The borg comes for the economics Nobel

A friend and colleague gave me the news that Daren Acemoglu had won the Economics Nobel (not really a Nobel, but a Nobel ‘branded’ prize funded not from Alfred Nobel’s estate but by the Swedish central bank — incidentally the oldest central bank in the world.) I told him I didn’t think much of Acemoglu. When I read his stuff I’m in sympathy with it ideologically, but it seems analytically loose and tendentious. I could try to justify that statement, but it would be hard work.

Somehow Acemoglu’s theory reminds me of Rory Stewart telling the story of officials describing their goal for Afghanistan as being “a gender sensitive multiethnic centralized state based on democracy human rights the rule of law” and commenting that it sounded very impressive and analytical until he realised that all they were doing was describing what wasn’t there. It’s something that poses as an insight and suggests cause and effect, but is in fact little more than a description of things.

Fortunately, an economist of proven terrificness has done the hard work for me. He also makes it clear how much this year’s Nobel reinforces the increasingly monocultural academic practice of judging research quality not on whether it’s right or not but whether it gets other academics to cite it. (Did I mention that this is a disastrous turn? Oh yes, I did. I still intend to sigh and look long suffering.)

Long-time readers will know that I don’t think much of Nobel Prizes in general. They elevate individual contributions way too much, when most big discoveries are big group efforts and/or series of small incremental additions. This creates a “cult of genius” that doesn’t reflect how science really works, and creates too large of a status distinction between prizewinners and others.

On top of that, I also have some additional criticisms of the Econ Nobel.1 The science prizes rely very heavily on external validity to determine who gets the prize — your theory or your invention has to work, basically. If it doesn’t, you can be the biggest genius in the world, but you’ll never get a Nobel. The physicist Ed Witten won a Fields Medal, which is even harder to get than a Nobel, for the math he invented for string theory. But he’ll almost certainly never get a Physics Nobel, because string theory can’t be empirically tested.

The Econ Nobel is different. Traditionally, it’s given to economists whose ideas are most influential within the economics profession. If a whole bunch of other economists do research that follows up on your research, or which uses theoretical or empirical techniques you pioneered, you get an Econ Nobel. Your theory doesn’t have to be validated, your specific empirical findings can already have been overturned by the time the prize is awarded, but if you were influential, you get the prize.

You could argue that this is appropriate for what Thomas Kuhn would call a “pre-paradigmatic” science — a field that’s still looking for a set of basic concepts and tools. But it’s been 55 years since they started giving the prize, and that seems like an awfully long time for a field to still be tooling up. Meanwhile, making “influence within the economics profession” the criterion for successful research seems a little too much like a popularity contest. It’s how you end up with prizes like the one in 2004, which was given to some macroeconomic theorists whose theory said that recessions are caused by technological slowdowns and that mass unemployment is a voluntary vacation.

In recent years, that looked like it might be changing. Often, the prize was given to empirical economists associated with the so-called “credibility revolution” — basically, quasi-experiments. Those cases include Goldin in 2023, Card/Angrist/Imbens in 2021, and Banerjee/Duflo/Kremer in 2019. And when it was given to theorists, they tended to be game theorists whose theories are very predictive of real-world outcomes — Milgrom/Wilson in 2020, Hart/Holmstrom in 2016, Tirole in 2014, and Roth/Shapley in 2012. Even when the prize was given to macro — a field where validity is much harder to establish — it was given to economists whose theories have seen immediate application to pressing problems of the day, such as Bernanke/Diamond/Dybvig in 2022 and Nordhaus in 2018.

In other words, the recent Nobels have made it seem like economics might be becoming more like a natural science, where practical applications and external validity are the ultimate arbiter of the value of research, rather than cultural influence within the economics profession. But this year’s prize seems like a step away from that, and back toward the sort of big-think that used to be more popular in the prize’s early years. …

Alex Tabarrok tells the tale:

I think of Daron Acemoglu (GS) as the Wilt Chamberlin of economics, an absolute monster of productivity who racks up the papers and the citations at nearly unprecedented rates. According to Google Scholar he has 247,440 citations and an H-index of 175, which means 175 papers each with more than 175 citations. Pause on that for a moment. Daron got his PhD in 1992 so that’s over 5 papers per year which would be tremendous by itself–but we are talking 5 path-breaking, highly-cited papers per year plus many others!…In his overview of Daron’s work for the John Bates Clark medal Robert Shimer wrote “he can write faster than I can digest his research.” I believe that is true for the profession as a whole. We are all catching-up to Daron Acemoglu.

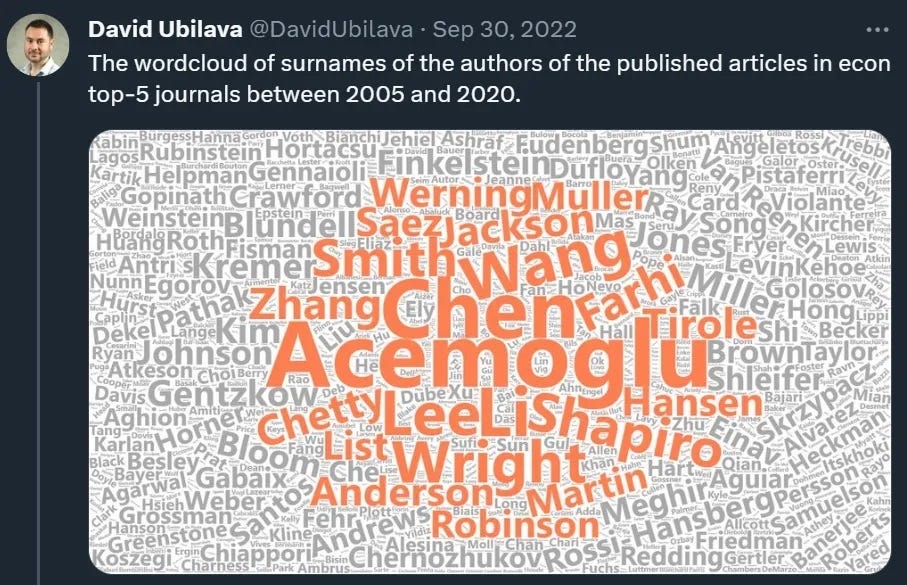

In fact, this is all you really have to see to get the point:

