Scaling Character: what the 19th-century got right

And other things I found on the net this week

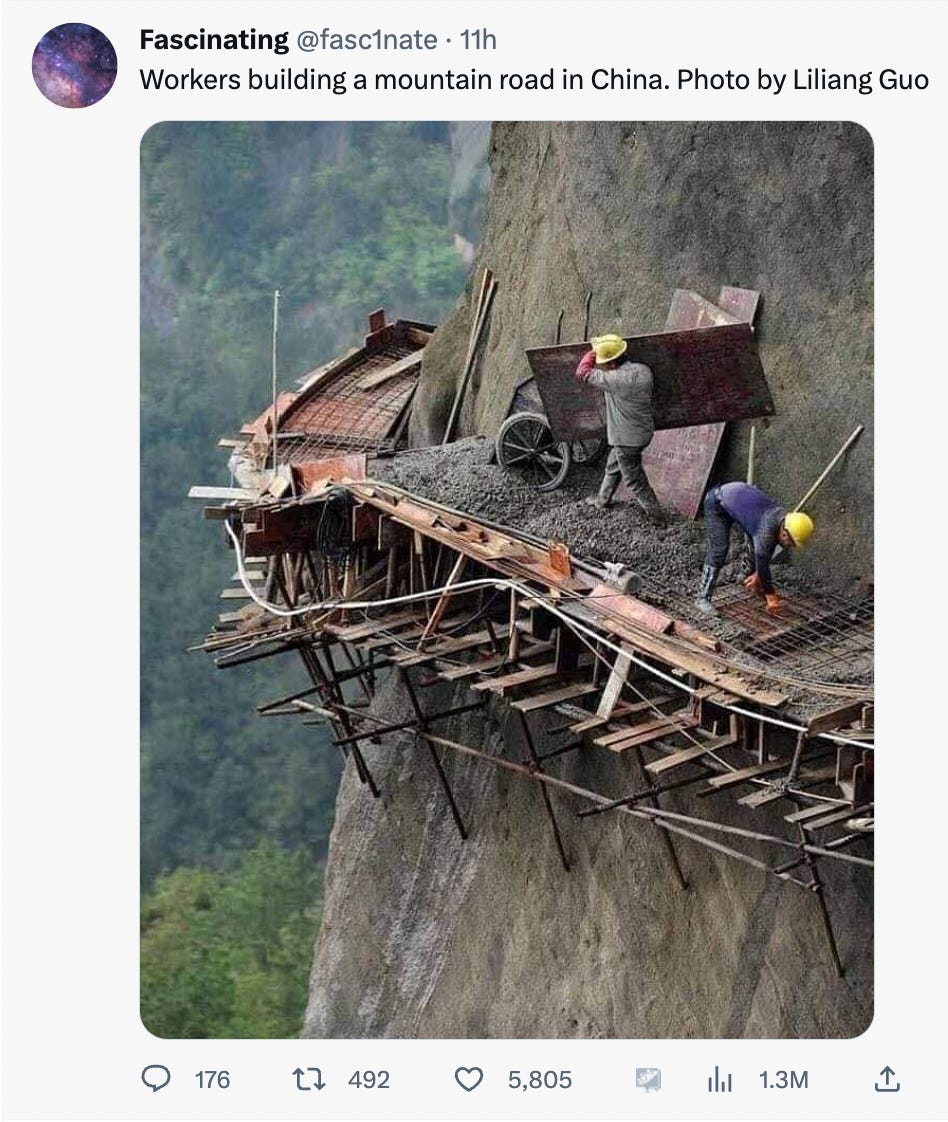

Apologies to all that Twitter has had a fight with Substack which means that tweets can’t be embedded in Substack. A great pity as they were a fun bit of colour and movement. If you see the odd ‘simulated’ tweet, I’ve gone to the trouble of simulating it, copying its text and its visuals independently.

Scaling Character: what the 19th-century got right

This is the best, most consequential essay I’ve read for a while.

[American] institution builders [of the mid 19th-century] embodied a type of excellence that foreign observers of their era described as characteristically American. The jurist Francis Lieber, who emigrated to the United States in 1827, credited this excellence to the fact that America had not “create[d] or tolerate[d] a vast hierarchy of officers, forming a class of mandarins for themselves.” A nation governed by a centralized mandarinate “can summon great strength upon certain occasions, as all [centralized systems] can; but it is no school of strength or character.”

