The Guru, the Bagman and the Sceptic: A story of quackery and care

I talk with Seamus O'Mahony who has written a unique and marvellous book. It's about the origins of psychoanalysis, and it's the first serious history I've ever read that is written as a comedy! O'Mahony brings this off brilliantly, and it enables him to skewer the madness and quackery of the early psychoanalysts without any self-righteousness. In the background of all this is O'Mahony's experience as a (now retired) doctor, older and wiser than when he began.

The hero of the book is the now obscure Wilfred Trotter, a man of prodigious natural gifts both intellectual and practical. He baled out of psychoanalysis early and went onto become the greatest English surgeon of his generation while remaining a model of modesty and self-restraint, unlike the other two protagonists of the story. In the end, he stands for the centrality and the indispensability of care in medicine. And yet, as O'Mahony laments, care receives short shrift in modern medicine.

All up a marvellous conversation. Even my wife agrees with this assessment, and she is not at all like me. She advises large doses of salt when dealing with most things I think or say. However she was fascinated in the book from having listened to this conversation and is now greatly enjoying the book. This is a testament to its breadth of appeal.

If you prefer audio only, you can find it here. If you are short of time and want to dive into the meat of our conversation, start from the 16 minute timestamp. And check out the extract from one of his earlier books which is the last item in this newsletter.

It wouldn’t be a newsletter from me if it didn’t have weird medieval guys in it, and these weird medieval guys tell us something of enduring importance. Back then, when important people ran off at the mouth — a practice now known as ‘bullshitting’ — green frogs started coming out of their mouths. This was uncomfortable and embarrassing for them, and everyone could tell they were bullshitting. Thomas Aquinas didn’t write a treatise about it, but then again he didn’t need to. Everyone knew: Frogs => Bullshitting.

Today it’s much harder. And that’s even with books being published every month or so on bullshitting.

Democracy: doing it for ourselves — audio

I posted the video of my talk in London on the 15th last week but didn’t get time to do an audio file, which can now be accessed here. And thanks Rory — he was there! I’ve also published a slightly more navigable video of the event here — where you can read an AI generated transcript, identify things you’re interested in and click through to the relevant part of the video.

It’s capitalism stupid

A column by Katharina Pistor exploring three very different situations in which the logic of capitalism asserts itself over

Philanthropic effort (Microsoft ends up calling the tune re OpenAI)

‘Sustainable investment strategies’ producing a ‘tectonic shift’ in sustainability (until they don’t) and

Central banking which enables banks to make out like bandits with all their profits and bales them out when they get into trouble.

In 2022, Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, predicted a “tectonic shift” toward sustainable investment strategies. But he soon changed his tune. Having since downgraded climate change from an investment strategy to a mere risk factor, BlackRock now prides itself on ensuring “corporate sustainability.” If the board of a non-profit with a firm commitment (in writing) to AI safety could not protect the world from its own CEO, we should not bet on the CEO of a for-profit asset manager to save us from climate change.

Likewise, consider the even longer-running saga of broken promises for the sake of profits in private money-creation. Money is all about credit, but there is a difference between mutualized credit, or state money, and privatized credit, or private money. Most money in circulation is private money, which includes bank deposits, credit cards, and much more. Private money owes its success to state money. Without the state’s willingness to maintain central banks to ensure the stability of financial markets, those markets and the intermediaries populating them would fail frequently, bringing the real economy down with them. States and banks are the oldest example of “public-private partnerships,” promising to benefit bankers and society alike.

But winners like to take all, and banks are no exception. They have been granted the enormous privilege of running the money mint, with the state backing the system in times of crisis. As other intermediaries have figured out how to join the party, few states have been willing to reassert control, lest they trigger capital flight. As a result, the financial system has grown so large that no central bank will be able to resist the call for yet another bailout the next time a crisis looms. The party always continues because sovereigns dance to capital’s tune, not the other way around.

It is no surprise that OpenAI failed to stay on mission. If states cannot protect their citizens from the depredations of capital, a small non-profit with a handful of well-intentioned board members never stood a chance.

From a good friend and subscriber

I went up to the MET tday but it was closed so I walked to the Guggenheim. I read the descriptions of the art.

Gruen captures the otherness of the coloured in American life and their invisibility to the white gaze by minimizing the use of lighter shades in his palette to emphasize their determination not to be defined by historical and cultural stereotypes while at the same time using the darkeness of tone to show their complexity as individuals and the ambiguity of their emotional existence as simultaneously being objectified and acting on the world to reshape . . .

After about 15 minutes I felt like voting for Donald Trump but managed to save my soul by fleeing back out into the cold.

Chris Morris: satire in accelerationist times

I met Chris briefly because he came to my talk on Democracy. I had been told he’s Britain’s greatest satirist. I’m sorry I didn’t get more time to talk with him as, judging by this interview, he’s an unusually intelligent, serious guy.

Sam Altman: the conspiracy theory

Reports are now surfacing that Altman had announced that he was on the brink of achieving a significant AI breakthrough only the day before he was fired. A letter was sent to the Board advising them that this tech discovery — an algorithm known as Q* (pronounced Q-Star) — could “threaten humanity”. The algorithm was deemed to be a breakthrough in the startup’s search for superintelligence, also known as artificial general intelligence (AGI), a system smarter than humans.

Altman’s dream was to then marry AGI with an integrated supply chain of AI chips, AI phones, AI robotics, and the world’s largest collections of data and LLMs (large language models). Its working name is Tigris.

To achieve this, Altman would need vast computing resources and funding. Perhaps that is why reports suggest he has been talking to Jony Ive, the designer behind the iPhone, Softbank, and Cerebras — which now makes the fastest AI chips in the world. Cerebras chips are big. The size of a dinner plate and more powerful than any traditional chips.They also have Swarm X software, which allows them to knit together into clusters that create a computational fabric that can handle the massive volume of data needed to build better AI. …

By this measure, Altman is a mad scientist who will put us all at risk to achieve a historic breakthrough. Hence the letter to the board of OpenAI by some staff, along with others keen for the world to take note that the huge staff attrition rate at OpenAI was not due to “bad culture fits” — rather, this was due to “a disturbing pattern of deceit and manipulation”, “self deception” and the “insatiable pursuit of achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI)”. …

You can understand why the OpenAI Board might have become uneasy when they realised that Altman was racing around the Middle East and Asia trying to raise billions for this vision. But, as Bloomberg wrote, “these are not “side ventures”, they are “core ventures”. This is about redefining the cutting-edge of chip design, data collection and storage, computational power, and the interface between AI and physical robotics. …

Two days after Xi and Biden met on November 15 and agreed to play nice, Altman was fired. The Daily Dot suggests that Altman was terminated because Xi hinted to Biden that Altman’s OpenAI was surreptitiously involved in a data-gathering deal with a firm called D2 (Double Dragon), which some thought to be a Chinese Cyber Army Group. David Covucci reported, “This D2 group has the largest and biggest crawling/indexing/ scanning capacity in the world 10 times more than Alphabet Inc (Google), hence the deal so Open AI could get their hands on vast quantities of data for training after exhausting their other options.”

There is something deeper happening here. China has already forged an AGI path of its own. They are avoiding generative AI in favour of cognitive AI. They want it to think independently of prompts. China is already giving AI control over satellites and weaponised drones. No doubt, Altman would love to work with that capability and the Chinese would love to work with him.

