But while you can understand conservatives’ excitement at sticking it to overpromoted DEI hires at elite universities, there has been a distinct lack of questioning over his methods. Putting the plagiarism to one side, surely conservatives should deplore these tactics on principle: publishing lists of people guilty of political wrong-think on university campuses, abandoning the much-vaunted value of free speech, orchestrating pile-ons and demanding resignations on social media. This is what they have been campaigning against for years.

This won’t be popular among my many conservative friends, but since the terror attacks in Israel on October 7 and the divisive war that followed, the tenor, emotion and heavy-handed tactics employed to control the current debate across campuses and throughout our institutions reminds me of how the BLM narrative was ferociously politicised during the summer of 2020. Back then, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, the people who lost jobs for incorrect political positions were almost entirely those who were critical of BLM or leftist identity politics. Since October 7, while the circumstances of each termination vary, the firings have all been of people holding pro-Palestinian views.

The departure of Gay, along with Liz Magill, the president of the University of Pennsylvania, has given conservatives much to celebrate. … But if you watch the full hearing, instead of just the clips, it is very clear what took place. Republican attack dog Elise Stefanik spends her entire questioning slot trying to trap the university heads in specific logical sequence: first, do they agree that calling for “intifada” and chanting “from the river to the sea” are direct calls for genocide? They refuse to concede this point, insisting (I think reasonably) that both terms are context-dependent, and that students must be allowed to express political opinions even if they are personally abhorrent to university administrators. At the end of the hearing, in her final round of questions, Stefanik returns to the theme, asking in summary whether calling for genocide of Jews constitutes bullying and harassment and is against their colleges’ code of conduct? If they were to answer a simple yes, then every student calling for “Intifada” or chanting “from the river to the sea” would have to face disciplinary proceedings, so naturally each university head refuses to bow to that logic and continues to insist that each incident would be a “context-dependent decision”. Hence the now-infamous smirks: everyone in the room could see what the congresswoman was trying to get them to say.

In the event, Stefanik won the day, because their prevaricating clip looked just as bad out of context. She went on to point out the hypocrisy of university administrators spending the past decade training students that “fatphobia” and “using the wrong pronouns” constituted violent and dangerous speech and yet couldn’t condemn actual calls for genocide. The argument landed. But consider the principles that have been conceded in the process of deploying it: not only should the most hateful and extreme interpretations of every word or phrase be used when judging them, but speech is, after all, violence. These are far-Left ideas that conservatives were supposed to be against.

Kathleen Stock has some similar observations here.

Good list

HT: Brad Delong

Tim Snyder: On Tyranny: ‘Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century…. 1. Do not obey in advance…. 2. Defend institutions. It is institutions that help us to preserve decency…. 3. Beware the one-party state…. 4. Take responsibility for the face of the world. The symbols of today enable the reality of tomorrow.… 5. Remember professional ethics…. 6. Be wary of paramilitaries…. 7. Be reflective if you must be armed…. 8. Stand out…. The moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken.…9. Be kind to our language…. 10. Believe in truth. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom…. 11. Investigate. Figure things out for yourself…. 12. Make eye contact and small talk…. 13. Practice corporeal politics…. 14. Establish a private life…. Have personal exchanges in person…. Tyrants seek the hook on which to hang you. Try not to have hooks. 15. Contribute to good causes. … 16. Learn from peers in other countries…. 17. Listen for dangerous words…. Be alive to the fatal notions of "emergency" and "exception."… 18. Be calm when the unthinkable arrives…. 19. Be a patriot…. 20. Be as courageous as you can…

A true shocker of a chart

Some more party politics

I realise on publishing this, that I don’t write or reproduce much on party politics. It’s so hard to take it seriously. By that I don’t mean that there’s no difference between the major political parties. There is and, at least IMO there’s a fair bit more to dislike about the right of centre offering. But each is so invested in brand and media management that it’s hard to take what they say seriously. Anyway, I agreed with this from my friend Tim Dunlop who also runs a nice line in AI illustrations (as illustrated above):

Since the 2022 election I have been speaking about the ways in which Labor has failed to recognise and capitalise on the changed political landscape. And while their blindness to what is happening is understandable—as it involves them thinking outside the box of the two-party system to which they belong—it is fatal nonetheless.

Politics doesn’t reflect some pre-existing majority already cohering within a society. The job of politics is to create that majority, and that is what they should be focussed on.

But not in the usual way.

