A 60 percent chance of a downpour?

Why can’t economists forecast better? The short answer is they don’t try.

The four-day weather forecasts of today are as good as one-day forecasts 30 years ago. Economic forecasts have been consistently lousy throughout the period with no sign of improvement. And yet there's evidence they could improve, though probably not by as much. How could they do that? By taking a leaf out of the weather forecasters' book. We discuss Ben Bernanke's review of the Bank of England's forecasting and ask why Philip Tetlock's work on superforecasting has received so little attention. The answer is "no reason", it's just that he's not an economist. And the profession of economics puts its store in the cleverness and technical prowess of its forecasters, rather than in their ability to consistently outperform other forecasters.

But Philp Tetlock has shown how we can fix all that.

If you'd prefer to access the audio, it's here:

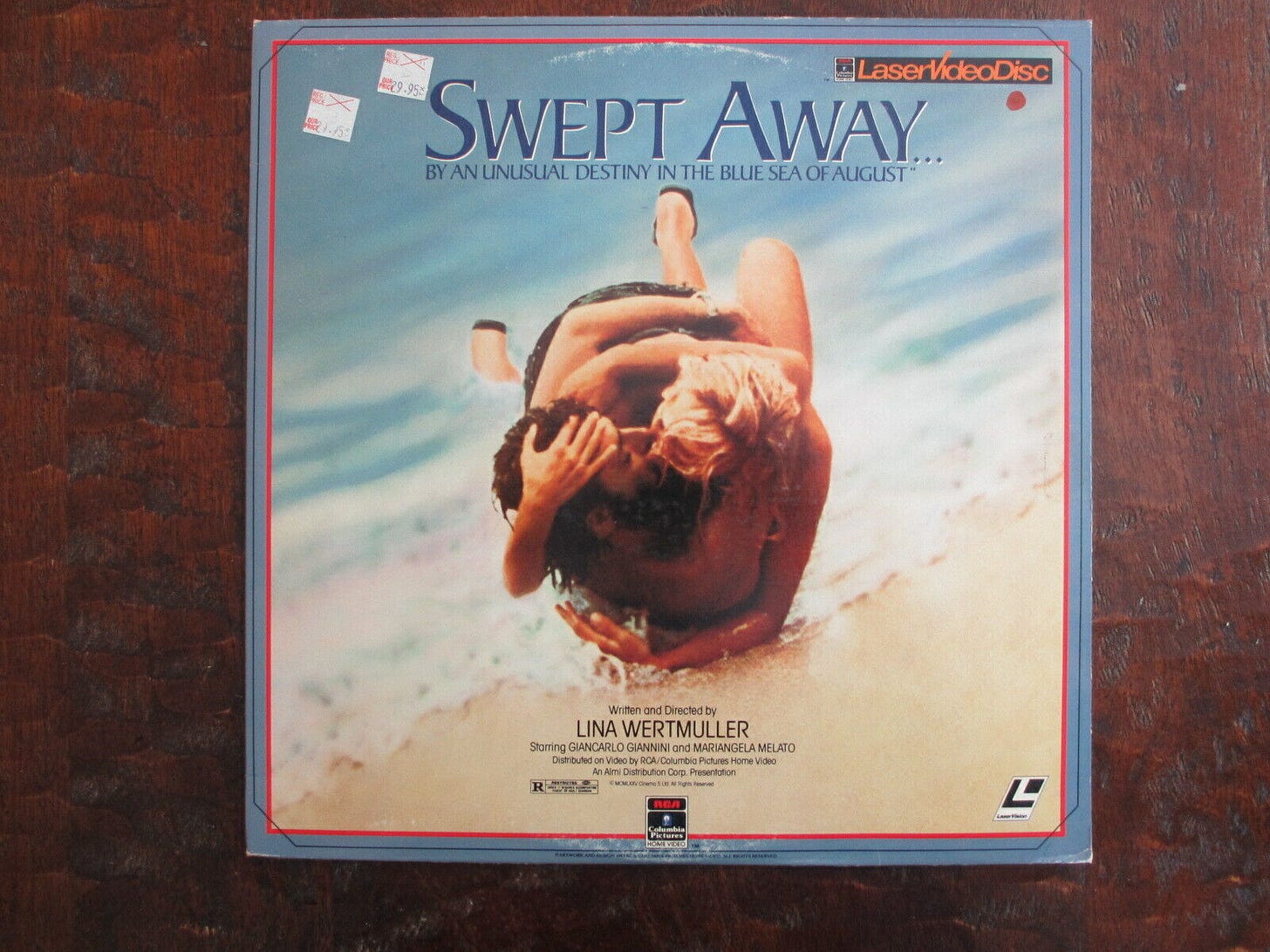

Swept Away: a great film you may REALLY HATE!

I remember seeing Swept Away when it came out in the mid-1970s at an arthouse cinema. I was completely gobsmacked by it. I have wanted to watch it ever since but a few years ago had to make do with eight blurry snippets on YouTube. This was when Madonna’s lamentable remake reminded me of it. (I’m taking the lamentable part on trust. Absolutely everyone panned it.)

Anyway, when trying to find it online having recommended someone else watch it, I found the whole thing — with English subtitles here. I predict it will never be on SBS. It is about as ideologically confronting as it’s possible to be for someone of my weakness of character (see next story in this newsletter on “Solow on Hayek, Friedman and neoliberalism”).

This contemporary review gives you the story arguing that the film:

resists the director's most determined attempts to make it a fable about the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and persists in being about a man and a woman. On that level, it's a great success, even while it's causing all sorts of mischief otherwise. … It involves a bearded sailor, who's a fervent subscriber to the macho school of Italian thought, and a beautiful young blond, who's the plaything of her rich husband. …

Late one day, the woman decides to go out in a dinghy and orders the sailor to operate the boat. He protests that it's dangerous to leave so late in the day, but she insists. The engine fails, they're cast adrift for days and when the sailor succeeds after great effort in catching a fish, she throws it overboard because it smells.

Eventually they land on a deserted island, and the tables in their relationship begin to turn with a vengeance. Consider. Ashore and on board the yacht, the woman held the unquestioned upper hand because of her husband's money. But on the island, it's the man, with his survival skills and (most controversial, this) his very masculinity, who's the dominant figure. He orders her around. If she wants to eat, she'll have to do his laundry. She screams, she sulks, she argues, but she loses. And she finds herself powerfully attracted to the situation; she's been spoiled so long, it's almost a relief to be ordered around.

It's here that the movie begins to venture into philosophical and sexual mischief-making, because although Lina Wertmuller is a leftist, she is not, apparently, a feminist.* She seems to be trying to tell us two things through the episodes on the island: (1) that once the corrupt facade of capitalism is stripped away, it's the worker, with the sweat of his back, who deserves to reap the benefit of his own labor, and (2) that woman is an essentially masochistic and submissive creature who likes nothing better than being swept off her feet by a strong and lustful male. This is a notion the feminists have spent the last 10 years trying to erase from our collective fantasies, and it must be unsettling, to say the least, to find the foremost woman director making a whole movie out of it. And Wertmuller doesn't kid around: Her shipwrecked couple gradually works its way into a sadomasochistic relationship that makes "The Night Porter" look positively restrained. The more the woman submits, the more ecstasy she finds - until finally she's offending the hapless Sicilian by suggesting practices he can't even pronounce.

