The poverty of wokeness

An excellent review of no less than five anti-woke books of cultural criticism, from right, left and centre. It’s a long piece from crossover mag Compact, but they’ve released it from their paywall and I suggest you check out the whole thing.

Over the past year, a slew of polemics against progressive identity politics have appeared in print—an anti-woke publishing boom that rivals the woke boom that began a decade ago. The more interesting of these critiques converge on the conclusion that what occurred over the past decade was, above all, a process of elite radicalization that redounded to the benefit of well-positioned professionals who turned identity into a currency of social advancement. Depending on their politics, anti-woke polemicists may deplore this development because it forestalls more comprehensive projects of social transformation, or because it degrades institutions they don’t think should have been transformed at all. One of the most significant achievements of wokeness was to distract many of its opponents from these differences, and from the fundamental political questions underlying them. …

The imperatives drawn from the white rediscovery of racial fatalism in the 2010s were very different. They typically entailed not countercultural rebellion or societal exit, but a submission of the self to ever-evolving, and increasingly institutionalized, moral strictures (for one thing, avoiding the sort of “cultural appropriation” Mailer had observed approvingly). The demand wasn’t that society be abandoned—but remade, especially by way of an expansive bureaucratic apparatus of moral oversight. Those who capitalized on these trends weren’t countercultural outsiders, but the stakeholders of leading cultural, political, and economic institutions. If Mailer’s contemporaries had sought to extricate themselves from the “square” American mainstream, in our own time, it was the mainstream itself that sought a new animating sensibility—and found it in a body of writing that condemned it as irredeemably racist. …

the academics Walter Benn Michaels and Adolph Reed have long contended that the left’s turn away from class and toward a hodgepodge of racial, ethnic, gender, and other identities was always reactionary in its political implications. “Identity politics,” they write, is “the politics of an upper class that has no problem with seeing people left behind as long as they haven’t been left behind because of their race and sex.” Or as Reed puts it elsewhere, “identitarianism meshes well with neoliberal naturalization of the structures that reproduce inequality.” Which is to say, DEI ideology in effect claims that a society in which a tiny minority holds most wealth—ours—would be just if only that minority’s racial composition matched the population’s; hence, the pursuit of social justice amounts to diversifying Harvard and the C-suite, even as prospects for the poor and working classes of all races worsen.

“Identity politics is at bottom a small-c conservative ideology.”

The basic contours of DEI ideology were evident to anyone on the academic left well before the general population had encountered them, and well before the woke wars, Michaels and Reed were making the case that identitarian politics serve to legitimate neoliberal inequality. Their essays on the subject, which originally appeared in various small left-wing journals, have now been collected in the volume No Politics but Class Politics, along with four recent interviews with both authors conducted by the European Marxist academics Daniel Zamora and Anton Jäger, who co-edited the anthology. The fact that a book focused on peculiarly American racial politics was put together by two Belgian-based academics and published by a British imprint is a reminder of the continued marginality of Reed’s and Michaels’s views within the US left—but also of the increasing influence and relevance of American racial discourse for readers abroad.

Rufo more or less concedes what Michaels, Reed, and other dissenters on the left have long claimed: that identity politics is at bottom a small-c conservative ideology, not a revolutionary one as its adherents and some of its detractors claim. Its function is to legitimize existing power relations, not overturn them; it does this by expanding bureaucratic oversight, implementing quotas, and the like. Few young people who took to the streets in the 2010s believed their cause amounted to an expansion of certain sectors of the white-collar workforce, but in effect, it did.

The life and soul of the party

That cute pets algorithm has got a nasty hold of me.

Regarding this video, you know the guy who is thoroughly into himself, just so thrilled with himself, but no one else can quite see it?

Well, in an innocent kind of way this dog is similar. The dog is thrilled to be the dog he is. And why wouldn’t you be? And thrilled to be alive. The cat (not unusually for a cat), remains unimpressed.