In the traditional idea of the two-party system creating a majority has meant getting people to vote for your party, but in the three-party system we now have in Australia—where the third “party” is an ever-changing crossbench of independents, Greens and smaller parties—the process is more complex. You must be willing to create your majority outside your own party, and the thing is, Labor is much better positioned to do this than the Coalition.

If they would only let themselves recognise the fact.

We have to see all that is happening within the framework of an immensely altered communications environment because all politics is mediated. In short, the idea of ideology and information being centralised in a mainstream media that is mass has been usurped for more than twenty years now, and the way ahead isn’t clear because the old is still dying while the new is struggling to be born.

As ever.

What is a Malcolm?

Here’s a fun post by a friend of mine. Stian Westlake, the co-author with Jonathan Haskel of Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy and Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy.

If you’ve read popular nonfiction books in the past twenty years, you’ll have come across malcolms, even if you didn’t know what they were called. A malcolm is a lengthy anecdote used to begin a chapter, before the author gets to the actual point they’re trying to make. Let’s say the author has written a chapter arguing that that rivals make the best teams. Often nowadays they will begin the chapter with a long story about John Lennon getting in an argument with Paul McCartney, before recording a classic Beatles album, or about two rival basketball teammates, or whatever. The aim is to make the reader care about the more abstract points that the author wants by providing a tangible, relatable, surprising example.

Now don’t get me wrong: a good malcolm is a thing of beauty. Malcolm Gladwell, in whose honour they are named, uses them superbly, as you’d expect from one of the world’s most successful nonfiction writers. His stories are deeply engaging, and because he is a very skilled writer, they pivot weightlessly into the substantive points he writes about, making the reader emotionally engaged in what are often reasonably technical subjects.

They can be especially useful when the author of a book is a technical expert making a foray into writing for a general audience. Many specialists (such as economists) are a lot more comfortable with talking about trends and data, and a lot less interested in anecdotal examples than laypeople. This is often an advantage, because anecdotes can be misleading, but not if you’re trying to write for the general public. Writing malcolms can force quantitativrly minded writers to meet their reader half-way.

The problem is that, these days, malcolms seem to be absolutely everywhere. It’s as if a memo went out to every expert writing a popular book explaining that each chapter of their book has to begin with an anecdote, in the same way it has to have an index and page numbers. And as the quantity of malcolms has increased, the quality has declined.

(Quick aside: it’s very striking to skim through a few general popular nonfiction books — ie not great classics, just OK books that are now mostly forgotten, landfill nonfiction if you like — from the 1990s or before and see how much more variation in style there is. On the whole, pre-2000 nonfiction books strike me as noticeably less clearly written than books today — they’re more prone to abstraction and are less well signposted. They also seem to contain a lot of the kind of factoids and cliches that nowadays can be debunked with thirty seconds of Googling. But occasionally the stylistic variation you get in older books gives rise to something enjoyably quirky and distinctive, like Taleb’s Fooled By Randomness (which seems to have been written just before Gladwell’s first book was published; I wonder if it would be published now?). I suspect the success of writers like Gladwell and of books like Freakonomics and Nudge did a lot to improve the style of popular nonfiction books, but at the same time led to more homogeneity. I’d love to read something written by a nonfiction editor or agent who actually knows about this stuff explaining how the changes happened. But in the mean time, you’ve got me.)

Safely tucked away in the middle of the newsletter I shouldn’t have watched the whole 30 minutes. I should have been working on saving the world — but I did! (Watch the video, not save the world that is!)

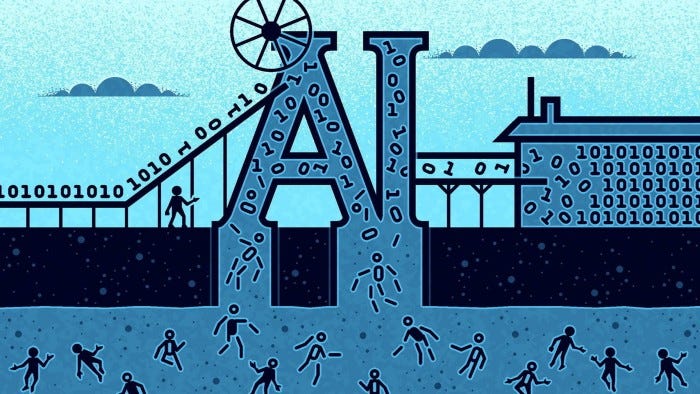

The use of AI to swell the profits of search

OK, so if AI takes a few ‘influencers’ down a financial peg or two, that’s fine with me. Less so all the rest.

