A bit of energy anyone?

Bill Kelty is not a happy camper. Is he asking for too much? I don’t think so — he just wants a bit of energy from the Government. From the recent profile of his complaints in the Saturday Paper.

Let’s begin with housing affordability – a crisis decades in the making, and which most economists and both major parties agree threatens to estrange younger generations. In fact, the estrangement has already begun. Kelty is infuriated that this government, like previous ones, has preferred superficial changes on the demand-side of housing – various subsidies and, more recently, the consensus that immigration rates are problematic – than confronting the issue of supply.

“You’ve had a shortage of labour,” Kelty says, “and the traineeship system in this country is fucked. You’ve got a tax policy which says that investment property’s a better investment than buying properties for yourself. You’ve got people frozen out of the finance system. You’ve got people in incredibly leveraged positions forcing up costs. And you have fucking stupid governments saying, ‘We’ll give more subsidies.’ Don’t give any more fucking subsidies. Supply is a problem, not demand. …“The strategy should be very fucking simple: build more houses so that every young person can aspire to own a home. So what do you do? You plan for the inner city. We’re gonna completely redesign Broadmeadows. We’re gonna completely redesign Collingwood. We will do the buying for you. We will organise the finance. We will get the lowest possible cost. We will overcome local council regulations. We will do that for you. It shouldn’t be that hard. It should also be an exciting thing to do. But there’s excuses. There’s a lot of good talkers, but they don’t do anything. My whole life, I was told things were impossible. Medicare was impossible. Super was impossible. But it happened.” …

As it is, Kelty argues that government expenditure – and his criticisms are predominantly of the Victorian government – should be condemned not for its inflationary consequence but its wastefulness. “We should be saying that we won’t be wasting your money … for a road that was never built, or a Commonwealth Games we never had, or a railway plan that we don’t really know what the business case is.”

[T]he AUKUS policy has infuriated Kelty. … His complaint is that the government has bitterly discouraged debate about it. “This government has not engaged any of the AUKUS critics and sceptics: not Keating, not Hugh White, not Malcolm Turnbull, not Sam Roggeveen, James Curran, or any of their once-trusted former advisers who opposed it,” he said in his September speech. “They have listened to no one, old or young … The debate will never happen. No serious inquiry will ever be conducted.”

Quite!

Trying to figure out why Trump won?

This tweet thread was better than a poke in the eye. (On the other hand, I’d have taken a poke in the eye rather than President Trump Two Point Crazy.) Anyway, click through and see what you think.

Springtime for Ned Morgan

DEI and the pyramid of code

Given the tenor of the times, given the triumph of anti-woke sentiment during the week, the time might be apposite for some reflection on DEI. Here’s a sketch of our progress as a species. I follow it up with an extract from a recent article on “how to get DEI right”.

We’re the primate that cooperates to solve problems in groups.

Language was the first technology that scaled this phenomenon

Then as cities and written language developed, we learned to entangle ourselves in code (like Hammurabi’s code) — as if life could be contained not just within language (which it can’t) but within reductive written codes.

Even with very basic moral rules — thou shall not kill — code leaves out a lot. You can codify the exceptions, but those sub-codifications still leave out a lot too.

And being ‘fair’ is super hard to codify. But DEI tries (at least regarding certain issues that swam to the top of our consciousness at a certain time in history).

That’s all good, as far as it goes, but then we get carried away with the code.

We give too much weight to following the code — eg making promotions more demographically representative as being ‘fair’ — and too little to the ways in which the code might be leading us astray. And too little to the ways in which it encodes the power of the powerful.

And then we get all self-righteous towards those who aren’t playing along.

Those we’ve gotten ourselves self-righteous about get pisssed off about this and vote for Donald Trump — as is their right.

How To Fix DEI

A number of diversity trainings have been found to activate bias instead of decreasing it. For instance, one study found that asking White college students who identify with their Whiteness to consider “White privilege” increased their racial resentment. Another experiment showed that when White Americans who identified strongly with their Whiteness were shown messages related to multiculturalism, it increased their sense of threat—which in turn heightened their prejudice and made them want to be more dominant over other groups. In fact, just learning about a coming minority-majority America led Whites in one experiment to express more bias and spend more time with other Whites. Another study found that Anglo men self-reported less positive attitudes towards women after diversity education.

