The post COVID economy, the war and the courage to keep going

Most of what follows is on the war in Ukraine which continues to take up a lot of my headspace. But before I get on to that, in case you’re in Melbourne and would like to come …

Panel on the post COVID, post Ukraine world: This Sunday in Canterbury

A panel organised by Julian Burnside with Angela Jackson, Stephen Mayne and me.

Let others know! Let them know NOW!

Branko Milanovic on Russia’s economic prospects

Terrific pieces — and easily comprehended by non-economists. Highly recommended.

The short-run

From the conclusion:

The coming years of Putin’s rule will thus look very much like the worst years of Yeltsin’s rule. Putin was brought out of the deep shadows with the idea that he would protect the gains of Yeltsin’s family and the oligarchs while reimposing some degree of internal stability. In his first two terms, he was successful in doing that. But at the end (or whatever the current point it is) of his reign, he brought all the original diseases back and made them in some sense worse because his policies stuck the country in an impasse and thus closed off all the venues of change.

Russia's long-term economic prospects

Difficulties of import substitution and delocalization

A fascinating discussion of the difficulties of ‘starting again’ behind a wall of sanctions.

In 1970s, USSR was certainly ahead of Brazil, and even of ahead of Europe that began developing Airbus only in 1972. But that industry was destroyed during the transition, and the only remnant of it is Sukhoi Superjet that is currently used by several Russian airlines but has not been sold (almost) anywhere else in the world. In contrast, Brazilian Embraer operates in 60 countries.

Doing import substitutions in conditions where both the base of such substitution will have to be recreated and then new industries created without much (or any) input through investments from the more advanced parts of the world is almost impossible. This is the problem that China was able to solve only after a dramatic foreign policy shift in the mid-1970s. But that option, by definition, will be unavailable to Russia …

Since [skilled labour] will not find adequate use and adequate pay in Russia it will tend to emigrate, thus further shrinking the available number of highly skilled workers. It is not impossible that Russia might return to the Soviet policy of not allowing free migration—now under the pressure of economic factors. It was precisely the outflow of highly qualified workers that led East Germany to erect the Berlin Wall.

Courage!

Russia’s ideology

As with last week, I haven’t been able to stay away from articles trying to explain what ideology we’re dealing with.

The real Russian elite (and its ideology)

To repurpose something Solzhenitzen reminded us of, what’s worse than an evil maniac or a cadre of them? The same thing with an ideology. In this excellent piece from the world’s best newspaper — the FT who are taking some of their best coverage of Ukraine out from behind their paywall — Anatol Lieven explains the ideological elite behind Putinism — the siloviki.

In describing Vladimir Putin and his inner circle, I have often thought of a remark by John Maynard Keynes about Georges Clemenceau, French prime minister during the first world war: that he was an utterly disillusioned individual who “had one illusion — France”. Something similar could be said of Russia’s governing elite, and helps to explain the appallingly risky collective gamble they have taken by invading Ukraine.

The siloviki have been accurately portrayed as deeply corrupt — but their corruption has special features. Patriotism is their ideology and the self-justification for their immense wealth. … The siloviki are naturally attached to the idea of public order, an order that guarantees their own power and property, but which they also believe is essential to prevent Russia falling back into the chaos of the 1990s and the Russian revolution and civil war. The disaster of the 1990s, in their view, embraced not just a catastrophic decline of the state and economy but socially destructive moral anarchy — and their reaction has been not unlike that of conservative American society to the 1960s or conservative German society to the 1920s.

Putin was the first Alt-President: he seeks to make Russia great again

A 2017 essay on the bankruptcy and nuttiness of Putin’s Eurasionist vision. Subsequent events show how prophetic it was — though it also argues that Putin would probably adopt a more cautious approach than he has:

Between now and the middle of the next decade, the arc of Russian foreign policy will be determined by Vladimir Putin’s attempt to establish his legacy as a figure of grand history. Much like Ivan III, Putin is set on bringing Russia back to its glory days before the collapse of the 1990s. Putin’s vision is not to build a new Soviet Union, but rather a new Russia that adapts much of its feudal past to the present. Putin is reimagining the authoritarian state at home, and the vassal-state-abroad structure of Imperial Russia. The motivation behind such a neofeudal world order is Eurasianism: a pan-nationalist movement that puts Moscow at the center of a countermovement to the American-dominated post-Cold War order.

Putin wants to establish a norm among the international order that supports authoritarian states against Western intervention – a core part of Eurasianist ideology.

Taken together, this constellation of beliefs may lead Moscow to pursue policies in places like Syria and Ukraine for the sake of principle, and oftentimes against a simple hard-power calculation of what the West perceives Russia’s national interests to be.

Putin's strength is superficial. Beneath the surface, Russia is a declining power, and at some level, Putin acts from a position of deep national insecurity. Thus, he has an incentive to overplay his hands and push beyond the expected.

Finally, the new administration should take special care to remember that Putin is starting the process of establishing his legacy and that he has every incentive to be more aggressive as he gets older.

