The Australian sense of humour …

Funny whether things work out or not … (And other things I encountered on my travels)

St. Nicholas Banishing a Storm: Merry Christmas

Another day in Australia

I once attended a dinner in which middle managers in the Department of Industry were farewelling a fellow bureaucrat on exchange from Sweden. At the end of a little speech that he gave, one of the Australian bureaucrats asked “Is there anything you think you still don’t understand about Australia”. The answer was “Yes, I don’t think I really understand your sense of humour.”

This was the subject of such immense and immediate mirth that it suddenly struck me that Australians’ very particular sense of humour is not just one of our characteristics. It’s completely central our sense of ourselves — and of course what they love about it. I’m not much enamoured of national naval gazing about the Australian character, but I loved this spontaneous affirmation of something we all shared. And the difficulty of sharing it with others gave it that much more cache.

It isn’t necessary that others don’t understand it but it does make it even funnier. Musing on this, it seemed to me that their unique sense(s) of humour of different British sensibilities are likewise quite central to their own sense of their identity in a way that simply isn’t true of — say Americans.

Meanwhile here’s an exchange that is so quintessentially Australian that it had me laughing out loud all on my own. The initiator of the exchange tries for a bit of matey banter, but alas things just go downhill from there. I like how things escalate with both parties knowing that they’re safe from gun-fire. You’d have to train yourself our of such indulgence in the US.

Enjoy:

A fine Christmas piece from Claire Lehmann

Not much in Paris is designed for new parents with babies, and the Louvre is no exception. We had to haul Eric and his pram up and down the stairs all day. When we were not hauling, Chinese tourists in the ladies’ bathroom would coo at him and take photos while I changed his dirty nappy.

Yet walking those palace halls as a new mother, I came to feel that I was witness to something remarkable. In room after room I was met by paintings of baby Jesus with his mother Mary—a mother-child dyad in which two figures exist in perfect harmony. The Louvre houses over a hundred paintings titled “Virgin and Child”. …

The earliest paintings from the medieval period start off flat and symbolic. … The formal, hierarchical arrangement speaks more of divine majesty than maternal tenderness. Just 120 years later, however, and we can see Botticelli depicting a level of emotional depth not previously seen in Western art. … Botticelli shows us Baby Jesus standing up on his mother’s lap, gazing up at her with the natural curiosity of an infant exploring his mother’s face. Mary meets his gaze, her soft cheek and comforting hands creating a cradle for her child’s movement. The sacred is no longer expressed through golden halos and formal arrangements, but through an intimate interaction between mother and child.

This new way of seeing the sacred through the lens of human experience reached its fullest expression in Raphael’s work, “La Belle Jardinière.” Mary sits in a meadow with two babies as opposed to one—Jesus and John the Baptist, who looks like he could be Jesus’s twin. Raphael depicts both babies with equal tenderness. There are no golden discs separating the holy child from his mortal playmate. In this painting, Mary does not appear as a remote queen of heaven, but an ordinary woman caring for children in a sunlit garden. In capturing the gentleness of Mary’s downward gaze, Raphael elevates the maternal to something transcendent. Raphael does not depict holiness through a golden halo, or formal religious pose, but in the simple unspoken bond between mother and child. Any mother, any child.

Does the elevation of the feminine exist in other artistic traditions? I don’t know. It seemed to me, sitting in the Louvre, with my baby in his woollen cocoon, that the Christian artistic tradition was unique in elevating motherhood to this central, venerated position. I am aware of other cultural traditions elevating goddesses and queens, and pagan traditions having icons of fertility. But what Raphael and Botticelli did was different. Through their art they made the vulnerability of infanthood sacred; the gentleness of femininity divine.

We live in a secular age, and I would consider myself a secular person. I’ve read books about the witch trials and persecution of heretics, and hold no romanticised views about organised religion. But I can tell you that as a new mother, seeing those images reflected on the walls of the Louvre made me feel an immense gratitude for our cultural history, as well as a sense that something important may have been lost. In my life, I have gained more recognition and prestige from being a columnist for The Australian, and founder of Quillette, than I ever have from being a mother—despite the latter being more important. …

This Christmas, my message is to remember what the Renaissance masters understood: that there is something worthy of reverence in the relationship between mother and child. While we may no longer seek the sacred in paintings, we can still see the simple truth that Raphael and Botticelli captured—in witnessing the care of a mother for her child we can look through a window into the sublime.

My visit to the Louvre has always stayed with me. Later on our Paris trip, while I was awkwardly breastfeeding Eric on cold concrete at the bottom of Montmartre, I felt connected to centuries of Parisian mothers who had come before me. Although I was not surrounded by a golden halo, and was not sitting in a sunlit garden, I felt that I had been recognised by those artists who had painted Mary.

This Christmas, if you are lucky enough to share it with your own mother or your children’s mother, please take a moment to honour her. And if you see a young mother wrangling a pram through a crowded space, remember that you are witnessing something that great artists once saw as worthy of their finest work—the everyday miracle of maternal love.

Bitcoin as an early-bird game

I’m not well read on Bitcoin, (though I bought some Bitcoin a while back). There’s certainly a lot of heat in lots of the online discussions. The people with the best take on these things ought to be economists, but a large number of economists aren’t very curious about things that require some original, critical thought. They may also be keen to show how Bitcoin illustrates their particular approach to this or that. (This or that will often relate to how ‘pro-market’ they fancy themselves.

