The bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back

Institutional accountability edition

This was the mood in the world my parents grew up in. Of building after an interlude in which we learned that humangoes were capable of fully inhabiting the world in which God had died and anything goes. My generation? We didn’t do so well. You might argue that we’ve been a low dishonest generation. And here we are, handing things over to the next one.

Hilarious

Looking after the little people

As ordinary language philosopher extraordinaire J. L. Austen liked to joke “There's the bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back.” That’s the way public inquiries go. Lawyers turn up at ten grand a day or more. And legal cross examination is one of the few institutions left in our society where we entitle people to go in search of the actual, factual truth. It was fun watching it come out in the Leveson Inquiry in the UK staring Rupert Murdoch having the humblest day of his life. And in the Robodebt inquiry.

But then life as usual takes its course. As I said regarding the Leveson inquiry

[M]y journalist friend said “at last Rupert is finished”. I wondered why he’d be finished. She said News Ltd would be taken over by corporate managers, rather than the dynastic leaders Rupert had appointed.

Anyway, it turned out that the inquiry was the bit where you said it and after the inquiry was the bit where you took it back. Rupert is fine. So too are all those people whose only crime was being part of a system that behaved with such disregard that it drove numerous innocent people to suicide. They were simply obeying, well not orders. But then it didn’t have to come to that. They were obeying the institutional imperatives baked into the system. And no doubt it will happen again.

Over to Tim Dunlop for comment:

“It is remarkable,” Royal Commissioner Catherine Holmes noted in the preface to her report, “how little interest there seems to have been in ensuring the Scheme’s legality, how rushed its implementation was, how little thought was given to how it would affect welfare recipients and the lengths to which public servants were prepared to go to oblige ministers on a quest for savings.”

No such lack of interest and rushed implementation has characterised how various agencies have responded since she lodged her report. Not only has every courtesy been extended to those the Royal Commissioner referred for investigation—including their ongoing anonymity—but those agencies have dragged their feet, and to this point not one person has been charged with a crime.

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) has yet to finish its investigations, and the latest update on their website notes, without any apparent irony, given how the victims of Robodebt themselves were treated, that “The 16 matters are complex, with a significant volume of evidence. Sufficient time is required to allow the Independent Reviewers, Mr Stephen Sedgwick AO and Ms Penny Shakespeare, to conduct the inquiries in a manner that is robust and affords respondents appropriate procedural fairness.”

The APSC had previously announced that “Agency Heads have considered the full range of actions available for effective and proportionate responses to the adverse commentary presented in the Royal Commission’s report,” and that they have “determined the most appropriate action to improve or change behaviour, including ongoing management of performance through counselling, training, mentoring or closer supervision for those employees not referred to the APS Code of Conduct processes.”

Now, just to squeeze more lemon onto the open wound, the freshly minted National Anti-Corruption Commission—a secretive organisation, who are not obliged to conduct their inquiries in public out of deference to the type of person likely to be brought before them—has issued a press release saying they have “decided not to commence a corruption investigation as it would not add value in the public interest.”

It is worth lingering on the justifications they provide, all of which amounts to, some might say, the sort of Yes, Prime Minister circling of the wagons where chaps don’t go after chaps.

In deciding whether to commence a corruption investigation, the Commission takes into account a range of factors. A significant consideration is whether a corruption investigation would add value in the public interest, and that is particularly relevant where there are or have been other investigations into the same matter. There is not value in duplicating work that has been or is being done by others, in this case with the investigatory powers of the Royal Commission, and the remedial powers of the APSC.

Beyond considering whether the conduct in question amounted to corrupt conduct within the meaning of the Act and, if satisfied, making such a finding, the Commission cannot grant a remedy or impose a sanction (as the APSC can). Nor could it make any recommendation that could not have been made by the Robodebt Royal Commission. An investigation by the Commission would not provide any individual remedy or redress for the recipients of government payments or their families who suffered due to the Robodebt Scheme.

The sheer of nerve of using the Royal Commission’s own investigation as an excuse for not pursuing further investigations, when it was the Royal Commission that referred these people to NACC for further investigation in the first place, is Trumpian, or Orwellian, in its disingenuousness.

And again, you can’t help but notice all the due process and righteous concerns for fairness that were conspicuously absent when ordinary members of the public were confronted with their “robodebts” are suddenly front-and-centre when it is the “chaps” who are in the dock. Or not in the dock, as the case may be.

To then imperiously conclude that further investigation would not be in the public interest is the sort of out-of-touch arrogance that makes you wonder if any lessons have been learned from all this.

Anyway, you get the picture. And if you have any concerns, counselling is always available. LOLs all round.

Honours for the boys? Jacqui’s not a fan either

Weird nerds, science and being a team player

Ruxandra weighs in.

A few weeks ago, a lot of people on academic X quickly forgot about their support for “Women in STEM” and got angry at, of all people, Katalin Karikó, the co-inventor of the mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines and 2023 Nobel Prize winner. Her crime? A passage from her book where she laments that academia involved way too much people pleasing and political games for her. Reactions varied1 from angry: “Who does she think she is”/”We are all Geniuses, not only her, we all deserve funding, why does she think she is special”/”Nooo, she is a jerk” to self-satisfied, cynical: “Well of course this is how it is, why are intelligent people so naive?”

Ruxandra’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The quote in question:

But I was learning that succeeding at a research institution like Penn required skills that had little to do with science. You needed the ability to sell yourself and your work. You needed to attract funding. You needed the kind of interpersonal savvy that got you invited to speak at conferences and made people eager to mentor and support you. You needed to know how to do things that I have never had any interest in (flattering people, schmoozing, being agreeable when you disagree, even when you are 100% certain you are correct). You needed to know how to climb the political ladder, to value a hierarchy that had always seemed, at best, wholly uninteresting (and, at worst, antithetical to good science.) I wasn’t interested in those kills. I did not want to play political games. Nor did I think I should have to.