I liked these observations in the NYT on Wertmuller’s death at 93 in 2021.

In the broad sense, Ms. Wertmüller was a political filmmaker, but no one could ever quite figure out what the politics were. A lively sense of human limitations tempered her natural bent toward anarchy. Struggle was noble and the social structure rotten, but the outcome was always in doubt.

This segment of another interview is also instructive.

When Swept Away was first released, it was met with quite a bit of criticism from feminists who saw the film as unnecessarily violent against your female lead, Mariangela Melato. [This is ridiculously euphemistic — the objection was that the plot is about the last thing a feminist would want to naturalise — a woman falling in love with a man who is physically and sexually abusing her.] In hindsight, it seems like a strange criticism that misses the political dimensions of the film. Can you perhaps talk about your feeling about that line of criticism?

LW: I’ve never understood feminists who criticized Swept Away but when you make a film, people are free to see what they want and can express every feeling the movie opens in their mind and hearts. From my point of view, there’s not a message against women’s freedom. It’s the opposite to me. My leading female character is a free woman, she makes choices following her own will.

Anyway, I was blown away by it all over again when I watched it earlier this week.

* According to some reports Wertmuller denied she was a feminist, but this article in the Conversation simply presumes, as I had before checking this out, that she was. Here’s Lina Wertmuller saying she’s not a feminist, but of course it all depends on what you mean by that word.

Is Lucy Letby Innocent?

Probably not, but seemingly reasonable people wonder

I publish this with trepidation, but then I know how capricious law can be. This is the system that puts people in jail even as they await their appeal. This is the system which, in 1960 ruled that an accused Jamaican black man appealing to the House of Lords can’t introduce evidence that the little girl who was raped and killed said before she died that a white man had raped her. Why? Because it was hearsay.

Anyway, at least on a cursory view the article explains:

I’m not saying that I know that Lucy Letby is innocent. As a scientist, I am saying that this case is a major miscarriage of justice. Lucy did not have a fair trial. The similarities with the famous case of Lucia de Berk in the Netherlands are deeply disturbing.

The Machiavellians: a review

James Burnham’s The Machiavellians is a great book and one of the best on political thought I’ve ever read. I learned about it from an interview with Curtis Yarvin. I'm no fan of his recipes for the world, which suffer from the usual motivated impatience of the ideologue. But I was gobsmacked by Burnham's clear insight into why 9/10ths of the worlds political speech is empty wish fulfillment.

I sent it to a few friends who said how 'conservative' it was. It struck me that, to the contrary it conformed to at least one test of a really great take on something, it had insights aplenty whatever your ideological preferences. I proposed it as the ur-text for the 'alt-centre' here. He provides a good review of all four of Burnham’s Machiavellians. Meanwhile this is the passage in Burnham that blew me away:

It is easy to dismiss [Dante’s] De Monarchia as having a solely historical, archaic, or biographical interest. … We seldom, now, talk about “eternal salvation” in political treatises; there is no more Holy Roman Empire; scholastic metaphysics is a mystery. … All this is so, and yet it would be a great error to suppose that Dante’s method, in De Monarchia, is outworn. His method is exactly that of the Democratic Platform with which we began our inquiry. It has been and continues to be the method of nine-tenths, yes, much more than nine-tenths, of all writing and speaking in the field of politics.

[The method] may be summarized as follows:

There is a sharp divorce between what I have called the formal meaning, the formal aims and arguments, and the real meaning, the real aims and argument. … The formal aims and goals are for the most part or altogether either supernatural or metaphysical-transcendental—in both cases meaningless from the point of view of real actions in the real world of space and time and history; … A systematic distortion of the truth takes place. And, obviously, it cannot be shown how the goals might be reached, since, being unreal, they cannot be reached.

From a purely logical point of view, the arguments offered for the formal aims and goals may be valid or fallacious; but, except by accident, they are necessarily irrelevant to real political problems, since they are designed to prove the ostensible points of the formal structure—points of religion or metaphysics, or the abstract desirability of some utopian ideal.

The formal meaning serves as an indirect expression of the real meaning—that is, of the concrete meaning of the political treatise taken in its real context, in its relation to the actualities of the social and historical situation in which it functions. But at the same time that it expresses, it also disguises the real meaning. We think we are debating universal peace, salvation, a unified world government, and the relations between Church and State, when what is really at issue is whether the Florentine Republic is to be run by its own citizens or submitted to the exploitation of a reactionary foreign monarch. … We believe we are disputing the merits of a balanced budget and a sound currency when the real conflict is deciding what group shall regulate the distribution of the currency. We imagine we are arguing over the moral and legal status of the principle of the freedom of the seas when the real question is who is to control the seas.

But I recommend the longer post you can click through to below which provides you with a summary of each of the four modern Machiavellians surveyed by Burnham. All very well worth knowing about.

Gratitude for being in the presence of abundance

For some stunning pictures, have a look at the catalogue.

Some funny writing: ‘Section guy’ for president

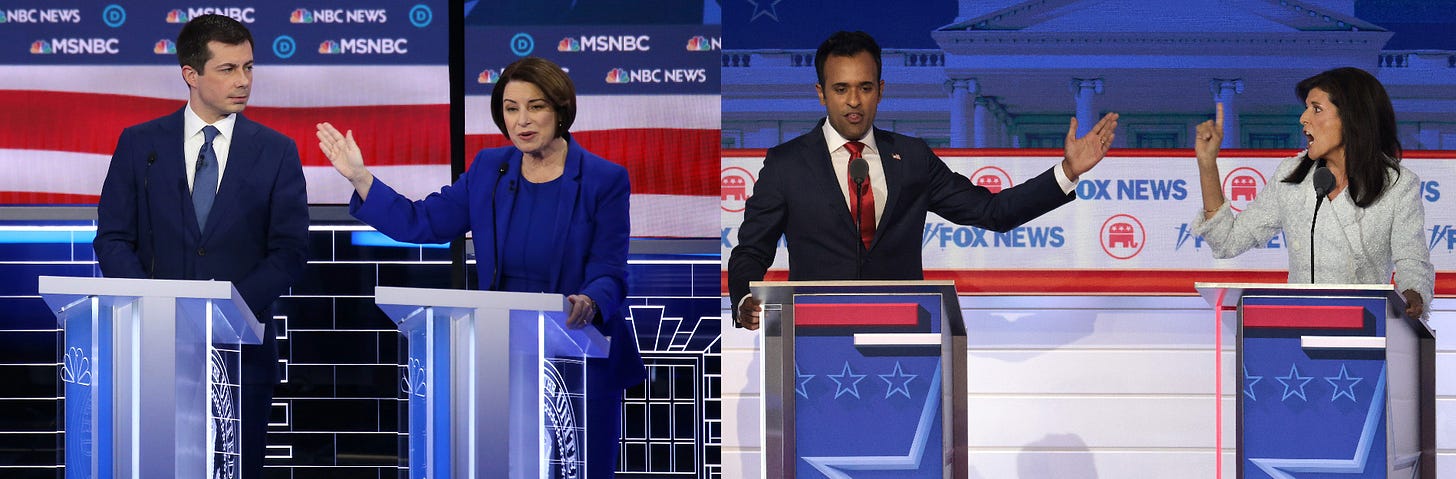

When Vivek Ramaswamy and I were undergraduates at Harvard, students would sometimes talk about the scourge of “section guy.”