Studies demonstrating that DEI interventions may trigger retrograde attitudes are worrying. Even more concerning are evaluations that show behavioral changes that increase inequality. In lab experiments, men who supported the traditional gender hierarchy reacted to a perceived threat to their status by discriminating against a hypothetical woman’s resume. The same holds in real life: a look at mandatory corporate diversity initiatives found that they led to a nearly ten percent decrease in Black women in management, a five percent decrease in Asian American managers, and no offsetting increase for Black men or Hispanics.

Meanwhile, a host of studies shows that White men are particularly likely to avoid diversity trainings in the first place, which has led many universities to make their DEI programs mandatory. But that “solution” is even more problematic. Being forced to take any type of compulsory program is associated with backlash—people don’t like to be forced to do things. The backlash generated by mandatory DEI training has been found in many different studies and situations. The issue is not always participants who begin the program as more racist or misogynistic. In many cases participants simply rebel against compulsion—one study suggested that participants who felt socially compelled to reduce prejudice ended up showing greater bias, both explicit and implicit, than they had prior to the intervention. …

Luckily, we have reams of research dating back to the 1960s about how to foster positive relationships and understanding across difference—and how to reduce prejudice. Since the 1960s, social contact theory (not to be confused with social contract theory from political science) has been found to be highly effective, especially for young people in the United States, on whom it has been most tested. Programs that foster contact across difference allow people the vulnerability to question and diffuse their own prejudices.

Particularly for people resistant to change, social contact, emphasizing what people have in common, and fostering positive feelings and relationships, is just what the doctor ordered. In fact, serious studies have shown that programs grounded in social contact theory can change behavior even when people don’t think they’ve changed—as when Christians and Muslims in Iraq who underwent a social contact-based soccer program reduced their prejudicial discrimination in real life—even while reporting unchanged attitudes. As researchers Dobbin and Kalev found in a study of diversity training in corporations, many of the most effective programs fostered contact across difference but were not designed to reduce prejudice; they managed to reduce prejudice as a side effect of bringing people together for extended time as equals to accomplish common goals. Nor is social contact only good for changing the attitudes of the dominant group (the first of the three pluralist goals)—cross-group friendships also are important for building a sense of belonging among marginalized identities.

