Uncomfortable collisions with reality

Introducing my renamed podcasts. This is the best one I’ve done with the remarkable Jarrod Wheatley who’s finding ways to turn around a completely toxic arrangement with kids who’ve been removed from their parents. When I began the interview I didn’t fully understand just how extraordinary the situation is for the worst kids, but they’re kept in hotels with one-on-one round-the-clock supervision. They’ve cycled through so many homes and schools that they are regarded as hopeless with ‘successful’ transitions out of this situation of less than 10%. Yet by building a system around the idea that they need care from someone who can become a significant other, not someone who maintains their professional distance Jarrod has got the success rate an order of magnitude better — to around 85%.

The first video is a ‘taster video’ with the second one the full interview. The audio file of the full interview is here.

Taste: a second go

Last week I included an essay by Alan Jacobs on David Hume’s advice on how to detoxify social media. ‘Delicacy of taste’ was the key. In fact I published my own essay on a similar subject, replete with a phamous philosopher, though mine was the Great American William James. Anyway, I argued that the problem we were dealing included social media but it wasn’t just there and nor was it particularly new in the modern world. The problem was the commodification of culture. One might even say addiction as a culture.

The death of taste as a cultural resource is killing us. Fast food tastes yummy. It’s scientifically optimised to allow you to mainline unmediated yumminess. … The moderation of my craving for Maccas is a result of my having an acquired taste for better food.… This has been a process of acculturation including quite self-conscious self-directed acculturation and habituation. Thus for instance when I was in my twenties I decided I’d like to drink tea without sugar. It took about three weeks and having acquired my taste for sugarless tea I now enjoy tea more – I can taste so much more – and I find sugar in tea disgusting. I did the same for cappuccinos several decades later (though I still think the chocolate topping is an improvement on latte). …

Somehow as capitalism has munched its way through our civilisation, the core of the culture has bailed out on taste. We’re all consumers now and consumers have a human right to consume Whatever they Goddamn Please. And advertisers have a right to advertise and sponsor their little wallets off and entice our kids to go with their unacquired tastes. And of course it’s not just food. Our taste in culture and politics is the same. In each case with disastrous consequences. Not only is there now a huge industry in sugar hit ‘Upworthy’ linkbait journalism but political journalism is being hollowed out. This is partly because of the lack of resources, but mostly because cheap engagement – shock jock alarums and excursions and Gotcha – are profit maximising (input minimising and audience maximising) strategies.

