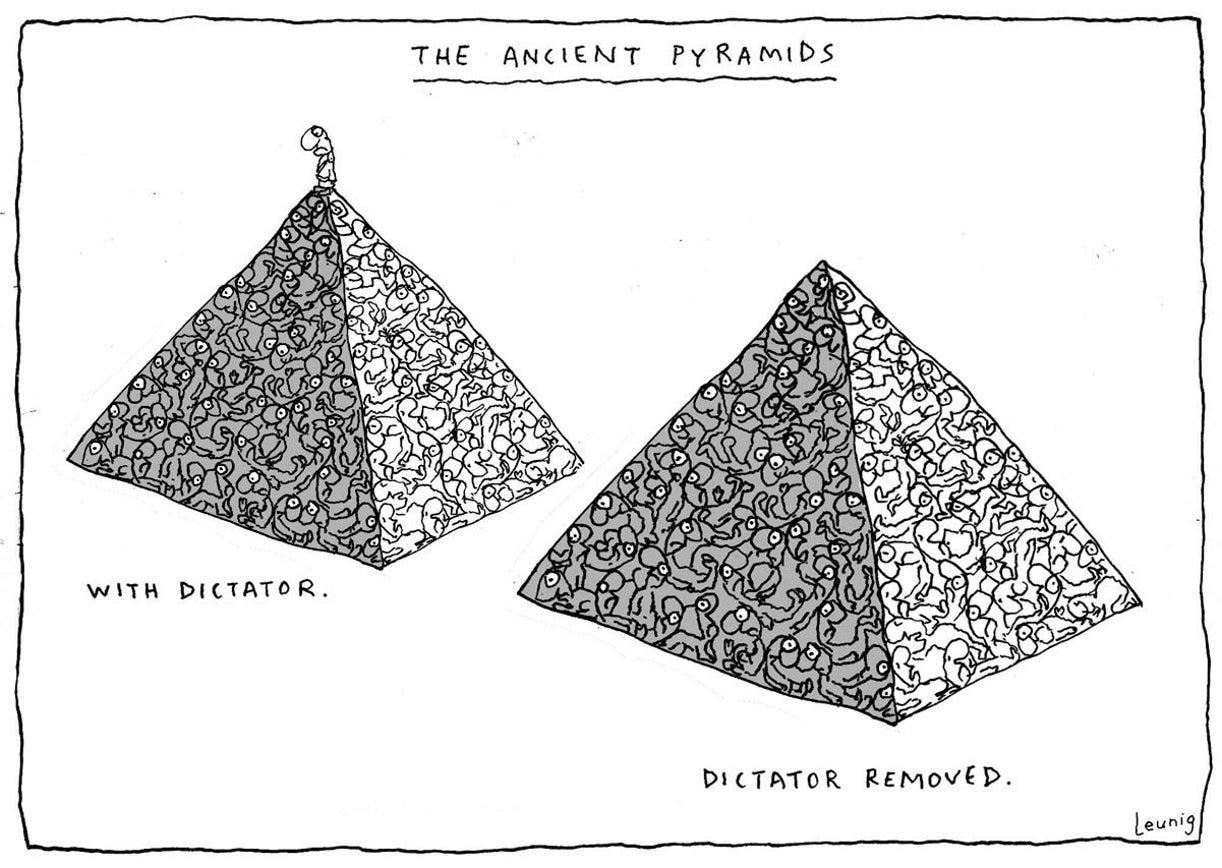

Regime change: What could possibly go wrong?

By neoconservative mugged by the reality of the Iraq invasion. Iranian-American Sohrab Ahmari. The title for his piece says it all.

The regime change maniacs are back Iran is in their sights, and they’ve learned nothing

In 2002, the Bush administration was met with scant resistance as it drummed up the case for toppling Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq. But there were a handful of dissenters, above all Brent Scowcroft. The two-time former national-security adviser urged the nation to consider the law of unintended consequences — and to open its imagination to nightmare scenarios.

A similar imagination is desperately needed today, as hawks in Washington and Jerusalem fantasise about collapsing the Iranian regime. It's a bewildering replay of the same overconfidence that gave birth to the Iraq catastrophe.

An invasion of Iraq, Scowcroft argued early on, would distract Washington from the pursuit of Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda, the actors behind 9/11. Drawing on his experience as the elder Bush's adviser during the Gulf War, he warned that regime change would mean "occupation of an Arab land, hostile Arab land". Not for months, but for years. In short, Scowcroft predicted everything that went wrong with Operation Iraqi Freedom.

The war's advocates quickly dismissed his warnings. Reuel Marc Gerecht insisted that "these fears for the war on terrorism are unfounded". While William Kristol "laughed" about Scowcroft's emphasis on foreign-policy realism and Middle-East stability...

More than two decades on, all but a few unreconstructed war boosters consider the project a costly, colossal mistake. Yet here we are, in 2025, poised to attempt the same in Iran: a country that is vaster, more populous, and significantly more complex than Iraq. And we're doing it with even less planning and forethought.

Over the weekend, according to Axios, the Israeli government formally requested that the United States intervene in its operation against Iran. But whether or not Washington joins the fight, it will inevitably be drawn into the vexing aftermath.

Should Israel continue on its current trajectory, including the targeting of the Islamic Republic's civilian and energy infrastructure, it will break the Iranian state. But the Israelis are neither capable of, nor inclined to, pick up the pieces afterward. Rather, they will "internationalise" the problem. Which means: Uncle Sam, roll up your sleeves.

For be in no doubt, regime collapse will generate a massive crisis destabilising the Middle East and regions far beyond it...

Foremost will be the crisis of state authority. The central problematic in Iranian history, going back millennia, is the fraught relationship between state and society. Optimists may note that Iran isn't Iraq — an ethno-sectarian hodge-podge cobbled together within artificially drawn borders...

But while this is true, even this innate coherence couldn't ease the deeper struggle: the difficulty of rebuilding order in a context of profound, culturally ingrained tension between state and society. At the heart of Iran's political tradition lies estebdad — arbitrary rule. Economic life revolves around favour from the state, not legally defined rights and duties...

"It's folly to believe that the current regime can be collapsed without American forces having to descend to prop up a new state."

The problem is that Reza Pahlavi, the exiled heir to Iran's final dynasty, doesn't inspire much confidence. Some who have collaborated with him describe a spoiled dauphin, intellectually incurious and indolent...

But Pahlavi's character is finally beside the point. The real issue is that he would need massive outside assistance to even begin to assert control over a sprawling country of 90 million souls.

