Science: How it obscures reality

And other great things I found on the net this week

More from me on wellbeing

An enjoyable discussion with ABC Brisbane’s Steve Austin. The audio is here.

Advice for aspirant CEOs: it’s not about you

If you fancy being a CEO, McKinsey and Company have news for you. It’s not about you. You do it for the team. You do it for the humility. It’s a little like Christ said about the poor and meek inheriting the earth. They don’t actually say here that you shouldn’t take millions for taking on the job. They don’t mention the private jets either. But I expect that was an oversight. They certainly have in mind that you should inherit the earth. Humble is as humble does. Look after the little people and the private jets will look after themselves.

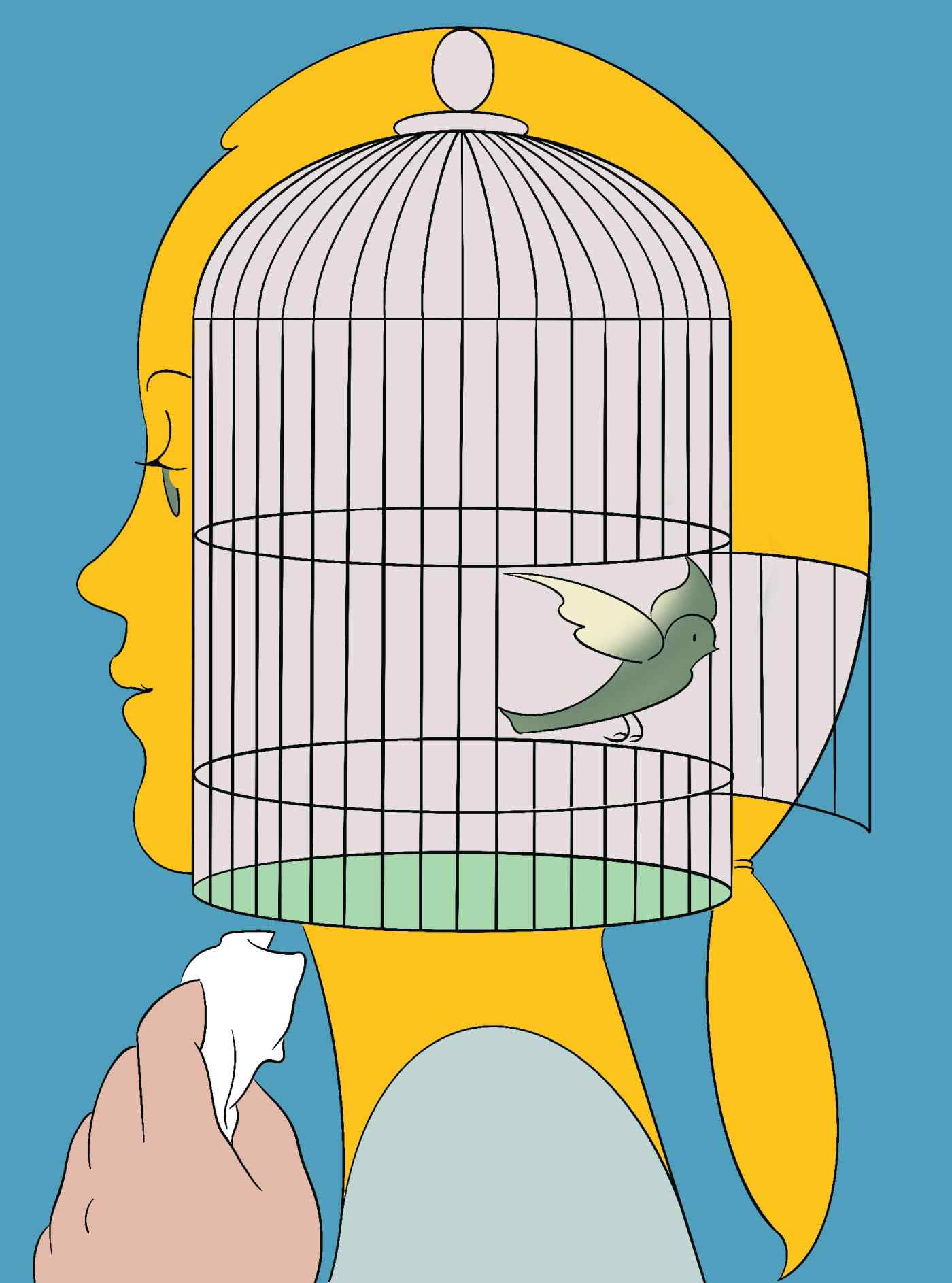

I’d never stuck with therapy. Then I tried psychoanalysis

A novelist and essayist with a masters degree in maths and physics was turned off by counselling, CBT and mindfulness but ‘clicked’ with psychoanalysis.

Once in a psychoanalysis session, I cried and laughed at the same time. The energies of each separate, simultaneous outburst seemed to feed each other until I was both cackling in an almost crazed fashion and wailing wretchedly. It was as strange as it sounds. And once it had started, it seemed as if it would never stop. I wondered if they would eventually morph into the same strange, wild thing. But they never did. There was always a discernible separateness. It burnt out after a little while, the way a fit of laughter always does.

My analyst was laughing with me. Then she shook her head and said: “Well, what on earth was that? I have never seen that before.” I laughed too (normal laughter) and told her I didn’t really know, I had never seen or done it before either. I asked her if she thought that laughter and crying could be an outlet for the same emotion, and if maybe that meant I felt something so strongly that I expressed it in both ways. Laughter is associated with joy, but it can also be a release, a coping mechanism, a distraction or many other things. Crying can be a form of relief. Relief sometimes feels close to joy. And joy is often framed by a tinge of sadness, and vice versa.

She told me she agreed that, yes, that was all true. But she suggested I was trying to talk around the fact I had done them both, separately, at the same time (I was). And that I was trying to move the conversation away from what we had been talking about before it started (I was). We were talking about a type of relationship I have often had that I keep separate from everything else I do. A relationship with a kind of person who doesn’t seem to fit with the rest of my life. The quality of separateness, she suggested, was both the striking thing about my emotional response — the separateness of the laughter and the tears — and the interesting aspect of what had caused it.