“Section guy” wasn’t a specific person, but an archetype — that guy² in your discussion section who adores the sound of his own voice, who thinks he’s the smartest person on the planet with the most interesting and valuable interpretations of the course material, and who will not ever, ever, ever shut up.

“Be nice to that overeager Gov 20 section guy, for like many on Congress’ current roster, he may someday take the well-traveled road from Harvard to the Hill,” The Harvard Crimson warned in 2010, just a few years after we both graduated.

Well, now section guy is running for president.

Vivek was two years behind me, and I didn’t know him, which is a little strange given that we were both college Republicans and we were both obnoxious little shits.³ As I have watched his presidential campaign proceed, I have worried a little that my animus towards him — the strong desire I feel to punch him in his stupid fucking face — had to do with my own baggage from late adolescence; that when I watched him, I saw bits of my obnoxious teenage self that I have worked very hard to bury, and that my visceral revulsion was really more about me than it was about him.

But last night’s debate — in which I watched several former governors react to Vivek on a debate stage in the same way that I do in my living room — disabused me of this notion. Me wanting to punch someone in the face might be a ‘me’ problem. But if Mike Pence, Chris Christie, Nikki Haley and I all want to punch the same person in the face? That surely has to be a him problem.

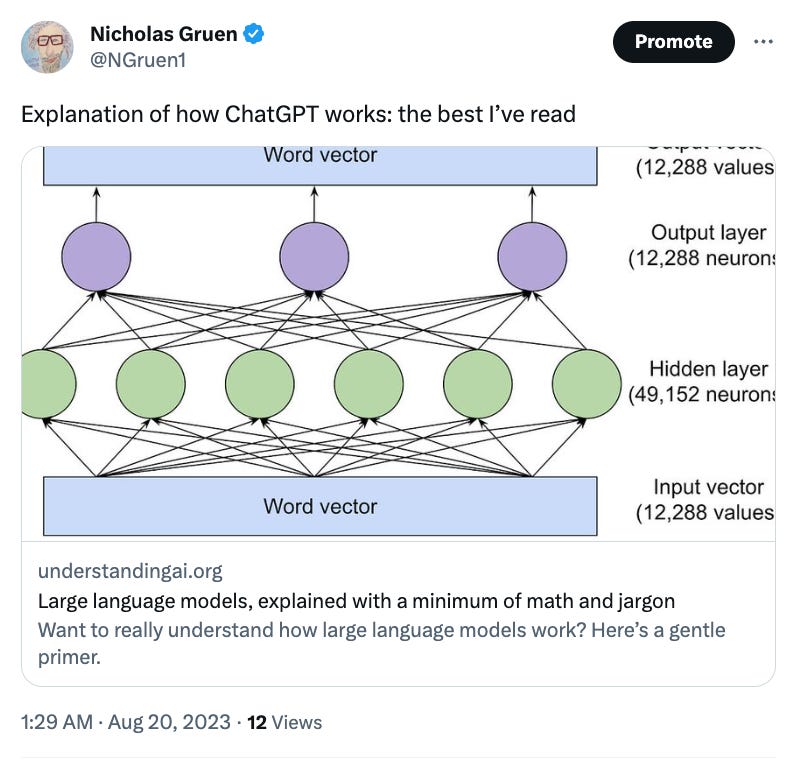

LLMs as a service: AutoGPT and its friends

The LLM revolution rolls on. After I extracted the passages below from Clayton O’Dell New Atlantis I saw Stephen Wolfram musing on the same thing with his own software. “What if we could take LLM functionality and “package it up” so that we can routinely use it as a component inside anything we’re doing? Well, that’s what our new LLMFunction is about.” In any event, here’s Clayton O’Dell:

With ChatGPT, which attracts most of the attention of AI news right now, it’s easy to conceive of it as simply a tool. … But the shiniest new toys in AI are the applications of ChatGPT that act as “agents” such as AutoGPT and AgentGPT. Curious about their possibilities, I played around with each of them for a couple hours, and the results were incredible — scary but incredible. Whatever they are, they are more than simply a tool. …

For the average computer science student, the process of setting up AutoGPT is fairly simple. … The possibilities seemed limitless. Currently looking forward to my travels to France for machine learning research, I decided to ask AutoGPT about planning restaurant reservations. From the simple line, “Find a high-rated restaurant available for dinner for two next Friday in Lyon, France,” AutoGPT created a to-do list of tasks and got started. Not only did the tasks include research of the best restaurants and their online availability, they also included using my email address to reserve the restaurant, with promises to check back in closer to the reservation date. Nowhere did I ask it to actually book the restaurant, but it did so anyway. It’s a good thing my new AI assistant knew what I really wanted to ask, I guess?

In accomplishing these tasks, I watched as the autonomous chatbot ran into dead ends with websites and altered the code until it ran successfully. For example, when queries of French restaurants on Google did not provide suitable results, the program updated the code it was using in order to try again with a new search engine and new queries, updating the file in real time and running it again. …

The options for what can be done with AutoGPT seem to skew away from what the creators believe should be done. “Continuous mode” is available with just one command, but deemed “potentially dangerous” as it “may cause your AI to run forever or carry out actions you would not usually authorize.” What? The ability to carry out actions I would not usually authorize?

At this point, my fears heightened at what I unknowingly just deployed to destroy my computer. The website goes on to note that a virtual machine, a way to create an isolated testing environment on your computer, is strongly recommended to ensure “high security measures to prevent any potential harm to the main computer’s system and data.” Thankfully, my caution overpowered my curiosity, and by deleting everything I had downloaded and restarting my computer, I avoided any security breach or out-of-control AI agent. Phew.

Solow on Hayek, Friedman and neoliberalism

Robert M. Solow is one of the best economists I know of. He is also very funny. He’s also a Good Guy. I love his introduction of himself as a centrist sandwiched between Milton Friedman and John Kenneth Galbraith he chose to describe his centrism as weakness of character. It’s a very funny passage which I quote by way of introduction to my outline of my own views as a conservative, liberal social democrat. I love his conclusion. “Sometimes I think it is only my weakness of character that keeps me from making obvious errors.”

Be that as it may, I came across this review of one of the first substantial books to document the history of Hayek’s brainchild, the Mont Pèlerin Society. It’s an excellent introduction to the Good Hayek and the Bad Hayek, and the Good Friedman and the Bad Friedman.