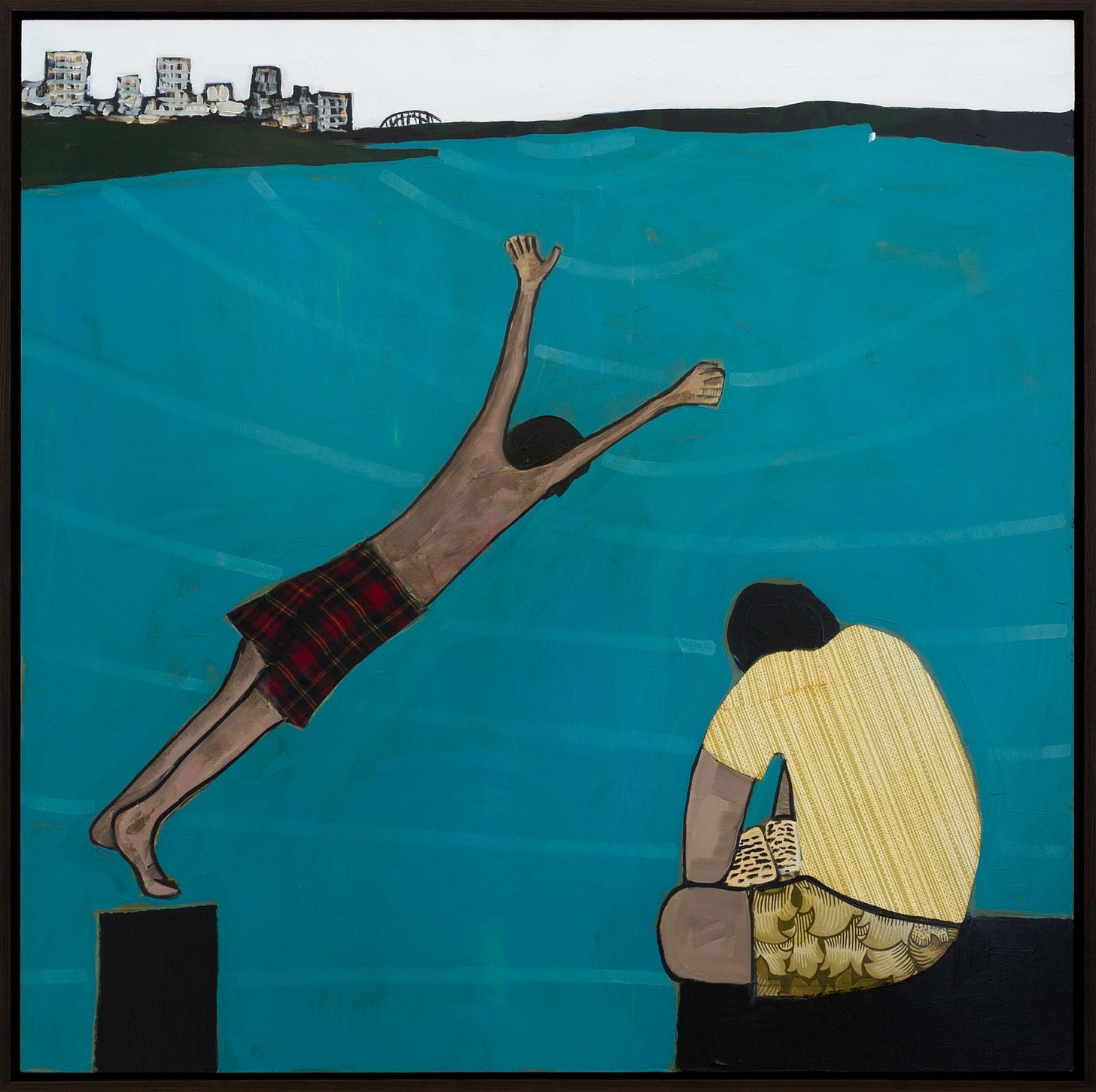

It wasn’t all scorched earth and stolen kids

As Manning Clark intimated what an extraordinary experiment to start in 1788. Two utterly different civilisations come into conflict without intending each other any harm. A civilisation at the peak of a new Enlightenment on the one hand. A culture tens of thousands of years old on the other. What miracles might it have wrought?

Well the interaction mainly brought incomprehension which isn’t surprising, and then — well disaster and devastation. But there were green shoots heading in more fertile directions. I can’t do it justice with my extracts below (surprising how often lopping a few paragraphs only improves things even for quite good articles ;). In any event, you might like to click through to the article.

The fascinating story of how two new books — Sandhill Girl and Enlightened Aboriginal Futures — came into being centres on three people: the Lutheran missionary F.W. Albrecht, his former student Lorna Wilson, and Lorna’s son Barry.

Albrecht, who had come to Australia in 1925, worked in Mparntwe/Alice Springs in the 1950s. There he established an enlightened and culturally sensitive education scheme for Aboriginal students that ran counter to prevailing stolen-generation practices.

Lorna was one of the first students in the scheme, and Sandhill Girl is her memoir of growing up and obtaining an education west of Mparntwe/Alice Springs. “I wanted to learn,” she declares. In 1968 she gave birth to a son, Barry, and passed on to him her passion for education. Today Barry is a leading scholar in Australian Indigenous studies and deputy vice-chancellor (Indigenous) at the University of Melbourne. Together with the historian Katherine Ellinghaus, he examines Albrecht’s education scheme in Enlightened Aboriginal Futures, closing the loop back to the missionary. …

Albrecht’s predecessor, Carl Strehlow, had served as pastor from 1894 until 1922. He attained an understanding unparalleled among Europeans of the language and culture of the Aranda and Luritja people, as recorded in his monumental work Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stämme in Zentral-Australien (The Aranda and Luritja Clans of Central Australia), published between 1907 and 1920. He died in 1922 on an excruciating quest for medical treatment recounted years later by his son T.G.H. Strehlow in the epic Journey to Horseshoe Bend. True to the missionary approach, the book draws on Aranda language and knowledge of Country alongside German Lutheranism and classical literature. …

The second project, studied for the first time by Judd and Ellinghaus, was Albrecht’s educational scheme, developed after 1952 when his wife Minna’s health problems forced the family to move to Mparntwe/Alice Springs. Albrecht continued his work as pastor and spent hours bringing in and arranging for children from surrounding stations and settlements to attend primary school in the town.

He soon became concerned that this schooling didn’t set children up well for life. With no high school in the town, primary school led neither to employment nor to further schooling or training, leaving young students in limbo. Albrecht’s scheme involved young Indigenous students moving south to live with hosts from Lutheran congregations and attend local state schools followed by Lutheran secondary schools.

Judd and Ellinghaus adduce strong evidence to show that, in contrast to stolen-generation practices, the scheme was informed by energetic input from Indigenous people and responded to their desire for further education. While recognising the contested nature of consent when a power imbalance exists, they show that agreement from the students and their families was integral to the scheme.