A couple of months ago I wrote a piece called “The flight of the Weird Nerd from academia”, in which I argued there is a trend wherein Weird Nerds are being driven out of academia by the so-called Failed Corporatist phenotype. Katalin Karikó is a perfect example of a Weird Nerd. I recently argued that many Weird Nerds (I called them autistics, but people really hated that2), have found a refuge on the Internet, where their strengths are amplified and their weaknesses are less important. There, I make the case for why these people are uniquely suited for creative intellectual endeavours and why they might slip through the cracks in a lot of normal jobs. Judging from a (short) lifetime of personal observations as well as the vitriol launched at Kariko for daring to not be “normal”, I suspect some explicit pro-Weird Nerd norms have to exist in an institution that seeks to properly utilize these people, for the benefit of us all. To formalize this:

“Any system that is not explicitly pro-Weird Nerd will turn anti-Weird Nerd pretty quickly.”

That is because most people, while liking non-conformism in the abstract and post-facto, are not very willing to actually put up with the personality trade-offs of Weird Nerds in practice. There is an increasing number of people right now who are thinking about how to build better intellectual institutions (e.g. those who study metascience.) Yet surprisingly little attention is given to human capital outside of “Let’s increase immigration” (a good idea, don’t get me wrong.) But if the rule turns out to be true, I think it’s worth thinking about what kind of people one wants to attract in these institutions and how to keep them there. And I believe the conversation here starts with accepting a simple truth, which is that Weird Nerds will have certain traits that might be less than ideal, that these traits come “in a package” with other, very good traits, and if one makes filtering or promotion based on the absence of those traits a priority, they will miss out on the positives. It means really internalizing the existence of trade-offs in human personality, in an era where accepting trade-offs is deeply unfashionable, and structuring institutions and their cultures while keeping them in mind.

The war against ‘incurable dishonesty’

The bit where W.H. Auden said it and the bit where he took it back

I ran into this getting the link for the ‘low dishonest' decade’ reference in the opening story. It’s intriguing. And what a poem, even if Auden ended up thinking it dishonest.

Auden’s poem consists of 99 lines, written in trimeters, divided into nine 11-line stanzas with a shifting rhyme scheme, each stanza being composed of just one sentence so that – as the poet Joseph Brodsky pointed out – the thought unit corresponds exactly to the stanzaic unit, which corresponds also to the grammatical unit. Which is neat. Too neat.

Because of course this is only the beginning of an understanding of how a poem works. It takes us only to the very edges of the piece, to the outskirts of its vast territory. In order properly to comprehend it we would need to know why Auden chose this rigorous, cramped, bastard form. And why did he begin the poem with an “I”, undoubtedly the most depressing and dreary little pronoun in the English language?

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:Who is this “I”? And why are they sitting in a dive? And is it real or is it imagined, this place? And why the double adjectives?

Trying to understand how a poem works is one thing: trying to understand what’s wrong with it is another. “Rereading a poem of mine,” Auden wrote, looking back, “1st September, 1939, after it had been published I came to the line ‘We must love one another or die’ and said to myself: ‘That’s a damned lie! We must die anyway.’ So, in the next edition, I altered it to ‘We must love one another and die.’ This didn’t seem to do either, so I cut the stanza. Still no good. The whole poem, I realized, was infected with an incurable dishonesty – and must be scrapped.” …

My explanation for the long life and afterlife of “September 1, 1939” is that it’s one of those poems that seems to provide simple answers to difficult questions, which is not necessarily a good thing. In studying it I’ve come to the conclusion that poetry can indeed uplift and sublimate and help us to make things good, but that it can also encourage us in false and sentimental ideas and emotions. Poetry can guide us, and it can lead us astray. And we have to acknowledge this, if we want to grant poetry its proper place in our lives. “The primary function of poetry, as of all the arts,” wrote Auden, “is to make us more aware of ourselves and the world around us. I do not know if such increased awareness makes us more moral or more efficient. I hope not. I think it makes us more human, and I am quite certain it makes us more difficult to deceive.” Auden died in 1973, most of his best work produced in the 1930s and 40s. It turns out that we need him now as much as ever.

And the poem as originally written

September 1, 1939

W. H. Auden 1907 – 1973

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism's face

And the international wrong.Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

"I will be true to the wife,

I'll concentrate more on my work,"

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf,

Who can speak for the dumb?All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