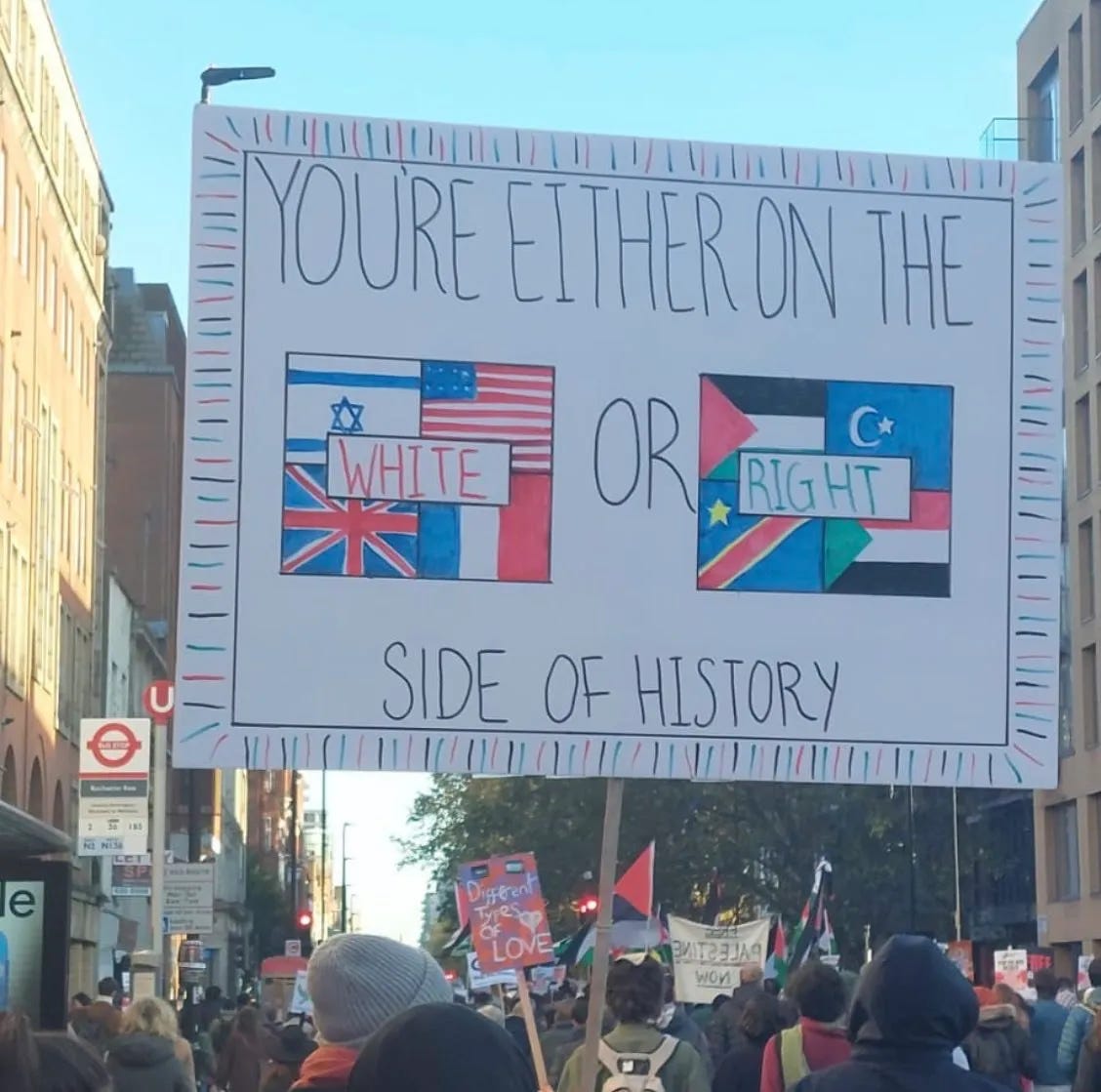

A different shade of anti-imperialism

Taking out the post-colonial trash

I’m way too ignorant on the subject to offer this to you as the right way to think, but it made sense to me. And I learned a lot reading it. And it’s extraordinary how the left tiptoes around the issues. In a review of The wretched of the earth, Warby argues that it's author, post-colonial theorist Franz Fanon operates in the realm of myth-making rather than sensemaking. Which ties into my own concerns, as per James Burnham as he transitioned from the Trotskyist left to the conservative right, that over nine-tenths of political speech — from the academy to the street — is saturated with wish fulfilment rather than empirical content. I don’t see why such a thought is inherently right wing, but it seems those on the left — even the moderate left — aren’t very comfortable with it.

Progressives are perennially prone to recurring failure of analysis when it comes to imperialism by refusing to see it for what it is: a state phenomenon. Progressive policy claims rest on the notion that handing things to the state is how good things are achieved. If imperialism is inherently a state activity (as it is), then the state becomes much more problematic as an instrument for social progress.

