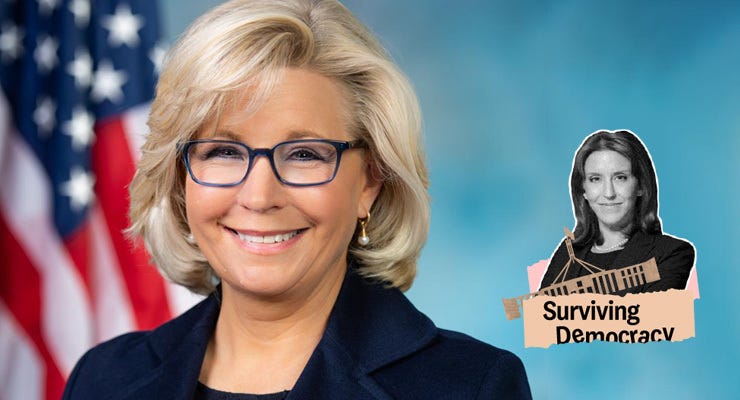

Liz Cheney: in deep gratitude

Like me, Leslie Cannold is deeply grateful for Liz Chaney right now — you know, the way she’s speaking truth to fruitcakery.

Liz Cheney is my hero. On positions of policy, I disagree with her almost 100% of the time, but I see her as one of the first moral heroes of this millennia. A highly principled woman willing and able to set aside every one of her personal interests to do what’s right for her country.

She contrasts this with Democrat sympathisers who claim to see through Cheney’s apparently principled stand — those whose arguments amount to the assertion that “Cheney’s stance has nothing to do with principle, but rather vengeance [against Trump] served cold”.

However being asked to choose between light and dark seems a bit stark to me. Having observed politics from nearer and further for quite a few decades now, I’d never assume anyone had 100% pure motives. Ted Cruz stood up for principle — the principle of not lying every time you open your mouth in politics. Why? Because he was opposing Donald Trump who couldn’t open his mouth without lying. But Ted came to Jesus and it turned out he wasn’t a person of principle any more.

My operating assumption is that Liz Cheney has got herself into a situation in which Trump is an enemy and, having made her bed, she’s lying in it. That’s not me saying that all politicians are ‘cynical’. Rather the opposite. It’s saying that politics is a profession in which one is endlessly trading off ends and means, endlessly trying to promote one’s own career and do something worthwhile. And in that world, a great deal of the time the ends justify the means. And the art of politics is ultimately understanding where the ends don’t justify the means.

In all the democratic cultures I know, people tend to chat about politics as if it’s pretty clear who’s a goodie and who’s a baddie. They criticise those politicians they don’t like as if all politicians should be candid and strictly principled in all they say and do. Then of course when those on their own side do the same, they immediately make excuses — of course they have to cut corners given how ruthless their opponents are etc etc.

By this means almost everyone’s political chit-chat participates in a kind of moral panto. It’s one of the many ways in which political culture gets engulfed in wishful thinking. Indeed, as I’ve said before, I think we need a whole new ‘alt-political discourse’ to rise above the moral panto of wishful thinking into which the current political discourse has descended.

I don’t want to get too high on my horse about Cannold here as short pieces must compress what is said, but it really did stick in my craw to be told that her analysis was that of “an ethicist”. If that’s what ethicists have to tell us — that we have to choose between naivete and everyone’s-in-it-for-themselves-cynicism — then so much the worse for ethicism. I prefer ethics which is all about that land bounded by the two extremes of panto. It’s all about how we try to feel good about our own conduct in a murky world — a world in which vice always comes disguised as virtue.

Still, Liz Cheney got into politics to trade off ends and means and then got herself into the situation she's in, and she's digging in and fighting. She's fighting for us all. That's good enough for hero status for me.

Chris Joye is alarmed at rate rises

I’ve been unimpressed by the RBA’s management of monetary policy for some time now. As I wrote in 2015:

Early in 2013 it forecast unemployment “to drift gradually higher” over the next few years. The treasury was predicting something similar. Yet the cash rate was kept steady at 3.0% for February, March and April, and then cut by just 0.25% in May 2013.

Cutting rates late and reluctantly describes the RBA all the way to the pandemic. It’s OK to be worried about asset prices — as they were. But then I’d like to have seen their models. And in particular I’d like to have seen some consideration that cutting reluctantly and late gave the markets a one way bet. More aggressive cutting brings forward the day rates are on the upswing again, which should restrain asset prices. Anyway, there was none of this. Instead there was “on-the-one-hand and then on-the-other-handing” flying by the seat of the pants while they ditched the economic textbook targeting something way short of full employment.