Which brings us to the second major crisis: separatism. Although Iran was called "Persia" by the ancient Greeks, Persians make up only a bare majority of the country... Various external actors are bent on carving out ethnic fiefdoms from Iranian territory...

Here, then, is a recipe for a civil war that would radiate instability into Iraq, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, and elsewhere...

Let's not forget the nuclear program, either. Among the separatist groups are hard-core Sunni Islamists. Who is going to secure Iran's nuclear programme against the Islamists? The United States...

Proponents of intervention insist that sceptics have "overlearned" the lesson of Iraq and Afghanistan. Maybe. Then again, given the stakes, overlearning is surely better than under-learning.

A contrary view

Regime change in … where was that again?

The US may have gone to war in Vietnam without anyone in the State Department being fluent in Vietnamese, but it has to be conceded that, within a decade or so many people in the State Department became familiar with Vietnamese restaurants - as we all are these days. And, as you’ll agree, we mustn’t let the best be the enemy of the good.

AUKUS lifeline

Gareth Evans thinks we should stop playing make-believe. So do I.

As the Trump administration conducts a formal review of the 2021 AUKUS nuclear-submarine agreement, Australians should be hoping and praying that the arrangement collapses. The purchase was a bad deal at the time, and it makes even less sense now.

The "AUKUS" partnership, the 2021 deal whereby the United States and the United Kingdom agreed to provide Australia with at least eight nuclear-propelled submarines over the next three decades, has come under review by the US Defense Department. The prospect of its collapse has generated predictable handwringing among those who welcomed the deepening alliance, and especially among those interested in seeing Australia inject billions of dollars into underfunded, underperforming American and British naval shipyards. But in Australia, an AUKUS breakdown should be a cause for celebration.

After all, there has never been any certainty that the promised subs would arrive on time. The US is supposed to supply three, or possibly five, Virginia-class submarines from 2032, with another five newly designed SSN-AUKUS-class subs (built mainly in the UK) coming into service from the early 2040s. But the US and the UK's industrial capacity is already strained, owing to their own national submarine-building targets, and both have explicit opt-out rights. Some analysts assume that the Defense Department review is just another Trumpian extortion exercise, designed to extract an even bigger financial commitment from Australia. But while comforting to some Australians (though not anyone in the Treasury), this interpretation is misconceived. There are very real concerns in Washington that even with more Australian dollars devoted to expanding shipyard capacity, the US will not be able to increase production to the extent required to make available three – let alone five – Virginia-class subs by the early 2030s...

Even in the unlikely event that everything falls smoothly into place – from the transfers of Virginia-class subs to the construction of new British boats, with no human-resource bottlenecks or cost overruns – Australia will be waiting decades for the last boat to arrive. But given that our existing geriatric Collins-class fleet is already on life support, this timeline poses a serious challenge. How will we address our capability gap in the meantime?

Cost-benefit analysis should have killed the project from the outset. But in their eagerness to embrace the deal, political leaders on both sides of parliament failed to review properly what was being proposed. Even acknowledging the greatly superior speed and endurance of nuclear-powered subs, and accepting the heroic assumption that their underwater undetectability will remain immune from technological challenge throughout their lifetimes, the final fleet size seems hardly fit for the purpose of national defense.

Given the usual operating constraints, Australia would have only two such subs deployed at any one time. Just how much intelligence gathering, archipelagic chokepoint protection, sea-lane safeguarding, or even deterrence at a distance will be possible under such conditions? Moreover, the program's eye-watering cost will make it difficult to acquire the other capabilities that are already reshaping the nature of modern warfare: state-of-the-art drones, missiles, aircraft, and cyber defense.

The remaining reason for believing, as former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating put it, that an American opt-out "will be the moment Washington saves Australia from itself," concerns AUKUS's negative implications for Australia's sovereignty. The Americans agreed to the deal because they saw it to be in their strategic interest, not ours. As then-US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell observed (indiscreetly) last year, "we have them locked in now for the next 40 years." It defies credibility to believe that the US would transfer such a sensitive technology to us – with all the associated emphasis on the "interchangeability" of our fleets and new basing arrangements in Australia – unless it could avail itself of these subs in a future war...

All that AUKUS and its associated alliance commitments have done for Australia is paint more targets on our back. Alongside the Pine Gap satellite communications and signals intelligence facility – which has always been a bull's-eye – one can add Perth's Stirling submarine base, the Northern Territory, with its US Marine and B-52 bases, and possibly a future east-coast submarine base. The crazy irony is that we are spending huge sums to build a new capability intended to defend us from military threats that are most likely to arise simply because we have that capability – and using it to support the US, without any guarantee of support in return should we ever need it.

If the AUKUS project does collapse, it would arguably still be possible for Australia to acquire replacements for its aging submarine fleet within a reasonable time frame – and probably at less cost, while retaining real sovereign control – by purchasing off-the-shelf technology elsewhere... But a better defense option may simply be to recognize that the latest revolution in military technology is real, and that our huge continent and maritime surroundings will be better protected by a combination of self-managed air, missile, underwater, and cyber detection capabilities than by a handful of crewed submarines. There is no better time to start thinking outside the US alliance box.

Stunning pic

Or here for the audio files.

The magical mystery of the Beatles

Friend and fellow purveyor of his craft at ClubTroppo, Adonis Sarhanis

There Was No Sign The Beatles Were An Excellent Band

A surefire way for a band to sound off is having a bad drummer; a surefire way to sound good is having a flashy guitarist or singer. And the Beatles had a bad drummer in Pete Best, rather humdrum guitarists in Lennon and Harrison and, while their singing voices were pretty good, you certainly wouldn't describe them as flashy (their harmonies popped only after being signed!).

Granted, the Beatles were the most popular live act in Liverpool. Alas, that did not immediately translate to the studio — and, regardless, no one knows who the most popular bands at the time were from Manchester, Leeds or Birmingham.

Decca gets the narrative raspberries for turning down the Beatles, but another three record labels were also as unimpressed by the Beatles. Parlophone eventually signed them up principally because George Martin, their eventual producer, thought they were a cheeky and amusing bunch even though musically they sounded utterly unremarkable...

There Was No Sign The Beatles Were Outstanding Songwriters

Before being signed, the Beatles had only written one song that would turn into a hit: Love Me Do, which isn't particularly interesting as compositions go, and only got to 17 on the UK charts as their first single anyway.

Please Please Me and From Me To You were the follow ups and both hit number 1. Again, not particularly remarkable and they would have easily been forgotten if not for what came next.