The metropole of every single modern maritime empire became richer after losing its empire. Imperialism regularly parades itself as an instrument of national glory and wealth. Imperial state apparats seek to mobilise various interest groups—for instance, religious evangelism—to support and justify their expansion of territorial control. Imperialism remains, however, a state activity, in the service of the state apparat itself—including the ruler or rulers on top.

Sometimes, licensed (or not so licensed) adventurers may lead imperial expansion. The Spanish conquistadors and the various overseas corporations—most famously the British and Dutch East India Companies—operated this way. Imperial expansion from the periphery was a persistent pattern. Imperialism of this type only “stuck” when incorporated within an imperial state structure, sometimes via some franchise arrangement. …

So, if Fanon’s history is cherry-picked to uselessness, and his analytical framings are meaningless, with what is one left? Molten prose that feeds a Manichaean world view. Wretched has mythic—not analytic—power.

Fanon in Algeria was neither French nor Algerian. Fanon was Afro-Caribbean, so a descendant of slaves whose ancestors were almost certainly enslaved by fellow Africans. Due to its geography, Africa was a continent where labour was perennially scarcer—and so more valuable—than land. Hence Africa was for millennia a continent of enslavement. This fed into the Islamic and Atlantic slave trades.

Fanon’s identification with Arab Algeria—Berbers/Amazigh are notably absent from his commentary—is an identification with an imperial, settler, enslaving culture by an ancestrally displaced descendant of slaves. This culture was still an enslaving culture at the time of the French conquest.

In colloquial Arabic, the term for Sub-Saharan Africans is abd—creature or slave. Whether the French-speaking Fanon was aware is unclear. This culture and civilisation pioneered anti-black racism precisely because it was a morally universalist enslaving culture—so had to find excuses for enslaving fellow children of Allah. …

Fanon also attributes patterns of state control to colonialism that are general patterns of state rule. Peasant revolts, for instance, are a hardy perennial in farming polities.

Fanon himself was a product and a denizen of the Francophone world. He is, understandably, enraged at a Francophone civilisation that made to include him, paraded its universalist values, and then repeatedly reminded him that he was “black”.

Racialisation was a product of imperialism, colonialism and cross-continental slavery in civilisations with claims to moral universalism: if everyone is equal before God, then enslaving fellow believers has to be justified in some way or another. This is why racism has been in such serious decline in post-imperial Western countries.

UK’s Robodebt (and then some!)

Solitude, loneliness and living alone

A good review of what looks like an interesting book.

“I had increasingly been feeling as if something had gone wrong,” writes Daniel Schreiber in his affecting examination of living alone. … It wasn’t as if he had been left behind, unlucky in love. Instead, after a youthful flurry of relationships he began to seek out solitude and wondered if there was enough room in his life to accommodate a partner. His book, Alone, is an extended meditation on the solitary life, set against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Schreiber is the author of several literary essays and biographer of Susan Sontag. The original edition of this memoir was a bestseller in Germany and stands out among the flood of books addressing our supposed epidemic of loneliness. The idea that social connection is the key to happiness and disconnection the root of mental ill health has become the new commonsense, stamped into our consciousness by lockdowns and compelled distancing. Many writers have offered diagnoses of the problems of loneliness and prescriptions for overcoming it, but few provide such a vivid first-person account and fewer still bring such an erudite sensibility to the task.

The backbone of Alone is life-historical. In 2019 Schreiber has an epiphany that things are going wrong; by Christmas “I stop believing that this life, as I live it, as I live it alone, is a good life.” … Off this narrative spine Schreiber hangs a series of meditations on the solitary condition, heavily supported by big thinkers. His intellectual tastes run philosophical and French, and anyone with a passing acquaintance with the humanities in the 1980s and 1990s will recognise many of his theoretical muses: Barthes, Derrida, Foucault, Lacan, Lyotard. At times the insights are rich, especially in contrast to the shallowness of some psychological and sociological accounts of loneliness, but at other times the price seems high. I had hoped never again to encounter the word “phallogocentrism,” but there it was. And do we need a deconstructionist to tell us that we should not insist our friends conform to all of our wishes?