What seems off-key (at least now, at least to me) is that they all felt themselves to be in a struggle between free markets and collectivism (or socialism) with no possible intermediate stopping point. That is the meaning of “the road to serfdom.” Even earlier, in 1934, Knight had written that it would be only a “decade or two at the most before we see the end of anything like freedom of inquiry in the United States and all the rest of the liberal European world where it has not already been sunk.” Wilhelm Röpke, a German sociologist-economist of little account, but a friend and ally of Hayek’s, thought that it was time to “recognise that the case of Liberalism and Capitalism is lost strategically even where it is still undefeated tactically.” Simons wrote in 1938 “that the main direction of New Deal policies is toward authoritarian collectivism.” …

Under Milton Friedman’s influence, the free-market ideology shifted toward unmitigated laissez-faire. Whereas earlier advocates had worried about the stringent conditions that were needed for unregulated markets to work their magic, Friedman was the master of clever (sometimes too clever) arguments to the effect that those conditions were not really needed, or that they were actually met in real-world markets despite what looked a lot like evidence to the contrary. He was a natural-born debater: single-minded, earnestly persuasive, ingenious, and relentless. My late friend and colleague Paul Samuelson, who was often cast as Friedman’s opponent in such jousts, written and oral, once remarked that he often felt that he had won every argument and lost the debate.

As for relentlessness: Professor Friedman came to my department to give a talk to graduate students in economics. The custom was that, after the seminar, the speaker and a small group of students would have dinner together, and continue discussion. On one such occasion I went along for the dinner. The conversation was lively and predictable. I had a long drive home, so at about ten o’clock I excused myself and left. Next morning I saw one of the students and asked how the rest of the dinner had gone. “Well,” he replied, “Professor Friedman kept arguing and arguing, and after a while I heard myself agreeing to things I knew weren’t true.” I suspect that was not the only such occasion. …

It is true that Friedman could be infinitely subtle in criticizing a student’s empirical work; but he could also be rather lax in finding support for his own opinions. To take one example, Friedman proposed abolishing the Food and Drug Administration because the harm done by its excessively cautious delays in approving new drugs outweighed the dangers that would come from simply making drugs freely available on the open market. How could he, or anyone, possibly know that? One can indeed imagine an immensely complicated empirical study, requiring all sorts of assumptions and approximations, the outcome of which would inevitably be clouded by complexity, guesswork, and great uncertainty. But that would win no hearts or minds. Friedman’s confident assertion just sounds like fact-based knowledge. A different sort of person would have looked for ways to speed up the FDA’s approval process.

Everyone has known for a long time that a complicated industrial economy is either a market economy or a mess. The real issues are pragmatic. Which of the defects of a “free,” unregulated economy should be repaired by regulation, subsidization, or taxation? Which of them may have to be tolerated (and perhaps compensated), at least in part, because the best available fix would have even more costly side-effects? To the extent that the MPS circle made that kind of policy discussion more difficult to have, it did the market economy a disservice.

Noah Smith asks the question at the back of my mind

Then he explains the Chinese economic situation

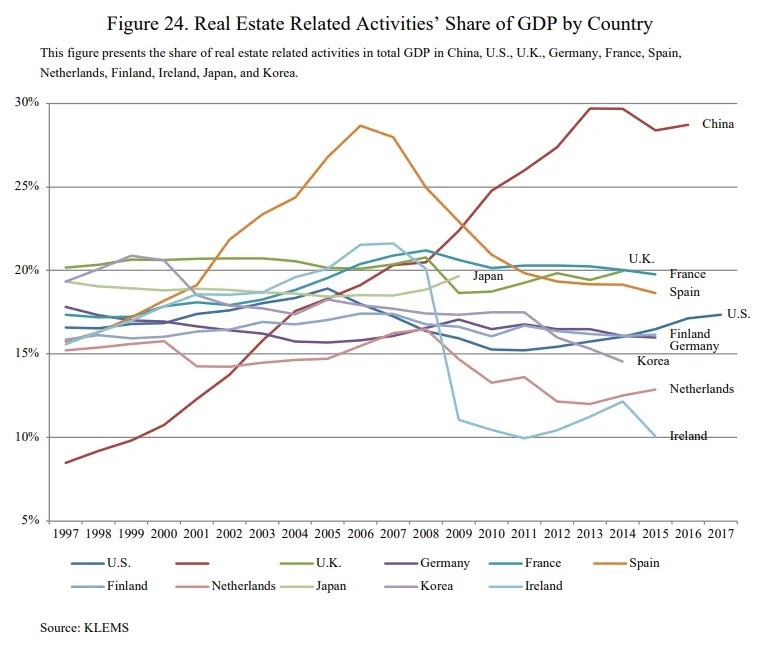

Though this graph is the picture worth a thousand words

Anyway, at the same time that China’s pivot to real estate was slowing its productivity growth, it was also giving rise to a gigantic bubble. Because real estate was also Chinese people’s main savings vehicle, people were pouring their life’s savings — and their parents’ life’s savings, and their grandparents’ life’s savings — into buying apartments that they expected to serve not only as a place to live but as their nest egg for retirement (or possibly into buying real-estate-backed bonds from shadow banks). …

So even as the pivot to real estate was adding to a long-term slowdown in China’s growth, it was also generating a bubble that would eventually cause an acute short-term slowdown as well. If there’s a grand unified theory of China’s economic woes, it’s simply “too much real estate”. …

The real story is going to be more complicated than that, but if you want a quick-and-dirty explanation of why China’s crash is on everyone’s minds right now, I think the story of the pivot to real estate is probably the best simple story you can tell.

The kind of situation you’d try to avoid in the 14th century

I was wrong about trigger warnings

Has obsession with trauma done real damage to teen girls?

In 2008, when I was a writer for the blog Feministe, commenters began requesting warnings at the top of posts discussing distressing topics, most commonly sexual assault. Violence is, unfortunately and inevitably, central to feminist writing. Rape, domestic violence, racist violence, misogyny—these events indelibly shape women’s lives, whether we experience them directly or adjust our behavior in fear of them.

Back then, I was convinced that such warnings were sometimes necessary to convey the seriousness of the topics at hand (the term deeply problematic appears a mortifying number of times under my byline). Even so, I chafed at the demands to add ever more trigger warnings, especially when the headline already made clear what the post was about. But warnings were becoming the norm in online feminist spaces, and four words at the top of a post—“Trigger Warning: Sexual Assault”—seemed like an easy accommodation to make for the sake of our community’s well-being. We thought we were making the world just a little bit better. It didn’t occur to me until much later that we might have been part of the problem.

The warnings quickly multiplied. When I wrote that a piece of conservative legislation was “so awful it made me want to throw up,” one commenter asked for an eating-disorder trigger warning. When I posted a link to a funny BuzzFeed photo compilation, a commenter said it needed a trigger warning because the pictures of cats attacking dogs looked like domestic violence. Sometimes I rolled my eyes; sometimes I responded, telling people to get a grip. Still, I told myself that the general principle—warn people before presenting material that might upset them—was a good one.

Two responses to the Weird Medieval Guy’s tweet above

Here come the female Andrew Tates

“Men do not love you, okay? So stop thinking that they do. They tolerate you. They lust you. That’s it.”

The YouTube influencer SheRa Seven’s advice for young women is as sharp as the wings of her black eyeliner. To single ladies, she offers the following on sex: “The longer you hold off, the more that he will like you.” To married ones: “Don’t give it up every time he want it. Make him wait, make him work for it still. Gotta make him chase!”