For these reasons it’s worth keeping an eye on folks who are interested in Bitcoin and who have also interested themselves in the deeper discussions in economics about what money is (it’s a simple thing which is hard to understand). One such is JP Koning’s who maintains a blog called, tellingly ‘moneyness’ — a title you might want to investigate. In any event, here are extracts from a longish post documenting his changing views on Bitcoin. It’s rather unusual in that, though he bought a few bitcoin early on — and so must have made lots of money by most of our standards — he doesn’t seem very interested in that.

He’s interested in solving the problem of what kind of thing Bitcoin is. I’m no authority, but his answer and the policy implications he draws from it satisfy me — unless and until something more satisfying comes along.

An early bitcoin optimist

I was excited by Bitcoin in the early days of my blog. The idea of a decentralized electronic payment system fascinated me. … I was relatively open to Bitcoin for two reasons. First, I like to think in terms of moneyness, which means that everything is to some degree money-like, and so I welcome strange and alternative monies. "If you think of money as an adjective, then moneyness becomes the lens by which you view the problem. From this perspective, one might say that Bitcoin always was a money," I wrote in my very first post on bitcoin. Second, prior to 2012 I had read a fair amount of free banking literature—the study of private money—so I was already primed to be receptive to a stateless payments system, which is what Bitcoin's founder, Satoshi Nakamoto, originally meant his (or her) creation to be. …

Although Bitcoin excited me, I was also critical from the outset, and in later years my critical side would only grow. … In addition to my practical complaints about bitcoin, I also had theoretical gripes with it. The "lethal" problem as I saw it back in my second post in 2012 is that "bitcoin has no intrinsic value." Over the next decade this lack of intrinsic value, or fundamental value, would underly most of my criticisms of the orange coin. Back in 2012, though, the main implication of bitcoin's lack of intrinsic value was the ease by which it might fall back to $0. As I put it in a 2013 article:

"Bitcoin is 100% moneyness. Whenever a liquidity crisis hits, the only way for the bitcoin market to accommodate everyone's demand to sell is for the price of bitcoin to hit zero—all out implosion".

But if the price of bitcoin were to fall to zero then it would cease to operate as a monetary system, which would be a huge disappointment to those of us who were fascinated with Satoshi's electronic cash experiment. Adding to the danger was the influx of bitcoin lookalikes, or altcoins, like litecoin, namecoin, and sexcoin. In theory, the prices of bitcoin and its competitors could "quickly collapse in price" as arbitrageurs create new coins ad infinitum, I worried in 2012, eating away at bitcoin's premium. The alternative view, which I explored in a 2013 post entitled Milton Friedman and the mania in copy-paste cryptocoins, was that "the earliest mover has superior features compared to late moving clones," including name brand and liquidity, and so its dominance was locked-in via network effects. Over time the latter view proved to be the correct one. …

If not money, then what is bitcoin?

By 2017 or so, even the most ardent bitcoin advocates were being forced to acknowledge that Satoshi's electronic cash system was not panning out: the orange coin was nowhere near to becoming a popular medium-of-exchange. … But if bitcoin was never going to become a generally-accepted form of money, and it wasn't a store-of-value or digital gold, then what exactly was it?

I didn't nail this down till a 2018 post entitled A Case for Bitcoin. We all thought at the outset that bitcoin was a monetary thingamajig. But we were wrong. Of the types of assets already in existence, bitcoin was not akin to gold, cash, or bank deposits. Rather, it was most similar to an age-old category of financial games and zero-sum bets that includes poker, lotteries, and roulette. The particular sub-branch of the financial game family that bitcoin belonged to was early-bird games, which contains pyramids, ponzis, and chain letters. …

Early-bird games like pyramids, ponzis, and chain letters are a type of zero-sum game in which early players win at the expense of latecomers, the bet being sustained over time by a constant stream of new entrants and ending when no additional players join. Pyramids and ponzis are almost always administered by thieves who abscond with the pot. Bitcoin, by contrast, was not a scheme nor a scam. And it was not run by a scammer. It was leaderless and spontaneous, an "honest" early-bird game that hewed to pre-set rules. …

Bitcoin is innocuous, don't ban it

By 2020 or 2021, the commentary surrounding bitcoin seemed to be getting more polarized. Arrayed against [Bitcoin zealots] was a new group of strident opponents who though bitcoin was incredibly dangerous and were pushing to ban it. I was at odds with both sides. … I conceived of it as an innocuous gambling device, one that only seemed novel because it had been transplanted into a new kind of database technology, blockchains. We shouldn't ban bitcoin for the same reason that we've generally become more comfortable over the decades removing prohibitions on online gambling and sports betting. Better to bring these activities into the open and regulate them than leave them to exist in the shadows.

The failure of bitcoin to serve as an effective tool for funding the illegal Ottawa protests … underlined its low threat potential. … “As long as the on-ramping and off-ramping process are regulated, these fears are overblown."

So when does bitcoin get dangerous

… If you want to buy some bitcoins, go right ahead. We can even help by regulating the trading venues to make it safe. But don't force others to play. Alas, that seems to be where we are headed. There is a growing effort to arm-twist the rest of society into joining in by having governments acquire bitcoins, in the U.S.'s case a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve. The U.S. government has never entered the World Series of Poker. Nor has it gone to Vegas to bet billions to tax payer funds on roulette or built a strategic Powerball ticket reserve, but it appears to be genuinely entertaining the idea of rolling the dice on Bitcoin.

Bitcoin is an incredibly infectious early-bird game, one that after sixteen years continues to find a constant stream of new recruits. … Although I never wanted to ban Bitcoin, I can't help but wonder whether a prohibition wouldn't have been the better policy back in 2013 or 2014 given the new bitcoin-by-force path that advocates are pushing it towards. But it's probably too late for that; the coin is already out of the bag. All I can hope is that my long history of writing on the topic might persuade a few readers that forcing others to play the game you love is not fair game.