In physics, as I mentioned, it would easily be possible for a researcher this accomplished to never get a Nobel. In economics it is not possible.2 And when Acemoglu got his Nobel, it was always going to be officially awarded for his single most influential area of research. That would be his research on institutions and economic development.

Richard Dawkins, Venice and the electoral college

From The UK Spectator. Richard Dawkins has been on his book tour of the US and gloms onto the original purpose of the Electoral College. It was designed to produce a chain of trust and authority that ran through representatives chosen by the people (or at least those sufficiently propertied in 1789) but which also captured the wisdom of their representatives.

It’s intriguing that Dawkins likens the Electoral College to a papal conclave because the model was closer to Venice about which John Adams wrote at length. Venice used a very nifty system which I call ‘bottom-up meritocracy’. Governed by a Grand Council of between 1,000-3,000 nobles throughout its best 500 years, Senators and other senior officeholders were elected from the Grand Council, but not in an open election. 30 odd members of the Council were chosen at random and then immediately popped into an enclave from whence they could not escape until they had voted for said officeholders. To prevent threats and bribery electors had a secret ballot. Anyway, this seemed like a great idea to the founding fathers. It was, but with electors being effectively chosen by popular vote, it was quickly captured by party politics. And that was that.

And – praise be – a population of 300 million Americans has managed to raise one presidential candidate who is not a convicted felon awaiting sentence. No, my problem with American elections – and it viscerally distresses me every four years – is the affront to democracy called the electoral college. I’ve done the maths. The electoral college can hand you the presidency even if your opponent receives three-quarters of the popular vote. Of course that’s a hypothetical extreme. The familiar reality is that campaigns ignore all but a handful of ‘swing’ states. A genuine electoral college, however, could work rather well. Voters in every state would elect respected citizens to meet in conclave to find a president – like a university search committee or the College of Cardinals. They’d headhunt the best in the land, interview them, study their publications and speeches, exhaustively vet them, and finally after a secret ballot announce the verdict in a puff of white smoke. Perhaps the founding fathers had something like that in mind. If so, the rot set in when electoral college members became pledged to a particular candidate, and each state’s quota voted as a monolithic bloc, no matter how slender the state’s popular vote margin. Alas, my ‘search committee’ ideal would never fly: too vulnerable to corruption. And replacing the present ludicrously undemocratic electoral college by a sensible plebiscite needs a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, plus approval by three-quarters of the states – a near unattainable goal because of vested interests.

My cattle farming mum would have liked this

I miss my mum.

Bette Midler retweets a funny tweet

Criticism or the expression of a mood?

Henry Oliver let’s fly at the New York Times critic who is not a critic. I offered my own take on some of the issues from a very different perspective — which I’ll extract beneath the piece.

I don’t know what to call this piece written by the Times’ “critic at large”, but it certainly isn’t criticism. It’s the fashionable expression of a mood, a higher clickbait.

The premise is that as the Nobel Prize is about to be announced—the “global arbiter of literary greatness”— we need to recognise that greatness and popularity are not, and cannot, be the same.

Greatness is not the same as popularity. It may even be the opposite of popularity. Great books are by definition not the books you read for pleasure.

This would come as a surprise to the masses of people who read (and still read) the great nineteenth century novels for pleasure. It would be a surprise to those people who turned Shakespeare into a bestseller, too.

Millions of people have read Kazuo Ishiguro for pleasure, a recent Nobel Laureate, and that is true of many other modern laureates like J.M Coetzee, Seamus Heaney, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro. That is only to mention some of the English language winners. …

The great books are the ones you’re supposed to feel bad about not having read.

This is the sort of thing people say in chit-chat, not what we need to go the New York Times for. Come on! This is how we define Montaigne and Plato? If a major critic at a major newspaper thinks that these are adequate ways to define quality in the humanities, then what on earth does he think is the point of his job? Ah, yes, to make lists.

Critics make lists; newspapers conduct polls; algorithms and social platforms serve up carefully curated consumer advice.

Nobody invests any of these with too much authority. If you don’t like what’s on my list, you can make your own. How we evaluate the things we enjoy thus feels data-driven, democratic and subjective in the ways that institutions like the Nobel don’t.

Lists are good.Lists are good. But that is not what a critic is. The abnegation of taste at our cultural institutions is precisely the problem. …

The critic’s job to be knowledgeable, to understand how a work of art is, to be able to place it and compare it, to be able to say how it functions, to bring to light some of its qualities that readers (or watchers, or listeners) can find their way through the swell of production to the shore of pleasure. A critic turns opinion into knowledge (Johnson). They show us how a work of art is what it is (Sontag).

In doing this, the critic will inevitably make judgements. There has been, for several generations now, a reaction against judgement, against the critic as ordainer of the best and the worst, the good and the ugly. It is a lower form of criticism not just because it is arrogant and absurd for a critic to think they are capable of making such pronouncements, but because it too often precludes the real work of explication, explanation, understanding, and sympathy.