Except I didn’t start with that clear, simple sentence: “a type of relationship I have often had which I keep separate from everything else I do”. It came up in an offhand way, as interesting things tend to in my experience of analysis. I mentioned someone from my past. My analyst asked how I knew him, and I described our relationship in a universalising way, another trick I use. “Well, he was one of those people, you know, the ones who . . . ” No, she said. She didn’t know people like that. I needed to explain. Again I tried the language of “people” and “you”. She stopped me. “This isn’t something I or everyone else does. This is something you do.”

More questions. Did I like him? Yes, I really liked him. We got on well, I felt like we understood each other. I could have real conversations with him. That was when the laughing that was also crying started. When it stopped, and we talked more about it, my analyst suggested maybe I have two feelings about this that don’t make sense to me together.

We talked about the idea of separateness and eventually came to that clean, tight sentence: “a type of relationship I have often had which I keep separate from everything else I do”. We talked more and arrived at the idea that this kind of separateness has a larger meaning to me too. There are things I do that don’t feel like part of my “real” life. They feel weirder, grottier, darker and more dangerous. The strange thing is, I sometimes wonder if the things that don’t fit are more “real” than the rest of it.

That’s where we left that thought, articulated rather than answered. I don’t know if the question of which is more real is one I’ll ever answer, but I understand myself better for having formed it. That’s where analysis tends to take me. Not to a conclusive end, but to a greater clarity that I can sometimes use for a practical change and sometimes not. I’ve been surprised at how transformative that can be.

Two styles of psychotherapy

Like the guy says, there are two types of psychological service. The first heads fairly quickly to validating the patient. “You say terribly you feel you're being treated and the therapist gives you reassurance that actually your feelings are entirely understandable entirely reasonable … so they reinforce the idea that you're right to be upset and we do find that very comforting when we're upset.” Our therapist argues that there’s “a better kind of therapy where the therapist challenges you and says well to what extent are you partly responsible for why this has happened.”