Because girls — Lorna Wilson among them — stood out at primary school and were encouraged by their families to continue their education, they came to be focus of the program. “Leaving was my choice,” she writes, but difficult the decision was bolstered by her elder brother. “My brother said, ‘You go and learn, go and learn… It will be good for you to learn another culture. You go and learn.’ I listened to my brother because I looked up to him.” …

Rather than expunging their Indigenous culture, Albrecht’s scheme encouraged students to keep connected to their homes, language and culture and provided ways and means to achieve that. It enabled students to withdraw at any time and to return home for the long summer holidays, and encouraged communication among the students themselves and with home base in Central Australia. “Pastor Albrecht made sure that I never lost contact with my family,” Lorna writes. “I always came back to my family.” Later in life she worked as a translator and interpreter of the central and western desert languages Pitjantjatjara and Luritja. This was a great advance on what had earlier troubled Albrecht about schooling for Aboriginal students: “They have lost their past, but not gained the future.”

The metaphor that dominates Albrecht’s scheme and Lorna’s memoirs is opening doors. Host families opened their doors to the students. Education then opened up opportunities for the students without closing them on their cultural background. Albrecht “opened doors and I went through them,” writes Lorna. “I feel like I’m richer for it, because I haven’t lost my culture in the process of doing that — with his help. He was a kind old man.” As an early participant in the scheme and one of the first three Aboriginal students at St Paul’s College, she proudly states, “we opened that door for other Aboriginal kids.”

A ponderous pic

Toyota as an institution of human ascent

The other day I was looking at stuff I’d written on Toyota and came upon this column I’d written over a decade ago — which I’d forgotten. It’s quite good. I had definitely forgotten the illustration by fated Australian op-ed illustrator John Spooner. I’m glad to have it too, though note the ideological slant. The illustration just had to attribute the triumph to the Japanese Government outfit the Ministry for Trade and Industry — which was a big talking point in the interminable ideological debate about markets versus governments. Yet the column had said nothing about it.

I first came upon the remarkable achievement of Japanese manufacturing in 1983 when working on the new car plan for my boss, John Button. I was awed at how the Japanese had somehow designed an entire new system of industrial production and human relations which somehow crossed that yawning chasm between managing to minimise bad behaviour and giving people the tools and motivation to do their best.

It’s a lot easier said than done. And the story has gone on, from the Japanese getting the best out of their workers and suppliers to us getting the best out of ourselves and each other on the internet.

It takes me back to Adam Smith – the founder of modern economics – explaining how slavery seemed like the cheapest form of labour but was really the most expensive because the slave had no stake in his own productivity. If he had particular aptitude or suggested ways to economise on his own labour he’d get none of the benefits and would probably cop a beating for laziness.

Before Toyota radically redesigned it, factory production was built on managers’ need to cut costs and speed up the line. They used largely unskilled labourers whose incentive to work mixed fear and need with job insecurity, piece rates and/or production targets.

But Toyota showed how cheap labour was really more expensive. They spent ten times their American competitors did on training and they treated their workforce as ‘knowledge workers’. Rather than pushing them to keep up with a production line over which they had no control, workers were organised into cooperative teams which endlessly met to optimise their productivity in ‘quality circles’.

Eliminating waste was a great catchcry. But in Toyota’s hands it was infused with purpose and almost zen-like meaning. It sought to eliminate three kinds of waste each identified with a simple Japanese word:

Muda – triviality or unproductiveness;

Mura – unevenness or irregularity; and

Muri – unreasonableness or absurdity.

Toyota factories used less space and reduced inventory holdings from weeks to hours. But the savings on rent and interest weren’t really the point. Workers were steeped in statistical control so they could endlessly hunt down mura or irregularities. This revealed various processes for the muda (trivialities) – and muri (absurdities) that they were – for instance inspecting quality in after mistakes had been made rather than getting it right first time.

‘Just in time’ inventory further forced the elimination of irregularities and accelerated the feedback by which problems could be identified and solutions found. It also drew suppliers into the system and built trusting long-term relationships in which product and process design were shared between suppliers and the car maker.

The result was extraordinary. Japanese plants often doubled the West’s labour productivity while achieving much higher quality. When the Americans returned to learn from Toyota they often imitated tokens and tricks – like reduced inventory and quality circles. But as one of the architects of the new system, American process control engineer Edwards Deming observed, they copied, but “they don't know what to copy!” For they were encountering a whole system which relied as much on its understanding of people as it did on technology and systems.