Now it’s time to tap on the brakes, the problem is that with all the debt we’ve acquired we don’t know much about the effect it will have. Chris Joye is a bright guy who knows a lot about the market, and he’s not impressed. There’s a good chance he’s wrong, but I’m not sure there isn’t at least an equal chance that the Bank is wrong.

Martin Place crows about how many Australians are ahead on their mortgage repayments and have built up substantial buffers to protect themselves against rate increases.

“The data suggest that over one-third of variable-rate borrowers have already been making average monthly loan payments (including irregular payments to redraw and offset accounts) Bullock explained. … The scarier interpretation of the same chart is that 40 per cent of all borrowers will face a massive increase in their monthly mortgage repayments exceeding 30-40 per cent.

More behind the AFR’s paywall below, but Chris sent me his column which I reproduce at the bottom of this newsletter.

Financialisation of tech

Noah Smith has an excellent survey of wins and losses on the innovation front and is worried by the extent to which VC funds are going into trading, which as he points out “along with lending drove much of the finance industry’s expansion from 1980 to 2008”.

In recent years, trading has taken an increasingly prominent place in the fintech world. Platforms like Robinhood have onboarded a whole ecosystem of retail investors (that’s finance-ese for “regular folks”) into the markets. And cryptocurrency and web3 are hard at work creating new assets for people to trade, and new markets in which to trade them. Both fintech and crypto/web3 saw enormous, record inflows of VC funding in 2021. …

I am not an inveterate web3 skeptic or detractor (like, say, Liron Shapira). I believe that web3 creators will probably find useful applications for blockchains (unique online identities and DAOs are two ideas I think are promising, for example). But the vast majority of the web3 stuff that’s being created and envisioned right now seems to rely heavily on trading as part of its business model.

Tascha Che of Tascha Labs listed a bunch of hypothesized web3 applications. Essentially all of the ideas she lists — social media platforms, search engines, warehouses, etc. — are things that work perfectly well without blockchains.

Well mostly yes, but blockchain may well be needed to build social media on which users — not the platform — maintain the social graph and so retain the rent and the power — one of the ideas behind Urbit. But with that caveat I recommend the piece.

I don’t think I ever watched a full episode of Neighbours, but I liked this

Private goods become public: NYC edition

What’s wrong with liberalism

In 1826 the 20-year-old John Stuart Mill had a nervous breakdown. He had been raised by his father, James, as a utilitarian. Consequently, he had believed that all that mattered in life was pleasure and pain. Suddenly, nothing gave him pleasure anymore. Having been taught that his purpose in life was to spread happiness, he now realised, as he later reported in his Autobiography, that making other people happy would not bring about his own happiness. He emerged from this crisis when he realised that happiness is peculiar: it is a byproduct of doing something you care about, something you believe in. Paradoxically, he was now free to devote himself once more to making other people happy.

Waleed Ali: one of the few folks on our media who asks uncomfortable questions

Arthur Miller on New York in the heat — looking back

An atmospheric piece about a world that’s past from the great Arthur Miller.

In order to make as much money as possible, this fellow would start work at half past five in the morning and continue until midnight. He owned Bronx apartment houses and land in Florida and Jersey, and seemed half mad with greed. He had a powerful physique, a very straight spine, a tangle of hair, and a black shadow on his cheeks. He snorted like a horse as he pushed the cutting machine, following his patterns through some eighteen layers of winter-coat material. One late afternoon, he blinked his eyes hard against the burning sweat as he held down the material with his left hand and pressed the vertical, razor-sharp reciprocating blade with his right. …