LBJ channels W. H. Auden

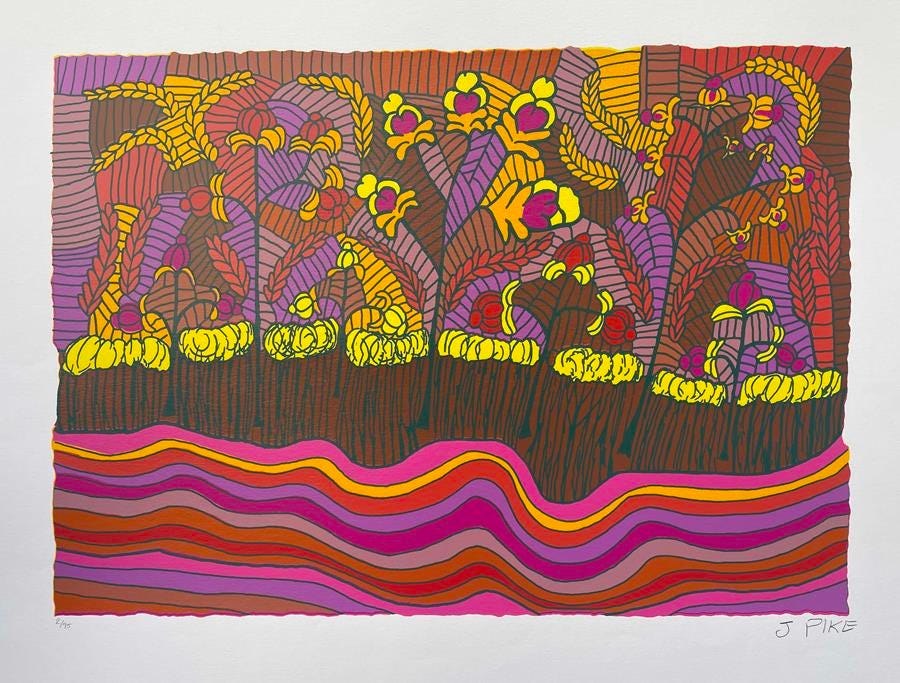

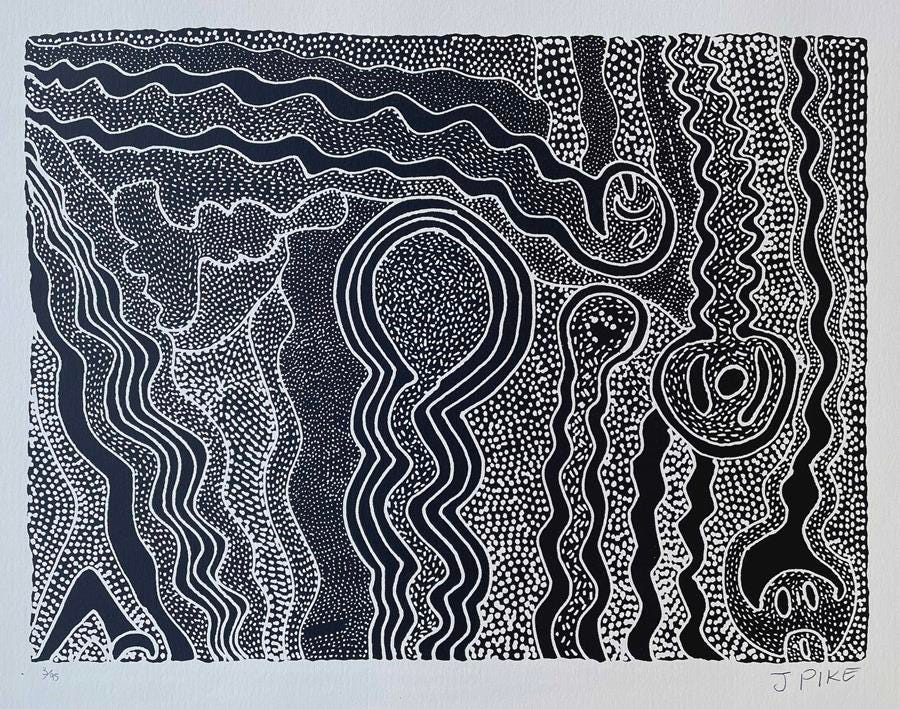

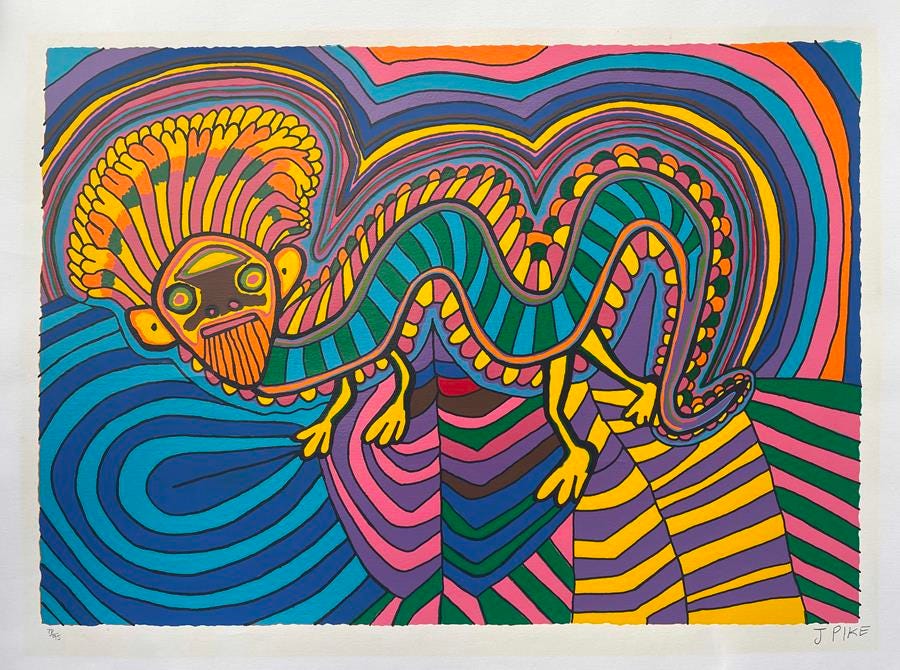

Jimmy Pike

And Freda Price Pwerle

And Eileen Bird Kngwarreye

An hour long talk from Andrew O’Hagan on ghosting a Julian Assange bio

Or here if you want to read it.