Could that be why Larry Summers, the Former Secretary of the Treasury with connections to US politics and business, also ended up on the new OpenAI Board? Perhaps the US Government realised they could not stop Altman but might claim a seat at his table?

What does all this mean for us? Experts like Altman say they are designing AI to do good. But AI designers disagree about what constitutes “good”. It is clear this arms race could have civilisational consequences.

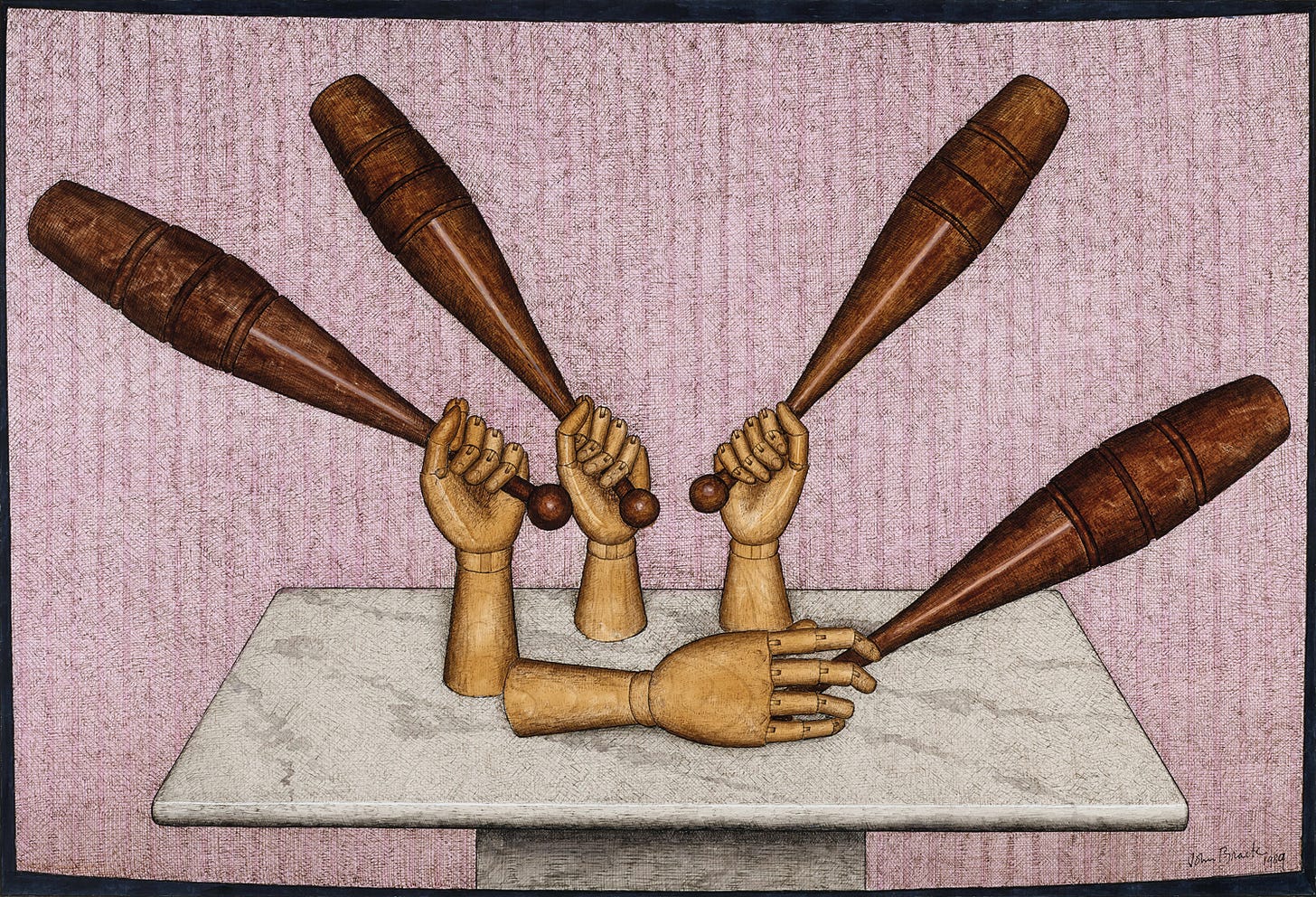

The prevailing idea is that humankind invents false binaries that separate people under different designations without realising that the world that they are inhabiting is itself tottering on the brink of collapse and that these meaningless divisions only contribute to the inevitability of this collapse.

[Checks out. Ed}

From Sasha Grishin’s accompanying essay on the subject for the auction catalogue.

Steven Pinker keeps himself in check

Just as he backed out of his position in the University of Austin, Texas on the grounds that rounding up some dissidents is no way to revive the quest for a truly liberal education (which has been pushing up the daisies for a generation or so by now), he is likewise a fan of Effective Altruism while deploring its cultishness. Couldn’t agree more.

You are a (partial) Utilitarian, whether you realise it or not.

A short defence of a good idea from Henry Oliver

With the news that OpenAI was nearly ruined by the actions of a group of Effective Altruists, the scandal of Sam Bankman-Fried covering-up and justifying fraud in the name of Effective Altruism, utilitarianism is once again being described as heartless rationalism, [in which] the ends to justify the means. … [B]ut utilitarianism is bigger than Effective Altruism. It’s an important set of ideas that underpin the modern world.

Here are some of the ideas … which have their origins in … utilitarian thinking:

Women should have the vote.

The way we treat animals in farms is wrong and we ought to either raise welfare standards significantly or become vegetarians and vegans.

Government spending policies should be tested with cost-benefit analysis, to make sure that we are getting good value for money.

Government policy should be assessed on its outcomes, not intentions.

Legal reform so that punishments are effective and humane.

Charity should be effective. …

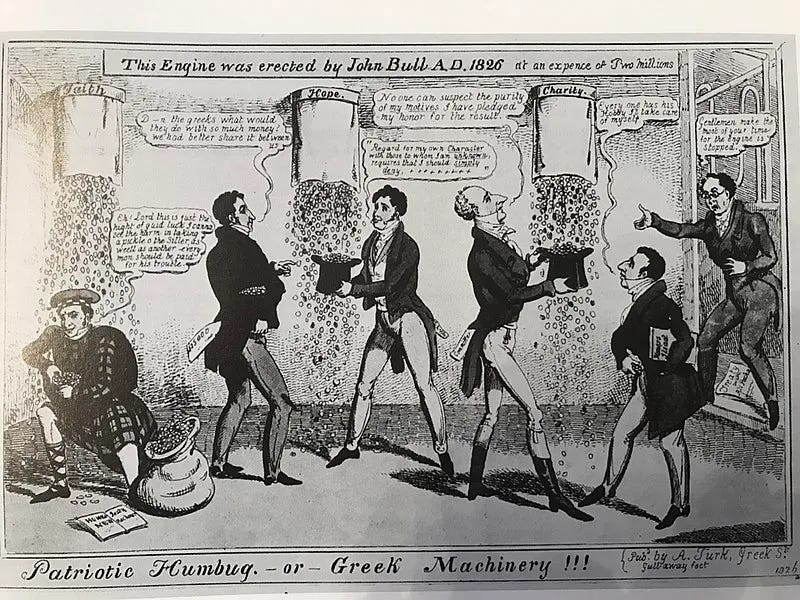

The recent scandals will not be the end of utilitarianism, though it might be the start of a decline in Effective Altruism. Many Benthamites were revealed to have been involved in the speculations and pocket-lining of the 1825 financial crisis, which damaged their reputation for high-mindedness and ethical thinking. But that wasn't the end of Bentham, or utilitarianism. And it isn’t now. Effective Altruism is still a good idea, based on important principles that have changed the world for the better.