Not only are publishers and content creators not getting paid fairly for the content used to train these models, but AI is also poised to seriously disrupt the business by which consumers search for information online. It could make the previous 20 years of Big Tech’s rapacious rent extraction from content creators look minor by comparison.

Right now, when people use a search engine to obtain information, they are shown results that may lead them to the websites of creators. The creators can then make money from the traffic through digital advertising. It’s a symbiotic relationship — which is not to say it’s equal. Ever since Google pioneered the business model of selling ads against search back in 2000, content creators have been more or less at the mercy of whatever revenue-sharing terms Big Tech wanted to offer, if indeed it offered any at all.

That started to change a couple of years ago, when Australia, followed by Canada, forced tech platforms to negotiate payments with publishers. That’s better than nothing, but the fees have amounted to a fraction of what many experts say is fair value. One recent study by researchers from Columbia University, the University of Houston and the Brattle Group consulting firm quantified the shortfall. They estimated that if Google gave US publishers 50 per cent of the value created by their news content, they’d be shelling out between $10-12bn annually. As it is, the New York Times — one of the largest news publishers — is getting a mere $100mn over three years.

Now, AI is poised to make even that asymmetric relationship look good. When you ask a chatbot such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Bard a question, you don’t get sent to a creator’s website. Rather, you are given the answer directly. Users remain in the walled garden of whichever Big Tech company owns the artificial intelligence platform.

The fact that the AI has been trained on the very same copyrighted content it aims to bypass adds insult to injury. It is not only traditional content creators who are worried. Brands are now creating their own virtual social media influencers with AI, so they don’t have to pay the $1,000 or so per post that some real influencers charge. The Hollywood actors and writers strikes last year were also about this race to the bottom, in which more and more creative, white-collar jobs will be done by software.

Some fun from Robert Hughes unfinished memoir

Graft—Things You Didn’t Know

Because there was such a lot of money swashing around in the system, it was inevitable that poorly paid art critics—particularly in New York, the very center of the market—should have felt entitled to a cut of it. Who took the first step in bringing an artist’s name before the small public of collectors and museum people? The art critic, very often, sharing an almost equal role with the art dealers. The art critic was supposed to be the truffle hound, the seeing-eye dog, as well as the validator. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were thousands of artists (nobody knew how many; it was entirely a matter of guesswork, as was the thornier question of how you defined “artist”) in Manhattan and, less impressively, the surrounding boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn. The art critic (it was assumed, at least in theory) moved through all these confusing circles, picking up from artists their opinions (or gossip) on which other unknowns might be worth watching, constructing patterns of affinity and similarity—not “movements” exactly; the day of the “movement” was fading, and would soon be completely extinct except as a journalistic fiction—and in general keeping a watch on what might become hot. It seemed so obvious that an art critic should be judged in terms of his or her “discoveries” that nobody questioned it.

Now, of course, in art, as in geography, the word “discover” is an extremely relative and shifty verb. Columbus did not “discover” America; the Americas, north and south, were already full of people. What Columbus did was sail and log a route by which he could get to the Caribbean from Spain and then get back to Europe, so that other Europeans could do the same. He never actually glimpsed the American mainland. People used to speak of Europeans “discovering” Australia when Captain James Cook, in 1770, reached its east coast in his ship the Endeavour. But by then the existence of the same continent—only the west coast of it—had been attested to by a number of mariners, mainly Dutch but some English too, as far back as the seventeenth century. A large piece of a quite accurately drawn Australia, mapped by Chinese navigators, appears in a map, the Ricci, circa 1600, in the royal palace archive in Beijing. So it is rarely possible, in real life, to attach a firm geographical meaning to the idea of “discovery.”

Much the same quite often holds true in the visual arts. Artists don’t just appear out of thin air at cultural intersections, from complete obscurity into conspicuousness, just because a single critic (or collector, or curator) gives them a push off the tailgate. They are generally known to people, to other artists (who are the fount and origin of all reputations), before any of these cultural go-betweens reaches them. From there, the slope of reputation is quite often rapidly scaled—though not always—but the growth of an artist’s reputation is and always has been to some degree a matter of consensus. Artists alert a critic; critics talk to one another; buzz goes to or comes from a dealer; collectors try to get in early; and so the word spreads—if the market for new art is heated. If it is not hot, the process is slower and rather more circuitous. But it almost always depends on consensus. The cases in which an artist’s reputation is put into orbit by one person’s influence and opinion are extremely rare. They have existed, though, as commemorated by the little sestet attributed to a failed nineteenth-century artist:

I takes and paints

Hears no complaints

And sells before I’m dry:

Then savage Ruskin

’E sticks ’is tusk in,

And nobody will buy.