Schreiber’s analysis of friendship is powerful, pointing out its many forms and virtues — it is non-exclusive, voluntary, enduring — but showing how often it is made to defer to coupledom and the “grand narrative” of romantic love. …

He is equally incisive and contentious on the topic of loneliness. … Schreiber writes of the pleasures and benefits of solitude, admitting to enjoying some aspects of pandemic isolation. … Some hand-wringing about the loneliness epidemic is reactionary, he suggests, motivated by nostalgia for the traditional family. …

Schreiber makes no attempt to hide his ambivalence about being alone. He can present himself as bravely fronting the challenges of solitude and rising above coupled conformity but also admit to holding petty resentments and vulnerabilities. He can clothe his loneliness in grand ideas and social critique but also express his unhappiness with naked honesty. In one breath he flays romantic relationships and claims not to want them anymore, and in the next he confesses to feeling unlovable. …

Schreiber is a perceptive and relatable writer. He grapples with many of the same trials of social life that we all face, trials that became significantly more challenging in recent history. As a character in this memoir, he is not so much rounded in the literary sense — deep, complex and many-faceted — as he is jagged. The conflicts and quirks that other writers might edit out are on candid display in this book. It is well worth spending a few hours of quality solitude with it.

Techno optimism for 2024

Some intriguing stuff from Noah Smith.

Robot World is coming

The Jetsons focused on robots doing housework; they knew that this would be one of the technological innovations that would have the most immediate and unambiguously positive impact on Americans’ quality of life — especially women. …It’s also no coincidence that the first robot that achieved widespread success in the consumer market was the humble Roomba, a disc-shaped automatic vacuum cleaner. But most household chores — washing dishes, doing laundry, and so on — have remained too difficult for robots.

That may now be changing. A Stanford/Google team recently released demo video of its new robot, the Mobile ALOHA, which does household tasks:

Basically, you walk the robot through the tasks about 50 times, and then it can do them itself from then on. There are many other similar multipurpose robot servants in the works. Here’s one being created at NYU, here’s one from Israel, here’s one from Dyson, and here’s yet another from Google. I have no idea who’s going to get there first, but I’m increasingly confident that someone’s going to get there soonish.

The Decade of the Battery powers onward

One technology that I’m consistently hyper-optimistic about is batteries. This is because batteries represent something humanity has never really had before — a way to store a large amount of energy and carry it around. he most amazing thing about batteries is that the fundamental underlying technology is far from mature. Two huge innovations are just now making it to the commercialization stage: sodium-ion batteries and solid-state batteries.

Solid-state batteries are just better in every way than the batteries we use now — they’re lighter, smaller, stronger, and safer, they have greater range, they recharge more quickly, and they’re better for the environment. Toyota is going to begin selling cars with solid-state batteries soon; we’ll see how that goes, but my guess is that someone will commercialize solid-state batteries successfully within the decade.

Sodium-ion batteries, meanwhile, have a lot of performance advantages and use a lot fewer scarce metals than lithium-ion batteries. Chinese companies are now rolling them out for grid storage and possibly for EVs.

So as amazing as the battery revolution is right now, it’s just getting started.

Biotech is still booming

We usually think of biotech as distinct from innovation in electrical and mechanical applications, but the two are beginning to merge. Computation is essential to modern drug discovery and chemistry in general, and AI looks like it’ll be another important tool. Meanwhile, biological experimentation is increasingly making use of robots in the lab.

But the biotech revolution that’s unfolding right now isn’t just downstream of those other technologies — it’s the result of decades of massive work and deep-pocketed investment that’s now coming to fruition.

MRNA vaccines, the heroes of the Covid pandemic, are now being applied to a ton of other diseases. A new mRNA vaccine for malaria promises to help conquer humanity’s most deadly chronic illness. And a new mRNA vaccine for pancreatic cancer — which you actually take as a therapy after you’re diagnosed, not before — promises to save a lot of lives from one of the deadliest cancers. Other cancers are probably also treatable this way.

Another technology that’s just now coming to fruition is genetic engineering, especially via CRISPR. The FDA just approved a drug that actually goes in and reengineers the cells in a living human body to treat sickle cell anemia. Other such drugs are in the pipeline. Genetic engineering is also proving useful for modifying bacteria and other organisms for useful purposes, such as producing fuel or fighting cancer. Of course all of this is in addition to the potential for reengineering the human species itself, but that’s still on the horizon.