All [the NYT author] A.O. Scott is really saying is that winning a Nobel Prize isn’t a guarantee of greatness and feels out of step with the times. A more obvious cultural statement is it hard to conceive. But this has been spun out into a long thesis that tells Times readers that “the confusing swirl of emotions aroused annually by the literature Nobel” means greatness is a thing of the past.

At a time when reading is in decline and the value of literature is everywhere ignored or overlooked, instead of promoting this easy philistinism, we might hope that the Times would offer us something more like actual criticism. That is, the work of knowing about art, rather than opining about the culture surrounding art, and helping it, in Merve Emre’s words, “pass gracefully from my hand to another’s, from the present into the future.”

Whoever wins the Nobel, we would all be better served by more actual criticism than any more of these platitudes that what is popular has taken over from what is great.

Pretty huh?

My comment on Henry’s criticism of criticism above

I've stumbled into this issue — or something close to the issue you raise — in a number of contexts. The first is thinking about academic economics. In the academy, the role of critic is regarded as subordinate to the 'real thing'. Well in literature it's certainly the case that Shakespeare trumps any Shakespeare critic, but in academia I don't think that's true. So the skills of critical awareness have become more or less completely atrophied. As I tried to explain in this piece, the result is that really intelligent people end up with a discipline that is little more than a jumble of intellectual artefacts. No-one gets any brownie points for the hard labour of working out the limits of their application — or to use the word you used — for showing superior *judgement* in the way they use the intellectual resources available. I note when Mary Midgley describes herself as a critic rather than as a philosopher. I think that's right and that shows how much similar atrophy of judgement has occurred in philosophy.

The other thing it puts me in mind of is recently learning of Stafford Beer's management cybernetics via Dan Davies excellent primer The Unaccountability Machine. As I discussed with him in this podcast, disciplines like economics seem to be built without a 'System 4'. For the uninitiated, Systems 1-3 are parts of an organisation to do with day-to-day operations. Here's ChatGPT explaining System 4: "System 4 is responsible for ensuring that the organization can adapt and evolve over time by balancing day-to-day operations with future opportunities and threats."

System 4 can't function effectively without critical awareness.

Stewart Lee’s new show

Being a comedian is very hard. I don’t know any comedian who’s been much good until they’ve put in many years of grind. If you look at Stewart Lee’s early performances, you can see he’s being ambitious. After all it’s a pretty ambitious comedian who wants to make his comedy about him boring his audience. His last big show was great containing these belly laughs, but in this one he’s even more this boring, overly ironic and self-analytic character he chose to make the centre of his comedy. And it’s just wonderful laughs all the way through.