But in general, the “power” of the critic is something you can either believe in or not, and if you believe in it you are probably wrong, because it is so largely the product of others’ belief. It is not dissimilar to the way the stock market rises and falls: it is all about perception. All sorts of people did believe in Clem Greenberg’s taste, and now they do not; the pictures remain the same, but the spirit in which they are received is different. Greenberg, who died in 1994, is a perfect case of the art critic’s similarity to the great and mighty Wizard of Oz, pulling strings and pushing buttons behind the curtain. For a time, roughly from the early fifties to the early seventies, his judgments were regarded by much of the art world as close to infallible. Ritual obeisance was paid to his sensibility, his “eye.” (“Do you know what Clem says about you?” one of his acolytes scornfully asked me in the mid-seventies. “He says you can write, but you’ve got a bad eye.” It was as though he had been confused with an ophthalmologist.) Greenberg’s reputation was initially made possible by the small size of the New York art world in the 1940s and ’50s. It had few critics in it (the only other one of comparable weight was Harold Rosenberg, a far more interesting writer, and the two men loathed one another), only a small handful of galleries that were interested in “radical” American art, and relatively few museum people on its side. Alfred Barr, founder and chief of the Museum of Modern Art, was an enthusiastic apostle of European modernism. Indeed, that was his mission in life; but for abstract expressionism he cared much less, whereas Greenberg was credited with putting Jackson Pollock on the map and thus, more than any other writer, initiating the imperial status of modern American art. In a small art community, one determined and dogmatic individual can have a great deal of influence and even be credited with magus-like insights, and so it was with Greenberg. When more people are involved in the production, distribution, and appreciation of art, there is more room for difference of opinion, and the magus mojo gets diluted. This is why no one in America today enjoys the kind of reputation Greenberg had in his heyday; you would need to be a natural bully to want it, and a fool to expect it.

But it astonished me, when I first got to New York, to see what reverence his name evoked. Who, the dealer André Emmerich once asked me (this must have been in 1971), did I think the really great critics had been? I named four or five names, of whom by far the greatest, in my opinion, was that prodigy of eloquence and passion John Ruskin. “Ruskin?!” the eminent dealer exclaimed. “What about Clem?” And when I tried to explain why I didn’t think Greenberg deserved to be ranked anywhere near the mighty author of Modern Painters, as a prose stylist, an analyst of painting, a creative force in his own right, or as a mind engaged with the largest possible span of Nature and Culture, it was clear that I was getting nowhere fast.

Greenberg was in my opinion a mediocre writer. He wrote serviceable prose, whose main merit was that it didn’t poeticize. He eschewed the soft metaphoric fancies that so often accompanied attempts to write about the visual arts. This, in the 1950s, was a distinct virtue. He was also the first influential critic to write about Pollock in terms of the highest enthusiasm, and that perception can never be taken away from him: “A kind of demiurgic genius.” However, it did not follow, as many an artist and collector none-too-secretly expected, that because he had got the point—or some of the point—of Jackson Pollock, then other artists he went for might have Pollock potential. He had nothing of interest to say on the subject of figurative painting; his stern division of art into “real art” and “kitsch” has not lasted well, and was debilitated (not that he ever conceded that) by the advent of pop art and its various offshoots. When dealing with “pure” abstract art, his renowned “eye” was quite fallible and sometimes let him down badly, as happened with his enthusiasm for that melodramatic bore of an abstractionist Clyfford Still, with all his sturm und drang, Night on Bald Mountain effects. Above all, it seems true that he was a quite limited critic, not interested in the content of works of art or their historical context, only in their formal character; that he had little or nothing of interest to say about any art earlier than impressionism, and that he spent much of his later life pushing something called “post-painterly abstraction,” a category of large, thinly painted, watercolory abstract painting which contained some fairly meritorious artists (Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis) but no peg comparable to Pollock or early de Kooning on which the fickle muse of history could hang her tunic. Consequently, his pronouncements were often without much argued weight, although they were credited with it; they emerged from strong cultural enthusiasms, but not from a deep grounding in the traditions that lay beyond and behind modernism. All in all, Greenberg has not worn well, either as a model for aspiring critics or as a prophet of the future.

“What is nakedly and explicitly at stake” in Morris Louis’s paintings, wrote the ardent Greenbergian academic Michael Fried, “is nothing less than the continued existence of painting as a high art.” One wishes there were a polite way of saying “Oh, bullshit!” to vatic utterances like these. Nothing of the sort ever depended on any of the post-painterly painters Greenberg and his A-Team favored, any more than it completely depended on Jackson Pollock. There are parts of Pollock that look extremely slight despite the good bits, and there are other painters who would look just as good if Pollock had never existed. When Pollock declared that “I am Nature,” he didn’t mean to say “I am History.”