MAD Architects: a recent creation

International studio MAD Architects has unveiled the One River North apartment block in Denver, Colorado, which has a large, canyon-like opening breaking open its main facade. Named One River North, the residential block in Denver's northern RiNo neighbourhood was designed as a nod to geographic formations in the nearby Rocky Mountains.

Can Gifted Education Help Higher-Ability Boys from Disadvantaged Backgrounds?

David Card, Eric Chyn, and Laura Giuliano

Boys are less likely than girls to enter college, a gap that is often attributed to a lack of non-cognitive skills such as motivation and self-discipline. We study how being classified as gifted – determined by having an IQ score of 116 or higher – affects college entry rates of disadvantaged children in a large urban school district. For boys with IQ’s around the cutoff, gifted identification raises the college entry rate by 25-30 percentage points – enough to catch up with girls in the same IQ range. In contrast, we find small effects for girls. Looking at course-taking and grade outcomes in middle and high school, we find large effects of gifted status for boys that close most of the gaps with girls, but no detectable effects on standardized tests scores of either gender. Overall, we interpret the evidence as demonstrating that gifted services raise the non-cognitive skills of boys conditional on their cognitive skills, leading to gains in educational attainment.

Mary Harrington confirms what we all know

Memes can be useful, but do not contain life

Mary Harrington transitioned from reflexive left to right when she noticed her leftist memes didn’t fit her experience as a mother. Here she is reporting on someone who was her counterpart on the right. She’s transitioned too, noticing that adherence to dogmatic ideas from the right don’t map any more usefully onto domestic life as a mother either. Whodda thunk?

No doubt I’ve quoted it before, but I can’t resist doing so again — from Heinz Arndt’s autobiographical essay:

In my own case, these political prejudices (if not, I would like to think, the moral convictions) underwent great changes over half a century, from a brief youthful Marxist phase to decades of Fabian-Keynesian views which gradually gave way to … a sceptical – monetarist near-libertarian position … It might be thought that such an odyssey would induce a decent humility: if I could be so completely wrong earlier what grounds of confidence have I that I am right now? I can only shamefacedly report that this has not been my experience.

I found the article quite interesting, but after about 800 words, didn’t think I was learning much and moved on.

One of the very first columns I wrote at UnHerd, back in 2019, described how, for me, becoming a mum meant giving up on a great deal of the liberal ideology I’d embraced when younger — because it was impossible to square with the embodied reality of caring for a baby. A relatively conventional home life turned out to be much more fulfilling than the radical one I’d adopted with my progressive politics.

My accounts of questioning this individualistic ideology, and embracing marriage and motherhood have resonated with social conservatives. Most of these, it goes without saying, feel (as I do) that family life and women’s distinctive sexed realities should be better understood and valued in the public conversation. Some, though, take more hardline positions: that women should never work, for example, that we should always be submissive — or even that women’s right to vote should be repealed.

But surely any stance which risks lending momentum to such extreme arguments cannot be in women’s interests? I explored this question recently with the Canadian Right-wing firebrand Lauren Southern, whose early video content regularly challenged liberal feminist orthodoxy, and promoted domesticity. Our stories are symmetrical in some respects: both of us embraced radical politics in our early twenties, me on the Left and Southern on the Right. Both of us embraced ideologies that felt inspiring in the free-floating world of the internet. And both of us, albeit in different ways, have course-corrected back toward reality in part via the fiercely practical experience of caring for a child.

Southern’s story might easily serve as a cautionary tale for how socially conservative talking-points can lead women into danger. For where I lost my twenties to commune life and niche sexualities, she left media at 22 to embrace a socially conservative template for women: the lifestyle often idealised by social media influencers as “tradwife”. Except it wasn’t all Fifties pinafores and cute cupcakes; it was a living hell. Nor, as she has learned, was she the only conservative woman in this position.

Comparing our experiences, though, two things emerge. Firstly, that this is not simply a matter of the Right being uniquely toxic for women — though, as Southern’s story reveals, there’s plenty of scope for toxicity. It’s rather that purist ideologies as such map at best uneasily onto the practical realities of life as a woman – and especially as a mother. And secondly, that the simplifying, polarising incentives baked into the contemporary internet are increasingly warping the ideologies of both Left and Right into such extreme forms, that any sincere effort to apply these in real life will almost inevitably be the stuff of nightmares. …

I doubt online “gender” arguments will abate any time soon. The tussle between men and women is a culture war as old as humanity itself: men and women always need to find a way to live together, which means negotiating those ways our material interests and physical capacities align or exist in tension. With the wider world in flux, it’s hardly surprising to find ourselves here again; the challenge is finding solutions that are grounded in reality rather than abstract, purist ideologies.

But the internet’s first generation of natives may be the ones who bring us back down to earth. Even the erstwhile queen bee of the extremely online radical Right is now a convert to “living in reality”. So perhaps there’s hope that the rest of us — and our politics — will also find our way back there, in the end.

Other contenders to illustrate the insufficiency of memes

The prompt I used to generate the previous AI illustration tried out on various alternative AI platforms. For your interest, if not necessarily delectation.

