The echidna strategy

And other great things I found on the net this week

The echidna strategy

A reader sent me this passage from Sam Roggeveen’s new book

That term, ‘conservative’, raises the final piece of business for this introduction, which is to declare a political perspective. Typically, criticism of higher defence spending and a more assertive military posture comes from the left of politics. But I regard myself as a liberal-conservative. I append ‘liberal’ to the word ‘conservative’ because in Australia, the two traditions have worked in constructive tension, advancing welfare and liberty while constraining the forces of radicalism and maintaining a sense of ordered continuity. And I am at best a reluctant conservative because the kind of conservatism I defend is so hard to find in the real world. Actual existing conservatism in the early twenty-first century is a toxic brew of culture wars and ideological obsessions. The conservatism I defend is marked not by any specific ideological or policy agenda but merely by a preference for moderation over extremism, tradition over ideology, evolution over revolution, and a deep suspicion of utopianism.

Quite.

Always nice to have a Burkean conservative onboard, especially in Australia where they went more or less extinct on the mainland in the last 50 years replaced by mock Burkeans like Tony Abbott. In any event, a while back Sam corrected me and said he preferred to describe himself as Oakeshottean conservative. In any event, the Australian right need more of them.

You need to listen to Sam giving his excellent account of himself on Late Night Live below and go out and buy and instantly agree with the book. In fact I’ll go so far as to say that any current subscriber who doesn’t do so will be culled from the list of subscribers. (This will be administered via an honours system.)

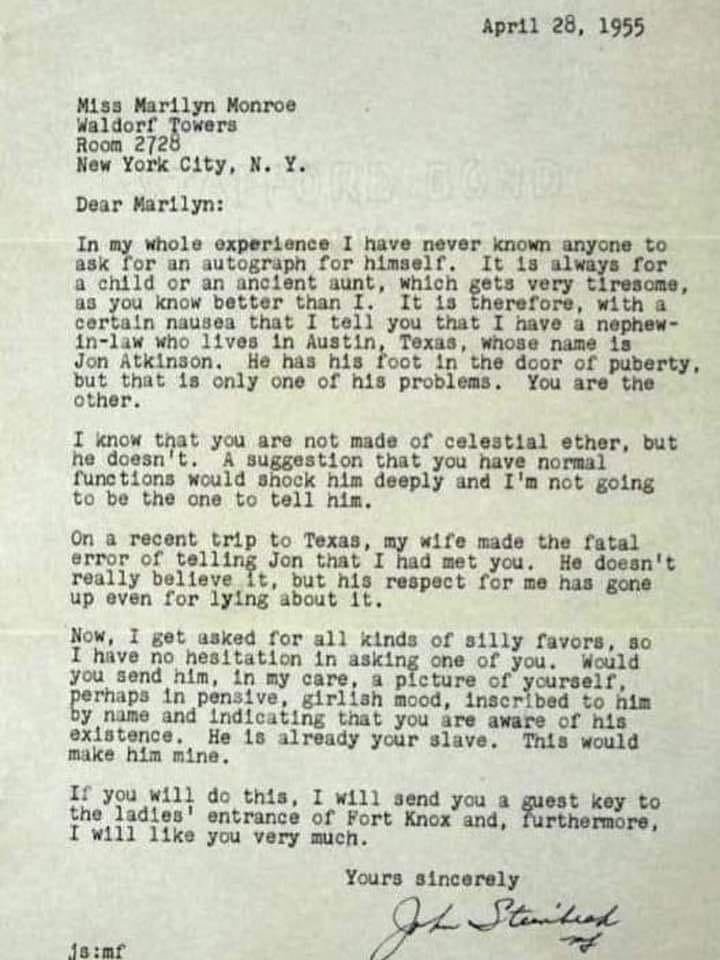

Who is this John Steinbeck and how can we get him to write gags for us?

Patricia Rogers isn’t a happy camper

Patricia Rogers is deeply knowledgeable about evaluation. Economists think they are, but usually are not. As I said in an address to the Australian Evaluation Society a while back:

Economists’ pride in the rigour and hard-headedness of their discipline has made them champions for evidence-based policy. As the economists at the PC have pointed out, we are spending many billions of dollars on programs to promote aboriginal welfare with remarkably little attention to whether they work or not. It’s the economists at the PC supported by economists like Peter Shergold and his successor Martin Parkinson that have managed to get an additional $40 million allocated for evaluating programs for indigenous Australians which is a great opportunity for policy learning, and God knows we could do with some in that area.