Moreover, in place of the authority granted by the past, Greenberg’s way of imposing himself on the little parody of the real world known as the “art world” lay through an irascible temper and a fund of raw aggression. He was by nature a bully, and none the less so for his heavy drinking. Before the early seventies, the time I came in contact with him, he had hooked up with a strikingly bizarre therapeutic movement which might better be described as a cult: the Sullivanians.

This therapeutic sect was founded by Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949), a homosexual psychiatrist whose main claim to fame was that he devised, for the United States Army, a system of criteria by which homosexuals could supposedly be identified and thus weeded out of military service. (Are his wrists limp? Does he lisp? In civilian life, did he own a Chihuahua with a rhinestone collar? Not quite that sort of thing, but almost.) Poor Sullivan seems never to have realized that he was a kind of Quisling to his own sexual nature. Control of the therapeutic “movement” he started, however, passed in the 1960s to one of his followers, a mad and messianic ex-Communist named Saul Newton. Newton had no psychiatric training of any kind, but he regarded himself as an inspired guru. “In psychology there is Freud, Sullivan, and Newton. In politics there is Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Newton,” he told his growing circle of disciples. He boasted of having fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade against Franco in Spain during its civil war, although he seems to have served merely as a payroll clerk; the stories he told of his decisiveness and brutality as a commissar, to impress analysands, appear to have been quite fictional. Newton’s thinking was pure Cold War paranoia, and it appealed to the paranoically exclusive, a type never in short supply in New York. In a book published in 1963 and entitled The Conditions of Human Growth, which he cowrote with an equally delusional colleague, Jane Pearce, he remarked that “we live in a dangerous world. The technical advances of the twentieth century have hurled us into the necessity, in order to survive, of inventing hitherto unconceived social forms.” To propagate these forms, he and Pearce founded a group called the Sullivan Institute, and managed, with contributions wrung from wealthy “trainees,” to purchase three apartment buildings on Manhattan’s Upper West Side as the cult’s headquarters and living space. Here, his pliant “Sullivanians” met for their therapeutic sessions, and not infrequently lived full-time. In broad outline, the beliefs of the Sullivanians followed the template of many another exclusivist, wacko American sect. That is to say, the membership had to be perfect and insulated from contamination by other, less enlightened beings. The Sullivanians were expected to live communal or at least collective lives. The biological family was the real enemy of sanity. All parental relations were stigmatized as inherently “destructive.” (Greenberg, for this reason, refused to have anything to do with his own son, who had been born in 1935.) Sullivanians were discouraged from having children. If any children remained with their biological parents, they must be raised by others, apart. If biological parents wanted to be in touch with their children, they were called “destructive.” The fear of nuclear war, so much a part of social feeling in the 1960s, pervaded the Sullivanians and induced them to purchase some buses, in which, they believed (or at least hoped), they could flee from New York if the nukes showed signs of dropping and find refuge from radiation poisoning in Florida. And later, when the AIDS panic struck, there was all the more reason for the Sullivanians to close their sexual ranks, and deny themselves all outside social/sexual contacts.

In sum, just another club of all-American screwballs, waiting for the apocalypse in their own loopy messianic way. Greenberg was converted to Sullivanism by Janet Pearce herself, and his adherence to the Sullivanian cult demonstrated what had already long been a therapeutic commonplace: that intelligence is no vaccine against superstition, particularly when that superstition is linked to self-aggrandizement—which, in Greenberg’s case, it was.

Most of the artists whom Greenberg had saluted and done much to beatify as the best in America and the bearers of its cultural future—Jules Olitski, Larry Poons, Kenneth Noland—as well as many in the art faculties of Syracuse University and Bennington College, came within the rigid embrace of the Sullivanian/Newtonian cult, and this only served to increase their belief in Greenberg as a magus and prophet. He actively proselytized for this group and its therapeutic fantasies, and for a while seemed to be displacing the crackpot Newton as its leader. The reward of assent, for an artist, was to have Greenberg behind your work, arranging shows, making recommendations to wealthy private collectors and “important” museum curators. But the fullest fruits of those rewards were likely to be reserved for other Sullivanians.