Christmas with the Wagners

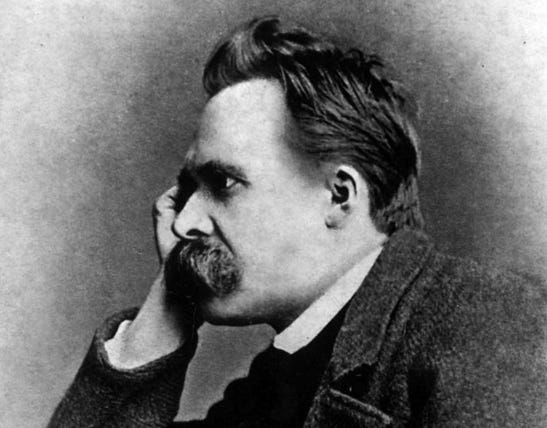

I didn’t know Nietzsche was a medical orderly in the Franco-Prussian War. But I do now. Not much use, but there you go. He was better at other things.

In 1870, Nietzsche was 26. He had recently been promoted to full professor at Basel University when the Franco-Prussian war broke out. This presented him with a moral dilemma. Basel being in Switzerland, the university wanted him to stay in his teaching job. But Nietzsche, being German, felt it his duty to defend his country despite his loathing of mindless German nationalism. “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, that is the end of German philosophy!” he wrote. He absolutely did not want to fire cannonballs against France, a country whose culture and philosophy he loved dearly. His compromise was to volunteer to go to the front as a medical orderly. Nursing the wounded and dying on the battlefields, he caught dysentery and diphtheria simultaneously, and was invalided out.

During his recovery, he was invited to spend Christmas with Richard and Cosima Wagner in their elaborate mansion on Lake Lucerne. Nietzsche was in love with Cosima, who had married Wagner while Nietzsche was at war. The daughter of Franz Liszt, Cosima was terrifyingly effective; capable even of dominating the notoriously libidinous Wagner. When Nietzsche had volunteered for war, stern Cosima had briskly told him that “a gift of a hundred cigars would be more use to the army than the presence of a dilettante,” a remark that made him adore her all the more.

Now, on his return from the battlefield, Nietzsche had grown in the eyes of his hosts into the heroic philosopher-warrior. He accepted their invitation without realising that his wartime experience had in fact opened a chasm between them that would eventually widen into a full-blown rift. War left Nietzsche committed to European cooperation, while it stoked Wagner and Cosima’s blazing, vengeful, nationalism. Wagner—who spoke French perfectly well—was refusing even to read letters sent to him written in French.

On Christmas morning, ravishing sounds came pulsing through the scented air of the house. Wagner had secretly smuggled Hans Richter and a 15-piece orchestra on to the staircase where they played a glorious piece of music for the very first time. It was the Siegfried Idyll, Wagner’s sublime symphonic poem composed to celebrate Cosima giving birth to his only son, Siegfried, named after the human hero of Wagner’s epic Ring cycle.

Cosima writes in her diary that on hearing the music wafting up the stairs, she exclaimed; “Now let me die.” “It would be easier,” Wagner answered, “to die for me than to live for me.”

The exchange was typical of the elevated plane on which conversations were exhaustingly and unrelentingly conducted in the Wagner household, often punctuated by sobs, tears and one or other falling to their knees. The Siegfried Idyll, Cosima wrote, transported her into “a waking dream, a euphoric melting of boundaries, an unawareness of bodily existence, supreme happiness and the highest bliss.” She felt as if she had at last attained the Schopenhauerian goal of dissolving the boundaries between Will and Representation, between the material world and the ideal.

Wagner and Cosima were giving no gifts this Christmas. The gesture was a tribute to those still experiencing the hardships of war. Nietzsche had not been forewarned of this sensibility. He arrived laden with gifts. For Wagner he had thoughtfully chosen a copy of Dürer’s great engraving The Knight, Death and the Devil, an image that since its creation in 1513 had been taken as a nationalist rallying point, a significant symbol of German faith and German courage in adversity. Wagner accepted it with great pleasure. Never a stranger to vanity, he saw it as a picture of himself: the composer riding to the rescue of pure German culture, mounted on his “Music of the Future,” Zukunftsmusik, his nation’s true music that, he felt, had been derailed by foreign composers like Offenbach (French) and Meyerbeer (Jewish). Both composers—maddeningly—far more popular than himself. Nietzsche had chosen his present well. It fed Wagner’s idea of himself as the knight whose lance would slay the dragon of multiculturalism.

Cosima was also delighted with her Christmas gift from Nietzsche: the manuscript of The Birth of the Tragic Concept, an early draft of the philosopher’s own The Birth of Tragedy. In the evenings, Wagner read passages aloud. Wagner and Cosima praised it as being “of the greatest value and excellence.” Nietzsche purred.

Nietzsche was the only guest. He stayed eight days. One evening he read out his essay on the Dionysian attitude, which they then discussed. Another, Wagner read out the libretto for Die Meistersinger. One day when Wagner was out, Hans Richter played the ravishing music from Tristan und Isolde for Nietzsche and Cosima alone. They discussed the comparative merits of Hoffmann and Edgar Allan Poe, and this led them to agree on the profundity of the idea of looking upon the real world as unreality, an attitude which Schopenhauer remarks is the mark of philosophical capacity.

On New Year’s Day 1871, Nietzsche left them to return to Basel. The month of January was depressing. The Franco-Prussian war continued in all its brutality. France was crushed. On 18th January, Kaiser Wilhelm was proclaimed emperor of a united Germany—in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, of all places. France’s humiliation was complete. Wagner and Cosima rejoiced. Nietzsche was utterly miserable. Away from Wagner and Cosima, he experienced the full conflict between his love for them and his convictions. It would take him some years to summon the strength to jump over the abyss of moral hypocrisy. The choice between love and idealism has never been easy, even for a philosopher.

Lots of far right parties have moderated.

The AfD? Not so much, but Elon hasn’t got the memo.