This chaste strategy, promoted by straight-talking female influencers with lush lips and eyelash extensions, is everywhere at the moment, proliferating under TikTok hashtags such as #feminineenergy and #lawofattraction. The women who swear by it have been compared with the pick-up artist and alleged human trafficker Andrew Tate, which has provoked a whole host of articles explaining why this comparison is extremely wrong and offensive. But it’s easy to see how these women might serve as a sort of funhouse mirror to the manosphere pick-up artists.

Why the constitution renders Donald Trump ineligible to hold office

From the department of oops

George Eliot is a man of genius. Novels by male authors are more in keeping with the actual world, have a wider outlook, and are more profitable than the best novels by women. Adam Bede is one of the best of this best class of novels.

The Economist, review of George Eliot (AKA Marian Evans) first novel Adam Bede, 1959.

The Ukraine War

I have no independent way of assuring you this is well informed and judged commentary on the Ukraine war, but it passes my sniff test, particularly given the humility with which it offers its thoughts.

NATO’s decision to promise membership to Ukraine — but only once the war is over — has perversely increased Russia’s incentive to continue fighting, especially with the possibility of a Trump victory in next year’s American election. The longer Russia maintains its aggression, the longer Ukraine remains outside NATO; a Trump presidency might well herald a fracturing of support for Ukraine among its allies. And as long as Putin remains in power, and as long as his army can sustain the ongoing significant losses, Russia is likely to remain in the war.

Along the way, analysts have got many things wrong. From predicting Russia wouldn’t attack (just before it did), to assuming a quick breakdown of Ukraine’s defences and disintegration of its government, to making optimistic predictions about the instability of Putin’s regime: real developments continued to confound the futurology so prevalent in the commentary.

I mustn’t exclude myself from this critique. A month into the conflict, I published a short piece outlining possible scenarios about how this war would end. Like others, I couldn’t imagine the conflict still raging a year and a half later. Like others, I underestimated Russia’s economic resilience in the face of sanctions, although the full impact of these measures is only being felt now. “Given the sanctions regime,” I wrote, Russia will retain the capacity to resupply its troops for “months at best.” That was way off the mark.

Carmen Amaya: 'the greatest Flamenco dancer ever'

More here

Because we are newspapermen: Walter Lippmann on a life in commentary

Delivered to the National Press Club on Lippmann’s 70th birthday, Sept 23rd 1959 and published in The Atlantic, January, 1960.

THE job of a Washington correspondent has changed and developed and grown in my own lifetime, and if I had to sum up in one sentence what has happened, it would be that the Washington correspondent has had to teach himself to be not only a recorder of facts and a chronicler of events but also a writer of notes and essays in contemporary history. Nobody invented or consciously proposed this development of the newspaper business. It has been brought about gradually by trial and error in the course of a generation.

I think that the turning point was the Great Depression of 1929 and the revolutions and the wars which followed it. Long before 1929 there were, of course, signed articles, essays, criticisms, columns of comment in prose and in verse, and expressions of personal opinion. But the modern Washington correspondent — which includes the news analyst and the columnist — is a product of the world-wide Depression, of the social upheaval which followed it, and of the imminence of war during the 1930s

The unending series of emergencies and crises which followed the economic collapse of 1929 and the wars of our generation have given to what goes on in Washington and in foreign lands an urgent importance. After 1929, the federal government assumed a role in the life of every American and in the destiny of the world which was radically new. The American people were not prepared for this role. The kind of journalism we practice today was born out of the needs of our age — out of the need of our people to make momentous decisions about war and peace, decisions about the world-wide revolutions among the backward peoples, decisions about the consequences of the technological transformation of our own way of life in this country. The generation to which I belong has had to find its way through an uncharted wilderness. There was no book written before 1930, nor has any been written since then, which is a full guide to the world we write about. We have all had to be explorers of a world that was unknown to us and of mighty events which were unforeseen.

The first presidential press conferences I attended were during the Administration of Woodrow Wilson before this country became involved in World War I. These press conferences were so small that they were held in the President’s office, with the correspondents standing about three or four deep around his desk. When the conference ended, the President would sit back in his chair, and those who wanted to do so would stay on a bit, asking him to clear up or amplify this or that piece of news.

The little group that stayed on consisted of those who were concerned not with the raw news of announcements and statements in the formal press conference but with explaining and interpreting the news. They were the forerunners of the Washington correspondent today. For, these correspondents and their editors in the home offices were coming to realize that raw news, as such, except when it has some direct and concrete personal or local significance, is to the newspaper readers, for the most part, indigestible and unintelligible.

It goes without saying that, in a democracy like ours, it is an awful responsibility to undertake the processing of the raw news so as to make it intelligible and to reveal its significance, It is such a great responsibility, it lends itself so easily to all manner of shenanigans that, when I can bear to think about it, I console myself with the thought that we are only the first generation of newspapermen who have been assigned the job of informing a mass audience about a world that is in a period of such great, of such deep, of such rapid, and of such unprecedented change.

THE newspaper correspondents of this generation have learned from experience that the old rule of thumb about reporters and editorial writers, about news and comment, oversimplifies the nature of the newspaperman’s work in the modern world. The old rule is that reporters collect the news, which consists of facts, and that the editorial page then utters opinions approving or disapproving of these facts.

Before I criticize this rule, I must pay tribute to its enduring importance. It contains what we may call the Bill of Rights of the working newspaperman. It encourages not only the energetic reporting of facts but also the honest search for the truth to which these facts belong. It imposes restraints upon owners and editors. It authorizes resistance — indeed, in honor it calls for resistance — to the contamination of the news by special prejudices and by special interests. It proclaims the corporate opposition of our whole profession to the prostitution of the press by political parties, by political, economic, and ideological pressure groups, by social climbers, and by adventurers on the make.

But, while the rule is an indispensable rallying point for maintaining the integrity of the press, the practical application of the rule cannot be carried out in a wooden and literal way. The distinction between reporting and interpreting has to be redefined if it is to fit the conditions of the modern age.

It is all very well to say that a reporter collects the news and that the news consists of facts. The truth is that, in our world, the facts are infinitely many and that no reporter could collect them all, no newspaper could print them all, and nobody could read them all. We have to select some facts rather than others, and in doing that we are using not only our legs but our selective judgment of what is interesting or important, or both.

What is more, the relevant facts often exist far away and out of sight of any newspaperman — as does the condition of the military balance of power in the world today. You cannot go and look at the balance of power: you have to deduce it and calculate and appraise it. The relevant facts may occur in places that the reporter cannot visit — Red China — and then the facts have to be inferred and imagined from secondhand reports. The facts may lie in the past. Then they have to be recovered and reconstructed — as in the story of how we got into our predicament in Berlin. The facts may lie inside the head of a public man, which, like Mr. Khrushchev’s head, is not open to private inspection. The facts may lie in the moving tides of mass opinion — for example, facts about the coming elections — which are not easy to identify and to measure.

Under these conditions, reporting is no longer what we thought it was in much simpler days. If we tried to print only the facts of what had happened — who did what and who said what — the news items would be like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle thrown in a heap upon the table. The unarranged pieces of raw news would not make a picture at all, and fitting them together so that they do make a picture is the inescapable job of a Washington correspondent.