An old friend sent me this — it’s cute

And the YouTube algorithm being what it is, it immediately served up this — which I recommend.

Luca Belgiorno Nettis thinks a citizen assembly could have helped with the voice

I expect he’s right and, like him, I was on the blower to the great and the good suggesting it when there was still time. My gob was smacked however when talking with a leader of the Yes case who argued that the indigenous community’s view was that the citizen assembly had already occurred and it had made the Uluru Statement. I said that if that was to be regarded as a citizen assembly it represented 3 percent of the citizenry and that I thought they were seeking the buy-in of the other 97 percent. Silly me.

Anyway, I’m sure a citizen assembly would have made the process less adversarial, but I expect the No case would have had little trouble whipping up enough adversarialism to have prevented the citizen assembly from saving the day for the Yes case. It’s hard to see it being worth a 20% swing to Yes.

Here’s Luca:

The divisions surrounding the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament had as much to do with referendum process as anything else. The Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters missed a golden opportunity earlier this year when, in proposing a Bill to reform the referendum process, it ignored the advice of several prominent political scientists to convene a Citizens’ Assembly.

The Irish regard the use of these Assemblies as a way of resolving difficult political issues. In June this year, I visited Dublin along with several others to observe their sixth Assembly — this time on drug use. Previously, in 2018, many thought the Irish could never decriminalise abortion in their deeply religious country. However, following the recommendations of an Assembly, they voted to do so.

The Irish have developed a process by placing citizens centre stage, and thus are able to defuse the adversarial nature of politics-as-usual. The late Australian political scientist, Ian Marsh, said: “Political incentives undercut bipartisanship. We need a formal political structure to create a public conversation, but the system lacks this.” Ireland has this structure now, and other countries are following suit. Canada, Germany, the UK, France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium are all exploring the same core idea: the bona fide involvement of people in democracy.

In Australia we default to “expert panels” instead — such as Royal Commissions and select Committees. When it comes to specific referenda questions, there’s the Constitutional Convention approach, as we had for the Republic vote twenty-four years ago. The Voice may have benefited from such a Convention this time around, but that process still risks getting hijacked by partisan interests, as happened in 1999.

Consider how radical the role of a legal jury is sitting alongside the professionalism of the Courts. Nicholas Gruen has made the case in the following terms:

There are no inducements of any worldly kind — including career inducements — on offer to influence jurors. The citizens remain untouched by Teflon-coated principles that travel within more rigid bureaucratic structures — principles such as the need for decisions to be “accountable”, “transparent”, and “merit-based”. Jurors are not chosen on merit; their conduct is not transparent, and they’re accountable only to themselves.

Unsupervised by their putative betters, the evidence is that jurors rise to the occasion. They’ve retained their communities’ trust, even in the face of disputed judgements. In law, juries make excellent partners to officialdom, marrying the life world and naïve good intentions of everyday people to the careerism and professionalism of the Judiciary.

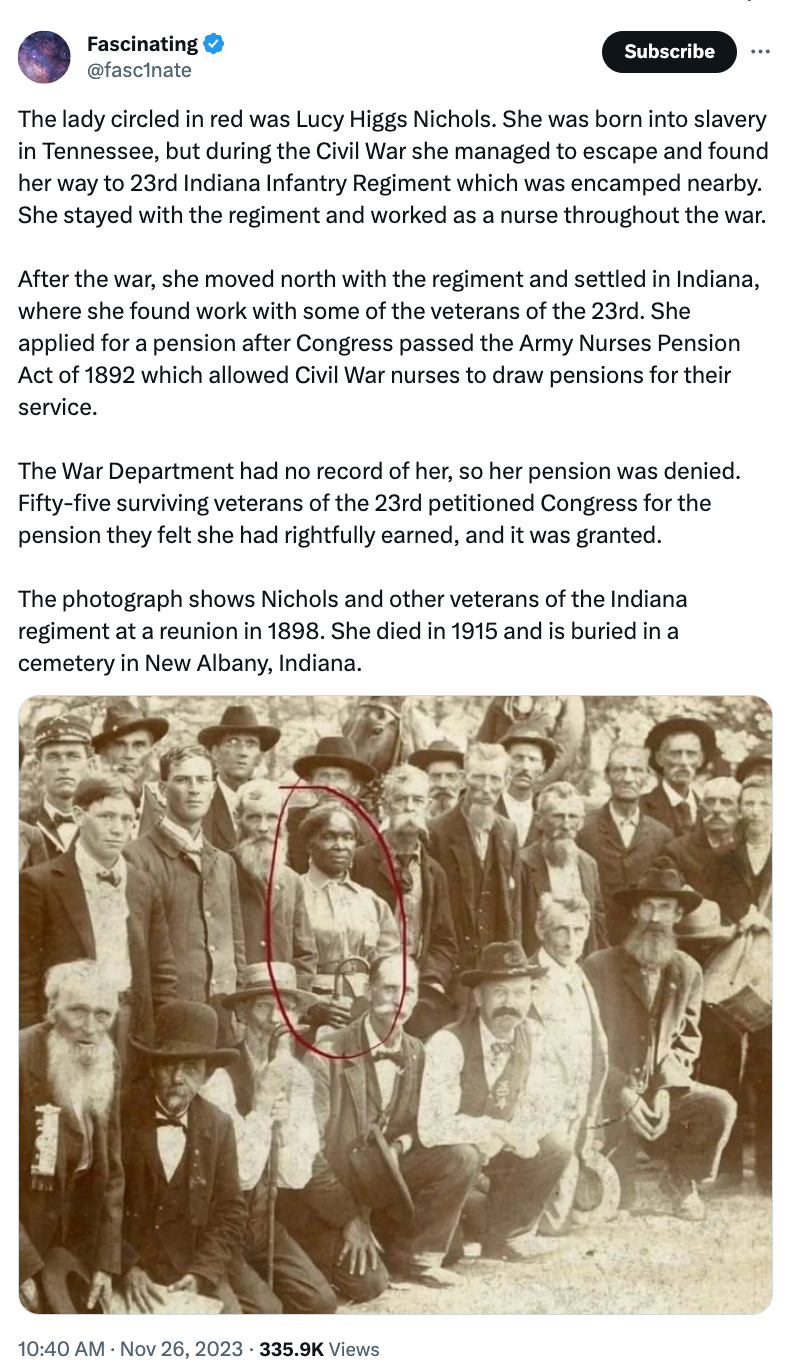

A beautiful story

How to write a great essay in intellectual history

This is from this website, but it didn’t come out when I put in the url — I got it from Brad’s site.

Openings are crucial. Plunge in with something substantive about the theory and text in question. Never begin with potted biography or history, or generalities about the meaning of life.