Noah backs a three state solution

Well blow me down!

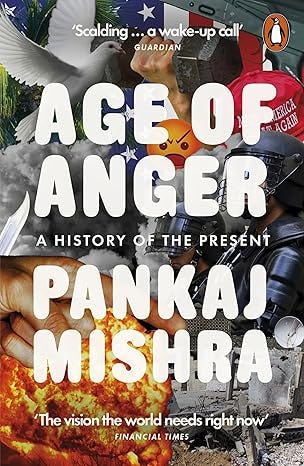

Fruitcake watch: Age of Anger edition

I’ve now finished reading The Age of Anger. I love history of ideas books and I enjoyed reading this. The central argument in this book is well summarised by Wikipedia.

Mishra notes that disorder and violence naturally accompanied the coming of industrial capitalism in the Western world, citing events such as the French Revolution, the Revolutions of 1848, and two World Wars. He argues that the rest of the world is now undergoing that same series of shocks and that new tensions resulting from the Enlightenment are not yet resolved even in Europe. He criticizes the view that early-twentieth-century strife was an aberration interrupting a long history of steady progress and increasing prosperity, instead arguing that disorder is endemic to modernity. In the first half of the book Mishra dwells on the dispute between philosophers Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who lived during the eighteenth century when Enlightenment ideals and economic, political, and social liberalism began gaining momentum in Europe. According to Mishra, Rousseau was among those who best anticipated the problems modernity would bring: rootlessness, competition, and materialism.

Though I think the book’s basic argument is an important and worthwhile one, and at the very least a good corrective to existing narratives, Mishra is too easy on himself, too incurious about alternative ways one might react to the material he presents. I ended up agreeing with Franklin Foer’s review "It's bracing and illuminating for him to focus on feelings, what he calls 'the wars in the inner world.' But he doesn't have much to say about the material reality of economics and politics other than angry bromides about the 'Western model' and broad, unsupported statements about stagnation”.

In any event, one thing that never left me was the strife Western intellectuals have made for their societies since at least the romantics of the turn of the 19th century. Young men with striking, often brilliant ideas, so fall in love with those ideas that they imagine that their diagnosis, or their contribution can transform society, healing it and transporting it, often into some utopian state.

The newly united nation of Germany offered a particularly virulent case.

Finding the Enemy Within

As Romanticism metamorphosed into grand proclamations about the spirit of history (and its fondness for Germany), Heine warned against ‘that vague, unfruitful pathos, that unprofitable vapour of enthusiasm, which plunges, scorning death, into an ocean of generalizations’. Shorn of his earlier hopes, Heine became Germany’s most acute critic as the country’s slow progress under a conservative regime incited grandiloquent daydreams of power among the intellectuals. As he then wrote, ‘The French and the Russians rule the land, / Great Britain rules the sea, / But we’re supreme in the realm of dreams, / Where there’s no rivalry.’

Heine keenly sensed Romanticism’s disturbing mutations. In ‘Atta Troll’ (1841) a bear dancing vigorously and ineptly represents the Young Germany:

Atta Troll, trend-conscious bear, respectably

Religious, ardent as a companion,

Through seduction by the Zeitgeist

A sansculotte of the primeval forest.

Dances very badly, yet with

Conviction in his shaggy bosom.

Also pretty stinky on occasion.

No talent, but a character.The Jewish poet was an early critic of nationalism, having noticed its malign dependence on various enemies for self-definition: ‘The French-devourers,’ he wrote, ‘like to gobble down a Jew afterwards for a tasty dessert.’ He attacked the book-burners at the Wartburg ceremony of 1817:

Dominant there was that Teutomania that shed so many tears over love and faith, but whose love was no different than hatred of the foreigner and whose faith lay only in stupidity and could, in its ignorance, find nothing better to do than to burn books!

Heine went after the solemn intellectual defenders of nationalism, the German philosophers and historians who ‘torture their brains in order to defend any despotism, no matter how silly or clumsy it may be, as sensible and authentic’. His defiant Francophilia, and contempt for German nationalists, exposed Heine to anti-Semitic attacks. The most formidable of his critics after 1871 was Heinrich von Treitschke, a kind of intellectual spokesman for unified and rising Germany with his patriotic histories. In 1807, Fichte had already floated the possibility of expelling unassimilated Jews. Treitschke made anti-Semitism respectable in Bismarck’s Second Reich with an article that began with the words, ‘The Jews are our national misfortune.’ He deplored the fact that Heine ‘never wrote a drinking song’ and ‘of carousing in the German way the oriental was incapable’. ‘Heine’s esprit,’ he concluded, ‘was by no means Geist in the German sense.’

* * *

Treitschke was trying to name and shame un-German Orientals when Germany had become a unified nation state, and its material and political conditions had vastly improved. For a long time only some bookish Germans had been even interested in a national state, despite the best efforts of various freelance revolutionaries. The misery of peasants and factory workers had bred passive acceptance rather than political resistance, let alone revolutionary rage – a fact that continually frustrated Marx and pushed him into increasingly radical hopes. Francophobia acquired a mass base only in 1840, when France demanded the surrender of German territories on the left bank of the Rhine.

Soon after its unification, Germany surpassed France, defeating its old tormentor militarily in 1871 with the help of new railways and telegraphy networks. German troops bombarded and occupied Paris, and the subsequent violent chaos of the Paris Commune made Germany seem to many in the French elite a worthy model of national emulation. Germany also started to close in on Britain with a belated but extensive industrial revolution. Germans who had contented themselves by daydreaming about their intellectual and spiritual leadership could now boast about an imperial Second Reich. And intellectuals like Treitschke exercised far more influence in a unified Germany than they ever had in the past.