Toyota’s ideas have spread throughout most Japanese manufacturing and have been transplanted on foreign shores. But, to my surprise and disappointment, none of this captured economists’ imagination. They’ve heard of ‘just-in-time’ production but regard it as no more than a shift of a curve on one of their diagrams.

It’s not utopia, but the move from adversarial, rent seeking, fearful workplaces to Toyota’s more enlightened system was something that Adam Smith would have immediately recognised as progress in the broadest sense of the term.

Toyota’s past achievements also pointed to the future. In tapping into the unique capabilities of all its people, not just in its own factories, but in those of all its suppliers’, it anticipated today’s networked approaches. Indeed anticipating of ‘open source’ production methods, Toyota insisted that its own and its suppliers’ facilities become a ‘knowledge commons’ in which firms would actively help each other by sharing their expertise.

And one of the great strengths of open source production – for instance coding open source software like Linux or contributing to Wikipedia – is the way it taps into intrinsic motivation. People do it because they want to and because they care about the outcome. Eric S. Raymond, geek and author of an early bible on open source, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, could be channelling Toyota’s obsession with eliminating waste when he observes that “Painful development environments waste labor and creativity; they extract huge hidden costs in time, money, and opportunity.”

Which brings me back to Adam Smith who, gazed on the great promise of early capitalism and dreamt that human freedom, capability, dignity, and wealth might grow together. That’s better than some shift on an economist’s diagram.

Published in the Age and SMH on Wed May 30th, 2012 as “Inspired system inspires workers”.

View exhibition online here

Interpreting treaties with indigenous peoples

Treaties with indigenous peoples sound like a good thing. Perhaps they are. But what I wonder about in the Australian context is that a treaty sounds like a good idea, but once you get to negotiate it, you run into all the power imbalances the treaty is supposed to help with. And if we’re not prepared to address those power imbalances in the specific circumstances where they assert themselves, why would we expect to do any better doing so in the abstract? And to what extent can they be addressed in the abstract, and with the assistance of lawyers (at upwards of $5,000 a day)?

In that context I found this article pretty fascinating to ponder. The extract is a little bowdlerised but may take you into the issues more quickly. If you want to be more careful, click through immediately.

Treaty principles were introduced into the governance of New Zealand by the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 whose purpose was ‘to determine whether certain matters are inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty.’ …

In 1989 the New Zealand government responded to the Court of Appeal with a set of principles. No subsequent government has modified them. They were:

The government has the right to govern and make laws. (The kāwanatanga principle)

Iwi have the right to organise as iwi, and, under the law, to control their resources as their own. (The rangatiratanga principle)

All New Zealanders are equal before the law.

Both the government and iwi are obliged to accord each other reasonable cooperation on major issues of common concern.

The government is responsible for providing effective processes for the resolution of grievances in the expectation that reconciliation can occur.

As lawyers have pointed out, Article 3 of Te Tiriti applies to all New Zealanders. If the term ‘Māori’ is replaced by ‘New Zealander’ and the term ‘iwi’ by ‘voluntary associations’ the above principles are those intrinsic to the governance of a civilised liberal democracy. …

So how are we to judge ACT’s proposed Treaty Principles Bill? The bill is not yet before Parliament, but ACT’s manifesto said it would define the principles of the treaty as:

The New Zealand Government has the right to govern New Zealand.

The New Zealand Government will protect all New Zealanders’ authority over their land and other property.

All New Zealanders are equal under the law, with the same rights and duties.

The proposal looks like an attempt to redefine Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Evolving the interpretation of past events is organic; putting one in statute is not; it fossilises it. At a deeper level, it is not unusual for an authoritarian state to reinterpret history to suit itself. (Witness Putin about the history of the Ukraine.)

While its principles 1 and 3 are consistent with those of the Court of Appeal, the ACT proposal omits other key treaty principles. One is uneasy that we should pass a law which seems to repeal so casually the deliberations of the courts on such weighty matters, especially as those that underpin a liberal democracy.

ACT’s Principle 2 is narrower than the principles set out by the Court of Appeal. It is a limited interpretation of the second article of Te Tiriti, reflecting the neoliberal view that it is only about private property rights. Māori had few of those in 1840; property rights were held by the community, much to the frustration of Europeans who wanted to acquire land. Neoliberals object to community ownership. (Elinor Ostrom was made a Nobel Laureate in 2009 for her work explaining how such collective ownership can work very effectively.)

