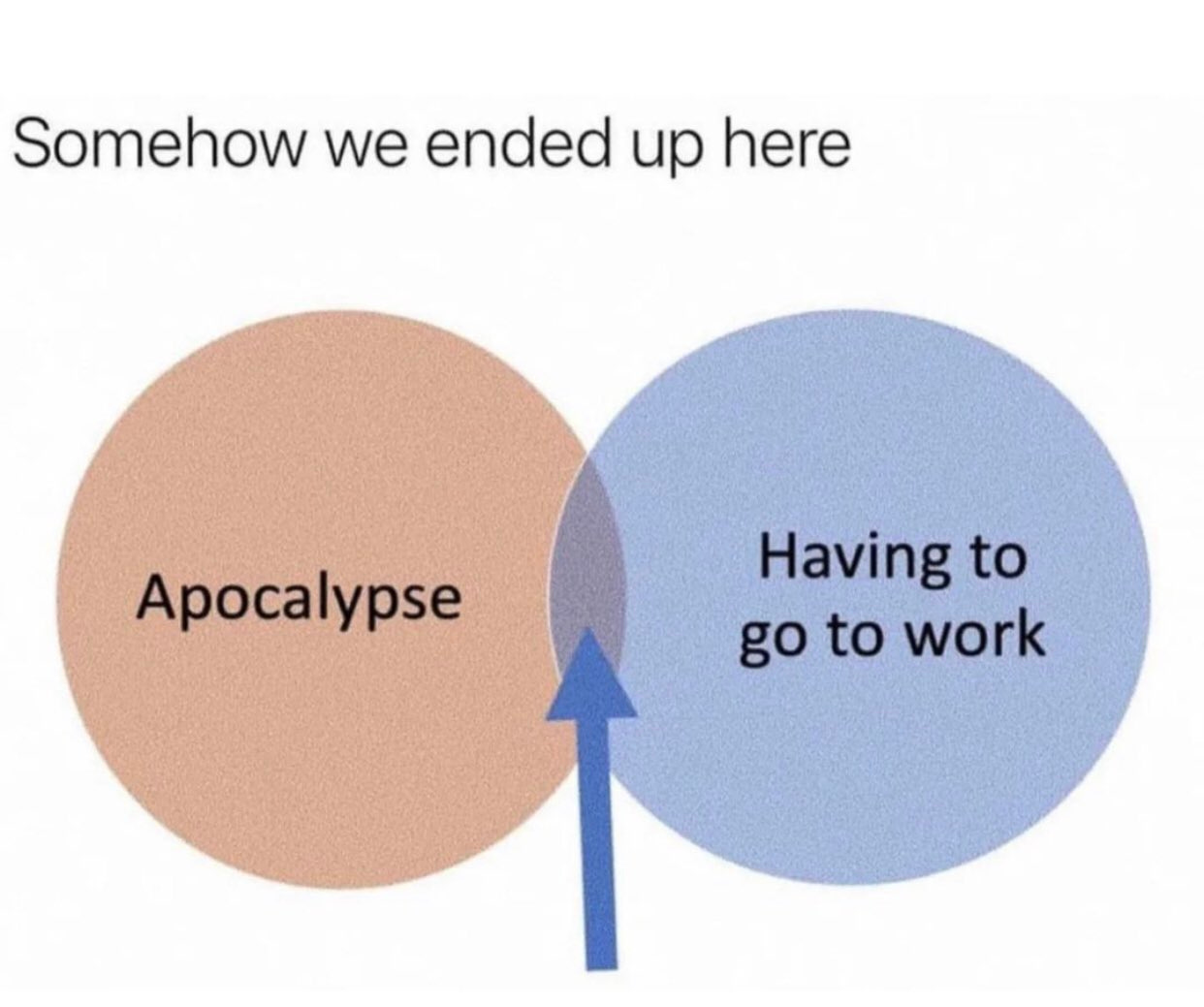

The AI apocalypse: Enjoy it while it lasts

And lots of other things in another bumper edition. (Can you believe I don't charge for this?)

AI-assisted production and AI-assisted consumption do not cancel out: Post of the week

I loved reading Venkatesh Rao’s post on AI this week and it gives me an excuse to replicate something I e-mailed a friend a few weeks before - with some touching up. (It’s a little cerebral, but there you go, I find the subject interesting).

One thing AI is illustrating is the wisdom of 'perspectivism'. We (at least we moderns) think of our minds as mirrors of nature. We have models in our head and they're good models to the extent that they're accurate reflections of what's 'out there'. If they’re accurate that helps us survive in the world. But that understates things. They evolved with that one goal. And as Nietzsche put at the centre of his philosophy, the evolutionary advantages they gave their bearers was the power of deception. That and an awful dose of vanity all supplied to you in 3D surround sound (See quote linked to at the bottom).

Moderns have got all this backward. They elevate science episteme (knowledge of the necessary structure of things) to the pinnacle of human intellectual achievement. In fact however our mastery of episteme is rather, a very specific aspect of the core role of intellect which is practical capability to act in the world to our advantage or phronesis (this is usually translated as 'practical wisdom' — which is OK with me.)

Modern science started bumping into the untenability of episteme as a paradigm of all knowledge in the late 19 and early 20th centuries when the failure of the luminiferous ether mocked its hankering for some universal frame of reference in which to ground knowledge of the world. Relativity and quantum mechanics finished the job. Even in nature, statements about what is the case don't make any sense outside of some frame of reference in time and space and that makes the knowledge partial - bounded by the particular frame of reference.

What's the connection with AI? When I search Google to find out who won the Australian Open in 1975, I must think my way into a set of referents that will produce some curated knowledge that will contain the answer to my question. "Winners of the Australian open".

AI is offering services that are already more agentic (horrible word). I ask "Who won the Australian open in 1975" (It was John Newcomb by the way. I was there! The most sublime sporting event ever to burn itself into my psyche). It then takes my point of view into the internet and gets me an answer. A great asset of AI is to help us see what Nietzsche was pointing out in the late 19th century.

Next time someone uses the adjective "epistemic" ask yourself whether what they mean is better represented by the non-word "phronesic'. And that we don’t even have such a word tells you all you need to know!

Anyway, there’ll be more on me on this score soon. Meanwhile, here’s Venkatesh Rao:

In the last couple of weeks, I’ve gotten into a groove with AI-assisted writing … and I am really enjoying it. You’ve seen the results — a 3x increase in posting frequency. … I don’t know if I can keep that up, but we’ll see.

Now I am become Jevons Paradox, Destroyer of Inboxes.

For those of you struggling to keep up, a sincere suggestion — start using AIs to help you read. And no, AI-assisted production and AI-assisted consumption do not cancel out.

My AI expanding my one-liner prompt into a 1000-word essay that is summarized to a one-liner tldr by your AI is a value-adding process because your consumption context is different from my production content.

High compression/expansion ratios in such writer-reader relationships do not mean there is low information content. A 1:100:1 expansion/compression pipeline does not mean there are only ten words worth of information in a 1000-word transmission. The other 990 words go towards mind-melding our contexts. I suspect there’s a way to model this using mutual information and alignment of priors, but I’ll leave that to the more mathematically inclined among you (assisted by your AIs). You can also have a two-stage expansion pipeline instead of an expansion-compression pipeline. People often complain I am being too cryptic or gnomic. Well, now you have the tools to get things explained to you. So with some of you, some of my posts might go through a double expansion process — say 1:100:200.

The AI element in my writing has gotten serious, and I think is here to stay. While I still plan to segregate my unassisted and AI-assisted writings into the two sections of this newsletter for the time being, it feels like a temporary adjustment phase.

So it feels like it’s time to reset expectations for this newsletter a bit. I’m an AI+human centaur now, and should say something about Terms of Centaur Service.

To qualify the above a bit, getting a brilliant 2000-word essay out of a single prompt is of course as rare as a traditional first-draft being publishable with no edits. Usually I do have to do some iterative work with the LLM to get it there, and that’s the part that’s creative fun. In general, an AI-assisted essay requires about the same amount of high-level thinking effort for me as an unassisted essay, but gets done about 3x-5x faster, since the writing part can be mostly automated. It generally takes me an hour or two to produce an assisted essay. An unassisted one of similar length is usually 7-10 hours.