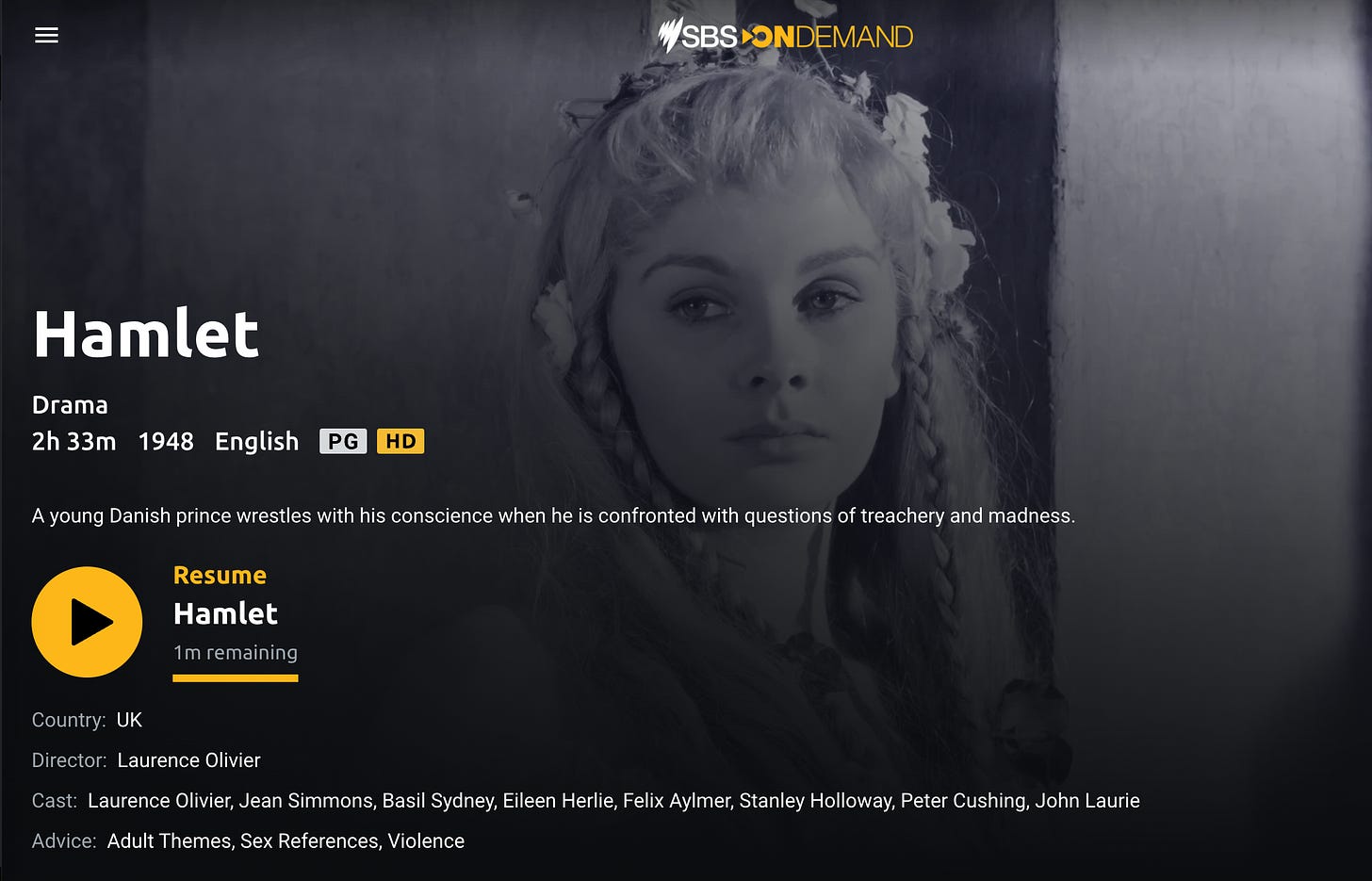

Hamlet

The famous Olivier version. I happened upon it and watched it through. It’s very good I reckon. And it rollicks along — quite gripping stuff. And how Shakespeare came along and churned out stuff like that for a popular audience is completely extraordinary. I mean musical genius is at least in a given idiom. With this, the endless freshness and inventiveness of the words is quite something at the stylistic level. But the breadth of the ideas is extraordinary.

John Keane resigns his German post

Karl Marx, a rebel son of Jewish parents, famously remarked that in politics Germans had only thought what others had already done. His quip needs a flip: Germans are nowadays doing things others find unthinkable. …

In the name of combatting ‘anti-semitism’, pro-Palestinian rallies are now regularly broken up by riot police. Commemorations of Nakba, wearing keffiyehs and displays of Palestinian flags and colours are discouraged or prohibited. Gatherings of liberal and leftist Jewish citizens who despise Netanyahu are banned because (police say) they are misused by troublemakers of ‘Palestinian origin’. Springer and other employers enforce oaths of loyalty to Israel. Germany’s dockyards have long supplied Israel with nuclear-tipped U-boats while last year German arms sales to Israel increased ten-fold. Even the Bundeswehr comes to its defence. In early February, without a Bundestag mandate, the warship Hessen sailed from Wilhelmshaven, headed for the Red Sea, carrying an unspecified number of ‘Seebataillon’ naval infantry troops mobilised to deal with the anti-Israel, Yemen-based Houthi ‘terrorist’ militia [That last bit sounds like a good idea to me, but what would I know?].

So what are German intellectuals saying about all these worrying trends? Almost nothing. Their cowardice is shocking. There are indeed brave souls who dare to dissent from the orthodoxy, but even when the intelligentsia comment on Israel’s war on Gaza, or pronounce on the principles of ethics and politics, as Jürgen Habermas, Rainer Forst and others did some months ago, their stated ‘solidarity with Israel’ functions as a German shibboleth unquestionably inscribed on Israeli stone.