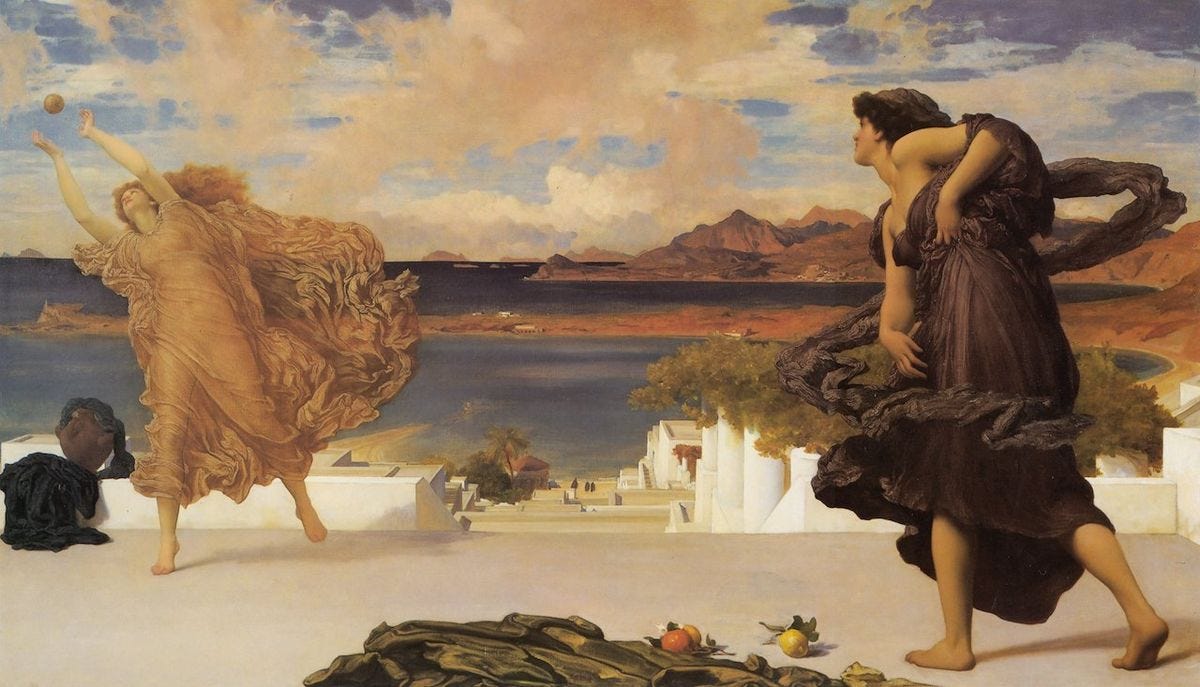

In this fascinating study, James Cutting:

varied the quality of art that the participants were exposed to. Half the treatment group of undergraduate students were repeatedly exposed to the critically respected work of John Everett Millais over a seven week lecture course and half to Thomas Kinkade, who is a good deal less respected, although much more popular.

They compared the opinions of this treatment group to a control group who had no repeated exposure. You can see from the graph below that there was a significant decline in participants' opinions of the work of Thomas Kinkade the more they saw the pieces, while the opposite holds true for John Everett Millais. The exposure effect only held true for the "good" art.

1666 and all that: Podcast of the week

I’ve occasionally filled you in on discoveries on the podcast circuit and here is one. It’s a duo of British historians talking about the 17th century. I mention two episodes below, but have since listened to several more which I’ve found equally fascinating. They include The Cromwell women and A crazed conspiracy. Meanwhile, the theme of A world on fire is governmentality — and even better (at least for me!) that word is not used — nor is Foucault anywhere in sight!

I’ve become fascinated with Venice’s constitution and its use of what might be called ‘meritocratic sortition’. I checked out this podcast because of its reference to Paolo Sarpi who was a big deal back in the 17th century. He was the cleric who helped the Venetians stand up to the papacy in their very own investiture crisis. (The Church had faced down the monarchs of Europe in the original investiture crisis 11th century gaining supremacy over them in appointing clergy.) But the Venetians appointed their own. They got excommunicated in the early 17th century but managed to hold the line. Anyway, Sarpi was arguably a proto-atheist and the most published Italian in England — ahead of Machiavelli and Dante which is setting a cracking pace. In any event, I recently learned that Venice prefigured the constitutional monarchies of Europe with its own elective monarch — the Doge — being hemmed in by his council of advisers. He had little more power than the monarch of Great Britain does today. What was fascinating about the podcast was its documenting ways in which the Venetian model was very much in the mind of the English parliamentarians who ended up going to war with the king in the 1640s. Here’s that episode.

And here’s a fascinating interview with the leader of a team publishing all of Cromwell’s output which provides a very rich portrait of Cromwell’s character as ‘one of a kind’ among puritans.

This changes everything: Ezra Klein on AI

A compelling column from Klein. There’s something histrionic about Klein’s voice that bugs me, but he’s a damn good journalist. And that voice does a pretty good job or amping up the drama of this column if you listen to him read it on his pod here.

In 2018, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Google — and not one of the tech executives known for overstatement — said, “A.I. is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.”

Try to live, for a few minutes, in the possibility that he’s right …

I find myself thinking back to the early days of Covid. There were weeks when it was clear that lockdowns were coming, that the world was tilting into crisis, and yet normalcy reigned, and you sounded like a loon telling your family to stock up on toilet paper. There was the difficulty of living in exponential time …

Since moving to the Bay Area in 2018, I have tried to spend time regularly with the people working on A.I. I don’t know that I can convey just how weird that culture is. And I don’t mean that dismissively; I mean it descriptively. It is a community that is living with an altered sense of time and consequence. They are creating a power that they do not understand at a pace they often cannot believe.

In a 2022 survey, A.I. experts were asked, “What probability do you put on human inability to control future advanced A.I. systems causing human extinction or similarly permanent and severe disempowerment of the human species?” The median reply was 10 percent.