But I’m not really interested in production efficiency. That’s a side effect that has the (possibly unfortunate for some of you information-overload-anxious types) effect of increasing production volume. I’m interested primarily in enjoying the writing process more, and in different ways.

I’ve been doing unassisted writing for a couple of decades now, and this new process feels like a jolt of creative freshness in my writing life. It’s made writing playful and fun again.

I’ve also really enjoyed having AI assisted comprehension in tackling difficult books, such as last month’s book-club pick, Frances Yates’ Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. I don’t know that I’d have been able to tackle it unassisted.

On the writing side, when I have a productive prompting session, not only does the output feel information dense for the audience, it feels information dense for me.

An example of this kind of essay is one I posted last week, on a memory-access-boundary understanding of what intelligence is. This was an essay I generated that I got value out of reading. And it didn’t feel like a simple case of “thinking through writing.” There’s stuff in here contributed by ChatGPT that I didn’t know or realize even subconsciously, even though I’ve been consulting for 13 years in the semiconductor industry.

Steve Jobs puts the same point in his inimitable way

Breaking the bank for Kate

Well, I told you I’d match payments up to $5,000 so you went ahead and tried to bankrupt me! With $5,125 in donations, I’ll match that, and to avoid anyone accusing me of the very scunginess I warned you all against last week, and to go the extra mile in avoiding any accusations of appalling errors of judgement, I’ll throw in the additional $125. So that’s $10,250 to Kate to match against Gina’s gazillions (and the baby-seals Gina plans to behead should her candidate win).

Thanks to all 23 donors and also to the 21 who permitted me to share their first names here. Jon, Frank, Gottfried, Tony, Victoria, Tim, Stephen, Philip, Beth, Moz, Andrew, Geoff, Belinda, Caroline, Wayne, Frank, Julie, Simon, Henry, Susan.

Remembering the Dunera

If you’re in Sydney you really should go to the free exhibition upstairs in the glorious Mitchell Library. It’s on the Dunera - the famous boat on which 2,000 odd Jewish reffos came from the UK to Australia in 1940. I went because my father was on the boat. That’s why I was on the panel that discussed the Dunera when the exhibition was launched. (Apologies for the various silences and crack-ups. That creeps up on me surprisingly often in such situations where I’m discussing my Dad.)

But why should you go? Well it’s an interesting story, but you really should go because it’s amazing what these guys were capable of. Along with the stories, there are some marvellous pieces of art. I could even recognise my godfather Klaus Loewald in one of the portraits.

The exhibition’s been open for many months, and the function I participated in was associated with the opening of the exhibition last year. But it closes at the end of this month. Perhaps you can make the closing event, which looks intriguing!

Setting high expectations

Is Islam a religion of peace? Lessons from Uzbekistan

I met and became friends with Konstantin Kisin through Kilkenomics. He’s since swung to my right on the ideological spectrum, but there you go. Thing is, one major aspect of political combat is that there are things it’s not polite to talk about - and those things are important. For a while now, I think that problem has been much worse on the left. And Konstantin targets the left’s silences and, when he does it well, as he does here, he does us all a service. Click through to his post and subscribe if you want to read his full analysis of how the most successful countries manage to successfully deal with Islamic extremism.

Western Europe has been engaged in a raging debate about mass immigration for at least a decade. If upon reading this statement you accepted it without objection, you have, like most people, swallowed what is at best a polite fiction and at worst a deliberate misframing of the problem. The claim that the debate is about "mass immigration" is fraudulent on at least two levels.

First, while we argue about stopping illegal immigration and keeping legal immigration manageable, the reality is that the concerns most people have are not about the future, or even the present. They are about the past. Dig even slightly under the surface of anti-immigration sentiment and you will discover that the core concern for many is not what might happen, but what has already happened. In other words: the debate is not about mass immigration but about the impact of the immigration that occurred not only in recent years but sometimes in decades past.

Second, the great unsayable in polite society is that not all immigrants are the same. Britain, for example, experienced a wave of Polish and Romanian immigration in the 2000s. Since 2022, millions of Ukrainians fleeing Putin's invasion have been given refuge across the continent. Hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers have escaped the Chinese Communist Party's crackdown by coming here too.

Scour as you might, you will struggle to find any anti-Polish sentiment beyond the very fringes of our societies. There is no need for a debate about preventing societal discrimination against Ukrainians because no such discrimination exists. Hong Kongers appear to be doing just fine.

The rise of anti-immigration parties across Europe is not a response to mass immigration per se. It's a response to the importation of large numbers of people from what even the bravest of our politicians euphemistically call "incompatible cultures". To them, the problem is not immigration, it is Islam.

There are three broad schools of thought on this issue.

The progressive response is the head-in-the-sand mantra of "diversity is our greatest strength". This slogan, mindlessly repeated, is a proxy for a whole host of dishonesties. ...

This package of lies, combined with the reality of the problem itself, has given rise to the second–and, in some ways, equal and opposite—school of thought. According to this perspective the problem is not Islamism, it is Islam itself.

Naturally, this group is diverse and not easily quantified. Some are ex-Muslims or those who have dealt with the reality of Islamist extremism and violence, like Gad Saad who says "There is no radical Islam, there is simply Islam". This is, incidentally, also the view of Islamists themselves: they claim that there is only one way to be a Muslim, which is to seek to impose Islamic values on the whole world, introduce sharia, and subjugate non-believers and those of other faiths. ...

The problem I have always had with this argument, though, is that there are many countries around the world which are majority-Muslim—and some with large Muslim minorities, like Singapore—which appear to have dealt with Islamist extremism far better than we have in Western Europe. I saw this myself in Uzbekistan, where I lived between 1986 and 1990, and again when I returned here last week.

This is why, while remaining open-minded to different perspectives and claiming no expertise, I lean towards the third camp: people who believe that religious extremism is a problem which has a tried and tested solution.

My latest trip to Uzbekistan is a case in point. Islam is everywhere. The most prominent contemporary and historical buildings here are mosques and madrassas. It is not uncommon to be awakened in your hotel at 5AM by the Islamic call to prayer. Many men wear skullcaps called tubeteikas, while women dress modestly; some sport headscarves and traditional outfits which cover the full length of their arms and legs. ...

But not-Islam is everywhere too. Alcohol is sold in shops and many restaurants, not just for foreigners but for anyone who wants to buy it. Many (and I would say most) girls and women wear jeans, trousers, knee-length skirts, and other secular clothing, especially in the cities. "I saw a woman in one of those black bags," one woman tells us in a disapproving tone. "You could see her face but that was it - this is not our way!" ...

The few churches and synagogues you'll find in Uzbekistan are protected and well-maintained. Most Christians and Jews have left for America, Europe or Israel but not because of persecution or oppression. When the USSR collapsed, opportunities for the well-educated dried up and they left in search of a better life as many did from non-Muslim Soviet countries. "I am an Armenian," our driver tells us. "I've lived here since 1994 - we have no ethnic issues here. At Easter my Muslim friends come to my house to celebrate with me. For their holidays, I go 'round to theirs". ...