A third major area of technology whose potential is still on the horizon, but could be realized in the near future, is synthetic biology. This year, scientists synthesized the DNA to make an artificial yeast cell. Synthetic biology could eventually be used to create all kinds of custom-built organisms to do various jobs.

I should also give a shout-out to my friends at the company Loyal, who are close to getting FDA approval for the first commercial longevity drug for dogs. I hope the drugs are useful for pet rabbits, or that they make a rabbit version.

But the most important biotech discovery of the year sort of came out of left field. A class of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists, including Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro, long used to treat diabetes, has proven to be incredibly effective at helping people lose weight. The obesity epidemic is America’s #1 health problem, and is spreading to the rest of the world. These drugs are the first really effective pharmaceutical approach to combatting that epidemic.

And on top of that, one of the ways that these drugs treat obesity — basically by reducing food cravings — also makes them useful against a variety of other addictive behavior, like alcoholism and smoking. This makes them potential game-changers for many of the ills that afflict advanced societies. Already, demand for the drugs has supercharged the economy of Denmark, home of the company that makes Ozempic and Wegovy, due to massive demand.

So anyway, the promise of biotech really seems to be coming to fruition this decade, in a variety of very awesome ways.

Brian Klaas on the odious Elise Stefanik

Who led the congressional sting on antisemitism

Every so often, human analogies fail me, and I must turn to the animal kingdom to describe our politics. This time, we meet the remora, sometimes known as the suckerfish—a marine creature that spends its life attaching itself to a larger, more powerful fish and feeding off its ectoparasites and loose flakes of skin for sustenance.

This helps the larger fish, perhaps, but the main beneficiary is the remora, as it leeches its lifeblood from the host, drifting through the seas without an independent thought of its own.

Elise Stefanik is a political remora.

You may not know who Elise Stefanik is, but she is, to me, the most disturbingly fascinating political creature in modern American politics. She embodies the descent of the Republican party from a flawed, but broadly democratic political movement, to one that is now avowedly anti-democratic, led by an authoritarian who incites political violence.

Stefanik won her seat in Congress in 2014, a 30-year-old from upstate New York who proclaimed big dreams of ushering in profound change. She cut her teeth in the George W. Bush White House before working on the Mitt Romney/Paul Ryan ticket in 2012. (Without whitewashing the record of those three flawed men, there is an enormous difference between Bush/Romney/Ryan and the Trumpian MAGA movement; the most important is that the former all believe in democracy while the latter do not).

In her first magazine profile as a Congresswoman, Stefanik spoke glowingly of the virtues of bipartisanship, vowing to work with Democrats who she saw as partners, not enemies. She spoke enthusiastically about the prospect of playing softball with New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a Democrat.

When asked about her priorities, Stefanik said this: “I strongly support equal pay for equal work for women, and talked about that a lot on the campaign trail. I also support the Violence Against Women Act, and want to be a strong voice for young women, even if that means breaking with the party.” In TIME magazine, her mentor, Paul Ryan, described her as “the future of hopeful, aspirational politics in America…She is thinking about the big picture when the crowd is scrambling to capitalize on the controversy of the day.”

During the Trump administration, Stefanik began to evolve, from Paul Ryan acolyte to Trump remora. On January 6th, 2021, Stefanik voted against certifying the 2020 election, an official attempt to subvert democracy and install the loser of an election into political power.

But there were still tiny—albeit almost imperceptible—glimmers of independent thought. After the violence at the Capitol ended, Stefanik said this:

“This has been a truly tragic day for America. Americans will always have the freedom of speech and the constitutional right to protest. But violence in any form is absolutely unacceptable. It is anti-American and must be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.”

Last weekend, however, her evolutionary journey neared its completion. Stefanik was confronted with a tape of those comments on NBC’s Meet the Press. She responded by distancing herself from her own words, saying that comment was taken out of context. And then, the bombshell:

“I have concerns about the treatment of January 6th hostages,” she said, referring to those who are serving jail time for their role in the Capitol attack.

The word choice was no accident: for months, Trump has been using the same rhetoric, referring to the people who violently attacked police officers while breaking into the chambers of Congress as “hostages, not prisoners.”

The words flaked from Trump’s mouth into Stefanik’s, completing her transformation from someone who presented herself as an independent, bipartisan moderate vowing to swim against the GOP current into a political remora enthusiastically sporting a red hat on her dorsal fin. It was an audition tape for vice president. “Pick me!” Stefanik seemed to plead, hoping to enjoy future sustenance offered by the loose orange skin flakes presented by her host.