I find that hard to fathom, even though I have spoken to many who put that probability even higher. Would you work on a technology you thought had a 10 percent chance of wiping out humanity?

Noam Chomsky: The False Promise of ChatGPT

Meanwhile Chomsky (and two others) provide a really crisp conceptual understanding of what ChatGPT is and isn’t and of the way in which human (and scientific) reasoning differs from our autocorrecting friend.

The human mind is not, like ChatGPT and its ilk, a lumbering statistical engine for pattern matching, gorging on hundreds of terabytes of data and extrapolating the most likely conversational response or most probable answer to a scientific question. On the contrary, the human mind is a surprisingly efficient and even elegant system that operates with small amounts of information; it seeks not to infer brute correlations among data points but to create explanations.

For instance, a young child acquiring a language is developing — unconsciously, automatically and speedily from minuscule data — a grammar, a stupendously sophisticated system of logical principles and parameters. …

The child’s operating system is completely different from that of a machine learning program. Indeed, such programs are stuck in a prehuman or nonhuman phase of cognitive evolution. Their deepest flaw is the absence of the most critical capacity of any intelligence: to say not only what is the case, what was the case and what will be the case — that’s description and prediction — but also what is not the case and what could and could not be the case. Those are the ingredients of explanation, the mark of true intelligence.

Timothy Snyder on ‘russophobia’

This is the text of my briefing of The United Nations Security Council this morning, 14 March 2023, for a session called by the Russian Federation to discuss "russophobia."

The premise, when we discuss "russophobia," is that we are concerned about harm to Russians. That is a premise that I certainly share. I share the concern for Russians. I share the concern for Russian culture. Let us recall, then, the actions this last year which have caused the greatest harm to Russians and to Russian culture. I'll briefly name ten.

1. Forcing the most creative and productive Russians to emigrate. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused about 750,000 Russians to leave Russia, including some of the most creative and productive people. This is irreparable harm to Russian culture, and it is the result of Russian policy.

2. The destruction of independent Russian journalism so that Russians cannot know the world around them. This, too, is Russian policy, and causes irreparable harm to Russian culture.

3. General censorship and repression of freedom of speech in Russia. In Ukraine, you can say what you like in either Russian or Ukrainian. In Russia, you cannot.

If you stand in Russia with a sign saying "no to war," you will be arrested and very likely imprisoned. If you stand in Ukraine with a sign that says "no to war," regardless of what language it is in, nothing will happen to you. Russia is a country of one major language where you can say little. Ukraine is a country of two languages where you may say what you like.

When I visit Ukraine, people report to me about Russian war crimes using both languages, using Ukrainian or using Russian as they prefer.

4. The attack on Russian culture by way of censoring schoolbooks, weakening Russian cultural institutions at home, and the destruction of museums and non-governmental organizations devoted to Russian history. All of those things are Russian policy.

5. The perversion of the memory of the Great Fatherland war by fighting a war of aggression in 2014 and 2022, thereby depriving all future generations of Russians of that heritage. That is Russian policy. It has done great harm to Russian culture.

6. The downgrading of Russian culture around the world, and the end of what used to be called "russkiy mir," the Russian world abroad. It used to be the case that there were many people who felt friendly to Russia and the Russian culture in Ukraine. That has been brought to an end by two Russian invasions. Those invasions were Russian state policy.

7. The mass killing of Russian speakers in Ukraine. The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine has killed more speakers of Russian than any other action by far.

8. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to the mass death of Russian citizens fighting as soldiers in its war of aggression. Some 200,000 Russians have are dead or maimed. This is, of course, simply Russian policy. It is Russian policy to send young Russians to die in Ukraine.

9. War crimes, trauma, and guilt. This war means that a generation of young Russians, those who survive, will be involved in war crimes, and will be wrapped up in trauma and guilt for the rest of their lives. That is great harm to Russian culture.

But perhaps the worst Russian policy with respect to Russians is the last one.