Michael George is engulfed

Science: How it obscures reality

I enjoyed this discussion with philosophy PhD and high school teacher from San Francisco's Bay area. I tried to articulate my own view that our understanding of science as the paradigm of all knowledge gets in the way of understanding important aspects of reality that science can't help us with. We talk about embodied cognition and various aspects of this essay. If, like me, you prefer just listening to the audio, you can find it here.

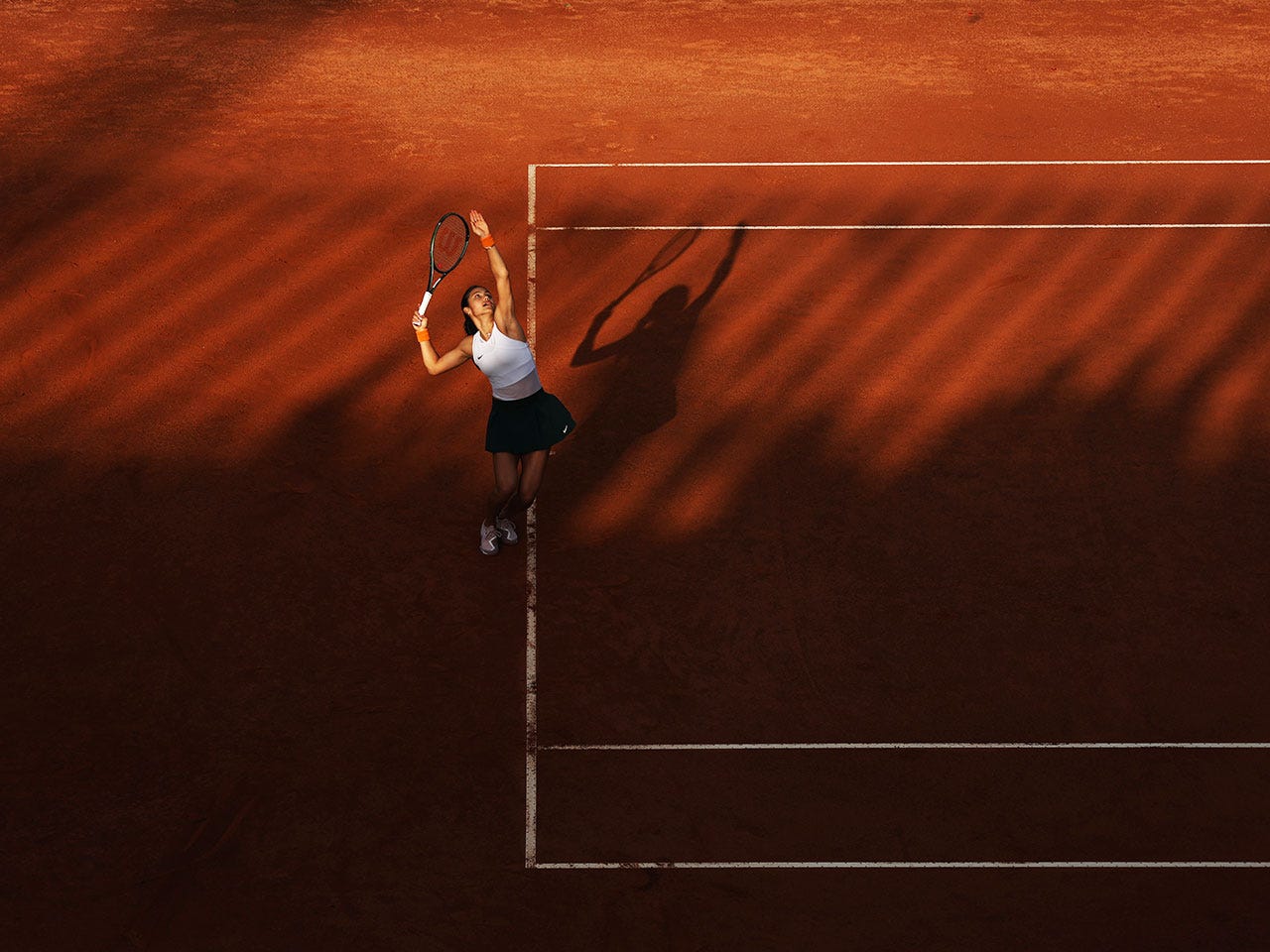

Emma Raducanu: canonised, commodified dehumanised

For an 18-year-old girl with no real expectation or preparation, this in itself would have been a disorientating, concussive experience. “Dehumanisation and canonisation are not polar but related,” Tanya Gold recently wrote in these pages. She was referring to the royal family, but it could apply just as well to young female athletes. The same process that feted Raducanu also appropriated her, instrumentalised and objectified her, converted her into a vessel for our opinions. …

While Raducanu herself has deleted all social media apps from her phone and tried to limit her commercial engagements, the Raducanu-industrial complex always needs to be fed.

Her occasional branded Instagram posts are invariably picked apart by commenters urging her to stop posing and get back on the practice court. “You’re not making this very easy,” a journalist scolded her at one point during her awkward Madrid press conference. In both instances there is a kind of blithe entitlement being expressed: the very modern idea that by dint of her fame and profile, she owes us something every time she gets up in the morning.

Given all this, who can really blame Raducanu for retreating into the sweet agony of the surgeon’s knife? Perhaps, in the long run, the only real way of breaking the cycle is to break out of it.

She is still only 20 years old, an age at which most of us are still making mistakes and finding the size and shape of what matters to us. Some time out of the spotlight, away from the tyranny of expectations, may be exactly what she needs. Time to go back to first principles. Time to rebuild her game and her body. Time to work out what makes her happy, what she really wants out of life. Time to think. Time to breathe. Time, above all, to discover some new answers.

Impertinence

I love the directness with which these two speak to each other. They’re both quite emphatic — indeed exasperated. Yet they remain civil and good humoured.

The art of handling what they used to call 'impertinence' without taking offence is a fine one — and one I'm very bad at. So kudos to the (otherwise unspeakable) Tucker!

Inflation: Brad Delong slaps us into line