What came next: She Loves You, which became the then best-selling UK single of all time and doubled the combined sales of their previous three singles. (Aside: Denny Laine and McCartney's Mull of Kintyre as performed by Wings beat the UK sales record in 1977!)

There was no hint of anything as good as She Loves You in their kitbag. It's a quantum leap in songwriting and hookcraft...

There Was No Sign George Martin Was A Musical Transmuter

Before the Beatles, George Martin had never worked with a rock and roll band. Martin's previous experience was involved with completely forgettable comedy recordings, classical music and light orchestral pop. Everything he was doing in the studio for this newfangled rock and roll, Martin was doing on the fly.

And don't let Martin's toffy accent misguide you: Martin's success was self-made. He was a humble working-class boy with a special talent for music and he developed his skills in the classical style of the upper-classes but with none of the snobby baggage. So when the Beatles were cracking jokes at Martin's expense at their audition, the teasing and general bantering endeared him to the group because there was no class divide.

That endearment and general solidarity extended to their working relationship. Martin worked with the Beatles, sharpening them and developing them but never directly moulding them. On She Loves You, Martin brought out the hook, sharpened the harmonies, made it sparkle...

There Was No Sign Drums Could Be A Weapon

Drums were never a thing before She Loves You.

Sure, there was the Bo Diddley drum beat or some of the more raucous Little Richard numbers. But those drums never propelled the song, never made it stick out.

And right from the outset, the tom-tom fill that heads into the rush of the yeah-yeah-yeahs that smack into the falling-over snare at the end of the phrase is pumping sizzle that Martin recognised as fire and duly amplified in the mix.

All this means that the Beatles went from a drummer who couldn't keep a steady rhythm to their tearaway hit featuring drums of unprecedented prominence in about a year.

DeepSeek keeps out of DeepWater

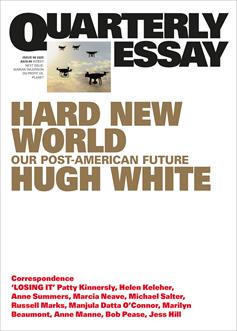

Quarterly Essay, Hard New World: Our Post-American Future

As I said to Hugh at a function in Canberra about a month ago, “Hugh, I’m getting increasingly worried about you. I find I never disagree with anything you say.”

Anyway, whether you agree with Hugh as much as I find myself doing, you get a chance to come and hear him talk about things it’s very important for our mainstream politicians not to talk about (for obvious reasons.)

16 June: Gleebooks (NSW) – with Bruce Wolpe

18 June: Avid Reader (QLD)

19 June: Outspoken Maleny (QLD)

25 June: Hawke Centre (SA) – with Misha Ketchell

26 June: Roaring Stories (NSW) – with Sam Roggeveen

27 June: Stanton Library (NSW)

Jacinda Ardern: the style is the substance

I think there are two big things Jacinda Ardern can be proud of. First it looks like she happened to get the best advice in the world from her scientific establishment on COVID. And she took it. Getting to near eradication and not going the whole way was absurd - at least if your country was small and homogenous enough to keep it that way once you’d eradicated it. (And I’m not just saying this with hindsight, I was saying it at the time.)

And her handling of the Christchurch massacre was a fine thing, particularly her refusing to use the name of the perpetrator. To this day I remain blissfully ignorant of his name, not like the murderer of John Lennon or the perpetrator of the Port Arthur massacre.

As the Newyorker puff piece below reports, it was strange the way in which Ardern’s huge success with COVID was so lavishly rewarded at the ballot box at the end of 2020 and then repudiated just three years later. What’s strange about it is that the two Australian premiers most associated with strong lockdowns were Mark McGowan from WA and Dan Andrews and they remained wildly popular. (So popular in fact that Dan was able to saddle the Victorian balance sheet with vast liabilities for a generation. Indeed, against his predecessors similarly misjudged refusal to invest, Dan’s flipping of the switch towards overinvestment and now the absurdly marginal projects like the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop has been, and remains something to behold. Oh well, it keeps the CMFEU happy and that’s the main thing I guess. But I digress.)

Perhaps the difference is sexism. Who knows? But one thing Ardern became famous for was talking a good game while not doing very much to change things. Sure enough when I asked ChatGPT to tell me of her important policy achievements, they’re almost all in the ‘vibe’ category. As I’ve argued elsewhere, that includes something for which she became famous wellbeing budgeting - which was nothing of the kind - it was wellbeing themed budgeting in the same way that this year’s ball might have a pirates theme, and next year it might be gladiators. Anyway, stand by for ‘resilience’ budgeting. Or perhaps it will be ‘sustainable development’ budgeting.

In 2022, Jacinda Ardern, the then Prime Minister of New Zealand, was approached by a stranger in an airport bathroom. Ardern was alone, washing her hands, when a middle-aged woman walked up to her at the sink. She stood uncomfortably close, Ardern recalls in her new memoir, "A Different Kind of Power"—"so close I could feel her heat against my cheek." "I just wanted to say thank you," the woman told her, with what Ardern describes as a "seething, non-specific rage." "Thank you for ruining the country."

Outside New Zealand, Ardern is regarded very differently, as a liberal paragon among world leaders. ... Yet it was the pandemic that crystallized an image of Ardern's New Zealand as a quasi-fantastical place—the land that toxic populism forgot.

In March, 2020, Ardern made the radical decision to pursue a strategy of eliminating COVID-19 by closing the border to visitors and briefly enacting one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. For the better part of a year, New Zealand had zero new COVID cases outside quarantine facilities, and a death count in the double digits. ... Ardern cruised to a second term in late 2020, with polling showing that she was the country's most popular leader in a century.

By the time the border reopened, in mid-2022, the population was ninety per cent vaccinated. Research has found that the country's aggressive approach to COVID resulted in a death rate eighty per cent lower than that of the United States, saving as many as twenty thousand lives.

Soon after Ardern left office, her party sustained an election loss described as a "bloodbath." New Zealand is now led by a conservative coalition whose first Deputy Prime Minister, Winston Peters, secured his position by appealing to anti-vaxxers and has compared Ardern's government with Nazi Germany's. Ardern herself has spent the past two years living in the United States, having become so polarizing that she has virtually vanished from public life in her home country.

New Zealand's government initially intended to take the same approach to COVID that most countries did—using restrictions to slow, but not stop, the spread of infection. ... Then, Ardern's science adviser arrived in her office with an alarming graph. ... "This graph was telling me that there was no way to make COVID small," Ardern writes. "It was going to be huge, or we'd have to try to make it almost nothing at all."