Moreover, the second article of Te Tiriti covers far more that what we conventionally think of as private property. We can see that from the evolution of the drafts of the treaty. Up to what is called the ‘English version’ there was a list – ‘Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties’. The text signed on the treaty grounds jumps to ‘ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa’– ‘their lands, their villages and all their treasured things’. (Because translators would not make that jump, I am of the view there was a revised English draft from which Te Tiriti was translated; it probably ended up in Colenso’s – now lost – papers.)

‘Taonga katoa’ is a very strong term – much more encompassing than ACT’s ‘other property’. For instance, the courts have ruled that ‘te reo’ is one of those taonga. Had this been raised with Māori on 6 February 1840 – unlikely because people didn’t think that way then – the Māori response would probably have been ‘he aha to tikanga?’ – ‘what do you mean?’ Ask it today, the response is a very positive ‘āe, āe’.

My thinking is greatly influenced by Edmund Burke and, indeed, Friedrich Hayek when he is not a neoliberal. They saw organic development at the core of social progress. Sometimes the government has to accelerate or enable it. It should avoid retarding it or fossilising it. That is what the ACT proposal does.

In arguing that the ACT proposal retards organic development and undermines democratic principles, I am not arguing that the party is inherently reactionary or authoritarian. Rather, I don’t think the proponents of the bill have thought these issues through. We shall see how they respond when such issues are drawn to their attention. One hopes they will reaffirm the Court of Appeal’s principles of the treaty which underpin a liberal democracy and adopt a more accurate historical account of the drafting of Te Tiriti and the subsequent organic evolution of its interpretation.

Heaviosity Half-Hour

Hannah Arendt: The human condition

IRREVERSIBILITY AND THE POWER TO FORGIVE

We have seen that the animal laborans could be redeemed from its predicament of imprisonment in the ever-recurring cycle of the life process, of being forever subject to the necessity of labor and consumption, only through the mobilization of another human capacity, the capacity for making, fabricating, and producing of homo faber, who as a toolmaker not only eases the pain and trouble of laboring but also erects a world of durability. The redemption of life, which is sustained by labor, is worldliness, which is sustained by fabrication. We saw furthermore that homo faber could be redeemed from his predicament of meaninglessness, the “devaluation of all values,” and the impossibility of finding valid standards in a world determined by the category of means and ends, only through the interrelated faculties of action and speech, which produce meaningful stories as naturally as fabrication produces use objects. If it were not outside the scope of these considerations, one could add the predicament of thought to these instances; for thought, too, is unable to “think itself” out of the predicaments which the very activity of thinking engenders. What in each of these instances saves man—man qua animal laborans, qua homo faber, qua thinker—is something altogether different; it comes from the outside—not, to be sure, outside of man, but outside of each of the respective activities. From the viewpoint of the animal laborans, it is like a miracle that it is also a being which knows of and inhabits a world; from the viewpoint of homo faber, it is like a miracle, like the revelation of divinity, that meaning should have a place in this world.

The case of action and action’s predicaments is altogether different. Here, the remedy against the irreversibility and unpredictability of the process started by acting does not arise out of another and possibly higher faculty, but is one of the potentialities of action itself. The possible redemption from the predicament of irreversibility—of being unable to undo what one has done though one did not, and could not, have known what he was doing—is the faculty of forgiving. The remedy for unpredictability, for the chaotic uncertainty of the future, is contained in the faculty to make and keep promises. The two faculties belong together in so far as one of them, forgiving, serves to undo the deeds of the past, whose “sins” hang like Damocles’ sword over every new generation; and the other, binding oneself through promises, serves to set up in the ocean of uncertainty, which the future is by definition, islands of security without which not even continuity, let alone durability of any kind, would be possible in the relationships between men.

Without being forgiven, released from the consequences of what we have done, our capacity to act would, as it were, be confined to one single deed from which we could never recover; we would remain the victims of its consequences forever, not unlike the sorcerer’s apprentice who lacked the magic formula to break the spell. Without being bound to the fulfilment of promises, we would never be able to keep our identities; we would be condemned to wander helplessly and without direction in the darkness of each man’s lonely heart, caught in its contradictions and equivocalities—a darkness which only the light shed over the public realm through the presence of others, who confirm the identity between the one who promises and the one who fulfils, can dispel. Both faculties, therefore, depend on plurality, on the presence and acting of others, for no one can forgive himself and no one can feel bound by a promise made only to himself; forgiving and promising enacted in solitude or isolation remain without reality and can signify no more than a role played before one’s self.