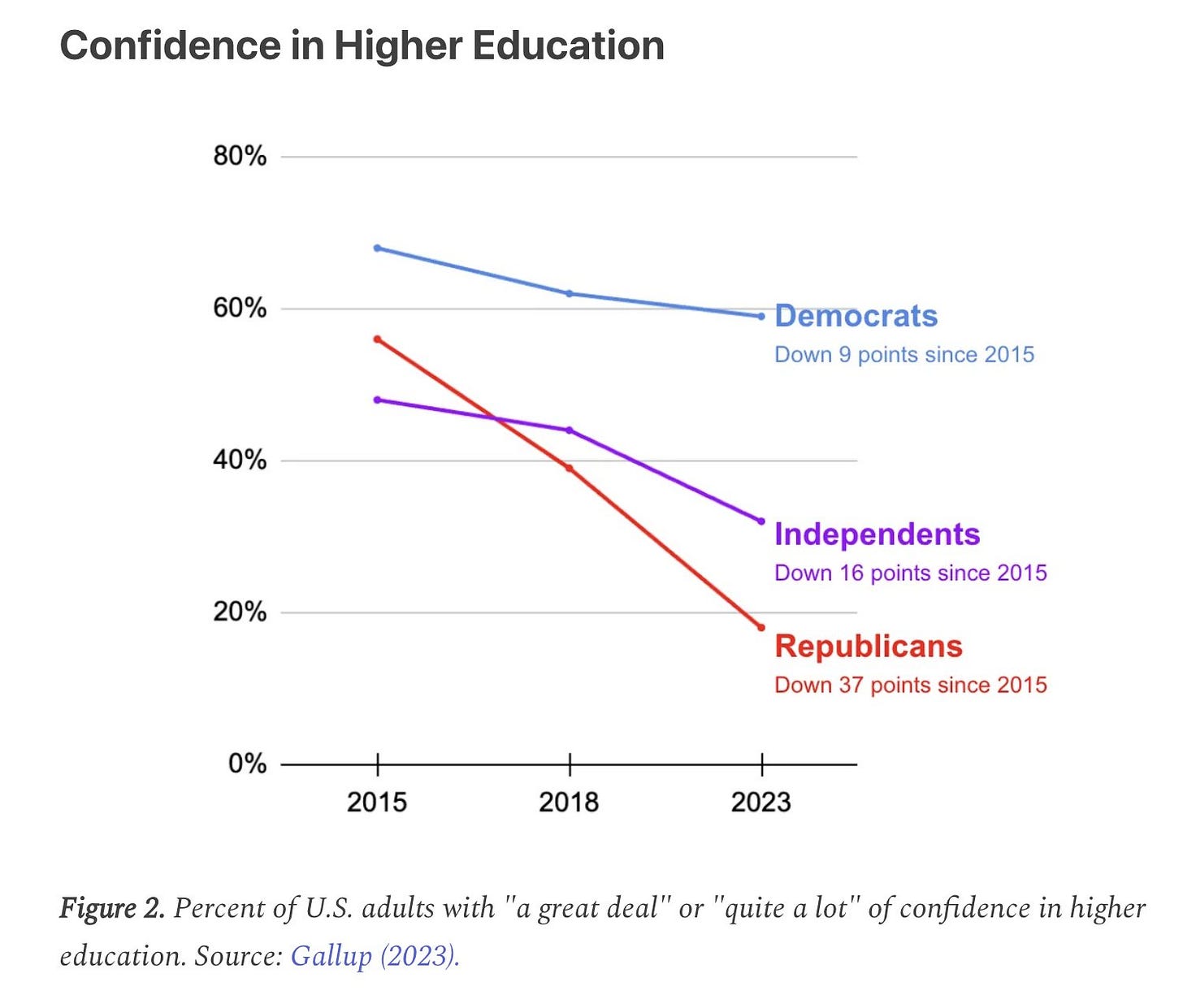

Meanwhile back in the academy

Not much of an article, but quite a graph.

Arthur Miller

In case you’re interested, Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy is free to listen to for members on Audible.

Bill Maher on Israel

Coleman Hughes on Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Mood

Great take down. This is just an extract from the beginning of a long article. The real ‘news’ associated with the publication of the book being reviewed is Coates’ revivificiation of the anti-semitism he was brought up with and which gets intensified and reinvented through Israel being coded ‘white’ against the Palestinians being ‘black’. That part is highly recommended, but not extracted below.

The Message, is a masterpiece of warped arguments and moral confusion. … Coates’s overarching themes are familiar: the plundering of black wealth by the Western world, the hypocrisy at the heart of America’s founding ideals, and the permanence of white supremacy. …

In his first essay, “Journalism Is Not a Luxury,” Coates recalls the sentiment that drew him to the written word: the feeling of being haunted. He returns to the word haunted over and over. … I acknowledge the value of being “haunted.” In fact, I quite like the feeling. But my view is that if you want to feel haunted, go listen to Debussy, Radiohead, or Kid Cudi. That way, you will get all of the “haunted” feeling without any of the pretense that you’re learning something of value about the world.

Not everyone would agree that a good journalist needs to be a ghost, or that haunting, rather than informing, is journalism’s primary objective. A contrary view would hold that while a good nonfiction writer can certainly enchant the reader, communicating what is true and useful is a primary part of the job. Put simply, you must give your reader a clear and honest sense of the big picture.

Here’s the crucial test of that metric: If you read nothing about a subject other than this author’s work, how informed would you be? To what degree would you understand the big picture?

On that metric, Coates fails spectacularly. Because Coates is not a journalist so much as a composer—one who uses words not to convey the truth, much less to point a constructive path forward, but to create a mood, the same way that a film scorer uses notes. And the specter haunting this book, and indeed all of his work, is the crudest version of identity politics in which everything—wealth disparity, American history, our education system, and the long-standing conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors—are reduced to a childlike story in which the “victims” can do no wrong (and have no agency) and the “villains” can do no right (and are all-powerful).

Take, for instance, his second essay, “On Pharaohs.” Beginning as an account of his trip to Senegal, the essay becomes a meditation on the relationship between Africans and African Americans—as well as the relationship of both groups to their ongoing “oppressor”: the West.

The essay relies, for emotional weight, on Coates’s assumption that Western nations are rich, and African nations are poor, because of colonialism. This framework makes the West morally responsible for the poverty of countries like Senegal.

But economists have long exposed the problems with this theory. For starters, five-hundred years ago, the whole world was poor. Wealth was created only when certain nations began to adopt a set of key institutions: property rights, honest government, markets, rule of law, and political stability. These institutions rewarded productivity and, in particular, innovation. Every nation that has adopted these institutions has grown exponentially as a result. Every nation that hasn’t has remained in the default state of poverty.

One of the virtues of this theory is that, unlike Coates’s theory, it actually explains the world around us.

Why did Japan and South Korea have similar “growth miracles” in the twentieth century even though Japan was the historic colonizer and Korea its colony? Because they both adopted the key institutions. Why is Ethiopia poor even though it was never a colony? Because, like its African neighbors, it has not yet adopted them.

Insofar as African nations would like to have “growth miracles” of their own, they will need to import the political institutions that reliably create wealth. Most of those institutions are “Western” in origin. Thus, it does no one any good to nurse in Africans a hatred of the West and its institutions—except perhaps Western liberals, many of whom derive a perverse pleasure from castigating themselves, their countries, and their ancestors.

What’s more, colonialism and slavery were hardly Western inventions. As I read this chapter I couldn’t help but remember a detail from Between the World and Me, in which Coates tells his son that he’s named for Samori Touré, who stood up to the French in West Africa. He omits the earlier chapter in Touré’s career when he captured, enslaved, and sold thousands of Africans to Arab, African, and European traders as part of the spoils of his decades-long expansionist empire. This behavior, of course, was considered normal at the time. Which is exactly the point. But reading Coates, you would have no idea that anyone other than Europeans had ever committed such ugly acts. …

Hail to the SNACC

Dean Ashenden on Makarrata

I recall Germaine Greer making fun of the word ‘reconciliation’. Couldn’t agree more. In my opinion it’s an adman’s word. Sounds good, and part of the reason it sounds good is that it’s so abstract. So empty, so devoid of detail about the terms on which it reconciliation takes place. Then there was ‘Voice’. Another nice word. So long as it remained abstract it was highly popular. But for it to something more than word work, it had to be institutionalised — and that meant it had to be specified. I voted for the voice with a heavy heart. I read a Henry Ergas column which argued that its institutional logic would be necessarily adversarial and antagonistic.