The country's remoteness was a significant advantage in its quest to stamp out the virus, but so was a remarkable social cohesion that eluded most Western nations. ... After an initial rise, case numbers started falling, and thirty-three days in the government began easing restrictions.

By then, New Zealand had been cut off from the outside world for more than a year. ... An upside-down narrative emerged, in which New Zealanders were trapped in a mode of draconian deprivation while all sensible nations had opened up and moved on.

On February 8, 2022, a convoy of vehicles descended on Wellington, inspired by the Canadian trucker protest. ... "I saw my own image, with a Hitler mustache, monocle, and 'Dictator of the Year' emblazoned above my face. I saw the gallows, complete with a noose, which people said had been erected for me. I saw the American flags, the Trump flags, the swastikas."

The protesters represented a small portion of the population, but the discontent was mainstream. ... By January, 2023, Ardern's net approval rating would fall to fifteen points, from an extraordinary peak of seventy-six in May, 2020.

When Ardern announced her resignation, on January 19, 2023, she explained that she "no longer had enough in the tank."

It's a strange irony that the result of New Zealand's unique pandemic experience is a country beset by the same problems as those facing most other modern democracies: polarization, disinformation, declining trust in government. ... New Zealand started out as the closest thing to a control group among major nations—small, isolated, unified, and therefore able to avoid COVID's worst consequences. Yet even that wasn't enough to avoid the kind of backlash that would sweep incumbents out of office worldwide in 2024, in a convulsive attempt to put the COVID years out of sight and mind.

That’s exactly what Hitler’s been talking about

Yes, we should have proportionate fines

This is the kind of thing left of centre governments could be doing. It would raise some revenue and make things fairer. It would be denounced as ‘class war’ by the Murdoch press. What’s there not to like? I guess they wouldn’t increase revenue enough to make it worth it. Brian Klaas has a long post on it. I’m just extracting the basic argument below.

As one sociopathic millionaire TikToker—a loathsome social leech who presumably sees other humans as wallets with a pulse—recently put it:

“Broke people see a fine, but I see VIP parking.”

...when I drive by [a particular] spot in the evenings, I'm often met by the garish sight of an illegally parked mantis green McLaren supercar in front of another illegally parked Ferrari. The former retails for around £215,000 ($292,000); the latter for a more modest £178,000 ($242,000)...

But when I drive by, I've also started noticing another colorful sight attached to these supercompensating supercars: a neon yellow parking fine notice issued from the local council, charging the owners £50. For them, it's less than a slap on the wrist; the McLaren owner could park illegally every day, 365 days a year, for 12 years—a significant proportion of his life—and still not fully reach the amount he paid for his grotesque steel status symbol...

This dynamic raises the obvious question: if government fines exist to deter illegal and unethical behavior, why do most jurisdictions impose the same financial penalties on billionaires and beggars, plutocrats and paupers?...

The €121,000 Speeding Ticket

In 2023, the 76 year-old multimillionaire Finnish businessman Anders Wiklöf was clocked going 82 km/hour in a 50 zone. Because of his excessive speed—and because Wiklöf had twice been cited for speeding previously—the Finnish fine levied was steep: €121,000, or roughly $138,000.

Finland uses the "day fine" system. First, determine how many days worth of work should be deducted from the person's earnings. Second, multiply the days by that person's daily income. A one day fine for someone earning $30,000 per year would be $82; for someone earning $1 million per year it would be $2,740. The penalties impose the same relative consequence...

Redefining Equal Justice

There is, in my view, a rather warped critique of proportional fines, which brands them as a form of unequal justice. The same crime, they say, should always have the same punishment.

But that's an absurd inversion of the principle of equal justice. Imagine a punishment protocol that applies the same penalty to every offender: each criminal must line up against a wall, at which point a horizontal guillotine will slice toward them, exactly six feet off the ground. For shorter people, there will be no punishment; for others, a harrowing haircut; and for those much above six feet, death. The "same" punishments often have differential effects.

Abortion Restrictions and Intimate Partner Violence in the Dobbs Era

Dhaval M. Dave, Christine Durrance, Bilge Erten, Yang Wang, Barbara L. WolfeIn overturning Roe v. Wade and triggering laws in many states that ban or severely restrict abortions, the Supreme Court’s landmark 2022 Dobbs decision dramatically altered the landscape for reproductive health in the U.S. Prior research has highlighted the far-reaching impact of abortion restrictions for women and families, which extend beyond their proximate effects on abortions, births, and fertility. We provide some of the first causal evidence on how abortion restrictions in the post-Dobbs era have impacted women’s risk of exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV). IPV is the most common form of violence experienced by women, and changes in access to abortion may generate unintended effects on various inputs (economic resources, stress, intra-household bargaining) that could affect relationship dynamics and raise the risk of IPV. Leveraging information on IPV incidents reported to law enforcement from 2017-2023 combined with post-Dobbs changes in county-level trav! el distance to abortion facilities, analyses are based on a generalized difference-in-differences approach. We find that abortion restrictions – alternately measured by the increase in travel distance and by the presence of a near-total ban – significantly increased the rate of IPV for reproductive-aged women in treated counties on the order of about seven to 10 percent. These estimates imply at least 9,000 additional incidents of IPV among women in the treated “trigger ban” states, which would be predicted to add over $1.24 billion in social costs.

The Bonfire of the Banking Regulators?

Separating money creation from finance

Willem H. Buiter reviews two books which come to the same conclusion I arrived at some years ago; that money creation should be separated from financial intermediation. The books are Peter Conti-Brown and Sean H. Vanatta’s new history of American bank supervision, Private Finance, Public Power and Dan Awrey’s Beyond Banks.

Despite numerous reforms, the US financial regulation system remains a patchwork of federal and state agencies with overlapping mandates and conflicting objectives. Two new books underscore the need to streamline bureaucracy, simplify regulations, and separate money creation from financial intermediation.

Convergent Conclusions on Banking Reform

Both books converge on a fundamental principle: the separation of money creation from financial intermediation. Conti-Brown and Vanatta's historical analysis points toward regulatory consolidation under Fed authority, while Awrey advocates for "narrow banking" where monetary IOUs are fully backed by central bank reserves. [Despite examining different aspects of the financial system—one focused on regulatory history, the other on monetary theory—both works conclude that demonetizing bank liabilities would create a simpler, more stable framework requiring less intrusive regulation.]