It could at least be said for Sullivanism that it didn’t posture as a religion, unlike the even more superstitious and exploitive “Church” of Scientology. But its teachings, with their ruthlessly egotistical separation of sheep from goats, and their assignment of near-absolute power to the “therapist,” might have been tailor-made for Greenberg’s own exclusiveness and authoritarianism. Sullivanism was cult bullying masquerading as therapy, and it had a particular appeal to people with ironclad egos and an invincibly “either/or” mindset, such as Greenberg.

This mindset produced, in the end, a humiliating setback which turned into a disaster for Greenberg: the David Smith affair.

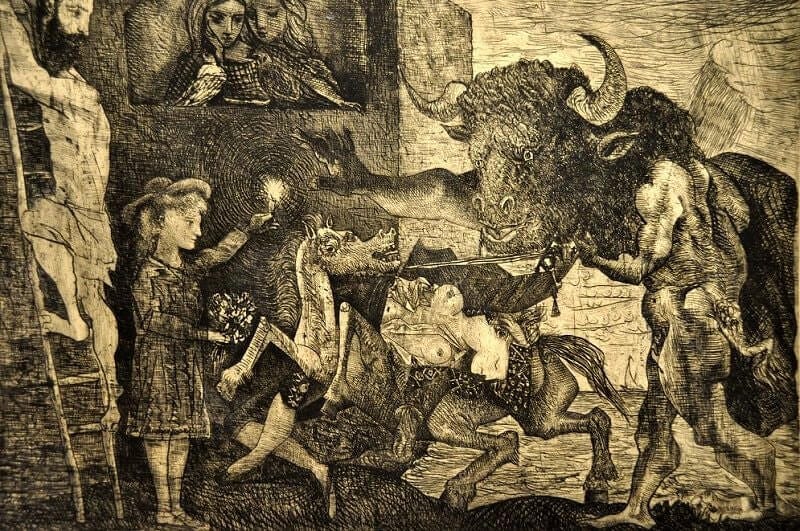

Creativity and the Minotaur, by Ben Okri

For Rosemary Clunie

Every true work of art is an enigma. But Picasso’s ‘Minotauromachy’ doubles its power by being an enigma about an enigma. This masterpiece of etching is a pure piece of visual paradox and symbolic prophecy. Executed in the thirties, during the atmosphere of gathering wars, it positively bristles with terror foreshadowed, with darkness already present.

The Minotaur is an old and deep figure in the consciousness of humanity. Out of the depths of our past, it has re-emerged on the stage of history. Half-man, half-bull, it dominates the landscape of this work, blocking out the light, cornering all the other figures. The Minotaur is no longer at the centre of the ancient Cretan labyrinth: it is in the centre of the picture, and the world stage. It has broken out of its lair. The Minotaur is the enigma at the heart of the modern age.

For Camus, the Minotaur is boredom – the boredom that devours the vitality of the young. For Picasso it is more sinister and complex. The Minotaur’s presence makes the world claustrophobic. Its brutish head is inescapable. Roles have been reversed: the Minotaur is striking back. Because we have failed to transform the animal within our labyrinth, the animal within is conquering us, unleashing vengeance.

The awesomeness of the Minotaur is reflected in the frenzied contortion of the horse and the murdered beauty on its back. The bearded man, who should be the defender, is seen fleeing up a ladder. The ladder leads nowhere. His backward-twisted head is the measure of his panic.

Only a little girl faces the Minotaur. She holds a candle aloft in one hand, and proffers flowers with the other. Her serenity is astonishing. The great Minotaur stares at her, sword pointed, but she isn’t really looking at him. Her eyes do not judge, her gaze seems to see beyond the horror. She doesn’t seem to see the spectre in front of her. She does not see the monster. She is not aware of the danger. Her gaze is gentle. Maybe she doesn’t see him as a monster. Maybe she sees him as a big, blind, unloved thing. Maybe the candle is there because she needs light to see by, to offer him flowers. Maybe it’s the symbol she offers, the light she shows, which really halts and confounds the enigma.

Might can always be greater than might: and violence would never have conquered the Minotaur. In a sense, the Minotaur cannot be conquered. It, too, is a part of life, of us, a part of life’s duality. The Minotaur, therefore, is not evil. Repellent, sad, a touch pathetic, and fascinating, it is an ambiguous figure. It represents something in us, something that has been ignored, or gone out of control. But when this irrational self bursts out, rampant, what recourse do we have? It is all in the girl, Picasso says, in the purity of heart and motive, in light, and in seeing clearly. This etching is part fairy-tale, asking us to believe in the power of symbols and the gentle triumph of wisdom and love.

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?With the figure of that little girl Picasso answers Shakespeare’s anguished question.