Then, the pièce de résistance: Stefanik refused to promise that she would certify the 2024 presidential election, rightly raising fears that she was already plotting to overturn the next election—should Trump lose.

What happened to her? The answer helps explain the descent of the Republican Party into MAGA madness...

Nietzsche and Pascal

I was struck finding this passage in Pascal, and reminded of an early shot over the bow from Nietzsche which I quote immediately below:

Pascal

Let man then contemplate the whole of nature in her full and lofty majesty, let him turn his gaze away from the lowly objects around him; let him behold the dazzling light set like an eternal lamp to light up the universe, let him see the earth as a mere speck compared to the vast orbit described by this star, and let him marvel at finding this vast orbit itself to be no more than the tiniest point compared to that described by the stars revolving in the firmament. But if our eyes stop there, let our imagination proceed further; it will grow weary of conceiving things before nature tires of producing them. The whole visible world is only an imperceptible dot in nature’s ample bosom. No idea comes near it; it is no good inflating our conceptions beyond imaginable space, we only bring forth atoms compared to the reality of things. Nature is an infinite sphere whose centre is everywhere and circumference nowhere. In short it is the greatest perceptible mark of God’s omnipotence that our imagination should lose itself in that thought.

Let man, returning to himself, consider what he is in comparison with what exists; let him regard himself as lost, and from this little dungeon, in which he finds himself lodged, I mean the universe, let him learn to take the earth, its realms, its cities, its houses and himself at their proper value.

What is a man in the infinite?

But, to offer him another prodigy equally astounding, let him look into the tiniest things he knows. Let a mite show him in its minute body incomparably more minute parts, legs with joints, veins in its legs, blood in the veins, humours in the blood, drops in the humours, vapours in the drops: let him divide these things still further until he has exhausted his powers of imagination, and let the last thing he comes down to now be the subject of our discourse. He will perhaps think that this is the ultimate of minuteness in nature.

I want to show him a new abyss. I want to depict to him not only the visible universe, but all the conceivable immensity of nature enclosed in this miniature atom. Let him see there an infinity of universes, each with its firmament, its planets, its earth, in the same proportions as in the visible world, and on that earth animals, and finally mites, in which he will find again the same results as in the first; and finding the same thing yet again in the others without end or respite, he will be lost in such wonders, as astounding in their minuteness as the others in their amplitude. For who will not marvel that our body, a moment ago imperceptible in a universe, itself imperceptible in the bosom of the whole, should now be a colossus, a world, or rather a whole, compared to the nothingness beyond our reach? Anyone who considers himself in this way will be terrified at himself, and, seeing his mass, as given him by nature, supporting him between these two abysses of infinity and nothingness, will tremble at these marvels. I believe that with his curiosity changing into wonder he will be more disposed to contemplate them in silence than investigate them with presumption.

For, after all, what is man in nature? A nothing compared to the infinite, a whole compared to the nothing, a middle point between all and nothing, infinitely remote from an understanding of the extremes; the end of things and their principles are unattainably hidden from him in impenetrable secrecy.

Equally incapable of seeing the nothingness from which he emerges and the infinity in which he is engulfed.

What else can he do, then, but perceive some semblance of the middle of things, eternally hopeless of knowing either their principles or their end? All things have come out of nothingness and are carried onwards to infinity. Who can follow these astonishing processes? The author of these wonders understands them: no one else can.

Because they failed to contemplate these infinities, men have rashly undertaken to probe into nature as if there were some proportion between themselves and her.

Strangely enough they wanted to know the principles of things and go on from there to know everything, inspired by a presumption as infinite as their object. For there can be no doubt that such a plan could not be conceived without infinite presumption or a capacity as infinite as that of nature.

When we know better, we understand that, since nature has engraved her own image and that of her author on all things, they almost all share her double infinity. Thus we see that all the sciences are infinite in the range of their researches, for who can doubt that mathematics, for instance, has an infinity of infinities of propositions to expound? They are infinite also in the multiplicity and subtlety of their principles, for anyone can see that those which are supposed to be ultimate do not stand by themselves, but depend on others, which depend on others again, and thus never allow of any finality.

But we treat as ultimate those which seem so to our reason, as in material things we call a point indivisible when our senses can perceive nothing beyond it, although by its nature it is infinitely divisible.