10. The sustained training or education of Russians to believe that genocide is normal. We see this in the president of Russia's repeated claims that Ukraine does not exist. We see this in genocidal fantasies on Russian state media. We see this in a year of state television reaching millions or tens of millions Russian citizens every day. We see this when Russian state television presents Ukrainians as pigs. We see this when Russian state television presents Ukrainians as parasites. We see this when Russian state television presents Ukrainians as worms. We see this when Russian state television presents Ukrainians as Satanists or as ghouls. We see this when Russian state television proclaims that Ukrainian children should be drowned. We see this when Russian state television proclaims that Ukrainian houses should be burned with the people inside. We see this when people appear on Russian state television and say: "They should not exist at all. We should execute them by firing squad." We see this when someone appears on Russian state television and says "we will kill 1 million, we will kill 5 million, we can exterminate all of you," meaning all of the Ukrainians.

The claim that Ukrainians have to be killed because they have a mental illness known as "russophobia" is bad for Russians, because it educates them in genocide. But of course, such a claim is much worse for Ukrainians.

This brings me to my second point. …

Lovely! Maximise the video and watch in wonder

Treaties, treaties everywhere

I wish I didn’t have so many misgivings about this, but there you go. First, a refresher from Inside Story:

Treaties are accepted around the world as a means to resolve differences between Indigenous nations and those who colonised their lands. They have been struck in North America and New Zealand and are being negotiated in Canada. Australia is an outlier: no treaties were negotiated when the British arrived, or at Federation, or in the years since then. Without any formal treaty setting out how to share the land, many First Nations peoples believe Australia’s moral and legal foundations are, in NT treaty commissioner Mick Dodson’s words, “a little… shaky.”

Many types of agreements have been negotiated between First Nations peoples and governments, but international law sets a clear standard for what makes an agreement a treaty. Treaties are formal instruments reached through a process of respectful negotiation in which both sides accept a series of responsibilities. They provide redress for past injustices, acknowledging that Indigenous peoples were prior owners and occupiers of the land and, as such, retain a right to self-government.

At a minimum, a treaty recognises or creates structures of culturally appropriate governance and establishes means of decision-making and control. Treaties are more than service-delivery agreements and provide more than symbolic recognition.

So, where are the states and territories up to?

You can read all about that by clicking the blue “More Here” button below. Is this a good idea? Who knows? Indigenous policy goes through its various cycles — progressive and conservative — and we endlessly prefer performing our good intentions to knowing what we’re doing — a preference that goes back to Arthur Phillip. There’s certainly lots of activity. Meanwhile, whenever I see the word ‘elected’ I worry. If Indigenous representatives are elected (as opposed to sampled from the community as juries are) then that more or less guarantees that the whole thing will be sorted by an Indigenous political class in negotiation with the incumbent non-Indigenous political class. It all reminds me of the great Bill Stanners misgivings about the equal and opposite agenda. Over to you Bill Stanner — writing in 1959.

The policy of assimilation is meant to offer the Aborigines a ‘positive’ future—absorption and eventual integration within the European community. Does it involve a loss of natural justice for the living Aborigines? No one answers. [Difficult] cases …are irritating distractions from loftier things. The policy assumes that the Aborigines want, or will want, to be assimilated; that white Australians will accept them on fair terms; that discrimination will die or can be controlled; that, in spite of the revealed nature of the Aborigines and their culture, they can be shaped to have a new and ‘Australian’ nature. The chauvinism is quite unconscious. The idea that the Aborigines might reject a banausic [utilitarian] life occurs to no one. The unconscious, unfocused, but intense racialism of Australians is unnoticed. The risk of producing a depressed class of coloured misfits is thought minimal, although that is the actual basis from which ‘assimilation’ begins. The aspirations are high; the sincerity is obvious; everyone is extremely busy; a great deal of money is being spent; and the tasks multiply much faster than the staffs who must do the work. In such a setting a certain courage is needed to ask if people really know what they are doing.

Indeed.

Chinese communism and Nietzsche

Pretty Interesting

Mao Zedong himself had been exposed to Nietzsche before Marx. Late Qing reformers had picked up Nietzsche’s ideas as they visited Japan and Germany; the young Mao devoured their work. The archives preserve Mao’s first writing on Nietzsche, scribbled in the margins of Cai Yuanpei’s translation of Friedrich Paulsen’s A System of Ethics. Mao admired the neo-Kantian Paulsen but had an instinctual sympathy with Nietzsche’s view that traditional morality needed to be upended. Only by harnessing powerful, buried forces did Mao see a path toward a new world.