But too impatient, too hubristic a quest for rigour can lead us astray.

Here’s the thing. In the last few months, I’ve made a point of asking a number of such people at very senior levels, econocrats who regard themselves as rusted on evidence-based policy people if they know what ‘program logic’ or ‘theory of change’ are. They don’t.

Anyway, Andrew Leigh recently gave a speech about The Australian Centre for Evaluation outlining his enthusiasm for randomised controlled trials and that’s got Patricia concerned.

ACE seems to be promoting an outdated “gold standard” view of evaluation methods and “what works” view of evidence-informed policy.

I’m disappointed at the missed opportunity to support much needed evaluation innovation. But more than that, I’m concerned by the risks in this approach — risks which are evident from the history of evidence-based policy, and which should be anticipated and mitigated.

Three predictable problems

Firstly, the emphasis on impact evaluations risks displacing attention from other types of evaluation that are needed for accountable and effective government. …

Secondly, the emphasis on a narrow range of approaches to impact evaluation risks producing erroneous or misleading findings. ACE will focus on impact evaluations that use a counterfactual design — an estimate of what would have happened in the absence of the intervention. This is most commonly done through a control group. … Counterfactual approaches can work well when an intervention is at the individual level but are not possible or appropriate for many of the important policy issues government faces, especially those that operate at a community level such as public health. …

For these types of interventions, causal inference needs strategies more like those used in historical or criminal investigations — identifying evidence that does and does not fit with different causal explanations and adjudicating between them.

Privileging counterfactual impact evaluation, as a strategy to influence evaluation design more widely in the Australian government, creates the real risk that evaluators and evaluation managers will try to use these approaches when they are not appropriate. It also means that non-counterfactual evidence from individual evaluations or from multiple studies will be disregarded, even where it has been systematically and validly created. …

We have seen during the COVID pandemic what this can look like. One of the big questions was whether or not masks reduce the risk of transmission. A narrow interpretation of what counts as credible evidence led to some people claiming there was “no evidence” that masks worked because there had not been an RCT done. …

Thirdly, the focus on ‘measuring what works’ creates risks in terms of how evidence is used to inform policy and practice, especially in terms of equity. These approaches are designed to answer the question “what works” on average, which is a blunt and often inappropriate guide to what should be done in a particular situation. “What works” on average can be ineffective or even harmful for certain groups; “what doesn’t work” on average might be effective in certain circumstances.

For example, the Early Head Start program in the USA aimed to support better attachment between parents and children and better physical and mental health outcomes for both. On average it was effective. But for the families with the highest levels of disadvantage it was not only ineffective, it was actually harmful — producing worse cognitive and socio-emotional outcomes for children than those in the control group. However, although the report identified this result, it was not highlighted in the short summary of findings and the program is often included in lists of ‘evidence-based programs’ without any caveats — for example, the Victorian Government’s Menu of Evidence for Children and Family Services, which states reports that it was found to be effective, and that negative effects were “not found”.

These differential effects should not be explained away as a “nuance”, as they so often are, but as a central finding. Responsible public policy demands protecting the most vulnerable from further harm from government interventions. Summaries of findings framed around “what works” ignore this. This simplistic focus on “what works” risks presenting evidence-informed policy as being about applying an algorithm where the average effect is turned into a policy prescription for all.

Love and anarchy

As is the way with such things, finding Swept Away for you last week led to my finding another gem by Lina Wertmuller — in excellent quality complete with subtitles at Archive.org. Just click through on the image to watch the whole thing.

Post Liberalism is a thing: Just not a very good thing

I started extracting these paragraphs which were quite good until I got to the bit that said “Just as Deneen believes that elite rule is unavoidable, so does Ahmari presume the inevitability of hierarchy and coercion. Socialists reject these assumptions.” It’s all very well for socialists to reject these assumptions, but they shouldn't do it as a matter of doctrine. They should tell us what where Robert Michels went wrong in proposing his Iron Law of Oligarchy. It’s tricky. (Unless you’re a socialist I guess.)

Anyway, you should know about the material it’s reviewing. As the review points out the critique of liberalism has been raging since Patrick Deneen’s very successful book “Why Liberalism Failed”. (Long story short it failed because it succeded).