The ancient Hebrew word shibboleth (שִׁבֹּלֶת) is the appropriate word needed here, for a shibboleth, as readers of the biblical Book of Judges know, is an utterance that functions as a password used by adherents of a group or sect to distinguish themselves from their enemies and, if necessary, as the biblical Gileadites did to the Ephraimites, exterminate them. The shibboleth ‘loyalty to Israel’ is oddly thin, but powerfully thick. It functions as an empty floating signifier with full-on inclusionary and exclusionary effects. Its semantic elasticity is used to mobilise and bind together its adherents by targeting their opponents as outsiders and foes. …

Loyalty to Israel is a bullying shibboleth with silencing effects, as I discovered first hand when receiving a nasty kangaroo-court letter accusing me of sympathy for ‘terrorism’ from Jutta Allmendinger, the Praesidentin of the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB), where I had worked as a research professor for a quarter of a century. The letter accused me of being a secret supporter of a fear-spreading ‘terrorist organisation’ known as Hamas and therefore under German law liable to criminal prosecution. I replied with a letter of resignation, in which I emphasised the Praesidentin’s one-sided, prejudiced preoccupation with Hamas and unthinking support for official state-sanctioned definitions of ‘terrorism’. I asked her two questions: Why was her letter silent about such vile matters as non-stop aerial bombardment, settler violence, the ruthless and reckless destruction of hospitals, schools, mosques, churches and universities, and crazed Israeli plans for the forcible removal and starvation of millions of people from their ancient homelands? And why is the WZB denying scholars their right to speak honestly, to say the unsayable, to ask why a state born of the ashes of genocide is now militarily hellbent on the ‘physical destruction in whole or in part’ (Genocide Convention Article II c) of an uprooted, terrorised people known as Palestinians?

More than a million people read my resignation letter on ‘X’ and Facebook; untold others commented and praised it on other social media platforms; private messages of support poured in from all points on our planet; while in China, where my work is read and discussed, my resignation letter truly went viral on the Little Red Book (xiǎohóngshū) lifestyle sharing platform. …

Making sense of silence is notoriously difficult, but what can safely be said is that the cowardly silence of one of Europe’s most prestigious research institutes typifies the general atmosphere in a Germany now in the grip of a shibboleth whose roots stretch back to the 1950s Adenauer period and which nowadays is producing ruinous political, reputational, legal and moral consequences. German Jews whose faith moves them to condemn Israel feel stifled; it’s as if they don’t belong in a country claiming atonement for its past annihilation of Jews. Perversely, German government praise for Israel’s steel-fisted stance against ‘terrorism’ and ‘Islamic extremism’ is feeding support for the avowedly pro-Israel, xenophobic, far-right populist AfD party, which commands the support of around 20% of voters and is now represented in 15 out of 16 state parliaments.

Enormous damage is also being inflicted on the global reputation of Germany, Germans and things German. The last generation’s efforts to rid the country of fascist thinking and sentiments by purging guilt and shame were impressive. In a matter of months, all the reputational gains have been undone globally by foolish declarations of unconditional loyalty to Israel. By condoning Israel’s self-destructive cruelty, Germany’s self-inflicted moral bankruptcy benefits neither state. And the damage done by the German shibboleth has legal consequences, as Nicaragua is demonstrating in the International Court of Justice by suing Germany for ‘facilitating the commission of genocide’ by selling weapons to Israel and cutting aid to the UN Palestinian refugee agency (UNRWA).

Worst of all, most tragically but least obviously, the German shibboleth prompts doubts about the grand legitimation narrative of the German state. The preamble of its constitution states that ‘the German people’ are the foundation of the republic, but the inconvenient truth is that the German shibboleth serves as a reminder of what W.G. (Max) Sebald, one of the greatest writers of the post-1945 generation, called the ‘well kept secret’ of Germany’s remarkable bounceback after the disasters of the first half of the 20th century. The secret is dirty: buried in the foundations of the German state are the millions of corpses of Nazi genocide, the Allies’ revenge bombing of German cities, which killed 600,000 civilians and left more than seven million homeless, and an earlier genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples in the colony of Southwest Africa – the first genocide of the 20th century only recently and reluctantly acknowledged by German politicians, but so far without offers of reparation to its victims. And now there’s another secret out in the open, in all its filth: a collaboration with genocide in which the foundations of the German state are mixed with the corpses of thousands and thousands of innocent Palestinian women, children and men who yearned only for a better future freed from the chains of racist humiliation, colonial injustice, organised hunger and murder.

The end of can-do?

HT: Gene

Manning Clark on Nov 11

Friend and colleague Gene Tunny sent me this extract from the Australian recording Manning Clark’s reaction to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government. A strange time-capsule.

A DAY OF DRAMA, ETERNAL INFAMY

By John Lapsley. First published November 12, 1975

Professor Manning Clark, the Australian historian who more than any other academic has succeeded in relating present-day Australia to its past, believes yesterday’s turmoil in Canberra may have placed the country on the road to future violent political change.“The great hope of the Whitlam government was that it could make changes taking us into the future without violence – without a bloody revolution,” Professor Clark said yesterday.

“If a conservative government gets a grip again, the next step forward for change would be much more likely to be violent.

“I think the reaction against the Whitlam Government, and the conservative drive to destroy it, and its temporary success – maybe just for a short time – is a comment on the Australian people, and not the Whitlam Government.

“It’s a reflection on the conservatism of the Australian people, their petty bourgeois attitudes, and their philistine attachment to the past.”

Professor Clark readily admits that he is a Whitlam Government supporter. “This is too serious a thing for me to do a eunuch act of academic detachment.”

He believes a temporary Fraser Government would have great difficulty in actually governing – as would a long-term one should he win office from any immediate election that stems from the crisis.

A temporary government? “I’m not sure whether the intellectuals, the students, or the trade unions would give him (Mr Fraser) a chance to govern,” he said, pointing out that widespread union action against a Liberal-National Country Party coalition might make problems equal to those for a government trying to rule without Supply.

“They’d be hassled, molested, and pestered … I wonder if the present crisis hasn’t made it extremely difficult for a conservative government to take over in Australia,” Professor Clark said.