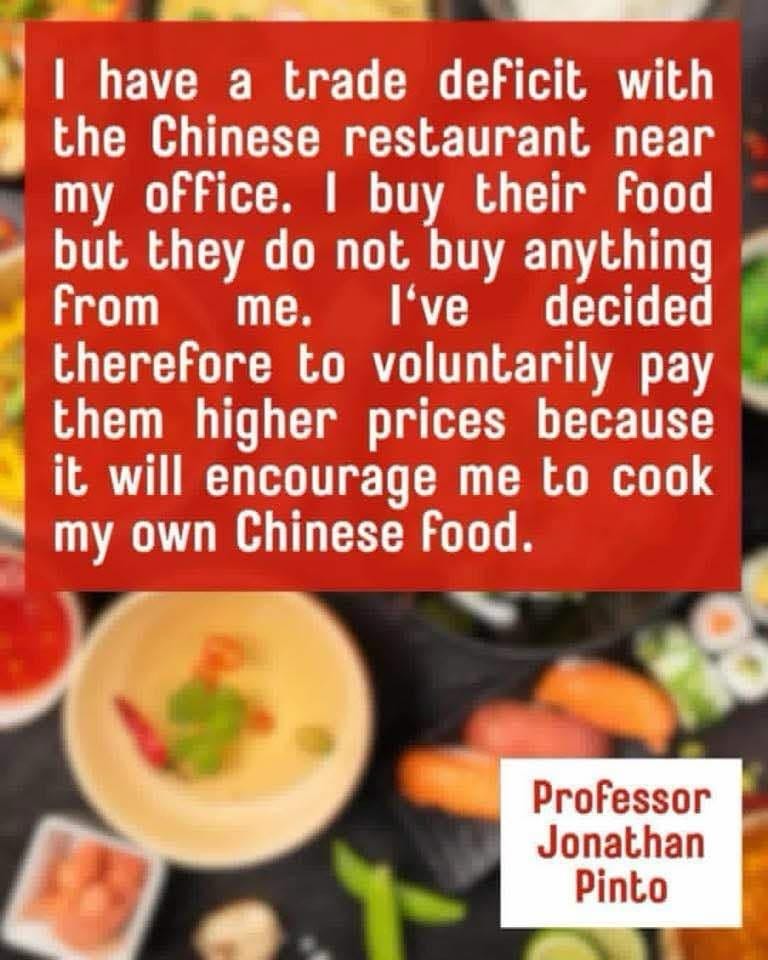

Brad DeLong reports on Larry Summers’ demolition of Oren Cass

Another reason Oren Cass is wrong

Joe Klein on the tariffs

The video is for anyone wondering why Joe Klein calls his substack “Sanity Clause”.

Sanity Goddess and I have been on the highway for the past few days, leaving the winter Sanity Shack and traversing the East Coast on I-95. Normally, we listen to music…and we did some of that. But we also spent a lot of time listening to CNN on Sirius. That meant inflicting Donald J. Trump on SG for almost an hour—59 minutes more than her synapses would normally tolerate. But this was important! It was Liberation Day (and SG amused herself by noting whenever Trump jumped off the teleprompter and started riffing—it was always about him). Meanwhile, I counted cars.

There were very few "American" cars on that asphalt desert. I put that in quotes because it's hard to know how many Toyotas and Hyundais and KIAs and Hondas whizzing along were Made in America. Actually, none of them were, entirely—nor were the occasional Chevys and Dodge Chargers. Most of them were made, in part, here and, in part, there...

This raises a question. Whatever happened to the American auto industry? There is the basic fact that American cars begin to suck around 60 years ago—there were domestic flurries, like Lee Iacocca's K-Cars and assorted minivans…And there are still more than a few Caddies about. But it's been apparent for a half-century that American sedans were precarious tin cans that fall apart very quickly, so you can be lured into buying another. They are paragons of planned obsolescence...

There are liberal and conservative explanations about why this implosion happened. Both sides are right. Conservatives are correct that union labor pushed its luck too far in negotiations. That's why Datsuns and Toyotas—and Hyundais (back to them in a moment)—were so cheap...

The basic conservative argument was: it was labor what killed Detroit. More sophisticated moderate Dems argued more obscurely, but very much accurately that Detroit died when the accountants replaced the engineers running the companies. Car guys like Iacocca and John DeLorean and maybe even Edsel Ford (Do you remember what the Edsel looked like? Wild.) were replaced by green eyeshade guys. With labor so costly, every corner possible had to be cut. American car doors rattled emptily when they shut; on my Toyota, the door thunked...

After I made a cross-country road trip about 15 years ago, President Obama asked me what I'd learned. I told him that people really wanted to know what he thought about China. Why didn't he give a speech about trade? The speech was never made. But the issue festered.

And so, as with so many Trump initiatives—the border, racial preferences—there was a public desire for a change in trade policy. The offshoring had become dangerous—as Joe Biden recognized when he signed the Chips Act, to bring the manufacture of those crucial silicon slivers back to America. Steel and other necessary components had been off-shored as well...

A correction was needed. A scalpel not a chainsaw. Tariffs on chips and steel, yes. But also a recognition that American cars, for example, were an intertwined coproduction of the US, Mexico and Canada. Parts went back and forth across the borders. Assembly happened in all three countries. All three countries prospered, even if union auto workers suffered...

So Trump, and chaos. So recession, most likely, long and deep perhaps. And an ulterior motive, too: to raise money to pay for the Trump tax cuts. Indeed, in the case of Vietnam Trump is setting 46% tariffs not because Vietnam has equivalent tariffs on American products—but because we have a trade deficit with Vietnam. We buy a lot of sneakers and clothes from there...

Will this be a disaster for Trump? It should be. You can't mess with people's lives like this. You can't assume the foolishly myopic support from the business community will stick with the Trump Administration. But I've predicted disaster for Donald multiple times in the past…and it never quite arrives. After the Great Biden Meander, the public seems hungry for a leader who seems decisive and confident and strong. Strength is assumed to create order. But what happens when strength creates disorder and economic disaster? We are about to find out.

Senseless cruelty towards the courageous anyone?

From Roger Berkowitz of the Hannah Arendt center for politics and the humanities.

The United States is … a complicated country. It is the country of chattel slavery and genocide against Native Americans. It is, as Hannah Arendt argued, a wild and violent country with a frontier mentality that celebrates vigilante justice. At the same time, there is a traditional American respect for individuals as worthy of self-government, and a history of collective action and civic engagement. There is also superficial friendliness characteristic of Americans' relations to strangers that nevertheless contributes to a sense of neighborliness essential to a country of immigrants. And there is the idea of the country as a "city on the hill," a bastion of freedom and a refuge for immigrants, the huddled masses, yearning to be free.

Again and again, we are seeing our law-abiding neighbors threatened, arrested, and deported for no good reason. This arbitrary cruelty by customs officials is celebrated by the President and his administration. Beyond normalizing angry boorishness, it spreads fear and intimidation throughout communities across the country.

Some of those targeted for having their visas revoked engaged in constitutionally protected First Amendment rights of protest. This cynical attack on those legally here who possess the rights of freedom is wrong. But increasingly, we are seeing numerous accounts of neighbors who came to the United States legally and are being arrested and deported for fully arbitrary reasons. Consider the truly disturbing case of Kseniia Petrova. As Ellen Barry writes,

For nearly eight weeks, Kseniia Petrova has been captive to the hard-line immigration policies of the Trump administration. A graduate of a renowned Russian physics and technology institute, Ms. Petrova was recruited to work at a laboratory at Harvard Medical School. She was part of a team investigating how cells can rejuvenate themselves, with the goal of fending off the damage of aging.

On Feb. 16, customs officials detained her at Logan International Airport in Boston for failing to declare samples of frog embryos she had carried from France at the request of her boss at Harvard.

Such an infraction is normally considered minor, punishable with a fine of up to $500. Instead, the customs official canceled Ms. Petrova's visa on the spot and began deportation proceedings...

Petrova fled Russia after she was arrested for protesting Russia's war on Ukraine. She was recruited by Harvard where she refused on principle to agree to a condition requiring her to stop criticizing Russia in exchange for security clearance. Her qualifications were so exceptional that Harvard proceeded to hire her as a contractor. A "supernerd," Petrova worked long hours and was an invaluable and well-liked member of her community...

As [Petrova] headed toward the baggage claim, a Border Patrol officer approached her and asked to search her suitcase. All she could think was that the embryo samples inside would be ruined; RNA degrades easily. She explained that she didn't know the rules. The officer was polite, she recalled, and told her she would be allowed to leave.

Then a different officer came into the room, and the tone of the conversation changed, Ms. Petrova said...

So why is this happening? What is the reason for treating principled, law-abiding, hard-working neighbors who want to contribute to American science and technology like unwanted criminals? These are not people here illegally. These are not people on welfare. These are not criminals. Victims like Petrova are not even people who have exercised their constitutional rights—guaranteed to all persons legally in the United States—to exercise their First Amendment rights. She was targeted simply for a mistake at customs control.