Now it happens that I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the very different logics of representation by election versus representation by sampling (as we do in juries). And the fact is that our system of representation is reflexively competitive. It’s all-purpose MO is to arrange people into competing tribes ‘for’ and ‘against’ and have have them yell at each other. So I couldn’t fault Henry’s logic. Anyway, here we are with Makarrata a word no-one understands. Anyway, it’s all about truth telling. Thing is, anyone who cares has a fair idea about the truth — aboriginal dispossession was a brutal, horrible fact, still rolling on as child removal when I was in my teens.

And as Dean Ashenden shows us, the Great Australian Forgetting is alive and well in Australia’s rural museums — I suspect particularly nearest those parts of Northern Australia in much of the most recent frontier was. So they don’t really want to know — or tell. So what to do? Somehow people with university degrees turning up and regulating or shaming them into submission sounds unpromising to me — and it will be unpromising to our politicians. So I agree with Dean. Get people working together.

[Exploring history museums in Barcaldine, Longreach and Winton in Queensland Ashenden writes] a total of 140-odd monuments, memorials, museums and the like range from The Drovers, a group of life-sized figures on Longreach’s main street, to Barcaldine’s 125th Anniversary of the Great Shearers’ Strikes monument to the Waltzing Matilda Centre in Winton.

This ubiquitous public history is, however, less than comprehensive and very much less than candid. … [N]one … records or even acknowledges, except in the most oblique way, that that there was a world before “settlement” or that it was swept away in the 1860s and 1870s when “explorers” and “pioneers” roamed around and across the country looking for “good land”; that the Queensland frontier was moving west at an estimated 300-plus kilometres a year; that this extraordinary movement was made possible by the efforts of the notorious Queensland Native Police and the “Queensland method” (pre-emptive eradication and intimidation as well as the more familiar reprisals); that these efforts were routinely supported and supplemented by squatters and station workers; that two of the many hundreds of massacres (the deliberate killing of five or more non-combatants) committed in Queensland were in the region, one of them, the infamous Skull Hole Massacre of 1870 costing 200 Aboriginal lives. …

If a “detailed analysis of the 2023 Voice to Parliament referendum and related social and political attitudes” is to be believed, truth-telling will be a lay down misère. The referendum vote, this ANU study finds, “did not signal a lack of support for reconciliation, for the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders having a say in matters that affect them, for truth-telling processes, or for a lack of pride in First Nations cultures”; in fact “all of these notions were supported by around eight-in-ten Australians, or even more.” The “vast majority,” we are assured, “think that the federal government should help reconciliation and roughly the same number (80.5 per cent) think that Australia should undertake formal truth-telling processes to acknowledge the reality of Australia’s shared history”. …

[T]he fact remains that decades of truth-telling have had little or no impact at all in an entire realm of story-telling and history production. What is the point of more truth-telling? It’s not more telling that we need. It’s more listening, learning, thinking, discussing and acting upon. We can hope that those “formal truth-telling processes” now under way in several capital cities will deliver long-denied reparations and treaties, which would be no small thing, but as vehicles of a substantial shift in our default view of ourselves and our story they will be water off the proverbial duck’s back.

What would or might work? Certainly not telling the recalcitrants that this time they “must listen to the historical truths told by First Nations people” as two academics recently demanded. In my book Telling Tennant’s Story I suggested a national project to encourage and support towns and communities to work with Indigenous people and local and professional historians to audit the public telling of their story and decide whether and how it might be more fully and truthfully told. Such grassroots work would not be an alternative to revamping peak institutions such as the Australian War Memorial (now entrusted to that amiable temporiser Kim Beazley); it would be a crucial complement to it.

That idea still seems to be worth considering, but with Longreach, Barcaldine and Winton freshly in mind, here are some suggestions about rules of engagement.

First: remember that the story is not simply or only one of violence, conflict and destruction, although it certainly includes all of those. Somewhere in the vicinity of even the worst moments will almost always be found white support, kindness, even resistance to what was being done to the Aboriginal peoples. Don’t demonise.

But don’t sentimentalise either, as Stanner reminded his comrade-in-arms Nugget Coombs. Those brutal killers of the Queensland Native Police (for example) were Aboriginal men, coopted, often coerced, always led, paid and supplied by the Europeans and their government, engaged to kill those who were to them “foreigners,” but brutal killers of tens of thousands of people nonetheless.

Third rule: don’t diminish the Man from Snowy River and its myriad equivalents, but do as Russell Ward did, in his time and in his way: expand and complicate the story, and distinguish between mythology and history.

Fourth: no holier-than-thou history! No enlightened present condescending (as E.P. Thomson put it) to the benighted past — a certain route to the misrepresentation of both.

And perhaps most important of all: listen to anyone who wants to have a say about the story and its telling. An honourable exception to the rule of public history: graffiti on the back of the dunny door at Attack Creek in the Northern Territory, contesting the whitefellas’ version, given on a nearby monument, of that celebrated moment in 1860 when John McDouall Stuart’s epic trek across the continent was stopped by “hostile natives.”

All this is work for a Makaratta Commission — in fact it’s hard to see it being done otherwise — and it’s important work. Public history comes from the past; it is the past’s preferred version of itself. But it is active in the present; it is the history curriculum of everyday life. What will it teach? Answering that question comes with added benefits: it could generate listening, thinking and learning in ways that mere telling cannot hope to match. …

It would not be a small undertaking, of course. It would big, long and expensive. What might it cost? Perhaps the bidding could start at the half a billion spent on extensions at the Australian War Memorial? Better: why not aim at the total spent by Howard and subsequent Coalition governments on public history installations telling the story we’d already heard over and over again?