We always need to be reminded of forgotten higher things. True artists are wiser than we think.

Click through for magical skies

Heaviosity half-hour:

J. L. Austin: who knew? (Not me!)

I’ve never tried to read J. L. Austin whom Wikipedia tells us was “a British philosopher of language and leading proponent of ordinary language philosophy. I don’t think ordinary language philosophy is going to help me much understanding the world. And I doubt if I’ll press on. But usually when you run into these leading lights, they are, unsurprisingly, very impressive in their own way. Those who’ve found it to these heavier texts in my newsletters will know that I’ve got it in for a certain kind of scientistic reductionism which I think of as ‘boys own metaphysics’ (It’s turtles all the way down.). Hence my enthusiasm last week for the new turn biology seems to be taking — the turn that Michael Polanyi tried to sketch out eighty years earlier.

Be that as it may, I was enchanted with the classiness of Austin’s scepticism about one manifestation of a similar kind of reductionism — the craze for starting discussions of perception and meaning from ‘sense-data’. I say I won’t read much more, because while I think this is delicious critique, I’m sceptical it takes us to understanding things better. But I get to take away what I came for, because I found this lecture — Austin’s first in course of lectures — going to the source of something he says. “(There's the bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back.)” LOL.

IN THESE LECTURES I AM GOING TO DISCUSS some current doctrines (perhaps, by now, not so current as they once were) about sense-perception. We shall not, I fear, get so far as to decide about the truth or falsity of these doctrines; but in fact that is a question that really can't be decided, since it turns out that they all bite off more than they can chew. I shall take as chief stalking-horse in the d.iscussion Professor A. J. Ayer's The Foundations of Empirical Knowledge; but I shall mention also Professor H. H. Price's Perception, and, later on, G. J. Warnock's book on Berkeley. I find in these texts a good deal to criticize, but I choose them for their merits and not for their deficiencies; they seem to me to provide the best available expositions of the approved reasons for holding theories which are at least as old as Heraclitus-more full, coherent, and terminologically exact than you find, for example, in Descartes or Berkeley. No doubt the authors of these books no longer hold the theories expounded in them, or at any rate wouldn't now expound them in just the same form. But at least they did hold them not very long ago; and of course very numerous great philosophers have held these theories, and have propounded other doctrines resulting from them. The authors I have chosen to discuss may differ from each other over certain refinements, which we shall eventually take note of-they appear to differ, for example, as to whether their central distinction is between two 'languages' or between two classes of entities — but I believe that they agree with each other, and with their predecessors, in all their major (and mostly unnoticed) assumptions.

Ideally, I suppose, a discussion of this sort ought to begin with the very earliest texts; but in this case that course is ruled out by their no longer being extant. The doctrines we shall be discussing — unlike, for example, doctrines about 'universals' — were already quite ancient in Plato's time.

The general doctrine, generally stated, goes like this: we never see or otherwise perceive (or 'sense'), or anyhow we never directly perceive or sense, material objects (or material things), but only sense-data (or our own ideas, impressions, sensa, sense-perceptions, percepts, &c.).

One might well want to ask how seriously this doctrine is intended, just how strictly and literally the philosophers who propound it mean their words to be taken. But I think we had better not worry about this question for the present. It is, as a matter of fact, not at all easy to answer, for, strange though the doctrine looks, we are sometimes told to take it easy — really it's just what we've all believed all along. (There's the bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back.) In any case it is clear that the doctrine is thought worth stating, and equally there is no doubt that people find it disturbing; so at least we can begin with the assurance that it deserves serious attention.

My general opinion about this doctrine is that it is a typically scholastic view, attributable, first, to an obsession with a few particular words, the uses of which are oversimplified, not really understood or carefully studied or correctly described; and second, to an obsession with a few (and nearly always the same) half-studied 'facts'. (I say 'scholastic', but I might just as well have said 'philosophical'; oversimplification, schematization, and constant obsessive repetition of the same small range of jejune 'examples' are not only not peculiar to this case, but far too common to be dismissed as an occasional weakness of philosophers.) The fact is, as I shall try to make clear, that our ordinary words are much subtler in their uses, and mark many more distinctions, than philosophers have realized; and that the facts of perception, as discovered by, for instance, psychologists but also as noted by common mortals, are much more diverse and complicated than has been allowed for. It is essential, here as elsewhere, to abandon old habits of Gleichschaltung,* the deeply ingrained worship of tidy-looking dichotomies.