As he often does. I hadn’t quite seen it this way, but it’s the right way to see it. Over-egging the pudding on COVID was the right thing to do without a crystal ball — that is doing a bit too much instead of a bit too little (what we’ve done since the GFC) was the right call at the time. And even with hindsight it might have been the right call. How so? Because achieving full employment is a huge prize. Inflation is a downside and should be taken seriously, but if it is properly handled the achievements outweigh the costs. Before citing Brad, I’ll just mention that the Hawke Government ran inflation at around 7% for a decade. The Japanese ran it higher than that for more than that time. Australia’s inflation came thudding to a halt at the next recession. It would have been nice if it were lower, but Australia’s economy did fine with it burbling away at 7%.

And so I do wish Matt Yglesias would go a little bit farther here:

The policy that produced our current situation, including the inflation, was optimal ex ante because it guarded against very real and deadly risks (which did not eventuate).

The policy that produced our current situation, including the inflation, was optimal ex post because it has produced a very strong and good economy—with our current inflation a very minor and surmountable problem.

Matt:

Matthew Yglesias: Greedflation is still fake: ‘Policy [needs to] focus on supply-side reforms that allow for productivity growth and real wage gains. Trying to use price controls to prevent excess demand from transforming into rising profits and prices is only going to generate shortages and make it harder to unwind the underlying pathology…. The architects of ARP deliberately erred on the side of going too big with stimulus and we’re now living with both the upsides and the downsides of that choice. I think the upsides far outweigh the downsides: 1. Prime-age employment is at the highest level of the 21st century. 2. Wages are growing fastest at the bottom of the distribution. 3. Black unemployment is at the lowest level on record. 4. Women’s employment rate is at the highest level on record….

Inflation is bad, but the long-term benefits of a strong labor market are considerable and inflation is a surmountable problem. I believe the choice to go bold on full recovery as soon as possible will work out well in the end. But… we need to make smart, ongoing choices… acknowledging that price increases have been driven by strong demand, and… rationing would make things worse…

Inflation does convince people that the government has messed up: they cannot buy the things they expected to be able to buy with their income at the prices they expected to pay, and it is the business of the government to keep the trains running on time so such disruptions of expectations do not happen.