As liberalism has "become more fully itself," as its inner logic has become more evident and its self-contradictions manifest, it has generated pathologies that are at once deformations of its claims yet realizations of liberal ideology. A political philosophy that was launched to foster greater equality, defend a pluralist tapestry of different cultures and beliefs, protect human dignity, and, of course, expand liberty, in practice generates titanic inequality, enforces uniformity and homogeneity, fosters material and spiritual degradation, and undermines freedom.

Anyway I thought it a genuinely good book, though I was sceptical he had much to offer about how to move beyond liberalism. Sure enough his post-liberalism isn’t much chop. There’s also Sohrab Ahmari about whom I know nothing. So over to the review.

Much of these writers’ critique of liberalism, especially economic liberalism, echoes what socialists have been saying since the beginning of the industrial era. As is well known, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels railed against the contradictions of capitalism: the system produces extraordinary wealth by destroying prior modes of life, commodifying labor, and turning workers into appendages of the machine. Family, religion, community, and tradition are laid waste. Ahmari and Deneen do more than follow the timeworn path of trying to reinvigorate conservatism by infusing it with left ideas, however. They open up the possibility of a new political alliance against the common liberal enemy. This new fusionism would unite social conservatism and social democracy. The question is whether their aim is to ally with the Left or to displace it by offering an alternative expression of working-class grievance, one anchored in securing hierarchical order. …

There are two key fronts in this war. The first is the conservative movement itself. In a widely discussed 2019 polemic, Ahmari took aim at conservative acceptance of a pluralism of beliefs, arguing that it was necessary “to fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” Two years later, Deneen chastised “Conservative Inc.” not only for the toothlessness of its opposition to liberalism but also for its defense of fundamentally liberal notions of free markets, free speech, limited government, and constitutional originalism. Convinced that conservatism has failed to stop the onslaught of an ever more vigorous, ruthless, and triumphant liberalism, Ahmari and Deneen endeavor to rearm the movement with the truths of history, tradition, and faith. These truths can’t be put aside in the interest of political order; they have to be the basis for political order.

The second front is the much-hated liberalism. Here Ahmari and Deneen seem to diverge, perhaps in a division of labor. Ahmari takes on liberal political economy, so his battle looks like class war. Deneen remains in the trenches of culture war, so his looks like the populist “peasants with pitchforks.”

Ahmari depicts the capitalist coercion experienced by employees in the workplace and consumers in the marketplace: the precarity of workers on so-called flexible contracts; the arbitration agreements employees have no choice but to sign; the demolition of viable companies by predatory hedge funds and asset managers; the extortion of everyday people as vital emergency services are privatized; the loss of local political knowledge as newspapers go under; the lawlessness of a bankruptcy law that allowed Purdue Pharma to escape liability for the opioid crisis. In each of these instances, Ahmari tells a compelling story of the tyranny exercised by unrestrained capitalism. These are stories of the class war of bosses against employees, owners of capital against those who have to sell their labor power to survive. …

With Ahmari commanding the economic front, Deneen oversees the cultural. What he finds is a vast wasteland of addiction and despair, represented by declines in life expectancy, birthrates, and family formation. Children are sexualized. Pornography has replaced religion. An elite professional managerial class disparages the values of family and community deeply cherished by those in the flyover states, wielding identity politics to divide the many and maintain its hold on power.

For Deneen, the cause of all these problems is liberalism, the economic liberalism of the Right and the social liberalism of the Left, libertarianism and libertinism. Combined in today’s managerial meritocracy, these two sides of liberalism are animated by the same emphases on progress and individual choice.

Amazing Aretha

I happened upon this recording of Aretha doing gospel in a church in 1972. Electrifying. Click on the image to check it out.Brink Lindsay on Post-liberalism

Someone wrote to me asking what I thought of this post. Here’s my reply:

His posts are a bit long so they often slip through. I find I am interested in many of his concerns though I sometimes think his solutions are a bit too much from the economists’ playbook — when I think our main problems are elsewhere (even if we could improve our economic act in various ways).

However I thought the quality of this one was pretty good. In addition I agreed with virtually every one of his conclusions.I’ve always been alarmed by how little support our society gives to the culture on which it runs. Still as he says, for long periods of time nothing too bad happened and lots of good things came from the democratisation. (To be clear I’m much more alarmed — like conservatives always have been — about the way the market commoditises culture and operates as an acid bath. All that is solid melts into air. On the other hand conservatism never struck me as having much to say about how to address the problem — as I wrote towards the end of this post.