He believes that the times make it hard for truly conservative governments to operate in advanced countries.

“I think the world has moved on from conservatism,” he said. “What’s happening here is that today, temporarily, a governor-general and Mr Fraser are putting the clock back. But they can’t do it for long. The historic forces are so strong now that they’ll be pushed aside.

“I can only hope that Mr Fraser would not try and turn the clock back too far … if he does get in. But I should expect that if Mr Whitlam really is gone, there would be a tremendously popular groundswell of support for him.”

Professor Clark believes an eventual result of the crisis will be the clipping of the wings of the Senate. His historian’s point of view of the Whitlam Government is that eventually it will be seen as a government that brought Australia up to date with the rest of the advanced world.

“The Whitlam Government’s achievement was that it brought Australia up to date – it put in the rubbish bin of history what we had not shaken off from the past.

“Socially its best achievements were Medibank, then trying to introduce equal opportunity into the education system. It’s possible that they tried to move too quickly, but I’m not convinced about that. Possibly this government’s great achievement, however, was that it tried to lift Australia up to 1975.”

From another time

Back when the quality of argument was a thing.

Their crazies; our annihilation

Sleep promotion takes off globally

Only kidding. But reading the abstract below I had one of those silly thoughts I used to have about three decades ago. You know how we were getting into ‘evidence-based’ policy and how we should tarket more than just GDP. (They didn’t use all those buzzwords then, but the ideas were in the air.) And doing something as sensible as targeting more than GDP was also a policy favoured by the early pioneers of economics like Alfred Marshall and Cecil Pigou.

That leads to the obvious question. What are some of the least cost ways of raising wellbeing (in an evidence-based way of course — we’re not working it out on ouija boards anymore.) Well if this study is anything to go by, the particular intervention they’re writing up here would have large negative costs because it doesn’t just improve wellbeing. It increases productivity. So unless all those wellbeing frameworks being put out by the Federal and State Governments are being released just because they sound good, you can expect these kinds of programs to being announced weekly for quite some time as they roll off the assembly line.

Only kidding …

Sleep: Educational Impact and Habit Formation

Osea Giuntella, Silvia Saccardo, and Sally Sadoff #32550

There is growing evidence on the importance of sleep for productivity, but little is known about the impact of interventions targeting sleep. In a field experiment among U.S. university students, we show that incentives for sleep increase both sleep and academic performance. Motivated by theories of cue-based habit formation, our primary intervention couples personalized bedtime reminders with morning feedback and immediate rewards for sleeping at least seven hours on weeknights. The intervention increases the share of nights with at least seven hours of sleep by 26 percent and average weeknight sleep by an estimated 19 minutes during a four-week treatment period, with persistent effects of about eight minutes per night during a one to five-week post-treatment period. Comparisons to secondary treatments show that immediate incentives have larger impacts on sleep than delayed incentives or reminders and feedback alone during the treatment period, but do not have statisticall! y distinguishable impacts on longer-term sleep habits in the post-treatment period. We estimate that immediate incentives improve average semester course performance by 0.075--0.088 grade points, a 0.10--0.11 standard deviation increase. Our results demonstrate that incentives to sleep can be a cost-effective tool for improving educational outcomes.

Heaviosity Half-hour

The failure of post-liberal alternatives

When you hear of all the bad things that are going down, and this is linked to the undoubted fact that we’ve been living under liberalism, it’s tempting to believe in post-liberalism, especially when the case is well put as it is, for instance by Patrick Deneen. Then again, if you keep an eye on where his sympathies are on Twitter — you wonder how his post-liberal alternative will stack up. Well the results are in. And they’re not pretty. Here’s Mark Lilla commenting on the recent rash of revanchist reveries from the right. It’s a good piece — which may not mean much more than that (in the immortal words of Stewart Lee) I agreed the fuck out of it.

For busy CEOs of multinational companies and global NGOs planning next year’s private jet flights into Davos, I’ve bolded a few of the best paragraphs. You’re welcome. I’ll join you in the green room.

The Tower and the Sewer

… It has always been more difficult to make sense of the radical right than the radical left. … [D]espite the intellectual and geographical variety, one always had the sense that the authors imagined they were aiming at the same abstract goal: a future of human emancipation into a state of freedom and equality.

But what ultimate goal do those on the radical right share? That’s harder to discern, since when addressing the present they almost always speak in the past tense. Contemporary life is compared to a half-imagined lost world that inspires and limits reflection about possible futures. Since there are many pasts that could conceivably provoke a militant nostalgia, one might think that the political right would therefore be hopelessly fractious. This turns out not to be true. It is possible to attend right-wing conferences whose speakers include national conservatives enamored of the Peace of Westphalia, secular populists enamored of Andrew Jackson, Protestant evangelicals enamored of the Wailing Wall, paleo-Catholics enamored of the fifth-century Church, gun lovers enamored of the nineteenth-century Wild West, hawks enamored of the twentieth-century cold war, isolationists enamored of the 1940s America First Committee, and acned young men waving around thick manifestos by a preposterous figure known as the Bronze Age Pervert. And they all get along.

The reason, I think, is that these usable pasts serve more as symbolic hieroglyphs for the right than as actual models for orienting action. That is why they go in and out of fashion unpredictably, depending on changes in the political and intellectual climate. The most that can be said is that the further to the right one goes, the greater the conviction that a decisive historical break is to blame for the loathsome present, and that accelerating decline must be met with…well, something. That’s when things get vague.

Rhetorical vagueness is a powerful political weapon, as past revolutionaries have understood. Jesus once likened the Kingdom of God to “leaven which a woman took and hid in three measures of flour, till it was all leavened.” Not terribly enlightening, but not terribly contentious either. Marx and Engels once spoke of a postrevolutionary communist society where one could hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, and write angry manifestos at night. After that they let the matter drop. Maintaining vagueness about the future is what now allows those on the American right with very different views of the past to share an illusory sense of common purpose for the future.