After a wild burst of enthusiasm, however, the messianic hopes generated by German unity soon came up against the soulless realpolitik of Bismarck and the prosaic reality of an industrializing country. ‘German spirit,’ Nietzsche epigrammatically noted in 1888, ‘for the past eighteen years, a contradiction in terms.’ It was also Nietzsche who had observed previously and perceptively that ‘once the structure of society seems to have been in general fixed and made safe from external dangers, it is this fear of one’s neighbour which again creates new perspectives of moral valuation’.

An existential envy of neighbours lingered in unified Germany while the achievement of material success brought tormenting ambivalence in its wake to people who had boasted a great deal of their spiritual culture. Germans seemed less united, and more disconnected from their glorious traditions, than before as they laid railways, built up cities and made money. The gap between organic German Kultur and mechanistic Western Zivilisation seemed to shrink. Many modernizing Germans seemed to resemble too much the unbridled plutocrats and profit-seekers of England, France and the United States.

Self-distrust led to more boosting of the Volk, and the fantasy that the people rooted in blood and soil would eventually triumph over rootless cosmopolitans, confirming Germany’s moral and cultural superiority over its neighbours. Thus, Germany generated a phenomenon now visible all over Europe and America: a conservative variant of populism that posits a state of primal wholeness, or unity of the people, against transnational elites, while being itself deeply embedded in a globalized modern world.

* * *

Self-hatred expanded into hatred of the ‘other’: the bourgeois in the mirror. In German eyes, the West was increasingly identified with soulless capitalism, and England replaced France as the embodiment of the despised bourgeois world, followed by the United States. As Treitschke wrote: ‘The hypocritical Englishman, with the Bible in one hand and a pipe in the other, possesses no redeeming qualities. The nation was an ancient robber knight, in full armour, lance in hand, on every one of the world’s trade routes.’ The United States became the ‘land without a heart’, another heir of the ultra-rational Enlightenment.

But the main embodiment of Western moral degeneracy and treachery was the Jew. Whether capitalist modernization boomed or went into crisis (which it did severely in Germany in 1873), the Jews were to blame. Anti-Semitism, notwithstanding its long historical roots, served a frantic need to find and malign ‘others’ in the nineteenth century; it acquired its vicious edge in conditions of traumatic socio-economic modernization, among social groups damaged by technical progress and capitalist exploitation – small businessmen, shopkeepers and the artisan classes as well as landlords – and then condescended to by their beneficiaries. This was not traditional Jew hatred in a new guise, as the first generation of Zionists, all assimilated and self-consciously European Jews, recognized, if much too slowly.

Theodor Herzl was a proud German nationalist, a fraternity and duelling enthusiast no less, until he found himself drowning under the anti-Semitic tide of the 1890s. By then religious prejudice had been transformed, with considerable help from Darwinian notions of natural selection and evolutionary progress, into racial prejudice. Alienated and confused Germans had started to define their hope for stability and solidarity by identifying and persecuting the apparent disruptor of the Volk: the unassimilable and biologically different Jew with conspiratorial cravings to undermine their civilization.

By inventing a mythical evil in the form of the rootless Jew, and finding a basis for it in modern science, the anti-Semites could transcend all manner of social conflicts and ideological contradictions, and stave off anxieties about their own status. A classic anti-Semite in this sense was the famous Orientalist Paul de Lagarde, a university careerist like many exponents of Volk ideology, whose personal resentment of the academic establishment – he had received his professorship only late in life – inflated into disappointment at the spiritual failures of Bismarckian Germany. Nietzsche correctly called him a ‘pompous and sentimental crank’. Such prophets enumerating the discontents of a commercial and urban civilization, warning against the loss of values, and exhorting a spiritual rebirth of Germany, successfully mixed cultural despair with messianic nationalism. They influenced two generations of Germans before Hitler.

Hating the Modern While Loving the People

Austria-Hungary produced the most powerful anti-Semitic demagogues. It had entered capitalist modernity late, and with terrible consequences for its traders and artisans. A socially insecure as well as economically marginal lower middle class aimed its ressentiment at the liberal elite. Consisting of the propertied bourgeoisie and assimilated Jews, the liberals quickly conceded the political initiative to petit-bourgeois demagogues.

For much of the 1880s a harsh new political language was articulated by Georg von Schönerer, who incited lower middle-class ethnic Germans against what he described as ‘the Jewish exploiters of the people’ – the so-called ‘exploiters’ including Jewish peddlers as well as bankers, industrialists and big businessmen. He introduced two major anti-Semitic laws, modelling them on the Californian Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (then, as now, racists, anti-Semites and chauvinist nationalists feverishly cross-pollinated).

Fin de siècle Vienna, which elected an anti-Semitic mayor in 1895 and where both Hitler and Herzl spent their formative years, was a hothouse of venomous prejudice. (Freud developed his theory of psychological projection while observing the city’s paranoid inhabitants.) The most disturbing case, however, of the lurching German spirit in the nineteenth century was of the diabolically gifted Wagner.

His rise to fame coincided with Germany’s much-heralded ascent to great-power status, and its resulting self-doubts. Like Herder, Wagner had left Riga out of frustration to find fame and fortune in Paris (where he briefly became friends with Heine). Poverty, neglect and misery in the French capital, where the Jewish composer Meyerbeer reigned supreme in musical circles, roused Wagner to an abiding hatred of the city: ‘I no longer believe,’ he wrote in 1850, ‘in any other revolution save that which begins with the burning down of Paris.’ Wagner left Paris in 1842 after Rienzi, his early Romantic opera about a failed revolutionary, became a pan-European hit (one enraptured teenage viewer would be Adolf Hitler in 1906). But his exalted duties as a court Kapellmeister in Dresden left him deeply dissatisfied. As an artist with a high sense of his calling, he found himself humiliatingly beholden to bourgeois plutocrats.