Get the balance right between exposition and criticism. Some people are over-eager to show their critical powers: avoid hatchet jobs; it shows lack of sympathetic understanding: your author may be wrong but he or she is not stupid. Other people, by contrast, are not eager enough to show their critical powers: avoid tame plot summaries which just summarise the contents of the text.

Impose a conceptual framework on your essay. Give clear direction to the argument, a sense of an unfolding of the implications of your key claims. Provide signposts to the reader.

Most political philosophers address not just politics narrowly conceived, but also ethics. epistemology, ontology, or theology. Show how these interconnect.

You cannot cover everything in an essay, but try to make allusions to the wider hinterland of your knowledge. The specific question should be specifically answered, but should not induce tunnel-vision.

Quote from the text, using brief phrases, integrated with your own sentences. Avoid the most boringly famous quotations. Avoid large chunks of displayed quotation. Cite specific chapters or sections of the text. Acknowledge your sources, both primary and secondary.

Get the balance right between text and context. The essay should be structured as an account of a theory and a text, but along the way you should allude to influences and circumstances and traditions of a political, intellectual, or biographical kind. Avoid large chunks of scene-setting; or, on the other hand, abstracted theory without a sense of time and place.

Texts have not only arguments but a rhetoric and style. Convey the flavour of a particular mental world by referring to the text's images, metaphors, illustrations, genres, and intellectual resources—scriptural, classical, or whatever.

Get the balance right between primary and secondary sources. Lean heavily toward the primary text. Never merely parade the views of others: show that you have read the text for yourself. Sometimes, however, you will need to refer to specific controversies or interpretations. Note that the secondary literature is often written by philosophers and political scientists as well as historians: they have different approaches.

The texts are not isolated islands of thought, not distant catalogues of arbitrary opinions. They take stands on issues which are continuous with modern political philosophy. Make connections and contrasts with other texts (and with present-day issues). But do this briefly and carefully: it is hard to do.

Amazing murmuration

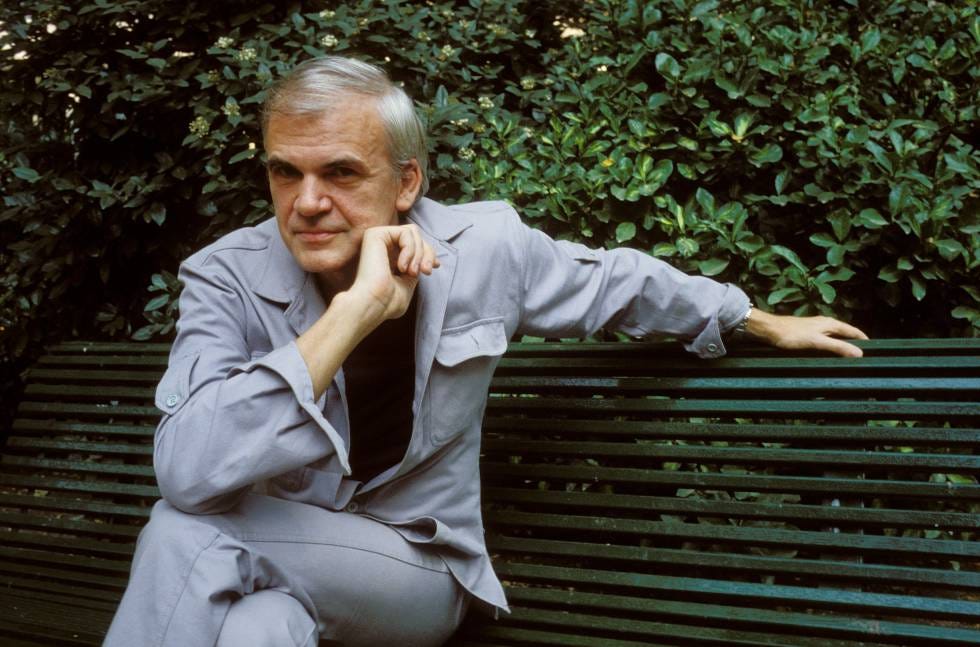

Milan Kundera

Critical attempts to save the playful Kundera in his mature works tend to misfire. At least one critic (Jan Čulík) has ingeniously suggested that the appearance of knowingness is a deliberate ploy, a playful illusion. Kundera is said to engage with the reader in a series of mystifications ultimately revealed in that characters and narrators constantly contradict themselves and one another. It is true that the idea of Kundera’s writing as a sustained exercise in mystification grows in plausibility the more one delves into the detail. An in-depth look at Kundera’s use of literary and philosophical references often reveals they do not bear closer scrutiny. Setting aside his superficial forays into philosophy, it is his frequent (mis)use of literary classics that fascinates the most. In Ignorance, Homer’s Odyssey is used to underline the central paradox of one’s ‘great return’ from exile: nobody at home asks about what you experienced while away. Nobody in Ithaca, the narrator tells us, cares to ask Odysseus about his adventures! And yet this is not true of The Odyssey. Penelope is keen to hear all about Odysseus’s struggles and Homer is at pains to stress that she does not fall asleep until Odysseus has finished his story. Clearly, Kundera needs the great classic to prop up his idea of great return but isn’t willing to engage with it when it undermines his idea.

Similarly, when in Immortality Kundera calls Don Quixote (first volume, chapter twenty-five) a prime example of Cervantes’s ridicule of the sentimental, self-centred lover uninterested in his beloved, he is being disingenuous. The chapter contains Don Quixote’s revelation of who his Dulcinea really is as well as an ingenious disquisition on the complex relationship between the ideal and the real. Don Quixote seems far from being a sentimental fool in his intimation that it is love itself that raises its object to the level of an ideal, and not the object’s embodiment of the ideal that necessitates love. That Kundera should elide this idea is not an accident. His own depictions of women entail a refusal to accept just the point Don Quixote is making, that it is love itself that makes the world beautiful, not the beauty of the world that must be demanded as a precondition for love. No wonder Kundera’s male characters and narrators are constantly disappointed by the gross failure of women to embody a demanding ideal of beauty. This failure in turn leads to a justified, indeed inevitable male (and sometimes female) ressentiment of the female body with its blemishes, from wrinkles to gaping mouths and vaginas, and even leaking innards. And when the ugly female body proves to be capable of provoking erotic desire even so, the resulting visions tip into misogyny.

The infamous episode in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (Part III Angels, pars 7 and 9) is a case in point. Kundera’s first-person narrator goes to meet the female magazine editor who has published his writing under a cover, and who is now under investigation by the secret police. Fear has loosened the young woman’s bowels. The narrator imagines her body as a cut-up, hung-up bovine carcass and finds her abject trips to the toilet so erotically arousing as to experience ‘a furious desire to rape her’. The animus behind the description shines through even more clearly when one learns from Novák that the episode is a close fictional rewriting of a real event. Novák managed to track down the editor who published Kundera’s horoscopes in the Mladý svět magazine in 1972, and to identify the only significant difference between the meeting that took place and Kundera’s fictional representation of it: the editor was not a woman, but a man called Petr Prouza. In Kundera’s imagination, however, bodily abjection is a fate worse than death reserved solely for women. …

The problem with any interpretation of Kundera as a master of mystification is not that it is untrue but that it threatens to undermine his trustworthiness. The positive reception he has been accorded in the West since the 1970s has stemmed mostly from straight readings of his works as hard-earned, unsparing wisdom figuratively reflecting the author’s exceptional experience (if not fate). Kundera’s ‘autobiographical’ style of narration creates the appearance of authenticity, an implied promise that his words are in earnest and to be trusted. This is why he has achieved the status of an influential political writer and commentator on the paradoxes of communism and other weighty matters, notwithstanding his insistence that to read his novels politically (or historically) is to misunderstand them. But if Kundera was always more of a player and consummate mythmaker than a truthteller or even a sage, where does this leave his serious readers?