Great read on the gravitational pull of grand theory

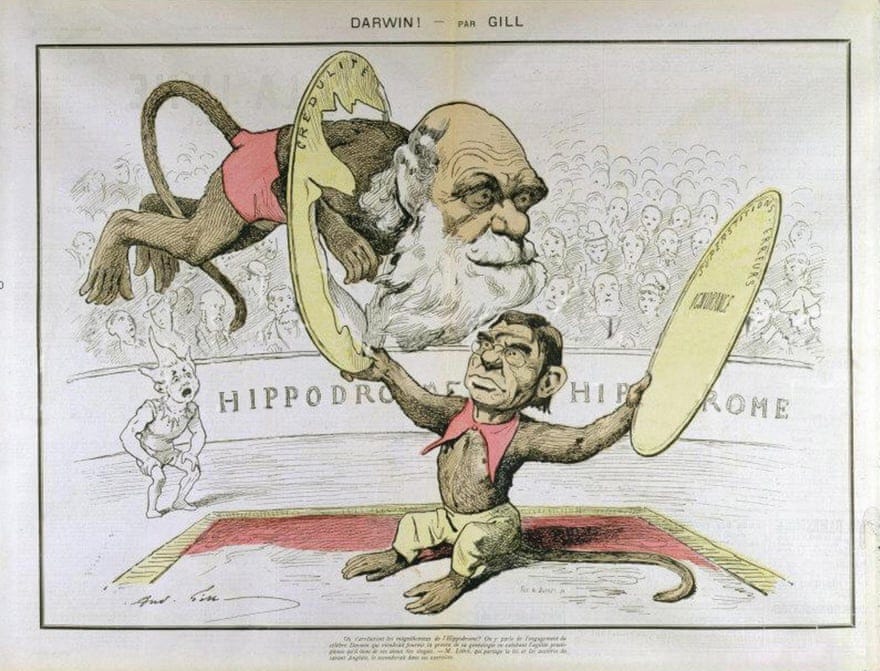

Excellent long piece which you can also listen to on the scourge of intellectual authoritarianism in evolutionary biology. I particularly enjoyed the focus on academics with something to say and the complete absence of the media savvy blowhards that dominate the field (Richard Dawkins, I’m looking at you.) The way evolutionary biology is arranged as a professional culture war always reminds me of neoclassical economics which is also riven by the gravitational hankering for a nice (super simple) theory of everything As I suggested here.

The modern synthesis arrived at just the right time. Beyond its explanatory power, there were two further reasons – more historical, or even sociological, than scientific – why it took off. First, the mathematical rigour of the synthesis was impressive, and not seen before in biology. As the historian Betty Smocovitis points out, it brought the field closer to “examplar sciences” such as physics. At the same time, writes Smocovitis, it promised to unify the life sciences at a moment when the “enlightenment project” of scientific unification was all the rage.

A tweet summarising where I’m at

Boris yelling at the indoor plant

When you get a mo — have a listen to this program about Boris’s time as a journo in Brussels. Go to about 9.30 and listen for a couple of minutes to the story of the 4.00 pm rant — completely extraordinary.

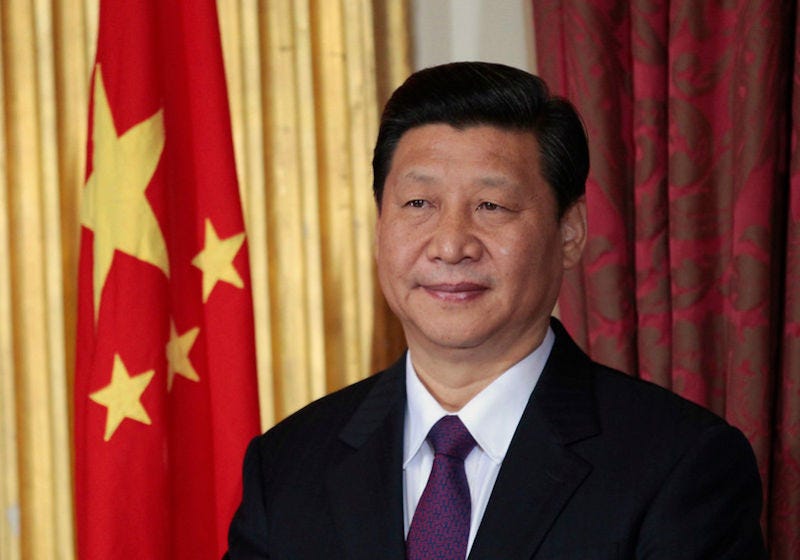

Bob Carr on three ways to improve relations with China

Seems pretty straightforward to me.

First, both sides should focus on trade. Canberra should propose trade missions to agree on lifting the barriers applied in 2020 to $20 billion in Australian exports. In return, we can review the anti-dumping actions we initiated against China. We can also say, like New Zealand, we won’t block China’s entry to the sprawling trade pact (the CPTPP) that has taken the place of the Trans-Pacific Partnership the US originally sponsored but now won’t join.

Second, we re-tool our rhetoric. Continue the current language criticising the mistreatment of Uighurs and the end of Hong Kong’s legal autonomy. These are the formulae used by all Western countries anyway. Likewise on the South China Sea. China should not expect anything else.

But continue to shun the primitive “drums of war” rhetoric of Peter Dutton and department head Mike Pezzullo. On the other hand, don’t apologise for excluding Huawei. Just say it was done for “the security and resilience of our network” not defining it, as Malcolm Turnbull did, as a pro-alliance gesture to impress the US.

Neither side should make diplomacy through headlines or get tripped-up by them.