But people rarely think about general equilibrium enough to realize that, on average, the component of their incomes that is higher because of inflation offsets the inflation—that lower inflation in what they buy would have brought with it lower inflation in what they sell, and they have not really lost out. They only think they have lost out because they suffered from a temporary illusion that their earnings had risen while the prices of the things they bought had not.

Inflation is, it is true, bad:

because it is annoying,

if it leads people to get confused substantially about what their real options, constraints, and opportunities are, and

if it becomes embedded in expectations so that higher unemployment is required to keep it rising further.

So far we have only inflation (1). And there is no question that the benefits from aggressive recovery policy—“1. Prime-age employment… the highest level of the 21st century. 2. Wages… growing fastest at the bottom of the distribution. 3. Black unemployment… the lowest level on record. 4. Women’s employment…t the highest level on record”—vastly outweigh that cost.

So I would hold the line: inflation is bad in the sense that leaving rubber on the road when you rejoin the highway at speed is “bad”. But rejoining the highway at speed so you do not get rear-ended is good. A forty-year record-high share of people satisfied with their jobs is good. Near-record prime-age employment-to-population is good. Strong confidence that the Federal Reserve has inflation under control for the medium term and beyond is good. Next to no inflation risk premium in long-term real interest rates—so that the intertemporal price system encourages investments in growth and the future—is good. We have all of those things. And we would not have them had we been unwilling to leave a little rubber on the road:

You HAVE to watch this — seriously!

Five minutes of sunshine?

John Quiggin argues that the government has quietly abandoned full employment

The stage seemed set for a return to the policies that gave us the postwar Golden Age. But it didn’t take long for the lights to dim. The jobs summit turned into a “jobs and skills summit” dominated by employers complaining about “skills shortages.” It wasn’t so much a shortage of specific skills; rather, employers had come up against the fact that full employment makes it as hard for an employer to fill a vacancy as it is for a worker to find a job. …

And, finally, we come to the budget. The scene had been set by the report from the government’s new Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee, which recommended a large increase in the poverty-level JobSeeker benefit and a commitment to full employment. Labor treasurer Jim Chalmers immediately signalled that the first of these recommendations would be rejected as both unaffordable and politically unpopular.

Eventually the government was shamed into a modest increase in JobSeeker, but full employment disappeared from the agenda. The budget projected an unemployment rate of 4.5 per cent — exceeding estimates of the NAIRU, let alone any measure of full employment based on actual labour market outcomes (such as requirement that there should be as many vacancies as unemployed workers). During his budget speech Chalmers described the rate as “low by historical standards,” effectively confirming that his benchmark is the last fifty years of failure rather than any notion of full employment. He then returned quickly to the central theme of the government’s policy, the need to reduce inflation.

Even this short period of full employment has had hugely beneficial consequences. Workers who previously have been dismissed as unemployable have suddenly found employers willing to take them on. Remote work has persisted since the lockdowns because employers who demand five-day attendance lose workers and can’t find replacements. Even more radical ideas like the four-day week are gaining traction.

With luck, and full employment will persist a little longer. But if it does, no thanks will be due to this Labor government.

Some Green Nuclear Deal Propaganda

Defs worth a look

Google I/O: Project Tailwind

A straight lift from Brad Delong’s substack digest.

Steven Johnson: Project Tailwind: ‘An early look at a new experimental “tool for thought” that I’ve been developing with Google… source-grounded AI…. Tailwind allows you to define a set of documents as trusted sources which the AI then uses as… ground truth… to craft a role for the LLM that is not an all-knowing oracle or your new virtual buddy, but something closer to an efficient research assistant…. Making an on-the-fly glossary based on a specific topic…. Tailwind works extremely well as an extension of my memory. I’ve uploaded my “spark file” of personal notes that date back almost twenty years, and using that as a source, I can ask remarkably open-ended questions… all accompanied by citations if I want to refer to the original direct quotes…The most consequential lie in history?

Worth a quick listen to MT’s highlight video of his podcast.