However, very quickly the analogy of the jigsaw puzzle breaks down. Indeed, like most analogies, it is rather dangerous. Our job is harder than it appears. In real life there is not, as there is in every jigsaw puzzle, one picture and one picture only, into which all the pieces will eventually fit. It is the totalitarian mind which thinks that there is one and only one picture. All the various brands of totalitarianism, as violently as they differ among themselves, have this in common. Each holds that it has the key and pattern of history, that it knows the scheme of things, and that all that happens is foreseen and explained in its doctrine.

But, to the liberal mind, this claim — like any other human claim to omniscience — is presumptuous and it is false. Nobody knows that much. The future is not predetermined in any book that any man has written. The future is what man will make it; and about the present, in which the future is being prepared, we know something, but not everything, and not nearly enough.

Because we are newspapermen in the American liberal tradition, the way we interpret the news is not by fitting the facts to a dogma. It is by proposing theories or hypotheses, which are then tested by trial and error. We put forward the most plausible interpretation we can think of, the most plausible picture into which the raw news fits, and then we wait to see whether the later news fits into the interpretation. We do well if, with only a minor change of the interpreta tion, the later news fits into it. If the later events do not fit, if the later news knocks down the earlier story, there are two things to be done. One is to scrap the theory and the interpretation, which is what liberal, honest men do. The other is to distort or suppress the unmanageable piece of news.

Last summer, while walking in the woods and on the mountains near where I live, I found myself daydreaming about how I would answer, about how I would explain and justify the business of being opinionated and of airing opinions regularly several times a week.

“Is it not absurd,“ I heard critics saying, “that anyone should think he knows enough to write so much about so many things? You write about foreign policy. Do you see the cables which pour into the State Department every day from all parts of the world? Do you attend the staff meetings of the Secretary of State and his advisers? Are you a member of the National Security Council? And what about all those other countries which you write about? Do you have the run of 10 Downing Street, and how do you listen in on the deliberations of the Presidium in the Kremlin? Why don’t you admit that you are an outsider and that you are, therefore, by definition, an ignoramus?

“ How, then, do you presume to interpret, much less criticize and to disagree with, the policy of your own government or any other government?

“And, in internal affairs, are you really much better qualified to pontificate? No doubt there are fewer secrets here, and almost all politicians can be talked to. They can be asked the most embarrassing questions. And they will answer with varying degrees of candor and of guile. But, if there are not so many secrets, you must admit that there are many mysteries. The greatest of all the mysteries is what the voters think, feel, and want today, what they will think and feel and want on election day, and what they can be induced to think and feel and want by argument, by exhortation, by threats and promises, and by the arts of manipulation and leadership.”

Yet, formidable as it is, in my daydream I have no trouble getting the better of this criticism. “And you, my dear fellow,” I tell the critic, “you be careful. If you go on, you will be showing how ridiculous it is that we live in a republic under a democratic system and that anyone should be allowed to vote. You will be denouncing the principle of democracy itself, which asserts that the out siders shall be sovereign over the insiders. For you will be showing that the people, since they are ignoramuses, because they are outsiders, are therefore incapable of governing themselves.

“ What is more, you will be proving that not even the insiders are qualified to govern them intelligently. For there are very few men — perhaps forty at a maximum — who read, or at least are eligible to read, all the cables that pour into the State Department. And then, when you think about it, how many sena tors, representatives, governors, and mayors — all of whom have very strong opinions about who should conduct our affairs — ever read these cables which you are talking about?

“Do you realize that, about most of the affairs of the world, we are all out siders and ignoramuses, even the insiders who are at the seat of the govern ment? The Secretary of State is allowed to read every American document he is interested in. But how many of them does he read? Even if he reads the Ameri can documents, he cannot read the British and the Canadian, the French and the German, the Chinese and the Russian. Yet he has to make decisions in which the stakes may well be peace or war. And about these decisions, the Congress, which reads very few documents, has to make decisions too.”

Thus, in my daydream, I reduce the needier to a condition of sufficient hu mility about the universal ignorance of mankind. Then I tum upon him and with suitable eloquence declaim an apology for the existence of the Washington correspondent.

“If the country is to be governed with the consent of the governed, then the governed must arrive at opinions about what their governors want them to con sent to. How do they do this?

“They do it by hearing on the radio and reading in the newspapers what the corps of correspondents tell them is going on in Washington, and in the country at large, and in the world. Here, we correspondents perform an essential ser vice. In some field of interest, we make it our business to find out what is going on under the surface and beyond the horizon, to infer, to deduce, to imagine, and to guess what is going on inside, what this meant yesterday, and what it could mean tomorrow.

“ In this we do what every sovereign citizen is supposed to do but has not the time or the interest to do for himself. This is our job. It is no mean calling. We have a right to be proud of it and to be glad that it is our work.”

Social Revolutionaries

A few weeks ago I reproduced Justin Murphy’s introduction to Julien Benda’s 1927 The Treason of the Intellectuals. In this passage we see that new man at his birth. From Revolutionary Spring.

The July Revolution of 1830 marked the spectacular triumph of the juste milieu politics of the most moderate liberals, but it also inaugurated a new form of political opposition centred on a growing republican movement. This was in some ways a surprising development, because the term republic, recalling the First French Republic of 1792–1804, was still strongly associated in French memory with state terrorism and continental war; after 1815, enthusiasm for it had survived mainly underground in fragile and exiguous secret associations and networks.[35] It was the July Revolution that breathed new life into the republican idea. Founded on 30 July 1830, the republican ‘Society of the Friends of the People’ was led by activists who had played a key role in the insurrection. The scientist and public health reformer François-Vincent Raspail, a pioneer of the cell theory in biology, had been wounded attacking the barracks of Sèvre-Babylone; the revolutionary socialist Louis-Auguste Blanqui had been among those who stormed the Palais de Justice; Godefroy Cavaignac, the son of a regicide Montagnard (left-wing) member of the convention of 1793 who had fled France at the Bourbon Restoration, had helped to plant the tricolour flag on top of the Louvre. Although the number of members was modest (perhaps 300), the Society also ran a journal; its meetings in the rue Montmartre usually attracted between 1,200 and 1,500 interested fellow travellers; the print-runs of its brochures could be as high as 8,000. Carbonari, freemasons, neo-Jacobins and Saint-Simonians gravitated towards the Society, gathering and exchanging ideas. This was not a proletarian milieu: the second-wave republicans were medics, merchants, students and literary people. Their horizons were international and cosmopolitan. The Society mounted protests in support of the Polish struggle against Russia and helped to find lodgings for Polish refugees, some of whom became members. ‘To support the emancipation of peoples against the efforts of tyrants’, a Society manifesto of October 1831 declared, ‘is a sacred duty for a free nation.’[36]

The republican opposition was not unanimously committed to direct action against the Orleanist regime. As republicanism grew, it acquired a broad palette of political flavours ranging from moderate and liberal groups to the socialist left. Some left-republicans favoured mounting an armed assault on the authorities, but there were socialist republicans who, like Louis Blanc, renounced conspiracy and violence. Nevertheless, the clashes between the government and the hard core of its most implacable enemies had a spectacular quality that impressed itself upon public awareness. Three insurrections that shook Paris during the 1830s revealed both the structural weakness and the increasing radicalism of the far left.