Like Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, a Maryland man who was mistakenly arrested and deported to El Salvador because of what the government now calls an administrative error, Petrova was simply someone who came to the United States legally and was a good neighbor. What kind of angry boorishness leads to treating our neighbors in this way?

There is a profound anger animating the mistreatment of innocent neighbors in ways that are simply mean. Where does the anger come from? The traditional answer of the left is racism. I don't doubt racism plays a role in some of these deportations. But that simply doesn't apply in cases like Petrova's. Many of the people being rounded up and stripped of their legal visas are white Europeans. No, instead, the anger appears to be fueled by a long-simmering class resentment. There is a contempt for globalized elites, people like Petrova who have excellent educations and are at home in elite institutions around the world...

Perhaps nothing so clearly manifests the corruption of academia as well as the silence of Harvard and so many of its brilliant professors about Petrova's abduction and detention. The school, possessed of a $53 billion endowment, has not publicly defended Petrova. Many of her colleagues, worried about their own privileged positions, are silent. Courage and principle are in short supply. If the elites at our elite institutions are unwilling to fight for the principles on which the country is based, it is hard to shed many tears for them as they are cruelly and mercilessly attacked by a petulant President and his band of resentful sycophants who are tearing apart the fabric of our society.

Mr Harrison goes to Tassie

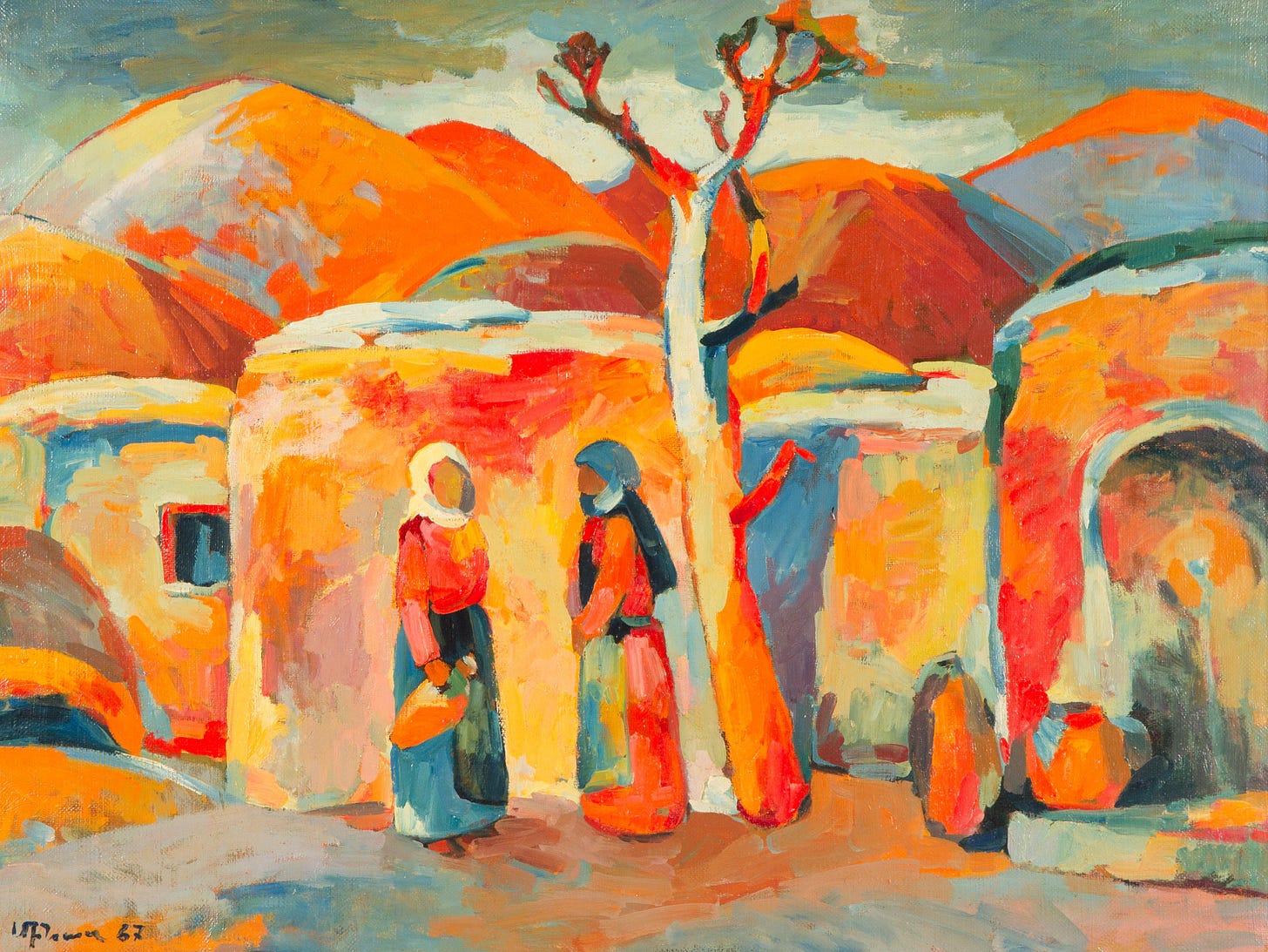

I ran into the top picture somewhere. And there were all the others! Lovely.

Dean Ashendon on truth-telling

I usually read Dean Ashendon in Inside Story and am rarely disappointed. This rehearses some ideas he’s been on about for a while, including in his 2022 Australian Political Book of the Year Telling Tennant’s Story. Recommended - buy it here.

Truth-telling has been losing ground ever since 10 December 1992, the day Keating PM told his truths to a predominantly Aboriginal audience at Redfern oval. "We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life," he said. "We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised the discrimination and the exclusion."

In the years that followed the trajectory of truth-telling had its ups and downs, but by the time we got through nine years of John Howard to the next Labor prime minister all we felt we had to apologise for was taking the children. The Voice vote marked another new nadir. There may be more to come.

For fifteen or twenty years — from, say Bill Stanner's Boyer lectures in 1968 — truth-telling had worked. Unearthing and telling the story battered Stanner's "great Australian silence" almost into submission. But from then? Telling schmelling. As Kate Grenville points out in the most recent of her four books on relations between Black and White, the story is told and the facts are known "beyond dispute," so the question arising is: "What do we do, now that we know?" (italics in the original).

It is a very good question, but it has to compete with old habits. Grenville's intentions notwithstanding, Unsettled tells the story, once again, and offers only a brief and unconvincing answer to the living-with-knowing problem. Grenville's difficulties are not hers alone.

Unsettled is a road movie. Setting out from her home town of Sydney Grenville tracks five generations of her family who have made lives and livelihoods on "stolen land," the first of them headed by Solomon Wiseman, made infamous by his great-great-great-granddaughter's celebrated novel Secret River, the fifth and furthest out, on the country around Tamworth, worked by her grandfather...

Most affecting for Grenville and for the reader are moments that bring her close to vertigo: yes, it really is true, those forebears were living on stolen land and so are we. We are living on land that has been home to more than a billion lives, lives lived in an elaborate civilisation that touched every nook and cranny of a vast continent.

But where does this journey, this quest, this pilgrimage get us, and Grenville?... The answer comes almost as an epiphany: it ends at Myall Creek, not far away from her grandfather's holding, a place where terrible things happened and where, 160 years later, those things have been remembered as they should be:

In memory of the Wirrayaraay people who Were murdered on the slopes of this ridge In an unprovoked but premeditated act in The late afternoon of 10 June 1838.

Erected in June 2000 by a group of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians In an act of reconciliation, and in Acknowledgement of the truth of our Shared history.

We remember them. Ngyani winangay ganunga

Here, in this place, says Grenville, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians came together to acknowledge and record the truth. If they can do it, "the rest of us can do it too."

Well, yes, but also no. Yes, public history of the Myall Creek kind matters; it has power. It is the history curriculum of everyday life. But no because the Myall Creek monument is the exception that proves the rule, which is this: sixty years of truth-telling has left scarcely a mark on public history.