Since these faculties correspond so closely to the human condition of plurality, their role in politics establishes a diametrically different set of guiding principles from the “moral” standards inherent in the Platonic notion of rule. For Platonic rulership, whose legitimacy rested upon the domination of the self, draws its guiding principles—those which at the same time justify and limit power over others—from a relationship established between me and myself, so that the right and wrong of relationships with others are determined by attitudes toward one’s self, until the whole of the public realm is seen in the image of “man writ large,” of the right order between man’s individual capacities of mind, soul, and body. The moral code, on the other hand, inferred from the faculties of forgiving and of making promises, rests on experiences which nobody could ever have with himself, which, on the contrary, are entirely based on the presence of others. And just as the extent and modes of self-rule justify and determine rule over others—how one rules himself, he will rule others—thus the extent and modes of being forgiven and being promised determine the extent and modes in which one may be able to forgive himself or keep promises concerned only with himself.

Because the remedies against the enormous strength and resiliency inherent in action processes can function only under the condition of plurality, it is very dangerous to use this faculty in any but the realm of human affairs. Modern natural science and technology, which no longer observe or take material from or imitate processes of nature but seem actually to act into it, seem, by the same token, to have carried irreversibility and human unpredictability into the natural realm, where no remedy can be found to undo what has been done. Similarly, it seems that one of the great dangers of acting in the mode of making and within its categorical framework of means and ends lies in the concomitant self-deprivation of the remedies inherent only in action, so that one is bound not only to do with the means of violence necessary for all fabrication, but also to undo what he has done as he undoes an unsuccessful object, by means of destruction. Nothing appears more manifest in these attempts than the greatness of human power, whose source lies in the capacity to act, and which without action’s inherent remedies inevitably begins to overpower and destroy not man himself but the conditions under which life was given to him.

The discoverer of the role of forgiveness in the realm of human affairs was Jesus of Nazareth. The fact that he made this discovery in a religious context and articulated it in religious language is no reason to take it any less seriously in a strictly secular sense. It has been in the nature of our tradition of political thought (and for reasons we cannot explore here) to be highly selective and to exclude from articulate conceptualization a great variety of authentic political experiences, among which we need not be surprised to find some of an even elementary nature. Certain aspects of the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth which are not primarily related to the Christian religious message but sprang from experiences in the small and closely knit community of his followers, bent on challenging the public authorities in Israel, certainly belong among them, even though they have been neglected because of their allegedly exclusively religious nature. The only rudimentary sign of an awareness that forgiveness may be the necessary corrective for the inevitable damages resulting from action may be seen in the Roman principle to spare the vanquished (parcere subiectis)—a wisdom entirely unknown to the Greeks—or in the right to commute the death sentence, probably also of Roman origin, which is the prerogative of nearly all Western heads of state.

It is decisive in our context that Jesus maintains against the “scribes and pharisees” first that it is not true that only God has the power to forgive,76 and second that this power does not derive from God—as though God, not men, would forgive through the medium of human beings—but on the contrary must be mobilized by men toward each other before they can hope to be forgiven by God also. Jesus’ formulation is even more radical. Man in the gospel is not supposed to forgive because God forgives and he must do “likewise,” but “if ye from your hearts forgive,” God shall do “likewise.”77 The reason for the insistence on a duty to forgive is clearly “for they know not what they do” and it does not apply to the extremity of crime and willed evil, for then it would not have been necessary to teach: “And if he trespass against thee seven times a day, and seven times in a day turn again to thee, saying, I repent; thou shalt forgive him.”78 Crime and willed evil are rare, even rarer perhaps than good deeds; according to Jesus, they will be taken care of by God in the Last Judgment, which plays no role whatsoever in life on earth, and the Last Judgment is not characterized by forgiveness but by just retribution (apodounai).79 But trespassing is an everyday occurrence which is in the very nature of action’s constant establishment of new relationships within a web of relations, and it needs forgiving, dismissing, in order to make it possible for life to go on by constantly releasing men from what they have done unknowingly.80 Only through this constant mutual release from what they do can men remain free agents, only by constant willingness to change their minds and start again can they be trusted with so great a power as that to begin something new.