The artists and thinkers of the early Republican period were likewise enthralled by Nietzsche, the rebel philosopher who believed in the power of culture. For those focused on sweeping away the dust of feudal China, his nihilistic attack on tradition and call to overcome slave morality translated well into the post-imperial context. It is no wonder that Nietzsche was idolized by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, who would go on to found the Communist Party. …

The goal of Jiang’s art was not to push aside all that came before; it was to absorb and transform it. In her vision, the dominant must not impose ressentiment on the dominated—to do so would be aesthetically disgusting. Jiang’s heroes were personalities to aspire to, not moral battering rams. This vision was accomplished by nurturing individual and collective creativity, pursuing technical perfection, and tolerating the transgression of traditional ethics.

These were Jiang’s lessons for China and artists. The tyranny of irony can be cast off by heroic sincerity. Mythology can become a true ethos. By giving up on victimhood, one gives up on misery. Without the narcissistic compulsion for representation of one’s petty flaws, it is possible to imagine true heroes.

The pinnacles of such art require the same kind of mass mobilization as any other achievement of modern society. As far back as the 1920s, directors like Fritz Lang commanded masses of people and machines with a firm hand to create masterworks of cultural production. But this apparent stiffness shelters the artist’s disruptive impulse. Jiang tolerated the transgressions of once-in-a-lifetime geniuses like Xue Jinghua or Yu Huiyong for a reason. The real crime she did not allow was the aestheticization of petty transgressions into ideals.

Justin Murphy on Agnes Callard’s mid-life crisis

Ethical theorist gets horny

If a married man of 35 "aspires" by opening his heart to a student in her twenties, it is rightfully mocked as an immature way of coping with senescence. The "midlife crisis" meme testifies to this obvious pattern. But when a writer for The New Yorker catches wind of a female professional doing something that men are notorious for doing in a pathetic fashion, well now it must be fascinating, brave, and heroic. I suspect the author and Callard both drink this Kool-Aid because, otherwise, the simple and direct reading of this article is shockingly cruel to Callard. And Callard on Twitter was pleased with it.

As I read this story, I see no reason why the null hypothesis should not be "midlife crisis" : Leaving her spouse for a younger man is just basic, insecure selfishness. It's not uncommon in our rational and secular world. Surely this must be the base case for what's going on here. So I expected the article to furnish interesting evidence of something different. But there is nothing different. Even Callard's words, they don't really even purport to say anything different. She just says them grandiloquently.

It's possible Callard is saying and doing something different, and the author of the article simply failed to reflect it, but I doubt that because Callard is quoted at length. Her own words essentially boil down to: "The good life means pursuing my appetites and using the excess heat to generate words." All the power to her, but this strikes me as a rather weak ethical theory. Go look at her words in the article and tell me with a straight face that there's anything more sophisticated going on there. Even her collaborator Robin Hanson made a similar observation. …

Anyway, she eventually grows dissatisfied with Arnold and now they're talking about going polyamorous. "I think I never realized how fundamentally selfish I was before I met Arnold... I’m just really not able to be much less selfish than I am," says Callard.

Can you believe it? All of this time and energy, just for one big, round-trip flight back to the appetites. She pretty much admits that her decision to leave her husband for a graduate student was intellectually an error or miscalculation, caused by her appetites overriding her reason. But the implication is not that she must return to an inquiry about her appetites, and perhaps a restructuring of her attitudes and habits toward a greater alignment with virtue, no—that would not be fun. That would not be horny. The implication is that she should go find new romantic excitements, of course. Frankly, why would she come to any other decision?

great Ruzzian link there.. but I am going to type about sugar in my tea. I don't remember the process by which I removed it, but it is disgusting,

this very morning I discussed with my daughter why the coffee in the house is so disgusting at the moment, and I said its because we are still getting through the cheapest ground coffee I bought when you teenagers put sugar in everything, including the coffee and this batch might be a particularly bad batch.... a year ago i showed them how to mokka-pot arabica and have it sweet as with no sugar... congrats I said you are officially a coffee snob.