Australia has around 41,000 monuments, plaques, obelisks and other markers of the past. The biggest single group: the war memorials, more than 12,000 of them, memorials to the "fallen" of the first and second world wars. Then come the "explorers" and "pioneers," followed by civic worthies and local events or places of purely local significance. Only a couple of hundred have to do with Indigenous people or relations with them, and only a small fraction of those tell the truth of the long and violent conflict between Black and White...

There is no doubt that telling and learning the truth is for some, including Kate Grenville, a moral imperative. But truth-telling also has a more transactional side to it — after all, what does it cost, apart perhaps from manageable doses of dismay and sadness? And on the other hand, what an agreeable view from the high moral ground!

To others — broadly speaking, those who voted No in the Voice referendum — to tell or not to tell is a more complicated matter... Different education levels come with different life-worlds, including different experiences of the powerfully formative institutions of education, where you live, the kind of job you get, the terms of employment and, for some, relationship with a different category of Aboriginal people. From life in the regions or the outer suburbs, blue-collar jobs, less secure employment, lower lifetime earnings and different relations with the education system come mixed feelings about "them," often as strongly held as they are rarely "articulated."...

There will probably be no movement unless and until all those graduates in a Labor government in Canberra realise that truth-telling demands a re-think as to ways and means. Public history, including public history of the Myall Creek kind, will have an important part to play. In this Labor made a less than inspiring start when it appointed Kim Beazley to get the Australian War Memorial to finally recognise that the 120-year armed conflict between peoples was in fact war (and, we should add, by far Australia’s most costly and formative war). Down in the grassroots much could be achieved by a properly funded and focused body to encourage thousands of local communities to work with Indigenous people and local and professional historians to audit the telling by local public history of the local story, and then to work though those mixed feelings by deciding whether and how the story could be more fully told.

In the meantime, there is one substantial part of the story that could use some more telling: the story of the telling of the story — the story, that is, of the long struggle between White and White and then Black and White over whether or not the story should be told.

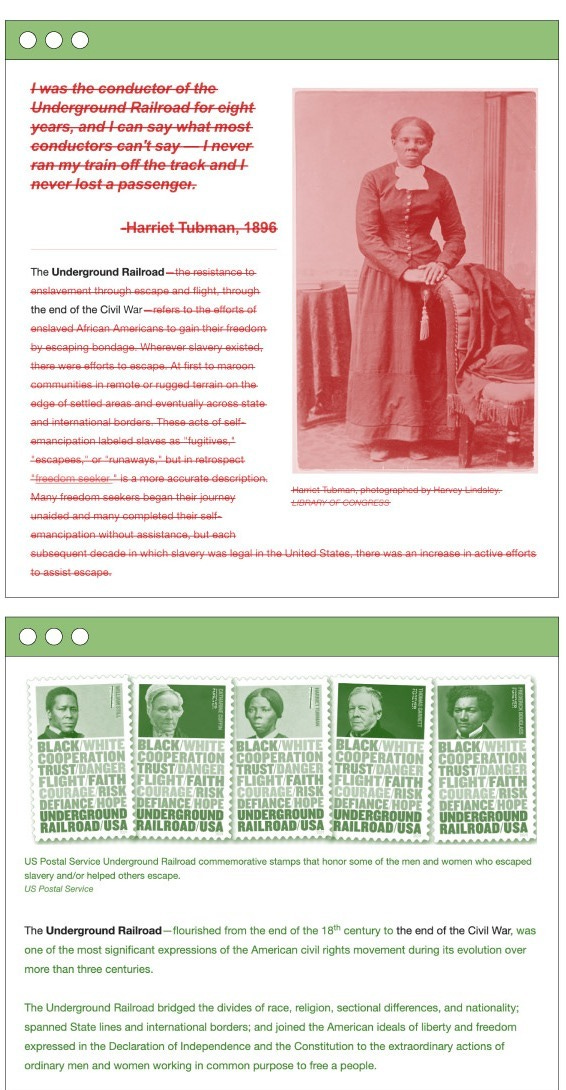

National Park Service rewrites history of Underground Railroad

Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.

For years, a National Park Service webpage introduced the Underground Railroad with a large photograph of its most famous "conductor," Harriet Tubman. "The Underground Railroad — the resistance to enslavement through escape and flight, through the end of the Civil War — refers to the efforts of enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom by escaping bondage," the page began.

Tubman's photograph is now gone. In its place are images of Postal Service stamps that highlight "Black/White cooperation" in the secret network and that feature Tubman among abolitionists of both races.

The introductory sentence is gone, too. It has been replaced by a line that makes no mention of slavery and that describes the Underground Railroad as "one of the most significant expressions of the American civil rights movement." The effort "bridged the divides of race," the page now says...

The executive order that President Donald Trump issued late last month directing the Smithsonian Institution to eliminate "divisive narratives" stirred fears that the president aimed to whitewash the stories the nation tells about itself. But a Washington Post review of websites operated by the National Park Service — among the key agencies charged with the preservation of American history — found that edits on dozens of pages since Trump's inauguration have already softened descriptions of some of the most shameful moments of the nation's past...

Changes in images, descriptions and even individual words have subtly reshaped the meaning of notable moments and key figures dating to the nation's founding — abolitionist John Brown's doomed raid, the battle at Appomattox and school integration by the Little Rock Nine...

An educational page on Benjamin Franklin, which examined his views on slavery and his ownership of enslaved people, was taken offline last month, the review found. Mentions of Thomas Stone, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, owning enslaved people were removed from several pages on the website of the Stone National Historic site in Southern Maryland...

Trump has pursued broad executive orders and other measures aimed at dismantling "diversity, equity and inclusion" programs across the public and private sectors...

One of the surviving members of the Little Rock Nine, Elizabeth Eckford, told The Post that the edits masked the fact that the group had explicitly fought for equality of opportunity.

"They're trying to rewrite history," Eckford said. "We can never have true racial reconciliation until we honestly acknowledge our painful but shared past."

The best of British self-deprecation

To say nothing of this scene

The Making of "Eleanor Rigby"

Looks like Ian Leslie has written a book of considerable terrificness which pays homage to Paul McCartney’s genius. I’d heard this story, but it’s spooky all over again. I’ve summarised what’s a much longer piece and then left you on a cliffhanger. So you might want to go directly to the original.

In the early months of 1966, whenever Paul McCartney sat down at a piano, wherever it was, he would start tinkering with a song he called "Miss Daisy Hawkins." From the moment he found its first five syllabic notes, the song seems to have found its themes: loneliness, futility, the end of life. McCartney was twenty-three. Without discussing it, both John Lennon and Paul came back from their break with songs about death, written from a detached, omniscient perspective.

In "Tomorrow Never Knows" John dispenses instruction from the mountaintop. In two minutes, "Eleanor Rigby" captures the entire lives of two individuals in a series of stark images. Musically, both songs are stripped down to a few parts in order to distill and intensify some essence. "Eleanor Rigby" confines itself to a narrow melodic range and the song has minimal harmonic development: like "Tomorrow Never Knows," it alternates between just two chords.

Set in a minor key, its tightly wound, almost claustrophobic verse plays out over an accompaniment—a string section arranged by George Martin—that sticks close to the tonic, except when the cellos burst into a galloping run up the scale. This section is joined to a refrain in which the singer asks where all the lonely people come from while the cellos play a Bach-style descending line...

It's hard to explain "Eleanor Rigby." Nobody had created a pop song like this before. Its cultural ubiquity has stopped us from noticing how strange it is—at least as radical, in its way, as "Tomorrow Never Knows," which John came up with after hearing Paul play "Eleanor Rigby." Both John and Paul were living up to Arthur Schopenhauer's definition of genius: unlike talent, which hits a target nobody else can reach, genius hits a target nobody else can see.

Since Lennon became known as "the literary Beatle" McCartney's talents as a lyricist have been overlooked. His feel for words is essentially musical and sensual rather than semantic...