Martin Wolf on Tim Snyder on Freedom

What is freedom and why does it matter? Timothy Snyder’s answer is that “freedom is the absolute among absolutes, the value of values. This is not because freedom is the one good thing to which all others must bow. It is because freedom is the condition in which the good things can flow within us and among us.” …

Snyder is no ivory tower academic. He seeks to make the world a better place via his books and his Substack, which is notably clear-eyed on the neo-fascism of Donald Trump’s Republican party. …

The book starts from a passionate conviction that freedom is not negative — and so defined by the absence of external constraints — but positive, and so defined by what we are able to do. The latter, in turn, depends on what we get from others. For Snyder, then, the capacity to recognise others as beings like ourselves is the foundation of freedom. Without that, we will treat others as objects, not subjects, and finish up with tyranny.

As Snyder notes, “Babies who are left alone learn nothing.” Children cannot acquire the personality and knowledge needed to be a free member of a free society on their own. Their achievement of individual sovereignty depends on what others do. But the ability of adults to act freely also depends on the honesty and competence of the judges, policemen, public servants and all those who pay their taxes and do vital jobs. …

Mobility is the challenge for mature people, says Snyder. A free society should indeed be a mobile one. But, he emphasises, mobility includes social mobility. A hereditary oligarchy is the opposite of such mobility.

This drives Snyder’s hostility to negative freedom — the idea that one is free once one is liberated from restrictions imposed by governments. This perspective is solipsistic and so “antisocial”. In the US, he argues, the “elevation of negative freedom in the 1980s set a political tone that lasted deep into the twenty-first century”. The purpose of government was “not to create the conditions of freedom for all but to remove barriers in order to help the wealthy consolidate their gains.” …

Factuality is fundamental: neither an individual nor a collective can make decisions without information. “Truthfulness”, argues Snyder, “is not an archaism or an eccentricity but a necessity for life and a source of freedom.” Deliberate lies of the kind that Trump and JD Vance have been telling about the consumption of pets by Haitian immigrants in Ohio make a mockery of democracy and so of freedom. Vladimir Putin is today’s master of such lies. …

Not least, argues Snyder, there must be solidarity. This follows from his most fundamental proposition that I am free because others are free. This is what makes the bonds of citizenship, on which freedom depends, work. If I am better off than others, I have an obligation to pay the taxes on which the freedom of others depends. This is the argument for sharing of the costs of bringing up children and of maintaining the health of all. At the limits, it means fighting in the defence of one’s country’s freedoms, as Ukrainians are doing. As Snyder insists: “Morally, logically, and politically, there is no freedom without solidarity.” …

Snyder is right about what is most important. He understands that freedom means choosing among competing values and accepting disagreement, while respecting the democratic rules over how it is managed. But freedom does not mean giving the wealthy the right to buy elections or the powerful the right to tear up the votes of people they dislike. Freedom is a precious gift. We have to defend it.

Celebrating a wonderful song with wonderful embellishment

The flutes’ embellishment of the chorus brought tears to my eyes for reasons I don’t quite understand. Can the music buffs tell me what that kind of effect is called? In any event, watching two people who’ve stuck to their guns, being themselves as they say, and then being celebrated for doing so — well that makes me feel very, very good.