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA – As US President Donald Trump intensifies his campaign to dismantle the regulatory state, Peter Conti-Brown and Sean H. Vanatta's new history of American bank supervision, Private Finance, Public Power, has proven more timely than its authors likely anticipated...

But even without such a comprehensive overview, this well-written book sheds light on America's complex and often chaotic financial system, underscoring the need for a radical simplification of the regulatory frameworks that govern deposit-taking banks and other financial intermediaries. Another recent book, Dan Awrey's Beyond Banks, comes close to such radicalism by advocating a structural separation between the issuance of monetary IOUs and private financial intermediation. [Both authors thus arrive at the same core insight: banks should not simultaneously create money and engage in risky lending.] This would demonetize bank liabilities and allow for a less stringent and intrusive regulatory regime for banks.

Too Many Regulators

As Conti-Brown and Vanatta observe, the current system of bank supervision in the United States is extremely fragmented, with oversight responsibilities divided among the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and various state authorities...

Too Many Banks

The problem, historically, has been that the US has far too many banks. Chartering competition between the OCC and state banking authorities has led to a proliferation of mostly small, inefficient, and financially fragile institutions... The system remains highly decentralized, with 4,487 FDIC-insured banks and 4,653 federal credit unions.

The large number of small banks likely results from legal and regulatory barriers to consolidation rather than any efficiency advantage...

Too Many Targets

Bank regulators have too many, often conflicting, objectives... Overloading institutions tasked with ensuring financial stability risks undermining their effectiveness...

Streamlining Financial Oversight

The best way to clear the regulatory clutter is to expand the Fed's mandate. [This mirrors Awrey's preference for centralized oversight of monetary functions.] For example, there is no compelling economic justification for maintaining state-chartered banks. Phasing them out would eliminate the FDIC's supervisory role...

The Shadow Monetary System

While Private Finance, Public Power explores banking regulation, Awrey's Beyond Banks focuses on monetary IOUs...

Banks have become the custodians and gatekeepers of financial infrastructure. But a shadow monetary system is rapidly evolving and expanding...

Can Good Digital Money Drive Out the Bad?

Awrey argues that the dominant means of payment should not take the form of liabilities issued by financial intermediaries. Instead, he proposes narrow banking aimed at eliminating bank runs. Under this framework, digital money issuers would be required either to obtain a conventional banking license or invest all proceeds in central-bank reserves.

I would go even further: all issuers of monetary IOUs should be required either to give up on financial intermediation and issue only money fully backed by central-bank reserves, or to transfer all deposit-related liabilities to an independent subsidiary...

In fact, if these two very different books offer a single, clear takeaway, it is this: to build a simpler, more stable, and more innovative financial system, we must demonetize bank liabilities by separating the creation of monetary IOUs from financial intermediation. [Whether through Conti-Brown and Vanatta's regulatory consolidation or Awrey's narrow banking model, both paths lead to the same destination: a financial system where money creation and risk-taking are organizationally separate.]

Nuclear armageddon

Climate change is real and serious, but it’s never been as important or as dangerous as something we pretty much forgot about for the 30 years after the cold war. So I was glad to get this update on the state of things. Here was I hoping that nuclear winter was a bit of a beat-up. Alas no. Once we get a serious exchange between superpowers, looks like it’s all over for most of us, including many of the preppers. It was also good to hear that it looks like climate change will be bad, (say +3°) but not catastrophic (say 5-6°).

Ordinal Citizenship

As we head towards heaviosity, here’s a heavy(ish) 2019 lecture on the ways in which ranking systems are invading our heads and producing new hierarchies in our lives. It’s from a guest lecture by rising star of sociology Marion Fourcade. I did like the quote from an interview with her which the MC used to introduce her.

Quite simply, understanding the world supposes that we understand the lenses that we apply to the world, and how these lenses vary over time (roughly, that’s Foucault), across societies (roughly, that’s Durkheim and Mauss, but also Tocqueville), and depending on people’s social situations (roughly, that’s Bourdieu but also, in a different way, Goffman). We can study these lenses in –for instance– language (the things we say and those we don’t), in institutional rules and divisions (the things we allow, implicitly or explicitly, and those we don’t), and in practices (the things we do and those we don’t). Finally, classification is closely connected to the question of moral valuation: dividing the world into categories almost inevitably means arranging the categories into a hierarchy, so the study of classification systems is, fundamentally, a study of the social order.