In "Eleanor Rigby" McCartney uses the sounds of words as connecting fibers; Everett points to how "Paul grabs a sound and hangs on to it." In the same place in each verse, we get "rice" paired with "face," "church" with "dirt"—not rhymes so much as matching colors. There is a discipline to McCartney's structure. Each line of the verse opens with a five-syllable phrase in which the fourth syllable is stressed ("Eleanor Rigby / Waits at the window / Father McKenzie / Look at him working"). These opening phrases are mirrored by the closing phrases of each line in "Tomorrow Never Knows"—you can sing "it is not dying" or "it is believing" in their place...

In "Tomorrow Never Knows," however distant Lennon's voice sounds, the message is ultimately a soothing one. "Eleanor Rigby" offers no comfort. It turns an unflinching, even acerbic gaze on its characters. A woman picks up rice in a church, tidying up after a wedding. Oblivious to joy, she lives in a dream and wears a face that nobody sees. In the second verse, we meet Father McKenzie, writing his sermon for nobody. In the third and final verse, they are brought together without coming together. He buries her in a perfunctory ritual. Everything is concise, economical, and devastating: no one was saved.

"Eleanor Rigby" was another of McCartney's slow hunches: it took him at least three months to write. A dinner party hosted by Cynthia and John at Kenwood proved to be a staging post on the way to its completion. After dinner, McCartney played his song on guitar to a few Beatles intimates, including John's friend Pete Shotton, and invited suggestions for how to finish it. He had the first two verses with their two characters, Eleanor Rigby and Father McKenzie (then "Father McCartney"), but hadn't yet worked out a third verse...

As soon as the world heard "Eleanor Rigby," it was hailed as a masterpiece, specifically for the poetic quality of its lyrics. But John was meant to be the "literary Beatle."

For years, McCartney gave a pretty detailed account of how "Eleanor Rigby" got its name. He landed on "Eleanor" first, borrowing it from the actress Eleanor Bron, who played the female lead in Help! Next, he cast around for a surname with two syllables. In February 1966 he drove down to Bristol to see Jane Asher perform in a play, and while there he noticed a sign on a wine merchant's storefront that read, "Rigby & Evens Ltd." So that was how it happened.

Except, in the early 1980s, somebody pointed out that ...

Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky

Thanks to reader Robert for drawing my attention to the guy who took these pictures by Russian Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky born in 1863.

The end of the long 20th century

Hegel is back! Karl Stefanovic has been predicting this on his morning show rants. Nice to see the German Health Minister gently elide that bit about the end of history - that didn’t work out so well.

Heaviosity half-hour

Elias Dakwar on placebo effects

I’m continuing to love Elias Dakwar’s The Captive Imagination. The placebo effect fascinates me - or rather how we’ve ‘cancelled’ the placebo effect. As I wrote here:

… As medicine was made more scientific, the placebo effect was discovered, and then marginalised. Yet it was of unarguable therapeutic power. Of course it’s entirely appropriate that, if one is looking for drug therapies, one wants to find drugs that, other things being equal, do better than sugar pills.

But in the process, the trail goes cold on keeping the placebo effect in the frame, not only for what it might help us understand, but, more remarkably, even for its therapeutic potential. There’s been vanishingly little investigation of the joint effect of the drug and the placebo acting together.

Shouldn’t we be trying to harness that? I’m pleased to say that I’m a minor investor in a company that’s trying, in a modest way, to do just that.

I quote the first few pages of Chapter 5 for context and then the last few sections on the placebo effect.

Chapter 5: The Return to Silence

Addiction is so impossible as to be alchemical. An ancient dream of miraculous transformation, like converting lead into gold or intoning prayers to stone until it attains a precious luster. Desperate to wrest a rarer, more sublime condition from the muck and density beneath us: we refuse to accept that this is all there is and yearn for luminous transubstantiation. The addict takes it even further. The material he works with is himself, his own existence, and he combusts his body and mind in the crucible, burning everything away until only the dream remains. It radiates a flash of gold, smolders for a moment, and then disappears into total darkness.

A moment’s intoxication will never be an enduring reality, no matter how ideal the prospect. But this is an impossibility that cannot, for good reason, admit defeat. There is a deeper dream that will always be with us. It haunts the darkness and continues to beckon to us no matter how many times it fails. The dream may not even be ours. The earth is “charged with the grandeur of God,” wrote the Christian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins.1 A sublime dream of paradise gleams through the cracks and fissures. The least Christian of ecstasies might serve as a doorway to it.

We seem to suffer without meaning, without end, any reprieve we find fleeting and precarious. The only certainty seems to be more suffering. Our expectations are bound to be frustrated, our vulnerability violated, our dreams denied and forgotten. But we continue to yearn, with insatiable hope, for an absolute liberation from our suffering, an enduring fulfillment that transcends these agonies, failures, disappointments. This is the single desire that unites us: to enjoy in every moment, however upsetting it might seem, a profound and everlasting consolation, much as the addict aims to alchemize a reliable fulfillment whatever the circumstance.

This is the deepest yearning of them all. Homeland, creative success, fame, pleasure, self-fulfillment, romance, religion, career, political power, wealth, addiction, even suicide: the promise of the absolute wears many masks. The masquerade, in fact, is endless. There will always be new dreams vying to convince us that we have found our dawn. When the flimsiness of the fiction reveals itself, we continue our search, liberated by our homelessness, for a moment, to recognize another direction.

Just ahead might be a reality that feels more like home, better corresponding to our ideas, dreams, and hopes. Our eagerness for it permeates everything. It also invites the confusion we’ve seen before, and to which everyone, addict and scientist alike, is vulnerable. Our fantasies not only become indistinguishable from existence; they come to possess more reality than it, with even direct evidence subordinated to our designs. The dream, the fiction, the paradigm not simply true, but transcendently, absolutely true. This is the apotheosis to which most of our fictions tend, before they fall, like Icarus, to earth. We dream our way into heaven, only to realize we have wandered far from home, into the wilderness, perhaps into hell. …

Placebo is Latin for “I shall be pleasing” and originally designated Vespers during prayers for the Office of the Dead, whereby souls in purgatory might come to supplicate the Lord and be more pleasing to Him. It also came to designate the inactive control condition in RCTs: the “sugar pill” compared to which an active medication is tested. One group gets the active medication, and another the placebo, in a random fashion, with neither investigators nor participants aware of what is administered. This design is intended to identify what the medicine is doing “materially,” as opposed to what the person or investigator believes it might do by virtue of all the pleasing things that might heighten a therapeutic response, such as enthusiasm, positive expectations, the clinical setting, and a warm rapport between patient and treatment team.

The placebo response53 more generally refers to the benefits a treatment might exert that do not emerge from its biological effects, in both research and clinical settings. It is a very real phenomenon; in depression studies, for example, the strength of the placebo response is robust, with many participants receiving relief from the placebo equal to that obtained from antidepressants. It is also thought to account for a good proportion of the clinical benefits of even real medications, including psychiatric treatments. But it is also a very unreal phenomenon. It emerges from the representations that surround a substance, and that are conjured by the suggestive staging of its consumption: the set, setting, meaning making. The substance becomes more than it is, to good effect.

Even a non-substance, a sugar pill, might have real power based on these contextual, representational, and psychological forces. A sugar pill is administered in a clinical setting, and it alleviates depression, an infection, lower back pain. There might be a number of explanations for why an “unreal” treatment might address a “real” condition. The first is that the (un)reality of the placebo mobilizes resources of real well-being on the part of the person; the placebo tells a story of healing, so to speak, to which the person listens intently and with commitment, accelerating his healing in the process.

This appears to be the inverse of the fictionalization that occurs in addiction. Recall Ahmed and his compulsive pantomime of injecting heroin, even when its capacity to exert an effect was entirely abolished. Both representational modes turn to a substance to alleviate suffering, and in each case, the substance becomes other than it is: a sugar pill becomes medicine, cocaine becomes indispensable to a full life, heroin becomes a promise. But there is a clear difference between the two sets of representations. With the placebo response, the (non-)substance is represented in such a way as to marshal the person’s own capacity for healing and overcoming suffering: “This will help me heal from my distress, administered responsibly under medical guidance.” With addiction, the story surrounding a substance, mental state, or activity goes the opposite direction, cannibalizing and depleting the internal resources that allow for well-being and freedom: “I am incomplete on my own, and I need this to feel better, come what may.”