Anti-semitism among Muslim school children

A section from ”Genocide or Holocaust Education: Exploring Different Australian Approaches for Muslim School Children”, 2015. With thanks to Suzanne Rutland for sending me her paper and to Henry Ergas for telling me about the study.

“Anti-Jewish Feelings of Muslim Children in Southwest Sydney Government Schools”

The narrative I present here is based on the teachers’ descriptions of their personal experiences and perceptions of their students’ attitudes towards Jews. The eight teachers consistently testified to a pattern of anti-Semitic attitudes and beliefs among their Muslim students. The various misconceptions of Jews that Muslim children hold are illustrated by a single question that a Muslim student put to a Jewish professional I interviewed: “Yes, Miss: Why do you Jews hate us, want to take over our land, and take over the world?” In contrast, Kabir (2008, 2011) did not report any of these responses in her studies of attitudes of Muslim youths in Australian schools. This may be because she was focusing on how the students acculturate into Australian society, and she does not seem to have probed her student interviewees about their attitudes toward Jews or the Holocaust, or other issues such as whether they watched Al Jazeera or which websites they accessed. She also drew her findings from a comparatively small sample of students from only three schools. In contrast, the teachers I interviewed for this study represented a wider range of government schools. They did not methodically investigate anti-Semitic attitudes, but were reporting on comments that their students made spontaneously in their presence in the classroom and on the playground.

In the interviews, the teachers said that the Muslim students often expressed an admiration for Nazism and Hitler; some drew swastikas on their desks and had posters of Hitler. They also made statements in class such as “Hitler did not go far enough”. Many also believe that the Zionists cooperated with Hitler during the Holocaust in order to create a pretext to take Palestine from the Arabs.

According to these teachers, the students have also been indoctrinated with myths and misconceptions about Jews, including traditional world conspiracy theories propagated by the well-known forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (Litvak and Webman 2009, pp. 6 –7). One student told a teacher that she had watched another girl on the train taking her mobile phone apart. When the teacher asked the student why her friend did this, she said, “Jews are able to listen in because they own all the communication systems”. One teacher found that students had pictures of dead babies supposedly killed by Israeli soldiers that had been distributed at the local mosque. The students could not understand why it was not appropriate to have such pictures.

A number of teachers noted that many Muslim students believed the conspiracy theory that Jews were responsible for the terror attacks on September 11, 2001. One teacher noted,

Once [the students] believe something, they are not going to hear another point of view. This is perpetuated through their homes and I wonder if also from their media. They and their parents would maintain that [Sept. 11] was a Jewish holiday—it was planned—they rang each other up on the morning saying, “Stay home”.

Jewish teachers in these schools have experienced harassment from their Muslim students; one Jewish teacher had to request a transfer on compassionate grounds following ongoing harassment from the students. Teachers who are Jewish in schools with a high concentration of Muslim Arabic pupils have been counseled not to reveal that they are Jewish. One said, “I am not able to come out—I want my students to know I am a person like anyone else, just flesh and blood”. Another, almost in tears, said this: “I am terrified that the students will find out that I am Jewish. I am very ashamed to say this”. Another teacher who is not Jewish, but who is interested in Judaism, mentioned this interest to the principal of the school who was supportive but warned the teacher not to reveal this interest to the students.

In these interviews, the teachers said that most of the prejudicial views came from the students’ homes; students reported that this is what their parents have told them. The students experience a sense of disconnection when their teachers tell them something different about the Jewish people or the Holocaust from what they have learnt at home. In addition, outside authorities, including the religious leaders in the mosques, tend to undermine Western influences so that teachers in government schools often face serious discipline problems. As one teacher put it:

We [the teachers] have been called sharmuta—which means whore, prostitute in Arabic—we have made complaints.... The students are learning that there are no serious consequences for disrespect, for hatred, for racism, discrimination, verbal abuse, and even violence.

I know that in Syria, Lebanon, Sudan, Iraq, Kuwait, they do know how to respect authority figures and teachers and even women to a certain level within their own culture. They have been allowed to use our system and disregard it at the same time because there are no consequences for their behaviour.

Studies of Muslim children and the Australian school system have found that Muslim families have different expectations of schooling because they mainly come from authoritarian cultures where schools are teacher centred and based on rote learning, to the Australian schools which are student centred and encourage questioning and analysis (2001, pp. 122 –124, 199). In her study on educating Muslim children in Australia, Clyne (2001) noted that many Muslim parents blame their children’s low achievement levels on the “lack of discipline, differences in the teacher’s role and lack of structured teaching and learning” (p. 122). The few Jewish children in the government schools in the southwest of Sydney have also been targeted and some Jewish parents have had to remove their children and move to another area because of ongoing harassment.

Most teachers in southwestern Sydney believe that they need to focus on the anti-Muslim feelings that are prevalent in Australian society. The teachers I interviewed commented on the fact that, on the whole, other teachers in their schools were less concerned by the phenomenon of Muslim children’s hatred of Jews. One commented, “There has to be a wider appreciation that there is a problem of anti-Semitism in the Arab community…. It is a problem that needs to be tackled”.

This information from my interviews with teachers about Muslim children’s negative attitudes towards Jewish people was validated by a survey Jennifer Nayler (2009) conducted at a government high school in southwestern Sydney, where the majority of students are of Arabic-speaking backgrounds. She asked students if Muslims and Jews engaged in particular negative behaviors, as shown in Table 1. She found that far higher percentages held these beliefs about Jews than about Muslims.

Another study of anti-Semitism amongst Muslim youth, by Philip Mendes (2008), also supports these findings. However, Mendes argues that these sentiments “appear to be a form of male violence which is not mirrored by girls in the same cohort” (p. 2). My interviewees support Mendes’ contention that anti-Semitism was a source of amusement among the boys socialising in the playground. One teacher reported that the boys would download “beheadings and attacks against ‘infidels’ onto their mobile phones” and would then “swap and show them with their friends”. However, some of the teachers I interviewed teach at girls’ high schools, where anti-Semitic attitudes were also present. A study in Canberra (Ben-Moshe 2011) found that Jewish children experience racist taunts from children of both Christian and Muslim backgrounds. However, the one physical assault reported in that study occurred in an incident with a Muslim child in connection to the Middle East conflict. Ben-Moshe commented that “this supports the contention that antisemitism takes an additional and potentially more sinister and dangerous form in high school and in relation to Israel” (p. 15).

From my survey of teachers, it is clear that Muslim school students, both male and female, hold negative perceptions of Jews. Some express this by using hate language relating to Jews; their negative attitudes are consistent with their high regard for Nazism. If Australia is to remain an ethnically harmonious country, there is clearly a need to counter these negative stereotypes and to develop more accepting attitudes towards Jews amongst Muslim and Arabic-speaking students in Australia.