Of these two infinites of science, that of greatness is much more obvious, and that is why it has occurred to few people to claim that they know everything. ‘I am going to speak about everything,’ Democritus used to say.

But the infinitely small is much harder to see. The philosophers have much more readily claimed to have reached it, and that is where they have all tripped up. This is the origin of such familiar titles as Of the principles of things, Of the principles of philosophy,1 and the like, which are really as pretentious, though they do not look it, as this blatant one: Of all that can be known.2

We naturally believe we are more capable of reaching the centre of things than of embracing their circumference, and the visible extent of the world is visibly greater than we. But since we in our turn are greater than small things, we think we are more capable of mastering them, and yet it takes no less capacity to reach nothingness than the whole. In either case it takes an infinite capacity, and it seems to me that anyone who had understood the ultimate principles of things might also succeed in knowing infinity. One depends on the other, and one leads to the other. These extremes touch and join by going in opposite directions, and they meet in God and God alone.

Let us then realize our limitations. We are something and we are not everything. Such being as we have conceals from us the knowledge of first principles, which arise from nothingness, and the smallness of our being hides infinity from our sight.

Our intelligence occupies the same rank in the order of intellect as our body in the whole range of nature.

Limited in every respect, we find this intermediate state between two extremes reflected in all our faculties. Our senses can perceive nothing extreme; too much noise deafens us, too much light dazzles; when we are too far or too close we cannot see properly; an argument is obscured by being too long or too short; too much truth bewilders us. I know people who cannot understand that 4 from o leaves o. First principles are too obvious for us; too much pleasure causes discomfort; too much harmony in music is displeasing; too much kindness annoys us: we want to be able to pay back the debt with something over. Kindness is welcome to the extent that it seems the debt can be paid back. When it goes too far gratitude turns into hatred.1

We feel neither extreme heat nor extreme cold. Qualities carried to excess are bad for us and cannot be perceived; we no longer feel them, we suffer them. Excessive youth and excessive age impair thought; so do too much and too little learning.

In a word, extremes are as it they did not exist for us nor we for them; they escape us or we escape them.

Such is our true state. That is what makes us incapable of certain knowledge or absolute ignorance. We are floating in a medium of vast extent, always drifting uncertainly, blown to and fro; whenever we think we have a fixed point to which we can cling and make fast, it shifts and leaves us behind; if we follow it, it eludes our grasp, slips away, and flees eternally before us. Nothing stands still for us. This is our natural state and yet the state most contrary to our inclinations. We burn with desire to find a firm footing, an ultimate, lasting base on which to build a tower rising up to infinity, but our whole foundation cracks and the earth opens up into the depth of the abyss.

Let us then seek neither assurance nor stability; our reason is always deceived by the inconsistency of appearances; nothing can fix the finite between the two infinites which enclose and evade it.

Once that is clearly understood, I think that each of us can stay quietly in the state in which nature has placed him. Since the middle station allotted to us is always far from the extremes, what does it matter if someone else has a slightly better understanding of things? If he has, and if he takes them a little further, is he not still infinitely remote from the goal? Is not our span of life equally infinitesimal in eternity, even if it is extended by ten years?

In the perspective of these infinites, all finites are equal and I see no reason to settle our imagination on one rather than another. Merely comparing ourselves with the finite is painful.

If man studied himself, he would see how incapable he is of going further. How could a part possibly know the whole? But perhaps he will aspire to know at least the parts to which he bears some proportion. But the parts of the world are all so related and linked together that I think it is impossible to know one without the other and without the whole.

There is, for example, a relationship between man and all he knows. He needs space to contain him, time to exist in, motion to be alive, elements to constitute him, warmth and food for nourishment, air to breathe. He sees light, he feels bodies, everything in short is related to him. To understand man therefore one must know why he needs air to live, and to understand air one must know how it comes to be thus related to the life of man. etc.

Flame cannot exist without air, so, to know one, one must know the other.

Thus, since all things are both caused or causing, assisted and assisting, mediate and immediate, providing mutual support in a chain linking together naturally and imperceptibly the most distant and different things, I consider it as impossible to know the parts without knowing the whole as to know the whole without knowing the individual parts.

The eternity of things in themselves or in God must still amaze our brief span of life.

The fixed and constant immobility of nature, compared to the continual changes going on in us, must produce the same effect.