How, then, is one to understand the radical right today? Prior to the election of Donald Trump, the instinctive response of American liberals and progressives was simply not to try. Journalists who embedded themselves in far-right groups, or scholars who engaged seriously with their ideas, were often greeted with suspicion as agents provocateurs (as I can attest). That has changed. Today journalists cover many of the important groups and movements, and do a fairly good job of plumbing the lower depths of right-wing Internet chatter. Anyone who wants to know what is being said in these obscure circles, in the US and around the world, can now find out.

But keeping up with trends is not the same as understanding what they signify. What so often seems lacking in our reporting is alertness to the psychodynamics of ideological commitment. The great political novelists of the past—Dostoevsky, Conrad, Thomas Mann—created protagonists who make coherent ideological arguments that other characters engage with seriously but that also reveal something significant about their psychological makeup. …

These authors wrote the way good psychoanalysts practice their art in the consulting room. … They look at us through two different lenses: as inquiring creatures who sometimes find the truth, and as self-deceiving creatures whose searches are willfully incomplete, revealingly repetitive, emotionally charged, and often self-undermining. That is the skill required to begin understanding the leading ideological movements of our time, especially those on the right.

To my mind, the most psychologically interesting stream of American right-wing thought today is Catholic postliberalism, sometimes called “common-good conservatism.” The “post” in “postliberalism” means a rejection of the intellectual foundations of modern liberal individualism. The focus is not on a narrow set of political principles, such as rights. It is on an all-encompassing modern outlook that postliberals say prizes autonomy above all else and that is seemingly indifferent to the psychological and social effects of radical individualism. ….

This makes them highly susceptible to dreams of returning to premodern Christian social teachings that would undergird a more decent and just society, and more meaningful personal lives for themselves. This is a vain but not contemptible hope. … The postliberals see themselves as developing a more comprehensive view of the common good that integrates culture, morality, politics, and economics, which would make conservatism more consistent with itself by freeing it from Reaganite idolatry of individual property rights and the market.

Though Deneen is Catholic and teaches at Notre Dame, Why Liberalism Failed is not an explicitly Catholic book. To understand how distaste for the liberal present could make Catholicism psychologically appealing, it helps to read Sohrab Ahmari’s political-spiritual memoir, From Fire, by Water. Ahmari, a friend and ally of Deneen’s, was born a Muslim in Iran in 1985 and was brought to the United States by his educated parents at the age of thirteen. In his telling, he almost immediately came to disdain the “liberal sentimental ecumenism” in which he was being raised. He then became a serial converter, a type familiar to ministers. He was first an enthusiastic teen atheist, then an enthusiastic Nietzschean, then an enthusiastic Trotskyist, then an enthusiastic postmodernist, and finally a very enthusiastic neoconservative. (That’s a lot of bookshelves.) It was about this time that his writings came to the attention of The Wall Street Journal, and he was soon working on its editorial-page staff. …

Ahmari is a disarming writer. At one point in the book he asks, “Had I found in the Catholic faith a way to express the reactionary longings of my Persian soul, albeit in a Latin key?” He never answers that, though any fair reader could do it for him: Yes. … His latest project is Compact, a lively online magazine he cofounded and edits where antiliberals of left and right—from Glenn Greenwald and Samuel Moyn to Marco Rubio and Josh Hawley—display their wares. …

Vermeule is both more penetrating and intellectually radical than his friends Deneen and Ahmari, which gives his writings a Janus-faced quality. His academic books are learned and well argued, and have a place in contemporary constitutional debates, including Law and Leviathan: Redeeming the Administrative State (2020), which he wrote with his liberal colleague (and NYR contributor) Cass Sunstein. When writing online, though, he lets his id out the back door and it starts tearing up the garden. A little like radical Islamists who speak of peace in English but of war in Arabic, Vermeule has learned to adjust his rhetoric to his audience.

His most recent book, Common Good Constitutionalism, makes a challenging case for abandoning both progressive and originalist readings of the American Constitution and returning to what he calls the “classical vision of law.” … Rights matter in such a system, but only derivatively as means to achieve these ends. Liberty, in Vermeule’s view, is “a bad master, but a good servant” if properly constrained and directed. These are very old ideas, but Vermeule manages to breathe new life into them in a bracing way that will surprise conventional legal liberals and conservatives. For example, in a précis of the book’s argument published in The Atlantic, he writes:

Elaborating on the common-good principle that no constitutional right to refuse vaccination exists, constitutional law will define in broad terms the authority of the state to protect the public’s health and well-being, protecting the weak from pandemics and scourges of many kinds—biological, social, and economic—even when doing so requires overriding the selfish claims of individuals to private “rights.”

This is a book worth engaging with.

Such is the mainstream Vermeule. An angrier character appears in right-leaning journals like First Things and obscure websites of the Catholic far right. … In these writings, liberalism is not a mistaken political and legal theory, or even a mistaken way of social life. It is a “fighting, evangelistic faith” with an eschatology, a clergy, martyrs, evangelical ministers, and sacraments directed toward battling the conservative enemies of progress.

Their fire must be fought with fire.

Vermeule is a tired man—tired of waiting for change, tired of right-wing “quietism,” tired of merely being tolerated by the oppressive liberal order that says, “You are welcome to be a domestic extremist, so long as your extremism remains safely domesticated.” (Tip of the hat to Herbert Marcuse.) … Vermeule … has adopted the short-term strategy of encouraging people on the right to make a long stealth march through the institutions of government. … Just as Joseph insinuated himself into the Egyptian royal court to protect the Jews, so postliberals should embed themselves in bureaucracies and start nudging policy in the right direction, presumably until an antiliberal pharaoh takes charge (again).