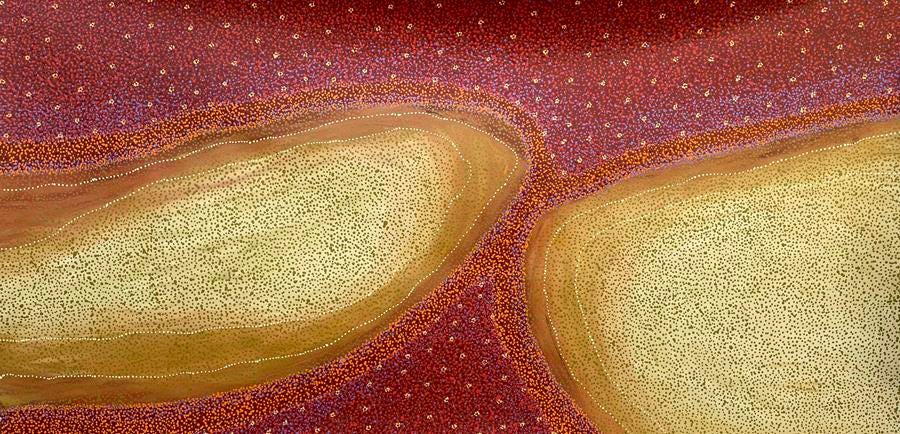

Sonya Edney at Japingka Gallery

Some interesting facts about our Bazza

Together with an obsession which characterising how ‘conservative’ every aspect of his life and makeup were. Who cares?

The Trouble With Elections: from a ‘recovering politician’

And he needs your help: as he explains here.

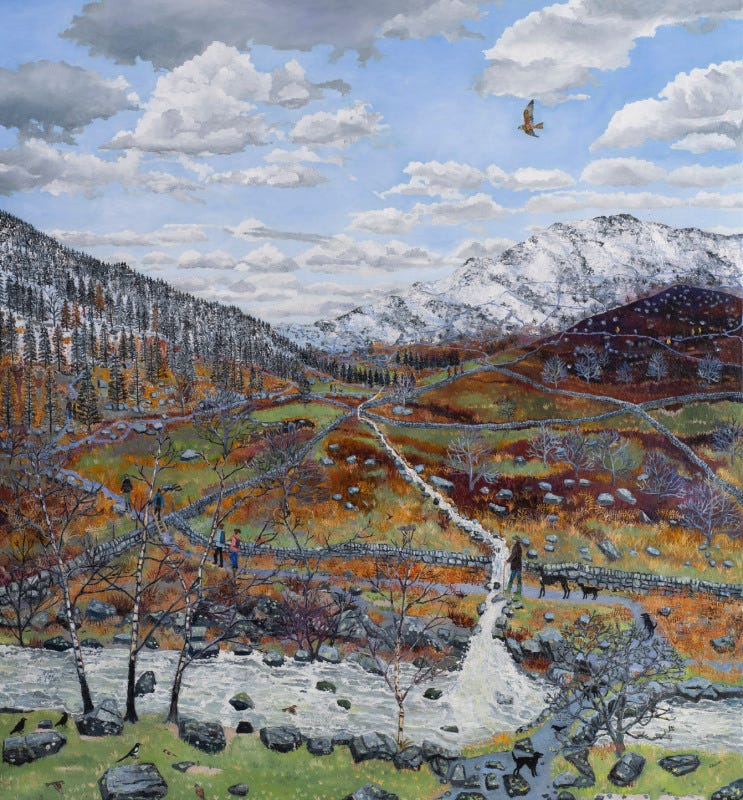

Emma Haworth: Painter of the Seasons

Completely delicious: courtesy of Rebecca Hossack’s London Gallery. Here are as many as you can feast on.