Third, Australia should pursue creative middle-power diplomacy on Taiwan – as if our lives depended on it. Taiwan is not Ukraine. The west “acknowledges” China’s claim that Taiwan is a province of China, not an independent country. Ukraine, by contrast, is recognised as a sovereign state.

Asked about Taiwan, we can resort to good, all-weather diplomatic words. We can say we welcome the fact senior US security adviser Jake Sullivan and Chinese Communist Party Politburo Member Yang Jiechi have had hours of talks.

This US-China diplomacy is about peace and security. Among other things, it is laying down guard rails to avoid war over the Taiwan Strait. We can add that with all of Asia, Australia supports a return to a cross-strait status quo, like the one that preserved the peace for 60 years.

Interesting thread

Fruitcake watch …

The RBA’s intellectual paradox: Chris Joye: Jul 22

The great Aussie housing crash is accelerating, and it is being driven by the fastest and largest interest rate shock households have faced in modern history. Sydney house prices have now plunged almost 5 per cent since their peak only months ago according to CoreLogic. Home values in Melbourne are not far behind.

The value of residential property in Australia’s two largest capital cities is now declining at a very rapid pace exceeding one percentage point per month, which signals double-digit losses over the next year (consistent with our priors). There is further evidence that the Brisbane market is rolling over. Adelaide and Perth prices also look to be grinding to a halt.

If you draw a line through May 2022, when the Reserve Bank of Australia first lifted rates, you can observe a striking structural break in property prices: there was an almost immediate, and quite dramatic, impact on the value of bricks and mortar. After promising not to raise rates until 2024, Martin Place broke the back of the market with its decision in May and the threat of much more to come. It has not disappointed: in August the RBA will deliver an unprecedented third, back-to-back 50 basis point rate rise (and possibly more).

Yet if you read The Australian Financial Review’s John Kehoe account, or listen to the RBA, you would be forgiven for thinking there is nothing to see here. The RBA has allegedly “slapped down the pessimists who are concerned that its super-sized interest rate rises will crush the housing market and the economy”. Let me assure you, the RBA “ain’t slapped down nuthin”. And I deliver this message in a Connor McGregor-like lexicon.

According to the RBA’s new Deputy Governor, Michelle Bullock, “as a whole households are in a fairly good position”. “The sector as a whole has large liquidity buffers, most households have substantial equity in their housing assets, and lending standards in recent years have been more prudent and have built in larger buffers for interest rate increases.”.

Bullock explained that “many borrowers are already making repayments well above what is required” with a lot of the mortgage debt held by wealthy households. The RBA also draws comfort from the fact that “those on very low fixed-rate loans have some time to prepare themselves for higher interest rates”.

I would have rephrased that as the droves of unwitting borrowers who were dudded by the RBA’s public commitment to not hike rates until 2024 (at the earliest) are now on notice that their mortgage repayments will more than double in the next year or two care of what will shortly be at least 175 basis points worth of interest rate increases in just three months.

In 2020 and 2021, the RBA relentlessly advised families and businesses to go out and borrow as much as possible on the basis of a commitment to not raise rates for years, only to first renege on that promise in 2022 and then embark on a crazy-aggressive tightening cycle that is now destroying the value of their single most valuable asset (and much more).

The RBA counters they never “promised” to not raise rates. They certainly “committed” not to increase them and made that a promise by explicating fixing the interest rate on the 2024 government bond at the same 0.1 per cent level as their overnight cash rate. And they spent billions defending the promise—until they suddenly did not in October 2021.

The RBA’s confidence in the strength of the household sector’s ability to withstanding the current interest rate shock sounds too good to be true. It is, in fact, a classic ex post facto rationalisation of a decision they have made to impose super-sized rate increases on the economy on the basis of forecasts that are not worth the paper they are written on. (Even the RBA concedes it cannot forecast its next footstep, which Governor Lowe has described as “embarrassing”.)

The RBA always rolls out these “narratives” to justify decisions it has made. And they are always faithfully recycled by the media, which can become beholden to the RBA for informational access.

There was one chart in the Deputy Governor’s recent speech that really betrayed the vulnerabilities in the RBA’s mental model. Martin Place crows about how many Australians are ahead on their mortgage repayments and have built up substantial buffers to protect themselves against rate increases.

“The data suggest that over one-third of variable-rate borrowers have already been making average monthly loan payments (including irregular payments to redraw and offset accounts) sufficient to meet [a 3 percentage point increase] in required repayments”, Bullock explained. “In other words, there is limited impact on these borrowers.”

The scarier interpretation of the same chart is that 40 per cent of all borrowers will face a massive increase in their monthly mortgage repayments exceeding 30-40 per cent. You get a similar sense of this fragility in other data.