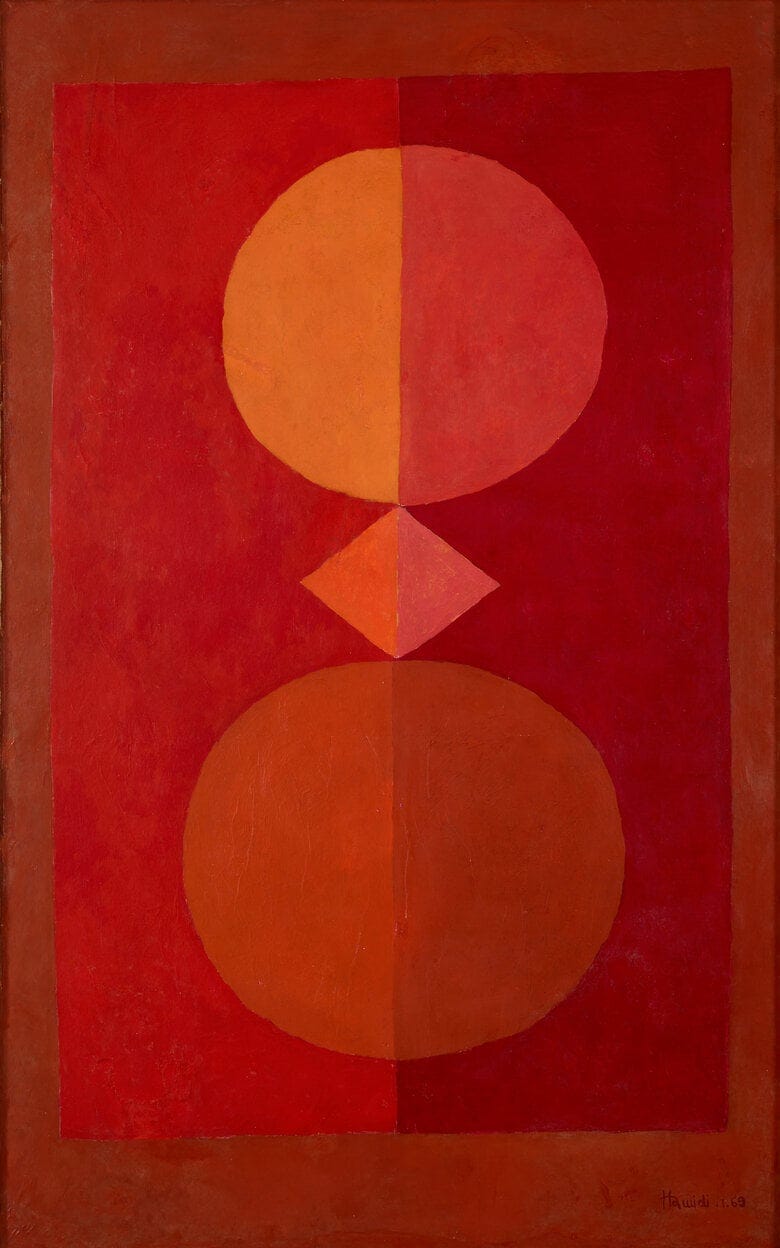

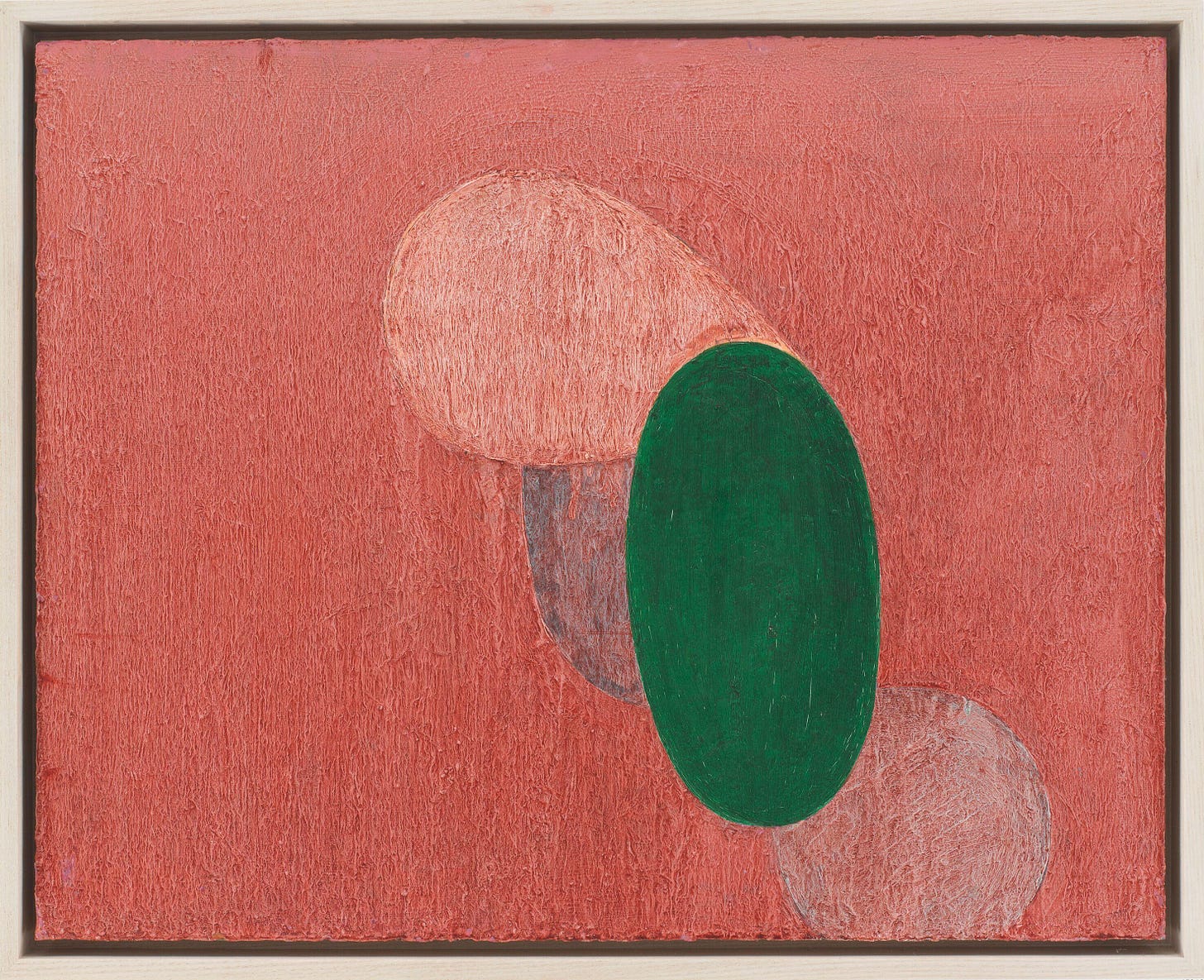

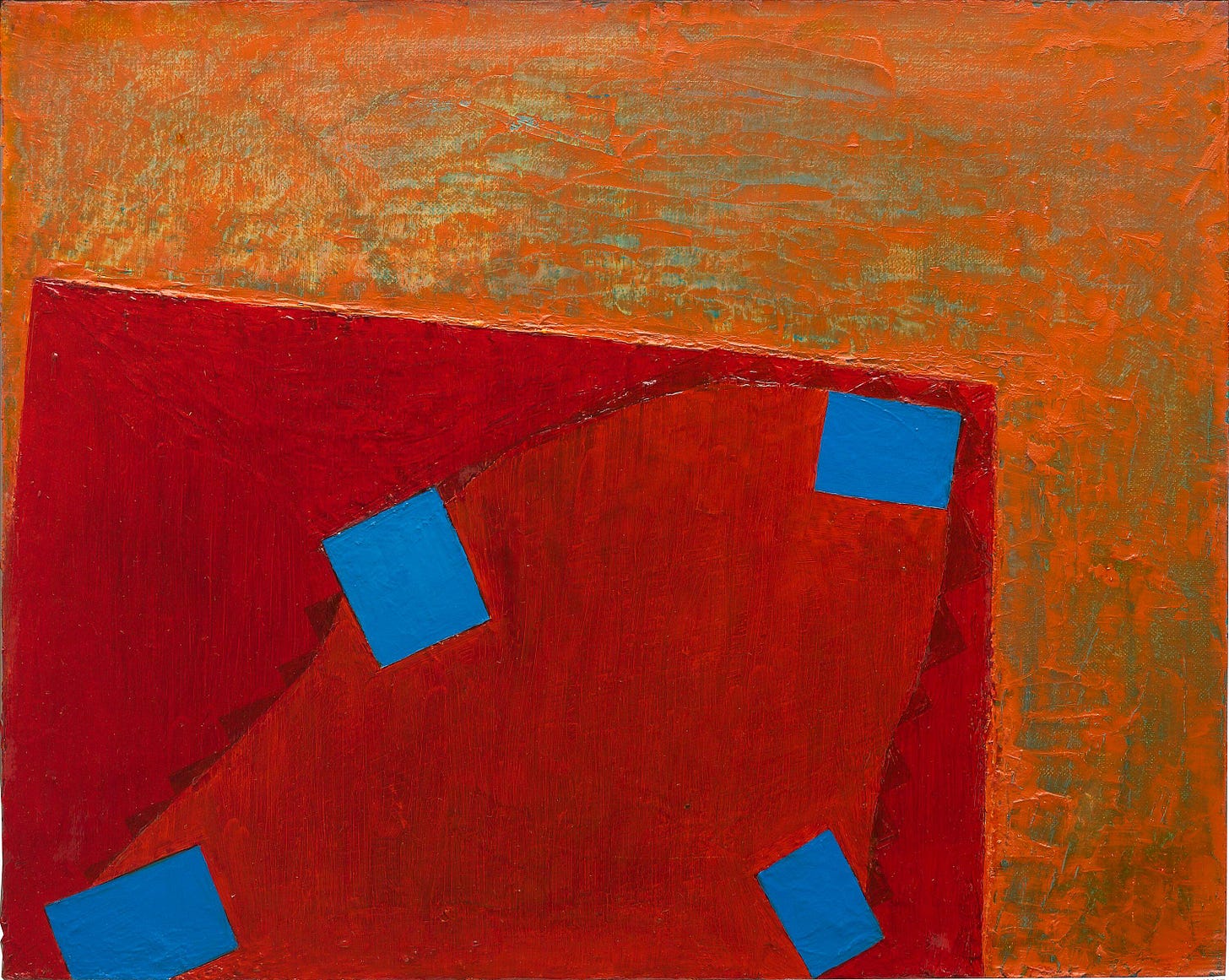