Hilary Cottam: A sad story from Radical Help

I’ve been reading Hilary Cottam’s Radical Help, a remarkable story of a comprehensive attempt to designing the services of the welfare state around the needs of the people we’re trying to help rather than the professionals delivering the services or the system they operate. It’s inspiring stuff, and it convinces me that, in principle the system could be so much better. But for me anyway, there’s a disconnect. Proving that it’s possible, and that technically it can be grown to a considerable scale, does not look the pathologies of the system in the eye. The system has powerful imperatives — namely keeping senior managers and politicians safe. One can complain about that, but expecting a system which tolerates large risks for them is like expecting a for profit economic system to do things that are unprofitable. They can be done by a heroic few, but they die out in a competitive system. Thus to give these fine initiatives the chance to take hold within the system we must find effective hacks by which these programs could satisfy the institutional imperatives that are currently preventing much progress being made. That’s a problem I’ve been pondering since I ran into the kinds of methods Cottam pioneered at The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI).

In any event, here’s her sad story of how hard it is to grow success.

Sometimes the concepts aren’t understood. And sometimes the concepts are well understood but they are deemed to be too challenging, and in many different ways existing systems and those who lead them try to resist. Resistance can be forceful and overt: we could not continue with Loops. Or it can be small and surreptitious: a programme takes on the new language, but it is only speaking in new ways to veil the fact it is still fixing in old ways. The Family Nurse Partnership has been described to me as ‘relational’. In this programme a named nurse is allocated to a pregnant, usually young woman. The nurse’s role, however, is not to work at the pace of the young woman and to support the growth of her capabilities, it is to refer her to programmes that will tackle problems such as smoking or lack of exercise in traditional (and unsuccessful) ways. Relationships are being used as an efficient gateway to existing services, not as a foundation for new practice.3

Resistance can be presented as a technical problem. The LifeBoard was a digital platform we designed to enable the Life team to spend less time on administration. To be fully effective, the LifeBoard had to connect to existing systems. This was resisted by private corporations, who had won contracts to run local government back offices. These corporations feared our incursions into areas that provided them with lucrative contracts. They put up successive barriers, claiming that our technology simply could not connect, or that their confidentiality agreements did not allow us to collaborate. In most cases we could eventually find workarounds for problems that were not actually technical in nature, but we were not able to develop the LifeBoard to its full potential.

Each of the experiments faced challenges. These were not always foreseen. We had not expected that some in the established, national voluntary sector organisations with a mission to support older people would be bitterly opposed to Circle. But, unlike smaller locally rooted community organisations in this sector, who always saw the potential of Circle as a platform through which they could grow their influence and good work, these larger organisations feared that the success of Circle would be interpreted as a critique of their own approaches and might also limit their future funding. They were vociferous in their criticism and, in the early years, energetic in their lobbying and attempts to dissuade our supporters.

We had to work hard to build relationships within these organisations. We also understood the constraints these larger national bodies face. To ensure their own survival they are often forced to raise money based on stories of community or individual deficit and they must then deliver programmes in traditional ways. In Loops we were able to share the funds we had raised with voluntary organisations, thus enabling those who wanted to collaborate with us to become part of our new way of working. In other sectors – employment, for example – we found the voluntary sector eager to collaborate.

Challenge in other instances was less surprising. In Life we asked all existing workers to stop what they were doing and stand back: an implicit criticism. Later on, as increasing numbers of families wanted to participate in the programme, we looked for further resources, which meant we encroached on the work of other agencies. And then, based on our success, we were invited to expand into other locations around the country. At each stage of this process we encountered opposition. With Life, as with all the experiments in this book, we attempted a double task: to change lives and to change systems.4 It was only to be expected that not everyone would be happy.

Jealousy was the first sign. The original Life team faced suspicion and envy from their peers. More serious was the initial reluctance of some other services to cooperate. After one particularly tough day, a Life team leader called me. Two small and previously excluded children were ready for school, as a result of intensive Life work. They had new uniforms, they were eager and their parents were organised. But when the head teacher heard that the children were at her school gates, she refused them entry. The family was notorious and the head had her school’s ranking in the league tables, as well as the other parents, to consider. The children had gone home in tears, their trust shattered. The Life team leader was exasperated and angry. This particular problem was resolved by the intervention of a city leader, who picked up the phone to the head teacher.