But less than a century after the Civil War, American life did become dominated by centralized and professionally managed bureaucracies. The two world wars only served to entrench this way of life in business and politics. The population, in response, became increasingly conditioned to lobbying for centralized decisions instead of self-organizing. Those who introduced managerial bureaucracy to American life understood the “great strength” bureaucratic tools would grant them. But these tools destroyed the conditions that made them so adept at institution building in the first place. The first instinct of the nineteenth-century American was to ask, “How can we make this happen?” Those raised inside the bureaucratic maze have been trained to ask a different question: “how do I get management to take my side?”…

[T]he primary ideal enshrined and ritualized as the mark of manhood was “publick usefuleness,” similar, if not quite identical, to the classical concept of virtus. American civilization was built not by rugged individuals but by rugged communities. Manhood was understood as the leadership of and service to these communities. Three virtues in particular made this culture operate effectively and distinguished it from modern managerialism.

First, institutions cultivated a sense of public kinship and brotherhood, sometimes formalized by sacred oaths. … This required their culture to have a functional role for solemnity and seriousness. When irreverence becomes a universal norm, attempts at seriousness degenerate into performative role-play. … The second of its virtues was a strict code of formality and procedure, adhered to by members of all kinds of institutions. While modern institutions have plenty of procedure, the adherence and care given to general procedural norms even in small local affairs created a culture in which the culture of ownership of institutions was widely shared, not centralized.

The third virtue was … an embrace of functional hierarchy that allowed local initiatives to scale up …. The identification of “human scale” with smallness or localism was a false conflation. The reality proved by the nineteenth-century experience is that neither hierarchy nor scale is inherently opposed to agency. Many of the postbellum institutions that dominated American life operated on a national scale, occasionally mobilizing millions of people for their causes. However, the lodge and chapter-based structure of these institutions ensured those local leaders had wide latitude of action inside their own locality. … These chapters not only served as vehicles of self-rule at the lower level but also prepared leaders for successful decision-making at higher levels of a hierarchy. … Absent such training, leadership does in fact become the impenetrable closed circle that disturbed the advocates of “human scale.” Centralization, not hierarchy, caused the demise of local dynamism.

A very strange story about a hermit

Knight was finally arrested, after 27 years of complete isolation, while stealing food at a lakeside summer camp. He was charged with burglary and theft, and taken to the local jail. His arrest caused an enormous commotion – letters and visitors arrived at the jail, and approximately 500 journalists requested an interview. A documentary film team showed up. A woman proposed marriage.

Everyone wanted to know what the hermit would say. What insights had he gained while he was alone? What advice did he have for the rest of us? People have been approaching hermits with similar requests for thousands of years, eager to consult with someone whose life has been so radically different to their own.

Profound truths, or at least those that make sense of the seeming randomness of life, are difficult to find. Thoreau wrote that he had reduced his existence to its basic elements so that he could “live deep and suck out all the marrow of life”.

Knight did, eventually permit one journalist to meet him, and over the course of nine one-hour visits in the jail, the hermit shared his life story – about how he was able to survive, and what it felt like to live alone for so long.

Amazing interview of Jonathan Swift via ChatGPT

Heartache: A small story about a small love

From Misha’s Kvetch

“the child is small, and its world is small, and its rocking-horse stands as many hands high, according to scale, as a big-boned Irish hunter.”

Great Expectations, Charles Dickens

My son had his heart broken for the first time. He is six.

He went on a cruise with his abuelitos and two younger sisters. There the kids gathered around a jacuzzi — the pool was not heated you see, and kids love few things in this world more than warm water.

There stood a girl dominating the arena. Splashing the other kids, they fled the milieu. My boy jumped in and splashed back. They splashed and jumped and fell and laughed. Before long they were scampering hand-in-hand to the waterslides.

For the rest of the morning they were inseparable. Running on-deck. Sliding down waterslides. Warming on a sunbed, giggling.

When the girl’s grandma came to collect her away my boy was ready with a cunning plan. He asked for their room number.