Identifying the comfortable opera-going philistines of the bourgeoisie as the cause of all evil, Wagner deprecated parliaments and hoped that revolution would bring forth a leader capable of lifting the masses to power, to unscaled aesthetic heights, while creating a new German national spirit. He found his true calling as revolutions broke out across Europe in 1848. ‘I desire,’ he wrote, ‘to destroy the rule of the one over the other … I desire to shatter the power of the mighty, of the law, and of property.’ Eager to merge his excitable self in what he called ‘the mechanical stream of events’, he found an eager companion in Bakunin, who, a year younger than Wagner, was then beginning on his own long journey as the exponent of anarchism.

While Karl Marx fled the Continent in 1849 to his final refuge in England, Wagner manned the barricades of Dresden (helping, among other things, to procure hand grenades). Bakunin suggested that he write a terzetto, the tenor singing ‘Behead him!’, the soprano ‘Hang him!’ and the bass ‘Fire, Fire!’ Wagner got his thrills when the opera house where he had lately conducted Beethoven’s democratic Ninth Symphony went up in flames (he was later accused of causing the fire). But the uprising was crushed, and Wagner had to flee to Zurich in a hired coach, subjecting Bakunin and other solemn-faced companions to demonic cries of ‘Fight, fight, forever!’

* * *

The German Romantics had wished to found with their art a new communal vision to offset the social divisions of economic utilitarianism and individualism. Wagner inherited this ambition, along with their Teutonic legends and mythologies, and then inflated them into a magnificent vision of Germany’s spiritual and cultural regeneration. He mixed art with politics to devastating effect, decades before D’Annunzio, and came to embody the Romantic Revolution at its most prophetic – and megalomaniacal – in his attempt to replace God with modern man.

The process inaugurated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – whereby man replaces God as the centre of existence and becomes the master and possessor of nature by the application of a new science and technology – had reached a climax by the middle decades of the nineteenth century. The view of God as only an idealized projection of human beings rather than a Creator had taken hold among the European and Russian intelligentsia well before 1848. Among writers and artists trying to create new values without the guidance of religion, Wagner loomed largest in his attempt to construct a new mythos for human beings.

In these gigantic projects, Wagner gave his art a starring role. In his view, the artist, degraded by capitalism and bourgeois philistines, ought to be the high priest of the nation. Instead he was producing ‘entertainment for the masses, luxurious self-indulgence for the rich’. A new social bond was needed among the masses, and between the masses and the poet. Between 1848 and 1874, Wagner achieved a synthesis of theory and practice in writing the libretto and music for The Ring of the Nibelung, which was performed in full two years later at the opening of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (where one of the attendees was Nietzsche).

The Italian Futurist Marinetti, who hated the ‘insupportable platitudes’ of Puccini’s operas, called Wagner ‘the greatest decadent genius and therefore the most appropriate artist for our modern souls’. The cult of Wagner was pan-European, cutting across national and ideological lines. Hitler claimed that he got his Weltanschauung from his early exposure to Wagner’s Rienzi: ‘It began at that hour.’ Herzl wrote his groundbreaking manifesto of Zionism, The Jewish State (1895), in constant proximity in Paris to the anti-Semite’s music, confessing that ‘only on those nights when no Wagner was performed did I have any doubts about the correctness of my idea’. Marinetti claimed that Wagner ‘stirs up the delirious heat in my blood and is such a friend of my nerves that willingly, out of love, I would lay myself down with him on a bed of clouds’.

Wagner’s European eminence signified the much-awaited triumph of German spiritual culture over its old materialistic and corrupt bourgeois adversary, the French. However, the man himself, at the height of his fame, was still tormented by his humiliation in Paris, where the fascination of this provincial with luxurious metropolitan life had ended in partial success and scandal. He wrote an ode while German armies were encircling Paris in 1871, and a one-act play when they conquered and occupied the city. Soon he was verifying Heine’s fear that Francophobia’s flip side is anti-Semitism.

Meyerbeer, his rival in Paris, seemed to Wagner proof that the moneymaking Jew had infected the cultural realm: ‘In the present state of the world the Jew is already more than emancipated: he rules, and will rule as long as money remains the power that saps all our acts and undertakings of their vigour.’ It was essential, Wagner wrote in his essay ‘Know Thyself’, that German folk achieve self-knowledge, for then ‘there will be no more Jews. We Germans could … effect this great solution better than any other nation.’

Nietzsche famously broke with Wagner over the latter’s progressively demagogic nationalism. In his earliest writings, Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche had criticized the Bildungsphilister, the cultivated philistine, the embodiment of the narrow-minded intellectuals and educated nationalists rising to the fore in the new Germany. He had attacked, too, the popular culture and literature that had started to cater to the ‘desperate adolescents’ of Young Germany.