In this respect, forgiveness is the exact opposite of vengeance, which acts in the form of re-acting against an original trespassing, whereby far from putting an end to the consequences of the first misdeed, everybody remains bound to the process, permitting the chain reaction contained in every action to take its unhindered course. In contrast to revenge, which is the natural, automatic reaction to transgression and which because of the irreversibility of the action process can be expected and even calculated, the act of forgiving can never be predicted; it is the only reaction that acts in an unexpected way and thus retains, though being a reaction, something of the original character of action. Forgiving, in other words, is the only reaction which does not merely re-act but acts anew and unexpectedly, unconditioned by the act which provoked it and therefore freeing from its consequences both the one who forgives and the one who is forgiven. The freedom contained in Jesus’ teachings of forgiveness is the freedom from vengeance, which incloses both doer and sufferer in the relentless automatism of the action process, which by itself need never come to an end.

The alternative to forgiveness, but by no means its opposite, is punishment, and both have in common that they attempt to put an end to something that without interference could go on endlessly. It is therefore quite significant, a structural element in the realm of human affairs, that men are unable to forgive what they cannot punish and that they are unable to punish what has turned out to be unforgivable. This is the true hallmark of those offenses which, since Kant, we call “radical evil” and about whose nature so little is known, even to us who have been exposed to one of their rare outbursts on the public scene. All we know is that we can neither punish nor forgive such offenses and that they therefore transcend the realm of human affairs and the potentialities of human power, both of which they radically destroy wherever they make their appearance. Here, where the deed itself dispossesses us of all power, we can indeed only repeat with Jesus: “It were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and he cast into the sea.”

Perhaps the most plausible argument that forgiving and acting are as closely connected as destroying and making comes from that aspect of forgiveness where the undoing of what was done seems to show the same revelatory character as the deed itself. Forgiving and the relationship it establishes is always an eminently personal (though not necessarily individual or private) affair in which what was done is forgiven for the sake of who did it. This, too, was clearly recognized by Jesus (“Her sins which are many are forgiven; for she loved much: but to whom little is forgiven, the same loveth little”), and it is the reason for the current conviction that only love has the power to forgive. For love, although it is one of the rarest occurrences in human lives,81 indeed possesses an unequaled power of self-revelation and an unequaled clarity of vision for the disclosure of who, precisely because it is unconcerned to the point of total unworldliness with what the loved person may be, with his qualities and shortcomings no less than with his achievements, failings, and transgressions. Love, by reason of its passion, destroys the in-between which relates us to and separates us from others. As long as its spell lasts, the only in-between which can insert itself between two lovers is the child, love’s own product. The child, this in-between to which the lovers now are related and which they hold in common, is representative of the world in that it also separates them; it is an indication that they will insert a new world into the existing world.82 Through the child, it is as though the lovers return to the world from which their love had expelled them. But this new worldliness, the possible result and the only possibly happy ending of a love affair, is, in a sense, the end of love, which must either overcome the partners anew or be transformed into another mode of belonging together. Love, by its very nature, is unworldly, and it is for this reason rather than its rarity that it is not only apolitical but antipolitical, perhaps the most powerful of all antipolitical human forces.

If it were true, therefore, as Chrsitianity assumed, that only love can forgive because only love is fully receptive to who somebody is, to the point of being always willing to forgive him whatever he may have done, forgiving would have to remain altogether outside our considerations. Yet what love is in its own, narrowly circumscribed sphere, respect is in the larger domain of human affairs. Respect, not unlike the Aristotelian philia politikē, is a kind of “friendship” without intimacy and without closeness; it is a regard for the person from the distance which the space of the world puts between us, and this regard is independent of qualities which we may admire or of achievements which we may highly esteem. Thus, the modern loss of respect, or rather the conviction that respect is due only where we admire or esteem, constitutes a clear symptom of the increasing depersonalization of public and social life. Respect, at any rate, because it concerns only the person, is quite sufficient to prompt forgiving of what a person did, for the sake of the person. But the fact that the same who, revealed in action and speech, remains also the subject of forgiving is the deepest reason why nobody can forgive himself; here, as in action and speech generally, we are dependent upon others, to whom we appear in a distinctness which we ourselves are unable to perceive. Closed within ourselves, we would never be able to forgive ourselves any failing or transgression because we would lack the experience of the person for the sake of whom one can forgive.

Some powerful pieces here Nicholas - the central Australian experience with Lutheran mission leaders and education - the Hannah Arendt musings - promises and forgiveness etc - and the excellent if brief explanation by Jeffrey Sachs about US/UK malfeasance re the 600,000 dead Ukrainians - which never needed to happen except neocons and Nuland and Biden et al. Thanks.