With a tip from his abuelo, he figured out the room phones. One of those fixed line phones that are quickly following the rotary phone into antiquity. He dialed the girl’s room. Hello? Do you remember me? We played outside. Let’s meet at the waterslides. And so they spoke and they played. The six year old boy and the seven year old girl. All that day and then the next.

His sister — my eldest daughter now five— was not pleased. Where my son is a gentle if rough boy with an emotional — sulky, really — temperament, my daughter is a ballerina with sharp eyes. Who was this girl who had taken her brother from him? And who did her brother think he was? She was the only game in town. And so my daughter took this girl by the hand and scrammed.

This time it was the girls who ran hand-in-hand and embraced and giggled words of affection to one another. And jeered at my boy, who stood aside — rebuffed, confused and angry. Hurt.

I suppose the same impulse to wound that grabbed his sister so grabbed this girl, as they showered each other in affection and ignored, jeered, and expelled him.

She stole her, my son would later tell me about his sister.

Look at what they did to my beautiful boy. How they put boys and girls in the same class is beyond me. Like lambs to the lions.

My father-in-law chuckled and smiled as he told me. But with at least as much heartache as anything else. It was no small moment for my boy. This rocking-horse was a big-boned Irish hunter to him. And in the boy’s small heartbreak, I think my father-in-law and I saw something similar: nothing less than the first tears in the fabric of a man’s soul. We have our patches and stitches — he of his 60-odd years, me of my 30-odd. And now my boy tasted a small measure of what lay ahead.

Hi ho, hi ho, it’s off to work we go

Taking Adam Smith seriously

Conservative member for Hereford and now a fish out of water in the dumbified Conservative Party of the United Kingdom, has published books on his two British heroes Adam Smith and Edmund Burke and in this essay in the FT summarises what the modern world should take from Smith.

First, we need to recognise that The Wealth of Nations is a work of genius not merely because it sets out many of the central intellectual tools of political economy … but because Smith is the first person to put markets at the centre of economics itself. Smith is thus the hinge of our economic modernity, just as Burke, with his theory of political parties and representative government, is the hinge of our political modernity.

But, second, markets for Smith are very different to those of economists today. They are not the disembodied mathematical constructs of modern economics and policymaking, and his view of individuals is not that of a desiccated economic atomism. Rather — recalling his insights about language and ethics — markets are living institutions embedded in specific cultures and mediated by social norms and trust. They shape and are shaped by their participants, in a dynamic and evolving way. They often have common features, but they are as different from one another as individual humans are: markets for land and labour and capital, asset markets from product markets and all the innumerable rest of them. Yes, markets typically generate economic value, and they are unmatched in their ability to allocate goods and services and encourage innovation and technological improvement.

But, third, what matters is not the largely empty rhetoric of “free markets”, but the reality of effective competition. And effective competition requires mechanisms that force companies to internalise their own costs and not push them on to others, that bear down on crony capitalism, rent extraction, “insider” vs “outsider” asymmetries of information and power, and political lobbying. Fourth, markets constitute a socially constructed and evolving order that exists and must exist not by divine right but because it serves the public good. It follows from this that the modern doctrine of market failure, which derives from academic models assuming perfect competition, needs to be expanded and supplemented.

The truth is that outside academic models there are few if any genuinely free markets, and the imagined benefits of perfect markets disappear once any imperfections are allowed. Instead, policymakers need to start by asking two much simpler questions: What is this specific market for? How is it actually working? Fifth, for the same reason, both individual markets and the market order itself rely on the state. While political intervention can destroy market functioning, it can also enable it. But markets are not inviolable, and they derive their reason for being not from any supposed sanctity of capitalism itself, but from their place within modern commercial society. Ultimately, especially within democracies, it falls to the state to underwrite that legitimacy. And if the preservation of the freedoms, trust and order that make up modern commercial society requires the periodic reform of capitalism, then reform it we must.

Delicious colours

Elbridge Colby Wants to Finish What Donald Trump Started

When Ron DeSantis in March dismissed Russia’s war on Ukraine as a mere “territorial dispute” and argued for a greater focus on the China threat, you’d forgive Colby if he did a victory dance. … [I]t was the latest sign that in the ongoing battle for the future of the Republican Party, Colby’s views are advancing with lightning speed.