In the light of these findings, Suzanne Rutland argues that Holocaust education for Muslim high school students should begin with the more general concept of genocide, so that students can understand that negative stereotypes about any ethnic or religious group and lead to hatred and violence.

The full reference is: Rutland, Suzanne D., ‘Genocide or Holocaust Education: Exploring Different Australian Approaches for Muslim School Children’, in Gross, Zehavit and Stevick, E. Doyle (eds), As the Witnesses Fall Silent: 21st Century Holocaust Education in Curriculum, Policy and Practice, Geneva: Springer, 2015, pp.225-243.

(In case you needed to know).

Seamus O’Mahony on Medicine

An excerpt from one of O’Mahony’s earlier books which I’m reading now and highly recommend.

Chapter 6: How to Invent a Disease

The medical–industrial complex has undermined the integrity of evidence-based medicine. It has also subverted nosology (the classification of diseases) by the invention of pseudo-diseases to create new markets. A couple of years ago, I stumbled across a new pseudo-disease: ‘non-coeliac gluten sensitivity’. I was invited to give a talk at a conference for food scientists on gluten-free foods. I guessed that I was not their first choice. Although I had published several papers on coeliac disease during my research fellowship, I had written only sporadically on the subject since then; I was not regarded as a ‘key opinion leader’ in the field. I was asked to specifically address whether gluten sensitivity might be a contributory factor in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This is a common, often stress-related condition that causes a variety of symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bloating and diarrhoea. It is probably the most frequent diagnosis made at my outpatient clinic.

Coeliac disease is known to be caused by a reaction to gluten in genetically predisposed people, but now many others, who despite having negative tests (biopsy, blood antibodies) for coeliac disease, still believe their trouble is caused by gluten. This phenomenon has been given the label of ‘non-coeliac gluten sensitivity’. At the conference, an Italian doctor spoke enthusiastically about this new entity, which she claimed was very common and responsible for a variety of maladies, including IBS and chronic fatigue. I told the food scientists that I found little evidence that gluten sensitivity had any role in IBS, or indeed anything other than coeliac disease. I listened to several other talks, and was rather surprised that the main thrust of these lectures was commercial. A director from Bord Bia (the Irish Food Board) talked about the booming market in ‘free-from’ foods: not just gluten free, but lactose free, nut free, soya free, and so on. A marketing expert from the local University Business School gave advice on how to sell these products – he even used the word ‘semiotics’ when describing the packaging of gluten-free foods. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity may not be real, but many people at this conference clearly had invested in its existence. One speaker showed a slide documenting the exponential rise in journal publications on gluten sensitivity, and it reminded me of Wim Dicke, who made the single greatest discovery in coeliac disease – that the disease was caused by gluten – and struggled to get his work published.

Willem-Karel Dicke (1905–62) was a paediatrician who practised at the Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague, and later (after the Second World War) at the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital in Utrecht. He looked after many children with coeliac disease. This was then a mysterious condition which caused malabsorption of nutrients in food, leading to diarrhoea, weight loss, anaemia and growth failure. Many had bone deformity due to rickets (caused by lack of vitamin D), and death was not uncommon: a 1939 paper by Christopher Hardwick of Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London reported a mortality rate of 30 per cent among coeliac children. Hardwick described how these children died: ‘The diarrhoea was increased, dehydration became intense, and the final picture was that of death from a severe enteritis.’ It had long been suspected that the disease was food-related, and various diets, such as Dr Haas’s banana diet, were tried, but none was consistently effective. During the 1930s, Dicke had heard of several anecdotal cases of coeliac children who improved when wheat was excluded from their diet. Towards the end of the Second World War, during the winter of 1944–5 – the hongerwinter, or ‘winter of starvation’ – Holland experienced a severe shortage of many foods, including bread, and the Dutch were famously reduced to eating tulip bulbs. Dicke noticed that his coeliac children appeared to be getting better when their ‘gruel’ was made from rice or potato flour instead of the usual wheat. He attended the International Congress of Pediatrics in New York in 1947, and although he was a shy and reticent man, he told as many of his colleagues as he could about his observation on wheat and coeliac disease. Years later, Dicke’s colleague and collaborator, the biochemist Jan van de Kamer, wrote: ‘Nobody believed him and he came back from the States very disappointed but unshocked in his opinion.’

Dicke moved to Utrecht, and formed a research partnership with van de Kamer, who had developed a method for measuring the fat content of faeces. This was a means of quantifying the malabsorption of food from the intestine in these children: the greater the stool fat content, the greater the malabsorption. He began a series of clinical trials of wheat exclusion, and showed that coeliac children got better on this diet. By measuring faecal fat content before and after wheat exclusion, he produced objective evidence of the benefit of this diet. Later, he showed that gluten (the protein which gives bread its elastic quality) was the component in wheat responsible for the disease. Dicke wrote a paper describing his findings and sent it to one of the main American paediatric journals. He did not receive even an acknowledgement, and the manuscript wasn’t sent out for review. Meanwhile, a research group at Birmingham University and the Birmingham Children’s Hospital had heard of Dicke’s work and wanted to test his findings. One of that group, Charlotte Anderson, visited Dicke to see his studies of coeliac children at first hand. He went out of his way to help Anderson with her research; she later paid tribute to ‘his old-world gentility’. Dicke had formally written up his work for his doctoral thesis, presented to the University of Utrecht in 1950. He also sent off a paper to another journal – the Swedish publication Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. This paper was accepted, but by the time it eventually appeared in print, the Lancet had published a paper by the Birmingham group confirming Dicke’s findings. Dicke died young, at fifty-seven, after a series of strokes.

When I began my research on coeliac disease in the 1980s, it was a well-recognized, although relatively uncommon, condition: about 1 in every 2,000 people in Britain were diagnosed with it. It was then much more prevalent in Ireland, particularly in Co. Galway, where the disease was diagnosed in 1 in every 300. In retrospect, this was at least partly due to the fact that the professors of medicine and paediatrics at University College Galway at that time both had a special interest in the condition and actively sought it out. Making a formal diagnosis of coeliac disease in the 1980s was difficult, requiring the prolonged and distressing Crosby capsule intestinal biopsy. (The patient had to swallow a steel bullet – the capsule – attached to a hollow tubing, and wait for at least two hours for the capsule to reach the small intestine.) Gradually, however, the diagnosis became easier. By the late 1980s, biopsies could be obtained using an endoscope, in a procedure that took five or ten minutes; in the 1990s, blood antibody tests became widely available, and were shown to be highly accurate. The ease of these diagnostic tests, along with greater awareness of the condition, led to a steep rise in diagnosis of coeliac disease during the 1990s and 2000s: about 1 per cent of the British and Irish population are now thought to have coeliac disease, although many – possibly most – remain undiagnosed. Coeliac disease is no longer regarded as primarily a disease of children: the diagnosis can be made at any age. Several screening studies (using blood antibody tests) across Europe and the US show that the prevalence of coeliac disease is somewhere between 1 and 2 per cent of the population. The treatment – a gluten-free diet – is lifelong and effective.