On 5 June 1832, at the Parisian funeral of a popular general, a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars known for his ties with the political opposition, clashes with the police flared into an insurrection that quickly spread from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to the central district near the rues Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin. The insurgents broke into gun shops, disarmed guard posts and constructed barricades across the narrow streets of the medieval heart of the city. In less than two hours, the Prefect of Police later recalled, they seized 4,000 rifles and other munitions and occupied nearly half of the city.[37] The army, the National Guard and the Municipal Guard were called in until the point was reached where the government’s forces numbered nearly 60,000 men. Fighting went on all night, the city echoing with the thud of artillery barrages. About twenty-four hours after the uprising had begun, the last barricades were shelled to fine rubble and the streets fell silent. The insurgents had suffered around 800 casualties in dead and wounded.[38] This was the historical episode that would inspire the climactic barricade scenes in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Two days later, when Heinrich Heine visited the morgue where the bodies of the killed had been taken to be identified by friends and relatives, he found people forming long queues, as if they were waiting outside the Opéra to see Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable.

The government mounted vigorous attacks on the Society of the Friends of the People, fining and arresting key members, shutting down the meetings in the rue Montmartre and prosecuting the leaders for breaches of the Law on Associations. The trial that followed the insurrection of 1832 shed light on a left-republican milieu in which the relatively mellow, bourgeois figures of 1830 were already making way for (mainly skilled) workers with a preference for direct action. When the Society of Friends of the People collapsed in the aftermath of the unrest, a new association, known as the Society of the Rights of Man and the Citizen took its place as the leading republican formation.

It was the efforts of the government to crush this network that triggered a further insurrection in April 1834. Protests had erupted in the streets of Paris in response to new laws limiting the freedom of association and expression. Excited by reports of the second weavers’ insurrection in Lyons, and confident that they enjoyed the support of progressive elements of the population, the Society of the Rights of Man launched an uprising in the capital. This was a different kind of venture: not spontaneous in the manner of 1830 or 1832, but planned in advance. Barricades went up across the Right Bank between the rue Saint-Martin and the rue du Temple and around the Sorbonne on the Left Bank of the river. This time, the police response was swifter and better organized. By evening, the insurgent groups around the Sorbonne had been dispersed. At dawn on the following day, the National and Municipal Guard closed in on the barricaded areas of the Right Bank, engaging the insurgents in the streets and flushing them out of residential buildings, a process attended by at least two sprees of indiscriminate killing.

On the rue Transnonain in the Saint-Martin area, members of the 35th Battalion of the National Guard entered a building believed to be the source of shots that had killed an officer and the troops gunned down or bayonetted a dozen occupants over several floors. The artist Honoré Daumier memorialized this event, which occurred just three blocks from his home, in a monumental lithograph. Entitled Rue Transnonain, le 15 avril 1834, it depicts a working-class family massacred during the raid. This was not an action scene; Daumier chose to depict the moment of eerie calm after the violence; terror exists only in the traces it has left, in dishevelled corpses, murky bloodstains and an overturned chair. It is the viewer who must reconstruct in her own mind the horrors that have just transpired.

When the leaders of this group disappeared in their turn into jail and the movement went underground, a new and yet more radical body emerged, the Society of Seasons, led by three men of the hard left: Louis-Auguste Blanqui, Armand Barbès and Martin Bernard. The emphasis was now less on the removal of monarchy, which was taken for granted, and more on an all-encompassing agenda of revolutionary social transformation, to be achieved through collaboration with cadres of armed worker activists.[39] The insurrection they launched on Sunday, 12 May 1839, went wrong from the start. Around 400 activists attacked gunshops, confiscating weapons, taking control of guard posts and attacking the prefecture of police. Driven away by troops and National and Municipal Guardsmen, who were quick to move to the centre of the insurgent-controlled area, they broke up and barricaded themselves into several streets on the Right Bank. There were short, savage bursts of violence as insurgents and security forces fought it out in various locations with a range of weapons, including swords and axes. By eleven in the evening, the barricades had been reduced and the insurgents killed, arrested or dispersed. The casualties were much lower than in 1832: there were twenty-eight deaths among the soldiers and guards, and sixty-six civilians were killed, of whom twenty-seven were bystanders – among them was the eighteen-year-old shawlmaker Minette Wolff, who was killed by a stray bullet as she rushed to get inside her house.[40]

Tellingly, the chief counsel for the prosecution of a number of the accused was none other than Joseph Mérilhou. This fascinating figure had been a high-ranking member of the French Carbonari, a brilliant defender of prosecuted journals under Charles X and the foremost legal adviser to the liberal insurgents of the Glorious Days of July 1830. Now the scourge of the Bourbons had become a pillar of the July establishment. ‘As you can see’, Mérilhou told the court, ‘it’s not simply a political revolution [the plotters] have in view, it’s a social revolution; it’s property that they want to revise, modify and transfer.’[41] Far from representing a progressive vision, Mérilhou insisted, the politics of the conspiracy was a journey back into the year 1793, the year of the Jacobin dictatorship and the Great Terror. In this way, Mérilhou ousted the far left from the progressive historicity of the moderate liberals.[42]

The activists of the Society of the Seasons had increasingly isolated themselves from the rest of French political society, which, for the most part, viewed such schemes with horror. The secretive inner structure of the Society also helped to cut the movement off from the popular classes.[43] But the insurrectionist republicans remained connected with the European exile networks. The transmission of leftist ideas in a range of variations can be tracked across the activist diaspora.[44] Heinrich Heine was struck by the sight of the national flags of the German, Italian and Polish exile communities alongside the French tricolour.[45] Among the insurgents killed during the 1839 insurrection was an exiled Italian hatter by the name of Ferrari, and the captive insurgents who later stood trial included a certain Florentz-Rudolph-Augustus Austen, known as ‘Austen le Polonais’, a 23-year-old Polish bootmaker from the city of Danzig who had fought in the November Uprising of 1831. Austen, whose only previous indictment in France was on a charge of beggary, claimed under interrogation to have been ‘forced’ to help the insurrectionaries. When it was pointed out to him in court that his numerous injuries, including bullet, sword and bayonet wounds, demonstrated beyond doubt that he had been involved in the fighting, he replied that he had been ‘forced under repeated blows to accept cartridges’. The court did not believe him, and he wound up in the same dank French prison as the insurgent leaders, Louis Auguste Blanqui, Armand Barbès and Martin Bernard.