Putin's Challenge To The American Right

Andrew Sullivan on how Ukraine has “exposed the flimsiness of post-liberalism” and why “reactionism is not really a politics; it’s a mood”.

The West wasn’t supposed to unite this expeditiously; the EU wasn’t expected to find a new and confident voice; Russia’s access to global finance wasn’t supposed to be severed overnight; and a senile American president wasn’t supposed to corral a massive coalition to marginalize and isolate Russia on the global stage. But it all did. David Frum had a nice line on this: “Everything the [far right] wanted to perceive as decadent and weak has proven strong and brave; everything they wanted to represent as fearsome and powerful has revealed itself as brutal and stupid.”

Michael Millerman on Alexander Dugin (made before the war)

Putin believes he is defending Orthodox Christianity from the godless West

The former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams makes some interesting points and makes them so melifluously that you wonder if you should join him for tea after the service. (And anyway, it enables me to post the scrumptious picture above!). More to the point, Russia is pursuing its strategy of disaster and death all round to keep the world safe from gay pride marches — who knew?

We might do worse than ask why non-Western cultures so fear being sucked into what they consider a moral vacuum. If all they see is a series of reactive demands for emancipation acted out against a backdrop of consumerism and obsession with material growth, the suspicion and hostility is a bit more intelligible. What do we in the shrinking “liberal” world think emancipation is for? Perhaps it is for the liberation of all individuals to collaborate in a positive social project, in a society of sustainable and fair distribution of goods. Perhaps it is for the construction of a social order in which our interdependence, national and international, is more fully acknowledged.

Solidarity with Ukraine involves sanctions that will cost us as well as Russians – decisions that will affect our reliance on oil and gas and open our doors to more refugees. If we are willing to accept these consequences for the sake of a positive vision of interdependence and justice, we shall have a more compelling narrative to oppose the dramatic, even apocalyptic, myths arising elsewhere in the world.

Unwelcome neighbours, after all, tend not simply to disappear; in which case, we must work out how we live respectfully with them. One thing that might be said in response to Patriarch Kirill is that neighbours have to be loved, not terrorised into resentful silence – a matter on which the God first acknowledged in Kyiv in 988 had a good deal to say.

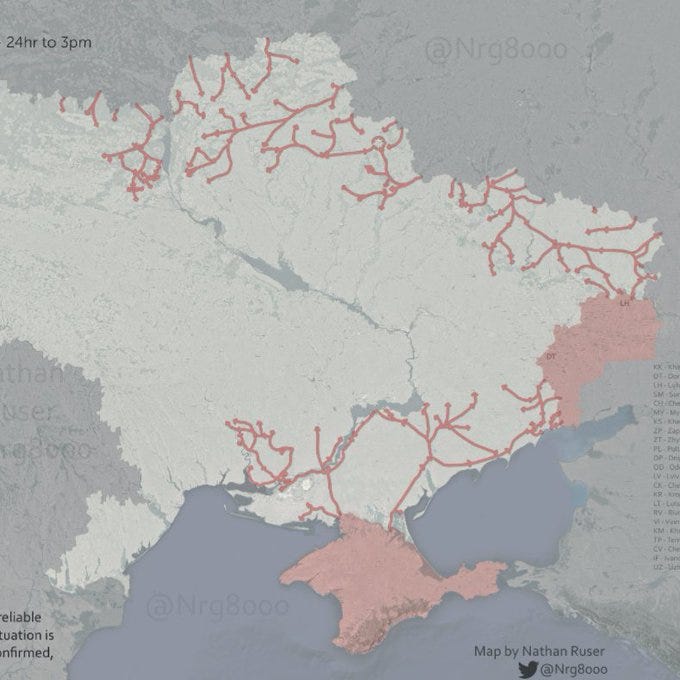

Russia's Logistical Nightmare Will Get Worse

Notice how the Russian advance stops at around the same distance from its borders throughout Ukraine. An excellent, simple piece on the logistics shaped brick wall the Russians seem to have slammed into.

Martin Wolf on Russia’s war remaking the world

A new world is being born. The hope for peaceful relations is fading. Instead, we have Russia’s war on Ukraine, threats of nuclear Armageddon, a mobilised west, an alliance of autocracies, unprecedented economic sanctions and a huge energy and food shock. No one knows what will happen. But we do know this looks to be a disaster. …

After the battle of Austerlitz in 1805, William Pitt the Younger said, presciently: “Roll up the map [of Europe]; it will not be needed these 10 years.” Russia’s war on Ukraine has similarly transformed the map of our world. A prolonged bout of stagflation seems certain, with large potential effects on financial markets. In the long term, the emergence of two blocs with deep splits between them is likely, as is an accelerating reversal of globalisation and sacrifice of business interests to geopolitics. Even nuclear war is, alas, conceivable. Pray for a miracle in Moscow. Without it, the road ahead will be long and hard.

The Pathologies of Imperialism

A good article in Quillette drawing the parallels between the Suez Crisis of 1956 and today’s ‘Ukraine Crisis’. The parallel is that in each case the aggressor (in 1956 the UK and France with the help of Israel) expected to achieve their objective quickly. The UK expected the Americans would be pleased with their seizing Suez, but after a botched operation the US were decidedly displeased and the UK had no choice but to back down with the withdrawal of American favour (including economic favour at a time of US dollar shortages).