The patients I diagnosed with coeliac disease in the 1980s were often very sick. Nowadays, most adults diagnosed with the condition have minimal or no symptoms. The ease of diagnosis and increased public awareness led many people with various chronic undiagnosed ailments to seek tests for coeliac disease. These ‘medically unexplained’ conditions included IBS, chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia. A few did indeed have coeliac disease, but most didn’t. Undaunted by negative tests for coeliac disease, some – encouraged by stories in the media – tried a gluten-free diet, and felt better. Their doctors attributed this to suggestibility and the placebo effect. Many complementary and alternative medicine practitioners, however, thought it was a real phenomenon, and began to recommend a gluten-free diet for all sorts of chronic ailments. These patients were not satisfied with reassurances along the lines of ‘well, you’re not coeliac but if it makes you feel better, give the diet a go’, and demanded a formal diagnostic label for what ailed them. As the bitter history of chronic fatigue syndrome/ME has shown, patients with ‘medically unexplained’ symptoms are often resistant to psychological formulations. Our contemporary culture, for all its superficial familiarity with psychology and its vocabulary, remains uncomfortable with the notion of ‘psychosomatic’ disease. Many of my IBS patients prefer gluten sensitivity to ‘stress’ as the explanation for their symptoms, just as some people with chronic fatigue believe they have an infection with the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Doctors now spend much of their time manoeuvring the ever-widening gap between their patients’ beliefs and their own.

By the new millennium, coeliac disease researchers had run out of new ideas: the disease was easily diagnosed and easily treated – what was left to know? Then along came a new opportunity called non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. In February 2011, fifteen coeliac disease researchers from around the world met at a hotel near Heathrow Airport. They were keen to give this phenomenon of self-diagnosed gluten sensitivity some form of medical credibility, or, as they put it, to ‘develop a consensus on new nomenclature and classification of gluten-related disorders’. They were not shy about the commercial agenda: ‘The number of individuals embracing a gluten-free diet appears much higher than the projected number of coeliac disease patients, fuelling a global market of gluten-free products approaching $2.5 billion in global sales in 2010.’ The meeting was sponsored by Dr Schär, a leading manufacturer of gluten-free foods. A summary of this meeting was published in the journal BMC Medicine in 2012. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity now became an officially recognized part of ‘the spectrum of gluten-related disorders’. Dr Schär must have been pleased with this consensus, which led to several studies on non-coeliac gluten sensitivity over the next few years. Most of these studies were poorly designed, badly written up, and published in low-impact, minor journals, the sort of work that John Ioannidis would eviscerate with relish. One of the very few well-designed studies, from Monash University in Melbourne, published in the prestigious US journal Gastroenterology, found that people with self-reported gluten sensitivity did not react to gluten (disguised in pellets) any more than they did to a placebo.

Despite these inconclusive studies, many review articles appeared in the medical journals describing the symptoms of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity and how to diagnose it. Several of these papers appeared in the journal Nutrients, which, for a period, featured in a list of predatory journals. Professor Carlo Catassi, an Italian paediatrician, has published several papers on non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, mainly in Nutrients. He is probably the most prominent name associated with the condition and has received ‘consultancy funding’ from the Dr Schär Institute. In a 2015 review article for the Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, Catassi listed the following as clinical manifestations of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity: bloating, abdominal pain, lack of wellbeing, tiredness, diarrhoea, nausea, aerophagia (swallowing air), gastro-oesophageal reflux, mouth ulcers, constipation, headache, anxiety, ‘foggy mind’, numbness, joint and muscle pain, skin rash, weight loss, anaemia, loss of balance, depression, rhinitis, asthma, weight gain, cystitis, irregular periods, ‘sensory’ symptoms, disturbed sleep pattern, hallucinations, mood swings, autism, schizophrenia, and finally – my favourite – ingrown hairs. In a Disclosure Statement, we are told that ‘the writing of this article was supported by Nestlé Nutrition Institute’.

Professor Catassi is the first author, too, of a paper entitled ‘Diagnosis of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno Experts criteria’, also published in Nutrients. In October 2014, a group of thirty ‘international experts’ met in Salerno, Italy, ‘to reach a consensus on how the diagnosis of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity should be confirmed’. The meeting was again funded by Dr Schär. Only six of the fifteen experts who met at Heathrow in 2011 made it to Salerno: was there a schism in the church of gluten sensitivity? The experts gave us criteria to diagnose a condition that probably doesn’t exist. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity is thus a model for what might be called a post-modern disease. It does not have a validated biological marker (such as a blood test or a biopsy), and the diagnosis is made on the basis of a dubious and highly arbitrary symptom score. Its ‘discovery’ owes much to patient pressure and the suborning of expert opinion by commercial interests. I found a picture online of the experts gathered at Salerno, and was reminded of a fresco in the Sistine Chapel depicting the first Council of Nicea in AD 325. The council was convened by the emperor Constantine to establish doctrinal orthodoxy within the early Christian Church. The industry-sponsored get-together in Salerno had similar aims. Why did these experts attach their names to a consensus on how to diagnose this pseudo-disease? Unlike Willem-Karel Dicke, a clinical doctor who stumbled on an idea he desperately wanted to test, the Salerno experts are typical contemporary biomedical researchers: their motivation is professional, rather than scientific. Few share Dicke’s qualities of modesty, reticence and ‘old-world gentility’. Their aim is expansionist: the establishment of a new disease by consensus statement, the Big Science equivalent of a papal bull. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity has been decreed by this edict, just as papal infallibility was decreed by the First Vatican Council in 1870. The creation of this new disease benefits the researchers, who now claim many more millions of ‘patients’; it benefits the food industry, with dramatic rises in sales of ‘free-from’ foods; and it benefits people with psychosomatic complaints, who can now claim the more socially acceptable diagnosis of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. If so many people are benefiting from all of this, why worry about science, or truth?

Consensus statements have been part of the medical academic landscape since the 1970s, and frequently mocked as GOBSAT (‘good old boys sat around a table’). The American Psychiatric Association decided in 1973 that homosexuality was no longer a disease: this depathologization was declared by consensus, after a vote among the association’s members. Although it is unlikely, they could just as easily redeclare it as a disease. Petr Skrabanek wrote on the phenomenon of consensus conferences in 1990:

the very need for consensus stems from lack of consensus. Why make an issue of agreeing on something that everyone (or nearly everyone) takes for granted? In science, lack of consensus does not bring about the urge to hammer out a consensus by assembling participants whose dogmatic views are well known and who welcome an opportunity to have them reinforced by mutual backslapping. On the contrary, scientists are provided with a strong impetus to go back to the benches and do more experiments.

Consensus conferences very often facilitate the aims in particular of pharma, by expanding the pool of ‘patients’ who might need their product. Consensus statements, for example, set the levels above which cholesterol levels and blood pressure is ‘abnormal’ and must be ‘treated’. Careful selection of participants guarantees the ‘right’ consensus. In the ‘hierarchy of evidence’ espoused by evidence-based medicine, however, consensus statements are near the bottom, slightly above ‘a bloke told me down the pub’. ‘The consensus of experts’, remarked Alvan Feinstein, ‘has been a traditional source of all the errors that have been established throughout medical history.’ The British mathematician Raymond Lyttleton coined the term ‘the Gold Effect’ (after his friend, the Austrian physicist Thomas Gold) in 1979. In Follies and Fallacies in Medicine (1989), James McCormick and Petr Skrabanek explained how the Gold Effect transforms belief in some idea into certainty: ‘Articles on the idea, initially starting with “Evidence has accumulated”, rapidly move to articles that open “The generally accepted”, and before long to “It is well established”, and finally to “It is self-evident that”.’