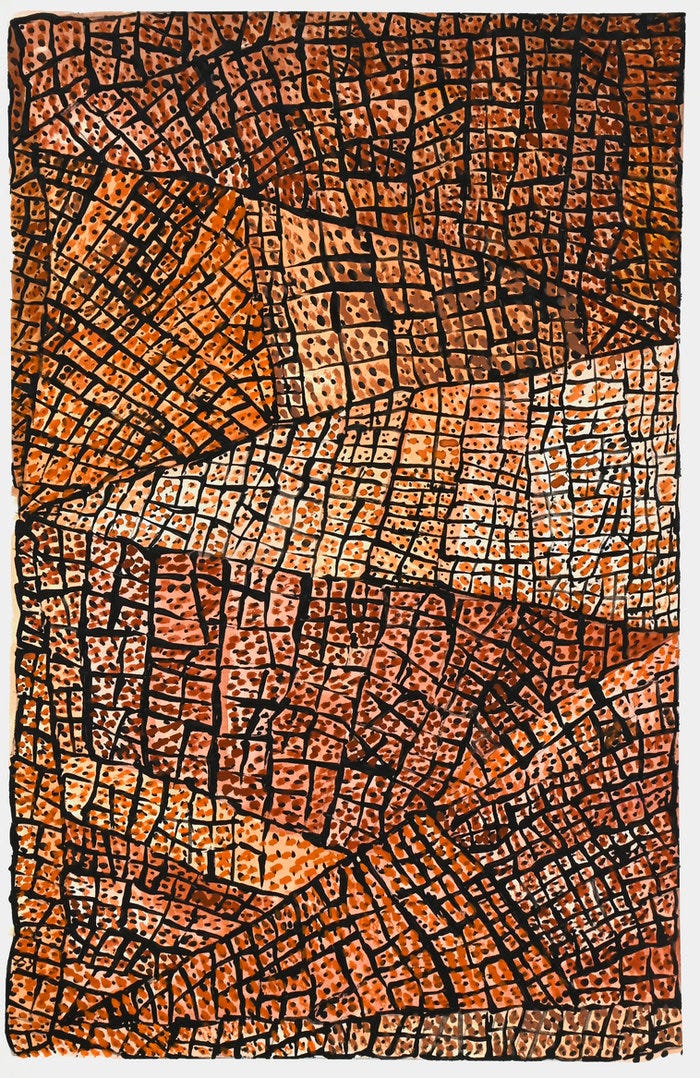

Thomas Nozkowski (who knew — not me!)

HT: Marc Mayer who started following me.