And what makes our inability to know things absolute is that they are simple in themselves, while we are composed of two opposing natures of different kinds, soul and body. For it is impossible for the part of us which reasons to be anything but spiritual, and even if it were claimed that we are simply corporeal, that would still more preclude us from knowing things, since there is nothing so inconceivable as the idea that matter knows itself. We cannot possibly know how it could know itself.

Thus, if we are simply material, we can know nothing at all, and, if we are composed of mind and matter, we cannot have perfect knowledge of things which are simply spiritual or corporeal.

That is why nearly all philosophers confuse their ideas of things, and speak spiritually of corporeal things and corporeally of spiritual ones, for they boldly assert that bodies tend to fall, that they aspire towards their centre, that they flee from destruction, that they fear a void, that they have inclinations, sympathies, antipathies, all things pertaining only to things spiritual. And when they speak of minds, they consider them as being in a place, and attribute to them movement from one place to another, which are things pertaining only to bodies.

Instead of receiving ideas of these things in their purity, we colour them with our qualities and stamp our own composite being on all the simple things we contemplate.

Who would not think, to see us compounding everything of mind and matter, that such a mixture is perfectly intelligible to us? Yet this is the thing we understand least; man is to himself the greatest prodigy in nature, for he cannot conceive what body is, and still less what mind is, and least of all how a body can be joined to a mind. This is his supreme difficulty, and yet it is his very being. The way in which minds are attached to bodies is beyond man’s understanding, and yet this is what man is.

Finally to complete the proof of our weakness, I shall end with these two considerations. Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms to crush him: a vapour, a drop of water is enough to kill him. But even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.

Thus all our dignity consists in thought. It is on thought that we must depend for our recovery, not on space and time, which we could never fill. Let us then strive to think well; that is the basic principle of morality. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread.

Nietzsche

In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest and most mendacious minute of “world history”—yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die.

One might invent such a fable and still not have illustrated sufficiently how wretched, how shadowy and flighty, how aimless and arbitrary, the human intellect appears in nature. . . . For this intellect has no further mission that would lead beyond human life. It is human, rather, and only its owner and producer gives it such importance, as if the world pivoted around it. But if we could communicate with the mosquito, then we would learn that he floats through the air with the same self-importance, feeling within itself the flying center of the world. There is nothing in nature so despicable or insignificant that it cannot immediately be blown up like a bag by a slight breath of this power of knowledge . . . .

It is strange that this should be the effect of the intellect, for after all it was given only as an aid to the most unfortunate, most delicate, most evanescent beings in order to hold them for a minute in existence, from which otherwise, without this gift, they would have every reason to flee . . . That haughtiness which goes with knowledge and feeling, which shrouds the eyes and senses of man in a blinding fog, therefore deceives him about the value of existence by carrying in itself the most flattering evaluation of knowledge itself. Its most universal effect is deception. . . .

The intellect, as a means for the preservation of the individual, unfolds its chief powers in simulation . . . In man this art of simulation reaches its peak: here deception, flattering, lying and cheating, talking behind the back, posing, living in borrowed splendor, being masked, the disguise of convention, acting a role before others and before oneself—in short, the constant fluttering around the single flame of vanity is so much the rule and the law that almost nothing is more incomprehensible than how an honest and pure urge for truth could make its appearance among men. They are deeply immersed in illusions and dream images . . .

What, indeed, does man know of himself! Can he even once perceive himself completely, laid out as if in an illuminated glass case? Does not nature keep much the most from him, even about his body, to spellbind and confine him in a proud, deceptive consciousness, far from the coils of the intestines, the quick current of the blood stream, and the involved tremors of the fibers? She threw away the key; and woe to the calamitous curiosity which might peer just once through a crack in the chamber of consciousness and look down, and sense that man rests upon the merciless, the greedy, the insatiable, the murderous, in the indifference of his ignorance—hanging in dreams, as it were, upon the back of a tiger. In view of this, whence in all the world comes the urge for truth?

It is interesting to watch Putin turn to a totalising imperialism because once he got to the top there was nothing else left to do --- low affect psychopaths to a T I suspect

If you are finding "fine things" in hacks like Rufo and outright racists like Hanania, you have a big problem. Denying the existence of systemic racism in the US is an absurdity, which is why the Republicans have been trying to prohibit mention of the issue. That doesn't negate the importance of inequality (economic) class, gender and so on, all of which are being equally suppressed by the anti-wokes