The mode of storytelling is also different. With a placebo, the meanings surrounding the substance are introduced and mediated by the clinical milieu. The patient receives the intervention from a treatment team; there is a ready-made script; the person can surrender to the story, knowing he is not in it alone and that there is relative safety and security due to the responsible involvement of health professionals.

Addiction involves a more perilous path, with very little to mediate the unreality that traps a person beyond his own desperate grasping (as well as that, perhaps, of the subculture with which he associates). The unreality is far more chaotic, more personal and binding, with the person making up the story as he goes along. If the placebo response is a well-practiced troupe performing Shakespeare, addiction is a maniac believing himself to be Hamlet, paralyzed by an urgency to do the bidding of ghosts.

This suggests another way that the placebo response might be helpful. The madman believing himself to be Hamlet suffers because of his (un)reality, as do Quixote, Ahmed, Fred, Marcus. The suffering, in these cases, stems quite clearly from (un)realities that have seduced the person. These are particularly obvious examples of how fictions can wreak havoc. But there might be an (un)real component to all suffering—a thicket of representations, let’s say—that might exacerbate, deepen, or even initiate unease, and which might be disrupted by the more creative and therapeutic (un)reality permeating a placebo.

A person may be “depressed,” for example, because his thoughts and emotions seem overwhelming, leading to sleep and appetite issues, work difficulties, apathy, and lack of pleasure in previously enjoyable things. He seeks support in medications that might render his thoughts and emotions less cumbersome; and he finds relief in a placebo administered during a RCT testing a drug intended to normalize his neurochemistry and restore balance to his mind. The placebo apparently revives his capacity to appraise his inner world more dispassionately and serenely. But perhaps this capacity for equanimity and detached attentiveness had never been lost. The antidepressant effect of placebo, in this case, might be a therapeutic type of disillusionment. He is disabused of the fiction that his thoughts and feelings weigh heavily on his consciousness; he regains his inherent freedom from them, a capacity to experience them more fully and with greater suppleness. This comes through yet another fiction: that the “medicine” has changed his neurotransmitters and cured him of his depression. The story he had been telling himself about his suffering is replaced by another, truer to what is possible for him. Healing here is a procession of lies, progressively approximating the truth. Such lies might be inevitable for moving forward from some diseases; maladies of fiction might be best met by fictional remedies: that is, by remedies harnessing the profound power of storytelling, invention, and imagination.

Consider the other falsifications that a placebo might disrupt: This infection is going to last forever, there is no way out of my pain, I need heroin to live. There are many cases of suffering that might lend themselves to this. Indeed, a recent report54 found that half of German doctors prescribe deliberate placebos of various sorts—sham surgeries, inert substances, vitamin pills—to address diverse medical problems, with consistent improvements.

The two mechanisms by which a placebo works—mobilizing self-healing and disrupting a certain (un)reality—often work together. This might be exemplified by the effects of psychedelics. It is possible that ketamine and similar substances exert their benefits, at least in part, by facilitating a uniquely powerful placebo response, tapping into the same mechanisms that account for the benefits that sugar pills confer. First, the staging occurs for a certain therapeutic story to be told: that freedom and enduring contentment are possible, for example. A perspective is cultivated that allows the person to leverage whatever might appear to his subjectivity toward this end. The medicine is then administered in a manner that transforms this possibility, for a blessed moment, into what seems actual and real. With that possibility rendered more palpable and within reach, the person feels galvanized to continue the work under guidance and with commitment. He allows himself to heal while he deprives his addiction of the deceptions that diseased him.

This is at least what happened to Marcus. The (un)reality at the heart of the addiction came to be silenced. The story that emerged, and which helped facilitate this disruption, was that of “everything” and its miraculous emergence from “nothing.” But there may be many possibilities or fictions that might have been helpful. The stage was set for whatever might come. The “mystical” experience lends itself to such polymorphous storytelling: it awakens the person to his fundamental freedom or allows for communion with the ever-present ( ); confronts him with the shadow that obscures everything or unveils the ecstatic mystery within each moment. The experience may take many directions, though there is a shared momentum that unites these separate dreams: an unveiling of the ineffable ground in which “reality” is a mere stratum. It is up to the therapist and the person to harness it. A truer fiction might take root, which mobilizes the person’s resources to overcome the “disease” while also defanging it, divesting it of the power to deceive.

Does this mean addiction is a made-up disease? That it might be cured by nothing more than a sugar pill? Calling attention to the (un)reality of addiction, and to the way that a placebo or hallucinogen might be helpful, is not meant to minimize it. The suffering is not made up, nor is the tenacity of its self-deceptions, despite how “made up” the lies might be. Possibility is important to impart, irrespective of what corner it comes from. When the sense of possibility has been lost, then even a placebo might be treasured as real medicine—especially if it brings a pleasing song that redeems the moment from purgatory, creating opportunity for things to be more than they seem.

* * *

A few words about the placebo effect in psychedelic research. There is growing recognition that placebo-controlled trials are ill suited for ascertaining the “efficacy” of these potent psychoactive substances, and that we need to reimagine our empirical approach to understanding them.

The main reason is that it is usually obvious who received the active compound versus a placebo, thereby breaking the blind and creating opportunity for all kinds of confounding errors. Importantly, these issues may directly affect outcomes, with a heightened placebo response in the clearly “active” group and disappointment, disillusionment, or clinical worsening (“nocebo” effects) in the control arm. Preserving the integrity of an RCT requires minimizing these shortcomings as much as possible—by strengthening the blind, reducing expectancy effects, and ambiguating the distinction between the active and control arms of the trial. A common solution is to give a psychoactive comparator, such as a compound known to be ineffective but nonetheless associated with changes in consciousness (for example, the sedative midazolam [Versed] in the trials testing ketamine), or a lower but still psychoactive dose of whatever is being tested.

But these solutions do not address deeper challenges. Modern RCT methodology has certain commitments, including a universalizing protocol-based orientation and a diagnosis-driven focus on impacting discrete outcomes in a linear manner. It is unclear whether these commitments are reconcilable with therapeutic work with these substances, which tend to have transdiagnostic effects, might exert benefit in nonlinear, subtle ways, and require sensitivity to differences between individuals, as well as to the unique relational field nurtured between provider and patient.

Conceptualizing the placebo response as a kind of pollutant that needs to be purged or mitigated is another major issue. After all, the same processes involved in the placebo response—staging, storytelling, therapeutic representation, the sense that something meaningful is happening—may be critical for harnessing the potential of these compounds. Undercutting these factors, and minimizing their impact, to test efficacy more cleanly might be “good science”—but it might also work to neuter the ineffable power that Blake called the tiger’s “fearful symmetry,”55 depriving the pharmakon of its evocative spell. The challenge before RCT researchers is to harness imagination while simultaneously diminishing its relevance: an impossible double bind.

Psychedelic research makes clear the inadequacies of RCTs, our gold standard for testing medical interventions. Though I have endeavored to evaluate the efficacy of ketamine in a variety of trials and have done so with positive results, I remain concerned about the compromises that were made, and not simply to methodological rigor. The medicine itself was denied the full opportunity to provide support given that its psychoactive, relational, and imaginal properties—all probably involved in its efficacy—were systematically deemphasized. RCT methodology, after all, is rooted in a biomedical system focused on developing biological products: physicalist, universal, and scalable interventions intended to address a circumscribed medical condition thought to be homogenous across diverse populations. Personalized treatments that harness imagination to promote general well-being or that unshackle the imagination entirely represent a very different way of doing things—often dismissed out of hand as placebo, folk medicine, or charismatic healing.

The major problem is that RCTs are captive to the same false earth most biomedical scientists regard as entirely physical. This doesn’t offer room for the imagination to take flight beyond materialism—on the contrary, it militates against it. The placebo response is accordingly dismissed as a quirk of human nature interfering with our capacity for objectivity, much like the miasma of subjectivity itself. Thus, the sterile methodology of RCTs: the double blind, randomization, active comparators, modulation of expectancy, and manualized researcher-subject interactions, all intended to minimize the power of suggestion and imagination.