I’ve read and admired Crawford — and got a lot out of his book The world beyond your head, but have watched on dismayed at his turn to the ‘post-liberal’ which is just a disastrous position I think. Lyons is quite a bit worse, and very proud of his apocalyptic vapourings. Gnosticism indeed! Meanwhile I admired a piece by Tanner Greer and did a podcast with him which was pretty interesting I thought.

As I discussed with Greer towards the end of our podcast, I think of my own fondness for sortition and similar mechanisms very much as a (non-conservative, or at least non-right wing) response to the issues raised.

Anyway, on with the show — and I haven’t extracted his material in the article on Tocqueville, but you should check it out.

However incomplete its vision, conservatism does possess important partial truths. And in the 20th century, the old Burkean suspicion of centralizing utopianism once again proved illuminating — in particular, by revealing the supposed ideological opposites of communism and fascism as the products of a common totalitarian impulse. … At the root of the malaise gripping the United States and other advanced democracies is the fact that these societies are disintegrating. …

In short, virtually all the intermediate institutions that lend structure and coherence and solidarity and workable consensus to the superhuman scale of contemporary mass society are in decline. You can see it in the steadily dropping numbers for public trust in most major social institutions. The result is progressive atomization, as people’s connections to anything other than the market and state loosen and fray.

Let me refer now to a trio of writers whom I consider to be among the most thoughtful and insightful observers on the political right today: Tanner Greer, Matthew Crawford, and N.S. Lyons.

I reject this post-liberal position completely and unreservedly. It is of course true that there are totalitarian tendencies in modernity — we saw them come to full flower in the great tyrannies of the 20th century. But the dominant tendencies have surely been liberating and humanitarian: a colossal increase in the number of human beings coinciding with a dramatic uplift in material living standards; an explosion in scientific knowledge and technological capabilities coinciding with mass literacy and schooling; the emergence of governments subject to popular control and the rule of law coinciding with the stigmatization of war and widespread embrace of an ideal of universal human dignity. I find it genuinely hard to understand how thinkers who accuse their opponents (with some justification) of antihumanism can fail to recognize the profoundly anti-human implications of their ideas. How does one profess love for God’s creation and then hold the view that the vast majority of people alive today are here only because of some dreadful mistake?

With that important and fundamental difference noted (which, to repeat, does not apply to Tanner Greer), I will say that I find much to agree with in this critique from the right. These three men’s account of how complexification and bureaucratization have brought about mass learned helplessness jibes with thoughts I expressed in “The Need for a Counterculture.” The connection they draw between expressive individualism and ongoing atomization mirrors my analysis in “The Loss of Faith” and “Saying Yes.” Their disdain for identity politics aligns with my own, as expressed in “The Performative Turn.” Greer’s discussion of the generally enervating effects of “life under management” has important overlap with points I made in “Loss Aversion (by Any Other Name) and the Decline of Dynamism.” The worries I expressed in “The Retreat from Reality” and “Choosing the Experience Machine” line up with Lyons’s points about abstraction and dematerialization. And Lyons’s depiction of a developing global managerial monoculture complements points I made in “The Absence of Systemic Competition.”

But while I agree that contemporary society’s concentration of social power and initiative within the PMC elite carries real potential for despotic abuse, I find the efforts of Crawford and Lyons — and other post-liberals — to portray the United States today as an emerging progressive tyranny to be overwrought and unconvincing.

Ezra Klein interviews Daniel Markovits

I was listening to this podcast this week and it’s remarkable what a good podcaster Klein is. Always interested in exploring the arguments. This is a particular good discussion I think.

A good discussion of post war Oxford Philosophy

Muddling yes, but through?

When the Boat comes in

I remember when I was a kid my parents used to watch the BBC program When the Boat comes in. One of those 55 minute dramas. I expect it was very good and probably watched and enjoyed the one or two programs I could be bothered watching. Anyway, the song always struck me. The BBC rendition is quite comical. Then I heard Bob Fox’s version (the video below) which I loved. The voice is so deep and resonant. And very very said it seems to me. Such renunciation as each cycle they sing about what will be brought back for them when the boat comes in — what little fishy they’ll get until they get to the very finest thing they can aspire to. A salmon. All the while their lives are so miserable all the adults go from one drink to the next and so the cycle of neglect and renunciation continues.

And it put me in mind of Carrickfergus. It’s very hard to find a recording of it that isn’t dripping with sentimentality. But I remembered this geezer I’d heard called Declan someone. It was pretty obvious pretty quickly that it wasn’t Delcan Galbraith. I think it was the late Declan Affley. Anyway, listen to the way he sings it.