Transition involves protecting the work long enough for change to take root. Leaders in Swindon actively worked with us to create this space. They patiently invested time in convincing their peers as to the merits of a new way of working, and when conflicts arose they stepped forward. These leaders also invested time and money in supporting the Life team to remain open and courageous in the face of obstacles.

Success leads to further challenges. As the number of families ready to participate in the programme grew we looked for ways to build a second Life team. The data showed that some services that focused on managing risky and so-called anti-social behaviours now had much lighter caseloads. In the instance of one service, no referrals had been made in an eighteen-month period. We discussed transition: could we incorporate some members of their team and elements of their budget into an expanded Life offering? The leaders of these services nodded, but they were noncommittal and behind the scenes they started to mobilise. A leading local figure who had staked his reputation on a youth enforcement programme was persuaded to lead the fightback. Even though we had evidence – cost savings and an early positive and independent evaluation of the Life programme – this can be easily pushed to one side when the system decides to resist.

New work is ‘allowed’ while the numbers are small and we appear to be amateurs. Innovation that does not encroach on the existing system and can be contained as an interesting pilot, or published as an inspirational case study, is usually celebrated. In the beginning, everyone involved is patted on the head, invited to talk about the work in important places and roundly praised. Later, as the work becomes more successful and therefore more challenging, the system reasserts itself. This was a process experienced by Life, but also by Circle, Backr and Loops.

This process is usually subtle. It is not my experience that anyone explicitly criticises the work. It is more usual that whispered conversations happen in corridors, and very often the issue is personalised. Grappling with these challenges requires sensitivity – after all, we are all learning and we have not got everything right. We have to work continually to build stronger alliances and to keep all sides connected to the wider purpose of the work.

In the case of Life, the skills and commitment of leaders in social services, and of Rod Bluh, the Swindon council leader, ensured we found a way around early challenges. Life grew and stories about the families spread rapidly. In 2010 the Life hut was visited by David Cameron and his Minister for Communities and Local Government, Eric Pickles. They met with families, including Ella’s, who told them powerful stories of transformation. On the spot, there in the Life hut, the Prime Minister said that our approach must be replicated nationally.

Civil servants from the Cabinet Office were dispatched to our small and now even more crowded one-room office in London. These officials arrived with an idea. They would incentivise others to copy Life by providing money to organisations that could compete to do the work and they would make financial rewards to each local authority for the families they ‘turned around’. But Life is about how we can grow capabilities even in the most difficult of circumstances and how relationships between people can unlock the resources that already exist within homes, communities and services. We tried in vain to explain that more money was not needed, nor were new professionals required. What was needed was permission to free those at the front line to work in new ways – ways in which they want to work.

Nothing about this story resonated with the civil servants. These were likeable people, good friends, mothers, brothers and neighbours. But their professional personas and experience had trained them to see things from a different perspective. They were experts in creating markets and these concepts framed their analytic tools and their sense of the possible. They could not see the differences we tried to articulate. An approach based on horizontal relationships and a shift in power towards the families was translated back into a linear programme with outputs that could be measured and controlled. Financial incentives are a modern version of command and control. Local leaders who took part would be rewarded with pocket money, like children.

We faced a challenge we were not able to overcome: we could not persuade central government to think differently. In 2011 the Troubled Families Unit was formed, with a ‘war chest’ of £448 million to reward local authorities who hit targets under a payment-by-results system. The Troubled Families agenda did not spread our approach as intended. Instead, it derailed Life and the deeper changes many had started. Most local authorities found it wiser to fold their work into the government’s programme and sit it out until the attention and the money moved elsewhere.

Troubled Families, like many government programmes, blew through like the hot winds of a desert storm, and once it had passed the families and those on the front line dusted themselves down and started again. In Swindon, the Life team found the politically expedient definition of ‘troubled’ did not actually fit the families that had been drawn to Life with the most complex problems. ‘We know [the Troubled Families referrals] were not the most needy families. It was a numbers game and it took us somewhere else – we had no choice – so we didn’t continue with the Life families,’ one senior leader explained to me. However, a strong sense of purpose and good leadership ensured the original Life team remained intact and, once evaluations showed the failure of the Troubled Families approach, they turned back to the real work.