I am not, then — and this is a point to be clear about from the beginning — going to maintain that we ought to be 'realists', to embrace, that is, the doctrine that we do perceive material things (or objects). This doctrine would be no less scholastic and erroneous than its antithesis. The question, do we perceive material things or sense-data, no doubt looks very simple-too simple-but is entirely misleading (cp. Thales' similarly vast and over-simple question, what the world is made of). One of the most important points to grasp is that these two terms, 'sense-data' and 'material things', live by taking in each other's washing-what is spurious is not one term of the pair, but the antithesis itself.** There is no one kind of thing that we 'perceive' but many different kinds, the number being reducible if at all by scientific investigation and not by philosophy: pens are in many ways though not in all ways unlike rainbows, which are in many ways though not in all ways unlike after-images, which in turn are in many ways but not in all ways unlike pictures on the cinema-screen-and so on, without assignable limit. So we are not to look for an answer to the question, what kind of thing we perceive. What we have above all to do is, negatively, to rid ourselves of such illusions as 'the argument from illusion'-an 'argument' which those (e.g. Berkeley, Hume, Russell, Ayer) who have been most adept at working it, most fully masters of a certain special, happy style of blinkering philosophical English, have all themselves felt to be somehow spurious. There is no simple way of doing this-partly because, as we shall see, there is no simple 'argument'. It is a matter of unpicking, one by one, a mass of seductive (mainly verbal) fallacies, of exposing a wide variety of concealed motives — an operation which leaves us, in a sense, just where we began.

In a sense — but actually we may hope to learn something positive in the way of a technique for dissolving philosophical worries (some kinds of philosophical worry, not the whole of philosophy); and also something about the meanings of some English words ('reality', 'seems', 'looks', &c.) which, besides being philosophically very slippery, are in their own right interesting. Besides, there is nothing so plain boring as the constant repetition of assertions that are not true, and sometimes not even faintly sensible; if we can reduce this a bit, it will be all to the good.

* I put into Perplexity AI and got this explanation:

Gleichschaltung, a term used by J.L. Austin, refers to the process of achieving rigid and total coordination and uniformity in politics, culture, and communication. It involves the forced repression or elimination of independence and freedom of thought, action, or expression, leading to a forced reduction to a common level or standardization. In the context of J.L. Austin's usage, Gleichschaltung may have been employed to illustrate the concept of linguistic or communicative coordination and uniformity. This term is historically associated with the Nazi regime's efforts to coordinate and control all aspects of German life, including political, social, and cultural institutions, in line with Nazi ideology and policy. Therefore, in the context of Austin's usage, Gleichschaltung likely conveys the idea of coercive linguistic or communicative standardization and control.

** The case of 'universal' and 'particular', or 'individual', is similar in some respects though of course not in all. In philosophy it is often good policy, where one member of a putative pair falls under suspicion, to view the more innocent-seeming party suspiciously as well

From: Austin, J. L. 1962 Sense and Sensibilia. Lecture 1.

Some readers may be aware of the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend who cavilled at the incipient intellectual authoritarianism of much philosophy about ‘scientific method’. As his memoirs makes clear, he was happy to use provocative language and so wrote a book called Against Method and acquired a reputation as a methodological ‘anarchist’.

So I was intrigued to run into this passage from his memoirs Killing Time: The Autobiography of Paul Feyerabend which mentions Austin favourably.

Today I am convinced that there is more to this "anarchism" than rhetoric. The world, including the world of science, is a complex and scattered entity that cannot be captured by theories and simple rules. Even as a student I had mocked the intellectual tumors grown by philosophers. I had lost patience when a debate about scientific achievements was interrupted by an attempt to "clarify," where clarification meant translation into some form of pidgin logic. "You are like medieval scholars," I had objected; "they didn't understand anything unless it was translated into Latin." My doubts increased when a reference to logic was used not just to clarify but to evade scientific problems. "We are making a logical point, " the philosophers would say when the distance between their principles and the real world became rather obvious.

Compared with such doubletalk, Quine's "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" was like a breath of fresh air. J. L. Austin, whom I heard in Berkeley, dissolved "philosophy" in a different way. His lectures (later published as Sense and Sensibilia) were simple, but quite effective. Using Ayer's Foundations of Empirical Knowledge, Austin invited us to read the text literally, to really pay attention to the printed words. This we did. And statements that had seemed obvious and even profound suddenly ceased to make sense. We also realized that ordinary ways of talking were more flexible and more subtle than their philosophical replacements. So there were now two types of tumors to be removed—philosophy of science and general philosophy (ethics, epistemology, etc.)—and two areas of human activity that could survive without them—science and common sense.