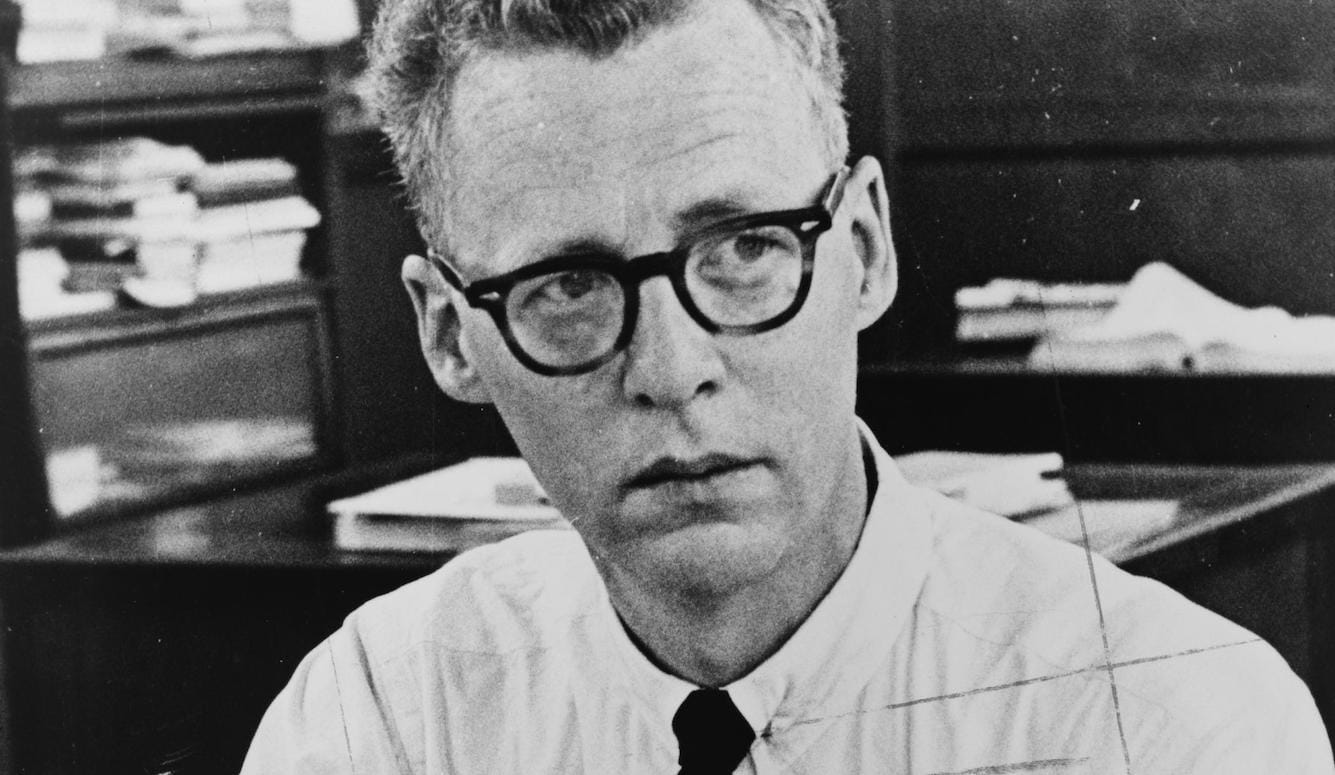

Who was Murray Kempton? (I didn’t know either)

A review of Going Around: Selected Journalism by Murray Kempton, edited by Andrew Holter; Seven Stories (April 2025).

During an interview towards the end of his life, journalist Murray Kempton was asked by C-Span's Brian Lamb how he defined himself politically. Kempton burbled on a bit about "Tory anarchism" before finally settling on "radical." A new collection of Kempton's journalism from 1935 to 1997 confirms that his politics were difficult to categorise...

If "radical" is assumed to be a synonym for far-Left, then it isn't really apt—Kempton was too broad-minded and unpredictable for that. He was a repository of second thoughts, and of following the evidence where it led, even if it ended up contradicting his previous position. He was a defender of underdogs (his favourite adage was "never kick a man except when he is up")...

James Murray Kempton (1917–97) was born in Baltimore into what he liked to call "shabby gentility." This meant that his family had servants but his mother worked and they had no car. Or as he put it:

The world of shabby gentility is like no other; its sacrifices have less logic, its standards are harsher, its relation to reality is dimmer than comfortable property or plain poverty can understand.

In 1935, Kempton enrolled at Johns Hopkins University, where the student body leaned left. He joined the Young Communist League during his freshman year. Being a Party member brought prestige and a kind of political affirmative action. As a result, Kempton became editor-in-chief of the student newspaper. From the vantage point of the anti-communist 1950s, he later marvelled, "There was a time in this country when you joined the Communist Party to advance your career." He recalled those years as a time when he wrote with "windy preachment," but he was canny enough to see that Stalin's 1934–38 show trials were a monstrous frame-up...

After graduating, Kempton worked as a labour reporter for the New York Post, interrupted by service in the Army Air Corp during World War II. After the war, he resumed reporting under the tutelage of anti-New Deal reporter Victor Riesel. Watching Riesel turn purple whenever he spoke about liberals caused Kempton to become a soberer reporter: "If anger becomes your technique," he remarked, "in the end you find there's nothing in you but rage." He later wrote for Newsday, edited the New Republic in the 1960s, and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985...

The Communist Party, he eventually concluded, "had no room in it for doubt or pity or mercy," and this lesson became central to Kempton's journalism thereafter. Much of Kempton's writing collected in Going Around is an attempt to practise these qualities. That is why he is so difficult to pin down politically...

Kempton sometimes had kind words to say about liberals' foes. Of the disgraced Nixon being denied a Manhattan apartment because the residents didn't want such a noxious neighbour he wrote: "Who else in America except the tenant of an East Side co-op has a license to lock somebody out for no better reason than his fancied unlikeability?"

He took issue with liberals who dismissed ex-President Eisenhower as an airhead: "He was the great tortoise upon whose back the world sat for eight years. We laughed at him; we talked wistfully about moving; and all the while we never knew the cunning beneath the shell."...

Reflecting on his career at seventy, Kempton said:

I have seen Robert Kennedy with his children and John Kennedy with the nuns whose fidelity to their eternal wedlock to Christ he strained as no other mortal man could. I have been lied to by Joe McCarthy and heard Roy Cohn lie to himself and watched a narcotics hit man weep when the jury pronounced Nicky Barnes guilty. Dwight D. Eisenhower once bawled me out by the numbers, and Richard Nixon once did the unmerited kindness of thanking me for being so old and valued an adviser.

But perhaps a better summary of his approach to journalism was provided by this description in his New York Times obituary:

On Nov. 21 last year, at a Society of the Silurians dinner honoring him, Mr. Kempton recalled his early days as a labor reporter. The first year he received 150 bottles of "reasonably good" whisky for Christmas, the normal ration for the reporter on that beat. The second year he got two.

"I realized for the first time that meant that I would never in the future have any sources, and I could henceforth be an outsider, and I was simply stuck with watching the game and ending up most of the time in the lonely honor of the loser's dressing room." It was, he made clear to his audience that night, where he preferred to be.

That is why Murray Kempton would not fit into today's journalism—he was not interested in taking sides in a team sport or flattering his sources or currying favour with those who might advance his career. In today's world of sixty-second pundits and fiercely competitive zero-sum tribalism, there is very little room for Kempton's brand of honesty, mercy, and second thoughts. More's the pity.

Dunera Boy and Bauhaus graduate: Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack

Martin Flanagan on Tasmanian footy and THAT stadium

Here’s Martin Flannigan leading with a point I strongly agree with. Playing competitive AFL football is very hard. Organising it is harder. What a terrible situation to find oneself in starting from scratch in a community which is far more divided than it ever needed to be.

I love Tassie footy and we need a team. But the AFL's stadium ultimatum takes a special kind of arrogance

The question is not whether the introduction of a Tasmanian team to the AFL could have been handled better, but whether it could possibly have been handled worse.

The two people I feel sorry for right now are Brendon Gale, the CEO of the newly formed Tasmania Football Club, and Grant O'Brien, its chairman. Both emerged from the Penguin Football Club, a great little Tasmanian footy club that battled the odds and won occasional premierships because they were a formidably tight unit. I believe Brendon and Grant love Tassie footy, as do I.

The paradox at the heart of Australian football is that it's a great game by world standards played by a tiny percentage of the world's population. It's also a 19th century game. The art of keeping it alive in the 21st century is a measure of its leaders. Right now, in Tasmania, the organisation demonstrating this art with zest and conviction is the NBL 2023-24 premiers, the Jackjumpers. Head coach Scott Roth crisscrosses the state meeting locals and talking about his game. People are impressed. I hear his stories being retold.