Joseph Mérilhou was right to point up the social isolation of these militants of the left. In a sense, their insistence on conspiracy was born precisely of the insight that they lacked the means to raise the masses against the prevailing order. Captured documents revealed that they anticipated installing a ‘dictatorial power’ invested in the ‘smallest possible number of men’ whose task would be to ‘direct the revolutionary movement’, excite the masses to enthusiasm and ‘suppress those of its enemies whom the whirlwind of popular indignation had not already devoured in the heat of combat’.[46] This dictatorship would be legitimated by the fact that it was wielded not in the name of the exploiters of commerce, industry and agriculture, but of those proletarians who possessed nothing but the strength of their arms.[47]

How these activists embodied and performed the idea of revolutionary commitment was as significant as the content of their ideas. Rather than attempting to evade punishment, ‘like vulgar culprits who must blush at their acts and intentions’, the accused insurgents resolved to choose defenders who shared their political views – deputies, lawyers, journalists or men of letters – regardless of whether they were listed on the roll of advocates (tableau des avocats). The aim was to use the court not to evade punishment, but as a means of ‘glorifying their cause and doctrines’.[48] When he stood trial for his part in the insurrection of 1832, Louis-Auguste Blanqui refused to play the role assigned to him by the court: ‘I am not standing before judges, but in the presence of enemies. As a result, there would be no point in defending myself.’[49] A number of the leading insurgents of 1839 refused to answer questions, both in police custody and before the Court of Peers. When asked why he persisted in remaining silent, Armand Barbès replied: ‘Because between us and you there can be no true justice. I do not wish to play a role in the drama which is going to unfold here. You are the men of royalty and I am a soldier in the cause of equality…. There are only questions of force.’[50] It is the ontological radicalism of this response that is striking: in answering thus, Barbès collapsed the normative claim and the procedural grandeur of the Court into an expression of mere violence by the regime of ‘the exploiters’. For the moment, this understanding of political order as the raw interplay of force was a speciality of the left; only after the revolutions of 1848 would it infiltrate liberal and conservative discourses.

In defying the political and ethical norms of ‘bourgeois’ society, the activists of the left invented a new kind of political self. We can see this more clearly if we compare two prison narratives of the era. What struck readers about Silvio Pellico’s memoir, Le mie prigioni (1832), which became a classic (see chapter 2) and is still read by Italian children in high school today, was the modesty, simplicity and homiletic intensity of the writing. Nowhere did Pellico express anger or vengefulness towards those who had ensnared, betrayed, interrogated or punished him. The book focused on the writer’s often labile and exalted emotional state – the sorrowful paternal love he felt for a deaf-mute waif raised by warders; his tearful happiness when he saw the handkerchief of another imprisoned patriot waving from a cell window; the anguished reflections on family and friends; the letter he wrote to a comrade in another cell using a small shard of glass wetted in his own blood; the desperate reaching towards the presence of God in the darkness and solitude of his cell; the cruelties and suffocating tedium of prison routine.[51] Politics, on the other hand, was completely evacuated from the narrative.[52] And this was essential to the book’s success. If the book had simply been ‘an ordinary invective against Austrian oppression, conceived and executed in the usual perfervid manner of Italian partisanship’, a reviewer for the Foreign Quarterly Review observed, ‘it would have been forgotten in a fortnight’; Pellico’s ‘calm, classical and moving picture of suffering insinuates itself irresistibly into the heart and will long maintain its hold on the memory’.[53]

In the prison memoir he completed in 1851, Martin Bernard, one of the three leaders of the insurrection of 12 May 1839, adopted a different approach. Born in 1808 and thus nineteen years Pellico’s junior, Bernard, the younger son of a printer in Montbrison, central France, traced an emblematic journey across the early-nineteenth-century political spectrum. As an adolescent he longed to fight for Greece; in the later 1820s he devoured the journals, brochures and pamphlets of the liberal opposition. The 1830 revolution marked a turning point: he missed the action and elation of the Glorious Days, but when he returned to Paris in the following year, he was horrified at how the ‘principles of the revolution’ were being ‘betrayed’. A cohort of ‘shameless mountebanks’ (éhontés bateleurs) had taken control of the country and were exploiting the victory. The liberals remained ‘obsessed with the suffrage, the sovereignty of the people’. Bernard’s thoughts, by contrast, turned towards ‘critique of the social organisation’.[54] His quest for a theoretical foundation on which to develop his social critique led him first to the Saint-Simonians, then to Charles Fourier, and eventually back to Robespierre and the pursuit of ‘democratic and social fraternity which was the goal of our fathers and will be the conquest of our century’.[55]

For his role in the insurrection of May 1839, Bernard would remain incarcerated in the fortress at Mont Saint-Michel, nearly a mile off the coast of Normandy, until his unexpected liberation at the outbreak of revolution in 1848. The challenges he faced in the dungeons there – boredom, isolation, cold, damp, foul air, untreated illnesses – were those that Pellico had known. But the emotional texture of his memoir could hardly have been more different.[56] For the ‘touching elegy’ and the soft, plangent masculinity that had animated the Italian’s memoirs, Bernard substituted a posture of haughty, unbending defiance. Cautioned by the director of the prison that any infraction of the code of silence would result in solitary confinement in a tiny cell remote from the other prisoners, Bernard warned him: ‘Be on your guard, sir…. The time will come…when you will be asked to give an account of how you applied these orders.’[57] Whereas Pellico was always seeking out the humanity of his warders, Bernard treated them as the nerveless tools of a regime of power, neither good nor evil in themselves, small human wheels in a large repressive apparatus.

These differences, Bernard believed, derived from the divergent ideological stances of the two men. Pellico and his fellow Italian patriots had been imprisoned for indulging ‘vague, wishful fantasies of national independence and liberalism, the flickering light of eternal rights’. Bernard and his fellow insurgents, by contrast, had been ‘retempered in the faith of the immortal vanquished of Thermidor [i.e. of Robespierre and the Jacobins]’. They had acted in the name of an ‘idea that must regenerate the world’. It was only natural that Pellico should respond to setbacks with wistful resignation and Bernard with an implacable ‘disdain’ – one of the key words of his narrative. But this was not the haughty disdain of an eighteenth-century nobleman – it was a posture of self-mastery that sprang directly from his faith in the ‘sacred doctrine of equality’, a doctrine whose triumph was both inevitable and imminent.[58] By the later 1840s, this temperamental difference was coming to be seen as the behavioural marker of a new form of leftist politics: the enthusiastic and demonstrative politics of the old-school exaltado, one German newspaper noted in January 1848, was much less dangerous than the ‘cold and tranquil’ communist who proceeded directly towards his objective.

Not everyone at Mont Saint-Michel was tough enough to live up to Bernard’s ideal of stoical revolutionary masculinity. The younger men among the prisoners of 1839 chafed at the constraints of prison routine. Noël Martin, who was not yet twenty, broke the rules by shouting to the other prisoners and then resisted his guards as they led him to be chained and manacled. In the ensuing fracas he was stabbed, then kicked and beaten and thrown into solitary confinement, chained and covered in blood and bruises. It had always been difficult to communicate with the Polish radical known as ‘Austen’ because he spoke a curious Franco-Polish patois, a trait that had amused his judges in Paris. Austen had not observed the code of silence before the Court of Peers, trying instead to talk himself out of trouble with implausible excuses. Once in prison, he fell into a ‘strange mutism’, breaking his silence only to complain of imaginary things. Only after he wounded himself with a knife in his cell did the prison authorities concede that he might be mentally ill. ‘Austen le Polonais’ was transferred to solitary confinement and eventually moved to the asylum at Pontorson. The news shocked the radical prisoners more than his death would have done, Bernard recalled, because they all remembered:

the noble nature of this child of Poland, his tall and slender stature with the long blonde hair, the pale and dreamy countenance with the straight and regular lines; the blue eyes at one moment suffused with melancholy, at another with a singular martial ardour. We remembered his heroism on the barricade at Grenétat, where he fell pierced with twenty bayonet blows…

THE CULT OF CLANDESTINITY …