And the demon drink is there ruining lives in that song too.

Now in Kilkenny it is reported

On marble stone there as black as ink

With gold and silver I would support her

But I'll sing no more now 'til I get a drink

For I'm drunk today and I'm seldom sober

A handsome rover from town to town

Ah but I'm sick now my days are numbered

Come all ye young men and lay me down

Journalist humanises politician over a meal: SHOCK!!

I object to the carry on but I did laugh!

The marriage question

A letter Eliot had sent to Blackwood a couple of weeks earlier. She had, she told her publisher, been looking over their old correspondence, which now stretched back twenty years to Blackwood’s letter praising The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton in the autumn of 1856. She told him how much she owed him,26 that she could not have written her novels without him — ‘you may conceive this in her language,’ Blackwood wrote delightedly to his nephew, describing this ‘most charming letter from George Eliot’. To Eliot, he confessed that

Tears came into my eyes, and I read the passage at once to my wife who was sitting beside me when I received the letter. I look upon such expressions coming from you, as the very highest compliment that a man holding the position I do could receive, and I shall keep the letter for my children as a memorial that their father was good for something in his day. You are too good about my poor letters which I always felt to be too meagre and too few but I do look back upon our correspondence with pride and pleasure.

With his usual discretion, Blackwood did not tell her that his tears were also prompted by ‘the context about herself’. He meant, surely, the peculiar vulnerability of her unconventional marriage situation, and perhaps also her vulnerability in relation to Lewes. Her dependence on Blackwood — a loyal editor who had always recognized her talent, and valued her art above its market price — made her grateful letter all the more touching. And why not be moved to tears by this quiet love between publisher and author — a conservative family man and a fallen woman, bound into a deep friendship, indeed a shared destiny, by their devotion to George Eliot’s art.

From All Quiet on the Western Front

It is strange that all the memories that come have these two qualities. They are always completely calm, that is predominant in them; and even if they are not really calm, they become so. They are soundless apparitions that speak to me, with looks and gestures silently, without any word—and it is the alarm of their silence that forces me to lay hold of my sleeve and my rifle lest I should abandon myself to the liberation and allurement in which my body would dilate and gently pass away into the still forces that lie behind these things.

They are quiet in this way, because quietness is so unattainable for us now. At the front there is no quietness and the curse of the front reaches so far that we never pass beyond it. Even in the remote depots and rest-areas the droning and the muffled noise of shelling is always in our ears. We are never so far off that it is no more to be heard. But these last few days it has been unbearable.

Their stillness is the reason why these memories of former times do not awaken desire so much as sorrow—a vast, inapprehensible melancholy. Once we had such desires—but they return not. They are past, they belong to another world that is gone from us. In the barracks they called forth a rebellious, wild craving for their return; for then they were still bound to us, we belonged to them and they to us, even though we were already absent from them. They appeared in the soldiers’ songs which we sang as we marched between the glow of the dawn and the black silhouettes of the forests to drill on the moor, they were a powerful remembrance that was in us and came from us.

But here in the trenches they are completely lost to us. They arise no more; we are dead and they stand remote on the horizon, they are a mysterious reflection, an apparition, that haunts us, that we fear and love without hope. They are strong and our desire is strong—but they are unattainable, and we know it.

And even if these scenes of our youth were given back to us we would hardly know what to do. The tender, secret influence that passed from them into us could not rise again. We might be amongst them and move in them; we might remember and love them and be stirred by the sight of them. But it would be like gazing at the photograph of a dead comrade; those are his features, it is his face, and the days we spent together take on a mournful life in the memory; but the man himself it is not.

We could never regain the old intimacy with those scenes. It was not any recognition of their beauty and their significance that attracted us, but the communion, the feeling of a comradeship with the things and events of our existence, which cut us off and made the world of our parents a thing incomprehensible to us—for then we surrendered ourselves to events and were lost in them, and the least little thing was enough to carry us down the stream of eternity. Perhaps it was only the privilege of our youth, but as yet we recognized no limits and saw nowhere an end. We had that thrill of expectation in the blood which united us with the course of our days.

To-day we would pass through the scenes of our youth like travellers. We are burnt up by hard facts; like tradesmen we understand distinctions, and like butchers, necessities. We are no longer untroubled—we are indifferent. We might exist there; but should we really live there?

We are forlorn like children, and experienced like old men, we are crude and sorrowful and superficial—I believe we are lost.

also https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/the-open-society-prophets

Thanks — looks interesting.