You could write a footy TV drama, a black comedy, and title it The Stadium. It would tell the story of a proud little footy state that battles away for well over a century – and, for a period in the 1960s, produces the best and most exciting talent in the country – and then finally gets its chance to play in the big time BUT … a condition is attached. A condition never attached before. The Stadium.

Tassie will build, and basically pay for, a new stadium. Along with nearly all the AFL's brainstorms, the idea comes from America. It's a way of divorcing investors from the social costs of sport.

The Stadium was also awarded – again, no one seems to know exactly how – the Macquarie Point site...

Hobart's renowned beauty has two obvious aspects, the mountain and its colonial waterfront. The Stadium will dwarf the colonial waterfront, sitting behind it like a giant hamburger bun. (And good luck with the glass roof on days when the fierce old Tassie sun, unhindered by the ozone layer, breaks through).

The first question my TV drama will ask is – whose idea was this? The AFL, you see, insist it is not theirs. They say it came from the presidents – that is, the 18 AFL presidents who meet on Tuesday to consider whether the Tasmania Football Club's invitation could be withdrawn in light of the ongoing trouble over this idea of theirs which has now precipitated a state election in which the two major parties will support The Stadium and a majority of Tasmanian voters will oppose it...

The special arrogance of the people who cooked up this idea was thinking that the locals would swallow what they were fed. One of the arguments in favour of The Stadium goes like this: the people of Adelaide didn't want changes to Adelaide Oval when it became a three-sided stadium, but now they love it. Therefore, the argument goes, that's what'll happen in Hobart.

The Stadium will dwarf the colonial waterfront, sitting behind it like a giant hamburger bun.

There's a difference between the two cities. When did you last hear of a public protest in the streets of Adelaide? There's one every other month in Hobart. It's a city with a non-stop history of citizen political activity going back to the 1960s.

Right now, the three hottest issues are salmon farming, logging native forests and The Stadium. In some minds, they are interchangeable.

Around now, if I were Brendon Gale, I'd feel I was stuck in an absurdist play. The still unborn Tasmanian Devils are now front and centre in the island's culture wars, the last place you want it to be if you were the one person with the vision and ability to build a football club for the new Tasmania that was ready and waiting to jump aboard … until The Stadium.

What makes some of us angry is that it didn't have to be like this, particularly when so much is at stake...

There are now clubs in Tasmania where once there were associations; Bracknell is one of them. A proud little footy survivor, a town of 300 people, the same couple of families keeping the club going for three generations. No AFL player has ever visited the kids at Bracknell Primary School but – guess what? – Jackjumpers head coach Scott Roth has.

Bracknell does not receive one cent from the AFL. The club secretary works 30 unpaid hours per week as well as managing the office of her family business. Remember this when next you see a story saying the AFL made a multimillion-dollar profit last year with the implication that the game is in boomingly good health – that is a dangerous illusion because it only tells the story at one level...

In 1973 Scottsdale were the best team in Tasmania and competed against Richmond, Glenelg and Subiaco for the Australian championship. For three decades they were a top Tasmanian club. Three weeks ago I watched as they kicked 0 goals, 0 behinds against their old foes, North Launceston. If Scottsdale Football Club expires, there will be no football club in the north-east of the island between St Helen's on the east coast and Bridport on the north coast.

Over the past century, the west coast of Tasmania had eight different associations and around 100 clubs. It now has two clubs. In the bottom third of the island – including the greater Hobart area – there are only 16 football clubs left. The game is much stronger in the north and north-west, but these are precisely the areas where The Stadium is most unpopular.

The unique genius of The Stadium is that it has alienated so many footy followers. Should the Tasmanian club's licence now be withdrawn, I would expect a loss of enthusiasm for the game at all levels, including the AFL.

What is happening to Australia's great 19th century athletic invention in Tasmania is happening in various degrees to grassroots footy in other parts of the country. To those who insist on seeing the game and its future in purely corporate terms I say - get real. Without grassroots footy, there is no "AFL industry"...

If I were addressing the 18 presidents I'd say – we need the team, and you need us. You needed us in the past and you will need us again in the future, if there is to be one.

Heaviosity and hollowing out half-hour

Ezra Klein on the hollowing out of the local

Martin Flanagan’s lamentation of the hollowing out of community football in Tasmania reminded me of Ezra Klein’s elaboration of similar forces towards the ‘nationalisation’ and so ‘delocalisation’ of politics in the US. From Why we’re Polarised (Even if the Americans consistently mis-spell ‘polarised’.

All politics isn’t local

Nebraska senator Ben Nelson was the final, crucial vote on the Affordable Care Act. Nelson was an old-school Democratic centrist, a transactional, silver-haired former insurance executive who held on in a red state through acts of ostentatious moderation and a laser-like focus on Cornhusker interests. But he was in a bind. The choice on Obamacare was yes/no. Democrats needed his vote to pass the law. Nelson wanted the law to pass. But Obamacare was unpopular back home, and Nelson was up for reelection in 2012. He was caught between his career, his party, and his conscience.

Nelson’s solution was to split the ideological interests of Nebraska’s Republicans from the financial interests of Nebraskans. Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion was built with an unusual structure. Typically, Medicaid is funded by a roughly 60:40 split between the federal government and the states. The Affordable Care Act, however, promised that the federal government would pay 100 percent of the law’s new Medicaid costs for three years, before phasing down to a 90:10 split by 2020. But some conservatives said that even the 10 percent states were being asked to pay was too much. This was, in particular, a charge levied by Nebraska’s popular Republican governor, Dave Heineman. So Nelson negotiated a special deal on the state’s behalf: for Nebraska, the federal government would carry 100 percent of the Medicaid expansion’s bill, a subsidy worth more than $100 million.

Nelson was doing what members of Congress have done since the dawn of the republic: winning support for a polarizing national policy by extracting a material concession for his state. The American political system is built on a deep sense of place. The House isn’t meant to host the meeting of two parties but of 435 districts; the Senate is not meant to represent red and blue but to balance the interests of fifty states. This reflects the Founders’ belief—true in their time—that our political identities were rooted in our cities and states, not the more abstract bonds of nationhood. “Many considerations … seem to place it beyond doubt that the first and most natural attachment of the people will be to the governments of their respective States,” wrote James Madison in Federalist 46.