China is much more interested in a multilateral world. Despite attempts to move to a “Dual Circulation Strategy” after Covid as a way of reducing dependence on outside supply chains, China is more dependent on world trade than ever. There is no interest in seeing an escalation of already existing trade wars. Ukraine is an important trade partner of China, and also a vital link in its engagement with Europe. Second, the Ukraine conflict has implications for Taiwan. A quick and successful Russian action leading to the reorientation of Ukraine would probably have had implications for the People’s Republic’s possibility of applying pressure on Taiwan (and limiting the capacity of the US to provide an answer). But breaking up Ukraine is counterproductive for the PRC. China is utterly committed to its interpretation of the territorial integrity of states for a very particular reason: a recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk as breakaway states would imply that there would be nothing wrong with recognizing the independence of Taiwan as a breakaway state.

It is deeply frustrating for the US and for Europeans to stand by with only limited assistance to a country that is being torn apart and destroyed. But it is also clear that the threat of nuclear war means that there can be no direct military assistance, no NATO forces in Ukraine, and no no-fly zone. Washington, London, Paris, Berlin all need Beijing in dealing with Russia. The only figure who can authoritatively tell Putin that he has to stop is President Xi. Like President Eisenhower dealing with his old friends in the “Special Relationship,” Xi may find himself with the duty of telling the “no limits” “best friend” that now is the time to stop. That is the responsibility, however uncomfortable, of being a counsellor in the process of imperial decline.

Why are we so het up about Ukraine (but not Syria and other wars)?

If you’re like me, you’re wondering this about your own reaction.

MSNBC’s Joy Reid thinks the West’s galvanizing response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is unfair. “Let’s face it,” she said on March 8th, “the world is paying attention because this is happening in Europe. If this was happening anywhere else, would we see the same outpouring of support and compassion?”

Is it racism (considered broadly to include ‘ethnicism’ — discrimination according to perceived difference)? I think the answer is ‘yes’. We’re like that us humangoes. As Adam Smith noted, we are much more moved by the experiences of those we feel closer to.

Taxes as sanctions

Ricardo Hausmann, a very good Venezuelan economist at Harvard has proposed that a tax on Russian oil would meet that elusive goal of imposing large costs on the sanctioned country with minimal costs on the sanctioning country. Why? Because demand is elastic (buyers will go elsewhere for a very small price change whereas supply will continue (because the alternative prevents one earning any revenue at all). Hausmann wrote this piece when he doubted the strength of Western sanctions which have proven much stronger than expected, but the idea is still worth keeping in mind.

A punitive global tax on Russian oil – at a rate of, say, 90%, or $90 per barrel – could extract and transfer to the world some $300 billion per year from Putin’s war chest, or about 20% of Russia’s 2021 GDP. And it would be infinitely more convenient than an embargo on Russian oil, which would enrich other producers and impoverish consumers.

It’s time to ask: what would a Ukraine-Russia peace deal look like?

The great Ukrainian culture

The cultural contradictions of shamelessness

Always good to know where people stand …

Yesterday’s solutions become today’s problems

The very busy Ezra Klein has been busy writing on the ways in which the left has contributed to the inefficiencies of government — by doing things that made plenty of sense when they did them, but which no longer do.

Marxism as a religion: a personal recollection

It Isn't Just Asian Immigrants Who Thrive in the U.S.

It’s impolite in some circles to mention it — complicating as it is for the power of the systemic racism narrative — but some of the immigrants who do the best are Africans. Like Nigerians whose culture targets achievement and education.

Alt-centre: the podcast

In this video Peyton Bowman and I explore aspects of the blog post I led off with last week "Will you join me in the alt-centre?". I initially coined the term “alt-centre” light-heartedly, but, like many such things, having put it up there, I think it might be about something real.

An earlier iteration of my centrism is here. But that was then.

Now I’d say, how about a fusion of Alasdair MacIntyre, James Burnham and George Orwell together with the idea that outputs from modern academia are mostly useless?

And, in this discussion, as I do in my post, we explore James Burnham's argument that over nine-tenths of political discussion — from the heights of political theory right down to discussions in the street is fatally infected with wish fulfilment, rather than a proper engagement with the problems of the world and what we can practically do about them.

I illustrate this by referring to the much relied on the distinction between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome noting that neither actually exists in the world. They're abstractions. More to the point, if you give one generation equality of opportunity, its children will not have equality of opportunity because the children of people who've not done well will start disadvantaged. And yet the concept is bandied about in political discussion as if it were far more determinative than it is.

We go on to discuss a range of questions such as the role that our values — and our wishes — should play in political discussion and the way in which various practices associated with wokedom, often have more to do with organisations protecting themselves from risk than they do with helping address difficult issues. As such, when organisations regulate conduct to take these ideas into account, they often do so to make them disappear rather than to engage with them. These ideas are explored further in this blog post. The audio podcast can be downloaded here.

From the department of oops …