Westpac recently disclosed that while 29 per cent of all their borrowers are at least one year ahead of their required repayments, a staggering 50 per cent are less than one month ahead. It is a classic bimodal distribution between haves and have nots.

CBA’s economists show that once you account for repayments of both interest and principal, lifting the RBA’s cash rate to 2.5 per cent would put household debt servicing costs back around 2008 levels when the cash rate was 7.25 per cent (and official mortgage rates were north of 9 per cent).

This potentially makes a mockery of the RBA’s claim that a 2.5 per cent cash rate would be around the “neutral” level that is neither contractionary nor expansionary for growth.

Since it does not fit the narrative, the RBA is for the time being ignoring data showing that consumer confidence in Australia has plummeted to levels last observed during the March 2020 pandemic shock and the GFC. The concern should be that consumer spending, which is one of the most important sources of growth, is highly correlated with confidence.

Unsurprisingly, CBA’s data does indeed indicate that household spending is now rolling-over despite the current high inflation which would normally boost the dollar value of spending over time. There are also some early signs that businesses are feeling the pinch with NAB’s measure of business confidence dropping sharply from recent peaks.

Finally, there is CBA’s wage data, which like the official wage price index, suggests labour cost growth remains modest at around 2.5 per cent annually. CBA’s information tracks actual wages paid into 300,000 bank accounts.

The RBA has claimed that for Australia to sustain inflation within its 2-3 per cent target band, it requires wage growth of 3-4 per cent annually. Despite there being no clear evidence that the Aussie economy is meeting this test, the RBA is blindly lifting rates like an inflation nutter.

The discombobulation characterising the RBA is manifest everywhere. There was the error in the RBA’s statement after its last board meeting when the central bank incorrectly alleged it was removing cash rate cuts that it had put in place following the pandemic—even though the cash rate was already above its pre-pandemic level of 0.75 per cent.

Today’s 1.35 per cent cash rate is now above its June 2019 level (nine months before the pandemic). Yet Deputy Governor Bullock maintains the RBA is only unwinding stimulus it had put in place post the pandemic.

“The point is, like every other country, we're coming off emergency or extraordinarily low interest rates in this country,” Bullock said. “Much, much lower than you would have in a normal, strong economy. And so at least the first task is to try and eliminate some of that monetary stimulus, so that's what we're trying to do.”

The issue with this logic is that the RBA’s current cash rate is almost double its pre-pandemic level. Following the minimum expected 50 basis point increase in August, the RBA’s new 1.75 per cent cash rate will be the highest it has been since July 2016.

Asked about this topic again during the week, Bullock responded, “We're at, as I've said, extraordinarily low interest rates, and we've got to get it up to some sort of concept of what you might call the 'neutral interest rate', which means it's neither expansionary nor contractionary.”

The RBA’s intellectual contradiction was nested in this subsequent statement: “We don't know where that particularly is, but we know it's a fair bit higher than where we currently are.”

How can the RBA not know where the neutral rate is, but in the same breath express confidence that it is a “fair bit higher” than the current 1.35 per cent rate?

The RBA seems to have lost sight of the impact of the quantum of debt in the economy. While interest repayments as a share of disposable household incomes might appear low, principal repayments are at their highest levels ever. And borrowers pay both.

You cannot examine one in isolation from the other. We therefore care about total debt servicing costs. Based on CBA’s data, the current cash rate puts total household debt repayments as a share of incomes at levels that are now higher than normal. This probably explains why many banks, including CBA and Westpac, believe that the RBA’s “neutral” cash rate could be as low as circa 1.5 per cent.

Thanks for the pointer to Buranyi on evolutionary biology and whether there's a need for an "extended evolutionary synthesis". Indeed, it's a fair overview -- describes honestly the positions of different participants.

But what on earth induced you to call Dawkins a "media savvy blowhard"? No such thing -- he's a really significant scientist. Probably the two most important extensions since the "modern synthesis" of the 1930s are both down to Dawkins. (Gene's eye view, and extended phenotype.)

Since Dawkins had the temerity to write some home truths about religion, there's been a sustained campaign to paint him as somehow a nasty personality. A common strategy, when you can't argue with the substance. Don't be misled by that.

(And for what it's worth, I'm on the side of what Buranyi calls the traditionalists. The complications cited by the wannabe revolutionaries are mostly not new, are not excluded by the modern synthesis, and are just complications or elaborations you would go into depending how important they were in particular situations. For example developmental plasticity -- it's just nonsense to say this doesn't get a mention in undergrad level teaching.)