Another viewpoint, also supported by biomedicine, is that the placebo response is a “valid” phenomenon recruiting “real” neural processes, with neuroimaging data,56 not surprisingly, indicating a distinct pattern associated with it. While it remains a source of interference in RCT design and something to curtail as much as possible, the placebo response is at least “real”—because associated with neural activity. Some researchers have gone so far as to suggest developing interventions that activate the brain in the same way. Perhaps these might be added to the countless other placebos already in medical use?

We return to our captivity in “matter.” I suggest moving beyond a reflexive recourse to neuro-materialism and recognizing the placebo response for what it is: a window into the profound impact that imagination, myth, and (un)reality have on our lives. Blake and Plato would have encouraged a similar perspective given the power they recognized in what we would call imagination, and what they might also call vision, noesis, or soul. We stand to learn how to inhabit this subtle dimension with greater skillfulness and intentionality. This will invariably change the way we approach testing and employing psychedelics, suggestogens, “super-placebos”—really anything else with which a relationship is possible.57

This is particularly relevant to drug addiction. Drug addiction emerges from an (un)real relationship with a substance comparable to the alchemical relationship one might have with a placebo. But with placebo, the relationship is healthier and “charged with greater grandeur.” It allows the imagination to consider other possibilities that are associated with flourishing, such as “normal serotonin levels” when taking a sugar pill in an antidepressant trial, but it is no more “real” than the fictions that surround a drug in addiction. One might even say that addiction touches on more reality because it, at least, involves a drug or act materially doing something, a predictable change in mood, faculties, or energy, while a sugar pill does nothing real at all, despite its neural signature.

The truth of a placebo is not in any real physiological effect but in a more subtle power. Placebo works to address suffering by harnessing our powers of imagination, conjuring an imaginal world of greater well-being. This outcome is truer, of course, to our inmost possibilities than are the (un)real shackles of addiction. A more healing relationship with (un)reality is made possible. A truer myth is enacted.

It was suggested earlier that Marcus developed an addiction because his imagination had become impoverished: so overheated in one direction, with the cocaine exalted beyond all reason, that he had lost the capacity to imagine anything else. The treatment seemed to work because it allowed Marcus to recognize and work toward a different possibility for himself, restoring to his imagination the freedom and creative power to radically reconsider what seemed the case. The centrality of the ketamine infusion to this process involved its capacity to materialize a new imaginary, rendering it experiential and therefore actual. The dream of reality under which he labored was thrown into ineffability for a moment, and he found opportunity to inhabit a more imaginative, more authentic way.

An entire troupe of therapists, physicians, and assistants was helpful for creating this world. A placebo response of impeccable stagecraft, with the close attention, deliberate framing, and careful orchestration reserved usually for the theater of surgery. And at its center—captivating his imagination deeply, yet also just one of many key players—was a powerful psychoactive drug. Among other things, ketamine produced robust subjective effects that allowed Marcus to inhabit with meaningful private relevance this emerging reality. It was no longer a wellness platitude or fantasy that “the present moment is a perfect gift.” An intimate truth was spun and experienced that was undeniable, even as he couldn’t quite articulate it. It resonated to the very depths of his being, dislodging the illusions of addiction, for at least the hour, from their pride of place.

That it was a psychoactive substance to do the trick is fitting given that drug addiction is a condition uniquely attached to the incarnations made possible by intoxication. Ketamine—a drug commonly used recreationally—was approached here in ways very different from how Marcus had engaged with cocaine. There was guidance from the start toward passing through whatever emerged, cultivating a mindful moment-to-moment equanimity. Not every seed takes root, but for Marcus it did. He received ketamine with profound freedom and emerged motivated for the work of silence ahead. Ketamine—despite its “abuse liability”—helped lead away from addiction instead of toward it, liberating his imagination rather than holding it captive: a psychedelic, a placebo, a moment like any other.

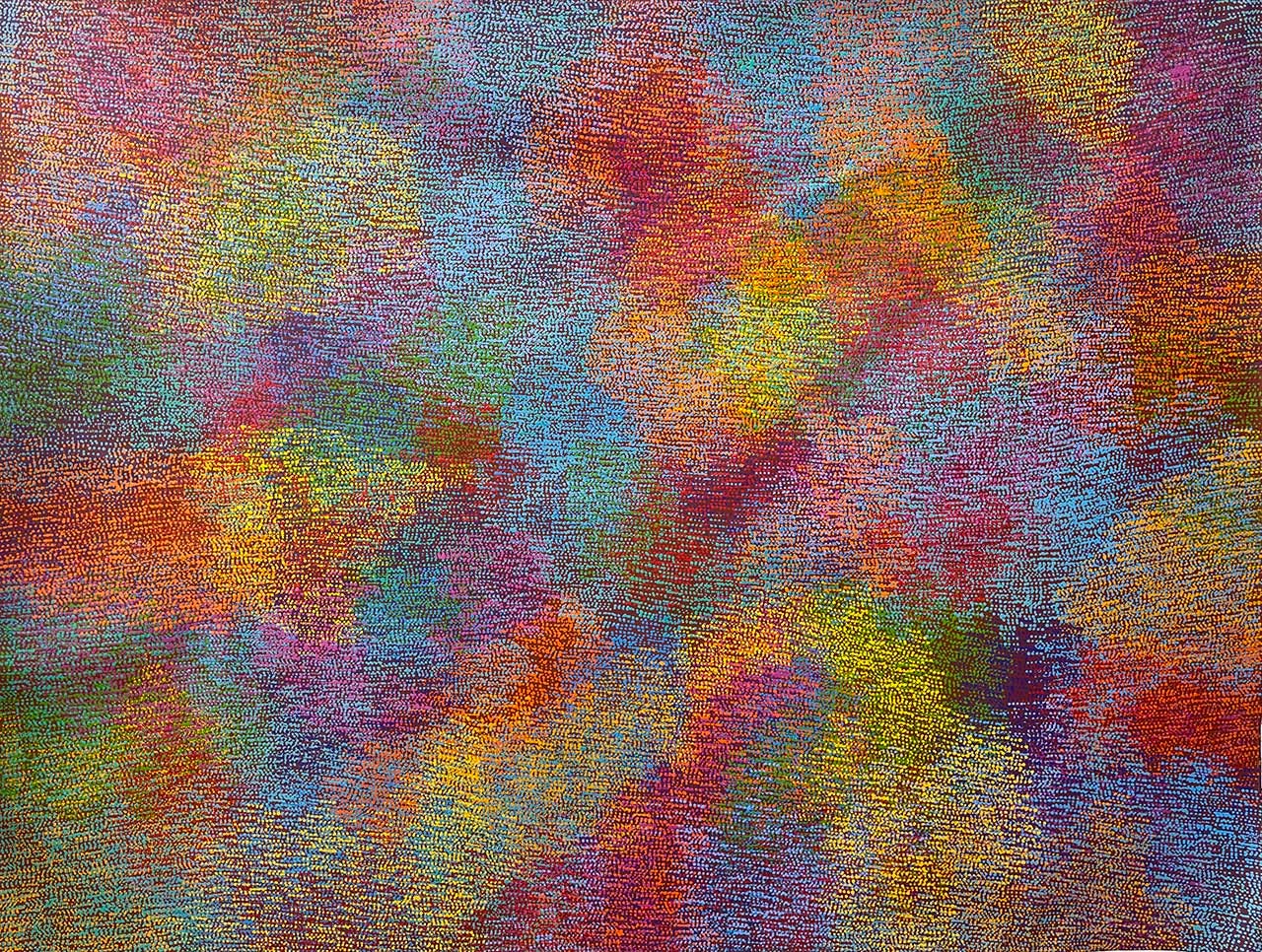

Michelle Cooper: Stunning stuff!

Click through here or on the first picture for more detail and how to purchase.

Remembering the Dunera

For more information on the "Dunera Boys", I found the two volumes published by Monash UP (Dunera Lives - "Profiles" and "A Visual Story") to be great reading.