The spectacle at Bayreuth of the great composer administering musical thrills to the Bildungsphilister by celebrating the pompous, nationalistic Reich eventually repelled Nietzsche (so much so that he fled from the assembled Wagnerians to a nearby village). In Nietzsche’s view, materialism and loss of faith were generating a bogus mysticism of the state and nation, and dreams of utopia. Describing Bismarck as a ‘fraternity student’, he lamented ‘Germany’s increasing stupidity’ as it descended into ‘political and nationalistic madness’. He also used the Germans to indict a broader complacency in Europe: its investment in liberal democracy, socialist revolution and nationalism. Nietzsche kept insisting until his lapse into insanity that his peers – the thinkers and doers of his time – had failed to recognize the consequences of the ‘death of God’: ‘There will be,’ he warned, ‘wars the like of which have never been seen on earth before.’ Nietzsche’s hero, Heine, had even fewer illusions about his compatriots. He wrote the most prophetic words of the nineteenth century: ‘A play will be performed in Germany which will make the French Revolution look like an innocent idyll.’

The Identity Politics of the Elite

Heine believed that ‘Teutomania’ had irrevocably blighted Germany’s political and intellectual culture; he died too early to see that the German habit of idealizing one’s country for its own sake would afflict educated minorities everywhere.

Unlike in France and England, where political citizenship and civil nationalism were the norm, the Germans had upheld immersion in the Volksgeist. The long years of political disunity had made a shared culture seem the matrix for a future nation. For young men elsewhere lacking both a state and a nation, this primarily cultural definition of nationality, and promise of a spiritual community, came to be deeply seductive. It flourished among them since it was not only able to fill an aching inner emptiness; it could also give actual employment and status to an educated but isolated class.

From its ranks emerged – everywhere – the prophets and the first apostles of nationalism. Indeed, nationalism, like the Enlightenment, was in its early stages almost entirely a product of men of letters. These energetic and ambitious men took it upon themselves to convince their respective Volk that its best interests lay in transcending sectarian interests and unifying, preferably under their command. They transformed their pursuit of personal identity and dignity into a chivalrous defence of what they saw as collective identity and dignity.

Men of letters had prepared the emotional and intellectual climate for the French Revolution. In the eighteenth century, the language of politics, according to Tocqueville, had taken ‘on some of the character of the language spoken by authors, replete with general expressions, abstract terms, pretentious words, and literary turns of phrase’. Literary writers, imaginary (Ossian clones) as well as deskbound ones, went on to play a central role in nineteenth-century nationalism as members of tiny educated minorities. In particular, poets, often in exile, managed to exalt, with their lyrical power, the amorphous fantasies of self-aggrandizement into the principles of nationhood.

Poetry has never been so widely and keenly read as it was in the early nineteenth century. ‘People and poets are marching together,’ the French critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve wrote in 1830. ‘Art is henceforth on a popular footing, in the arena with the masses.’ This was surely a poetic exaggeration. Poets, however, encouraged such political readings of their work, envying Walter Scott, who had practically invented Scotland with his ground-breaking ethnic lore and historical local colour. Poetry’s connection with prophecy was repeatedly underlined, not least by Pushkin, whose fascination with the Prophet Mohammed’s ability to move people with the power of his words alone produced in 1824 a cycle of poems: Imitations of the Quran. This calls for resistance to oppression while blending Pushkin’s own persecution and exile with that of the founder of Islam.

Appropriately, the most famous of poet-prophets came from a country that had ceased to exist in the late eighteenth century: the Pole Adam Mickiewicz. Such stateless nationalists managed to construct through nationalism a network of power – resembling that of the French men of letters during the eighteenth century – against obsolete and iniquitous hierarchies at home. People who felt their societies to be politically backward and apathetic also learned to mine consolation in this demoralizing feeling: ‘In history,’ even the liberal-minded Herzen asserted, ‘the latecomers receive not the leavings but the dessert.’

* * *

Russians, this reader of Schiller and Schelling declared, were better placed than the Germans to be the guide and saviour of humanity. For many Slavophiles in Russia, too, the true Russian way was not Western-style abstract individualism, but the peasant commune built on a sense of community in church and society. Those vulnerable to the immense soft power of German philosophy – Italians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Poles – devised their own cultural-linguistic nationalism, marked by resentment and frustration. Soon, the Japanese fell under its spell, followed by other Asians. No educated minority was more thoroughly ‘Germanized’ than the Japanese in the nineteenth century. Close readers of Fichte abounded at all levels of Japan’s state and society. By the early twentieth century, many Japanese thinkers became as frantic about defining ‘Japaneseness’ – Japan’s evidently absolute spiritual and cultural difference from the West – as about championing strict state control of domestic society, and enforcing conformity in thought and conduct.

Philosophers of the Kyoto School such as Nishida Kitaro and Watsuji Tetsuro made ambitious attempts to establish that the Japanese mode of understanding through intuition was both different from and superior to Western-style logical thinking. As with the Germans, this was no mere conceit of ivory-tower dwellers; clear identification of the other as inferior was essential to building up internal unity and confidence for Japan’s inevitable and final showdown with its enemies. The Kyoto School provided the intellectual justification for Japan’s brutal assault on China in the 1930s, and then the sudden attack on its biggest trading partner in December 1941 – at Pearl Harbor.

Thus, the concepts discovered on Herder’s trip to France, and during the larger German recoiling from metropolitan society and quest for Kultur, were adapted to different conditions and traditions. Each ‘wounded’ people defined their unmediated sense of belonging unreservedly in terms of their own ‘people’, religious community or ethnic group. Just as German writers had sought to re-create archaic Greece or the Middle Ages in modern myth, so poets and artists elsewhere rediscovered, or freshly invented, mythical heroes and events for political use. Marked and conditioned by its origins – the revolt of German intellectuals against French culture and domination with some help from Ossian – cultural nationalism crystallized the desperate ambitions, drives, fantasies and confusions of generations of educated young men everywhere, even as the Crystal Palace expanded around the world, making it more and more homogeneous.

I laughed out loud at the shaggy dog & man video, too!