Although the coeliac disease experts accepted commercial sponsorship and then obligingly legitimized the highly dubious entity that is non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, two entrepreneurial American doctors, William Davis, author of Wheat Belly (2011), and David Perlmutter, author of Grain Brain (2013), took the public awareness of gluten to the next level. Their bestselling books contributed substantially to the popular perception of gluten as toxic not just for coeliacs, but for everyone. Davis (a cardiologist) argues that ‘modern’ wheat is a ‘perfect, chronic poison’, that it is addictive and is the main cause of the current obesity epidemic. Perlmutter (a neurologist) claims that ‘modern grains are destroying your brain’, causing not only Alzheimer’s disease, but also ‘chronic headaches, depression, epilepsy and extreme moodiness’. This is, of course, absurd, and completely unsupported by any evidence, but it is a model of restraint compared to Professor Catassi’s list of ‘clinical manifestations of gluten sensitivity’. Perlmutter’s and Davis’s books have sold in their hundreds of thousands, but are dismissed by scientists. Science, however, should be more concerned about the reputational damage inflicted on it by the feverish musings of the Salerno experts.

All of this has created a whole new market, with new consumers. YouGov, the UK-based market-research firm, produced a report in 2015 called ‘Understanding the FreeFrom consumer’. Gluten-free is not the only ‘free-from’ food: consumers can choose lactose free, dairy free, nut free, soya free and many other products. Ten per cent of the UK population are ‘cutting down’ on gluten; remarkably, two-thirds of those cutting down on gluten do not have a sensitivity, self-diagnosed or otherwise, and are referred to as ‘lifestylers’ by the marketing experts. Lifestylers tend to be young, of high social class, female, vegetarian, regular exercisers, and ‘spiritual but not religious’. The ‘free-from’ food market in Britain is booming, with annual sales of £740 million; gluten-free products make up 59 per cent of it. This market is growing at a rate of roughly 30 per cent annually. Twenty million Americans claim that they experienced symptoms after eating gluten. One-third of adults in the US say they are reducing or eliminating their gluten intake. You can buy gluten-free shampoo and even go on a gluten-free holiday. It is easy to mock this foolishness, and many do: look up J. P. Sears’s ‘How to become gluten intolerant’ on YouTube. Meanwhile, several celebrities, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Miley Cyrus and Novak Djokovic, have proclaimed the benefits of gluten avoidance. ‘Everyone should try no gluten for a week!’ tweeted Miley Cyrus. ‘The change in your skin, physical and mental health is amazing! U won’t go back!’ The gluten-free food market, which had hitherto been a small, niche business, has expanded rapidly over the last several years. In 2014, sales of gluten-free foods in the US totalled $12.18 billion; it has been estimated that the market will grow to $23.9 billion by 2020.

With the exception of the 1 per cent of the population who are coeliac, there is no evidence that gluten is harmful. There is, however, growing evidence that a gluten-free diet in non-coeliac people may carry a risk of heart disease, because such a diet reduces the intake of whole grains, which protect against cardiovascular disease. Fred Brouns, professor of health food innovation management at Maastricht University, wrote the pithily entitled review ‘Does wheat make us fat and sick?’ for the Journal of Cereal Science in 2013. He examined the claims made against wheat by both William Davis and David Perlmutter – namely, that it causes weight gain, makes us diabetic and is addictive. He addressed also the charge (made by Davis, Perlmutter and the Heathrow experts) that modern wheat contains higher levels of ‘toxic’ proteins. Brouns and his colleagues reviewed all the available scientific literature on wheat biochemistry, and concluded that wheat (particularly whole wheat) has significant health benefits, including reduced rates of type 2 diabetes and heart disease. He found no evidence that the wheat we eat now is in any way different from that consumed during the Palaeolithic era, apart from having higher yields and being more resistant to pests. Genetically modified wheat has not been marketed or grown commercially in any country. ‘There is no evidence’, he concluded, ‘that selective breeding has resulted in detrimental effects on the nutritional properties or health benefits of the wheat grain.’

Alan Levinovitz, a professor of religion at James Madison University in Virginia, was struck by the parallels between contemporary American fears about gluten and the story of the ‘grain-free’ monks of ancient China. These early Daoists, who flourished 2,000 years ago, believed that the ‘five grains’ (which included millet, hemp and rice) were ‘the scissors that cut off life’, and led to disease and death. The monks believed that a diet free of the five grains led to perfect health, immortality and even the ability to fly. In his book The Gluten Lie Levinovitz places contemporary American anxieties about gluten in a long line of food-related myths: ‘As with MSG, the public’s expectation of harm from gluten is fuelled by highly profitable, unscientific fearmongering, validated by credentialed doctors. These doctors tap into deep-rooted worries about modernity and technology, identify a single cause of all our problems, and offer an easy solution.’

Does it really matter if many people adhere to a gluten-free diet unnecessarily? After all, it’s their own choice, and if they’re happy with it, why should we bread eaters fret? The gluten story is a symptom of the growing gap between rich and poor. For most of human history, the main anxiety about food was the lack of it. Now, the worried well regard food as full of threats to their health and are willing to pay a premium for ‘free-from’ products. People who do not have scientific knowledge are likely to take the food industry’s claims at face value, and their children, bombarded with advertising on social media and television, will add to the pressure. When food was scarce, fussiness about it was frowned upon and socially stigmatized because it was wasteful of a precious resource. What used to be simple fussiness has now progressed to self-righteous grandstanding, and self-diagnosed food intolerance is often the first step on the via dolorosa of a chronic eating disorder.

We have a strange paradox: the majority of people who should be on a gluten-free diet (those with coeliac disease) aren’t, because most people with coeliac disease remain undiagnosed. The majority of those who are on a gluten-free diet shouldn’t be, because they do not have coeliac disease. The ‘lifestylers’ are deluded, and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity is a pseudo-disease. People with coeliac disease are ambivalent about the gluten-free fad: they have benefited, because gluten-free produce is now easily obtained, and restaurants and supermarkets are very gluten aware. They resent, however, the narcissistic lifestylers and the self-diagnosed gluten intolerant for trivializing the condition of the 1 per cent who really do need to go gluten free.

The Great Discovery in coeliac disease was made by Wim Dicke. This was a typical breakthrough from medicine’s golden age, achieved by a determined clinical doctor who worked with little financial or institutional support. Although Dicke struggled to publish his crucial discovery, since then thousands and thousands of papers have been published on coeliac disease, many – like mine – describing immunological epiphenomena of no clinical significance or benefit to patients. John Platt’s observation that most research studies produce bricks that ‘just lie around in the brickyard’ sums up most of coeliac disease research; I am ashamed to admit that I produced a few of these bricks. Coeliac disease is easily diagnosed and easily treated, yet the coeliac research cavalcade trundles on, with its conferences and consensus statements. Dicke is a fine example of the amateur researcher from the golden age. His integrity and reticence, not to mention his willingness to assist other researchers, now seem quaint. His inspiration during the hongerwinter saved the lives of many sick children. I wonder what this humble old-fashioned doctor would have made of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, the Salerno experts, and Miley Cyrus.