Vermeule floated these cloak-and-dagger ideas in a critical review of his friend Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed in 2018. In that book Deneen still hoped to redeem liberalism by shoring up the moral foundations of local communities and educating the young in the priority of the common good. … Deneen took [Vermeule’s] challenge to heart and responds in his latest book, Regime Change, which reads like it was written by a different person. The tone of Why Liberalism Failed was one of regret, even mourning for something precious that had been lost. The new book tries to sound more radical but is so half-baked that at times it seems a parody of engagée literature, written in a kind of demotic Straussianism. Deneen echoes the old battle cry of counterrevolutionaries that “any undertaking to ‘conserve’ must first more radically overthrow the liberal ideology of progress.” The good news is that “the many”—which he also calls, without a trace of irony, “the demos”—are achieving class consciousness, but lack the knowledge and discipline to refine their anger into a program for governing. What they need are leaders who are part of the elite but see themselves as “class traitors” ready to act as “stewards and caretakers of the common good.” He calls this “aristopopulism” and its practitioners “aristoi.” (Garbo laughs.) It is a very old fantasy of deluded political intellectuals to become the pedagogical vanguard of a popular revolution whose leaders can be made to see a glimmer of the true light. Imagine a Notre Dame professor taking a stroll around the stoa of South Bend, Indiana, explaining to the QAnon shaman the scholastics’ distinction between ius commune and ius naturale, and you get the idea.

As far-fetched as the idea of right-wing aristoi making a long march through the institutions may seem, it is circulating at a time when Trumpian activists are using the same strategy to prepare for a battle against the “deep state” should Trump be elected again. The Heritage Foundation, for example, has contributed nearly a million dollars to Project 2025, which is amassing a database of roughly 20,000 trusted right-wingers who could be appointed to government positions immediately in a second Trump administration. …

This notion of social change having to come from the top is, in the Catholic tradition, a very papal one. In this sense, the postliberals writing today are papists in spirit even if they are not entirely enamored of the current pontiff. What is striking in their works is that they almost never speak about the power of the Gospel to transform a society and culture from below by first transforming the inner lives of its members. Saving souls is, after all, a retail business, not a wholesale one, and has nothing to do with jockeying for political power in a fallen world. Such ministering requires patience and charity and humility. It means meeting individual people where they are and persuading them that another, better way of living is possible. This is the kind of ministering the postliberals should be engaged in if they are serious about wanting to see Americans abandon their hollow, hedonistic individualism—not hatching plans to infiltrate the Department of Education.

Jesus implored his disciples to be “wise as serpents and harmless as doves” as they went out into the world to preach the Word. Deneen counsels postliberal moles to adopt “Machiavellian means to Aristotelian ends” in the political sphere. This is a very different gospel message and brings to mind Montaigne’s wise remark that “it is much easier to talk like Aristotle and live like Caesar than to talk and live like Socrates.” Ahmari, ever the hothead, addresses the troops in more militant language, exhorting them to

fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good…. Civility and decency are secondary values…. We should seek to use [our] values to enforce our order and our orthodoxy, not pretend that they could ever be neutral. To recognize that enmity is real is its own kind of moral duty.

Faith may move mountains, but too slowly for these Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Seen from a certain perspective, the postliberals do get a number of things right. There is a malaise—call it cultural, call it spiritual, call it psychological—in modern Western societies, reflected above all in the worrisome state of our children, who are ever more depressed and suicidal. And we do lack adequate political concepts and vocabulary for articulating and defending the common good and placing necessary limits on individual autonomy, from gun control to keeping Internet pornography from the young. On this many across the political spectrum could agree. What liberal or progressive today would reject Vermeule’s argument that “a just state is a state that has ample authority to protect the vulnerable from the ravages of pandemics, natural disasters, and climate change, and from the underlying structures of corporate power that contribute to these events”?

He, though, has a developed Catholic theory of government to explain why that is necessarily the case. Do liberals or progressives have one today? I know I don’t.

But seen from another perspective, the postliberals offer just one more example of the psychology of self-induced ideological hysteria, which begins with the identification of a genuine problem and quickly mutates into a sense of world-historical crisis and the appointment of oneself and one’s comrades as the select called to strike down the Adversary—quite literally in this case. As Vermeule puts it,

Liberalism’s deepest enmity, it seems, is ultimately reserved for the Blessed Virgin—and thus Genesis 3:15 and Revelation 12:1–9, which describe the Virgin’s implacable enemy, give us the best clue as to liberalism’s true identity.

He means Satan.

The postliberals are stuck in a repetition of mistakes made by many right-wing movements that get so tangled up in their own hyperbolic rhetoric and fanciful historical dramaturgy that they eventually become irrelevant. As long as their focus is on culture wars rather than spreading the Good News, these Catholics will inevitably meet with disappointment in post-Protestant secular America, where even the red-state demos demands access to pornography, abortion, and weed. The postliberals will perhaps get their own bookcase in the library of American reaction. But the rest of the American right will eventually be off in search of new symbols and hieroglyphs to dream its dreams.

My concern is for the young people drawn to the movement today. Their unhappiness with the lonely, superficial, and unstable lives our culture and economy offer them does them credit. But finding the true source of our disquiet is never a simple matter, for young or old. It’s much easier to become enchanted by historical fairy tales and join a partisan political sect promising redemption from the present than it is to reconcile oneself to never being fully reconciled with life or the historical moment, and to turn within. If I were a believer and were called to preach a sermon to them, I would tell them to continue cultivating their minds and (why not) their souls together, and to leave Washington to the Caesars of this world. And warn them that the political waters surrounding their conservative Mont-Saint-Michels are starting to smell distinctly like a sewer.