The centrality of state and local political concerns in national politics has been one of the American political system’s brakes on polarization. The zero-sum forces of two-party competition were moderated by the regional interests of politicians rooted, first and foremost, in a particular place. Sure, you may be a Republican, and that bill might be pushed by Democrats, but you’re a Republican from Oklahoma, dammit, and that bill is good for Oklahoma. Catering to a member of Congress’s particularistic interests, either through the direct design of the legislation or through earmarks offering unrelated benefits, gave congressional leaders ways to build coalitions that the logic of partisanship denied. Your party might not want you to vote for that bill, but if you vote for it, your district will get money for a bridge it desperately needs, and putting your name on that bridge is worth more than keeping your copartisans happy.

At least, it was.

In his book The Increasingly United States, Daniel Hopkins tracks the troubling nationalization of American politics. At the core of that nationalization is an inversion of the Founders’ most self-evident assumption: that we will identify more deeply with our home state than with our country. Hopkins traces the change here in a variety of clever ways. He ran a text analysis of digitized books going back to 1800, comparing use of the phrase “I am American” with “I am a [Californian/Virginian/New Yorker/etc.].” Prior to the Civil War, expressions of state identity were far more common than expressions of national identity. National identity took the lead in the run-up to World War I, the two traded places for a while in the early twentieth century, and then, around 1968, expressions of national identity raced ahead and never looked back. He shows that when you ask Americans to rank their most important identities in surveys, almost everyone lists nationality in their top three, while the number listing their state, city, or neighborhood lags far behind. He finds that people are likelier to feel insulted when America is being criticized than when their state or city comes in for scorn. He shows that when asked to explain why they are proud of their nation or their state, they routinely express national pride in terms of politically relevant values, while state pride tends to focus on geographic features. I love America because of freedom; I love California because of beaches.

If all of this seems obvious—if you take the centrality of national identity for granted—that’s the point: what was unimaginable to the Founders is self-evident to us.

As goes identity, so goes politics. In an analysis of more than 1,600 state party platforms dating back to 1918, Hopkins finds while “the platforms in earlier eras focused more on state-specific topics,” modern platforms “now emphasize whatever topics dominate the national agenda.” Similarly, he shows that in 1972, “knowing which way a state leaned in presidential politics told one nothing about the likely outcome in the gubernatorial race.”15 Today, it tells you most of what you need to know.

The culprit here is obvious. In recent decades, the media and political environments have both nationalized. Voters following politics today get constant cues to think about national politics, but coverage of state and local politics is declining. For instance, growing up, I read the Los Angeles Times and listened to LA’s public radio station, KCRW, which fed me national political stories but also state and local stories. I developed, as a result, a pretty strong identity around California politics, which was less polarized than national politics and focused on very different questions. What I never did was read the New York Times, because we didn’t get it, or listen to national political podcasts, because they didn’t exist.

If I were growing up outside Los Angeles today, perhaps I’d be reading the newly revitalized LA Times, but it’s likelier, as a political junkie, that I’d be reading the New York Times and the Washington Post and Vox, listening to political podcasts, and watching cable news. All of that would be civic-minded and informative, but it would be pounding away at my national political identity and underdeveloping the parts of my political psyche rooted in the place I actually lived. A nationalized media means nationalized political identities.

States used to have different political cultures from that of the nation as a whole. That gave members of Congress crosscutting incentives from what the national parties wanted. Now those incentives are, like so many others, stacked. As Hopkins writes, “Rather than asking, ‘How will this particular bill affect my district?’ legislators in a nationalized polity come to ask, ‘Is my party for or against this bill?’ That makes coalition building more difficult, as legislators all evaluate proposed legislation through the same partisan lens.” A more nationalized politics is a more polarized politics.

Here’s an easy way to realize the truth of Hopkins’s point: if local interests drove voting patterns, you could predict how a member of Congress would vote on the Affordable Care Act by knowing whether the uninsured rate among his or her constituents was above or below the national average. The ACA was, above all else, a direct subsidy to areas with larger uninsured populations from areas with smaller ones. But how a member of Congress voted on the ACA was almost perfectly predicted by party affiliation—as evidenced by the fact that not a single Senate Republican voted for it and not a single Senate Democrat voted against it. State conditions predicted nothing.

A weird thing happened as we nationalized our politics. We became disgusted with the ways that local politics played out nationally. Take earmarks, the small addenda members of Congress would add on to bills to fund a road, a hospital, or a job-training bill back home. Earmarks were a way that bipartisan cooperation was, yes, bought. The Congress reporter Jon Allen described how it worked in a 2015 Vox article:

In 2003, I asked Jack Murtha, the Democratic defense appropriator who controlled about $4 billion in earmarks each year, about Tom DeLay, the Republican leader known as “The Hammer” for his ability to nail down votes. Murtha sat in the far corner of the Democratic side of the House, out of view from the press galleries, and DeLay would sometimes come to visit him before a tight vote. When DeLay needed a few Democrats to secure a win on the floor, Murtha said, “He comes over to the corner, and we work it out.” Murtha’s earmarking power meant that he had a roster of people who owed him favors. For a little more money, he could easily swing a small bloc of votes to help DeLay pass a bill. Murtha and DeLay didn’t agree on much, but earmarks kept them talking, and working with each other.16

In 2011, Congress got rid of earmarks entirely. They were considered a corrupt, and a corrupting, form of politics. Much better to have Congress run on pure principle and partisanship than the grimy work of negotiating something tangible for your constituents. To ideologues, transactional politics always looks dirty. To the transactional, ideologues look self-destructive.

That is, in the end, what happened to Nelson. Rather than being celebrated back home for cutting Nebraska such a sweet deal, conservative media pounced on him. His concession got branded the “Cornhusker Kickback,” and his own governor told him to turn it down. “Now it’s a matter of principle,” Heineman told Politico. “The federal government can keep that money.”17 Nelson called him “foolish” but backed down. The provision was stripped from the bill. Nelson, seeing the writing on the wall, declined to run for reelection in 2012 and was replaced by a Republican.

That same year, Heineman cautioned his constituents against accepting the Medicaid expansion they could’ve had for free. “If this unfunded Medicaid expansion is implemented, state aid to education and funding for the University of Nebraska will be cut or taxes will be increased,” he warned.18

Great illustration on the AUKUS affair. But maybe the elephant could be a little whiter ...

I meant to add that I have bought the Quarterly essay for the High White essay - read a fifth of it - and found myself on a number of points in quite strong disagreement - and I feel as if defrauded. I will continue with my reading because who knows - there might yet be part of it which might redeem his thinking - to my mind at least!